Abstract

In vivo studies in monkeys and humans have indicated that immunodeficiency viruses with Nef deleted are nonpathogenic in immunocompetent hosts, and this has motivated a search for live attenuated vaccine candidates. However, the mechanisms of action of Nef remain elusive. To define the regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Nef which mediate in vivo pathogenicity, a series of mutated isogenic viruses were inoculated into human thymic implants in SCID-hu mice. Mutation of several regions, including the myristoylation site at the second glycine and a region encompassing amino acids 41 through 49 of Nef, profoundly affected pathogenicity. Surprisingly, mutations of prolines in either of the two distant PXXP SH3 binding domains did not affect pathogenicity, indicating that these regions are not required for Nef activity in developing T-lineage cells. These data suggest that some functions of Nef described in vitro may not be relevant for in vivo pathogenicity.

The nef open reading frame of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is located at the 3′ end of the virus, partially overlapping the U3 region of the 3′ long terminal repeat. nef mRNA represents more than 80% of the multiply spliced transcripts expressed during early viral transcription, and encodes a 27- to 29-kDa cytoplasmic protein which is membrane localized by an N-myristyl group. Nef-deficient simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) fails to produce AIDS in infected adult macaques (25). Some humans infected with Nef-deleted HIV have remained disease free, with normal CD4 counts 10 to 14 years after infection (9, 26), although deletion of Nef is not a universal finding in nonprogressors (21). In vitro, Nef also confers a growth advantage (8, 34, 48), whose magnitude depends upon the activation state of the cell. Biochemically, Nef associates with various cellular kinases (5, 41, 44, 45). The Nef of one SIV strain has been implicated in lymphocyte activation (10, 13). Nef expression also results in posttranslational down-regulation of the CD4 protein (15, 19); however, the significance of this down-regulation in HIV-1 pathogenesis is unclear. The effect of Nef on CD4 down-regulation appears to be distinct from its effect on infectivity (17, 43, 46, 52).

Unlike in vitro systems, the SCID-hu mouse model involves infection of a functional human hematopoietic organ (Thy/Liv) that resembles a human thymus and directs normal T-cell development from hematopoietic precursor cells (33, 36). This system allows for the simultaneous assay of infection, replication, and pathogenicity. This dynamic in vivo model has been used to detect differences in pathogenicity not observed in traditional in vitro systems. Infection of this organ with HIV-1 results in depletion of CD4-bearing cells and a histologic picture reminiscent of that observed in human infection (1, 2, 6, 22, 28, 49). However, HIV strains lacking a functional nef gene have a decreased ability to deplete CD4-bearing cells in this system (2, 22). With this system, we have now used a series of isogenic mutated viruses to localize regions of the nef gene that confer increased pathogenicity. Our data indicate that the myristic acid site at position 2 and a region encompassing amino acids (aa) 41 to 49 of Nef are required for a fully pathogenic phenotype. Interestingly, neither of the two proline repeat regions previously shown to associate with multiple cellular kinases are required for virus replication and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cells.

HIV nef deletion mutants Δnef, ΔNRE, and Δnef/NRE were obtained from Ron Desrosiers and are described elsewhere (16). All the mutants were constructed with pNL101, which contains the same proviral sequence as HIV-1NL4-3, with the entire 5′-flanking region and no 3′-flanking region recloned into plasmid pUCBM21 (40). This plasmid has a unique XbaI site in the 3′-flanking region. The BamHI-XbaI fragment was cloned into pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene) for oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis, by using the Amersham in vitro mutagenesis system, v.2, as specified by the manufacturer. The primers used to construct deletion mutants are as follows: deletion 1, 5′-ctcagctcgtctcattctttcttttgaccacttgcc-3 (deletion of nucleotides [nt] 22 to 51 of nef inclusive); deletion 2, 5′-atgtttttctaggtcctcagctcgtctcattctttc-3′ (deletion of nt 73 to 105 of nef inclusive); deletion 3, 5′-ggcacaagcagcattgttagcatgtttttctaggtc-3′ (deletion of nt 118 to 147 of nef inclusive); deletion 4, 5′-aggtgtgactggaaaaccggcacaagcagcattgttagc-3′ (deletion of nt 169 to 198 of nef inclusive); deletion 5, 5′-gctaagatctacagctgcaggtgtgactggaaaacc-3′ (deletion of nt 217 to 246 of nef inclusive); and deletion 6, 5′-ggagtgaattagcccctctaagatctacagctgc-3′ (deletion of nt 265 to 294 of nef inclusive). All the deletion mutations were in frame, and all were confirmed both before and after being cloned into the full-length plasmid. Point mutations were introduced into single-stranded DNA by the method of Kunkel et al. (30). The substrate for mutagenesis was a plasmid carrying the BamHI (nt 8466)-XbaI (nt 9711) fragment of pNL101, prepared in Escherichia coli CJ236. The primer for the myristoylation-deficient mutant (MYR−) (5′-ccacttgccaGccatcttat-3′) directed a G-to-C point mutation at position 8791 (resulting in a Gly-to-Ala change). The primer for the point mutation, which abrogated the second start (ATG 2) (5′-agctcgtctaattctttccc-3′), directed an A-to-T mutation at position 8823 (resulting in a Met-to-Leu change. Primer SH3×4 for the PXXP4 mutant (antisense, 5′-cattgctcttaagctacctgagctgtgactgcaaaaccc-3′) directed C-to-G mutations at positions 214, 223, and 232 of nef. The primer for the PXXP2 mutant (5′-atctgCctcaaactgCtactag-3′) directed C-to-G mutations at positions 439 and 448. Primer R105L (5′-caaggatatcttctaataattgggagtgaattag-3′) directed A-to-T mutations at positions 313 and 316 and G-to-T mutations at positions 314 and 317, which resulted in the arginines at aa 105 and 106 being converted to leucines to construct the ARGX2 mutant.

The sequence of each altered DNA fragment was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Sequenase 2.0 kit; United States Biochemical Corp., Cleveland, Ohio) both before and after being cloned into the full-length plasmid. Plasmid preparations of wild-type and mutant viruses were grown on a large scale and purified with QIAgen maxipreps (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.).

Virus stocks of the deletion mutants were prepared by transfection of the DNA into CEMx174 cells, while constructs containing point mutations were transfected into COS cells, as previously described (2, 7). Viral stocks were collected, filtered, and assayed for p24 content by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.). Aliquots of the viral stocks were stored at −70°C. The virus titers were determined in parallel by fivefold limiting dilution in duplicate on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), from a single donor, that had been stimulated for 3 days with phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Infectious units were standardized to wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 in which 2.5 ng of p24 was equivalent to 100 infectious units. Normal human PBMC were obtained from Leukopaks purchased from the American Red Cross. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were isolated by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque and depleted of macrophages by adherence to plastic for 72 h. Growth kinetics of the different viral isolates were determined by infection with equal infectious units on human PHA-stimulated PBMC followed by quantitation by ELISA specific for the viral p24 Gag protein. Western blot analyses for mutant Nef protein expression were performed on cell lysates of infected C8166 cells, using a polyclonal anti-Nef antiserum, and are also reported elsewhere (50). After infection of the Thy/Liv grafts, an aliquot of virus from the same vial used to infect the tissue was used to infect PHA-stimulated PBMC to confirm virus viability.

Construction, infection, and biopsies of SCID-hu mice.

C.B.-17 scid/scid mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID mice) were originally obtained from K. Dorshkin and subsequently bred at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). All experimental animals were housed in a Biosafety Level 3 facility at UCLA and handled in accordance with institutional guidelines. All the animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine HCl-xylazine mixture (1 mg/10 g of body weight) before any invasive manipulation. When the mice were 6 to 8 weeks of age, ∼1-mm3 pieces of human fetal thymus and liver (Thy/Liv) were surgically implanted under the murine kidney capsule, as previously described (1). Fetal tissue (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda, Calif.) was obtained from donors ranging in gestational age from 16 to 24 weeks. At 4 to 6 months postimplantation, the grafts were infected with 100 or 500 infectious units (IU), as indicated in the text, in approximately 50-μl volumes by direct injection. Mock-infected implants were injected with medium.

Since it is possible to obtain only limited numbers of reconstituted SCID-hu mice from a single donor, multiple donors were used for these experiments. To control for any variation in genetic backgrounds that might have had a bearing on the susceptibility of the target cells to HIV infection, mice transplanted with tissues from different donors were distributed randomly among the experimental groups that were infected with the various HIV-1 mutants. In addition, wild-type and “mock” virus and at least two isogenic accessory gene mutants were inoculated into tissue from a single donor. In these experiments, we did not detect any obvious differences attributable to donor variation; however, the numbers of animals and donors were too small to perform statistical analysis.

Wedge biopsy specimens of Thy/Liv tissue were obtained at 3-week intervals after infection. Approximately one-fourth to one-third of the implant was removed at each biopsy. Human thymocytes were teased from the stromal elements, filtered through a screen (Cell strainer; Falcon, Franklin Lakes, N.J.), washed in phosphate-buffered saline, counted, and then aliquoted for subsequent PCR and flow cytometric analyses.

Quantitative PCR amplification.

DNA was isolated from single cells obtained from the biopsied implants by using the QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen) as specified by the manufacturer. Purified DNA was then subjected to quantitative PCR as previously described (1, 53, 54). Briefly, PCR amplifications were carried out for 25 cycles with 32P-end-labeled primers. The M667-AA55 primer pair, which is specific for the R/U5 region of the viral long terminal repeat, was used to detect HIV-1 sequences (53, 54). The amount of human cellular DNA in each sample was quantified by PCR amplification with primers specific for the human β-globin gene (nt 14 to 33 and 123 to 104). Standard curves for HIV-1 DNA consisted of linearized HIV-1JR-CSF in normal human PBMC DNA (10 μg/ml) as carrier. Standard curves for human β-globin were derived from 10-fold dilutions of normal PBMC DNA. Both the HIV-1 and β-globin standard curves were amplified in parallel with Thy/Liv samples. The PCR amplifications were carried out in 15 μl of low-salt PCR buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 2 mM MgCl2, 30 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 0.25 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate). S/P high-purity water (Baxter Healthcare Corp., McGaw Park, Ill.) was used to bring the reaction volume to 25 μl. Following amplification the PCR products were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. Quantitation was achieved by extrapolation to the standard curves by radioanalytic image analysis (Ambis, San Diego, Calif.). This method of DNA PCR can detect ten proviral copies per μg of genomic DNA. Values obtained from this assay never varied above 30% of the actual values in controlled experiments.

Confirmation of infection.

To confirm infection of each implant with the appropriate deletion mutant, primer pairs flanking each deletion were used to amplify proviral sequences by PCR. Analysis was performed on DNA obtained 6 weeks postinfection, and no contamination with wild-type sequences was ever detected. DNA from implants infected with viruses containing point mutations was sequenced to determine whether introduced mutations were maintained. No reversion of point mutations was observed at the 6-week time point in any of the analyzed implants.

Flow cytometric analysis of Thy/Liv cells.

Thymocytes were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody to human CD4 (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody to human CD8 (Becton Dickinson) as specified by the manufacturer. Thymocytes were also stained with PE- and/or FITC-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 as isotype controls. Data were acquired on a FACScan flow cytometer and analyzed with the Cell Quest program (Becton Dickinson). The live cell population was determined by gating on the forward-versus-side-scatter plot of thymocytes derived from mock-infected implants. A total of 5,000 to 10,000 events were acquired, except in the case of severely depleted implants.

Statistical analyses.

Comparisons of proportions between groups were made by Fisher’s exact test. This test is more appropriate than a chi-square test for small samples and is asymptotically equivalent to a chi-square test for large samples. To test whether two distributions were the same, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. This nonparametric test is valid over a wide range of distributional assumptions and is invariant with respect to monotonic transformations such as taking logarithms. All comparisons were for two-sided alternatives.

Infectivity was measured by determining the proportion of implants showing detectable HIV at the 3- and/or 6-week time points. Animals that had undetectable HIV 3 weeks postinfection and that died before the 6-week biopsy were excluded from the analysis, since infection could not be confirmed. Calculations for demonstrating viral replication and differences in pathogenicity were made by using only the animals that were positive for HIV DNA sequences at the three- and/or 6-week time points. Pathogenicity was measured by determining the percentage of CD4+ CD8+ double-positive thymocytes at both time points. Viral replication was calculated as the number of proviral copies per 100,000 cells.

RESULTS

Effects of Nef deletions on virus replication.

To determine the regions of the nef gene responsible for mediating this pathogenic phenotype, a series of deletion and point mutants were constructed, as depicted in Fig. 1 (also see Fig. 3). When 100 IU of viruses containing large deletions in either the 5′ or 3′ region of nef were introduced into Thy/Liv implants, many did not become infected (reference 2 and data not shown). To overcome the effects of decreased infectivity of viruses with Nef deleted, all experiments reported here were performed at a higher multiplicity of infection (500 IU). The effects of these deletions on HIV-1-induced depletion of CD4-bearing thymocytes and proviral load are depicted in Fig. 2. Attenuated viral pathogenicity was seen following deletion of the 5′ half (Fig. 2) or the 3′ half (ΔNRE, not shown) of nef or a combination of the two deletions (Δnef/NRE, not shown). Consequently, viruses with smaller nested deletions (approximately 10 aa) in the 5′ half of nef were inoculated into the Thy/Liv implants of SCID-hu mice.

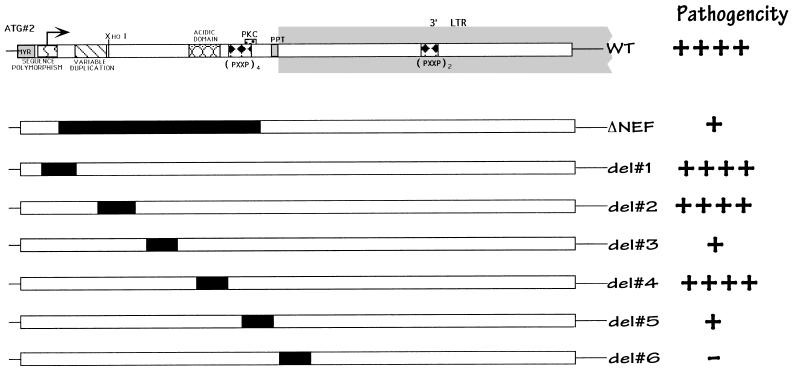

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the nef gene and isogenic deletion mutant forms. Putative functional regions of Nef are indicated at the top. At the far right is a summary of relative Nef activity, as determined by our studies. ++++, wild-type growth; +, attenuated growth; −, no detectable virus. This interpretation was based on our statistical analyses (see Fig. 2).

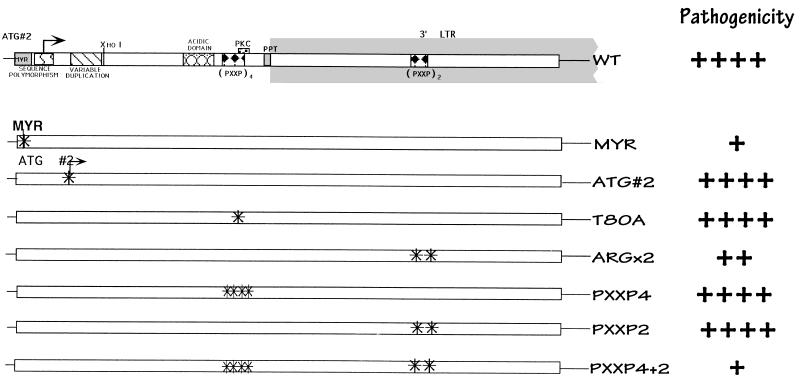

FIG. 3.

Schematic of the nef gene and isogenic point mutant forms. As in Fig. 1, a summary of relative pathogenic potential is given at the right. ++++, wild-type growth; +, attenuated growth; ++, somewhat attenuated growth. The statistical data used to make these interpretations are given in the legend to Fig. 4.

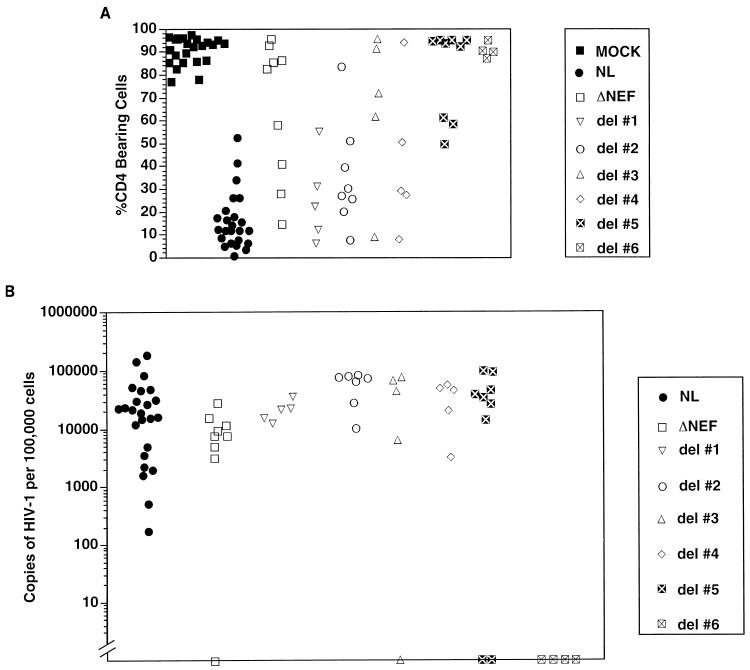

FIG. 2.

Thymocyte depletion (A) and proviral load (B) in Thy/Liv implants 6 weeks postinfection. Each symbol represents a different implant infected with the corresponding viral strain, as described in Fig. 1. (A) Percentage of CD4-bearing cells (including both CD4+ CD8+ double-positive and CD4+ single-positive subsets), as determined by flow cytometry (1, 2). An implant was considered depleted if it was infected and had fewer than 55% CD4-bearing cells. Nef-minus viruses (Δnef) and strains with deletions 3 or 5 were less capable of depleting CD4-bearing cells than was the wild-type virus (NL). This difference was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, two tailed), with P = 0.0002, 0.0004, and 0.00002 for Δnef and deletions 3 and 5, respectively. Deletion 6 was not included in these calculations, because the virus was not infectious (B). Other viruses yielded P > 0.05. (B) Number of HIV-1 genomes in 105 human thymocytes, as determined by quantitative DNA PCR. Symbols on the x axis indicate implants with undetectable HIV DNA. The minimum amount of DNA assayed was the equivalent of 104 thymocytes.

Deletions were made in regions of the gene which had been suggested to be important for protein function. Deletion 1 (aa 8 to 17 inclusive) includes a region of sequence polymorphism (47) that has also been postulated to be a nuclear targeting sequence (35). Deletions 2 (aa 25 to 35 inclusive) and 3 (aa 41 to 49 inclusive) are relatively conserved regions of indeterminate function. The region excised in deletion 4 (aa 57 to 66 inclusive) has been predicted to lie on the outer surface of the protein because it is charged and acidic. This region also encodes a putative viral protease cleavage site in the protein (12, 14, 39, 51). Deletion 5 (aa 73 to 82 inclusive) encompasses the two terminal proline residues of the 5′ PXXP SH3 binding motif, as well as a potential protein kinase C phosphorylation site (threonine 80). In addition, this region appears to be important for the association of Nef with the cellular cytoskeleton (23). Deletion 6 (aa 89 to 98) removes the polypurine tract, which is important in initiating plus-strand DNA synthesis during reverse transcription. Following infection, all nested deletion and point mutant viruses, except the one lacking the initial ATG and deletion 6 (see Fig. 3), produced Nef proteins detectable by immunoblot analysis with Nef antiserum (50). Protein levels shown by Western blotting in cells infected with most mutants were similar, with the level PXXP4 mutant being only slightly lower than that in the wild-type-infected cells. However, Nef protein levels in cells infected with PXXP4+2, ARGX2, or deletion 5 were significantly lower than in the wild-type-infected cells, so we cannot exclude that loss of protein stability may have contributed to the observed phenotypes of these mutants (see below).

After 6 weeks postinoculation, all the implants injected with viral strains containing deletions 1, 2 or 4 were productively infected, achieving viral loads and thymocyte depletion equivalent to those due to wild-type virus (Fig. 2). In our system, deletion of the putative nuclear localization signal (deletion 1) did not alter the infectivity, replication, or pathogenicity of the virus. In contrast, viruses bearing deletions 3 or 5 did not infect all animals tested, in that the proviral DNA of one of five implants injected with deletion 3 and the proviral DNA of two of nine implants infected with deletion 5 were undetectable by PCR (Fig. 2B). Implants productively infected with these strains showed a marked decrease in depletion of CD4-bearing thymocytes, despite levels of proviral DNA that were similar to those of the wild-type virus. This is similar to what we had previously reported with Nef-minus strains (2, 22). Nef protein levels in cells infected with deletion 3 were identical to those of cells infected with wild-type virus or with deletion mutants 1, 2 and 4 (which had no altered phenotype), suggesting that this region is truly important for in vivo pathogenicity. However, since the levels of Nef protein were significantly lower in cells infected with deletion 5, the apparent effect of this deletion is likely to be due to decreased protein stability (see above). Viruses with a deletion of the polypurine tract (deletion 6) could not be detected in the implants as late as 9 weeks postinfection, presumably because of impaired reverse transcription.

Nuclear magnetic resonance, combined with proteolytic experiments, has suggested that Nef consists of two main domains: an anchor domain located at the N terminus (aa 2 to 65), which is probably located at the surface of the protein, and a more compactly folded core C-terminal domain (12). In addition, it has been reported that Nef is cleaved by proteases between Trp 57 and Leu 58, suggesting that cleavage is crucial for correct biologic function (14, 39, 51). Interestingly, deletion of several regions (deletions 1, 2, and 4) of this putative anchor domain had no effect on viral replication or pathogenicity. However, deletion 3 (aa 41 to 49 inclusive) attenuated viral replication and pathogenicity, presumably by disrupting overall protein structure. The area encompassed by deletion 4 (aa 57 to 66) included the putative protease cleavage domain (14, 39, 51), as well as a conserved glutamic acid-rich segment of the protein (47). Deletion of this region resulted in a virus with a pathogenicity phenotype identical to that of wild-type virus. This finding was somewhat surprising, since an overlapping deletion (aa 60 to 71) was found by others to lower infectivity and abrogate CD4 down-regulation in vitro (17). These results are not necessarily discordant, since the mutations were not identical; thus, we cannot comment on the role of CD4 in down-regulation in Nef-mediated pathogenicity in this system.

Effect of point mutations on pathogenicity.

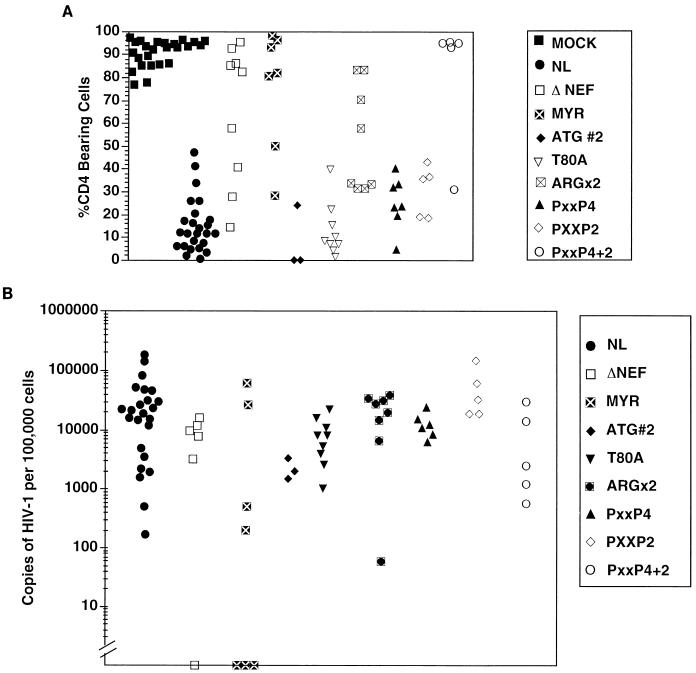

To further define regions responsible for Nef function, a series of viruses containing point mutations in regions associated with various in vitro Nef functions were introduced into Thy/Liv implants (Fig. 3). The myristoylation signal in Nef is conserved in both laboratory and viral isolates, suggesting a critical role in the life cycle. Myristoylation has been demonstrated to be critical for the subcellular targeting of Nef to the cytoplasmic membranes (3, 11, 20), and localization has been proposed to regulate both viral replication and T-cell activation (4). Myristoylation has also been noted to be important for maximal Nef cytoskeletal binding (37), and this has led some investigators to suggest a parallel between Nef and other myristoylated proteins such as Marcks (myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate) and Src (37). Some traces of Nef have also been detected in the nuclei (27, 29, 38, 42). Loss of the myristoylation signal in Nef mutant G2A produced a virus with decreased infectivity and pathogenicity in the SCID-hu model (Fig. 4). This finding confirms the importance of myristoylation for all of the putative functions of Nef, as suggested previously (17, 55).

FIG. 4.

Thymocyte depletion (A) and proviral load (B) in implants 6 weeks postinfection with point mutated viruses. Each symbol represents a different implant infected with the corresponding viral strain, as described in Fig. 3. (A) Percentage of CD4-bearing cells (both CD4+ CD8+ double-positive and CD4+ single-positive subsets), as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 2). An implant was considered depleted if it was infected and had fewer than 55% CD4-bearing cells. MYR− virus and the strains containing the PXXP4+2 point mutation and the ARGX2 mutations were significantly less capable of depleting CD4-bearing cells (Fisher’s exact test, two tailed), with P = 0.001, 0.0002, and 0.015 for MYR−, PXXP4+2, and ARGX2, respectively. Other viruses yielded P > 0.05. (B) Number of HIV-1 genomes in 105 human thymocytes, as determined by quantitative DNA PCR (Fig. 2B).

Neither loss of the second ATG (mutation M20L; Fig. 3) nor mutation of the potential PKC phosphorylation site (T80A) affected infectivity, pathogenicity, or viral replication (Fig. 4). All the implants injected with these mutants were productively infected and exhibited marked thymocyte depletion by 6 weeks postinfection. The results seen with the T80A mutant indicated that the attenuated phenotype seen with deletion mutant 5 (Fig. 2) was not due to loss of the protein kinase C phosphorylation site. Mutation of two arginine residues at positions 105 and 106 to leucines (the ARGX2 mutant), which have been reported to interact with cellular serine kinases and have been implicated in SIV pathogenesis (46), did not appear to affect infectivity or viral replication in the SCID-hu system. Nevertheless, this virus was less able to deplete CD4-bearing thymocytes than was the wild-type virus (Fig. 4A). Sequence analysis of the nef region of proviral DNA obtained from Thy/Liv implants infected with the ARGX2 mutant revealed that no reversion to wild-type sequences occurred (data not shown). However, Nef protein levels with this mutant were somewhat decreased (approximately one-third) compared to wild-type infection in vitro. Thus, while it is attractive to speculate that this region appears to make a modest but significant contribution to Nef function in this system, we cannot rule out protein stability effects contributing to the altered phenotype.

We also explored whether inactivation of previously identified SH3 recognition sequences would have an effect on pathogenicity. Mutation of four prolines (PXXP4 mutant) which constitute a putative SH3 binding domain in the 5′ region (P69A, P72A, P75A, and P78A) or two prolines (PXXP2 mutant) in the 3′ region of Nef (P147A and P150A) did not affect infectivity, pathogenicity, or viral load (Fig. 4). However, simultaneous mutation of all six prolines in both regions (PXXP4+2 mutant) had a significant effect on pathogenicity and viral replication but not on infectivity. All five implants inoculated with this viral strain were productively infected; however, only one of the five implants exhibited depletion of CD4-bearing thymocytes (P = 0.0002). This phenotype, however, may be attributable to decreased Nef protein levels, since cells infected with this virus contained lower levels of Nef protein (approximately one-third, similar to the ARGX2 mutant) than did cells infected with wild-type virus.

DISCUSSION

We set out to define regions of HIV-1 Nef responsible for pathogenicity in vivo. Similar to our previous study (2), we were unable to find a statistically significant difference in viral loads at 6 weeks postinfection between wild-type virus and any of the mutants, with the exception of deletion 6, which was not infectious. We did, however, identify several regions that affected pathogenicity and others that appeared unimportant. Perhaps the most interesting mutants in this latter category were those that encompassed the proline repeat regions, which contain a minimal PXXP consensus SH3 binding domain motif, which can interact in vitro with high specificity and affinity with the SH3 domains of the Src kinases, Hck and Lyn, but not other kinases in the same family (43). Recently, the binding surface of Nef, which interacts with the SH3 domain of Hck tyrosine protein kinase, has been mapped and was found to be noncontiguous, a feature not previously observed for SH3-target interactions (18). However, the interaction of Hck and the other tyrosine protein kinases mapped only to the region surrounding the N-terminal tetraproline repeat and did not include the C-terminal PXXP domain located more than 70 residues away. While we did not perform protein binding studies with these mutants, we were unable to detect Hck or Lyn expression by Northern blot analysis in either thymocytes or peripheral blood lymphocytes (data not shown). Thus, it is unlikely that the interaction of these particular kinases can account for our findings.

In our studies, mutation of either proline repeat domain singly yielded a wild-type phenotype, suggesting that conformational changes in these regions following mutation do not alter function. Simultaneous alteration of both SH3 binding domains severely attenuated the virus; however, this could be attributable to an effect on protein stability, since low levels of Nef were detected in cells infected with this mutant in vitro. Initially, it was reported that both these regions were required for high-affinity binding of Hck (43); however, the same group later reinterpreted this data and attributed it to an artifact of refolding of denatured Nef after transfer to a filter (32). The present data would suggest that interaction of cellular factors with these regions is not necessary in vivo. This may be because these particular factors (Hck and Lyn) are not expressed in thymocytes. Interestingly, it has been reported that point mutations of the N-terminal tetraproline repeat motif alone could decrease infectivity but not CD4 down-regulation in vitro (17, 32, 52). Recently, Wiskerchen and Cheng-Meyer (52) reported that the tetraproline repeat region also associates with a cellular serine kinase. However, the C-terminal PXXP domain was not required for this association. Our data indicate that alteration of the tetraproline repeat or the double proline repeat regions is not sufficient to mediate the Nef-minus phenotype in vivo. Recent studies in the SIV system, involving mutation of the single SH3 binding domain in nef, failed to show an effect on pathogenicity (31). Thus, our conclusions obtained with HIV are similar to those reported for SIV.

In the SIV system, mutation of a pair of arginines in Nef known to interact with PAK-related serine kinases lowered the initial burst of virus replication in vivo, but rapid reversion occurred at these positions, and clinical progression to AIDS occurred (46). This suggests that the arginines and the associated activation of PAK are strongly selected for in vivo and are linked to the pathogenicity of SIV. However, our studies of HIV Nef showed that the attenuation conferred by mutations of the paired arginines is not as severe as that in Nef-deleted virus and that reversion of these mutations to wild-type sequences did not occur. We also cannot rule out nonspecific effects on protein levels with this mutant.

Recent work with the hu-SCID model reconstituted with peripheral blood lymphocytes has shown that a mutant bearing a Nef lacking aa 72 to 75 is attenuated in this system (24). This region is encompassed in our deletion mutant 5. However, we cannot conclude that this region is critical for Nef function in our in vivo model, due to the low protein expression of our mutant.

In conclusion, we have mapped HIV in vivo pathogenicity to two regions of Nef, including the myristoylation site and the region encompassed by deletion 3 (aa 41 to 49 of Nef). The importance of the myristoylation site probably relates to the need for appropriate subcellular localization of the protein. It is unclear why deletion 3 conveyed an attenuated phenotype; however, this was not due to nonspecific alterations in the levels of Nef protein, as infected cells contained comparable levels to cells infected with wild-type virus. Further studies are required to determine how this region affects pathogenicity. Importantly, we have eliminated the role of several regions of Nef in in vivo pathogenicity. Notably, the second ATG site, the putative PKC phosphorylation site (at aa 80), and the protease cleavage site, in addition to the above-mentioned proline repeat regions, were not required for HIV to replicate and deplete thymocytes in the SCID-hu mouse. Additional studies with this system will be important to fully understand how Nef is involved in HIV pathogenesis in the thymus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H.-G. Krausslich and R. Welker for sharing their data regarding in vitro protein expression of mutant viruses. We also thank B. D. Jamieson for critical review of the manuscript, A. Kacena and N. Negoitas for technical assistance, and W. Aft for editorial and word-processing assistance. We thank M. Liu and J. Taylor for statistical analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AI36059) and the UCLA CFAR (NIH AI28697). G.M.A. is a Pediatric AIDS Scholar, and J.A.Z. is an Elizabeth Glaser Scientist supported by the Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldrovandi G M, Feuer G, Gao L, Kristeva M, Chen I S Y, Jamieson B, Zack J A. HIV-1 infection of the SCID-hu mouse: an animal model for virus pathogenesis. Nature. 1993;363:732–736. doi: 10.1038/363732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldrovandi G M, Zack J A. Replication and pathogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory gene mutants in SCID-hu mice. J Virol. 1996;70:1505–1511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1505-1511.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachelerie F, Alcami J, Hazan U, Israel N, Goud B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J-L. Constitutive expression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) nef protein in human astrocytes does not influence basal or induced HIV long terminal repeat activity. J Virol. 1990;64:3059–3062. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3059-3062.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur A S, Sawai E T, Dazin P, Fantl W J, Cheng-Mayer C, Peterlin B M. HIV-1 Nef leads to inhibition or activation of T cells, depending on its intracellular localization. Immunity. 1994;1:373–384. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodeus M, Marie-Cardine A, Bougeret C, Ramos-Morales F, Benarous R. In vitro binding and phosphorylation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein by serine/threonine protein kinase. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1337–1344. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-6-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonyhadi M L, Rabin L, Salimi S, Brown D A, Kosek J, McCune J M, Kaneshima H. HIV induces thymus depletion in vivo. Nature. 1993;363:728–736. doi: 10.1038/363728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cann A J, Koyanagi Y, Chen I S Y. High efficiency transfection of primary human lymphocytes and studies of gene expression. Oncogene. 1988;3:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowers M Y, Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Fitch N J S, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. Optimal infectivity in vitro of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires an intact nef gene. J Virol. 1994;68:2906–2914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2906-2914.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A, Dwyer D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Z, Lang S M, Sasseville V G, Lackner A A, Ilyinskii P O, Daniel M D, Jung J U, Desrosiers R C. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell. 1995;82:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini G, Robert-Guroff M, Ghrayeb J, Chang N T, Wong-Staal F. Cytoplasmic localization of the HTLV-III 3′ orf protein in cultured T cells. Virology. 1986;155:593–599. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freund J, Kellner R, Houthaeve T, Kalbitzer H R. Stability and proteolytic domains of Nef protein from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:811–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fultz P N. Replication of an acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus activates and induces proliferation of lymphocytes. J Virol. 1991;65:4902–4909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4902-4909.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaedigk-Nitschko K, Schon A, Wachinger G, Erfle V, Kohleisen B. Cleavage of recombinant and cell derived human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) Nef protein by HIV-1 protease. FEBS Lett. 1995;357:275–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01370-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Downregulation of cell surface CD4 by nef. Res Virol. 1992;143:52–55. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(06)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs J S, Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. Construction and in vitro properties of HIV-1 mutants with deletions in “nonessential” genes. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 1994;10:343–350. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith M A, Warmerdam M T, Atchison R E, Miller M D, Greene W C. Dissociation of the CD4 downregulation and viral infectivity enhancement functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef. J Virol. 1995;69:4112–4121. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4112-4121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grzesiek S, Bax A, Clore G M, Groneborn A, Hu J-S, Kaufman J, Palmer I, Stahl S, Wingfield P. The solution structure of HIV-1 Nef reveals an unexpected fold and permits delineation of the binding surface for the SH3 domain of Hck tyrosine protein kinase. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guy B, Kieny M P, Riviere Y, Le Peuch C, Dott K, Girard M, Montagnie L, Lecocq J-P. HIV F/3′ orf encodes a phosphorylated GTP-binding protein resembling an oncogene product. Nature. 1987;330:266–269. doi: 10.1038/330266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammes S R, Dixon E P, Malim M H, Cullen B R, Greene W C. Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence against its role as a transcriptional inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9549–9553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Characterization of nef sequences in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1995;69:93–100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.93-100.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamieson B D, Aldrovandi G M, Planelles V, Jowett J B M, Gao L, Bloch L M, Chen I S Y, Zack J A. Requirement of HIV-1 nef for in vivo replication and pathogenesis. J Virol. 1994;68:3478–3485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3478-3485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaminchik J, Margalit R, Yaish S, Drummer H, Amit B, Sarver N, Gorecki M, Panet A. Cellular distribution of HIV type 1 Nef protein: identification of domains in Nef required for association with membrane and detergent-insoluble cellular matrix. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 1994;10:1003–1010. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawano Y, Tanaka Y, Misawa N, Tanaka R, Kira J-I, Kimura T, Fukushi M, Sano K, Goto T, Nakai M, Kobayashi T, Yamamoto N, Koyanagi Y. Mutational analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory genes: requirement of a site in the nef gene for HIV-1 replication in activated CD4+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:8456–8466. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8456-8466.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kestler H W, III, Ringler D J, Kazuyasu M, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohleisen B, Neumann M, Herrmann R, Brack-Werner R, Krohn K J, Ovod V, Ranki A, Erfle V. Cellular localization of Nef expressed in persistently HIV-1-infected low-producer astrocytes. AIDS. 1992;6:1427–1436. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kollmann T R, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Zhuang X, Kim A, Hachamovitch M, Smarnworawong P, Rubinstein A, Goldstein H. Disseminated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in SCID-hu mice after peripheral inoculation with HIV-1. J Exp Med. 1994;179:513–522. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krohn K J E, Ovod V, Langerstedt A, Saarialho-Kere U, Ranki A, Gombert F O, Jong G, Molling K. Expression kinetics and cellular localization of HIV tat and nef proteins in relation to expression of viral structural mRNA and viral particles. Vaccines. 1991;91:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang S M, Iafrate A J, Stahl-Hennig C, Kuhn E M, Nisslein T, Kaup F-J, Haupt M, Hunsmann G, Skowronski J, Kirchhoff F. Association of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef with cellular serine/threonine kinases is dispensable for the development of AIDS in rhesus macaques. Nat Med. 1997;3:860–865. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee C, Leung B, Lemmon M A, Zheng J, Cowburn D, Kuriyan J, Saksela K. A single amino acid in the SH3 domain of Hck determines its high affinity and specificity in binding to HIV-1 Nef protein. EMBO J. 1995;14:5006–5015. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCune J M, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Schultz L D, Lieberman M, Weissman I L. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241:1632–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller M D, Warmerdam M T, Gaston I, Greene W C, Feinberg M B. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murti K G, Brown P S, Ratner L, Garcia J V. Highly localized tracks of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef in the nucleus of cells of a human CD4+ T-cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11895–11899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Namikawa R, Weilbaecher K N, Kaneshima H, Yee E J, McCune J M. Long-term human hematopoiesis in the SCID-hu mouse. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1055–1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niederman T M, Hastings W R, Ratner L. Myristoylation-enhanced binding of the HIV-1 Nef protein to T cell skeletal matrix. Virology. 1993;197:420–425. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ovod V, Lagerstedt A, Ranki A, Gombert F O, Spohn R, Tahtinen M, Jung G, Krohn K J. Immunological variation and immunohistochemical localization of HIV-1 Nef demonstrated with monoclonal antibodies. AIDS. 1992;6:25–34. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandori M W, Fitch N J S, Craig H M, Richman D D, Spina C A, Guatelli J C. Producer-cell modification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Nef is a virion protein. J Virol. 1996;70:4283–4290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4283-4290.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Planelles V, Haislip A, Withers-Ward E S, Stewart S A, Xie Y, Shah N P, Chen I S Y. A new reporter system for detection of viral infection. Gene Ther. 1995;2:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poulin L, Levy J A. The HIV-1 nef gene product is associated with phosphorylation of a 46 kD cellular protein. AIDS. 1992;6:787–791. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranki A, Lagerstedt A, Ovod V, Aavik E, Krohn K J. Expression kinetics and subcellular localization of HIV-1 regulatory proteins Nef, Tat and Rev in acutely and chronically infected lymphoid cell lines. Arch Virol. 1994;139:365–378. doi: 10.1007/BF01310798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saksela K, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in HIV-1 Nef bind to SH3 domains of a subset of Src kinases and are required for the enhanced growth of Nef+ viruses but not for down-regulation of CD4. EMBO J. 1995;14:484–491. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawai E T, Baur A S, Peterlin B M, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. A conserved domain and membrane targeting of Nef from HIV and SIV are required for association with a cellular serine kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15307–15314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawai E T, Baur A, Struble H, Peterlin B M, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1539–1543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawai E T, Khan E H, Montbriand P M, Peterlin B J, Cheng-Mayer C, Luciw P A. Activation of PAK by HIV and SIV Nef: importance for AIDS in rhesus macaques. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shugars D C, Smith M S, Glueck D H, Nantermet P V, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch F, Swanstrom R. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef gene sequences present in vivo. J Virol. 1993;67:4639–4650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4639-4650.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Chowers M Y, Guatelli J C, Richmond D D. The importance of nef in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication from primary quiescent CD4 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:115–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanley S K, McCune J M, Kaneshima H, Justement J S, Sullivan M, Boone E, Baseler M, Adelsberger J, Bonyhadi M, Orenstein J, Fox C H, Fauci A S. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of the human thymus and disruption of the thymic microenvironment in the SCID-hu mouse. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1151–1163. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welker, R., M. Harris, B. Cardel, and H.-G. Krausslich. Virion incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is mediated by a bipartite membrane targeting signal and correlates with enhancement of viral infectivity. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Welker R, Kottler H, Kalbitzer H R, Krausslich H G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein is incorporated into virus particles and specifically cleaved by the viral proteinase. Virology. 1996;219:228–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiskerchen M, Cheng-Mayer C. HIV-1 Nef association with cellular serine kinase correlates with enhanced virion infectivity and efficient proviral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1996;224:292–301. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zack J A, Arrigo S J, Weitsman S R, Go A S, Haislip A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zack J A, Haislip A, Krogstad P, Chen I S Y. Incompletely reverse transcribed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes in quiescent cells can function as intermediates in the retrovirus life cycle. J Virol. 1992;66:1717–1725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1717-1725.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zazopoulos E, Haseltine W A. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6634–6638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]