Abstract

A combination of chemotherapy with immunotherapy has been proposed to have better clinical outcomes in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC). On the other hand, chemotherapeutics is known to have certain unwanted effects on the tumor microenvironment that may mask the expected beneficial effects of immunotherapy. Here, we have investigated the effect of gemcitabine (GEM), on two immune checkpoint proteins (PD-L1 and PD-L2) expression in cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and pancreatic cancer cells (PCCs). Findings of in vitro studies conducted by using in-culture activated mouse pancreatic stellate cells (mPSCs) and human PDAC patients derived CAFs demonstrated that GEM significantly induces PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression in these cells. Moreover, GEM induced phosphorylation of STAT1 and production of multiple known PD-L1-inducing secretory proteins including IFN-γ in CAFs. Upregulation of PD-L1 in PSCs/CAFs upon GEM treatment caused T cell inactivation and apoptosis in vitro. Importantly, Statins suppressed GEM-induced PD-L1 expression both in CAFs and PCCs while abrogating the inactivation of T-cells caused by GEM-treated PSCs/CAFs. Finally, in an immunocompetent syngeneic orthotopic mouse pancreatic tumor model, simvastatin and GEM combination therapy significantly reduced intra-tumor PD-L1 expression and noticeably reduced the overall tumor burden and metastasis incidence. Together, the findings of this study have provided experimental evidence that illustrates potential unwanted side effects of GEM that could hamper the effectiveness of this drug as mono and/or combination therapy. At the same time the findings also suggest use of statins along with GEM will help in overcoming these shortcomings and warrant further clinical investigation.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03562-9.

Keywords: Statins, Immune-checkpoint, Immunotherapy, PDAC, JAK-STAT, Exosome

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common type of pancreatic cancer with a reported 5-year survival rate of 11% for all stages combined [1]. With minimal change in mortality rate and increasing trend in incidence, PDAC will become the second leading cause of cancer related death by 2030 [2]. Surgery and combination therapy are the major therapeutic options in patients imparting long-term survival benefits but in due course, tumor relapses and the second line based therapy is limited [3, 4]. In recent years, immunotherapy has paved its way in combination with radiation/chemotherapy leading to a shift in the overall survival of patients in various cancers, especially solid tumors including melanoma and lung cancer [5–7].

Pancreatic cancer is labeled as an “immune resistant or immunologically cold tumor” due to lack of intratumoral active effector T-cell [8, 9]. Immune checkpoint proteins (PD-L1 and PD-L2) expressed on CAFs or cancer cells when bind to PD-1 on T cells cause anergy in them [10, 11]. In many of the tumors, chemotherapy can have a dual impact either beneficial or detrimental, which can be deciphered by immunogenic cell death or induction of immunosuppressive proteins like PD-L1/PD-L2 overexpression. For instance, Doi et al., have shown that treatment with various anti-cancer drugs like gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and 5-Flurouracil enhanced the surface expression of PD-L1 protein in AsPC-1, MIAPaCa-2, and Pan02 (PCCs) through JAK2/STAT1 pathway [12]. Another study by Azad et al., demonstrated that the treatment of murine PCCs (KPC and Pan02) with radiation therapy and GEM upregulated PD-L1 expression [13]. In addition to cancer cells, chemotherapeutic drugs are also shown to induce immune checkpoint protein expression in stromal cells. In an elegant study, Roux et al. [14] showed that PD-L1 expression in macrophages was enhanced upon treatment with reactive oxygen species (ROS) inducers such as paclitaxel or buthionine sulfoximine. However, the effect of chemotherapeutics on the expression of checkpoint proteins in CAFs and/or normal pancreas associated fibroblast is understudied.

GEM has been the most commonly used, single chemotherapeutic agent in pancreatic cancer. However, the response rate for only GEM-therapy is very poor [15]. At the same time, during systemic administration of chemotherapy, both stromal cells and cancer cells get exposed to the drugs. CAFs are the principal stromal cells contributing to cancer growth, survival, metastasis, and chemoresistance (CR). The fibro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment (known as desmoplasia) is believed to be a major contributor to chemo and immunotherapy refractoriness of this tumor [16, 17]. A recent study has shown that exosomes secreted by GEM-treated CAFs promote proliferation and drug resistance of PCCs, furthermore GEM-treated CAFs induced inflammatory genes and enhanced pro-tumorigenic properties [18–20]. Bulle et al. [21] have identified upregulation of PD-L1 expression in stromal cells of GEM-treated animals without a clear distinction about the type of stromal cells that responded to GEM-mediated PD-L1 expression. Hence a better understanding of the unwanted effects of GEM on activated CAFs might provide rationale to design novel therapeutic approaches to overcome the limitation of GEM therapy and provide enhanced patient outcomes.

Statins are cholesterol lowering drugs that inhibit HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A) reductase, thereby reducing cholesterol biosynthesis. In multiple mouse cancer models, statins were found to synergize with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. For example, Lim et al. [22] have reported in their study that cholesterol-lowering agents like simvastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, and lovastatin could reduce PD-L1 expression in lung cancer and melanoma cell lines. Additionally, simvastatin could increase stress-related cell death in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and improve CD8+ T cells infiltration and survival of tumor-bearing mice in triple combination with cisplatin, anti-programmed cell death 1 receptor (anti-PD-1) antibody [23].

Although statin-mediated PD-L1 suppression in cancer cells has been reported, the effect on PD-L1 expression in CAFs or drug-induced PD-L1 in CAFs and cancer cells is not evaluated. Based on the aforementioned background and rationale, the major objectives of our study were to (i) check the effect of GEM on PD-L1/PD-L2 expression in PSCs/CAFs and cancer cells, (ii) to understand the role of PD-L1 on the pathophysiological properties of CAFs/cancer cells in the context of immune cells and (iii) to evaluate the effect of statins on PD-L1 expression in PSCs/CAFs and cancer cells. The findings of the study indicate combining statins with GEM could enhance the overall therapeutic outcome by suppressing an unwanted immunosuppressive effect of GEM therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human PCC lines (MIAPaCa-2, BxPC-3, AsPC-1, SW1990) were purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC), while PANC-1 cells were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). MIAPaCa-2, AsPC-1, PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), and BxPC-3 was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. UN-KC-6141 cells were gifted by Dr. SK Batra, UNMC, USA [24]. Human Cancer Associated Fibroblasts (hCAFs) were isolated and characterized using the previous protocol [25]. Mouse pancreatic stellate cells (mPSCs) and hCAFs were cultured in Stellate Cell Medium (5301, Sciencell) supplemented with 2% FBS.

GEM hydrochloride was dissolved in water (G6423, sigma) and 5FU (F6627-5G, Sigma), PTX (T7402, Sigma) were reconstituted in DMSO. All the statins (Enzo) were dissolved in DMSO and Recombinant IFN-γ for human (285-IF, R&D Systems) and mice (485-MI, R&D Systems) were reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mouse pancreatic stellate cells (mPSCs) isolation

mPSCs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice. To isolate mPSCs, the whole pancreas was dissected and collected in PBS containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin following sterile conditions. Pancreas was digested and suspended into single cells to isolate mPSCs according to the established protocol, through density gradient centrifugation method [26, 27]. To enrich the mPSCs population, the cells were resuspended in a FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS) to collect/analyze vitamin A positive cells based on auto-fluorescence using the 405-nm laser using BD FACS Melody (BD Biosciences) [28].

Cell viability assay

hCAFs, mPSCs, and cancer cells were seeded at a density of 5000 cells/well in 96 well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were treated with fresh media containing drugs for the desired time point. At the end of the treatment, MTT (M2128, Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated for 3–4 h in the CO2 incubator. After formazan formation, media were discarded, and Dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μl/well) was used to dissolve the crystal. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using the microplate reader (Multiskan Sky, Thermo Scientific).

RNA isolation and qPCR

The treated cells were harvested in TRI Reagent and Direct-zol™ RNA Miniprep was used to extract total RNA (R2073, Zymo Research). The isolated RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and a maximum of 2 μg of RNA was used for synthesis of cDNA using Reverse Transcription Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (4368814; Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the GoTaq qPCR master mix (A6001/2, Promega). All the primers used are listed in supplementary table 1. GAPDH for mice and 18S for humans were used as the housekeeping genes and the fold change was calculated using the 2(−ΔΔct) method.

Cell surface detection of PD-L1 and PD-L2

After treatment with various chemotherapeutic drugs for desired time points, the cells were washed with PBS, and surface staining was performed. The antibodies used are mentioned in supplementary table 2. Stained cells were washed and analyzed using the flow cytometer (LSR Fortessa, BD Biosciences). Appropriate isotype control was used to set quadrants to assess nonspecific binding. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Protein extraction and western blotting

The cells after treatment were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Total protein was quantified using Bradford and the proteins were resolved using SDS-PAGE. Around 10–35 μg of proteins per sample were loaded into the SDS-PAGE gel for electrophoresis and the proteins were transferred into the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane followed by blocking with 5% BSA. The membranes were then incubated with respective primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with secondary antibodies and visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (k-12043-D10, Western Bright ™ Sirius, Advasta) using chemiDoc (BioRad). The details of the primary antibodies used are mentioned in supplementary table 3.

Immunofluorescence staining (IF)

mPSCs (105 cells/well) were seeded on a coverslip and allowed to settle overnight. The cells were washed with 1 × PBS and fixed with ice-cold acetone and methanol (1:1) for 20 min. Following this 3% BSA was used for blocking and incubated overnight with primary antibodies (α-SMA, 1:2000, A2547, Sigma). The cells were washed to remove the excess primary antibody and incubated with AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibody and mounted with SlowFade Gold Antifade mountant containing DAPI (S36938; Life Technologies) to label the cell nuclei.

For the tissue samples, the paraffin-embedded tissues were subjected to deparaffinization and rehydrated with a gradual reduction of ethanol from 100 to 95% and then to 70%. The sections were blocked with horse serum and probed with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight followed by probing with corresponding secondary antibodies and mounted with DAPI. The slides were visualized using a TCS SP8 STED confocal microscope.

Bio-plex cytokine assay and string analysis

Multiple cytokine analysis was done through Bio-plex pro-human cytokine screening (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). Briefly, hCAFs were treated with 1 µM GEM for 24 h and the supernatant was collected. A total of 50 µL of culture supernatants or cytokine standards were plated in 96 well filter plates, coated with a coupled bead against the specific cytokines and incubated for 30 min on a shaker at 850 rpm at room temperature. A series of washes were given to remove the unbound proteins. Subsequently, detection antibodies were added to the reaction resulting in the formation of sandwiches of antibodies around the target proteins. Streptavidin–phycoerythrin (streptavidin-PE) was then added and the beads were suspended using an assay buffer. Data from the reaction were acquired and analyzed using the Bio-Plex suspension array system (Luminex 100 system) from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). After identification of the upregulated cytokines through Bio-Plex analysis, all the cytokines along with PD-L1/CD274 were evaluated for their interaction with PD-L1 using STRING (STRING, version 12.0, https://string-db.org/) with PPI enrichment p-value < 1.0e-16. STRING analysis predicts protein–protein interactions that include direct physical and indirect functional protein associations. Functional enrichment in the identified network was checked through the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis provided in STRING.

T cell and mPSCs/hCAFs co-culture

The in vitro co-culture system was adopted to replicate the tumor microenvironment. For the co-culture experiment, mouse splenocytes and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), were used to isolate CD8+ T cells. For mouse CD8+T cell isolation, freshly extracted spleen were plunged into small pieces, and single cells were obtained by passing through a 70 μm filter followed by RBC lysis. These cells were purified for mouse CD8+T cells using Dynabeads™ Untouched™ Mouse CD8 Cells reagents (11417D, Invitrogen). For human CD8+ T cell isolation, the whole peripheral blood was subjected to density gradient centrifugation to obtain the fuzzy layer containing the PBMCs. These PBMCs were further subjected to Dynabeads Untouched Human CD8 Cells Kit (11348D, Invitrogen) to obtain CD8+ T cells. T-cell activator CD3/CD28 at an equal ratio of bead to cell and rIL-2 (10 ng/ml) were used to stimulate CD8+T cells in both mice and human for 48 h before co-culture with mPSCs/hCAFs. The ratio of mPSCs/ CAFs and T cells was 1: 5.

To detect the proliferation of T cells, CFSE, a cell division tracking dye was used. 1 × 106 CD8+ T cells were optimally stained with 5 μM dye, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 20 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding cold medium. The stimulated CFSE-labeled cells were used as a control. After the completion of co-culture, the cells were labeled with specific marker and detected using flow cytometry. InVivoMAb anti-mouse PD-L1 (B7-H1) (BE0101, Bioxcell) or isotype control (BE0090, Bioxcell) were used to block the surface PD-L1 expressed on mPSCs.

For the apoptosis assay, cells were stained with annexin V/7AAD after the completion of co-culture to distinguish the cells in different phases of apoptosis.

Animal and tumor models

To generate a fibrotic tumor that replicates the human pancreatic cancer environment, UN-KC-6141 cells and isolated mPSCs were co-injected/implanted orthotopically in the ratio of 1:2 (cancer cells:mPSCs) in C57BL/6 mice. Precisely, the mice were anesthetized, and a small (∽1 cm) incision was made in the left abdominal flank. The skin and the abdominal muscle were lifted to visualize the spleen and the pancreas. UN-KC-6141 and mPSCs resuspended in 50 μl PBS were injected into the splenic lobe of the pancreas and the wounds were closed. The mice were segregated into four different groups: Control (Methylcellulose), GEM, Simvastatin (SIM), or a combination of GEM and SIM. The mice were treated with vehicle, GEM (50 mg/kg, i.p), and/or SIM (50 mg/kg, oral gavage) at an interval of 3 days. SIM was suspended in methylcellulose before administration.

On the last day, the tumor was harvested, cut into small pieces followed by digestion with collagenase (Sigma) at 37 °C for 40 min. RBCs were removed using RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience) and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer. The collected cells were taken for PD-L1 expression and TILs through flow cytometry. The antibodies used are mentioned in supplementary table 2. Tumor sections were taken for histological analysis and liver, kidney, lung, diaphragm, peritoneum, and spleen were examined for metastases.

Statistics

All the in vitro experiments conducted with various drugs were performed for a minimum of three times with technical triplicates. The representative data presented show results obtained from one set of experiments done in triplicate. Results are represented as means ± SD. Comparisons between groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni comparisons test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA).

Study approval

Prior to conducting any animal experiment, approval from Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC) (DBT-ILS, Bhubaneswar, India) was obtained (ref no. ILS/IAEC-208-AH/DEC-20 and ILS/IAEC-295-AH/NOV-2022).

Ethical approval for research involving the isolation of PBMCs from human volunteers were taken from Institutional Human Ethical Committee (DBT-ILS, Bhubaneswar, India) (ref no:118/HEC/2022).

Results

GEM is a potent inducer of immune checkpoints (PD-L1 and PD-L2) expression in mPSCs and hCAFs

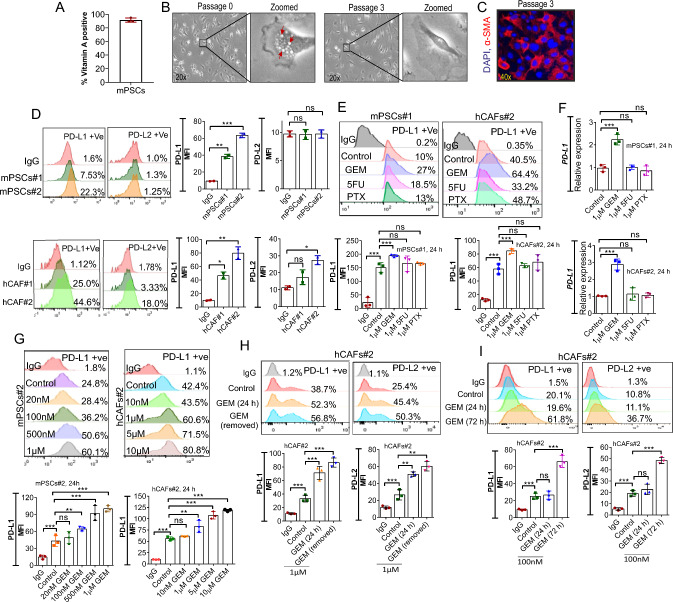

Prior studies have shown that cancer cells, PSCs/CAFs express immunosuppressive markers B7-H1/PD-L1 and B7-DC/PD-L2, members of the B7 family [12, 29–31]. One of the major objectives of our study was to check the effect of different chemotherapeutics on PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression in mPSCs and hCAFs. Initially, the basal level of these protein expressions was checked in both cells. To further enrich the mPSCs population, the cells were sorted based on their autofluorescence property, which is a unique characteristic of stellate cells. The blue-green autofluorescence is due to the storage of vitamin A (Vit. A) in lipid droplets [32, 33]. The sorted cells showed ~ 91% of quiescent mPSCs in each isolation (Fig. 1A). Within 24 h of culture (Passage 0), the majority of the cells had Vit. A containing droplet, observed under a bright field microscope (Fig. 1B). After the first passage (passage 3), these droplets were lost and the cells were positive for α-SMA expression, indicating their activation status (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1.

PD-L1 expressed by mPSCs and PD-L1/PD-L2 by hCAFs gets upregulated upon GEM treatment in vitro. A The bar graph shows the purity of sorted quiescent mPSCs, estimated based on their autofluorescence through flow cytometry, n = 3. B Bright-field image of mPSCs at passage 0 and passage 3 with zoomed images showing presence (red arrow, left) and absence of lipid droplets (right), site for storage of vitamin A in the cytoplasm. C Immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA in mPSCs from passage 3. D mPSCs (upper) and hCAFs (lower) cells stained for PD-L1 and PD-L2 were analyzed through flow cytometry for two different isolates. Data from three different passages of mPSCs and hCAFs were used for analysis. E Flow cytometry analysis of PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right) following treatment with GEM, 5FU and PTX at 1 µM concentration for 24 h. GEM: Gemcitabine; 5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil; PTX: Paclitaxel. F Relative qRT-PCR analysis of PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (upper) and hCAFs (lower) after 24 h of drug treatments. G Histogram and bar graph indicating percentage of PD-L1 positive cells and MFI upon treatment with varying doses of GEM in mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right). H Flow cytometry analysis of hCAFs showing the expression level of PD-L1 and PD-L2 after removal of GEM (24 h treatment/1 µM) followed by 24 h in culture. I Flow cytometry analysis of hCAFs showing elevated expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 when exposed to a low dose of GEM (100 nM) for 72 h. All Data indicate the mean ± SD, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001.

Flow cytometry analysis showed low and varied expression for PD-L1 (~ 5–25%), but PD-L2 was negligible in the case of isolated primary mPSCs in two different isolates (Fig. 1D). In hCAFs the percentage of PD-L1 positive cells (~ 25–50%) was higher compared to PD-L2 expressing cells (~ 3–20%) (Fig. 1D). It was notably found that the expression of PD-L1 was comparatively higher than PD-L2 in the same cell population in hCAFs. Respective MFI quantification for two representative isolates (mPSCs and hCAFs) is depicted in the bar graph (Fig. 1D).

To evaluate the effect of different chemotherapeutic drugs on mPSCs and hCAFs, we treated mPSCs and hCAFs with Gemcitabine (GEM), 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) and Paclitaxel (PTX) for 24 h. Our finding implies that GEM induced higher and significant change in the expression level of PD-L1 in mPSCs (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1E) and both PD-L1 and PD-L2 in hCAFs (P < 0.001, P < 0.05) (Figs. 1E, S1). The above findings were validated by qPCR at the mRNA level and similar results were found in mPSCs (P < 0.001) and hCAFs (P < 0.001) (Figs. 1F, S2). Based on the potent effect of GEM on PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression and one of the most commonly used chemotherapeutics (single or combination) against PCCs, we decided to conduct further detailed studies only with GEM.

Further, the minimum dose of GEM required to induce significant expression of PD-L1 was 100 nM for mPSCs (p < 0.005) and 1 μM for hCAFs (p < 0.005) (Fig. 1G). Similarly, for hCAFs, the minimum dose of 1 μM (p < 0.005) was required to induce PD-L2 expression (p < 0.005) (Fig S3). An increase in PD-L1 and/or PD-L2 in hCAFs and PD-L1 in mPSCs was observed with an increase concentration of GEM, validated through flow cytometry and qPCR analysis (Figs. 1G, S3, S4, S5) but no change in PD-L2 level was observed upon GEM treatment (Fig. S6) in mPSCs. The qRT-PCR data showed a time-dependent increase at mRNA level after exposure to GEM treatment, which was significantly detected at 6 h (p < 0.05) and continued to increase up to 24 h after which no further increase was observed in mPSCs and hCAFs (Figs. S7, S8).

Since we observed an increase in PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression in hCAFs after GEM treatment (Fig. 1G) we wanted to check whether the removal of GEM from the media could lead to the retention of PD-L1 and PD-L2 surface expression. The flow cytometry data revealed that PD-L1 and PD-L2 were retained in hCAFs when the GEM-treated medium (1 μM) was removed after 24 h of treatment (p < 0.005, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1H). In addition, a very low dose of GEM (100 nM) can induce significant expression of PD-L1/PD-L2 in hCAFs, when present in a medium for a longer period (72 h) compared to 24 h induction, validated through flow cytometry (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1I).

Statins are potent suppressors of basal and GEM-induced PD-L1 and/or PD-L2 expression in mPSCs and hCAFs

Statins are reported to inhibit PD-L1 in various cancer cells [22, 34]. Hence, we were interested in evaluating the effect of various statins like Fluvastatin (FLU), Simvastatin (SIM), Atorvastatin (ATOR), Pravastatin (PRAVA), and Lovastatin (LOVA) on basal and GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in mPSCs and PD-L1/PD-L2 in hCAFs. For this, initially, we evaluated the cytotoxic effect of all the statins on these cells. The cell viability assay suggested 2 μM (~ 10% apoptosis) for mPSCs and 3 μM (~ 5% cell death) for hCAFs as minimal cytotoxic dose (Fig. 2A, S9). Among all the statins evaluated, the qRT-PCR data shown in Fig. 2B clearly exhibited a significant effect of both FLU (p < 0.05, p < 0.005) and SIM (p < 0.005, p < 0.001) in reducing PD-L1 expression in both mPSCs and hCAFs (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the expression of PD-L2 in hCAFs was also downregulated in the presence of SIM (p < 0.005) and FLU (p < 0.005) (Fig. S10). The finding was also validated through flow cytometry (Figs. 2C, S11). In addition to this, dose-dependent effects of FLU and SIM in reducing PD-L1 in mPSCs and PD-L1/PD-L2 in hCAFs were noticed through qPCR (Figs. S12, S13, S14).

Fig. 2.

Statins suppressed basal and GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in mPSCs and hCAF. A MTT assay showing the viability of mPSCs after exposure to increasing concentration of various statins for 24 h. B qRT-PCR analysis showing PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (upper) and hCAFs (lower) after exposure to different statins at 2 µM concentration for 24 h. C Representative histogram overlays display the change in PD-L1 expression (% of gated cells) in mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right) upon FLU and SIM treatment while the bar graph represents MFI of the same. D GEM treated mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right) cells were analyzed for the expression level of PD-L1 upon combinatorial treatment with SIM and FLU or alone. E qRT-PCR analysis of PD-L1 for mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right) cells treated with GEM alone or in combination with SIM or FLU as indicated in the graphs. F MTT assay showing the cell viability of mPSCs after exposure to increasing concentration of GEM and SIM in combination for 24 h. G, H Western blot analysis of pSTAT1 and PDL1 in mPSCs (G) and hCAFs (H) cells after treatment with GEM, SIM, and combination of GEM and SIM for 24 h. GEM: 100 nM for mPSCs and 1 μM for hCAFs, SIM: 2 μM for mPSCs and hCAFs. Relative protein expression of PD-L1/β-Actin and p-STAT1/STAT1 is mentioned below each panel. All the experiments are repeated three times independently. All the above data are represented as mean ± SD, one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, n = 3)

As both the statins could effectively reduce the expression of PD-L1 at basal level (Fig. 2B, C), we wanted to check if these drugs can reduce the GEM-induced PD-L1 and/or PD-L2 expression. Flow cytometry analysis showed a significant effect of FLU and SIM in reducing GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (p < 0.001) and hCAFs (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2D). These findings were also validated through qPCR analysis (Fig. 2E). Similarly, in hCAFs the GEM-induced PD-L2 expression was also inhibited by FLU and SIM (p < 0.005) (Figs. S15, S16). The combination of both the drug, SIM/FLU with GEM at the aforementioned concentration did not have any cytotoxic effect on mPSCs or hCAFs as validated through MTT assay (Figs. 2F, S17). Moreover, a combination of GEM and SIM reduced the level of pSTAT1 and PD-L1 indicating that the STAT1 signaling pathway might play an important role in regulating GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (Fig. 2G) and hCAFs (Fig. 2H).

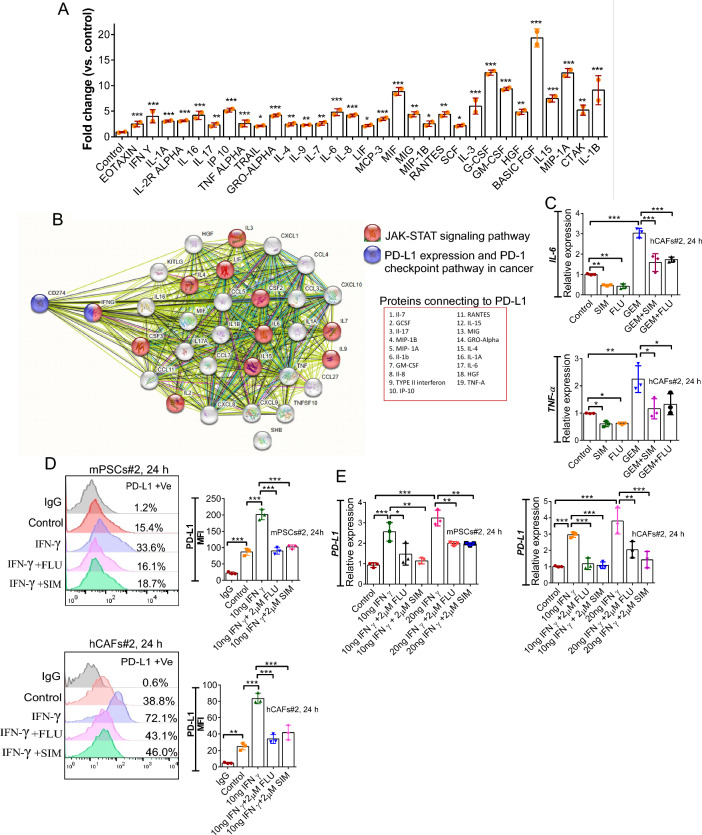

Multiple known immune checkpoint-inducing factors get secreted upon GEM treatment

In one of our studies, we reported that GEM induced the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mouse peritoneal macrophages [35]. GEM is also known to induce the secretion of proteins like VEGF in PCCs [36, 37]. The secretory factors produced by these cells may act in an autocrine and/or paracrine fashion and induce the expression of different other proteins in these cells. Multiple secretory factors are known to have an impact on the expression level of PD-L1/PD-L2 in different cells [38, 39]. Hence, to explore if GEM could upregulate the PD-L1 regulating cytokines in hCAFs, we examined the expression level of multiple secretory factors in the hCAFs conditioned medium (CM). Through Bio-Plex Pro Human cytokine assay, we noticed a significant upregulation of multiple cytokines like TNF-α (~ 2 fold, p < 0.001), IFN-γ (4.5 fold, p < 0.001), and IL-6 (~ 5 fold, p < 0.001) upon GEM treatment (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Cytokines released from hCAFs were altered in presence of GEM. A Conditioned medium (CM) from GEM-treated and untreated hCAFs were analyzed through Bio-Plex Pro Human cytokine assay. The quantification of the mentioned cytokines was assessed from the standard curve. B STRING protein–protein interaction network (https://string-db.org) analysis of upregulated proteins that are linked with PD-L1. The interaction with a medium confidence of 0.4 was considered. C qRT-PCR analysis for the expression of IL-6 (upper) and TNF-α (lower) in hCAFs upon treatment with GEM alone or in combination with SIM or FLU for 24 h. D IFN-γ induced PD-L1 expression in mPSCs (upper) and hCAFs (lower) were measured by flow cytometry in the presence of SIM and FLU. E qRT-PCR analysis comparing relative PD-L1 expression levels between IFN-γ treated and IFN-γ + SIM or IFN-γ + FLU treated mPSCs (left) and hCAFs (right). Data indicates mean ± SD, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001)

To understand the correlation between the upregulated proteins that could have an impact on PD-L1 expression, STRING analysis was done by using all the upregulated proteins/analytes. The results indicated that out of 31 cytokines that are upregulated upon GEM treatment at least 19 are directly connected to PD-L1 (Fig. 3B).

Interestingly, KEGG pathway analysis for the upregulated proteins showed various signaling pathways are being upregulated, among which IL-17, TNF-α, JAK-STAT, and NF-Kappa B are the known regulators of PD-L1 (Fig. 3B) [13, 40, 41].

Earlier reports have established the effects of IL-6 /TNF-α in inducing PD-L1 in various cancer cells like thyroid and melanoma cancer thereby facilitating immune escape in cancer cells [42–45]. Interestingly, both SIM and FLU were efficient in inhibiting GEM-induced IL-6 and TNF-α expression in hCAFs validated through qPCR (Fig. 3C).

The presence of IFN-γ in the tumor microenvironment is reported to upregulate membranous and soluble PD-L1 in various cell types [46–48]. In the current study, SIM and FLU could significantly reduce IFN-γ induced PD-L1 and/or PD-L2 expression in mPSCs and hCAFs. The results were validated through flow cytometry and qPCR (Fig. 3D, 3E, S18, S19).

GEM-induced PD-L1 overexpression in mPSCs and hCAFs prompted T cell inactivation

The functional mechanism of PD-L1/PD-L2 is to inhibit the function of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which is a key adaptive mechanism adopted by PD-L1 or PD-L2 expressing cells to suppress the immune system. Reports are available that illustrate the direct inhibition of CD8+T cells by CD90+ myofibroblasts/fibroblasts cells [49].

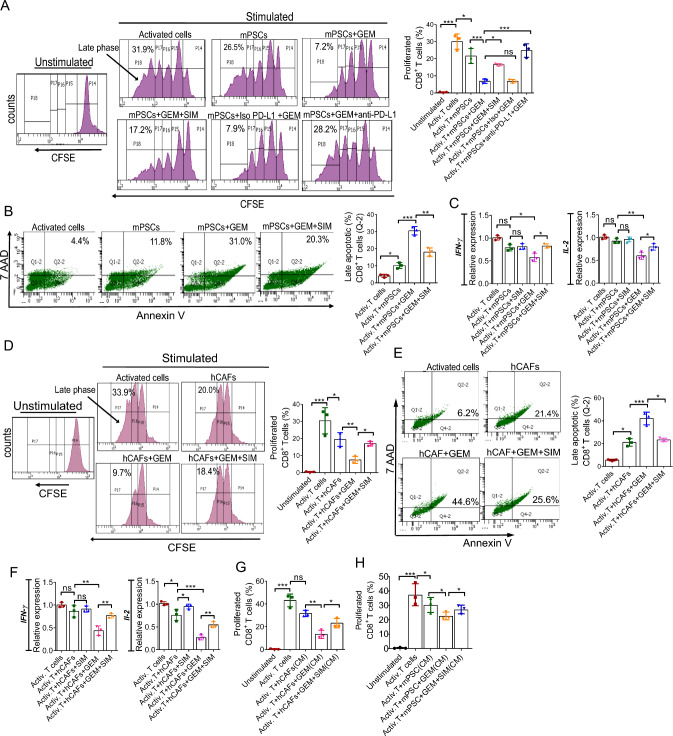

Therefore, we got interested to know whether mPSCs and hCAFs can directly suppress T cell function upon GEM treatment and whether the GEM-induced inhibition of T cells can be rescued in the presence of statins. For this anti-CD3/CD-28 stimulated T cells of mice and human origin were directly co-cultured with GEM-treated mPSCs and hCAFs, respectively. The results depict, mPSCs were able to inhibit T cell proliferation (p < 0.05), which was further inhibited when cultured with GEM-treated mPSCs (p < 0.001), demonstrated by a lesser proportion of cells containing diluted CFSE dye (Fig. 4A). Encouragingly, the presence of SIM in the system significantly rescued the T cell proliferation (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

mPSCs and hCAFs (GEM treated and untreated) suppressed proliferation of active CD8+ T cells. A Proliferation of activated T cells were analyzed by CFSE dye dilution assay in different conditions. GEM: 100 nM, SIM: 2 μM. Bar graph represents the proportion of CFSE cells during the late phase. B Active CD8+ T cells from mice were co-cultured with various conditions and the AnnexinV/7AAD+CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. Activated CD8+ T cells were taken as control. C IFN-γ and IL-2 expression levels in activated CD8+ T cells (mice) were examined by qRT-PCR. D Histogram representing CFSE labeled human PBMC-derived activated CD8+ T cells after indicated treatment. GEM: 1 μM, SIM: 2 μM. Right bar graph showing proportion of CFSE positive cells during the late phase. E Human PBMC-derived activated CD8+T cells were co-cultured with various conditions and the Annexin V/7AAD+CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. F IFN-γ and IL-2 expression levels in the human primary CD8+ T cells were measured by real-time PCR analysis. G, H Proliferation of activated T cells were analyzed by CFSE dye dilution assay cultured with hCAFs (G) and mPSCs (H) conditioned media with different conditions. Bar graph represents the proportion of CFSE positive cells during the late phase. The above data represent the means ± SD, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001)

Further, GEM-treated mPSCs also induced T cell apoptosis (p < 0.001) as analyzed through flow cytometry by staining with annexin V/7AAD (Fig. 4B), whereas the death rate was significantly reduced in the presence of SIM (p < 0.005) (Fig. 4B). Further, IFN-γ and IL-2 were also found to be down-regulated in the presence of mPSCs and mPSCs stimulated with GEM, which got rescued in the presence of statin (Fig. 4C). Similarly, reduced T cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and down-regulated IFN-γ and IL-2 were noticed in human T cells when co-cultured with hCAFs or hCAFs treated with GEM, which got abrogated in the presence of statin (Fig. 4D–F).

To further check whether GEM-stimulated hCAFs or mPSCs effect on T-cells is contact-dependent or not, T-cells were cultured in the presence of GEM-stimulated mPSCs or hCAFs conditioned media (CM). The data shown in Fig. 4G and H suggest secretory factors produced by mPSCs or hCAFs upon GEM treatment are sufficient to induce the inactivation of T cells in vitro and SIM treatment rescued T cell inactivation, validated through T cell proliferation assay (Fig. 4G, H). We predict the presence of exosomal PD-L1 in the CM is partly responsible for the T cell inactivation. The morphology of isolated exosomes and exosomal PD-L1 is validated through TEM imaging and western blotting, respectively (Figs. S20, S21).

Fluvastatin and Simvastatin significantly suppressed GEM and IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells

In pancreatic cancer TME, PD-L1 expressed by cancer cells, immune cells, and other stromal cells can contribute to the overall immunosuppressive environment. Previous studies have reported the expression of PD-L1 by PCCs which gets further upregulated upon GEM treatment [12]. Our data on hCAFs and mPSCs motivated us to examine the effects of statins on basal and GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in PCCs. Our study with various pancreatic cancer cell lines MIAPaCa-2, PANC-1, BxPC-3, SW1990, and AsPC-1 showed varying levels of PD-L1 expression validated through western blotting (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Statins suppressed basal and GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells. A Western blot analysis of PD-L1 expression in different pancreatic cancer cell lines. B Relative qPCR analysis of PD-L1 in BxPC-3 cells after exposure to various statins at 3 µM for 24 h. C Representative histogram overlay displays the change in PD-L1 expression in BxPC-3 upon SIM and FLU treatment and the bar graph represents MFI of the same. D qRT-PCR analysis of PD-L1 in BxPC-3 cells upon exposure to increasing concentration of FLU (left) and SIM (right) for 24 h. E Flow cytometry (left) and qPCR (right) analysis for PD-L1 expression in BxPC-3 cells following treatment with GEM, 5-FU and PTX at 1 µM for 24 h. F BxPC-3 cells were subjected to GEM alone or in combination with FLU or SIM. Histogram was plotted using Flowjo software (% of gated cells). Bar graph representing MFI of the same. G qPCR analysis of PD-L1 transcript in BxPC-3 cells upon exposure to GEM (1 µM, 5 µM) alone or in combination with FLU and SIM. Bar graph showing the fold change. Data were normalized to 18S. H PD-L1 expression in BxPC-3 cells was measured by flow cytometry upon treatment with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and/or statins (FLU and SIM). Representative histograms and quantitative data are shown. I qRT-PCR analysis comparing PD-L1 induction between IFN-γ (10 ng/ml or 20 ng/ml) and IFN-γ + SIM or IFN-γ + FLU treatment, respectively. Data were normalized to 18S. J Western blot analysis of pSTAT1 and PD-L1 in BxPC-3 cells after 24 h treatment with GEM or SIM or combination of GEM + SIM. GEM: 1 μM, SIM: 3 μM. Relative protein expression of PD-L1/β-Actin and p-STAT1/STAT1 is mentioned below each panel. All the above data indicates mean ± SD, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001)

Encouragingly, all the statins used could significantly suppress PD-L1 expression in BxPC-3 cells, whereas only FLU and SIM were potent in suppressing PD-L1 in MIAPaCa-2, validated at the transcript and protein level (Figs. 5B, C, S23, S24). Further in BxPC-3 cells FLU and SIM showed maximum levels of PD-L1 suppression (Fig. 5B) and their effects were enhanced with an increase in the concentration of both the drugs in BxPC-3 and MIAPaCa-2 cells (5D, S25). Both the statins (FLU and SIM) significantly suppressed the surface expression of PD-L1 in BxPC-3/MIAPaCa-2 cells at a minimally cytotoxic concentration (3 µM; Figs. 5C, S22, S24). Further, our data suggest that GEM induced the highest expression of PD-L1 in BxPC-3 cells among the other drugs used (GEM, 5FU, PTX), validated through flow cytometry and qPCR analysis similar to our earlier findings with mPSCs and hCAFs (Fig. 5E). Importantly, both FLU and SIM significantly suppressed GEM-induced PD-L1 expression at the protein and transcript level in BxPC-3 cells (Fig. 5F, G). Similar findings were also observed in MIAPaCa-2 cells (Figs. S27, S28). In addition to this, a dose-dependent increase in PD-L1 expression was observed in BxPC-3 cells upon GEM treatment (Fig. S26). Combination of both the drugs at the mentioned concentration, SIM/FLU with GEM did not have any significant cytotoxic effect as validated through MTT assay (result not shown). Beneficial effects of statins were also observed against IFN-γ-stimulated overexpression of PD-L1 in BxPC-3 and MIAPaCa-2 cells (Figs. 5H, I, S29). Further, SIM suppressed GEM-induced pSTAT1 and PD-L1 upregulation (Fig. 5J).

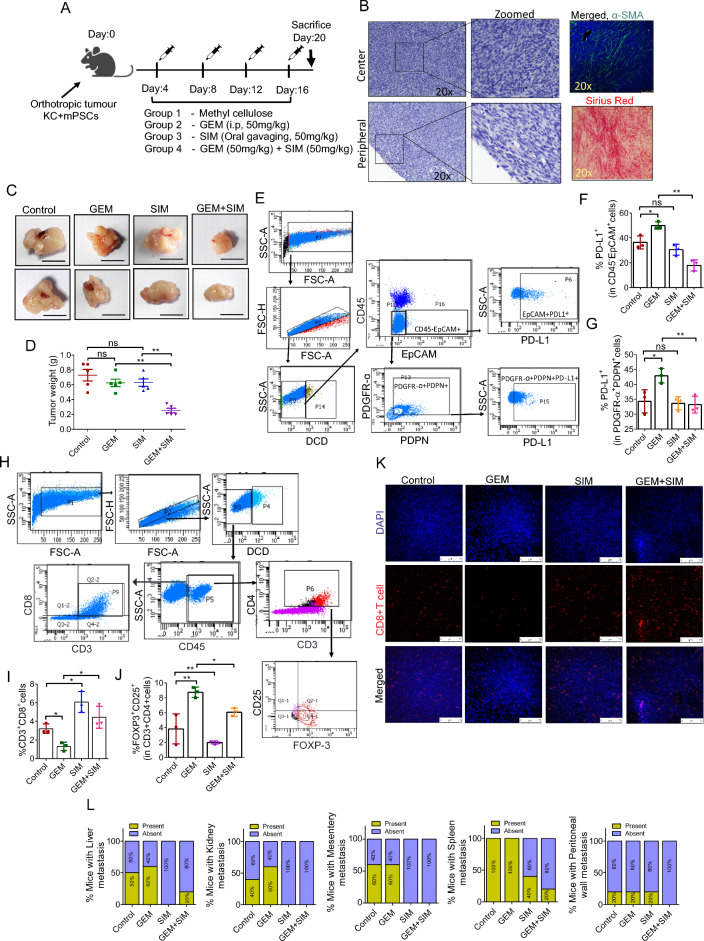

Statin reduced GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells and CAFs and enhanced intra-tumoral T cell infiltration in vivo

Based on our in vitro findings, we hypothesized that in an immunocompetent host, a pancreatic tumor with a high number of CAFs would respond to GEM and SIM combination therapy more effectively than individual drugs. To generate a mouse model of PC with a high number of CAFs, we orthotopically co-injected murine PC cells line (UN-KC-6141) with mPSCs in syngeneic mice in a ratio of 1:2. Schematic representation of experimental timeline and drug treatment protocol used in the study is shown in Fig. 6A (Fig. 6A). Histopathological analysis of tumor tissues obtained from these animals confirmed the successful generation of a desmoplastic tumor with high number of CAFs and deposition of extracellular matrix (Fig. 6B). The tumor size and weight clearly revealed the antitumor effect of GEM and SIM combination therapy (Fig. 6C, D). Flow cytometry analysis of freshly harvested tumor tissues from animals of different groups showed a significant level of PD-L1 surface expression inhibition in the GEM + SIM group in both UN-KC-6141 (cancer) and mPSCs/CAFs (Fig. 6E–G). Moreover, the estimation of tumor-infiltrating CD8+T cells and Treg cell populations in different groups showed an increase in CD8+T cells and a reduced T-reg cell population in GEM + SIM-treated animals. Further increased tumor-associated T-reg cell population was observed in GEM-treated conditions in CAF-rich murine tumor models (Fig. 6H–J). An increase in CD8+T cell infiltration in SIM and SIM + GEM treated tumors was also observed through immunofluorescence (6 K). However, only SIM and SIM + GEM-treated animals had significantly low numbers of T-reg cell populations compared to control or GEM-treated animals (Fig. 6J). Moreover, the combination therapy also noticeably inhibited the incidence of metastasis to different organs (Figs. 6L, S30). Together, these findings corroborated our in vitro data.

Fig. 6.

SIM in combination with GEM inhibited mouse pancreatic tumor in vivo. A Schematic representation of experimental timeline and drug treatment protocol used for in vivo study. B Representative image of H and E staining for various conditions showing microanatomy of tissue, immunofluorescence for α-SMA and sirius red staining for ECM demonstrates presence of intra-tumor fibroblast cells and extent of ECM deposition, respectively. C Images of orthotopic tumors after surgical removal with various conditions. Out of five mice two representative images from each group are shown. D Tumor weight was measured at the end stage (day 20). Data are shown as the mean ± SD, (n = 5 mice), **p < 0.005. E, F, G Gating strategy adopted to select EpCAM+ and PDGFR-α+PDPN+ expressing cells from the live population (E). Bar graph depicting % gated PD-L1 positive EpCAM+ cells (F) and PD-L1 positive PDGFRα+PDPN+ cells (G). (n = 5 mice per group, Data represented for three mice per group; means ± SD, one way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001). H, I, J Gating strategy adopted to select CD8+ T cells and Treg cells from the live population (H). Flow cytometry analysis for infiltrating CD3+CD8+cells (I) and CD4+CD25+FOXP3+cells (J) in the pancreatic tumor of mice from different groups. (n = 5 mice per group, Data represented for three mice per group; means ± SD, one way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001). K Immunofluorescence for infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the tumor tissue treated with various conditions. magnification 40x. L Bar graph depicting percentage of mice with metastasis to different regions after subjecting to various conditions

Discussion

Programmed cell death-ligands 1/2 (PD-L1/PD-L2) are of great clinical value as a therapeutic target and prognostic marker in cancer. We report here that PD-L1/PD-L2 overexpression upon chemotherapy treatment is not only confined to cancer cells but also the pancreatic fibroblast cells. To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence that GEM induced significant expression of PD-L1 in mPSCs and PD-L1/PD-L2 in hCAFs. At the same time, the study corroborates earlier findings in human and murine PCCs [12]. Alteration of PD-L1 and PD-L2 upon GEM treatment provides a rationale for the usage of other adjuvants that could compensate for these side effects in addition to enhancing its cytotoxic effect. In this regard, the findings of this study suggest that statins (SIM & FLU) could effectively suppress GEM-induced PD-L1 expression in activated mPSCs and hCAFs in vitro. Moreover, SIM in combination with GEM significantly suppressed pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

Further, when activated CD8+ T cells were cultured with conditioned medium (CM) harvested from GEM-treated mPSCs/CAFs or directly with GEM-treated mPSCs/CAFs, CD8+ T cell proliferation was significantly impaired. These findings suggest, that PD-L1 present on the cell surface of GEM-treated mPSCs/CAFs and/or secreted PD-L1 from these cells (potentially exosome associated) could bind to PD-1 expressed on T-cells, mediating inactivation of CD8+T cells. In the current study, expression of α-SMA by activated mPSCs indicates that the majority are myofibroblast types, which are known to be negative for major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) expression [50]. However, being primary cells, they express MHC I proteins on their surface, which may play a role in the direct interaction between CD8 +T cells with mPSCs/ hCAFs or exosomes secreted by these cells in an antigen-independent manner. Although earlier studies have shown a possible direct interaction between activated PSCs and T cells, the exact mechanisms associated with this heterotypic cell–cell interaction are not yet well elucidated [51]. Recently, exosomes of cancer cells and hCAFs have been shown to contain immunosuppressive proteins like PD-L1 [52, 53]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that exosomal-PDL1 mimics the immunosuppressive effects of cell-surface PD-L1 and provokes cancer progression via inducing T cell inactivation [54]. Our findings clearly show the expression of PD-L1 in the exosome secreted by mPSCs and hCAFs. Importantly, the level of exosome-associated PD-L1 expression also got upregulated upon GEM treatment. Based on these findings it is highly possible that GEM-induced PD-L1 expression on the surface of mPSCs/hCAFs and/or exosomes secreted by them may significantly contribute to the immunosuppressive phenomenon. Moreover, exosomes secreted by mPSCs/hCAFs may carry MHC I. Interaction between MHC I with TCR enhances the immunosuppressive effects of exosomal PD-L1 on T cells [54]. In this context, the possible role of other adhesion molecules like ICAM-1 which are known to be expressed on PSCs and play an essential role in exosome-induced T cell suppression needs further investigation [55, 56].

A previous study has shown signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) as an important mediator of PD-L1 expression [57], and Azad et al. [13] have shown PD-L1 expression in both KPC and Pan02 cell lines following GEM treatment are mediated through JAK/STAT signaling. The findings of our study showed activation of the STAT1 pathway and production of multiple PD-L1-inducing cytokines like IFN-γ, IL-6, and TNF-α upon GEM treatment. However, the exact connection between all these molecules that are known to induce PD-L1 expression needs further detailed investigation. It is very well established that IFN-γ is a potent cytokine inducer of PD-L1 overexpression, through the JAK-STAT pathway (JAK2 and STAT1) where STAT1 induces transcription factor IRF1 binding to PD-L1 promoter which enhances PD-L1 expression [58–61]. Related to statin-mediated suppression of PD-L1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines expression, our findings suggest that downregulation of STAT-1 phosphorylation by statins could be a potential mechanism. Further, statin-mediated suppression of PD-L1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines occurs through multiple other molecular mechanisms [22, 62, 63]. Interestingly, statins could also suppress cellular and exo-vesicle (EV)-associated PD-L1 by inhibiting EV biogenesis [34]. Hence, the overall effect of statins in the reduction in PD-L1 in mPSCs/hCAFs could be through multiple mechanisms and needs further investigation.

Our in vivo study for the first time showed the benefit of combining statins with GEM to get a therapeutic benefit, by reducing the expression of PD-L1, increasing the infiltration of CD8+T cells, and reducing metastatic burden to other organs. While our study mostly illustrates the role of GEM-induced PD-L1/PD-L2 expression in mPSCs/hCAFs and its effect on CD8+T cells, interestingly we also noticed a decrease in intra-tumor Treg cells population in animals treated with SIM. Although the exact mechanism associated with this event has not been addressed in this study, statins could have direct or indirect effects on T cells through their pleiotropic effects. Functional operation of PD-1 and PD-L1/PD-L2 interaction is one of the important molecular events for the differentiation of CD4+T cells into Treg cells [61], hence, SIM-mediated downregulation of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in cancer and stromal cells may also have contributed to the decreased Treg cells abundance in vivo. In an interesting study Yan C et al. [64] have demonstrated that cholesterol deficiency of T cells in TME leads to T cell exhaustion/dysfunction. However, the overall effect of statins on T-cells in a stroma-rich TME will depend on the direct and indirect effects of statins on T-cells. We believe that future detailed experimental studies may elucidate the effects of statins on various cell types of PDAC TME and its overall consequence on therapeutic outcome.

Our current study has certain limitations which need future investigation to strengthen its clinical significance. To date, no clear data are available regarding immune checkpoint proteins’ expression status in different types or subtypes of normal pancreatic fibroblasts and CAFs. In the context of immune checkpoint protein expression, the myofibroblast like CAFs are known to express these proteins in other malignancies [65]. PSCs are also known to express PD-L1 in vitro [31, 66] and for more than one decade, multiple studies have demonstrated that in-culture activated PSCs phenotypically mimic myofibroblast type CAFs (myCAFs) [26, 67]. The effect of GEM and statins on different other subtypes of mouse and human CAFs is an important aspect, which needs further investigation.

In this study, the effective dose of statins used for in vitro experiments is much higher than the concentrations detected in human plasma. The current study has illuminated a novel aspect of statins that needs further validation in different models. We believe that a much higher concentration of statins in plasma and/or pancreatic tumors is achievable through nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems as reported earlier [68]. For our in vivo experiment, based on available literature we chose a simvastatin dose of 50 mg/kg (by oral gavaging). This dose is much higher than the dose used in humans (0.1–0.4 mg/kg per day). However, earlier studies suggest a requirement of high dose statins use in rodents because of their rapid upregulation of HMG-CoA reductase upon treatment [69, 70]. Various literature has emphasized that mice metabolize simvastatin much more rapidly than humans and therefore lower doses might be effective in humans [71, 72]. Based on these backgrounds, we believe that our study has provided crucial experimental evidence that will open the possibility of using statins with GEM against PDAC by addressing the concerns.

Lastly, this study focuses primarily on the role of PD-L1 in CAFs in immune cells but PD-L2 which also was upregulated upon GEM treatment remains unexplored. The pathway dominating PD-L2 expression in hCAFs upon GEM treatment needs to be further investigated. PD-L1 expression in non-immune cells like cancer cells and CAFs is shown to have an intrinsic role in the overall survival and function of these cells that are independent of immune cells [73, 74]. Our current study only focuses on the role of PSCs/CAFs PD-L1 on the CD8+ T cells. However, its possible intrinsic role in the growth and other properties of PSCs/CAFs themselves needs further investigation. Future studies in these directions may help uncover novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets to improve ICT.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

A.P.Minz is a recipient of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) students research fellowship, Government of India. To create graphical abstract, Biorender.com was used. We are thankful to the support provided by the DBT-ILS core imaging facility and transmission electron microscopy facility. We thank Madan Mohan Mallick, Mr. Sushanta Kumar Swain and Mr. Jajati Ray for their efficient technical support.

Author contribution

AM, DM and MD performed most of the experiments. Conception, design, and development of methodology, data interpretation: SS, AM Patient tissue for CAF isolation: PKS Experiments related to animal work: SS, AM, DM, MS, DP, APM, SM Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: SS, AM, DM, MD, MS, DP, APM, SM, SK, PKS Study supervision: SS.

Funding

The study is partly supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT; BT/PR32122/MED/30/2122/2019) Government of India.

Data availability

All the data are available in the main text and the reagents used are mentioned in the text and supplementary Material. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawada M, et al. Modified FOLFIRINOX as a second-line therapy following gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel therapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06945-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Citterio C, et al. Second-line chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer after first-line gemcitabine-based chemotherapy: a network meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(51):29801. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bear AS, Vonderheide RH, O'Hara MH. Challenges and opportunities for pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2020;38(6):788–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kershaw MH, et al. Enhancing immunotherapy using chemotherapy and radiation to modify the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(9):e25962. doi: 10.4161/onci.25962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi L, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortezaee K. Enriched cancer stem cells, dense stroma, and cold immunity: interrelated events in pancreatic cancer. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021;35(4):e22708. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajina R, Weiner LM. T-cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2020;49(8):1014–1023. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348(6230):56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorchs L, et al. Human pancreatic carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promote expression of co-inhibitory markers on CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:847. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doi T, et al. The JAK/STAT pathway is involved in the upregulation of PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2017;37(3):1545–1554. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azad A, et al. PD-L1 blockade enhances response of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to radiotherapy. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9(2):167–180. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roux C, et al. Reactive oxygen species modulate macrophage immunosuppressive phenotype through the up-regulation of PD-L1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(10):4326–4335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819473116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinemann V. Gemcitabine: progress in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Oncology. 2001;60(1):8–18. doi: 10.1159/000055290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao L, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts treated with cisplatin facilitates chemoresistance of lung adenocarcinoma through IL-11/IL-11R/STAT3 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38408. doi: 10.1038/srep38408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhai J, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts-derived IL-8 mediates resistance to cisplatin in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;454:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards KE, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast exosomes regulate survival and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36(13):1770–1778. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suklabaidya S, Dash P, Senapati S. Pancreatic fibroblast exosomes regulate survival of cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36(25):3648–3649. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toste PA, et al. Chemotherapy-induced inflammatory gene signature and protumorigenic phenotype in pancreatic CAFs via stress-associated MAPK. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14(5):437–447. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulle A, et al. Gemcitabine recruits M2-type tumor-associated macrophages into the stroma of pancreatic cancer. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(3):100743. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim WJ et al (2021) Statins decrease programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) by inhibiting AKT and β-catenin signaling. Cells 10(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kwon M, et al. Statin in combination with cisplatin makes favorable tumor-immune microenvironment for immunotherapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021;522:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres MP, et al. Novel pancreatic cancer cell lines derived from genetically engineered mouse models of spontaneous pancreatic adenocarcinoma: applications in diagnosis and therapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suresh V, et al. MIF confers survival advantage to pancreatic CAFs by suppressing interferon pathway-induced p53-dependent apoptosis. FASEB J. 2022;36(8):e22449. doi: 10.1096/fj.202101953R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suklabaidya S, et al. Characterization and use of HapT1-derived homologous tumors as a preclinical model to evaluate therapeutic efficacy of drugs against pancreatic tumor desmoplasia. Oncotarget. 2016;7(27):41825–41842. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohapatra D, et al. Fluvastatin sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells toward radiation therapy and suppresses radiation- and/or TGF-β-induced tumor-associated fibrosis. Lab Invest. 2022;102(3):298–311. doi: 10.1038/s41374-021-00690-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helms EJ, et al. Mesenchymal lineage heterogeneity underlies nonredundant functions of pancreatic cancer–associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(2):484–501. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yearley JH, et al. PD-L2 expression in human tumors: relevance to Anti-PD-1 therapy in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(12):3158–3167. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshikawa K, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1-positive cancer-associated fibroblasts in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07970-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebine K, et al. Interplay between interferon regulatory factor 1 and BRD4 in the regulation of PD-L1 in pancreatic stellate cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13225. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwaisako K, et al. Origin of myofibroblasts in the fibrotic liver in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(32):E3297–E3305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400062111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helms EJ, et al. Mesenchymal lineage heterogeneity underlies nonredundant functions of pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(2):484–501. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choe EJ et al. (2022) Atorvastatin enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint therapy and suppresses the cellular and extracellular vesicle PD-L1. Pharmaceutics. 14(8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Minz AP, et al. Gemcitabine induces polarization of mouse peritoneal macrophages towards M1-like and confers antitumor property by inducing ROS production. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022;39(5):783–800. doi: 10.1007/s10585-022-10178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan MA, et al. Gemcitabine triggers angiogenesis-promoting molecular signals in pancreatic cancer cells: therapeutic implications. Oncotarget. 2015;6(36):39140–39150. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato H, et al. CCK-2/gastrin receptor signaling pathway is significant for gemcitabine-induced gene expression of VEGF in pancreatic carcinoma cells. Life Sci. 2011;89(17–18):603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartley G, et al. Regulation of PD-L1 expression on murine tumor-associated monocytes and macrophages by locally produced TNF-α. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(4):523–535. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1955-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang X, et al. Role of the tumor microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0928-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma YF, et al. Targeting of interleukin (IL)-17A inhibits PDL1 expression in tumor cells and induces anticancer immunity in an estrogen receptor-negative murine model of breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(5):7614–7624. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonangeli F, et al. Regulation of PD-L1 Expression by NF-κB in Cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:584626. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.584626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang GQ, et al. Interleukin 6 regulates the expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 in thyroid cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(3):997–1010. doi: 10.1111/cas.14752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ju X, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages induce PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer cells through IL-6 and TNF-ɑ signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2020;396(2):112315. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan LC, et al. IL-6/JAK1 pathway drives PD-L1 Y112 phosphorylation to promote cancer immune evasion. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(8):3324–3338. doi: 10.1172/JCI126022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertrand F, et al. TNFα blockade overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 in experimental melanoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):2256. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02358-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pistillo MP, et al. IFN-γ upregulates membranous and soluble PD-L1 in mesothelioma cells: potential implications for the clinical response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(4):410–411. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0245-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiem A, et al. IFN-gamma-induced PD-L1 expression in melanoma depends on p53 expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):397. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moon JW, et al. IFNγ induces PD-L1 overexpression by JAK2/STAT1/IRF-1 signaling in EBV-positive gastric carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17810. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18132-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beswick EJ, et al. TLR4 activation enhances the PD-L1-mediated tolerogenic capacity of colonic CD90+ stromal cells. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2218–2229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang H, et al. Mesothelial cell-derived antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts induce expansion of regulatory T cells in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(6):656–673.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ene-Obong A, et al. Activated pancreatic stellate cells sequester CD8+ T cells to reduce their infiltration of the juxtatumoral compartment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):1121–1132. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng R et al. (2023). Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles mediate immune escape of bladder cancer via PD-L1/PD-1 expression. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Poggio M, et al. Suppression of exosomal PD-L1 induces systemic anti-tumor immunity and memory. Cell. 2019;177(2):414–427.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin Z et al. (2021) Mechanisms underlying low-clinical responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies in immunotherapy of cancer: a key role of exosomal PD-L1. J Immunother Cancer. 9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Masamune A, et al. Activated rat pancreatic stellate cells express intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in vitro. Pancreas. 2002;25(1):78–85. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200207000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang W, et al. ICAM-1-mediated adhesion is a prerequisite for exosome-induced T cell suppression. Dev Cell. 2022;57(3):329–343.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mowen K, David M. Regulation of STAT1 nuclear export by Jak1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(19):7273–7281. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.19.7273-7281.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dorand RD, Petrosiute A, Huang AY. Multifactorial regulators of tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) response. Transl Cancer Res. 2017;6(Suppl 9):S1451–s1454. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2017.11.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mimura K, et al. PD-L1 expression is mainly regulated by interferon gamma associated with JAK-STAT pathway in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/cas.13424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen S, et al. Mechanisms regulating PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):305. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farrukh H, El-Sayes N, Mossman K (2021) Mechanisms of PD-L1 regulation in malignant and virus-infected cells. Int J Mol Sci. 22(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Uemura N, et al. Statins exert anti-growth effects by suppressing YAP/TAZ expressions via JNK signal activation and eliminate the immune suppression by downregulating PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13(5):2041–2054. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao W et al. Statin shapes inflamed tumor microenvironment and enhances immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. JCI Insight, 2022. 7(18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Yan C, et al. Exhaustion-associated cholesterol deficiency dampens the cytotoxic arm of antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(7):1276–1293.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun L, et al. PD-L1 promotes myofibroblastic activation of hepatic stellate cells by distinct mechanisms selective for TGF-β receptor I versus II. Cell Rep. 2022;38(6):110349. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Audenaerde JRM, et al. Interleukin-15 stimulates natural killer cell-mediated killing of both human pancreatic cancer and stellate cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(34):56968–56979. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mantoni TS, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells radioprotect pancreatic cancer cells through β1-integrin signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71(10):3453–3458. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jamil A, et al. Co-delivery of gemcitabine and simvastatin through PLGA polymeric nanoparticles for the treatment of pancreatic cancer: in-vitro characterization, cellular uptake, and pharmacokinetic studies. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019;45(5):745–753. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2019.1569040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agarwal P, et al. Simvastatin prevents and reverses depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):1080–1088. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kita T, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Feedback regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in livers of mice treated with mevinolin, a competitive inhibitor of the reductase. J Clin Invest. 1980;66(5):1094–1100. doi: 10.1172/JCI109938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katano H, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Simvastatin induces apoptosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and delays development of EBV lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(14):4960–4965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahmad T, et al. Simvastatin improves epithelial dysfunction and airway hyperresponsiveness: from asymmetric dimethyl-arginine to asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(4):531–539. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0041OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Escors D, et al. The intracellular signalosome of PD-L1 in cancer cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3:26. doi: 10.1038/s41392-018-0022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heenatigala Palliyage G, et al. Chemotherapy-induced PDL-1 expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes chemoresistance in NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2023;181:107258. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available in the main text and the reagents used are mentioned in the text and supplementary Material. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.