Abstract

Background

High hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level is an independent risk factor for postoperative HBV-associated liver cancer recurrence. We sought to examine whether HBV DNA level and antiviral therapy are associated with survival outcomes in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)based immunotherapy.

Methods

This single-institution retrospective analysis included 217 patients with advanced HBV-related HCC treated from 1 June 2018, through 30 December 2020. Baseline information was compared between patients with low and high HBV DNA levels. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were compared, and univariate and multivariate analyses were applied to identify potential risk factors for oncologic outcomes.

Results

The 217 patients included in the analysis had a median survival time of 20.6 months. Of these HBV-associated HCC patients, 165 had known baseline HBV DNA levels. Baseline HBV DNA level was not significantly associated with OS (P = 0.59) or PFS (P = 0.098). Compared to patients who did not receive antiviral therapy, patients who received antiviral therapy had significantly better OS (20.6 vs 11.1 months, P = 0.020), regardless of HBV DNA levels. Moreover, antiviral status (adjusted HR = 0.24, 95% CI 0.094–0.63, P = 0.004) was an independent protective factor for OS in a multivariate analysis of patients with HBV-related HCC.

Conclusions

HBV viral load does not compromise the clinical outcome of patients with HBV-related HCC treated with anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy. The use of antiviral therapy significantly improves survival time of HBV-related HCC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-022-03254-w.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Programmed cell death protein-1, Hepatitis B virus

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the world’s sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of cancer mortality. The great majority of primary liver malignancies are hepatocellular carcinomas. In most high-risk HCC areas, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a key risk factor for HCC [1]. Previous research has found that a high HBV DNA content is an independent risk factor for HCC patient low survival rate and early recurrence following radical resection [2, 3]. Furthermore, antiviral medication has a synergistic anticancer effect in HBV-infected HCC patients [4, 5] and can improve the survival time of HBV-related HCC patients following hepatectomy [6]. For patients with advanced HBV-related liver cancer treated with anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), few studies have focused on the impact of HBV DNA levels on survival, and data are also lacking regarding whether antiviral treatment affects outcomes of HCC patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy.

The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate the impact of baseline HBV DNA levels and antiviral therapy on the survival of patients with advanced HBV-associated HCC receiving anti-PD-1 therapy.

Methods

Patients and study design

This observational cohort study was conducted on 217 patients with HBV-related HCC (all from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University & Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, China) who received at least one dose of anti-PD-1 therapy between 1 June 2018 and 30 December 2020. Eligibility criteria included: histological or clinical diagnosis of HCC (according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [AASLD] standards); seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg); an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 0–2; and at least one measurable lesion (according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1). Tumor response to treatment was evaluated according to the four response categories of RECIST 1.1: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD). Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) severity was graded using the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. For patients who had prior exposure to antiviral therapy, the antiviral therapy was continued. For patients who had not been previously exposed to antiviral therapy, antiviral therapy was administered after patients were confirmed with positive HBsAg or positive HBV-DNA level. Antiviral treatment was continued even though PD-1 inhibitor therapy was terminated. In this study, 20 patients did not receive antiviral therapy during anti-PD-1 therapy. Among them, 14 patients took antiviral medication at some point prior to anti-PD-1 treatment, but they were poorly compliant and discontinued the medication on their own initiative and did not use it again (no adverse outcomes such as liver decompensation or liver failure that affect OS occurred, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The other 6 patients specifically refused to be prescribed antiviral drugs for personal reasons (personal financial reasons or other reasons), although they were informed in detail about the need for antiviral therapy. Recorded data included the patient’s HBV DNA level, the treatment used, adverse effects, clinical efficacy, antiviral therapy prior to and/or during anti-PD-1 treatment, and patient demographics. Serum HBV DNA level was measured using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method with a lower detection limit of 10 IU/mL.

Definitions

HBV reactivation was defined as one of the following, according to the AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidelines: (i) a ≥ 2 log (100-fold) increase in HBV DNA compared to the baseline level; (ii) HBV DNA ≥ 3 log (1000) IU/mL in a patient with previously undetectable level (since HBV DNA levels fluctuate); or (iii) HBV DNA ≥ 4 log (10,000) IU/mL if the baseline level is not available [7]. The Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) grade was calculated using the formula: (log10 bilirubin × 0.66) + (albumin × − 0.085), where bilirubin is in μmol/L and albumin in g/L. Grading levels were defined as: Grade 1, ALBI ≤ − 2.60; Grade 2, − 2.60 < ALBI score ≤ − 1.39; Grade 3, ALBI score > − 1.39 [8].

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was overall survival (OS), calculated as the time between the start of first anti-PD-1 treatment and the last follow-up visit (30 December 2020), or the date of death, whichever occurred first. Progression-free survival (PFS) was a secondary endpoint, defined as the time from the first anti-PD-1 treatment to the date of disease progression, death, or last follow-up. All eligible patients were included in the analysis of OS and PFS. Continuous and categorical data are summarized as median (range) and frequency (percentage) terms, respectively. The Pearson χ2 analysis or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and any differences in survival were evaluated with a stratified log-rank test. Multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional-hazards model were used to estimate the simultaneous effects of prognostic factors on survival. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26; SPSS, Chicago). Differences were considered statistically significant when the P-value was 0.05 or less. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 217 HBV-related HCC patients treated with anti-PD-1 were included in the study. A detailed list of patients and treatment characteristics is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Median patient age was 54 years (range: 28–79 years) and 190 (87.6%) patients were men. In this study, anti-PD-1 combination therapy was used in 96.3% of patients, with the combination agent consisting mainly of antiangiogenic therapy (90.8%), but also chemotherapy in a small subset (2.8%). Among the patients who could be evaluated for RECIST response, 4.6% had a CR, 31.8% had a PR, 41.9% had SD, and 21.7% had PD (Supplementary Table 1). Of these HBV-related HCC patients, 165 (76.0%) had known baseline HBV DNA levels. 197 (90.8%) patients were on concomitant antiviral therapy during anti-PD-1 treatment, while the remaining 20 (9.2%) were not on antiviral therapy. Supplementary Table 2 indicates irAEs in patients with HCC on anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Among these irAEs, most of them are grade 1–2 and resolved after symptomatic treatment according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for management of immunotherapy-related toxicities [9]. The median OS for all patients was 20.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 14.94–26.26 months) (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and the median PFS was 9.0 months (95% CI 7.19–10.81 months) (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

The clinical characteristics of patients with a baseline HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL and those with a baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL are summarized in Table 1. Patients with > 500 IU/mL HBV DNA had significantly younger age (P = 0.007), higher alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (P = 0.009), lower albumin (P < 0.001), elevated ALT (P = 0.004), higher ALBI grade (P < 0.001), higher Child–Pugh stage B (P = 0.034), more cirrhosis (P = 0.020), seropositive HBeAg status (P = 0.026), larger tumor size (P = 0.011), fewer cycles of PD-1 inhibitor (P = 0.007), and more treatment in first or second line setting (P = 0.020) compared to patients with a baseline HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL. However, there were no statistically significant differences in gender, ECOG performance status, alcohol consumption, total bilirubin, BCLC stage, tumor number, vascular invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, antiviral treatment, PD-1 inhibitor type, treatment modality, PD-1 inhibitors combined with targeted drug, PD-1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy, concomitant local therapy, or clinical response.

Table 1.

Subgroup characteristics of patients with different baseline HBV DNA levels

| Variable | Baseline HBV DNA levels | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 500 IU/mL (n = 87), n (%) | ≤ 500 IU/mL (n = 78), n (%) | ||

| Median age, years (range) | 52 (28–70) | 55 (30–75) | |

| Age (years) (> 60/ ≤ 60) | 16/71 | 29/49 | 0.007 |

| Gender (female/male) | 8/79 | 10/68 | 0.46 |

| ECOG performance status (0–1/2) | 70/17 | 65/13 | 0.63 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes/no) | 41/46 | 38/40 | 0.84 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein levels, ng/mL (≤ 1210/ > 1210) | 49/38 | 59/19 | 0.009 |

| Albumin, g/L (≤ 35/ > 35) | 30/57 | 7/71 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L (< 34/ ≥ 34) | 77/10 | 71/7 | 0.60 |

| ALT, U/L (≤ 40/ > 40) | 34/53 | 48/30 | 0.004 |

| ALBI grade (1/2/3) | 27/56/4 | 45/33/0 | < 0.001 |

| Child–Pugh stage (A/B) | 63/24 | 67/11 | 0.034 |

| BCLC Stage (0-A/B/C) | 18/16/53 | 12/22/44 | 0.29 |

| Liver cirrhosis (yes/no) | 66/21 | 46/32 | 0.020 |

| HBeAg status (seropositive/seronegative) | 12/75 | 3/75 | 0.026 |

| Tumor size, cm (≤ 5/ > 5) | 47/40 | 57/21 | 0.011 |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 19/68 | 14/64 | 0.53 |

| Vascular invasion (yes/no) | 27/60 | 14/64 | 0.052 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis (yes/no) | 32/55 | 27/51 | 0.77 |

| Cycles of PD-1 inhibitor (< 5/ ≥ 5) | 46/41 | 25/53 | 0.007 |

| Treatment baseline (first or second line/above second line) | 59/28 | 39/39 | 0.020 |

| Treatment modality (monotherapy/combination therapy) | 5/82 | 3/75 | 0.84 |

| Antiviral treatment (yes/no) | 79/8 | 73/5 | 0.51 |

| PD-1 inhibitor type | 0.22 | ||

| Camrelizumab | 64 (73.6) | 47 (60.3) | |

| Toripalimab | 9 (10.3) | 14 (17.9) | |

| Sintilimab | 10 (11.5) | 15 (19.2) | |

| Nivolumab | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Keytruda | 1 (1.1) | 0 | |

| Tislelizumab | 1 (1.1) | 0 | |

| PD-1 inhibitors combined with targeted drug | 0.30 | ||

| No | 6 (6.9) | 9 (11.5) | |

| Yes | 81 (93.1) | 69 (88.5) | |

| Apatinib | 53 (65.4) | 34 (49.3) | |

| Anlotinib | 5 (6.2) | 8 (11.6) | |

| Lenvatinib | 12 (14.8) | 17 (24.6) | |

| Regorafenib | 1 (1.2) | 4 (5.8) | |

| Sorafenib | 9 (11.1) | 6 (7.7) | |

| Bevacizumab | 1 (1.2) | 0 | |

| PD-1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy (yes/no) | 2/85 | 1/77 | 1.00 |

| Concomitant local therapy (yes/no) | 46/41 | 37/41 | 0.49 |

| Clinical response | 0.36 | ||

| CR | 2 (2.3) | 5 (6.4) | |

| PR | 27 (31.0) | 29 (37.2) | |

| SD | 35 (40.2) | 32 (41.0) | |

| PD | 23 (26.4) | 12 (15.4) | |

| ORR | 29 (33.3) | 34 (43.6) | |

| DCR | 64 (73.6) | 66 (84.6) | |

Impact of baseline HBV DNA levels on disease progression and survival in patients with advanced HBV-associated HCC treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to describe OS (not reached [NR] vs 18.4 months, HR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.19–0.79, P = 0.0097) and PFS (9.8 vs 6.0 months, HR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.43–1.07, P = 0.093) for patients with baseline HBV DNA levels ≤ 500 IU/mL and > 500. Log-rank tests were done to compare the cumulative survival distributions (Supplementary Fig. 3) of baseline level groups. However, as the log-rank test is a univariate analysis, it ignores differences between groups in confounding factors. Thus, a Cox proportional risk regression model was done to adjust for confounders. Results of the adjusted multiple Cox proportional hazard regression for OS and PFS in patients with HCC with known baseline HBV DNA levels are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. After adjusting for possible confounders, baseline HBV DNA level was not significantly associated with OS (adjusted HR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.29–2.02, P = 0.59) or PFS (adjusted HR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.43–1.07, P = 0.098). According to the multivariate analysis, antiviral treatment (P = 0.002), lower ECOG performance status (P < 0.001), and absence of vascular invasion (P < 0.001) were associated with improved OS (Table 2). Further multivariate regression analysis indicated that age (P = 0.028), ECOG performance status (P < 0.001) and extrahepatic metastasis (P = 0.029) were all associated with PFS (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for OS in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma patients who had known baseline HBV DNA levels

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Group (≥ 500 IU/mL versus < 500 IU/mL) | 0.013 | 0.37 (0.17–0.81) | 0.59 | 0.77 (0.29–2.02) |

| Antiviral treatment (no versus yes) | 0.010 | 0.27 (0.10–0.73) | 0.002 | 0.18 (0.06–0.52) |

| Age (years) (> 60 versus ≤ 60) | 0.098 | 2.26 (0.86–5.94) | ||

| Gender (female versus male) | 0.98 | 1.01 (0.31–3.37) | ||

| Alcohol consumption (yes versus no) | 0.074 | 2.05 (0.93–4.52) | ||

| ECOG performance status (0 + 1 versus 2) | 0.00 | 8.68 (3.20–23.58) | 0.00 | 11.87 (3.96–35.57) |

| AFP ng/mL (≥ 1210 versus < 1210) | 0.11 | 0.55 (0.26–1.15) | ||

| HBeAg status (positive versus negative) | 0.001 | 0.24 (0.10–0.56) | 0.21 | 0.52 (0.19–1.44) |

| ALBI grade (1versus 2 + 3) | 0.007 | 3.21 (1.37–7.51) | 0.54 | 1.41 (0.48–4.14) |

| Child–Pugh stage (A versus B) | 0.21 | 1.68 (0.74–3.77) | ||

| BCLC Stage (0 + A versus B + C) | 0.12 | 5.00 (0.68–36.90) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis (yes versus no) | 0.22 | 0.59 (0.25–1.37) | ||

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L (< 34 versus ≥ 34) | 0.63 | 1.30 (0.45–3.74) | ||

| Albumin, g/L (≤ 35 versus > 35) | 0.001 | 0.29 (0.14–0.60) | 0.075 | 0.44 (0.18–1.09) |

| ALT, U/L (≤ 40 versus > 40) | 0.042 | 2.15 (1.03–4.52) | 0.94 | 1.03 (0.45–2.39) |

| Vascular invasion (yes versus no) | 0.001 | 0.30 (0.14–0.61) | 0.00 | 0.23 (0.10–0.52) |

| Tumor size, cm (≤ 5 versus > 5) | 0.14 | 0.58 (0.29–1.20) | ||

| Tumor number (Multiple versus Single) | 0.13 | 0.33 (0.08–1.39) | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis (yes versus no) | 0.12 | 0.56 (0.27–1.16) | ||

| Treatment modality (mono versus combined) | 0.41 | 0.63 (0.21–1.87) | ||

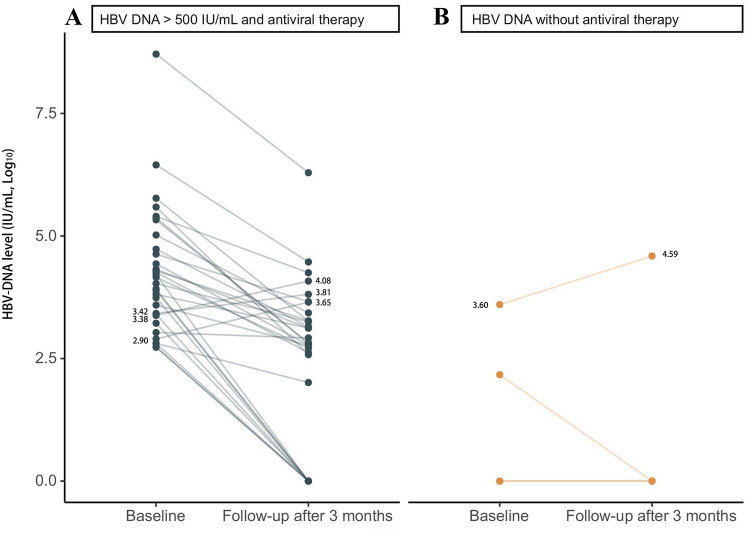

Kinetics of HBV load during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

Sixty-seven patients (40.6%) underwent viral load monitoring following anti-PD-1 blockade among 165 HBV-related HCC patients with known baseline HBV DNA levels, and patients were classified into three categories: 1) baseline HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL on antiviral therapy (n = 31); 2) baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL on antiviral therapy (n = 32); and 3) HBV without antiviral therapy (n = 4). In patients with baseline HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL on antiviral therapy, no case experienced HBV reactivation during anti-PD-1 treatment. Of the 32 patients with baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL who started antiviral therapy simultaneously with anti-PD-1 treatment, three patients developed an increase in HBV viral load, but none met the criteria for HBV reactivation (Fig. 1A). HBV DNA levels were undetectable at later follow-up in these three patients. Of the four patients without antiviral therapy (Fig. 1B), two had an undetectable HBV viral load at baseline and maintained serum HBV DNA at an undetectable level. A patient with baseline HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL decreased from 147 IU/mL to an undetectable level in HBV viral load during anti-PD-1 treatment. However, one patient without antiviral therapy had a baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL and a 9.9-fold increase in HBV DNA levels (from 3950 IU/mL to 39,200 IU/mL) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of HBV DNA during anti-PD-1 treatment in (A) patients with HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL on antiviral therapy and (B) patients with HBV not on antiviral therapy. Of 32 patients with HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL on antiviral therapy, three developed an increase in HBV viral load, but none achieved HBV reactivation. A patient without antiviral therapy and a baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL had a 9.9-fold increase in HBV DNA levels (from 3950 IU/mL to 39,200 IU/mL)

Impact of antiviral therapy on disease progression and survival in patients with advanced HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

Baseline demographics, tumor, liver function and treatment characteristics were well-balanced between antiviral treatment and non-antiviral treatment groups, while ALBI grade differed (P = 0.002) between the two groups (Table 3). The overall survival rates in the two groups differed significantly on the basis of the stratified log-rank test (Fig. 2). The median OS was significantly higher in patients receiving antiviral therapy compared to those not receiving antiviral therapy (20.6 vs 11.1 months, HR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.06–0.78, P = 0.020). Similarly, the median PFS was longer in patients receiving antiviral therapy than in those not (9.8 vs 5.2 months, HR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.20–0.97, P = 0.041). Multiple regression analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard models to identify whether antiviral therapy was an independent predictor of OS and PFS, adjusting for potential confounders. Antiviral status (adjusted HR = 0.24, 95% CI 0.094–0.63, P = 0.004), high serum albumin (adjusted HR = 0.37, 95% CI 0.18–0.75, P = 0.006) and absence of vascular invasion (adjusted HR = 0.29, 95% CI 0.14–0.60, P = 0.001) were independent protective factors for OS in a multivariate analysis of patients with HBV-related HCC (Table 4). However, there was no significant effect of antiviral treatment on PFS (adjusted HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.35–1.23, P = 0.19) (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Subgroup characteristics of patients with or without antiviral therapy

| Variable | Antiviral therapy (n = 197), n (%) | No antiviral therapy (n = 20), n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 54 (28–79) | 51 (28–75) | |

| Age (years) (> 60/ ≤ 60) | 56/141 | 6/14 | 0.88 |

| Gender (female/male) | 25/172 | 2/18 | 1.00 |

| ECOG performance status (0–1/2) | 162/35 | 16/4 | 1.00 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes/no) | 92/105 | 10/10 | 0.78 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein levels, ng/mL (≤ 1210/ > 1210) | 126/71 | 13/7 | 0.93 |

| Albumin, g/L (≤ 35/ > 35) | 43/154 | 6/14 | 0.58 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L (< 34/ ≥ 34) | 174/23 | 20/0 | 0.14 |

| ALT, U/L (≤ 40/ > 40) | 107/90 | 8/12 | 0.22 |

| ALBI grade (1/2/3) | 90/103/4 | 17/3/0 | 0.002 |

| Child–Pugh stage (A/B) | 155/42 | 17/3 | 0.71 |

| BCLC Stage (0-A/B/C) | 35/42/120 | 3/3/14 | 0.71 |

| Liver cirrhosis (yes/no) | 126/71 | 11/9 | 0.43 |

| HBeAg status (seropositive/seronegative) | 19/178 | 1/19 | 0.78 |

| Tumor size, cm (≤ 5/ > 5) | 120/77 | 13/7 | 0.72 |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 39/158 | 4/16 | 1.00 |

| Vascular invasion (yes/no) | 56/141 | 3/17 | 0.20 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis (yes/no) | 73/124 | 10/10 | 0.26 |

| Cycles of PD-1 inhibitor (< 5/ ≥ 5) | 79/118 | 12/8 | 0.086 |

| Treatment baseline (first or second line/above second line) | 125/72 | 12/8 | 0.76 |

| Treatment modality (monotherapy/combination therapy) | 6/191 | 2/18 | 0.34 |

| PD-1 inhibitor type | 0.46 | ||

| Camrelizumab | 136 (69.0) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Toripalimab | 25 (12.7) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Sintilimab | 27 (13.7) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Nivolumab | 5 (2.5) | 0 | |

| Keytruda | 2 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Tislelizumab | 2 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| PD-1 inhibitors combined with targeted drug | 0.59 | ||

| No | 17 (8.6) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Yes | 180 (91.4) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Apatinib | 108 (60.0) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Anlotinib | 14 (7.8) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Lenvatinib | 34 (18.9) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Regorafenib | 4 (2.2) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Sorafenib | 19 (10.6) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Bevacizumab | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| PD-1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy (yes/no) | 5/192 | 1/19 | 1.00 |

| Concomitant local therapy (yes/no) | 101/96 | 7/13 | 0.17 |

| Clinical response | 0.46 | ||

| CR | 10 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PR | 62 (31.5) | 7 (35.0) | |

| SD | 85 (43.1) | 6 (30.0) | |

| PD | 40 (20.3) | 7 (35.0) | |

| ORR | 72 (36.5) | 7 (35.0) | |

| DCR | 157 (79.7) | 13 (65.0) |

Fig. 2.

Comparison of overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) in antiviral-treated and non-antiviral-treated patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hazard ratios for PFS and OS, as well as 95% confidence intervals are shown for patients in the antiviral treatment group compared to the non-antiviral treatment group

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for OS in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma patients

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Group (no antiviral versus antiviral) | 0.025 | 0.36 (0.15–0.88) | 0.004 | 0.24 (0.094–0.63) |

| Age (years) (> 60 versus ≤ 60) | 0.032 | 2.61 (1.09–6.26) | 0.082 | 2.27 (0.90–5.69) |

| Gender (female versus male) | 0.49 | 0.66 (0.20–2.16) | ||

| Alcohol consumption (yes versus no) | 0.22 | 1.52 (0.78–2.97) | ||

| ECOG performance status (0 + 1 versus 2) | 0.00 | 11.36 (4.89–26.37) | 0.00 | 12.35 (5.01–30.43) |

| AFP ng/mL (≥ 1210 versus < 1210) | 0.018 | 0.46 (0.25–0.88) | 0.37 | 0.73 (0.37–1.45) |

| HBeAg status (positive versus negative) | 0.003 | 0.30 (0.14–0.65) | 0.14 | 0.53 (0.23–1.23) |

| ALBI grade (1versus 2 + 3) | 0.058 | 1.88 (0.98–3.60) | ||

| Child–Pugh stage (A versus B) | 0.12 | 1.77 (0.86–3.67) | ||

| BCLC Stage (0 + A versus B + C) | 0.07 | 6.30 (0.86–46.13) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis (yes versus no) | 0.24 | 0.67 (0.34–1.32) | ||

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L (< 34 versus ≥ 34) | 0.58 | 1.31 (0.51–3.37) | ||

| Albumin, g/L (≤ 35 versus > 35) | 0.00 | 0.31 (0.16–0.60) | 0.006 | 0.37 (0.18–0.75) |

| ALT, U/L (≤ 40 versus > 40) | 0.23 | 1.47 (0.78–2.78) | ||

| Vascular invasion (yes versus no) | 0.002 | 0.37 (0.20–0.70) | 0.001 | 0.29 (0.14–0.60) |

| Tumor size, cm (≤ 5 versus > 5) | 0.24 | 0.69 (0.37–1.29) | ||

| Tumor number (Multiple versus Single) | 0.056 | 0.25 (0.06–1.04) | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis (yes versus no) | 0.06 | 0.55 (0.29–1.03) | ||

| Treatment modality (mono versus combined) | 0.84 | 0.89 (0.26–2.97) | ||

Discussion

Treatment options for advanced HCC have evolved rapidly over the past few years. After a decade with sorafenib as the only available treatment for advanced disease, new options are now available to treat patients in various settings (e.g., first and second lines) [10, 11]. Immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, has shown promising results in patients with advanced HCC, possibly in part due to the contribution of inflammation and suppressed immune microenvironments to the pathogenesis of HCC [12, 13]. In this study, we observed a median OS of 20.6 months and median PFS of 9.0 months in patients with HBV-related HCC who had received anti-PD-1 immunotherapy at our center in recent years.

HBV infection is the single most common cause of HCC; up to 400 million individuals worldwide are living with a chronic HBV infection and are at high risk of developing HCC, with the majority of cases found in Asia and Africa [14, 15]. In many HCC clinical trials, high HBV load is a common exclusion criterion for anti-PD-1 therapy and thus the impact of baseline viral load on the clinical outcome has not previously been evaluated. So, what is the relationship between HBV load and survival time in patients with HCC? In this study, we assessed the impact of baseline HBV DNA levels on progression-free and overall survival in HCC patients treated with anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy and found heterogeneity of effect was not seen between high and low baseline HBV DNA levels groups for OS or PFS. In Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, baseline HBV DNA levels ≤ 500 IU/mL were associated with higher OS compared to high baseline viral load (NR vs 18.4 months; P = 0.0097; Supplementary Fig. 3B). However, baseline demographics, tumor, and liver function status varied between groups (Tables 1), creating confounding factors. The multivariate Cox proportional-hazards model demonstrated that baseline HBV DNA levels ≤ 500 IU/mL and baseline HBV DNA levels > 500 IU/mL had similar HR for death (adjusted HR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.29–2.02, P = 0.59).

Viral load in other virus-associated malignancies has been reported to affect the clinical prognosis of anti-PD-1 therapy, as in gastric and anal squamous cell carcinoma [16, 17]. However, a sub-study of the “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Malignancy Consortium 095 study” reported that anti-PD-1 alone had no effect on HIV latency or latent HIV viral reservoir [18]. In addition, research has shown that viral status has little impact on the remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment during HCC tumorigenesis, so viral etiology cannot be considered a selection criterion for HCC patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy [19, 20]; this is consistent with our results.

Negative co-repressor molecules are extensively expressed on functionally exhausted HBV-specific T lymphocytes in individuals with chronic hepatitis B, particularly in the liver, where the majority are PD-1 positive [21]. Blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may help decrease HBV viral load by promoting T regulatory cell proliferation and restoring antiviral T cell function [22]. These studies may indicate a potential role for anti-PD-1 therapy in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Our findings show that patients with baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL did not experience HBV reactivation with concurrent antiviral treatment. Among four patients not receiving antiviral therapy, HBV DNA decreased in one patient with HBV DNA ≤ 500 IU/mL, while two patients maintained an undetectable HBV viral load, and one patient with a baseline HBV DNA > 500 had a 9.9-fold increase in HBV DNA levels. These results underscore the need for antiviral treatment in patients with baseline HBV DNA > 500 IU/mL.

Exhausted HBV-specific T lymphocytes highly express the PD-1 molecule, and blocking the binding of PD-1 to its ligand (PD-L1) shows a promising role in enhancing the function of these T cells [21–23]. However, one study provides some new insights into blocking the PD-1/ PD-L1 pathway for the treatment of non-viral associated HCC [24]. This study points out that CD8+ PD1+ T cells in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) fail to perform effective immune surveillance and instead show potential for tissue damage that contributes to the induction of NASH-HCC. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy increases the abundance of CD8+ PD1+ T cells and enhances the development of HCC. Non-viral liver cancer, particularly NASH-HCC, responds poorly to immunotherapy, while anti-PD-1 immunotherapy improves survival in patients with HBV-associated HCC.

In previous studies, antiviral therapy has been shown to be effective in preventing HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis B, reducing HBV-related HCC recurrence, and improving postoperative survival [25]. The findings of the current large cohort study show that alongside treatment with anti-PD-1, antiviral treatment is associated with reduced risk of mortality, after adjustment for potential confounding factors. A significant (adjusted HR = 0.24, 95% CI 0.094–0.63, P = 0.004) increase in survival was noted in patients receiving antivirals compared with propensity-score-matched untreated patients (Table 4). In addition, there were no significant differences in efficacy (P = 0.60) or adverse events (P = 0.93) among patients receiving antiviral therapy with different PD-1 inhibitors (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Receiving antiviral therapy can partially relieve or delay the deterioration of liver function and improve survival. Antiviral therapy can alter T-cell function, as CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from patients receiving antiviral therapy express higher markers of effector T-cells and lower markers of T-cell depletion. Antiviral drugs activate T cells and enhance their immune function, thereby improving the prognosis and reducing the recurrence rate of HBV-associated HCC [26, 27].

Antiviral therapy can reduce HBx protein expression to levels insufficient to promote HCC development, acting at the genomic level by preventing the integration of HBV DNA into the host chromosome or by affecting its malignant potential [28]. In cases of HBsAg ( +), pre-emptive antiviral therapy should be started as soon as possible before (i.e., most often 7 days) or, at the latest, at the same time as the onset of immunosuppressive therapy with an anti-HBV drug with a high resistance barrier, such as entecavir, TDF, or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and should be continued for the duration of treatment and for at least 6 months after completion of treatment (or for at least 12 months for patients receiving anti-CD20 antibodies and up to 18 months according to EASL) [29].

Potential limitations of our study include the following. Data were obtained retrospectively and may have involved different times of assessment; in addition, only 9.2% of patients did not receive antiviral therapy during the treatment period of anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy and only 76.0% of patients had HBV DNA testing prior to anti-PD-1 treatment. Second, the population was heterogeneous, with the majority of patients receiving combination therapy during anti-PD-1 treatment. Third, all patients in this study received anti-PD-1 blockade and the applicability of our results to other immune checkpoint inhibitors needs to be further explored.

Conclusions

In conclusion, for patients with advanced HBV-related HCC treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, baseline HBV DNA levels are not associated with OS or PFS. PD-1 blockade use was safe even with HBV viral load levels above 500 IU/mL when combined with antiviral therapy as HBV reactivation does not occur. A need exists to expand the use of antiviral therapy in the immunotherapy of HBV- related HCC, as it improves patient survival rates.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants and participating clinicians at each study site. Thanks to Dr. Yuqing Liu for her help in managing patients, and Dr. Jiangong Zhang for assisting in analyzing the data in this paper. Many thanks to Dr. Hongle Li for the overall design of this paper. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81972690) and Medical Science and Technology Research Project of Health Commission of Henan Province (YXKC2021007).

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete response

- DCR

Disease control rate

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HBeAg

Hepatitis B e antigen

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD

Progressive disease

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- SD

Stable disease

Author contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. MA performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. WW and JZ edited the manuscript and were responsible for revisions. BT, LZ, YY, YW, TL, and MZ were responsible for patient management. HH, HC, PQ, XZ, and LH analyzed data. ZW and QG designed and supervised the study. All authors interpreted the data and were involved in the development, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81972690) and Medical Science and Technology Research Project of Health Commission of Henan Province (YXKC2021007). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University & Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, China. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and because no patient specimens were used, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committees.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish has been obtained from all authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mengchao An and Wenkang Wang have been contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Quanli Gao, Email: zlyygql0855@zzu.edu.cn.

Zibing Wang, Email: zlyywzb2118@zzu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JL, Lin XJ, Zhou Q, Shi M, Li SP, Lao XM (2016) Association of HBV DNA replication with antiviral treatment outcomes in the patients with early-stage HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing curative resection. Chin J Cancer 35:28. Published 2016 Mar 18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sohn W, Paik YH, Kim JM, et al. HBV DNA and HBsAg levels as risk predictors of early and late recurrence after curative resection of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(7):2429–2435. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto A, Tanaka E, Rokuhara A, et al. Efficacy of lamivudine for preventing hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: a multicenter retrospective study of 2795 patients. HEPATOL RES. 2005;32:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Wen F, Li J, et al. A high baseline HBV load and antiviral therapy affect the survival of patients with advanced HBV-related HCC treated with sorafenib. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2147–2154. doi: 10.1111/liv.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong CCN, Wong GLH, Wong VWS, et al. Antiviral therapy improves post-hepatectomy survival in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective-retrospective study. Aliment Pharm Ther. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560–1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.29800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):550–558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, et al (2020) NCCN Guidelines insights: management of immunotherapy-related toxicities, version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 18(3):230–241 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(10):599–616. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, et al. Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):2960–2970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O'Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(3):222–232. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):681–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264–1273.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Zhang F, Zhou N, et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(5):e1581547. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1581547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balermpas P, Martin D, Wieland U, et al. Human papilloma virus load and PD-1/PD-L1, CD8+ and FOXP3 in anal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: Rationale for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(3):e1288331. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1288331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmussen TA, Rajdev L, Rhodes A, et al. Impact of Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reservoir in people living with HIV with cancer on antiretroviral therapy: the AIDS malignancy consortium 095 study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1973–e1981. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho WJ, Danilova L, Lim SJ, et al. Viral status, immune microenvironment and immunological response to checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000394. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding Z, Dong Z, Chen Z, et al. Viral status and efficacy of immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:733530. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.733530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertoletti A, Ferrari C. Adaptive immunity in HBV infection. J Hepatol. 2016;64(1 Suppl):S71–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee PC, Chao Y, Chen MH, et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001072. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boni C, Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, et al. Characterization of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific T-cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection. J Virol. 2007;81(8):4215–4225. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfister D, Núñez NG, Pinyol R, et al. NASH limits anti-tumor surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature. 2021;592(7854):450–456. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Wen F, Li J, et al. A high baseline HBV load and antiviral therapy affect the survival of patients with advanced HBV-related HCC treated with sorafenib. LIVER INT. 2015;35:2147–2154. doi: 10.1111/liv.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Chen G, Cai Z, et al. Genomic and transcriptional Profiling of tumor infiltrated CD8+ T cells revealed functional heterogeneity of antitumor immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2018;8(2):e1538436. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1538436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Yan C, Zhu J, et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy employed in treating hepatitis B virus infection-related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a literature review. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1037. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Gao S, Zhao M, et al. Anti-HBV drugs suppress the growth of HBV-related hepatoma cells via down-regulation of hepatitis B virus X protein. CANCER LETT. 2017;392:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziogas DC, Kostantinou F, Cholongitas E, et al. Reconsidering the management of patients with cancer with viral hepatitis in the era of immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000943. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.