Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) through programmed cell death 1 blockade improve the survival outcomes of patients with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Recently, the use of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for the treatment of ESCC has been gradually increasing. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of neoadjuvant treatment of ICIs with chemotherapy and explore tumor microenvironment (TME) immune profiles of ESCC samples during neoadjuvant therapy.

Methods

Patients with previously untreated, resectable, locally advanced ESCC (stage II or III) in Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital were enrolled. Each patient received two to four cycles of neoadjuvant ICIs combined with chemotherapy before surgical resection. The TME immune profiles of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples at baseline and after surgery were evaluated by multiplex staining and multispectral imaging.

Results

In all, 18 patients were enrolled, and all patients received surgery with R0 resection. The postoperative pathological evaluation indicated that 7 (38.9%) patients had a pathological complete response (pCR) and 11 (61.1%) patients had a partial response. The neoadjuvant therapeutic regimens had acceptable side effect profiles. The TME immune profiles at baseline observed higher densities of stroma CD3 + , PD-1 + , and PD-1 + CD3 + cells in pCR patients than in non-pCR patients. Comparing TME immune profiles before and after neoadjuvant treatment, an increase in CD8 + T cells and a decrease in CD163 + CD68 + M2-like macrophage cells were observed after neoadjuvant treatment.

Conclusions

Neoadjuvant ICIs combined with chemotherapy produced a satisfactory treatment response, demonstrating its anti-tumor efficacy in locally advanced ESCC. Further large-scale studies are required to understand the role of tumor immunities and ICIs underlying ESCC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-022-03354-7.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), Neoadjuvant, Immunotherapy, Combination, Tumor microenvironment (TME), Immune

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is a common malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. The predominant subtype of esophageal cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), is more commonly observed in eastern Asia, while another subtype, esophageal adenocarcinoma, occurs more frequently in western countries [1]. The prognosis of esophageal cancer is poor, with the 5-year overall survival (OS) rates ranging from 12 to 20% due to advanced disease stage at diagnosis and tumor heterogeneities at histologic and molecular levels [2, 3]. For locally advanced patients without tumor metastasis, their 5-year OS rates were improved to 20–35% [3]. Surgical resection is usually recommended as the primary treatment option for localized non-cervical ESCC [4]. However, the rate of R0 resection was approximately 50% which indicated that some patients might have early recurrence after surgery [5, 6]. To improve postoperative survival, preoperative chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery was recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) guidelines for patients with locally advanced ESCC. As demonstrated by previous clinical studies, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy provide significant survival benefits and have therefore been routinely adopted [7–9].

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) emerged as effective cancer treatment approaches through blocking the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and other checkpoint molecules such as T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3), lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), either alone or in combination [10, 11]. Higher response rates and durable responses were observed in patients with different cancer types when receiving immunotherapy [11, 12]. Therefore, many ICIs have been approved and recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as the first- or later-line cancer therapies for various cancer types, including ESCC [13]. Compared with chemotherapy, improved survival outcomes were observed in patients with advanced or metastatic EC when using pembrolizumab or camrelizumab in second-line settings [14, 15]. Recently, the use of pembrolizumab with chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for advanced ESCC showed extended OS than chemotherapy alone in the KEYNOTE-590 study [16]. Based on the results of CHECKMATE-577 study, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, as an adjuvant treatment of completely resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer with residual pathologic disease in patients who have received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [17].

As ICIs are only effective in a subset of patients, it remains an unmet clinical need to identify which patients are most likely to respond to and benefit from ICIs. Tumor intrinsic factors, such as PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor mutational burden (TMB), showed associations with the effects of ICIs treatment [18–21]. More recently, many cellular components of the tumor microenvironment (TME), including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), have emerged to be novel biomarkers during ICIs treatment [13]. Recently, there were four different types of TME have been proposed based on the presence or absence of TILs and PD-L1 expression in tumor cells [22].

Tremendous progress has been made with neoadjuvant immunotherapy in the treatment of several locoregionally advanced resectable solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, head and neck cancer, and breast cancer, leading to ongoing phase 3 trials and change in clinical practice [23–26]. Recently, neoadjuvant immunotherapy for the treatment of ESCC has been gradually increasing [27–29]. However, there is still a lack of compelling evidence to support the efficacy of ICIs for ESCC in neoadjuvant settings. Besides, the relationship between tumor immune microenvironment and treatment response of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in ESCC remains elusive. Camrelizumab and sintilimab, two humanized monoclonal antibodies against PD-1, are approved as second-line therapy, and their combination with chemotherapy are proven as first-line therapy for patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC in China but not in western countries. In the present study, we recruited patients with localized ESCC (stage II-III) to evaluate the efficacy of these two ICIs with chemotherapy in neoadjuvant settings and to describe the dynamic TME immune profiles during ICIs treatment. Our preliminary results observed the associations between ICIs treatment response and TME markers which could contribute to further understanding the role of tumor immunities and ICIs underlying ESCC.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

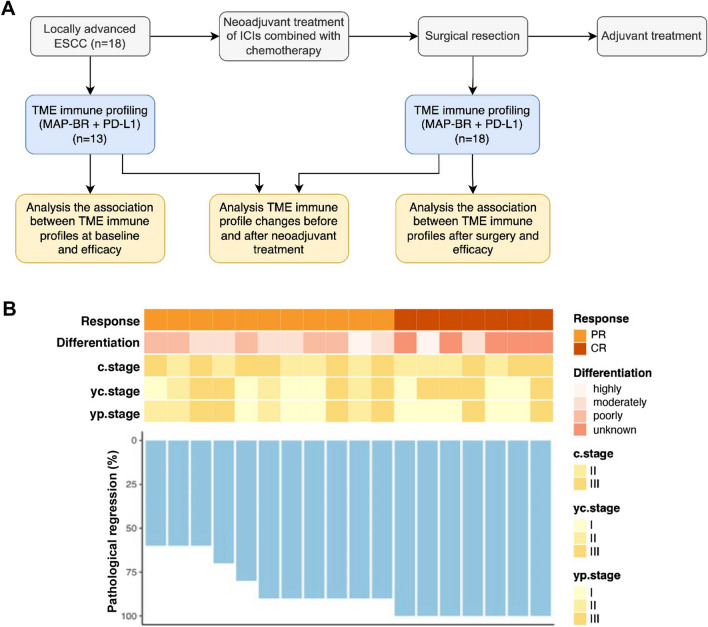

The study design is shown in Fig. 1a. This study recruited 18 patients diagnosed with locally advanced ESCC in Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital between December 2019 and December 2020 from two clinical trials (ChiCTR2000033761 and ChiCTR2100045992). Patient eligibility criteria included the following: (1) resectable locally advanced ESCC (clinical stage IIA-IIIB) confirmed by histology; (2) aged 18–70 years; (3) measurable and evaluable lesions that meet the criteria of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1; (4) no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (5) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0–1; (6) adequate organ function. For the current study, only 18 patients with enough formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples and clinical information were included for the following analysis. FFPE tumor samples at baseline and after surgery from the patients were sent to Burning Rock Biotech (Guangzhou, China) laboratory for TME immune profiling. The MAP-BR panel of 8 markers including CD3, CD8, PD-L1, PD-1, CD68, CD163, CD56, and Pan-CK. The baseline information of the patients, including tumor size, tumor location, TNM stage, tumor differentiation, ECOG status, and PD-L1 expression, were retrospectively collected from a de-identified database. All patients in the study received ICIs in combination with paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy in neoadjuvant settings, followed by surgery. Tumor regression grade (TRG) and treatment response evaluation were performed on each patient.

Fig. 1.

Study design and treatment response. a Study design. b Clinical and pathological response for each patient at baseline and after neoadjuvant treatment. ESCC—esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ICIs—immune checkpoint inhibitors, TME—tumor microenvironment, PR—partial response, CR—complete response

Procedures

All patients in the study received two to four cycles of neoadjuvant treatment before surgical resection without extra notification, with each treatment cycle of 21 days. On day 1, patients were administered camrelizumab (200 mg) or sintilimab (200 mg) with nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) (260 mg/m2) and nedaplatin (80 mg/m2). At baseline and after every two neoadjuvant treatment cycles, enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, and upper abdomen and/or positron emission tomography-CT and ultrasound endoscopy was performed. Tumor response was assessed by two senior radiologists after two cycles of neoadjuvant treatment and before surgery according to RECIST version 1.1. This primer for eighth edition staging of esophageal cancers separates classifications for the clinical (cTNM), pathologic (pTNM), post-neoadjuvant clinical response stage (ycTNM), and post-neoadjuvant pathologic (ypTNM) stage groups.

After the first day of the final treatment cycle, surgery was scheduled within 21–42 days. According to the standard procedures for minimally invasive esophagectomy, the primary tumor and lymph nodes were resected [30]. After surgical resection, the percentage of residual tumor cells was measured in accordance with previously reported methods to evaluate pathological response [31–34]. The pathological responses of each patient were confirmed by two pathologists. American Joint Committee of Cancer and College of American Pathologists (AJCC/CAP) TRG four-category system was used to evaluate the pathologic response to neoadjuvant treatment, TRG 0, no residual cancer cells; TRG 1, single cells or small groups of cancer cells; TRG 2, residual cancer cells outgrown by fibrosis; and TRG 3, minimum or no treatment effect. The pathological complete response (pCR) was defined as the absence of viable tumor cells in the resected cancer sample. Adverse events (AEs) and abnormal laboratory results were assessed according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 5.0.

TME analysis

PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) was assessed using a commercially available PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay (clone 22C3, Dako) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Multiplex staining and multispectral imaging were performed to identify the cell subsets in the TME. Multiplex immunofluorescence staining was obtained using the PANO 7-plex IHC kit, cat 0,004,100,100 (Panovue, Beijing, China). Two microenvironment analysis panels with different primary antibodies were used for this study, including PD-L1 antibody (clone E1L3N, CST13684, CST), PD-1 antibody (clone EH33, CST43248, CST), CD3 antibody (clone SP7, Ab16669, Abcam), CD8 antibody (clone C8/144B, CST70306, CST), and Pan-CK antibody (clone C11, CST4545, CST) for one panel, and CD68 antibody (clone BP6036, BX50031, Biolynx), CD163 antibody (clone D6U1J, CST93498, CST), CD56 antibody (clone 123C3, CST3576, CST), and Pan-CK antibody (clone C11, CST4545, CST) for another panel. Next, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody incubation and tyramide signal (TSA) amplification were sequentially performed. The slides were microwave heat-treated after each TSA operation. Nuclei were stained with 4’-6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, SIGMA-ALDRICH) after all the human antigens had been labeled. To obtain multispectral images, the stained slides were scanned using the Mantra System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, US).

Image analysis

Images of unstained and single-stained sections were used to extract the spectrum of autofluorescence of tissues and each fluorescein, respectively. The extracted images were further used to establish a spectral library required for multispectral unmixing by inForm image analysis software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, US). Using this spectral library, we obtained reconstructed images of sections with autofluorescence removed. Our study reported the density and positive rate of PD-1 + , PD-L1 + , CD3 + (T cells), CD8 + (cytotoxic T cells), CD56 + (NK cells), CD3 + PD-1 + (exhausted T cells), CD8 + PD-1 + (exhausted cytotoxic T cells), CD163-CD68 + (M1 phenotype macrophage), and CD163 + CD68 + (M2-like macrophage) staining on lymphocytes in both tumor and stromal compartments.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were presented as mean or median. The categorical variables were presented as frequencies. Wilcoxon rank-sum test for unpaired samples and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples were used to compare continuous variables, while the two-sided Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All bioinformatics analyses were performed with R (v.3.5.3, the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline information of patients

The study recruited 18 male patients with locally advanced ECCC (Table 1). The mean age was 61.06 ± 6.11 years, and the median age was 60.5 years. The ECOG performance status was 0 for 10 patients and 1 for 8 patients, respectively. The tumors were highly differentiated in 2 patients (level 1, 11.1%), moderately differentiated in 6 patients (level 2, 33.3%), and poorly differentiated in 5 patients (level 3, 27.8%). The status of tumor differentiation remained undefined in 5 patients (level 4, 27.8%). There were 7 patients (38.9%) with tumors located in the middle segment and 11 patients (61.1%) with tumor locations in the lower segment. The c.stage evaluated at baseline were 9 patients at stage II (50%) and 9 patients at stage III (50%). The mean and median tumor lengths were 6.5 cm and 7 cm, respectively. At baseline, patients with pCR and non-pCR showed a significant difference in tumor differentiation (p = 0.006), while no significant differences were observed in age, ECOG, tumor location, c.stage, and tumor length (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in this study

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 18) | Paired* (n = 13) | non-pCR (n = 11) | pCR (n = 7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.977 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.06 (6.11) | 61.23 (6.04) | 61.09 (6.56) | 61.00 (5.83) | |

| Median [IQR] | 60.50 [57.00, 64.25] | 60.00 [57.00, 62.00] | 61.00 [58.00, 65.50] | 60.00 [57.00, 62.00] | |

| ECOG PS | 0.705 | ||||

| 0 | 10 (55.6) | 8 (61.5) | 7 (63.6) | 3 (42.9) | |

| 1 | 8 (44.4) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Differentiation | 0.006 | ||||

| Highly | 2 (11.1) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Moderately | 6 (33.3) | 5 (38.5) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Poorly | 5 (27.8) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 5 (27.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Tumor location | 1.000 | ||||

| Middle segment | 7 (38.9) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (36.4) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Lower segment | 11 (61.1) | 10 (76.9) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Tumor length | 0.693 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.50 (1.76) | 7.07 (1.38) | 6.64 (1.29) | 6.29 (2.43) | |

| Median [IQR] | 7.00 [5.00, 7.75] | 7.00 [7.00, 8.00] | 7.00 [5.50, 7.00] | 7.00 [5.00, 8.00] | |

| cT.stage | 0.387 | ||||

| T1 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | |

| T2 | 13 (72.2) | 9 (69.2) | 8 (72.7) | 5 (71.4) | |

| T3 | 4 (22.2) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (14.3) | |

| cN.stage | 0.177 | ||||

| N1 | 10 (55.6) | 7 (53.8) | 8 (72.7) | 2 (28.6) | |

| N2 | 8 (44.4) | 6 (46.2) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (71.4) | |

| c.stage | 0.334 | ||||

| II | 9 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (28.6) | |

| III | 9 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) | 4 (36.4) | 5 (71.4) | |

| PD-L1, CPS | 0.557 | ||||

| < 10 | 5 (27.8) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (14.3) | |

| > = 10 | 8 (44.4) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (57.1) | |

| unknown | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (28.6) |

*Patients with paired samples pre- and post-neoadjuvant treatment

pCR—pathological complete response, SD—standard deviation, IQR—interquartile range, PS—performance score, cT.stage—clinical T stage, CPS—combined positive score

Patient responses to neoadjuvant treatments

All patients in the study received ICIs in combination with paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy in neoadjuvant settings (Fig. 1a). As shown in Fig. 1b and Table S1, the yc.stage evaluated after neoadjuvant treatment indicated that there were 7 patients at stage I (38.9%), 3 patients at stage II (16.7%), and 8 patients at stage III (44.4%). There were 8 (44.4%) patients who achieved downstaging after neoadjuvant treatment. All patients received surgery, and R0 resection was achieved in all cases. After surgery, evaluation of yp.stage observed 8 patients at stage I (44.4%), 4 patients at stage II (22.2%), and 6 patients at stage III (33.3%). All patients in the study responded to neoadjuvant treatment, including 11 patients who achieved PR (61.1%) and 7 patients who achieved complete response (CR) (38.9%), according to RECIST v1.1. All patients with CR achieved TRG grade 0 (n = 7), which we called pCR patients; while there were 6 patients with PR who achieved TRG grade 1 and 5 patients with PR who achieved TRG grade 2, and we called these 11 patients non-pCR patients. The mean and median rates of pathologic regression were 87.22 ± 14.87% and 90%, respectively. Patients with CR showed significantly higher rates of pathologic regression than PR patients (p = 0.0003).

As illustrated in Table 1 and Table S1, significant differences were observed in tumor differentiation (p = 0.006), TRG (p < 0.001), ycT.stage (p = 0.030), and ypT.stage (p = 0.031) between non-pCR and pCR patients. During neoadjuvant treatment, severe adverse events of grade ≥ 3 were observed, including leukopenia (n = 4, 22%), decreased neutrophil count (n = 2, 11%), and lymphopenia (n = 8, 44%) (Supplement Table S1). Other adverse events of any grades mainly included leukopenia (n = 12, 67%), lymphopenia (n = 12, 67%), nausea (n = 12, 67%), anemia (n = 11, 61%), and alopecia (n = 11, 61%) (Supplement Table S2).

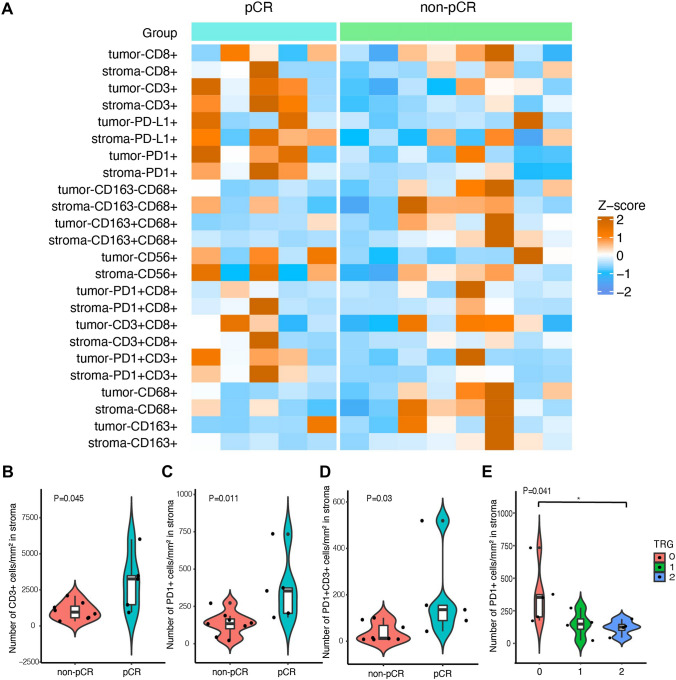

TME immune profiles at baseline

There were 13 patients with paired tissue samples before and after neoadjuvant treatment and 5 patients with tissue samples after neoadjuvant treatment only. Therefore, a total of 18 samples obtained after neoadjuvant treatment and 13 samples obtained before neoadjuvant treatment were selected for TME immune profiling. Figure 2a shows the overview of TME immune profiles in all baseline samples. At baseline, densities and positive rates of immune cells were compared between patients with pCR and non-pCR. As for cell densities, we observed that stroma CD3 + (p = 0.045), PD-1 + (p = 0.011) and CD3 + PD-1 + (p = 0.030) cells showed higher densities in pCR than non-pCR patients (Fig. 2b–d). We also found a positive correlation between higher stroma PD-1 density and higher TRG levels (Fig. 2e). When focusing on positive cell rates, although stroma CD3 + cells seem higher in pCR patients while stroma and tumor CD68 + and CD68 + CD163- cells in tumor and stroma seem higher in non-pCR patients, no statistically significant differences were observed (Figure S1A). We then analyzed the association of PD-L1 expression with treatment efficacy and found that PD-L1 CPS had a positive correlation trend with TRG levels and response, although the difference did not reach a significant level (Figure S1B-D).

Fig. 2.

The association of the density of TME immune markers with treatment response. a Heatmap shows the density of immune cells in tumor and stromal area at baseline in all patients. Z-score was used to normalize a marker across samples. b–d Violin plot shows the density distribution of stroma CD3 + cells (b), PD-1 + cells (c), and PD-1 + CD3 +(d) cells in non-pCR and pCR patients. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for statistical analysis. e Association of the density of stroma PD-1 + cells with TRG. Kruskal–Wallis test was used for statistical analysis. TME—tumor microenvironment, pCR—pathological complete response, TRG—tumor regression grading

In addition, many TME immune markers showed associations with different disease stages. Higher densities and positive rates of CD68 + , CD163-CD68 + , CD163 + CD68 + in the tumor and stroma area, densities and positive rates of CD8 + , CD3 + CD8 + in the stroma area, and density of CD163 + in the tumor area were observed in c.stage II than c.stage III (p < 0.05) (Supplement Figure S2).

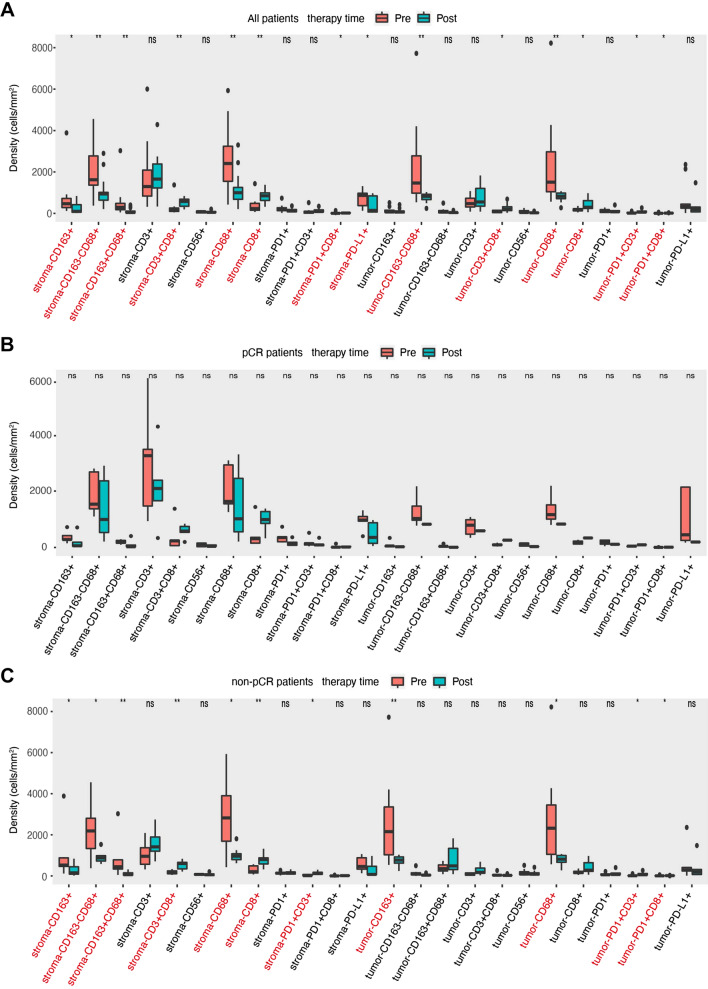

TME profiles after neoadjuvant treatment

After neoadjuvant treatment, no statistically significant differences in positive rates and densities were observed between pCR and non-pCR patient groups (Supplement Figure S3A and S3B). Numbers of TME immune markers, including densities of tumor PD-L1 + (p = 0.028), CD68 + CD163 − (p = 0.011), CD68 + (p = 0.011) and positive rates of tumor PD-L1 + (p = 0.028), stroma CD163 + CD68 + (p = 0.027), CD163 + (p = 0.039) were varied between different TRG grades (Supplement Figure S4). There were 13 patients including 5 pCR and 8 non-pCR, who had paired FFPE samples before and after neoadjuvant treatment. We then compared the changes in TME immune profiles during neoadjuvant treatment in these 13 patients. For all paired patients, we found that the varied changes in TME immune profiles were featured by a significant increase in T lymphocytes and a decrease in macrophages. As shown in Fig. 3a, the densities of stroma CD163 + , CD163-CD68 + , CD163 + CD68 + , CD68 + , PDL1 + and tumor CD163-CD68 + , CD68 + cells were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, positive rates of stroma CD3 + CD8 + , CD8 + , PD-1 + CD8 + and tumor CD3 + CD8 + , CD8 + , PD-1 + CD3 + , PD-1 + CD8 + cells were significantly increased (p < 0.05). The same immune profile changes were observed in positive rates of immune cells during neoadjuvant treatment (Figure S5A). In pCR patients, no significant changes in TME immune profiles were observed (Fig. 3b and Figure S5B), which may be affected by the limited sample size. In non-pCR patients, compared with baseline samples, similar results of a significant increase in T lymphocytes and a decrease in macrophages were observed after neoadjuvant treatment (Fig. 3c and Figure S5C).

Fig. 3.

The changes of the density of TME immune markers in paired samples between pre- and post-neoadjuvant treatment in all 13 patients (a), pCR patients (b), and non-pCR patients (c). *indicates P < 0.05; ** indicates P < 0.01; ns, —not significant. TME—tumor microenvironment, pCR—pathological complete response

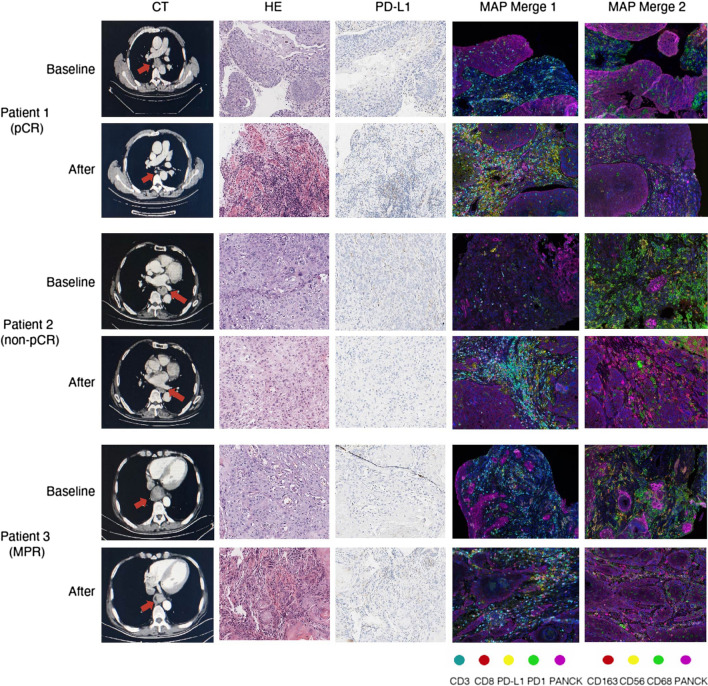

Representative cases of TME immune profiles

To visualize the changes in TME immune profiles before and after neoadjuvant treatment, we selected three representative cases and showed their computed tomography (CT), hematoxylin and eosin (HE), PD-L1, and TME immune profiles at baseline and after surgery in Fig. 4. Patient 1 was a 73-year-old male with a stage II ESCC before neoadjuvant treatment. CT results showed significant shrinkage for the primary tumor and achieved downstaging after neoadjuvant treatment. This patient achieved pathological regression of 100% for an esophageal lesion with no residual lymph node metastasis according to the postoperative specimen. Patient 2 was a 60-year-old male, who had a stage III ESCC before neoadjuvant treatment. The primary tumor had significant shrinkage after preoperative treatment. However, staging after neoadjuvant treatment was still stage III. This patient had 60% pathological regression of the primary tumor but had 8 residual metastatic lymph nodes. Patient 3 was a 65-year-old male, who had a stage II ESCC before neoadjuvant treatment. The primary tumor had partial shrinkage after preoperative treatment, and staging after neoadjuvant treatment was still stage II. This patient had 90% pathological regression of the primary tumor and have no residual metastatic lymph nodes. We found that the infiltration level of CD8 + T cells increased, while the infiltration level of M2-like macrophages (CD68 + CD163 +) decreased after neoadjuvant treatment in all these patients.

Fig. 4.

Representative case series of one pCR patient and two non-pCR patients with the results of CT, HE, PD-L1 IHC staining, and multiplex immunofluorescence imaging of TME immune markers at baseline and after neoadjuvant treatment, respectively. The locations of the lesions were marked with red arrows. × 400 magnification for HE and PD-L1 IHC images, and × 200 magnification for MAP images. CT—computed tomography, HE—hematoxylin, and eosin, IHC—immunohistochemistry, MAP—microenvironment analysis panel, pCR—pathological complete response, MPR—major pathologic regression

Discussion

Although the evidence of ICIs treatment benefits in combination with chemotherapy is strong in advanced ESCC [16, 35], the evidence of immunotherapy is limited in the neoadjuvant setting. In our study, we reported short-term results of neoadjuvant ICIs combined with paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy in 18 patients with stage II-III ESCC. All patients underwent surgery, and R0 resection was achieved in all cases. Of note, 38.9% of surgical patients achieved pCR. Recently, many centers in the field of ESCC in China have also successively reported several clinical results of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for locally advanced ESCC patients. The TD-NICE study used 3 cycles of neoadjuvant treatment with tislelizumab, carboplatin, and nab-paclitaxel in treatment-naïve patients with resectable ESCC [36]. Major pathologic response (MPR) and pCR rates in 36 surgical patients were 72.0% and 50.0%, respectively. The NICE study used 2 cycles of camrelizumab plus nab-paclitaxel and carboplatin to treat patients with locally advanced but resectable thoracic ESCC, staged as T1b-4a, N2-3 (≥ 3 stations), and M0 or M1 lymph node metastasis [28]. pCR rate in 51 surgical patients was 39.2%. Based on the results of NICE study, the investigators designed NICE-2 study, a three-arm clinical trial, comparing camrelizumab plus chemotherapy (IO-CT) and camrelizumab plus CRT (IO-CRT) versus CRT as preoperative treatment for locally advanced ESCC [37]. This is the first prospective randomized controlled trial to explore commonly used neoadjuvant treatments in clinical practice, which will provide high-level evidence of neoadjuvant treatment for patients with locally advanced ESCC. There are no interim results released yet, and we expect positive results in future. KEEP-G03 trial evaluated the feasibility and safety of preoperative sintilimab (anti-PD-1) in combination with triplet chemotherapy of lipo-paclitaxel, cisplatin, and S-1 for resectable ESCC [38]. pCR and MPR rates in 15 surgical patients were 26.7% and 53.3%, respectively. PALACE-1 study used preoperative pembrolizumab with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (PPCT) to treat resectable ESCC patients [39]. Of note, pCR rate in 18 surgical patients was 55.6%, surpassing the results of classic CROSS and NEOCRTEC5010. Besides, KEYSTONE-001 study used preoperative pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel, cisplatin to treat locally advanced ESCC patients [40]. The interim analysis results showed that the pCR and MPR rates in 29 surgical patients were 41.4% and 72.4%, respectively. Relatively high response rates to ICIs with chemotherapy in neoadjuvant settings were consistently observed in our study and other published studies, demonstrating the efficacy of ICIs with chemotherapy in neoadjuvant settings for locally advanced ESCC patients.

To further investigate varied patient responses to ICIs-based neoadjuvant treatment, our study performed TME immune profiling in each patient before neoadjuvant treatment and after surgical resection. The TME immune profiles at baseline observed higher densities of stroma CD3 + T cells, PD-1 + and PD-1 + CD3 + exhausted T cells in pCR patients. Significant associations between the density of stroma PD-1 + and TRG were also observed. After surgical resection, no significant differences in TME immune profiles were observed between pCR and non-pCR patients. Furthermore, we compared TME immune profiles before neoadjuvant treatment and after surgical resection. We found that many TME immune markers in tumor and stroma were changed significantly, including the decrease in CD163 + , CD68 + , CD163 + CD68 + macrophage cells and the increase in CD3 + , CD8 + T cells.

The changes in TME immune profiles were also reported in other studies. After neoadjuvant treatments with ICIs and chemotherapy in ESCC patients, a study observed an increase in CD4 + in the pCR group, and an increase in CD8 + , CD163 + , and PD-L1 + in the non-pCR group [29]. The priming of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells were involved in the signaling of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and contributed to efficient and durable anti-tumor immunities [41, 42]. CD163 has been known as a specific biomarker of M2-like macrophages, which promote immuno-suppression with increased expression of PD-L1 [43–45]. The CD8 + cells are associated with signals to cytotoxic T lymphocytes and further contribute to efficient and durable anti-tumor immunity [46]. In our study, neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade might enhance the systemic priming of anti-tumor T cells in the microenvironment of ESCC. As our study observed varied changes in CD68 + CD163 + cells, it was suggested that induction of M2-like macrophages with increased expression of PD-L1 may be associated with ineffective immunotherapy.

The combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy is corroborated to have a synergistic anti-tumor effect due to the immunomodulatory effects of chemotherapy, such as the release of antigens, upregulation of maturation of dendritic cells and antigen presentation, depletion of immune suppressive cells, and direct stimulation of T cells [47]. Neoadjuvant ICIs treatment has the potential to enhance the systemic T cell response to tumor antigens, resulting in enhanced detection and killing of micrometastatic tumor deposits disseminated beyond the resected tumor [48]. PD-L1 expression is enriched in ESCC, which may increase the susceptibility of these patients to eliminate tumors after ICIs treatment. The reported prevalence of PD-L1 expression in ESCC ranges from 15 to 83% in tumor cells, and from 13 to 31% in immune cells [49–51]. In our cohort, the ratio of PD-L1 CPS > = 10 is 38.5% (5/13), and the ratio of PD-L1 CPS > = 1 is 61.5% (8/13). Our TME immune data showed that tumor-infiltrating CD8 + T cells were enriched in the samples we analyzed. According to the definition of four TME types based on the presence/absence of TILs and PD-L1 expression in tumor cells [22], type I (PD-L1 + /TILs +) and type IV (PD-L1-/TILs +) may be the two most common TME types in ESCC based on our expression data. In summary, our data show that ESCC is probably an immune hot tumor, which may partly explain why neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy can achieve such an impressive response rate in our study.

Some limitations in our study should be noted as well. First, the sample size of 18 patients is relatively small compared with other phase III clinical trials. The effects of ICIs neoadjuvant treatment and its associations with TME might be influenced by potential confounders, therefore, should be further validated. Second, all patients in our study received ICIs with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment. There is a lack of a control group due to the single-arm design. It is unfeasible to directly compare treatment performance between ICIs with chemotherapy and chemotherapy alone. Third, regular follow-ups are needed to examine if neoadjuvant ICIs could provide long-term survival benefits for localized ESCC. Fourth, the patients were all male in our cohort, and no treatment results were reported for female patients. Fifth, no ICIs have been approved for neoadjuvant therapy for ESCC. Patients included in the current study were from our previous clinical trials. Future studies of larger sample sizes, including female patients, are to be carried out. Finally, the multiplex immunofluorescence staining only allows us to detect limited cell subtypes in the TME, including T cells, cytotoxic T cells, NK cells, M1phenotype macrophage, and M2-like macrophage. Due to dramatic advances in high-throughput technologies, 28 immune cell subsets could be calculated based on mRNA expression profiles of tumor samples and appropriate machining learning methods thus far [52]. In further studies, high-throughput platforms, such as whole transcriptome sequencing, should be utilized to dissect the effects of ICIs on T cell maturation/differentiation of the particular stage, cytotoxic T cells activation, as well as APCs and CD4 + T cells.

In conclusion, our study used ICIs with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatments for localized ESCC. All patients showed treatment responses, including 7 patients who achieved pCR and 11 patients who achieved PR. Many TME immune markers varied between pCR and non-pCR patients before neoadjuvant and changed significantly in PR patients during neoadjuvant treatment. Further large-scale clinical studies are required to understand the role of tumor immunities and ICIs underlying ESCC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number [82172786]). TME immune profiling was performed at Burning Rock Biotech (Guangzhou, China). Camrelizumab was provided by Hengrui, and sintilimab was provided by Innovent. We owe thanks to patients and their families. We would also like to thank Lihong Wu, Bing Li, Xiaona Han, and Jinying Liu from Burning Rock Biotech for their assistance and suggestions in data interpretation and manuscript writing.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse events.

- CPS

Combined positive score.

- CR

Complete response.

- CT

Computed tomography.

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4.

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

- ESMO

European Society for Medical Oncology.

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration.

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded.

- HE

Hematoxylin and eosin.

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors.

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry.

- LAG-3

Lymphocyte activation gene-3.

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

- MPR

Major pathologic response.

- MSI

Microsatellite instability.

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

- NCI-CTCAE

National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

- OS

Overall survival.

- pCR

Pathological complete response.

- PD-1

Programmed cell death 1.

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand 1.

- PR

Partial response.

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophages.

- TILs

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

- TMB

Tumor mutational burden.

- TME

Tumor microenvironment.

- TRG

Tumor regression grade.

- TSA

Tyramide signal

Author Contributions

XW, XL, and CW contributed equally to this work. JZ and JM designed and supervised the study. XW, XL, and CW participated in the idea of the article. YY, HJ, YX, LZ, HL, CF, and DZ acquired samples and collected clinical data. XW, XL, and CW performed the bioinformatic analysis and statistical analysis. XW and XL wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number [82172786]).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Fig. 4.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (Reference number: 2020-50-IIT and 2021-49-IIT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoyuan Wang, Xiaodong Ling and Changhong Wang have contributed equally to this work and shared the first authorship. Jinhong Zhu and Jianqun Ma have contributed equally to this work and shared the corresponding authorship.

Contributor Information

Jinhong Zhu, Email: zhujinhong@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Jianqun Ma, Email: jianqunma@hrbmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Napier KJ, Scheerer M, Misra S. Esophageal cancer: A review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:112–120. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i5.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly RJ. Emerging multimodality approaches to treat localized esophageal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1009–1014. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leng XF, Daiko H, Han YT, Mao YS. Optimal preoperative neoadjuvant therapy for resectable locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1482:213–224. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medical Research Council Oesophageal Cancer Working G (2002) Surgical resection with or without preoperative chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 359: 1727-33.10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08651-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2499–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1314530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eyck BM, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof M, et al. Ten-year outcome of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for esophageal cancer: the randomized controlled CROSS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1995–2004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, et al. Long-term efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for the treatment of locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the NEOCRTEC5010 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:721–729. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boussiotis VA. Molecular and biochemical aspects of the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1767–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardhan K, Anagnostou T, Boussiotis VA. The PD1:PD-L1/2 pathway from discovery to clinical implementation. Front Immunol. 2016;7:550. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baba Y, Nomoto D, Okadome K, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Baba H. Tumor immune microenvironment and immune checkpoint inhibitors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:3132–3141. doi: 10.1111/cas.14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima T, Shah MA, Muro K, et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-181 study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4138–4148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, Xu J, Chen Y, et al. Camrelizumab versus investigator's choice of chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCORT): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:832–842. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2021;398:759–771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1191–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, Patel SP, Frampton GM, Miller V, Stephens PJ, Daniels GA, Kurzrock R. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2598–2608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:847–856. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis AA, Patel VG. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker: an analysis of all US food and drug administration (FDA) approvals of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:278. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0768-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying cancers based on T-cell infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2139–2145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1976–1986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF, et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:1655–1661. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenfeld JD, Hanna GJ, Jo VY, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in untreated oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: a phase 2 open-label randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1563–1570. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:810–821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xing W, Zhao L, Zheng Y, et al. The sequence of chemotherapy and toripalimab might influence the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer-a phase II study. Front Immunol. 2021;12:772450. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.772450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Yang Y, Liu Z, et al. Multicenter, single-arm, phase II trial of camrelizumab and chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W, Xing X, Yeung SJ, et al. Neoadjuvant programmed cell death 1 blockade combined with chemotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson SJ, Batirel HF, Bueno R, Jaklitsch MT, Lukanich JM, Allred E, Mentzer SJ, Sugarbaker DJ (2001) Transthoracic esophagectomy with radical mediastinal and abdominal lymph node dissection and cervical esophagogastrostomy for esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 72: 1918–24; discussion 24–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03203-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hellmann MD, Chaft JE, William WN, Jr, et al. Pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancers: proposal for the use of major pathological response as a surrogate endpoint. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e42–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandard AM, Dalibard F, Mandard JC, et al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clin Correl Cancer. 1994;73:2680–2686. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2680::aid-cncr2820731105>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker K, Mueller JD, Schulmacher C, Ott K, Fink U, Busch R, Bottcher K, Siewert JR, Hofler H. Histomorphology and grading of regression in gastric carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98:1521–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein JE, Lipson EJ, Cottrell TR, et al. Pan-tumor pathologic scoring of response to PD-(L)1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:545–551. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, et al. Effect of camrelizumab vs placebo added to chemotherapy on survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the ESCORT-1st randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:916–925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan X, Duan H, Ni Y, et al. Tislelizumab combined with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for surgically resectable esophageal cancer: a prospective, single-arm, phase II study (TD-NICE) Int J Surg. 2022;103:106680. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Zhu L, Cheng Y, et al. Three-arm phase II trial comparing camrelizumab plus chemotherapy versus camrelizumab plus chemoradiation versus chemoradiation as preoperative treatment for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NICE-2 Study) BMC Cancer. 2022;22:506. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09573-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu Y, Chen X, Wang D, et al. A study of neoadjuvant sintilimab combined with triplet chemotherapy of lipo-paclitaxel, cisplatin, and S-1 for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S1307–S1308. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Zhao S, Zheng Y, et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE-1) Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shang X, Zhang C, Zhao G, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin as a neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced resectable (stage III) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (Keystone-001): interim analysis of a prospective, single-arm, single-center. Phase II trial Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S1428–S1429. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borst J, Ahrends T, Babala N, Melief CJM, Kastenmuller W. CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:635–647. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freud AG, Mundy-Bosse BL, Yu J, Caligiuri MA. The broad spectrum of human natural killer cell diversity. Immunity. 2017;47:820–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019;30:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su S, Zhao J, Xing Y, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition overcomes ADCP-induced immunosuppression by macrophages. Cell. 2018;175:442–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen ZF, Liu H, Gao R, et al. Tumor cell-released autophagosomes (TRAPs) promote immunosuppression through induction of M2-like macrophages with increased expression of PD-L1. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:151. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laidlaw BJ, Craft JE, Kaech SM. The multifaceted role of CD4(+) T cells in CD8(+) T cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:102–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinhuis KM, Ros W, Kok M, Steeghs N, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Enhancing antitumor response by combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:219–235. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Pardoll DM. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.aax0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salem ME, Puccini A, Xiu J, et al. Comparative molecular analyses of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2018;23:1319–1327. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang Y, Lo AWI, Wong A, Chen W, Wang Y, Lin L, Xu J. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and PD-L1 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:30175–30189. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo W, Wang P, Li N, Shao F, Zhang H, Yang Z, Li R, Gao Y, He J. Prognostic value of PD-L1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9:13920–13933. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charoentong P, Finotello F, Angelova M, Mayer C, Efremova M, Rieder D, Hackl H, Trajanoski Z. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 2017;18:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.