Abstract

Neurosurgeons receive extensive technical training, which equips them with the knowledge and skills to specialise in various fields and manage the massive amounts of information and decision-making required throughout the various stages of neurosurgery, including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care and recovery. Over the past few years, artificial intelligence (AI) has become more useful in neurosurgery. AI has the potential to improve patient outcomes by augmenting the capabilities of neurosurgeons and ultimately improving diagnostic and prognostic outcomes as well as decision-making during surgical procedures. By incorporating AI into both interventional and non-interventional therapies, neurosurgeons may provide the best care for their patients. AI, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) have made significant progress in the field of neurosurgery. These cutting-edge methods have enhanced patient outcomes, reduced complications, and improved surgical planning.

Keywords: Neurosurgery, Artificial intelligence, Machine learning, Deep learning, Virtual reality

1. Introduction

Neurosurgery is a demanding profession with extensive training, many years of tuition, and a combination of highly developed cognitive, decision-making, and surgical abilities. Neurosurgeons commonly work alongside neuroanesthetists, neuroradiologists, neurologists, neurological specialist nurses, and even medical students in multidisciplinary teams. The necessary skill set comprises empathy, the capacity to work long shifts, and adequate psychomotor skills. As with any form of medicine, neurosurgical interventions are not guaranteed to result in positive outcomes. For example, technical faults account for one-fourth of all errors in neurosurgery which may lead to worse patient outcomes.1 However, prudent integration and utilisation of artificial intelligence (AI) can grant significant opportunities to address these mistakes more rapidly to the benefit of the patient.

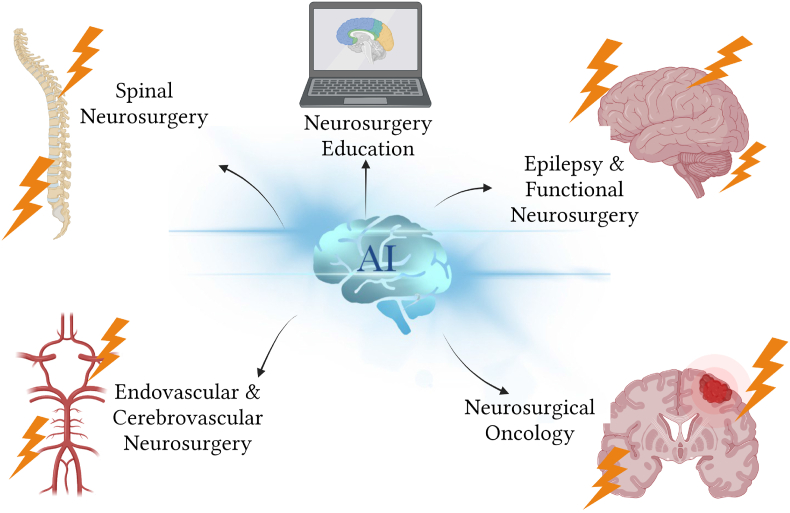

AI has rapidly advanced both inside and outside of the medical sector over the past decade, and it has certainly transformed most neurosurgical subspecialties (Fig. 1). Machine learning (ML), a subfield of AI, is concerned with using data to create self-teaching and self-improving algorithms. Deep learning (DL), a subset of ML, uses artificial neural networks (ANNs) to automatically extract, analyse, and grasp pertinent information from raw data. Surgery, such as the further complex discipline of neurosurgery, carries a considerable risk of morbidity and mortality. To revolutionise neurosurgery, however, combining AI, ML, and DL has the potential to improve clinical treatment diagnostic and prognostic outcomes, assist neurosurgeons in making decisions during surgical interventions, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Artificial intelligence (AI) application in various neurosurgical fields (created with Biorender.com).

Further, augmented prognostic ability may not necessarily precipitate modification in clinical and neurosurgical care, or even increased patient survival. Although, by giving recommendations to foster consensus among neurosurgeons on surgical approaches, AI may lower variability in patient outcomes while also improving prognostication and cutting expenditure. This contributes to the global improvement of safe, equitable, and high-quality neurosurgical care. Current conventional methods may not effectively address some challenging preoperative and postoperative neurosurgical issues, which highlights the potential benefits of AI integration to improve patient outcomes. The primary preoperative concerns include precise prediction of surgical risks and benefits, strategic planning of surgical approaches, and identification of suitable surgical candidates.2,3 In contrast, the main postoperative issues encompass averting and managing common complications such as infection, bleeding, stroke, pain, early mobilisation and rehabilitation, and monitoring neurological status and recovery.3, 4, 5 The literature suggests that AI can contribute to various aspects of neurosurgery, including diagnosis, clinical decision-making, surgical procedures, prognosis, data collection, education and research.2,3 AI utilisation may augment the accuracy, efficiency, safety, and quality of care provided to neurosurgical patients, leading to improved outcomes.2,3

However, as the use of these technologies in neurosurgery increases, new challenges arise, including data quality, algorithm bias, regulatory issues, and ethical considerations. To better understand the potential benefits and limitations of AI, ML, and DL in neurosurgery, this literature review ought to examine recent outcomes and challenges, identify areas of progress and limitations, and discuss ethical and regulatory considerations. This comprehensive review aims to guide future research in this rapidly evolving field.

2. Application and outcomes of AI, ML and DL in various neurosurgery specialties

2.1. Spinal neurosurgery

2.1.1. Accurate detection of spinal cord compressions and lesions

DL models have been shown to accurately detect compressions and lesions in the spinal cord using radiological images. Merali et al (2021) conducted a large prospective study employing cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data and identified spinal cord compressions with a DL model with an accuracy of 94%, 88% sensitivity, 89% specificity and 82% precision and recall in the classification task (Table 1).6 Halliman et al (2022) also used DL models to classify low-grade or high-grade metastatic epidural spinal cord compression (MESCC) using the Bilsky grading scale.7 The output of the DL models has shown excellent results with a 92%–98% agreement by the radiologists for the Bilsky classification.7 Thus, a dependable DL model with a high degree of specificity was recognized, with a value of 93.6 being identified (Table 1).7 Hence, this shows the significant importance of DL models in diagnosing, classifying spinal cord diseases, identifying the proper team for referrals and planning a proper management to achieve better outcomes for the patients (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics and clinical outcomes of artificial intelligence models in neurosurgery diagnosis and treatment.

| Author, Year, Country | Specialty | AI Model Types Used In the Study | Evaluation Metrics and Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merali et al, 2021, Canada6 | Spinal Neurosurgery | DL (CNN) | Cervical Spinal Cord Compression Detection: Accuracy: 94% Sensitivity: 88% Specificity: 89% |

| Hallinan et al, 2022, Singapore7 | Spinal Neurosurgery | DL (CNN) | Spinal Metastases Detection: Internal test sets: Sensitivity: 97.6% Specificity: 93.6% External test sets: Sensitivity: 89.9% Specificity: 98.1% |

| Doerr et al, 2022, United States8 | Spinal Neurosurgery | DL (CNN) | Injury Classification Accuracy: 86.8% |

| Kim et al, 2020, Republic of South Korea9 | Spinal Neurosurgery | ML (Random forest, XGBoost, Bayesian generalized linear model, decision-making tree model, k-cluster analysis, logistic regression analysis and neural network analysis) | Operation time Accuracy: 97.5% Reoperation occurrence Accuracy: 95.2% |

| Hopkins et al, 2020, United States10 | Spinal Neurosurgery | ML (DNN) | Prediction of Postoperative SSI Accuracy: 78.7% |

| De la Garza Ramos et al, 2022, United States11 | Spinal Neurosurgery | ML (ANN) | Prediction of Perioperative Blood Transfusion: Accuracy: 77% Sensitivity: 80% |

| Azimi et al, 2014, Iran12 | Spinal Neurosurgery | ML (ANN) | Surgical satisfaction Accuracy: 96.9% |

| Elahian et al, 2017, United States13 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | ML (Logistic regression) | Abnormal SOZ identification Accuracy: 83% |

| Roy et al, 2020, United Kingdom14 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | ML (k-NN, SGD, XGBoost, and CNN) | Seizure-wise cross validation Accuracy: 90.1% Patient-wise cross validation Accuracy: 56.1% |

| Saputro et al, 2019, Indonesia15 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | ML (SVM) | Classification of Seizure Type: Accuracy: 91.4% Sensitivity: 90.25% Specificity: 97.83% |

| Ahmedt et al, 2018, Australia16 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | DL (CNN, Long short-term memory) | Multi-fold cross-validation Accuracy: 92.10% Leave-one-subject-out cross-validation Accuracy: 58.49% |

| Varatharajah et al, 2022, United States17 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | ML (Naïve Bayes classifier) | Prediction of Seizure Occurrence 1 year Post-op: Dataset 1 Accuracy: 78% Dataset 2 Accuracy: 76% |

| Kassahun et al, 2014, Germany18 | Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery | ML (Genetic -based data mining, ontology-based classification) | Epilepsy Classification Accuracy: 60% |

| Shi Z et al, 2020, China19 | Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery | ML (CNN) | Aneurysm detection/Lesion level: Accuracy: 88.6% Sensitivity: 94.4% Specificity: 83.9% |

| Faron et al, 2020, Germany20 | Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery | ML (CNN) | 1st diagnosis sensitivity: 95% 2nd diagnosis sensitivity: 94% |

| Park et al, 2019, United States21 | Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery | DL (DNN) | Threshold of Aneurysm Size for Intraprocedural Rupture Accuracy: 68.7% Sensitivity:60% Specificity: 79.1% |

| Nishi et al, 2021, Japan22 | Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery | DL (CNN) | Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Detection: Patient based analysis: sensitivity: 99% Specificity: 92% Slice based analysis: Sensitivity: 89% Specificity: 98% |

| Cepeda et al, 2021, Spain23 | Neurosurgical Oncology | DL (Inception V3, Cox regression) | B-mode Accuracy: 72–89% Elastography Accuracy: 79–95% |

| Tandel et al, 2020, India24 | Neurosurgical Oncology | DL (CNN) and ML (CNN) | Classification between normal and abnormal (tumorous) Accuracy: DL: 94.7% ML: 73.1% |

| Patil et al, 2023, India25 | Neurosurgical Oncology | DL (Ensemble deep-CNN) | Classification of early stage brain tumor Accuracy: 97.77% |

| Alnowami et al, 2022, Saudi Arabia26 | Neurosurgical Oncology | DL (DenseNet) | Ten-fold cross-validation; Accuracy: 96.52% Sensitivity: 98.5% Specificity: 82.1% |

| Khan et al, 2021, United Kingdom27 | Neurosurgical Oncology | ML (DNN) | Surgical phase accuracy: 91% Surgical Steps accuracy: 76% |

| Park, Y.W. et al, 2021, South Korea28 | Neurosurgical Oncology | ML (Radiomics) | Differentiating GBM recurrence from Radiation Necrosis RN post-concurrent chemoradiotherapy: Accuracy: 78% Sensitivity: 66.7% Specificity: 87% |

AI, artificial intelligence; DL, deep learning; ML, machine learning; CNN, convolutional neural network; XG, extreme gradient; DNN, deep neural network; ANN, artificial neural network; SGD, stochastic gradient descent; SVM, support vector machines; DenseNet, densely connected convolutional network; SSI, surgical site infection; SOZ, seizure onset zone; GBM, glioblastoma multiformes.

2.1.2. Precise and sensitive vertebral fracture diagnosis

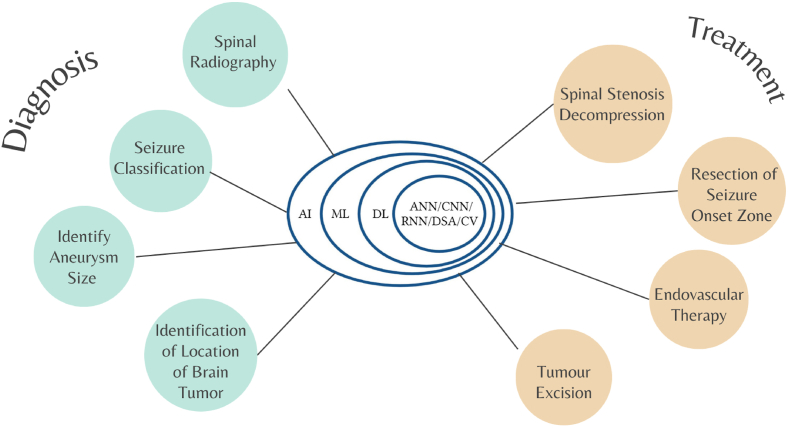

DL models can be utilised to produce precise and sensitive vertebral fracture diagnoses on simple spinal radiography (Fig. 2).29 In a retrospective examination, the computed tomography (CT) scans of 111 individuals with thoracolumbar spinal injuries were merged into a DL model, which was able to classify non-injured and suspected injury with an accuracy of 86.8% (Table 1).8

Fig. 2.

Algorithms/Models of Artificial Intelligence for Neurosurgery Diagnostics and Treatment Approach. AI, artificial intelligence; DL, deep learning; ML, machine learning; CNN, convolutional neural network; ANN, artificial neural network; CV, computer vision; DSA, digital signature algorithm (Created With Biorender.com).

2.1.3. Predicting surgical outcomes in spinal cord procedures

DL may be applied to evaluate how a spinal procedure would subsequently impact a spinal condition or associated damage. Liu and Kong (2021) used the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) DL approach to analyse data from 27 patients who had undergone posterior cervical vertebral canal decompression angioplasty.30 An ML model was also developed to predict the outcomes of lumbar spinal stenosis decompression surgery for patients (Fig. 2). The accuracy of the model was highest when it accurately predicted changes in mental state.31

2.1.4. Clinical decision-making and clinical outcome prediction in spinal surgery

ML models can support clinical decision-making and clinical outcome prediction in spinal surgery. In a study conducted in Korea, a prognostic prediction was produced for 111 individuals who had spinal stenosis (Table 1).9 An ML model also had a 92.56% positive predictive value for post-operative surgical site infections following posterior spinal infusions (Table 1).10 Another ML model that was trained to predict the frequency of blood transfusions post-adult spinal deformity surgery produced encouraging results (Table 1).11 Azimi et al (2014) compared the accuracy of an ANN model to a traditional predictive model that used logistic regression and showed that the accuracy rate of the ANN model was 96.9%, whereas the logistic regression model's accuracy rate for patients was 80% (Table 1).12

2.2. Epilepsy and functional neurosurgery

2.2.1. ML-based seizure categorization

ML methods have been developed to categorise seizure types with high accuracy using scalp electroencephalography (EEG) recordings labelled with seizure categories (Table 1).14, 15, 16, 18, 32 These models have utilised various techniques including CNNs, support vector machine (SVM), and k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) (Fig. 1).14, 15, 16, 18, 32 Studies have shown F1 scores of 97.4% and 97.2% for accurately identifying seizure types in two datasets with 8 and 4 distinct seizure classes, respectively.32

2.2.2. ML-based epilepsy subtype classification

ML models have been developed to classify epilepsy subtypes based on patient symptom data that is text-based (Fig. 2). Kassahun et al (2014) proposed ontology-based and genetics-based algorithms to classify temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and extra-temporal lobe epilepsy with a 60% accuracy rating (Table 1).18 Based on clinical data, these algorithms may be able to identify illness characteristics and assist in determining the optimal course of treatment for patients.

2.2.3. ML-based seizure onset zone localization

Recent research has elucidated that ML-based technology may be used to locate the seizure onset zone (SOZ) in patients with epilepsy (Fig. 2). Elahian et al (2017) developed a model using patient intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) recordings to categorise each electrode position into SOZ and non-SOZ (Table 1).13 They trained the algorithm using signal characteristics found at the corresponding electrodes of the two classes, specifically the phase locking values (PLVs) between the phase of lower frequency rhythms and the amplitude of high gamma activity. The model has shown to accurately predict SOZ and non-SOZ electrodes in patients with seizure-free outcomes. Also, they have demonstrated a link between surgical outcomes and the percentage of non-resected SOZ electrodes.

2.2.4. ML-based EEG analysis for epilepsy diagnosis

ML-based systems have been developed to quantitatively evaluate EEG data for epilepsy diagnosis. Varatharajah (2022) developed an ML-based system to examine the EEG data of 41 patients with TLE pre-operatively.17 The study observed changes in spectral power and coherence parameters of a typical EEG between TLE patients who achieved symptom freedom one-year post-anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) and those who continued to experience post-surgical seizures. Patients who had postoperative seizures exhibited a reduction in spectral power and coherence in the 10–25 Hz frequency region. The authors postulate that this variation is due to networks that generate temporal lobe seizures either inside or outside of the ATL borders.

2.3. Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery

2.3.1. Overview

Endovascular and Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery refer to surgical procedures performed in the brain and blood vessels of the central nervous system (CNS). The application of AI has brought a revolutionary change in the diagnosis and treatment of life-threatening conditions such as stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), burst aneurysms, and large vessel occlusion (LVO) (Fig. 1).

2.3.2. Diagnosis and classification of neurological disorders

One of the significant advantages of AI is its ability to analyse vast datasets quickly and accurately. AI can assist in diagnosing complex neurological disorders such as LVO, ICH, and cerebral aneurysms using ML and DL algorithms. For instance, Morey et al (2021) used the Viz LVO algorithm in a real-world experiment on ischemic stroke patients.33 The study showed that the algorithm led to quicker reperfusion, quicker door-to-neurovascular team notification times, and improved clinical results.33 Similarly, DL algorithms were found to be more efficient than radiologists in detecting intracranial aneurysms (IAs) (Table 1).20 These findings suggest that AI can improve the accuracy and speed of diagnosis, which is essential in time-sensitive medical conditions such as stroke.

2.3.3. Surgical planning and decision making

AI can also aid in surgical planning and decision making, especially in complicated procedures such as endovascular treatment. Studies have shown that ML risk prediction is more accurate in predicting aneurysm rupture than traditional methods.34 However, there is minimal research on using ML to predict periprocedural complications related to endovascular treatment (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, recent studies have shown the potential of ML in predicting neurological deficits post-microsurgery.35 Moreover, AI-powered semi-autonomous systems, such as Aneurysm Occlusion Assistant (AnOA), have been developed to anticipate surgical outcomes immediately after the device installation and enable therapeutic adjustment (Table 1).21 These advancements in AI can significantly improve surgical planning and decision-making in complex cases.

2.3.4. Distal aneurysms and intraoperative imaging

Distal aneurysms pose a significant challenge in endovascular treatment due to their small size, anatomical variations, and high risk of postoperative complications. AI can assist in accurately identifying distal aneurysms and predicting their size (Fig. 2). For example, Shi et al (2020) developed a 3-dimensional (3D) CNN segmentation model, DAResUNET, which demonstrated 100% accuracy for aneurysms larger than 5 mm and a sensitivity of 98.6% for aneurysms ≤3 mm (Table 1).19 Furthermore, intraoperative imaging is crucial in identifying and treating complications during surgery. Studies have shown that DL has an excellent success rate in identifying aneurysms and predicting their size using CT angiograms and noncontrast CT (Table 1).36,22 Intraoperative angiography using indocyanine green video angiography (ICG VA) has been found to be effective in identifying the remains of an aneurysm's postoperative neck and improving the success rate of extracranial and intracranial (EC-IC) bypass surgery.37

2.4. Neurosurgical oncology

2.4.1. Introduction to AI in neurosurgical oncology

In recent years, the use of AI has significantly impacted the field of neurosurgical oncology. AI algorithms, ANNs, have been applied to patient data to predict one-year survival rates in patients with brain metastases.38 These models have demonstrated better performance than traditional prediction techniques, indicating their potential to improve treatment outcomes. AI has also made it possible to evaluate each case individually and strike a balance between the benefits of resection and the danger of neurological impairment (Fig. 1).39 Furthermore, AI has the potential to aid in complex surgical decision-making processes and make image analysis more rapid.36,40

2.4.2. AI-assisted surgical planning and decision-making

The use of AI in surgical planning and decision-making has the potential to greatly improve outcomes and reduce neurological sequelae from surgery. Dundar et al (2022) suggested using a surgical route planning algorithm based on heuristics in combination with Q-learning, a form of reinforcement learning-based AI, to determine the optimal points of entry into the skull and the most advantageous routes for minimally invasive tumour removal.41 Additionally, computer vision (CV) has been used to aid in challenging procedures such as transsphenoidal pituitary resection, removal of malignant tumours, and skull-base surgeries. A cutting-edge ML model was developed to accurately discriminate the numerous steps and techniques of the endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenoma excision (Fig. 2), and was able to accurately identify the different steps and surgical phases with high accuracy even with high variability in the training data (Table 1).27

2.4.3. AI in glioma disease prediction and grading

AI has been extensively studied for its potential to improve glioma disease prediction and grading. Marcus et al (2020) found that an ANN model outperformed the conventional grading system in forecasting the surgical resectability of glioblastoma multiformes (GBM).42 Similarly, Moradmand et al (2021) found that a DL-based survival model outperformed other models in predicting surgical outcomes.43 Logistic regression classifiers have also been utilised to forecast glioma grade, achieving high accuracy rates, sensitivity rates, and negative predictive values.44 Furthermore, ANN trained on 2-dimensional (2D) T1-weighted MRI images have been used to accurately separate low-grade gliomas (LGGs) from high-grade gliomas (HGGs).45 The SVM has also been utilised to forecast glioma grading by relying on resting-state functional MRI images, achieving impressive accuracy rates46

2.4.4. AI improving neurosurgical oncology diagnoses and tumour classification

In recent studies, AI has highlighted great potential in improving the diagnosis and classification of brain tumours. Cepeda et al conducted a retrospective study on intraoperative ultrasound with DL models, showing an accuracy of 79–95% for elastography and 72–89% (Table 1) for B-mode in differentiating glioblastomas and solitary brain metastases (Fig. 2).23 Tandel and Patil conducted studies on transfer-learning-based AI systems and CNN respectively, achieving significant results in multi-class brain tumour grading with accuracy rates of 94.7% and 97.77% respectively (Table 1).24,25 Alnowami et al also showed promising results in brain tumour classification using MRI, achieving an accuracy rate of 96.25%, sensitivity rate of 98.5% and specificity rate of 82.1% (Table 1).26 These studies demonstrate that AI can potentially improve patient outcomes by providing quick diagnosis and accurate tumour classification in neurosurgical oncology.

Morell et al, also utilised Quicktome, an ML-based software to assess the effects of intra-axial brain tumours on large-scale brain networks.47 Their study was able to gain a better knowledge of how various brain regions are interconnected and interact by utilising the Quicktome platform. Also, the platform allowed them to spot previously undiscovered patterns or connections between various brain regions.47

2.4.5. AI utilisation in oncological radio-neurosurgery

Radiosurgery uses high-energy beams to target tumours in the brain and nervous system, but accurate detection and segmentation of lesions can be challenging for human practitioners.48 AI/ML/DL techniques can help in radiosurgery for neuro-oncology by automating tumour detection and segmentation, analysing quantitative features from medical images, and designing personalised treatment plans.48,49

Automated detection and segmentation of brain tumours using deep neural networks (DNNs) can reduce inter-practitioner variability and increase efficiency and accuracy.48 It can also save time in tumour contouring for radiation planning,48 improve accuracy and consistency in tumour diagnosis and classification,50 and monitor treatment response and detect tumour recurrence or progression.50 Examples include using U-Net and DenseNet models to detect and segment brain metastases and gliomas.50,51 Radiomics is the extraction and analysis of quantitative features from medical images using AI/ML/DL techniques.52 It can improve diagnosis and classification of brain tumours, predict treatment response and survival outcomes, and provide insights into tumour biology and molecular subtypes.52, 53, 54 Examples include predicting local control and overall survival post-radiosurgery for brain metastases and correlating radiomic features with genomic alterations in gliomas.28, 55, 56

Personalised treatment planning and optimization uses AI/ML/DL models to design and deliver customised radiation therapy regimens based on individual characteristics such as tumour type, location, size, shape, genomic profile, etc.57 It may improve accuracy and consistency in target delineation and dose prescription for brain tumours, predict treatment response and survival outcomes, and design chemo-radiation therapy regimens.48,58 Detecting and segmenting brain metastases, predicting overall survival for GBM patients, and designing CRT regimens for GBM patients based on their genomic profile comprise a few examples.48,58

3. AI reshaping neurosurgery education and training

The application of AI, ML, and DL could significantly advance neurosurgery. These enhancements may be accommodated in two ways: through training and sensible implementation. Examples of models that have been utilised to reduce hand tremors perioperatively have been administered. Hand tremors perioperatively have been observed to increase the risk of complications both during and postoperatively, as well as collateral damage.59 Many AI models have been incorporated into surgical education under the pretence of virtual reality (VR) and 3D simulators to provide sufficient, skill-oriented training for resident and mid-career surgeons to increase their confidence and reduce hand tremors perioperatively (Fig. 1).60 This kind of integration may also be conducted in the classroom by developing a curriculum. A series of evidence-based trainings are recommended as a structural approach to curriculum, according to one Sridhar's study. The training may be performed in stages, beginning with fundamental robotic abilities in a laboratory setting and progressing to individualised assistance utilising a variety of techniques, including simulators, before training in the operating room.60

The application of VR simulations has provided trainees with an immersive and interactive learning experience that may help individuals develop the necessary skills and confidence to perform real-life surgeries. For example, in a study conducted by Sugiyama and colleagues, it was found that VR sessions were highly effective in improving the understanding of patient-specific anatomy among neurosurgeons in 83.3% of cases.61 Moreover, the study also found that VR sessions also aided in the decision-making process for minor surgical techniques in 61.1% of cases and even helped neurosurgeons make critical surgical decisions for cases involving complex and challenging anatomy.61 AI-powered VR simulations offer a safe and controlled environment for trainees to practise surgical procedures. Interestingly, Sugiyama et al's., trainees rated the utility of the VR system significantly higher than experts. A study by Zoli et al (2022) also found that out of 152 young neurosurgeons surveyed, only 31.6% received adequate dedicated AI training. The majority of respondents (92.1%) believed that operative devices were useful, and 89.5% expressed a strong desire to acquire technological neurosurgical skills.62

Reshaping training using AI, ML, and VR is paramount when expanding the scope of neurosurgical education. Despite technological advances being encumbersome financially and inaccessible to low-to middle-economic countries, educators must employ an open approach when implementing AI-powered VR simulations for appropriate training purposes.

4. Challenges and potential risks of AI application in neurosurgery

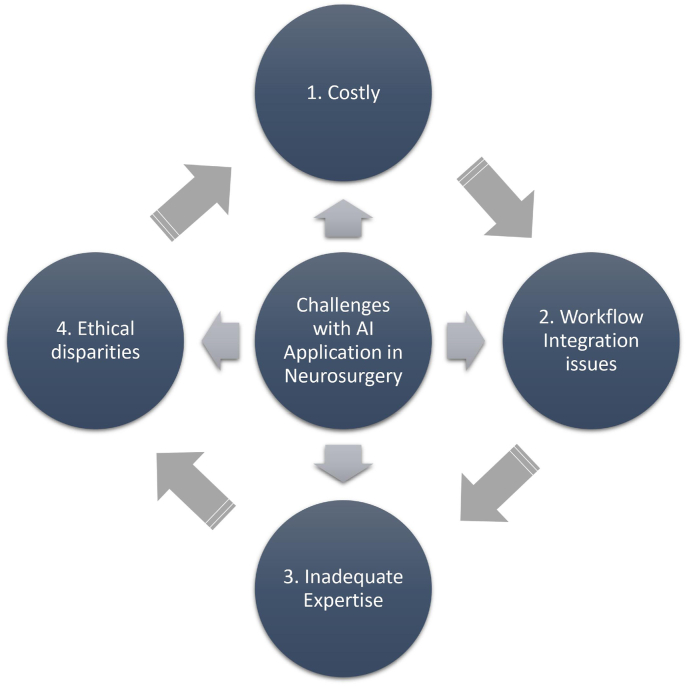

Some obstacles one may face when utilising AI models comprise the type and quality of the datasets that are accessible, the cost, workflow integration, and expertise (Fig. 3). In neurosurgery, pre-, intra-, and postoperative algorithms for personalised medicine have not yet been fully integrated into one model using AI, ML, and DL.2

Fig. 3.

Challenges with artificial intelligence integration in neurosurgery.

Having patients interpret and comprehend ML, DL, and their associated models in terms of management and predictions is another challenge. ML and DL should not be followed blindly since error and uncertainty may occur even if AI has demonstrated satisfactory values in prediction accuracy.63,64As these models rely on categorical and numerical data as inputs and are unable to react to inherent unplanned occurrences during diagnosis and treatment in neurosurgery, AI is still constrained by how uncertainty may be addressed. Repeating a scan to produce a duplicate diagnostic image is an example of one of the aforementioned random occurrences.65

Moreover, the development of an improved AI-enhanced, semi-automated robotic operating system is a potent illustration of numerous challenging stumbling blocks in the creation of the infrastructure's hardware and software. Clearly, a broader integration of AI will require major financial and human resource investment, with the source of funding being another potential barrier.36 The benefits of applying AI must be scrupulously compared to its expenditure. Despite claims to the contrary, there have not been any economic studies concerning the cost reduction of brain tumour surgery following the introduction of AI applications.66 Thus, cost-effectiveness must be appreciated and explored while developing novel, innovative AI systems.

Furthermore, the integration of AI in neurosurgery poses several potential risks. One significant concern is the cybersecurity vulnerabilities that arise as AI systems become more connected to networks and databases. These systems, if not properly secured, may become attractive targets for cyberattacks. A breach of AI systems used in neurosurgery could lead to unauthorised access, data manipulation, or disruptions in surgical procedures.67 Additionally, a greater dependence on AI systems might result in a decline in the clinical expertise and decision-making ability of surgeons. Without a thorough examination, relying too heavily on AI recommendations might precipitate missed diagnoses or futile treatment strategies.67,68

Moreover, flawed, insufficiently taught, or poorly comprehended algorithms may introduce technical errors.68,69 Any malfunction in the AI model could lead to adverse outcomes for the patient, including surgical complications or injuries.69 This may have a long-lasting, large-scale impact on patients' quality of life.68

The probability of systematic bias in AI prediction models is another noteworthy potential concern. Due to a dearth of historical information concerning treatment placement in earlier years, populations in disadvantaged geographic locations who lack access to medical prescriptions may have underdiagnosed conditions.70 Patients who either neglected to disclose or refused to furnish the information compound the risk of systematic bias.70

Overcoming the challenges and careful consideration of AI's potential risks enables the utilisation of the full potential of AI, reshaping the delivery of neurosurgical care and ultimately engendering favourable patient outcomes.

5. Ethical considerations

While the integration of AI has the potential to transform neurosurgical care, ethical concerns need to be carefully considered (Fig. 3).

The possible rise in health inequities is concerning when employing ML models. Patients who either failed to disclose or refused to provide information, alongside a lack of diagnoses in underserved and underprescribed populations, increase the probability of systematic bias.70 As such, addressing this risk is important to bridge the gap in health services in different geographical locations and minimise ethical concerns.

Another ethical concern is data privacy. Vast quantities of patient or case-specific data are necessary to build AI models.71 As such, it is imperative to safeguard data privacy to ensure confidentiality. However, the current solution to address privacy concerns poses a new challenge. When collating and populating text from patient logs concerning discharge or triage notes provided by doctors, it may contain repetitions of similar comments regarding a patient.71This makes it arduous to distinguish between duplicates and might result in erroneous interpretations. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a thorough framework that protects data privacy without sacrificing its quality.

Transparency within AI neurosurgical implementation remains clouded, and an objective to offer legislators and policymakers assistance when addressing morally cumbersome situations mandating AI within healthcare environments is warranted.72 The limitations of algorithmic transparency have affected most legal concerns circumventing AI, where such employment in increasingly high-risk cases precipitates more responsibilities concerning the programme's design, governance, and egalitarianism.72 Accessibility and comprehension of information are its two most important foundations, where AI systems are not at the precipice of modern standards of healthcare.

To ensure the appropriate and ethical incorporation of AI in neurosurgery, it is crucial to address the ethical concerns that arise, such as the potential increase in health inequities, data privacy, transparency, and erroneous interpretations.

6. Future directions

Innovations are very important in today's technological age. Since AI in healthcare has advanced considerably in recent years, it is possible that neurosurgeons and the innovations of robotic application will ultimately work in conjunction with the limits of healthcare systems globally for the betterment of patient care. Moreover, ML has the potential to improve neurosurgical decision-making by shedding light on radiological interpretation, surgical outcomes, and complication prediction, as well as patients' quality of life and surgical satisfaction. It suggests that a sizable majority of neurosurgeons have implemented ML into their clinical practises in some capacity. The equitable distribution of ML users in neurosurgery is proof that ML algorithms may be applied even in resource-constrained settings.

However, the administrative efforts of AI might come as a detriment, where a personalised holistic approach to neurosurgical care should be of paramount importance as opposed to system-based AI-dominated management. Neurosurgeons often offer AI as a helping hand rather than a means of replacing the management employed by humans. Heavy reliance on machine-based systems impedes medical professionals, especially neurosurgeons, from acquiring the required surgical skills. In order for AI to function at its greatest capacity, a large number of therapeutically beneficial algorithms must be installed. While it is arguable whether or not to record patient data, moral and legal issues must be addressed in the event of AI-based misdiagnoses. Suggestions for AI-based solutions being vetted and authorised for patient safety are crucial.

Clinicians from various specialties may increase the precision and usefulness of these technologies in their particular surgical specialties by exchanging knowledge and skills. For instance, DL models have been used in ophthalmology to identify diabetic retinopathy.73 ML algorithms have been utilised in orthopaedics to predict surgical outcomes in patients with joint replacement surgery.74 Moreover, AI and ML are based on cardiothoracic surgery to anticipate postoperative problems and enhance outcomes for patients with heart failure.75,76 Neurology is also an area where AI, ML, and DL are being applied to assist in diagnosis and treatment planning for conditions such as stroke and Parkinson's disease.77,78 The potential of AI, ML, and DL in surgery must be fully realised through collaboration and knowledge exchange. Together, surgeons from different specialties may increase the precision and application of AI, ML, and DL, improving patient outcomes beyond neurosurgery.

Furthermore, in order to comprehend and utilise the data and AI systems more effectively, clinicians would need computer science training. Additionally, VR and AI-powered neurosurgical simulators may efficiently and accurately assess the performance of residents and medical students alike. Patient safety may be increased by using AI-assisted coaching systems to support trainees during challenging surgical procedures. Integrating the knowledge and expertise of experienced clinicians into AI algorithms is a promising approach to improving the accuracy of clinical diagnosis. AI has already demonstrated accuracy in clinical diagnosis comparable to that of experienced clinicians. By programming AI with the input of these experienced clinicians, junior doctors may benefit from valuable guidance that will aid in improving their clinical skills.

In the midst of the excitement surrounding the promising benefits of AI applications in neurosurgery, it is critical to note that there is a critical gap in economic studies pertaining to the alleged cost reduction of brain tumour surgeries.66 Despite claims to the contrary, the lack of such studies gives us an incomplete understanding of the economic impact of AI on this critical aspect of healthcare. More research in this area is required to realise AI's full potential and ensure its seamless integration into the field of neurosurgery.

Instead of replacing human abilities, the idea is to apply AI as a tool to assist healthcare professionals and act as conduits for continuing professional development. Neurosurgeons and AI may continue to enhance the discipline and improve patient care through active collaboration.

7. Conclusion

Neurosurgery may be introduced to the wonders of AI, ML, and DL, where improving diagnostic and prognostic results is a future possibility. The application of such innovations may assist with decision-making perioperatively, ultimately improving patient outcomes for the betterment of their care. Studies have demonstrated high accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and precision in several fields of neurosurgery. However, unprecedented issues must be solved prior to the application of AI in neurosurgical disciplines. Cost expenditure, workflow integration, AI expertise, and restrictions on the types and standards of freely accessible datasets are such issues warranting consideration. Despite said challenges, utilising AI in neurosurgery has the potential to improve clinical outcomes, reduce postoperative complications, and decrease costs, making it a desirable option for healthcare systems globally.

Registration unique identification number

Not Applicable.

Data statement

No data available for sharing.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wireko Andrew Awuah: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Favour Tope Adebusoye: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jack Wellington: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Lian David: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Abdus Salam: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Amanda Leong Weng Yee: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Edouard Lansiaux: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rohan Yarlagadda: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Tulika Garg: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Toufik Abdul-Rahman: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jacob Kalmanovich: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Goshen David Miteu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mrinmoy Kundu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Nikitina Iryna Mykolaivna: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

Wireko Andrew Awuah, Email: andyvans36@yahoo.com.

Favour Tope Adebusoye, Email: Favouradebusoye@gmail.com, F.adebusoye@student.sumdu.edu.ua.

Jack Wellington, Email: Wellingtonj1@cardiff.ac.uk.

Lian David, Email: l.david@uea.ac.uk.

Abdus Salam, Email: salam.elum@gmail.com.

Amanda Leong Weng Yee, Email: amandaleong0120@gmail.com.

Edouard Lansiaux, Email: Edouard.lansiaux.etu@univ-lille.fr.

Rohan Yarlagadda, Email: rohanyarla@gmail.com.

Tulika Garg, Email: tulika0611@gmail.com.

Toufik Abdul-Rahman, Email: Drakelin24@gmail.com.

Jacob Kalmanovich, Email: kalmanovich.jacob1@gmail.com.

Goshen David Miteu, Email: goshendavids@gmail.com.

Mrinmoy Kundu, Email: Kundumrinmoy184@gmail.com.

Nikitina Iryna Mykolaivna, Email: i.nikitina@med.sumdu.edu.ua.

References

- 1.Rolston J.D., Zygourakis C.C., Han S.J., Lau C.Y., Berger M.S., Parsa A.T. Medical errors in neurosurgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(10):S435. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.142777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mofatteh M. Neurosurgery and artificial intelligence. AIMS neuroscience. 2021;8(4):477. doi: 10.3934/Neuroscience.2021025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonsanto M.M., Tronnier V.M. Artificial intelligence in neurosurgery. Chirurg. 2020;91:229–234. doi: 10.1007/s00104-020-01131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose G., Luoma A.M. Postoperative care of neurosurgical patients: general principles. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2017;18(6):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.mpaic.2017.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarwal A. Neurologic complications in the postoperative neurosurgery patient. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2021;27(5):1382–1404. doi: 10.1212/con.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merali Z., Wang J.Z., Badhiwala J.H., Witiw C.D., Wilson J.R., Fehlings M.G. A deep learning model for detection of cervical spinal cord compression in MRI scans. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89848-3. 1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallinan J.T., Zhu L., Zhang W., et al. Deep learning model for classifying metastatic epidural spinal cord compression on MRI. Front Oncol. 2022:1479. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.849447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doerr S.A., Weber-Levine C., Hersh A.M., et al. Automated prediction of the Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity Score from CT using a novel deep learning algorithm. Neurosurg Focus. 2022;52(4):E5. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76866-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K.R., Kim H.S., Park J.E., Kang S.Y., Lim S.Y., Jang I.T. Development of a machine-learning model of short-term prognostic prediction for spinal stenosis surgery in Korean patients. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):764. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10110764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins B.S., Mazmudar A., Driscoll C., et al. Using artificial intelligence (AI) to predict postoperative surgical site infection: a retrospective cohort of 4046 posterior spinal fusions. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;192 doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De la Garza Ramos R., Hamad M.K., Ryvlin J., et al. An artificial neural network model for the prediction of perioperative blood transfusion in adult spinal deformity surgery. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4436. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azimi P., Benzel E.C., Shahzadi S., Azhari S., Mohammadi H.R. Use of artificial neural networks to predict surgical satisfaction in patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(3):300–305. doi: 10.3171/2013.12.spine13674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elahian B., Yeasin M., Mudigoudar B., Wheless J.W., Babajani-Feremi A. Identifying seizure onset zone from electrocorticographic recordings: a machine learning approach based on phase locking value. Seizure. 2017;51:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy S., Asif U., Tang J., Harrer S. Seizure type classification using EEG signals and machine learning: setting a benchmark. IEEE Signal Processing in Medicine and Biology Symposium (SPMB) 2020;5:1–6. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1902.01012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saputro I.R., Maryati N.D., Solihati S.R., Wijayanto I., Hadiyoso S., Patmasari R. Seizure type classification on EEG signal using support vector machine. InJournal of Physics: Conference Series. 2019;120(1) doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1201/1/012065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmedt-Aristizabal D., Nguyen K., Denman S., Sridharan S., Dionisio S., Fookes C. Deep motion analysis for epileptic seizure classification. 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 2018:3578–3581. doi: 10.1109/embc.2018.8513031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varatharajah Y., Joseph B., Brinkmann B., et al. Quantitative analysis of visually reviewed normal scalp EEG predicts seizure freedom following anterior temporal lobectomy. Epilepsia. 2022;63(7):1630–1642. doi: 10.1111/epi.17257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassahun Y., Perrone R., De Momi E., et al. Automatic classification of epilepsy types using ontology-based and genetics-based machine learning. Artif Intell Med. 2014;61(2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Z., Miao C., Schoepf U.J., et al. A clinically applicable deep-learning model for detecting intracranial aneurysm in computed tomography angiography images. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6090. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19527-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faron A., Sichtermann T., Teichert N., et al. Performance of a deep-learning neural network to detect intracranial aneurysms from 3D TOF-MRA compared to human readers. Clin Neuroradiol. 2020;30:591–598. doi: 10.1007/s00062-019-00809-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park Y.K., Yi H.J., Choi K.S., Lee Y.J., Chun H.J. Intraprocedural rupture during endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysm: clinical results and literature review. World Neurosurgery. 2018;114:e605–e615. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishi T., Yamashiro S., Okumura S., et al. Artificial intelligence trained by deep learning can improve computed tomography diagnosis of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage by nonspecialists. Neurol Med -Chir. 2021;61(11):652–660. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2021-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cepeda S., García-García S., Arrese I., Sarabia R. Analysis of intraoperative ultrasound images of brain tumors using radiomics and artificial intelligence. Brain and Spine. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.bas.2021.100467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tandel G.S., Balestrieri A., Jujaray T., Khanna N.N., Saba L., Suri J.S. Multiclass magnetic resonance imaging brain tumor classification using artificial intelligence paradigm. Comput Biol Med. 2020;122 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil S., Kirange D. Ensemble of deep learning models for brain tumor detection. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;218:2468–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alnowami M., Taha E., Alsebaeai S., Anwar S.M., Alhawsawi A. MR image normalization dilemma and the accuracy of brain tumor classification model. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences. 2022;15(3):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jrras.2022.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan D.Z., Luengo I., Barbarisi S., et al. Automated operative workflow analysis of endoscopic pituitary surgery using machine learning: development and preclinical evaluation (IDEAL stage 0) J Neurosurg. 2021;137(1):51–58. doi: 10.3171/2021.6.jns21923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park Y.W., Choi D., Park J.E., et al. Differentiation of recurrent glioblastoma from radiation necrosis using diffusion radiomics with machine learning model development and external validation. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2913. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82467-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murata K., Endo K., Aihara T., et al. Artificial intelligence for the detection of vertebral fractures on plain spinal radiography. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 18;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76866-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Kong J. Deep learning algorithm based on analyzing the effect of posterior cervical vertebral canal decompression angioplasty in the treatment of ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament of cervical spine by CT image. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2021;37(6):1630. doi: 10.12669/pjms.37.6-wit.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yagi M., Michikawa T., Yamamoto T., et al. Development and validation of machine learning-based predictive model for clinical outcome of decompression surgery for lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Spine J. 2022;22(11):1768–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu T., Truong N.D., Nikpour A., Zhou L., Kavehei O. Epileptic seizure classification with symmetric and hybrid bilinear models. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics. 2020;24(10):2844–2851. doi: 10.1109/jbhi.2020.2984128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morey J.R., Zhang X., Yaeger K.A., et al. Real-world experience with artificial intelligence-based triage in transferred large vessel occlusion stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;50(4):450–455. doi: 10.1159/000515320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen G., Lu M., Shi Z., et al. Development and validation of machine learning prediction model based on computed tomography angiography–derived hemodynamics for rupture status of intracranial aneurysms: a Chinese multicenter study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:5170–5182. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staartjes V.E., Sebök M., Blum P.G., et al. Development of machine learning-based preoperative predictive analytics for unruptured intracranial aneurysm surgery: a pilot study. Acta Neurochir. 2020;162:2759–2765. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams S., Layard Horsfall H., Funnell J.P., et al. Artificial intelligence in brain tumour surgery—an emerging paradigm. Cancers. 2021;13(19):5010. doi: 10.3390/cancers13195010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balamurugan S., Agrawal A., Kato Y., Sano H. Intra operative indocyanine green video-angiography in cerebrovascular surgery: an overview with review of literature. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2011;6(2):88–93. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.92168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oermann E.K., Kress M.A., Collins B.T., et al. Predicting survival in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery using artificial neural networks. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(6):944–952. doi: 10.1227/neu.0b013e31828ea04b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orringer D., Lau D., Khatri S., et al. Extent of resection in patients with glioblastoma: limiting factors, perception of resectability, and effect on survival. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(5):851–859. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.JNS12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bondiau P.Y., Malandain G., Chanalet S., et al. Atlas-based automatic segmentation of MR images: validation study on the brainstem in radiotherapy context. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(1):289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dundar T.T., Yurtsever I., Pehlivanoglu M.K., et al. Machine learning-based surgical planning for neurosurgery: artificial intelligent approaches to the cranium. Frontiers in Surgery. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.863633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcus A.P., Marcus H.J., Camp S.J., Nandi D., Kitchen N., Thorne L. Improved prediction of surgical resectability in patients with glioblastoma using an artificial neural network. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62160-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moradmand H., Aghamiri S.M., Ghaderi R., Emami H. The role of deep learning‐based survival model in improving survival prediction of patients with glioblastoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10(20):7048–7059. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh K.L., Chen C.Y., Lo C.M. Quantitative glioma grading using transformed gray-scale invariant textures of MRI. Comput Biol Med. 2017;83:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao Y., Liao W., Cao D., et al. An artificial neural network model for glioma grading using image information. Zhong nan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban= Journal of Central South University. Medical Sciences. 2018;43(12):1315–1322. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J., Qian Z., Tao L., et al. Resting state fMRI feature-based cerebral glioma grading by support vector machine. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:1167–1174. doi: 10.1007/s11548-014-1111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morell A., Eichberg D., Shah A., et al. CNTM-01. Evaluating traditional and non-traditional eloquent areas in patients with brain tumors: large-scale network analysis using a machine learning-based platform. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(6):vi224. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001880_506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu S.L., Xiao F.R., Cheng J.C., et al. Randomized multi-reader evaluation of automated detection and segmentation of brain tumors in stereotactic radiosurgery with deep neural networks. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(9):1560–1568. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudie J.D., Rauschecker A.M., Bryan R.N., Davatzikos C., Mohan S. Emerging applications of artificial intelligence in neuro-oncology. Radiology. 2019;290(3):607–618. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pennig L., Shahzad R., Caldeira L., et al. Automated detection and segmentation of brain metastases in malignant melanoma: evaluation of a dedicated deep learning model. Am J Neuroradiol. 2021;42(4):655–662. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.a6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yogananda C.G., Shah B.R., Vejdani-Jahromi M., et al. A fully automated deep learning network for brain tumor segmentation. Tomography. 2020;6(2):186–193. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2019.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beig N., Bera K., Tiwari P. Introduction to radiomics and radiogenomics in neuro-oncology: implications and challenges. Neuro-Oncology Advances. 2020;2(4):iv3–14. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lohmann P., Galldiks N., Kocher M., et al. Radiomics in neuro-oncology: basics, workflow, and applications. Methods. 2021;188:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galldiks N., Zadeh G., Lohmann P. Artificial intelligence, radiomics, and deep learning in neuro-oncology. Neuro-oncology advances. 2020;2(4):iv1–2. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mouraviev A., Detsky J., Sahgal A., et al. Use of radiomics for the prediction of local control of brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(6):797–805. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakai Y., Yang C., Kihira S., et al. MRI radiomic features to predict IDH1 mutation status in gliomas: a machine learning approach using gradient tree boosting. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8004. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kotecha R., Aneja S. Opportunities for integration of artificial intelligence into stereotactic radiosurgery practice. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(10):1629–1630. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zade A.E., Haghighi S.S., Soltani M. Deep neural networks for neuro-oncology: towards patient individualized design of chemo-radiation therapy for Glioblastoma patients. J Biomed Inf. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2022.104006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iqbal J., Jahangir K., Mashkoor Y., et al. The future of artificial intelligence in neurosurgery: a narrative review. Surg Neurol Int. 2022;13 doi: 10.25259/SNI_877_2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sridhar A.N., Briggs T.P., Kelly J.D., Nathan S. Training in robotic surgery—an overview. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0710-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugiyama T., Clapp T., Nelson J., et al. Immersive 3-dimensional virtual reality modeling for case-specific presurgical discussions in cerebrovascular neurosurgery. Operative neurosurgery. 2021;20(3):289–299. doi: 10.1093/ons/opaa335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zoli M., Bongetta D., Raffa G., Somma T., Zoia C., Della Pepa G.M. Young neurosurgeons and technology: survey of young neurosurgeons section of Italian society of neurosurgery (società italiana di Neurochirurgia, SINch) World Neurosurgery. 2022;162:e436–e456. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ribeiro M.T., Singh S., Guestrin C. InProceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2016. Why should i trust you?" Explaining the predictions of any classifier; pp. 1135–1144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Senders J.T., Arnaout O., Karhade A.V., et al. Natural and artificial intelligence in neurosurgery: a systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(2):181–192. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cabitza F., Rasoini R., Gensini G.F. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine. JAMA. 2017;318(6):517–518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biundo E., Pease A., Segers K., de Groote M., d'Argent T., de Schaetzen E. Deloitte & MedTech Europe; 2020. The Socio-Economic Impact of AI in Healthcare; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katsuura Y., Colón L.F., Perez A.A., Albert T.J., Qureshi S.A. A primer on the use of artificial intelligence in spine surgery. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2021 Nov 1;34(9):316–321. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Panesar S.S., Kliot M., Parrish R., Fernandez-Miranda J., Cagle Y., Britz G.W. Promises and perils of artificial intelligence in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(1):33–44. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rashidian N., Hilal M.A. Applications of machine learning in surgery: ethical considerations. Artificial Intelligence Surgery. 2022;2:18–23. doi: 10.20517/ais.2021.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seyyed-Kalantari L., Zhang H., McDermott M.B., Chen I.Y., Ghassemi M. Underdiagnosis bias of artificial intelligence algorithms applied to chest radiographs in under-served patient populations. Nat Med. 2021;27(12):2176–2182. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01595-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abedi V., Kawamura Y., Li J., Phan T.G., Zand R. Machine learning in action: stroke diagnosis and outcome prediction. Front Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.984467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morley J., Machado C.C.V., Burr C., et al. The ethics of AI in health care: a mapping review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;260 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abràmoff M.D., Lou Y., Erginay A., et al. Improved automated detection of diabetic retinopathy on a publicly available dataset through integration of deep learning. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(13):5200–5206. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lopez C.D., Ding J., Trofa D.P., Cooper H.J., Geller J.A., Hickernell T.R. Machine learning model developed to aid in patient selection for outpatient total joint arthroplasty. Arthroplasty Today. 2022;13:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bellini V., Valente M., Del Rio P., Bignami E. Artificial intelligence in thoracic surgery: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(12):6963. doi: 10.21037/jtd-21-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salati M., Migliorelli L., Moccia S., et al. A machine learning approach for postoperative outcome prediction: surgical data science application in a thoracic surgery setting. World J Surg. 2021;45:1585–1594. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu X., Faes L., Kale A.U., et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet digital health. 2019;1(6):e271–e297. doi: 10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Segato A., Marzullo A., Calimeri F., De Momi E. Artificial intelligence for brain diseases: a systematic review. APL Bioeng. 2020;4(4) doi: 10.1063/5.0011697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]