Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy and the biomarkers of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine complexed with full-length NY-ESO-1 protein and a cholesteryl pullulan (CHP) in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) after surgery. We conducted a randomized phase II trial. Fifty-four patients with NY-ESO-1–expressing ESCC who underwent radical surgery following cisplatin/5-fluorouracil–based neoadjuvant chemotherapy were assigned to receive either CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccination or observation as control. Six doses of CHP-NY-ESO-1 were administered subcutaneously once every two weeks, followed by nine more doses once every four weeks. The endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) and safety. Exploratory analysis of tumor tissues using gene-expression profiles was also performed to seek the biomarker. As there were no serious adverse events in 27 vaccinated patients, we verified the safety of the vaccine. DFS in 2 years were 56.0% and 58.3% in the vaccine arm and in the control, respectively. Twenty-four of 25 patients showed NY-ESO-1-specific IgG responses after vaccination. Analysis of intra-cohort correlations among vaccinated patients revealed that 5% or greater expression of NY-ESO-1 was a favorable factor. Comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles revealed that the expression of the gene encoding polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) in tumors had a significantly favorable impact on outcomes in the vaccinated cohort. The high PIGR-expressing tumors that had higher NY-ESO-1-specific IgA response tended to have favorable prognosis. These results suggest that PIGR would play a major role in tumor immunity in an antigen-specific manner during NY-ESO-1 vaccinations. The IgA response may be relevant.

Keywords: Cancer vaccine, Esophageal cancer, NY-ESO-1 antigen, PIGR gene

Introduction

Immunotherapy after surgery is a well-known application of the discipline of cancer immunology [1]. However, many challenges remain to be overcome if immunotherapy is to be adopted as a mainstream cancer treatment.

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer death in the world [2]. Despite the availability of multidisciplinary treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the prognosis for EC has failed to improve. The recommended therapy for clinical stage II and III EC is surgery following chemo-radiotherapy in Western countries, or neoadjuvant chemotherapy in Japan [3, 4]. The standard of care after surgery is careful observation without intervention. However, the rate of recurrence in cases of pathological lymph node metastasis is still high [5], and a multimodal therapy incorporating immunotherapy is expected to be developed.

A remarkable result for an immune checkpoint inhibitor as adjuvant therapy for EC was recently reported [6]. This result of the CheckMate 577 trial may be a breakthrough in subsequent adjuvant therapy. Regardless, challenges remain that require further research on adjuvant therapy for resected EC.

NY-ESO-1 antigen is a cancer-testis antigen that is expressed in tumor tissues as well as in normal testis and placenta. Hence, NY-ESO-1 is considered an ideal target for cancer immunotherapy [7, 8].

Complexes of cholesteryl pullulan (CHP) nanoparticles that contain a tumor antigen are a new type of cancer vaccine that consists of a novel antigen delivery system that presents multiple epitope peptides to both the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II pathways [9]. The CHP cancer vaccine was recently shown to activate macrophages in the lymph node medulla and to induce potent antitumor immunity [10].

We have been developing CHP-protein human cancer vaccines that can efficiently induce immune responses against multiple T-cell epitopes in various tumor antigens [11, 12]. A previous phase I clinical trial using a CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine in patients with refractory esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) showed that a 200 µg dose more efficiently induced immune responses and may lead to better survival benefits than a 100 µg dose [13].

In this study, we aimed to determine the efficacy of CHP-NY-ESO-1 for treating EC in a phase II trial. We also aimed to elucidate the factors that maximize its effectiveness in developing future immunotherapy strategies.

Patients and methods

Preparation of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 complex vaccine

Recombinant full-length NY-ESO-1 protein was prepared for clinical use, and the complex consisting of CHP and the NY-ESO-1 protein was formulated as described previously [14, 15]. All processes were performed following current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). The toxicity of the investigational product was determined using animal models, and stability was monitored during the clinical trial using representative drug samples.

Study design

Patients with clinically diagnosed ESCC in either stage II, III, or IV without distant metastasis were registered in this study. This study was a phase II, multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 complex vaccine (drug code; IMF-001) administered subcutaneously to patients who underwent radical surgery following cisplatin/5-fluorouracil–based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. After their tumor was surgically removed, patients who had NY-ESO-1 antigen-expressing ESCC were randomly divided into two groups, namely CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine and observation (control). Randomization was performed using a minimization method incorporating three factors, namely lymph node metastasis, clinical stage, and study institute.

Primary endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) and safety; secondary endpoints were immune responses, and overall survival (OS). The primary endpoint of DFS was to compare survival after 24 months of follow-up following enrollment of the last patient. DFS was defined by EC recurrence identified either clinically or as a new radiographical lesion by protocol-specified imaging, occurrence of any cancer, or death by any cause. The secondary endpoint of OS was also to compare survival after 24 months of follow-up following enrollment of the last patient. OS was defined as death for any causes. Additionally, plans were made to conduct exploratory studies to determine gene expression in tumors.

The vaccine was composed of 200 µg of NY-ESO-1 protein and was administered subcutaneously within 8 weeks of surgery. The first six doses were administered at two-week intervals for the first 12 weeks were followed by nine more doses at four-week intervals. Patients in both arms were assessed for tumor recurrence by either CT or MRI scans every 12 weeks for the first 107 weeks or until the end of vaccine administration; patients were assessed every 24 weeks thereafter through 131 weeks. Safety was evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events ver.4.0 (NCI-CTCAE ver.4.0).

Major inclusion criteria for trial entry were as follows: patients who were at least 20 years old; had ESCC; had tumor cells that were determined by immunohistochemistry to express NY-ESO-1 antigen; had received preoperative chemotherapy with a regimen containing fluoropyrimidine and platinum and had subsequently undergone esophagectomy with two- or three-field lymphadenectomy (R0-resection: UICC); had clinical stage II, III, or IV disease with supraclavicular lymph node metastasis (UICC Ver.7); and had no serious disorder of any major organs (bone marrow, heart, lung, liver, or kidney). Major exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who had undergone radiotherapy had double cancer or had an autoimmune disease.

This trial was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trial Registry as ID: UMIN000007905.

Tumor expression of NY-ESO-1 antigen

NY-ESO-1 expression in tumor specimens was determined by immunohistochemistry using the monoclonal antibody E978 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) [8]. Tumors stained 5% or greater were considered high-expression, while those that stained less than 5% were considered low-expression. Focally stained samples were also positive, which were considered low-expression.

Serum samples

To measure antigen-specific antibody responses, sera were collected both at baseline and at the time of each vaccination. All sera were stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

Antibody responses to NY-ESO-1 antigen

NY-ESO-1–specific antibodies in sera were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described [16]. The cutoff level for anti-NY-ESO-1 IgG was a value of 0.254 for optical density measured at 450 nm wavelength (OD450). A sample was considered positive for anti-NY-ESO-1 antibody if the OD450–550 absorbance value in ELISA was at the cutoff level or higher at a serum dilution of 1:400. The immune responses of patients with pre-existing anti-NY-ESO-1 antibodies were judged as augmentation if serum with four-fold or greater dilution remained positive.

Serum anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA was measured by ELISA using an anti-human IgA antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). IgA levels were calculated from standard curves for OD450 values using multiple dilutions of control human IgA. Serum anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA in the vaccinated patients was determined by subtracting the serum anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA value of healthy volunteers.

Gene expression profiles

All esophageal tumors used for gene expression profiles were surgically resected. Total RNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples was quality checked using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Messenger RNA (mRNA) was amplified with a Sensation™ RNA amplification kit (Genisphere, Hatfield, PA, USA). A total of 28,869 mRNA expression profiles were obtained on GeneChip™ Human 1.0 ST Arrays, Applied Biosystems™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). By comparing the gene expression profiles of different patient groups, we identified genes that changed by greater than two times or less than 0.5 relatives to the standard using a cutoff of p < 0.01 significance in our SAM t-test.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy analyses were performed on the per-protocol set (PPS) that consisted of all patients who completed the study without major protocol deviations. Continuous variables are represented as medians and ranges, whereas categorical variables are represented as frequencies and proportions. To examine differences between groups, we used either Student's t-test or Fisher's exact test. Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by Greenwood's formula, and comparisons between groups were made using the log-rank test. Furthermore, we performed exploratory subgroup analyses on gene expression profiles, and a Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine treatment interactions with each of these factors in order to explore suitable targets for the NY-ESO-1 vaccine. We used the median signaling intensity in tissue samples as a cutoff for our gene expression profiles to define two gene expression subgroups. Moreover, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was used to determine the factors for more accurately predict response to the cancer vaccine. Statistical tests were two-sided and significance was defined using a cutoff of p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS ver.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient disposition

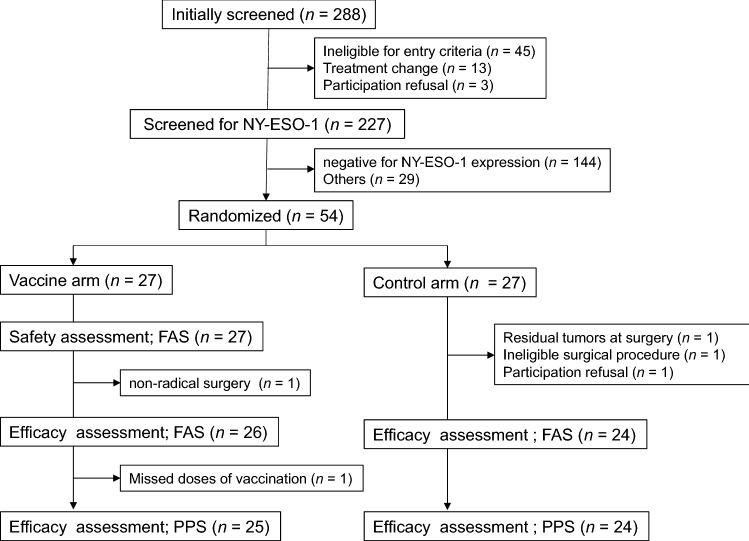

After screening 288 patients, the final number of patients enrolled was 27 in each arm between October 23, 2012, and October 30, 2015. Following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy was performed. After surgery, patients were screened for NY-ESO-1 antigen expression and 83 of 227 (36.6%) were identified as positive. Two hundred thirty-four patients were excluded due to either antigen negativity or other inclusion/exclusion criteria. Finally, 54 patients were randomized to either the NY-ESO-1 vaccine arm or the control arm. A safety evaluation was performed on the 27 vaccinated patients. In the vaccine arm, 25 patients were assessed for efficacy, while two were excluded; one of the two excluded patients had non-radical resection and missed vaccine doses. In the control arm, 24 patients were assessed for efficacy while three were excluded, one each because of residual tumor, an ineligible surgical procedure, and refusal to participate (Fig. 1). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There was no difference in the background profiles of the vaccine and control arms.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the clinical trial. PPS, per-protocol set; FAS, full analysis set

Table 1.

Patients profiles between the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine and the control arm

| Vaccine arm (%) | Control arm (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 24 (96) | 23 (96) | 0.74 |

| Female | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | ||

| Age (Median, range) | 65.0 (48–76) | 63.0 (46–75) | 0.41 | |

| Clinical stage | II | 9 (36) | 6 (25) | 0.76 |

| III | 15 (60) | 17 (71) | ||

| IV | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | ||

| Docetaxel treatment* | Combined | 10 (40) | 7 (29) | 0.55 |

| Not combined | 15 (60) | 17 (71) | ||

| Esophagectomy | With thoracotomy | 10 (40) | 5 (21) | 0.12 |

| Thoracoscopical | 15 (60) | 19 (79) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | Negative | 6 (24) | 6 (25) | 0.59 |

| Positive | 19 (76) | 18 (75) | ||

| NY-ESO-1 expression | < 5% (low-expression) | 13 (52) | 14 (58) | 0.43 |

| 5% or > (high-expression) | 12 (48) | 10 (42) | ||

| Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Grade 0 | 3 (12) | 5 (21) | 0.63 |

| Grade 1a | 13 (52) | 11 (46) | ||

| Grade 1b | 4 (16) | 3 (13) | ||

| Grade 2 | 3 (12) | 5 (21) | ||

| Grade 3 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

*Docetaxel was administered in addition to a regimen of fluoropyrimidine and platinum

Safety and toxicity

In the 27 patients evaluable for vaccine safety, skin reactions occurred at the vaccine injection site in 25 of 27 (92.6%) vaccinated patients; these were grade 2 events in two patients and grade 1 events in the remaining patients. Apart from skin reactions, a total of five adverse events occurred in four of the 27 patients (14.8%). The four events included oral discomfort (grade 1), general malaise (grade 1), fever (grade 1), and urticaria (grade 2). A grade 3 γ-GTP elevation was observed in one patient (3.7%).

Efficacy assessments

Fifty-four patients were enrolled; 27 were randomized to the NY-ESO-1 vaccine arm while 27 were randomized to the control arm (Fig. 1). Twenty-seven vaccinated patients were evaluated for the safety assessment. In the vaccine arm, two patients were excluded, and 25 were assessed for efficacy. In the control arm, three were excluded and 24 patients were assessed for efficacy (Fig. 1). There were no different background profiles between the vaccine arm and the control (Table 1).

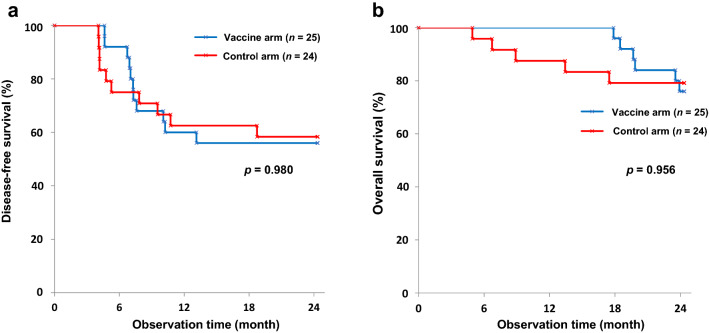

DFS in 2 years were 56.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 34.8–72.7) and 58.3% (95% CI: 36.4–75.0) in the vaccine and control arms, respectively. OS in 2 years were 76.0% (95% CI: 54.2–88.4) and 79.2% (95% CI: 57.0–90.8), respectively. No statistical differences were seen between the vaccine and control arms, with p-values of 0.980 (log-rank test) and 0.956 (log-rank test), respectively (Fig. 2a, b). As shown in Fig. 2b, no death was observed during the first 18 months among vaccinated patients.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves. a DFS rates at 2 years were 56.0% (95 CI 34.8–72.7) and 58.3% (95% CI 36.4–5.0) in the vaccine and control arms, respectively (p = 0.980). b OS rates at 2 years were 76.0% (95% CI 54.2–88.4) and 79.2% (95% CI 57.0–90.8) in the vaccine and control arms, respectively (p = 0.956). DFS, disease-free survival; CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival

Tumor expression of NY-ESO-1

As shown in Table 1, 22 patients (12 in the vaccine arm and 10 in the control arm) constituted the highly positive group; they demonstrated NY-ESO-1 expression in 5% or more expression of the tumor area; these individuals comprised the high-expression group. The weak-positive group included 27 patients (13 in the vaccine arm and 14 in the control arm) with < 5% expression. Of the 25 patients in the vaccine arm, 12 (48.0%) were high-expression group while 13 (52.0%) were low-expression group. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, in the vaccine arm, high-expression patients had marginally superior DFS compared to low-expression patients, whereas, in the control arm, there was no difference between the two groups for as long as two years. The observed interactions between vaccine efficacy and tumor expression of NY-ESO-1 were almost statistically significant in DFS (p = 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves. Intra-cohort analysis of vaccine arm and control arm by NY-ESO-1 expression on tumors and pre-existing antibody to NY-ESO-1. a DFS of the vaccine cohort. 5% or more expression (high-expression) NY-ESO-1 group (n = 12) versus < 5% (low-expression) group (n = 13) (p = 0.059). b DFS of the control cohort (p = 0.418). c DFS of the vaccine cohort. Pre-existing antibody positive (n = 8) versus antibody negative (n = 17) (p = 0.211). d DFS of the control cohort (p = 0.277). DFS, disease-free survival

NY-ESO-1-specific IgG responses after vaccination

As shown in Table 2, 8 patients (32.0%) had antibodies to NY-ESO-1, and 17 (68.0%) did not, prior to the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccination. All 17 patients without antibodies became seropositive after vaccinations, and the antibody titers increased in seven of the eight patients who were seropositive before the vaccinations. In total, 24 of 25 (96.0%) patients had immune responses after vaccinations. In terms of the impact on clinical outcomes by pre-vaccination antibody status, no differences in DFS were seen between patients with and without pre-existing antibodies to NY-ESO-1 (Fig. 3c, d).

Table 2.

Humoral immune responses to NY-ESO-1

| Pre-vaccination (n) | Post-vaccination (n) | Immune response (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seronegative | 17 | Sero-conversion | 17 | 100% (17/17) |

| Seropositive | 8 | Augmentation | 7 | 87.5% (7/8) |

| Total response | 96.0% (24/25) |

Exploratory analysis of gene expression profiles

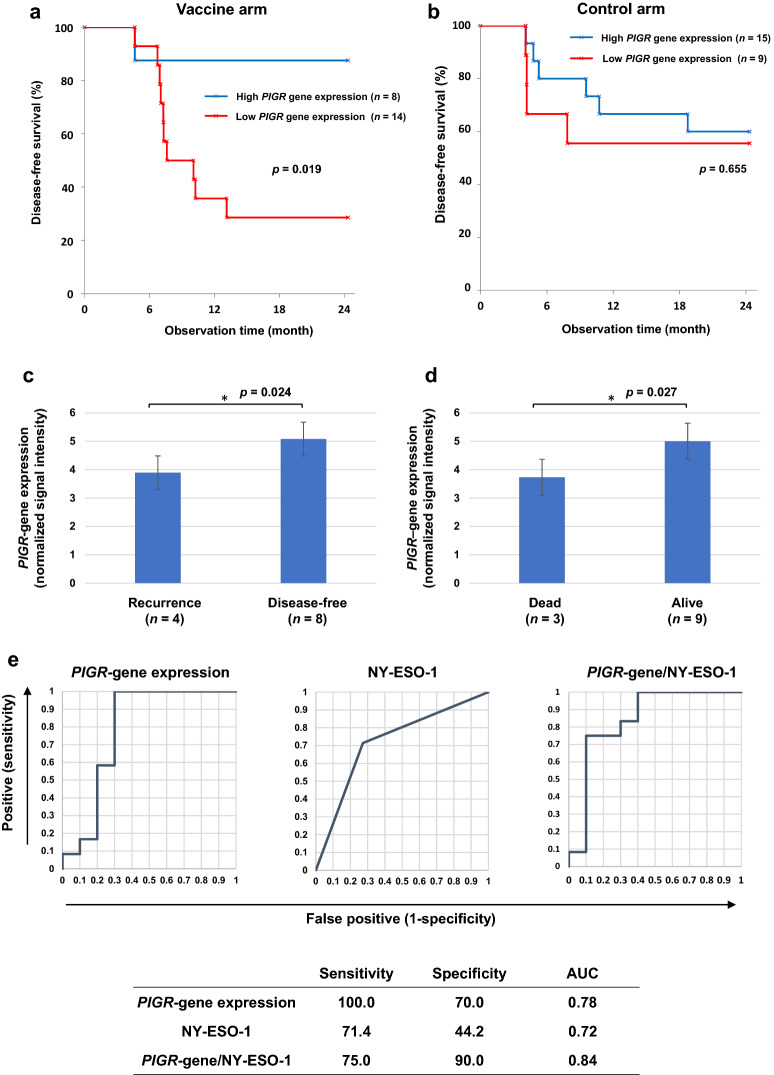

Gene expression profiles of resected esophageal tumor samples were analyzed, and genes related to clinical outcomes, including disease-free status and being alive two years after study onset, were identified. The genes NKG2D (NK group 2 member D) and PIGR (polymeric immunoglobulin receptor) appeared to be significantly upregulated in tumor tissues from patients with favorable outcomes (data not shown). The gene NKG2D was upregulated in both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients who had favorable outcomes, suggesting that patients with NKG2D gene expression have a better prognosis regardless of NY-ESO-1 vaccination (data not shown). In contrast, vaccinated patients in the high PIGR gene expression subgroup had a significantly higher DFS than those in the low PIGR gene expression subgroup (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, the PIGR gene was expressed at significantly higher levels in vaccinated patients whose tumors expressed 5% or more NY-ESO-1 antigen with favorable outcomes (disease-free and alive) (p = 0.024 and p = 0.027, respectively) (Fig. 4c, d). ROC analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) by PIGR expression, NY-ESO-1 expression, and both factors were 0.78, 0.72, and 0.84, respectively (Fig. 4e). Next, we divided the 22 patients into four subgroups based on NY-ESO-1 and PIGR gene expression levels. Those with 5% or greater expressions of NY-ESO-1 and high PIGR expression survived significantly longer than the three subgroups over a two-year period (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Effect of PIGR expression on DFS and its association to NY-ESO-1. a Kaplan–Meier curve. DFS of the vaccine cohort. High-PIGR gene expression (n = 8) versus low expression group (n = 14) (p = 0.019). b DFS of the control cohort (p = 0.655). c PIGR expression on tumors. Patients with disease recurrence after vaccination (n = 4) versus patients with disease-free status (n = 8) (p = 0.024). d Dead (n = 3) versus alive (n = 9) (p = 0.027). e ROC curves of sensitivity and specificity by PIGR gene expression, NY-ESO-1 expression and both of the two factors. AUC is 0.78, 0.72 and 0.84, respectively. f Kaplan–Meier curve. 22 patients were grouped into four subgroups by NY-ESO-1 and PIGR expression status, and those with 5% or more expressions (high-positive) of NY-ESO-1 and high gene expression of PIGR (n = 6) survived significantly longer than the three other subgroups (NY-ESO-1 5% or more (high-expression)/low PIGR, NY-ESO-1 < 5% (low-expression)/high-PIGR, and NY-ESO-1 < 5% (low-expression)/low-PIGR (n = 5, n = 2, n = 9, respectively) (p = 0.031, p = 0.083, p = 0.005, respectively). DFS, disease-free survival; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; AUC, area under the curve

NY-ESO-1-specific IgA responses after vaccination

Since PIGR expression was correlated with a favorable prognosis after the vaccinations, we analyzed serum IgA antibodies in the vaccinated patients, based on the mechanism that PIGR gene is the main regulator of IgA transport in gastrointestinal cells [17].

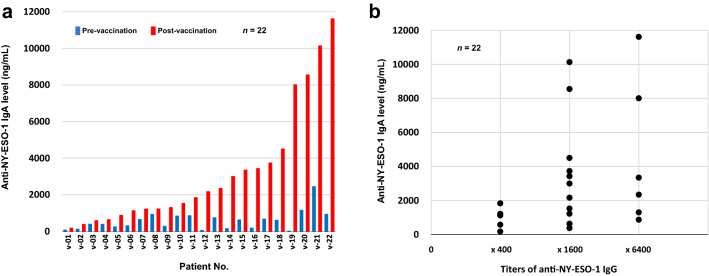

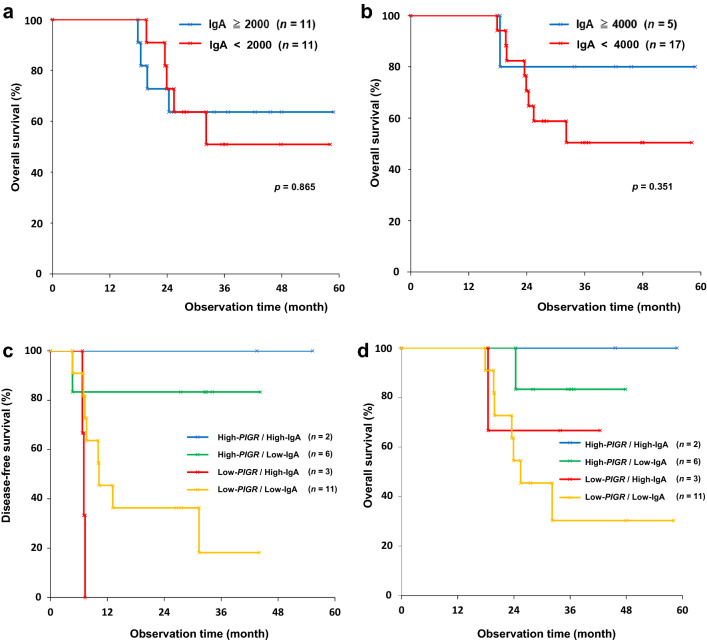

Anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA was measured in 22 esophageal cancer patients who were vaccinated with CHP-NY-ESO-1. Serum was collected prior to the first cycle of the vaccinations and after the final dose. Serum IgA levels to NY-ESO-1 protein were determined by subtracting the serum anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA value of healthy volunteers. Figure 5a illustrates the changes in serum NY-ESO-1-specific IgA in the vaccinated patients between pre-vaccination and post-vaccination, and Fig. 5b shows a comparison of serum NY-ESO-1-specific IgA levels and titers of IgG in the 22 vaccinated patients after vaccination. These data suggest that NY-ESO-1-specific IgA increased after the vaccinations and both IgA and IgG increased to a similar extent in response to the vaccine. The IgA levels exceeded 2000 ng/mL in 11 of 22 patients and 4000 ng / mL in 5 after the vaccinations. For the cutoff point of IgA, the two Kaplan–Meier curves were clearly separated by 4000 ng / mL rather than median 2000 ng / mL of IgA (Fig. 6a and b). The 22 patients were divided into four subgroups by PIGR expression status and NY-ESO-1-specific IgA level. As shown in Fig. 6c and d, those with high PIGR expression (high-PIGR) and high IgA levels (high-IgA) of 4000 ng / mL or more at post-vaccination (n = 2) survived longer than the three other subgroups in terms of DFS and OS.

Fig. 5.

Serum IgA levels to NY-ESO-1 protein. a Serum IgA levels at pre-vaccination and post-vaccination. Serum IgA levels to NY-ESO-1 protein were determined by subtracting the serum anti-NY-ESO-1 IgA value of healthy volunteers. The IgA levels exceeded 2000 ng / mL in 11 of 22 patients and 4000 ng / mL in 5 after vaccinations. b Comparison of serum NY-ESO-1-specific IgA and tiers of IgG in 22 vaccinated patients after vaccination

Fig. 6.

Kaplan–Meier curves. a OS of the vaccine cohort. Patients with IgA responses of 2000 ng / mL or more (n = 11) versus those with < 2,000 ng / mL (n = 11). (p = 0.865) b OS of the vaccine cohort. Patients with IgA responses of 4,000 ng / mL or more (n = 5) versus those with < 4000 ng / mL (n = 17). (p = 0.351) c DFS of 22 patients who were divided into four subgroups by PIGR expression status and NY-ESO-1-specific IgA level. Those with high gene expression of PIGR (high-PIGR) and high IgA levels (high-IgA) of 4000 ng / mL or more at post-vaccination (n = 2) survived longer than the three other subgroups; high-PIGR/low-IgA (< 4000 ng / mL) (n = 6), low-PIGR/high-IgA (n = 3), or low-PIGR/low-IgA (n = 11). The patients were assessed for tumor recurrence by CT scans every 12 weeks for the first 107 weeks or until the end of vaccine administration. They were assessed every 24 weeks thereafter through 131 weeks. d OS. Patients with high gene expression of PIGR (high-PIGR) and high IgA levels of 4,000 ng / mL or more (n = 2) survived longer than the three other subgroups

Discussion

Here, we report the results of a randomized phase II trial that investigated the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine administered in the adjuvant setting to patients with surgically resected NY-ESO-1–expressing ESCC in either clinical stage II, III, or IV. Regarding the primary endpoint, although we verified the safety of the vaccine, we did not observe an improvement in DFS between the vaccine cohort and the control. This result may be due to an imbalance between cohorts because the preoperative chemotherapy regimen allowed for docetaxel in addition to fluoropyrimidines and platinum in this study. However, the number of cases in this study was limited, and no significant difference was obtained even after making adjustments to our analysis for the regimen.

In this trial, the antigen-specific IgG response was used as a surrogate marker for the T cell responses, as previously described [13]. Although T cells that are induced by a cancer vaccine should be evaluated as an immune-monitoring marker, T cells responses can be difficult to detect directly and quantitatively assess, whereas IgG titers measured by ELISA could act as a suitable immune-monitoring marker. Here, we observed solid results for the immune response as the secondary endpoint. All patients without antibodies became seropositive after vaccination, and 90% of patients who were seropositive before vaccination had elevated antibody titers. Based on this result, we concluded that this vaccine can promote the production of anti-NY-ESO-1 antibodies as a surrogate marker of T cell responses.

To explore factors that would be associated with clinical outcomes, we investigated the levels of NY-ESO-1 expression in tumors, which is the target of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine. NY-ESO-1 expression has been reported as a negative prognostic factor in various tumors [18, 19]. Our previous clinical study involving the MAGE-A4 vaccine for treating patients with head/neck and esophageal cancer showed that survival was significantly shorter in those whose tumors co-expressed NY-ESO-1 [20]. However, it is not yet known whether the prognosis would be influenced by the intensity of NY-ESO-1 expression when immunotherapies are given. In doing so, we found that prognosis is inversely correlated with NY-ESO-1 expression level. In the current study, among patients with ≥ 5% NY-ESO-1 tumor expression, the vaccination group demonstrated superior survival compared to the control. Having these findings, we assume that the vaccine elicited/enhanced antibody responses to NY-ESO-1 and eventually induced T cell responses to antigen-expressing tumors. In tumors with strong antigen expression, high presentation of antigen peptides to MHC can be presumed to have induced high anti-NY-ESO-1 reaction. Thus, the trial suggested that the vaccine might have effectively induced T cell responses to NY-ESO-1-expressing tumors and that it could lead to anti-tumor effects in highly NY-ESO-1-expressing tumors.

As an exploratory study, we measured mRNA levels of 28,869 genes in resected esophageal tumor tissue and analyzed the correlations between genes that were either upregulated or downregulated and clinical prognosis of DFS or OS. Among them, we found that both NKG2D and PIGR expression were upregulated in the group with favorable prognosis. In particular, we found that PIGR expression was significantly upregulated in vaccinated patients with favorable prognosis compared with those with unfavorable prognosis. PIGR is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and transports IgA or IgM from the basolateral surface of the epithelium to the apical side. Upon reaching the luminal side, a portion of PIGR, called the secretory component, is cleaved off to release Ig, forming a secretory Ig in the process. Secretory Ig functions as a mucosal surface defense against microbes in the gastrointestinal tract [17]. PIGR expression is regulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-4, TNF-α, and IFN-γ [17, 21–24]. The correlation between PIGR expression and tumor progression was previously reported in a study which found that patients with high PIGR expression in esophageal tumors had a favorable prognosis whereas patients with low PIGR expression in pancreatic tumors had an unfavorable outcome [25, 26]. PIGR was recently reported to play a central role in promoting tumor immunity in ovarian cancer and PIGR-mediated IgA transcytosis and antigen recognition are strongly involved in the control of refractory ovarian cancer [27]. Tumor-antigen-specific and -antigen-independent IgA responses suppress ovarian tumor growth by the PIGR-mediated mechanism [27].

Since PIRG gene expression was found to be involved in favorable prognosis. We measured NY-ESO-1 antigen-specific IgA in 22 patients in the vaccine group as an additional analysis. The analysis revealed that the NY-ESO-1-specific IgA was induced by the vaccinations, and then we focused on 5 cases with high IgA levels of 4000 ng / mL or more to analyze whether there was an additive prognostic improvement with PIGR expression. Our findings could suggest that DFS and OS were prolonged in patients with high PIGR expression and high IgA response. Thus, we could speculate that the anti-tumor effect was dominantly mediated by antigen-specific immune responses.

In the current clinical study, we found that the combination of high NY-ESO-1 expression in tumors, which is the target antigen of this vaccine, and high PIGR gene expression leads to a favorable prognosis without tumor recurrences in vaccinated patients. Moreover, the corresponding ROC analysis showed that the combination of NY-ESO-1 and PIGR gene expression predicts favorable outcomes with high sensitivity and specificity. Although pre-existing IgG levels did not seem to be related to the prognosis in this trial, a future clinical study can help determine if serum IgA levels to NY-ESO-1 are related to clinical prognosis. Therefore, the interaction between humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity may be the key to maximizing the effectiveness of post-operative cancer vaccines. The results of Checkmate 577 demonstrated that PD-1 blockade for EC as an adjuvant therapy is breakthrough in subsequent adjuvant cancer treatment [6]. Although it may be necessary to compare it with chemotherapy as a postoperative adjuvant therapy, this result has strongly encouraged further investigation of the mechanism of cancer immunotherapy, especially in the search for relevant biomarkers.

In conclusion, this trial did not demonstrate the clinical efficacy of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine. However, the trial results suggest that this vaccine may be efficacious in high NY-ESO-1-expressing and high PIGR gene–expressing esophageal tumors. They also suggest that PIGR would play a major role in tumor immunity in an antigen-specific manner during NY-ESO-1 vaccinations. The IgA response may also be relevant.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who took part in this study, their caregivers, and the co-medical staff, data managers, and clinical coordinators. Ms.Sahoko Sugino and Ms. Junko Nakamura (Mie University) provided technical assistance with the ELISA assay. We thank all co-workers from FIVERINGS CO., LTD. for operating this study.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- cGMP

Current good manufacturing practices

- CI

Confidence interval

- CHP

Cholesteryl pullulan

- CT

Computed tomography

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- EC

Esophageal cancer

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- γ-GTP

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- IgA

Immunoglobulin A

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- IL-1

Interleukin-1

- IL-4

Interleukin-4

- MAGE-A4

Melanoma-associated gene-A4

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NCI-CTCAE

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- NKG2D

NK group 2 member D

- NY-ESO-1

New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1

- OD

Optical density

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed-cell death-1

- PIGR

Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- PPS

Per-protocol set

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristics

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- UICC

Union for International Cancer Control

- UMIN

University hospital medical information network

Author contributions

YN, SK, TY, and HS contributed to the design of the study. YN, TI, SK, TO, TA, MM, KO, TA, TK, KT, SK, HS, SY, TS, SH, TT, TS, SU, KK, AY, HW, YD, HY, MK, MO, HY, KK, MK, YK, and MK contributed to patient recruitment, treatment, and clinical data collection. YM, NG, EF, and KY contributed to immune reaction data. TS and ES contributed to immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissues. YN, SK, HI, TY, MO, KH, HM, and TW interpreted the data. TY and MO performed the statistical analyses. YN and SK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to draft revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The trial was supported by research funding from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan between April 2011 and March 2015, and then supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) between April 2015 and March 2018 (Grant Number JP17ck0106143).

Data availability

To protect patient information in the clinical trial database, the datasets generated and/or analyzed in the present study are not publicly available, but they are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in our studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Research, Japanese Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and the Helsinki Declaration. The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol and the informed consent documents and their amendments before use (Mie University approval number F2408005).

Informed consent

Written informed consent to participate in the study and for the use of clinical data for research and publication was obtained from all patients included in the studies: Mie University approval number F2408005.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shinichi Kageyama, Email: kageyama@med.mie-u.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Shiku, Email: shiku@med.mie-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Boon T. Tumor antigens recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes: present perspectives for specific immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:177–180. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando N, Kato H, Igaki H, et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907) Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:68–74. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayanagi S, Irino T, Kawakubo H, Kitagawa Y. Neoadjuvant treatment strategy for locally advanced thoracic esophageal cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:269–275. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. New Engl J Med. 2021;384:1191–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YT, Scanlan MJ, Sahin U, et al. A testicular antigen aberrantly expressed in human cancers detected by autologous antibody screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1914–1918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jungbluth AA, Chen YT, Stockert E, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of NY-ESO-1 antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:856–860. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu XG, Schmitt M, Hiasa A, et al. A novel hydrophobized polysaccharide/oncoprotein complex vaccine induces in vitro and in vivo cellular and humoral immune responses against HER2- expressing murine sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3385–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muraoka D, Harada N, Hayashi T, et al. Nanogel-based immunologically stealth vaccine targets macrophages in the medulla of lymph node and induces potent antitumor immunity. ACS Nano. 2014;8:9209–9218. doi: 10.1021/nn502975r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikuta Y, Katayama N, Wang L, et al. Presentation of a major histocompatibility complex class 1-binding peptide by monocyte-derived dendritic cells incorporating hydrophobized polysaccharide-truncated HER2 protein complex: implications for a polyvalent immuno-cell therapy. Blood. 2002;99:3717–3724. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitano S, Kageyama S, Nagata Y, et al. HER2-specific T-cell immune responses in patients vaccinated with truncated HER2 protein complexed with nanogels of cholesteryl pullulan. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7397–7405. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kageyama S, Wada H, Muro K, et al. Dose-dependent effects of NY-ESO-1 protein vaccine complexed with cholesteryl pullulan (CHP-NY-ESO-1) on immune responses and survival benefits of esophageal cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2013;11:246. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy R, Green S, Ritter G, et al. Recombinant NY-ESO-1 cancer antigen: Production and purification under cGMP conditions. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2005;35:119–134. doi: 10.1081/PB-200054732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akiyoshi K, Kobayashi S, Shichibe S, et al. Self-assembled hydrogel nanoparticle of cholesterol-bearing pullulan as a carrier of protein drugs: complexation and stabilization of insulin. J Control Release. 1998;54:313–320. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockert E, Jäger E, Chen Y-T, et al. A survey of the humoral immune response of cancer patients to a panel of human tumor antigens. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1349–1354. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaetzel CS. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor: Bridging innate and adaptive immune responses at mucosal surfaces. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:83–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figueiredo DLA, Mamede RCM, Spagnoli GC, et al. High expression of cancer testis antigens MAGE-A, MAGE-C1/CT7, MAGE-C2/CT10, NY-ESO-1, and gage in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Head Neck. 2011;33:702–707. doi: 10.1002/hed.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szender JB, Papanicolau-Sengos A, Eng KH, et al. NY-ESO-1 expression predicts an aggressive phenotype of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueda S, Miyahara Y, Nagata Y, Sato E, Shiraishi T, Harada N, Ikeda H, Shiku H, Kageyama S. NY-ESO-1 antigen expression and immune response are associated with poor prognosis in MAGE-A4-vaccinated patients with esophageal or head/neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(89):35997–36011. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi M, Takenouchi N, Asano M, et al. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (secretory component) in a human intestinal epithelial cell line is up-regulated by interleukin-1. Immunology. 1997;92:220–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piskurich JF, France JA, Tamer CM, et al. Interferon-γ induces polymeric immunoglobulin receptor mrna in human intestinal epithelial cells by a protein synthesis dependent mechanism. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:413–421. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90071-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon C, VanDussen KL, Miyoshi H, Stappenbeck TS. Development of a primary mouse intestinal epithelial cell monolayer culture system to evaluate factors that modulate IgA transcytosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:818–828. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar P, Monin L, Castillo P, et al. Intestinal Interleukin-17 receptor signaling mediates reciprocal control of the gut microbiota and autoimmune inflammation. Immunity. 2016;44:659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fristedt R, Gaber A, Hedner C, et al. Expression and prognostic significance of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med. 2014;12:83. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fristedt R, Elebro J, Gaber A, et al. Reduced expression of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in pancreatic and periampullary adenocarcinoma signifies tumour progression and poor prognosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biswas S, Mandal G, Payne KK, et al. IgA transcytosis and antigen recognition govern ovarian cancer immunity. Nature. 2021;591:464–470. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

To protect patient information in the clinical trial database, the datasets generated and/or analyzed in the present study are not publicly available, but they are available from the corresponding author on request.