Abstract

Benzene is a carcinogenic volatile organic compound (VOC) that is ubiquitously detected in enclosed spaces due to emissions from cooking activities, building materials, and cleaning products. To remove benzene and other VOCs from indoor air and protect public health, traditional fabric filters have been modified to contain activated carbons to enhance the filtration efficacy. In this study, composites derived from natural clay minerals and activated carbon were individually green-engineered with chlorophylls and were attached to the surface of filter materials. These systems were assessed for their adsorption of benzene from air using in vitro and in silico methods. Isothermal, thermodynamic, and kinetic experiments indicated that all green-engineered composites had improved binding profiles for benzene, as demonstrated by increased binding affinities (Kf ≥ 900 vs 472) and lower values of Gibbs free energy (ΔG = −16.8 vs −15.2) compared to activated carbon. Adsorption of benzene to all composites was achieved quickly (< 30 min), and the green-engineered composites also showed low levels of desorption (≤ 25%). While free chlorophyll is known to be photosensitive, chlorophylls in the green-engineered composites showed photostability and maintained high binding rates (≥ 70%). Additionally, the in silico simulations demonstrated the significant contribution of chlorophyll for the overall binding of benzene in clay systems and that chlorophyll could contribute to benzene binding in the carbon-based systems. Together, these studies indicated that novel, green-engineered composite materials can be effective filter sorbents to enhance the removal of benzene from air.

Keywords: Green-engineering, Filters, Montmorillonite, Activated carbon, Adsorption isotherms, Chlorophyll

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies air pollution as a worldwide health concern and the largest environmental risk to human health [72]. While outdoor conditions are traditionally more studied, indoor air quality (IAQ) is an important contributor to human health as the average person can spend up to 90% of their time in enclosed spaces. Interestingly, IAQ has been reported to be up to 2 times lower than that of outdoor air [21]. Globally, poor IAQ has been shown to affect nearly 3 billion individuals each day and contribute to over 4 million deaths annually [21,73]. In addition to the presence of particulate matter, the levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other chemical pollutants are among the most significant and hazardous contributors to poor IAQ [58,61]. Indoor areas may contain up to 10 times higher levels of VOCs than outdoor spaces, likely due to low ventilation rates in buildings and vehicles, emissions from synthetic building materials and household products, and cooking activities [21,71,72].

Benzene is a VOC that is commonly detected in ambient indoor and outdoor air; however, concentrations indoors are generally higher than those measured outside, except near gas stations, industrial sites, and hazardous locations [1,71]. Benzene is a known human carcinogen and has been linked to the development of acute myeloid leukemia and other hematological diseases in humans [71]. In the United States, the average indoor benzene levels range from 2.6–5.8 μg/m3 [71], which is lower than the reference concentration derived by the US Environmental Protection Agency (30 μg/m3) [19]. However, the levels indoors can be increased by several factors, like incense burning and the use of kerosene stoves or lamps, which have been linked to high concentrations of 117 μg/m3 and 44–167 μg/m3, respectively [71]. Homes located closer to gas stations have also been shown to have distance-dependent levels of benzene indoors [7]. Importantly, tobacco smoke serves as the largest contributor to indoor benzene levels, and chronic smoking can increase benzene concentrations up to 300% [71]. Extended benzene exposure caused by these activities is a health concern because chronic exposure to airborne benzene above 13–45 μg/m3 increases the cancer risk from 1 in a million to 1 in ten thousand [19], and the residence time of benzene can be up to 2 weeks [71]. Additionally, chronic inhalation of just 3.2 μg/m3 of benzene has been linked to several hematological disorders and a slight increase in excess deaths due to leukemia [36]. Therefore, strategies that reduce the levels of benzene indoors could be used to mitigate the health risks of chronic exposure, especially in areas that are subjected to chronic benzene pollution.

Several methods have been previously used to remove benzene and other VOCs from air, including condensation reactions, air-sparging, and catalytic oxidation. However, these methods can produce secondary pollutants from incomplete combustion or oxidation reactions, require high levels of energy, and are limited in their ability to remove residentially-relevant levels of benzene and other VOCs [38]. Air scrubbers have been used to capture VOCs from contaminated air in industrial settings, and smaller-scale versions that connect to HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems have been developed for residential use. This technology can be expensive, requires a working HVAC system, and needs regular cleaning and maintenance to maintain high removal efficiencies [44]. Therefore, there is a need for an economically-feasible air purification technology that can be used in residential settings to reduce contaminant levels and protect public health.

Widely available materials like high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA), pleated/fiberglass filters, and personal mask filter materials are designed to remove particulate matter from indoor air and, therefore, are not efficient at capturing VOCs [64]. Moreover, these filter materials have been modified to contain embedded sorbent material, traditionally activated carbons, to increase the adsorption of VOCs from air [33,34, 78]. However, some of these activated carbon-based filtration systems have shown limited retention of benzene on their surfaces, indicating a low possibility for long-term protection [78]. In addition, activated carbons are known to have variable performance based on their source material, activation method, and relative humidity of the environment [39,46,78]. Traditional carbons derived from coal and coke are costly to produce, making the application in residential filters less economically feasible. Instead, activated carbons derived from ‘waste’ materials, like coconut shells, have been used to create a more economical option that still exhibits high surface area, porosity, and binding capacities [59,78].

As an alternative to carbons, several natural clay minerals have been studied for their ability to bind VOCs. For example, zeolite [44], kaolinite [42], and montmorillonite [15] have been previously shown to bind benzene in the gas phase.

Montmorillonite clays are commonly utilized to create organoclays that are known to have enhanced ability to bind lipophilic chemicals (like benzene) because of favorable intrinsic properties like high surface area and cation exchange capacities of its interlayer ions. Previous studies by our lab demonstrated the increased binding of benzene from water by modification with chlorophyll (a lipophilic, organic molecule) compared to the parent montmorillonites and activated carbon [54,70]. Therefore, chlorophyll was utilized to create composite filter materials because due to: 1) the safety of chlorophyll, 2) it’s demonstrated ability to sorb environmental chemicals like aflatoxin B1 and benzene from water, and 3) the presence of favorable functional groups (aliphatic tail, charged magnesium ion, and aromatic chlorin ring) to promote positive interactions with benzene [54,70]. These results suggested that this organoclay with chlorophyll may show a more favorable adsorption of benzene in air compared to activated carbon and other clay minerals. The current study focused on the development of air purification materials containing a filter material (FM) framework and several types of embedded sorbent composites (SFMs), including unmodified clays and carbons, and green-engineered clays and carbons with chlorophyll. Benzene was chosen as the target chemical in the current study because of its prevalence, toxicity, and use as a representative VOC to assess performance of adsorbents. These materials were tested for their ability to bind benzene from air using: 1) in vitro adsorption analyses, thermodynamic studies, and kinetic experiments and 2) in silico molecular simulations to identify important binding modes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and materials

HPLC grade reagents (benzene, ethanol, n-heptane, chloroform, cyclohexane, hexane, and acetone) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MO) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Nanofiber filtration inserts for face masks were purchased from Filti™ (Kansas City, MO) and used as the framework for embedding materials. Powdered chlorophyll, marketed as a mixture of type a and b, was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). Activated carbons that were derived from diverse source materials (coconut shell, hardwood, bamboo, wood, and coal) were purchased from General Carbon Corporation (Paterson, NJ) and Charcoal House LLC (Crawford, NE). Calcium montmorillonite (CM) and sodium montmorillonite (SM) were obtained from TxESi Inc (Bastrop, TX) and Halliburton (Houston, TX), respectively. Amber VOA vials (40 mL, with unbonded 0.125 in. septum caps) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

2.2. Benzene analysis

Benzene concentrations were determined based on an established HPLC method [5]. Concentrations were measured on a Waters HPLC equipped with a 1525 binary pump, 717 plus autosampler, a 2487 UV/Vis detector (Waters© Corp, Milford, MA), and a XBridge C18 (4.6 mm × 50 mm, 3.5 μm) column. The Breeze® software was used to control the system and collect data. The mobile phase was composed of a 70:30 acetone:water mixture and set to a flow rate of 1.0 mL/minute and an injection volume of 20 μL. Standard curves of benzene in the 5 solvents (ethanol, n-heptane, chloroform, cyclohexane, and hexane) were derived using blank solutions and 10 benzene concentrations (0.05–300 mg/L) with peak areas measured at 202 nm. In general, the retention times of benzene were approximately 1 min with limits of detection of 0.05 ppb (μg/L) (r2 > 0.99). The specific retention times, limits of detection, and r2 values for the 5 calibrations are listed in the supplemental materials (Supplemental Table 1).

2.3. Experimental design and method validation

The adsorption of benzene by various purification materials was measured using previously described methods [33] with modifications. The vessel used was a 40 mL (4E-5 m3) amber volatile organic analysis (VOA) vial with a fitted PFTE/silicone septa. A curved 7 cm steel wire was bonded to the inside neck of the vial to suspend the filter material in the vial. During experiments, the lid was wrapped with parafilm. To determine the optimal extraction method of benzene, the extraction percentages of benzene using an eluotropic series of solvents [35] and various temperatures and mixing methods were initially investigated [33]. Briefly, 15 μL of pure benzene was injected into the VOA vial through the septa using a gas-tight syringe, and the lid was wrapped in parafilm. The benzene was allowed to volatilize in the vial for 4 h. After the 4 h, 30 or 40 mL of each solvent was injected into the vial using a gas-tight syringe. Bottles were left to incubate in the dark for additional 18 h at either 25 °C or 2 °C with mixing on a rocking platform set to 3 rpm (VWR, Radnor, PA) or no mixing. After 18 h, aliquots of each bottle were taken using a gas-tight syringe and analyzed by HPLC to determine the efficacy of the extraction methods for benzene.

2.4. Synthesis of green-engineered composites

Green-engineered materials were synthesized by mixing powdered chlorophyll with 5% (w/v) suspensions of CM (97 cmol/kg) [69], SM (75 cmol/kg) [66], or activated carbon (12 cmol/kg) [18] at 150% cation exchange capacity to saturate exchangeable sites [54]. The suspension was mixed for 24 h then centrifuged and washed 3 times with distilled water to remove excess chlorophyll. The products were dried in a desiccator, ground, and sieved at 100 mesh to produce a uniform particle size. The XRD patterns, FT-IR spectra, and SEM images of CM, SM, CM-chlorophyll, and SM-chlorophyll have been previously reported [70].

To embed the framework material (FM) with sorbents (SFM), nanofiber filters were cut into small, uniform pieces (approximately 2 cm × 3 cm) and weighed (49.3 ± 3.5 mg). Sorbents were loaded onto the material at a rate of 5% (w/w) by adding a calculated amount of a 30 mg/mL sorbent suspension in ethanol to the FM, accounting for an 85% uptake rate as determined from preliminary studies. The sorbent was evenly distributed across the FM using 1 mL of ethanol and pipetting. The SFMs were dried overnight at ambient conditions and then weighed to measure the uptake of sorbent material (51.6 ± 3.7 mg). All composite materials were prepared fresh before each experiment.

2.5. Adsorption and thermodynamics

Adsorption experiments were conducted based on previous studies [33]. For the initial screening study to identify the SFM composite with the highest adsorption of benzene, the control FM and SFMs with diverse types of sorbent materials, including several types of activated carbons, montmorillonites, and green-engineered materials, were hung in the VOA vial using a stainless steel wire, and the vial was capped. The vials were filled with ambient, indoor air that contained relevant levels of CO2, and humidity, measured with a portable air quality monitor (Shkalacar). 15 μL of benzene was injected into the jars using a gas tight syringe, and the lid was wrapped in parafilm. The jar was kept at ambient conditions for 4 h. Batch adsorption isotherms were conducted by injecting different volumes of pure benzene (0.5–15 μL) into jars containing suspended filters and kept at ambient conditions for 4 h. For thermodynamic experiments, isothermal analysis with vials containing SFMs, ambient air, and 0.5–15 μL of benzene were repeated at 2 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C. For these experiments, jars were filled with ambient air from a freezer room (set to 2 °C), the benchtop, and an incubator (set to 37 °C). The temperature, humidity, and CO2 levels in each of these environments was monitored, and values were consistent between measurements.

After the incubation process, the jars were opened, and each SFM was placed in an individual 4 mL amber vial containing 4 mL of n-heptane to extract adsorbed benzene from SFM. The vials were incubated for 18 h at 2 °C on a rocking platform set to 3 rpm. These conditions were identified in the method validation studies and had the highest extraction percentage of benzene (Supplemental Fig.1). After incubation, aliquots of the supernatant were collected and analyzed by HPLC to determine extracted benzene concentrations. The weight of the SFM materials was monitored throughout the experiment to ensure there was no loss of sorbent material (Supplemental Fig. 2).

The amount of benzene adsorbed to the surface of SFMs was determined by triplicate experiments and HPLC analysis and was expressed as grams of benzene sorbed per kg sorbent material. An Rshiny application [20] and TableCurve 2D (Systat Software, Inc.) software were used to: 1) plot the data according to multiple adsorption models (Freundlich, Langmuir, Dubinin-Radushkevich, and Toth), 2) estimate the 95% confidence intervals, and 3) derive important model parameters. The Freundlich model displayed the best fit to the experimental data based on r2 and mean squared error values. The equations, description of constants, estimated model parameters, and correlation coeffiecients for the Langmuir, Dubinin-Radushkevich, and Toth adsorption models are listed in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. For TableCurve 2D, the Freundlich adsorption equation was entered as a user-defined function. The Freundlich equation describes the multilayer adsorption of a chemical onto a heterogenous, unsaturable surface [16]:

| (1) |

Where qe is the amount of benzene adsorbed at equilibrium (g/kg), Kf is the Freundlich constant for adsorption affinity, Ce is the equilibrium concentration of benzene (g/m3), and 1/n is the linearity parameter. The adsorption parameters were also used to derive Gibbs free energy (ΔG):

| (2) |

Where R is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol*K), T is the temperature (absolute temperature, K), and Ke values were calculated from isothermal analyses conducted at 3 temperatures (2 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C).

These parameters were also used to estimate enthalpy (ΔH) using the Van’t Hoff equation:

| (3) |

For adsorption systems, a |ΔH| ≤ 25 kJ/mol suggests that physical mechanisms contribute to the adsorption process, and a |ΔH| ≥ 25 kJ/mol suggests a chemical adsorption processes [23]. Calculated ΔG and ΔH values from Eqs. 2 and 3 were used to estimate entropy (ΔS, kJ/mol) using the Gibbs function:

| (4) |

Where a ΔS > 0 suggests an irreversible adsorption process that causes an increase in disorder at the sorbent surface [56]. A ΔS < 0 suggests that no structural modifications occur on the sorbent’s surface during the adsorption process [56].

2.6. Time Course and Kinetics

Time course and kinetic experiments were conducted to investigate the effectiveness of the SFM composite materials to adsorb and retain benzene. For these studies, vials containing SFMs were injected with 15 μL of benzene and left to incubate for up to 24 h. At defined time intervals (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h), benzene was extracted and quantified using methods described above. The data were fit to the pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich kinetic models to quantify the adsorption rate. The pseudo-first order equation is defined as [3]:

| (5) |

Where qe (g/kg) and qt (g/kg) are the amounts of benzene adsorbed at equilibrium and at time t (hours), respectively. K (hours−1) is the first-order reaction rate constant. The pseudo-second order equation is defined as:

| (6) |

Where qe (g/kg) and qt (g/kg) are the amounts of benzene adsorbed at equilibrium and time t (hours), respectively. K2 (g/kg-hours) is the second-order reaction rate constant. The Elovich equation is defined as:

| (7) |

Where qt (g/kg) is the amount of benzene adsorbed at time t (hours). a is the initial adsorption rate (g/kg-hours) and b is correlated with the surface coverage and activation energy for chemical adsorption of adsorbate molecules (g/kg). The kinetic parameters were derived by using a software to minimize the squared deviation of the experimental and model-predicted values.

2.7. Sorbent characterization: XPS, SAXS, surface area, hydrophobicity, and photostability

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted using an OmicronESCA+ with an Mg X-ray source, emission current of 20 mA, and a voltage of 15KV. Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FTIIR) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were conduced using previous methods [70]. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was conducted on a Rigaju S-MAX-3000 where CuKa X-rays were generated at a current of 30 mA and voltage of 40 kV. Spectra were converted to plots using the SAXSGUI software. The MATSAS program was used to analyze the data [53].

Surface area of the sorbent materials was measured using the ethylene glycol monoethyl ether method (EGME) [11]. Briefly, 0.5 g of oven dried sorbents were mixed with 2 mL of EGME and placed in a desiccator containing 100 g of CaCl2. The desiccator was evacuated for 45 min, then the samples were left to equilibrate for 24 h. Afterwards, the samples were weighed and placed back in the desiccator. The desiccator was re-evacuated for 50 min, and then the samples were left to sit under vacuum pressure for 6 h before being weighed again. At the 30-hour time point, the samples were weighed again. Preliminary studies using additional evacuation and incubation steps indicated that the weight of the samples remained constant (within ± 2.5% of the 30-hour weight). Therefore, the 30-hour timepoint was used to calculate the surface area (As) of sorbents using the following equation:

| (8) |

Where WEGME is the amount of EGME retained by the sorbent (g), WS is the dry weight of the sorbent (g), and 2.86E-4 (m2/g) is the conversion factor for the approximated weight of EGME needed to create a mono-layer coverage [11].

The hydrophobicity of the SFMs was measured using established methods with modifications [54]. SFMs with 5% (w/w) sorbent material were dried in an oven at 100 °C for 24 h then weighed. The filters were hung in VOA vials that contained 4 mL of n-heptane or 4 mL of water for 24 h at ambient conditions. After incubation, SFMs were carefully removed from the jar and weighed to determine the uptake of n-heptane or water vapor. Hydrophobicity values were calculated from the ratio of n-heptane/water vapor uptake.

The photostability and influence of light exposure on adsorption performance was assessed using previously established methods [54] with modifications. SFM composites were placed under a 60-watt bulb at a 30 cm distance for 96 h. At 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of light exposure, SFMs were removed from the light and placed in the VOA vial. 15 μL of benzene was injected into each vial, and the filters were left to incubate for 4 h at ambient conditions. After 4 h, the filters were removed and the benzene was extracted and quantified.

2.8. Molecular simulations

Two layers of CM were modeled using CHARMM-GUI [10,14,32,37] with a composition of (Si4)IV(Al1.67Mg0.33)VI O10(OH)2, dimensions of 50 * 50 Å2, Miller indices 001, and a ratio of defect of 0.33333 as in [54]. Particular hydrogens and hydroxyl groups were manually removed from the clay edges from the provided structure of CHARMM-GUI to model the systems at neutral conditions (pH 7), based on neutral conditions provided by INTERFACE FF [26]. The two clay layers were separated with a d001 spacing of 21 Å [22,49,67–69]. Na(I) ions were removed and replaced with 40 Ca(II) ions, corresponding to the dimensions of the clay layers used. INTERFACE FF [26] was used for CM parameterization. In all clay simulations, Al/Mg were lightly contrained, as in [54]. We investigated two clay models, with the former including all 40 Ca(II) ions bound to the surface of the clay aiming to study the contribution of Ca(II) ions in benzene binding, while the latter did not include any Ca(II) ions. The two models were chosen to effectively model the upper and lower bounds on how Ca(II) ions could contribute to the binding of benzene in air.

CHARMM-GUI [10,14,32,37] was also used to model one layer of a carbon graphene sheet consisting of 350 carbon rings, with two variations of percent defect imposed on the modeled carbon: 1% and 20% (AC1 and AC20, respectively). Different activated carbon models were considered to account for the various number of defects that can be found in activated carbon, aiming at modeling a relatively small (AC1) and large (AC20) number of defects, both of which can be present in activated carbon [76]. Both AC1 and AC20 are considered as various possible AC models in the analysis to provide an overall analysis on activated carbon, and parametrization was taken from CHARMM in conjunction with CHARMM-GUI [10,14,32,37,62].

Chlorophyll-amended systems were initially constructed by simulating the aforementioned clay (absence and presence of Ca(II) ions), AC1, and AC20 material structures with 12 chlorophyll molecules dispersed in a 90 Å3 water box, independently. The structure of chlorophyll was extracted from PDB [8,51], and parameterized using a combination of CGENFF [62] parameters and published charges for the chlorin ring [24] as in [54]. Simulations were set up using CHARMM-GUI [10,14,32,37] input files and modified to incorporate the additional molecules included. The systems were equilibrated for 200 ps in CHARMM [10] under NVT conditions, and were simulated using OPENMM [17] for 10 ns at 300 K and 1 atm under NPT conditions with an isotropic barostat. The amended material-chlorophyll structures at the end of the simulation for each material were extracted and used for corresponding chlorophyll-amended materials in subsequent simulations.

Benzene molecules (24) were introduced into a 200 Å3 simulation box in complex with the extracted chlorophyll-amended materials and the parent material for their respective systems. Input files were retrieved from CHARMM-GUI [10,14,30,32,37], with input files being specified to run in vacuum to approximate the experimental conditions ran in air, and were adjusted to include the benzene and chlorophyll molecules in addition to the materials. Nonbonded interactions were smoothly switched off at 10–12 Å with a force-switch function. The temperature was maintained at 300 K using Langevin dynamics with a friction coefficient of 60 ps−1. Prior to performing simulations, the system’s energy was minimized with 400 steps of steepest descent and 400 steps of adopted basis Newton-Raphson then production was performed for 300 ns. Snapshots of simulation were obtained and visualized using VMD [30].

In-house FORTRAN programs were used to identify interactions of the benzene molecules in complex with the various sorbent material systems simulated. An interaction was considered to be any atom-atom distance ≤ 3.5 Å. The overall binding of benzene was tracked throughout the simulation and differentiated between binding modes, including direct, direct-Ca(II), direct-chlorophyll, direct-chlorophyll-Ca (II), and indirect binding. Direct binding was defined as a benzene molecule solely interacting with the material, while direct-Ca(II) binding was defined as benzene interacting with both the material and a Ca (II) ion. Direct-chlorophyll binding was defined as benzene interacting with both the material and bound chlorophyll molecule, while direct-chlorophyll-Ca(II) binding was considered to be benzene interacting with the material, a boundchlorophyll molecule, and Ca(II) ion simultaneously. Finally, indirect binding was defined as a benzene molecule solely binding to chlorophyll molecule. Additionally, we decomposed the chlorophyll into a core region, including the chlorin ring and two subsequent carbons, and a tail region, including the remaining atoms in the aliphatic chain, to track benzene-chlorophyll interactions [54].

2.9. Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test was used to determine statistical significance, which was achieved at p ≤ 0.05. Blank and benzene standard controls were included in every experiment. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and values were used to derive averages, standard deviations or standard errors, and create graphical representations of the data.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Method development

The extraction of benzene from a similar FM was previously described and developed [33], but some details of the extraction protocol (temperature, extraction vessel description and efficiency) of this method were missing. To optimize this method, the extraction protocol was conducted with selected eluotropic solvents with increasing ionic strength (ethanol, chloroform, cyclohexane, hexane, and n-heptane) to increase extraction percentages (Komsta et al., 2017) (Supplemental Table 1). Benzene is miscible with all tested solvents, and the detection method by HPLC showed high sensitivity (< 0.05 mg/L) (r2 > 0.99) for benzene in all solvents. In addition to testing the effect of solvent on extraction efficiency, the effect of temperature, mixing, and solvent volume were also investigated (Supplemental Fig. 1). Results indicated that extractions conducted at lower temperatures, with mixing, and high volume (40 mL) of all organic solvents yielded higher extraction efficiencies. Recovery percentage was positively correlated with eluotropic strength, where n-heptane showed the highest recovery of all solvents. Recovery of benzene in n-heptane at the optimal conditions (2 °C with mixing) was 93.1 ± 0.693%, compared to 71.9 ± 1.29% from ethanol in the same conditions (p < 0.01). Therefore, this modified method was used to extract benzene from our FM and SFMs to determine adsorption performance in the following experiments.

3.2. Adsorption isotherms and thermodynamics

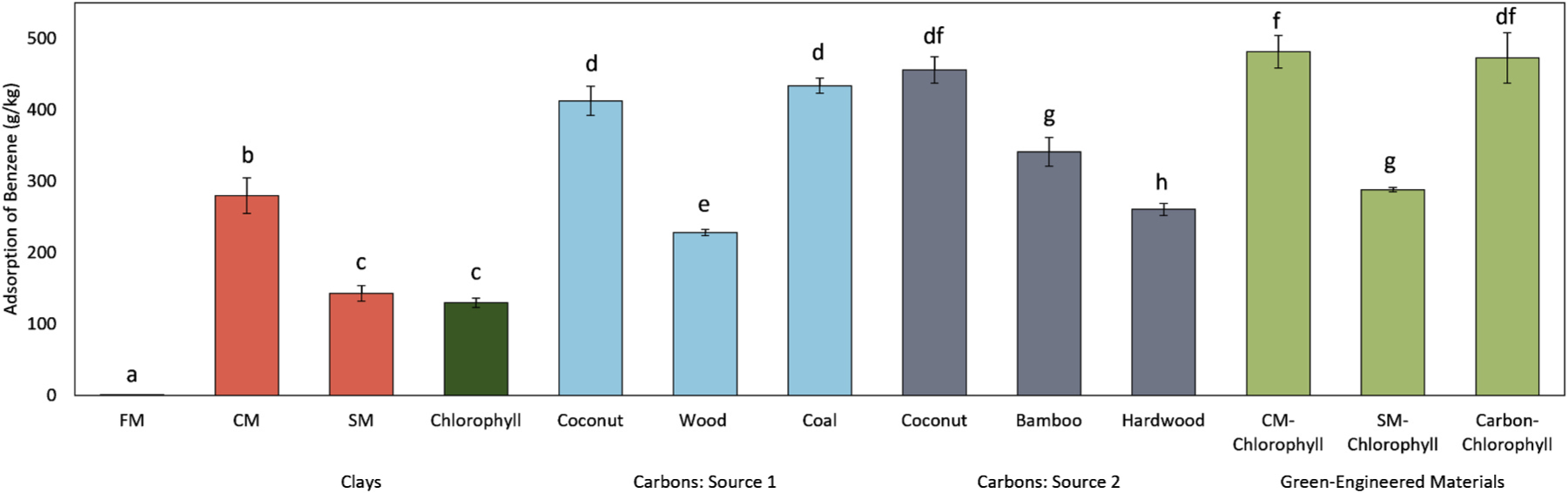

Modifying the surface of FMs with sorbent material has been previously shown to aid in the adsorption of VOCs like benzene [33,64]. Our results also indicated that the FM alone had negligible ability to bind benzene (0.92 ± 0.045 g/kg) compared to SFM composites containing embedded active sorbent materials (Fig. 1). Base clay materials like montmorillonite and zeolite have been previously used in air purification materials for benzene [44], and our results indicated that these materials have variable ability to sequester benzene from air. For montmorillonites, CM had a higher ability to bind benzene compared to SM (280 g/kg vs 143 g/kg, p < 0.001). This may be due to the fact that SM has more exchangeable sodium ions and is more hydrophilic due to intrinsic water-swelling properties, which may repel benzene and other lipophilic chemicals [66]. Interestingly, chlorophyll alone showed the lowest level of benzene adsorption (130 ± 6.4 g/kg), suggesting that chlorophyll may need a stabilizing base (like montmorillonite) to create a more effective sorbent for benzene.

Fig. 1.

Adsorption of benzene (g/kg) by the base FM and SFMs containing diverse types of clays, carbons, and green-engineered sorbents. SFMs containing embedded clays showed increased adsorption of benzene, and coconut-shell derived activated carbon and green-engineered sorbents showed the highest adsorption. Data is shown as an average of benzene adsorption from triplicate analyses ± standard deviation (n = 3). Bars with different letters indicate a significant difference between groups (p ≤ 0.05).

Activated carbons are a common amendment to air purification materials [44], and our results demonstrate that these materials have higher capacities for binding benzene compared to unmodified clay materials. The binding capacity varies among different types of activated carbons for benzene (Fig. 1), which was likely due to the different source materials and activation methods used to generate the products [46,65]. In general, the carbons derived from coconut shell and coal performed the best (> 400 g/kg). Previous studies have also demonstrated that activated carbons derived from these sources have higher adsorption capacities for benzene compared to other types of activated carbon, which could be due to high surface areas and the presence of micropores that enhance overall adsorption [77,78].

Importantly, activated carbons and clays can be modified with organic molecules, such as chlorophylls, to enhance their performance, compared to their parent materials. For example, SFM composite with CM-chlorophyll embedded had a 1.7 and 3.7 fold increase in benzene adsorption compared to the SFM composites with CM or chlorophyll alone, respectively (p < 0.05). The carbon-chlorophyll SFM showed similar results as CM-chlorophyll SFM (473 g/kg vs 481 g/kg, p = 0.74), which was only a 1.04 fold increase in adsorption compared to activated carbon SFM (p = 0.50).

Several materials were chosen for further adsorption analysis using isothermal and thermodynamic techniques, including the base FM and SFM composites loaded with activated carbon, CM, chlorophyll (Fig. 2A), carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll (Fig. 2B). The isothermal adsorption data were plotted based on the Freundlich model, which was the model that had the best fit to the experimental data (r2 >0.86) (Table 1). Similar to the capacity results, the base FM material showed a negligible binding of benzene and a low Kf value (9.04 ± 1.6). SFMs containing activated carbon showed an increased affinity for benzene (Kf = 472 ± 54.3) and high heterogeneity of binding sites (n = 3.78 ± 0.847). The two green-engineered materials (carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll) performed very similarly to one another and had the highest binding parameters for benzene, where the Kf values were 932 ± 57.6 and 922 ± 42.2, respectively (p = 0.82). The binding affinity of the CM-chlorophyll was significantly higher than the sum of its base materials (CM and chlorophyll) (p < 0.05). However, the carbon-chlorophyll only performed slightly better than its activated carbon-base material (source 1: coconut). These results suggest the chlorophyll and base material (CM or activated carbon) worked synergistically to enhance the overall adsorption. Adsorption isotherms of these materials at 2 °C and 37 °C are depicted in Supplemental Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Adsorption isotherm plots of benzene onto the base FM and the SFM loaded with activated carbon, calcium montmorillonite, and chlorophyll (A). The inset displays the negligible adsorption of benzene by the base FM. Adsorption isotherm plots of SFM loaded with green-engineered materials, i.e., carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll (B). All isotherms were plotted based on the Freundlich model using an average of adsorption from experimental results run in triplicate (n = 3) (g/kg) (solid shapes), and 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines) and the lines of best fit (solid lines) generated from curve fitting software. Both green-engineered materials similarly showed the best adsorption performance with higher Kf values compared to the other individual materials.

Table 1.

Summary of isothermal and thermodynamic parameters from the Freundlich adsorption model.

| T (°C) | Material Type | Kf | n | ΔG (kJ/mol) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (dJ/mol) | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | FM | 9.04 ± 1.6a | 1.09 ± 0.13a | −5.41 ± 0.26a | −5.57 ± 0.61a | 0.11 ± 0.06a | 0.952 |

| Activated Carbon | 472 ± 31.8b | 3.78 ± 0.85b | −15.2 ± 0.10b | −20.2 ± 3.14b | −1.68 ± 0.33bd | 0.867 | |

| CM | 262 ± 31.8c | 0.940 ± 0.07a | −13.7 ± 0.17c | −16.0 ± 3.37b | −0.95 ± 0.36b | 0.955 | |

| Chlorophyll | 387 ± 75.1bc | 0.745 ± 0.13a | −14.7 ± 0.28b | −8.34 ± 0.91a | 2.13 ± 0.10c | 0.937 | |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 932 ± 57.6d | 1.86 ± 0.12bc | −16.9 ± 0.09d | −25.2 ± 3.92b | −1.31 ± 0.20d | 0.949 | |

| CM-chlorophyll | 922 ± 42.2d | 1.87 ± 0.09bc | −16.8 ± 0.07d | −20.7 ± 1.95b | −2.79 ± 0.41b | 0.975 | |

| 2 | FM | 67.7 ± 10.6a | 0.903 ± 0.16a | −9.62 ± 0.21a | - | 1.36 ± 0.07a | 0.936 |

| Activated Carbon | 736 ± 55.6b | 8.05 ± 1.0b | −15.1 ± 0.10b | - | −1.71 ± 0.33b | 0.760 | |

| CM | 300 ± 14.9c | 2.09 ± 0.20 cd | −13.0 ± 0.07c | - | −1.01 ± 0.35b | 0.906 | |

| Chlorophyll | 459 ± 33.7d | 1.77 ± 0.22c | −14.0 ± 0.10d | - | 1.90 ± 0.10c | 0.974 | |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 726 ± 59b | 3.12 ± 0.38d | −15.1 ± 0.11b | - | −2.92 ± 0.41d | 0.934 | |

| CM-chlorophyll | 1360 ± 298b | 1.53 ± 0.31ac | −16.5 ± 0.29e | - | −1.88 ± 0.20b | 0.900 | |

| 37 | FM | 18.9 ± 5.7a | 0.994 ± 0.30ad | −7.49 ± 0.46a | - | 0.64 ± 0.09a | 0.938 |

| Activated Carbon | 367 ± 48.2bc | 6.34 ± 1.36b | −15.2 ± 0.20b | - | −1.68 ± 0.33b | 0.801 | |

| CM | 260 ± 6.63b | 0.816 ± 0.14ac | −14.3 ± 0.04c | - | −0.57 ± 0.35c | 0.936 | |

| Chlorophyll | 309 ± 19.9b | 0.756 ± 0.05a | −14.8 ± 0.10d | - | 2.17 ± 0.10d | 0.991 | |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 486 ± 43.6c | 2.13 ± 0.45d | −15.9 ± 0.13b | - | −3.12 ± 0.41b | 0.949 | |

| CM-chlorophyll | 327 ± 53.7bc | 3.63 ± 1.00bcd | −14.9 ± 0.25e | - | −1.95 ± 0.20e | 0.840 |

T: temperature, Kf: Freundlich constant, n: degree of heterogeneity, ΔG: Gibbs free energy, ΔH: enthalpy, ΔS: entropy, r2: coefficient of determination. Data is an average of triplicate analyses ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate a significant difference between groups in the same column at the same temperature (p < 0.05).

Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) were derived for each material from adsorption experiments conducted at increasing temperatures (2 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C) (Table 1). All materials tested had negative ΔG values at all temperatures, which indicated a spontaneous adsorption process for benzene onto all materials. However, the SFMs containing carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll had the lowest ΔG values (≤ −16.8 kJ/mol) out of all the tested materials at room temperature. Additionally, the |ΔH| values for each SFM were ≤ 25 kJ/mol, which indicated the adsorption process occurred through physical processes, like Van der Waals forces and aromatic interactions [23]. Except for the chlorophyll SFM, the SFMs generally had a small and negative value of ΔS. This suggested that the adsorption at the surfaces may occur through a mechanism that does not alter the structure of the sorbent material, and benzene molecules may be ordered at the sorbent surface [55,56]. Combined with the good fit to the Freundlich adsorption model, these experiments indicated that the adsorption of benzene to each SFM likely occurred through physical interactions, creating a multilayer of benzene held to the heterogenous binding sites. This result is consistent with our previous studies that the adsorption of benzene to CM-chlorophyll in water involves physical mechanisms [54,70].

The humidity, CO2, and temperature of the air in the experimental vessel were quantified. For adsorption isotherms conducted at ambient conditions on the benchtop, the room air (at a temperature of 25.9 at 25.9 ± 0.6 °C) contained 20% O2, 449 ± 9.7 ppm CO2 and 45.3 ± 1.5% humidity, which is aligned with normal ranges of O2 (approximately 21%), CO2 (400 ppm) and humidity (40–60%) [4,60]. Therefore, the adsorption performance of the tested materials under these conditions is directly relevant to indoor environments. For adsorption experiments conducted at low temperatures (2.57 ± 0.8 °C), the CO2 levels did not change (442 ± 7.7 ppm) compared to the room temperature experiments, but the relative humidity increased significantly to 75.3 ± 2.5%. For experiments at high temperatures (36.8 ± 0.6 °C), the CO2 level was consistent with the other environments (439 ± 7.8 ppm), but the relative humidity was lower (25.2 ± 1.1%).

In general, Kf values were the highest for all SFMs when conducted under low temperatures (2 °C) and high humidity (75%), which is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that adsorption efficiency was significantly related to temperature and humidity [13,27,31]. Results listed in Table 1 indicate that the binding performance of the activated carbon SFM was more susceptible to changes in temperature and humidity than SFMs containing CM, carbon-chlorophyll, and CM-chlorophyll. This may be due to the competion between benzene and water vapor for binding sites on activated carbon [40].

3.3. Kinetic studies

To investigate the optimal duration for binding and retaining benzene, FM and SFM systems were tested over a 24-hour period for benzene uptake (Fig. 3). The adsorption of benzene onto all materials fit a curved line that reached a saturated plateau within 30 mins of reaction time indicating maximum adsorption and quick reaction (Fig. 3A). The highest adsorption of benzene was achieved by the carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll composites (Fig. 3B), and adsorption maximum was sustained for several hours compared to the base materials. Desorption of benzene from the filter material was quantified by comparing the adsorption performance after 24 h of incubation (qt-24) with the calculated equilibrium level of benzene (qe). Desorption of benzene from the FM material at the end of the time-course studies was 73.9 ± 6.7%, compared to a 39.8 ± 7.6% and 31.4 ± 3.2% desorption rate observed from the carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll composites, respectively. These desorption rates are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated sorbents modified with chlorophyll had significantly lower desorption rates compared to their base materials [54].

Fig. 3.

Adsorption (g/kg) of benzene by the base FM, and SFMs loaded with activated carbon, CM, chlorophyll (A), carbon-chlorophyll, and CM-chlorophyll (B) over 24 h. Data is represented as an average adsorption (g/kg, solid shapes) ± standard deviation and a fitted line (solid line) (n = 3).

Quantifying kinetic and equilibrium parameters is important for understanding the mechanism and rate-determining step for adsorption [2]. The time course studies described above were analyzed using 3 standard, non-linear kinetic models: the pseudo 1st-order, pseudo 2nd-order, and the Elovich equations. To determine the model of best fit, the coefficient of determination (r2) and the comparison between the experimental adsorption capacity (qe, expected) and the model-derived capacity (qe, calculated) were used. Based on these criteria, the experimental data showed the best fit to the pseudo 2nd-order model, indicated by high (r2) (> 0.85) and similarity between the experimental and calculated qe values. The pseudo 2nd-order model parameters derived from the experimental data are summarized in Table 2. These results suggested the adsorption mechanism depends on diffusion processes and can be influenced by the presence and availability of heterogenous binding sites, pore size, and the partitioning of benzene on the sorbent’s surface [29].

Table 2.

Summary of experimental and calculated parameters from the non-linear pseudo 2nd-order kinetic model.

| Material Type | qe (expected) (g/kg) | qe (calculated) (g/kg) | K2 | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | 8.94 (± 0.1)a | 11.3 (± 5.2)a | 0.015 | > 0.725 |

| Activated Carbon | 258 (± 2.0)b | 220 (± 2.5)b | 0.016 | > 0.997 |

| CM | 264 (± 1.5)b | 191 (± 7.3)bc | 0.026 | > 0.988 |

| Chlorophyll | 198 (± 2.0)c | 168 (± 4.5)c | 0.016 | > 0.964 |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 394 (± 6.0)d | 276 (± 1.5)d | 0.007 | > 0.990 |

| CM-chlorophyll | 392 (± 8.0)d | 270 (± 14.0)d | 0.010 | > 0.993 |

qe (expected): experimental adsorption capacity, qe (calculated): model-derived adsorption capacity, K2: pseudo 2nd-order kinetic model rate constant (g/kg-hour), and r2: coefficient of determination. Data is an average of triplicate analyses ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate a significant difference between groups in the same column (p ≤ 0.05).

3.4. Sorbent characterization: XPS, SAXS, surface area, hydrophobicity, photostability

The varying performance of the SFMs is likely due to several physiochemical properties of the embedded sorbent material, including elemental composition, pore size distribution, surface area, and hydrophobicity [9,47]. The elemental composition of carbons and clay minerals is known to be primarily C, N, O, Si, Al, and Mg [12,57]; therefore, the quantity of these elements in the SFMs were investigated (Table 3). The composition of all materials was 82–92% C and O, but carbon-based materials contained more C than clay-based materials. The levels of C, N, and O in the activated carbon and carbon-chlorophyll were consistent with other activated carbons [74]. After modification with chlorophyll, the relative abundance of C in the activated carbon decreased, while O and N increased. This was likely due to the presence of these hetero-atoms in chlorophyll that was attached to the sorbent surface. For example, carbon-chlorophyll had approximately 3.2x more N, and 1.6x more O than the activated carbon, which could account for the 13% loss in C content.

Table 3.

Relative abundance of select elements in the sorbents in SFMs measured by XPS.

| Material Type | C (%) | N (%) | O (%) | Si (%) | Ca (%) | Al (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon | 73.3 | 0.485 | 18.6 | 2.35 | 1.85 | - |

| CM | 53.5 | - | 28.8 | 13.1 | 1.19 | 3.47 |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 60.6 | 1.53 | 30.4 | 3.37 | 2.19 | - |

| CM-chlorophyll | 58.0 | - | 31.4 | 7.52 | 0.581 | 2.46 |

For the clay materials (CM and CM-chlorophyll), the ratios of Si:Al were within the typical range for montmorillonite clays (3–4:1) [57]. CM-chlorophyll had a 49% decrease in Ca ions compared to CM, which suggested the ion exchange process of Ca for chlorophyll was successful [57]. Complete ion exchange may not have been achieved due to the large size of chlorophyll, which hinders its ability to enter the interlayer space to replace all Ca ions [54]. Taken together with the FTIR and SEM data of these sorbents (Supplemental Fig. 4) [70] these results suggest the successful intercalation of chlorophyll onto activated carbon and CM surfaces.

In general, activated carbons have the highest levels of microporosity, which is dependent on the source material, activation method, and other processing methods [52]. Compared to all the other sorbents, the activated carbon showed the highest pore volume (Fig. 4A and Table 4) and pore area (Fig. 4B). The majority of the pores were less than 5 nm. The pore volume and average diameter of activated carbon were in accordance with previous studies [52,75]. While the average pore diameter remained the same, the overall pore volume and area were decreased in the carbon-chlorophyll sorbent, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating amended materials have lower pore volume and surface area than their parent materials [25]. Clay minerals, like CM, are known to have fewer micropores and overall porosity than activated carbons, as demonstrated by the pore volume of 0.134 cm3/g and average pore size of 41 nm (Table 4). Similar to carbon-chlorophyll, CM-chlorophyll had lower surface area and porosity measurements compared to CM. These porosity values for CM and the CM-chlorophyll are similar to published values for CM and a modified CM [25].

Fig. 4.

Differential pore volume (A) and pore area (B) distribution of sorbents loaded onto SFMs, measured by SAXS.

Table 4.

Surface area and pore characteristics measured for sorbent materials loaded onto SFMs.

| Material Type | Surface area (m2/g) | Total Pore volume (cm3/g) | Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon | 1290 | 1.31 | 12.6 |

| CM | 719 | 0.134 | 41 |

| Carbon-chlorophyll | 860 | 0.546 | 12.6 |

| CM-chlorophyll | 404 | 0.069 | 34.6 |

Surface area and hydrophobicity are important factors for the efficiency of air purification materials, and materials with increased surface area have an improved ability to capture contaminants [41]. Additionally, hydrophobic materials have a tendency to repel moisture, aerosol droplets, and microorganisms [43,48] and have an increased ability to bind lipophilic contaminants, like benzene [45]. To further understand the contributions of these properties to the binding performance of our materials, the embedded sorbent materials were characterized for their surface area (Fig. 5A) and hydrophobicity (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Surface area (m2/g) of the sorbents in SFMs (A). Increased hydrophobicity, measured by the ratio of n-heptane/water adsorption for green-engineered sorbents compared to their base materials (B) (n = 3). Bars with different letters indicate a significant difference between groups (p ≤ 0.05).

Despite different source materials, activated carbons are known to have relatively high surface area values (950–2500 m2/g) [28] compared to other types of sorbents. Our results also demonstrate that the surface areas of the coconut-shell activated carbon and carbon-chlorophyll were higher than the clay materials tested, which is due to increased porosity and smaller particle size of carbons. Interestingly, the surface areas of our green-engineered materials were 35% lower than the surface areas of their respective base materials. This suggested that the addition of chlorophyll may take up macropores in base materials as well as forming aggregates on the surfaces as suggested by our previous SEM images [70]. However, the carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll composites demonstrated higher binding efficiencies for benzene compared to carbon and CM. This result suggests that the presence of surface modifications may reduce total sorbent surface areas while increasing the effective binding sites for benzene [54]. Therefore, the surface area of modified materials may not be directly related to binding efficiency. The surface areas measured were also in accordance with the values projected by the SAXS studies (Table 4).

Many natural clay minerals like CM are hydrophilic, and activated carbons are known to be relatively hydrophobic. Both of these materials can be modified with organic molecules like chlorophyll to make hydrophobic sorbents (organoclays and organocarbons). Chlorophylls are a class of large, organic molecules with high lipophilicity, and the addition of these molecules to the surfaces of clays or carbon significantly altered the hydrophobicity of the materials. Specifically, the addition of chlorophyll to carbon and CM increased the hydrophobicity by 1.4 and 6.5 fold, respectively (Fig. 5B). The increased lipophilicity of these green-engineered sorbents compared to the base materials may contribute to an increased ability to bind benzene and other lipophilic chemicals.

Chlorophyll molecules are known to be light-sensitive [63], but previous studies demonstrated that the photostability of chlorophyll was greatly improved by anchoring the molecules onto montmorillonite surfaces [54]. To test the influence of light exposure on the adsorption performance, the base FM and the SFMs containing various types of sorbent materials were placed under a light for 96 h and tested for their adsorption performance (Fig. 6). The FM and SFM loaded with CM had a 2.6 ± 2.1% and 11.7 ± 0.75% decrease in binding, respectively (Fig. 6A). This minimal change in performance confirms their stability and lack of photosensitive functionalities. After constant exposure under light for 96 h, composites containing chlorophyll had a 25.3 ± 3.0% decrease in adsorption performance after light exposure, and the carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll had a 23.9 ± 4.4% and 29.5 ± 2.9% decrease, respectively (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The influence of light exposure on the adsorption performance of the base FM and FMs loaded with activated carbon, CM, chlorophyll (A), and carbon-chlorophyll, and CM-chlorophyll (B). Sorbents containing chlorophyll show limited reduction in binding performance after 96 h of light exposure. The degradation pathway of chlorophyll exposed to light results in several different compounds (C).

The loss of adsorption performance may be related to the photodegradation of chlorophyll into products that may have less affinity for binding benzene (Fig. 6C). For example, chlorophyll first loses the central magnesium ion or phytol tail [63] after light exposure. Because these moieties are known to be important for coordination and aromatic stacking interactions [63], the loss of these functional groups may contribute to the reduced sorption efficacy for benzene observed by materials containing free or amended chlorophyll. However, the adsorption performance of the carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll materials after 96 h of light exposure were still greater than that of the other FM and SFMs filters without light exposure, indicating that these green-engineered materials are effective in reducing levels of benzene in air.

Additionally, the average life of most personal mask filters, air filter cartridges, and other air purification technologies ranges from < 1 day to 1 week, depending on the user preferences and severity of air pollution [6]. Therefore, the effect of photodegradation of the chlorophyll in disposable green-engineered filters is minimal for VOC removal. These materials could be useful during short-term emergencies to reduce exposures to benzene in contaminated air.

3.5. Molecular Simulations

In parent clays, moderate (approx. 30%) binding of benzene molecules was observed in the absence of Ca(II) ions (Fig. 7A and Fig. 8), but binding was increased in the presence of Ca(II) ions (Fig. 7B and Fig. 8) due to the high tendency of clay-bound Ca(II) ions to attract benzene molecules through cation-π interactions. In chlorophyll-amended clays simulated in the absence of Ca(II) ions, the binding of benzene was increased compared to parent clays (Fig. 8), primarily due to indirect interactions with chlorophyll molecules compared to direct-chlorophyll interactions (Fig. 7C). In chlorophyll-amended clays simulated in the absence of Ca(II) ions, the binding of benzene molecules was significantly increased compared to unamended clays in the absence of Ca(II). This could be attributed to chlorophyll bound molecules attracting benzene molecules which are primarily bound to chlorophyll molecules only, referred to as indirect binding, (Figs. 7A and C). In chlorophyll-amended clays simulated in the presence of Ca(II) ions, the binding of benzene molecules was slightly increased compared to the case of absence of Ca(II) ions (Fig. 6). This could be attributed to the fact that, similarly to the case of parent clays in the presence of Ca(II) ions, a significant portion of binding was due to benzene attracted to bound Ca (II) ions (Figs. 7B and D). Additionally, a small portion of the overall binding percentage was due to benzene molecules interacting with both bound Ca(II) ions and bound chlorophyll molecules simultaneously (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Simulation snapshots of benzene binding in parent clay system without (A) and with (B) Ca(II) ions, chlorophyll-amended clay without (C) and with (D) Ca(II) ions, carbon (1% defect) (E), carbon (20% defect) (F), Carbon-Chlorophyll (1% defect) (G), and Carbon-Chlorophyll (20% defect) (H). Clay and benzene are shown in van der Waals representation, carbon is shown in ochre licorice representation, and chlorophyll is shown in green licorice representation. Various binding modes are zoomed in and in circles.

Fig. 8.

Overall binding percentage broken down into various binding modes. Dark blue represents direct binding to the material with light blue represents direct binding to the material while interacting with a Ca(II) ion, grey represents direct binding to the material while interacting with a Ca(II) ion and a chlorophyll molecule, turqiouse represents direct binding while interacting with a chlorophyll molecule, and green color represents indirect binding through a chlorophyll molecule.

In carbon with a smaller percent defect (AC1) (Fig. 7E), we observed moderate binding of benzene molecules (approx. 35%) which was increased (approx. 40%) in carbon with a higher percent defect (AC20) (Fig. 7F and Fig. 8). This slight increase in overall binding may be due to the presence of pores in carbons with higher defect (Fig. 8F) that may promote interactions between sorbed benzene molecules and the sorbent surface [50]. In the presence of chlorophyll-amendments, binding of benzene was increased for AC1 (Fig. 7G), whereas binding was slightly decreased for AC20 (Fig. 7H and Fig. 8). The presence of chlorophyll molecules enhanced benzene binding in AC1. It is important to note that in both AC1 and AC20, chlorophyll-bound molecules contributed to the binding of benzene, either directly or indirectly, and affected the modes of binding compared to absence of chlorphyll (Fig. 8). Benzene molecules tended to interact both through direct and indirect chlorophyll interactions, but the direct interactions were the more predominant binding mode. Additionally, the predicted binding performance from these computational studies correlated well with the above in vitro experiments, where chlorophyll significantly enhanced benzene binding onto clays, while binding onto carbon-chlorophyll was only slightly improved. The similar performance of the CM-chlorophyll and carbon-chlorophyll systems was also shown in the simulation.

Interestingly, we observed similar benzene-chlorophyll interactions between the different variations of material systems considered in this study and across the two different material systems (clay and carbon material systems). Regardless of Ca(II) ions, benzene interacted with the core of a directly or indirectly clay-bound chlorophyll by 60.64 ± 5.97% and 68.12 ± 1.74%, respectively. Benzene also interacted with the aliphatic tail of bound chlorophylls directly or indirectly by 20.57 ± 4.14% and 18.26 ± 2.94%, respectively. In the remaining cases, benzene interacted with both the core and the tail of chlorophyll. For both AC systems with chlorophyll, benzene interacted with the core of a bound chlorophyll directly or indirectly 53.10 ± 4.36% or 55.30 ± 8.00% of the time, respectively. Benzene also interacted with the tail of bound chlorophylls directly or indirectly by 26.43 ± 1.77%, and 25.52 ± 6.23%, respectively. These results demonstrated the importance of the chlorophyll amendment, primarily for the CM systems, to promote binding interactions. These binding mechanisms are in accordance with our previous studies that demonstrated chlorophyll enhances the adsorption of benzene in water through cation-π, aliphatic-π, and π-π interactions [54].

4. Conclusions

In the current study, we developed novel composites by embedding clay- and carbon-based sorbent materials on the surfaces of a common nanofiber filter material to enhance the adsorption of benzene. We quantified the ability of these composite systems to remove benzene from air using in vitro analytical chemistry techniques and in silico computational modeling. The in vitro experiments indicated that the binding of benzene from air was the highest by green-engineered materials, like carbon-chlorophyll and CM-chlorophyll, and coconut-shell derived activated carbon. While the initial binding performance of all of these SFM composites was similar, the green-engineered materials demonstrated significantly increased adsorption affinities, spontaneous free energies of adsorption, and lower rates of desorption compared to the base nanofiber materials and other SFMs containing activated carbon and chlorophyll alone. Thermodynamic investigations indicated that physical mechanisms contributed to the overall adsorption, which was also supported by in silico molecular simulations. Kinetic studies suggested the adsorption of benzene followed the pseudo 2nd-order model for all filter systems where the adsorption rate was likely limited by diffusion-related processes and availability of heterogenous binding sites. The results of the in vitro and computational studies were highly supportive of each other, demonstrating the importance of using both methodologies to comprehensively understand the adsorption reaction. The combined results demonstrated that these novel materials can be useful for mitigating harmful exposures to benzene from polluted air. Based on the SFMs’ ability to bind benzene from air and previous studies indicated favorable adsorption of BTX (benzene, toluene, and xylenes) from water [70], we anticipate that these green-engineered materials will be effective for capturing structurally-similar aromatic hydrocarbons from air.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Superfund Hazardous Substance Research and Training Program (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) [P42 ES027704] and the United States Department of Agriculture [Hatch 6215].

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Phillips Timothy: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Wang Meichen: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Tamamis Phanourios: Funding acquisition, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Rivenbark Kelly J.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Lilly Kendall: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jece.2023.111836.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Adgate JL, Church TR, Ryan AD, Ramachandran G, Fredrickson AL, Stock TH, Morandi MT, Sexton K, Outdoor, indoor, and personal exposure to VOCs in children, Environ. Health Perspect 112 (14) (2004) 1386–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Agbovi HK and Wilson LD (2021) Natural Polymers-Based Green Adsorbents for Water Treatment, pp. 1–51, Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Andreoli E, Cullum L, Barron AR, Carbon dioxide absorption by polyethylenimine-functionalized nanocarbons: a kinetic study, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 54 (3) (2015) 878–889. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Asif A, Zeeshan M, Jahanzaib M, Indoor temperature, relative humidity and CO2 levels assessment in academic buildings with different heating, ventilation and air-onditioning systems, Build. Environ 133 (2018) 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bahrami A, Mahjub H, Sadeghian M, Golbabaei F, Determination of benzene, toluene and xylene (BTX) concentrations in air using HPLC developed method compared to gas chromatography, Int. J. Occup. Hyg 3 (2011) 1. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Balanay JAG, Oh J, Adsorption characteristics of activated carbon fibers in respirator cartridges for toluene, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (16) (2021) 8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barros N, Carvalho M, Silva C, Fontes T, Prata JC, Sousa A, Manso MC, Environmental and biological monitoring of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (BTEX) exposure in residents living near gas stations, J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 82 (9) (2019) 550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE, The protein data bank, Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1) (2000) 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bose S, Kumar PS, Rangasamy G, Prasannamedha G, Kanmani S, A review on the applicability of adsorption techniques for remediation of recalcitrant pesticides, Chemosphere (2022) 137481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brooks BR, Brooks III CL, Mackerell AD Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program, J. Comput. Chem 30 (10) (2009) 1545–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cerato AB, Lutenegger AJ, Determination of surface area of fine-grained soils by the ethylene glycol monoethyl ether (EGME) method, Geotech. Test. J 25 (3) (2002) 315–321. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen Y, Zi F, Hu X, Yang P, Ma Y, Cheng H, Wang Q, Qin X, Liu Y, Chen S, The use of new modified activated carbon in thiosulfate solution: a green gold recovery technology, Sep. Purif. Technol 230 (2020) 115834. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chiang Y-C, Chiang P-C, Huang C-P, Effects of pore structure and temperature on VOC adsorption on activated carbon, Carbon 39 (4) (2001) 523–534. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Choi YK, Kern NR, Kim S, Kanhaiya K, Afshar Y, Jeon SH, Jo S, Brooks BR, Lee J, Tadmor EB, CHARMM-GUI nanomaterial modeler for modeling and simulation of nanomaterial systems, J. Chem. Theory Comput 18 (1) (2021) 479–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Deng L, Yuan P, Liu D, Annabi-Bergaya F, Zhou J, Chen F, Liu Z, Effects of microstructure of clay minerals, montmorillonite, kaolinite and halloysite, on their benzene adsorption behaviors, Appl. Clay Sci 143 (2017) 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Desta MB, Batch sorption experiments: langmuir and Freundlich isotherm studies for the adsorption of textile metal ions onto teff straw (Eragrostis tef) agricultural waste, J. Thermodyn 2013 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [17].Eastman P, Friedrichs MS, Chodera JD, Radmer RJ, Bruns CM, Ku JP, Beauchamp KA, Lane TJ, Wang L-P, Shukla D, OpenMM 4: a reusable, extensible, hardware independent library for high performance molecular simulation, J. Chem. Theory Comput 9 (1) (2013) 461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vasu A. Edwin, Surface modification of activated carbon for enhancement of nickel (II) adsorption, E-J. Chem 5 (4) (2008) 814–819. [Google Scholar]

- [19].EPA 2022. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations.

- [20].Gong J 2020. RShiny.

- [21].Gonzalez-Martin J, Kraakman NJR, Perez C, Lebrero R, Munoz R, A state–of–the-art review on indoor air pollution and strategies for indoor air pollution control, Chemosphere 262 (2021) 128376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Greenland D and Quirk J (1962) Clays and Clay Minerals, pp. 484–499, Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gu B, Schmitt J, Chen Z, Liang L, McCarthy JF, Adsorption and desorption of natural organic matter on iron oxide: mechanisms and models, Environ. Sci. Technol 28 (1) (1994) 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Guerra F, Adam S, Bondar A-N, Revised force-field parameters for chlorophyll-a, pheophytin-a and plastoquinone-9, J. Mol. Graph. Model 58 (2015) 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].He H, Zhou Q, Martens WN, Kloprogge TJ, Yuan P, Xi Y, Zhu J, Frost RL, Microstructure of HDTMA+-modified montmorillonite and its influence on sorption characteristics, Clays Clay Miner. 54 (6) (2006) 689–696. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heinz H, Lin T-J, Kishore Mishra R, Emami FS, Thermodynamically consistent force fields for the assembly of inorganic, organic, and biological nanostructures: the INTERFACE force field, Langmuir 29 (6) (2013) 1754–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Horsfall Jnr M, Spiff AI, Effects of temperature on the sorption of Pb2+ and Cd2+ from aqueous solution by Caladium bicolor (Wild Cocoyam) biomass, Electron. J. Biotechnol 8 (2) (2005) 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hu Z, Srinivasan M, Mesoporous high-surface-area activated carbon, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 43 (3) (2001) 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hubbe MA, Azizian S, Douven S, Implications of apparent pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetics onto cellulosic materials: a review, BioResources 14 (3) (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [30].Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K, VMD: visual molecular dynamics, J. Mol. Graph 14 (1) (1996) 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Isinkaralar K, Improving the adsorption performance of non-polar benzene vapor by using lignin-based activated carbon, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res (2023) 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W, CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM, J. Comput. Chem 29 (11) (2008) 1859–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kadam V, Kyratzis IL, Truong YB, Wang L, Padhye R, Air filter media functionalized with β-Cyclodextrin for efficient adsorption of volatile organic compounds, J. Appl. Polym. Sci 137 (40) (2020) 49228. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kadam V, Truong YB, Schutz J, Kyratzis IL, Padhye R, Wang L, Gelatin/β–cyclodextrin bio–nanofibers as respiratory filter media for filtration of aerosols and volatile organic compounds at low air resistance, J. Hazard. Mater 403 (2021) 123841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Komsta Ł, Stępkowska B and Skibiński R, The experimental design approach to eluotropic strength of 20 solvents in thin-layer chromatography on silica gel, J. Chromatogr. A 1483 (2017) 138–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lai H, Jantunen M, Künzli N, Kulinskaya E, Colvile R, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Determinants of indoor benzene in Europe, Atmos. Environ 41 (39) (2007) 9128–9135. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee J, Cheng X, Jo S, MacKerell AD, Klauda JB, Im W, CHARMM-GUI input generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field, Biophys. J 110 (3) (2016) 641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li S, Lin Y, Liu G and Shi C 2023. Research status of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) removal technology and prospect of new strategies: A review. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li S, Song K, Zhao D, Rugarabamu JR, Diao R, Gu Y, Molecular simulation of benzene adsorption on different activated carbon under different temperatures, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 302 (2020) 110220. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li Z, Jin Y, Chen T, Tang F, Cai J, Ma J, Trimethylchlorosilane modified activated carbon for the adsorption of VOCs at high humidity, Sep. Purif. Technol 272 (2021) 118659. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liu C, Hsu P-C, Lee H-W, Ye M, Zheng G, Liu N, Li W, Cui Y, Transparent air filter for high-efficiency PM2 5 capture, Nat. Commun 6 (1) (2015) 6205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lu Y, Li Y, Liu D, Ning Y, Yang S, Yang Z, Adsorption of benzene vapor on natural silicate clay minerals under different moisture contents and binary mineral mixtures, Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp 585 (2020) 124072. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mazhar SI, Shafi HZ, Shah A, Asma M, Gul S, Raffi M, Synthesis of surface modified hydrophobic PTFE-ZnO electrospun nanofibrous mats for removal of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from air, J. Polym. Res 27 (2020) 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mobasser S, Wager Y, Dittrich TM, Indoor air purification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using activated, Carbon Zeolite Organo Sorbents Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 61 (20) (2022) 6791–6801. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Moyo F, Tandlich R, Wilhelmi BS, Balaz S, Sorption of hydrophobic organic compounds on natural sorbents and organoclays from aqueous and non-aqueous solutions: a mini-review, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11 (5) (2014) 5020–5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Oh J-Y, You Y-W, Park J, Hong J-S, Heo I, Lee C-H, Suh J-K, Adsorption characteristics of benzene on resin-based activated carbon under humid conditions, J. Ind. Eng. Chem 71 (2019) 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Olivares-Marín M, Cuerda-Correa E, Nieto-Sánchez A, Garcia S, Pevida C, Román S, Influence of morphology, porosity and crystal structure of CaCO3 precursors on the CO2 capture performance of CaO-derived sorbents, Chem. Eng. J 217 (2013) 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ontiveros CC, Shoults DC, MacIsaac S, Rauch KD, Sweeney CL, Stoddart AK, Gagnon GA, Specificity of UV-C LED disinfection efficacy for three N95 respirators, Sci. Rep 11 (1) (2021) 15350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Orr AA, He S, Wang M, Goodall A, Hearon SE, Phillips TD, Tamamis P, Insights into the interactions of bisphenol and phthalate compounds with unamended and carnitine-amended montmorillonite clays, Comput. Chem. Eng 143 (2020) 107063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Park J, Hung I, Gan Z, Rojas OJ, Lim KH, Park S, Activated carbon from biochar: influence of its physicochemical properties on the sorption characteristics of phenanthrene, Bioresour. Technol 149 (2013) 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].PDB, P.D.B. 2022 Chlorophyll A CLA.

- [52].Prehal C, Grätz S, Krüner B, Thommes M, Borchardt L, Presser V, Paris O, Comparing pore structure models of nanoporous carbons obtained from small angle X-ray scattering and gas adsorption, Carbon 152 (2019) 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rezaeyan A, Pipich V, Busch A, MATSAS: a small-angle scattering computing tool for porous systems, J. Appl. Crystallogr 54 (2) (2021) 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rivenbark KJ, Wang M, Lilly K, Tamamis P, Phillips TD, Development and characterization of chlorophyll-amended montmorillonite clays for the adsorption and detoxification of benzene, Water Res. 221 (2022) 118788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Saha P, Chowdhury S, Insight into adsorption thermodynamics, Thermodynamics 16 (2011) 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sahmoune MN, Evaluation of thermodynamic parameters for adsorption of heavy metals by green adsorbents, Environ. Chem. Lett 17 (2) (2019) 697–704. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schampera B, Solc R, Woche S, Mikutta R, Dultz S, Guggenberger G, Tunega D, Surface structure of organoclays as examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations, Clay Miner. 50 (3) (2015) 353–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sharma SB, Jain S, Khirwadkar P, Kulkarni S, The effects of air pollution on the environment and human health, Indian J. Res. Pharm. Biotechnol 1 (3) (2013) 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shi G, He S, Chen G, Ruan C, Ma Y, Chen Q, Jin X, Liu X, He C, Du C, Crayfish shell-based micro-mesoporous activated carbon: insight into preparation and gaseous benzene adsorption mechanism, Chem. Eng. J 428 (2022) 131148. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shi X, Xiao H, Azarabadi H, Song J, Wu X, Chen X, Lackner KS, Sorbents for the direct capture of CO2 from ambient air, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 59 (18) (2020) 6984–7006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Srikrishnarka P, Kumar V, Ahuja T, Subramanian V, Selvam AK, Bose P, Jenifer SK, Mahendranath A, Ganayee MA, Nagarajan R, Enhanced capture of particulate matter by molecularly charged electrospun nanofibers, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 8 (21) (2020) 7762–7773. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields, J. Comput. Chem 31 (4) (2010) 671–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Verduin J, Den Uijl M, Peters R, Van Bommel M, Photodegradation products and their analysis in food, J. Food Sci. Nutr 6 (67.10) (2020) 24966. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Verma VK, Subbiah S, Kota SH, Sericin-coated polyester based air-filter for removal of particulate matter and volatile organic compounds (BTEX) from indoor air, Chemosphere 237 (2019) 124462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Vikrant K, Na C-J, Younis SA, Kim K-H, Kumar S, Evidence for superiority of conventional adsorbents in the sorptive removal of gaseous benzene under real-world conditions: test of activated carbon against novel metal-organic frameworks, J. Clean. Prod 235 (2019) 1090–1102. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang M, Hearon SE, Phillips TD, A high capacity bentonite clay for the sorption of aflatoxins, Food Addit. Contam.: Part A 37 (2) (2020) 332–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wang M, Maki CR, Deng Y, Tian Y, Phillips TD, Development of high capacity enterosorbents for aflatoxin B1 and other hazardous chemicals, Chem. Res. Toxicol 30 (9) (2017) 1694–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wang M, Orr AA, He S, Dalaijamts C, Chiu WA, Tamamis P, Phillips TD, Montmorillonites can tightly bind glyphosate and paraquat reducing toxin exposures and toxicity, ACS Omega 4 (18) (2019) 17702–17713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wang M, Orr AA, Jakubowski JM, Bird KE, Casey CM, Hearon SE, Tamamis P, Phillips TD, Enhanced adsorption of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) by edible, nutrient-amended montmorillonite clays, Water Res. 188 (2021) 116534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wang M, Phillips TD, Green-engineered barrier creams with montmorillonite-chlorophyll clays as adsorbents for benzene, toluene, and xylene, Separations 10 (4) (2023) 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].WHO (2010) WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants, World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].WHO 2016. Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease.

- [73].WHO 2017. Burden of disease from household air pollution for 2012.

- [74].Yagmur E, Gokce Y, Tekin S, Semerci NI, Aktas Z, Characteristics and comparison of activated carbons prepared from oleaster (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) fruit using KOH and ZnCl2, Fuel 267 (2020) 117232. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Yalçın N, Sevinc V, Studies of the surface area and porosity of activated carbons prepared from rice husks, Carbon 38 (14) (2000) 1943–1945. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Yang P-Y, Ju S-P, Huang S-M, Predicted structural and mechanical properties of activated carbon by molecular simulation, Comput. Mater. Sci 143 (2018) 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Zhang R, Li Z, Wang X, Wang F, Zeng L, Li Z, Adsorption equilibrium of activated carbon amid fluctuating benzene concentration in indoor environments, Build. Environ (2023) 110964. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zhang R, Zeng L, Wang F, Li X, Li Z, Influence of pore volume and surface area on benzene adsorption capacity of activated carbons in indoor environments, Build. Environ 216 (2022) 109011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.