Abstract

A description of zebrafish posterior Lateral Line (pLL) primordium development at single cell resolution together with the dynamics of Wnt, FGF, Notch and chemokine signaling in this system has allowed us to develop a framework to understand the self-organization of cell fate, morphogenesis and migration during its early development. The pLL primordium migrates under the skin, from near the ear to the tip of the tail, periodically depositing neuromasts. Nascent neuromasts, or protoneuromasts, form sequentially within the migrating primordium, mature, and are deposited from its trailing end. Initially broad Wnt signaling inhibits protoneuromast formation. However, protoneuromasts form sequentially in response to FGF signaling, starting from the trailing end, in the wake of a progressively shrinking Wnt system. While proliferation adds to the number of cells, the migrating primordium progressively shrinks as its trailing cells stop moving and are deposited. As it shrinks, the length of the migrating primordium correlates with the length of the leading Wnt system. Based on these observations we show how measuring the rate at which the Wnt system shrinks, the proliferation rate, the initial size of the primordium, its speed, and a few additional parameters allows us to predict the pattern of neuromast formation and deposition by the migrating primordium in both wild-type and mutant contexts. While the mechanism that links the length of the leading Wnt system to that of the primordium remains unclear, we discuss how it might be determined by access to factors produced in the leading Wnt active zone that are required for collective migration of trailing cells. We conclude by reviewing how FGFs, produced in response to Wnt signaling in leading cells, help determine collective migration of trailing cells, while a polarized response to a self-generated chemokine gradient serves as an efficient mechanism to steer primordium migration along its relatively long journey.

Introduction

The Lateral Line is a sensory system that helps fish and aquatic amphibians detect the pattern of water flow over their body surface (Bleckmann and Zelick, 2009; Montgomery et al., 2000). It consists of sensory organs called neuromasts that are distributed over the body. Each neuromast contains a central cluster of sensory hair cells, surrounded by support cells that together form an epithelial rosette. Sensory hair cell progenitors divide to form sibling sensory hair cells that respond optimally to water flow in opposite directions (Rouse and Pickles, 1991). They are innervated by afferents in the Lateral Line nerve, which carry sensory information about the pattern of water flow to the brain via sensory neurons whose cell bodies are in the Lateral Line ganglion, located next to the ear (Faucherre et al., 2009; Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2007; Metcalfe et al., 1985). In this review we will describe how the posterior Lateral Line (pLL) primordium pioneers formation of posterior Lateral Line system and discuss how our current knowledge of interactions between its cells, primarily those mediated by the Wnt and FGF pathways, account for the pattern in which neuromasts are generated and deposited by the migrating primordium. We then use a simple computational model as a platform to integrate some of these ideas and explore whether the dynamics of the Wnt signaling system coupled with key measurements about migration speed, proliferation rate, and initial size of the primordium are adequate to make effective predictions about the pattern of neuromast formation and deposition. In the final part of the review we turn our attention more specifically to mechanisms that determine collective migration of the primordium and conclude by highlighting critical questions about these mechanisms that remain unanswered.

The posterior Lateral Line primordium

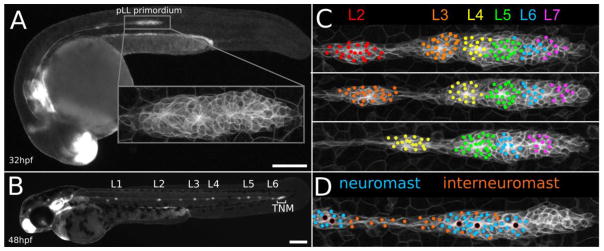

The pLL primordium in zebrafish is a group of approximately 140 cells that migrates caudally, under the skin, from near the ear to the tip of the tail (Gompel et al., 2001; Nogare et al., 2017). As it migrates, the pLL primordium periodically deposits neuromasts to pioneer formation of the posterior Lateral Line in zebrafish (Figure 1A). The pLL primordium pinches off caudally from the pLL placode, leaving behind cells that will form the pLL ganglion (Metcalfe, 1985). The cells of the pLL primordium remain associated with each other and together form a coherent column of cells that collectively migrates under the skin following a path defined by cells of the horizontal myoseptum. During this journey, cells within the migrating primordium sequentially reorganize to form nascent neuromasts or protoneuromasts (Gompel et al., 2001; Haas and Gilmour, 2006; Lecaudey et al., 2008; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). While leading cells are relatively flat and have a quasi-mesenchymal morphology, the trailing cells become taller as they acquire apical basal polarity. Then, starting at the trailing end of the primordium, cells constrict at their apical ends and reorganize to form epithelial rosettes within the migrating primordium. As the protoneuromasts take shape, a central cell within each protoneuromast becomes specified as a sensory hair cell progenitor (Chitnis et al., 2012; Itoh and Chitnis, 2001).

Figure 1.

Overview of pLL primordium migration and morphogenesis. A. 32hpf zebrafish embryo, showing position of the deposited L1 neuromast and the migrating pLL primordium. Inset shows a magnified view of an example pLL primordium. B. 48hpf zebrafish embryo showing neuromast spacing (L1–L6) after completion of migration, as well as the position of the future terminal neuromast cluster (TNM). C. Frames from a timelapse movie showing where cells that will make up the L2–L7 neuromasts reside in the pLL primordium. D. Frame from a timelapse movie showing the position of both deposited and prospective neuromast (blue) and interneuromast (orange) cells. Scale bar in A and C, 200μm.

As cells within the pLL primordium proliferate and the primordium transiently elongates, the most trailing cells slow down, stop migrating, and are eventually deposited; trailing cells that had been incorporated into protoneuromasts are deposited as neuromasts, while surrounding cells that had not, are deposited between neuromasts as so-called interneuromast cells (Grant et al., 2005; Lopez-Schier and Hudspeth, 2005). As the pace at which cells are deposited by the migrating primordium from its trailing end exceeds the rate at which they are added by proliferation, the primordium progressively shrinks (Gompel et al., 2001). The pLL primordium begins its journey at about 20–22 hours post fertilization (hpf) with about 140 cells. Over the next 24 hours as it migrates, the pLL primordium will add about 200 cells by proliferation, while depositing approximately 5–7 neuromasts and associated interneuromast cells before shrinking to about 30 cells and terminating near the tip of the tail by resolving into 2–3 terminal neuromasts (Figure 1B) (Gompel et al., 2001; Nogare et al., 2017).

A model for understanding self-organization of organ systems

The relative simplicity of the pLL primordium, our ability to monitor cell movement, morphogenesis and the activity of specific signaling systems in the migrating primordium with various transgenic lines, coupled with the ability to manipulate its development with a combination of molecular, cellular and genetic approaches has, in recent years, made the pLL primordium an attractive system to understand and model how interactions between cells determine the self-organization of organ systems during early development (Venero Galanternik et al., 2016). A number of studies, especially in the past decade, have now characterized the collective migration of cells and the morphogenesis and deposition of neuromasts by the migrating primordium (Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2004; Gompel et al., 2001; Haas and Gilmour, 2006; Revenu et al., 2014; Venero Galanternik et al., 2016). In addition, studies have described the fundamental role Wnt, FGF, Notch, and Chemokine signaling pathways play in coordinating cell fate, morphogenesis, collective cell migration, and the pattern in which neuromasts are formed and deposited by the migrating primordium (Aman and Piotrowski, 2009; Haas and Gilmour, 2006; Itoh and Chitnis, 2001; Lecaudey et al., 2008; Li et al., 2004; Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008; Sapede et al., 2005; Valentin et al., 2007). Together these studies have not only shed light on the development of the zebrafish lateral line system but analysis of these cellular interactions and signaling mechanisms in this relatively simple and well defined system provide general lessons about processes that have recurrent and conserved roles throughout development and the animal kingdom.

In toto analysis of primordium cell proliferation, fate and behavior

Given the relative simplicity of this model system, and building on earlier studies, we took advantage of data collected from high-resolution time-lapse imaging of the pLL primordium to track the division, lineage, fate and movement of every cell in the migrating primordium, starting from before the deposition of the first neuromast up to the time migration ends near the tip of the tail (Nogare et al., 2017). Several key descriptive insights emerged from this analysis. This study showed that cell division is only weakly patterned along the length of the primordium, with leading cells tending to divide slightly more slowly than trailing cells. In the context of this relatively unpatterned cell division across the primordium, neuromasts form sequentially, starting from the trailing end, as a consequence of local expansion of cell populations and incorporation of cells along the length of the migrating primordium into forming protoneuromasts. In this way, more trailing cells are incorporated into early-deposited neuromasts, while progressively more leading cells are incorporated into progressively later-deposited neuromasts (Figure 1C). On the other hand, their fate in terms of whether they contribute to formation of a neuromast or an interneuromast cell is determined somewhat stochastically, as a function of a cell’s distance from the center of a maturing protoneuromast (Figure 1D) (Nogare et al., 2017). Cells that are further away from the protoneuromast center are more likely to be deposited as interneuromast cells while cells that are closer tend to be deposited as part of the neuromast.

Wnt and FGF signaling coordinate sequential formation of protoneuromasts

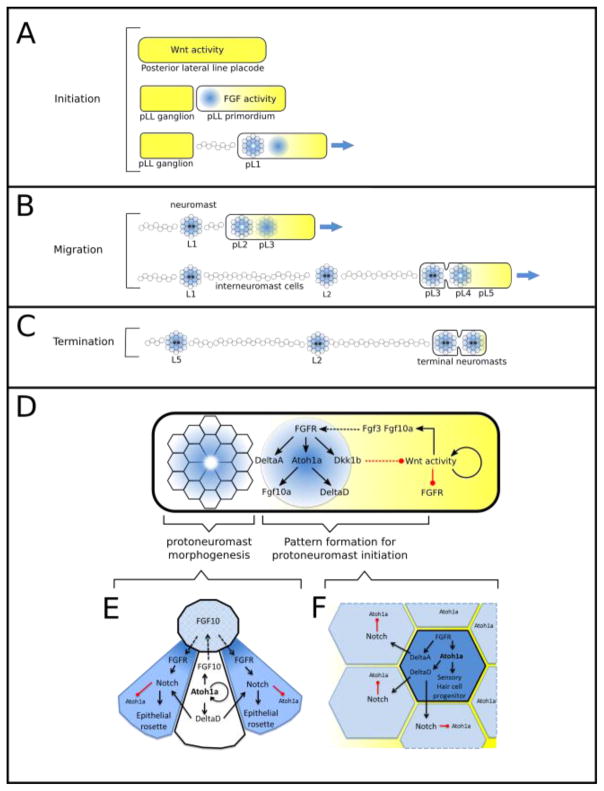

The pattern in which protoneuromasts sequentially form along the length of the primordium and by which cells adopt a neuromast or interneuromast fate can be best understood in the context of the role of Wnt and FGF signaling in coordinating cell fate and morphogenesis in the primordium (Figure 2). Initially, Wnt signaling dominates the entire posterior Lateral Line placode (Figure 2A, top), which contributes to formation of both the posterior Lateral Line ganglion and the primordium. Wnt signaling helps to locally maintain its own activity by driving expression of Wnt ligands like Wnt10a (Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015; Venero Galanternik et al., 2016) and effectors of Wnt signaling like Lef1 (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). At the same time Wnt signaling determines expression of two Fgf ligands, Fgf3 and Fgf10. However, cells producing Fgf3 and Fgf10 cannot respond effectively to these signals because Wnt signaling also determines expression of Sef and Dusp6 (Dual Specificity Phosphatase 6), which are factors that inhibit the Wnt active cells from responding to these Fgf signals (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Matsuda et al., 2013). These interactions are summarized in Figure 2D. Eventually an Fgf responsive signaling center is established at the trailing end of the prospective primordium, near its boundary with the prospective pLL ganglion (Figure 2A, middle)(Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008).

Figure 2.

Overview of Wnt and Fgf signaling in the morphogenesis of the pLL primordium. A. Initiation of pLL primordium migration. The pLL placode is initially dominated by Wnt activity (yellow). Subsequently, an FGF responsive center (blue) is established at the trailing end of the prospective pLL primordium. It initiates formation of the first protoneuromast. Additional FGF responsive centers and associated protoneuromasts form sequentially as migratory behavior is initiated. B. As the Wnt system shrinks so does the primordium. Cells incorporated into protoneuromasts are deposited as neuromasts while those that were not are deposited as interneuromast cells. C. Eventually, the Wnt system shrinks below some threshold and the primordium resolves to form terminal neuromasts after depositing 5–6 neuromasts. D. Schematic of signaling within the forming and mature protoneuromasts within the pLL primordium. E. Cross section through a mature protoneuromast showing the relationship between central Atoh1a-positive hair cell progenitor and surrounding cells. F. Detail of Fgf (shown in blue) and Notch/Delta signaling in early patterning of the neuromast.

Establishment of an Fgf signaling center sets the stage for coordinating the formation of a nascent neuromast or protoneuromast in the primordium (Lecaudey et al., 2008; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). Fgf signaling promotes changes in cell shape and organization that contribute to the reorganization of cells into an epithelial rosette. At the same time Fgf signaling initiates expression of atoh1a and deltaA, with their highest levels being initiated near the center of the prospective neuromast (Chitnis et al., 2012). While the transcription factor Atoh1a gives the cells in the forming protoneuromast the potential to be specified as sensory hair cell progenitors, Notch ligands, DeltaA and another Notch ligand, DeltaD, expressed in response to Atoh1a, activate Notch in neighboring cells to inhibit them from expressing atoh1a (Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010) (Figure 2F). As a consequence of this lateral inhibition mediated by Notch signaling, the highest levels of atoh1a expression remain restricted to the central cell in the forming protoneuromast, which allows it to be specified as a sensory hair cell progenitor.

From initiation to maturation of the protoneuromast

Once a sensory hair cell progenitor is specified at the center of the forming protoneuromast, expression of Atoh1a in this cell plays a key role in facilitating the effective maturation of a stable protoneuromast (Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene et al., 2017; Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010). Atoh1a not only continues to drive the expression of the Notch ligand DeltaD, as described above, it also drives the expression Fgf ligand fgf10, which makes the central cell a new source of Fgf10 that is independent of Wnt signaling. Fgf10 and DeltaD, expressed in the central sensory hair cell progenitor, activate, respectively, the FGF receptor and Notch in neighboring cells (Figure 2E). Activation of both Fgf and Notch signaling in the neighbors ensures morphogenesis of stable epithelial rosettes. As a result, proximity to the central source of Fgf and Notch ligands determines whether a cell in the primordium will be effectively incorporated into a neuromast when deposited or if it will be deposited as an interneuromast cell instead. Previous studies had suggested that Fgf10 and DeltaD signals act in parallel: Fgf10 activates Fgf signaling to determine effective incorporation of surrounding cells into stable epithelial rosettes, while DeltaD activates Notch signaling to prevent the neighbors from expressing Atoh1a (Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010). Recent studies suggest, however, that both lateral inhibition and morphogenesis of stable epithelial rosettes might be dependent on Notch signaling downstream of Fgf signaling (Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene et al., 2017). While Fgf10-dependent Fgf signaling maintains Notch receptor expression in the neighbors (Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010), DeltaD-mediated activation of Notch determines both effective maturation of epithelial rosettes (Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene et al., 2017) and lateral inhibition, which prevents the surrounding cells from expressing Atoh1a. While Kozlovskaja-Gumriene et al suggest that the Notch signaling pathway is essential for effective morphogenesis of epithelial rosettes downstream of Fgf signaling during the maturation of protoneuromasts, Fgf signaling has a Notch-independent role in determining expression of shroom3, which is likely to have an additional role in the initial morphogenesis of the epithelial rosettes (Ernst et al., 2012). Fgf3 and Fgf10, expressed in response to Wnt signaling in leading cells, initiate epithelial rosette formation and centrally biased Atoh1a expression in nascent protoneuromasts. However, effective maturation of the protoneuromasts at the trailing end of the primordium, as discussed above, depends on Fgf10, whose expression is no longer dependent on Wnt signaling but is instead now determined by Atoh1a, whose expression becomes self-sustaining in the sensory hair cell progenitor specified at the center of the maturing protoneuromast (Figure 2E). It is important to note that in this context, as the protoneuromast matures, the apical ends of its cells come together to form a microlumen in which Fgfs accumulate (Durdu et al., 2014). While the mechanisms that deliver Fgf to this apical microlumen remain poorly understood, it is thought that it is essential for determining effective Fgf signaling in surrounding cells of the epithelial rosette that come together to form the microlumen. Though some of the Fgf that accumulates in this microlumen may come from leading cells, the bulk of it is likely to come from the sensory hair cell progenitor at the center of the maturing protoneuromast that is now a source of Fgf10 (Figure 2E).

Sequential formation of protoneuromasts

In addition to initiating formation of nascent neuromasts, Fgf signaling determines expression of Dkk1b (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008), which inhibits Wnt signaling (Figure 2D). Dkk1b, and possibly additional factors, restrict the Wnt active domain to a smaller leading zone of the migrating primordium to facilitate the establishment of another Fgf signaling-dependent protoneuromast closer to the leading end of the primordium. In this manner, establishment of each protoneuromast shrinks the Wnt system and facilitates the formation of the next protoneuromast progressively closer to the leading end of the migrating primordium (Figure 2B). Eventually, the leading Wnt system is extinguished, migration stops and the remaining cells in the primordium resolve to form two to three terminal neuromasts (Valdivia et al., 2011) (Figure 2C).

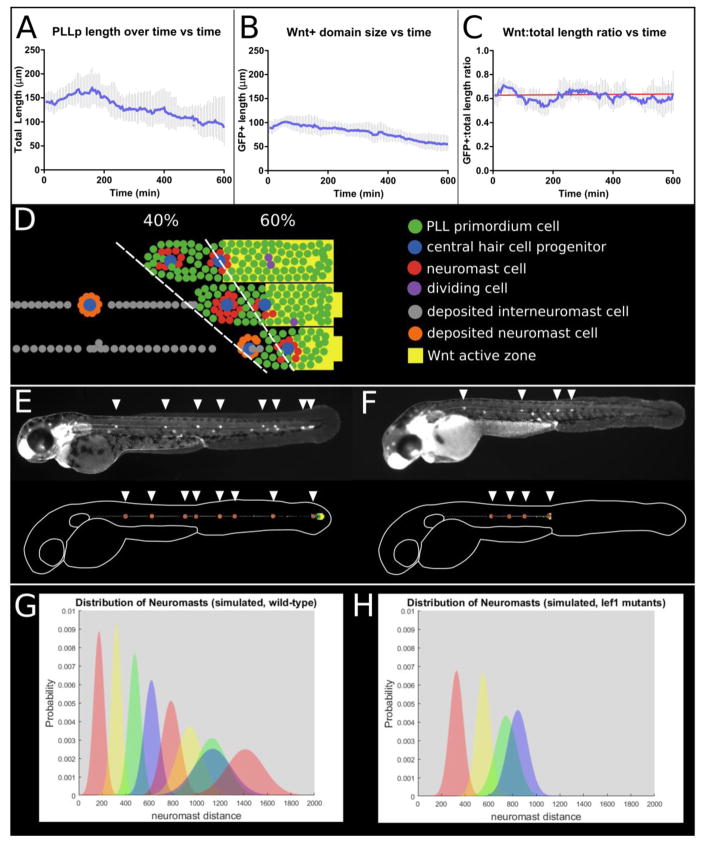

The Wnt system is 60% the length of the primordium

Interestingly, as the leading Wnt system shrinks, so does the primordium (Figure 3A, B). Time lapse imaging of a Wnt- reporter line in which cells with Lef1-dependent Wnt activity are green (Shimizu et al., 2012) showed that on average the length of the leading Wnt active domain is always 60% the length of the entire primordium (Fig. 3C). One interpretation of the correlation between the length of the leading Wnt sytem and length of the primordium is that Wnt active cells produce some “migratory” factor that determines the potential of primordium cells to remain cohesive and participate in collective migration (Valdivia et al., 2011). As proliferation elongates the primordium and the leading Wnt system shrinks, cells at the trailing end of the primordium have progressively less access to such a Wnt-dependent migratory factor, whose production remains restricted to the Wnt active domain at the leading end of the primordium. When access to this factor, required for collective migration, drops below some critical threshold, trailing cells stop migrating and are deposited; primordium cells that had been incorporated into protoneuromasts are deposited as neuromasts, while surrounding cells that were not incorporated into protoneuromasts, are deposited as interneuromast cells. In this manner, both the rate at which the primordium elongates as a consequence of cell proliferation (Aman et al., 2011) and the rate at which the leading Wnt system shrinks (Valdivia et al., 2011), determines the pace at which trailing cells loose access to factors produced by leading Wnt active cells that are required to maintain collective migration. Consequently, these parameters are likely to determine when trailing cells stop migrating and are deposited by the primordium.

Figure 3.

Modeling neuromast deposition patterns by the pLL primordium. A. Total length of the pLL primordium over time (averaged from n = 9 embryos). B. Length of the Wnt-active domain (as reported by the Tcf/Lef-miniP:dGFP reporter line). C. Ratio of Wnt-active domain length to total pLL primordium length. Red line indicates the best linear fit. D. Three frames from a model run showing the progressive shrinking of the Wnt-active zone together with the pLL primordium. E. Neuromast deposition pattern at 48hpf in wild-type ClaudinB:lynGFP embryos (top) and model results (scaled to the length of the embryo outline) for wild-type parameters. F. Neuromast deposition pattern at 48hpf in embryos injected with 2ng lef1 morpholino (top) and model results for lef1 morphant parameters (for details, see text and table S1). G. Quantification of the neuromast deposition pattern (mean and standard deviation) for n = 20 model runs using both wild-type (left) and lef1 (right) parameters.

As Wnt signaling inhibits Fgf signaling-dependent formation of protoneuromasts in the leading zone, the rate at which the Wnt system shrinks also determines the pace at which new Fgf signaling centers with associated protoneuromasts can form in the wake of the shrinking Wnt system (Matsuda et al., 2013). Together, these observations suggested that the rate at which the Wnt system shrinks and a few additional key parameters related to the speed, initial size of the primordium, rate of cell proliferation and the minimum distance between sequentially formed protoneuromasts should help us predict progressive changes in the size of the primordium and the pattern in which neuromasts are formed and deposited.

A model of neuromast formation and deposition by the migrating primordium

We built an agent-based model of the pLL primordium (for details see supplementary data) to visualize how these parameters could influence the pattern of neuromast formation and deposition. The simulations start at a stage when there is broad Wnt signaling (yellow background) in the primordium (green cells) and there are no protoneuromasts (supplementary movie S1). Then as the Wnt system shrinks at a defined rate (5μm every 60 minutes, the average measured, though there was significant fluctuation in the measurements), protoneuromasts form sequentially starting from the trailing end (red cells) (Figure 3D). To mimic what happens in the embryo, primordium migration begins in the simulations only after the Wnt system has shrunk to less than 65% the length of the primordium and approximately 2–3 trailing neuromasts have formed. Unpatterned cell division is simulated in the primordium by assigning each cell a random cell cycle length so that together the cell cycles have a normal distribution, with an average of 539 minutes and a standard deviation of 127 minutes (Nogare et al 2017). Dividing cells can be visualized in the simulations along the entire length of the primordium as they momentarily adopt a purple color.

Simulation of sequential protoneuromast formation within the primordium

The simulations illustrate how unpatterned proliferation promotes lengthening of primordium. This, together with the shrinking of the Wnt system allows leading cells that were initially within a Wnt active zone (yellow), where protoneuromast formation was suppressed to emerge in a Wnt-free zone where they can contribute to formation of a new protoneuromast (see supplementary movie 1). In the simulations, a central cell, which emerges out of the Wnt zone and is at least a specified minimum distance (35μm) from the center of a previously formed protoneuromast, gets defined as the central cell (blue) of a new protoneuromast. This cell forms links with surrounding cells within a defined radius to simulate formation of a new protoneuromast (red cells).

Simulating the pattern of deposition from the trailing end of the primordium

As the length of the leading Wnt system in the migrating primordium is, on average, 60% the length of the primordium, the predicted length of the shrinking Wnt system was used to compute the length of the column of primordium cells that is permitted to continue migration in the simulations. At any given time, cells located in a trailing zone that exceeds the length of the primordium predicted by the length of the leading Wnt system, stop moving and are deposited. For practical reasons, cell movement in the original simulations is shown from the frame of reference of the primordium (supplementary movie 1), so the primordium appears stationary and cells that have been deposited from its trailing end, appear to move backwards. When trailing cells are deposited, cells that had been incorporated into protoneuromasts are deposited as neuromasts (orange), while those that were not are deposited as interneuromast cells (grey) (Figure 3D). The primordium “terminates” once the Wnt system shrinks below a size of about 30μm in the simulation.

Figure 3E compares predictions of the model with observations made in the embryo. The simulations predict a pattern of neuromast formation and deposition that is remarkably similar to what is observed in the embryo (Gompel et al., 2001; Nogare et al., 2017). However, there are a couple of important differences. The simulations predict the deposition of too many neuromasts (~8.5 in simulation versus ~6 in experiment) and a slightly shorter migration path (~1600μm in simulation versus ~2200μm in 48hpf embryos). Why the simulations predict, on average, deposition of a couple of extra neuromasts remains unclear at this time. It may be related to inaccurate information about the rate at which the Wnt system shrinks in the primordium close to the end of its journey and/or the manner in which the terminal neuromasts form. On the other hand, the shorter migration distance predicted by the simulations is more easily explained. It is related to stretching of the developing embryo, which distorts and increases the final distance of the terminal neuromasts from the ear, where migration starts. Estimates of embryo lengthening between 24 and 48hpf suggest a change in length of approximately 40% (from 2.06mm to 2.96mm) (Metcalfe, 1985), which could account for the observed difference of ~37% between model and experiment. In Figures 3E and F, the model results have been similarly stretched to scale to the length of the outlined embryo. The neuromasts have also been made larger for clarity, although their positions have not been altered.

Having compared the pattern of neuromast deposition in the simulations and in wild-type embryos, we used the model to visualize how the pattern of neuromast deposition changes in lef1 deficient embryos. Lef1 is a transcription factor that helps mediate a subset of Wnt β-catenin-dependent activities in the primordium and its Wnt signaling-dependent expression has been used to monitor the pattern of Wnt signaling in the primordium (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Shimizu et al., 2012; Valdivia et al., 2011). Following the deposition of the first two neuromasts at locations that are approximately similar to that in wild-type embryos, subsequent neuromasts are deposited closer to each other before the primordium terminates prematurely in lef1 deficient embryos (Matsuda et al., 2013; McGraw et al., 2011; Valdivia et al., 2011). These changes in the pattern of neuromast deposition are thought to arise as a consequence of the role of lef1 in determining both collective migration and proliferation in the primordium. The primordium migration speed progressively reduces in the lef1 deficient embryos, which contributes to the closer-spaced neuromasts (Matsuda et al., 2013). At the same time, loss of lef1 function reduces proliferation in the primordium. As a consequence the primordium begins migration with fewer cells and a smaller Wnt system (Gamba et al., 2010; Matsuda et al., 2013). While the Wnt system appears to shrink at the same pace, it reaches a minimum sooner, and the primordium terminates prematurely.

Though precise measurements of cell cycle length and reduced initial cell number were not available, these parameters were altered in the agent-based model to approximate changes in lef1 deficient embryos. As there was approximately half as much cell proliferation observed in lef1 mutant primordia (Matsuda et al., 2013) the average cell cycle length was doubled in the simulations. Likewise, the migration speed was progressively lowered as the simulation proceeded in order to simulate slowing of the lef1 mutant pLL primordium. The simulations illustrate how the model predicts similar changes in the pattern of neuromast deposition, with closer spaced neuromasts and premature termination, when the proliferation rate and migration speed are reduced (Figure 3G, H).

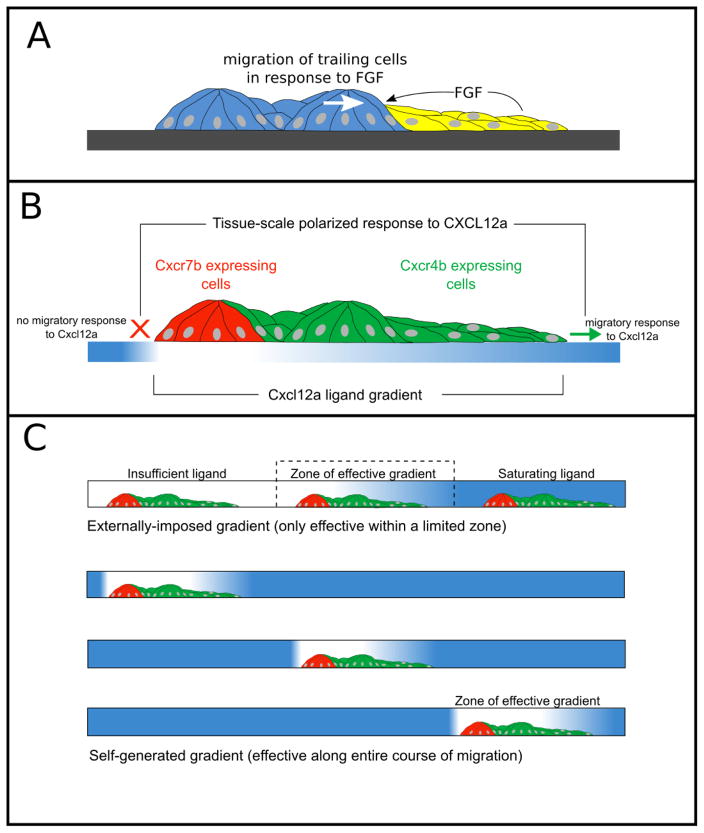

What Wnt-dependent factor determines the length of the migrating primordium?

The Wnt system is always, on average, 60% the length of the primordium. However, the actual mechanism that determines this relationship remains unclear at this time. It was suggested above that it could be related to a factor produced in leading Wnt active cells that is required for collective migration of the trailing cells and that, as access to such a migratory factor is lost by trailing cells, they stop moving and are deposited. Consistent with this possibility, Wnt signaling determines the expression of fgf3 and fgf10 in leading cells. These Fgfs not only activate signaling in trailing cells to determine sequential formation of protoneuromasts, their production by leading cells serves as a migratory cue for trailing cells (Figure 4A). Evidence for the role for Fgfs in determining collective migration of trailing cells came from an early observation that primordium cells stop migrating when Fgf signaling is inhibited (Lecaudey et al., 2008; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). More recently we showed that when a laser is used to cut and release a leading fragment of the primordium, Fgfs secreted by the leading fragment provide a migratory cue for cells in the trailing fragment, which moves toward the leading fragment (Dalle Nogare et al., 2014). In this context, the polarized movement of the trailing fragment is lost when Fgf signaling is inhibited or when the leading fragment is ablated. However, the polarized movement of the trailing fragment is restored when the ablated leading fragment is replaced with an Fgf soaked bead, supporting a role for Fgfs secreted by the leading zone in serving as a migratory cue for trailing cells.

Figure 4.

Schematic of guidance cues in pLL migration. A. Fgfs secreted by leading Wnt-active cells (yellow) can act as a directional cue for the migration of trailing cells. B. Polarized expression of Cxcr4b and Cxcr7b chemokine receptors in the pLL primordium. Cxcl12a gradient generated by ligand internalization is shown below in blue. Trailing, Cxcr7b-expressing cells are unable to respond to Cxcl12a, while leading cells expressing Cxcr4b are able to. C. Comparison of externally imposed gradient with a self-generated gradient on the migration of the pLL primordium. Blue represents the levels of Cxcl12 along the migratory path in each condition.

Unanswered questions about collective migration and mechanisms of deposition

Despite the strong evidence for Fgf signaling in determining collective migration of trailing cells, it has not actually been demonstrated that loss of access to Fgfs or any additional factors secreted by leading Wnt-active cells is actually what determines when trailing cells stop migrating and are deposited by the migrating primordium. If access to Fgfs, specifically produced by leading cells, were indeed a critical factor in determining collective migration of trailing cells, then it would still need to be explained why Fgf10, subsequently produced by the central hair cell progenitor in the maturing protoneuromasts, cannot sustain collective migration. In fact, it has been suggested that Fgf signaling, determined by the accumulation of Fgfs in the microlumen formed at the apical end of epithelial rosettes in protoneuromasts, is essential both for their effective maturation and eventually for their timely deposition. When this lumen is punctured by laser ablation the neuromast takes longer to deposit than control neuromasts at the same stage (Durdu et al., 2014). Fgf activates downstream effectors by the Ras/Raf-Mek MAPK, PI3K/AKT and the PLCγ/Ca2+ pathways (Ornitz and Itoh, 2015) and while there is the potential for significant cross talk between these three distinct pathways, the manner in which each of them contributes to migratory behavior in the primordium has not yet been defined. One possibility is that Fgf signaling, dependent on Fgfs accumulating in the apical microlumens to promote protoneuromast maturation and deposition (Durdu et al., 2014), operates by a mode that is distinct from that determined by Fgfs secreted by leading cells to promote collective migration.

Though Fgf signaling has been implicated in regulating the behavior of individual migratory cells in many other developmental contexts, it may contribute in additional ways to the collective migration of primordium cells, where cell-cell interactions and the mechanical coupling of leading and trailing cell migratory behavior is likely to play an important role. Previous studies have focused on the role of Fgf signaling in determining morphogenesis of epithelial rosettes in the primordium. It remains to be seen if changes in mechanical tension associated with sequential Fgf-dependent morphogenesis of epithelial rosettes contribute in some way to collective migration. Indeed answers to these questions will be essential to not only understand how distinct signaling systems contribute to collective migration but also to the mechanisms by which trailing cells are deposited by the migrating primordium.

The role of chemokine signaling in steering migration of the primordium

Changes in the trailing cells that accompany deposition from the primordium are also related to the expression of chemokine receptors that contribute to directed migration of leading cells that steer the migration of the PLL primordium. The primordium migrates along a path defined by the chemokine Cxcl12a, which is expressed by muscle pioneer cells along the horizontal myoseptum (David et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004). The directed migration of the primordium along this path is not defined by the graded expression of Cxcl12a along this path but rather by the polarized expression of two types of chemokine receptors, Cxcr4b and Cxcr7b, in leading and trailing cells of the primordium, respectively (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007; Haas and Gilmour, 2006; Valentin et al., 2007) (Figure 4B). Cells in the leading part of the primordium express cxcr4b, which encodes a chemokine receptor that binds Cxcl12a and responds to it via a G-protein coupled signaling mechanism to promote migratory behavior (Dumstrei et al., 2004). By contrast, Cxcr7b, expressed in trailing cells, binds even more effectively to Cxcl12a but its intracellular domain is different from that of Cxcr4b and it cannot determine migratory behavior of cells via a G-protein coupled signaling mechanism. Instead the bound Cxcl12a is internalized and degraded, while the Cxcr7b receptor is recycled back to the cell surface. This results in a local depletion of Cxcl12a (Boldajipour et al., 2008; Mahabaleshwar et al., 2012; Naumann et al., 2010). In this way, the polarized expression of Cxcr4b and Cxcr7b in leading and trailing cells, respectively, ensures directed migration of the primordium in two ways. First, at a tissue scale, it ensures a polarized response to the stripe of Cxcl12a encountered by the migrating primordium: While leading cells expressing Cxcr4b can respond to the Cxcl12a with migratory behavior, trailing cells expressing Cxcr7b cannot (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007; Valentin et al., 2007). Second, the internalization and degradation of Cxcl12a creates a local gradient of Cxcl12a at a tissue scale (Dona et al., 2013; Venkiteswaran et al., 2013), such that cells at the leading end of the primordium, which steer migration, always encounter higher levels of Cxcl12a than trailing cells.

It is important to recognize that robust unidirectional movement of the primordium results from both the polarized response of the primordium and the generation of a local gradient of Cxcl12a. Two very elegant studies have demonstrated that internalization of Cxcl12a by Cxcr7b expressing cells contributes to the generation of a local gradient of Cxcl12a along the length of the primordium (Dona et al., 2013; Venkiteswaran et al., 2013). However, the behavior of a leading fragment of the primordium, released from the rest of the primordium by a laser cut, suggests that it is unlikely that the gradient is adequate to determine polarized migration of leading cells on its own (Dalle Nogare et al., 2014). Unlike the primordium, which expresses Cxcr4b in leading cells and Cxcr7b in trailing cells, the leading fragment, released in these experiments by a laser cut, is unpolarized; It has no Cxcr7b and has chemokine-responsive Cxcr4b expressed at both ends. In this context, in spite of the laser cut leaving behind a trailing primordium fragment with Cxcr7b receptor expression and the potential to locally deplete Cxcl12a, the leading fragment moves bi-directionally, suggesting that the local gradient is not, on its own, capable of determining robust unidirectional migration of the leading fragment.

A broader role for self-generated chemoattractant gradients in long distance guidance

A chemoattractant gradient can effectively determine direction only if specific conditions are met: The cell or the group of cells being guided by the chemoattractant gradient should have a receptor system able to respond differentially to the concentration of the chemoattractant at its leading and trailing ends, the concentration at the leading end should be high enough to determine migration but not so high that it saturates the response of the receptors and determines a similar response at both the leading and trailing ends. These conditions impose limitations on the distance over which an externally imposed gradient, in which a locally produced chemoattractant diffuses to create a gradient, can guide migration. This issue has been very elegantly explored with agent-based modeling by Tweedy et al (Tweedy et al., 2016), where they show how shallow gradients generated by low source concentrations are too flat for cells to resolve while steep gradients, generated by high source concentrations, rapidly lead to saturation as cells climb the gradient (Figure 4C, top panel). Self-generated gradients are far less limited by these effects because relatively low concentration of attractant can be locally shaped into a perceptibly steep gradient by degradation (Figure 4C, lower panels). A comparison of the usefulness of externally-imposed and self-generated gradients as guidance cues over different distances by Tweedy et al suggests that while externally-imposed gradients may be effective over distances less than 1mm, self-generated chemotaxis can act over arbitrarily large distances and time. Self-generated gradients do, however, have some limitations. While an effective externally applied gradient can inform all cells in its field, self-generated gradients only effectively instruct cells that are within a front wave of migrating cells. In a large population of single migrating cells, depletion of the chemoattractant by cells in the leading front eventually makes the gradient ineffective for guiding trailing cells that are progressively left behind.

In the context of the advantages and disadvantages discussed above, it appears the pLL primordium has evolved to take advantage of the long-range guidance that is possible using a self-generated chemokine gradient, while collective migration helps it avoid the limitations of such gradients in providing effective guidance to trailing cells. The mechanical coupling of trailing cells to leading cells allows cells along the entire the primordium to move as a cohesive column, while chemokines effectively steer migration of leading cells. The length of the primordium ensures that depletion of chemokines through binding of receptors and subsequent degradation will determine a functionally significant difference in concentration of chemokine at leading and trailing ends. At the same time the polarized expression of Cxcr4b and Cxcr7b at leading and trailing ends of the primordium ensures a polarized response to the self-generated gradient.

Future directions

Sequential formation of protoneuromasts, the migration of the primordium and subsequent deposition of neuromasts and interneuromasts in the wake of a shrinking primordium has primarily been discussed in this review in the context of interactions between cells and the environment mediated by the Wnt, FGF, Notch and chemokine signaling pathways. However, these intercellular signaling systems coordinate morphogenesis and migration by regulating cytoskeletal mechanisms operating within the primordium cells and by dynamically regulating mechanical interactions between individual cells and the substrate on which they migrate. The manner in which intercellular signaling systems regulate cell biological systems and how they in turn ultimately determine cell morphogenesis and migration, remains an important question for future studies. The self-organization of the primordium can by understood from a framework where coupled yet mutually inhibitory Wnt and FGF signaling systems determine distinct patterns of morphogenesis in the leading and trailing domains of the primordium. In the same way, it remains to be seen how the cell biological mechanisms that determine mechanical coupling and collective migration in the leading part of the primordium are coupled to, yet potentially opposed by, the mechanisms that promote reorganization of the trailing cells into epithelial rosettes and their eventual deposition by the migrating primordium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD001012), NIH Bethesda MD. We thank members of the Chitnis lab for constructive discussions. Experiments described were performed under animal protocol #15-039.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aman A, Nguyen M, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin dependent cell proliferation underlies segmented lateral line morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2011;349:470–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Dev Cell. 2008;15:749–61. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Multiple signaling interactions coordinate collective cell migration of the posterior lateral line primordium. Cell Adh Migr. 2009;3:365–8. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.4.9548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleckmann H, Zelick R. Lateral line system of fish. Integr Zool. 2009;4:13–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2008.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldajipour B, Mahabaleshwar H, Kardash E, Reichman-Fried M, Blaser H, Minina S, Wilson D, Xu Q, Raz E. Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration. Cell. 2008;132:463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis AB, Nogare DD, Matsuda M. Building the posterior lateral line system in zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:234–55. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Nogare D, Somers K, Rao S, Matsuda M, Reichman-Fried M, Raz E, Chitnis AB. Leading and trailing cells cooperate in collective migration of the zebrafish posterior lateral line primordium. Development. 2014;141:3188–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.106690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C, Cubedo N, Ghysen A. Control of cell migration in the development of the posterior lateral line: antagonistic interactions between the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7/RDC1. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David NB, Sapede D, Saint-Etienne L, Thisse C, Thisse B, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Rosa FM, Ghysen A. Molecular basis of cell migration in the fish lateral line: role of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and of its ligand, SDF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16297–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252339399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dona E, Barry JD, Valentin G, Quirin C, Khmelinskii A, Kunze A, Durdu S, Newton LR, Fernandez-Minan A, Huber W, Knop M, Gilmour D. Directional tissue migration through a self-generated chemokine gradient. Nature. 2013;503:285–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumstrei K, Mennecke R, Raz E. Signaling pathways controlling primordial germ cell migration in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4787–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durdu S, Iskar M, Revenu C, Schieber N, Kunze A, Bork P, Schwab Y, Gilmour D. Luminal signalling links cell communication to tissue architecture during organogenesis. Nature. 2014;515:120–4. doi: 10.1038/nature13852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst S, Liu K, Agarwala S, Moratscheck N, Avci ME, Dalle Nogare D, Chitnis AB, Ronneberger O, Lecaudey V. Shroom3 is required downstream of FGF signalling to mediate proneuromast assembly in zebrafish. Development. 2012;139:4571–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.083253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucherre A, Pujol-Marti J, Kawakami K, Lopez-Schier H. Afferent neurons of the zebrafish lateral line are strict selectors of hair-cell orientation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba L, Cubedo N, Lutfalla G, Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. Lef1 controls patterning and proliferation in the posterior lateral line system of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:3163–71. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. Development of the zebrafish lateral line. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. The lateral line microcosmos. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2118–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.1568407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompel N, Cubedo N, Thisse C, Thisse B, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Ghysen A. Pattern formation in the lateral line of zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2001;105:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Raible DW, Piotrowski T. Regulation of latent sensory hair cell precursors by glia in the zebrafish lateral line. Neuron. 2005;45:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas P, Gilmour D. Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line. Dev Cell. 2006;10:673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Chitnis AB. Expression of proneural and neurogenic genes in the zebrafish lateral line primordium correlates with selection of hair cell fate in neuromasts. Mech Dev. 2001;102:263–6. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene A, Yi R, Alexander R, Aman A, Jiskra R, Nagelberg D, Knaut H, McClain M, Piotrowski T. Proliferation-independent regulation of organ size by Fgf/Notch signaling. Elife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecaudey V, Cakan-Akdogan G, Norton WH, Gilmour D. Dynamic Fgf signaling couples morphogenesis and migration in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development. 2008;135:2695–705. doi: 10.1242/dev.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Shirabe K, Kuwada JY. Chemokine signaling regulates sensory cell migration in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2004;269:123–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Schier H, Hudspeth AJ. Supernumerary neuromasts in the posterior lateral line of zebrafish lacking peripheral glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabaleshwar H, Tarbashevich K, Nowak M, Brand M, Raz E. beta-arrestin control of late endosomal sorting facilitates decoy receptor function and chemokine gradient formation. Development. 2012;139:2897–902. doi: 10.1242/dev.080408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, Chitnis AB. Atoh1a expression must be restricted by Notch signaling for effective morphogenesis of the posterior lateral line primordium in zebrafish. Development. 2010;137:3477–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.052761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, Nogare DD, Somers K, Martin K, Wang C, Chitnis AB. Lef1 regulates Dusp6 to influence neuromast formation and spacing in the zebrafish posterior lateral line primordium. Development. 2013;140:2387–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.091348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw HF, Drerup CM, Culbertson MD, Linbo T, Raible DW, Nechiporuk AV. Lef1 is required for progenitor cell identity in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development. 2011;138:3921–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe WK. Sensory neuron growth cones comigrate with posterior lateral line primordial cells in zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:218–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe WK, Kimmel CB, Schabtach E. Anatomy of the posterior lateral line system in young larvae of the zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 1985;233:377–89. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J, Carton G, Voigt R, Baker C, Diebel C. Sensory processing of water currents by fishes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355:1325–7. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann U, Cameroni E, Pruenster M, Mahabaleshwar H, Raz E, Zerwes HG, Rot A, Thelen M. CXCR7 functions as a scavenger for CXCL12 and CXCL11. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A, Raible DW. FGF-dependent mechanosensory organ patterning in zebrafish. Science. 2008;320:1774–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1156547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogare DD, Nikaido M, Somers K, Head J, Piotrowski T, Chitnis AB. In toto imaging of the migrating Zebrafish lateral line primordium at single cell resolution. Dev Biol. 2017;422:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:215–66. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenu C, Streichan S, Dona E, Lecaudey V, Hufnagel L, Gilmour D. Quantitative cell polarity imaging defines leader-to-follower transitions during collective migration and the key role of microtubule-dependent adherens junction formation. Development. 2014;141:1282–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.101675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Carvajal A, Navajas Acedo J, Jiang L, Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene A, Alexander R, Li H, Piotrowski T. Regeneration of Sensory Hair Cells Requires Localized Interactions between the Notch and Wnt Pathways. Dev Cell. 2015;34:267–82. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse GW, Pickles JO. Paired development of hair cells in neuromasts of the teleost lateral line. Proc Biol Sci. 1991;246:123–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapede D, Rossel M, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Ghysen A. Role of SDF1 chemokine in the development of lateral line efferent and facial motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1714–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406382102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Kawakami K, Ishitani T. Visualization and exploration of Tcf/Lef function using a highly responsive Wnt/beta-catenin signaling-reporter transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2012;370:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedy L, Knecht DA, Mackay GM, Insall RH. Self-Generated Chemoattractant Gradients: Attractant Depletion Extends the Range and Robustness of Chemotaxis. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia LE, Young RM, Hawkins TA, Stickney HL, Cavodeassi F, Schwarz Q, Pullin LM, Villegas R, Moro E, Argenton F, Allende ML, Wilson SW. Lef1-dependent Wnt/beta-catenin signalling drives the proliferative engine that maintains tissue homeostasis during lateral line development. Development. 2011;138:3931–41. doi: 10.1242/dev.062695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1026–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venero Galanternik M, Navajas Acedo J, Romero-Carvajal A, Piotrowski T. Imaging collective cell migration and hair cell regeneration in the sensory lateral line. Methods Cell Biol. 2016;134:211–56. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G, Lewellis SW, Wang J, Reynolds E, Nicholson C, Knaut H. Generation and dynamics of an endogenous, self-generated signaling gradient across a migrating tissue. Cell. 2013;155:674–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.