Abstract

We describe a stereoselective synthesis of an optically active (1R, 3aS, 5R, 6S, 7aR)-octahydro-1,6-epoxy-isobenzo-furan-5-ol derivative. This stereochemically defined heterocycle serves as a high-affinity ligand for a variety of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. The key synthetic steps involve a highly enantioselective enzymatic desymmetrization of meso-1,2(dihydroxymethyl)cyclohex-4-ene and conversion of the resulting optically active alcohol to a methoxy hexahydroisobenzofuran derivative. A substrate controlled stereoselective dihydroxylation afforded syn-1,2-diols. Oxidation of diol provided the substituted 1,2-diketone and L-Selectride reduction provided the corresponding inverted syn-1,2-diols. Acid catalyzed cyclization furnished the ligand alcohol in optically active form.

Keywords: Enzymatic synthesis, Enantioselective synthesis, HIV-1 protease inhibitor, P2 ligand, Stereoselective reduction

Structure-based molecular design is a highly innovative area that led to impressive development of many efficacious and first-in-class drugs for the treatment of a variety of human diseases [1,2]. Notable successes are apparent in design and development of HIV-1 protease inhibitor drugs for treatment of HIV/AIDS [3,4]. Also, structure-based design has significant impact in the development of kinase inhibitor-based drugs for treatment of a range of cancers and non-cancer indications [5,6]. One of the important features of structure-based design is the innovative creation of small-molecule ligands or scaffolds which can selectively modulate activity and improve physiological properties of drug molecules [1,7]. These research efforts often lead to novel heterocyclic molecules containing structural and stereochemical complexities. The development of HIV-1 protease inhibitor (PI) drugs is regarded as a major achievement in modern drug discovery and medicinal chemistry. The introduction of PIs into combination therapy with reverse transcriptase inhibitor marked the beginning of an important era of HIV/AIDS therapy [8,9]. The highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with PIs became the standard treatment of patients with HIV-1 infection and AIDS. While there is no cure for HIV-1/AIDS to date, the current antiretroviral therapy transformed HIV/AIDS from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic disorder [10,11]. There are now many suitable drug combinations that are effective in suppressing viral replication in HIV-1 infected patients. However, PI drugs are often associated with side effects and the development of viral resistance can lead to virologic breakthrough and treatment failure [12,13]. Therefore, it is very important to develop potent and more effective new classes of PI drugs. As part of our continuing research in this area, we designed a range of highly potent PIs that maintained broad-spectrum antiviral activity against multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants. One of the key elements of our PI design strategy is to promote extensive hydrogen bonding interactions in the active site of HIV-1 protease [14,15]. These design strategies, based upon enhancing ‘backbone binding,’ led us to design a wide range of bicyclic polyether scaffolds that mimic peptide bond interactions and alleviate peptide-like features and side effects [1,3]. One of these PIs is Darunavir (1, Figure 1), an FDA approved widely used PI drug that contains a fused bicyclic bis-tetrahydrofuran (bis-THF) as a high affinity P2 ligand [16,17]. This heterocyclic ligand is critically important for darunavir’s durable drug-resistance profile. However, darunavir-resistant HIV-1 variants have now emerged and there are limited options for treating these patients [18,19]. Recently, we reported the design and synthesis of a range of PIs where we incorporated conformationally constrained polycyclic ethers as the P2 ligands [20,21]. Many of these compounds, including compound 2 exhibited very potent HIV-1 protease inhibitory and antiviral activity compared to darunavir [22,23]. Compound 2 contains a tricyclic cyclohexane fused bis-tetrahydrofuran as the P2 ligand. This compound displayed an enzyme Ki of 54 pM and antiviral EC50 value of 86 pM in MT-2 human-T-lymphoid cells exposed to HIVLAI. Our X-ray crystal structural analysis of HIV-1 protease and compound 2 complex revealed that the tricyclic ligand makes extensive interactions with the backbone atoms in the S2 subsite of HIV-1 protease. Interestingly, inhibitor 3 with enantiomeric tricyclic P2 ligand also exhibited very potent activity comparable to darunavir [17,22]. The ligand alcohol has complex architecture and possesses a tricyclic ring skeleton containing five contiguous chiral centers. Our initial synthesis of these structurally complex (1R, 3aS, 5R, 6S, 7aR)-octahydro-1,6-epoxy, isobenzo-furan-5-ol ligands needed improvement for further expansion of structure-activity relationship studies of these potent PIs. The synthesis involved a syn-dihydroxylation from a sterically hindered face of a functionalized cyclohexene substrate which preceded with no diastereoselectivity. Herein we report an improved synthesis of the ligand alcohol involving a highly enantioselective enzymatic desymmetrization of meso-1,2-(dihydroxymethyl)cyclohex-4-ene, a substrate controlled highly diasereoselective dihydroxylation, followed by inversion of the syn-1,2-diol functionality by oxidation and stereoselective reduction sequence. We demonstrated the utility by converting the optically active ligand alcohol to a potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Structures of HIV-1 protease inhibitors 1–3.

Our previous syntheses of compounds 2, 3 and other PIs (4) containing the tricyclic ligands were carried out by carbamate formation using the cyclohexane fused bis-THF ligand alcohol 5 and amine derivative 6 (Scheme 1) [22]. Synthesis involved an efficient enzymatic desymmetrization of meso-1,2(dihydroxy methyl) cyclohex-4-ene using porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL) to provide optically active alcohol 7 [24]. It was converted to a functionalized cyclohexene derivative 8. Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation [25] of 8 with AD-mix-β provided a 1:1 mixture of diastereomeric diols 9 and 10 in good yield. The diols were separated and only diastereomer 9 was utilized for the synthesis of ligand alcohol 5.

Scheme 1.

Previous synthesis of inhibitors and optically active tricyclic ligand alcohol.

To further utilize diastereomer 10 for the synthesis of ligand alcohol 5, we first planned to invert the 1,2-diol stereochemistry by an oxidation/reduction sequence (Scheme 2). As shown, saponification of acetate 10 with 1N aqueous NaOH in MeOH at 0 °C to 23 °C for 1 h provided the corresponding triol derivative. Exposure of the resulting triol to a catalytic amount of camphorsulfonic acid (CSA) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and MeOH (5:1) at 0 °C to 23 °C for 1 h resulted in methyl acetal derivatives 11 and 12 as a mixture (7:3) of diastereomers by 1H-NMR analysis. The Isomers were separated by silica gel column chromatography and the major epimer 11 was utilized for the synthesis of ligand 5. Swern oxidation of diol 11 resulted in diketone derivative 13 in 60% yield. Reduction of diketone with NaBH4 in MeOH provided diol 14 and 15 as a mixture (3:1) of diastereomers by 1H-NMR analysis. Exposure of this mixture to CSA in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C for 1 h furnished optically active ligand alcohol 5 in 50% yield from diketone 13. The overall route is far from satisfactory and diastereomeric ratios were particularly marginal. Dihydroxylation of 8 with OsO4 and NMO at 23 °C provided a mixture of diastereomers 9 and 10 in a 30:70 ratio in 88% yield. In comparison, Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation of 8 from the β-face using AD-mix-β improved the diastereomeric ratio of the desired diol derivative 9 and undesired isomer 10 to only 1:1 with a combined yield of 90%.

Scheme 2.

Conversion of diastereomer 10 to tricyclic ligand alcohol 5.

We therefore examined a modified route without using AD-mix mediated hydroxylation step starting with active alcohol 7 (Scheme 3). Optically active alcohol 7 was converted to methyl acetal 16 as a major isomer in a 3-step sequence involving, (1) Swern oxidation of alcohol 7 to aldehyde, (2) treatment of the resulting aldehyde with CH(OMe)3 in the presence of tetrabutylammonium tribromide (TBABr3), followed by treatment with 1N NaOH, and (3) reaction of the resulting methyl acetal with a catalytic amount of CSA in a mixture (5:1) of CH2Cl2 and MeOH at 23 °C for 1 h. Methyl acetal 16 was obtained as a major isomer (>90% de by 1H-NMR) in 75% yield over 3-steps. Our plan was to take advantage of bicyclic alkene substrate and carry out selective dihydroxylation from the convex face and then invert diol stereochemistry by oxidation and reduction sequence. We presume that reduction of the resulting diketone will proceed stereoselectively from the favorable convex face to provide the desired inverted syn-1,2 diol. It should be noted that the stereochemical outcome of the dihydroxylation reaction is not important since the diol would be oxidized to diketone in the next step. However, we surveyed dihydroxylation of 16 under a variety of reaction conditions (Table 1) to obtain product with high diastereoselectivity to avoid separation of isomers. Dihydroxylation of 16 with OsO4 and NMO in aqueous acetone (9:1) afforded mixture of diastereomers 12 and 17 as an 80:20 mixture (entry 1) [25]. The corresponding reaction in a 1:1 mixture of t-BuOH and water did not improve the ratio (entry 2). When dihydroxylation was carried out with K2OsO4 and K3Fe(CN)6 as oxidant, only a slight improvement of ratio was observed (entry 3). Dihydroxylation with a catalytic amount of K2OsO4 and K3Fe(CN)6 as the oxidant provided excellent yield and diastereomeric mixture (96:4) ratio (entries 4, 5). Dihydroxylation of 16 with OSO4 and Ba(ClO4)2 also provided only trace amount of products (entry 6). Dihydroxylation with KMnO4 in aqueous acetone in the presence of H2O2 provided diol mixtures 12 and 17 with good diastereoselectivity (9:1 ratio) in 40% yield. (entry 7). The absolute stereochemistry of the major diastereomer 12 was determined by X-ray crystallography [26,27]. An ORTEP drawing supported (Figure 2) the relative and absolute stereochemistry of 12.

Scheme 3.

Alternative synthesis of optically active cyclohexane-fused bis -THF derivative 5.

Table 1.

Dihydroxylation of alkene 16 to diol diastereomersa

| Entry | Reagents | Solvents | Yield (%)b | Ratio (dr, 12:17)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OsO4 (1 mol%), NMO | Me2CO-H2O (9:1) | 88 | 80:20 |

| 2 | OsO4 (1 mol%), NMO | t-BuOH-H2O (1:1) | 85 | 81:19 |

| 3 | K2OsO4.2H2O (1mol%), NMO | t-BuOH-H2O (1:1) | 80 | 83:17 |

| 4. | K2OsO4.2H2O (1 mol%), K3Fe(CN)6 | t-BuOH-H2O (1:1) | 96 | 95:5 |

| 5 | K2OsO4.2H2O (1 mol%), K3Fe(CN)6 | Me2CO-H2O (9:1) | 82 | 94:6 |

| 6 | OsO4 (1 mol%), Ba(ClO4)2 | THF-H2O (1:1) | trace | --- |

| 7 | KMnO4 (0.5 equiv), H2O2 | Me2CO-H2O (2:1) | 40 | 90:10 |

Reactions were carried out 0.1 to 0.3 mmol scale at 23 °C for 24 h using 3 equiv of oxidant.

Combined yields after purification by column chromatography.

Ratio’s determined by 1H-NMR analysis.

Figure 2:

ORTEP Drawing of X-ray crystal structure of 1,2-syn diol derivative 12

For the synthesis of ligand alcohol 5, diol mixture 12 and 17 (from entry 4) was oxidized using Swern oxidation at −78 °C to provide diketone 18 in 58% yield. Oxidation of diols with IBX in DMSO also provided diketone 18, however, in reduced yield (20%). Substrate controlled reduction of diketone 18 was carried out under a variety of reduction conditions (Table 2). Reduction of 18 with NaBH4 in MeOH at 0 °C to 23 °C afforded the desired diastereomer 17 as a 65:35 mixture. Reduction with NaBH(OAc)3 only provided trace amount of product. Reduction with Na(CN)BH3 in MeOH resulted in major isomer 17 as a mixture (4:1) in 65% yield (entry 3). Reduction of 18 with L-Selectride in ether at 0°C to 23 °C afforded 17 as a major isomer (95:5 ratio) in 68% yield (entry 5) [28]. When the reduction was carried out with catecholborane and Ti(OiPr)4 in THF at 0 °C to 23 °C, diastereomeric ratio (48:52) was in favor of the minor isomer (entry 6). Reduction of 18 with NaBH4 in the presence of CeCl3 did not exibit any diastereoselectivity (entry 7). The high degree of diastereoselectivity associated with L-Selectride reduction of diketone 18 to syn-1,2-diol 17 (entry 5) can be explained using the proposed stereochemical model (Scheme 4) similar to the reported reduction of tetralin-1,4-dione [29].Presumably, the first reduction proceeds from the less hindered convex face of diketone 18 providing alkyl boranyloxy intermediates 20A or 20B. The second reduction then proceeds away from the bulky boranyloxy intermediates to provide syn-1,2-diol after hydrolysis. For the synthesis of ligand alcohol 5, diol 17 was treated with a catalytic amount of CSA in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C for 2 h to furnish 5 in 88% yield. Ligand alcohol 5 was converted to activated carbonate 19. As shown, reaction of alcohol 5 with p-nitrophenylchloroformate in the presence of pyridine in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C for 12 h provided carbonate 19 in good yield.

Table 2.

Reduction of 1,2-diketone 18 with various reagentsa

| Entry | Reagents | Solvent | Yield (%)b | Ratioc (dr, 17:12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NaBH4 (3 equiv) | MeOH | 80 | 65:35 |

| 2 | NaBH(OAc)3 (3 equiv) | MeOH | --- | --- |

| 3 | Na(CN)BH3 (3 equiv) | MeOH | 65 | 82:18 |

| 4 | DIBAL-H (3 equiv) | CH2Q2 | --- | --- |

| 5 | L-Selectride (3 equiv) | Et2O | 68 | 95:5 |

| 6 | Catecholborane (2.5 equiv), Ti(OiPr)4 | THF | 44 | 48:52 |

| 7 | NaBH4 (3 equiv) CeCl3 | MeOH | 60 | 50:50 |

Reactions were carried out in 0.1 to 0.3 mmol scale at 23 °C for 24 h.

Combined yields after purification by column chromatography.

Ratio’s determined by 1H-NMR analysis (500 MHz).

Scheme 4.

Stereochemical model for L-Selectride reduction of 18.

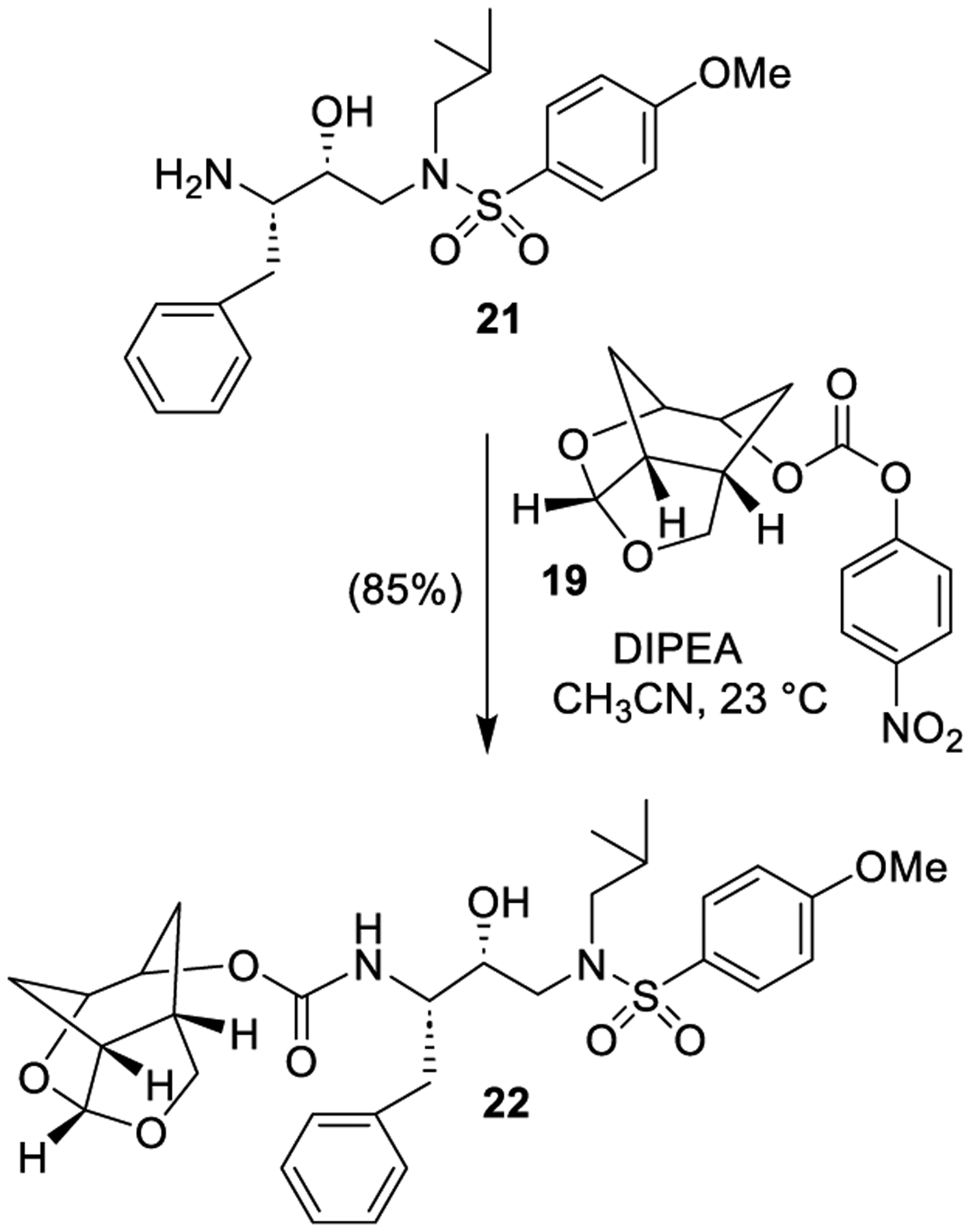

Enantiomerically pure ligand alcohol was then converted to a potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor (Scheme 5). Optically active 3(S)-amino-2(R)-hydroxy-4-phenylbutyl-4-methoxyphenyl sulfonamide 21 was prepared as described previously [22,30]. Reaction of amino alcohol 21 with p-nitrophenyl carbonate 19 in the presence of diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in CH3CN at 23 °C for 72 h afforded carbamate derivative 22 in 85% yield. Inhibitor 22 exhibited HIV-1 protease inhibitory Ki value of 8 pM based upon an assay developed by Toth and Marshall [31].

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of potent protease inhibitor 22.

In summary, we achieved an optically active synthesis of (1R, 3aS, 5R, 6S, 7aR)-octahydro-1,6-epoxy-isobenzofuran-5-ol, a very potent P2 ligand for a potent class of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. The tricyclic ligand alcohol contains five contiguous stereogenic centers. The synthesis utilized an enantioselective desymmetrization of meso-1,2(dihydroxymethyl) cyclohex-4-ene derivative using commercially available PPL. Three other chiral centers were then introduced using substrate-controlled reactions. Optically active alcohol was converted to stereoselective syn-1,2-diol functionality by substrate-controlled dihydroxylation. Swern oxidation of the resulting 1,2-syn-diols provided 1,2-diketone derivative, which was reduced with L-Selectride to provide the corresponding inverted syn-1,2-diols stereoselectively. Acid catalyzed cyclization provided tricyclic ligand alcohol with high enantiomeric purity. Optically active alcohol was also converted to potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor 22 in good yield. The current route offers convenient access to tricyclic conformationally constrained ligand alcohol for synthesis of HIV-1 protease inhibitors for further studies. Additional applications of ligand alcohol 5 in the synthesis of new PIs are currently in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant AI150466). The authors would like to thank the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research, which supports the shared NMR and mass spectrometry facilities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

References and notes

- [1].Hubbard RE, Structure-Based Drug Discovery: An Overview, RSC Publishing, England, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ghosh AK, Gemma S, Structure-Based Design of Drugs and Other Bioactive Molecules: Tools and Strategies; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ghosh AK, Osswald HL, Prato G, J. Med. Chem. 59 (2016) 5172–5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27 (1998) 249–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cohen P, Cross D, Janne PA, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20 (2021) 551–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Toledo LM, Lydon NB, Elbaum D, Curr. Med. Chem. 6 (1999) 775–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Reynolds CH, Merz KM, Ringe D, eds. (2010). Drug Design: Structure- and Ligand-Based Approaches (1 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maenza J, Flexner C, Am. Fam. Physician. 57 (1998) 2789–2798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moreno S, Perno CF, Mallon PW, Behrens G, Corbeau P, Routy J-P, Darcis G, HIV Med. 20 (2019) 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV, Lancet. 382 (2013) 1525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Logie C, Gadalla TM, AIDS Care. 21 (2009) 742–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Menendez-Arias L, Antiviral Res. 85 (2010) 210–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Esté JA, Cihlar TC, Antivir. Res. 85 (2010) 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ghosh AK, Chapsal BD, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (2008) 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ghosh AK, Anderson DD, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 1778–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ghosh AK, Sridhar PR, Kumaragurubaran N, Koh Y, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, ChemMedChem (2006) 939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ghosh AK, Dawson ZL, Mitsuya H, Bioorg. & Med. Chem. 15 (2007) 7576–7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lambert-Niclot S, Flandre P, Canestri A, Peytavin, Blanc GC, Agher R, Soulié C, M. Wirden, Katlama C, Calvez V, Marcelin AG, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 52 (2008) 491–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].De Meyer S, Vangeneugden T, Van Baelen B, De Paepe E, Van Marck H, Picchio G, Lefebvre E, de Béthune MP, AIDS research and human retroviruses. 24 (2008) 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Aoki M, Hayashi H, Rao KV, Das D, Higashi-Kuwata N, Bulut H, Aoki-Ogata H, Takamatsu Y, Yedidi RS, Davis DA, Hattori S.-i., Nishida N, Hasegawa K, Takamune N, Nyalapatla PR, Osswald HL, Jono H, Saito H, Yarchoan R, Misumi S, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H, eLife 6 (2017) e28020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ghosh AK, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, Chem. Comm. 58 (2022) 11762–11782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ghosh AK, Kovela S, Osswald HL, Amano M, Aoki M, Agniswamy J, Wang Y-F, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, J. Med. Chem. 63 (2020) 4867–4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ghosh AK, Kovela S, Sharma A, Shahabi D, Ghosh AK, Hopkins DR, Yadav M, Johnson ME, Agniswamy J, Wang Y-F, Aoki M, Amano M, Weber IT, Mitsuya H, ChemMedChem. 17 (2022) e202200058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Danieli B, Lesma G, Mauro M, Palmisano G, Passarella D, The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 60 (1995) 2506–2513. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kolb HC, Van Nieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB, Chemical Reviews. 94 (1994) 2483–2547. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Single-Crystal X-Ray analysis was performed in-house, Zeller Matt, X-Ray Crystallography laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Purdue University. West Lafayette, IN 47907. [Google Scholar]

- [27].CCDC 2333184 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for compound 12. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via. www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- [28].Maruyama S, Ogihara N, Adachi I, Ohotawa J, morisaki M, Chemical and pharmaceutical bulletin. 35 (1987) 1847–1852. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kündig EP, Enriquez-Garcia A, J Org Chem. 4 (2008) 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ghosh AK, Kincaid JF, Cho W, Walters DE, Krishnan K, Hussain KA, Koo Y, Cho H, Rudall C, Holland L, Buthod J, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Letters, 8 (1998) 687–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Toth MV, Marshall GR, International Journal of Peptide and Protein Research, 36 (1990) 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.