Abstract

This report describes the bone reduction guide which was digitally obtained to improve diagnosis, treatment outcome and follow-up. Treatment of gingival smiles due to altered passive eruption should include interdisciplinary planning and smile design to facilitate the prediction of treatment outcome. Crown lengthening surgery can be supported by digital tools to improve surgical planning and follow-up. A 30-year-old female patient was referred to a private dental clinic seeking solutions for her gingival smile. Based on the anatomical crown length, a smile design was created, and the patient was presented with a simulated smile before treatment. In the surgical phase, a full-thickness flap was raised in the upper jaw to achieve the desired outcome. Using cone-beam computed tomography to determine cementoenamel junction for smile design and treatment planning brings many benefits. Patients and clinicians can foresee treatment results. From there, appropriate changes can be made. The bone reduction guide is designed to rest on the bone to help the clinician cut the bone accurately and thoroughly follow the established plan.

Keywords: CAD-CAM, DSD, periodontics, surgical crown lengthening, surgical guide

Introduction

Crown lengthening is a frequently performed dental procedure, serving both aesthetic and functional purposes. It is employed to enhance visual aesthetics in cases of gingival smile correction and to expose healthy tooth structure beneath the gum for restorative purposes. The success of dental crown lengthening relies heavily on precise planning and execution, particularly during osseous resection. Inaccurate adjustments may result in suboptimal aesthetic outcomes or hinder the prosthetic restoration process.

Traditional approaches to dental crown lengthening heavily depend on the clinician’s visual assessment and involve osseous resection ~3–4 mm from the prospective gingival margin to recreate the biologic width [1–3]. This method relies on manual measurements and the surgeon’s expertise. In recent years, the field of dentistry has experienced transformative advancements through imaging technology and computer-aided design (CAD), providing new dimensions to treatment planning and execution, and 3D-printed ‘double guide’ stents have emerged, enabling clinicians to simultaneously reduce the gingiva and bone according to the treatment plan [4]. However, these guides are tooth and gingiva-supported, resulting in a distinct gap between the guide and the bone. This gap, coupled with the angle of the drill, may compromise precision during bone cutting.

This article introduces, for the first time, a novel design method for guiding bone cutting in dental crown lengthening procedures. It incorporates digital smile design to facilitate communication with the patient and plan crown lengthening treatment based on the smile design.

Patient case

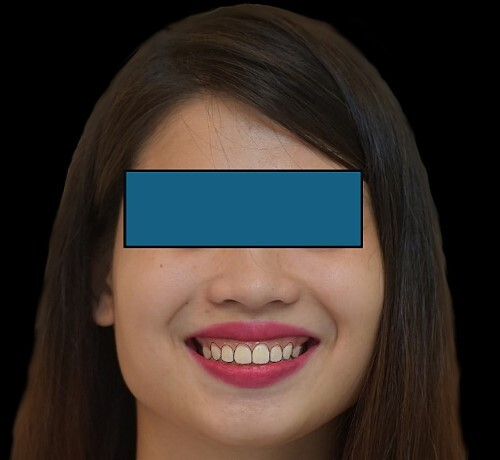

A 30-year-old female patient was referred to a private dental clinic seeking solutions for her gingival smile. The initial assessment encompassed a thorough clinical examination, photographic documentation, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans and impressions to collect essential data (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Initial patient smile.

The length of the tooth crowns was clinically measured on the dental model (see Fig. 2), whereas the anatomical length was evaluated through CBCT images (see Figs 3 and 4). Based on the anatomical crown length, a smile design was created, and the patient was presented with a simulated smile before treatment (Figs 5 and 6). Upon approval of the simulated smile, a treatment plan was devised, establishing the future bone margin at 3-mm apical to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) for each tooth, as indicated in Fig. 7.

Figure 2.

The clinical crown length.

Figure 3.

In CBCT, determine the CEJ of each tooth to ascertain the anatomical crown length.

Figure 4.

Simulation of the anatomical crown length.

Figure 5.

DSD with the anticipated gingival margin determined by the CEJ location.

Figure 6.

Simulation smile.

Figure 7.

Simulating the position of the proposed bone margin 3 mm apical to the anticipated gingival margin.

The STL files of the maxilla and teeth were manipulated using BlueSky Plan software (see Fig. 8). Subsequently, a guide was designed to facilitate osseous resection, adapting to both the teeth and the maxilla (see Fig. 9). In the surgical phase, a full-thickness flap was raised in the upper jaw, and the guide was affixed (see Figs 10 and 11). The guide snugly conformed to the bone, and its position was verified with a margin distance from CEJ set at 3 mm (see Figs 12 and 13). Postoperative results at 2 and 12 months are shown in Figs 14 and 15. The final outcomes closely resembled the Digital Smile Design (DSD) simulation conducted before treatment (see Fig. 16).

Figure 8.

Demonstrates the manipulable STL model.

Figure 9.

Digitally planned surgical guide.

Figure 10.

A full thickness flap was reflected.

Figure 11.

The tray, resting on the bone, is positioned correctly.

Figure 12.

The bone crest is anticipated to be 3 mm from CEJ.

Figure 13.

Crestal bone after grinding.

Figure 14.

Postoperative results at 2 months.

Figure 15.

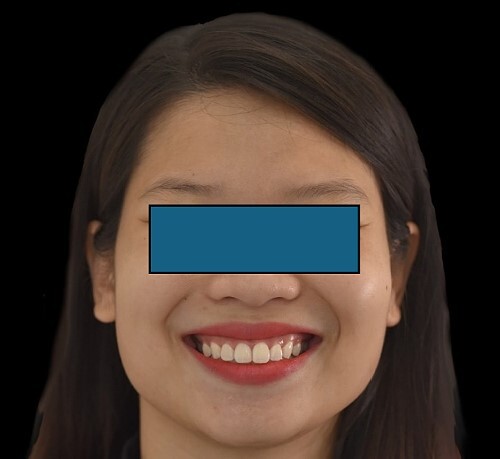

Postoperative results at 12 months.

Figure 16.

The final outcomes closely resembled the DSD simulation.

Discussion

The success of dental crown lengthening surgery relies on the precise adjustment of the bone position in alignment with the treatment plan [3]. CBCT measurements during treatment planning empower clinicians to anticipate outcomes. The osseous resection guide serves as a crucial tool for accurately adjusting the bone, translating the treatment plan into reality. In this case, the patient sought correction of a gingival smile without the need for prosthetic restoration. Therefore, it was imperative to ensure that the future gum margin did not exceed the CEJ. Determining the CEJ before treatment planning, particularly in cases where the bone margin is close to the CEJ, is not always achievable through clinical assessment alone. In this case, it was also very important to consider the altered passive eruption as this was a shorter clinical crowns. On utilizing the classification by Coslet et al., this case was classified as a 2B type case which requires an apically positioned flap along with osseous surgery for correction of the condition [5–8]. CBCT-based CEJ determination is essential in conjunction with the clinical altered passive eruption classification, and the future smile design should be adjusted accordingly [9].

Coachman et al. [10] highlighted the advantages of smile design based on CBCT compared with older methods; however, their bone grinding guide still relied on the gingival height rather than the bone. A similar approach was outlined by Pedrinaci et al. [11–13], where the bone grinding guide rested on the gingiva, creating a specific gap with the bone after a full-thickness flap was raised. This gap could compromise the clinician’s perspective and drill angle, leading to imprecise bone grinding results [14]. Alternatively, clinicians might need to remeasure each tooth after grinding, diminishing the efficacy of the bone grinding guide.

Conclusion

Utilizing CBCT to determine CEJ for smile design and treatment planning offers numerous advantages. Patients and clinicians can anticipate treatment results, allowing for necessary adjustments. The bone reduction guide is designed to rest on the bone, aiding the clinician in accurately cutting the bone and thoroughly following the established plan.

Contributor Information

Nguyen Thai Cong, Department of Periodontology and Implantology, Faculty of Dentistry, Van Lang University, Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam.

Pham Hoai Nam, Department of Periodontology and Implantology, Faculty of Dentistry, Van Lang University, Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam.

Hoang Viet, Department of Orthodontics and Pedodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Van Lang University, Ho Chi Minh City 700000, Vietnam.

Anand Marya, Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Puthisastra, Phnom Penh 12211, Cambodia; Dental Research Unit, Center for Global Health Research, Saveetha Medical College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai 602105, Tamil Nadu, India.

Clinical and surgical implications

The use of digital tools allows the clinician to plan according to smile aesthetics with proper communication with the team and patient, leading to more predictable, and less invasive surgical technique and increasing patient comfort.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

None declared.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for use of the images for academic and research purposes.

Informed consent

Written patient consent was obtained from the patient for use of her extra-oral and intra-oral records for academic and research purposes.

References

- 1. Planciunas L, Puriene A, Mackeviciene G. Surgical lengthening of the clinical tooth crown. Stomatologija 2006;8:88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cunliffe J, Grey N. Crown lengthening surgery–indications and techniques. Dent Update 2008;35:29.–30, 32, 34–35. 10.12968/denu.2008.35.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nautiyal A, Gujjari S, Kumar V. Aesthetic crown lengthening using Chu aesthetic gauges and evaluation of biologic width healing. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:ZC51–5. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/14115.7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendoza-Azpur G, Cornejo H, Villanueva M, et al. Periodontal plastic surgery for esthetic crown lengthening by using data merging and a CAD-CAM surgical guide. J Prosthet Dent 2022;127:556–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coslet JG, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan 1977;70:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoang V, Tran PH, Dang TT. Buccal corridor and gummy smile treatment with MARPE and gingivoplasty: a 2-year follow-up case report. APOS Trends Orthod 2024. 10.25259/APOS_216_2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viet H, Phuoc TH, Tuyen HM, Marya A. Use of surgical grafting as a part of multidisciplinary treatment for a patient treated with fixed orthodontic therapy to improve treatment outcomes. Clin Case Rep 2023;12:e8386. 10.1002/ccr3.8386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rathore N, Desai A, Trehan M, et al. Ortho-Perio interrelationship. Treatment challenges. N Y State Dent J 2015;81:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Batista EL Jr, Moreira CC, Batista FC, et al. Altered passive eruption diagnosis and treatment: a cone beam computed tomography-based reappraisal of the condition. J Clin Periodontol 2012;39:1089–96. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coachman C, Valavanis K, Silveira FC, et al. The crown lengthening double guide and the digital Perio analysis. J Esthet Restor Dent 2022;35:215–21. 10.1111/jerd.12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pedrinaci I, Calatrava J, Flores J, et al. Multifunctional anatomical prototypes (MAPs): treatment of excessive gingival display due to altered passive eruption. J Esthet Restor Dent 2023;35:1058–67. 10.1111/jerd.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Awad MG, Ellouze S, Ashley S, et al. Accuracy of digital predictions with CAD/CAM labial and lingual appliances: a retrospective cohort study. Semin Orthod 2018;24:393–406 WB Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vandekar M, Fadia D, Vaid NR, Doshi V. Rapid prototyping as an adjunct for autotransplantation of impacted teeth in the Esthetic zone. J Clin Orthod 2015;49:711–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim H, Keum BT, Seo HJ, et al. Rationale of total arch intrusion for gummy smile correction. Semin Orthod 2022;28:149–56. 10.1053/j.sodo.2022.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]