Abstract

Plasmodium vivax is responsible for the majority of malaria cases outside of Africa, and results in substantial morbidity. Transmission blocking vaccines are a potentially powerful component of a multi-faceted public health approach to controlling or eliminating malaria. We report the first phase 1 clinical trial of a P. vivax transmission blocking vaccine in humans. The Pvs25H vaccine is a recombinant protein derived from the Pvs25 surface antigen of P. vivax ookinetes. The protein was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, purified, and adsorbed onto Alhydrogel®. Ten volunteers in each of three dose groups (5, 20, or 80 μg) were vaccinated by intramuscular injection in an open-label study at 0, 28 and 180 days. No vaccine-related serious adverse events were observed. The majority of adverse events causally related to vaccination were mild or moderate in severity. Injection site tenderness was the most commonly observed adverse event. Anti-Pvs25H antibody levels measured by ELISA peaked after the third vaccination. Vaccine-induced antibody is functionally active as evidenced by significant transmission blocking activity in the membrane feeding assay. Correlation between antibody concentration and degree of inhibition was observed. Pvs25H generates transmission blocking immunity in humans against P. vivax demonstrating the potential of this antigen as a component of a transmission blocking vaccine.

Keywords: Clinical trial, Plasmodium vivax, Transmission blocking vaccine

1. Introduction

A vaccine that prevents the transmission of Plasmodium vivax malaria would be an important addition to the current methods for controlling the spread of malaria parasites. Malaria remains a disease of major importance with approximately 1.5 billion people at risk worldwide [1]. Although the majority of clinical cases and malaria-related mortality occur in areas of high P. falciparum transmission in sub-Saharan Africa, most of the world’s population at risk for malaria live in areas with comparatively low malaria transmission, where either P. vivax alone or a combination of P. falciparum and P. vivax are the important species of malaria. Outside of Africa, more than 50% of malaria cases can be attributed to P. vivax [1]. The major direct impact of this parasite is on morbidity, with a substantial indirect impact on healthcare delivery costs.

Malaria vaccines are being developed that target all three stages of the malaria parasite’s life cycle [2]. Pre-erythrocytic vaccines and blood stage vaccines aim to block or reduce asexual blood stage infection and reduce the disease burden. Anti-mosquito stage vaccines are designed to prevent malaria transmission, potentially reducing the overall burden of disease and contributing to elimination of the parasite. These transmission blocking vaccines (TBV) target antigens on gametes, zygotes or ookinetes, and have an unusual site of action. Antibody ingested with the gametocytes kills parasites in the mosquito midgut, i.e. the antibody kills the parasite outside the person immunized.

Pvs25H is a recombinant protein corresponding to the P. vivax ookinete surface antigen, Pvs25 [3]. Pvs25H is a 20.5 kDa protein that encodes amino acids 23 to 195 of Pvs25 from the Salvador 1 isolate of P. vivax [4]. Studies in mice, rabbits, and rhesus monkeys demonstrated that Pvs25H formulated on aluminum hydroxide gel (Alhydrogel®) induces antibodies that block development of P. vivax in mosquitoes, as demonstrated by the ex vivo membrane feeding assay [5,6].

Pvs25 is not expressed by P. vivax during its life cycle in humans and is, therefore, not subject to immune selection pressure in the human host. Thus, there is minimal sequence diversity [3,6] which simplifies vaccine development. However, the lack of expression in humans means that natural boosting of the immune response to Pvs25 will not occur following an infection. The conditions suitable for deployment of mosquito stage transmission blocking vaccines have recently been reviewed [4,7]. Briefly, if sufficient coverage can be achieved to attain significant herd immunity, these vaccines are expected to form a useful component to integrated malaria control, especially in low endemic areas or areas subject to epidemics.

This paper reports the first phase 1 human clinical trial of a P. vivax transmission blocking vaccine. We show that vaccination with Pvs25H/Alhydrogel® is safe and induces antibody that inhibits parasite development in mosquitoes.

2. Methods

2.1. Pvs25H/Alhydrogel® vaccine

Expression and purification of Pvs25H has been reported [8]. Briefly, Pvs25H was expressed as a secreted recombinant protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and purified by affinity chromatography, hydrophobic interaction chromatography and gel permeation chromatography. The purification process separated the correctly folded product from incorrectly folded material, as well as product and non-product derived impurities [8]. Pvs25H was manufactured under current good manufacturing practices at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Pilot Bioproduction Facility.

Pvs25H was adsorbed onto Alhydrogel® (HCI Biosector, Denmark) as described, with minor modifications [9]. Briefly, either 5, 20, or 80 μg of Pvs25H was adsorbed to 800 μg of Alhydrogel® in unbuffered saline by mixing at room temperature for 1 h. The formulations were vialed by the Pharmaceutical Development Section, NIH. The formulation was supplied in single dose vials as a suspension, without stabilizers or preservatives, in sterile saline solution. Three lots of clinical grade vaccine were prepared containing either 5, 20, or 80 μg of Pvs25H and 800 μg of Alhydrogel® (424 μg aluminum per dose) per 0.5 mL dose.

The Pvs25H vaccine passed all tests of purity (endotoxin level, sterility, general safety), stability and potency. More than 99% of the antigen was adsorbed to the Alhydrogel®.Prior to human testing, a pharmacology/toxicology study was conducted in New Zealand white rabbits. Each rabbit received four immunizations at days 1, 29, 57 and 85. Four groups of 12 rabbits, 6 males and 6 females in each group, received 0 (Alhydrogel® placebo), 1.25, 20 or 80 μg of Pvs25H, respectively, at each immunization. Rabbits were evaluated for mortality, clinical observations, local reactogenicity, body weights, food consumption, clinical pathology, gross pathology, organ weights, histopathology, and immunogenicity. Injection site erythema and edema were scored from 0 to 4 following the Draize Scoring System [10].

2.2. Vaccine trial

2.2.1. Study design

An open-label dose-escalating phase 1 clinical trial was conducted in healthy adult volunteers under an approved U.S. Food and Drug Administration Investigational New Drug Application. Ten volunteers in each of three dose groups (5, 20, and 80 μg) were vaccinated by intramuscular injection in alternate arms at 0, 28 and 180 days. For safety purposes, each dose cohort of 10 volunteers was staggered such that three volunteers were vaccinated 1 week prior to the remaining seven volunteers. Escalation to the next higher dose required approval by an independent safety monitoring committee. The committee reviewed data from the 10 vaccinees in the lower dose group collected between day 0 (day of first vaccination) and day 42 (14 days following the second vaccination) for 3 volunteers, or day 35 (7 days following the second vaccination) for 7 volunteers prior to approving dose escalation. Anti-Pvs25H antibody was measured by ELISA with sera collected on days 0, 14, 28, 42, 150, 180, 194, 270, and 364. Transmission blocking activity was measured by membrane feeding assays with sera collected on days 180 and 194.

2.2.2. Volunteers

Thirty healthy volunteers, 18–50 years of age, were recruited and enrolled from the metropolitan Baltimore area. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained, and volunteers were required to pass an informed consent comprehension examination prior to enrollment. All females had a serum pregnancy test at screening and urine β-hCG testing immediately prior to each vaccination. Volunteers were excluded if they had evidence of clinically significant systemic disease; were pregnant or breast feeding; had serologic evidence of HIV, chronic hepatitis B, or hepatitis C infection; or had previously participated in a malaria vaccine clinical trial.

2.2.3. Assessment of safety and tolerability

Following each vaccination, volunteers were observed for 30 min and then evaluated 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after vaccination for evidence of local and/or systemic reactogenicity. Volunteers recorded their oral temperature three times daily, as well as local and solicited systemic reactogenicity on diary cards for 14 days following each vaccination. History and physical examination were performed at each follow-up visit. All abnormal signs and symptoms were considered as adverse events. Each adverse event was graded for severity, and assigned causality relative to the study vaccine. Severity was based on the following scale: mild: easily tolerated; moderate: interferes with activities of daily living; and severe: prevents activities of daily living. Erythema and induration at the injection site were graded as follows: mild: >0 to ≤20 mm; moderate: >20 to ≤50 mm; severe: >50 mm. A complete blood count, creatinine, and AST were performed prior to each vaccination, as well as 3 and 14 days after each vaccination.

2.2.4. ELISA

Anti-Pvs25H antibodies were measured in serum by a standardized ELISA. ELISA plates (Immunolon 4; Dynex Technology Inc., Chantilly, VA) were coated with Pvs25H, stored at 4 °C overnight, then blocked with buffer containing 5% skim milk (Difco, Detroit, MI) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (BioFluids, Camarillo, CA) for 2 h at room temperature. Sera, diluted in buffer, were added in triplicate to antigen-coated wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with 0.1% Tween 20 in TBS, plates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-human IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry, Gaithersburg, MD) for 2 h at room temperature. After adding phosphatase substrate solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), absorbance was read at 405 nm.

The ELISA was standardized with a reference antiserum prepared from selected sera obtained 2 weeks after the third immunization (day 194) and assigned a unit value equivalent to the reciprocal of the dilution giving an OD405 of 1. In each ELISA plate, the absorbances of a set of serially diluted reference were fitted to a four parameter hyperbolic function to generate a standard curve. Using this standard curve, the absorbance of an individual test serum was converted to an antibody unit value. Responders were defined as volunteers with antibody greater than 5.4 units (day 0 mean plus 3 standard deviations).

2.2.5. Transmission blocking activity

The membrane feeding assay was performed as described previously [6] with modifications on sera treatment. Sera from the vaccinees were heat inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and incubated with AB+ human erythrocytes (5:1, serum:erythrocytes, v/v) for 20 min at room temperature to remove anti-A and anti-B blood group antibodies. The sera were tested as undiluted samples (denoted as undiluted sera) or diluted 1:1 (v:v) with pooled näıve American human AB sera (Interstate Blood Bank Inc., Memphis, TN) (denoted as diluted sera). The serum pool was not heat inactivated. Thus, the diluted sera contained heat-sensitive components, including complement. A portion of the AB pool was heat inactivated (undiluted AB control) and used as a control for the undiluted sera. A 1:1 mixture of heat inactivated AB pool and non-heat inactivated AB pool (diluted AB control) was used as a control for the diluted sera.

One feeding experiment contained 20 membrane feeders. Of these, 2 contained undiluted AB control, 2 diluted AB control and 16 contained 4 sets of sera. Each set had four samples from one Pvs25H-vaccinated volunteer: undiluted day 180 serum; diluted day 180 serum; undiluted day 194 serum; and diluted day 194 serum. All feeders in a single feeding experiment contained 180 μL of sera and 150 μL of packed erythrocytes from a single consenting P. vivax-infected patient enrolled from malaria clinics in Mae Sod, Thailand. Twenty millilitres of venous blood was obtained once from each consenting patient at the time of malaria diagnosis and treatment. One hundred Anopheles dirus mosquitoes fed for 30 min. Fed mosquitoes were kept for 7–9 days, after which the number of oocysts per midgut were counted. A valid feeding experiment meant mosquitoes fed on the undiluted AB control had to be infected with a mean of >2.5 oocysts per mosquito. Mosquitoes were dissected for each membrane feeder depending on the mean oocyst density (20 mosquitoes if mean oocysts/mosquito ≥4 in undiluted AB control; 40 if mean oocysts/mosquito ≥2.5 to <4). Each set of sera (day 180 and day 194, diluted and undiluted) was tested in three valid feeds, with each set randomly assigned to different feeding experiments to minimize clustering errors.

2.2.6. Statistical procedures

The frequency of adverse events stratified by dose cohort was summarized (SAS Version 8.2, Cary, NC). Differences between the proportion of adverse events of any severity, across dose groups, and across the vaccinations within each dose group were tested for statistical significance with either a Cochran-Armitage Trend Test, or Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel Test using StatXact (Version 6.0, Cytel Software Corp., Cambridge, MA).

The relationship between antibody units and vaccine dose was evaluated using the Spearman rank correlation test. Differences between antibody units on days 42 and 194, 2 weeks after the second and third vaccination, respectively, were compared by the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (UNISTAT 5.0, P-STAT Inc., Hopewell, NJ).

Non-linear regression (SigmaPlot 8.0, SPSS Inc.) was used to fit the transmission blocking inhibition of individual sera to a simple hyperbola as a function of the antibody concentration measured by ELISA. The resulting function was defined by a single estimated parameter, the antibody concentration giving 50% transmission blocking (Ab50).

Probability values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Toxicology

Administration of Pvs25H/Alhydrogel® at 0, 1.25, 20 and 80 μg had no clinically significant adverse effects in immunized New Zealand white rabbits. All laboratory values were within the normal limits for male and female rabbits (Lab-Corp, unpublished). In the female rabbit groups receiving Pvs25H vaccine, no local reactions were observed at any time point. One female rabbit in the placebo group had a local reaction (scored as 1 out of 4) on days 58–61. One male rabbit in the 80 μg Pvs25H group had a mild reaction (2 out of 4) on days 86–91, while all other males had only minimal local reactions (1 out of 4). Rabbits immunized with Pvs25H/Alhydrogel® made significant immune responses to the antigen in a dose-dependent fashion (data not shown).

3.2. Vaccine trial

3.2.1. Study population

Thirty volunteers (18 female and 12 male) were enrolled. The median age was 29 years (range, 22–50); 63.3% identified themselves as Caucasian; 33.3% as African American; and 3.3% (one volunteer) as Hispanic. Twenty-six of 30 vaccinees received all three scheduled vaccinations. All 10 in the 5 μg group received the first and second vaccination as scheduled. Eight received the third vaccination. One volunteer developed hypertension during the study and did not receive the third vaccination, and one volunteer died prior to the third vaccination as a result of an illicit drug overdose. All 10 volunteers in the 20 μg group received all three vaccinations as scheduled. All 10 volunteers in the 80 μg group received the first vaccination as scheduled, nine received the second vaccination and eight received the third vaccination. One volunteer did not receive further vaccinations after the first vaccination due to an elevation in AST (see below); a second volunteer was withdrawn prior to the third vaccination due to noncompliance.

3.2.2. Safety

All vaccinations were well tolerated (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences among the proportion of volunteers with an injection site reaction of any severity, either across the dose groups or across the vaccinations within each dose group. No serious adverse events occurred that were definitely, probably, or possibly related to vaccination. No immediate hypersensitivity reactions were observed, and no changes in vital signs occurred during the 30-min observation period or during follow-up. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. There was one occurrence of injection site tenderness, graded as severe in intensity by a volunteer on her diary card. Severe pain was defined as “pain all the time” on the diary cards. This volunteer had no interruption of her activities of daily living with the pain, and it resolved the day after vaccination without treatment. Fever, defined as oral temperature greater than 37.5 °C (range: 37.5–37.9 °C; median: 37.6 °C), and headache were the most commonly observed systemic reactions (Table 2). All other adverse events were not causally related to the study vaccine.

Table 1.

Local reactogenicity for Pvs25H malaria vaccine

| 5μg | 20μg | 80μg | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Vaccination #1 | ||||||||||||

| Tenderness | 6/10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6/10 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6/10 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Erythema | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Induration | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccination #2 | ||||||||||||

| Tenderness | 8/10 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 6/10 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 5/9 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Erythema | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2/9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Induration | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3/10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3/9 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccination #3 | ||||||||||||

| Tenderness | 4/8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7/8 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Erythema | 1/8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5/10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4/8 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Induration | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5/10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4/8 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Solicited systemic reactogenicity for Pvs25H malaria vaccine

| 5μg | 20μg | 80μg | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Vaccination #1 | ||||||||||||

| Fever | 9/10 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3/10 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Nausea | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccination #2 | ||||||||||||

| Fever | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1/9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1/9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2/9 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccination #3 | ||||||||||||

| Fever | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1/8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 1/8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4/10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3/8 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/8 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 0/8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Adverse events that were classified as either definitely, probably, or possibly related to vaccination only (remotely and unrelated to vaccination not included in this table).

One volunteer in the 80 μg group had an elevation of AST to three times the upper limit of normal for the testing laboratory (AST = 147 U/L; laboratory range: 2–50 U/L for males) on day 3 which resolved by day 28. This volunteer was asymptomatic when the elevation in AST was discovered, but subsequently developed a viral-like illness on day 9. Screening tests had been performed twice in this volunteer prior to initial vaccination. Serology for hepatitis B and C was negative before and after vaccination. Due to the temporal relationship between vaccination and the rise in transaminase levels, no subsequent vaccinations were given. The volunteer was followed for the duration of the trial for safety assessments and remained healthy.

3.2.3. ELISA

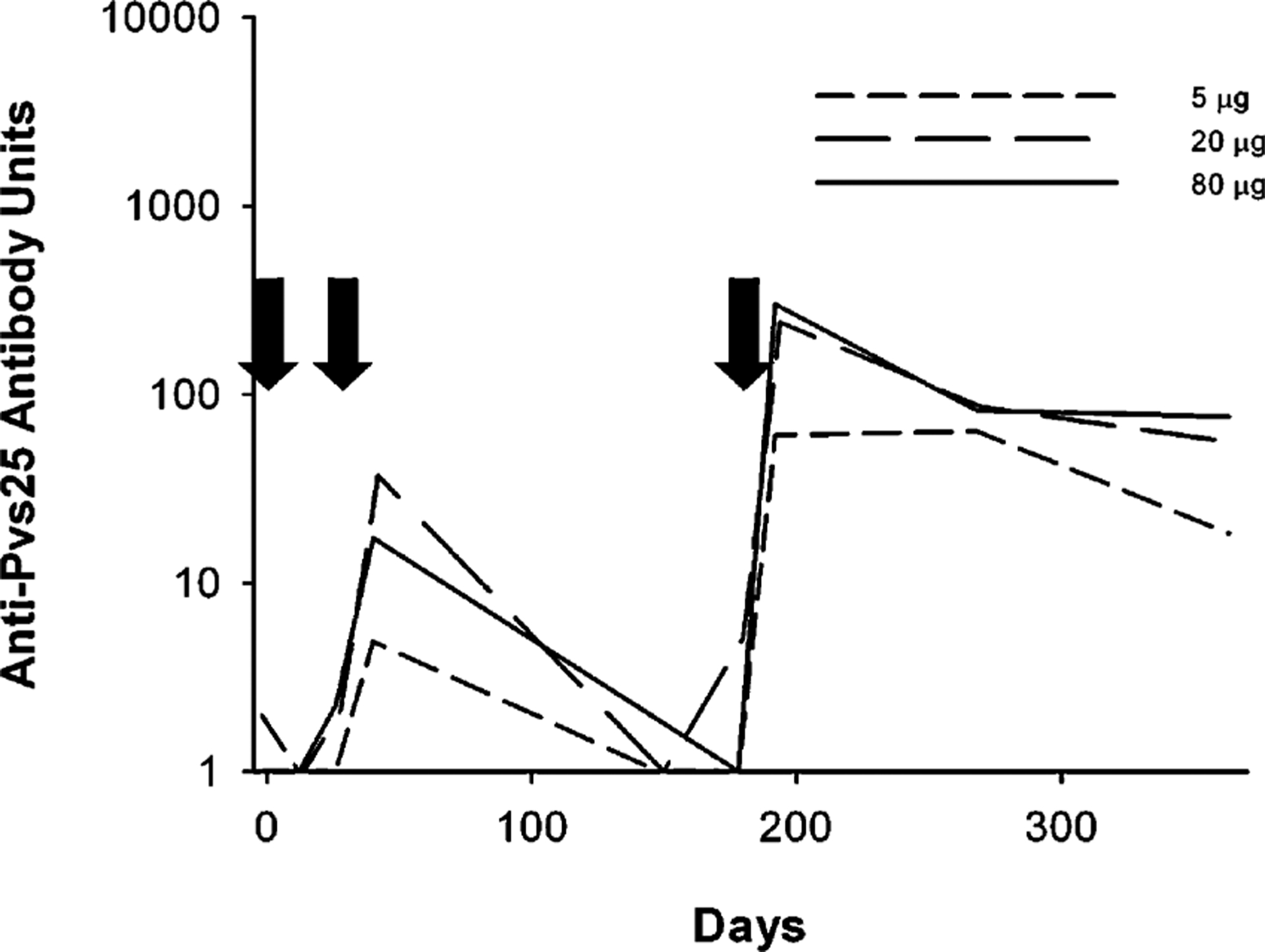

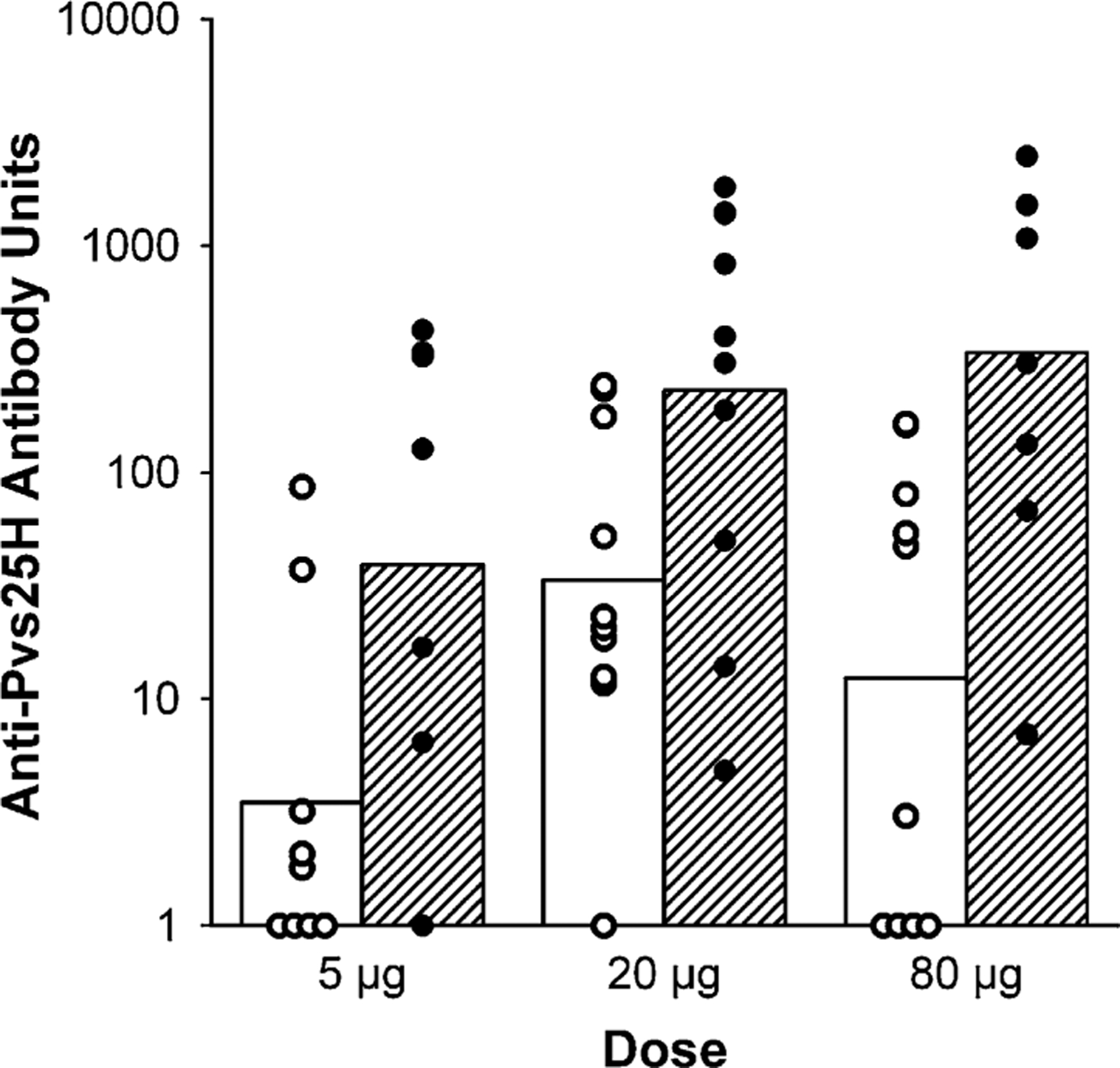

Antibody levels were determined on sera collected on days 0, 14, 28, 42, 150, 180, 194, 270 and 364 (Fig. 1). No volunteer had antibody levels in the day 0 sample greater than 5.4 units (the level defined as a responder). Two weeks after the second immunization (day 42), 12 of 28 volunteers were classified as responders, with the antibody levels declining to baseline by day 150. On day 194 (2 weeks after the third immunization), antibody levels were significantly higher than day 42 values in the groups that received the 20 or 80 μg dose (Wilcoxon signed rank test: P = 0.014 and 0.036, respectively, Fig. 2). After this point, antibody levels decreased but remained measurable in 15 of 25 volunteers on day 364. There was no significant antigen dose–response relationship in sera obtained on day 42 (Spearman rank correlation test, P = 0.120) or on day 194 (P = 0.106).

Fig. 1.

The anti-Pvs25H antibody units for the groups receiving 5 μg (short dashes), 20 μg (long dashes) or 80 μg (solid line) of Pvs25H/Alhydrogel®.Geometric mean values for each group are shown at the sampling points with the standard error of the geometric mean. Arrows indicate the three vaccination days.

Fig. 2.

Individual (circles) and geometric mean (bars) anti-Pvs25H antibody units 2 weeks after volunteers received their second (open circles and open bars) and third (closed circles and hatched bars) vaccination with 5, 20 or 80 μg of Pvs25H/Alhydrogel®.

Antibody units reported in this paper are the reciprocal dilution of sera giving an absorbance of 1. These units are 20- to 50-fold lower than the endpoint titers used in many publications. The highest antibody level of 2475 units measured in this study has an endpoint titer of approximately 100,000.

3.2.4. Transmission blocking activity

In all, 22 valid membrane feeding experiments using infected blood from 12 different P. vivax patients were analyzed to test the days 180 and 194 sera from 27 vaccinees. An additional four membrane feeds failed to yield <2.5 oocysts per mosquito in the control feeds and were not analyzed.

Feeds containing undiluted (i.e. only heat inactivated sera) and diluted sera (50% non-heat inactivated sera) were analyzed separately because the average oocyst densities in mosquitoes fed the heat inactivated sera were substantially lower than those fed mixed inactivated/non-inactivated sera (slope of linear regression of oocysts in mosquitoes fed mixed inactivated/non-inactivated sera compared with fully heat inactivated sera was 0.72, significantly less than slope of 1.0, P = 0.0015).

No difference was found between the oocyst numbers in the diluted AB control feeds or any of the diluted day 180 sera. Similarly, there was no difference between the oocyst numbers in the undiluted AB control or the undiluted day 180 sera (P > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis one way ANOVA). As there was insufficient day 0 sera available for multiple negative controls, and as the days 0 and 180 sera gave similar oocyst densities, the average oocyst number in the two undiluted AB control and the six undiluted day 180 sera within a feeding experiment was calculated as the undiluted control oocyst number for that feed. Similarly, the diluted control oocyst number was calculated from the feeds with diluted AB control and the diluted day 180 sera. The use of day 180 sera may introduce a small error. If there was residual transmission blocking activity in these sera, the inhibition reported for the day 194 sera will be underestimated. The percentage inhibition of oocyst development was calculated as:

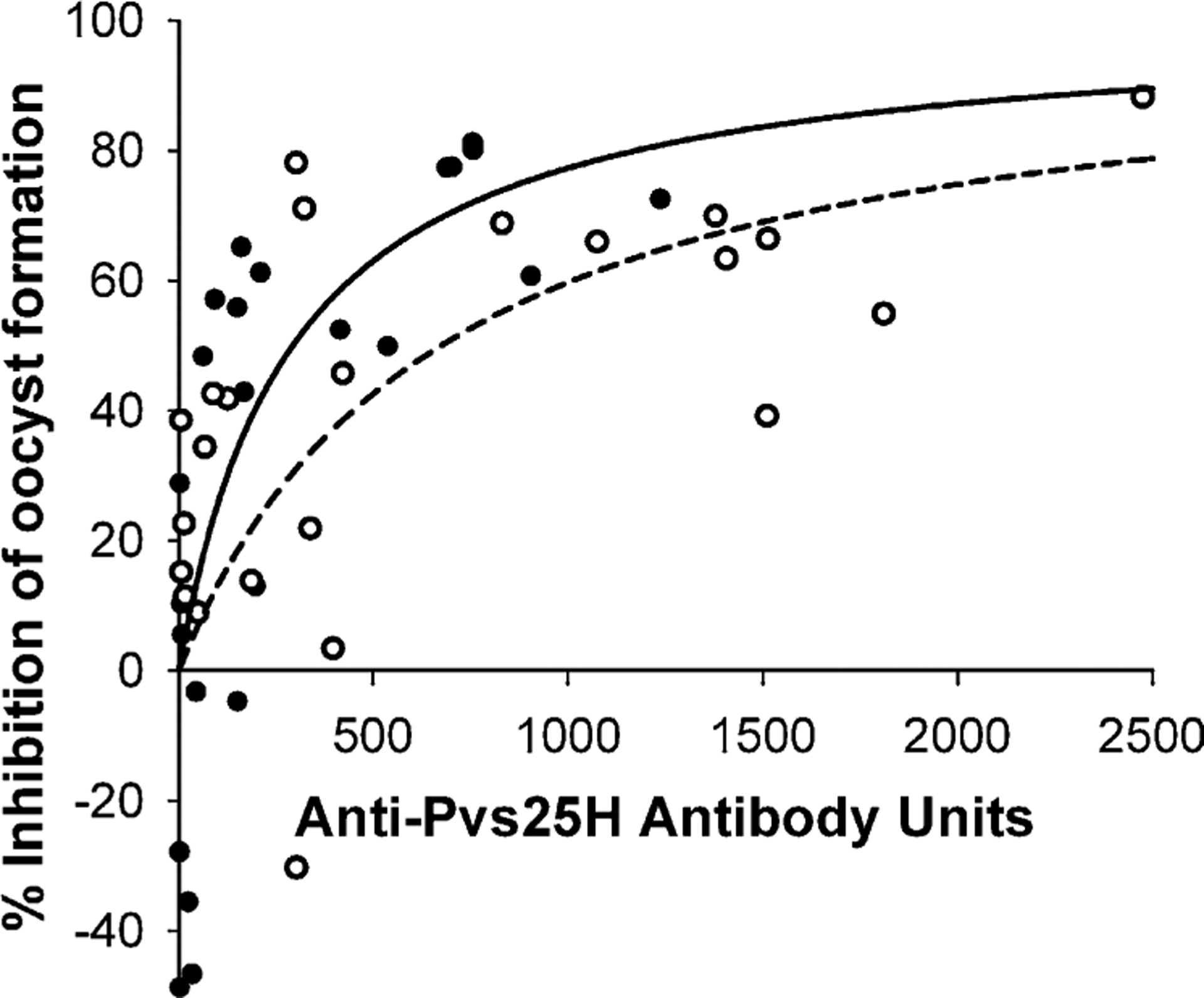

There was a strong correlation between the concentration of antibody in the membrane feeder and the inhibition of oocyst development for undiluted and diluted day 194 sera (Spearman rank correlation rs = 0.64, P = 0.003 and rs = 0.80, P < 0.001 for undiluted and diluted samples, respectively). Consistent with earlier observations from animal sera (Miura et al., unpublished results) both data sets could be fitted to the following simple rectangular hyperbola: %inhibition = 100 × [Ab]/(Ab50 + [Ab]); where [Ab] is the concentration of anti-Pvs25H antibody measured by ELISA and Ab50 is the concentration of antibody giving 50% inhibition (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of anti-Pvs25H antibody units with transmission blocking measured as a %reduction in oocysts per mosquito. The solid line and closed circles are membrane feeds using diluted sera. The dashed line and open circles are membrane feeds using undiluted sera. Lines are the non-linear regression fit of the data to a simple hyperbolic equation.

For the undiluted sera, r2 = 0.37, Ab50 = 674±224 (P = 0.0060). For the diluted sera, r2 = 0.61, Ab50 = 294 ± 90 (P = 0.0034). Therefore, the antibodies in the diluted sera, i.e. in the presence of pooled, unheated naïve human sera, are more effective at killing oocysts. This increased efficacy is after accounting for the lower numbers of oocysts that occur in control mosquitoes fed diluted control sera.

Since there are multiple oocysts on average in each infected mosquito, and the number of oocysts per mosquito varies greatly, it is theoretically more powerful to measure a decrease in the number of oocysts than the decrease in infected mosquitoes. Nevertheless, for the day 194 sera, there was a significant correlation between antibody levels measured by ELISA and an increase in the non-infected mosquitoes (rs = 0.73, P < 0.0001 for samples tested with heat inactivated sera and rs = 0.54, P = 0.0025 for samples tested with sera diluted 1:1 with non-heat inactivated pooled normal sera). The five sera with the highest antibody levels from day 194 gave a 20–30% decrease in the number of infected mosquitoes.

4. Discussion

An important indicator of the success of a Pvs25H vaccine is the ability to demonstrate transmission blocking activity in the immune sera using the membrane feeding assay. This is a technically difficult assay. P. vivax cannot be cultured and thus infected blood from human patients is required. This introduces substantial variation between replicates. This effect was minimized by using multiple replicates and by using several different sources of infected blood for each serum tested.

Although anti-Pvs25H antibodies have been shown to block transmission, the conditions required for reproducibly assaying transmission blocking activity were not well understood. A surprising result of this study was the sensitivity of the assay to heat labile components in the sera. Previous studies on rodent malaria parasites, P. berghei and P. yoelii, indicated that parasite development in the mosquito is inhibited by the complement via the alternative pathway [11,12]. Consistent with these observations, we found that in the absence of anti-Pvs25H antibody, heat labile components in the sera substantially reduced the number of P. vivax oocysts developing in mosquitoes. Thus, we controlled for this variable by using either heat inactivated sera, or heat inactivated sera to which a defined concentration of non-heat inactivated sera had been added.

In previous studies with Pvs25 and orthologs from other malaria species, complement has not been considered an important variable in the assay since Pvs25 expression peaks late in the development of the zygote, and ookinete and complement levels have declined significantly by 5–6 h after ingestion [11] The time at which Pvs25 first appears on the surface of mosquito stage parasites is not known. However, the orthologs, Pbs21 from P. berghei [13] and Pfs25 from P. falciparum [14] are present on the parasites within a few hours of ingestion of the blood meal. The enhanced transmission blocking by anti-Pvs25H antibodies seen in the presence of non-heat inactivated sera suggests that Pvs25 is expressed early enough for antibody mediated activation of complement to contribute to transmission blocking activity. Presumably several mechanisms exist for anti-Pvs25H antibodydependent killing of parasites since significant transmission blocking activity remained in heat inactivated sera.

This Pvs25H vaccine candidate induced little local or systemic reactogenicity in vaccinated volunteers. Local reactogenicity accounted for the most commonly reported adverse events. The vast majority of vaccine-related adverse events were injection site reactions, with injection site tenderness being the most commonly reported. Of the observed adverse events in this trial, there were none identified that would halt development of this vaccine formulation. The lack of safety concerns seen in this study and the generation of transmission blocking activity in humans vaccinated with Pvs25H adjuvanted with Alhydrogel® confirms that Pvs25 is a transmission blocking vaccine candidate. However, higher levels of transmission blocking activity than observed in this study will be needed for a practical vaccine. In animal studies, we have observed substantially higher antibody levels with adjuvants more potent than Alhydrogel®. Thus, the first steps towards an effective vaccine will be to optimize formulation and the vaccination regimen to attain higher antibody levels. Subsequent steps will include combination with other P. vivax and P. falciparum antigens, phase 1 testing in endemic populations in all age groups for safety and immunogenicity, phase 2 testing to assess induction of transmission blocking activity, followed by phase 3 testing to measure community based impact on malaria transmission [15]. This first phase 1 human trial with Pvs25H/Alhydrogel is encouraging and suggests that the goal of an effective transmission blocking vaccine for P. vivax is feasible.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our thanks to the Fermentation, Purification, Quality Control and Immunology Groups at the Malaria Vaccine Development Branch. We are grateful to all trial site personnel, especially John Perreault and Julie McArthur. We are grateful to Dr. Jeeraphat Sirichasinthop (Director, Vector Borne Disease Control Training Center, Thailand) and his staff at the malaria clinics in Tak province for support on recruitment of malaria patients and blood collection. Special thanks to the devoted field and laboratory assistants: Nongnuj Maneechai, Vichit Phunkitchar, Chukree Kiattibut, Chalermpol Kumpitak, Nattawan Rachapaew, Nattapat Nongngork, Koraket Laptaveeshoke, Siriporn Mungviriya and insectary staff at AFRIMS. Lastly, we especially thank our study volunteers.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 3–7 December 2003 (abstract 326).

Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers. The clinical research was performed within the human experimentation guidelines of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and was approved by the Committee on Human Research, Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health and the NIAID Institutional Review Board.

References

- [1].Mendis K, Sina BJ, Marchesini P, Carter R. The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;64(Suppl. 1–2):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Richie TL, Saul A. Progress and challenges for malaria vaccines. Nature 2002;415(6872):694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tsuboi T, Kaslow DC, Gozar MMG, Tachibana M, Cao YM, Torii M. Sequence polymorphism in two novel Plasmodium vivax ookinete surface proteins, Pvs25 and Pvs28, that are malaria transmission-blocking vaccine candidates. Mol Med 1998;4(12):772–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stowers A, Carter R. Current developments in malaria transmission-blocking vaccines. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2001;1(4):619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hisaeda H, Stowers AW, Tsuboi T, Collins WE, Sattabongkot JS, Suwanabun N, et al. Antibodies to malaria vaccine candidates Pvs25 and Pvs28 completely block the ability of Plasmodium vivax to infect mosquitoes. Infect Immun 2000;68(12):6618–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sattabongkot J, Tsuboi T, Hisaeda H, Tachibana M, Suwanabun N, Rungruang T, et al. Blocking of transmission to mosquitoes by antibody to Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine candidates Pvs25 and Pvs28 despite antigenic polymorphism in field isolates. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;69(5):536–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Carter R Transmission blocking malaria vaccines. Vaccine 2001;19(1719):2309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Miles AP, Zhang Y, Saul A, Stowers AW. Large-scale purification and characterization of malaria vaccine candidate antigen Pvs25H for use in clinical trials. Protein Expr Purif 2002;25(1):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zou L, Miles AP, Wang J, Stowers AW. Expression of malaria transmission-blocking vaccine antigen Pfs25 in Pichia pastoris for use in human clinical trials. Vaccine 2003;21(15):1650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Health effects test guidelines. OPPTS 870.2500, Acute dermal irritation. United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances (OPPTS); 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Margos G, Navarette S, Butcher G, Davies A, Willers C, Sinden RE, et al. Interaction between host complement and mosquito-midgutstage Plasmodium berghei. Infect Immun 2001;69(8):5064–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tsuboi T, Cao YM, Torii M, Hitsumoto Y, Kanbara H. Murine complement reduces infectivity of Plasmodium yoelii to mosquitoes. Infect Immun 1995;63(9):3702–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Alejo Blanco AR, Paez A, Gerold P, Dearsly AL, Margos G, Schwarz RT, et al. The biosynthesis and post-translational modification of Pbs21 an ookinete-surface protein of Plasmodium berghei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1999;98(2):163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fries HCW, Lamers MBAC, van Deursen J, Ponnudurai T, Meuwissen JHET. Biosynthesis of the 25-kDa protein in the macrogametes/zygotes of Plasmodium falciparum. Exp Parasitol 1990;71(2):229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carter R, Mendis KN, Miller LH, Molineaux L, Saul A. Malaria transmission-blocking vaccines—how can their development be supported? Nat Med 2000;6(3):241–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]