Abstract

The latency-related transcript (LRT) of bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) is the only abundant viral RNA detected during latency. A previous study (A. Hossain, L. M. Schang, and C. Jones, J. Virol. 69:5345–5352, 1995) concluded that splicing of polyadenylated [poly(A)+] and splicing of nonpolyadenylated [poly(A)−] LRT are different. In this study, splice junction sites of LRT were identified. In trigeminal ganglia of acutely infected calves (1, 7, or 15 days postinfection [p.i.]) or in latently infected calves (60 days p.i.), alternative splicing of poly(A)+ LRT occurred. Productive viral gene expression in trigeminal ganglia is readily detected from 2 to 7 days p.i. but not at 15 days p.i. (L. M. Schang and C. Jones, J. Virol. 71:6786–6795, 1997), suggesting that certain aspects of a lytic infection occur in neurons and that these factors influence LRT splicing. Splicing of poly(A)− LRT was also detected in transfected COS-7 cells or infected MDBK cells. DNA sequence analysis of spliced LRT cDNAs, poly(A)+ or poly(A)−, revealed nonconsensus splice signals at exon/intron and intron/exon boundaries. The GC-AG splicing signal utilized by the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript in latently infected mice is also used by LRT in latently infected calves. Taken together, these results led us to hypothesize that (i) poly(A)+ LRT is spliced in trigeminal ganglia by neuron-specific factors, (ii) viral or virus-induced factors participate in splicing, and (iii) alternative splicing of LRT may result in protein isoforms which have novel biological properties.

All members of the alphaherpesvirus subfamily establish and maintain a latent infection in the peripheral nervous system of their natural hosts. Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1), a member of the alphaherpesvirus subfamily, is an important pathogen of cattle and establishes latent infection in sensory ganglia of infected cattle (reviewed in references 57 and 58). Since neurons are terminally differentiated cells, it may not be necessary for the virus to replicate in these cells to maintain latency. Viral gene expression in latently infected neurons is restricted to the latency-related transcript (LRT). By using in situ hybridization, LRT was detected in trigeminal ganglia (TG) of BHV-1-infected rabbits (55, 56) or cattle (41). These studies mapped the approximate 5′ and 3′ ends of LRT and estimated its length to be 1.15 kb. LRT is also expressed during the late stages of productively infected bovine cells (56). A 41-kDa protein is encoded by the LR (latency-related) gene in transiently transfected cells or infected bovine cells (35). LR gene products inhibit entry of cells into S phase, suggesting that the LR gene regulates some aspect of latency (65).

The latency-associated transcript (LAT) of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has been the subject of intense scrutiny (reviewed in references 4, 9 24, 34, and 80). It is not known if HSV-1 LAT encodes a protein even though LAT is associated with polysomes (28). LAT is a stable 2.0-kb intron (22, 40, 59, 83), and the 1.5- or 1.45-kb transcript is derived from the 2.0-kb LAT by further splicing (71). The splicing event that generates the 1.5-kb LAT utilizes a novel splice donor that is GC instead of GT (71, 74), and this splicing event requires neuron-specific splicing factors (44). Polyadenylation of the spliced 1.5-kb LAT is controversial (18, 50, 52, 70, 79). Disruption of splice donor or acceptor sites prevents synthesis of the 2-kb LAT in productively infected nonneuronal cells but not in latently infected neurons (3).

Although cis-acting sequences that regulate neuron-specific transcription of the BHV-1 LR gene have been studied (10, 11, 17, 37), processing of LRT has not been well characterized. A previous study concluded that LRT is spliced, but splice junctions were not identified (35). In this study, LRT splicing patterns in TG of infected calves were compared to those of productively infected bovine cells or COS-7 cells transfected with a plasmid that expresses LR gene products. We have identified three alternatively spliced poly(A)+ LRT isoforms at 7, 15, or 60 days postinfection (p.i.). A spliced poly(A)− LRT was detected at 1 day p.i., suggesting LRT is expressed early in TG. LRT was spliced in the poly(A)− RNA fraction after bovine cells were infected or after COS-7 cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the LR gene. It is hypothesized that poly(A)+ LRT is alternatively spliced in TG and that these spliced variants have the potential to encode novel proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus, plasmids, and cells.

MDBK (Madin-Darby bovine kidney) cells or COS-7 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) were grown in Earle’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. The Cooper strain of BHV-1 was obtained from the National Veterinary Services Laboratory, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services (Ames, Iowa). MDBK cells were infected with 5 PFU of BHV-1 per cell, and RNA was extracted 24 h p.i.

Plasmid pcDNA1/LRT was constructed by inserting a 2-kb HindIII-SalI fragment which contains the LR gene (35) (Fig. 1) into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA1/Amp (Invitrogen). A SalI site was inserted into the unique XbaI site of pcDNA1/Amp prior to insertion of the LR gene. COS-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA1/LRT by calcium phosphate precipitation (19), and total RNA was prepared 48 h after transfection.

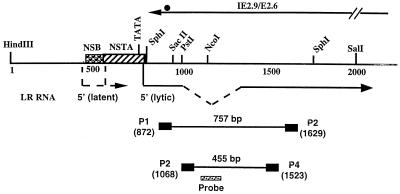

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the LR promoter, locations of 5′ termini of LR transcripts, and partial restriction enzyme map of the LR gene. The 5′ ends of LRT were mapped by RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) PCR or primer extension (11, 35). DNA sequences within the LR promoter which are bound by neuron-specific proteins (NSB) were identified by electrophoretic mobility shift assays and exonuclease III footprinting (17). DNA sequences within the LR promoter which cis activate a minimal tk promoter in neuronal cells are designated as a neuron-specific transcriptional activator (NSTA) (10). Splicing of LR RNA occurs in LRT; this is designated by the dashed lines (35). The transcripts (IE2.9/E2.6) antisense to LRT are indicated by a solid black line, and the circle at the 3′ end of the transcript is the position of the stop codons for the protein encoded by IE2.9/E2.6. The primers P1, P2, P3, and P4 used for amplification of LRT are indicated by small black rectangles. The number below each primer indicates the position of the 5′ terminus. The predicted sizes of the PCR products that can be amplified by these primers are also indicated. The small hatched rectangle indicates the probe used in Southern blot analysis to detect the PCR product. Except for the boxes depicting P1, P2, P3, P4, and the probe, the line map is drawn to scale. Plasmid pcDNA1/LRT contains the 2-kb HindIII-SalI fragment cloned into pcDNA1/Amp as described in Materials and Methods.

Infection of cattle and preparation of tissue samples.

BHV-1-free calves were divided into six groups of two each and then infected with 108.8 50% tissue culture infective doses intranasally and intraocularly as described previously (66). Two animals were used as controls. TG were collected 1, 2, 4, 7, 15, or 60 days p.i. (two calves per time point) or from two uninfected calves. TG were frozen in an ethanol-dry ice bath and stored at −120°C (66). Some of the RNA samples from the cattle described by Schang and Jones (66) were used for these studies.

Preparation of RNA.

Total RNA was extracted from TG as described previously (35). Total RNA from infected or transfected cells was extracted by using the RNAgents Total RNA Isolation system (catalog no. Z5110; Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were measured in a spectrophotometer at 260 nm.

Preparation of poly(A)+ and poly(A)− LRT RNA by oligo(dT) chromatography.

Poly(A)+ RNA was prepared by using an mRNA purification kit (catalog no. 27-9258; Pharmacia) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was passed through an oligo(dT)-cellulose column twice, and the column was washed with a buffer supplied in the kit. Bound RNA was recovered by incubating the column with 250 μl of elution buffer at 65°C, and RNA was subsequently precipitated with ethanol. RNA in the flowthrough fraction of the oligo(dT) column [designated poly(A−)] was recovered and precipitated with ethanol.

Primers for RT-PCR.

Figure 1 shows the design of primers used for reverse transcriptase (RT)-mediated PCR (RT-PCR) and location of the hybridization probe. LRT was detected by using primers P1 (same sense as LRT 5′-AGGCTGGGGGTCGCAAATACACGGC-3′) and P2 (antisense to LRT 5′-GGCCCGCCGGAGAAGAAGGACAGAGT-3′), which amplify a 757-bp fragment. With primers P3 (same sense as LRT 5′-CCCCAGGAGGCTTTCTCGCACC-3′) and primer P4 (antisense to LRT 5′-CACAGTGATAGACCTGACGGCGAACG-3′), spliced LRT was amplified. The probe used for detection of LRT cDNA was from nucleotides (nt) 1092 to 1117 (5′-GCGCACCGAAATGGAAGTGGCCGCC-3′). The numbering system for the LR gene was described previously (41) and is based on the Cooper strain of BHV-1. The 3′ termini of primers P1, P2, P3, and P4 correspond to positions 872, 1629, 1068, and 1523, respectively. The primers were designed based on the following criteria: (i) the oligonucleotides are located adjacent to an AT-rich region, (ii) the oligonucleotides have a GC content greater than 50%, (iii) there is no significant similarity to other viral genes, and (iv) PCR product size is more than 300 bp.

RT-PCR and sequence analysis of cDNAs.

The method for RT-PCR was described previously (14). Prior to cDNA synthesis, RNA was treated with 1 U of DNase I (GIBCO-BRL) to eliminate contaminating DNA (20). Five hundred nanograms of DNase I-treated poly(A)+ or 3 μg of poly(A)− RNA was denatured at 65°C for 7.5 min, incubated at room temperature with 1 μg of oligo(dT) or random primers (Invitrogen) for 15 min, and then incubated on ice. This mixture was incubated with 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (GIBCO-BRL) in the presence of 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for synthesis of cDNA. RT was inactivated by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Amplification of cDNA was conducted with 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase and 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates in a 50-μl reaction. Forty cycles of amplification were carried out with primers P1 and P2 (200 ng of each) in the presence of 10% glycerol to improve denaturation of GC-rich DNA and to enhance the extension through secondary structures (68) on a DNA thermal cycler (Hybaid). The following conditions were used for amplification: 1 min at 94°C (denaturation), 2 min at 55°C (annealing), 2 min at 72°C (polymerization), and 7 min at 72°C to complete the extension. The PCR products were then reamplified with primers P3 and P4 (200 ng of each) under the same conditions. To avoid contamination, PCR was performed in a separate room, gloves were changed frequently, all reagents were used exclusively for these studies, and numerous other precautions were taken to avoid contamination (32). Amplified products were purified either by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or by selective precipitation (62). Briefly, 0.1 volume of 10× STE (1 M NaCl, 200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM EDTA) was added to PCR products, followed by addition of equal amounts of 4 M ammonium acetate, and precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol at room temperature. Purified PCR products were cloned into pCR-Script vector (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both strands of the inserts were sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method using the Fidelity DNA sequencing system (catalog no. 57600; Oncor), which is designed for sequencing GC-rich DNA. As a positive control, BHV-1 DNA was used. Negative controls included RNA from TG of uninfected calves, mock-infected MDBK cells, or mock-transfected COS-7 cells.

Southern blot analysis.

PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and transferred onto Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham) by capillary transfer according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Hybridization was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The probe was prepared by end labeling with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham).

RESULTS

Amplification of LRT splice junction sites by RT-PCR.

A previous study (35) demonstrated that splicing of LRT occurred, but splice junction sites were not identified. To further study splicing of LRT, RT-PCR was conducted because this approach has been used successfully to identify alternative splicing of other primary transcripts (15, 23, 54). To this end, total RNA from TG of infected calves was used. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified by oligo(dT) chromatography. No attempts were made to prove how efficient the purification procedure was because unnecessary manipulation of TG RNA increases the probability of degradation. To avoid amplification of contaminating viral DNA, total RNA was treated with DNase I. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized by using an oligo(dT) primer, RT, and conditions which allow for optimal amplification of LRT. The resulting cDNA was then amplified in a nested PCR using the primers shown in Fig. 1. The rationale for using nested PCR is that (i) primers P1 and P2 are adjacent to the transcription start sites (11) and the poly(A) signals (41), (ii) primers P3 and P4 flank the region which was spliced (35), and (iii) this strategy enables detection of small amounts of LRT. Although these primers will amplify the IE2.9/E2.6 mRNA, this region of the RNA is not spliced (82), and thus the amplified product migrates with the same mobility as genomic DNA (data not shown).

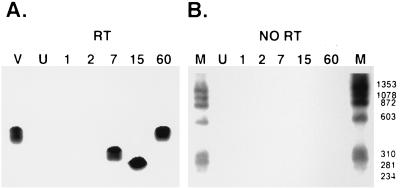

Poly(A)+ LRT was detected in bovine TG at 7, 15, or 60 days p.i. (Fig. 2A). A previous study demonstrated that infectious virus was detected in ocular swabs at 2, 4, or 7 days p.i. but not 15 or 60 days p.i. (66). Alternative splicing apparently occurred in TG during acute infection because amplified products detected at 7 or 15 days p.i. were smaller than amplified LR DNA or LRT cDNA at 60 days p.i. Amplified products were not detected when RT was excluded from the cDNA synthesis (Fig. 2B) or when RNA was prepared from TG of an uninfected calf (Fig. 2A, lane U).

FIG. 2.

Detection of splicing in poly(A)+ LR RNA in TG of infected cattle. The cDNA reaction containing RT was subsequently amplified by using the LRT-specific primers in the nested PCR (A). Lane V, BHV-1 genomic DNA used as an unspliced target; lane U, RNA from TG of an uninfected calf. Numbers above the lanes indicate the days p.i. at which RNA was prepared from TG. φ174 DNA which was digested with HaeIII was used as a molecular weight marker, and the positions of the bands are listed as base pairs. RNA samples were incubated in the standard RT reaction, but RT was omitted and then the nested PCR was performed (B). The lanes are labeled as in panel A. PCR products were detected by Southern blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

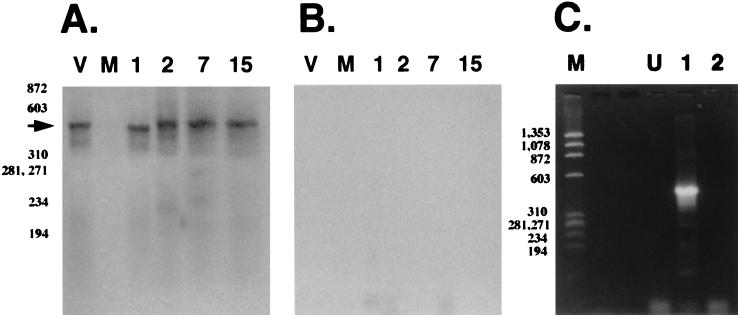

The flowthrough from the oligo(dT) column [poly(A)− RNA] was subjected to cDNA synthesis using random primers and nested PCR to detect LRT. A 455-bp PCR product was detected by Southern blot analysis using the LRT-specific probe described in Fig. 1 (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 7, and 15). Amplified products were not detected when RT was omitted from the cDNA synthesis reaction (Fig. 3B). Poly(A)− LRT was also detected at 1 day p.i. (Fig. 3A, lane 1), and the PCR product appeared to be slightly smaller than genomic viral DNA. Furthermore, poly(A)− LRT from latently infected animals (60 days p.i.) migrated as a 455-bp amplified product (Fig. 3C, lane 1), and the specificity of the amplified product was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization (data not shown). As expected, amplified products were not observed when RT was left out of the cDNA synthesis reaction (Fig. 3C, lane 2). RNA from TG of a second set of infected calves yielded similar bands (data not shown). In summary, these results demonstrated that (i) alternative splicing of poly(A)+ LRT occurred in TG during acute infection, (ii) splicing of poly(A)− LRT apparently occurred at 1 day p.i., and (iii) splicing of poly(A)− LRT in TG at 2, 7, 15, or 60 days p.i. was not readily detected.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of poly(A)− LR RNA. (A) Southern blot analysis of PCR-amplified products derived from the reaction performed with RT. BHV-1 genomic DNA was used as a positive control (lane V). Lane M, RNA from an uninfected calf. Numbers above the lanes indicate RNA prepared from TG which were obtained at different days p.i. The arrow indicates the position of LRT. (B) Southern blot analysis of PCR products derived from the reaction performed without RT. Water was used as a negative control (lane V). The remainder of the lanes are labeled as described for panel A. φ174 DNA digested with HaeIII was used as a marker, and the positions of the bands are designated in base pairs. (C) Amplification of poly(A)− LR RNA from latently infected calves (60 days p.i.). Lane M, φ174 DNA digested with HaeIII; lane U, RNA prepared from TG of an uninfected calf; lane 1, reaction with RT and LRT cDNA subsequently amplified; lane 2, reaction without RT followed by PCR to amplify LRT cDNA.

Analysis of LRT synthesized in transfected or infected cells.

A protein product was identified in COS-7 cells transfected with the LR gene or after MDBK cells were infected (35, 65). In this study, splicing of LRT was investigated after COS-7 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing LR gene products or after MDBK cells were infected with BHV-1. Total RNA was extracted 48 h after transfection or 24 h after infection. Following DNase I treatment, poly(A)+ RNA was used as a template to synthesize single-stranded cDNA with an oligo(dT) primer, and LRT cDNA was amplified. Although poly(A)+ LRT was detected in transfected or infected cells, spliced poly(A)+ LRT was not detected, as judged by the size of the PCR product (Fig. 4A, lane 2 or 5). A previous study detected small amounts of spliced poly(A)+ LRT in infected MDBK cells (35). Although the results in Fig. 4A appear to be at odds with that conclusion, the RNA used for this study was purified by oligo(dT) chromatography. Thus, we hypothesize that either the spliced poly(A)+ LRT was degraded during purification, the poly(A) tail was too short to be stably bound on an oligo(dT) column, or the use of a strand-specific primer in the previous study (35) allowed detection of small amounts of spliced poly(A)+ LRT in infected MDBK cells.

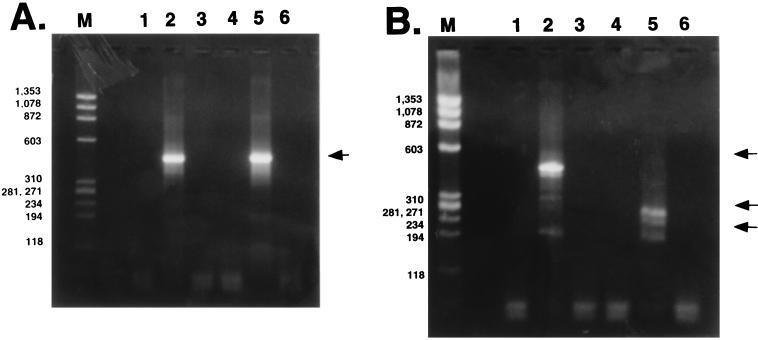

FIG. 4.

Analysis of LRT expressed in transfected COS-7 or infected MDBK cells. (A) PCR amplification of poly(A)+ LRT from transfected or infected cells. Lane M, φ174 DNA digested with HaeIII; lane 1, RNA prepared from untransfected COS-7 cells; lanes 2 and 3, reactions with (lane 2) and without (lane 3) RT, using poly(A)+ LRT prepared from COS-7 cells transfected with pcDNA1/LRT; lane 4, RNA prepared from uninfected MDBK cells; lanes 5 and 6, reactions with (lane 5) and without (lane 6) RT, using poly(A)+ LRT prepared from MDBK cells which were infected for 24 h. The arrow indicates the position of LRT. (B) PCR amplification of poly(A)− LRT from transfected or infected cells. Lanes are as in panel A. The top arrow indicates the position of unspliced LRT, and the bottom arrows indicate the positions of spliced LRT. Sizes are indicated in base pairs.

When cDNA synthesis of poly(A)− RNA was primed with a random primer and LRT cDNA was amplified by nested PCR, bands smaller than amplified BHV-1 DNA (455 bp) were detected (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 5). poly(A)− RNA which was prepared from productively infected cells yielded amplified products migrating as 280-, 240-, or 200-bp fragments (Fig. 4B, lane 5). In contrast, poly(A)− RNA in transiently transfected COS-7 cells contained bands migrating as 455-, 300-, or 200-bp fragments (Fig. 4B, lane 2). All of the amplified products hybridized to the LR-specific probe described in Fig. 1 (data not shown). No PCR products were observed when RT was left out of the cDNA synthesis reaction (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 3 and 6). Unspliced poly(A)− LRT was also detected in transfected cells because a 455-bp band was amplified (Fig. 4B, lane 2). Plasmid pcDNA1/LRT does not contain the IE2.9/E2.6 gene, demonstrating that LRT can be spliced in the absence of any other known viral gene and a subset of LRT was not spliced. In summary, these results indicated that poly(A)− LRT was spliced in MDBK cells after infection or when COS-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA1/LRT.

Sequencing of cloned fragments spanning LRT splice sites.

Although it was possible to sequence the PCR products directly, they were cloned into the pCR-Script vector prior to DNA sequencing. This approach was used in an attempt to identify minor splice site variants and to enhance selection of full-length products. Purified PCR products shown in Fig. 2A, 3A and C, and 4B were cloned into pCR-Script vector. A fragment migrating as a 200-bp fragment was the only band less than 455 bp which was able to be cloned from transfected COS-7 cells or infected MDBK cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 5). Prior to DNA sequencing, plasmids were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion to verify that the inserts were similar in size to the amplified products. Less than 2% of the plasmids had different-size inserts, suggesting that most of the PCR products were not deleted during cloning. DNA sequence of these variants did not match the published LRT gene sequence, indicating they were rearranged during cloning or were not bona fide LRT cDNAs. In contrast, fragments migrating at the expected position of the amplified product yielded DNA sequence which matched the LR gene sequence with an interruption in the middle. The 455-bp PCR product matched the known sequence of the LR gene but did not contain an interruption and thus was not spliced. Figure 5 shows representative examples of the DNA sequence spanning splice junction sites at 1, 7, or 15 days p.i. from TG. At least 10 independent clones were sequenced for each time point, and they yielded the same sequence (locations of splice sites are summarized in Fig. 6).

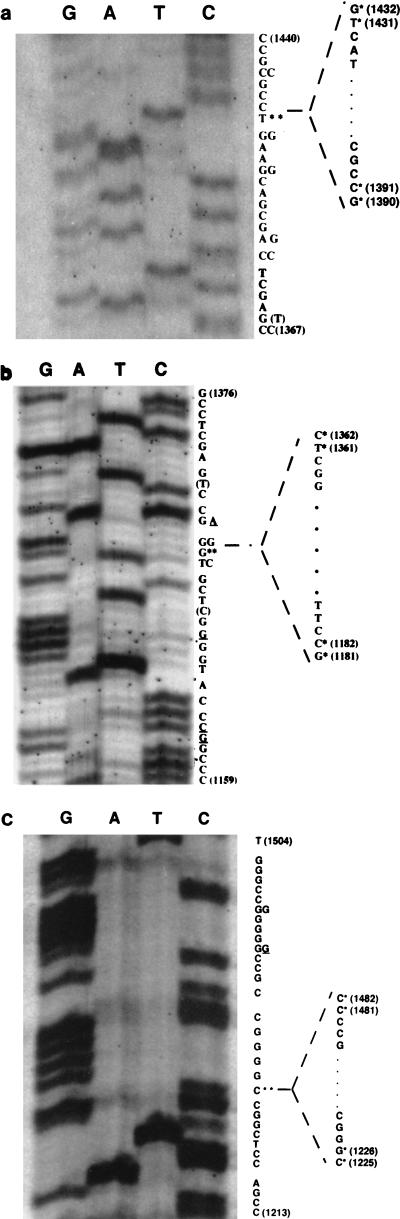

FIG. 5.

Determination of DNA sequences of the LRT splice junctions. The splice junction site was amplified with primers as described in Fig. 1. The sequence presented on the right is the sense strand. Double asterisks mark the splice sites of LRT and the sequence which was spliced out (41). The 5′ and 3′ splice sites are marked with asterisks. The nucleotides that differ from the published LR gene sequence (41) are underlined. The nucleotides in parentheses (T at position 1368 in panel A and C and T at positions 1173 and 1368, respectively, in panel B) were detected in this study but not in the previous study (41). (A) 1 day p.i.; (B) 7 days p.i.; (C) 15 days p.i.

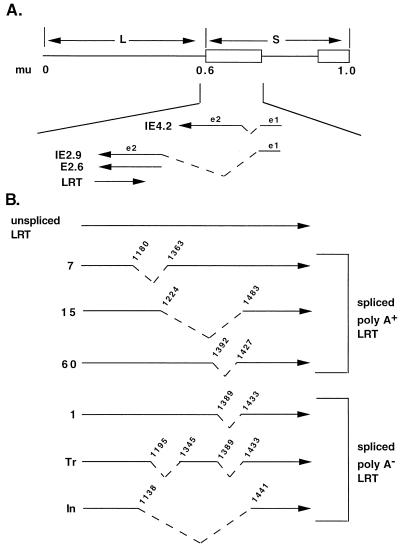

FIG. 6.

Summary of spliced poly(A)+ or poly(A)− LRT. (A) Schematic of BHV-1 genome, positions of repeats, and positions of map units (mu). Locations of immediate-early transcripts with respect to LRT are shown (82). Introns of immediate-early transcripts are presented as dashed lines. Exons are listed as e1 and e2. The e1 of IE2.9 and that of IE4.2 are identical but not protein coding. The E2.6 transcript does not contain e1, and transcription initiates from a novel promoter at the 5′ terminus of e2. Consequently, the proteins encoded by IE2.9 and E2.6 are identical. (B) Alternatively spliced variants of LRT. The numbers on the left indicate that RNA was prepared from TG of calves infected for 1, 7, 15, or 60 days. Tr, spliced LRT which was synthesized in COS-7 cells after transfection with pcDNA1/LRT; In, spliced LRT which was synthesized in MDBK cells infected with BHV-1 for 24 h. Numbers above the lines indicate the 5′ and 3′ boundaries of the intron. The schematic in panel A is not drawn to scale with respect to panel B.

Regardless of whether LRT was poly(A)+ or poly(A)−, splice sites did not match consensus 5′ or 3′ splice sites (Table 1). The 5′ splice sites of poly(A)+ LRT at 60 days p.i. were GC, and they match the 5′ splice site of HSV-1 LAT (71, 74), duck α-globin, or bovine aspartyl protease (reviewed in references 36 and 47). The 5′ GC splice site was also identified at the second exon/intron border in transiently transfected COS-7 cells. The remainder of the 5′ splice sites were CG, and to date no transcript has been identified with this splice donor. Except for the 3′ TC splice site identified at 7 days p.i., the remainder of the 3′ splice sites have been described for other mRNAs. The 3′ TG splice site identified at 1 day p.i. or in transfected cells (second 3′ splice site) is present in the 3′ splice acceptor site of human or Drosophila melanogaster α subunit of guanine nucleotide-binding protein (39, 53). The 3′ CC splice site observed at 15 days p.i. in transfected COS-7 cells (first 3′ splice site) or infected MDBK cells was described for yeast HAC1 mRNA (67). HAC1 and D. melanogaster α subunit of guanine nucleotide-binding protein RNAs are alternatively spliced (39, 67). Finally, the 3′ AG splice site present at 60 days p.i. matches HSV-1 LAT (71, 74). In summary, these studies indicated that (i) in TG of latently infected calves, the 5′ and 3′ splice sites of LRT match HSV-1 LAT; and (ii) most of the nonconsensus splice sites are utilized by other mRNAs.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the 5′ and 3′ splice junctions observed in poly(A)+ and poly(A)− LR RNAsa

| RNAb | Sequence

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 5′ splice site | 3′ splice site | |

| Poly(A)+ LRT | ||

| 7 | CTG:GCCTTC | GTAACAGCGGGGCTC:GGC |

| 15 | GCC:CGGGCG | GCCGAGGCCGGCCCC:GGG |

| 60 | GGT:GCCGCC | CCGCCGCGGCGGCAG:TTA |

| Poly(A)− LRT | ||

| 1 | GGT:GCCGCC | CGGCGGCAGTTACTG:CCG |

| Tr | GGC:CGGGGT | GTGCTGGTAGCCGCC:GCG |

| GGT:GCCGCC | CGGCGGCAGTTACTG:CCG | |

| In | TCT:CGGGGC | GTTACTGCCGCCGCC:GCG |

| mRNA consensus | (−3)A/CAG:GTA/GAGT(+5) | (−15)T/C11NC/TAG:NNN(+3) |

The underlined sequences represent the splice signals. The sequences matched to the consensus splice sites are indicated by italicized letters.

Numbers indicate the LR RNA obtained from TG of infected cattle at the indicated days p.i. Tr and In indicate LR RNA from transfected and infected cells.

Effects of splicing on LR ORFs.

The LR gene contains two open reading frames (ORFs) and two reading frames without an initiating methionine. One reading frame without an initiating methionine is contained after the three in-frame stop codons of ORF 2, and the other is in reading frame C. Each spliced LRT isoform was examined to determine the effect of splicing on the ORFs. A fusion between ORF 2 and ORF 1 was generated by splicing at 7 days p.i. in infected MDBK cells or transfected COS-7 cells (Fig. 7). However, these putative proteins would not be identical because the splice junction signals are different. At 15 days p.i., the stop codons at the 3′ end of ORF 2 were removed and fused to the reading frame which is in frame with ORF 2 (Fig. 7). At 1 day or 60 days p.i., the ORFs were organized in a similar fashion (Fig. 7). Interestingly, at 1 or 60 days p.i., a new ORF which is a fusion between reading frame C and ORF 1 is generated (Fig. 7). When ORF 2 is fused to ORF 1 (7 days p.i., infected or transfected cells) or to reading frame B (15 days p.i.), the predicted molecular masses of these proteins were 35 to 45 kDa. This finding agrees with previous conclusions that the P2 antibody directed against the amino terminus of LR ORF 2 recognizes a 40-kDa protein (35, 65). Although we do not know if these proteins are expressed in neurons, these studies suggest that alternative splicing of LRT has the potential to generate novel proteins.

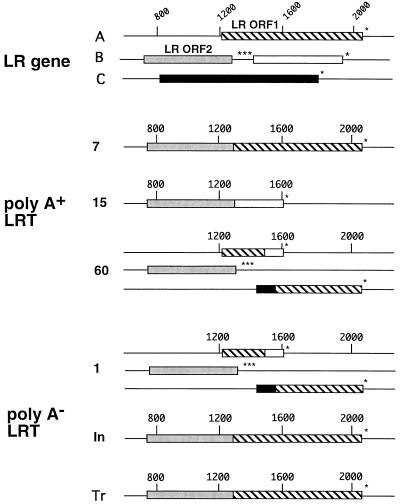

FIG. 7.

Organization of ORFs in the LR gene or in alternatively spliced LRT isoforms. The organization of ORFs in the LR gene was described originally by Kutish et al. (41). The reading frame in B (open box) that follows LR ORF 2 (stippled box) does not contain a methionine at its amino terminus. The reading frame in C (black box) does not contain a methionine at its amino terminus. Asterisks indicate the positions of in-frame stop codons. The hatched box denotes ORF 1. Numbers at the top indicate nucleotide positions, and those on the left indicate that RNA was prepared from TG of calves infected for 1, 7, 15, or 60 days. Tr, LRT synthesized in COS-7 cells transfected with pcDNA1/LRT; In, LRT synthesized in MDBK cells infected with BHV-1 for 24 h. The sequence of each LRT variant was analyzed and translated by using the IBI MacVector sequence analysis software (Kodak).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that alternative splicing of LRT occurred in bovine TG compared to nonneural cells. Several conclusions were drawn from the sequencing data: (i) poly(A)+ LRT in bovine TG at 7 days p.i. was spliced differently than at 15 or 60 days p.i., (ii) poly(A)− LRT detected in bovine TG at 1 day p.i. was not the same as LRT detected at 7, 15, or 60 days p.i., (iii) poly(A)+ LRT in transfected or infected cells which migrated with viral genomic DNA was not spliced, (iv) poly(A)− LRT was spliced in productively infected MDBK cells, and (v) poly(A)− LRT was apparently spliced at two positions in transiently transfected COS-7 cells. Although DNA sequence analysis of splice junction sites suggested that samples from different times p.i. contained one spliced product, the procedures used for amplifying and cloning splice junction sites would yield the major spliced product. It is also possible that at other times p.i., different spliced versions of LRT exist or certain splice variants were not stably cloned. The finding that nonconsensus splice sites were utilized suggests that splicing was regulated by a combination of cell-specific and viral or virus-induced factors.

Several LRT introns are smaller than the 80-nt minimum intron size which has been proposed for eukaryotes (81). For example, we detected a 35-nt intron at 60 days p.i. in TG, a 44-nt intron at 1 day p.i. in TG, and a 44-nt intron in transiently transfected COS-7 cells. The ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia has introns which are 20 to 33 nt long, and these introns have consensus eukaryotic splice signals, G(T/A)G (21, 60). Most fungi or insects, including Drosophila, have introns which range in size from 31 to 70 nt (51, 61, 73; reviewed in references 31 and 48)). More importantly, the polyomavirus small tumor antigen transcript contains a 48-nt-long intron which is excised by a novel mechanism (27), demonstrating that small introns can be excised in mammalian systems. We hypothesize that cis-acting sequences within LRT regulate alternative splicing and mediate excision of short introns. The three in-frame stop codons at the C terminus of ORF 2 (reference 41 and Fig. 7) may be important for alternative splicing because it is known that multiple in-frame stop codons influence cell-specific splicing (2). Although splicing of LRT has unusual features (intron length and nonconsensus splicing signals, for example), there is precedence for unusual introns in a variety of organisms.

Splicing is regulated by a complex array of trans-acting factors, some of which are cell or tissue specific (reviewed in references 12 and 42). Although 5′ splice signals are usually recognized by small ribonucleoprotein complexes (snRNPs) which contain the U1 small nuclear RNA (reviewed in references 5 and 8), introns containing nonconsensus splice sites are frequently spliced by less abundant snRNPs (30, 75, reviewed in reference 69). Serine/arginine (SR) proteins are also important for selection of 5′ and 3′ splice sites (reviewed in references 13, 25, 45, 49, and 78). Adenovirus (33, 38), bovine papillomavirus (84), and HSV-1 (46, 63) alter the distribution or activity of SR proteins. Neuron-specific or brain-specific alternative splicing of specific mRNAs has frequently been observed (1, 6, 7, 44, 72, 77). A neuron-specific splicing regulator (KSRP) is crucial for neuron-specific splicing of c-src (43; reviewed in reference 29). Finally, alternative splicing of HSV-1 LAT occurs in neural cells (44) or murine TG (3), suggesting that neuron-specific splicing has functional significance.

Latency has conveniently been divided into three distinct steps: (i) establishment, (ii) maintenance, and (iii) reactivation. The finding that LRT is alternatively spliced during establishment (1 to 15 days p.i.) relative to maintenance (60 days p.i.) suggests that LR gene products have specialized functions which are necessary for the various stages of latency. During establishment of latency, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a viral function represses viral gene expression and enhances neuronal survival. BHV-1 gene expression in TG, early or immediate-early, is detected as early as 2 days p.i. and peaks at 7 days p.i. (66). Spliced LRT was detected at 1 day p.i. in TG, suggesting that it accumulates prior to productive viral gene expression and thus participates in establishment of latency. HSV-1 LAT promotes establishment of latency (64, 76) in mice by repressing productive viral gene expression (16, 26), adding support to the hypothesis that the LR gene plays a role in establishment. During maintenance of latency, promoting neuronal survival would still be important but repression of viral gene expression does not appear to be as important. A viral function which promotes viral gene expression or DNA replication but prevents neuronal death would be advantageous during reactivation from latency. A number of studies have concluded that HSV-1 LAT mutants do not reactivate from latency efficiently in vivo (reviewed in references 57 and 58), but the mechanism by which LAT functions in this capacity is unknown. Although it is unlikely that LRT regulates every aspect of latency, we hypothesize that alternative splicing of LRT yields novel proteins with specialized functions and that these protein isoforms are important for certain steps of latency. Cloning and characterizing the various LRT cDNAs should allow a better understanding of how LR gene products regulate latency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Luis Schang and Maria Teresa Winkler for assisting with the animal studies and preparing RNA from TG. We appreciate suggestions made by Harikrishna Nakshatri (IU Medical Center) and Stephen Mount (University of Maryland) for advice on nonconsensus splice sites and on intron lengths. Finally, we thank Ruben Donis for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants 9402117, 9502236, and 9702394 from the USDA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amara S G, Jonas V, Rosenfeld M G. Alternative RNA processing in calcitonin gene expression generates mRNAs encoding different polypeptide products. Nature. 1982;298:240–244. doi: 10.1038/298240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoufouchi S, Yelamos J, Milstein C. Nonsense mutations inhibit RNA splicing in a cell-free system: recognition of mutant codon is independent of protein synthesis and tissue specific. Cell. 1996;85:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur J L, Everett R, Brierley I, Efstathiou S. Disruption of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites flanking the major latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1: evidence for alternate splicing in lytic and latent infections. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:107–116. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett J L, Gilden D H. The molecular genetics of herpes simplex virus latency and pathogenesis: a puzzle with many pieces still missing. J Neuro-Virol. 1996;2:225–229. doi: 10.3109/13550289609146884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berget S M. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2411–2414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black D L. Does steric interference between splice sites block the splicing of a short c-src neuron-specific exon in non-neuronal cells? Genes Dev. 1991;5:389–402. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black D L. Activation of c-src neuron-specific splicing by an unusual RNA element in vivo and in vitro. Cell. 1992;69:795–807. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90291-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black D L. Finding splice sites within a wilderness of RNA. RNA. 1995;1:763–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Block T M, Hill J M. The latency associated transcript (LAT) of herpes simplex virus: still no end in sight. J Neuro-Virol. 1997;3:313–321. doi: 10.3109/13550289709030745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bratanich A C, Jones C. Localization of cis-acting sequences in the latency-related promoter of bovine herpesvirus 1 which are regulated by neuronal cell type factors and immediate-early genes. J Virol. 1992;66:6099–6106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6099-6106.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bratanich A C, Hanson N, Jones C. The latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1 inhibits the activity of immediate-early transcription unit 1. Virology. 1992;191:988–991. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90278-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chabot B. Directing alternative splicing, cast and scenarios. Trends Genet. 1996;12:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandler S D, Mayeda A, Yeakley J M, Krainer A R, Fu X-D. RNA splicing specificity determined by the coordinated action of RNA recognition motifs in SR proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3596–3601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chelly J, Kahn A. RT-PCR and mRNA quantitation. In: Mullis K B, et al., editors. The polymerase chain reaction. Boston, Mass: Birkhauser; 1994. pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chelly J, Hamard G, Koulakoff A, Kaplan J C, Kahn A, Berward-Netter Y. Dystrophin gene transcribed from different promoters in neuronal and glial cells. Nature. 1990;344:64–65. doi: 10.1038/344064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen S-H, Kramer M F, Schaffer P A, Coen D M. A viral function represses accumulation of transcripts from productive-cycle genes in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1997;71:5878–5884. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5878-5884.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delhon G A, Jones C. Identification of DNA sequences in the latency related promoter of bovine herpes virus type 1 which are bound by neuronal specific factors. Virus Res. 1997;51:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devi-Rao G B, Goodart S A, Hecht L S, Rochford R, Rice M K, Wagner E K. Relationship between polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts. J Virol. 1991;65:2179–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2179-2190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devireddy L R, Kumar K U, Pater M M, Pater A. Evidence for a mechanism of demyelination by human JC virus: negative transcriptional regulation of RNA and protein levels from myelin basic protein gene by large tumor antigen in human glioblastoma cells. J Med Virol. 1996;49:205–211. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199607)49:3<205::AID-JMV8>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dilworth D D, McCarrey J R. Single-step elimination of contaminating DNA prior to reverse transcriptase-PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;1:279–282. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupuis P. The beta-tubulin genes of Paramecium are interrupted by two 27 bp introns. EMBO J. 1992;11:3713–3719. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrell M J, Dobson A T, Feldman L T. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is a stable intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:790–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feener C A, Koenig M, Kunkel L M. Alternative splicing of human dystrophin mRNA generates isoforms at the carboxy terminus. Nature. 1989;338:509–511. doi: 10.1038/338509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser N W, Block T M, Spivack J G. The latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus: RNA in search of function. Virology. 1992;191:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90160-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu X-D. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA. 1995;1:663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber D A, Schaffer P A, Knipe D M. A LAT-associated function reduces productive-cycle gene expression during acute infection of murine sensory neurons with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:5885–5893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5885-5893.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge H, Noble J, Colgan J, Manley J L. Polyoma virus small tumor antigen pre-mRNA splicing requires cooperation between two 3′ splice sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3338–3342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg D, Mador N, Ball M J, Panet A, Steiner I. The abundant latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 are bound to polyribosomes in cultured neuronal cells and during latent infection in mouse trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 1997;71:2897–2904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2897-2904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabowski P J. Splicing regulation in neurons: tinkering with cell-specific control. Cell. 1998;92:709–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall S L, Padgett R A. Requirement for U12 snRNA for in vivo splicing of a minor class of eukaryotic nuclear pre-mRNA introns. Science. 1996;271:1716–1718. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins J D. A survey on intron and exon lengths. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9893–9908. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi K. Manipulation of DNA by PCR. In: Mullis K B, et al., editors. The polymerase chain reaction. Boston, Mass: Birkhauser; 1994. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himmelshpach M, Cavaloc Y, Chebli K, Stevenin J, Gattoni R. Titration of serine/arginine (SR) splicing factors during adenoviral infection modulates E1A pre-mRNA splicing. RNA. 1995;1:794–806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho D Y. Herpes simplex virus latency: molecular aspects. Prog Med Virol. 1992;39:76–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossain A, Schang L M, Jones C. Identification of gene products encoded by the latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1995;69:5345–5352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5345-5352.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson I J. A reappraisal of non-consensus mRNA splice sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3795–3798. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones C, Dehlon G A, Bratanich A C, Kutish G, Rock D L. Analysis of the transcription promoter which regulates the latency-related transcript of bovine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1990;64:1164–1170. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1164-1170.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanopka A, Muhlemann O, Akusjarvi G. Inhibition by SR proteins of splicing of a regulated adenovirus pre-mRNA. Nature. 1996;381:535–538. doi: 10.1038/381535a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozasa T, Itoh H, Tsukamoto T, Kaziro Y. Isolation and characterization of the human Gs α gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2081–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krummenacher C, Zabolotny J M, Fraser N W. Selection of a nonconsensus branch point is influenced by an RNA stem-loop structure and is important to confer stability to the herpes simplex virus 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript. J Virol. 1997;71:5849–5860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5849-5860.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutish G, Mainprize T, Rock D L. Characterization of the latency-related transcriptionally active region of the bovine herpesvirus 1 genome. J Virol. 1990;64:5730–5737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5730-5737.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latchman D S. Cell-type-specific splicing factors and the regulation of alternative RNA splicing. New Biol. 1990;2:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Identification of functionally distinct isoforms of the N-type Ca2+ channel in rat sympathetic ganglia and brain. Neuron. 1997;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mador N, Panet A, Latchman D, Steiner I. Expression and splicing of the latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 in neuronal and non-neuronal cell lines. J Biochem. 1995;117:1288–1297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manley J L, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1569–1574. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin T E, Barghusen S C, Leaser G P, Spear P G. Redistribution of nuclear ribonucleoprotein antigens during herpes simplex virus infection. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2069–2082. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mount S M. A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:459–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mount S M, Burks C, Hertz G, Stormo G D, White O, Fields C. Splicing signals in Drosophila: intron size, information content, and consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4255–4262. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mount S M. Genetic depletion reveals an essential role for an SR protein splicing factor in vertebrate cells. Bioessays. 1997;19:189–192. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicosia M, Zabolotny J M, Lirette R P, Fraser N W. The HSV-1 2 kb latency-associated transcript is found in the cytoplasm comigrating with ribosomal subunits during productive infection. Virology. 1994;204:717–728. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Hare K, Murphy C, Levis R, Rubin G M. DNA sequence of the white locus of Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 1984;15:437–455. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puga A, Notkins A L. Continued expression of a poly(A)+ transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. J Virol. 1987;61:1700–1703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1700-1703.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quan F, Forte M A. Two forms of Drosophila melanogaster Gs are produced by alternate splicing involving an unusual splice site. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:910–917. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reyes A A, Small S J, Akeson R. At least 27 alternatively spliced forms of the neural cell adhesion molecule mRNA are expressed during rat heart development. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1654–1661. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rock D L, Hagesmoser W A, Osorio F A, Reed D E. Detection of bovine herpesvirus type 1 RNA in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected rabbits by in situ hybridization. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2515–2520. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rock D L, Beam S L, Mayfield J E. Mapping bovine herpesvirus type 1 latency-related RNA in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected rabbits by in situ hybridization. J Virol. 1987;61:3827–3831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3827-3831.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rock D L. The molecular basis of latent infection by alphaherpesviruses. Semin Virol. 1993;4:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rock D L. Latent infection with bovine herpesvirus type 1. Semin Virol. 1994;5:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodahl E, Haarr L. Analysis of the 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript expressed in PC12 cells productively infected with herpes simplex virus type 1: evidence for a stable nonlinear structure. J Virol. 1997;71:1703–1707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1703-1707.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russell C B, Fraga D, Hinrichsen R D. Extremely short 20-33 nucleotide introns are the standard length in Paramecium tetraurelia. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1221–1225. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salkoff L, Butler A, Scavarda N, Wei A. Nucleotide sequence of the putative sodium channel gene from Drosophila: the four homologous domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8569–8572. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sandri-Goldin R M, Hibbard M K, Hardwicke M A. The C-terminal repressor region of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP27 is required for the redistribution of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles and splicing factor SC35; however, these alterations are not sufficient to inhibit host cell splicing. J Virol. 1995;69:6063–6076. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6063-6076.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sawtell N M, Thompson R L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcription unit promotes anatomical site-dependent establishment and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1992;66:2157–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2157-2169.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schang L M, Hossain A, Jones C. The latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1 encodes a product which inhibits cell cycle progression. J Virol. 1996;70:3807–3814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3807-3814.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schang L M, Jones C. Analysis of bovine herpesvirus 1 transcripts during a primary infection of trigeminal ganglia of cattle. J Virol. 1997;71:6786–6795. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6786-6795.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sidrauski C, Cox J S, Walter P. tRNA ligase is required for regulated mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith K, Long C, Bowman B, Manos M. Using cosolvents to enhance PCR amplification. Amplifications. 1990;5:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith C M, Steitz J A. Sno storm in the nucleolus. New roles for myriad small RNPs. Cell. 1997;89:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spivack J G, Fraser N W. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts during latent infection in mice. J Virol. 1987;61:3841–3847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3841-3847.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spivack J G, Woods G M, Fraser N W. Identification of a novel latency-specific splice donor signal within the herpes simplex virus type 1 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript (LAT): translation inhibition of LAT open reading frames by the intron within the 2.0-kilobase LAT. J Virol. 1991;65:6800–6810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6800-6810.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stamm S, Casper D, Dinsmore J, Kaufmann C A, Brosius J, Helfman D M. Clathrin light chain B: gene structure and neuron-specific splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5097–5103. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talerico M, Berget S M. Intron definition in splicing of small Drosophila introns. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3434–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tanaka S, Minagawa H, Toh Y, Liu Y, Mori R. Analysis by RNA-PCR of latency and reactivation of herpes simplex virus in multiple neuronal tissues. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2691–2698. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tarn W-Y, Steitz J A. A novel spliceosome containing U11, U12, and U5 snRNPs excises a minor class (AT-AC) intron in vitro. Cell. 1996;84:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thompson R L, Sawtell N M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene regulates the establishment of latency. J Virol. 1997;71:5432–5440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5432-5440.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ullrich B, Ushkaryov Y A, Sudhof T C. Cartography of neurexins: more than 1000 isoforms generated by alternative splicing and expressed in distinct subsets of neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:497–507. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Valcarcel J, Green M R. The SR protein family, pleiotropic functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wagner E K, Flanagan W M, Devi-Rao G B, Zhang Y-F, Hill J M, Anderson K P, Stevens J G. The herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is spliced during the latent phase of infection. J Virol. 1988;62:4577–4585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4577-4585.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wagner E K, Bloom D C. Experimental investigation of herpes simplex virus latency. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:419–443. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weiringa B, Hofer E, Weissmann C. A minimal intron length but no specific internal sequence is required for splicing the large rabbit beta-globulin intron. Cell. 1984;37:915–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wirth U V, Vogt B, Schwyzer M. The three major immediate-early transcripts of bovine herpesvirus 1 arise from two divergent and spliced transcription units. J Virol. 1991;65:195–205. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.195-205.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zabolotny J M, Krummenacher C, Fraser N W. The herpes simplex virus type 1 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript is a stable intron which branches at a guanosine. J Virol. 1997;71:4199–4208. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4199-4208.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng Z-M, He P, Baker C C. Selection of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 nucleotide 3225 3′ splice site is regulated through an exonic splicing enhancer and its juxtaposed exonic splicing suppressor. J Virol. 1996;70:4691–4699. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4691-4699.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]