Abstract

Background

Botulinum toxin is a crucial therapeutic tool with broad indications in both cosmetic and medical fields. However, the expanding cosmetic use and increased dosages of botulinum toxin have raised concerns about resistance, making it essential to study the awareness and management practices among healthcare professionals.

Methods

A survey was conducted among clinical physicians using botulinum toxin. The study investigated their experiences, awareness, and management practices related to toxin resistance. Real‐time mobile app‐based surveys were administered to clinicians attending the 45th International Academic Conference of the Korean Academy of Laser and Dermatology (KALDAT) on December 3, 2023.

Results

Among 3140 participants, 673 clinical physicians completed the survey. Of these, 363 clinicians (53.9%) reported experiencing botulinum toxin resistance. Regarding the resistance rate, 59.4% indicated less than 1%, 36% reported approximately 1%–25%, and 95.4% reported less than 25%. Efforts to prevent resistance included maintaining intervals of over 3 months (54.8%), using products with lower resistance potential (47.0%), employing minimal effective doses (28.2%), and minimizing re‐administration (14.9%).

Conclusion

In the South Korean aesthetic medicine community, a majority of clinical physician's report encountering botulinum toxin resistance. Given the potential loss of various benefits associated with resistance, there is a need to establish appropriate guidelines based on mechanistic studies and current status assessments. Educating clinicians on applicable guidelines is crucial.

Keywords: aesthetic doctor, botulinum toxin, prevention of toxin resistance, tolerance

1. INTRODUCTION

Botulinum toxin irreversibly binds to acetylcholine receptors at nerve terminals, disrupting the transmission of neurotransmitters that cause muscle contraction. This paralysis functionally alleviates abnormal movement symptoms or symptoms resulting from overdeveloped muscles. 1

The use of botulinum toxin extends beyond cosmetic applications, encompassing various therapeutic areas, and its indications continue to expand. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 With the popularization of the procedure, there is a growing trend of individuals receiving botulinum toxin injections at a younger age. 7 Consequently, the issue of botulinum toxin resistance has emerged. Botulinum toxin resistance can be classified into primary and secondary resistance. Primary resistance refers to congenital cases where the effects of botulinum toxin are insufficient, defined by less than 25% response even with increased dosage or two–three repeated injections. 8 Secondary resistance occurs when there was an initial response to the first injection, but subsequent injections result in decreased effectiveness or non‐responsiveness. Given the significance of botulinum toxin in treating severe conditions such as post‐stroke rigidity, 9 resistance poses a substantial hindrance to utilizing this essential therapeutic agent.

A survey by Nark Kyoung Rho et al. 10 conducted in 2019 among dermatologists found that 46.3% of clinical physicians experienced secondary resistance (complete or partial). This trend is not unique to domestic studies, as international research reports resistance rates ranging from 0.3% to 27.6%, depending on the targeted condition. 11 , 12 , 13

Botulinum toxin is utilized as a therapeutic agent for severe conditions like post‐stroke spasticity, underscoring the need for clear guidelines to prevent secondary resistance. However, in reality, only consensus‐based recommendations from various expert groups exist, and the adherence to these recommendations in actual clinical practice remains unclear.

To establish clear clinical guidelines for preventing botulinum toxin resistance, it is crucial to assess the awareness and status of botulinum toxin resistance among clinicians across various specialties administering botulinum toxin injections. To achieve this, a web‐based real‐time mobile survey study was conducted targeting clinicians actively performing botulinum toxin procedures.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Development of survey

The authors convened to discuss issues related to botulinum toxin resistance, conducted a review of relevant literature, and simultaneously organized survey items while summarizing previous research findings. A pilot study was conducted among the board members of the Korean Academy of Laser and Dermatology (KALDAT) to validate usability and validity. Subsequently, after further discussions among the authors, the final survey was developed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC202310014).

The survey covered basic demographic information such as gender, age, specialty, procedural experience, frequency of procedures, and procedural behaviors. It also inquired about the practitioner's criteria for retreatment, experiences with resistance, and factors associated with resistance. Specifically related to resistance, questions were posed regarding the interval between procedures, the use of high doses, the presence of multi‐complex proteins (recognized antigens causing resistance), consideration of the use or transition to 7S botulinum toxin known to reduce immune reactions, intradermal injection, and others. All questions are conducted in a multiple‐choice format with single‐item selection, and only questions related to the principles of responding to prevent resistance are designed as multiple‐choice with multiple responses.

2.2. Data collection

This study targeted clinical physicians attending the 45th International Academic Conference of the Korean Academy of Laser and Dermatology (KALDAT) held on December 3, 2023, in Samseong‐dong, Gangnam‐gu, Seoul, South Korea. Participants accessed the real‐time web‐based survey via their mobile devices. Attendees received a text message containing a link from the conference office, and by clicking the link, they entered the survey page. All data transmitted through the link were encrypted, and any personally identifiable information was removed. Participation in the survey was only allowed for those who consented to provide their personal information. The survey consisted of 12 multiple‐choice single‐collection questions and one multiple‐choice question.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The general characteristics of study participants were analyzed through frequency analysis and descriptive statistics. All statistical analyses were conducted using R ver. 4.3.0 software (R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 673 clinical physicians participated in the study. The mean age was 42.6 years, with a higher proportion of males and a predominant presence of aesthetic physicians (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Basic demographics of 673 survey respondents.

| Characteristics | Doctors (N = 673) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 42.6 (0.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 409 (60.8) |

| Female | 264 (39.2) |

| Specialties | |

| Aesthetic physician | 328 (48.7) |

| Dermatologist | 54 (8.0) |

| Plastic surgeon | 42 (6.2) |

| Other physician | 249 (37.0) |

3.2. Analysis of botulinum toxin usage experience

The group with over 5 years of experience was the most prevalent (42.5%), and the majority reported a procedural frequency of one–five times per day (35.2%). The group adjusting the maximum dosage to not exceed 100 units per procedure was the largest (56.5%), and opinions favoring touch‐up procedures within 2–4 weeks in case of procedural dissatisfaction were most common (33.0%). Regular botulinum toxin procedures were most commonly performed every 3–6 months (59.4%), and in cases where the therapeutic dose was considered higher than the recommended amount, the group responding to alternate treatment areas while maintaining the designated procedural interval was the majority (37.9%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Experiences in procedures using botulinum toxin.

| Characteristics | Doctors (N = 673) |

|---|---|

| Total duration of experiences in Botulinum toxin (years) | |

| Less than 1 | 208 (30.9) |

| 1 ≤ duration < 3 | 117 (17.4) |

| 3 ≤ duration < 5 | 62 (9.2) |

| More than 5 | 286 (42.5) |

| Frequency of procedures using botulinum toxin per day | |

| None | 96 (14.3) |

| 1 ≤ frequency < 5 | 237 (35.2) |

| 6 ≤ frequency < 10 | 124 (18.4) |

| 10 ≤ frequency < 20 | 104 (15.5) |

| More than 20 | 112 (16.6) |

| Maximum doses per one procedure using Botulinum toxin (unit) | |

| Less than 100 | 380 (56.5) |

| 100 ≤ maximum dose < 200 | 171 (25.4) |

| 200≤ maximum dose < 300 | 104 (15.4) |

| More than 300 | 18 (2.7) |

| Intervals of re‐procedure among users complaining of undesirable outcomes | |

| No more procedures | 97 (14.4) |

| Less than one week | 84 (12.5) |

| One to two weeks | 196 (29.1) |

| Two to four weeks | 222 (33.0) |

| More than four weeks | 74 (11.0) |

| Intervals of procedures among regular users for aesthetic purpose | |

| Less than two months | 93 (13.8) |

| Two to three months | 115 (17.1) |

| Three to six months | 400 (59.4) |

| More than six months | 65 (9.7) |

| Management if required dose is higher than recommended maximal dose per day | |

| Perform procedures using required dose with different areas while ensuring treatment intervals | 255 (37.9) |

| Perform procedures using split dose with same area at 2–4 weeks of intervals | 154 (22.9) |

| Perform procedures using split dose with same area at 1–2 weeks of intervals | 147 (21.8) |

| Perform procedures using split dose with same area within one week | 117 (17.4) |

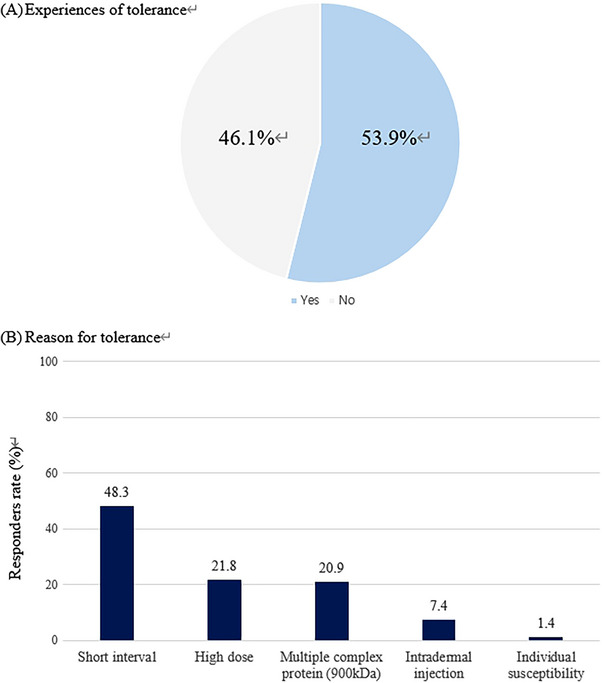

Analysis of Awareness and Behavioral Patterns for Botulinum Toxin Resistance Recognition and Prevention Among the clinical physicians, 363 (53.9%) responded that they had experienced botulinum toxin resistance (including complete and partial resistance) (Figure 1A). The most common reason considered crucial for resistance was short intervals between procedures (48.3%), followed by high‐dose usage (21.8%) and the use of 900 kDa botulinum toxin‐A (20.9%) (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Real world experience of tolerance and perceptions.

The most common response regarding suspected resistant patients was to replace the product with a different company's product (43.7%), followed by switching to 7S botulinum toxin known to cause fewer immune reactions (26.4%). The response indicating the use of the same product at a higher dose was also common (23.8%). (Figure 2A)

FIGURE 2.

Real world experience of tolerance and reaction.

In response to the question about the perceived percentage of patients showing empirical resistance, the group indicating less than 1% was the largest (59.4%), followed by the group indicating 1%–25% (36%) (Figure 2B).

In terms of efforts made for resistance prevention, the response indicating an attempt to maintain a procedural interval of more than 3 months was the most common (54.8%), followed by the use of product categories that reduce resistance (47%) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

TABLE 3.

Perspectives, management and prevention in tolerance of botulinum toxin.

| Characteristics | Doctors (N = 673) |

|---|---|

| Real world experience of tolerance | |

| Yes | 363 (53.9) |

| Reasons why tolerance happened | |

| Short procedure intervals (less than 2–3 months) | 325 (48.3) |

| High dose | 147 (21.8) |

| Product containing multiple complex protein (ex. 900 kDa Botulinum toxin‐A) | 141 (20.9) |

| Intradermal injection | 50 (7.4) |

| Due to individual susceptibility | 10 (1.4) |

| Management of users who are tolerant to Botulinum toxin | |

| Replace the product with another product from different company | 294 (43.7) |

| Replace the product with 7S Botulinum toxin product which is known for reducing immune reaction | 178 (26.4) |

| Use the same product with higher dose | 160 (23.8) |

| Discontinue Botulinum toxin | 41 (6.1) |

| Expected rates of tolerance in botulinum toxin among users for aesthetic purpose (%) | |

| Less than 1 | 400 (59.4) |

| 1 ≤ rates < 25 | 242 (36.0) |

| 25 ≤ rates < 50 | 23 (3.4) |

| 50 ≤ rates < 75 | 7 (1.0) |

| More than 75 | 1 (0.2) |

| Preventive strategies for tolerance | |

| Ensure adequate treatment intervals for more than 3 months | 369 (54.8) |

| Use the product known as reducing the tolerance as possible | 316 (47.0) |

| Use effective minimal dose for the desirable outcome | 190 (28.2) |

| Ensure minimal frequency of re‐procedure for the desirable outcome | 100 (14.9) |

FIGURE 3.

preventive strategies for tolerance (multiple answer allowed).

the field of aesthetic medicine, Botulinum Toxin A initially gained popularity for indications related to periorbital wrinkles in the realm of aesthetic applications, with its approved scope gradually expanding. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Currently, its usage extends widely, even into off‐label applications. 5 Due to the potential occurrence of antigen‐antibody reactions mediated by protein antigens, resistance can develop during repeated treatments after the initial therapy, a phenomenon defined as secondary resistance. 14

Wilson et al. 15 emphasized that the treatment processes and behavioral patterns of aesthetic patients differ from those of disease‐treated groups, highlighting the risk of underreporting and diagnostic omissions regarding Botulinum Toxin resistance in aesthetic patient populations. Additionally, as the usage of toxins in aesthetic contexts increases, and individuals may require lifelong treatment, preventative measures against resistance must be conscientiously considered.

The secondary resistance arises from the immunological reactions associated with the formation of neutralizing antibodies. 14 The immunological response to biological substances follows two main processes. First, dendritic cells assess whether biological material fragments are hazardous. If deemed unsafe, these fragments are captured, and peptide fragments are presented on cell surfaces via Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules (antigen‐presenting cells). The second process involves T‐cells recognizing foreign antigen peptide‐MHC complexes presented by APCs, stimulating B‐cells to form antigen‐specific antibodies. 15 Rungsima et al. 16 have clarified that secondary resistance to Botulinum Toxin is a result of the formation of anti‐complexing protein antibodies.

3.3. Regarding maximum dose

In the past, when Botulinum Toxin was primarily used for wrinkle improvement in aesthetic areas, the usage was not extensive. 17 However, recent off‐label usage for purposes such as muscle size reduction, such as calf or trapezius atrophy, has led to a significant increase in toxin usage even for aesthetic purposes. In response to questions about how to limit daily usage, 56.5% responded with less than 100 units per day, and 97.3% reported using less than 300 units in total. While the recommended safe daily limit for therapeutic areas is considered to be under 350 units, the survey reveals that high‐volume procedures are occurring even in aesthetic areas.

3.4. Regarding touch‐up procedures

When asked about the interval for touch‐up procedures in case of dissatisfaction, 12.5% responded within 1 week, 29.1% within 1–2 weeks, 33% within 2–4 weeks, and 11% beyond 4 weeks. Immunologically, IgM neutralizing antibodies peak within 2–3 weeks, 18 , 19 suggesting that touch‐up procedures are ideally performed within 1 week. However, clear evidence‐based guidelines for this timeframe are lacking. The use of 150 KDa Botulinum Toxin without complex proteins may alleviate concerns about procedural intervals. Still, responses highlight the need to improve the immunological understanding of appropriate procedural intervals for resistance prevention.

3.5. Regarding procedure intervals

While 59.4% of respondents indicated procedures every 3–6 months, 13.8% reported procedures within 2 months. The action duration of Botulinum Toxin varies among individuals based on muscle volume and product type. Guidelines recommend maintaining a minimum interval of 3 months. Education on the rationale for maintaining such intervals may be necessary, especially considering the use of 150 KDa Botulinum Toxin without complex proteins.

3.6. When procedure dosage exceeds the recommended daily amount

Although the majority advocated changing treatment areas while adhering to recommended procedural intervals (37.9%), a considerable proportion suggested procedures within 2–4 weeks (22.9%). In the context of resistance prevention, this underscores the need for effective guidelines promoting minimum effective dosage and sufficient intervals.

3.7. Percentage of clinicians experiencing resistance

The survey revealed that 53.9% of clinicians had encountered patients with Botulinum Toxin resistance, a rate similar to the results of a study by Nark Kyoung Rho et al. in 2022, which reported a resistance experience rate of 43.6%.

3.8. Primary reasons for secondary resistance occurrence

The most frequently cited reason for secondary resistance occurrence was short procedural intervals (48.3%), followed by high dosage (21.8%), multi‐complex protein‐containing products (20.9%), and intradermal injection (7.4%). While emphasizing the importance of procedural intervals in preventing resistance, the survey results indicate a substantial proportion of clinicians who do not adhere to intervals longer than 3 months and perform touch‐up procedures at 2–4 week intervals. This underscores the need for systematic education on these topics.

3.9. Handling of patients suspected of resistance

The most common response to suspected resistant patients was switching to products from different companies (43.7%), followed by switching to 7S Botulinum Toxin (150 KDa) without complex proteins (26.4%), and increasing the dosage of the same product (23.8%). While the response suggesting simply replacing with botulinum toxin from another company in cases of resistance signifies a lack of sufficient understanding of resistance mechanisms, highlighting the need for accurate education on toxin resistance.

3.10. Thoughts on resistance rate

The group that estimated less than 1% resistance prevalence was the largest (59.4%), and those estimating 1%–25% were 36%. Combined, 95.4% of clinicians evaluated the resistance rate as less than 25%, emphasizing that the majority perceive a low occurrence of resistance. However, considering that neither study utilized ELISA tests and relied solely on clinicians' experiences, it leaves room for improvement in terms of objectivity.

3.11. Efforts for resistance prevention

In this multi‐response survey, efforts to maintain procedural intervals of over 3 months were reported by 54.8%, the use of products expected to induce lower resistance by 47%, 28.2% of respondents said they tried to reduce the amount used per treatment, and 14.9% said they tried to minimize touch‐up treatments. All four responses align with resistance prevention guidelines. But considering that 53.9% of clinicians perceived experiencing resistance in the previous survey, there is a discrepancy between clinicians’ awareness of resistance and their actions towards resistance prevention.

4. CONCLUSION

Syeo Young Wee et al. 20 have emphasized the necessity of understanding the mechanisms of resistance, developing products to reduce resistance, creating suitable products to decrease procedural frequency, and the importance of education. Given the observed discrepancy between clinicians' awareness and behaviors regarding toxin resistance, these points become crucial and cannot be delayed. This study not only provides insights into the current status of clinicians’ understanding of Botulinum Toxin resistance but also emphasizes the need for proper education and consensus establishment, making it a pioneering study in this direction.

The study underscores the value of research that demonstrates the inadequacy of clinical guidelines in effectively reaching healthcare professionals in the field and highlights the need for future studies that can address these gaps.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have nothing to report.

Oh SM, Kim HM, Ahn TH, Park MS, Ree YS, Park ES. Aesthetic doctors’ perception and attitudes toward tolerance in botulinum toxin. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30:e13691. 10.1111/srt.13691

Seung Min Oh, Hyoung Moon Kim, and Eun Soo Park contributed equally to this work.

Key contributions: a gap exists between clinicians’ perception of botulinum toxin resistance and actual preventive attitude.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dressler D, Saberi FA. Botulinum toxin: mechanism of action. Eur Neurol. 2005;53(1):3‐9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dorizas A, Krueger N, Sadick NS. Aesthetic uses of the botulinum toxin. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flynn TC. Advances in the use of botulinum neurotoxins in facial esthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahn BK, Kim YS, Kim HJ, et al. Consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1843–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sundaram H, Huang PH, Hsu NJ, et al. Pan‐Asian Aesthetics Toxin Consensus Group . Aesthetic applications of botulinum toxin A in Asians: an international, multidisciplinary, Pan‐Asian consensus. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng J, Chung HJ, Friedland M, et al. Botulinum toxin injections for leg contouring in East Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(suppl 1):S62–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michon A. botulinum toxin for cosmetic treatments in young adults : an evidence based review and survey on current practice among aesthetic practitioners. J Cosmet Dermatol. 22(1):128–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bellows S, Jankovic J. Immunogenicity associated with botulinum toxin treatment. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11:491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuo CL, Hu GC. Post stroke spasticity: A review of epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12(4):280–284 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rho NK, Han KH, Kim HS. An update on the cosmetic use of botulinum toxin: the pattern of practice among Korean dermatologists. Toxins. 2022, 14, 329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dressler D, Wohlfahrt K, Meyer‐Rogge E, et al. Antibody‐induced failure of botulinum toxin a therapy in cosmetic indications. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(suppl 4):2182–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Albrecht P, Jansen A, Lee JI, et al. High prevalence of neutralizing antibodies after long‐term botulinum neurotoxin therapy. Neurology. 2019;92:e48–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walter U, Mühlenhoff C, Benecke R, et al. Frequency and risk factors of antibody‐induced secondary failure of botulinum neurotoxin therapy. Neurology. 2020;94:e2109–e2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carr WW, Jain N, Sublett JW. Immunogenicity of Botulinum Toxin Formulations: Potential Therapeutic Implications. Adv Ther. 2021;38:5046–5064. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01882-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho WWS, Albrecht P, Calderon PE, et al. Emerging trends in botulinum neurotoxin a resistance: an international multidisciplinary review and consensus. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(6):e4407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wanitphakdeedecha R, Kantaviro W, Suphatsathienkul P, et al. association between secondary botulinum toxin A treatment failure ion cosmetic indication and anti‐complexing protein antibody production. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10(4):707‐720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawrence IMoy R An evaluation of neutralizing antibody induction during treatment of glabellar lines with a new US formulation of botulinum neurotoxin type A. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(6 Suppl):S66‐S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schütz K, Hughes RG, Parker A, et al. kinetics of igM and IgA antibody response to 23 valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in healthy subjects. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(1):288‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nestor M, Ablon G, Pickett A. key parameters for the use of abobotulinum, toxin A in aesthetics: onset and duration. Aesthetic Surg J. 2017;37(suppl_1):S20‐S31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wee SY, Park ES. Immunogenicity of botulinum toxin. Arch Plast Surg. 2022;49:12‐18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.