Abstract

While mutational processes operating in the Escherichia coli genome have been revealed by multiple laboratory experiments, the contribution of these processes to accumulation of bacterial polymorphism and evolution in natural environments is unknown. To address this question, we reconstruct signatures of distinct mutational processes from experimental data on E. coli hypermutators, and ask how these processes contribute to differences between naturally occurring E. coli strains. We show that both mutations accumulated in the course of evolution of wild-type strains in nature and in the lab-grown nonmutator laboratory strains are explained predominantly by the low fidelity of DNA polymerases II and III. By contrast, contributions specific to disruption of DNA repair systems cannot be detected, suggesting that temporary accelerations of mutagenesis associated with such disruptions are unimportant for within-species evolution. These observations demonstrate that accumulation of diversity in bacterial strains in nature is predominantly associated with errors of DNA polymerases.

Keywords: mutational signatures, Escherichia, mutation rate, mutation bias, mutation spectrum

Significance.

Theory predicts that the rate at which mutations accumulate should depend on how they affect fitness. As most mutations are deleterious, a low mutation rate may be favored in a stable environment; however, mutations are necessary for adaptation, and their higher rate may be favored if conditions change. Measuring the rate of mutation in past evolution is challenging. Here, we use the fact that “mutator” lineages with elevated mutation rates also have distinct relative frequencies of mutation types—so-called mutational spectra. By reconstructing the mutational spectra of natural Escherichia coli lineages evolved over millions of years, we find that they have spent little, if any, time as mutators.

Introduction

Mutagenesis provides the raw material for evolution, and understanding the processes involved is essential for studying the evolution of bacterial genomes. The progress in this area followed the rise of genome sequencing techniques, which allowed for genome-scale comparative analyses not restricted to reporter genes (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2013, 2015; Tenaillon et al. 2016; Niccum et al. 2018; Sane et al. 2022). Mutations occur in all cells at each replication cycle. However, mutation rates may differ even between laboratory strains of the same bacterial species (Lee et al. 2012). Spontaneous mutations occur due to errors of enzymes involved in DNA replication or repair, combined with exogenous factors (Miller 1996; Nik-Zainal et al. 2016; Andrianova et al. 2017). In bacteria, disruption of these processes yields hypermutator phenotypes, which are characterized by elevated mutation rates and changes in the mutational spectra (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015; Katju and Bergthorsson 2019). Hypermutators accumulate point mutations at rates that are orders of magnitude higher than those of wild-type (WT) strains (Sniegowski et al. 1997).

Multiple distinct hypermutator phenotypes are known. The MutS, MutL, and MutH proteins contribute to hypermutator phenotypes as parts of the DNA mismatch repair system (MMR) (Tenaillon et al. 2016). In WT laboratory strains, there is an approximately 2-fold deficit of mutations in transcribed regions; however, this bias disappears in MMR-defective strains, which means that MMR preferentially, but not exclusively, repairs transcribed regions (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015). A different type of hypermutators arise due to mutations in DnaQ, DNA polymerase III ɛ subunit that functions as a 5′-exonuclease ensuring the accuracy of chromosome replication (Gentile et al. 2011; Sprouffske et al. 2018). On a rich medium, mutants that carry an almost inactive DnaQ have a 10 to 1,000-fold higher mutation rate than the WT strains (Cox and Horner 1982). Inactivation of DnaQ also leads to activation of the SOS response (Gautam et al. 2012); however, SOS-induced error-prone polymerases do not contribute to the mutation rate or spectra of DnaQ mutants (Niccum et al. 2018), indicating that the changes observed in DnaQ mutants are caused by DnaQ inactivation itself. Furthermore, a mutator phenotype can arise from mutations in error-prone DNA polymerases IV (UmuDC) and V (DinB), and in DNA polymerase II (PolB). Inactivation of these polymerases yields elevated mutation rates under some conditions (Strauss et al. 2000; Bhamre et al. 2001; Sanders et al. 2006) but not in normally growing cells (Foster et al. 2015). Finally, inefficient removal of oxidized nucleotides, especially 8-oxoG, also influences mutation accumulation rates and spectra (Foster et al. 2015). Oxidized guanines are removed via two major pathways, MutT that hydrolyzes 8-oxoG, or MutM or MutY that correct 8-oxoG:A mispairs (Tajiri et al. 1995; Fowler et al. 2003).

Mutation rates depend on the neighboring nucleotides, in particular in bacteria (Sung et al. 2015; Foster et al. 2018). Still, most previous studies of mutations in bacteria mainly considered single-nucleotide mutations regardless of the adjacent nucleotides. Meanwhile, accounting for these nucleotides, the so-called mutational contexts, provides a finer resolution and allows distinguishing between processes that underlie mutagenesis. This approach has been widely applied and proved to be fruitful in cancer genomics (Nik-Zainal et al. 2012; Alexandrov et al. 2013, 2020; Helleday et al. 2014; Andrianova et al. 2017; Seplyarskiy et al. 2017). Typically, it is assumed that mutagenesis reflects the contribution of multiple distinct mutational processes, each of which may include one or more DNA damage and/or maintenance mechanisms (Alexandrov et al. 2013). These individual processes affecting mutagenesis are characterized by specific patterns of mutations, or mutational signatures. A mutational signature as used here is characterized by the relative frequencies of six single-nucleotide mutation subtypes: C > A (i.e. the C:G pair to the A:T pair; hence equivalent to G > T), C > G, C > T, T > A, T > C, and T > G (equivalent, respectively, to G > C, G > A, A > T, A > G, and A > C). These frequencies are measured for positions flanked by each of the four possible nucleotides (A, G, C, and T) from each side, yielding a total of 96 (6 × 4 × 4) possible mutation types. In cancer genomics, relative contributions of various mutational processes are inferred from tumor samples by decomposition of the observed mutational spectra into several standard signatures (Alexandrov et al. 2013). By contrast, in bacteria, mutational signatures may be observed directly by analyzing genomes of spontaneous mutator strains or laboratory knockouts of particular genes yielding mutation accumulation (MA) lines. Sequencing data on MA lines in model bacterial species are now available for strains generated in several laboratories in different set-ups, mostly for Escherichia coli (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015; Sung et al. 2015; Schroeder et al. 2016, 2017; Niccum et al. 2018, 2019). Furthermore, data on naturally occurring mutators can be obtained from in vitro evolution experiments. For example, in the E. coli long-term evolution experiment (LTEE) (Tenaillon et al. 2016; Good et al. 2017), six strains acquired spontaneous mutations that affect MMR or removal of oxidized nucleotides. Both MA lines and evolution experiments allow for observing thousands of single nucleotide mutations in mutator lineages, providing sufficient resolution to characterize mutational signatures associated with various mutational mechanisms.

While MA lines are specifically designed to minimize selection, hypermutator lines in LTEE were also shown to evolve almost neutrally (Good et al. 2017). Therefore, in both types of data, mutations primarily reflect mutational biases. Slower accumulation of mutations in nonmutator strains can be shaped by selection, both positive and negative (Foster et al. 2015; Good et al. 2017), with most positions in bacterial genomes subject to negative selection. Still, intergenic regions evolve in an almost neutral regime (Thorpe et al. 2017; Rocha 2018), or are at least less affected by negative selection (Tsoy et al. 2012; Shelyakin et al. 2019). This allowed us to use intergenic regions to infer mutational processes in nonmutator strains.

Here, we address two questions: whether the mutational signatures and mutational processes underlying these signatures may be inferred from experimental data on hypermutators; and how these mutational processes contribute to accumulation of mutations in E. coli strains in laboratory and in nature.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

We obtained the WT strain of E. coli K-12 MG1655 from the Coli Genetic Stock Centre (CGSC, Yale University), streaked it on LB (Luria Bertani) agar, and chose one colony at random as the WT ancestor for subsequent experiments. We similarly obtained the mutator strains of E. coli (ΔmutH, ΔmutL, ΔmutS) from the Keio collection (BW25113 strain background) (Baba et al. 2006) of gene knockouts from the same stock center. These gene knockouts were made by replacing open reading frames with a Kanamycin resistance cassette, such that removing the cassette generates an in-frame deletion of the gene. The design of gene deletion primers ensured that downstream genes were not disrupted due to polar effects. For each strain, we moved the knockout loci from the BW25113 background into the MG1655 (WT) background using P1-phage transduction (Thomason et al. 2007). We then removed the kanamycin resistance marker by transforming kanamycin-resistant transductants with pCP20, a plasmid carrying the flippase recombination gene and AmpR resistance marker. We grew ampicillin-resistant transformants at 42 °C in LB broth overnight to cure pCP20. We streaked out 10 µL of these cultures on LB plates. After 24 h, we replica-plated several colonies on both kanamycin-LB agar plates and ampicillin-LB agar plates, to screen for the loss of both kanamycin and ampicillin resistance. We PCR-sequenced the knockout locus to confirm removal of the kanamycin cassette.

Experimental Evolution Under MA and Whole-genome Sequencing to Identify Mutations

For each mutator strain, we founded 20 MA lines from a single ancestral colony (two lines per Petri plate), incubated at 37 °C, as described earlier for WT MA (Sane et al. 2018). For each line, every 24 h we streaked out a random colony (closest to a premarked spot) on a fresh LB agar plate. Every 4 to 5 d, we inoculated a part of the transferred colony in LB broth at 37 °C for 2 to 3 h and froze 1 mL of the growing culture with 8% DMSO at −80 °C. For the current study, we used stocks frozen on day 50 (∼1,375 generations). For each strain, we sequenced whole genomes from the last stored colony of each lineage as follows. We inoculated 2 µL of the frozen stock of each evolved MA line (or the ancestor) in 2 mL LB, and allowed the cells to grow overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. We extracted genomic DNA (GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA kit, Sigma–Aldrich), quantified it (Qubit HS dsDNA assay, Invitrogen), and pooled equal amounts of genomic DNA from each of the 20 lines for a given mutator strain into a single tube. Thus, we prepared three pools of genomic DNA, one each for the mutators ΔmutH, ΔmutL, and ΔmutS, each containing an equal amount of genomic DNA from each of the 20 MA lines. We then prepared paired-end libraries from the ΔmutH, ΔmutL, and ΔmutS MA ancestors and the three pooled genomic DNA samples using the Illumina Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit per the manufacturer's instructions. We sequenced all libraries on the Illumina MiSeq platform using the 2 × 250 bp paired-end V2 reaction chemistry. For the ΔmutH, ΔmutL, and ΔmutS MA ancestors, we obtained 1.14, 1.49 and 1.06 M paired-end reads with quality >Q30, respectively. For the pooled evolved lines, we obtained 2.09, 2.18, and 2.35 M paired-end reads, respectively, with quality >Q30, corresponding to an average per base coverage of ∼ 116x, 121x, and ∼130x. For each sample, we aligned quality-filtered reads to the NCBI reference E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome (RefSeq accession ID GCA_000005845.2) using the Burrows–Wheeler short-read alignment tool (Li and Durbin 2010). We generated pileup files using SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) and used VARSCAN to extract a list of base-pair mutations and short indels (<10 bp) (Koboldt et al. 2009). For the MA ancestors, we only retained mutations with >80% frequency that were represented by at least five reads on both strands for further analysis. For the pooled evolved MA lines, we retained mutations with >5% frequency that were represented by at least three reads on both strands. After removing ancestral mutations (i.e. mutations that differentiated the ancestors from the reference E. coli genome) from the evolved lines, we identified 985, 875, and 768 SNPs in ΔmutH, ΔmutL, and ΔmutS evolved MA lines, respectively.

Hypermutator Data Published Earlier

We considered three main sources of data. (1) Sequences of six mutator strains from the LTEE experiment: Ara-1 and Ara+6 with MutT deficiency and Ara-2, Ara-3, Ara-4, and Ara+3 with mutations in MMR-associated genes (Tenaillon et al. 2016). The data for this experiment were downloaded from http://barricklab.org/shiny/LTEE-Ecoli/. Only SNPs were selected from the obtained file. Additionally, mutations observed at different time points for the same strain were merged to avoid repeated counting of mutations that had occurred early in the experiment. The obtained table was converted to the vcf format. (2) Experiments on MA strains for all major mutational processes from Patricia L. Foster's laboratory (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015; Niccum et al. 2018). In case of data from refs (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015), we obtained information about mutations from the Supplementary materials and converted it to the vcf format. To obtain mutations caused by inactivated DnaQ (Niccum et al. 2018), we downloaded sequencing data from SRA (SRA IDs: SRR7748246, SRR7748247, SRR7748248, SRR7748249, SRR7748253, SRR7748306, SRR7748326, SRR7748342, SRR7748539, SRR7748540, SRR7748541, SRR7748542, SRR7748543, SRR7748592, SRR7748593, SRR7748594, SRR7748595, SRR7748733, SRR7748734, SRR7749018, SRR7749020, SRR7749022, SRR7749036, SRR7749037, SRR7749062, SRR7749108). The obtained reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic-0.39 (Bolger et al. 2014) with parameters LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 MINLEN:36. The trimmed paired reads were processed as described in the original publication. The variants were called with mpileup from bcf-tools with the minimal sequencing depth of at least 20 reads. In total, we obtained 13,512 SNPs of which four occurred more than once and were discarded, yielding 13,504 mutations.

Laboratory Strain Data

We used nonmutator data from LTEE (Tenaillon et al. 2016), and experiments from Patricia L. Foster's laboratory (Foster et al. 2015). All LTEE nonmutator strains were merged together for further analysis. Duplicated mutations were filtered out to avoid selection effects. We considered separately all available mutations and mutations in intergenic regions.

Reconstruction of the E. coli Phylogeny

Complete genomes of 522 E. coli strains were downloaded from Genbank (Benson et al. 2018). The complete list of genomes is provided in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online. The initial set of orthology groups (OGs) from 32 phylogenetically diverse E. coli and Shigella strains was taken from Gordienko et al. (2013). We produced alignments for each universal group (OGs with single-copy genes present in all analyzed genomes) with ClustalW version 2.1 (Larkin et al. 2007). For each alignment, we generated a consensus sequence with the EMBOSS package ver. 6.6.0 and mapped these consensuses to the genomes with bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). All groups that remained universal and single copy (690 genes) were realigned. Alignments for individual genes were concatenated and all columns with gaps were removed. This final alignment was used to construct the phylogenetic tree with PhyML v3.3 with the GTR substitution model (Guindon et al. 2010).

Genome Alignments and Reconstruction of the Ancestral States

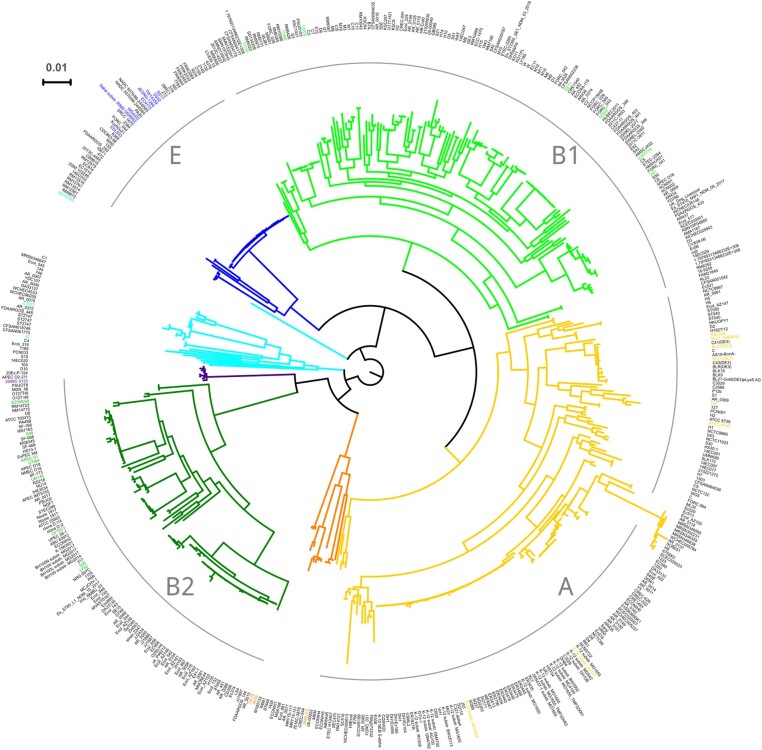

Based on the E. coli phylogenetic tree, we selected four clades that contained at least 45 genomes. For the genomes where phylogroup information was available (shown as colored leaves in Fig. 2), we checked that genomes within the clade belong to the same E. coli phylogroup.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 522 complete E. coli genomes. The maximum likelihood tree was reconstructed from the concatenated alignment of universal single-copy orthologous genes (see Material and Methods). The four analyzed clades, A , B1, B2, and E are indicated with gray arcs. Leaves for which the phylogroup is indicated in metadata are colored accordingly. Black leaves mean that no phylogroup information is available.

For each of the selected clades, we constructed genome alignments with ProgressiveCactus (Armstrong et al. 2020). For each clade, we selected one representative genome that was then used to identify gene boundaries and select intergenic regions between convergent genes (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The output format was converted to maf, with the representative genome serving as the reference, using the hal2maf tool from ProgressiveCactus with parameters: –noDupes –onlySequenceNames –noAncestors –maxBlockLen 1000000. From this alignment, we extracted all variable columns in intergenic regions that (i) contained at least five genomes and (ii) had conserved columns to their left and right. Variable columns with adjacent variable columns or columns with gaps were discarded.

For these positions, we reconstructed the ancestral state with the baseml program from the PAML package v4.9j (Yang 2007).

Reconstruction of Mutational Profiles in Natural Strains

From the PAML results (rst), we obtained the number of substitutions in the variable column for each site and then pooled this for all sites for each context within the clade.

We calculated the number of mutations in all intergenic regions, and separately in intergenic regions between convergent genes. In order to make results compatible between different clades, the number of observed mutations in each context was normalized by the total number of mutations observed for the clade. To control for possible incorrect reconstruction of ancestral states by baseml, in an alternative procedure, if there were multiple identical (parallel) mutations at the given site for the particular clade, we counted them as just one mutation in mutation counts.

Mutational Signatures

For each available experiment we calculated the contexts based on the initial strains in which the experiment was performed. Mutational signatures reconstructed from the data were calculated as the average normalized contribution of a particular mutation among all available mutator strains with the given deficiency. The reconstruction of mutational signatures was performed in R ver 4.1.1. To reconstruct signatures with the NMF approach, we used the NMF package in R. The Bayesian NMF approach was implemented with the ccfindR package. The scripts to reproduce this analysis are available on github (see Data Availability).

Deconvolution of obtained mutational profiles by mutational signatures was performed with the MutationalPatterns package (Blokzijl et al. 2018).

Results

Meta-analysis of MA Lines in E. coli

To study mutations accumulated via different mutational processes, we collected all available data on mutation accumulation in mutator strains of E. coli (see Materials and Methods). We used sequencing data from four main sources: (i) six mutator strains that had emerged in the LTEE experiment: Ara-1 and Ara+6 with the MutT deficiency and Ara-2, Ara-3, Ara-4 and Ara+3 with mutations in MMR-associated genes (Tenaillon et al. 2016); (ii) MA strains for all major mutational processes from the Foster laboratory (Lee et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2015, 2018), (iii) mutY deficient MA strains (Sane et al. 2022), and (iv) a set of MA strains deficient in MMR components MutH, MutL, and MutS obtained specifically for this study (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online; Materials and Methods).

The resulting dataset included data on multiple distinct mutational processes, and for many of these processes, data came from several sources. Specifically, strains with defective MMR systems were collected from three independent labs, and in total yielded almost 12,000 mutations (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). The MutT and MutY mutator strains came each from two independent labs and had, respectively, nearly 9,000 and 5,000 mutations. We also considered strains with defective genes encoding the epsilon subunit of DNA polymerase III (dnaQ), DNA polymerase II (polB), DNA polymerase IV (umuDC), nucleotide excision repair ATPase (uvrA), base excision repair (BER) endonucleases III and VIII (nth and nei, respectively), and exonucleases III and IV (xthA and nfo, respectively) (Foster et al. 2015; Niccum et al. 2018). In total, our dataset included 40,694 mutations from 17 experiments (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online).

To describe the overall mutation types characteristic of mutational processes in our data, we first extracted single-nucleotide mutations and combined complementary mutations, hence retaining six types of mutations. MA lines with similar deficiencies, such as MMR, MutT, and MutY deficient strains obtained in different laboratories, had similar single-nucleotide mutational profiles, which means that the observed mutational spectra were independent of experimental conditions (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). As shown earlier, MMR and DnaQ mutants were associated with transitions (C > T and T > C) (Foster et al. 2015); MutY mutants generated mostly C > A transversions; whereas MutT mutants almost exclusively carried T > G transversions. Strains deficient in the nth and nei genes carried prevalent C > T mutations. MA strains deficient in polB, umuDC, uvrA, xthA, and nfo had relatively flat mutational profiles with a higher prevalence of all six types of mutations relative to the “wild type” laboratory E. coli strain (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online).

Reconstruction of Mutational Signatures from Hypermutators

Analyzing only mutations without accounting for their contexts does not produce sufficient resolution to distinguish, for example, between the excess of C > T mutations caused by MMR and by errors of polymerase III. To distinguish between mutations caused by different mutational processes, we considered three-nucleotide contexts, again collapsing complementary mutations, for a total of 96 types of mutations. We reconstructed the mutational profiles for each strain independently (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online).

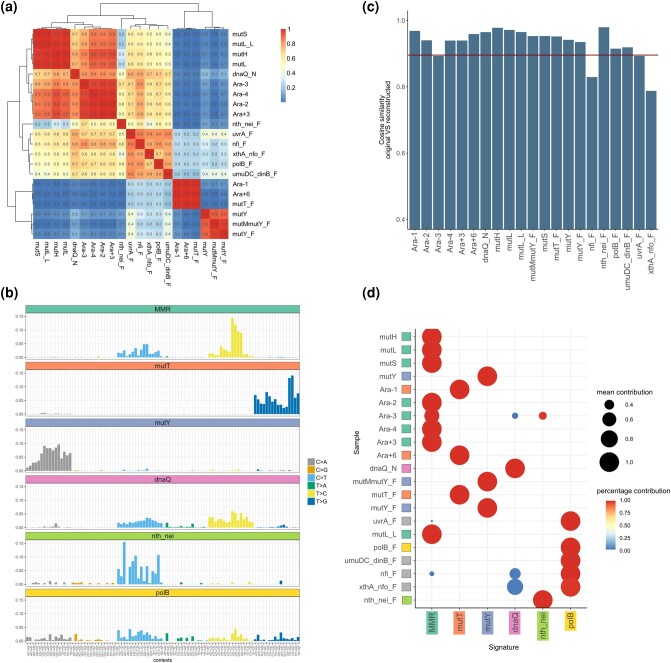

We compared the mutational profiles of each strain using cosine similarity (see Materials and Methods), and observed that they form distinct clusters (Fig. 1a). We divided all strains into seven groups based on similarity of their mutational profiles: MMR-deficient strains from the LTEE experiment; DnaQ MA strains; MMR-deficient MA strains; MA strains with defective MutY, MutT, BER endonucleases III and VIII; and PolB-deficient and similar MA strains. The clustering matched the type of deficiency rather than the source of data. Indeed, while the spectra of MMR-deficient strains from LTEE slightly differed from those of MA strains which had accumulated mutations over a short period of time, the profiles in these two groups of MMR-deficient strains were still highly similar.

Fig. 1.

Reconstruction and validation of mutational signatures from the mutator data. a) Cosine similarity matrix between 3-letter mutational profiles for various mutator strains. b) Signatures of mutational processes reconstructed from the mutator strains (see also supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online). c) Similarity between the original and reconstructed profiles for the mutator strains. d) Signatures of mutational processes are correctly assigned to the mutator strains. The size of the circle represents the mean contribution of the mutational signature in the sample, and the color of the circle represents the percentage of bootstrap replicates where this signature was observed.

To reconstruct the signatures characteristic of these mutational processes, we applied three different approaches. The direct approach was to define the mutational signature as the average mutational profile for all lines (both MA and LTEE) with a given defect. Additionally, we used two different techniques for de novo identification of signatures from a joint dataset of all lineages: nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) and Bayesian NMF (see Materials and Methods). All three methods produced similar results (Fig. 1b, supplementary figs. S3 and S4, Supplementary Material online). The consistency between the direct and the de novo approaches provides, to our knowledge, the first direct experimental validation for the de novo approach. For further analysis, we used the signatures obtained directly from experimental data, assuming them to be the most reliable.

To ask how adequately the obtained signatures describe mutations observed in the mutators, we decomposed mutational profiles for each hypermutator strain into the signatures and then reconstituted the profiles. For 18 out of 21 lineages, the reconstructed profile had >90% cosine similarity with the original profile, and in the remaining cases, the similarity exceeded 80% (Fig. 1c). The main process was correctly identified in all experimental setups (Fig. 1d).

Accumulation of Mutations in Nonmutator Laboratory Strains

To obtain mutational profiles for the strains accumulating mutations at a normal rate in laboratory experiments, we considered nonmutator phenotypes from the LTEE (two strains) and Foster (three strains) experiments (see Materials and Methods). In total, these experiments comprised 1,877 mutations across the genome, of which 40% were C > T transitions (supplementary fig. S5a and table S1, Supplementary Material online). The observed spectra differed from all profiles observed in the mutator strains, both for the whole genome and when we only considered intergenic regions (supplementary fig. S5a, b, Supplementary Material online). Accumulation of mutations in both LTEE mutators and MA lines was shown to be mostly driven by mutational bias and not affected by selection (Couce et al. 2017), while in nonmutator strains, the whole-genome mutational profile differed substantially from that of intergenic regions; specifically, it comprised considerably fewer T > C transitions (supplementary fig. S5 and table S1, Supplementary Material online). The difference between the mutational profiles of coding and intergenic regions arises due to stronger selection and/or the activity of MMR in the coding regions. To control for these differences in our comparisons with mutator strains, for further analysis of nonmutators, we considered only 375 mutations observed in intergenic regions. This means that we were unable to study the contribution of MMR to mutation accumulation in nonmutator strains.

Accumulation of Mutations during the Divergence of Natural E. coli Lineages

Finally, we considered mutational processes affecting natural populations of E. coli. For this, we collected a dataset of 522 complete E. coli genomes, reconstructed their phylogeny based on a set of single-copy universal genes, and selected four major clades each containing at least 40 genomes (see Materials and Methods), for a total of 470 genomes. These clades roughly corresponded to the established phylotypes A, B1, B2, and E (Fig. 2; supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). For each clade, we reconstructed the whole-genome alignment and inferred single-nucleotide mutations at all phylogenetic branches with the baseml program of the PAML package (Yang 2007). To minimize the effects of selection, we only considered mutations in intergenic regions with more than 20,000 mutation per phylogroup (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). To additionally confirm that the reconstructed mutational profiles are minimally affected by selection, we also separately analyzed intergenic regions between convergent genes (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online), expected to be under weaker selection because they contain fewer regulatory sequences (Tsoy et al. 2012). The reconstructed profiles were very similar between the considered clades, as were the profiles for all intergenic regions and intergenic regions of convergent genes (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). In further analysis, we used the profiles built for all intergenic regions.

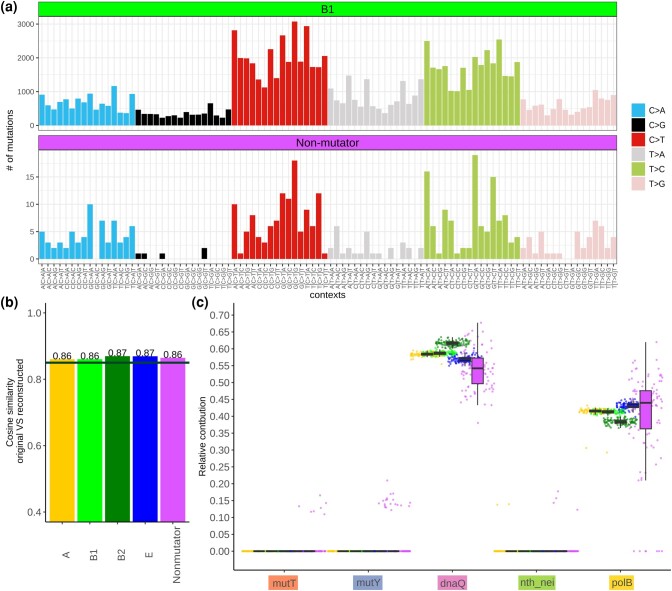

Laboratory nonmutator Strains and Natural Strains Have Similar Mutational Profiles

We find that the mutational profiles of intergenic regions of diverging natural E. coli lineages are very similar to those of lab-based nonmutator strains (Fig. 3a). This indicates that accumulation of mutations in the course of evolution is driven by the same mutational processes as that observed in nonmutator strains during laboratory MA experiments. To better understand the processes responsible for mutation accumulation in these two settings, we decomposed the mutational profiles into a set of six signatures of six distinct mutational processes reconstructed from the mutator data.

Fig. 3.

Contribution of mutational signatures to the evolution of intergenic regions in E. coli natural and in nonmutator laboratory strains. a) Mutational profile for nonmutator strains and clade B1. (Profiles for all clades are shown in supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online.) b) Cosine similarity between the original mutational profiles and the reconstructed profiles. The horizontal line is at 0.85. c) Relative contribution of each signature to the reconstructed profile. Each dot is the value obtained in one bootstrap replicate. Dots are colored by the data type as in (b).

Both the laboratory nonmutator strains and the natural lineages are rather well described by a combination of all six mutational processes, as indicated by the >86% cosine similarity between the actual mutational signature and its best reconstruction from these six processes (Fig. 3b; supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online). The “missing” similarity in the natural lineages is very close to that in the laboratory settings and suggests that external and internal factors that are present in the natural environment of E. coli are present in laboratory conditions as well.

Consideration of contribution of each mutational process revealed that the predominant process causing mutations is associated with the DnaQ signature, which covered 59% (57% to 61%) of all explained mutations in natural lineages and 56% (46% to 65%) in laboratory nonmutators, suggesting a strong contribution of the major replicative DNA polymerase III. The remaining variability, comprising ∼45% of explained mutations, is explained by the PolB signature, indicating the contribution of the replicative DNA polymerase II. There was no signature of defective BER endonucleases III and VIII (Nth and Nei), MutT, or MutY (Fig. 3c). We observed zero contribution of the MMR mutational signature to both datasets (not shown in Fig. 3d), suggesting that the impact of the MMR is low, although this conclusion can be affected by the fact that we considered only noncoding regions, while MMR preferentially acts on transcribed regions.

The inferred patterns were very similar between all four E. coli clades, indicating that they are characteristic of the overall E. coli evolution rather than lineage-specific peculiarities. The results were stable across bootstrap replicates, and robust when we considered only intergenic regions between convergent genes (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). Additionally, we verified that the observed differences in the mutational profiles of natural strains and laboratory nonmutators were not an artifact of the ancestral state reconstruction by baseml. For that, counts for all identical mutations that had occurred at a particular position multiple times within a clade were set to one, e.g. recurrent identical mutations at the same site were ignored. The resulting contributions of mutational signatures were almost identical to the ones described above for the full dataset (supplementary fig. S9, Supplementary Material online).

Discussion

The properties of mutagenesis shape evolution, determining the load of deleterious mutations and channeling adaptation to new conditions. While the main processes resulting in single-nucleotide mutations are rather well understood, their relative contributions to bacterial evolution are largely unknown. In particular, it is not clear whether experimental laboratory conditions can adequately model mutagenesis in the complex natural environments experienced by bacterial lineages throughout their evolution. To address this question, we combine experimentally inferred data on mutagenesis with the mutational patterns revealed by lab MA experiments and with the reconstructed mutations accumulated over millions of years in evolving E. coli lineages.

This approach has several limitations. First, while experimental bacterial systems have yielded much of the current knowledge of biochemistry of mutagenesis, there are relatively few large-scale statistical analyses of accumulation of mutations in bacteria. Tens of mutational signatures have been identified in higher eukaryotes, but for many of them, the underlying mutational process is unknown (Alexandrov et al. 2020). Conversely, 12 mutational processes have been characterized in bacteria, but only for six of them there is sufficient data to reliably reconstruct mutational signatures. The fact that the decomposition of the accumulated mutations into mutational signatures in our analysis (∼86% cosine similarity) is poorer than that in e.g. cancer genomics studies (>90%) (Alexandrov et al. 2013) may be at least partially explained by this deficiency. While our study reliably identifies the relative contributions of the six studied mutational processes, knowledge of signatures of other mutational processes will further clarify the picture.

Second, inference of mutagenesis from MA lines and divergence can be confounded by selection. Bacteria have compact genomes, more than 80% of which are coding, meaning that the bulk of a genome is subject to selection; to a weaker degree, selection also affects intergenic regions (Tsoy et al. 2012; Rocha 2018; Shelyakin et al. 2019). While polymorphism and divergence data can be used to infer mutation patterns (Seplyarskiy et al. 2012; Harris and Pritchard 2017; Terekhanova et al. 2017), the effect of selection on the mutations that distinguish long-term-evolved lineages is expected to be stronger than that in MA lines (where it is very weak; Couce et al. 2017), as these mutations have survived within populations for a longer time and selection has had more opportunity to act. To mitigate this problem, we focused on genomic regions that are predicted to be least affected by selection. Most of our analyses were performed on intergenic regions limiting our ability to study the contribution of the MMR system that mostly acts within transcribed regions. We also considered separately the regions between convergent genes, where the effect of selection was minimal (Tsoy et al. 2012). The results were the same as for all intergenic regions, indicating that the effect of selection was low.

Third, our divergence analysis relies on correctness of the inferred phylogeny and the ancestral state. Systematic biases at these stages of the analysis could distort the inference of mutational spectra. However, the phylogenetic distances between the compared strains were relatively low (Fig. 2), and an alternative method of dealing with recurrent mutations at a site yielded very similar results, indicating that our results were robust in this respect.

Given these limitations, we described the mutational signatures for six determinants of spontaneous mutagenesis in E. coli. Accounting for mutational contexts allowed us to quantitatively assess the causes of spontaneous mutations in the studied bacterial strains. Decomposing the spectra of mutations accumulated in the WT nonmutator strains in the laboratory, and in the natural environments over the course of evolution, into the signatures of six mutational processes allowed us to infer the prevalent forces responsible for mutagenesis.

The observed spectra of reconstructed mutations that have occurred in the course of evolution of natural E. coli lineages are similar to those associated with disruption of DnaQ and PolB. DnaQ is a core epsilon subunit of DNA polymerase III that is required for proof-reading and is essential for accurate DNA replication in E. coli (Scheuermann and Echols 1984; Stefan et al. 2003; Dodd et al. 2020). PolB is a supplementary DNA polymerase II; while it can be induced by the SOS response (Rangarajan et al. 1999; Whatley and Kreuzer 2015), it is also thought to be involved in DNA repair and to play an auxiliary role in chromosomal DNA replication under normal conditions (Banach-Orlowska et al. 2005). The fact that the mutational spectra characterizing real-life evolution largely coincides with those of the enzymes involved in replication-associated repair indicates that the accumulated mutations occur co-replicatively, and suggests that they are associated with insufficient efficiency of these two repair enzymes during normal replication.

The near-identical contributions of PolB and DnaQ signatures to both natural E. coli lineages and laboratory nonmutator E. coli MA strains supports the notion that the bulk of the mutations associated with these two signatures occur co-replicatively. Indeed, if one of these components had a substantial fraction of non-co-replicative mutations, we would expect a higher contribution of the corresponding enzyme to the mutation spectra of natural strains, and lower, to the laboratory strains. This is because laboratory strains have a much higher replication rate than natural strains (20 min vs. 15 h per generation; Gibson et al. 2018), and the proportion of co-replicative versus “clock-like” mutations in the former should be higher.

Surprisingly, no contribution of incorrect removal of 8-oxo-G, caused by ionizing radiation or oxidative metabolism, was observed in either setting, indicating that the time spent by E. coli in oxidized conditions is probably low.

In summary, while it has been disputed whether evolutionary experiments in monoculture bacteria (where the complexity of the real world is removed) adequately represent the real evolution in nature (Lenski 2017), it appears that such experiments in E. coli can very well represent mutation accumulation in natural environments. We find that the mutational spectra of reconstructed mutations that have occurred in the course of evolution of natural E. coli lineages and the mutational spectra of laboratory nonmutator E. coli MA strains were similar to each other. This observation argues against the notion that E. coli evolution in the natural environment involves alternating episodes of accelerated evolution in the mutator regime and slow evolution in the nonmutator regime, suggesting instead that at the scale of evolution of different E. coli strains, the contribution of atypical mutational regimes to the overall mutation accumulation is minor. This is probably due to the high load of deleterious mutations associated with such a regime (Couce et al. 2017). Long-term evolution at the level of bacterial species, which involves gains and losses of repair-associated genes, could follow a different pattern (Sane et al. 2022). It would be interesting to expand this analysis to different evolutionary settings and other bacterial species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project was initiated with Arina Kolotova at the Summer School of Molecular and Theoretical Biology for high school students. We thank our colleagues, in particular Dr. Anna Kaznadzey (IITP RAS) and Dr. Olga Vakhrusheva (Skoltech), for useful discussions and suggestions. We acknowledge help and support from the Next-generation genomics facility at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS-TIFR) for whole-genome sequencing of bacterial strains.

Contributor Information

Sofya K Garushyants, A.A. Kharkevich Institute for Information Transmission Problems, RAS, Moscow, Russia.

Mrudula Sane, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, India.

Maria V Selifanova, Faculty of Bioengineering and Bioinformatics, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia.

Deepa Agashe, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, India.

Georgii A Bazykin, A.A. Kharkevich Institute for Information Transmission Problems, RAS, Moscow, Russia.

Mikhail S Gelfand, A.A. Kharkevich Institute for Information Transmission Problems, RAS, Moscow, Russia; Center for Molecular and Cellular Biology, Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech), Moscow, Russia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Genome Biology and Evolution online.

Authors Contributions

S.K.G. and M.S.G. conceived the project. M.S. performed the MA experiments, sequencing, and variant calling from the data. S.K.G. and M.V.S. reconstructed mutational signatures from experimental data. S.K.G. performed data analysis. D.A., G.A.B., and M.S.G. supervised the research. S.K.G., G.A.B., and M.S.G. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the RFBR 20-54-14005, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR-India; senior research fellowship to MS), the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS-TIFR), and the Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India (Project Identification No. RTI 4006).

Data Availability

All data and scripts required for the analysis of data are deposited in github: https://github.com/garushyants/Ecoli_MutationalSignatures (https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/228692328). The sequencing data is deposited to SRA (SRR26528839, SRR26528838, SRR26528835, SRR26528837, SRR26528836, SRR26528834).

Literature Cited

- Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Tian Ng AW, Wu Y, Boot A, Covington KR, Gordenin DA, Bergstrom EN, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020:578(7793):94–101. 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SAJR, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Børresen-Dale A-L, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013:500(7463):415–421. 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianova MA, Bazykin GA, Nikolaev SI, Seplyarskiy VB. Human mismatch repair system balances mutation rates between strands by removing more mismatches from the lagging strand. Genome Res. 2017:27(8):1336–1343. 10.1101/gr.219915.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J, Hickey G, Diekhans M, Fiddes IT, Novak AM, Deran A, Fang Q, Xie D, Feng S, Stiller J, et al. Progressive Cactus is a multiple-genome aligner for the thousand-genome era. Nature. 2020:587(7833):246–251. 10.1038/s41586-020-2871-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006:2(1):2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banach-Orlowska M, Fijalkowska IJ, Schaaper RM, Jonczyk P. DNA polymerase II as a fidelity factor in chromosomal DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2005:58(1):61–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018:46(D1):D41–D47. 10.1093/nar/gkx1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamre S, Gadea BB, Koyama CA, White SJ, Fowler RG. An aerobic recA-, umuC-dependent pathway of spontaneous base-pair substitution mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mutat Res. 2001:473(2):229–247. 10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00155-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl F, Janssen R, van Boxtel R, Cuppen E. MutationalPatterns: comprehensive genome-wide analysis of mutational processes. Genome Med. 2018:10(1):33. 10.1186/s13073-018-0539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014:30(15):2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couce A, Caudwell LV, Feinauer C, Hindré T, Feugeas J-P, Weigt M, Lenski RE, Schneider D, Tenaillon O. Mutator genomes decay, despite sustained fitness gains, in a long-term experiment with bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017:114(43):E9026–E9035. 10.1073/pnas.1705887114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EC, Horner DL. Dominant mutators in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1982:100(1):7–18. 10.1093/genetics/100.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd T, Botto M, Paul F, Fernandez-Leiro R, Lamers MH, Ivanov I. Polymerization and editing modes of a high-fidelity DNA polymerase are linked by a well-defined path. Nat Commun. 2020:11(1):5379. 10.1038/s41467-020-19165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PL, Hanson AJ, Lee H, Popodi EM, Tang H. On the mutational topology of the bacterial genome. G3 (Bethesda). 2013:3(3):399–407. 10.1534/g3.112.005355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PL, Lee H, Popodi E, Townes JP, Tang H. Determinants of spontaneous mutation in the bacterium Escherichia coli as revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015:112(44):E5990–E5999. 10.1073/pnas.1512136112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PL, Niccum BA, Popodi E, Townes JP, Lee H, MohammedIsmail W, Tang H. Determinants of base-pair substitution patterns revealed by whole-genome sequencing of DNA mismatch repair defective Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2018:209(4):1029–1042. 10.1534/genetics.118.301237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler RG, White SJ, Koyama C, Moore SC, Dunn RL, Schaaper RM. Interactions among the Escherichia coli mutT, mutM, and mutY damage prevention pathways. DNA Repair (Amst). 2003:2(2):159–173. 10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Kalidindi R, Humayun MZ. SOS induction and mutagenesis by dnaQ missense alleles in wild type cells. Mutat Res. 2012:735(1–2):46–50. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile CF, Yu S-C, Serrano SA, Gerrish PJ, Sniegowski PD. Competition between high- and higher-mutating strains of Escherichia coli. Biol Lett. 2011:7(3):422–424. 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson B, Wilson DJ, Feil E, Eyre-Walker A. The distribution of bacterial doubling times in the wild. Proc Biol Sci. 2018:285(1880):20180789. 10.1098/rspb.2018.0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good BH, McDonald MJ, Barrick JE, Lenski RE, Desai MM. The dynamics of molecular evolution over 60,000 generations. Nature. 2017:551(7678):45–50. 10.1038/nature24287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko EN, Kazanov MD, Gelfand MS. Evolution of Pan-Genomes of Escherichia coli, Shigella spp., and Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2013:195(12):2786–2792. 10.1128/JB.02285-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010:59(3):307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K, Pritchard JK. Rapid evolution of the human mutation spectrum. Elife. 2017:6:e24284. 10.7554/eLife.24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T, Eshtad S, Nik-Zainal S. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Genet. 2014:15(9):585–598. 10.1038/nrg3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katju V, Bergthorsson U. Old trade, new tricks: insights into the spontaneous mutation process from the partnering of classical mutation accumulation experiments with high-throughput genomic approaches. Genome Biol Evol. 2019:11(1):136–165. 10.1093/gbe/evy252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Mardis ER, Weinstock GM, Wilson RK, Ding L. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009:25(17):2283–2285. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth. 2012:9(4):357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007:23(21):2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Popodi E, Tang H, Foster PL. Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012:109(41):E2774–E2783. 10.1073/pnas.1210309109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenski RE. Experimental evolution and the dynamics of adaptation and genome evolution in microbial populations. ISME J. 2017:11(10):2181–2194. 10.1038/ismej.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010:26(5):589–595. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009:25(16):2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. SPONTANEOUS MUTATORS IN BACTERIA: insights into pathways of mutagenesis and repair. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996:50(1):625–643. 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccum BA, Lee H, MohammedIsmail W, Tang H, Foster PL. The spectrum of replication errors in the absence of error correction assayed across the whole genome of Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2018:209(4):1043–1054. 10.1534/genetics.117.300515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccum BA, Lee H, MohammedIsmail W, Tang H, Foster PL. The symmetrical wave pattern of base-pair substitution rates across the Escherichia coli chromosome has multiple causes. mBio. 2019:10(4):e01226–19. 10.1128/mBio.01226-19. Available from: https://mbio.asm.org/content/10/4/e01226-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings LA, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012:149(5):979–993. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J, Ramakrishna M, Glodzik D, Zou X, Martincorena I, Alexandrov LB, Martin S, Wedge DC, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016:534(7605):47–54. 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan S, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. A phenotype for enigmatic DNA polymerase II: a pivotal role for pol II in replication restart in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999:96(16):9224–9229. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EPC. Neutral theory, microbial practice: challenges in bacterial population genetics. Mol Biol Evol. 2018:35(6):1338–1347. 10.1093/molbev/msy078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LH, Rockel A, Lu H, Wozniak DJ, Sutton MD. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa dinB-encoded DNA polymerase IV in mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2006:188(24):8573–8585. 10.1128/JB.01481-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane M, Diwan GD, Bhat BA, Wahl LM, Agashe D. 2022. Shifts in mutation spectra enhance access to beneficial mutations. bioRxiv 284158. 10.1101/2020.09.05.284158, 31 October 2022, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sane M, Miranda JJ, Agashe D. Antagonistic pleiotropy for carbon use is rare in new mutations. Evolution. 2018:72(10):2202–2213. 10.1111/evo.13569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann RH, Echols H. A separate editing exonuclease for DNA replication: the epsilon subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984:81(24):7747–7751. 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JW, Hirst WG, Szewczyk GA, Simmons LA. The effect of local sequence context on mutational bias of genes encoded on the leading and lagging strands. Curr Biol. 2016:26(5):692–697. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JW, Randall JR, Hirst WG, O’Donnell ME, Simmons LA. Mutagenic cost of ribonucleotides in bacterial DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017:114(44):11733–11738. 10.1073/pnas.1710995114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seplyarskiy VB, Andrianova MA, Bazykin GA. APOBEC3A/B-induced mutagenesis is responsible for 20% of heritable mutations in the TpCpW context. Genome Res. 2017:27(2):175–184. 10.1101/gr.210336.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seplyarskiy VB, Kharchenko P, Kondrashov AS, Bazykin GA. Heterogeneity of the transition/transversion ratio in Drosophila and Hominidae genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2012:29(8):1943–1955. 10.1093/molbev/mss071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelyakin PV, Bochkareva OO, Karan AA, Gelfand MS. Micro-evolution of three Streptococcus species: selection, antigenic variation, and horizontal gene inflow. BMC Evol Biol. 2019:19(1):83. 10.1186/s12862-019-1403-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniegowski PD, Gerrish PJ, Lenski RE. Evolution of high mutation rates in experimental populations of E. coli. Nature. 1997:387(6634):703–705. 10.1038/42701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprouffske K, Aguilar-Rodríguez J, Sniegowski P, Wagner A. High mutation rates limit evolutionary adaptation in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2018:14(4):e1007324. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan A, Reggiani L, Cianchetta S, Radeghieri A, Gonzalez Vara y Rodriguez A, Hochkoeppler A. Silencing of the gene coding for the ɛ subunit of DNA polymerase III slows down the growth rate of Escherichia coli populations. FEBS Lett. 2003:546(2–3):295–299. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss BS, Roberts R, Francis L, Pouryazdanparast P. Role of the dinB gene product in spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli with an impaired replicative polymerase. J Bacteriol. 2000:182(23):6742–6750. 10.1128/JB.182.23.6742-6750.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung W, Ackerman MS, Gout J-F, Miller SF, Williams E, Foster PL, Lynch M. Asymmetric context-dependent mutation patterns revealed through mutation–accumulation experiments. Mol Biol Evol. 2015:32(7):1672–1683. 10.1093/molbev/msv055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri T, Maki H, Sekiguchi M. Functional cooperation of MutT, MutM and MutY proteins in preventing mutations caused by spontaneous oxidation of guanine nucleotide in Escherichia coli. Mutat Res. 1995:336(3):257–267. 10.1016/0921-8777(94)00062-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon O, Barrick JE, Ribeck N, Deatherage DE, Blanchard JL, Dasgupta A, Wu GC, Wielgoss S, Cruveiller S, Médigue C, et al. Tempo and mode of genome evolution in a 50,000-generation experiment. Nature. 2016:536(7615):165–170. 10.1038/nature18959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terekhanova NV, Seplyarskiy VB, Soldatov RA, Bazykin GA. Evolution of local mutation rate and its determinants. Mol Biol Evol. 2017:34(5):1100–1109. 10.1093/molbev/msx060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason LC, Costantino N, Court DL. E. coli genome manipulation by P1 transduction. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2007:79(1):1.17.1–1.17.8. 10.1002/0471142727.mb0117s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe HA, Bayliss SC, Hurst LD, Feil EJ. Comparative analyses of selection operating on nontranslated intergenic regions of diverse bacterial species. Genetics. 2017:206(1):363–376. 10.1534/genetics.116.195784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoy OV, Pyatnitskiy MA, Kazanov MD, Gelfand MS. Evolution of transcriptional regulation in closely related bacteria. BMC Evol Biol. 2012:12(1):200. 10.1186/1471-2148-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatley Z, Kreuzer KN. Mutations that separate the functions of the proofreading subunit of the Escherichia coli replicase. G3 (Bethesda). 2015:5(6):1301–1311. 10.1534/g3.115.017285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007:24(8):1586–1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and scripts required for the analysis of data are deposited in github: https://github.com/garushyants/Ecoli_MutationalSignatures (https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/228692328). The sequencing data is deposited to SRA (SRR26528839, SRR26528838, SRR26528835, SRR26528837, SRR26528836, SRR26528834).