Summary

Background

Although evidence-based treatments for depression in low-resource settings are established, implementation strategies to scale up these treatments remain poorly defined. We aimed to compare two implementation strategies in achieving high-quality integration of depression care into chronic medical care and improving mental health outcomes in patients with hypertension and diabetes.

Methods

We conducted a parallel, cluster-randomised, controlled, implementation trial in ten health facilities across Malawi. Facilities were randomised (1:1) by covariate-constrained randomisation to either an internal champion alone (ie, basic strategy group) or an internal champion plus external supervision with audit and feedback (ie, enhanced strategy group). Champions integrated a three-element, evidence-based intervention into clinical care: universal depression screening; peer-delivered psychosocial counselling; and algorithm-guided, non-specialist antidepressant management. External supervision involved structured facility visits by Ministry officials and clinical experts to assess quality of care and provide supportive feedback approximately every 4 months. Eligible participants were adults (aged 18–65 years) seeking hypertension and diabetes care with signs of depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score ≥5). Primary implementation outcomes were depression screening fidelity, treatment initiation fidelity, and follow-up treatment fidelity over the first 3 months of treatment, analysed by intention to treat. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03711786, and is complete.

Findings

Five (50%) facilities were randomised to the basic strategy and five (50%) to the enhanced strategy. Between Oct 1, 2019, and Nov 30, 2021, in the basic group, 587 patients were assessed for eligibility, of whom 301 were enrolled; in the enhanced group, 539 patients were assessed, of whom 288 were enrolled. All clinics integrated the evidence-based intervention and were included in the analyses. Of 60 774 screening-eligible visits, screening fidelity was moderate (58% in the enhanced group vs 53% in the basic group; probability difference 5% [95% CI −38% to 47%]; p=0·84) and treatment initiation fidelity was high (99% vs 98%; 0% [−3% to 3%]; p=0·89) in both groups. However, treatment follow-up fidelity was substantially higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group (82% vs 20%; 62% [36% to 89%]; p=0·0020). Depression remission was higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group (55% vs 36%; 19% [3% to 34%]; p=0·045). Serious adverse events were nine deaths (five in the basic group and four in the enhanced group) and 26 hospitalisations (20 in the basic group and six in the enhanced group); none were treatment-related.

Interpretation

The enhanced implementation strategy led to an increase in fidelity in providers’ follow-up treatment actions and in rates of depression remission, consistent with the literature that follow-up decisions are crucial to improving depression outcomes in integrated care models. These findings suggest that external supervision combined with an internal champion could offer an important advance in integrating depression treatment into general medical care in low-resource settings.

Funding

The National Institute of Mental Health.

Introduction

Depressive disorders represent a major source of global disease burden,1 and are responsible for 50 million years lived with disability annually.2 Four-fifths of this burden is in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 Untreated depression can be chronic, recurrent, and fatal, causing substantial morbidity and mortality. Depression commonly co-occurs with other chronic medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes,3 and increases disease progression and mortality from hypertension and diabetes.3

Resources for treatment of depression are extremely scarce in most LMICs. For example, Malawi has four psychiatrists for 19 million citizens and 2·5 psychiatric nurses per 100 000 individuals in the population, many of whom are diverted to non-psychiatric responsibilities.4 Mental health care is not integrated into general medical care and is essentially limited to four central hospitals providing crisis inpatient services.5,6 As in many LMICs, depression is not widely recognised as a medical condition meriting medical treatment, even by medical providers or policy makers. Thus, depression is essentially undiagnosed and untreated nationally.5,6

Integrated depression care models have been developed, tested, and shown to be effective in LMICs. Non-specialist medical providers in LMICs can prescribe and manage antidepressants with effectiveness equal to psychiatrists.7 Lay health workers and community members can deliver common psychological counselling treatments, given appropriate training and ongoing supervision and support, with a similar effectiveness to clinical psychologists.8 However, to improve patient outcomes, implementation strategies are needed to achieve the integration of these models at scale in LMICs.9

We report the results from a cluster-randomised implementation trial in hypertension and diabetes clinics across Malawi. We aimed to compare the success of two implementation strategies in achieving high-quality integration of depression care into chronic medical care and improving mental health outcomes in patients with hypertension and diabetes.

Methods

Study design

The Sub-Saharan Africa Regional Partnership for Mental Health Capacity Building (SHARP) study was a parallel, cluster-randomised, controlled, implementation trial10 comparing two facility-level implementation strategies: an internal facility-based champion (ie, basic strategy) and a champion combined with external expert supervision with audit and feedback (ie, enhanced strategy). The trial addressed the following question: will the enhanced strategy lead to higher quality (fidelity) and more effective (patient health outcomes) integration of an evidence-based intervention (EBI) of depression screening and treatment into hypertension and diabetes medical care than the basic strategy?

Facilities eligible for participation were primary-level or secondary-level hospitals in Malawi’s three regions (Northern, Central, and Southern), which operated an onsite non-communicable disease (NCD) clinic representing the district’s only or primary source of hypertension and diabetes care, provided care to at least 80 patients with hypertension and diabetes per month, and were within reasonable travel time of the research organisations implementing the trial. 16 hospitals were assessed for participation; ten (63%) met the criteria and participated. NCD clinics were staffed by a combination of generalist clinical officers and nurses. This study was approved by the National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (#18/09/2143) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (#18–2211).

Participating facilities and individuals

Patients aged 18–65 years seeking hypertension and diabetes care at a participating facility with a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 depression score of at least 5 at clinical assessment, aligning with the evidence-based intervention treatment algorithm described below, were eligible for enrolment. PHQ-9 scores of 5–9 are generally used to indicate mild depression while scores of 10 and above are used to indicate moderate or severe depression. Exclusion criteria were a history of bipolar or psychotic disorder, or emergent self-harm risk requiring immediate intervention. Pregnancy was not assessed, and pregnant individuals were not excluded. All participants provided written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

Facilities were randomly assigned (1:1) to either the basic strategy or the enhanced strategy by use of covariate-constrained randomisation.11 Randomisation was constrained to balance three facility-level characteristics expected to strongly predict primary outcomes, collected during a 5-month pre-randomisation run-in period during which clinical services were launched at all facilities using the basic strategy: screening fidelity, depression treatment fidelity, and percentage of clinic days covered by clinicians trained in the EBI. All facilities were randomised at one time. One investigator (BWP) generated allocation assignments using the Stata cvcrand procedure and communicated the assignments to the study team, who then launched the enhanced strategy in the assigned facilities.

Assignment could not be masked from clinicians, staff collecting data, or investigators, who were aware which facilities were receiving the enhanced strategy. Although participants were not formally masked, it is unlikely that they were aware whether their facility was receiving supervision visits. Analysts were masked while completing the analysis of pre-specified outcomes.

Procedures

The EBI of depression screening and treatment comprised three core elements: depression screening for all patients12 with a standardised tool (PHQ-2 or PHQ-9), Friendship Bench psychosocial counselling,13 and antidepressant management with measurement-based care.7 The PHQ-9 is a widely used depression screening tool validated in Malawi; its first two items comprise the PHQ-2, a common first-level screen that, if positive, is followed by the full PHQ-9.14 Friendship Bench is an evidence-based, problem-solving therapy counselling intervention developed in Zimbabwe and has been used in multiple studies in Malawi.15 Measurement-based care is evidence-based, algorithm-guided psychiatric medication management for non-specialist clinicians who use standardised metrics (PHQ-9 scores) and decision trees to manage antidepressants,7 which has been previously used in Malawi.16 For this study, all clinicians were trained to administer the PHQ-9 at all visits and to follow an algorithm to initiate and monitor treatment. Friendship Bench was recommended for patients with PHQ-9 scores of 5–9 (ie, mild depression), and measurement-based care with or without adjunctive Friendship Bench was recommended for patients with PHQ-9 scores of 10 and above (ie, moderate or severe depression). The final treatment decision remained with providers, who could decide that no depression treatment was necessary. Friendship Bench was considered to be completed after six sessions. Antidepressant treatment was to be maintained for at least 3 months, with symptoms reassessed monthly and the dose increased if the PHQ-9 score remained 10 or above. All study sites had access to amitriptyline and fluoxetine, the two antidepressants procured by the national medical plan. All patients indicating suicidal thoughts or behaviours were assessed for safety with a suicide risk assessment protocol,17 with appropriate clinical follow-up.

The basic implementation strategy consisted of training and supporting an internal facility-based champion to spearhead EBI integration. Champions (ie, individuals within an organisation that advance EBI implementation) have shown feasibility and effectiveness in various clinical settings,18 and are a common strategy used to support the roll-out of new initiatives within Malawi’s health system. Two mechanisms have been proposed through which champions affect EBI use among providers: intention development and behavioural enactment.19 Intention development aligns providers’ social norms regarding the use of an EBI, whereas behavioural enactment builds their capacity for EBI implementation.19

Each facility’s leadership identified a champion and two alternates; alternates supported the champion and took over responsibilities if needed in case of attrition. Typically, the champion was the existing NCD coordinator, the clinical officer tasked with organising and overseeing NCD clinic services. Champions were responsible for training their fellow NCD providers in the EBI, arranging the NCD duty roster such that the clinic was staffed by clinicians trained in the EBI, supervising their providers in EBI delivery, ensuring accurate record keeping, tracking EBI delivery quality through monthly reporting, ensuring stable anti-depressant supply, and coordinating clinical care with Friendship Bench counsellors. The study team provided a 3-day, in-person training event and an annual refresher to both champions and alternates in the EBI and their champion role, and provided funds and support for them to lead their own 1-day, in-person training events locally. Champions received a monthly allocation for mobile phone use, similar to that received for comparable positions in district health leadership to support communication and report submission.

The enhanced strategy supplemented the basic strategy with additional regular external supervision visits, including audit and feedback. Audit and feedback strategies aim to improve service delivery by systematically and repeatedly providing feedback on performance metrics to service providers.20 These strategies harness social comparison and group reference theories, and impart change through several mechanisms related to comparing clinicians’ performance to benchmarks, trends, or explicit targets.21 This strategy has also been used within Malawi’s health system, notably to support the expansion of HIV treatment services; however, the related travel and expert staff time costs make this strategy substantially more resource-intensive in the Malawi context than the champion model.

An external supervision team of three to four members (ie, NCD, mental health, and Friendship Bench experts from the Malawi Ministry of Health and Population and partner organisations) visited each facility delivering the enhanced strategy approximately every 4 months. Each visit lasted 2–3 days and followed a structured protocol involving an opening meeting with facility leadership, the champion, alternates, and Friendship Bench counsellors; interviews with the champion, alternates, and Friendship Bench counsellors; structured assessment of depression care records that included a random selection of recent clinic attendees whose records were reviewed for documentation of screening outcomes, suicide risk assessment, and treatment decisions; observation of clinical care (typically observing one clinic day lasting several hours and covering multiple patients); observation of Friendship Bench counselling (typically one session), rated with a structured fidelity assessment sheet; a closing meeting with the same stakeholders to summarise successes, challenges, and recommendations identified; and a written report to the Ministry of Health and Population and facility leadership, outlining findings and recommendations. The full team joined the opening and closing meetings and prepared the report, whereas individual team members divided up the clinical and counselling observations, interviews, and record reviews.

Outcomes

Pre-specified10 primary outcomes were three indicators of EBI fidelity: depression screening fidelity, depression treatment initiation fidelity, and depression treatment follow-up fidelity. Data for primary outcomes were defined at the level of clinic visit, were captured from facility administrative records, and reflected the performance of all clinicians who provided care at the facility’s NCD clinic during the study period; clinicians did not consent individually.

Pre-specified secondary outcomes were two indicators of patient health captured from the enrolled patients: depression remission and well controlled hypertension at 3 months following enrolment. Additional outcomes included fidelity of antidepressant medication initiation, fidelity of suicide risk assessment, and patient outcomes at 6 and 12 months.

For fidelity of depression screening, the denominator was all screening-eligible visits (ie, visits where the patient was not already engaged in depression care) of patients with hypertension and diabetes during the study period and the numerator was all visits at which the PHQ-2 was completed and, if the PHQ-2 score was above 0, the PHQ-9 was also completed. For fidelity of depression treatment initiation, the denominator was all treatment-eligible visits (ie, screened visits with a PHQ-9 score of ≥5) and the numerator was the provider either referring the patient to Friendship Bench or prescribing antidepressant medication within 30 days. For fidelity of follow-up of depression treatment, the denominator was all attended return clinic visits in the first 3 months after starting depression treatment. For patients who started Friendship Bench, the numerator was either continuing counselling for at least six sessions or 3 months, or initiating antidepressant medication. For patients who started antidepressant medication, the numerator was receiving medication prescriptions for at least 3 months. Although the first two primary outcomes were measured among all eligible visits, the third outcome was only measured among consenting patients because it required linking patient identities across visits.

Depression remission was defined as a PHQ-9 score of less than 5 at follow-up. Well controlled hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg, following Malawi’s clinical guidelines for the management of NCDs. The trial had additionally intended to capture blood glucose concentration from medical records to assess for well controlled diabetes; however, this measure proved to be inconsistently recorded and was not available for analysis.

The run-in period lasted from May 9 to Sept 30, 2019, during which time clinical services were launched at all facilities with the support of the basic strategy group. Facilities were randomly assigned to the two interventions on Sept 30, 2019, and the randomised period and period of data collection for primary fidelity outcomes extended from Oct 1, 2019, to Nov 30, 2021. Eligible patients were enrolled during this same period and completed follow-up assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months after enrolment. The 3-month assessment was the pre-specified focus for patient outcomes, with 6 and 12 months added for further context.

Based on logistical and budget considerations, participant follow-up was scheduled to end on June 30, 2022. To maximise enrolment, participant enrolment continued until Dec 31, 2021; participants who were enrolled during the final months exited the study at the 6-month rather than 12-month assessment. At the end of the study, each facility provided the Ministry of Health and Population with a sustainability plan detailing how to maintain the integrated depression screening, treatment, and clinical record keeping activities moving forward.

Statistical analysis

The study population size was determined to provide 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 18–22 percentage points in the first primary cluster-level outcome (ie, screening fidelity) and an absolute difference of 11–15 percentage points in the secondary patient-level outcomes. The intended sample size was 60 000 visits for screening fidelity and 1160 patients for patient outcomes (appendix 1 p 1). The achieved study population size met the primary outcome target (60 000 visits), but was short of the secondary outcome target (589 patients). The achieved participant sample size conferred 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 12–16 percentage points in the secondary outcomes, close to the targeted 11–15 percentage points.

We completed intention-to-treat analyses for all pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes using a paired generalised estimating equations analysis, which included estimating equations for parameters in the population-averaged regression model and another set for intra-cluster correlations (ICCs) within clinics. To reduce potential bias from the small number of clusters, bias corrections were applied to standard error estimators (Mancl–Derouen) and in matrix-adjusted estimating equations for ICC estimates (appendix 1 pp 1–2).22–24 All pre-specified outcomes were binary and modelled by use of an identity link and binomial variance function to estimate probability differences (PDs) with 95% CIs without adjustment for covariates, which were approximately balanced owing to the randomisation scheme. All statistical tests were two-sided (α=0·05).

Pre-specified subgroup analyses examined differences in outcomes among patients with mild (PHQ-9 score 5–9) versus moderate or severe (PHQ-9 score 10–27) depressive severity at initial screening, among patients with hypertension alone versus diabetes alone versus both at baseline, and among patients with well controlled versus not well controlled hypertension at baseline.

No outcome measures were changed following study launch. However, the COVID-19 pandemic led to major disruptions in clinical care in Malawi in 2020–21. In April, 2020, all research follow-up assessments transitioned from in-person to telephone, and blood pressure measurements were not collected. Clinic-based research staff worked remotely from April to August, 2020, during the initial COVID-19 surge and again in February, 2021, during the beta variant (B.1.351) surge. Although clinical activities continued to a limited extent during these periods, record keeping, including the data sources for primary outcomes, was not reliable. Therefore, the decision was made before any analyses were performed to exclude all data collected for the primary outcomes between April 1 and Aug 31, 2020, and between Feb 1 and Feb 28, 2021. This trial and the study protocol are registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03711786, and the trial is complete.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

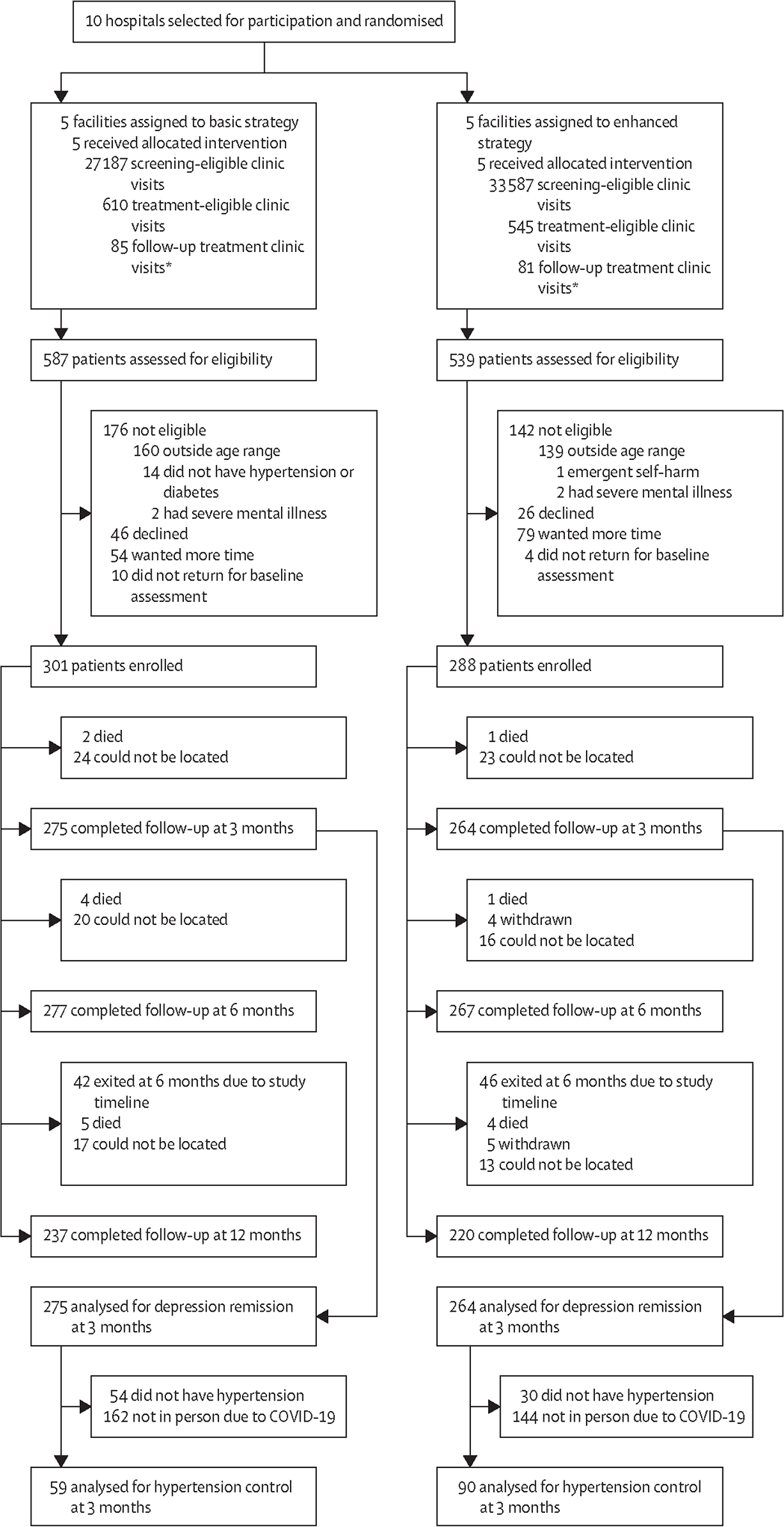

Ten facilities were randomised: five (50%) to the basic strategy and five (50%) to the enhanced strategy. All facilities received their assigned implementation strategy, completed the study, and were included in the analyses (figure 1). Between Oct 1, 2019, and Nov 30, 2021, for the three primary fidelity outcomes in the basic strategy group, there were 27 187 screening-eligible visits, 610 treatment initiation-eligible visits among all patients, and 85 follow-up visits for treatment of depression among consented patients. In the enhanced strategy group, there were 33 587 screening-eligible visits, 545 treatment initiation-eligible visits among all patients, and 81 follow-up visits for treatment of depression among consented patients.

Figure 1: Trial profile.

*Among consented patients.

In the basic group, of the 610 treatment initiation-eligible visits, 587 patients were assessed for eligibility, of whom 301 (51%) were enrolled. In the enhanced group, of 545 treatment initiation-eligible visits, 539 patients were assessed, of whom 288 (53%) were enrolled. The primary reasons for not enrolling were being outside the age range (aged >65 years) and either declining enrolment or wanting more time to consider enrolment; reasons were balanced between both groups. Among enrolled participants, 275 (91%) in the basic group and 264 (92%) in the enhanced group completed the 3-month assessment and were included in pre-specified analyses of secondary outcomes (figure 1). Additionally, 277 (92%) participants in the basic group and 267 (93%) in the enhanced group completed the 6-month assessment. In the basic group, 237 (92%) of the 259 participants who did not exit the study at 6 months completed the 12-month assessment; in the enhanced group, 220 (91%) of 242 participants completed this assessment.

During the run-in period, key clinic performance indicators were balanced between groups, including the proportion of clinic days staffed by EBI-trained clinicians, the proportion of patients screened for depression, and the proportion of patients indicated for depression treatment who were initiated on treatment (table). Enrolled participants were aged 50 years on average and over 75% were female. At clinical assessment, participants had a mean PHQ-9 score of 7·7, corresponding to mild depression.

Table:

Baseline clinic and participant characteristics

| Basic strategy group | Enhanced strategy group | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Clinics | ||

| Number randomised | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) |

| Clinic coverage by trained providers, %* | 74% (24) | 72% (15) |

| Depression screening, %* | 74% (17) | 72% (32) |

| Depression treatment initiation, %* | 92% (17) | 94% (10) |

| Patients per month | 441 (261) | 411 (275) |

| Participants | ||

| Number enrolled | 301 (51%) | 288 (49%) |

| Age, years | 51 (10) | 50 (10) |

| PHQ-9 score | 7·7 (2·9) | 7·7 (2·9) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 236 (78%) | 239 (83%) |

| Male | 65 (22%) | 49 (17%) |

| Non-communicable disease diagnosis | ||

| Hypertension alone | 185 (61%) | 204 (71%) |

| Diabetes alone | 59 (20%) | 34 (12%) |

| Hypertension and diabetes | 57 (19%) | 50 (17%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD). PHQ=Patient Health Questionnaire.

Data are continuous percentages ranging from 0% to 100% at the clinic level.

All clinics identified one primary and two alternate champions who received training, delivered training to clinicians at their facility, and oversaw the integration of treatment for depression during the study. Champions on average fulfilled 82% of their expected role as described above.25 All clinics in the enhanced group received seven rounds of external supervision over 26 months, which were completed following a structured visit guide and checklist to guide the external team in completing all components.

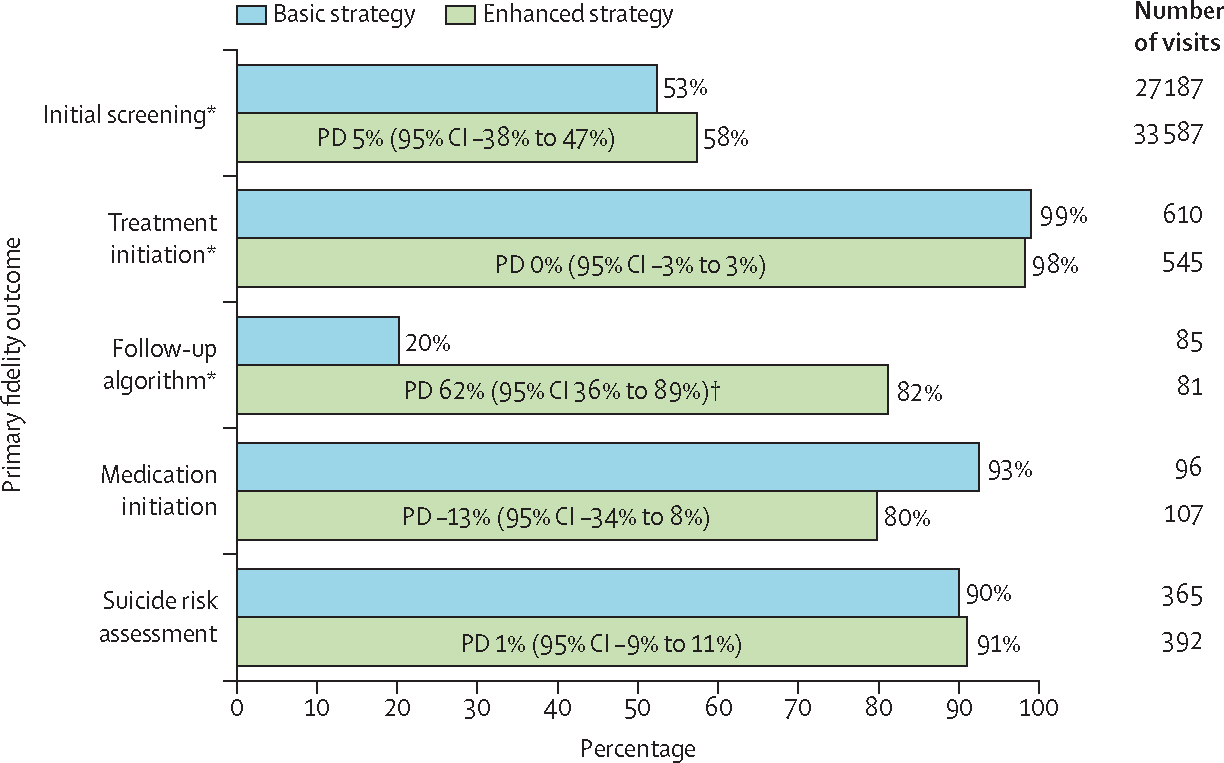

All reported outcome probabilities and PDs are estimated from models and might not correspond exactly to the numerator and denominator counts stated. Of the three pre-specified primary outcomes, initial screening fidelity was moderate (15 888/33 587 or 58% screening-eligible visits in the enhanced group vs 14 712/27 187 or 53% screening-eligible visits in the basic group; PD 5% [95% CI −38% to 47%]; p=0·84) and treatment initiation fidelity was high (538 [99%] of 545 visits vs 601 [98%] of 610 visits; PD 0% [−3% to 3%]; p=0·89); groups did not differ significantly (figure 2). Fidelity of depression treatment follow-up was notably higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group (69/81 visits or 82% vs 14/85 visits or 20%; PD 62% [36% to 89%]; p=0·0020; figure 2). In further descriptive exploration, follow-up fidelity was higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group both for patients who had been initiated on antidepressants (19 [90%] of 21 vs four [22%] of 18) and who had initially been referred to Friendship Bench counselling (50 [83%] of 60 vs 10 [15%] of 67). Nearly all patients (20 [95%] of 21 in the enhanced group and 16 [88%] of 18 in the basic group) initiated on antidepressants had PHQ-9 scores of less than 10 at follow-up clinic visits in the 3 months following treatment initiation, and fidelity was reached by continuing treatment. Only three patients (one [5%] in the basic group and two [11%] in the enhanced group) who initiated antidepressants had a PHQ-9 score of 10 or above at follow-up visits in the first 3 months of treatment, and none of these patients had their antidepressant dose adjusted upward as indicated by the algorithm (data not shown). Additional fidelity measures of medication initiation (80% in the enhanced group vs 93% in the basic group; PD −13% [95% CI −34% to 8%]; p=0·27) and suicide risk assessment (91% vs 90%; 1% [−9% to 11%]; p=0·85) did not show significant differences between groups.

Figure 2: Primary fidelity outcomes in the intention-to-treat population by intervention.

PDs provided with 95% CIs from generalised estimating equations with bias-corrected SEs. PD=probability difference. *Pre-specified primary outcome. †p<0·05.

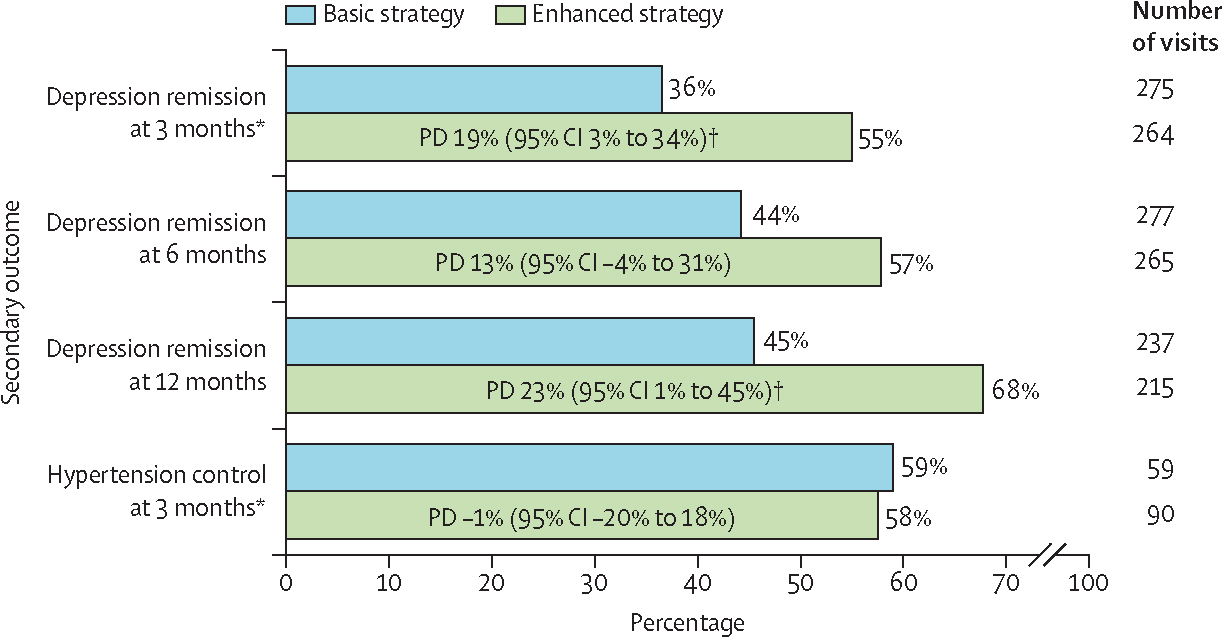

Depression remission 3 months after identification for treatment was notably higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group (138/264 or 55% vs 98/275 or 36%; PD 19% [95% CI 3% to 34%]; p=0·045; figure 3). This advantage for the enhanced group was similar in magnitude after 6 months (147/265 or 57% in the enhanced group vs 116/277 or 44% in the basic group; 13% [−4% to 31%]; p=0·14) and after 12 months (145/215 or 68% vs 102/237 or 45%; 23% [1% to 45%]; p=0·039), although significance varied. Although not pre-specified, in exploratory analyses, the proportion of participants with a 5-unit decrease in PHQ-9 score compared with baseline was higher in the enhanced group than in the basic group (35% vs 23% at 3 months, 41% vs 29% at 6 months, and 47% vs 32% at 12 months; data not shown). Well controlled hypertension did not show a significant difference between groups at 3 months (51/90 or 58% in the enhanced group vs 35/59 or 59% in the basic group; PD −1% [95% CI −20% to 18%]; p=0·93), with similar results at 6 and 12 months. ICC estimates for all outcomes are provided in appendix 1 (p 2).

Figure 3: Secondary patient health outcomes in the intention-to-treat population by intervention.

PDs provided with 95% CIs from generalised estimating equations with bias-corrected SEs. PD=probability difference. *Pre-specified primary outcome. †p<0·05.

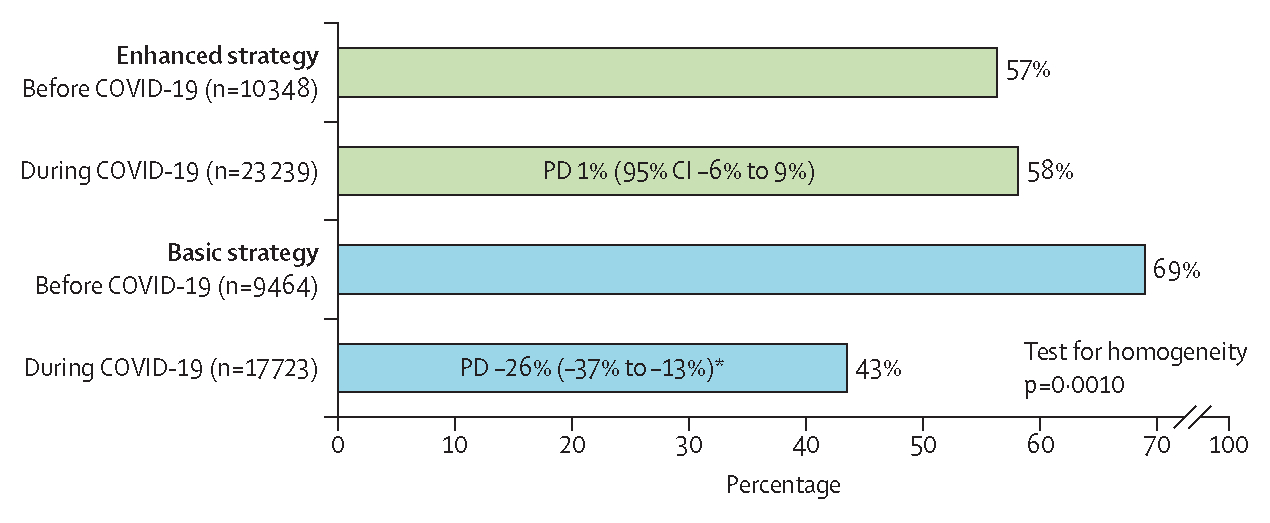

Interaction terms between group and time period (ie, before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic) were assessed in all outcome models. The only outcome showing a significant interaction with time period was screening fidelity (figure 4). Although the main effect model showed a small and non-significant advantage overall for the enhanced group in screening, the interaction model suggested that the enhanced group might have buffered its clinics against a substantial drop in screening that occurred in the basic group during the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 4). Although screening fidelity in the enhanced group remained nearly unchanged from before COVID-19 (57%) to during COVID-19 (58%; PD 1% [95% CI −6% to 9%]; p=0·73), screening fidelity in the basic group dropped substantially from 69% before COVID-19 to 43% during the COVID-19 period (−26% [−37% to −13%]; p<0·0001; test for homogeneity p=0·0010). Other pre-specified subgroup analyses did not identify any significant variation in effect size.

Figure 4: Change in clinic screening fidelity before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic by intervention.

PDs compare outcome frequency before vs during COVID-19 within each intervention group. PD=probability difference. *p<0·0001.

Five (2%) of 301 participants in the basic group and four (1%) of 288 in the enhanced group died while enrolled in the study, primarily of causes related to hypertension and diabetes (three [60%] in the basic group and two [50%] in the enhanced group) or COVID-19 (one [20%] in the basic group and one [25%] in the enhanced group; appendix 1 p 3). 20 hospitalisations were reported among 14 (5%) participants in the basic group and six hospitalisations were reported among six (2%) participants in the enhanced group, primarily cardiometabolic in origin. 56 participants reported a total of 60 instances of suicidal thoughts, of whom 17 (6%) participants were in the basic group and 39 (14%) were in the enhanced group. All events of suicidal thoughts were evaluated clinically for safety; the majority (68%) were evaluated to be passive (13 [76%] of 17 events in the basic group vs 28 [65%] of 43 events in the enhanced group), with 10% rated as active-low risk (one [6%] vs five [12%]), 20% as active-moderate risk (three [18%] vs nine [21%]), and one (6%) event in the enhanced group as active-high risk (appendix 1 p 3). All events of suicidal thoughts received appropriate care or referral based on the risk level following a study safety protocol.16 All adverse events were classified as not related to study participation and were reviewed by the study’s data and safety monitoring and institutional review boards.

Discussion

In this cluster-randomised trial of implementation strategies to support the integration of depression treatment into medical care for hypertension and diabetes staffed by general practice clinical officers and nurses, an enhanced implementation strategy (ie, an internal champion plus external supervision with audit and feedback) yielded a higher fidelity in follow-up decisions over depression treatment and better depression outcomes at 3, 6, and 12 months than did the basic implementation strategy (ie, a champion alone). Both strategies showed similar results in depression screening fidelity, treatment initiation fidelity, suicide risk assessment fidelity, and hypertension control.

These findings align with the literature on delivering depression treatment in non-specialist medical settings through approaches such as measurement-based care and collaborative care, indicating that follow-up decisions over the course of depression treatment are crucial in improving mental health outcomes.26,27 Integrating depression screening and treatment initiation into non-specialist medical care has proven to be easier than the follow-up steps (eg, reassessment of symptoms or side-effects, treatment continuation, and dose or medication adjustment) that are necessary to achieve improved mental health outcomes.28 Antidepressant treatment should be maintained for at least 6 months, even with symptom remission, and psychological therapies should be completed for maximum benefit.29 Furthermore, most antidepressants have a wide dosing range; although they are typically initiated at a low dose to minimise initial side-effects, the dose often needs to be gradually adjusted upward over follow-up visits to achieve remission.29

Our findings indicate that, although both strategies were sufficient in achieving moderate levels of screening coverage and high levels of treatment initiation, external supervision with audit and feedback could have been crucial in supporting follow-up fidelity, particularly guideline-concordant continuation of treatment, thereby affecting patient mental health. Audit and feedback strategies generally aim to improve service delivery by systematically and repeatedly providing performance metric feedback to service providers.20 One meta-analysis identified key characteristics as “delivered by a supervisor or respected colleague; presented frequently; featuring both specific goals and action-plans; aimed to [improve] the targeted behavior”,30 features consistent with this study’s enhanced strategy. Given the variation in the specifics of audit and feedback strategies in the literature on implementation, future research should focus on the optimal combination of elements for audit and feedback to have maximal impact.

Both strategies succeeded in integrating routine screening for depression, which was completely absent from all enrolled facilities before the study, and reaching more than 50% screening coverage. These findings suggest that the basic strategy can achieve moderate screening coverage for depression; however, additional efforts beyond the enhanced strategy are necessary to close the remaining gap. We previously reported qualitative data showing that facility leadership engagement and the strength of the champion–leadership relationship influenced integration success.25 Additional implementation strategies bolstering up-the-line leadership engagement31 could be necessary to further improve screening coverage for depression. This qualitative evaluation also underscored the acceptability of the EBI and implementation strategies to providers.25

Although screening fidelity was similar overall between both groups, there was suggestive evidence that the enhanced strategy protected against the unanticipated health system shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 substantially reshaped Malawi’s health-care system, including efforts to de-densify clinics by shortening patient visits, causing some clinics to de-prioritise the added time of depression screening. Qualitative findings suggest facilities supported by external supervision visits problem solved around these unexpected changes and maintained integrated care in ways that still met the needs of the public health emergency.32 No other outcomes showed any differences when comparing the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Primary care clinicians assessing patients for depression should apply their clinical judgement and training in deciding whether a high PHQ-9 score is a case of depression that merits treatment. The high initiation rate of depression treatment in this study might indicate that clinicians primarily relied on the PHQ-9 score alone. A focus on ensuring that non-specialist clinicians are equipped and supported in assessing depression beyond a single score will be important in future research.

This study’s implementation strategy involving a champion plus supervision with audit and feedback is a common implementation strategy,18,20 particularly relevant to Malawi and potentially other low-income countries. Like other similar countries, Malawi typically rolls out new health-care initiatives by having each district appoint an existing clinician as a coordinator or champion. Some initiatives are then supported by external supervision schedules similar in design to the current study. In particular, substantial expansion of antiretroviral treatment in Malawi has been achieved through district coordinators, combined with rigorous donor-supported external supervision. However, travel and personnel costs make external supervision expensive. Thus, evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding supervision is a highly policy-relevant question. A cost-effectiveness analysis for this study indicates that the enhanced strategy is highly cost-effective relative to usual care and to the basic model in cost per case of depression remission and in cost per disability-adjusted life-year saved.33

Strengths of this study include a research question strongly grounded in the health-care and policy context of Malawi and other similar low-income countries; a focus on a highly relevant evidence-based practice; a cluster-randomised design; constrained randomisation; primary implementation outcomes and secondary patient health outcomes, which together provide a comprehensive perspective on implementation strategy effects; high retention of participants; and a strong statistical approach, which appropriately addresses clustering and the small number of clusters. Furthermore, this research benefits from strong policy connections with key policy makers from the Ministry of Health on the investigator team, a partnership that has already led to research-informed changes in Malawi’s mental health policy and practice, including the adoption of a national policy prioritising integrated mental and general medical care.

This study’s facility-level intervention required facility-level randomisation, which constrained the possible sample size. We mitigated this limitation through constrained randomisation based on three facility-level continuous covariates and observed a balance in key prognostic factors; however, we cannot rule out an unobserved imbalance. To avoid potential computational problems, our identity link regression models for the binary outcomes did not adjust for covariates. Although this step might have reduced power, our analyses correctly controlled for type I errors through our small sample corrections. Our measure of fidelity of depression treatment initiation might be underestimated, given that we did not capture information on whether clinicians decided that some patients with PHQ-9 scores of 5 and above did not require treatment. However, fidelity of treatment initiation was more than 98% overall and did not differ between both groups. Our implementation outcomes were abstracted from clinical records; research assistants were embedded to ensure that these data were accurately captured. These individuals only abstracted medical records, consented patients, and conducted follow-up interviews; they followed strict protocols not to influence clinical care or implementation strategies.

In summary, these findings suggest that an enhanced implementation strategy of an internal champion combined with external supervision with audit and feedback could offer an important advance in integrating treatment for depression into general medical care in low-resource settings. Both the basic strategy and enhanced strategy were successful in achieving moderate screening coverage for depression and a high initiation rate of depression treatment. However, in the enhanced strategy group, clinicians were much more likely to sustain patients on treatment for the recommended duration and patients had a higher rate of reaching and maintaining depression remission for up to 12 months than in the basic strategy group. Approaches comprising an internal champion plus external supervision are commonly used health system strategies that support system change, particularly in low-income countries such as Malawi, and this research suggests that the combination of these strategies could be important in advancing the agenda of expanded access to integrated depression care in low-resource settings.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Depression is among the top contributors to the global burden of disease, especially in low-income and middle-income countries. Evidence-based practices for the treatment of depression in low-resource settings are established; however, implementation strategies to integrate these treatments into medical care at scale remain poorly defined. We searched PubMed, with no language restrictions, for peer-reviewed literature published from database inception to Nov 1230, 2023, on evidence-based treatments for depression in low-income countries and implementation strategies used to integrate mental health treatment into general medical care, using combinations of a large list of search terms. Examples of search terms include “depression”, “screening”, “antidepressant”, “psychosocial counseling”, “problem-solving therapy”, “integration”, “measurement-based care”, “collaborative care”, “task-shifting”, “Malawi”, “low-income country”, and “implementation strategy”. This search identified high-quality systematic reviews supporting the effectiveness of measurement-based care for individuals with depression in both high-income and low-income settings and of task-shifted psychological treatments for those with depression in low-income countries. No meta-analysis was performed

Added value of this study

This study indicates that, in low-resource settings with no pre-existing integrated mental health care, such as Malawi, an internal champion strategy might be sufficient to achieve moderate integration of depression screening and treatment initiation. However, this approach alone is not enough to achieve the follow-up care needed to ensure depression remission. The addition of an external supervision strategy with audit and feedback led to increased rates of appropriate follow-up care, leading to improved mental health outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Combined with the previous literature, these findings suggest that facility-level implementation strategies of an internal champion combined with external supervision with audit and feedback could offer an important advance in integrating depression treatment into general medical care in low-resource settings

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (grant number U19MH113202). This manuscript is the work of the authors and does not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

JMD received support from the National Institutes of Health (T32AI070114). YZ and JSP received support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (grant award number UL1TR002489). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Equitable partnership declaration

The authors of this paper have submitted an equitable partnership declaration (appendix 2). This statement allows researchers to describe how their work engages with researchers, communities, and environments in the countries of study. This statement is part of The Lancet Global Health’s broader goal to decolonise global health.

Contributor Information

Brian W Pence, Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Bradley N Gaynes, Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Michael Udedi, Division of Non-Communicable Diseases and Mental Health, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Kazione Kulisewa, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, Blantyre, Malawi.

Chifundo C Zimba, UNC Project Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Christopher F Akiba, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Josée M Dussault, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

Harriet Akello, UNC Project Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Jullita K Malava, Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Amelia Crampin, Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Ying Zhang, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

John S Preisser, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Stephanie M DeLong, Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Mina C Hosseinipour, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; UNC Project Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Data sharing

The individual de-identified data used for the analyses reported in this Article, along with data dictionaries, will be available for researchers to access on the Mendeley Data sharing platform. Data will be made available upon publication of the paper and will remain on the Mendeley Data platform indefinitely.

References

- 1.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021; 398: 1700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007; 370: 851–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, et al. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet 2007; 370: 1061–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udedi M Improving access to mental health services in Malawi. July, 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael-Udedi/publication/306065762_Improving_access_to_mental_health_services_in_Malawi/links/57ad984108ae7a6420c4eb07/Improving-access-to-mental-health-services-in-Malawi.pdf (accessed May 25, 2023).

- 6.Ahrens J, Kokota D, Mafuta C, et al. Implementing an mhGAP-based training and supervision package to improve healthcare workers’ competencies and access to mental health care in Malawi. Int J Ment Health Syst 2020; 14: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Rush AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 1439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2017; 13: 149–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagenaar BH, Turner M, Cumbe VFJ. Toward 90–90-90 goals for global mental health. JAMA Psychiatry 2022; 79: 1151–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaynes BN, Akiba CF, Hosseinipour MC, et al. The Sub-Saharan Africa Regional Partnership (SHARP) for mental health capacity-building scale-up trial: study design and protocol. Psychiatr Serv 2021; 72: 812–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson LM, Hosokawa P, Waxmonsky JA, Kwan BM. The problem of imbalance in cluster randomized trials and the benefits of covariate constrained randomization. Fam Pract 2021; 38: 368–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Henninger ML, Thomas RG, Gaynes BN. Depression and suicide risk screening: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2023; 329: 2068–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chibanda D, Weiss HA, Verhey R, et al. Effect of a primary care-based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 316: 2618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udedi M, Muula AS, Stewart RC, Pence BW. The validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry 2019; 19: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bengtson AM, Filipowicz TR, Mphonda S, et al. An intervention to improve mental health and HIV care engagement among perinatal women in Malawi: a pilot randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav 2023; 27: 3559–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockton MA, Udedi M, Kulisewa K, et al. The impact of an integrated depression and HIV treatment program on mental health and HIV care outcomes among people newly initiating antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0231872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landrum KR, Akiba CF, Pence BW, et al. Assessing suicidality during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: lessons learned from adaptation and implementation of a telephone-based suicide risk assessment and response protocol in Malawi. PLoS One 2023; 18: e0281711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med 2018; 6: 2050312118773261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv 2022; 2: 896885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 6: CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gude WT, Brown B, van der Veer SN, et al. Clinical performance comparators in audit and feedback: a review of theory and evidence. Implement Sci 2019; 14: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancl LA, DeRouen TA. A covariance estimator for GEE with improved small-sample properties. Biometrics 2001; 57: 126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu B, Preisser JS, Qaqish BF, Suchindran C, Bangdiwala SI, Wolfson M. A comparison of two bias-corrected covariance estimators for generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 2007; 63: 935–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preisser JS, Lu B, Qaqish BF. Finite sample adjustments in estimating equations and covariance estimators for intracluster correlations. Stat Med 2008; 27: 5764–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akiba CF, Go VF, Powell BJ, et al. Champion and audit and feedback strategy fidelity and their relationship to depression intervention fidelity: a mixed method study. SSM Ment Health 2023; 3: 100194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Henninger ML, Thomas RG, Gaynes BN. Depression and suicide risk screening: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2023; 329: 2068–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2023; 329: 2057–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004; 25: 119–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qaseem A, Owens DK, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Tufte J, Cross JT Jr, Wilt TJ. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments of adults in the acute phase of major depressive disorder: a living clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2023; 176: 239–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Jamtvedt G, et al. Growing literature, stagnant science? Systematic review, meta-regression and cumulative analysis of audit and feedback interventions in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29: 1534–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, Hurlburt MS. Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): a randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implement Sci 2015; 10: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sansbury GM, Pence BW, Zimba C, et al. Improving integrated depression and non-communicable disease care in Malawi through engaged leadership and supportive implementation climate. BMC Health Serv Res 2023; 23: 1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yanguela J, Pence BW, Udedi M, et al. Implementation strategies to build mental health-care capacity in Malawi: a health-economic evaluation. Lancet Glob Health 2024; published online Feb 23. 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00597-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The individual de-identified data used for the analyses reported in this Article, along with data dictionaries, will be available for researchers to access on the Mendeley Data sharing platform. Data will be made available upon publication of the paper and will remain on the Mendeley Data platform indefinitely.