Abstract

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immunemediated skin disease characterized by scaly, erythematous, pruritic plaques. The effects of psoriasis are often debilitating and stigmatizing, significantly impacting patients’ physical and psychological well-being and quality of life. Current guideline-recommended psoriasis therapies (topicals, oral systemics, and biologics) have substantial limitations that include overall efficacy, safety, tolerability, sites of application, disease severity, and duration and extent of body surface area treated. Due to these limitations, psoriasis treatment regimens often require combination therapy, especially for moderate to severe disease, leading to increased treatment burden. Psoriasis is also associated with increased indirect costs (eg, reduced work productivity), leading to greater total costs expenditures. Thus, more effective, safe, well-tolerated, and cost-effective therapeutic options are needed. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily is a first-in-class, nonsteroidal, topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2022 for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults. Tapinarof cream has been evaluated in plaque psoriasis, including 2 pivotal phase 3 trials (NCT03956355 and NCT03983980) and a long-term extension trial (NCT04053387). These trials demonstrated high rates of complete skin clearance with tapinarof cream, durable effects while on treatment (a lack of tachyphylaxis for up to 52 weeks), an approximately 4-month remittive effect off therapy after achieving complete clearance and stopping treatment (ie, duration during which psoriasis does not recur off therapy), and no rebound effects after cessation of therapy. According to the US Food and Drug Administration–approved prescribing information, tapinarof may be used to treat plaque psoriasis of any severity and in any location, has no restrictions on duration of use or extent of total body surface area treated, and has no contraindications, warnings, precautions, or drug-drug interactions. Tapinarof cream is thus an efficacious, well-tolerated, steroid-free topical option that addresses many of the limitations of current recommended therapies. Here we review current knowledge on the physical, psychological, and financial burdens of plaque psoriasis and identify how the clinical profile of tapinarof cream can address key treatment gaps important in the management of plaque psoriasis and patient quality of life. In this article, we aim to assist pharmacists and other managed care practitioners by providing an evidence-based overview of tapinarof cream to support patient-centric decision-making.

Plain language summary

Psoriasis is a long-term disease that reduces quality of life and can be costly to manage. Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA) once daily is effective and well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis. Tapinarof is not a steroid cream and works in a unique way to treat psoriasis. Unlike most other prescription psoriasis medications that are applied to the skin, tapinarof can be used for as long as needed, including on sensitive skin, without limits on the total area of skin treated.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

This article can help managed care practitioners evaluate tapinarof for formulary coverage based on its clinical efficacy and other attributes. Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA) once daily, a first-in-class, nonsteroidal, topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, is efficacious and well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis for up to 1 year. Topical therapies are the mainstay of psoriasis treatment, but most have limitations specified in their prescribing information because of the risk of adverse effects. Tapinarof addresses gaps in the treatment armamentarium for an effective topical medication with no US Food and Drug Administration–mandated limitations on duration of use, extent of body surface area treated, or locations of use and no known contraindications, warnings, precautions, or drug-drug interactions cited in the prescribing information.

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated skin disease involving inflammation and skin barrier dysfunction.1-3 It is characterized by scaly, erythematous, pruritic plaques of varying severity that can occur anywhere on the skin.3 The effects of psoriasis are often debilitating and stigmatizing, significantly affecting patients’ daily activities, social functioning, psychological well-being, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).4,5 In addition, the management of psoriasis is associated with substantial health care resource use and costs.6 Although several therapies are approved for psoriasis, the associated cost burden contributes substantially to overall health care expenditure. The extent of this burden is also dependent on disease severity, as approximately 5-times higher health care costs are associated with moderate to severe psoriasis than those associated with mild to moderate disease.7

Topical therapies are the mainstay of psoriasis treatment and may be used independently for mild to moderate disease or used alone or in combination with other therapies (eg, phototherapy, systemic, or biologic therapy) for severe disease.8 Guideline-recommended topicals for psoriasis are limited in terms of efficacy and have restrictions on duration, extent of body surface area treated, and sites of application due to potential adverse events, some of which are irreversible.1 Consequently, more effective, safe, and well-tolerated options are needed.

Tapinarof (VTAMA) is a first-in-class, nonsteroidal, topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022 for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.9 Tapinarof cream 1% once daily is also under investigation for the treatment of psoriasis in children as young as age 2 years (NCT05172726) and for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in both adults and children as young as age 2 years (NCT05014568, NCT05032859, and NCT05142774). This review aims to assist pharmacists and other managed care practitioners by presenting the clinical profile of tapinarof cream and how it may address the gaps in current psoriasis treatment options to improve outcomes.

Disease Background

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Psoriasis has a complex pathophysiology involving inflammation and immune activation resulting from skin barrier dysfunction, oxidative stress, environmental triggers, and/or genetic factors.1,3,10 Chronic inflammation in psoriasis is characterized by increased levels of T-helper (Th)17 cells that lead to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-17A and IL-17F.1,2,11 Psoriasis is also characterized by excessive growth of keratinocytes in the epidermis and reduced production of barrier proteins (including filaggrin and loricrin), resulting in skin barrier dysfunction.3,12,13 Another factor, oxidative stress, contributes to the pathogenesis of psoriasis through epidermal hyperplasia, increased dermal inflammation, and compromised skin barrier functions.10,12,14 Environmental factors may also trigger psoriasis through physical skin trauma, extremes of weather, chemical irritants, oxidizing agents, exposure to certain drugs, infections, and various lifestyle factors.1,2,15 Multiple transcription factors that control the expression of a range of genes may also be upregulated in psoriasis.16

AhR is a ligand-dependent transcription factor and “master regulator” that modulates processes in a range of cells, including immune and epithelial cells.17,18 In healthy skin, AhR signaling plays an integral part in maintaining skin homeostasis by regulating immune responses, cell differentiation, skin barrier function, and oxidative stress.17,19 AhR expression is upregulated in lesional skin of patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases (eg, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis).20,21

BURDEN OF ILLNESS

In the United States, psoriasis affects approximately 3% of adults, with an incidence rate of 63.8 per 100,000 person-years.1,22 Plaque psoriasis makes up 80%-90% of psoriasis cases.23 Approximately 80% of patients with plaque psoriasis have mild or moderate disease; the remaining 20% have moderate to severe disease.24

Patients with psoriasis report that physical burdens, primarily skin symptoms, have the most significant impact on their daily life.25,26 A wide range of physical burdens are commonly associated with psoriasis: more than 80% of patients report skin flaking or scaling, more than 73% report itching, and 32% report pain or soreness.27 Patients with psoriasis are also at increased risk of psychological comorbidities, with many experiencing more anxiety symptoms (22.7% vs 11.1%; odds ratio [OR] = 2.91, 95% CI = 2.01-4.21), suicidal ideation (17.3% vs 8.3%; OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.33-2.82), and depression (13.8% vs 4.3%; OR = 3.02, 95% CI = 1.86-4.90), compared with individuals without psoriasis.28 A US National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) survey reported that psoriasis is detrimental to overall emotional well-being for 88% of patients, with most experiencing anger (89%), frustration (89%), helplessness (87%), embarrassment (87%), and self-consciousness (89%).29

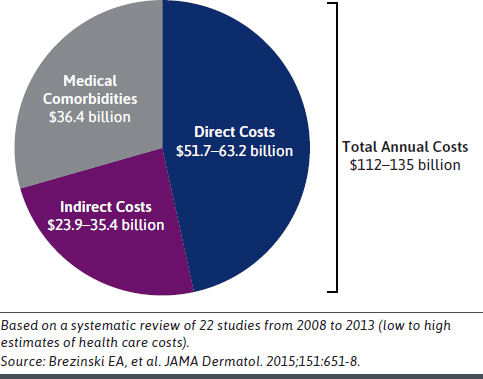

In addition to its impact on health and well-being, psoriasis is associated with a substantial economic burden (Figure 1).30 The total annual US cost of psoriasis was $112-$135 billion in 2013, with an upward trend of 36% over 5 years.30,31 Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis have substantially higher total health care costs (approximately 5-fold) and pharmacy expenditures (10-fold) than those with mild disease.7,31 In addition to direct costs associated with psoriasis treatment (eg, specialist evaluations, hospitalization, prescription/over the counter medications, laboratory tests/monitoring, and administration), indirect costs, including absenteeism and presenteeism, contribute an estimated 24% of total costs (Figure 1).30,32 Of these, presenteeism costs make up the majority of indirect costs (approximately 96%) in the United States.32 Additionally, a US study evaluating data between 2006 and 2019 demonstrated that patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher health care resource utilization associated with comorbidities than the general population (eg, mental health $911 vs $538; diabetes $658 vs $500; hyperlipidemia $723 vs $521; hypertension $841 vs $535; peripheral vascular disease $1,496 vs $509; and liver disease $689 vs $329 [all P < 0.0001]).33 The higher health care costs and resource utilization associated with comorbidities is due to a higher incidence of these comorbidities among people with psoriasis than the general population.

FIGURE 1.

Pharmacy Expenditure Is the Largest Driver of Psoriasis Health Care Costs in the United States

CURRENT APPROACHES TO TREATMENT

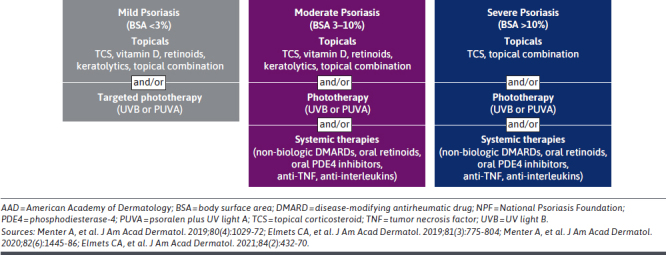

The American Academy of Dermatology and NPF treatment guidelines recommend treatment escalation with greater disease severity, with topicals as a mainstay of treatment (± phototherapy, ± systemic therapies including orals and biologics) (Figure 2).8,34-36 The primary goals of psoriasis treatment are to achieve clear skin (with no flaking and scaling); to improve symptoms such as itch, pain, and soreness; and to restore patients’ HRQoL, functioning, and ability to perform activities of daily living.37-39 Treatment is usually chosen on the basis of disease severity, plaque location, relevant comorbidities, patient preference (including convenience and costs), efficacy, and evaluation of individual patient responses.40,41 Regardless of disease severity, topical therapies remain the mainstay of treatment.12,42 However, more than 1 topical medication is often required to treat disease in different body regions, especially for sensitive skin areas (eg, skin flexures and the face).42,43 As such, topical therapies are frequently used adjunctively, particularly with phototherapy and/or systemic therapy.8,43 The most commonly used topicals for psoriasis include topical corticosteroids and–to a lesser extent–vitamin D analogs (ie, calcipotriene/calcipotriol and calcitriol) and the topical retinoid, tazarotene.8,43 Therapy is typically intensified using systemic treatments and/or phototherapy when there is insufficient efficacy with topicals against symptoms or psoriasis-related comorbidities (eg, for psoriatic arthritis).1,40

FIGURE 2.

Summary of AAD-NPF Treatment Guidelines

FDA-approved oral systemic psoriasis medications include methotrexate and cyclosporine (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs), apremilast (a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor), acitretin (a retinoid), and deucravacitinib (a selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor).34,40 Biologics approved by the FDA to treat psoriasis include injectable tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and interleukin inhibitors (ie, inhibitors of IL-17, IL-23, and IL-12/IL-23).35,40

Almost all approved systemic and biologic psoriasis medications are for moderate or severe disease that has not been adequately controlled with topical medications and phototherapy.5,40

TREAT-TO-TARGET GOALS FOR PSORIASIS

Treat-to-target strategies are used in several chronic diseases to improve outcomes.44-46 Treatment goals for psoriasis have been recommended by the NPF (eg, achieving a percentage body surface area [%BSA] affected of ≤1.0% at 3 months), and the European S3-Guidelines on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis (eg, achieving a ≥75% decrease in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI75] within 3–4 months).47,48 Unfortunately, many patients fail to meet these targets in clinical practice.41,49 Generally, the use of approved topical treatments alone is insufficient to reach these treatment goals.50 A global study found that 57% of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis had not achieved clear/almost clear skin, regardless of whether systemic or topical agents were used independently or in combination.50

UNMET TREATMENT NEEDS

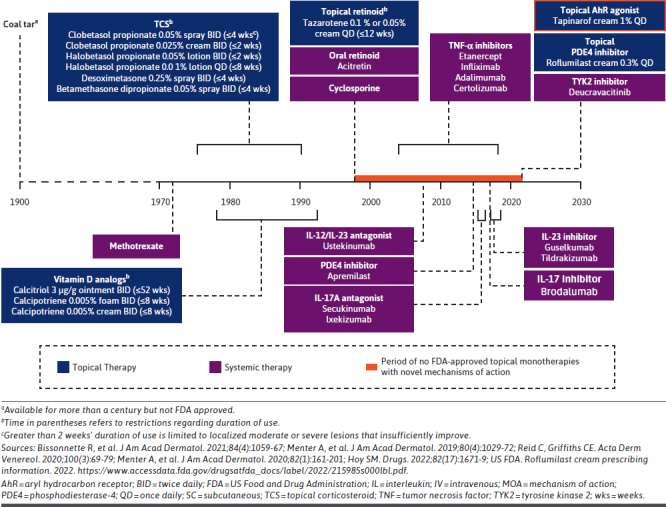

Limitations With Current Psoriasis Therapies. Conventional treatment modalities for psoriasis have potential limitations in terms of overall efficacy, safety, and tolerability over time.25 For example, phototherapy is often inconvenient to access and may be associated with an increased risk of cutaneous malignancies.36,51 The introduction of biologics and systemic agents targeting key immune pathways, such as the IL-23/IL-17 axis, significantly advanced treatment. However, most biologics have potential limitations in terms of cost, loss of response over time, safety concerns, and restrictions on use for moderate and severe disease only.52-54 Conventional topicals are used by the majority of patients with psoriasis; however, most (topical corticosteroids in particular) have restrictions on sites of application, duration, and extent of use.8,12 Topical corticosteroids may not be used on intertriginous or sensitive skin such as the face, axillae, genitalia, or groin.12 Other topical agents, such as calcipotriene and tazarotene, have well-documented adverse events and tolerability issues, such as skin irritation.12 Furthermore, frequency of administration is also restricted because repeated use of topical corticosteroids in particular may increase the risk of irritation and adverse events, including irreversible ones such as skin atrophy, striae (stretch marks), telangiectasias (spider veins), and pigmentation changes.8 Consequently, the treatment duration of FDA-approved topical corticosteroids for psoriasis is restricted depending on potency, with some only allowing a maximum of 2 weeks’ use (Figure 3).8,40,55 This is of importance as chronic diseases, such as psoriasis, require repeated, continuous or intermittent long-term treatment.23 Not only do these limitations diminish the effectiveness of therapy over time, they may also lead to the recurrence of symptoms, sometimes with greater severity.8 As such, the limitations and restrictions of conventional topicals often require that multiple agents are used as concomitant therapy.5,8

FIGURE 3.

Introduction of Tapinarof in 2022 Marked the First FDA Approval of a Novel Topical Psoriasis Monotherapy in More Than 25 Years

Rates of Adherence and Dissatisfaction With Psoriasis Treatments. Patients’ rates of treatment adherence vary depending on the psoriasis therapy, ranging from 29% to 75% for topical agents, 62% to 97% for oral therapy, and 41% to 100% for biologics.56,57 Overall, a substantial proportion of patients remain dissatisfied with their current psoriasis treatment regimen (52%), leading to switching, adding on therapies, or discontinuation.58,59 Patient satisfaction with therapy is closely linked to treatment adherence and is of high importance when evaluating improvements in therapy.60,61 Key challenges relating to patient adherence and satisfaction are loss of efficacy, fear of adverse events, frequency and difficulty of daily application of topicals plus the associated time burden, and formula properties (eg, texture and odor).56,61,62

Unmet Need for Effective and Well-Tolerated Topical Medication. Maintaining patients on an effective topical treatment may minimize the need to switch or add systemic oral or biologic therapies.63 Although topical corticosteroids are efficacious, clinicians and patients have concerns relating to their long-term use, especially when high-potency topical corticosteroids are used.64-66 Extensive use of topical corticosteroids can also cause suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in adrenal insufficiency.67 Adverse events associated with topical corticosteroids include acne, rosacea, perioral dermatitis, facial erythema, hirsutism, skin thinning and atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, ecchymosis, and withdrawal phenomena.64,65 Conventional topical agents remain the most frequently used treatment despite their limitations, restrictions on use, suboptimal patient adherence, adverse events, and lack of treatment satisfaction.1,12 Despite the importance of topical therapeutics for psoriasis, there had been no FDA-approved topicals comprising new chemical entities for more than 25 years prior to the approval of tapinarof (Figure 3).12,35,68-71 Addressing the limitations of conventional therapies may be expected to impact the considerable economic burden of psoriasis on health care costs and effects on patients’ HRQoL. Consequently, there is a need for a topical agent that is efficacious, well tolerated, and not limited by restrictions on duration, extent of body surface area treated, or sites of application. Furthermore, there is a need for psoriasis treatment options that encompass a wider range of disease severities and that can be used as first-line therapy without requiring prior treatment failure or in combination without risk of drug-drug interactions.

Mechanism of Action of Tapinarof in the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis

Tapinarof cream 1% is a first-in-class, topical AhR agonist that was approved by the FDA in May 2022 for the treatment of adults with plaque psoriasis.9 The vehicle in tapinarof cream is specifically designed to reduce skin irritation, have an emollient effect, and optimize delivery of the active agent.72 Tapinarof cream is cosmetically elegant, steroid-free, and free from fragrance, petrolatum, parabens, and gluten.72 Patients generally prefer cosmetically elegant topical medications, meaning formulations that are easy to apply, quickly absorbed, not greasy, not sticky, and free from unpleasant odors or added fragrances.37,72-74

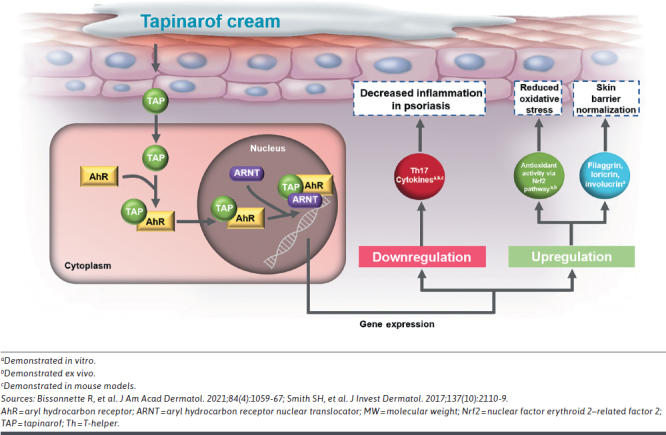

In vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo models of the biologic effects of tapinarof identified unique ligand-dependent activation of AhR. Key responses following AhR activation include decreased proinflammatory cytokines implicated in psoriasis (eg, IL-17A and IL-17F), decreased oxidative stress, regulation of skin barrier proteins, and re-establishing skin homeostasis (Figure 4).12,75

FIGURE 4.

Biologic Effects of Tapinarof

Biologic effects implicated in the clinical efficacy of tapinarof in patients with psoriasis include the suppression of Th17/Th22 proinflammatory cytokines, IL-17 and IL-22.12,75 Tapinarof-mediated activation of AhR has also been shown to induce expression of skin barrier genes, such as filaggrin, loricrin, and involucrin, which are downregulated in psoriasis.12,75 Tapinarof also downregulates skin resident memory T-cells, which may explain the remittive effect observed following cessation of tapinarof treatment in the long-term extension trial PSOARING 3.76,77 Tapinarof is the only topical therapy to demonstrate a remittive effect (median of approximately 4 months) and have this included in the FDA-approved prescribing information.9 The 4-month remittive effect with tapinarof represents the duration of time that patients who achieved completely clear skin remained clear or almost clear off therapy, ie, after tapinarof was withdrawn per protocol, in the long-term PSOARING 3 trial.9,76

In addition to its biologic effects, tapinarof has antioxidant properties that reduce oxidative stress associated with the pathogenesis of inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis.12 The antioxidant effects of tapinarof are both intrinsic (via direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species) and through activation of the AhR–nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 transcription factor pathway.12,75

Tapinarof cream has limited systemic exposure, even under maximal usage conditions in patients with extensive psoriasis and severe disease affecting at least 20% of their body surface area.78 This favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profile is consistent with targeted local effects at sites of application and low potential for systemic adverse effects and drug-drug interactions.78

Efficacy of Tapinarof Cream for Psoriasis

PHASE 3 PIVOTAL TRIALS: PSOARING 1 AND PSOARING 2

Tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle in 2 identically designed 12-week, pivotal, phase 3 trials–PSOARING 1 (NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)–that enrolled 1,025 adults with mild (~10%), moderate (~80%), or severe (~10%) plaque psoriasis.42 An identical vehicle (without active drug) was used as the control.

The primary efficacy endpoint was an FDA-mandated Physician Global Assessment (PGA) response, defined as a PGA score of 0 “clear” or 1 “almost clear” and at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline at Week 12.42 PGA is rated by investigators on a scale from 0 “clear” to 4 “severe,” with higher scores indicating worsening psoriasis.42 The PGA response primary endpoint combines both an absolute improvement (to clear or almost clear) and a relative improvement of at least 2 points from baseline. A PGA response was achieved by a significantly higher proportion of patients in tapinarof groups than vehicle in both PSOARING 1 (35.4% vs 6.0%, P < 0.0001) and PSOARING 2 (40.2% vs 6.3%, P < 0.0001).42,79

All secondary efficacy endpoints were also achieved with statistical significance.42,79 The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) is widely used in psoriasis trials to grade disease severity and response to treatment using a numeric score ranging from 0 to 72, with higher scores indicating more severe disease. A PASI75 response (defined as at least a 75% improvement in PASI score) at Week 12 was achieved by a significantly higher proportion of tapinarof-treated patients than with vehicle in PSOARING 1 (36.1% vs 10.2%, P < 0.0001) and PSOARING 2 (47.6% vs 6.9%, P < 0.0001).42,79 Additionally, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the tapinarof arms than vehicle arms had a PASI90 response (defined as at least a 90% improvement in PASI score) at Week 12: (18.8% vs 1.6%, P = 0.0005 and 20.9% vs 2.5%, P < 0.0001, in PSOARING 1 and 2, respectively).42,79 A significantly greater improvement in %BSA affected at Week 12 was achieved with tapinarof compared with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and 2 (−3.5% vs −0.2%, P < 0.0001 and −4.2% vs 0.1%, P < 0.0001, respectively).42

PSOARING 3 LONG-TERM EXTENSION TRIAL

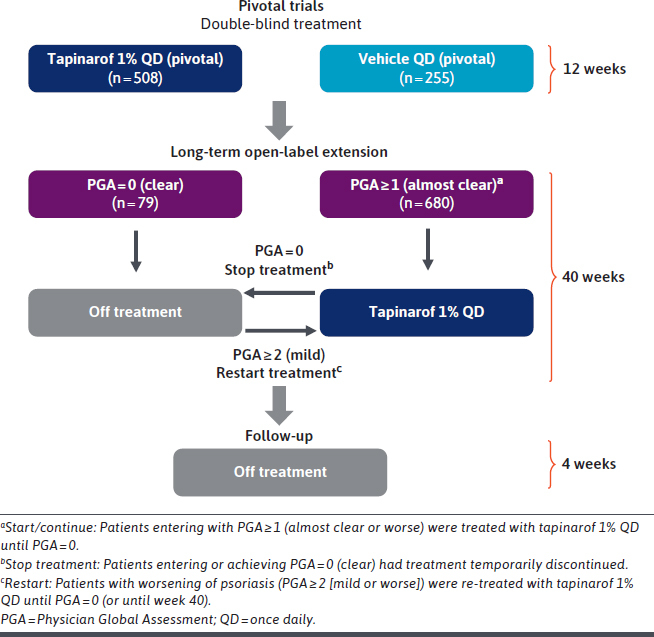

In total, 92% (n = 763) of eligible patients in PSOARING 1 and 2 chose to enroll in PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387) and receive open-label tapinarof cream 1% once daily for 40 weeks with 4 weeks of follow-up.76 The design of PSOARING 3 is described in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Design of the Phase 3 Long-Term Clinical Trial of Tapinarof Cream (PSOARING 3) for the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis in Adults

In PSOARING 3, tapinarof cream demonstrated continued efficacy with long-term use beyond the improvements already seen in the 12-week pivotal trials.76 Complete disease clearance, defined as the proportion of patients achieving a PGA score of 0, was achieved by 41% (n = 312/763) of patients. Among individuals entering the trial with a PGA score of at least 2, 58.2% (n = 302/519) achieved a PGA score of 0 or 1 at least once during the 40-week period.76

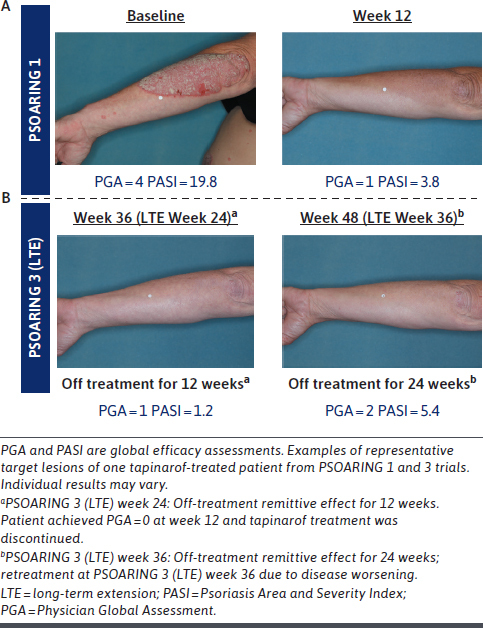

A median 4-month remittive effect was observed, defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 “clear” or 1 “almost clear” while off therapy for patients first achieving completely clear skin (PGA = 0) at any time during the long-term trial (41%; n = 312/763).76 Representative clinical case photography of responses observed in tapinarof-treated patients across the pivotal trials and PSOARING 3 illustrates the off-therapy remittive effect that persisted for 24 weeks during PSOARING 3 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Clinical Response and Remittive Effect in a Patient With Plaque Psoriasis Treated With Tapinarof Cream 1% Once Daily: Representative Target Forearm/Elbow Lesion

If worsening of psoriasis occurred while off therapy during PSOARING 3, defined as a PGA score of at least 2 (mild), tapinarof was reinitiated until patients regained completely clear skin (PGA = 0). This pattern of treatment, discontinuation, and retreatment continued until trial end, resulting in patients receiving tapinarof continuously or intermittently.76

TREAT-TO-TARGET OUTCOMES

Treat-to-target strategies are used in a range of chronic diseases to improve outcomes, and treatment goals for psoriasis have been recommended by the NPF and the European S3-Guidelines on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis.47,48 However, goals are often challenging for patients with psoriasis to achieve, even with systemic treatments.41

In pooled analyses of the PSOARING trials, aggressive treatment targets for PASI total scores (≤3, ≤2, or ≤1) and %BSA (≤1% or ≤0.5%) were achieved with tapinarof cream monotherapy.80 These targets were achieved with tapinarof despite the challenges of meeting them with available systemic, biologic, topical, and combination therapies. The analyses indicated that 40% of patients achieved the guideline-recommended target of %BSA ≤ 1.0% at 3 months (90 days). In addition, 61% of patients (n = 561/915) achieved a %BSA of ≤1.0%, with a median time to target of 120 days. A %BSA of ≤0.5% was achieved by 50% (n = 455/915) of patients, with a median time to target of 199 days (95% CI = 172-228).80 For PASI treatment targets: 75% (n = 686/915) achieved an absolute PASI score of 3 or lower, with a median time to target of 58 days (95% CI = 57-63); 67% (n = 612/915) achieved a PASI of 2 or lower, with median time to target of 87 days (95% CI = 85-110); and 50% (n = 460/915) achieved a PASI of 1 or lower, with median time to target of 185 days (95% CI = 169-218).80

Safety and Tolerability of Tapinarof Cream for Psoriasis

Tapinarof cream 1% once daily was well tolerated with long-term use of up to 52 weeks as evaluated by patients and investigators, including when applied to sensitive and intertriginous skin areas.76 The safety profile of tapinarof cream in the PSOARING trials was consistent with previous trials, with no clinically relevant differences in laboratory values, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and physical examinations compared with vehicle-treated patients.42,76 There were no serious adverse events related to tapinarof cream in the PSOARING trials.42 Most treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the PSOARING trials were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.42 The most common TEAEs (in at least 1% of patients) in PSOARING 1 and 2 were folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, pruritus, and viral upper respiratory tract infection.42 Folliculitis was reported in 23.5% of the patients receiving tapinarof in PSOARING 1 and in 17.8% in PSOARING 2. Contact dermatitis was reported in 5.0% of the patients receiving tapinarof in PSOARING 1 and in 5.8% in PSOARING 2. Across the trials, folliculitis led to trial discontinuation in 1.8% of the patients receiving tapinarof in PSOARING 1 and in 0.9% of those in PSOARING 2. Contact dermatitis led to trial discontinuation in 1.5% and 2.0% of the patients receiving tapinarof in PSOARING 1 and 2, respectively. Headache was reported in 3.8% of the patients receiving tapinarof in PSOARING 1 and in 3.8% in PSOARING 2.

The most frequent TEAEs in PSOARING 3 were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, and upper respiratory tract infections.76 Adverse events of special interest (AESIs), specified prior to the trials, were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, and headache.42,76 Trial discontinuation rates due to AESIs were low in PSOARING 1 and 2 (≤1.8%, ≤2.0%, and ≤0.6%) and PSOARING 3 (1.2%, 1.4%, and 0%) for folliculitis, contact dermatitis, and headache, respectively.43,79 AESIs were generally mild or moderate in severity.

In PSOARING 3, investigator- and patient-reported tolerability scores were favorable in 86%-92% of patients over 40 weeks.76 Favorable tolerability was also reported when tapinarof cream was applied on sensitive and intertriginous skin, such as the face, gluteal cleft, genitals, inframammary areas, and axillae.76 Patients’ rates of adherence to tapinarof were high, at approximately 90% over 40 weeks.76

Patient-Reported Outcomes With Tapinarof Cream

In PSOARING 1 and 2, treatment with tapinarof cream 1% once daily was associated with improvements in patient-reported outcomes measured using the Peak Pruritus-Numerical Rating Scale (PP-NRS), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Psoriasis Symptom Diary.42,81

The proportion of patients who achieved at least a 4-point reduction in itch (considered clinically meaningful) on the PP-NRS at Week 12 was higher with tapinarof cream than with vehicle in PSOARING 1 (67.5% vs 46.1%, P = 0.0004) and PSOARING 2 (59.7% vs 31.3%, P < 0.0001).81 A greater mean improvement in PP-NRS at Week 12 was achieved with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and 2 (−3.9 vs −2.9, P = 0.0002 and −3.0 vs −1.4, P < 0.0001, respectively).81 Statistical significance for PP-NRS improvement was demonstrated as early as Week 2, the earliest time point measured, with continued improvement through the trials for tapinarof compared with vehicle.81

A greater mean improvement in the DLQI at Week 12 was achieved with tapinarof cream compared with vehicle in PSOARING 1 (−5.0 vs −3.0, P < 0.0001) and PSOARING 2 (−4.7 vs −1.6, P < 0.0001).81 Patients treated with tapinarof cream reported statistically significant improvements in HRQoL as early as Week 4, the earliest DLQI measurement.81 Significantly greater mean improvements in Psoriasis Symptom Diary scores at Week 12 were also achieved with tapinarof vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and 2 (−51.9 vs −34.6, P < 0.0001 and −43.5 vs −17.1, P < 0.0001, respectively).81 Statistical significance in HRQoL improvements with tapinarof vs vehicle was demonstrated as early as Week 2, the earliest time point measured, and maintained through all time points in both trials.81

In PSOARING 3, treatment with tapinarof cream demonstrated continued improvement in patients’ HRQoL, as measured by the DLQI.72 By Week 40, 68.0% of patients had a DLQI score of 0 or 1, indicating little or no impact of psoriasis on HRQoL. Furthermore, Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire responses assessed at Week 40 demonstrated a consistent and highly positive perception of tapinarof cream across all measures.72 Most patients strongly agreed or agreed with all patient satisfaction questions assessing confidence in tapinarof and satisfaction with efficacy (62.9%-85.8%) and cosmetic elegance (79.9%-96.3%; defined as being easy to apply, not greasy, quickly absorbed, and feeling good on the skin), and 81% and 68% preferred tapinarof to other topical and systemic drugs, respectively.72

Conclusions

Plaque psoriasis is a debilitating, chronic, inflammatory skin disease with significant morbidity and impact on patients’ health, functioning, and HRQoL, leading to a major economic burden for patients and health care systems. Current therapeutic options (topicals, and systemic oral and biologic therapies) have limitations, including limited efficacy, loss of efficacy over time, safety, and poor tolerability.12 Topical therapies, such as topical corticosteroids, also have restrictions relating to sites of application, duration, and the extent of body surface area that can be treated. Tapinarof cream 1% is the first highly efficacious, steroid-free topical option with no restrictions on application sites, or duration and extent of use,9 and a durable effect while on treatment (ie, no tachyphylaxis/decreased effect over time), a median remittive effect of 4 months off therapy (duration during which psoriasis does not recur off therapy), and no rebound after cessation of therapy.76 Consequently, once-daily tapinarof cream has the profile to address many gaps in current treatment options and represents an important therapeutic advancement. The magnitude and duration of efficacy with tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete clearance, the remittive period, and attainment of challenging treat-to-target goals, has the potential to reduce reliance on biologic and other systemic therapies. Delaying or avoiding progression to use of oral and biologic agents has important benefits for patients and cost implications relevant to managed care organizations.82,83 Tapinarof cream provides patients and physicians with an efficacious, well-tolerated, and convenient daily therapy, with a unique mechanism of action that addresses gaps in the current management of psoriasis. Validation of AhR as a therapeutic target in psoriasis supports the ongoing investigation of tapinarof for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and the potential of targeting AhR in other inflammatory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge ApotheCom, UK for editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1298-304).

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: A review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945-60. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301-15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon H-S, Mizara A, McBride SR. Psoriasis and psycho-dermatology. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2013;3(2):117-30. doi:10.1007/s13555-013-0031-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: Unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(9):504-13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22(2):196-203. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1557201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans C. Managed care aspects of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8)(suppl):s238-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):432-70. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapinarof (VTAMA®) cream. Prescribing information. Revised: June 2022. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- 10.Cannavò SP, Riso G, Casciaro M, Di Salvo E, Gangemi S. Oxidative stress involvement in psoriasis: A systematic review. Free Radic Res. 2019;53(8):829-40. doi:10.1080/10715762.2019.1648800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosca M, Hong J, Hadeler E, Hakimi M, Liao W, Bhutani T. The role of IL-17 cytokines in psoriasis. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2021;10:409-418. doi:10.2147/ITT.S240891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, Tallman AM, Armstrong A. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: A review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):1059-67. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim BE, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. TNF-α downregulates filaggrin and loricrin through c-Jun N-terminal kinase: Role for TNF-α antagonists to improve skin barrier. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(6):1272-9. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin X, Huang T. Oxidative stress in psoriasis and potential therapeutic use of antioxidants. Free Radic Res. 2016;50(6):585-95. doi:10.3109/10715762.2016.1162301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983-94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquali L, Srivastava A, Meisgen F, et al. The keratinocyte transcriptome in psoriasis: pathways related to immune responses, cell cycle and keratinization. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(2):196-205. doi:10.2340/00015555-3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furue M, Tsuji G, Mitoma C, et al. Gene regulation of filaggrin and other skin barrier proteins via aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80(2):83-8. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinde R, McGaha TL. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: connecting immunity to the microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2018;39(12):1005-20. doi:10.1016/j.it.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furue M, Hashimoto-Hachiya A, Tsuji G. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5424. doi:10.3390/ijms20215424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HO, Kim JH, Chung BY, Choi MG, Park CW. Increased expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23(4):278-81. doi:10.1111/exd.12350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beránek M, Fiala Z, Kremláček J, et al. Serum levels of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1 in patients with exacerbated psoriasis vulgaris. Folia Biol (Praha). 2018;64(3):97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burshtein J, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence of psoriasis among adults in the United States: A sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):1023-9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Bhutani T, Liao W, Nakamura M, eds. Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Updates in Clinical Dermatology. Springer; 2018:1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. ; American Academy of Dermatology Work Group . Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):137-74. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA. The Voice of the Patient - Psoriasis. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/101758/download

- 26.Møller AH, Erntoft S, Vinding GR, Jemec GB. A systematic literature review to compare quality of life in psoriasis with other chronic diseases using EQ-5D-derived utility values. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:167-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, Roberts J. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41(5):514-21. doi:10.1111/ced.12841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: A cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984-91. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, Bebo B. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: Findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003-2011. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52935. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: A systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(6):651-8. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Sawah S, Foster SA, Goldblum OM, et al. Healthcare costs in psoriasis and psoriasis sub-groups over time following psoriasis diagnosis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(9):982-90. doi:10.1080/13696998.2017.1345749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villacorta R, Teeple A, Lee S, Fakharzadeh S, Lucas J, McElligott S. A multinational assessment of work-related productivity loss and indirect costs from a survey of patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(3):548-58. doi:10.1111/bjd.18798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu JJ, Suryavanshi M, Davidson D, Patel V, Jain A, Seigel L. Economic burden of comorbidities in patients with psoriasis in the USA. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(1):207-19. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00832-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1445-86. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029-72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):775-804. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorelick J, Shrom D, Sikand K, et al. Understanding treatment preferences in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in the USA: Results from a crosssectional patient survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):785-97. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00334-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta S, Garbarini S, Nazareth T, Khilfeh I, Costantino H, Kaplan D. Characterizing outcomes and unmet needs among patients in the United States with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis using prescription topicals. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(6):2057-75. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00620-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong A, Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, et al. Treatment goals for psoriasis as measured by patient benefit index: Results of a National Psoriasis Foundation Survey. Adv Ther. 2022;39(6):2657-67. doi:10.1007/s12325-022-02124-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feldman SR. Treatment of psoriasis in adults. 2022. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-psoriasis-in-adults

- 41.Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(1):5-18. doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):2219-29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dopytalska K, Sobolewski P, Błaszczak A, Szymańska E, Walecka I. Psoriasis in special localizations. Reumatologia. 2018;56(6):392-8. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia NM, Cohen NA, Rubin DT. Treat-to-target and sequencing therapies in Crohn’s disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10(10):1121-8. doi:10.1002/ueg2.12336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin S, Zhao J, Li M, Zeng X. New insights into the pathogenesis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2022;8(4):256-63. doi:10.1002/cdt3.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramanan AV, Sage AM. Treat to target (drug-free) inactive disease in JIA: To what extent is this possible? J Clin Med. 2022;11(19):5674. doi:10.3390/jcm11195674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: Treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):290-8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 2):1-70. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: A review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(12):1209-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong A, Jarvis S, Boehncke WH, et al. Patient perceptions of clear/almost clear skin in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: Results of the Clear About Psoriasis worldwide survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(12):2200-7. doi:10.1111/jdv.15065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhutani T, Liao W. A. practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7(2):31-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. ; American Academy of Dermatology . Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):643-59. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres T, Puig L, Vender R, et al. Drug survival of IL-12/23, IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis treatment: A retrospective multi-country, multicentric cohort study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):567-79. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00598-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drakos A, Vender R. A review of the clinical trial landscape in psoriasis: An update for clinicians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(12):2715-30. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00840-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kleyn EC, Morsman E, Griffin L, et al. Review of international psoriasis guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis: Recommendations for topical corticosteroid treatments. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(4):311-9. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1620502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eicher L, Knop M, Aszodi N, Senner S, French LE, Wollenberg A. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease - Strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):2253-63. doi:10.1111/jdv.15913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murage MJ, Tongbram V, Feldman SR, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: A systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1483-503. doi:10.2147/PPA.S167508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaplan DL, Ung BL, Pelletier C, Udeze C, Khilfeh I, Tian M. Switch rates and total cost of care associated with apremilast and biologic therapies in biologic-naive patients with plaque psoriasis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:369-77. doi:10.2147/CEOR.S251775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: Findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003-2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1180-5. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armstrong AW, Foster SA, Comer BS, et al. Real-world health outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the United States: A population study using electronic health records to examine patient-perceived treatment effectiveness, medication use, and healthcare resource utilization. BMC Dermatol. 2018;18(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12895-018-0072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Belinchón I, Rivera R, Blanch C, Comellas M, Lizán L. Adherence, satisfaction and preferences for treatment in patients with psoriasis in the European Union: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2357-67. doi:10.2147/PPA.S117006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: Improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35(suppl 2):S36-44. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2016.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Papp KA, Dhadwal G, Gooderham M, et al. Emerging paradigm shift toward proactive topical treatment of psoriasis: A narrative review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6):e15104. doi:10.1111/dth.15104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):4974. doi:10.3390/jcm11174974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. Corticosteroid adverse effects. In: StatPearls. [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ference JD, Last AR. Choosing topical corticosteroids. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(2):135-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hintong S, Phinyo P, Chuamanochan M, Phimphilai M, Manosroi W. Novel predictive model for adrenal insufficiency in dermatological patients with topical corticosteroids use: A cross-sectional study. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:8141-7. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S342841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reid C, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis and treatment: Past, present and future aspects. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(3):adv00032. doi:10.2340/00015555-3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.US FDA. ZORYVE™ (roflumilast) cream, for topical use. 2022. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215985s000lbl.pdf.

- 70.Hoy SM. Deucravacitinib: First approval. Drugs. 2022;82(17):1671-9. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01796-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161-201. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bagel J, Stein Gold L, Del Rosso J, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: Patient-reported outcomes from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;S0190-9622(23):00771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: Results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(s3)(suppl 3): 2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eastman WJ, Malahias S, Delconte J, DiBenedetti D. Assessing attributes of topical vehicles for the treatment of acne, atopic dermatitis, and plaque psoriasis. Cutis. 2014;94(1):46-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural AhR agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(10):2110-9. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: Results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(4): 800-6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mooney N, Teague J, Gehad A, McHalen K, Rubenstein D, Clark R. Tapinarof inhibits the formation, cytokine production, and persistence of resident memory T cells in vitro. Poster presented at: Winter Clinical Dermatology Conference; January 13-18, 2023; Kohala Coast, HI. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jett JE, McLaughlin M, Lee MS, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% for extensive plaque psoriasis: A maximal use trial on safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(1):83-91. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00641-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lebwohl M, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: Efficacy and safety in two pivotal phase 3 trials. Oral presentation presented at: European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; September 23-27, 2020; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Armstrong AW, Bissonnette R, Brown PM, Tallman AM, Papp KA. Treat-to-target outcomes and measures of treatment success in three phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream 1% once daily for mild to severe plaque psoriasis. Poster presented at: European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; September 7-11, 2022; Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bissonnette R, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for plaque psoriasis: Patient-reported outcomes from two pivotal phase 3 trials. Poster presented at: American Academy of Dermatology; April 23-25, 2021; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu JJ, Lu M, Veverka KA, et al. The journey for US psoriasis patients prescribed a topical: A retrospective database evaluation of patient progression to oral and/or biologic treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(5):446-53. doi:10.1080/09546634.2018.1529386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kircik L, Joseph G, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, et al. 25406 Comparison of biologic initiation and health care costs among patients with psoriasis receiving fixed-dose combination halobetasol-propionate 0.01%/tazarotene 0.045%(HP/TAZ) lotion vs calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064%(CAL/BD) foam. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(3):AB57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.253 [Google Scholar]