Abstract

Background and Objectives

Clonic seizures are currently defined as repetitive and rhythmic myoclonic contractions of a specific body part, producing twitching movements at a frequency of 0.2–5 Hz. There are few studies in the literature that have reported a detailed analysis of the semiology, neurophysiology, and lateralizing value of clonic seizures. In this article, we aim to report our findings from a retrospective review of 39 patients.

Methods

We identified 39 patients (48 seizures) from our center who had been admitted with clonic seizures between 2016 and 2022. We performed a retrospective review of their video-EEG recordings for semiology and ictal EEG findings. Seventeen patients also had simultaneous surface-EMG (sEMG) electrodes placed on affected body parts, which were analyzed as well.

Results

The most common initial affected body parts were face, arm, and hand. In most of the cases, seizures propagated from lower face to upper face and distal hand to proximal arm. The most common seizure-onset zone was the perirolandic region, and the most common EEG seizure pattern was paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity. The lateralizing value for EEG seizure onset to contralateral hemisphere in unilateral clonic seizures (n = 39) was 100%. All seizures recorded with sEMG electrodes demonstrated synchronous brief tetanic contractions of agonists and antagonists, alternating with synchronous silent periods. Arrhythmic clonic seizures were associated with periodic epileptiform discharges on the EEG, whereas rhythmic clonic seizures were associated with paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity. Overall, the most common etiology was cerebrovascular injuries, followed by tumors.

Discussion

Clonic seizures are characterized by synchronized brief tetanic contractions of agonist and antagonistic muscles alternating with synchronized silent periods, giving rise to the visible twitching. The most common seizure onset zone is in the perirolandic region, which is consistent with the symptomatogenic zone being in the primary motor area. The lateralizing value of unilateral clonic seizures for seizure onset in the contralateral hemisphere is 100%.

Introduction

Clonic seizures are currently defined as repetitive and rhythmic myoclonic contractions of a specific body part, producing twitching movements at a frequency of 0.2–5 Hz.1 The twitching produced by myoclonic and clonic seizures appears the same. The clonus is simply considered as a regular and repetitive form of myoclonus.1

Louis François Bravais was the first to describe focal clonic seizures in 1827. He described l épilepsie hémiplégique as a convulsion affecting only one side of the body in his thesis for his MD at University of Paris.2 In 1870, Sir John Hughlings Jackson delivered his landmark lecture “A study of convulsions” at University of St. Andrews where he described unilateral motor seizures as “….the fit begins with deliberate spasm of one side of the body, and in which parts of the body are affected, one after another.”3 This was later referred to as Jacksonian epilepsy by Charcot in 1877.4

Although there have been studies in the literature that have partially analyzed the lateralizing value of focal clonic seizures, there have not been any studies analyzing the clinical semiology and neurophysiology of clonic seizures in a systematic manner.5-8 In this article, we aim to report a detailed analysis of clinical semiology, propagation patterns, seizure-onset zone, lateralizing value, and surface EMG (sEMG) characteristics of clonic seizures.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the video-EEG records of patients between 2016 and 2022 who were admitted to University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center with a clinical diagnosis of clonic seizures (unilateral or bilateral). We included all patients above the age of 1 month with clear video recording of the clonic activity with corresponding EEG files available for independent review. Any cases where the body part affected by the clonic seizure was partly or completely hidden away from the video were excluded. We excluded patients with generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) seizures. We also excluded cases with missing EEG files.

With these criteria, we identified 39 patients (n1) with 48 seizures (n2). More than 1 seizure per patient were included only if the initially affected body part or the propagation pattern of the clonic seizure was different than the first one. 17 of these patients were male and 22 were female. The age of patients ranged between 12 months and 86 years (mean 48.8 years). This group included patients with chronic epilepsy and acute symptomatic seizures.

In all the cases, video-EEG was recorded using the Neurofax EEG-1200 system by Nihon Kohden (Tokyo, Japan). The EEG electrodes were placed according to the standard 10–20 International system. In 17 patients (17 seizures), the body part affected by the clonic activity was also monitored using sEMG electrodes. These electrodes were placed according to a standardized sEMG montage developed for each body part at our institution (eAppendix 1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A505). The affected body part (e.g., arm) was monitored using 2 electrodes covering the flexor muscles and 2 electrodes covering the extensor muscles. The lead investigator (NF) analyzed all the video-EEG records and performed sEMG analyses as well.

Seizure Semiology: EEG and Video Analysis

We analyzed the following characteristics:

Initial body part involved in the clonic seizure

Propagation pattern

Preceding and following seizure semiology

Seizure-onset zone, EEG seizure pattern, and lateralizing value

Neurophysiology With sEMG Analysis

We analyzed the following characteristics:

Rhythmicity of the EMG bursts

Duration of flexor and extensor EMG bursts

EEG to sEMG latency

Pattern of activation of flexor and extensor muscle groups–synchronized v alternating

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and informed consent was waived off.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Seizure Semiology: EEG and Video Analysis

Seizure-Onset Zone, EEG Seizure Pattern, and Lateralizing Value

Figure 1A shows the distribution of different seizure-onset zones in our study. Overall, the perirolandic region (parietocentral, frontocentral, and central) was the most common seizure-onset zone (46%).

Figure 1. Seizure-Onset Zone and Lateralizing Value.

(A) Graph showing various seizure-onset zones; (B) Pie chart showing distribution of unilateral and bilateral clonic seizures.

Thirty-nine of 48 seizures were unilateral (focal) clonic. The seizure-onset zone was contralateral in all these seizures (100%). All bilateral clonic seizures had a generalized seizure onset (Figure 1B).

We identified 2 main seizure patterns—paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity and periodic epileptiform discharges. Overall, the most common EEG seizure pattern was paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic theta-delta activity (56%), followed by periodic epileptiform discharges (31.7%). The remaining cases were characterized by spike-wave pattern (12.3%), and these were generalized in onset.

For all focal-onset seizures, the proportion of seizures characterized by periodic epileptiform discharges was higher in the perirolandic group when compared with other focal-onset seizures (43% vs 17%). The most common EEG seizure pattern in generalized-onset seizures was a spike-wave pattern (62.5%).

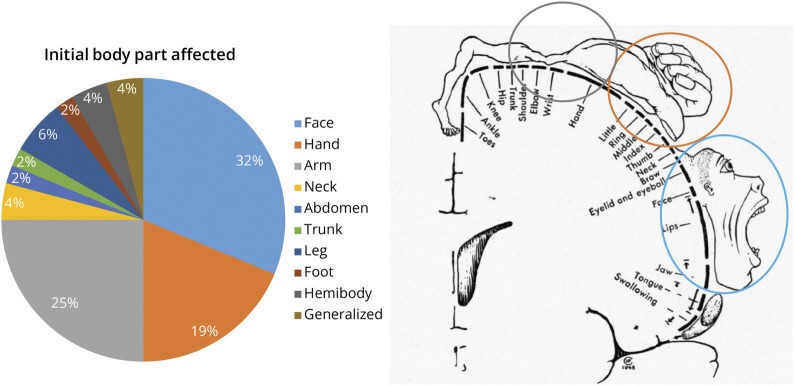

Initial Body Part Involved in the Clonic Seizure

Of 48 seizures, the face was the initial body part affected in 15 (approximately 32%), followed by the arm in 12 (approximately 25%), and the hand in 9 (approximately 19%). Other body parts were much less commonly affected (Figure 2). Overall, the upper extremity (arm + hand) was the most common initial body part affected (approximately 44%). These findings are consistent with the large representation of the face and the upper extremity in the motor homunculus. The frequency of clonic twitching ranged between 0.5 and 4 Hz.

Figure 2. Pie Chart Distribution and Penfield Motor Homunculus* Representation of the Most Commonly Affected Initial Body Part in Clonic Seizures.

*Adapted from Ref. 24 with permission from the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University.

Propagation Patterns

Because most of the seizures in our study either started in the upper extremity or the face (approximately 75%), we analyzed the following propagation patterns:

Face propagation

Upper extremity propagation

Face-upper extremity propagation

Overall, the face was involved in 21 seizures. The most common pattern was lower face clonic activity propagating to upper face (33%) (Figure 3A). The upper extremity was involved in a total of 32 seizures. In 22 of 32 seizures (approximately 69%), the predominant muscle groups involved were distal (hand and forearm). In 10 of 32 seizures (approximately 31%), the predominant muscle groups involved were proximal (shoulder and arm). In 16 seizures, clear propagation of clonic activity in the upper extremity was seen. The most common pattern was distal to proximal (hand to shoulder) propagation (62.5%) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Penfield Motor Homunculus*, Somato-Cognitive Motor Homunculus** and Graphical Representation of (A) Face Clonic Seizure Propagation Patterns; (B) Upper Extremity Propagation Patterns; (C) Face-Upper Extremity Propagation Patterns.

*Adapted from Ref. 24 with permission from the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University; **Adapted from Ref. 19, Open Access Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In seizures with both face and upper extremity involvement (n = 12), we observed propagation from face to arm in 50% of seizures and arm to face in the other 50%. Of interest, we never observed direct propagation from hand into face. Seizures starting in the hand always involved the arm first before propagating anywhere else (Figure 3C).

Preceding and Following Seizure Types

In 30 of 48 seizures, there was no reported or observed semiology preceding the clonic activity. In the remaining 18 seizures, the most common preceding semiology was tonic seizure. In 40 of 48 seizures, there was no other seizure semiology observed after the clonic activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Seizure Semiologies Preceding and Following Clonic Seizures.

Etiology

The etiologies are summarized in the Table. Cerebrovascular causes formed the most common group in our study, followed by brain tumors.

Table.

Various Etiologies of Clonic Seizures in This Study

| Etiology | No. of patients |

| Cerebrovascular | 13 |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 5 |

| Chronic intraparenchymal hemorrhage | 3 |

| Chronic infarct | 3 |

| Subarachnoid hematoma | 1 |

| Vascular malformations | 1 |

| Tumors | 10 |

| Metastatic | 4 |

| Glioblastoma | 2 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 1 |

| DNET | 1 |

| Meningioma | 1 |

| WHO Gr III solitary fibrous tumor | 1 |

| Genetic/malformations | 2 |

| Rhizomelic chondrodysplasia | 1 |

| STXBP1 encephalopathy | 1 |

| Neonatal HIE | 3 |

| Cortical dysplasia | 2 |

| FCD | 1 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 1 |

| Sequela of TBI | 1 |

| Demyelination | 1 |

| Encephalitis | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | 6 |

| Hyperammonemia | 1 |

| Dementia | 1 |

| SLE | 1 |

| Post-COVID | 1 |

| NAT | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

Abbreviations: DNET = dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor; FCD = focal cortical dysplasia; HIE = hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; NAT = nonaccidental trauma; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; TBI = traumatic brain injury; WHO = World Health organization.

Neurophysiology With sEMG Analysis

In this section, we will present the results of 17 seizures that were monitored using sEMG electrodes covering flexor and extensor muscles groups. In all seizures, the actual movements were produced by a synchronous brief tetanic contraction of flexor and extensor muscles, followed by a synchronous silent periods in both muscle groups as well. This pattern of brief tetanic contraction followed by relaxation was responsible for the twitching or jerking appearance of the clonic seizures. Based on the rhythmicity of the EMG bursts, we classified the clonic seizures into arrhythmic and rhythmic.

Arrhythmic Clonic Seizures (n = 7)

The EMG bursts in both flexors and extensors were synchronous with no evolution in amplitude and duration. The mean duration of EMG bursts in flexor and extensor muscle groups was 154.5 and 147.5 msec, respectively. The mean latency from the onset of EEG discharge to the onset of EMG burst was 55.5 msec. The mean latency from the peak of EEG discharge to the onset of EMG burst was 11.3 msec. The most common EEG seizure pattern associated with arrhythmic clonic seizures was periodic epileptiform discharges (75%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Arrhythmic Clonic Seizure.

(A) 10-second EEG page with sEMG channels showing synchronized EMG bursts of right forearm flexors and extensors (black arrows) time locked to left frontocentral LPDs (red arrows); (B) 5-second page with left frontocentral LPDs, maximum at C3 and F3, time locked to EMG bursts with a latency of approximately 26 ms. FE = forearm extensor; FF = forearm flexor; LPD = lateralized periodic discharges.

Rhythmic Clonic Seizures (n = 10)

The EMG bursts in flexors and extensors were synchronous as well just like the arrhythmic clonic seizures with clear evolution in amplitude and duration from the first half of the seizure to the second half (Figure 6). The average duration of EMG bursts in flexor and extensor muscles increased from 188.5 to 320.6 msec and 186.4 to 321.8 msec, respectively, from the first half of the seizure to the second half.

Figure 6. Rhythmic Clonic Seizure.

(A) 10-second EEG page with sEMG channels showing synchronized EMG bursts of right forearm flexors and extensors (black arrows), associated with paroxysmal delta seen in the left hemisphere (red arrows); (B) evolution of the seizure with widened EMG bursts (black arrows); (C) end of the seizure; (D) 5-second page with left hemispheric paroxysmal delta, time locked to EMG bursts with a latency of approximately 20 ms. FE = forearm extensor; FF = forearm flexor.

Similar to the duration, the average EMG burst amplitude in flexor and extensor muscles increased by approximately 150% and 130%, respectively. The most common EEG seizure pattern associated with rhythmic clonic seizures was paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity (86%) (Figure 6).

Discussion

After the initial descriptions by Sir John Hughlings Jackson, the first detailed clinical series of clonic seizures was reported by Penfield and Kristiansen4 in their monograph Epileptic Seizure Patterns. They referred to these seizures as Jacksonian motor seizures. Penfield and Jasper defined Jacksonian seizures as being characterized by the movement of a body part, which could spread from one part to another as the seizure discharge would spread up or down the precentral gyrus (so-called Jacksonian march).9

Since then, there have been few articles that have studied the localizing and lateralizing value of clonic seizures but not in detail and none with simultaneous EEG and sEMG recordings.5-8,10-13 In this study, we aimed to characterize the clinical semiology, seizure-onset zone, lateralizing value, and neurophysiology of clonic seizures.

Clonic seizures are defined by twitching or jerking movements of a body part. These movements are produced by brief tetanic synchronized contractions of both flexor and extensor muscles, followed by synchronized silent periods, not by alternating contraction and relaxation of agonist and antagonistic muscles, as was thought by Sir Gordon Holmes.14

The face and the upper extremity (arm + hand) are the most commonly affected initial body parts. Because the symptomatogenic zone of the clonic seizures is considered to be the primary motor cortex in the precentral gyrus, this finding is consistent with the large representations of upper extremity and face in the motor homunculus.15-18

The clonic movement most commonly affects the distal muscle groups in the upper extremity (hand), and the seizure usually propagates from hand to arm and shoulder (Figure 3B). In the face, the most common pattern is lower face to upper face propagation, before spreading into the upper extremity (Figure 3A).

Our findings are consistent with the known organization of the Penfield motor homunculus.9 However, the propagation of seizure activity is not simply due to cortical contiguity. It is, perhaps, also dependent on functional connectivity of cortical areas. This explains why seizures starting in the hand do not propagate directly into face before propagating into the arm first, though the face is immediately adjacent to the hand area (Figure 3C). A recent update to the classic motor homunculus proposes 3 concentric effector regions (face, hand, and foot), which better explains why a seizure starting in the hand propagates into the arm first, rather than propagating into the face.19

In cases where the clonic activity is preceded by a different semiology, the tonic seizure is the most common. Our recent study has shown that both tonic and clonic movements can be elicited from the primary motor area by electrical stimulation, depending on the intensity and frequency of stimulation. We have also demonstrated that a tonic contraction produced at high frequency, high-intensity stimulation reverts into clonic contraction toward the end of the stimulation train.18 Perhaps the evolution of tonic seizures into clonic seizures is analogous to our stimulation results.

The most common seizure-onset zone for focal clonic seizures is the perirolandic region. This is consistent with the observation that the most likely symptomatogenic zone of clonic seizures is the primary motor area in the precentral gyrus.1,9,17,18 Hence, it is not surprising that the seizure-onset zone is close to the known symptomatogenic zone.

In our study, the lateralizing value of focal clonic seizures to the contralateral hemisphere is 100%. As far as we are aware, this is the largest study of clonic seizures with simultaneous video-EEG analysis. Previously, Gallmetzer et al. performed a systematic analysis of postictal paresis in 44 patients with 72 seizures.7 Of them, 29 patients with 40 seizures had focal clonic activity preceding the postictal paresis. Overall, the EEG seizure onset was unequivocally lateralized to 1 hemisphere in 35 patients. In all these patients, the postictal paresis and unilateral clonic activity were present on the same side of the body and contralateral to seizure-onset zone.7 There have been other studies in the literature that have analyzed the lateralizing value of clonic seizures with smaller number of patients and seizures. Overall, this value varies from 81.3% to 100%.5-8,10-13

The 2 most common EEG seizure patterns associated with clonic seizures are paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity and periodic epileptiform discharges. The former is more likely to be associated with rhythmic clonic seizures, whereas the latter is more likely to be associated with arrhythmic clonic seizures. The most common localization is the perirolandic region. The pattern of periodic epileptiform discharges is more common in the perirolandic group as opposed to other focal-onset seizures (43% v 17%). The most common pattern in generalized-onset seizures is a spike-wave pattern. The frequency of clonic seizures varies between 0.2 Hz and 5 Hz, which is consistent with the frequency of the EEG seizure pattern.1

Sir Gordon Holmes14 had proposed in his Sabill Memorial Oration in 1927 that the clonic movement is produced by activation of agonistic muscle groups with simultaneous relaxation of antagonistic muscle groups. However, in a study of spontaneous clonic seizures, Hamer et al. demonstrated with sEMG electrodes that clonic contractions are produced by synchronized activation of agonistic and antagonistic muscles, followed by their synchronized relaxation. Although of their 11 patients, only 2 had sEMG coverage of both agonists and antagonists.16 Cortical electrical stimulation studies performed with simultaneous sEMG electrodes also show that clonic movements induced by stimulation of the primary motor area are characterized by brief tetanic synchronized contractions of both flexor and extensor muscle groups, alternating with synchronized silent periods as well.17,18

Our group has recently published a study on sEMG characteristics of clonic movements induced by electrical stimulation of primary motor area using subdural grid electrodes. The study showed that clonic movements can be elicited at both low-frequency (<20 Hz) and high-frequency (≥20 Hz) stimulations, referred to as type I clonic and type II clonic, respectively.18 In all cases, the sEMG bursts and silent periods of flexors and extensors (agonists and antagonists) are synchronous. No other pattern is seen.

As far as we are aware, our sample of 17 patients (17 seizures) is the largest case series of clonic seizures with sEMG recordings of both agonistic and antagonistic muscles. The sEMG characteristics of spontaneous clonic seizures are very similar to clonic movements induced by cortical stimulation with synchronized contractions of agonists and antagonists, alternating with synchronized silent periods. In addition, the amplitudes and morphology of both flexor and extensor EMG bursts are very similar. The duration of these bursts varies from 140 msec to 200 msec. In rhythmic clonic seizures, the duration of these bursts increases to 300–325 msec toward the second half of the seizure. This prolonged duration of EMG bursts and silent periods accounts for the slowing of clonic frequency.17,18

Various patterns of muscle activation on sEMG have been used to identify GTC seizures and distinguish them from nonepileptic or simulated seizures.20,21 Most of these studies have used single-channel sEMG on deltoid muscle for visual and quantitative analyses. Baumgartner et al. published a study on the value of sEMG in identification of various motor semiologies.20 In their study, 20 patients had 47 motor seizures with significant upper extremity involvement. Of these, only 3 seizures had unilateral clonic activity. Both the automated classification technique and expert epileptologists could correctly classify only 1 of 3 of the clonic seizures.20 The sEMG was recorded using single channel covering the biceps muscle only. Another study that analyzed the clonic phase of the GTC seizures using a single-channel sEMG identified an average burst duration of 150.3 ms as opposed to 212.4 ms duration in simulated clonic movement.22

The brief tetanic muscle contractions are time locked to epileptic discharges while the silent periods are time locked to periods of attenuation or slow waves. The epileptic discharges based in the primary sensory-motor cortex (perirolandic) activate pyramidal tract neurons, which project to the spinal motor neurons through the corticospinal tract.17,18 This hypothesis is supported by cortical stimulation studies.

Low-frequency (<20 Hz) electrical stimulation of the primary motor area produces type I clonic responses, which are characterized by simple EMG bursts (≤50 msec duration) made up of single motor unit potentials, and the silent periods are simply because of lack of stimulation.18 The arrhythmic clonic seizures are analogous to type I clonic responses in the sense that the silent periods correspond to periods of relative EEG attenuation between the periodic epileptiform discharges. The mean duration of EMG bursts in arrhythmic clonic seizures is longer than type I clonic responses though. This is likely due to the complex nature of periodic epileptiform discharges when compared with simple biphasic pulses of electrical stimulation.

High-frequency (≥20 Hz) stimulation of the primary motor area produces type II clonic responses, characterized by complex EMG bursts (>50 msec duration) made up of multiple motor unit potentials. The silent periods occur despite continued stimulation. This is believed to be the result of temporal summation of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials producing the silent periods.18 A similar phenomenon likely produces the slow waves following the epileptic spikes. Rhythmic clonic seizures are analogous to type II clonic responses. Although on scalp EEG, we are often unable to see the epileptic spikes producing the actual contraction, studies with intracranial EEG have demonstrated the presence of polyspikes time locked to the tetanic contractions, alternating with slow waves time locked to the silent periods.16,23

The stimulation studies also indicate that this phenomenon is mediated by the corticospinal tract only because the latency of EMG bursts from the stimulation artifact for upper extremity muscles is approximately 20 ms, consistent with corticospinal conduction.18 The average latency of EMG bursts from the epileptiform discharges is also <20 ms as reported above.

In summary, clonic seizures are defined by brief synchronized tetanic contractions of agonistic and antagonistic muscles, alternating with synchronized silent periods at a frequency of 0.2–5 Hz. The lateralizing value of focal clonic seizures to the contralateral hemisphere is 100%. The most common seizure-onset zone is the perirolandic region, and the most common EEG seizure pattern is paroxysmal rhythmic monomorphic activity.

Clonic seizures have unique sEMG characteristics that are similar to the clonic responses obtained by electrical stimulation of the primary motor area. These sEMG characteristics can aid in the diagnosis and long-term monitoring of clonic seizures.20,21

Our study provides detailed 2-channel sEMG data covering agonists and antagonists in patients with unilateral or bilateral clonic seizures. The characteristics described here could aid in the diagnosis and quantification of such seizures in prolonged video-EEG monitoring, especially with poor or no EEG correlate. Quantitative analysis of sEMG data was not performed in this study and could be considered a limitation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the EEG technologists at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center for their utmost dedication and hard work.

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Neel Fotedar, MD | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Aybuke Acar, MD | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Suhailah Hakami, MD | Epilepsy Center, University of Melbourne | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Kulsatree Praditukrit, MD | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Alla Morris, REEGT, CLTM | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Mark dela Vega, REEGT | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Guadalupe Fernandez-BacaVaca, MD | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Hans O. Lüders, MD, PhD | Epilepsy Center, Neurological Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine | Study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Lüders HO. Textbook of Epilepsy Surgery. CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eadie M. Louis François Bravais and Jacksonian epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51(1):1-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JH. A study of convulsions. Arch Neurol. 1970;22(2):184-188. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480200090012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penfield W, Kristiansen K. Epileptic Seizure Patterns. Charles C. Thomas; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauguiere F, Courjon J. Somatosensory epilepsy. A review of 127 cases. Brain. 1978;101(2):307-332. doi: 10.1093/brain/101.2.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manford M, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. An analysis of clinical seizure patterns and their localizing value in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 1):17-40. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.1.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallmetzer P, Leutmezer F, Serles W, Assem-Hilger E, Spatt J, Baumgartner C. Postictal paresis in focal epilepsies—incidence, duration, and causes: a video-EEG monitoring study. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2160-2164. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.12.2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janszky J, Fogarasi A, Jokeit H, Ebner A. Lateralizing value of unilateral motor and somatosensory manifestations in frontal lobe seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2001;43(2):125-133. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(00)00186-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain. Little Brown and Company; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonelli SB, Lurger S, Zimprich F, Stogmann E, Assem-Hilger E, Baumgartner C. Clinical seizure lateralization in frontal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48(3):517-523. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loddenkemper T, Wyllie E, Neme S, Kotagal P, Lüders HO. Lateralizing signs during seizures in infants. J Neurol. 2004;251(9):1075-1079. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0463-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marashly A, Ewida A, Agarwal R, Younes K, Lüders HO. Ictal motor sequences: lateralization and localization values. Epilepsia. 2016;57(3):369-375. doi: 10.1111/epi.13322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwan S, Alexopoulos A, Silveira DC, Kotagal P. Lateralizing and localizing value of seizure semiology: comparison with scalp EEG, MRI and PET in patients successfully treated with resective epilepsy surgery. Seizure. 2018;61:203-208. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes G. Sabill memorial oration on local epilepsy. Lancet. 1927;209(5410):957-962. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foerster O. The motor cortex in man in the light of Hughlings Jackson’s doctrines. Brain. 1936;59(2):135-159. doi: 10.1093/brain/59.2.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamer HM, Lüders HO, Knake S, Fritsch B, Oertel WH, Rosenow F. Electrophysiology of focal clonic seizures in humans: a study using subdural and depth electrodes. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 3):547-555. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamer HM, Lüders HO, Rosenow F, Najm I. Focal clonus elicited by electrical stimulation of the motor cortex in humans. Epilepsy Res. 2002;51(1-2):155-166. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00104-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fotedar N, Fernandez-BacaVaca G, Rose M, Miller JP, Lüders HO. Spectrum of motor responses elicited by electrical stimulation of primary motor cortex: a polygraphic study in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;142:109185. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon EM, Chauvin RJ, Van AN, et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature. 2023;617(7960):351-359. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05964-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumgartner C, Whitmire LE, Voyles SR, Cardenas DP. Using sEMG to identify seizure semiology of motor seizures. Seizure. 2021;86:52-59. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beniczky S, Conradsen I, Wolf P. Detection of convulsive seizures using surface electromyography. Epilepsia. 2018;59(suppl 1):23-29. doi: 10.1111/epi.14048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardenas D, Voyles S, Whitmire L, Cavazos J. Surface-electromyography (sEMG) Patterns of clonic bursts during generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) seizures (P4.5-010). Neurology. 2019;92(15 suppl):P4.5-010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acar A, Ticku H, Fotedar N. A simultaneous intracranial EEG-surface EMG analysis of generalized tonic-clonic seizures (P10-1.004). Neurology. 2023;100(17 suppl 2):1758. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000202102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penfield W, Rasmussen T. The Cerebral Cortex of Man: A Clinical Study of Localization of Function. The McMillan Company; 1950. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.