Abstract

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) has been a leader in neonatal research since 1986. In this chapter we review its history and achievements in (1) continuing observation of populations, treatments, short and longer-term outcomes, and trends over time; (2) “negative studies” (trials with non-significant primary outcomes) and trials stopped for futility or adverse events, which have influenced practice and subsequent trial design; and, (3) landmark trials that have changed neonatal care.

Its consistent framework has enabled the NRN to be a pioneer in conducting longer-term, school-age follow-up. Leveraging its established infrastructure, the NRN has also partnered with other NIH institutes, governmental agencies, and industry to more effectively advance neonatal care. As current examples of its evolution with changing times, the Network has instituted a process to open specific network trials to external institutions and is adding a parent and participant component to future endeavors.

History

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established the Neonatal Research Network (NRN) in 1986, following an open competition for inaugural study sites. NICHD recognized the need to conduct rigorous observational and interventional studies in sick and premature newborns to provide an evidence base to guide clinical practice. The first funding cycle included 7 centers; however, it soon became clear that larger populations were required. In 1991, 12 awards were made, and since then the number has varied between 15-18 academic centers (often with more than one participating hospital). A competitively awarded data coordinating center provides statistical and study design expertise, logistical support, and communications.

By assembling many clinical sites for study subject recruitment, data and results can be obtained more rapidly than through individual study site enrollment. Because centers are located throughout the United States, the NRN includes mothers and newborns with racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity, improving generalizability of Network research.

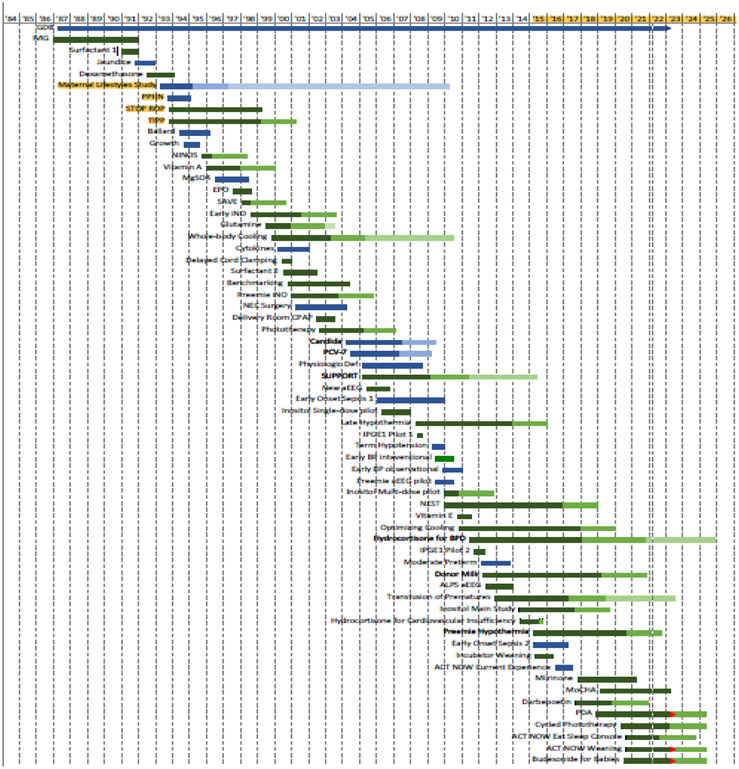

The NRN has been very productive, with 60 studies completed or in process, underscoring the value of cooperative multicenter clinical networks (Figure 1). In addition to conducting clinical trials, the NRN maintains registries (Generic Database and Follow up) that have allowed evaluation of morbidity and mortality trends over decades. Moreover, data for these registries is collected by trained research staff, using consistent data definitions, ensuring optimal efficiency by providing the personnel and infrastructure to rapidly launch and sustain trials. Using this structure, the NRN has conducted and continues to conduct trials and observational studies addressing a wide array of major neonatal problems. The NRN has been a model for team science over the years. In addition to principal investigators who provide expertise in the design and conduct of clinical research, co-investigators, follow up experts, junior faculty members, nurse coordinators, and trainees have actively participated and led studies. Moreover, the NRN has promoted intergovernmental collaboration with other NIH institutes, NIH-supported clinical trials groups, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The original NICHD vision of a network of centers linked together to perform cooperative clinical research for newborns continues to be vital. Over more than 35 years, the NRN has brought about numerous changes in care to improve outcomes for high risk infants.

Figure 1.

Neonatal Research Network Study Timeline

Observations over Time

Immediately after its inception, the NRN established a very low birthweight registry, the Generic Database (GDB), a registry of all extremely preterm infants born at its study centers. As detailed in Chapter 2, the stable infrastructure of the NRN over more than 35 years has provided a mechanism for detailed analysis of changing population characteristics, therapies, and outcomes over time, as well as the flexibility to perform time-limited data collections to answer specific questions. Periodic publications of the epidemiology of extremely preterm infants utilizing GDB data have documented changes over time from the first report1 to the most recent 2 and are among the most cited publications of the NRN.3 The GDB, with more than 91,000 infants included as of February 28, 2022, has provided data for posing and answering important questions in neonatology.

Recognizing the importance of evaluating the effect of population characteristics and therapies not only on immediate in-hospital mortality and morbidities but on longer-term neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes, the NRN established a Follow-up Study. The NRN centers have performed in-person evaluations between 18-26 months corrected age for extremely preterm infants in many randomized clinical trials (RCTs) since 1993. As outlined in Chapter 9, establishing stringent certification and continuing recertification processes for neurologic, motor, and cognitive examinations has resulted in consistent evaluation of neurodevelopmental outcomes and factors affecting extremely preterm infants over time.

Although evaluation at 2 years provides essential information, these data have limited predictive value for later outcomes. Appreciating the need for assessment of longer-term outcomes, the NRN has included 6-7 year assessments of children who were enrolled in its landmark RCT of induced hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE),4 a trial that began enrollment in 2000. Subsequently, a cohort of extremely preterm infants enrolled in the Surfactant Positive Airway Pressure and Pulse Oximetry Trial (SUPPORT) study5 was enrolled into a study to correlate neonatal cranial imaging with neurodevelopmental outcomes at 6-7 years.6 These assessments were subsequently expanded to include evaluation of adiposity, blood pressure, and adrenal function.7,8,9

Tracking families over time and funding outcome studies through early school-age is time-consuming and expensive. Despite this complexity, the NRN’s stable infrastructure has provided a foundation on which to create a more comprehensive understanding of outcomes after preterm birth and neonatal illness. The Network has now greatly expanded this effort, with collaborative funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), to assess functional as well as developmental outcomes of infants enrolled in its Hydrocortisone for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia and Transfusion of Prematures RCTs. Testing exercise tolerance and pulmonary function of these children will enable comparisons with a cohort of healthy, term-born infants, as described in Chapter 10.

Studies with Non-significant Primary Outcome or Those Stopped before Full Enrollment

Some of the major contributions the NRN has made have been through performing and reporting multicenter RCTs which either showed no significant difference in the primary outcome (a “negative study”) or were stopped early due to inability to enroll or discovery of an unexpected adverse outcome (Table 1). Excitement engendered by small positive RCTs or observational data has often led to adoption of therapies with a limited evidence base and/or safely profile. Rigorous testing in the large, heterogenous population of the NRN has led to discontinuation of several ineffective therapies, such as intravenous immunoglobulin to prevent nosocomial sepsis,10 phenobarbital to prevent intraventricular hemorrhage,11 glutamine in parenteral nutrition to prevent nosocomial sepsis,12 and inhaled nitric oxide in preterm infants.13 A review of inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) in preterm infants that included the NRN trial led to an NIH consensus conference recommendation to avoid routine use of iNO in preterm infants.14 The SUPPORT study showed no benefit to early intubation compared to initial management with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in extremely preterm infants, resulting in a decrease in immediate intubation in the delivery room.15

Table 1.

# Significantly improved in CPAP arm in meta-analysis20

| Trial, year of publication |

Statistically non-significant primary outcome |

Statistically significant planned primary or secondary outcomes or components of the primary outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Expected sample size reached | ||

| Surfactant, J Pediatrics 199317 | Death or BPD 28 days after birth | Lower average FiO2 and mean airway pressure during the 72 hours after the initial surfactant dose with Survanta than Exosurf (primary outcome) |

| IVIG, NEJM 1994 10 | Incidence of hospital-acquired infection | - |

| Phenobarbital, NEJM 199711 | Intracranial hemorrhage during neonatal period or death within 72 hours of birth | - |

| TIPP, NEJM 200131 | Composite of death, cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, deafness, and blindness at a corrected age of 18 months | Decreased incidence of patent ductus arteriosus, severe periventricular and intraventricular hemorrhage with indomethacin |

| SAVE, NEJM 200121 | Death or chronic lung disease at 36 weeks postmenstrual age | Increased SIP and decreased growth in dexamethasone arm |

| Glutamine, Pediatrics 200412 | Death or late-onset sepsis | - |

| Preemie iNO, NEJM 2005 13,14,32 | Death or BPD | In subgroup analysis, for infants with ruptured membranes, oligohydramnios and suspected pulmonary hypoplasia, iNO improved oxygenation and may decrease the rate of BPD and death |

| Benchmarking, Pediatrics 200733 | Survival without BPD among <1250 g infants | - |

| Phototherapy, NEJM 200818 | Death or neurodevelopmental impairment | - |

| SUPPORT -saturation trial, NEJM 20105,30 | Death or severe ROP | Lower risk of ROP but higher risk of death in lower saturation arm |

| SUPPORT - CPAP trial, NEJM 2010 15,34 | Death or BPD# | - |

| Incubator weaning, J of Pediatrics 2019 25 | Length of hospital stay | Weight gain improved in earlier weaning arm |

| TOP, NEJM 202026 | Death or neuro-developmental impairment (cognitive delay) | Fewer transfusions in the lower threshold arm |

| NEST (laparotomy vs. drain for NEC or SIP) 202119 | Death or neurodevelopmental impairment at age 2 | For NEC, 69% after laparotomy vs 81% after drain; for SIP, 69% vs 63% |

| Hydrocortisone for BPD NEJM 202227 | Efficacy: death/BPD at 36 weeks Safety: death/NDI at 2 years | Fewer days of intubation/mechanical ventilation for HC-treated arm |

| Stopped early | ||

| Early BP feasibility trial, J Pediatrics 201335 | Enrollment of 60 infants in 1 year, with a protocol deviation rate <20% | 10 infants enrolled, stopped for futility |

| Inhaled PGE1 feasibility trials , Trials 201436 | Enrollment of 50 infants in six to nine months at 10 sites | No infants enrolled in first pilot, 7 enrolled in second pilot, stopped for futility |

| Optimizing cooling, JAMA 2014, 2017 22,37, Trials 201638 | Death or disability at 18-22 months | Interaction between depth and duration of cooling on primary outcome |

| Hydrocortisone in hypotensive term infants, J Perinatol 201739 | Death or neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) at 22-26 months | 12 infants enrolled, stopped for futility |

| Inositol, NEJM 201840 | Death or type 1 ROP | Increased mortality in inositol arm |

Strand and Jobe suggested that lack of significance in multicenter trials in neonatal-perinatal medicine may result from several factors: (1) trial design, (2) incorrect biological basis for the intervention, (3) misleading preliminary data in small prior trials, (4) confounded or unattainable primary outcome, (5) obscuring of potential benefit by variability between centers, and (6) treatment effect not large enough to measure.16 Several additional factors may also contribute. First, some interventions had different effects on two primary outcomes17 or competing components of a compound primary outcome.5,18 Second, the intervention may have different effects on different subpopulations. In the necrotizing enterocolitis surgical RCT (NEST), which compared laparotomy vs. drain for surgical necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or spontaneous intestinal perforation (SIP), the overall outcome did not differ between the two interventions; however, there was an interaction between preoperative diagnosis and treatment group (P = 0.03).19 With a preoperative diagnosis of NEC, death or NDI occurred in 69% after laparotomy versus 85% with drainage. The Bayesian posterior probability that laparotomy was beneficial for a preoperative diagnosis of NEC was 97%. For preoperative diagnosis of IP, death or NDI occurred in 69% after laparotomy versus 63% with drainage with the Bayesian probability of benefit with laparotomy of 18% (detailed in Chapter 7). Third, an outcome unexpected at the time of trial design was later found to correspond to trends observed in prior trials, i.e., increased mortality associated with phototherapy.18,20 Fourth, the use of a 2x2 factorial design resulted in one factor affecting the primary outcome; e.g., in the Randomized Trial of Minimal Ventilator Support and Early Corticosteroid Therapy to Increase Survival Without Chronic Lung Disease in Extremely-Low-Birth-Weight Infants (SAVE) trial, dexamethasone increased mortality; similarly, in the SUPPORT trial, a lower oxygen saturation target increased mortality; and in the Optimizing Cooling Trial there was an interaction between colder and longer cooling.5,21,22 And fifth, the period from trial design to completion may be prolonged, during which time clinical practices and/or survival at lower gestational ages may have changed.3 Enrollment was terminated in several studies due to emergence of an unanticipated adverse event, while others were terminated for an inability to enroll enough patients (Table 1). A common theme of trials terminated for futility was the need to randomize critically ill infants in a very short time window.

A previous review found that non-significant RCTs in neonatology were published in lower impact journals than positive trials [average impact score 4.2±7.2 (mean±SD) vs. 4.6±5.9, respectively, and median 2.1 vs 2.8).23 In contrast, 12 of 19 NRN trials with non-significant primary outcome were published in the New England Journal of Medicine or the Journal of the American Medical Association. The median impact score (2021 values) of all 19 publications (Table 1) was 91 (interquartile range 4-91), indicating recognition of their rigorous trial design and the importance of the “non-significant” outcomes.24

Several trials with a non-significant primary outcome had a significant difference of an important secondary outcome, such as improved weight gain with earlier weaning from the incubator,25 fewer transfusions for infants in the lower transfusion threshold arm of the Transfusion of Prematures (TOP) study,26 and fewer days of mechanical ventilation in the hydrocortisone trial.27 Some trials have generated data for meta-analysis that either confirmed results from the original trials28 or demonstrated significance of results not seen in individual RCTs, thereby leading to major changes in practice (e.g., less death or BPD with CPAP vs intubation in the delivery room, higher risk of death and necrotizing enterocolitis with lower oxygen saturation targets.29,30

Landmark Trials: Key Contributions of the Neonatal Research Network

While some NRN trials had non-significant results, as outlined above, other major Network trials proved to be landmarks in the field, validating promising new therapies in a large, multicenter RCT. In this section we highlight several examples: inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) for hypoxic respiratory failure in term and near-term infants,41 whole-body hypothermia for HIE in term and near-term infants,42 and the SUPPORT trial comparing the effects of different oxygen saturation targets and CPAP vs immediate surfactant therapy in extremely preterm infants.5,15

The Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study (NINOS):

Hypoxic respiratory failure and persistent pulmonary hypertension in term or near-term infants frequently led to death and/or the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The NINOS trial was the first large multicenter trial of inhaled nitric oxide (iNO), enrolling infants born ≥34 weeks’ gestation with hypoxic respiratory failure refractory to maximal conventional therapy.41 This collaborative trial, conducted by the NRN and the Canadian Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study Group, showed that iNO significantly decreased death or ECMO [46 vs. 64%; relative risk (RR), 0.72; 95 percent confidence interval (CI), 0.57 to 0.91; P = 0.006], with no adverse effects noted. This trial, published in 1997, and the Clinical Inhaled Nitric Oxide Research Group trial (2000)43 provided critical evidence for FDA approval of iNO and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for its use.44 This remains the only labelled indication for iNO.

Whole body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)42:

Moderate or severe HIE leads to very high mortality and neurologic impairment in survivors. Prior to hypothermia, there were no effective therapies for HIE. Research in both head and whole-body cooling showed that whole-body cooling achieved more homogeneous cooling across the brain.45 The NRN subsequently conducted the first multicenter RCT of whole-body cooling in term infants with moderate to severe encephalopathy, starting <6 hours of age and continuing for 72 hours. This resulted in a significant reduction in death or moderate/severe disability at 18-22 months (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.95;P<0.05).42 Two additional multicenter RCTs published the same year showed consistent results.46,47 These studies, together with two subsequent large RCTs48,49 led professional societies in high-resource settings to recommend therapeutic hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy in term infants.44 Caution is warranted in lower-resource settings, as a recent RCT reported no benefits and potential harm.50 Importantly, Apgar scores were collected at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 minutes, allowing analysis of the relationship of Apgar scores with developmental outcomes.,51,52 These data have been used by the Neonatal Resuscitation Program and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation to guide delivery room interventions. The therapeutic hypothermia trials and secondary analyses are discussed in Chapter 6.

The Surfactant, Positive Pressure, and Oxygenation Randomized Trial (SUPPORT):

The SUPPORT trial warrants special consideration for several reasons. Despite substantial research to optimize respiratory interventions, BPD, and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) continue to be prevalent in preterm infants, and both oxygen supplementation and invasive mechanical ventilation are postulated risk factors. Prior to SUPPORT, an oxygen saturation target range of 85-95% was recommended by experts, based on limited evidence. Emerging data suggested that lower saturation targets reduced ROP without adverse effects. An observational multicenter study showed a four-fold increase in retinal ablation in units targeting higher oxygen saturations (88–98%) compared to those targeting 70–90%, with no change in rates of death or cerebral palsy.53 In addition, a single center prospective study targeting saturations <93% found a trend for higher survival rates.54 Thus, emerging data suggested the need for a larger trial to determine optimal oxygen saturation targets.

Similarly, limited data was available from large RCTs on optimizing ventilatory support in preterm infants. Meta-analyses of those trials reported that prophylactic or early surfactant administration decreased the rates of death, air leaks, and death or BPD; however, infants in the control arms also received ventilatory support.55,56 Preliminary evidence suggested that CPAP reduced the need for surfactant and ventilatory support while improving short-term pulmonary outcomes.57,58 Furthermore, a multicenter trial of permissive hypercapnia and minimal ventilatory support strategies following endotracheal intubation markedly reduced ventilatory support including at 36 weeks.59

The SUPPORT trial was a 2X2 factorial trial testing initial CPAP/minimal ventilation vs. surfactant and lower vs. higher oxygen saturation targets.5,15 The rationale for a factorial design was the potential for overlap of the effects of these interventions. For the CPAP vs. surfactant arm, the primary outcome of death or BPD did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.05). However, infants randomized to CPAP/minimal ventilation received fewer days of mechanical ventilation and were more likely to be alive and free from mechanical ventilation by day 7.15 They also less frequently received intubation and postnatal corticosteroids for BPD. In subgroup analysis, death at 36 weeks for infants born at 24-25 weeks was lower in the CPAP group (RR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.5 to 0.92; P=0.01), demonstrating the feasibility of early CPAP at lower gestational ages. A subsequent meta-analysis showed a decrease in BPD or death in infants randomized to the CPAP arms.60 These findings and others led to a statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics recommending early CPAP with later surfactant if needed.61,62 Recent U.S. data showed that use and duration of ventilatory support decreased following these trials and policy statements.63

Infants randomized to the lower saturation target had a higher mortality rate (19.9% vs. 16.2%; RR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.60; P=0.04) but less ROP (8.6% vs. 17.9%; RR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.73; P<0.001), with a non-significant primary outcome (severe ROP or death, 28.3% and 32.1%, RR 0.90; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.06; P=0.21).5 Subsequently, the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services raised concerns that the consent forms did not include the possibility of unknown adverse effects of then currently recommended oxygen saturation targets. In response, there was widespread defense of the SUPPORT trial. The New England Journal of Medicine editors published two editorials, stating in part, “We are dismayed by the response of the OHRP and consider the SUPPORT trial a model of how to make medical progress.”64,65 The NIH leadership published “In support of SUPPORT—a view from the NIH,”66 and ethicists also wrote in support of the trial.67,68

A subsequent individual participant data meta-analysis including four similarly designed trials confirmed the increased mortality and lower risk of retinopathy in the lower oxygen saturation target group, as well as a higher risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, but no difference in mortality or disability (including blindness) at 2-year follow up.30 A recent review of commentaries and consensus statements found that all guidelines since 2011 except one have recommended targeting oxygen saturation ranges of 91% to 95%, 90% to 95%, or avoiding 85% to 89%.69 In summary, the SUPPORT trial, together with other seminal and similarly designed trials, led to fundamental changes in clinical practice worldwide, guiding respiratory therapy for extremely preterm infants.

NRN Partnership Opportunities

With its established infrastructure, the NRN has been attractive to other institutes at NIH as well as other agencies and clinical trials networks. Moreover, the NICHD has actively promoted inter-agency collaborations. The National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Eye Institute (NEI) have funded portions of NRN studies.40,70 The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) funding has been used for studies of neonatal blood pressure and neuromonitoring,35,71 and the CDC has funded several studies of neonatal sepsis.72,73 These co-funders contribute to capitation, follow-up, investigator salary support, and data coordinating center costs, resulting in cost savings from using existing infrastructure. Currently, the NRN is collaborating with other NIH-supported clinical trials groups, including the Idea States Pediatric Clinical Trials Network (ISPCTN) and the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term (HEAL) initiative in the development and implementation of their Eat, Sleep, Console trial (NCT04057820)74 and Opiate Weaning trial (NCT04214834).75

The NRN has also partnered with industry to bring new therapies to newborns, incuding iNO Therapeutics, LLC (nitric oxide for the NINOS trial), Abbott Nutrition (myo-inositol for the inositol RCTs); Exela Pharma Sciences (caffeine for the current MoCHA trial (NCT03340727)); Masimo (programming for oxygen saturation monitors for SUPPORT); and Medtronic (loaned equipment for the near-infrared spectroscopy secondary to the Transfusion of Prematures trial). Industry partnerships are vital to bring new drugs and devices tothe market, especially for high-risk infants.

Evolving with Changing Times and Meeting New Challenges

As illustrated in this chapter, the NRN has been highly productive throughout its more than 35-year history, publishing over 400 manuscripts, conducting more than 40 multicenter RCTs, initiating and maintaining a comprehensive database for extremely preterm infants, establishing a longitudinal follow-up program, and collaborating with other agencies and investigator groups. Along with its many accomplishments, the NRN faces challenges. Pivotal trials often take years to develop and even after scientific review and approval, studies face delays pending available funding and site capacity to conduct multiple simultaneous trials in a limited patient population. Once initiated, trial enrollment in the NICU is often challenging, and some large-scale trials have required 5 or more years to complete.

In 2019, two years before the current NRN was scheduled to complete its 5-year competitive renewal cycle, the NICHD Director presented a Vision for Multisite Clinical Trials Infrastructure as a key component of the NICHD 2020 Strategic Plan. The four guiding principles for 21st Century NICHD-supported research were: 1) enhancing rigor and reproducibility, 2) promoting greater availability of infrastructure, 3) facilitating data sharing and access to biospecimens, and 4) facilitating greater involvement of diverse populations in multisite clinical trials. Details for operationalizing the guiding principles included that all multisite clinical trial protocols be submitted through NIH-peer-review and that greater accessibility to infrastructure would allow introduction of new ideas and perspectives, expand opportunities for investigators at different career stages, and support innovation and stimulate the field. Enhanced data and biospecimen access sharing, incorporating the NIH FAIR data principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) with harmonization of common data elements, and incorporation of artificial intelligence, would greatly expand the impact. Bringing diverse populations into clinical trials is a key step in characterizing and addressing health disparities and broadening the applicability and understanding of research results in diverse populations.

The current NRN membership faced the challenge and opportunity of incorporating these NICHD guiding principles into its current operations. Expanding the number of sites doing NRN clinical trials beyond the ‘NRN core sites’ (those that successfully competed for the NICHD Network) could enhance efficiency and shorten time needed to complete trials, bringing scientific findings to the medical community and the public in a more timely manner. Moreover, such expansion could encourage investigators from non-NRN core sites to bring novel concepts to the NRN, while the NRN’s clinical trial development and implementation experience could help develop the best possible clinical trials. Therefore, in 2020 the NRN developed an Open Network Subcommittee, which developed policies and procedures, and first targeted the NRN Milrinone in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia phase II clinical trial. (NCT02951130).76 This trial focuses on a relatively rare condition with in-hospital study outcomes, making it ideal for a test run of the concept. Given these challenges (and the unforeseen COVID-19 pandemic, which slowed enrollment), the NRN developed policies and procedures for site selection, posted a request for proposals, and a conducted public webinar. An independent site evaluation scoring committee evaluated 8 applications. Four sites were invited to join the study, 3 sites elected to participate, and screening of patients is underway. Future Open Network opportunities will include close review of the capabilities of follow-up programs, which are uniquely supported in the NRN, and are one of the most valuable aspects of NRN infrastructure.

Establishment of the Open Network Subcommittee represents an expansion of the long-standing NRN commitment to collaboration with other agencies, organizations, and investigators described earlier in this chapter. Another example of this commitment is the recent NINDS funding for a collaborative study between investigators at Boston Children’s Hospital and the NRN to investigate machine-learning approaches to brain injury in MRIs from the NRN’s hypothermia trials. This collaboration will leverage the NRN’s already existing unique data and image collection, enabling neuroradiology experts at a non-NRN core site to develop a publicly available approach for assessing clinically obtained MRIs in infants with moderate to severe HIE.

This chapter has introduced the Neonatal Research Network and highlighted some of its many contributions to the care of newborn infants and their families over more than 35 years. The following chapters contain fuller descriptions of the impact of NRN research in areas such as perinatal practices, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, infection, surgical treatment options, and neuroprotection, as well as the critical importance of maintaining a continuing perinatal database and long-term follow-up structure, both for documenting outcomes over time and for developing predictive models of neonatal outcomes. As understanding of the complexity of the influences on health and disease continues to evolve and expand, including the effects of social determinants of disease and health disparities, the NRN also will evolve to continue to lead the way in improving outcomes for sick and preterm infants.

Funding Support

Supported in part by cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (U10 HD21373, UG1 HD21364, UG1 HD21385, UG1 HD27851, UG1 HD27853, UG1 HD27856, UG1 HD27880,UG1 HD27904, UG1 HD34216, UG1 HD36790, UG1 HD40492, UG1 HD40689, UG1 HD53089, UG1 HD53109, UG1 HD68244, UG1 HD68270, UG1 HD68278, UG1 HD68263, UG1 HD68284; UG1 HD87226, UG1 HD87229) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (UL1 TR6, UL1 TR41, UL1 TR42, UL1 TR77, UL1 TR93, UL1 TR105, UL1 TR442, UL1 TR454, UL1 TR1117).

Keywords

- BPCA

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

- BPD

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- ECMO

Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- GDB

Generic Database study

- HEAL

Helping to End Addiction Long-term initiative

- HIE

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- iNO

Inhaled nitric oxide

- ISPCTN

Idea States Pediatric Clinical Trials Network

- MoCHA

Moderately Preterm Infants with Caffeine at Home for Apnea

- NDI

Neurodevelopmental impairment

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- NEST

Necrotizing Enterocolitis Surgery Trial

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- NICHD

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- NIDA

National Institute for Drug Abuse

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NEI

National Eye Institute

- NINDS

National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke

- NINOS

Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- OHRP

Office for Human Research Protections

- PGE1

Prostaglandin E1

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- ROP

Retinopathy of prematurity

- SAVE

Randomized Trial of Minimal Ventilator Support and Early Corticosteroid Therapy to Increase Survival Without Chronic Lung Disease in Extremely-Low-Birth-Weight Infants

- SIP

Spontaneous intestinal perforation

- SUPPORT

Surfactant, Positive Pressure, and Oxygenation Randomized Trial

- TOP

Transfusion of Prematures trial

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Dr. Carlo is a director for MedNax

Dr. Cotten is a consultant for Origin Bioscients and ReAlta Life Sciences. He has received royalties from CryoCell International.

While NICHD staff had input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of NICHD, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Government.

Conflict of Interest

The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Hack M, Merkatz IR, Jones PK, Fanaroff AA. Changing trends of neonatal and postneonatal deaths in very-low-birth-weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980. Aug 1;137(7):797–800. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, et al. for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices, and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022; 327:248–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1039–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, et al. Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:2085–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network, Carlo WA, Finer NN, et al. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1959–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hintz SR, Vohr BR, Bann CM, et al. Preterm neuroimaging and school-age cognitive outcomes. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20174058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vohr BR, Heyne R, Bann C, et al. High blood pressure at early school age among extreme preterms. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20180269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watterberg KL, Hintz SR, Do B, et al. , Adrenal function links to early postnatal growth and blood pressure at age six in children born extremely preterm. Pediatr Res 2019; 86:339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padbury JF, Do BT, Bann CM, et al. DNA methylation in former extremely low birth weight newborns: association with cardiovascular and endocrine function. Pediatr Res 2021: 10.1038/s41390-021-01531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fanaroff AA, Korones SB, Wright LL, et al. A controlled trial of intravenous immune globulin to reduce nosocomial infections in very-low-birth-weight infants. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1107–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shankaran S, Papile LA, Wright LL, et al. The effect of antenatal phenobarbital therapy on neonatal intracranial hemorrhage in preterm infants. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, Stoll BJ, et al. Parenteral glutamine supplementation does not reduce the risk of mortality or late-onset sepsis in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2004;113:1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Meurs KP, Wright LL, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide for premature infants with severe respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2005;353:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole FS, Alleyne C, Barks JD, et al. NIH Consensus Development Conference statement: inhaled nitric-oxide therapy for premature infants. Pediatrics 2011; 127:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network, Finer NN, Carlo WA, et al. Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 10;362):2235]. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1970–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strand M, Jobe AH. The multiple negative randomized controlled trials in perinatology—why? Seminars in Perinatology 2003;27:343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horbar JD, Wright LL, Soll RF, et al. A multicenter randomized trial comparing two surfactants for the treatment of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr 1993;123:757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris BH, Oh W, Tyson JE, et al. ; NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Aggressive vs. conservative phototherapy for infants with extremely low birth weight. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1885–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blakely ML, Tyson JE, Lally KP, et al. , for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health, Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Initial laparotomy versus peritoneal drainage in extremely low birthweight infants with surgical necrotizing enterocolitis or isolated intestinal perforation: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2021; 274:e370–e380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold C, Pedroza C, Tyson JE. Phototherapy in ELBW newborns: does it work? Is it safe? The evidence from randomized clinical trials. Semin Perinatol 2014;38:452–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stark AR, Carlo WA, Tyson JE, et al. Adverse effects of early dexamethasone treatment in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med 2001;344:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:2629–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Littner Y, Mimouni FB, Dollberg S, Mandel D. Negative results and impact factor: a lesson from neonatology. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:1036–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Journal Impact Factor 2021, https://impactfactorforjournal.com/jcr-2021/, accessed 12/06/2021

- 25.Shankaran S, Bell EF, Laptook AR, et al. Weaning of moderately preterm infants from the incubator to the crib: a randomized clinical trial [published correction appears in J Pediatr. 2020 Mar;218:e5]. J Pediatr 2019;204:96–102.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirpalani H, Bell EF, Hintz SR, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Higher or lower hemoglobin transfusion thresholds for preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2639–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watterberg KL, Walsh MC, Li L, et al. Hydrocortisone to improve survival without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1121–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filippone M, Nardo D, Bonadies L, Salvadori S, Baraldi E. Update on postnatal corticosteroids to prevent or treat bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Perinatol 2019;36(S02):S58–S62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramaniam P, Ho JJ, Davis PG. Prophylactic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for preventing morbidity and mortality in very preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD001243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Askie LM, Darlow BA, Finer N, et al. Association between oxygen saturation targeting and death or disability in extremely preterm infants in the neonatal oxygenation prospective meta-analysis collaboration [published correction appears in JAMA. 2018 Jul 17;320:308]. JAMA 2018; 319:2190–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt B, Davis P, Moddemann D, et al. Long-term effects of indomethacin prophylaxis in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:1966–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chock VY, Van Meurs KP, Hintz SR, et al. ; NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Inhaled nitric oxide for preterm premature rupture of membranes, oligohydramnios, and pulmonary hypoplasia. Am J Perinatol 2009;26:317–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh M, Laptook A, Kazzi SN, et al. ; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. A cluster-randomized trial of benchmarking and multimodal quality improvement to improve rates of survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia for infants with birth weights of less than 1250 grams. Pediatrics 2007; 119:876–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeVan JM, Brion LP, Wrage LA, et al. Change in practice after the surfactant, positive pressure, and oxygenation randomized trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2014;99: F386–F390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batton BJ, Li L, Newman NS, Das A, Watterberg KL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Feasibility study of early blood pressure management in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr 2012;161:65–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sood BG, Keszler M, Garg M, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Inhaled PGE1 in neonates with hypoxemic respiratory failure: two pilot feasibility randomized clinical trials. Trials 2014; 15:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on death or disability at age 18 months among neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:57–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedroza C, Tyson JE, Das A, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Advantages of Bayesian monitoring methods in deciding whether and when to stop a clinical trial: an example of a neonatal cooling trial. Trials 2016;17:335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watterberg KL, Fernandez E, Walsh MC, et al. Barriers to enrollment in a randomized controlled trial of hydrocortisone for cardiovascular insufficiency in term and late preterm newborn infants. J Perinatol 2017; 37:1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phelps DL, Watterberg KL, Nolen TL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Effects of myo-inositol on Type 1 retinopathy of prematurity among preterm infants <28 weeks' gestational age: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 320:1649–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study Group. Inhaled nitric oxide in full-term and nearly full-term infants with hypoxic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:1574–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark RH, Kueser TJ, Walker MW, Low-dose nitric oxide therapy for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Clinical Inhaled Nitric Oxide Research Group. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W et al. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. American Academy of Pediatrics. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2014; 133:1146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laptook AR, Shalak L, Corbett RJ. Differences in brain temperature and cerebral blood flow during selective head versus whole-body cooling. Pediatrics 2001; 108:1103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2005; 365:663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eicher DJ, Wagner CL, Katikaneni LP, et al. Moderate hypothermia in neonatal encephalopathy: efficacy outcomes. Pediatr Neurol 2005; 32:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. for the TOBY Study Group. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobs SE, Morley CJ, Inder TE, et al. for the Infant Cooling Evaluation Collaboration. Whole-body hypothermia for term and near-term newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thayyil S, Pant S, Montaldo P et al. Hypothermia for moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy in low-income and middle-income countries (HELIX): a randomized controlled trial in India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. Lancet Glob Health 2021:e1273–e1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Natarajan G, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, et al. Apgar scores at 10 min and outcomes at 6-7 years following hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013; 98:F473–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shukla VV, Bann CM, Ramani M, et al. Predictive ability of 10-minute apgar scores for mortality and neurodevelopmental disability. Pediatrics 2022; 149:e2021054992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tin W, Milligan DW, Pennefather P, Hey E. Pulse oximetry, severe retinopathy, and outcome at one year in babies of less than 28 weeks gestation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001; 84:F106–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chow LC, Wright KW, Sola A, et al. Can changes in clinical practice decrease the incidence of severe retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth weight infants? Pediatrics 2003; 111:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soll R, Ozek E. Prophylactic protein free synthetic surfactant for preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010. Jan 20;(1):CD001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bahadue FL, Soll R. Early versus delayed selective surfactant treatment for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012. Nov 14;11(11):DC001456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verder H, Albertsen P, Ebbesen F, et al. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure and early surfactant therapy for respiratory distress syndrome in newborns of less than 30 weeks' gestation. Pediatrics 1999; 103:E24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, et al. Nasal CPAP or intubation for very preterm infants at birth: The COIN trial. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlo WA, Stark AR, Wright LL, et al. Minimal ventilation to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. J Pediatr 2002; 141:370–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rojas-Reyes MX, Morley CJ, Soll R. Prophylactic versus selective use of surfactant in preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. Mar 14;(3):CD000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carlo WA, Polin RA Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics Respiratory support in preterm infants at birth. Pediatrics 2014; 133:171–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polin RA, Carlo WA, Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics. Surfactant replacement therapy for preterm and term neonates with respiratory distress. Pediatrics 2014; 133:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatch LD 3rd, Clark RH, Carlo WA, et al. Use of respiratory support for preterm infants in the US, 2008-2018. JAMA Pediatr 2021; 175:1017–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drazen JM, Solomon CG, Greene MF. Informed consent and SUPPORT. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1929–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drazen JM, Solomon CG, Morrissey S el at. Support for SUPPORT. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1469–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hudson KL, Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. In support of SUPPORT—a view from the NIH. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2349–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magnus D, Caplan AL. Risk, consent, and SUPPORT. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1864–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lantos JD. Vindication for SUPPORT. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1393–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tarnow-Mordi W, Kirby A. Current recommendations and practice of oxygen therapy in preterm infants. Clin Perinatol 2019; 46:621–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Supplemental Therapeutic Oxygen for Prethreshold Retinopathy Of Prematurity (STOP-ROP), a randomized, controlled trial. I: primary outcomes. Pediatrics 2000; 105:295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernandez E, Watterberg KL, Faix RG, et al. Incidence, management, and outcomes of cardiovascular insufficiency in critically ill term and late preterm newborn infants. Am J Perinatol 2014. ;31:947–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics 2011; 127:817–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stoll BJ, Puopolo KM, Hansen NI et al. Early-onset neonatal sepsis 2015 to 2017, the rise of Escherichia coli, and the need for novel prevention strategies. JAMA Pediatr 2020; 174:e200593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eating, Sleeping, Consoling for Neonatal Withdrawal (ESC-NOW): a Function-Based Assessment and Management Approach ((ESC-NOW)). ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04057820. Accessed April 8, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Trial to Shorten Pharmacologic Treatment of Newborns with Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS). ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04214834. Accessed April 8, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Milrinone in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02951130. Accessed April 8, 2022.