Abstract

Objective:

To assess the added value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) to conventional ultrasound in differentiating benign soft-tissue tumors from malignant ones.

Methods:

197 soft-tissue tumors underwent ultrasound examination with confirmed histopathology were retrospectively evaluated. The radiologists classified all the tumors as benign, malignant, or indeterminate according to ultrasound features. The indeterminate tumors underwent CEUS were reviewed afterwards for malignancy identification by using individual and combined CEUS features.

Results:

Ultrasound analysis classified 62 soft-tissue tumors as benign, 111 tumors as indeterminate and 24 tumors as malignant. There 104 indeterminate tumors were subject to CEUS. Three CEUS features including enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary, and intratumoral arrival time difference were significantly associated with the tumor nature in both univariable and multivariable analysis for the indeterminate tumors (all p < 0.05). When at least one out of the three discriminant CEUS features were present, the best sensitivity of 100% for malignancy identification was obtained with the specificity of 66.7% and the AUC of 0.833. When at least two of the three discriminant CEUS features were present, the best area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.924 for malignancy identification was obtained. The combination of at least two discriminant CEUS features showed much better diagnostic performance than the optimal combination of ultrasound features in terms of AUC (0.924 vs 0.608, p < 0.0001), sensitivity (94.0% vs 42.0%, p < 0.0001), and specificity (90.7% vs 79.6%, p = 0.210) for the indeterminate tumors.

Conclusion:

The combination CEUS features of enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary and intratumoral arrival time difference are valuable to improve the discriminating performance for indeterminate soft-tissue tumors on conventional ultrasound.

Advances in knowledge:

The combination of peritumoral and arrival-time CEUS features can improve the discriminating performance for indeterminate soft-tissue tumors on conventional ultrasound.

Introduction

Soft-tissue tumors are a various group of lesions arising from mesenchymal tissues predominantly. Among them, malignant soft-tissue tumors are rare, with an incidence of about 2.4/100,000 per year.1 Because of their rarity and heterogeneity, general practitioners and radiologists may be lack of familiarity with these tumors.2 About 50% soft-tissue tumors remain indeterminate after primary imaging evaluation,3 which can lead to delayed diagnosis of malignant soft-tissue tumors, followed by a higher risk of metastasis and a lower survival rate.4,5 Accurate imaging evaluation to distinguish malignant from benign soft-tissue tumors is essential.

A multifaceted imaging approaches to evaluate soft-tissue tumors include X-ray radiography, ultrasound, CT and MRI.6–9 Among them, ultrasound is preferred as a preliminary imaging examination for its advantages such as wide availability, real-time imaging, and cost effectiveness. It can even help to characterize the soft-tissue tumors and distinguish malignant from benign lesions with a reasonable accuracy (74.0%–81.2%).10,11 However, there are still a great number of soft-tissue tumors that cannot be characterized correctly by ultrasound. Patients with indeterminate tumors would be hard to manage, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a source of psychological stress.12

Contrast agents are used to enhance tissue contrast in musculoskeletal tumor examinations to improve the diagnostic performance.13 Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has been increasingly implemented in soft-tissue tumor diagnosis as a supplementary technique to conventional ultrasound.14 However, previous studies mainly focused on the perfusion patterns of CEUS in distinguishing benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors, with the sensitivity of 74% and the specificity from 64 to 67%.15,16 With respect to perfusion patterns based on blood flow velocity or contrast uptake curves, the sensitivity was from 78 to 81% and the specificity was from 67 to 68%.17,18 The accuracy of these methods was not satisfactory enough. In order to meet the clinical requirements, more CEUS features need to be studied to improve the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of soft-tissue tumor.

The periphery features of soft-tissue tumors associated with malignancy can reveal a wide range of anomalies on imaging. Previous studies found that contrast-enhanced features of surrounding tissues in soft-tissue sarcoma were associated with its histopathological status and prognosis.19,20 Meanwhile, contrast agent arrival time is useful to implicate different pathologic characteristics of tumors through assessing temporal information of the inflow.21 Previous studies also reported that arrival time was helpful for diagnosing breast and liver malignancies.21,22 These features of CEUS have not been studied in soft-tissue tumors yet. Thus, we hypothesized that the diagnostic performance for soft-tissue tumors can be improved by using peritumoral enhancement features and arrival time indexes in addition to perfusion patterns of CEUS.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the performance of CEUS for differentiation between benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors those deemed to be indeterminate after ultrasound analysis. The periphery features and arrival time indexes of soft-tissue tumors in CEUS were evaluated as well.

Methods and materials

Patients

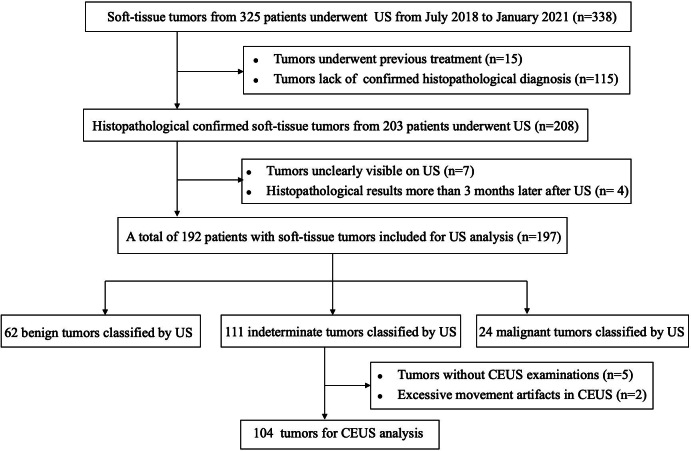

This study was obtained a granted waiver of written informed consent because of the retrospective nature of its design. From July 2018 to January 2021, 325 patients with 338 soft-tissue tumors subjected to ultrasound were consecutively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients with soft-tissue tumors did not undergo previous treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy; (b) the tumor was histopathologically confirmed through core needle biopsy or surgical resection; (c) the tumor underwent ultrasound examination before biopsy or surgery. The exclusion criteria were: (a) the tumor was not clearly visible at ultrasound examination; (b) the interval between ultrasound examination and histopathological results was longer than 3 months. Finally, 197 soft-tissue tumors from 192 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). Among them, 48 soft-tissue tumors underwent simply surgical resection, and 149 soft-tissue tumors underwent pre-surgical biopsy or only biopsy. 133 soft-tissue tumors underwent CEUS before biopsy. Written informed consent of each patient was obtained prior to CEUS and biopsy. 51 of the 192 patients have been previously reported in the study that evaluated the performance of perfusion patterns and the quantitative parameters of CEUS in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors.23

Figure 1.

Flowchart of this study. CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

Imaging

Conventional ultrasound was performed with Acuson S3000 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA, USA), LOGIQ E9 (GE Medical Systems, Wauwatosa, WI, USA), or EPIQ7 (Philips Ultrasound, Bothell, WA, USA) ultrasound scanner by one of the four radiologists (QM, CLM, XJP and AL, all with more than 3 years of experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound) from the institution. The liner transducers with frequency range from 4 to 15 MHz or the convex transducers with frequency range from 1 to 6 MHz were used for ultrasound examination of the soft-tissue tumors. When the target tumor was determined, the grayscale ultrasound and color Doppler ultrasound parameters were adjusted to acquire the optimal image.

CEUS was performed with the LOGIQ E9 (GE Medical Systems, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) ultrasound scanner equipped with the 4–9 MHz liner transducer or 1–6 MHz convex transducer by one of the two radiologists (XJP and AL, both with more than 6 years of experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound). The maximum diameter plane of the soft-tissue tumor was selected as the ideal plane for CEUS, with the tumor and its surrounding normal tissue included. The mechanical index setting of 0.06 to 0.20 was applied. A bolus of 1.5-2.4 ml of the contrast agent (SonoVue, Bracco, Milan, Italy) was intravenously administered followed by a 5 ml-saline flush. A 3 min continuous cine-loops was acquired after contrast injection.

Conventional ultrasound and CEUS image interpretation

Conventional ultrasound and CEUS images of all the soft-tissue tumors were analyzed by two independent radiologists (Reader 1 [MJW] with 3 years of experience in assessing musculoskeletal ultrasound images and Reader 2 [YH] with 5 years of experience in assessing musculoskeletal ultrasound images), who were not involved in ultrasound examination, and both of them were blinded to pathological results. In case of discordance in interpretation of the ultrasound or CEUS features, they reached an agreement by consensus.

Ultrasound features of each tumor including maximal diameter (≥50 mm or <50 mm), depth (superficial or deep to deep fascia), echogenicity (hypoechogeneity or non-hypoechogeneity), internal texture (heterogeneous or homogeneous), shape (regular or irregular), boundary (well-defined or infiltrative), lobulated margin (absent or present), necrosis (absent or present), bone invasion (absent or present), calcification (absent or present) and disorganized color Doppler signals (absent or present) were evaluated.

On the basis of previous studies, nine ultrasound features were considered as malignant appearances: maximal diameter ≥50 mm, depth to deep fascia, hypoechogeneity, irregular shape, lobulated margin, necrosis, bone invasion, calcification and disorganized color Doppler signals24–26 (Figures 2–7A and B). With reference to the previous study,27 soft-tissue tumors were considered benign on ultrasound when two or less features were present. Soft-tissue tumors were considered malignant when seven or more features were present. When three to six features were present, the tumors were considered indeterminate.

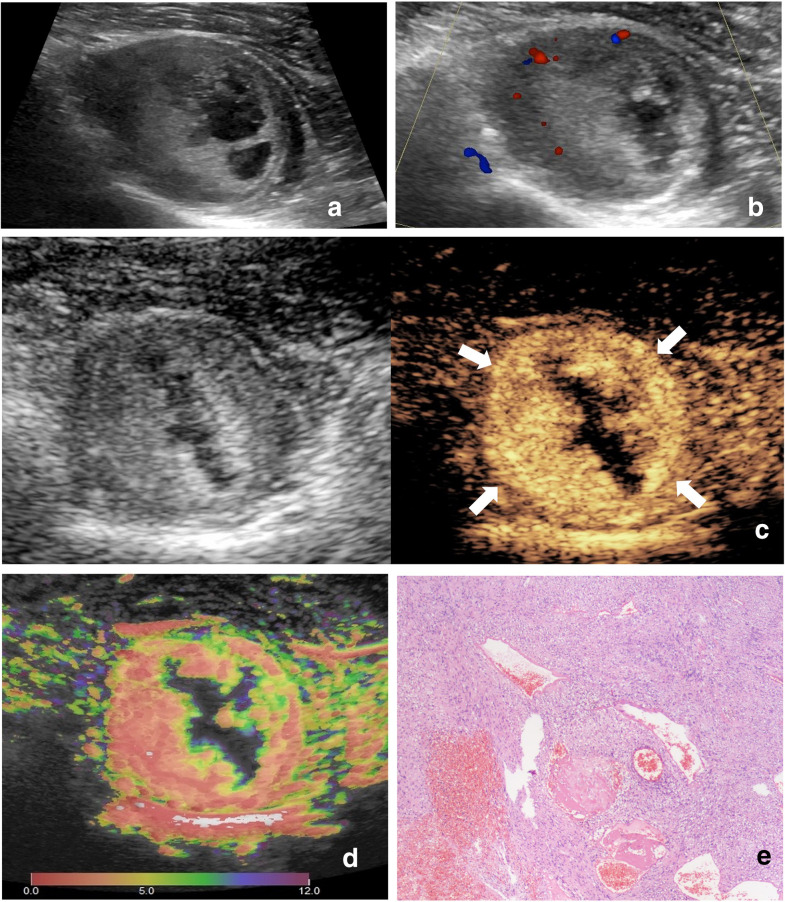

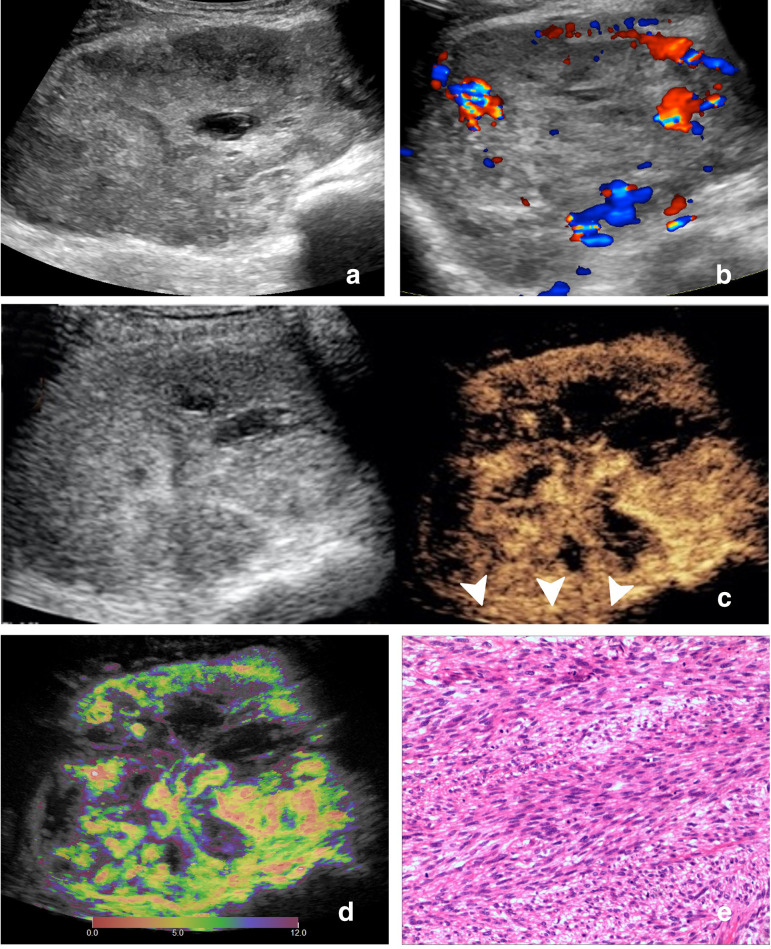

Figure 2.

Images of a 47-year-old female with schwannoma. (A) Ultrasound image and (B) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic, regular, and necrotic tumor with disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P5 tumor with non-enlargement of enhancement area and well-defined enhancement boundary (arrow). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is about 7 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to light green). (E) The tumor is diagnosed as benign with none of the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of schwannoma. AT-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

Figure 3.

Images of a 44-year-old male with nodular fasciitis. (A) Ultrasound image and (B) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic, irregular, and non-necrotic tumor with intratumoral disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P5 tumor with enlargement of enhancement area and well-defined enhancement boundary (arrow). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is about 6 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to yellow). (E) The tumor is diagnosed as possibly benign with one of the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. AT-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

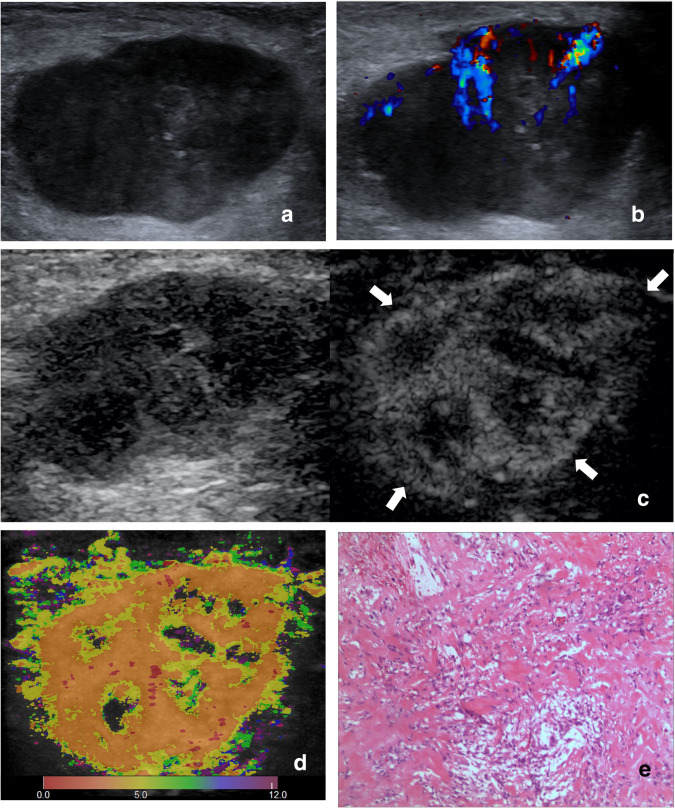

Figure 4.

Images of a 78-year-old female with epithelioid sarcoma. (A) Ultrasound image and (B) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic, irregular, margin lobulated and non-necrotic tumor with intratumoral disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P6 tumor with enlargement of enhancement area and spiculated enhancement boundary (arrow). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is about 8 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to dark green). (E) The tumor is diagnosed as possibly malignant with two of the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of epithelioid sarcoma. At-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

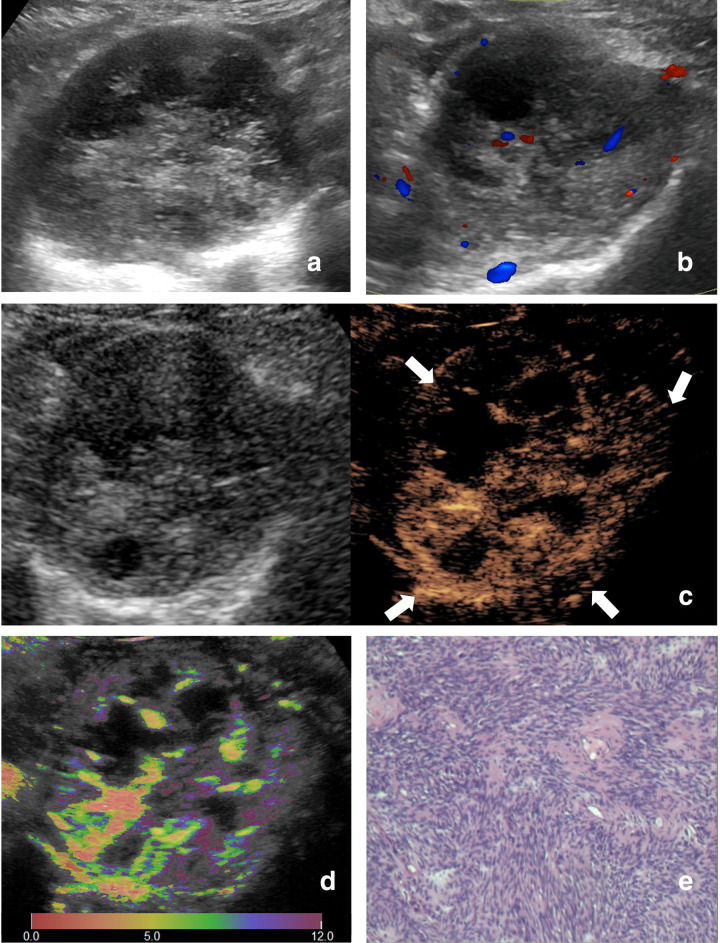

Figure 5.

Images of a 64-year-old male with leiomyosarcoma. (A) Ultrasound image and (B) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic, irregular, margin lobulated and necrotic tumor with intratumoral disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P5 tumor with enlargement of enhancement area and indistinct enhancement boundary >25% (arrowhead). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is 12 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to purple). (E)The tumor is diagnosed as malignant with all the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. At-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

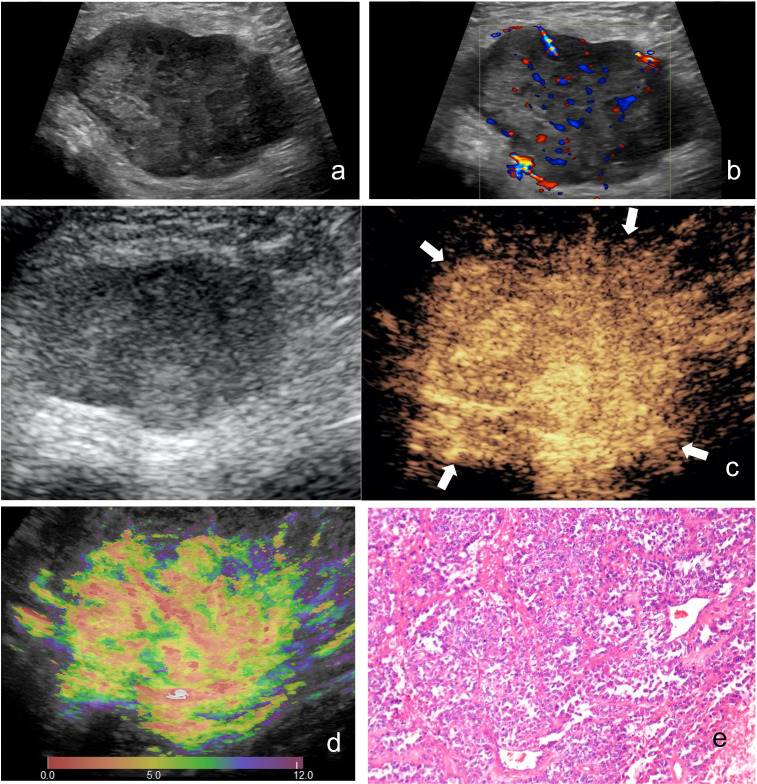

Figure 6.

Images of a 56-year-old female with schwannoma. (A) Ultrasound image and (B) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic, irregular, margin lobulated and necrotic tumor with intratumoral disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P5 tumor with non-enlargement of enhancement area and well-defined enhancement boundary (arrow). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is 12 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to purple). (E) The tumor is diagnosed as possibly benign with one of the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of schwannoma. At-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

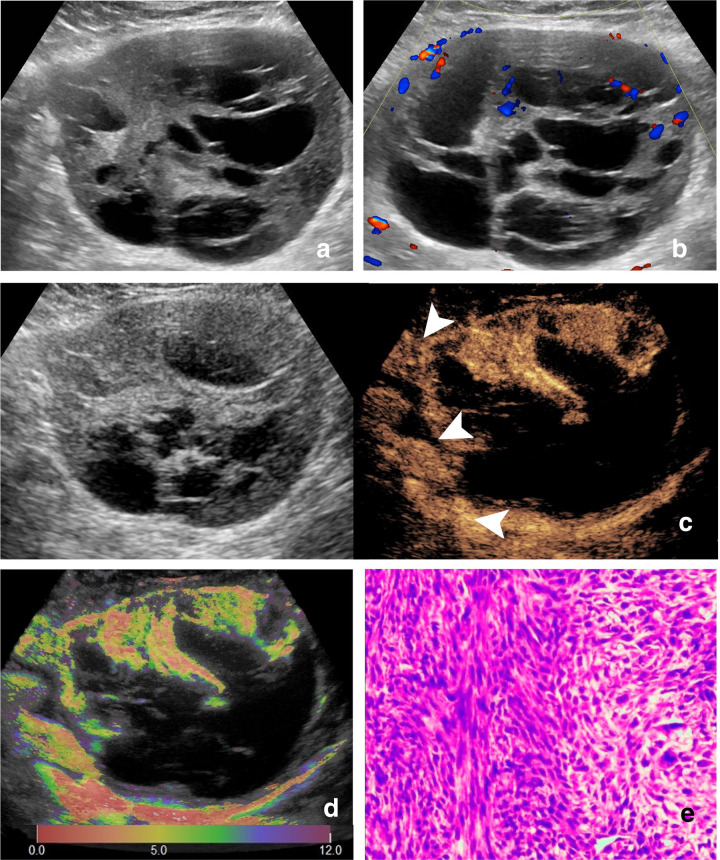

Figure 7.

Images of a 51-year-old female with synovial sarcoma. (A) Ultrasound image and (b) color Doppler ultrasound image show a hypoechoic and necrotic tumor with intratumoral disorganized color Doppler signals, which is classified as indeterminate. (C) CEUS image (right) shows a P5 tumor with enlargement of enhancement area and indistinct enhancement boundary >25% (arrowhead). (D) At-PI shows the intratumoral arrival time difference is about 7 s (the color distribution in the tumor ranges from red to light green). (E) The tumor is diagnosed as possibly malignant with two of the three discriminant CEUS features, and pathologic analysis confirms the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma. At-PI, Arrival-time Parametric Imaging; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

Through reviewing the cine-loops and correlating with the B-mode image on the same section, three qualitative CEUS features of each tumor were recorded based on previous studies and clinical experience: (1) perfusion patterns (Patterns 1–6), defined as follows: P1, non-enhancement; P2, thin rim-like peripheral enhancement; P3, internal punctate distribution enhancement; P4, internal reticular distribution enhancement; P5, inhomogeneous enhancement with intralesional avascular areas; P6, homogeneous whole-lesion enhancement23; (2) enlargement of enhancement area (absent or present), defined as the enhancement area extending outward beyond the tumor area measured in the B-mode image when the contrast agent reaches to the peak19,28; (3) infiltrative enhancement boundary (absent or present), defined as the boundary of the tumor is indistinct (>25%), angular or spiculated in the CEUS image when the contrast agent reaches to the peak19,28 (Figures 2–7C).

Intratumoral arrival time difference which was defined as the earliest and latest arrival time difference of the contrast agent in the tumor could be obtained by using the Arrival-time Parametric Imaging (At-PI) software built in LOGIQ E9. By defining the earliest arrival time of the contrast agent in the tumor as time 0, the At-PI system sequentially computes the arrival time of the contrast agent in the tumor and creates a map automatically superimposed on B-mode images. Different colors are used to represent different arrival times.21 In our study, red represents time 0 and purple represents time 12 (Figures 2–7D). Intratumoral arrival time difference parameter was evaluated with At-PI software and based on review of the CEUS video loops.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (v. 26.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Student’s t-test was used for the comparison of quantitative variables. The χ2 test or Fisher’ exact test was used for the comparison of qualitative variables. The multivariable binary logistic regression was used to identify independent malignancy predictors. A p-value < 0.05 on both sides was considered statistical significance. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine the cut-off value of quantitative variables with maximal Youden’s index. The sensitivity, specificity, and the area under ROC curve (AUC) were estimated for each combination of the independent malignancy predictors. The comparisons between AUCs were performed with Delong’ test. The comparison of sensitivity and specificity were performed with McNemar’ test. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated to assess the interobserver reproducibility. Agreement was considered as poor (ICC, 0.0–0.4), moderate (ICC, 0.4–0.75) and good (ICC, 0.75–1.0).

Results

Basic characteristics

Among the 192 patients included, there were 78 males and 114 females with a mean age of 51.0 ± 15.9 years (range 18–84 years). There were 133 (67.5%) benign and 64 (32.5%) malignant soft-tissue tumors. The mean diameter of all the included tumors were 54.6 ± 34.3 mm (range 6–135 mm). The most common histological types of benign tumors were lipoma (n = 25), schwannoma (n = 19), hemangioma (n = 14), tenosynovial giant cell tumor (n = 8), neurofibroma (n = 7). The most common histological types of malignant tumors were synovial sarcoma (n = 8), metastatic tumor (n = 7), lymphoma (n = 5), angiosarcoma (n = 4), myxoid liposarcoma (n = 4), solitary fibrous tumor (n = 4). Table 1 summarizes the histopathological diagnosis results of all the 197 tumors.

Table 1.

Pathological types and ultrasound classification of 197 soft-tissue tumors (N).

| Pathological types | Total (n = 197) | Classification by ultrasound | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Indeterminate | Malignant | ||

| Benign | 133 | 62 | 70 | 1 |

| Lipoma | 25 | 21 | 4 | 0 |

| Schwannoma | 19 | 7 | 11 | 1 |

| Hemangioma | 14 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| Tenosynovial giant cell tumor | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Neurofibroma | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Desmoid tumor | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Epidermoid cyst | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Nodular fasciitis | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Myositis ossificans | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Hematoma with organization | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Myositis | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Elastofibroma | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Pilomatricoma | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Angioleiomyoma | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Amyloid tumor | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Synovial chondromatosis | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Synovial cyst | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Fibroma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Xanthoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Traumatic neuroma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Myxoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fibroma of tendon sheath | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Leiomyoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Popliteal cyst with organization | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleomorphic lipoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fibrous histiocytoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Malignant | 64 | 0 | 41 | 23 |

| Synovial sarcoma | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Metastatic tumor | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| Lymphoma | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Angiosarcoma | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Multiple myeloma | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Pleomorphic sarcoma | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Myxoid fibrosarcoma | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Well-differentiated liposarcoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Epithelioid sarcoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Malignant peripheral neurilemmoma | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Spindle cell sarcoma | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Malignant mesenchymoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Clear cell sarcoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Malignant melanoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Conventional ultrasound features

The ultrasound features of all the benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors are summarized in Table 2. The nine ultrasound features including maximal diameter, depth, echogenicity, internal texture, shape, boundary, lobulated margin, necrosis, bone invasion, calcification, and disorganized color Doppler signals were all found to be significantly different between benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors (all p < 0.05). 62 soft-tissue tumors were classified as benign with two or less features assessed. 24 soft-tissue tumors were classified as malignant with seven or eight features assessed. 111 soft-tissue tumors were considered to be indeterminate with three to six features assessed. Histopathology confirmed benign nature in all the 62 tumors with a benign ultrasound classification. In the 24 ultrasound considered malignant tumors, one tumor was confirmed to be benign, and 23 tumors were confirmed to be malignant. In the 111 indeterminate tumors on coventional ultrasound, 70 tumors were confirmed to be benign, and 41 tumors were confirmed to be malignant (Table 1). Regarding both indeterminate and malignant tumors as malignant, the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC for detecting malignancy by using ultrasound features were 100%, 46.6% and 0.733, respectively. The highest AUC of 0.781 was obtained by regarding tumors with five or more ultrasound features as malignancy, and the sensitivity and specificity were 73.4 and 82.7%, respectively.

Table 2.

Conventional ultrasound features of the 197 soft-tissue tumors

| Conventional ultrasound features | Total (n = 197) | Benign (n = 133) | Malignant (n = 64) | p- value | Interobserver agreement (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal diameter | <0.001a | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | |||

| Mean diameter | 54.6 ± 34.3 | 43.4 ± 28.4 | 77.8 ± 34.0 | ||

| (mm, range) | (6-135) | (6-133) | (17-135) | ||

| <50 mm | 101 | 85 | 16 | ||

| ≥50 mm | 96 | 48 | 48 | ||

| Depth | 0.002a | 0.875 (0.787–0.928) | |||

| Superficial to deep fascia | 52 | 44 | 8 | ||

| Deep to deep fascia | 145 | 89 | 56 | ||

| Echogenicity | 0.015a | 0.877 (0.791–0.929) | |||

| Hypoechogeneity | 167 | 107 | 60 | ||

| Hyper-/isoechogeneity | 30 | 26 | 4 | ||

| Internal texture | 0.403 | 0.864 (0.770–0.921) | |||

| Homogeneous | 24 | 18 | 6 | ||

| Heterogeneous | 173 | 115 | 58 | ||

| Shape | <0.001a | 0.774 (0.631–0.866) | |||

| Regular | 78 | 67 | 11 | ||

| Irregular | 119 | 66 | 53 | ||

| Boundary | 0.297 | 0.696 (0.585–0.782) | |||

| Well-defined | 133 | 93 | 40 | ||

| Infiltrative | 64 | 40 | 24 | ||

| Lobulated margin | <0.001a | 0.790 (0.654–0.877) | |||

| Absent | 132 | 113 | 19 | ||

| Present | 65 | 20 | 45 | ||

| Necrosis | <0.001a | 0.740 (0.642–0.815) | |||

| Absent | 158 | 113 | 45 | ||

| Present | 39 | 20 | 19 | ||

| Bone invasion | <0.001a | 0.831 (0.691–0.891) | |||

| Absent | 178 | 129 | 49 | ||

| Present | 19 | 4 | 15 | ||

| Calcification | 0.001a | 0.737 (0.575–0.844) | |||

| Absent | 173 | 124 | 49 | ||

| Present | 24 | 9 | 15 | ||

| Disorganized color Doppler signals | <0.001a | 0.831 (0.688–0.891) | |||

| Absent | 118 | 98 | 20 | ||

| Present | 79 | 35 | 44 |

Note. CI, confidence intervals.

Indicates a significant difference between benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors.

CEUS features

Among the 111 indeterminate soft-tissue tumors, 106 tumors underwent CEUS before biopsy and 2 cases of which were excluded for excessive movement artifacts in CEUS examination. Finally, CEUS analysis was available in 104 tumors (54 benign and 50 malignant tumors).

The most common perfusion patterns of the malignant soft-tissue tumors were P5 (26/50, 52.0 %) and P6 (15/50, 30.0 %). The proportions of P5 and P6 in malignancy were higher than those in benign ones (19/54, 35.2% of P5 and 12/54, 22.2% of P6, respectively). The proportions of P2, P3 and P4 in malignancy (4/50, 8% of P2; 1/50, 2% of P3; and 4/50, 8% of P4, respectively) were lower than those in benign ones (8/54, 14.8% of P2; 4/54, 7.4% of P3; and 6/54, 11.1% of P4, respectively). However, the proportions of P2–P6 were not significantly different between benign and malignant tumors (all p > 0.05). P1 images (5/54, 9.3%) were only present in benign tumors, the proportion of P1 was significantly different between benign and malignant tumors (p < 0.05). Nevertheless, the whole perfusion patterns were not significantly different between benign and malignant tumors in the indeterminate tumors (p = 0.08) (Table 3).

Table 3.

CEUS features of 104 indeterminate soft-tissue tumors.

| CEUS features | Total (n = 104) | Benign (n = 54) | Malignant (n = 50) | p- value | Interobserver agreement (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion patterns | 0.08 | 0.769 (0.679–0.837) | |||

| P1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | ||

| P2 | 12 | 8 | 4 | ||

| P3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | ||

| P4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | ||

| P5 | 45 | 19 | 26 | ||

| P6 | 27 | 12 | 15 | ||

| Enlargement of enhancement area | <0.001a | 0.868 (0.790–0.919) | |||

| Absent | 51 | 46 | 5 | ||

| Present | 53 | 8 | 45 | ||

| Infiltrative enhancement boundary | <0.001a | 0.865 (0.787–0.916) | |||

| Absent | 54 | 47 | 7 | ||

| Present | 50 | 7 | 43 | ||

| Intratumoral arrival time difference (s) | 8.51 ± 2.92 | 7.80 ± 3.33 | 9.28 ± 2.18 | 0.009a | 0.913 (0.850–0.950) |

Note. — CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound. CI, confidence intervals. P1–P6, Patterns 1–Patterns 6.

Indicates a significant difference between benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors.

Enlargement of enhancement area (45/50, 90%) and infiltrative enhancement boundary (43/50, 86%) was observed in most malignant soft-tissue tumors (Table 3, Figures 5C and 6C). While non-enlargement of enhancement area (46/54, 85.2%) and well-defined enhancement boundary (47/54, 87.0%) was observed in most benign soft-tissue tumors (Table 3, Figure 2C). Intratumoral arrival time difference of malignant soft-tissue tumors (mean time 9.28 ± 2.18 s, range 5–14 s) were longer than those of benign ones (mean time 7.80 ± 3.33 s, range 0–23 s). The CEUS features of enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary, and intratumoral arrival time difference were significantly different between benign and malignant tumors (all p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Combination of discriminant CEUS features

Three independent CEUS features were identified to be associated with malignant soft-tissue tumors with multivariable analysis: enlargement of enhancement area (OR = 22.740, p < 0.001), infiltrative enhancement boundary (OR = 10.971, p = 0.001), and intratumoral arrival time difference (OR = 1.382, p = 0.014) (Table 4). The ROC analysis showed that 9.5 s of intratumoral arrival time difference was the best cut-off value (sensitivity of 46.0%, specificity of 85.6%) for differentiation between benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors for the indeterminate tumors.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of CEUS features in predicting malignant soft-tissue tumors

| CEUS features | B | SE | Odds Ratios | 95% CIs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enlargement of enhancement area | 3.124 | 0.800 | 22.740 | 4.741–109.072 | < 0.001a |

| Infiltrative enhancement boundary | 2.395 | 0.730 | 10.971 | 2.623–45.879 | 0.001a |

| Intratumoral arrival time difference | 0.324 | 0.131 | 1.382 | 1.069–1.788 | 0.014a |

Note. — CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound. CI, confidence intervals

Indicates a significant difference.

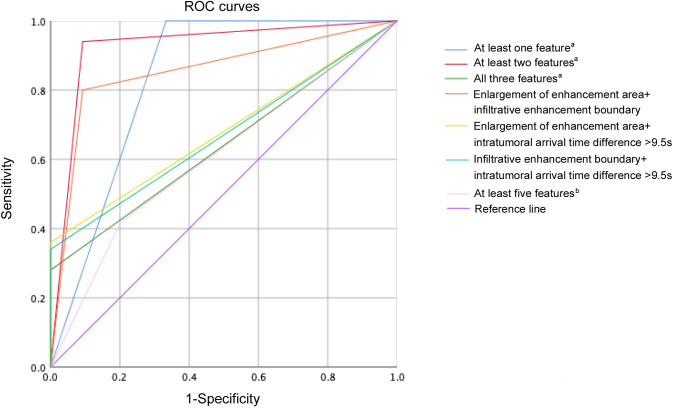

The performances of different combinations of discriminant CEUS features are presented in Table 5 and Figure 8. When at least one of the three discriminant CEUS features were present, the sensitivity for malignancy identification was 100%, with the specificity of 66.7% and the AUC of 0.833. When intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s combined with enlargement of enhancement area or infiltrative enhancement boundary or both, the specificity for malignancy identification was 100%, with the sensitivity of 28.0–36.0% and the AUC of 0.640–0.680. When at least two of the three discriminant CEUS features were present, the highest AUC of 0.924 (all p < 0.05) for malignancy identification was obtained, with the sensitivity of 94.0% and the specificity of 90.7%.

Table 5.

Performances of different combinations of discriminant CEUS features to identify malignant soft-tissue tumors comparing with the performance of the combination of ultrasound features

| Methods | Benign (n = 54) | Malignant (n = 50) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combinations of CEUS features | |||||

| At least one featurea | 100.0 | 66.7 | 0.833b | ||

| Absent | 36 | 0 | |||

| Present | 18 | 50 | |||

| At least two featuresa | 94.0 | 90.7 | 0.924c | ||

| Absent | 49 | 3 | |||

| Present | 5 | 47 | |||

| All three featuresa | 28.0 | 100.0 | 0.640 | ||

| Absent | 54 | 36 | |||

| Present | 0 | 14 | |||

| Enlargement of enhancement area+infiltrative enhancement boundary | 80.0 | 90.7 | 0.854e | ||

| Absent | 49 | 10 | |||

| Present | 5 | 40 | |||

| Enlargement of enhancement area+intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s | 36.0 | 100.0 | 0.680 | ||

| Absent | 54 | 32 | |||

| Present | 0 | 18 | |||

| Infiltrative enhancement boundary+intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s | 34.0 | 100.0 | 0.670 | ||

| Absent | 54 | 33 | |||

| Present | 0 | 17 | |||

| Combination of USultrasound features | |||||

| At least five featuresd | 42.0 | 79.6 | 0.608 | ||

| Absent | 43 | 29 | |||

| Present | 11 | 21 | |||

Note. — CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Features: enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary, intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s.

The AUC of the combination of at least one feature a was significantly higher than those of combinations of all three features a, enlargement of enhancement area +intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s, infiltrative enhancement boundary +intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s and at least five featuresb (p < 0.05).

The AUC of the combination of at least two features a was significantly higher than those of all the other methods (p < 0.05).

Features: maximal diameter ≥50 mm, depth to deep fascia, hypoechogeneity, irregular shape, lobulated margin, necrosis, bone invasion, calcification, and disorganized color Doppler signals.

The AUC of the combination of enlargement of enhancement area +infiltrative enhancement boundary was significantly higher than those of combinations of all three features a, enlargement of enhancement area +intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s, infiltrative enhancement boundary +intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s and at least five featuresb (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

ROC curves of different combinations of discriminant CEUS features and combination of ultrasound features to identify malignant soft-tissue tumors. a Features: enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary, intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s. b Features: maximal diameter ≥50 mm, depth to deep fascia, hypoechogeneity, irregular shape, lobulated margin, necrosis, bone invasion, calcification, and disorganized color Doppler signals. CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

In terms of ultrasound features, the highest AUC of 0.608 was obtained by regarding tumors with at least five features as malignancy in the indeterminate tumors, with the sensitivity of 42.0% and specificity of 79.6%. The combinations of at least two discriminant CEUS features showed much better diagnostic performance than the optimal combinations of ultrasound features in terms of AUC (0.924 vs 0.608, p < 0.0001) and sensitivity (94.0% vs 42.0%, p < 0.0001) for the indeterminate tumors.

Interobserver agreement

The interobserver agreement and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are shown in Table 3 for ultrasound features and Table 4 for CEUS features, respectively. The interobserver agreement for all the ultrasound features was between 0.737 (95% CIs: 0.575–0.844) and 0.877 (95% CIs: 0.791–0.929). Meanwhile, the interobserver agreement for all the CEUS features was between 0.769 (95% CIs: 0.679–0.837) and 0.913 (95% CIs: 0.850–0.950).

Discussion

Soft-tissue tumors are a group of heterogeneous tumors, while benign and malignant tumors still have imaging characteristics overlap in a number of cases.29 We tried to investigate whether CEUS can help to improve the performance of ultrasound in differentiating benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors in indeterminate cases. Our results provide data that can be used to establish the supplemental role of CEUS.

Conventional ultrasound is possibly good in diagnostic performance for a considerable proportion of soft-tissue tumors. Through assessing the conventional ultrasound features, 62 tumors were considered to be benign with no false-negative tumors in the present study. This showed that a number of soft-tissue tumors can be readily diagnosed by typical ultrasound findings, like typical lipoma, hemangioma, etc.30,31 When seven or eight malignant ultrasound features were assessed, 24 tumors were considered to be malignant with one false-positive tumor of schwannoma in the study, which showed sometimes a puzzle of schwannoma diagnosis for radiologists.32 The ultrasound diagnostic performance was good in the very likely benign and malignant tumor groups. However, with a large number of indeterminate tumors, the specificity for ultrasound diagnostic performance was low to be only 46.6%. Therefore, additional modality such as CEUS was needed for malignancy identification in the indeterminate tumors.

CEUS patterns offer important information about differentiation of soft-tissue tumors. All the P1 lesions were benign in the current study, which was the same as the previous studies.23,33 CEUS pattern of P1 was a strong predictor of the final classification as benign. However, the proportions of P2–P6 were not significantly different between benign and malignant tumors. The perfusion patterns of CEUS did not show obvious diagnostic efficiency in a population of indeterminate tumors, either. Those findings were different from previous studies, indicating that patient selection criteria might affect the diagnostic performance.15,16

Enlargement of enhancement area and enhancement boundary have been previously studied for the detection of malignant breast tumors.34 When observed in soft-tissue tumors, both of them showed significant difference between benign and malignant tumors in the indeterminate population. Enlargement of enhancement area reflected increased vascularity at the periphery and aggressive peripheral growth pattern of malignant tumors.35,36 Infiltrative enhancement boundary indicated the tumor cells infiltrating the surrounding tissues and showed the invasiveness of the tumor.37 These previously ignored CEUS features could provide essential diagnostic information of malignant soft-tissue tumors.

Another important finding was referred to intratumoral arrival time difference of CEUS in soft-tissue tumors. Arrival time difference can exhibit homogeneity or heterogeneity of tumors in CEUS.22,38 Heterogeneity in malignant soft-tissue tumors were associated with their complex genome.39 Intratumoral arrival time difference of malignant soft-tissue tumors was longer than benign ones in our study. The longer the intratumoral arrival time difference was, the more intratumoral colors appeared in the At-PI.

In multivariable analysis, the discriminant CEUS features were identified as following: enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary and intratumoral arrival time difference. The added value of CEUS over ultrasound was prominent in the current study. The best sensitivity of 100% of combinations of discriminant CEUS features was obtained when at least one feature was present, with all the malignant tumors correctly classified. This was clinically useful to safely dismiss the negative tumors, and the AUC of 0.833 was relatively high. The best specificity of 100% was obtained when intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s combined with one or both of the other two discriminant CEUS features, while their low sensitivities reduced the applicability. The best AUC of 0.924 was obtained when at least two out of the three discriminant CEUS features were present, which was similar to that of using contrast-enhanced MRI (AUC, 0.815–0.915) in a previous study.40

The diagnostic performance of ultrasound in indeterminate tumors was much worse than that in all the tumors (AUC, 0.608 vs 0.781), as demonstrated in the current study, which showed the deficiency of ultrasound in characterization of soft-tissue tumors. When using the optimal combinations of CEUS features, the AUC was obviously improved than that of ultrasound evaluation (0.924 vs 0.608) in the indeterminate tumors. In addition, interobserver agreement for the CEUS features of enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary and intratumoral arrival time difference illustrated good consistency. This would make CEUS diagnostic performance of soft-tissue tumors less influenced by different radiologists in clinical application.

Several limitations of our study warranted further investigation. First, we included only the soft-tissue tumors with definite histopathological results. That resulted in a relatively large size of the studied tumors. The diagnostic performance could be further compared in different sizes to assess a larger population of soft-tissue tumors. Second, our study did not incorporate all available information gathered by CEUS like time intensity curve and its quantitative parameters. Instead, we used the visible and coherent CEUS features to increase clinical availability. Third, this was a retrospective study. The constitution of soft-tissue tumors was a large range of mesenchymal lesions, thus prospective study is needed in future to validate our results.

In conclusion, the current study helps to define the role of CEUS in soft-tissue tumor characterization. Conventional ultrasound features analysis could classify a portion of obviously benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors. The combination CEUS features of enlargement of enhancement area, infiltrative enhancement boundary and intratumoral arrival time difference >9.5 s are valuable to improve the malignancy discriminating performance for indeterminate tumors on conventional US.

Contributor Information

Yu Hu, Email: helenhuyu@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Ao Li, Email: cqh2liao@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Meng-Jie Wu, Email: wumengjie@jsph.org.cn, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Qian Ma, Email: aprilmaq@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Cui-Lian Mao, Email: mcl19890421@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Xiao-Jing Peng, Email: 13813992395@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Xin-Hua Ye, Email: yexh-0125@163.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Bo-Ji Liu, Email: jxjj1990@126.com, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Hui-Xiong Xu, Email: xu.huixiong@zs-hospital.sh.cn, Department of Medical Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wibmer C, Leithner A, Zielonke N, Sperl M, Windhager R. Increasing incidence rates of soft tissue sarcomas? a population-based epidemiologic study and literature review. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 1106–11. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soomers V, Husson O, Young R, Desar I, Van der Graaf W. The sarcoma diagnostic interval: a systematic review on length, contributing factors and patient outcomes. ESMO Open 2020; 5(1): e000592. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fayad LM, Jacobs MA, Wang X, Carrino JA, Bluemke DA. Musculoskeletal tumors: how to use anatomic, functional, and metabolic Mr techniques. Radiology 2012; 265: 340–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saithna A, Pynsent PB, Grimer RJ. Retrospective analysis of the impact of symptom duration on prognosis in soft tissue sarcoma. Int Orthop 2008; 32: 381–84. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0319-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakamura T, Matsumine A, Matsubara T, Asanuma K, Uchida A, Sudo A. The symptom-to-diagnosis delay in soft tissue sarcoma influence the overall survival and the development of distant metastasis. J Surg Oncol 2011; 104: 771–75. doi: 10.1002/jso.22006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miwa S, Otsuka T. Practical use of imaging technique for management of bone and soft tissue tumors. J Orthop Sci 2017; 22: 391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li A, Peng XJ, Ma Q, Dong Y, Mao CL, Hu Y. Diagnostic performance of conventional ultrasound and quantitative and qualitative real-time shear wave elastography in musculoskeletal soft tissue tumors. J Orthop Surg Res 2020; 15(1): 103. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01620-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yokouchi M, Terahara M, Nagano S, Arishima Y, Zemmyo M, Yoshioka T, et al. Clinical implications of determination of safe surgical margins by using a combination of CT and 18FDG-positron emission tomography in soft tissue sarcoma. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011; 12: 166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subhawong TK, Jacobs MA, Fayad LM. Diffusion-Weighted MR imaging for characterizing musculoskeletal lesions. Radiographics 2014; 34: 1163–77. doi: 10.1148/rg.345140190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charnock M, Kotnis N, Fernando M, Wilkinson V. An assessment of ultrasound screening for soft tissue lumps referred from primary care. Clin Radiol 2018; 73: 1025–32. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.07.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hung EHY, Griffith JF, Yip SWY, Ivory M, Lee JCH, Ng AWH, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound in the characterization of superficial soft tissue tumors: a prospective study. Skeletal Radiol 2020; 49: 883–92. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03365-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tedesco NS, Henshaw RM. Unplanned resection of sarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016; 24: 150–59. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leplat C, Hossu G, Chen B, De Verbizier J, Beaumont M, Blum A, et al. Contrast-Enhanced 3-T perfusion MRI with quantitative analysis for the characterization of musculoskeletal tumors: is it worth the trouble? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018; 211: 1092–98. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang P, Wu M, Li A, Ye X, Li C, Xu D. Diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for differential diagnosis of malignant and benign soft tissue masses: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol 2020; 46: 3179–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oebisu N, Hoshi M, Ieguchi M, Takada J, Iwai T, Ohsawa M, et al. Contrast-Enhanced color Doppler ultrasonography increases diagnostic accuracy for soft tissue tumors. Oncol Rep 2014; 32: 1654–60. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gruber L, Loizides A, Luger AK, Glodny B, Moser P, Henninger B, et al. Soft-Tissue tumor contrast enhancement patterns: diagnostic value and comparison between ultrasound and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017; 208: 393–401. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Marchi A, Prever EBD, Cavallo F, Pozza S, Linari A, Lombardo P, et al. Perfusion pattern and time of vascularisation with CEUS increase accuracy in differentiating between benign and malignant tumours in 216 musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gay F, Pierucci F, Zimmerman V, Lecocq-Teixeira S, Teixeira P, Baumann C, et al. Contrast-Enhanced ultrasonography of peripheral soft-tissue tumors: feasibility study and preliminary results. Diagn Interv Imaging 2012; 93: 37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crombé A, Le Loarer F, Stoeckle E, Cousin S, Michot A, Italiano A, et al. Mri assessment of surrounding tissues in soft-tissue sarcoma during neoadjuvant chemotherapy can help predicting response and prognosis. Eur J Radiol 2018; 109: 178–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong JH, Jee WH, Jung CK, Jung JY, Shin SH, Chung YG. Soft tissue sarcoma: adding diffusion-weighted imaging improves MR imaging evaluation of tumor margin infiltration. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 2589–97. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5817-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu W, Dong Y, Zhang X, Zhang H, Li F, Bai M. The clinical value of arrival-time parametric imaging using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in differentiating benign and malignant breast lesions. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2020; 75: 369–82. doi: 10.3233/CH-200826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li W, Wang W, Liu G-J, Chen L-D, Wang Z, Huang Y, et al. Differentiation of atypical hepatocellular carcinoma from focal nodular hyperplasia: diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced US and microflow imaging. Radiology 2015; 275: 870–79. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu M, Hu Y, Hang J, Peng X, Mao C, Ye X, et al. Qualitative and quantitative contrast-enhanced ultrasound combined with conventional ultrasound for predicting the malignancy of soft tissue tumors. Ultrasound Med Biol 2022; 48: 237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2021.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lakkaraju A, Sinha R, Garikipati R, Edward S, Robinson P. Ultrasound for initial evaluation and triage of clinically suspicious soft-tissue masses. Clin Radiol 2009; 64: 615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gielen JLMA, De Schepper AM, Vanhoenacker F, Parizel PM, Wang XL, Sciot R, et al. Accuracy of MRI in characterization of soft tissue tumors and tumor-like lesions. A prospective study in 548 patients. Eur Radiol 2004; 14: 2320–30. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2431-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morii T, Kishino T, Shimamori N, Motohashi M, Ohnishi H, Honya K, et al. Differential diagnosis between benign and malignant soft tissue tumors utilizing ultrasound parameters. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2018; 45: 113–19. doi: 10.1007/s10396-017-0796-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dodin G, Salleron J, Jendoubi S, Abou Arab W, Sirveaux F, Blum A, et al. Added-value of advanced magnetic resonance imaging to conventional morphologic analysis for the differentiation between benign and malignant non-fatty soft-tissue tumors. Eur Radiol 2021; 31: 1536–47. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07190-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X-L, Lu F, Zhu A-Q, Du D, Zhang Y-F, Guo L-H, et al. Multimodal ultrasound imaging in breast imaging-reporting and data system 4 breast lesions: a prediction model for malignancy. Ultrasound Med Biol 2020; 46: 3188–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Imaging of soft-tissue musculoskeletal masses: fundamental concepts. Radiographics 2016; 36: 1931–48. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klauser AS, Tagliafico A, Allen GM, Boutry N, Campbell R, Court-Payen M, et al. Clinical indications for musculoskeletal ultrasound: a delphi-based consensus paper of the European Society of musculoskeletal radiology. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1140–48. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2356-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carra BJ, Bui-Mansfield LT, O’Brien SD, Chen DC. Sonography of musculoskeletal soft-tissue masses: techniques, pearls, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202: 1281–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meyer A, Billings SD. What’s new in nerve sheath tumors. Virchows Arch 2020; 476: 65–80. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02671-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loizides A, Peer S, Plaikner M, Djurdjevic T, Gruber H. Perfusion pattern of musculoskeletal masses using contrast-enhanced ultrasound: a helpful tool for characterisation? Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1803–11. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2407-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Niu RL, Li SY, Wang B, Jiang Y, Liu G, Wang ZL. Papillary breast lesions detected using conventional ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound: imaging characteristics and associations with malignancy. Eur J Radiol 2021; 141: 109788. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ma LD, Frassica FJ, McCarthy EF, Bluemke DA, Zerhouni EA. Benign and malignant musculoskeletal masses: MR imaging differentiation with rim-to-center differential enhancement ratios. Radiology 1997; 202: 739–44. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao F, Ahlawat S, Farahani SJ, Weber KL, Montgomery EA, Carrino JA, et al. Can MR imaging be used to predict tumor grade in soft-tissue sarcoma? Radiology 2014; 272: 192–201. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Engellau J, Bendahl P-O, Persson A, Domanski HA, Akerman M, Gustafson P, et al. Improved prognostication in soft tissue sarcoma: independent information from vascular invasion, necrosis, growth pattern, and immunostaining using whole-tumor sections and tissue microarrays. Hum Pathol 2005; 36: 994–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yin SS, Cui QL, Fan ZH, Yang W, Yan K. Diagnostic value of arrival time parametric imaging using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in superficial enlarged lymph nodes. J Ultrasound Med 2019; 38: 1287–98. doi: 10.1002/jum.14809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fadli D, Kind M, Michot A, Le Loarer F, Crombé A. Natural changes in radiological and radiomics features on mris of soft-tissue sarcomas naïve of treatment: correlations with histology and patients’ outcomes. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022; 56: 77–96. doi: 10.1002/jmri.28021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bian Y, Jin P, Wang Y, Wei X, Qiang Y, Niu G, et al. Clinical applications of DSC-MRI parameters assess angiogenesis and differentiate malignant from benign soft tissue tumors in limbs. Acad Radiol 2020; 27: 354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]