Abstract

Objective:

Telemedicine use expanded greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic and broad use of telemedicine is expected to persist beyond the pandemic. More evidence on the efficiency and safety of different telemedicine modalities is needed to inform clinical and policy decisions around telemedicine use. To evaluate the efficiency and safety of telemedicine, we compared treatment and follow-up care between video and telephone visits during COVID-19 pandemic.

Study Design:

Observational study of patient-scheduled telemedicine visits for primary care.

Method:

We used multivariate logistic regression to compare treatment (medication prescribing, lab/imaging orders) and 7-day follow-up care (in-person office visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations) between video and telephone visits, adjusted for patient characteristics.

Results:

Among 734,442 telemedicine visits, 58.4% were telephone visits. Adjusted rates of medication prescribing and lab/imaging orders were higher in video visits than telephone visits with differences of 3.5% (95% CI: 3.3–3.8), and 3.9% (95% CI: 3.6–4.1) respectively. Adjusted rates of 7-day follow-up in-person office visits, emergency department visits and hospitalizations were lower after video than telephone visits with differences of 0.7% (95%CI: 0.5–0.9), 0.3% (95% CI: 0.2–0.3), and 0.04% (95% CI: 0.02–0.06), respectively.

Conclusions:

Among telemedicine visits with primary care clinicians, return visits were not common and downstream emergency events were rare. Adjusted rates of treatment were higher and adjusted rates of follow-up care were lower for video visits than telephone visits. While video visits were marginally more efficient than telephone visits, telephone visits may offer an accessible option to address patient primary care needs without raising safety concerns.

Keywords: telemedicine, video visits, telephone visits, efficiency, safety

Précis:

Telephone visits may offer a simple and convenient option to address patient primary care needs without raising safety concerns

Introduction

Telemedicine use expanded greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic, via either video or telephone visits 1,2. Temporary provisions provided coverage for telemedicine using either video or telephone for most services 3. While broad use of telemedicine is expected to persist beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, national regulatory and payment policies for telephone visits may be more limited than for video visits4. Evidence is needed to inform clinical and policy decisions around telemedicine use, including how treatment and follow-up care differ between video and telephone visits.

Video visits can convey visual information and offer a “face-to-face” connection which could be helpful to both patients and clinicians 5. However, video visits have additional technical requirements such as a reasonably strong internet connection, a video-enabled device, and digital literacy. These factors may be a barrier to care for some patients. Attention is needed to address the digital divide, particularly since not all patients have equal access to the technology needed to conduct telemedicine visits via video 6–8. Despite uncertainty in long term payment models, both video- and telephone-based virtual care options are likely to offer patients important venues to access primary care clinicians. However, whether telemedicine primary care visits delivered using video versus telephone result in differential treatment and follow-up health care utilization is unknown.

During the early COVID-19 pandemic period, in a large integrated delivery system that temporarily shifted all patient-initiated primary care visits to telemedicine, we used the health system’s research data warehouse and electronic health record (EHR) data to examine whether rates of medication prescribing and lab/imaging orders differed and whether patients were more likely to require follow-up in-person office visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations for telephone visits compared with video visits. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficiency and safety of telemedicine. We hypothesized that serious outcomes (downstream ED visits and hospitalizations) would be rare after both video and telephone visits, but that more patients would require additional follow-up in-person visits after telephone visits than video visits.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted within Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated health care delivery system with about 4.5 million members representative of the insured Northern California region except at the lowest incomes 9. Since 2016, KPNC members can directly choose between an in-person, telephone, or video visit when self-scheduling a visit with their primary care clinician using the patient portal website or mobile app. Despite the availability of telemedicine, in-person visits were still the most common way to receive primary care prior to the pandemic 10. However, due to social distancing measures aimed at preventing COVID-19 exposure starting in mid-March 2020, patients could only choose between a telephone or video visit when self-scheduling an appointment. In-person office visits were available based on a physician’s recommendation and after an initial telemedicine visit. These protocols continued throughout the study period.

Study population and data

Using the EHR, and other health system research data sources, we identified all patient-initiated primary care telemedicine visits scheduled through the portal website or mobile applications between 3/16/2020–10/31/2020. To define a relatively distinct care-seeking episode, we excluded visits for patients who had any visit within the previous seven days. For each visit, we identified any medication prescribing, antibiotics prescribing, and lab/imaging orders during the index visit as treatment measures. To characterize short-term follow-up health care utilization, we extracted all in-person office visits, ED visits and hospitalizations that occurred within seven days after each index visit. We used medication prescribing, lab/imaging orders and 7-day follow-up in-person visit to assess efficiency (i.e., whether telemedicine can adequately address the clinical concern without the need for an in-person visit), and downstream ED visits and hospitalization to assess safety.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression models to examine the association between index visit type (telephone vs. video) and outcomes. We ran separate models for each outcome of treatment (including medication prescribing, antibiotics prescribing and lab/image orders during the visit), and follow-up health care utilization (including in-person office visits, ED visits and hospitalizations within seven days after the index visit). All models were adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, lower neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES; at least 20% of households have household incomes below the federal poverty level or at least 25% of residents 25 years of age or older have less than a high school education in the census block group), preferred language for health care, lower neighborhood internet access (no more than 80% of households have a residential fixed high-speed connection with at least 10 Mbps downstream and at least 1 Mbps upstream in the census tract based on FCC data), any mobile portal use in prior 365 days, any video visits in prior 365 days, whether the clinician was the patient’s own primary care clinician, patient medical problem (ICD10 code grouping of primary diagnosis), presence of chronic conditions, and medical center. Standard errors were adjusted for the repeated visits within patients.

For easier interpretation, we calculated adjusted rates of each outcome by index visit type using the coefficients from the multivariate logistic regression as if the entire cohort were having a video visit and as if the entire cohort were having a telephone visit respectively, and then calculated the difference in adjusted rates between video and telephone visit for each outcome. All analyses were conducted using two-sided tests for significance, and p<0.05 as the threshold for significance, in Stata 17.0, StataCorp LLC, TX.

The Institutional Review Board of the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute approved the study protocol and materials and waived the requirement for written informed consent for participants.

Results

Among 734,442 primary care telemedicine visits scheduled using the patient portal by 567,130 patients during the study period, 58.4% were by telephone. Overall, 12.2% were younger than 18 years old, 72.8% were between 18 and 64 years old, 15.0% were 65 years and older, 43.6% were male, 47.6% were of non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity, 19.9% lived in a neighborhood with lower SES, 39.8% lived in a neighborhood with lower internet access, 23.5% had at least one video visit in prior 365 days and 57.9% had mobile portal access in prior 365 days, and 75.7% were with the patients’ own primary care clinician (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by video and telephone visits

| Characteristics | All Visits, No. (col%) | Video Visits, No. (col%) | Telephone Visits, No. (col%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total | 734442(100.0) | 305205(100.0) | 429237(100.0) |

| Age group | |||

| <18 | 89728(12.2) | 44079(14.4) | 45649(10.6) |

| 18–44 | 331437(45.1) | 130820(42.9) | 200617(46.7) |

| 45–64 | 202908(27.6) | 78575(25.7) | 124333(29) |

| 65+ | 110369(15.0) | 51731(17.0) | 58638(13.7) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 320308(43.6) | 137698(45.1) | 182610(42.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 349205(47.6) | 146841(48.1) | 202364(47.2) |

| Black | 50517(6.9) | 18573(6.1) | 31944(7.4) |

| Hispanic | 148778(20.3) | 51544(16.9) | 97234(22.7) |

| Asian | 172222(23.5) | 82663(27.1) | 89559(20.9) |

| Low Neighborhood SES | 146094(19.9) | 52272(17.1) | 93822(21.9) |

| Low Neighborhood internet | 292102(39.8) | 110127(36.1) | 181975(42.4) |

| Preferred language English | 681822(92.8) | 284200(93.1) | 397622(92.6) |

| Video visit in prior 365 days | 172639(23.5) | 94686(31) | 77953(18.2) |

| Mobile portal access in prior 365 days | 424979(57.9) | 179033(58.7) | 245946(57.3) |

| Visit with own Primary Care Clinician | 556130(75.7) | 238049(78) | 318081(74.1) |

| Presence of chronic conditions | 197502(26.9) | 76493(25.1) | 121009(28.2) |

Lower neighborhood SES: at least 20% of households have household incomes below the federal poverty level or at least 25% of residents 25 years of age or older have less than a high school education in the census block group

Lower neighborhood internet access: no more than 80% of households have a residential fixed high-speed connection with at least 10 Mbps downstream and at least 1 Mbps upstream in the census tract-based FCC data

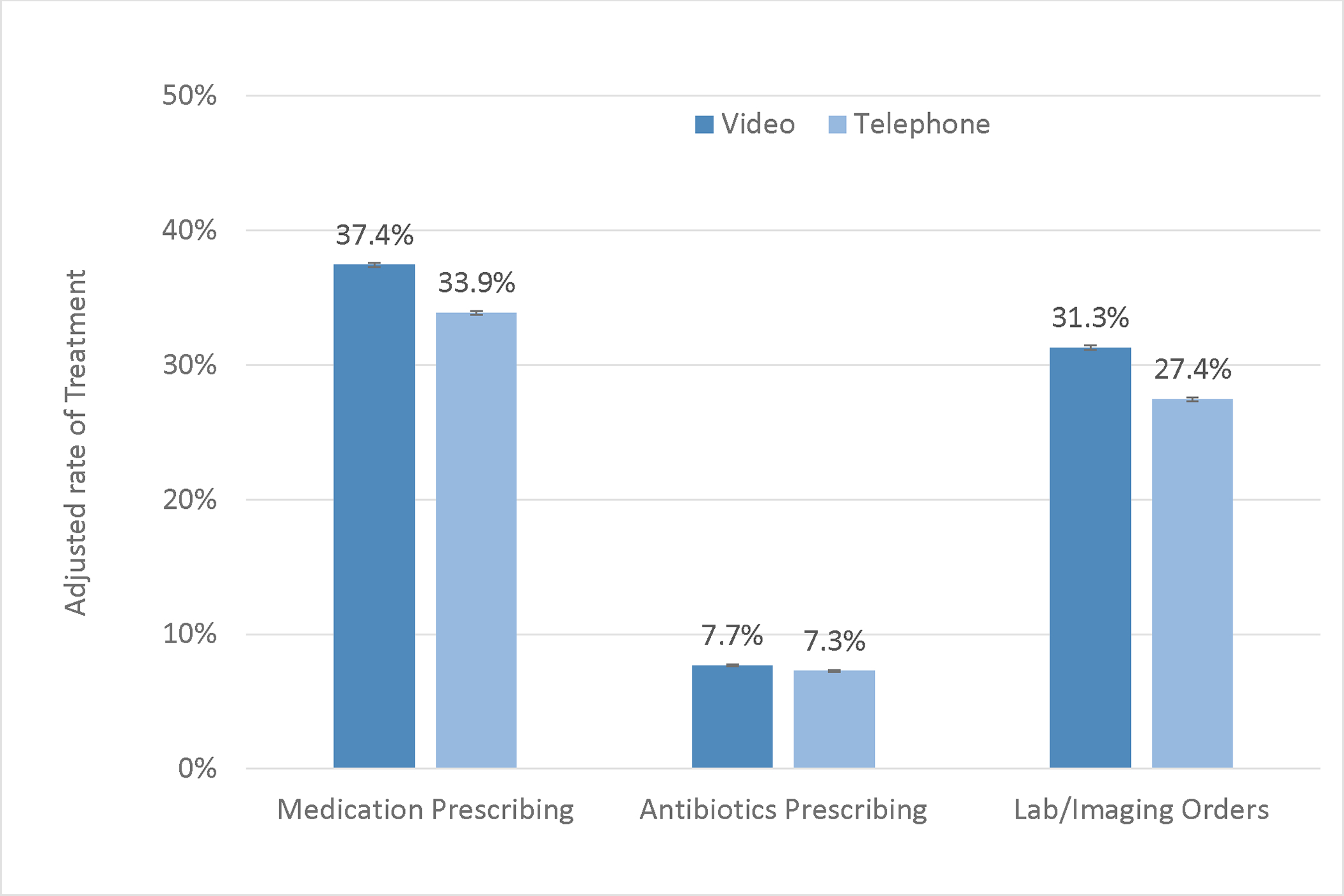

Figure 1 shows adjusted rate of treatment by telephone and video visit. Adjusted rate of medication prescribing was 3.5% (95% CI: 3.3–3.8) higher in video visits than telephone visits: 37.4% of video visits had a medication prescribed compared with 33.9% of telephone visits. Adjusted rate of antibiotic prescribing was 0.4% (95% CI: 0.3–0.5) higher in video visits than telephone visits: 7.7% of video visits had an antibiotic prescribed compared with 7.3% of telephone visits. Adjusted rate of lab/imaging orders was 3.9% (95% CI: 3.6–4.1) higher in video visits than telephone visits: 31.3% of video visits had a lab/imaging order placed compared with 27.4% of telephone visits. All the differences between telephone and video were statistically significant.

Figure 1. Adjusted rates of treatment by video and telephone visits.

Adjusted rates were calculated by using coefficients from multivariate logistic regression for each outcome adjusted for characteristics in table 1, ICD 10 grouping, and medical center as if the entire cohort were having a video visit and as if the entire cohort were having a telephone visit respectively.

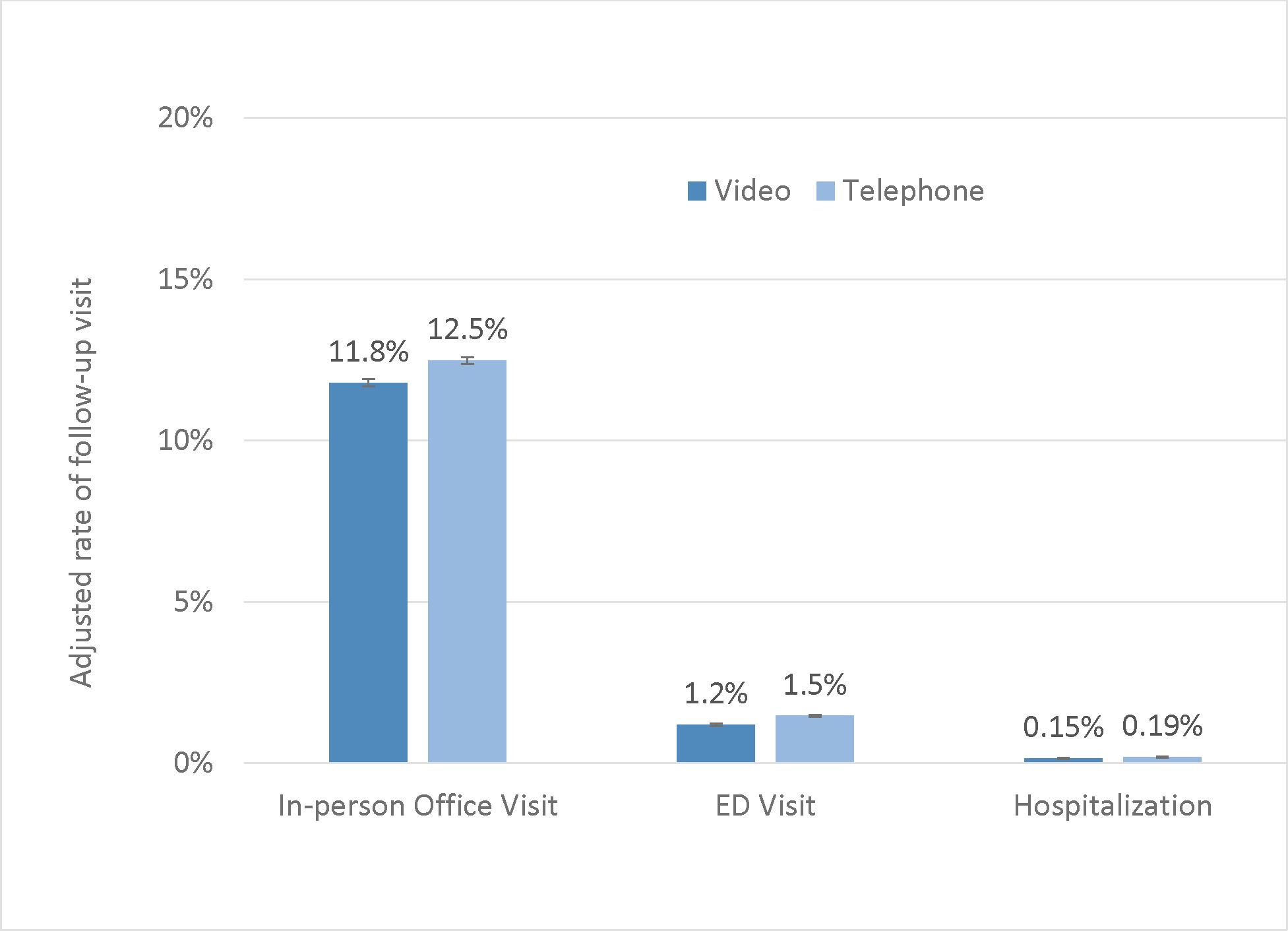

Figure 2 shows adjusted rate of 7-day follow-up care by telephone and video visits. Adjusted rate of follow-up in-person office visits was 11.8% after video visits and 12.5% after telephone visits, with a difference of 0.7% (95%CI: 0.5–0.9) lower after video than telephone visits. Adjusted rate of ED visits was 1.2% after video visits and 1.5% after telephone visits, with a difference of 0.3% (95% CI: 0.2–0.3) lower after video than telephone visits. Adjusted rate of hospitalizations was 0.15% after video visit and 0.19% after telephone visits, with a difference of 0.04% (95% CI: 0.02–0.06) lower after video than telephone visits. All the differences between telephone and video were statistically significant.

Figure 2. Adjusted rates of 7-day follow-up health care utilization by video and telephone visits.

Adjusted rates were calculated by using coefficients from multivariate logistic regression for each outcome adjusted for characteristics in table 1, ICD10 grouping, and medical center as if the entire cohort were having a video visit and as if the entire cohort were having a telephone visit respectively. ED=Emergency department.

Discussion

In a large integrated health care setting, during the early COVID-19 pandemic when telemedicine was the primary option for patient-initiated primary care appointments, more than half of patient-scheduled visits were telephone visits. As hypothesized, we found return visits were not common and downstream emergency events were rare. Adjusted rates of treatment were statistically significantly higher in video visits than telephone visits, and 7-day follow-up health care utilization was statistically significantly lower after video visits than telephone visits.

Despite increasing use and availability of video technology, telephone-based telemedicine care was commonly used by patients during this early pandemic period. This might be expected due to the lower barrier-to-entry for telephone visits. Even with access to video technology, some patients may prefer a telephone visit because they do not have to worry about making themselves or their houses presentable for the visit.

Adjusted rates of medication prescribing and lab/imaging orders were statistically significantly higher among video visits when compared with telephone visits, and adjusted rate of 7-day follow-up in-person office visits was slightly lower after video visits than telephone visits. These findings might also be expected because video visits can convey more visual information, offer a “face-to-face” connection, and support more interaction between patients and providers11. Also, some patients may use telephone visits as triage to determine if more care is needed. Another survey study also found higher rates of lab and imaging ordered during video visits and lower rates of follow-up in-office visit within 30 days of the video visit when compared with telephone visits among 269 patients who had tele-visits with urologists during the pandemic, but the results were not statistically significant12. While we found that adjusted rates of 7-day follow-up ED visits and hospitalizations were slightly higher after telephone when compared with video visits, it is reassuring that these events were rare. These findings were consistent with those from our previous study on the pre-pandemic period when in-person office was the most common primary care visit type13.

In our previous study conducted for the same study period on the association between patient characteristics and the telemedicine modality, we found patients’ choice of video versus telephone appointment varied by patient demographics and technology access14. For example, Black or Hispanic patients or patients living in neighborhoods with lower SES or lower internet access were less likely to choose video visits. Those with technology access, as measured by either prior video visit experience or mobile device portal access, were more likely to choose video visits14. Other studies also found that patients who are Black and living in a neighborhood with lower income were more likely to use telephone visits than video visits during the COVID-19 pandemic6,7,15. Given the digital divide in technology access to support video telemedicine, our findings here of low rates of downstream emergency events (ED visits and hospitalizations) for both video and telephone visit suggest telephone visits may offer a simple and convenient health care access option without raising significant safety concerns.

While in-person visits were historically the dominant type of health care visit, the pandemic created a natural experiment, in which the volume of telemedicine visits increased dramatically because patient care-seekers had to use telemedicine as a first line of contact with their primary care clinicians. Prior studies examined the patient characteristics between video and telephone visits6,7, but there is limited evidence on the differences in treatment and the downstream outcomes between them. To our best knowledge, this is the first large study assessing the efficiency and safety differences between telephone and video primary care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a large integrated health care setting where video and telephone telemedicine were already widely available long before the pandemic. The findings may not directly generalize to less-integrated telemedicine delivery settings. The population in the health system all have insurance coverage (including employer sponsored, Medicare, Medicaid, etc.), those without any insurance coverage may not be as well-represented in our data. Since this is an observational study, we cannot rule out unmeasured confounding factors, and results cannot be interpreted as causal. Nonetheless, we collected a wide range of covariates including patient, technology and clinical characteristics, and accounted for them in the analyses. Our study outcomes were constructed such that the orders we identified during the index visit and health care utilization was measured over a 7-day follow-up window. Not all visits may need medication or lab/image orders. These outcomes may not necessarily be directly related to the index visit (medication prescribing can be for refills of chronic medications, lab/imaging orders could be for future preventive tests, and visits within seven days could be related to new health problems). The findings from this study were based on all types of primary care visits with adjustment for primary diagnosis, but severity may differ by visit type (e.g., telephone vs. video visits) and the results may vary for specific clinical concerns (e.g., some clinical concerns may need visual information to assess the condition, and some may not).

Conclusion

In this observational cohort study during early COVID-19 pandemic, we found return visits were not common and emergency events were rare. Telephone visits were more widely used and resulted in modestly lower treatment rates and higher rates of follow-up health care utilization. Despite uncertainty in long term payment models, both video- and telephone-based virtual care options are likely to continue to offer patients important venues to access primary care clinicians even after the pandemic crisis. Video and telephone visits expand access to primary care services, and telephone visits may offer a simple and convenient option to address patient needs without raising safety concerns. Future study is needed to further examine the quality and safety of telemedicine stratified by visits with different clinical concerns.

Take-Away Points:

Among 734,442 patient-initiated primary care telemedicine visits in a large integrated delivery system during the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that return visits were not common and downstream emergency events were rare.

Adjusted rates of medication prescribing and lab/imaging orders were slightly higher in video visits than telephone visits.

Adjusted rates of 7-day follow-up office visits, emergency department visits and hospitalizations were nominally lower after video visits than telephone visits.

Video visits may be marginally more efficient than telephone visits, and telephone visits may offer a simple and convenient option to address patient primary care needs without raising safety concerns.

Funding Source:

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS25189).

Contributor Information

Jie Huang, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA.

Anjali Gopalan, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA.

Emilie Muelly, Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara, Santa Clara, CA.

Loretta Hsueh, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA.

Andrea Millman, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA.

Ilana Graetz, Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Mary Reed, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA.

References

- 1.Temesgen ZM, DeSimone DC, Mahmood M, Libertin CR, Varatharaj Palraj BR, Berbari EF. Health Care After the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Influence of Telemedicine. Mayo Clin Proc. Sep 2020;95(9S):S66–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New HHS Study Shows 63-Fold Increase in Medicare Telehealth Utilization During the Pandemic (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ) (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Telemedicine Health Provider Factsheet (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Year Calendar (CY) 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ) (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang JE, Lindenfeld Z, Albert SL, et al. Telephone vs. Video Visits During COVID-19: Safety-Net Provider Perspectives. J Am Board Fam Med. Nov-Dec 2021;34(6):1103–1114. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez JA, Betancourt JR, Sequist TD, Ganguli I. Differences in the use of telephone and video telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. Jan 2021;27(1):21–26. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2021.88573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. Dec 1 2020;3(12):e2031640. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoong EC, Butler BA, Mesina O, et al. Patient interest in and barriers to telemedicine video visits in a multilingual urban safety-net system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. Feb 15 2021;28(2):349–353. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon N Similarity of adult Kaiser Permanente Members to the adult population in Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California Service Area: Comparisons based on the 2017/2018 cycle of the California Health Interview Survey. 2020. 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Choosing a Telemedicine Visit vs Office Visit With the Same Primary Care Clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. Jun 1 2020;3(6):e205873. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammersley V, Donaghy E, Parker R, et al. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: a non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. Sep 2019;69(686):e595–e604. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen AZ, Zhu D, Shin C, Glassman DT, Abraham N, Watts KL. Patient Satisfaction with Telephone Versus Video-Televisits: A Cross-Sectional Survey of an Urban, Multiethnic Population. Urology. Oct 2021;156:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.05.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed M, Huang J, Graetz I, Muelly E, Millman A, Lee C. Treatment and Follow-up Care Associated With Patient-Scheduled Primary Care Telemedicine and In-Person Visits in a Large Integrated Health System. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 1 2021;4(11):e2132793. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Graetz I, Millman A, et al. Primary care telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: patient’s choice of video versus telephone visit. JAMIA Open. Apr 2022;5(1):ooac002. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schifeling CH, Shanbhag P, Johnson A, et al. Disparities in Video and Telephone Visits Among Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Analysis. JMIR Aging. Nov 10 2020;3(2):e23176. doi: 10.2196/23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]