Abstract

Rosmarinic acid was esterified with ethanol, butanol, and hexanol to produce ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate, respectively. The antioxidant capacities of the rosmarinic acid esters were evaluated in linseed oil, organogel, and emulsion gel during the initiation and propagation phases of peroxidation. Organogel control sample showed higher induction period and propagation period than those of linseed oil and emulsion gel control samples. Among linseed oil and organogel samples containing antioxidants, samples containing rosmarinic acid exhibited the highest antioxidant activity during the initiation phase, while rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate showed the highest antioxidant activity in the propagation phase. In emulsion gel, rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate showed higher antioxidant activity than those of rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate or hexyl rosmarinate in the initiation and propagation phases. In addition, the investigated antioxidants showed lower efficiency in organogel and emulsion gel samples than those in linseed oil samples.

Keywords: Emulsion gel, Organogel, Oxidation kinetic, Rosmarinic acid esters

Highlights

-

•

Antioxidant potency of rosmarinic acid esters were investigated in organogel and emulsion gel.

-

•

Rosmarinic acid showed the best antioxidant activity in linseed oil and organogel.

-

•

In emulsion gel, butyl rosmarinate exhibited the best antioxidant activity.

-

•

Antioxidants showed higher efficiency in linseed oil than those of organogel and emulsion gel.

1. Introduction

In recent years, structuring liquid oils into solid lipids without saturated and trans fats has gained increased attention due to the advantages for human health and promises potential as new systems for delivering hydrophobic bioactive compounds. Formation of organogel and emulsion gel are two common methods for structuring liquid oils into solid lipids (Chen et al., 2016). Organogel is produced by adding low molecular weight gelators (e.g., hydroxylated fatty acids, lecithin, and waxes) or high molecular weight gelators (e.g. ethyl cellulose) to the liquid oil (Giacintucci et al., 2018). Emulsion gel is produced by adding cross linker agents such as proteins (e.g. gelatin, whey protein isolate, and soybean protein isolate) (Zhang, Zhang, Zhong, Qi, & Li, 2022) and polysaccharides (e.g. k-carrageenan and alginate) to the oil-in-water emulsion (Li et al., 2022). Although using organogels and emulsion gels instead of solid fats is a feasible strategy to reduce the amount of trans and saturated fatty acids in food products, but the presence of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the organogel and emulsion gel makes these systems prone to lipid oxidation (Pan et al., 2021).

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) is a medicinal plant widely used in foods. Phenolic acids (rosmarinic acid) and phenolic diterpenes (rosmanol, carnosic acid, and carnosol) are the major phenolic compounds present in rosemary. These compounds possess significant antioxidant and antimicrobial activities (Klančnik, Guzej, Kolar, Abramovič, & Možina, 2009).

Lipid oxidation in bulk oil and oil dispersions is an interfacial phenomenon. In bulk oil, surface-active compounds (e.g. phospholipids, free fatty acids, sterols, monoacylglycerols, and diacylglycerols) can produce reverse micelles in the presence of water. Hydroperoxides produced during peroxidation process usually accumulate at the interfacial area of reverse micelles. Metal ions decompose lipid hydroperoxides into free radicals. In the case of oil dispersions, peroxidation process takes place at the surface of oil droplets where polyunsaturated fatty acids in the oil phase react with metal ions in the aqueous phase. Phenolic compounds which can locate at the interfacial area of reverse micelles in bulk oil and oil-water interface in oil dispersions can inhibit peroxidation efficiently. Modification of phenolic compounds by esterification with fatty acids or fatty alcohols can use as a promising method for changing their hydrophobicity and, as a consequence, their accumulation at the interfacial area (Keramat, Golmakani, & Toorani, 2021; Laguerre et al., 2015). Alkyl chain length and concentration of phenolic compound ester (Phonsatta et al., 2017; Zhong & Shahidi, 2012), interaction of phenolic compound ester with other food compounds (Qiu, Jacobsen, Villeneuve, Durand, & Sørensen, 2017), and physicochemical properties of lipid system (Keramat, Golmakani, Niakousari, & Toorani, 2023) can affect the antioxidant activity of phenolic compound ester.

In this work, rosmarinic acid in rosemary extract was esterified with alcohols with different alkyl chain length (ethanol, butanol, and hexanol) to produce rosmarinic acid esters with different hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB). Then, the antioxidant capacities of rosmarinic acid esters in linseed oil were compared with those of organogel and emulsion gel. This is the first report on investigating how particular lipid systems can impact the antioxidant properties of rosmarinic acid esters. Also, antioxidant capacity of rosmarinic acid esters was investigated during the initiation and propagation phase of peroxidation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Dried rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) and linseed oil were purchased from a local market. Ethanol (> 99%) was purchased from Zakaria Jahrom Company (Jahrom, Iran). Ammonium thiocyanate (> 97.5%), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH°), Amberlyst 15 dry, ferrous chloride, and barium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company (St. Louis, MO). n- Butanol (> 99%) and n-hexanol (> 99%), chloroform, and hydrochloric acid were purchased from Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany). Methanol was purchased from Mojallali Company (Tehran, Iran).

2.2. Extraction of rosemary extract

Extraction of rosemary extract was done by a microwave extractor (MR249, Kian Tajhiz GD, Shiraz, Iran). Rosemary powder (10 g) was mixed with ethanol (150 mL) in a 250 mL flat bottom flask. The flask was placed in the microwave oven. A condenser was placed on top of the flask. After 15 min irradiation at 200 W, the extract was filtered and ethanol was eliminated under vacuum by a rotary evaporator (T63AL model, Buchi Company, Switzerland) at 40 °C (Golmakani, Moosavi-Nasab, Keramat, & Mohammadi, 2018).

2.3. Esterification of rosmarinic acid

Dried rosemary extract (1 g) was mixed separately with 10 g of ethanol, n-butanol, and n-hexanol. Then, Amberlyst 15 dry was added to the reaction mixtures at 4% (w/w). After that, the mixtures were stirred by a hot plate magnetic stirrer (RH basic 2, IKA Company, Germany) at 60 °C for 6 h. The extra amounts of alcohols were eliminated under vacuum by a rotary evaporator (T63AL model, Buchi Company, Switzerland) at 40 °C.

2.4. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS)

LC/MS was done to confirm the esterification of rosmarinic acid. LC/MS was done by a HPLC system (Alliance 2695, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) equiped with a mass spectrometer (Quattro Premier XE, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The LC/MS apparatus was equipped with an Atlantis T3-C18 column (3 μm; 150 mm × 2.1 mm i.d.; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). A mixture of acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid):water (containing 0.1% formic acid) (50:50, v/v) was used as the mobile phase. The injection volume, the flow rate, and the column temperature were 5 μL, 0.2 mL/min, and 35 °C, respectively. Mass spectrum was recorded in negative electrospray ionization mode. The compounds present in modified and unmodified extracts were determined via comparison of their mass spectral fragmentation patterns with those of pure standards or mass spectral data exist in the literature (Hossain, Rai, Brunton, Martin-Diana, & Barry-Ryan, 2010; Lee et al., 2013; Mena et al., 2016). Rosmarinic acid, and its ethyl, butyl, and hexyl esters were quantified with regard to the pure rosmarinic acid standard.

2.5. Radical scavenging and reducing capacities

Radical scavenging capacity of rosemary extract containing rosmarinic acid (R), rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate (ER), rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate (BR), and rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate (HR) was determined following the method described by Keramat, Golmakani, Aminlari, and Shekarforoush (2016). Ethanolic solutions of R, ER, BR, and HR samples were prepared at concentrations of 100, 10, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 mg/mL. Then, 400 μL of each sample solutions were mixed with 3600 μL ethanolic DPPH solution (60 μM) and kept at room temperature in the dark. After 60 min, the absorbance values of the samples were determined at 517 nm by a spectrophotometer (VIS-7220G/UV-9200, Beijing Beifen-Ruili, China). The IC50 value is the antioxidant concentration needed for scavenging 50% of the DPPH•. This parameter was determined from the regression analysis of the remained DPPH• versus the antioxidant concentration.

The reducing capacities of R, ER, BR, and HR samples were determined by reducing the copper (II) to copper (I). In brief, methanolic Neocuproine solution (1000 μL, 7500 μmol L−1) was blended with copper (II) chloride aqueous solution (1000 μL, 10,000 μmol L−1), and ammonium acetate aqueous solution (1000 μL, 106 μmol L−1). Then, distilled water (600 μL) and R, ER, BR, or HR ethanolic solutions (500 μL, 100 mg L−1) were separately added to the mixture. After 30 min, the absorbance values of samples were measured at 450 nm against the blank (containing all the reagents without sample) (Keramat et al., 2016). .

2.6. Preparation of organogel and emulsion gel samples

R, ER, BR, and HR were solubilized in acetone. Then, they were separately incorporated into linseed oil at 200, 400, and 600 mg kg−1. For preparation of organogel samples, 0.36 g of monoglyceride was mixed with 3 g of linseed oil containing R, ER, BR, and HR and heated at 80 °C for 5 min, while blending by magnetic stirrer (RH basic 2, IKA Company, Germany). Then, the organogel samples were kept at refrigerator for 1 day (Yılmaz & Öğütcü, 2014). For preparation of emulsion gel, oil-in-water emulsion was prepared using the method described by Ostertag, Weiss, and McClements (2012). The oil:water and the Tween 80:oil ratios were 1:10 and 1:2.5, respectively. Linseed oil containing R, ER, BR, or HR were blended with Tween 80 and stirred for 30 min. Then, potassium phosphate buffer solution (0.01 mmol/L, pH 7) was added into the linseed oil at the 0.5 mL/min rate. The potassium phosphate buffer contained potassium chloride (1.2%, w/w). The oil-in-water emulsion was heated at 80 °C for 5 min. Then, kappa-carrageenan (2%, w/w) was incorporated into the oil-in-water emulsion. Finally, the oil-in-water emulsion was stirred at 80 °C for 15 min. The produced emulsion gels were stored at refrigerator for 24 h (Kamlow, Spyropoulos, & Mills, 2021).

2.7. Rheological properties of organogel and emulsion gel

The rheological properties of organogel and emulsion gel were determined by a MCR 302 rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria). Plate diameter and gap size of applied parallel plate geometry were 40 mm and 1 mm, respectively. The linear viscoelastic region was determined by amplitude sweep test. In this test, the shear strain range was varied between 0.001% to 100% and frequency was kept constant at 6.28 rad/s. In the case of frequency sweep test, the frequency was varied between 0.06 and 99.60 rad/s and strain was kept constant at 0.01%. The rheological assays were determined at 25 °C.

2.8. Kinetic study

Linseed oil, organogel, and emulsion gel samples were kept at 35 °C. The concentrations of hydroperoxides (LOOH) were determined at certain time intervals. To extract oil from emulsion gel, chloroform:methanol (1.5 mL, 1:1, v/v) was mixed with emulsion gel (0.3 g). After vortexing for 1 min, the mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 1300 ×g. The lower lipid layer was collected and its solvent evaporated using nitrogen stream (Asnaashari, Farhoosh, & Sharif, 2014). To measure LOOH concentration, 9.8 mL chloroform:methanol mixture (9.8 mL, 7:3, v/v) was blended with the oil sample (0.001–0.3 g). Then, the sample was vortexed for 2–4 s. After that, aqueous solution of ammonium thiocyanate (0.05 mL, 30%, w/v) was mixed with ferrous chloride solution (0.05 mL). The sample was kept at room temperature for 5 min. Then, the absorption value of the sample was measured at 500 nm against a blank (containing all the reagents without the sample) by a spectrophotometer (VIS-7220G/UV-9200, Beijing Beifen-Ruili, China). Lipid hydroperoxide concentration (mM) was determined by cumene hydroperoxide standard curve. To prepare ferrous chloride solution, aqueous solution of FeSO4.7H2O (25 mL, 1%, w/v) was mixed with barium chloride aqueous solution (25 mL, 0.8%, w/v). Then, hydrochloric acid (1 mL, 10 N) was added to the mixture. Finally, the solution was filtered to eliminate barium sulphate deposits (Shantha & Decker, 1994).

The LOOH concentrations (mM) of samples were plotted against time (t, h). The oxidation reaction obeys a pseudo-zero order kinetic in the initiation phase. The rate constant (ri, mM h−1) was measured via Eq. (1) (Farhoosh, 2018).

| (1) |

To describe the kinetic curves of LOOH production during the initiation and propagation phases, a sigmoidal model was considered. The LOOH concentration during the whole range of oxidation was calculated using Eq. (2) (Farhoosh, 2018).

| (2) |

where C (mM−1) is an integration constant, rf (h−1) is a pseudo-first order rate constant of LOOH production, and rd (mM−1 h−1) is a pseudo-second order rate constant of LOOH decomposition during the propagation phase.

Induction time (IT, h) was calculated by Eq. (3).

| (3) |

The oxidation rate ratio during the initiation phase (ORi) was determined by Eq. (4).

| (4) |

where ri, B is the ri value of the sample without modified or unmodified rosemary extract and ri, A is the ri value of the sample containing modified or unmodified rosemary extract.

The effectiveness (Ei) of modified or unmodified rosemary extract in the initiation phase was determined by Eq. (5).

| (5) |

where ITA is the IT of the sample containing modified or unmodified rosemary extract and ITB is the IT of the samples without modified or unmodified rosemary extract.

Activity (A) was determined by Eq. (6) (Farhoosh, 2022).

| (6) |

The highest concentration of LOOH (LOOHm, mM) was determined by Eq. (7).

| (7) |

The turning point (TP) which is the time when the rate of LOOH production reaches its highest value was calculated by Eq. (8).

| (8) |

The highest rate of LOOH formation in the propagation phase (Km, mM h−1) was calculated by Eq. (9).

| (9) |

The oxidizability in the propagation phase (kn,h−1) was determined by Eq. (10).

| (10) |

The end time of the propagation phase (ET, h) was calculated by Eq. (11).

| (11) |

The duration of propagation period (PT, h) was calculated by Eq. (12) (Farhoosh, 2021).

| (12) |

2.9. Statistical analysis

All assays were done in triplicate. Significant differences among the mean values were determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparing the mean values were performed by Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05). The regression analysis was done by CurveExpert 2.7.3 and Microsoft Office Excel 16.0 software. The statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 16 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. LC/MS

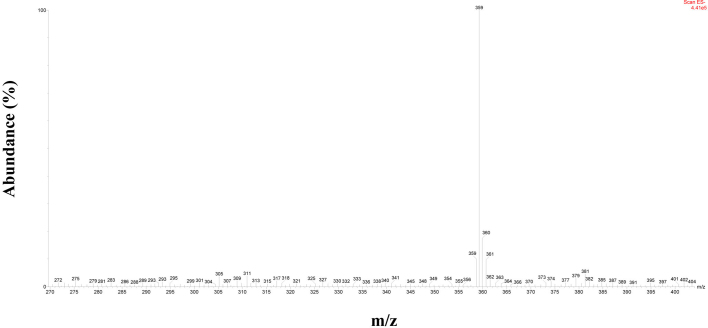

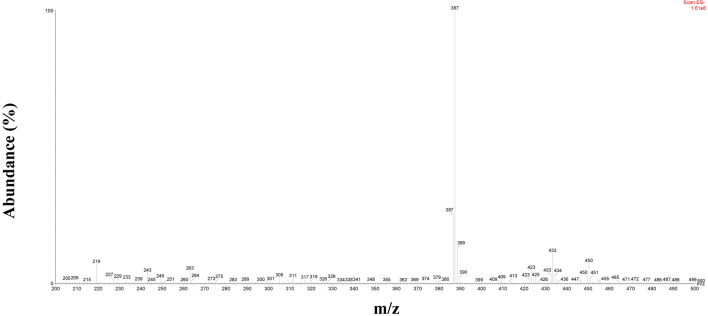

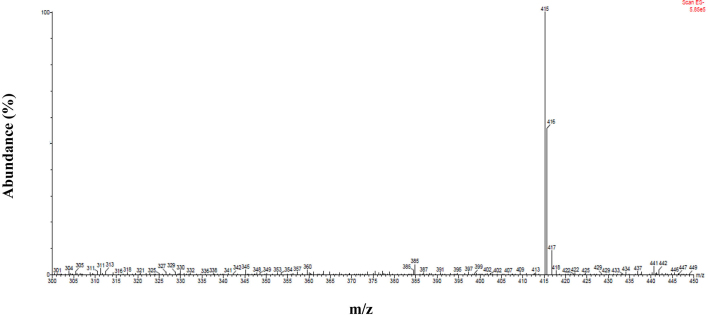

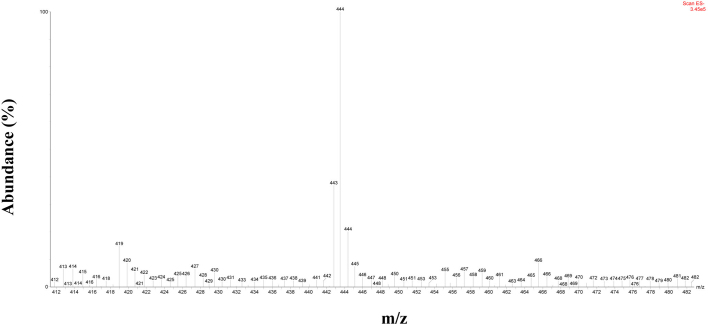

Phenolic compounds identified in R, ER, BR, and HR by LC/MS are presented in Table 1. Phenolic acids (rosmarinic acid) and phenolic diterpenes (carnosic acid, carnosol, and rosmanol) were the major compounds present in R sample. Rosmarinic acid, Ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate molecular ions were located at 359, 387, 415, and 444 m/z, respectively (Fig. 1S–4S). Ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate peaks were identified at retention times of 5.27, 8.18, and 11.66 min, respectively (Table 1). Also, quantitative determinations of ER, BR, and HR chromatograms showed that 93.93%, 96.29%, and 92.06% of rosmarinic acid were converted to ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate, respectively. In addition, comparing the R chromatogram with those of ER, BR, and HR showed that phenolic diterpenes (carnosic acid, carnosol, and rosmanol) were remained unchanged in ER, BR, and HR chromatograms.

Table 1.

Phenolic compounds identified in modified and unmodified rosemary extracts.⁎

| No. | Compound | Retention time (min) | [M-H]− (m/z) | Molecular weight (g mol−1) | Molecular formula | Identification mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | ||||||

| 1 | Rosmarinic acid | 3.17 | 359 | 360.32 | C18H16O8 | Standard |

| 2 | Rosmanol | 8.85 | 345 | 346.42 | C20H26O5 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 3 | Carnosol | 10.50 | 329 | 330.42 | C20H26O4 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 4 | Carnosic acid | 13.11 | 331 | 332.42 | C20H28O4 | (Vallverdú-Queralt et al., 2014) |

| ER | ||||||

| 1 | Rosmarinic acid | 3.17 | 359 | 360.32 | C18H16O8 | Standard |

| 2 | Ethyl rosmarinate | 5.27 | 387 | 388.39 | C24H12O8 | (Lee et al., 2013; Panya et al., 2010) |

| 3 | Rosmanol | 9.37 | 345 | 346.42 | C20H26O5 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 4 | Carnosol | 14.24 | 329 | 330.42 | C20H26O4 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Carnosic acid | 16.54 | 331 | 332.42 | C20H28O4 | (Vallverdú-Queralt et al., 2014) |

| BR | ||||||

| 1 | Rosmarinic acid | 3.10 | 359 | 360.32 | C18H16O8 | Standard |

| 2 | Butyl rosmarinate | 8.18 | 415 | 416.44 | C22H8O8 | (Lee et al., 2013; Panya et al., 2012) |

| 3 | Rosmanol | 9.11 | 345 | 346.42 | C20H26O5 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 4 | Carnosol | 11.37 | 329 | 330.42 | C20H26O4 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Carnosic acid | 13.14 | 331 | 332.42 | C20H28O4 | (Vallverdú-Queralt et al., 2014) |

| HR | ||||||

| 1 | Rosmarinic acid | 3.22 | 359 | 360.32 | C18H16O8 | Standard |

| 2 | Rosmanol | 9.27 | 345 | 346.42 | C20H26O5 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 3 | Hexyl rosmarinate | 11.66 | 444 | 445.09 | C24H28O8 | (Laguerre et al., 2010; Sherratt, Villeneuve, Durand, & Mason, 2019) |

| 4 | Carnosol | 14.17 | 329 | 330.42 | C20H26O4 | (Mena et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Carnosic acid | 16.34 | 331 | 332.42 | C20H28O4 | (Vallverdú-Queralt et al., 2014) |

R: rosemary extract, ER: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate, BR: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate, and HR: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate.

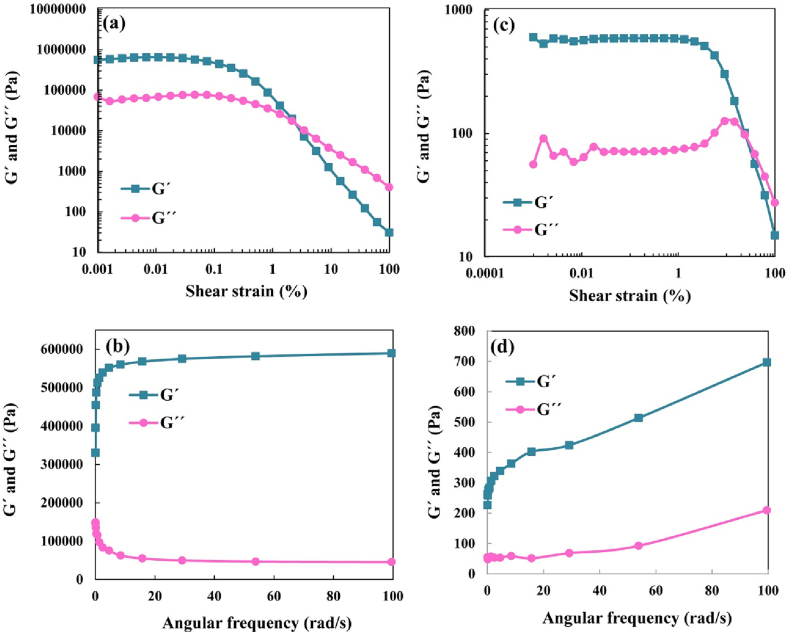

Fig. 1.

Amplitude (a, c) and frequency sweep (b, d) curves of organogel (a, b) and emulsion gel (c, d) samples.

3.2. Radical scavenging and reducing capacities

In DPPH assay, the IC50 values of R, RE, RB, and RH samples were 62.25 ± 6.69, 75.51 ± 3.55, 58.07 ± 3.06, and 59.37 ± 3.04 μg mL−1, respectively. The reducing capacities of R, RE, RB, and RH samples were 0.49 ± 0.07, 0.50 ± 0.05, 1.17 ± 0.10, and 0.79 ± 0.24 mg ascorbic acid equivalent per mg sample, respectively. Accordingly, RB exhibited the highest radical scavenging and reducing capacity.

3.3. Rheological evaluation

The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) of the organogel and emulsion gel are shown in Fig. 1. In the amplitude (strain) sweep test, both organogel and emulsion gel samples showed higher G′ values than those of G″ values within the linear viscoelastic region. Therefore, organogel and emulsion gel samples exhibited elastic behavior rather than viscose behavior. In the organogel, the G′′ value was higher than G′ value at high shear strains (> 2%). In emulsion gel samples, the G′′ was higher than G′ value at shear strains higher than 23%. In the frequency sweep test, both organogel and emulsion gel showed elastic behavior (G′ > G′′) within the examined frequency range.

3.4. Oxidation kinetic parameters of organogel and emulsion gel samples during the initiation phase

Effects of R, ER, BR, and HR samples on the initiation phase kinetic parameters are shown in Table 2. Linseed oil control sample showed higher ri value and lower IT value than that of organogel control sample. An important factor that can affect lipid oxidation is the transfer rate of pro-oxidant compounds toward unsaturated triacylglycerols (Laguerre, Bily, Roller, & Birtić, 2017). In organogel structure, the oxygen diffusion rate is slower than that of bulk oil (Frolova, Sobolev, Sarkisyan, & Kochetkova, 2021). Also, it has been reported that the lower oxidation rate of organogels produced by soy lecithin is due to entrapment of metal ions in the reverse micelles of soy lecithin (Zhuang, Gaudino, Clark, & Acevedo, 2021). Therefore, the higher oxidative stability of organogel control sample can be due to the lower transfer rate of metal ions and oxygen in organogel structure. The ORi parameter is the ratio of ri value of samples containing antioxidants and the ri value of the sample without antioxidant. The Ei parameter is the ratio of IT value of samples containing antioxidants and to IT value of sample without antioxidant. The A value combines ORi value and Ei value (Toorani & Golmakani, 2022). In both linseed oil and organogel samples containing antioxidants, the R sample (600 mg kg−1) exhibited the highest A value. Accordingly, rosmarinic acid showed higher efficiency than rosmarinic acid esters in reducing linseed oil and organogel oxidation. The location of an antioxidant can significantly affect its efficiency in lipid systems. Recent studies have stated that in bulk oil, surface-active compounds (sterols, free fatty acids phospholipids, hydroperoxides, monoacylglycerols, and diacylglycerols) and water can create reverse micelles. LOOH formed during auto-oxidation tend to accumulate at the interfacial region of the reverse micelles. Polar antioxidants have higher tendency than less polar antioxidants for accumulating at the oil-water interface of the reverse micelles (Laguerre et al., 2015). The log P value determines how polar a compound is. This parameter enhances by decreasing polarity (Lalitha & Sivakamasundari, 2010). The log P values of rosmarinic acid, ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate were 1.83, 2.82, 3.88, and 4.90, respectively. Therefore, rosmarinic acid is more polar than ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate. Hence, it seems that rosmarinic acid have higher tendency than ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate for accumulating at the interfacial region of the reverse micelles and retards auto-oxidation more efficiently than ethyl rosmarinate, butyl rosmarinate, and hexyl rosmarinate.

Table 2.

Oxidation kinetic parameters of linseed oil as well as organogel and emulsion gel samples in the initiation phase.

| Kinetic parameter | ri × 103 (mM h−1) | IT (h) | ORi⁎10 | Ei | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linseed oil | |||||

| Control | 24.45 ± 0.49a | 214.62 ± 8.29g | – | – | – |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 14.30 ± 0.00b | 496.67 ± 4.21cd | 5.85 ± 0.12a | 2.32 ± 0.56cd | 3.98 ± 0.01d |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 8.90 ± 0.14cd | 776.49 ± 30.21b | 3.64 ± 0.13bci | 3.61 ± 0.24b | 9.92 ± 0.31d |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 1.25 ± 0.07h | 1091.47 ± 12.12a | 0.51 ± 0.04f | 5.09 ± 0.25a | 99.98 ± 0.74a |

| ER (200 mg kg−1) | 13.80 ± 0.71b | 536.03 ± 11.62c | 5.65 ± 0.40a | 2.50 ± 0.34c | 4.47 ± 0.92d |

| ER (400 mg kg−1) | 6.00 ± 0.08ef | 551.74 ± 10.08c | 2.45 ± 0.05d | 2.57 ± 0.22c | 10.45 ± 0.67d |

| ER (600 mg kg−1) | 1.60 ± 0.03gh | 732.58 ± 9.28b | 0.65 ± 0.01ef | 3.43 ± 0.61b | 52.44 ± 1.03b |

| BR (200 mg kg−1) | 9.20 ± 1.98c | 290.26 ± 10.08ef | 3.76 ± 0.73b | 1.36 ± 0.17e | 3.63 ± 0.26d |

| BR (400 mg kg−1) | 10.10 ± 1.27c | 732.74 ± 33.13b | 4.14 ± 0.60b | 3.41 ± 0.02c | 8.34 ± 1.16d |

| BR (600 mg kg−1) | 3.15 ± 0.50g | 762.52 ± 9.81b | 1.29 ± 0.23e | 3.56 ± 0.18b | 28.12 ± 2.40c |

| HR (200 mg kg−1) | 3.10 ± 0.85g | 291.84 ± 0.27ef | 1.26 ± 0.32e | 1.36 ± 0.05e | 11.07 ± 2.41d |

| HR (400 mg kg−1) | 7.30 ± 0.09de | 372.34 ± 9.53de | 2.99 ± 0.06cd | 1.74 ± 0.19de | 5.83 ± 0.76d |

| HR (600 mg kg−1) | 5.50 ± 0.73f | 407.74 ± 10.90de | 2.25 ± 0.05d | 1.91 ± 0.36cde | 8.50 ± 1.79d |

| Organogel | |||||

| Control | 10.25 ± 0.07a | 299.59 ± 0.51e | – | – | – |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 4.90 ± 0.14d | 732.53 ± 25.85bcd | 5.78 ± 0.10d | 2.44 ± 0.08abcd | 5.11 ± 0.06c |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 5.95 ± 0.92cd | 750.15 ± 26.05abcd | 5.81 ± 0.94cd | 2.50 ± 0.09abcd | 4.36 ± 0.55c |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 1.40 ± 0.00e | 714.49 ± 18.66bcd | 1.37 ± 0.01e | 2.38 ± 0.07bcd | 17.46 ± 0.36a |

| ER (200 mg kg−1) | 7.60 ± 0.60b | 436.63 ± 4.51e | 7.41 ± 0.05b | 1.46 ± 0.01e | 1.97 ± 0.03c |

| ER (400 mg kg−1) | 9.80 ± 0.13a | 630.17 ± 17.63d | 9.56 ± 0.07a | 2.10 ± 0.06d | 2.20 ± 0.07c |

| ER (600 mg kg−1) | 10.50 ± 1.13a | 779.38 ± 0.35abcd | 10.25 ± 1.17a | 2.60 ± 0.82abcd | 2.60 ± 0.23c |

| BR (200 mg kg−1) | 1.90 ± 0.42e | 846.85 ± 2.73abc | 1.86 ± 0.43e | 2.83 ± 0.00abc | 15.65 ± 3.62ab |

| BR (400 mg kg−1) | 2.55 ± 1.06e | 896.45 ± 3.99ab | 2.49 ± 0.42e | 2.99 ± 0.17ab | 13.02 ± 2.10b |

| BR (600 mg kg−1) | 2.60 ± 0.00ghi | 937.63 ± 24.97a | 2.54 ± 0.02e | 3.13 ± 0.08a | 12.34 ± 0.39b |

| HR (200 mg kg−1) | 6.90 ± 0.98bc | 733.66 ± 4.29bcd | 6.74 ± 0.05bc | 2.45 ± 0.44abcd | 3.64 ± 0.68c |

| HR (400 mg kg−1) | 6.70 ± 0.53bc | 678.46 ± 20.85cd | 6.54 ± 0.04bc | 2.26 ± 0.27cd | 3.46 ± 0.38c |

| HR (600 mg kg−1) | 5.70 ± 0.85cd | 885.30 ± 34.36ab | 5.56 ± 0.79cd | 2.95 ± 0.11abc | 5.36 ± 0.56c |

| Emulsion gel | |||||

| Control | 76.50 ± 1.46bc | 91.20 ± 3.49e | – | – | – |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 67.10 ± 2.04bcd | 154.97 ± 5.89e | 8.96 ± 2.81bc | 1.69 ± 0.09f | 2.01 ± 0.73b |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 40.25 ± 4.03ef | 375.44 ± 4.92b | 5.27 ± 0.19def | 4.13 ± 0.87c | 7.81 ± 1.36b |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 21.15 ± 2.83g | 532.26 ± 2.78a | 2.93 ± 0.59f | 5.81 ± 1.34ab | 32.53 ± 2.52a |

| ER (200 mg kg−1) | 53.15 ± 0.49de | 198.83 ± 0.33cd | 7.01 ± 0.89bcd | 2.18 ± 0.09def | 3.13 ± 0.28b |

| ER (400 mg kg−1) | 65.85 ± 0.49bcd | 161.59 ± 5.66cd | 8.68 ± 1.12bc | 1.77 ± 0.07ef | 2.06 ± 0.35b |

| ER (600 mg kg−1) | 47.70 ± 0.93e | 212.95 ± 6.64cd | 6.29 ± 0.86bcde | 2.34 ± 0.28def | 3.72 ± 0.06b |

| BR (200 mg kg−1) | 62.70 ± 1.56cd | 298.50 ± 3.04bc | 8.26 ± 0.93bc | 3.25 ± 0.42cde | 4.04 ± 0.84b |

| BR (400 mg kg−1) | 71.00 ± 4.52bc | 298.56 ± 9.71bc | 9.33 ± 0.68abc | 3.28 ± 0.33cd | 3.51 ± 0.10b |

| BR (600 mg kg−1) | 31.20 ± 3.31fg | 410.05 ± 8.96ab | 4.12 ± 0.56ef | 4.50 ± 0.07bc | 11.02 ± 1.33b |

| HR (200 mg kg−1) | 78.50 ± 0.85b | 152.32 ± 3.71e | 10.36 ± 1.42ab | 1.66 ± 0.52f | 1.65 ± 0.07b |

| HR (400 mg kg−1) | 46.00 ± 0.71e | 216.92 ± 0.04cd | 6.08 ± 0.92cdef | 2.38 ± 0.09def | 3.95 ± 0.45b |

| HR (600 mg kg−1) | 94.70 ± 0.85a | 541.66 ± 20.08a | 12.50 ± 1.71a | 5.94 ± 0.01a | 4.80 ± 0.65b |

Mean ± SD (n = 3). In each section of each column, means with different superscript letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). R: rosemary extract containing rosmarininc acid, ER: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate, BR: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate, and HR: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate. ri: pseudo-zero order rate constant at the initiation stage, IT: induction period, ri: pseudo-zero order rate constant in the initiation stage, ORi: oxidation rate ratio during the initiation phase, Ei: antioxidant effectiveness during the initiation phase, and A: activity.

The ri value of emulsion gel control sample was significantly higher than those of linseed oil and organogel samples. Also, the IT value of the emulsion gel control sample was significantly lower than those of linseed oil and organogel control samples. This result can be related to the existence of an oil-water interface in emulsion gel, which can enhance the reaction between metal ions in the water phase with unsaturated triacylglycerols in the oil phase (Berton-Carabin, Ropers, & Genot, 2014). In emulsion gel, BR samples at all investigated concentrations showed higher A values than those of ER and HR samples. Therefore, the relationship between A value and chain length of rosmarininc acid esters was in agreement with the cut-off effect theory. Based on this theory, in lipid dispersions, the antioxidant activities of antioxidant esters increase by increasing chain length up to a certain point. By further increasing the chain length, the antioxidant efficiency decreases. The cut-off effect theory states that below a certain chain lenght, the antioxidants are far from oil-water interface. The reduction in antioxidant efficiency beyond a certain chain length can be described by “reduced mobility”, “internalization”, and “self-aggregation” theories. Based on the “reduced mobility” theory, the ability of antioxidant ester to move toward oil-water interface decreases by increasing chain length above a certain point. The internalization theory states that antioxidant esters with long alkyl chain length have higher affinity for locating at the core of the oil droplets than locating at the oil-water interface. Based on the “self-aggregation” theory, antioxidant esters with high alkyl chain length can form micelles in the water phase (Decker et al., 2017). Based on these theories, the higher A value of BR emulsion gel sample than those of ER and HR emulsion gel samples can be attributed to the higher tendency of butyl rosmarinate in BR emulsion gel sample than those of ethyl rosmarinate in ER emulsion gel sample and hexyl rosmarinate in HR emulsion gel sample for accumulating at the oil-water interface.

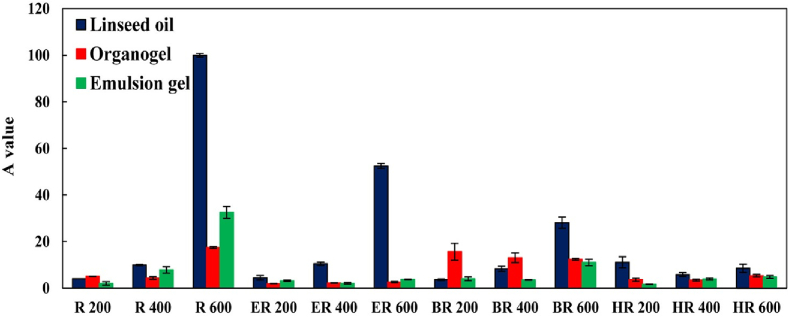

The organogel samples containing R, ER, and HR showed lower A values than those of linseed oil samples. In addition, the emulsion gel samples containing R, ER, BR, and HR showed lower A values than those of linseed oil samples (Fig. 2). An important factor that can affect the antioxidant efficiency in lipid systems is the ability of antioxidants to move toward peroxyl radicals (Laguerre et al., 2017). For instance, when antioxidants scavenged a peroxyl radical and eliminated from interfacial region, the ability of antioxidants to be replenished by antioxidant molecules from other regions can impact their antioxidant efficiency (Costa, Losada-Barreiro, Paiva-Martins, & Bravo-Diaz, 2021). In systems with gel like structures, the mobility of antioxidant molecules is limited (Frolova et al., 2021; Keramat et al., 2023). Therefore, in organogel and emulsion gel, when antioxidant molecules scavenge peroxyl radicals, they cannot be replaced immediately by antioxidants located in other regions. This phenomenon can reduce the antioxidant efficiency in organogel and emulsion gel structures.

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant activity (A) value of Linseed oil, organogel, and emulsion gel samples. R 200: rosemary extract containing rosmarininc acid (200 mg kg−1), R 400: rosemary extract containing rosmarininc acid (400 mg kg−1), R 600: rosemary extract containing rosmarininc acid (600 mg kg−1), ER 200: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate (200 mg kg−1), ER 400: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate (400 mg kg−1), ER 600: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate (600 mg kg−1), BR 200: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate (200 mg kg−1), BR 400: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate (400 mg kg−1), BR 600: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate (600 mg kg−1), HR 200: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate (200 mg kg−1), HR 400: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate (400 mg kg−1), and HR 600: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate (600 mg kg−1).

3.5. Oxidation kinetic parameters of organogel and emulsion gel samples during the propagation phase

Effects of R, ER, BR, and HR samples on the propagation phase kinetic parameters are shown in Table 3. The Kn value is a symbol of propagation oxidizability (Farhoosh, 2021). The Tp value is the time when the LOOH formation rate reaches its highest value (Farhoosh, 2021). The higher value of this parameter shows higher oxidative stability during the propagation phase. The Tp values of linseed oil, organogel, and emulsion gel samples were 279.94 ± 0.28, 913.14 ± 0.50, and 287.61 ± 9.28, respectively. Therefore, organogel control sample exhibited higher oxidative stability than those of linseed oil and emulsion gel samples. In both linseed oil and organogel samples, RB (600 mg kg−1) showed the highest Tp, PT, and ET values during the propagation phase, while R (600 mg kg−1) showed the highest IT values during the initiation phase. As stated in section 3.4, rosmarinic acid has higher affinity than rosmarinic acid esters for accumulating at interfacial region of the reverse micelles (actual site of lipid oxidation). Therefore, in the initiation phase, it is expected that the reaction rate of rosmarinic acid with peroxyl radicals were higher than that of butyl rosmarinate. Accordingly, a high fraction of rosmarinic acid molecules was consumed during the initiation phase and low concentrations of rosmarinic acid molecules were remained active in the propagation phase. However, in RB samples, butyl rosmarinate were far from the oil-water interface of the reverse micelles and consumed gradually in the initiation phase. Therefore, a higher fraction of butyl rosmarinate in RB samples were remained active in the propagation phase. This may result in higher oxidative stability of linseed oil and organogel samples containing RB than those samples containing R in the propagation phase of peroxidation.

Table 3.

Oxidation kinetic parameters of the propagation phase of linseed oil as well as organogel and emulsion gel samples.⁎

| Kinetic parameter | rf × 103 (h−1) | rd × 105 (mM−1 h−1) | Tp (h) | Kn × 103 (h−1) | PT (h) | ET (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linseed oil | ||||||

| Control | 1.60 ± 0.01b | 5.50 ± 0.00b | 279.94 ± 0.28i | 0.40 ± 0.01b | 1315.32 ± 8.29f | 1529.94 ± 0.03i |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 1.00 ± 0.06b | 3.90 ± 0.14c | 547.01 ± 1.60h | 0.25 ± 0.01b | 2050.34 ± 11.15e | 2547.01 ± 11.61h |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 4.85 ± 0.01a | 4.50 ± 0.08bc | 1095.63 ± 2.05cd | 1.21 ± 0.30a | 744.58 ± 3.60g | 1521.06 ± 28.07i |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 5.50 ± 0.07a | 7.00 ± 0.03a | 1384.45 ± 15.85f | 1.38 ± 0.05a | 656.61 ± 12.12g | 1748.08 ± 23.61i |

| RE (200 mg kg−1) | 1.30 ± 1.79b | 1.15 ± 0.21de | 2015.08 ± 9.08cd | 0.32 ± 0.03b | 2729.83 ± 70.87c | 3265.86 ± 19.25cde |

| RE (400 mg kg−1) | 1.45 ± 0.07b | 2.00 ± 0.01d | 1697.21 ± 27.95de | 0.36 ± 0.02b | 2395.68 ± 28.88d | 2947.42 ± 46.74fg |

| RE (600 mg kg−1) | 1.30 ± 0.14b | 1.25 ± 0.07de | 1566.46 ± 20.60b | 0.33 ± 0.03b | 2871.98 ± 23.72bc | 3604.56 ± 18.56b |

| RB (200 mg kg−1) | 1.30 ± 0.01b | 1.50 ± 0.01de | 1489.13 ± 1.51ef | 0.32 ± 0.01b | 2737.33 ± 25.08c | 3027.59 ± 30.81efg |

| RB (400 mg kg−1) | 1.20 ± 0.01b | 1.70 ± 0.04d | 1746.71 ± 12.29c | 0.30 ± 0.01b | 2680.84 ± 33.13cd | 3413.38 ± 0.51bcd |

| RB (600 mg kg−1) | 0.90 ± 0.00b | 0.10 ± 0.01e | 2939.22 ± 10.64a | 0.23 ± 0.01b | 4398.92 ± 9.89a | 5161.44 ± 4.78a |

| RH (200 mg kg−1) | 1.10 ± 0.01b | 2.45 ± 0.07d | 1062.95 ± 50.47g | 0.28 ± 0.01b | 2589.25 ± 50.20cd | 2881.13 ± 50.47g |

| RH (400 mg kg−1) | 1.20 ± 0.07b | 1.50 ± 0.14de | 1531.17 ± 46.96def | 0.30 ± 0.01b | 2825.50 ± 63.14bc | 3197.84 ± 108.86def |

| RH (600 mg kg−1) | 1.05 ± 0.07b | 1.45 ± 0.21de | 1636.36 ± 72.43cde | 0.26 ± 0.02b | 3137.71 ± 35.77b | 3545.45 ± 101.07bc |

| Organogel | ||||||

| Control | 2.50 ± 0.01b | 3.00 ± 0.05c | 913.14 ± 0.50i | 6.25 ± 0.04b | 1340.33 ± 0.51c | 1639.92 ± 0.10de |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 1.26 ± 0.01ef | 1.00 ± 0.02h | 2062.17 ± 8.02d | 3.15 ± 0.04ef | 2501.76 ± 62.81ab | 3234.29 ± 36.96ab |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 1.03 ± 0.04f | 0.95 ± 0.07h | 2300.90 ± 65.08c | 2.56 ± 0.09f | 3240.27 ± 108.86a | 3990.42 ± 134.91a |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 1.90 ± 0.07cd | 6.00 ± 0.01a | 1271.15 ± 6.89g | 4.75 ± 0.08cd | 1515.27 ± 18.66c | 2229.76 ± 7.41de |

| RE (200 mg kg−1) | 1.05 ± 0.07f | 1.60 ± 0.14efg | 1748.56 ± 80.48ef | 2.63 ± 0.18f | 3510.92 ± 103.20a | 3947.55 ± 11.41a |

| RE (400 mg kg−1) | 1.20 ± 0.02ef | 1.40 ± 0.02fgh | 1812.45 ± 10.91e | 3.00 ± 0.04f | 2791.36 ± 17.63ab | 3421.53 ± 0.41ab |

| RE (600 mg kg−1) | 1.60 ± 0.02de | 1.75 ± 0.35ef | 1648.38 ± 39.04f | 4.00 ± 0.03de | 2066.69 ± 36.28bc | 2486.07 ± 0.60bcd |

| RB (200 mg kg−1) | 1.10 ± 0.03f | 1.20 ± 0.01gh | 2421.28 ± 16.78b | 2.75 ± 0.01f | 2881.12 ± 2.73ab | 3727.96 ± 9.06a |

| RB (400 mg kg−1) | 1.00 ± 0.01f | 0.40 ± 0.01i | 2773.37 ± 43.59a | 2.50 ± 0.05f | 3145.11 ± 50.22a | 4041.56 ± 8.77a |

| RB (600 mg kg−1) | 1.01 ± 0.01f | 0.40 ± 0.02i | 2778.91 ± 33.17a | 2.53 ± 0.04f | 3063.91 ± 81.57ab | 4001.54 ± 56.60a |

| RH (200 mg kg−1) | 2.05 ± 0.07c | 2.00 ± 0.04e | 1358.18 ± 20.70g | 5.13 ± 0.18c | 1260.39 ± 26.83cd | 1994.06 ± 70.19d |

| RH (400 mg kg−1) | 4.10 ± 0.02a | 2.50 ± 0.71d | 1050.85 ± 50.43h | 10.25 ± 0.06a | 309.84 ± 12.28d | 988.30 ± 3.16e |

| RH (600 mg kg−1) | 2.10 ± 0.02bc | 4.00 ± 0.14b | 1112.39 ± 9.55h | 5.25 ± 0.08bc | 1091.83 ± 34.36cd | 1977.13 ± 5.06d |

| Emulsion gel | ||||||

| Control | 8.75 ± 0.35c | 5.25 ± 0.71bcd | 287.61 ± 9.28de | 2.19 ± 0.09c | 425.16 ± 20.52de | 516.37 ± 20.03f |

| R (200 mg kg−1) | 8.60 ± 2.26cd | 2.75 ± 0.31bcd | 365.25 ± 9.97cd | 2.15 ± 0.57cd | 451.17 ± 20.10de | 606.15 ± 23.06f |

| R (400 mg kg−1) | 7.50 ± 0.71cd | 3.50 ± 0.71bcd | 597.51 ± 10.03b | 1.88 ± 0.18cd | 489.93 ± 18.81d | 865.37 ± 28.50e |

| R (600 mg kg−1) | 3.00 ± 0.42e | 2.00 ± 0.08bcd | 1053.77 ± 50.54a | 0.75 ± 0.11e | 1194.90 ± 48.21c | 1727.17 ± 39.46d |

| RE (200 mg kg−1) | 8.10 ± 0.21cd | 9.00 ± 0.15ab | 372.95 ± 5.68cd | 2.02 ± 0.03cd | 421.03 ± 0.33de | 619.86 ± 8.09f |

| RE (400 mg kg−1) | 7.20 ± 0.21cd | 8.50 ± 0.71abc | 324.48 ± 16.25de | 1.80 ± 0.01cd | 440.68 ± 3.58de | 602.26 ± 16.25f |

| RE (600 mg kg−1) | 7.00 ± 0.14d | 8.50 ± 0.02abc | 353.55 ± 19.10d | 1.75 ± 0.01d | 426.32 ± 1.32de | 639.27 ± 19.10f |

| RB (200 mg kg−1) | 1.70 ± 0.02ef | 2.00 ± 0.03bcd | 710.44 ± 6.83b | 0.43 ± 0.02ef | 1588.41 ± 12.43b | 1886.91 ± 6.83c |

| RB (400 mg kg−1) | 1.20 ± 0.05f | 2.00 ± 0.05bcd | 481.63 ± 4.05c | 0.30 ± 0.01f | 1849.74 ± 19.09a | 2148.30 ± 4.04a |

| RB (600 mg kg−1) | 2.20 ± 0.14ef | 1.70 ± 0.42cd | 1096.10 ± 21.18a | 0.55 ± 0.04ef | 1597.00 ± 24.33b | 2007.05 ± 38.98b |

| RH (200 mg kg−1) | 17.40 ± 0.09a | 15.00 ± 0.10a | 226.47 ± 9.29e | 4.35 ± 0.02a | 189.09 ± 7.57f | 341.41 ± 7.13b |

| RH (400 mg kg−1) | 12.20 ± 0.07b | 1.00 ± 0.07d | 374.29 ± 11.59cd | 2.88 ± 0.18b | 321.30 ± 0.04ef | 538.22 ± 0.73f |

| RH (600 mg kg−1) | 8.40 ± 0.10cd | 2.45 ± 0.07bcd | 695.71 ± 19.86b | 4.75 ± 0.03cd | 392.14 ± 0.21de | 933.80 ± 19.86e |

Mean ± SD (n = 3). In each section of each column, means with different superscript letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). R: rosemary extract containing rosmarininc acid, ER: rosemary extract containing ethyl rosmarinate, BR: rosemary extract containing butyl rosmarinate, and HR: rosemary extract containing hexyl rosmarinate. rf: pseudo-first order rate constant of lipid hydroperoxide formation, rd: pseudo-second order rate constant of lipid hydroperoxide decomposition, Tp: the time when the rate of lipid hydroperoxide production reaches its maximum value, Kn: propagation oxidizability, PT: propagation period, and ET: end time of propagation period.

Among the emulsion gel samples containing antioxidants, sample containing RB (600 mg kg−1) showed the highest Tp, PT, and ET values. Therefore, similar to the initiation phase, the cut-off effect was also observed in the propagation phase.

4. Conclusion

The objective of the present research was to investigate how organogel and emulsion gel systems can affect the antioxidant activities of rosemary extracts containing rosmarinic acid esters with different hydrophobicity. The results showed that in linseed oil and organogel, R sample showed higher antioxidant activity than those of ER, BR, and HR samples in the initiation phase. However, BR samples showed higher antioxidant activity than those of R, ER, and HR samples in the propagation phase. In the case of emulsion gel samples, cut-off effect was observed and BR samples showed higher antioxidant activity than those of ER and HR samples. Besides, the investigated antioxidants showed lower antioxidant efficiency in organogel and emulsion gel samples than those of linseed oil. In general, in linseed oil and organogel samples, antioxidants with low hydrophobicity can show better efficiency than those with higher hydrophobicity, while those antioxidants with medium hydrophobicity can show better efficiency in emulsion gel. Taken together, applying rosmarinic acid in organogel and butyl rosmarinate in emulsion gel containing linseed oil can reduce the oxidation rate and extend the application of organogel and emulsion gel as solid fat replacer in food products. The results of the present research can help food industry manufacturers to apply most adapted antioxidative strategies in food products containing organogel and emulsion gel with polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary Fig. 1S.

Mass spectrum of rosmarinic acid.

Supplementary Fig. 2S.

Mass spectrum of ethyl rosmarinate.

Supplementary Fig. 3S.

Mass spectrum of butyl rosmarinate.

Supplementary Fig. 4S.

Mass spectrum of hexyl rosmarinate.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Malihe Keramat: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mohammad-Taghi Golmakani: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No. 4005536 and Shiraz University.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Asnaashari M., Farhoosh R., Sharif A. Antioxidant activity of gallic acid and methyl gallate in triacylglycerols of Kilka fish oil and its oil-in-water emulsion. Food Chemistry. 2014;159:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton-Carabin C.C., Ropers M.H., Genot C. Lipid oxidation in oil-in-water emulsions: Involvement of the interfacial layer. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2014;13(5):945–977. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-W., Fu S.-Y., Hou J.-J., Guo J., Wang J.-M., Yang X.-Q. Zein based oil-in-glycerol emulgels enriched with β-carotene as margarine alternatives. Food Chemistry. 2016;211:836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Losada-Barreiro S., Paiva-Martins F., Bravo-Diaz C. Polyphenolic antioxidants in lipid emulsions: Partitioning effects and interfacial phenomena. Foods. 2021;10(3):539. doi: 10.3390/foods10030539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker E.A., McClements D.J., Bourlieu-Lacanal C., Durand E., Figueroa-Espinoza M.C., Lecomte J., Villeneuve P. Hurdles in predicting antioxidant efficacy in oil-in-water emulsions. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2017;67:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. Reliable determination of the induction period and critical reverse micelle concentration of lipid hydroperoxides exploiting a model composed of pseudo-first and-second order reaction kinetics. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2018;98:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. Critical kinetic parameters and rate constants representing lipid peroxidation as affected by temperature. Food Chemistry. 2021;340 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. New insights into the kinetic and thermodynamic evaluations of lipid peroxidation. Food Chemistry. 2022;375 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolova Y.V., Sobolev R., Sarkisyan V., Kochetkova A. Paper presented at the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021. Approaches to study the oxidative stability of oleogels. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giacintucci V., Di Mattia C., Sacchetti G., Flamminii F., Gravelle A., Baylis B.…Pittia P. Ethylcellulose oleogels with extra virgin olive oil: The role of oil minor components on microstructure and mechanical strength. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;84:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golmakani M.-T., Moosavi-Nasab M., Keramat M., Mohammadi M.-A. Arthrospira platensis extract as a natural antioxidant for improving oxidative stability of common kilka (Clupeonella cultriventris caspia) oil. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2018;18(11):1315–1323. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v18_11_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.B., Rai D.K., Brunton N.P., Martin-Diana A.B., Barry-Ryan C. Characterization of phenolic composition in Lamiaceae spices by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(19):10576–10581. doi: 10.1021/jf102042g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamlow M.-A., Spyropoulos F., Mills T. 3D printing of kappa-carrageenan emulsion gels. Food Hydrocolloids for Health. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.fhfh.2021.100044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Golmakani M.-T., Aminlari M., Shekarforoush S.S. Comparative effect of Bunium persicum and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils and their synergy with citric acid on the oxidation of virgin olive oil. International Journal of Food Properties. 2016;19(12):2666–2681. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2015.1126722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Golmakani M.-T., Niakousari M., Toorani M.R. Comparison of the antioxidant capacity of sesamol esters in gelled emulsion and non-gelled emulsion. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Golmakani M.T., Toorani M.R. Effect of interfacial activity of eugenol and eugenol esters with different alkyl chain lengths on inhibiting sunflower oil oxidation. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 2021;123(7):2000367. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.202000367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klančnik A., Guzej B., Kolar M.H., Abramovič H., Možina S.S. In vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of commercial rosemary extract formulations. Journal of Food Protection. 2009;72(8):1744–1752. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-72.8.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre M., Bayrasy C., Panya A., Weiss J., McClements D.J., Lecomte J.…Villeneuve P. What makes good antioxidants in lipid-based systems? The next theories beyond the polar paradox. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2015;55(2):183–201. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.650335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre M., Bily A., Roller M., Birtić S. Mass transport phenomena in lipid oxidation and antioxidation. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 2017;8:391–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030216-025812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre M., Lopez Giraldo L.J., Lecomte J., Figueroa-Espinoza M.-C., Baréa B., Weiss J., Villeneuve P. Relationship between hydrophobicity and antioxidant ability of “phenolipids” in emulsion: A parabolic effect of the chain length of rosmarinate esters. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(5):2869–2876. doi: 10.1021/jf904119v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalitha P., Sivakamasundari S. Calculation of molecular lipophilicity and drug likeness for few heterocycles. Oriental Journal of Chemistry. 2010;26(1):135. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Panya A., Laguerre M., Bayrasy C., Lecomte J., Villeneuve P., Decker E.A. Comparison of antioxidant capacities of rosmarinate alkyl esters in riboflavin photosensitized oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 2013;90:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s11746-012-2163-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-L., Meng R., Xu B.-C., Zhang B., Cui B., Wu Z.-Z. Function emulsion gels prepared with carrageenan and zein/carboxymethyl dextrin stabilized emulsion as a new fat replacer in sausages. Food Chemistry. 2022;389 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena P., Cirlini M., Tassotti M., Herrlinger K.A., Dall’Asta C., Del Rio D. Phytochemical profiling of flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and volatile fraction of a rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract. Molecules. 2016;21(11):1576. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag F., Weiss J., McClements D.J. Low-energy formation of edible nanoemulsions: Factors influencing droplet size produced by emulsion phase inversion. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2012;388(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Xu X., Qian Z., Cheng H., Shen X., Chen S., Ye X. Xanthan gum-assisted fabrication of stable emulsion-based oleogel structured with gelatin and proanthocyanidins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;115 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panya A., Kittipongpittaya K., Laguerre M.L., Bayrasy C., Lecomte J.R.M., Villeneuve P.…Decker E.A. Interactions between α-tocopherol and rosmarinic acid and its alkyl esters in emulsions: Synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effect? Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60(41):10320–10330. doi: 10.1021/jf302673j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panya A., Laguerre M., Lecomte J., Villeneuve P., Weiss J., McClements D.J., Decker E.A. Effects of chitosan and rosmarinate esters on the physical and oxidative stability of liposomes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(9):5679–5684. doi: 10.1021/jf100133b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phonsatta N., Deetae P., Luangpituksa P., Grajeda-Iglesias C., Figueroa-Espinoza M.C., Le Comte J.R.M.…Panya A. Comparison of antioxidant evaluation assays for investigating antioxidative activity of gallic acid and its alkyl esters in different food matrices. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(34):7509–7518. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Jacobsen C., Villeneuve P., Durand E., Sørensen A.-D.M. Effects of different lipophilized ferulate esters in fish oil-enriched milk: Partitioning, interaction, protein, and lipid oxidation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(43):9496–9505. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantha N.C., Decker E.A. Rapid, sensitive, iron-based spectrophotometric methods for determination of peroxide values of food lipids. Journal of AOAC International. 1994;77(2):421–424. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/77.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherratt S.C., Villeneuve P., Durand E., Mason R.P. Rosmarinic acid and its esters inhibit membrane cholesterol domain formation through an antioxidant mechanism based, in nonlinear fashion, on alkyl chain length. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2019;1861(3):550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toorani M.R., Golmakani M.-T. Effect of triacylglycerol structure on the antioxidant activity of γ-oryzanol. Food Chemistry. 2022;370 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallverdú-Queralt A., Regueiro J., Martínez-Huélamo M., Alvarenga J.F.R., Leal L.N., Lamuela-Raventos R.M. A comprehensive study on the phenolic profile of widely used culinary herbs and spices: Rosemary, thyme, oregano, cinnamon, cumin and bay. Food Chemistry. 2014;154:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz E., Öğütcü M. Properties and stability of hazelnut oil organogels with beeswax and monoglyceride. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2014;91(6):1007–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11746-014-2434-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhang S., Zhong M., Qi B., Li Y. Soy and whey protein isolate mixture/calcium chloride thermally induced emulsion gels: Rheological properties and digestive characteristics. Food Chemistry. 2022;380 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Shahidi F. Antioxidant behavior in bulk oil: Limitations of polar paradox theory. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60(1):4–6. doi: 10.1021/jf204165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X., Gaudino N., Clark S., Acevedo N.C. Novel lecithin-based oleogels and oleogel emulsions delay lipid oxidation and extend probiotic bacteria survival. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.