Abstract

Human infection by Baylisascaris procyonis can result in larva migrans syndromes, which can cause severe neurological sequelae and fatal cases. The raccoon serves as the definitive host of the nematode, harboring adult worms in its intestine and excreting millions of eggs into the environment via its feces. Transmission to paratenic hosts (such as rodents, birds and rabbits) or to humans occurs by accidental ingestion of eggs. The occurrence of B. procyonis in wild raccoons has been reported in several Western European countries. In France, raccoons have currently established three separate and expanding populations as a result of at least three independent introductions. Until now the presence of B. procyonis in these French raccoon populations has not been investigated. Between 2011 and 2021, 300 raccoons were collected from both the south-western and north-eastern populations. The core parts of the south-western and north-eastern French raccoon populations were free of B. procyonis. However, three worms (molecularly confirmed) were detected in a young raccoon found at the edge of the north-eastern French raccoon population, close to the Belgian and Luxemburg borders. Population genetic structure analysis, genetic exclusion tests and factorial correspondence analysis all confirmed that the infected raccoon originated from the local genetic population, while the same three approaches showed that the worms were genetically distinct from the two nearest known populations in Germany and the Netherlands. The detection of an infected raccoon sampled east of the northeastern population raises strong questions about the routes of introduction of the roundworms. Further studies are required to test wild raccoons for the presence of B. procyonis in the area of the index case and further east towards the border with Germany.

Keywords: Raccoon, Baylisascaris procyonis, Expansion, Europe, Raccoon roundworm, Zoonotic risk

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First survey of Baylisascaris procyonis in French raccoons.

-

•

No infected raccoons among 299 from the core of the two populations.

-

•

Only one infected raccoon from the edge of the north-eastern population.

-

•

Genetic analyses confirms that the raccoon belongs to this north-eastern population.

-

•

B. procyonis worms are genetically distinct from the nearest known populations abroad.

1. Introduction

The roundworm Baylisascaris procyonis is the etiological agent of a zoonotic disease following accidental ingestion of the embryonated eggs containing larvae of the parasite. After hatching, the larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and cause visceral, ocular or neural larva migrans. The main lesions of Baylisascaris larva migrans consist of eosinophilic and granulomatous inflammation occurring in different organs and tissues, especially in the central nervous system, often leading to severe neurological sequelae or even death (Graeff-Teixeira et al., 2016). It affects children more frequently due to its fecal-oral transmission. Severe neurological sequelae and fatal cases have been reported in humans in the United States and Canada.

The raccoon (Procyon lotor) serves as the definitive host of the nematode, harboring adult worms in its intestine, with worm burden ranging from few worms to several hundreds. An infested raccoon can daily expel millions of unembryonated eggs in the environment via its feces. Under natural conditions, these eggs takes two to four weeks to embryonate and become infective. They can survive for years in the environment, but are sensitive to desiccation. Transmission to paratenic hosts (such as rodents, birds and rabbits) or to humans occurs through accidental ingestion of eggs, while raccoons can acquire the infection by the same route or by predation of paratenic hosts (Kazacos, 2001).

The raccoon is a native Central- and North American species, where prevalence of B. procyonis can easily exceed 60% and reach values around 80% (Kazacos and Boyce, 1989). The raccoons have now colonized many parts of the world after deliberate or accidental releases. Their presence in the wild has been confirmed in at least 27 European countries (Salgado, 2018). B. procyonis is present in some European populations, but absent in others, depending on whether the parasite was present in the founding individuals or subsequently in immigrants. In Germany, genetic studies have shown that the raccoon has been introduced via a number of separate introduction events, while fewer introduction events have been reported for the parasite (Osten-Sacken et al., 2018). In western Europe, the occurrence of B. procyonis in wild raccoons has been reported in Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria and northern Italy (Karamon et al., 2014; Al-Sabi et al., 2015; Heddergott et al., 2020; Duscher et al., 2021; Lombardo et al., 2022; Maas et al., 2022). At present only one non-fatal human case and four seropositive people have been reported in Europe, exclusively in Germany (Conraths et al., 1996). However, the expansion of raccoon populations and the close proximity of raccoons with humans in some urban areas increase the risk of zoonotic transmission, making it essential to identify endemic areas for public health prevention.

In France, raccoons have currently established three separate and expanding populations as the result of at least three independent introductions of a small number of individuals, based on genetic evidence (Larroque et al., 2023). The largest and oldest (1960s) population in northeastern France has progressively expanded and recently merged with populations from western Germany, Luxembourg and Belgium (Maillard et al., 2020). A second population in the Massif Central area (central France) become established in the late 1990s. It's origin is unclear. The third population settled in 2007 in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region in south-west France, probably from individuals escaped from zoological park. Until now, the presence of B. procyonis in these French raccoon populations has not been investigated. The only report of B. procyonis in France to date is the unexpected identification of copro-DNA in a wolf fecal sample in the French Alps, not linked to an established population of raccoons (Umhang et al., 2020). Determining the status of these three populations with regards to B. procyonis therefore required investigations in each of the three population foci. In this context, the possibility of collecting carcasses of raccoons from the two populations of the north-eastern and south-western France was used as an opportunity to determine the presence or absence of this zoonotic parasite.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study areas and raccoon sampling

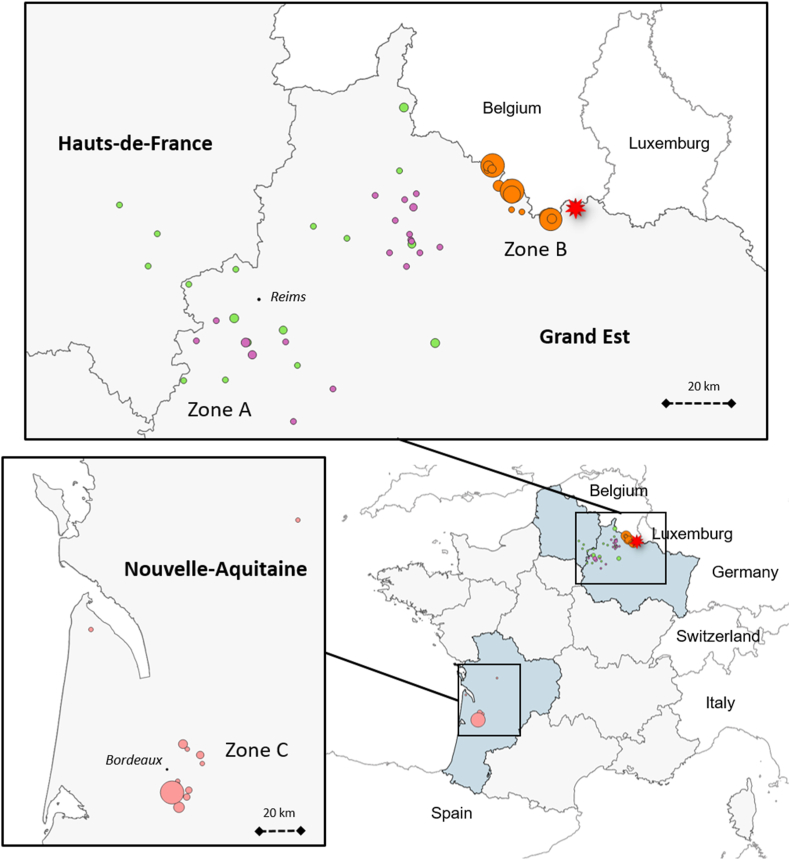

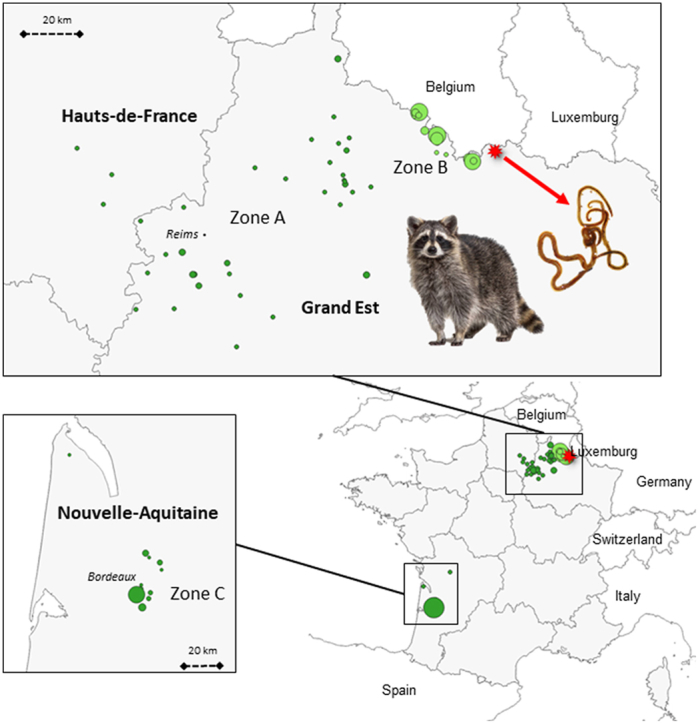

Raccoons were collected between 2011 and 2021 within the context of four different programs, named P1 to P4 (Table 1). In total, 300 raccoons were sampled in three different areas: two areas in north-eastern France - a large zone (A) sampling the core of the northeastern raccoon population and a zone (B) covering part of the French border with Belgium (Desvaux et al., 2021), and one area in southwestern France (Nouvelle-Aquitaine; zone C) (Fig. 1). All captures were performed by licensed trappers. Living animals were sacrificed according to the regulations relative to invasive species (French decree of 2/09/2016) and animal welfare guidelines (Directive 2010/63/EU) and stored frozen.

Table 1.

Information on the four programs that provided access to raccoon samples for the study.

| Information on the program |

Program 1 (P1) |

Program 2 (P2) |

Program 3 (P3) |

Program 4 (P4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling area | Zone A | Zone B | Zone C | |

| Raccoons population investigated | Northeast population | Northeast population | Northeast population, mixed with Belgium population | Southwest population |

| Region | Hauts-de-France and Grand-Est regions | Grand-Est region | Grand-Est region | Nouvelle Aquitaine region |

| Number of municipalities concerned | 10 | 20 | 15 | 13 |

| Period of sampling | 2011–2019 | 2019–2021 | 2019–2021 | 2019–2022 |

| Aim of the program | Study on B. procyonis | PhD program of Manon Gautrelet on Ecology of raccoons in France | Sanitary investigations on raccoons | Collaborative program of regulation |

| Sampling modalities | Capture by licensed trappers (regulation on invasive species), collection of road-killed animals | Trapping by licensed trappers (regulation on invasive species), collection of road-killed animals | Trapping in wild boar cages during control in France of the risk of African swine fever dispersion from Belgium; 2 road-killed raccoons found at less than 10 km at the east of zone B were also included | Consecutive and repeated sessions of live-trapping, dispersed capture by licensed trappers (regulation on invasive species); some road-killed individuals were also included |

| Partners of the program | Licenced trappers, URCA | Licensed trappers, URCA | OFB, Anses | Grege, ADPG, OFB, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, ENVT |

| Number of raccoons analyzed in the study | 25 | 26 | 157 | 92 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the raccoons sampled in zone A (program 1 green dots and program 2 purple dots), zone B (program 3, orange dots) and zone C (program 4, in pink dots). The red star-spot correspond to the raccoon found infected by Baylisascaris procyonis. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.2. Laboratory analyses

Thawed carcasses were necropsied to collect the intestines, stored at least 7 days at −80 °C before analyses. The intestines were divided into several segments (5–10) and opened longitudinally. Worms observed by macroscopic examination of the intestinal contents were isolated and washed in distilled water. We sampled around 25 mg of each worm for DNA extraction using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A PCR targeting a part of the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene was performed on the worm samples (Bowles et al., 1992; Umhang et al., 2020). After sequencing, the identification of the parasite species was established by comparison with the GenBank database using BLASTn.

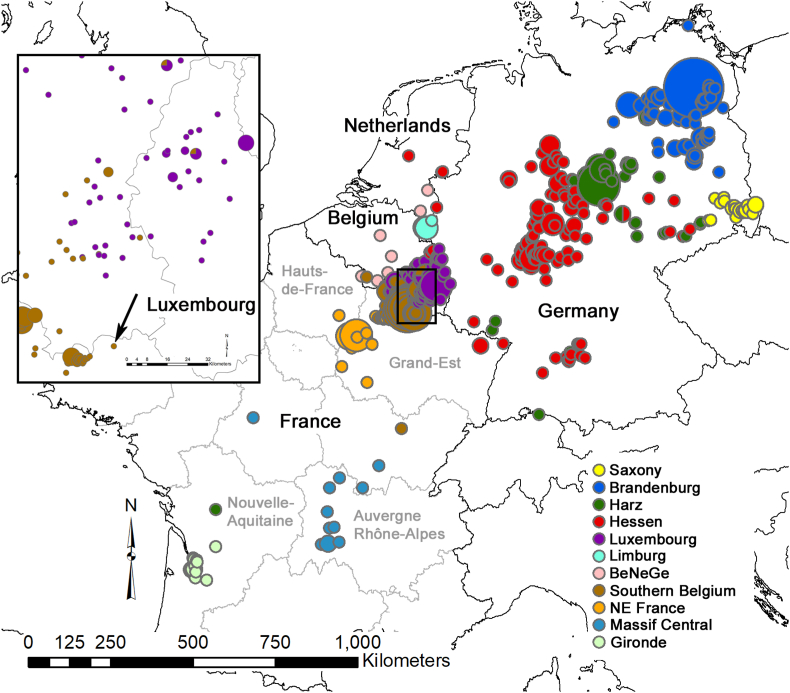

DNA was extracted from the raccoon tissue samples using an ammonium acetate-based salting-out method (Miller et al., 1988). In order to be able to use genetics to assign an infected raccoon to its likely population of origin, we genotyped 129 French raccoons, including individuals sampled from zones A, B and C, as well as from the raccoon population in the Massif Central area. A small number of animals from outside these study areas was also included (Fig. 2). Genotyping was performed using the same 17 microsatellite markers as previously (Maas et al., 2022). Because the work was performed in the same laboratory following the same protocols, it was possible to pool the present data with those previously obtained (Maas et al., 2022), generating a dataset consisting of 761 raccoon genotypes. We genotyped the three French roundworms isolated form the single infected raccoon (see Results) using the same 14 microsatellites as previously (Osten-Sacken et al., 2018). It was also possible to pool the three genotypes with the data previously generated (Maas et al., 2022), giving rise to a total dataset of 232 parasite genotypes.

Fig. 2.

Results of the analysis of the population genetic structure of raccoons in north-western Europe. The 11 genetic clusters were inferred by the program BAPS, taking geographic coordinates into account. The locations of six clusters that were each composed of a single individual are not shown. Different colors represent different genetic populations. Pie charts represent the genetic populations of origin of the individuals and their size is indicative of the number of samples included. The names of the genetic clusters are the same as those in (7) and (8). Inset: Focus on the clustering results from the region indicated by a black square in the main map. The arrow indicates the sampling location of the raccoon that was positive for B. procyonis. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

We analyzed the genetic structure of both species using the spatially explicit genetic clustering algorithm implemented in the software BAPSv.6.0 (Corander et al., 2008). The program was run 100 times for K = 20 (raccoon) or K = 10 (roundworm). We visualized the genetic relationship between the individuals in our datasets using a factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) in the program GENETIX v.4·05·2 (Belkhir et al., 2004). Individuals whose FC scores were more than six median absolute deviation (MAD) away from the median score of the first two eigenvectors were defined as outliers (Leys et al., 2013). Outliers were detected using the R package bigutilsr v.0.3.7 (Privé et al., 2020). GENECLASS 2.0.g (Piry et al., 2004) was used to calculate the probability (exclusion probability) of the infested raccoon and its roundworms belonging to each of the genetic populations inferred by BAPS. We calculated these exclusion probabilities based on the Monte Carlo method of Paetkau et al. (2004) and simulated 10,000 multi-locus genotypes. In the case of the roundworms, we calculated the probabilities of each reference animal originating from each BAPS-inferred reference cluster using a leave-one-out approach where individuals are excluded from their population during calculations (Paetkau et al., 2004).

3. Results and discussion

No B. procyonis worms were observed either in the 92 raccoons from the southwest population (zone C, P3), or in the 51 raccoons from zone A (P1 and P2) and the 157 trapped animals in zone B (P4). However, we found three worms (one female and two males), molecularly confirmed as B. procyonis, in one young raccoon (6–12 months) road-killed in February 2021. The animal was found at the edge of the north-eastern French raccoon population, 5 km east of the zone B trapping sites, and at 2 and 10 km from the Belgian and Luxemburg borders, respectively (Fig. 1), where the parasite has not yet been detected. Recently infected raccoons have been identified approximately 250 km to the east, in Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany (Reinhardt et al., 2023).

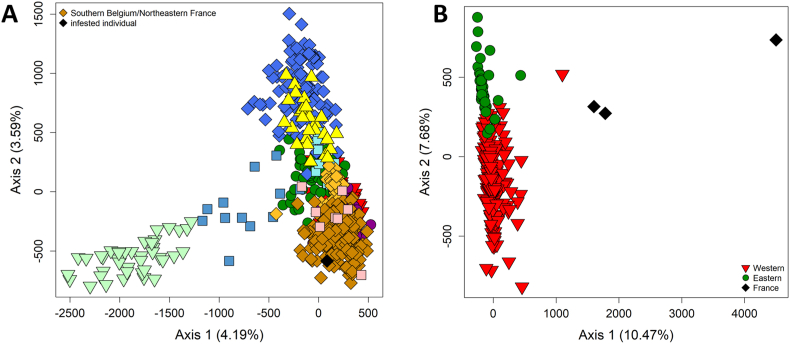

Regarding genetic analyses conducted on raccoons, the spatial algorithm of BAPS inferred a probability of 0.423 for the presence of 17 genetic clusters in the dataset (and a probability of 0.380 for the presence of 18 clusters). Of these, six clusters were each composed of a single individual and omitted from further analysis. The remaining 11 clusters (Fig. 2) corresponded to the meaningful clusters obtained by Maas et al. (2022) and Larroque et al. (2023). We confirmed the presence of four genetic populations in France. The northeastern-most cluster extended into southern Belgium. In Maas et al. (2022), this cluster is referred to as “southern Belgium”. The infested raccoon was sampled on the French/Belgian border near this “southern Belgium” population. BAPS assigned the infested raccoon to this population and the animal overlapped with its animals in the FCA (Fig. 3A). According to the genetic exclusion test (Table 2), the origin of the raccoon from the “southern Belgium” population could not be excluded (P = 0.481), in contrast to an origin from all other ten clusters (P < 0.01). The genetic analyses thus show clearly that the infested raccoon belonged to the local genetic population.

Fig. 3.

Factorial correspondence analysis of the microsatellite-based genetic profiles of raccoons and raccoon roundworms from northwestern Europe. A) Raccoon populations were pre-defined based on the clustering results generated by the spatial version of program BAPS (see Fig. 2). Different colors represent different genetic populations. The colors and the populations correspond to those illustrated on the map in Fig. 2. The six animals that each formed a distinct genetic cluster were omitted from the plot. The percentage of the total variation explained by each of the three axes is indicated. B) Raccoon roundworm populations were pre-defined based on the clustering results generated by the spatial version of program BAPS (see Fig. 3A). Different colors represent different genetic populations. The colors and the populations correspond to those illustrated on the map in Fig. 4. The percentage of the total variation explained by each of the three axes is indicated. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Probabilities of the multi-locus genotype of the B. procyonis-positive raccoon to be encountered in each of the 11 reference populations. These exclusion probabilities were calculated using GENECLASS 2.0.g. Populations were pre-defined based on the clustering results generated by the spatial version of program BAPS (see Fig. 2).

| Reference population | Exclusion probability |

|---|---|

| Gironde | <0.0001 |

| Massif Central | <0.0001 |

| NE France | <0.0001 |

| Southern Belgium | 0.4813 |

| BeNeGe | <0.0001 |

| Limburg | 0.0002 |

| Luxembourg | 0.0001 |

| Hessen | <0.0001 |

| Harz | 0.0084 |

| Brandenburg | <0.0001 |

| Saxony | <0.0001 |

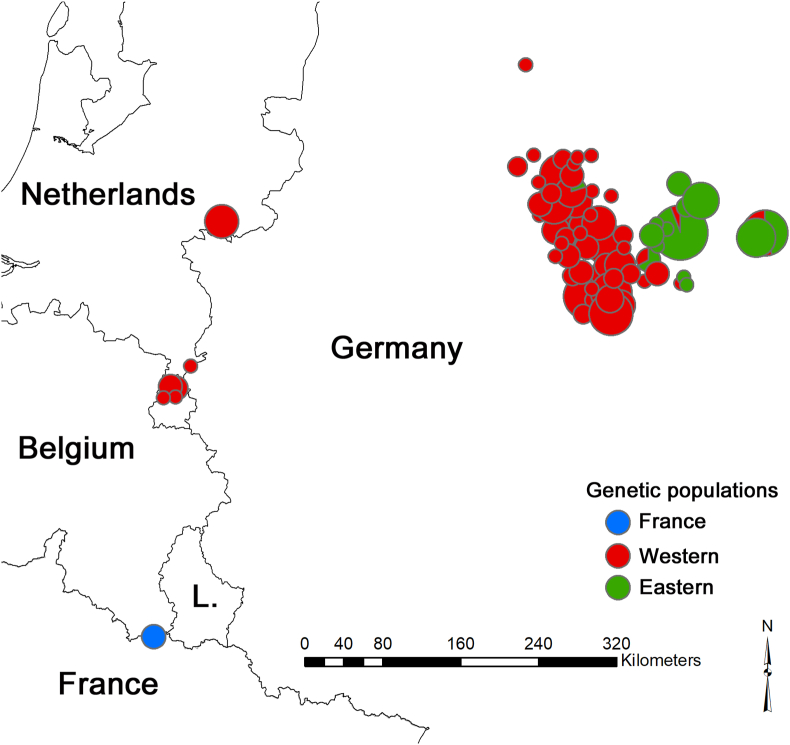

From genetic analyses carried out on B. procyonis worms, the spatial algorithm of BAPS inferred a probability of 0.908 for the presence of three genetic clusters in the dataset. The three roundworms sampled in a raccoon collected on the French/Belgian border formed a distinct genetic population (Fig. 4). Similar to Maas et al. (2022) and Osten-Sacken et al. (2018), we identified two distinct populations in central Germany (a “Western” and an “Eastern” population, Fig. 4). However, in contrast to Maas et al. (2022), the spatial algorithm of BAPS assigned the roundworms sampled in the Netherlands to their nearest German population (Western). Four roundworms were statistical outliers in the FCA, including the three French roundworms (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

Results of the analysis of the population genetic structure of raccoon roundworms in north-western Europe. The three genetic clusters were inferred by the program BAPS, taking geographic coordinates into account. Different colors represent different genetic populations. Pie charts represent the genetic populations of origin of the individuals and their size is indicative of the number of samples included. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

According to the genetic exclusion test (Table 3), one of the three French roundworms could be excluded from both Western and Eastern reference populations with high certainty (P < 0.001). We thus can confidently dismiss the possibility that this animal originated from a nearby roundworm population. The remaining two roundworms could be excluded from the Eastern population, but had exclusion probabilities that were slightly higher than the P < 0.01-threshold for the Western population (Table 3). When performing an exclusion test on the reference dataset using a leave-one-out approach, the probabilities of excluding the Western animals from their Western populations were an order of magnitude higher (P ≥ 0.125) than the values observed for the French worms (with the exception of the fourth FCA outlier; P = 0.027; Appendix Table 1). All the evidence, including the results of the exclusion tests, therefore suggests that these two worms are genetically distinct and also unlikely to originate from a neighboring population. Another potential source of infection for this young French raccoon would have been the ingestion of eggs from an infected latrine previously (up to several years ago according to survival of eggs in the environment) (Kazacos 2001)constituted by an infected raccoon not from this population but escape from a zoo or from another non genetically identified raccoon population.

Table 3.

Probabilities of the multi-locus genotypes of three French B. procyonis worms sampled from the same raccoon to be encountered in both reference populations. These exclusion probabilities were calculated using GENECLASS 2.0.g. Populations were pre-defined based on the clustering results generated by the spatial version of program BAPS (see Fig. 3B).

| Roundworm ID | Exclusion probabilities |

|

|---|---|---|

| Western population | Eastern population | |

| RL-Anses-88_1 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| RL-Anses-88_2 | 0.0196 | 0.0004 |

| RL-Anses-88_3 | 0.0284 | 0.0004 |

4. Conclusions

We established that the core parts of the southwestern and northeastern French raccoon populations were B. procyonis-free. However, we detect a very small burden of B. procyonis in one juvenile road-killed individual sampled east of the northeastern population. This raises strong questions about the routes of introduction of the roundworms: the infected raccoon is of local origin, but the easternmost raccoon sampled in France for parasitological investigations. Further studies investigating free-ranging raccoons for the presence of B. procyonis in the area of the index case and further to the east, towards the border with Germany must now to be carried out. An accidently released captive raccoon, either escaped from illegal private ownership or from a zoo, may have introduced these worms. It appears important to specifically test the raccoons in zoos and animal parks in the region and beyond for the presence of B. procyonis. The capture of free-ranging raccoons in the third main raccoon population in the Massif Central area in central France is currently underway.

In the present study, genetic analyses of raccoons and of the parasites were invaluable in attempting to understand the origin of the infection. As the effectiveness of these analyses are dependent on the number and geographical diversity of the samples in the reference dataset, this study highlights the need to strengthen data production with harmonized protocols to understand the dispersal of this invasive host and its parasite.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gérald Umhang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Alain C. Frantz: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hubert Ferté: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Christine Fournier Chambrillon: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Manon Gautrelet: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Thibault Gritti: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Nathan Thenon: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Guillaume Le Loc'h: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Estelle Isère-Laoué: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Fabien Egal: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Christophe Caillot: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Stéphanie Lippert: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mike Heddergott: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Pascal Fournier: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Céline Richomme: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests in association with this study.

Acknowledgements

For their collaboration and help, we thank David Gillet and Thibaut Petit from the Office Français de la Biodiversité, the veterinary students involved in the necropsy of raccoons at the national veterinary school of Toulouse, Jean-Marc Boucher at Anses Nancy laboratory for rabies and wildlife, Sebastien Macherez et Celyia Danzelle (URCA), Chloé Baduel, Matteo Tauzin and Katia Dumé from Grege. We are also grateful to Alain Devos and Remi Helder (URCA, Reims), respectively head supervisor and co-supervisor of the PhD of Manon Gautrelet on Ecology of raccoons in France, Isabelle Maille and the MRRNP for providing access to the study sites. Finally, special thanks to the Association Nationale Recherche et Technologie, the Office Français de la Biodiversité, the MRRNP, the Direction Régionale de l'Environnement, de l'Aménagement et du Logement of the Grand Est and the Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the Gironde Department Council, the commune of Villenave d'Ornon, the Departmental federation of hunting from Marne, the GREGE and the CERFE for funding this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2024.100928.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Al-Sabi M.N.S., Chriél M., Hansen M.S., Enemark H.L. Baylisascaris procyonis in wild raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Denmark. Vet. Parasitol.: Reg. Stud. Rep. 2015;1–2:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkhir K., Borsa P., Chikhi L., Raufaste N., Bonhomme F. GENETIX 4.05. Montpellier : Laboratoire Génome, populations. Interactions, CNRS UMR 5171: Université de Montpellier. 2004;II:1996–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Blair D., McManus D.P. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992;54:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conraths F.B.C., Cseke J., Laube H. Arbeitsplatzbedingte Infektionen des Menschen mit dem Waschbärspulwurm Baylisascaris procyonis. Arbeitsmedizin, Sozialmedizin, Umweltmedizin. 1996;31:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Corander J., Sirén J., Arjas E. Bayesian spatial modeling of genetic population structure. Comput. Stat. 2008;23:111–129. doi: 10.1007/s00180-007-0072-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux S., Urbaniak C., Petit T., Chaigneau P., Gerbier G., Decors A., Reveillaud E., Chollet J.Y., Petit G., Faure E., Rossi S. How to strengthen wildlife surveillance to support freedom from disease: example of ASF surveillance in France, at the border with an infected area. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.647439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duscher G.G., Frantz A.C., Kuebber-Heiss A., Fuehrer H.P., Heddergott M. A potential zoonotic threat: first detection of Baylisascaris procyonis in a wild raccoon from Austria. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2021;68:3034–3037. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff-Teixeira C., Morassutti A.L., Kazacos K.R. Update on Baylisascariasis, a highly Pathogenic zoonotic infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:375–399. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00044-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heddergott M., Steinbach P., Schwarz S., Anheyer-Behmenburg H.E., Sutor A., Schliephake A., Jeschke D., Striese M., Müller F., Meyer-Kayser E., Stubbe M., Osten-Sacken N., Krüger S., Gaede W., Runge M., Hoffmann L., Ansorge H., Conraths F.J., Frantz A.C. Geographic distribution of raccoon roundworm, Baylisascaris procyonis, Germany and Luxembourg. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:821–823. doi: 10.3201/eid2604.191670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamon J., Kochanowski M., Cencek T., Bartoszewicz M., Kusyk P. Gastrointestinal helminths of raccoons (Procyon lotor) in western Poland (Lubuskie province) - with particular regard to Baylisascaris procyonis. J. Vet. Res. 2014;58:547–552. doi: 10.2478/bvip-2014-0084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazacos K.R. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Mammals; 2001. Baylisascaris Procyonis and Related Species; pp. 301–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kazacos K.R., Boyce W.M. Baylisascaris larva migrans. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1989;195:894–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larroque J., Chevret P., Berger J., Ruette S., Adriaens T., Van Den Berge K., Schockert V., Léger F., Veron G., Kaerle C., Régis C., Gautrelet M., Maillard J.-F., Devillard S. Microsatellites and mitochondrial evidence of multiple introductions of the invasive raccoon Procyon lotor in France. Biol. Invasions. 2023;25:1955–1972. doi: 10.1007/s10530-023-03018-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leys C., Ley C., Klein O., Bernard P., Licata L. Detecting outliers: do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013;49:764–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo A., Brocherel G., Donnini C., Fichi G., Mariacher A., Diaconu E.L., Carfora V., Battisti A., Cappai N., Mattioli L., De Liberato C. First report of the zoonotic nematode Baylisascaris procyonis in non-native raccoons (Procyon lotor) from Italy. Parasites Vectors. 2022;15:24. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-05116-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas M., Tatem-Dokter R., Rijks J.M., Dam-Deisz C., Franssen F., van Bolhuis H., Heddergott M., Schleimer A., Schockert V., Lambinet C., Hubert P., Redelijk T., Janssen R., Cruz A.P.L., Martinez I.C., Caron Y., Linden A., Lesenfants C., Paternostre J., van der Giessen J., Frantz A.C. Population genetics, invasion pathways and public health risks of the raccoon and its roundworm Baylisascaris procyonis in northwestern Europe. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2022;69:2191–2200. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard J.F., Berger J., Chevret P., Ruette S., Adriaens T., Léger F., Veron G., Queney G., Devillard S. L’apport de la génétique dans la compréhension de l’évolution des populations de ratons laveurs. Faune Sauvage. 2020;326:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S.A., Dykes D.D., Polesky H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osten-Sacken N., Heddergott M., Schleimer A., Anheyer-Behmenburg H.E., Runge M., Horsburgh G.J., Camp L., Nadler S.A., Frantz A.C. Similar yet different: co-analysis of the genetic diversity and structure of an invasive nematode parasite and its invasive mammalian host. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018;48:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetkau D., Slade R., Burden M., Estoup A. Genetic assignment methods for the direct, real-time estimation of migration rate: a simulation-based exploration of accuracy and power. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:55–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2004.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piry S., Alapetite A., Cornuet J.-M., Paetkau D., Baudouin L., Estoup A. GENECLASS2: a software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. J. Hered. 2004;95:536–539. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privé F., Luu K., Blum M.G.B., McGrath J.J., Vilhjálmsson B.J. Efficient toolkit implementing best practices for principal component analysis of population genetic data. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:4449–4457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt N.P., Wassermann M., Härle J., Romig T., Kurzrock L., Arnold J., Großmann E., Mackenstedt U., Straubinger R.K. Helminths in invasive raccoons (Procyon lotor) from southwest Germany. Pathogens. 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/pathogens12070919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado I. Is the raccoon (Procyon lotor) out of control in Europe? Biodivers. Conserv. 2018;27:2243–2256. doi: 10.1007/s10531-018-1535-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umhang G., Duchamp C., Boucher J.M., Ruette S., Boué F., Richomme C. Detection of DNA from the zoonotic raccoon roundworm Baylisascaris procyonis in a French wolf. Parasitol. Int. 2020;78 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.