Abstract

Background

Pressure ulcers are areas of localised damage to the skin and underlying tissue caused by pressure or shear. Pressure redistribution devices are used as part of the treatment to reduce the pressure on the ulcer. The anatomy of the heel and the susceptibility of the foot to vascular disease mean that pressure ulcers located there require a particular approach to pressure relief.

Objectives

To determine the effects of pressure‐relieving interventions for treating pressure ulcers on the heel.

Search methods

In May 2013, for this first update, we searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid EMBASE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); and EBSCO CINAHL. No language or publication date restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the effects of pressure‐relieving devices on the healing of pressure ulcers of the heel. Participants were treated in any care setting. Interventions were any pressure‐relieving devices including mattresses and specific heel devices.

Data collection and analysis

Both review authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts and selected studies for inclusion. Both review authors independently extracted data and assessed studies for risk of bias.

Main results

In our original review, only one study met the inclusion criteria. This study (141 participants) compared two mattress systems; however, losses to follow up were too great to permit reliable conclusions. We did not find any further relevant studies during this first update.

Authors' conclusions

This review identified one small study at moderate to high risk of bias which provided no evidence to inform practice. More research is needed.

Keywords: Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Bedding and Linens; Heel; Beds; Foot Ulcer; Foot Ulcer/etiology; Foot Ulcer/therapy; Orthotic Devices; Patient Dropouts; Pressure Ulcer; Pressure Ulcer/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Pressure‐relieving devices for treating heel pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers (also known as pressure sores, decubitus ulcers and bed sores) are areas of localised damage to the skin and underlying tissue, believed to be caused by pressure, shear or friction. Pressure‐relieving devices such as beds, mattresses, heel troughs, splints and pillows are used as part of the treatment to reduce or relieve the pressure on the ulcer. Heel ulcers were studied specifically as their structure is very different to the other body sites which are prone to pressure ulcers (such as the bottom) and they are more prone to diseases, such as poor circulation, which do not affect other pressure ulcer sites. We identified one study that was at moderate to high risk of bias. This study lost over half the participants to follow up. More high quality research is needed to inform the selection of pressure relieving devices to treat pressure ulcers of the heel.

Background

Description of the condition

Aetiology of pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers (also known as pressure sores, decubitus ulcers and bed sores) are areas of localised damage to the skin and underlying tissue, believed to be caused by pressure, shear or friction (Allman 1997). They usually occur over bony prominences, such as the heel, where there is little soft tissue, in particular subcutaneous fat, to provide mobility and padding. Animal studies show the severity of tissue damage to be proportional to the time and intensity of the pressure (Kosiak 1959). This has also been shown to apply to humans in a study of people with spinal injuries (Reswick 1976).

Size of the problem

Pressure ulcers cause major morbidity and reduce the quality of life for participants and their carers (Essex 2009). The financial costs to the UK National Health Service (NHS) are also substantial. In the UK, the cost of preventing and treating pressure ulcers in a 600‐bedded large general hospital was estimated at between GBP £600,000 and £3 million per year (Clark 1994). Most published data on the prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers come from hospital populations. In the UK, pressure ulcer prevalence ranges from 5% to 32% and incidence from 2% to 29% depending on setting and case mix (Kaltenthaler 2001).

The majority of pressure ulcers are found on the lower body including the feet. Although pressure ulcers of the sacral or buttock region are the most common (Dealey 1991) the heels are frequently reported as affected (Dealey 1991a). In the UK most NHS Trusts collect data on the prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers. Repeated annual prevalence surveys from one UK hospital revealed that up to one‐quarter of all pressure ulcers were located on the heel (based on 19% to 26% in Table 1).

1. Leeds Teaching Hospitals heel ulcer prevalence.

| Year | Total no. PUs | No. of heel PUs | % of PUs on heel |

| 2006 | 274 | 60 | 22% |

| 2007 | 333 | 85 | 26% |

| 2008 | 336 | 74 | 22% |

| 2009 | 557 | 107 | 19% |

PU = pressure ulcer

Heel pressure ulcers

Heel ulcers are rarely the focus of research and furthermore most research is focused on reducing the risk of pressure ulcer development (i.e. prevention) rather than the treatment of active ulceration. Treatment strategies (for example, nutritional support) are generally based on the extrapolation of prevention research. This evidence is sparse and of generally poor quality and there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of nutritional supplements in prevention, and particularly treatment, of pressure ulcers (Langer 2003). The use of local pressure relief through support surfaces has been studied as a preventative intervention (McInnes 2011). The continued use of support surfaces, even when a pressure ulcer has occurred, is advocated to prevent further damage (RCN 2005). It is thought that people with diabetes may be particularly susceptible to pressure ulcers of the foot and indeed diabetic foot ulcers are wounds which occur anywhere on the feet; they may occur on the heel and be pressure‐related. There are two Cochrane systematic reviews on preventing and treating diabetic foot ulcers but these do not define foot ulcer and so may include pressure ulcers (Spencer 2000; Valk 2010). Neither of the reviews looked at heel ulcers as a subgroup. Since heel ulcers may represent a distinct clinical entity, in terms of risk and responses to treatment, they are worthy of specific scrutiny.

The feet are distinct from other body sites for the following reasons:

They are designed for weight‐bearing, with thickened dermis on the sole of the foot. This means that the skin has a relatively high number of collagen and elastic fibres to allow extensibility and elasticity and Pacinian corpuscles to identify pressure (Thoolen 2000) compared to skin found on most other areas of the body.

The circulation to the lower limbs often becomes compromised due to arterial diseases such as atherosclerosis. Although associated with increasing age (Vogt 1992), poor circulation is seen in younger people, particularly in association with risk factors such as smoking, diabetes and hypertension (Vogt 1992). The internal capillary pressures reduce and if subjected to external pressure are not able to respond appropriately to prevent occlusion (Kannell 1973).

Neuropathy (reduced or altered sensation) has been identified as a risk factor for ulceration in the feet of people with diabetes (McNeeley 1995). Neuropathy is also known to be associated with other diseases such as stroke, pernicious anaemia, spina bifida and multiple sclerosis although its precise prevalence is unknown (Neale 1981). Although no published papers have been identified so far, data collected during a study on pain in leg ulcers (Briggs 2003) has shown that many elderly people have some degree of neuropathy of the lower limbs. The presence of neuropathy may result in a person being unaware of pressure and, therefore, not responding to it (Raney 1989).

Oedema is the presence of excess extracellular fluid which causes localised swelling. It is associated with peripheral vascular disease, the effects of gravity on a dependent limb and other physiological changes (Ciocon 1993). The presence of oedema compromises tissue perfusion and removal of waste products (Ryan 1969). Also, the weight of the extra fluid in the feet is likely to result in normal resting pressures being exceeded, which may have an impact on tissue tolerance of pressure.

The absence of sebaceous glands on the sole of the foot results in a lack of lubrication of the skin; this may increase the likelihood of friction damage (Tortora 1996).

The superficial fascia is dense over the heel and contains loci of fat in facial pockets. Although this provides added protection from pressure, the effect of exceeding normal tissue tolerance has not been identified. This is likely to affect the response to pressure (Tortora 1996).

The presence of arterial disease and neuropathy may have an impact on the tolerance of the heel in terms of the extent and duration of applied pressure. Clearly these pathologies are less likely to influence other pressure sites such as the sacrum or ischial tuberosities (parts of the pelvis prone to pressure ulcers). The review of heel pressure ulcers as a separate entity is, therefore, a worthy study.

Description of the intervention

Once a heel pressure ulcer has occurred, treatment is concerned with reducing exposure of the heel to pressure and the management of the wound. The management of the wound is outside the scope of this review.

Reducing the extent and duration of applied pressure is achieved by changing a person's position, using equipment which provides an overall reduced pressure or alternating periods of low and high pressure or both. Pressure‐reducing supports can be for the whole body, for example mattresses, or specific to the body site such as foot protectors and booties. Most interventions are designed for pressure ulcer prevention; however, if an ulcer has occurred it is necessary to reduce the risks of further tissue breakdown.

Devices that reduce the magnitude of the applied pressure are thought to work by distributing body weight over a larger surface area, by conforming to the shape of the body generally or the heel specifically. These are known as constant low pressure devices (CLP). They vary in their construction, for example foam, gel, sheepskin, or an air‐filled or water‐filled device. Devices which reduce the duration of pressure use a system of air‐filled cells (AP) which alternate between high and low pressure by inflation and deflation of alternate cells. Other devices remove pressure from the body site at risk, for example by supporting the foot or calf in a splint, using a foot trough or pillow that leaves the heel with no surface contact.

Why it is important to do this review

Very little is known about the contribution of the reduction or relief of pressure to the wound‐healing process. The rationale for this review is based on the assumption that the reduction of external pressure on the pressure ulcer will have a positive effect on the wound‐healing process.

Objectives

To determine the effects of pressure‐relieving devices for treating pressure ulcers on the heel.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which compare the effects of pressure‐relieving devices on the healing of heel pressure ulcers. RCTs focusing specifically on pressure relief for diabetic foot ulcers were included if heel ulcer data were separately identified. Controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were to be included in the absence of RCTs.

Types of participants

Studies involving participants with existing heel pressure ulcers of any grade (RCN 2005) and in any care setting.

Types of interventions

Pressure‐relieving, re‐distributing or reducing aids used alone or in combination. Pressure‐relieving aids include the following:

mattresses;

foam overlays;

foam mattress replacements;

alternating air‐filled overlays;

alternating air‐filled mattress replacements;

air overlays; and

air‐fluidised bead beds.

Heel‐specific aids:

air‐filled booties;

foam foot protectors;

gel foot protectors;

pillows and other aids positioned under the legs to redistribute pressure;

splints or other medical devices; and

sheepskins.

Eligible comparisons would be any of the interventions listed above compared with each other, no intervention or standard care as defined by the trialists. To be eligible for inclusion treatment arms differed only in the pressure‐relief; local wound care (which is usually used in combination with pressure relief) should not have differed systematically across treatment arms within a trial.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Trials reporting any of the following outcomes at any endpoint were eligible.

Proportion of heel ulcers healed within a defined time period.

Time to complete healing of heel ulcers.

Secondary outcomes

Costs of pressure‐relieving device.

Total costs of interventions (including service and maintenance).

Patient comfort.

Ease of use.

Health‐related quality of life.

Adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

For the search methods used in the original version of this review see Appendix 1

Electronic searches

In May 2013, for this first update, we searched the following electronic databases to find reports of relevant RCTs:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 10 May 2013);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 4);

Ovid MEDLINE (2011 to May Week 1 2013);

Ovid EMBASE (2010 to 2013 Week 18);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, May 09 2013);

EBSCO CINAHL (2011 to 2 May 2013)

We used the following search strategy in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Beds] explode all trees251 #2 (bed or beds):ti,ab,kw 4202 #3 (mattress* or cushion* or pillow*):ti,ab,kw 662 #4 ("foam" or cutfoam or overlay*):ti,ab,kw 1010 #5 ("pad" or "pads" or padding):ti,ab,kw 1201 #6 ("gel" or "gels"):ti,ab,kw 5206 #7 (pressure next relie*):ti,ab,kw 111 #8 (pressure next device*):ti,ab,kw 80 #9 (pressure next redistribution*):ti,ab,kw 3 #10 (low next pressure next support*):ti,ab,kw 2 #11 ((constant or alternat*) next pressure*):ti,ab,kw 78 #12 ((air or water) next suspension*):ti,ab,kw 10 #13 (sheepskin* or (sheep next skin*)):ti,ab,kw 20 #14 "foot waffle":ti,ab,kw 2 #15 (air next bag*):ti,ab,kw 2 #16 (elevat* near/2 device*):ti,ab,kw 6 #17 "static air":ti,ab,kw 3 #18 MeSH descriptor: [Shoes] explode all trees246 #19 ("shoe" or "shoes" or "boot" or "boots" or booties):ti,ab,kw 558 #20 (footwear or "foot wear"):ti,ab,kw 123 #21 MeSH descriptor: [Orthotic Devices] explode all trees753 #22 (orthotic next (device* or therapy)):ti,ab,kw 476 #23 (orthos* or insole*):ti,ab,kw 1856 #24 ((contact or walk*) near/1 ("cast" or "casts")):ti,ab,kw 39 #25 (aircast or scotchcast):ti,ab,kw 57 #26 ((foot or feet) near/2 pressure):ti,ab,kw 85 #27 ((foot or feet) near/2 protect*):ti,ab,kw 5 #28 ((foot or feet) near/2 device*):ti,ab,kw 26 #29 (heel* near/2 pressure*):ti,ab,kw 33 #30 (heel* near/2 protect*):ti,ab,kw 8 #31 (heel* near/2 device*):ti,ab,kw 19 #32 (heel* near/2 (lift* or float* or splint* or glove* or suspension or elevat*)):ti,ab,kw 27 #33 (trough* near/2 (leg* or "foot" or "feet" or heel*)):ti,ab,kw 1 #34 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 14442 #35 MeSH descriptor: [Pressure Ulcer] explode all trees510 #36 pressure next (ulcer* or sore*):ti,ab,kw 916 #37 decubitus next (ulcer* or sore*):ti,ab,kw 92 #38 (bed next sore*) or bedsore:ti,ab,kw 51 #39 #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 983 #40 #34 and #39 332

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 2; Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 respectively. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2010). There were no restrictions on the basis of date or language of publication.

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of all retrieved and relevant publications identified by these strategies for further studies. We contacted experts in the field and asked them if they had been involved in any further studies or were aware of recently completed or ongoing studies. We contacted manufacturers of pressure‐relieving equipment to request any studies they may have conducted which include heel pressure ulcers. Other journals (Phlebology and Diabetic Foot), which we had originally intended to handsearch, are now indexed in MEDLINE, therefore we undertook no additional handsearching.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both review authors independently examined the titles and abstracts of citations generated by the search to identify those likely to meet the inclusion criteria and retrieved these in full. We resolved disagreements by consensus. The two review authors independently assessed the full‐text articles against the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

We extracted and summarised details of eligible trials using a data extraction sheet. We extracted the following data:

author, title, date of study and publication;

sample size;

participant inclusion and exclusion criteria;

care setting;

baseline variables, for example age, sex, diagnosis, co‐morbidity, baseline risk, details of existing ulcers;

description of interventions;

numbers of participants ‐ both randomised and analysed;

description of any co‐interventions;

follow‐up period;

results;

outcome measures;

adverse events;

use of intention‐to‐treat analysis; and

trialists' conclusions.

We made attempts to obtain any missing data by contacting the study authors. We included data from studies that had been published more than once only once, however, where trials were published more than once then the data extraction process utilised all available sources to facilitate the retrieval of the maximum amount of trial data possible. Two review authors independently undertook data extraction. We resolved disagreement by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

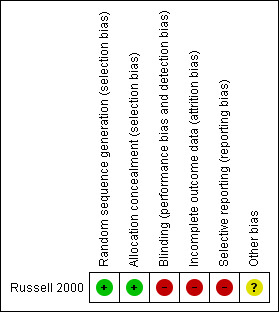

Two review authors independently assessed each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). This tool addresses six specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (e.g. extreme baseline imbalance) (see Appendix 5) for details of criteria on which the judgement is based). We assessed blinding and completeness of outcome data for each outcome separately. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each eligible study and discussed any disagreement to achieve a consensus.

We presented an assessment of risk of bias using a 'Risk of bias' summary figure (Figure 1), which presents all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We intended to estimate the extent of heterogeneity between study results using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This examines the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. Due to the small number of studies heterogeneity was not assessed.

Data synthesis

We presented a narrative summary of results. The planned method of synthesising the studies depended upon the quality, design and heterogeneity of studies identified. As only one study was identified, it was not possible to consider conducting a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to assess whether the presence of a wound in a specific condition, for example in a person with diabetes, has any effect on treatment. We had also planned subgroup analysis according to grade of ulcer; it is known that the reliability of pressure ulcer diagnosis and classification is particularly poor with grade 1 pressure ulcers (Nixon 2005). Due to the lack of data, we performed no subgroup analyses.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The total number of citations retrieved by all the searches was 628 (467 after duplicates were removed). Following independent review of the abstracts by the two review authors, we thought 75 potentially met the inclusion criteria or contained useful references and retrieved these in full (two review papers were not retrieved due to translation difficulties). The two review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion according to the selection criteria. Several studies would have been eligible if the original data were available and heel outcomes could be analysed separately. We wrote to or contacted 21 authors; we received three responses: one stating no heel ulcers were included, one stating that no separate data were available and one providing the original thesis with full methods and results (Russell 2000). We sent letters or emails to 10 wound care experts and received three replies. We sent 15 letters to manufacturers of pressure‐relieving devices and received two responses. The letters did not identify any further trials.

Included studies

We identified one study which met the criteria for inclusion (Russell 2000). This study was carried out in an elderly care setting in the UK, with participants having illnesses such as dementia, neurological disabilities or cardiovascular disease.Russell 2000 included 141 participants (113 with heel pressure ulcers), average age of 84.7 years who were randomised to either one of the alternating air‐filled mattress replacement and cushion systems. Outcomes measures were "completed study", defined as healed, discharged or died. See Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 71 studies: 10 were reviews, 18 studies were not RCTs, 18 studies were concerned with prevention (not treatment) of the ulcer, nine considered treatment of the ulcers on body sites other than heels, 15 considered treatment of the ulcer on various body sites including heels but data could not be analysed separately and two were reviews in another language. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1.

In the Russell 2000 study there was adequate sequence generation through computer‐generated random numbers and allocation was concealed. Blinding of the participant and caregiver to interventions is not possible when equipment (from which the patient cannot be moved) is used as the allocation is visually obvious. Russell stated that to prevent bias, the monitoring of the data collection and protocol compliance was carried out by a team member who was 'blinded' to the statistical analysis, however data were collected by nurses who would not have been blind to the intervention. Incomplete outcome data were not adequately addressed; 72 out of the 113 patients (64%) died, were discharged or did not heal. The outcomes were ulcer healed, patients discharged or died but these were reported together as "completed study", which made interpretation difficult. The study reported baseline comparability of the two groups with respect to age, risk of developing pressure ulcers, grade and severity of pressure ulcer but did not report gender and duration of the pressure ulcers. Overall this study should be judged as at moderate risk of bias; many of the bias domains are satisfied but the very high drop‐out rate would moderate the overall judgement.

Effects of interventions

1. Comparison of two different alternating mattress replacement and cushion systems (one RCT, 141 people)

This study (Russell 2000) randomised 141 people of whom 113 had heel pressure ulcers to one of two different alternating mattress replacement systems either the Huntleigh Nimbus 3 mattress (this has a 1 in 2 alternating cycle) and Aura cushion system (n = 70) or the Pegasus Cairwave (this has a 1 in 3 alternating cycle) mattress and Proactive cushion (n = 71). This study included outcomes for sacral and heel pressure ulcers. As a result of communication with the author, heel data were provided and could be analysed separately.

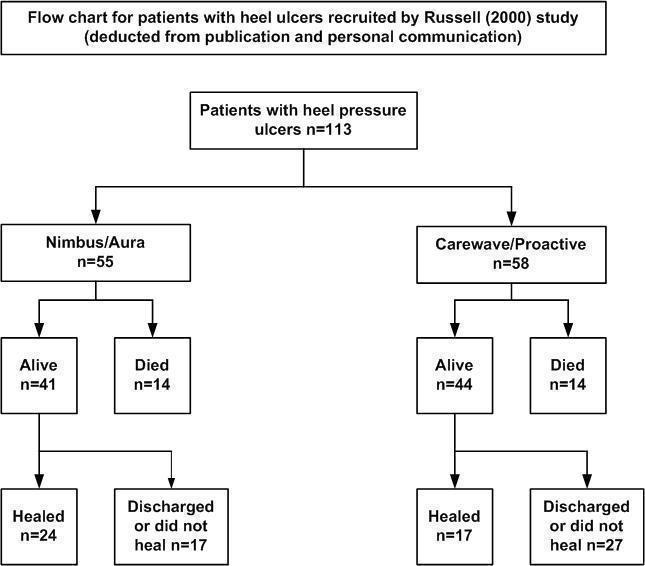

Primary outcome

The proportion of heel ulcers healed was not reported in the published study, therefore we have analysed data using both the study outcome of "completed study" and heel ulcers healed (based on additional data provided by the author). We have generated a flow chart from both the published data and data from personal communication with the author (Figure 2).

2.

Flow chart for patients with heel ulcers recruited by Russell (2000) in the study

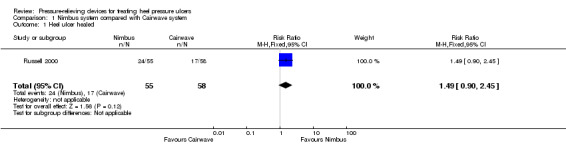

The outcome of "completed study" is defined as 'healed, discharged or died' at the end of the 18‐month follow‐up period. In the Nimbus group 24/55 participants and in the Cairwave group 17/58 participants healed. There was no significant difference when using either mattress system in the number of heel ulcers healed (RR 1.49; 95% CI 0.90 to 2.45)(Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nimbus system compared with Cairwave system, Outcome 1 Heel ulcer healed.

There is a high risk of attrition bias as many people were lost to follow up: n = 17/55 (56%) in the Nimbus group and n = 27/58 (71%) in the Cairwave group were discharged or lost to follow up. Fourteen participants died in each group.

Secondary outcomes

Cost of pressure‐relieving device

Not reported.

Total costs of interventions (including service and maintenance) where given

Not reported (economic analysis was planned but not reported in the documents available).

Patient comfort

Patient comfort was measured using a digital analogue scale taken from Gray 1994; data were collected by members of the audit department. It contained questions which assessed mattress comfort, sleep and cushion comfort. Statistical analyses were carried out only on data from participants who completed the trial; results were not separated out for participants with sacral or heel pressure ulcers. Mean comfort scores were calculated for each question and did not show any statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 2).

2. Patient assessment of mattress comfort.

| Q1a | Q1b | Q2 | N | |

| Nimbus (completed) | 1.71 (± 0.68) | 2.48 (± 1.32) | 2.81 (± 0.96) | 29 |

| Cairwave (completed) | 1.94 (± 0.82) | 2.04 (± 1.30) | 2.46 (± 0.92) | 24 |

| Nimbus (discontinued) | 2.33 (± 1.81) | 2.25 (± 1.89) | 2.50 (± 1.0) | 4 |

| Cairwave (discontinued) | 2.51 (± 1.04) | 3.50 (± 1.69) | 3.56 (± 1.12) | 8 |

Q1 a and b refer to mattress comfort, Q2 asked about sleep. Results are mean comfort scores from visual analogue scale (± standard deviation). Results are from both heel ulcer and sacral ulcer participants. All results were not significant.

Ease of use

No differences reported.

Health‐related quality of life

Not reported.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported.

Subgroup analysis, e.g. co‐morbidity or grade of ulcer

Russell 2000 used the Torrance scale to grade the pressure ulcers and only recruited those with Grade 2 and above. However, Grade 2 includes non‐blanching erythema with and without epidermal loss. The data available for heels has insufficient detail of Grades of ulcer to perform any subgroup analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Overall, there is insufficient evidence to determine the relative effects of pressure‐relieving devices for healing pressure ulcers of the heel. Only one RCT met the inclusion criteria, it had high losses to follow up therefore findings need to be viewed with caution. The use of the outcome "completed study" made interpretation of data difficult since it included healed, discharged and died. There was no reported difference in the outcome of comfort between the two groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall the evidence base is lacking.

Potential biases in the review process

Two non‐English review papers were identified by the search process but no translation was requested as only the bibliographies of reviews were being checked for further citations. There may be a potential risk of language bias with this process. There could be a risk of publication bias as studies of pressure‐relieving devices are frequently sponsored by the manufacturers. Results which show no difference or no benefit in their product may not be published. We contacted product manufacturers and experts in the field to reduce this risk.

Comments on search strategy

The search strategy was developed to include studies of participants with diabetic foot ulcers. There was a possibility that such studies may have included heel pressure ulcers. The list of titles generated did not include any diabetic foot ulcer papers. On reflection this may have been related to the fact that the strategy did not include the free‐text term '(heel or foot or feet) near ulcer'. Discussion took place with the Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Wounds Group and we informally examined citations of treatment studies for foot ulcers in people with diabetes which were identified in other systematic reviews. Most of these were found to include only ulcers on the plantar surface of the foot or forefoot and some specifically excluded ulcers on the heels. The potential benefit of re‐writing and running the strategy for all the years, in all the databases at this moment was not thought to justify the work entailed. This would, however, be a consideration for the future.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Current guidelines for practice (RCN 2005), based on a review of support surfaces for all pressure ulcers, recommend the use of pressure‐relieving devices for all participants with pressure ulcers. Clinical staff, policy makers and users should be mindful that there is no evidence to support one support surface over another for heel pressure ulcers and consideration should be given to participants' quality of life (pain, discomfort, activity and mobility, intrusiveness (noise, size of device) as a priority as well as ease of use, reliability, and direct and indirect costs (purchase price, lifespan, maintenance).

Implications for research.

Clearly further well‐designed trials of support surfaces (and in particular devices specifically for heel pressure relief) for treating heel pressure ulcers are needed. Consideration needs to be given to the populations to be studied; these need to include elderly, vascular, diabetic and orthopaedic participants in both hospital and community settings.

Recruiting sufficient participants to pressure ulcer studies can be difficult as many participants appear incapacitated. The high mortality rate in the pressure ulcer population is a major challenge when planning a trial. To ensure sufficient participants are followed up to complete healing will always be difficult. Potential solutions involve exclusion of participants who are likely to die in the short term, and use of survival analysis methods which can use data from patients up until the point of censoring (death).

In modern inpatient settings, the movement of participants between wards and early discharge to alternative care risks compromising data collection. Robust participant follow up with the continuation of the trial intervention needs to take place. Given the high mortality rates in participants with pressure ulcers, healing may not be the most important outcome of interest. More consideration should be given to what are traditionally considered to be secondary outcomes, such as participant quality of life and cost‐effectiveness of the interventions.

The need to distinguish between the populations of participants with sacral, ischial and heel pressure ulcers remains. The risk factors for healing are different, as are the effects on their quality of life both of the ulcer and of the device used to treat it.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 September 2013 | New search has been performed | First update, new search. No new studies with heel specific data have been identified. |

| 6 September 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions remain unchanged |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 9, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 24 August 2005 | New citation required and major changes | Substantive amendment. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Cochrane Wounds Group referees (David Brienza, Duncan Chambers, Mike Coulson, Madeleine Flanagan, Lisa Jones, Ruth Ropper, Janet Yarrow) and Editors, Julie Bruce, David Margolis, Joan Webster and Gill Worthy for their comments to improve the protocol and the review. In addition Sally Bell‐Syer and Ruth Foxlee of the Cochrane Wounds Group and Nicky Cullum, Department of Health Sciences, University of York for their invaluable help in developing the protocol, search strategies and review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods for the original version of the review (2011)

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to find reports of relevant RCTs:

Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 25 March 2011);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1948 to March Week 3 2011);

Ovid EMBASE (1980 to 2011 Week 12);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations March 29, 2011);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 25 March 2011)

We used the following search strategy in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

#1 MeSH descriptor Beds explode all trees #2 (bed or beds):ti,ab,kw #3 (mattress* or cushion* or pillow*):ti,ab,kw #4 ("foam" or cutfoam or overlay*):ti,ab,kw #5 ("pad" or "pads" or padding):ti,ab,kw #6 ("gel" or "gels"):ti,ab,kw #7 (pressure NEXT relie*):ti,ab,kw #8 (pressure NEXT device*):ti,ab,kw #9 (pressure NEXT redistribution*):ti,ab,kw #10 (low NEXT pressure NEXT support*):ti,ab,kw #11 ((constant or alternat*) NEXT pressure*):ti,ab,kw #12 ((air or water) NEXT suspension*):ti,ab,kw #13 (sheepskin* or (sheep NEXT skin*)):ti,ab,kw #14 "foot waffle":ti,ab,kw #15 (air NEXT bag*):ti,ab,kw #16 (elevat* NEAR/2 device*):ti,ab,kw #17 "static air":ti,ab,kw #18 MeSH descriptor Shoes explode all trees #19 (“shoe” or “shoes” or “boot” or “boots”or booties):ti,ab,kw #20 (footwear or "foot wear"):ti,ab,kw #21 MeSH descriptor Orthotic Devices explode all trees #22 (orthotic NEXT (device* or therapy)):ti,ab,kw #23 (orthos* or insole*):ti,ab,kw #24 ((contact or walk*) NEAR/1 ("cast" or "casts")):ti,ab,kw #25 (aircast or scotchcast):ti,ab,kw #26 ((foot or feet) NEAR/2 pressure):ti,ab,kw #27 ((foot or feet) NEAR/2 protect*):ti,ab,kw #28 ((foot or feet) NEAR/2 device*):ti,ab,kw #29 (heel* NEAR/2 pressure*):ti,ab,kw #30 (heel* NEAR/2 protect*):ti,ab,kw #31 (heel* NEAR/2 device*):ti,ab,kw #32 (heel* NEAR/2 (lift* or float* or splint* or glove* or suspension or elevat*)):ti,ab,kw #33 (trough* NEAR/2 (leg* or “foot” or “feet” or heel*)):ti,ab,kw #34 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33) #35 MeSH descriptor Pressure Ulcer explode all trees #36 pressure NEXT (ulcer* or sore*):ti,ab,kw #37 decubitus NEXT (ulcer* or sore*):ti,ab,kw #38 (bed NEXT sore*) or bedsore:ti,ab,kw #39 (#35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38) #40 (#34 AND #39)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 1; Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 respectively. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision). We combined the Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). There were no restrictions on the basis of date or language of publication.

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of all retrieved and relevant publications identified by these strategies for further studies. We contacted experts in the field and asked them if they had been involved in any further studies or were aware of recently completed or ongoing studies. We contacted manufacturers of pressure‐relieving equipment to request any studies they may have conducted which include heel pressure ulcers. Other journals (Phlebology and Diabetic Foot), which we had originally intended to handsearch, are now indexed in MEDLINE, therefore we undertook no additional handsearching.

Appendix 2. Ovid MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Beds/ (1771) 2 (bed or beds).ti,ab. (44010) 3 (mattress$ or cushion$ or pillow$).ti,ab. (4010) 4 (foam$1 or cutfoam or overlay$).ti,ab. (12998) 5 (pad or pads or padding).ti,ab. (12432) 6 gel$1.ti,ab. (112229) 7 pressure relie$.ti,ab. (423) 8 pressure device$.ti,ab. (374) 9 pressure redistribution$.ti,ab. (44) 10 low pressure support$.ti,ab. (7) 11 ((constant or alternat$) adj pressure$).ti,ab. (994) 12 ((air or water) adj suspension$).ti,ab. (187) 13 (sheepskin$ or sheep skin$).ti,ab. (81) 14 foot waffle.ti,ab. (4) 15 air bag$.ti,ab. (285) 16 (elevat$ adj2 device$).ti,ab. (28) 17 static air.ti,ab. (33) 18 exp Shoes/ (2293) 19 (shoe$1 or boot1$ or booties).ti,ab. (3068) 20 (footwear or foot wear).ti,ab. (1197) 21 exp Orthotic Devices/ (4933) 22 (orthotic adj (device$ or therapy)).ti,ab. (202) 23 (orthos$ or insole$).ti,ab. (8211) 24 ((contact or walk$) adj cast$1).ti,ab. (155) 25 (aircast or scotchcast).ti,ab. (71) 26 ((foot or feet) adj2 pressure).ti,ab. (517) 27 ((foot or feet) adj2 protect$).ti,ab. (78) 28 ((foot or feet) adj2 device$).ti,ab. (70) 29 (heel$ adj2 pressure$).ti,ab. (117) 30 (heel$ adj2 protect$).ti,ab. (22) 31 (heel$ adj2 device$).ti,ab. (33) 32 (heel$ adj2 (lift$ or float$ or splint$ or glove$ or suspension or elevat$)).ti,ab. (125) 33 (trough$ adj2 (leg$ or foot or feet or heel$)).ti,ab. (4) 34 or/1‐32 (200787) 35 exp Pressure Ulcer/ (5330) 36 (pressure adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (4455) 37 (decubitus adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (596) 38 (bedsore$ or (bed adj sore$)).ti,ab. (246) 39 or/35‐38 (6681) 40 34 and 39 (1523) 41 randomized controlled trial.pt. (247475) 42 controlled clinical trial.pt. (40136) 43 randomized.ab. (201843) 44 placebo.ab. (93559) 45 clinical trials as topic.sh. (80952) 46 randomly.ab. (138890) 47 trial.ti. (75242) 48 or/41‐47 (558737) 49 Animals/ (2530681) 50 Humans/ (7027945) 51 49 not 50 (1649878) 52 48 not 51 (508211) 53 40 and 52 (199) 54 (2011* or 2012* or 2013*).ed. (1739816) 55 53 and 54 (27)

Appendix 3. Ovid EMBASE search strategy

1 exp bed/ (5267) 2 (bed or beds).ti,ab. (68300) 3 (mattress$ or cushion$ or pillow$).ti,ab. (5468) 4 (foam$1 or cutfoam or overlay$).ti,ab. (19347) 5 (pad or pads or padding).ti,ab. (19364) 6 gel$1.ti,ab. (150388) 7 pressure relie$.ti,ab. (589) 8 pressure device$.ti,ab. (550) 9 pressure redistribution$.ti,ab. (54) 10 low pressure support$.ti,ab. (12) 11 ((constant or alternat$) adj pressure$).ti,ab. (1474) 12 ((air or water) adj suspension$).ti,ab. (332) 13 (sheepskin$ or sheep skin$).ti,ab. (107) 14 foot waffle.ti,ab. (5) 15 air bag$.ti,ab. (342) 16 (elevat$ adj2 device$).ti,ab. (34) 17 static air.ti,ab. (67) 18 exp Shoe/ (4187) 19 (shoe$1 or boot1$ or booties).ti,ab. (4507) 20 (footwear or foot wear).ti,ab. (1788) 21 exp Orthotics/ (2074) 22 (orthotic adj (device$ or therapy)).ti,ab. (294) 23 (orthos$ or insole$).ti,ab. (12271) 24 ((contact or walk$) adj cast$1).ti,ab. (194) 25 (aircast or scotchcast).ti,ab. (93) 26 ((foot or feet) adj2 pressure).ti,ab. (720) 27 ((foot or feet) adj2 protect$).ti,ab. (107) 28 ((foot or feet) adj2 device$).ti,ab. (95) 29 (heel$ adj2 pressure$).ti,ab. (141) 30 (heel$ adj2 protect$).ti,ab. (32) 31 (heel$ adj2 device$).ti,ab. (40) 32 (heel$ adj2 (lift$ or float$ or splint$ or glove$ or suspension or elevat$)).ti,ab. (155) 33 (trough$ adj2 (leg$ or foot or feet or heel$)).ti,ab. (5) 34 or/1‐33 (283533) 35 exp Decubitus/ (9408) 36 (pressure adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (5813) 37 (bedsore$ or (bed adj sore$)).ti,ab. (417) 38 (decubitus adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (806) 39 or/35‐38 (10611) 40 34 and 39 (2040) 41 Clinical trial/ (715292) 42 Randomized controlled trials/ (29861) 43 Random Allocation/ (51197) 44 Single‐Blind Method/ (15897) 45 Double‐Blind Method/ (87219) 46 Cross‐Over Studies/ (32445) 47 Placebos/ (169756) 48 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (82914) 49 RCT.tw. (10982) 50 Random allocation.tw. (931) 51 Randomly allocated.tw. (14603) 52 Allocated randomly.tw. (1227) 53 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (266) 54 Single blind$.tw. (9897) 55 Double blind$.tw. (92147) 56 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (248) 57 Placebo$.tw. (140349) 58 Prospective Studies/ (206934) 59 or/41‐58 (1077729) 60 Case study/ (16788) 61 Case report.tw. (170882) 62 Abstract report/ or letter/ (519805) 63 or/60‐62 (703087) 64 59 not 63 (1048538) 65 animal/ (730814) 66 human/ (8821758) 67 65 not 66 (489053) 68 64 not 67 (1026150) 69 40 and 68 (376) 70 (2010* or 2011* or 2012* or 2013*).em. (3681732) 71 69 and 70 (97)

Appendix 4. EBSCO CINAHL search strategy

S40 S34 and S39 S39 S35 or S36 or S37 or S38 S38 TI ( bedsore* or bed sore* ) or AB ( bedsore* or bed sore* ) S37 TI decubitus or AB decubitus S36 TI ( pressure ulcer* or pressure sore* ) or AB ( pressure ulcer* or pressure sore* ) S35 (MH "Pressure Ulcer") S34 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 S33 TI trough* or AB trough* S32 TI ( heel* N2 lift* or heel* N2 float* or heel* N2 splint* or heel* N2 glove* or heel* N2 suspension or heel* N2 elevat* ) or AB ( heel* N2 lift* or heel* N2 float* or heel* N2 splint* or heel* N2 glove* or heel* N2 suspension or heel* N2 elevat* ) S31 TI heel* N2 device* or AB heel* N2 device* S30 TI heel* N2 protect* or AB heel* N2 protect* S29 TI heel* N2 pressure* or AB heel* N2 pressure* S28 TI ( foot N2 device* or feet N2 device* ) or AB ( foot N2 device* or feet N2 device* ) S27 TI ( foot N2 protect* or feet N2 protect* ) or AB ( foot N2 protect* or feet N2 protect* ) S26 TI ( foot N2 pressure* or feet N2 pressure* ) or AB ( foot N2 pressure* or feet N2 pressure* ) S25 TI ( contact cast* or walk* cast* ) or AB ( contact cast* or walk* cast* ) S24 TI ( aircast or scotchcast ) or AB ( aircast or scotchcast ) S23 TI ( orthos* or insole* ) or AB ( orthos* or insole* ) S22 TI ( orthotic device or orthotic therap* ) or AB ( orthotic device or orthotic therap* ) S21 (MH "Orthoses+") S20 TI ( footwear or foot wear ) or AB ( footwear or foot wear ) S19 TI ( shoe* or boot* ) or AB ( shoe* or boot* ) S18 (MH "Shoes") S17 TI elevat* N2 device* or AB elevat* N2 device* S16 TI static air or AB static air S15 TI air bag* or AB air bag* S14 TI foot waffle or AB foot waffle S13 TI ( sheepskin* or sheep skin* ) or AB ( sheepskin* or sheep skin* ) S12 TI ( air suspension or water suspension ) or AB ( air suspension or water suspension ) S11 TI ( constant N1 pressure* or alternat* N1 pressure* ) or AB ( constant N1 pressure* or alternat* N1 pressure* ) S10 TI low pressure support or AB low pressure support S9 TI pressure redistribution or AB pressure redistribution S8 TI pressure device* or AB pressure device* S7 TI pressure relie* or AB pressure relie* S6 TI ( gel or gels ) or AB ( gel or gels ) S5 TI ( pad or pads or padding ) or AB ( pad or pads or padding ) S4 TI ( foam* or cutfoam or overlay* ) or AB ( foam* or cutfoam or overlay* ) S3 TI ( mattress* or cushion* or pillow* ) or AB ( mattress* or cushion* or pillow* ) S2 TI ( bed or beds ) or AB ( bed or beds ) S1 (MH "Beds and Mattresses+")

Appendix 5. Criteria for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2008)

1. Was the allocation sequence randomly generated?

Low risk of bias

The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table; using a computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots.

High risk of bias

The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, for example: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; sequence generated by some rule based on date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by some rule based on hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear

Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘Low Risk’ or ‘High Risk’.

2. Was the treatment allocation adequately concealed?

Low risk of bias

Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially‐numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

High risk of bias

Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or nonopaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure.

Unclear

Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low Risk’ or ‘High Risk’. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement, for example if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed.

3. Blinding ‐ was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following:

No blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome and the outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following:

No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

Any one of the following:

Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low Risk’ or ‘High Risk’.

The study did not address this outcome.

4. Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following:

No missing outcome data.

Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias).

Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size.

Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following:

Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size.

‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation.

Potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear

Any one of the following:

Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of ‘Low Risk’ or ‘High Risk’ (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided).

The study did not address this outcome.

5. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Low risk of bias

Any of the following:

The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way.

The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon).

High risk of bias

Any one of the following:

Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported.

One or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified.

One or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect).

One or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis.

The study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Unclear

Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low Risk’ or ‘High Risk’. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category.

6. Other sources of potential bias

Low risk of bias

The study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

High risk of bias

There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or

stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); or

had extreme baseline imbalance; or

has been claimed to have been fraudulent; or

had some other problem.

Unclear

There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; or

insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Nimbus system compared with Cairwave system.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heel ulcer healed | 1 | 113 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.90, 2.45] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Russell 2000.

| Methods | RCT, study duration was originally planned to be 12 months but extended to 18 months. Patients were followed up till they healed, were discharged or died | |

| Participants | 141 patients in total, 113 with heel pressure ulcers (55 on one alternating mattress system, 58 on the other alternating mattress system). All participants were recruited from a health care of the elderly unit in a UK hospital, average age 84 years. Patients suffered from diseases such as cardiovascular, dementia, malignancy and orthopaedic problems | |

| Interventions | 1. Huntleigh Nimbus alternating mattress replacement (1 in 2 alternating cycle) and cushion 2. Pegasus Cairwave alternating mattress replacement (1 in 3 alternating cycle) and cushion. Both groups also had their pressure ulcers treated according to the Trust wound care formulary and the Tissue Viability nurses recommendations. Patients were turned according to the manufacturers recommendations: 4‐hourly for those assigned to the Nimbus system and 8‐hourly for those assigned to the Cairwave system or more often if requested by the participant or considered necessary by the nursing team |

|

| Outcomes | Completed study (healed, discharged or died) and comfort | |

| Notes | Full data extraction performed on personal correspondence from main author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sealed envelopes used |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It is impossible to blind participants or study personnel to treatment allocation as the differences in mattresses is visually evident. Outcome data for healing were collected by 3 research nurses. Monitoring of the data collection and protocol compliance was carried out by a team member who was 'blinded' to the statistical analysis. Comfort data were recorded by audit staff who were unaware of the differences in the mattresses |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | The author gives results which include and exclude those who died, however there was significant loss due to participants dying or being discharged from hospital. This was not addressed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The main aim was to compare the efficacy of the equipment for healing pressure ulcers. It is not clear why the outcome is described in terms of "completed study" |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No record of gender mix in each group or severity of pressure ulcer on admission to study |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Allman 1987a | Heels not included |

| Allman 1987b | Heels not included |

| Andrews 1989 | Not RCT |

| Bates Jenson 1998 | Not RCT |

| Bell 1993 | Not RCT |

| Benbow 1995 | Not RCT |

| Bennett 1998 | Heels not included |

| Blanco Blanco 2002 | Not treatment study |

| Bliss 1966 | Not treatment study |

| Bliss 1967 | Not treatment study |

| Bliss 1995 | No separate heel data |

| Braniff‐Matthews 1997 | Not treatment study |

| Branom 1999 | No separate heel data |

| Branom 2001 | Heels not included |

| Bridel‐Nixon 1997 | Heels not included |

| Brown 2001 | Not treatment study |

| Caley 1994 | Heels not included |

| Chaloner 2000 | Not treatment study |

| Cheneworth 1994 | Controlled clinical trial, not random allocation |

| Clark 2002 | Not an RCT |

| Collins 2002 | Not treatment study |

| Conine 1990a | Not treatment study |

| Conine 1990b | Not treatment study |

| Crook 1998 | Not treatment study |

| Cullum 2001 | Review: retrieved to follow up references |

| Day 1990 | Not RCT |

| Day 1993 | Not RCT |

| De Keyser 1994 | Not RCT |

| Devine 1995a | No separate heel data |

| Devine 1995b | No separate heel data |

| Ernst 2009 | Review, retrieved to follow up references |

| Evans 2000 | No separate heel data |

| Ewing 1964 | Not RCT |

| Ferrell 1993 | Heel data not available |

| Fleischer 1997 | Not RCT |

| Goldstone 1982 | Not treatment study |

| Gray 1998 | Not treatment study |

| Greer 1988 | Not RCT |

| Groen 1999 | No heel data |

| Hardin 2000 | Not treatment study |

| Henn 2004 | Not RCT |

| Johnson 1991 | Not RCT |

| Knight 1999 | No separate heel data |

| Knowles 1999 | Not RCT |

| Land 2000 | Duplicate study, no heels in study |

| Laurent 1997 | Not treatment study |

| Lazzara 1991 | No separate heel data |

| Marchand 1993 | Not RCT |

| Melland 1998 | Not RCT |

| Moody 1993 | No separate heel data |

| Mulder 1994 | Heel data not available |

| Munro 1989 | No separate heel data |

| Osterbrink 2005 | No separate heel data |

| Phillips 2000 | No separate heel data |

| Price 1999 | Not treatment study |

| Regan 2009 | Review, retrieved to follow up references |

| Russell 1998 | Conference presentation of included study |

| Russell 2000a | No heels included |

| Russell 2003 | No separate heel data |

| Scott 1995 | Not RCT |

| Sharp 2007 | Not RCT |

| Smith 1995 | Review: retrieved to check references |

| Soppi 2004 | Not treatment study |

| Strauss 1991 | No healing outcomes |

| Taylor 1999 | Heel data not available |

| Tewes 1993 | Review, not retrieved as not English language |

| Thomas 2001a | Review, retrieved for references |

| Thomas 2001b | Review, retrieved for references |

| Thomas 2006 | Review, retrieved for references |

| Thomas 2007 | Review, retrieved for references |

| Whittingham 1999 | Not treatment |

| Yang 2007 | Review: tried to retrieve but unable to find translator |

| Young 1992 | Review, retrieved for references |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Contributions of authors

The protocol was written by Elizabeth McGinnis and reviewed by Nikki Stubbs. The two review authors carried out study selection and data extraction. The review was written by Elizabeth McGinnis and reviewed by Nikki Stubbs. Elizabeth McGinnes updated the review.

Contributions of editorial base

Nicky Cullum: edited the review, advised on methodology, interpretation and review content. Approved the final review prior to submission. Sally Bell‐Syer: co‐ordinated the editorial process. Advised on methodology, interpretation and content. Edited and copy edited the review and the updated review. Ruth Foxlee: designed the search strategy, ran the searches and edited the search methods section. Rachel Richardson:checked the updated review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Leeds North West PCT, Leeds, UK.

Charitable Trustees, LeedsTeaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK.

Smith & Nephew Foundation/ Multiple Sclerosis Society, UK.

External sources

Department of Health Sciences, University of York, UK.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the sole funder of the Cochrane Wounds Review Group, UK.

NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research, UK.

Declarations of interest

Nikki Stubbs receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP‐PG‐0407‐10428). The views expressed in this review are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Nikki Stubbs has received funding from Pharmaceutical companies to support training and education events in the service and payments have been received by the author for non product related educational sessions. These have been unrelated to the subject matter of this systematic review and have never been in support or in pursuit of the promotion of products.

Elizabeth McGinnes has been supported in her academic studies by the following charitable organisations: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust Charitable Trustees and the Smith & Nephew Foundation/ Multiple Sclerosis Society. The systematic review was part of her thesis.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Russell 2000 {published and unpublished data}

- Russell L, Reynolds TM. Randomised controlled trial of two pressure‐relieving systems. Journal of Wound Care 2000;9(2):52‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Allman 1987a {published data only}

- Allman RM, Keruly JC, Smith CR. Cost effectiveness of air‐fluidized beds versus conventional therapy for pressure sores. Clinical Research 1987;35(3):A728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Allman 1987b {published data only}

- Allman RM, Walker JM, Hart MK, Laprade CA, Noel LB, Smith CR. Air‐fluidized beds or conventional therapy for pressure sores. A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987;107(5):641‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Andrews 1989 {published data only}

- Andrews J, Balai R. The prevention and treatment of pressure sores by use of pressure distributing mattresses. Care Science and Practice 1989;7(3):72‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bates Jenson 1998 {published data only}

- Bates Jenson BM. A quantitative analysis of wound characteristics as early predictors of healing in pressure sores. Dissertation. University of California, LosAngeles 1998.

Bell 1993 {published data only}

- Bell JC, Matthew SD. Results of a clinical investigation of four pressure reduction replacement mattresses. Journal of ET Nursing 1993;20(5):204‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benbow 1995 {published data only}

- Benbow M. Easing the pressure. Nursing Times 1995;91(47):64,68,70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bennett 1998 {published data only}

- Bennett RG, Baran PJ, DeVone LV, Bacetti H, Kristo B, Tayback M, et al. Low air loss hydrotherapy versus standard care for incontinent hospitalized participants. Journal of American Geriatric Society 1998;46(5):569‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blanco Blanco 2002 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Blanco Blanco J, Ballester Torralba J, Rueda Lopez J, Torra i Bou JE. Comparative study of the use of a heel protecting bandage and a special hydrocellular dressing in the prevention of pressure ulcers in elderly participants. 12th Conference of the EWMA, Granada, Spain, May 23‐25. 2002:114.

Bliss 1966 {published data only}

- Bliss MR, McLaren R, Exton Smith AN. Mattresses for preventing pressure sores in geriatric participants. Monthly Bulletin of the Ministry of Health and Public Health Laboratory Service 1966;25:238‐68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bliss 1967 {published data only}

- Bliss MR, McLaren R, Exton Smith AN. Preventing pressure sores in hospital: controlled trial of a large‐celled ripple mattress. British Medical Journal 1967;67(1):394‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bliss 1995 {published data only}

- Bliss MR. Preventing pressure sores in elderly participants: a comparison of seven mattress overlays. Age and Aging 1995;24(4):297‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Braniff‐Matthews 1997 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Braniff‐Matthews C, Rhodes J. Prevention versus treatment: long‐term management of care. European Wound Management Association Conference; 1997, 27‐29 April; Milan, Italy. 1997:6.

Branom 1999 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Branom R, Knox L. Low air loss vs non powered/dynamic surfaces in wound management. 31st Annual Wound, Ostomy and Continence Conference: Minneapolis, MN, USA. 1999:483.

Branom 2001 {published data only}

- Branom R, Rappl LM. 'Constant force technology' versus low air loss therapy in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Ostomy/Wound Management 2001;47(9):38‐46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bridel‐Nixon 1997 {published data only}

- Bridel‐Nixon J, McElvenny D, Brown J, Mason S. A randomized controlled trial using a double‐triangular sequential design: methodology and management issues. European Wound Management Association Conference; 1997, 27‐29 April; Milan, Italy. 1997:65‐66.

Brown 2001 {published data only}

- Brown SJ. Bed surfaces and pressure sore prevention: an abridged report. Orthopaedic Nursing 2001;20(4):38‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caley 1994 {unpublished data only}

- Caley L, Jones S, Freer J, Muller JS. Two types of low air loss therapy. Personal Communication 1994:378‐380.

Chaloner 2000 {published data only}

- Chaloner D. A prospective controlled comparison between two dynamic alternating mattress replacement systems within a community setting. 9th European Conference on Advances in Wound Management: Harrogate, UK, November 9‐11 1999. 2000:9‐11.

Cheneworth 1994 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Cheneworth CC, Hagglund KH, Valmassoi B, Brannon C. Portrait of practice: healing of heel ulcers. Advances in Wound Care 1994;7(2):44‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clark 2002 {published data only}

- Clark M, Benbow M, Butcher M, Gebhardt K, Teasley G, Zoller J. Collecting pressure ulcer prevention and management outcomes: 1. British Journal of Nursing 2002;11(4):230, 232, 234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2002 {published data only}

- Collins AS, Todd R, McCoy A, Deitz G, Pruitt D, Garner M, et al. Stride right. Nursing Management 2002;33(9):33‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conine 1990a {published data only}

- Conine TA, Daechsel D, Lau MS. The role of alternating air and Silicore overlays in preventing decubitus ulcers. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 1990;13(1):57‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conine 1990b {published data only}

- Conine TA, Daechse lD, Choi AK, Lau MS. Costs and acceptability of two special overlays for the prevention of pressure sores. Rehabilitation Nursing 1990;15(3):133‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crook 1998 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Crook H. Using a low‐pressure inflatable support system in the prevention of pressure sores in orthopaedic participants. European Wound Management Association Conference; 1998 November; Harrogate, UK. 1998:24.

Cullum 2001 {published data only}

Day 1990 {published data only}

- Day AL, Leonard FE, Racz TM. Developing a research approach for the treatment of pressure ulcers. Ostomy/Wound Management 1990 Nov‐Dec;31:30‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Day 1993 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Day A, Leonard F. Seeking quality care for participants with pressure ulcers. Decubitus 1993;6(1):32‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Keyser 1994 {published data only}

- Keyser G, Dejaeger E, DeMeyst H, Eders GC. Pressure‐reducing effects of heel protectors. Advanced Wound Care 1994;7(4):30‐2, 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Devine 1995a {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Devine B. Alternating pressure air mattresses in the management of established pressure sores. Journal of Tissue Viability 1995;5(3):94‐8. [Google Scholar]

Devine 1995b {published data only}

- Devine BL. Alternating pressure air mattresses in the management of established pressure sores. Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Advances in Wound Management: Harrogate, UK, November 21‐24. 1995:19‐20.

Ernst 2009 {published data only}

Evans 2000 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Evans D, Land L, Geary A. A clinical evaluation of the Nimbus 3 alternating pressure mattress replacement system. Journal of Wound Care 2000;9(4):181‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ewing 1964 {published data only}

- Ewing MR, Garrow C, Pressley TA, Ashley C, Kinsella NM. Further experiences in the use of sheepskins as an aid to nursing. Medical Journal of Australia 1964;2:139‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferrell 1993 {published data only}

- Ferrell B, Keeler E, Siu A, Ahn S, Osterweil D. Cost‐effectivness of low‐air‐loss beds for treatment of pressure ulcers. Journal of Gerontology 1995;50A(3):M141‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BA, Osterweil D, Christenson P. A randomised trial of low air loss beds for treatment of pressure ulcers. JAMA 1993;269(4):494‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fleischer 1997 {published data only}

- Fleischer I, Bryant D. Evaluating replacement mattresses. Nursing Management 1997;28(8):38‐42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldstone 1982 {published data only}

- Goldstone LA, Norris M, O'Reilly M, White J. A clinical trial of a bead bed system for the prevention of pressure sores in elderly orthopaedic participants. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1982;7(6):545‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gray 1998 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Gray D, Smith M. A randomized controlled trial of two pressure‐reducing foam mattresses. European Wound Management Association Conference; 1998 November; Harrogate, UK. 1998:4.

Greer 1988 {published data only}

- Greer DM, Morris J, Walsh NE, Glenn AM, Keppler J. Cost‐effectiveness and efficacy of air‐fluidized therapy in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Journal of Enterostomal Therapy 1988;15(6):247‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Groen 1999 {published data only}

- Groen HW, Groenier KH, Schuling J. Comparative study of a foam mattress and a water mattress. Journal of Wound Care 1999;8(7):333‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hardin 2000 {published data only}

- Hardin JB, Cronin SN, Cahill K. Comparison of the effectiveness of two pressure‐relieving surfaces: low‐air‐loss versus static fluid. Ostomy/Wound Management 2000;49(9):50‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henn 2004 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Henn G, Russell L, Towns A, Taylor H. A Two‐centre prospective study to determine the utility of a dynamic mattress and mattress overlay. 2nd World Union of Wound Healing Societies Meeting; 2004 July 8‐13; Paris, France. 2004:54.

Johnson 1991 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Johnson G, Daily C, Francisus V. A clinical study of hospital replacement mattresses. Journal of ET Nursing 1991;18(5):153‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knight 1999 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Knight M, Simpson J, Fear‐Price M. An evaluation of pressure‐reducing overlay mattresses in the community situation. 9th European Conference on Advances in Wound Management; November 9‐11; Harrogate, UK. 1999:25.

Knowles 1999 {published data only}

- Knowles C, Horsey I. Clinical evaluation of an electronic pressure‐relieving mattress. British Journal of Nursing 1999;8(20):1392‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Land 2000 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Land L, Evans D, Geary A, Taylor C. A clinical evaluation of an alternating‐pressure mattress replacement system in hospital and residential care settings. Journal of Tissue Viability 2000;10(1):6‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laurent 1997 {published data only}

- Laurent S. Effectiveness of pressure decreasing mattresses in cardiovascular surgery participants: a controlled clinical trial. 3rd European Conference for Nurse Managers; 1997 Oct; Brussels, Belgium. 1997.

Lazzara 1991 {published data only}

- Lazzara DJ, Buschmann MT. Prevention of pressure ulcers in elderly nursing home residents: are special support surfaces the answer?. Decubitus 1991;4(4):42‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marchand 1993 {published data only}

- Marchand AC, Lidowski H. Reassessment of the use of genuine sheepskin for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. Decubitus 1993;6(1):44‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melland 1998 {published data only}

- Melland HI, Langemo D, Hanson D, Olson B, Hunter S. Clinical trial of the Freedom bed. Prairie Rose 1998;67(2):11a‐12a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moody 1993 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Moody M. The role of a pressure relief dressing in the prevention and treatment of pressure sores. 3rd European Conference on Advances in Wound Management; October 19‐22, 1993; Harrogate, UK. 1994:174.

Mulder 1994 {published data only}

- Mulder GD, Taro N, Seeley J, Andrews K. A study of pressure ulcer response to low air loss beds vs. conventional treatment. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology 1994;2(3):87‐91. [Google Scholar]

Munro 1989 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Munro BH, Brown L, Heitman BB. Pressure ulcers: one bed or another?. Geriatric Nursing 1989;10(4):190‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Osterbrink 2005 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Osterbrink J, Mayer H, Schroder G. Clinical evaluation of the effectiveness of a multimodal static pressure relieving device. European Wound Management Association Conference; 2005, 15‐17 September; Stuttgart, Germany. 2005; Vol. Thur 14:00‐15:30; V26‐6:73.

Phillips 2000 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Phillips L. Cost‐effective strategy for managing pressure ulcers in critical care: a prospective, non‐randomised, cohort study. Journal of Tissue Viability 2000;10(Suppl 3):2‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Price 1999 {published data only}

- Price P, Bale S, Newcombe R, Harding K. Challenging the pressure sore paradigm. Journal of Wound Care 1999;8(4):187‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Regan 2009 {published data only}

- Regan MA, Teasell RW, Wolfe DL, Keast D, Mortenson WB, Aubut JL. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2009;90(2):213‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Russell 1998 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Russell L. Randomized comparative clinical trial of the Pegasus Cairwave mattress and Proactive seating cushion and the Huntleigh Nimbus III mattress and Alpha Transcell seating cushion. European Wound Management Association and Journal of Wound Care Autumn Conference; November 9‐11; Harrogate, UK. 1998:4.

Russell 2000a {published data only}

- Russell L, Reynolds T, Carr J, Evans A, Holmes M. A comparison of healing rates on two pressure‐relieving systems. British Journal of Nursing 2000;9(22):2270‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell L, Reynolds T, Carr J, Evans A, Holmes M. Randomised controlled trial of two pressure‐relieving systems. Journal of Wound Care 2000;9(2):52‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Russell 2003 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Russell L, Reynolds TM, Towns A, Worth W, Greenman A, Turner R. Product evaluation. Randomized comparison trial of the RIK and the Nimbus 3 mattresses. British Journal of Nursing 2003;12(4):256‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scott 1995 {published data only}

- Scott F. Easing the pressure for hip fracture participants. Nursing Times 1995;91(29):20‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharp 2007 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Sharp A. Pilot study to compare the incidence of pressure ulceration on two therapeutic support surfaces in elderly care. 17th Conference of the European Wound Managment Association; May 2‐4, 2007; Glasgow, Scotland. 2007:Oral presentation 114, 73.

Smith 1995 {published data only}

- Smith DM. Pressure ulcers in the nursing home. Annals of Internal Medicine 1995;123(6):433‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soppi 2004 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Soppi E, Takala J. Novel carital speciality mattress in the management of pressure sores. 2nd World Union of Wound Healing Societies Meeting:Paris, France, July 8‐13. 2004:X023.

Strauss 1991 {published data only}

- Strauss MJ, Gong J, Gary BD, Kalsbeek WD, Spear S. The cost of home air‐fluidized therapy for pressure sores: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Family Practice 1991;33(1):52‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Taylor 1999 {published data only}

- Taylor L. Evaluating the Pegasus Trinova: a data hierarchy approach. British Journal of Nursing 1999;8(12):771‐4, 776‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tewes 1993 {published data only}

- Tewes M. Prevention and treatment of pressure sores ‐ a neglected research subject. An overview of clinically controlled studies in the period 1987‐91. Vård i Norden 1993;13(2):4‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomas 2001a {published data only}

- Thomas D. Prevention and management of pressure ulcers. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology 2001;11:115‐30. [Google Scholar]

Thomas 2001b {published data only}

- Thomas DR. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: what works? what doesn't?. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2001;68:704‐7, 710‐4, 717‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]