To the Editor:

Castleman disease (CD) is a rare and heterogeneous lymphoproliferative disorder with shared lymph node (LN) histology.1 While multicentric CD (MCD) involves multiple enlarged LNs, systemic inflammation, and multi-organ failure, unicentric CD (UCD) involves a single enlarged LN or region of LNs and few to no symptoms.1 Though compressive symptoms are the best-described clinical manifestation of UCD, some patients can have an MCD-like inflammatory syndrome.2 In UCD, complete surgical excision (herein abbreviated “CLE”) of the enlarged LN(s) is reported to induce complete remission in ~96.0% of patients.1 Despite reports of high response rates to CLE, there have been anecdotal reports of unresolved symptoms post-CLE by patients in the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN), a non-profit research and patient advocacy organization, as well as by CDCN-affiliated physicians. Unfortunately, there is limited published data on unresolved symptoms in UCD patients following complete surgical excision.3 ACCELERATE, a longitudinal CD natural history study, is well-positioned to systematically investigate the prevalence of ongoing symptoms in UCD patients after CLE. We investigated real-world data from ACCELERATE and utilized patient administered surveys to characterize UCD symptoms before and after CLE to determine the prevalence of ongoing symptoms.

Patients included in the study enrolled into ACCELERATE between October 2016 and November 2020. Ninety-nine patients who self-reported UCD or were diagnosed with UCD by their physicians were reviewed by an expert panel of CD clinicians and pathologists to confirm the likelihood of a UCD diagnosis based on diagnostic pathology slides and extensive medical data. In total, 60 patients had a confirmed UCD diagnosis, 22 likely had another disease (i.e., another reactive/malignant process) and 17 possibly had UCD but lacked pathology slides for confirmation. Analyses were conducted on the 60 confirmed UCD patients. All 99 patients were also invited to participate in validated surveys (EQ-5D-5L, CD Symptom Score) and an additional questionnaire regarding ongoing symptoms.

Among the 60 UCD patients, there were 15 males (25.0%) and 45 females (75.0%); patients were predominantly white (93.3%). Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 39.2 (12.9) years, and the mean (SD) follow-up was 3.0 (3.9) years. Most patients demonstrated hyaline-vascular histopathology (85.0%, n=51) (Supplemental Table 1). Among 53 patients with assessable data at disease onset, 28 (52.8%) presented asymptomatically, including 22 (78.6%) with no abnormal labs. Twenty-five (47.2%) patients presented with constitutional symptoms, including fatigue (46.3%), night sweats (29.7%), unintentional weight loss (16.3%), and/or fever (9.8%). Apart from elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), which was abnormal in 4/7 (57.1%) patients in which it was measured, no other labs were abnormal in more than 50.0% of patients and only 30.0% (16/53) of patients had laboratory abnormalities at presentation. Of note, two patients demonstrated markedly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels of 139.7 mg/L and 74.5 mg/L, and one patient had a markedly high ESR of 95 mm/hr.

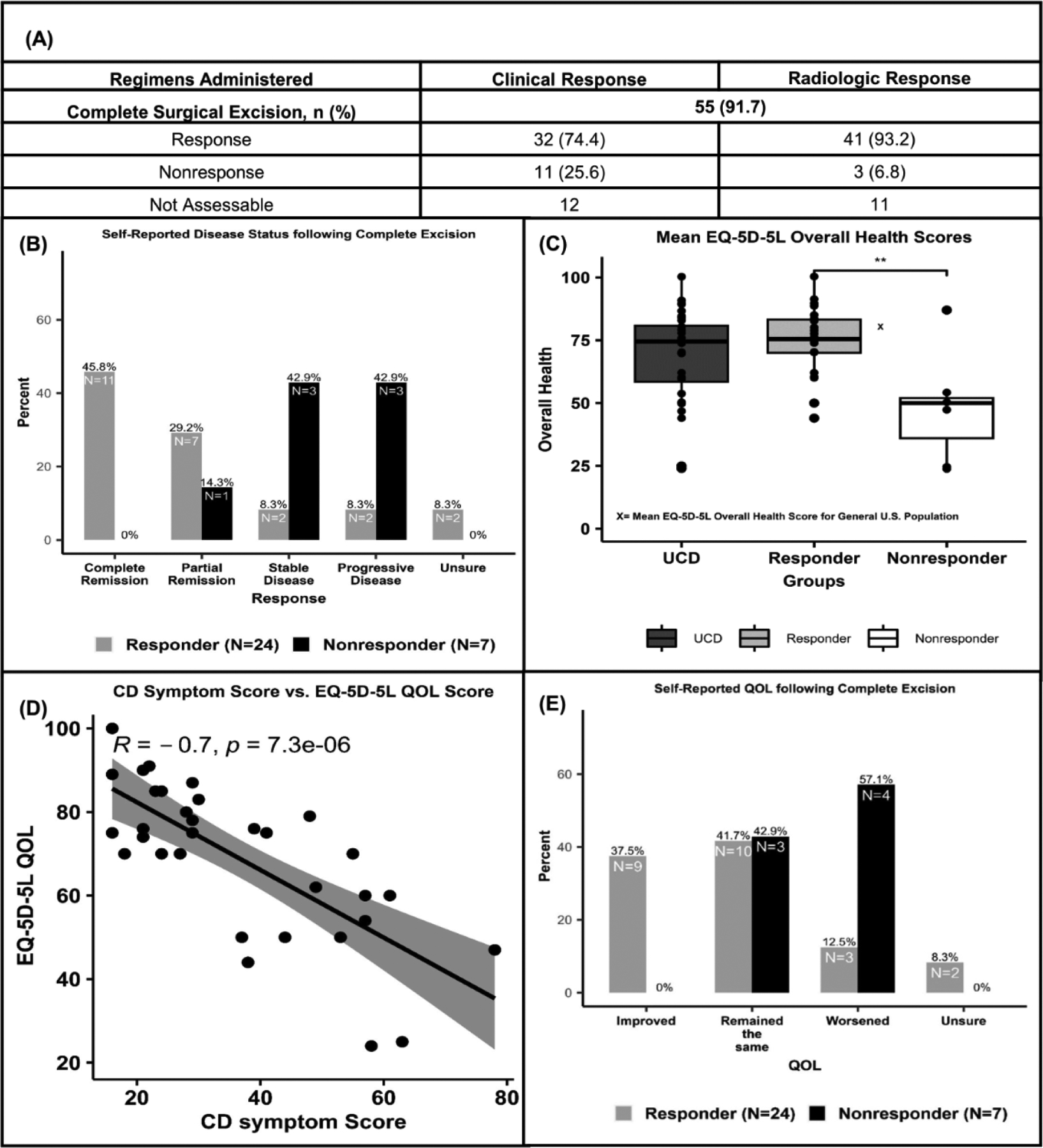

We examined the efficacy of CLE in this cohort from medical record data, both clinically and radiologically. 55/60 (91.7%) received a CLE and 53/55 (96.4%) patients had sufficient data to assess a clinical and/or radiologic response (Figure 1, Panel A). While 41/44 (93.2%) patients demonstrated radiologic resolution to CLE, only 32/43 (74.4%) patients with sufficient clinical data had clinical response. Among the five patients where CLE was not performed due to the size/location of the mass, an incomplete surgical excision was performed instead, in which 4/5 (80.0%) patients did not achieve a clinical response (Supplemental Table 2). We found a similar proportion of patients with symptoms at presentation between CLE responders (n=32) and non-responders (n=11) (Supplemental Table 3). 7/11 (63.6%) non-responders presented with constitutional symptoms compared to 17/32 (53.1%) of CLE responders. In both groups, fatigue and night sweats were the most common symptoms. As expected, we found that 7/11 (63.6%) of CLE non-responders received additional regimens post-CLE, compared to only 6/32 (18.8%) CLE responders (Supplemental Figure 2). For CLE non-responders, no regimen resulted in full clinical remission. While CLE induced a clinical response in most patients, the response rate in this real-world ACCELERATE cohort (74.4%) is lower than that reported in the literature (~96.0%).1

Figure 1.

Panel A. Response to complete surgical excision for 55 unicentric Castleman disease patients with assessable data.

Panel B. 0% of non-responders report improvement in quality of life following complete surgical excision. 57.1% report a worsening of their quality of life.

Panel C. Self-reported assessment of disease status in patients following complete surgical excision.

Panel D. Non-responders report unhealthier EQ-5D-5L quality of life scores than responders (** P = 0.0002).

Panel E. Castleman disease symptom scores have a strong negative correlation with self-reported quality of life scores.

Due to the seemingly greater symptom burden in this UCD cohort and lower response rates to CLE, we investigated symptoms pre- and post-CLE as well as the patient experience post-CLE from our 60 confirmed UCD patients. Among the 60 confirmed UCD patients, 32 (53.3%) completed the surveys, of which 31 (96.9%) received a CLE. 25 (78.1%) of these patients reported symptoms at presentation, with fatigue (n=21, 65.6%), generalized pain (n=17, 53.1%), and night sweats (n=16, 50.0%) among the most commonly reported symptoms (Supplemental Figure 1). In evaluating ongoing symptoms, the mean (SD) time elapsed since CLE for the 31 respondents who received a CLE was 4.7 (3.8) years, with 93.5% (n=29) of patients responding greater than one year post-CLE. 21/31 (67.7%) patients reported ongoing symptoms post-CLE (Supplemental Figure 3). The most commonly reported ongoing symptoms were fatigue (62.5%) and night sweats (46.8%). 14/24 (58.3%) CLE responders reported ongoing symptoms, compared to 7/7 (100.0%) CLE non-responders (Supplemental Table 4). 6/7 (85.7%) CLE non-responders reported stable or worsening disease post-CLE, compared to only 2/24 (8.3%) responders (Figure 1, Panel B).

Since ongoing symptoms could arise from other comorbidities, we examined the prevalence of comorbidities in this cohort. The most frequent comorbidities included gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, and obesity; we did not observe any substantial differences in the prevalence of these comorbidities between CLE responders and non-responders (Supplemental Table 5). Considering that active ongoing symptoms may impact quality of life (QOL), we assessed general QOL among UCD patients using the EQ-5D-5L, a quantitative tool to measure health outcomes. Across all survey respondents (n=32), we found a mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L QOL score, which ranges from 0–100 with 0 being worst imaginable health and 100 being the best, of 68.8 (18.3). Patients categorized as CLE non-responders reported a mean (SD) QOL score of 48.1 (22.6), which was significantly lower than the 74.8 (13.0) score for the responder group (t = - 4.13, p = 0.0002) (Figure 1, Panel C). The mean QOL score reported by responders was comparable to that of a representative sample of the U.S. population (80.4), whereas the non-responder group had a lower QOL (not statistically tested).4 We assessed the correlation between the EQ-5D-5L QOL score and the CD symptom score, a survey used to evaluate CD symptoms actively experienced by patients. In this cohort, the EQ-5D-5L QOL score was strongly negatively correlated with the CD symptom score (spearman, r=−0.7, p=7.3 × 10−6), suggesting that a lower QOL is associated with active CD symptoms (Figure 1, Panel D). Next, we asked whether patients experienced an improvement in perceived QOL post-CLE. 9/24 (37.5%) responders reported an improvement in QOL following CLE, compared to 0/7 (0.0%) non-responders. Likewise, 3/24 (12.5%) responders felt their QOL decreased post-CLE, compared to 4/7 (57.1%) non-responders (Figure 1, Panel E). Overall, these data indicate that some UCD patients report continued symptoms and even a decline in their QOL following CLE.

In this study, we utilized longitudinal medical record data and validated surveys to demonstrate that ACCELERATE UCD patients experience higher than expected symptom burden at presentation and that ongoing symptoms may exist in a subset of UCD patients despite CLE. Though CLE was less effective in this cohort than has been reported in the literature, our data support it as the first-line therapy for UCD.1,2 We observed a clinical response in 32/53 (74.4%) patients, which is marginally lower than that reported in past literature reviews (~96.0%).1

There are several limitations to this study. First, medical registries introduce selection bias from their observational design and smaller sample sizes.5 Given that patients self-enroll in ACCELERATE, it is likely that enrollment biases result in this cohort being over-represented with symptomatic patients, who are more likely to engage in help-seeking behavior.5 Additionally, patients with quickly resected asymptomatic disease are likely under-represented in ACCELERATE. Together, these may explain the high proportion of symptomatic patients and lower CLE response rates in this cohort. Next, real-world data can complicate the systematic understanding of treatment response. To address this, we defined strict, empiric guidelines for assessing regimen response, and had each regimen reviewed and adjudicated for consistency. Last, survey data are also susceptible to bias. Patients with a higher disease burden have more incentives to voluntarily participate in surveys, resulting in data being skewed towards unhealthier values.6 Medical record data can also create difficulty in assessing the severity of symptoms present since it depends heavily on a clinician’s descriptive documentation. While it is difficult to deduce whether the reported ongoing symptoms are related to UCD or not, our data suggests that further investigation is warranted and that patients reporting ongoing symptoms should be recognized and fully evaluated for alternative diagnoses, co-morbidities, and/or CD-directed treatments. These data suggest that a subset of UCD patients do not respond to CLE and may experience a lower QOL post-CLE, highlighting a possible unmet medical need within this population. Careful review of medical history for other potential causes of ongoing symptoms is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the patients and their families for their participation in the ACCELERATE registry. We wish to thank the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) and the ACCELERATE Registry team for their support. We wish to thank the volunteers for the CDCN who have supported this research, including Mary Zuccato and Mileva Repasky. We wish to thank Shawnee Bernstein, Nathan Hersh, Gerard Hoeltzel, and Jeremy Zuckerberg for their contributions to this study. We wish to thank Faizaan Ahkter, Erin Napier, Eric Haljasmaa, Katherine Floess, Mark-Avery Tamakloe, Victoria Powers, Alexander Gorzewski, Johnson Khor, Reece Williams, Jasira Ziglar, Amy Liu, Natalie Mango, Criswell Lavery, and Bridget Austin.

Funding

The ACCELERATE natural history registry has received funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals (2016 — 2018), EUSA Pharma, LLC (US), which has merged with Recordati Rare Diseases Inc. (2018 — 2022), and is now supported by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (R01FD007632) (2022 — Present). D.C.F has also received research funding relevant to this project from the NIH National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute (R01HL141408).

Competing Interests

D.C.F. has received research funding for the ACCELERATE registry from EUSA Pharma and consulting fees from EUSA Pharma, and Pfizer provides a study drug with no associated research funding for the clinical trial of sirolimus (NCT03933904). D.C.F. has two provisional patents pending related to the diagnosis and treatment of iMCD. A.B. has served on a EUSA Pharma Castleman Disease Advisory Board. G.S. has received Speakers Bureau fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. D.A. has served on the Castleman Disease Medical Advisory Board for EUSA Pharma and from 03/2023 – present serves as the advisory board co-chair. F.v.R has received consulting fees from EUSA Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm, and Takeda and has received research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Bristol Myers Squibb. M.J.L. serves on the advisory board for EUSA Pharma and Secura Bio, Inc., serves as an honorarium speaker for Southeastern Lymphoma Symposium, and receives consulting fees from University of Pennsylvania. J.D.B. has received consulting fees from EUSA Pharma. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval

The ACCELERATE natural history registry has received ethical approval from the University of Pennsylvania IRB.

Data Availability

All source data reported in this study is available by contacting the ACCELERATE team at accelerate@uphs.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.van Rhee F, Oksenhendler E, Srkalovic G, et al. International evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. 2020;4(23):6039–6050. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang M yan, Jia M nan, Chen J, et al. UCD with MCD-like inflammatory state: surgical excision is highly effective. Blood Adv. 2021;5(1):122–128. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren N, Ding L, Jia E, Xue J. Recurrence in unicentric castleman’s disease postoperatively: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0334-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Quality of Life Research. 2021;30(3):803–816. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02650-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwood JM, Marshall RJ, Tin ST, Barrios MEP, Harvey VJ. Bias in survival estimates created by a requirement for consent to enter a clinical breast cancer registry. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;58:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda T, Marche H, Grosclaude P, Matsuda T. Participation Behavior of Bladder Cancer Survivors in a Medical Follow-Up Survey on Quality of Life in France. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;19(4):313–321. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000024703.54660.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All source data reported in this study is available by contacting the ACCELERATE team at accelerate@uphs.upenn.edu.