Significance

CO2reduction into CO, CH4, etc., can lower the atmospheric CO2concentration and provide carbon-neutral energy simultaneously, attracting scientists to design high-performance catalytic systems to facilitate this process. Molecular catalysis based on metal complexes is appealing for their well-defined structures which allow the rational optimizations by synthetic efforts and facile characterization of reaction intermediates. The chromium-based molecular catalysts for CO2reduction are still rare, leading to their underexplored design strategies and mechanistic insights. Herein, we deliberately used a quaterpyridine ligand to support the CrIIIcenter, affording a very efficient molecular electrocatalyst which outperforms the Cr-based precedents. Based on this promising catalyst, we have characterized a series of key intermediates to reveal its mechanism by various experimental techniques and calculations.

Keywords: CO2 reduction, molecular catalysis, chromium complex, CO binding, mechanism

Abstract

Design tactics and mechanistic studies both remain as fundamental challenges during the exploitations of earth-abundant molecular electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction, especially for the rarely studied Cr-based ones. Herein, a quaterpyridyl CrIII catalyst is found to be highly active for CO2 electroreduction to CO with 99.8% Faradaic efficiency in DMF/phenol medium. A nearly one order of magnitude higher turnover frequency (86.6 s−1) over the documented Cr-based catalysts (<10 s−1) can be achieved at an applied overpotential of only 190 mV which is generally 300 mV lower than these precedents. Such a high performance at this low driving force originates from the metal–ligand cooperativity that stabilizes the low-valent intermediates and serves as an efficient electron reservoir. Moreover, a synergy of electrochemistry, spectroelectrochemistry, electron paramagnetic resonance, and quantum chemical calculations allows to characterize the key CrII, CrI, Cr0, and CO-bound Cr0 intermediates as well as to verify the catalytic mechanism.

CO2 reduction is a versatile reaction for both relieving global warming and providing carbon-neutral, renewable fuels (1–3). To address the efficiency and selectivity issues in CO2 reduction, molecular catalysts, mainly transition metal complexes, are promising candidates; their well-defined structures are amenable to rational optimizations via synthetic means as well as kinetic and spectroscopic investigations on the catalytic intermediates that govern their mechanisms (4–7). Moreover, the molecular catalysts based on earth-abundant metals are appealing for their ease in lowering the expense for large-scale applications (8–10). In this context, major development has been made in designing the molecular catalysts featuring 3d transition metal centers like Mn (7, 11), Fe (12, 13), Co (14, 15), Ni (16–18), and Cu (6), while the utilizations of Cr (19–22), along with its congeners Mo (23–25) and W (25), are rather underexplored. The pioneering works were mainly contributed by Machan’s lab, where a family of tetradentate ligands consisting of mixed N/O donors and polypyridyl backbones has been developed to chelate CrIII for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (19–22). However, a more indicative design principle for the Cr-based molecular catalysts in CO2 reduction is still elusive, demanding novel design strategies and in-depth mechanistic investigations. We herein employ a quaterpyridyl ligand to coordinate the CrIII center, affording [Cr(qpy)(Cl)2]Cl (CrQPY, qpy = 2,2′:6′,2″:6″,2‴-quaterpyridine; Fig. 1 A, Inset) as a high-performance molecular catalyst for CO2 electroreduction to CO with near 100% Faradaic efficiency. Impressively, CrQPY exhibits a record-high turnover frequency (TOF) of 86.6 s−1 at a 300 mV lower applied overpotential in comparison with the Cr-based precedents (Table 1). Detailed electrochemical, spectroscopic, and computational studies have been performed to characterize the electronic structures of the key reactive intermediates, including CrII, CrI, Cr0, and Cr0-CO species which were rarely investigated before for the Cr-based molecular electrocatalyst in CO2 reduction. These mechanistic insights indicate that such a large TOF at this low overpotential of CrQPY is attributable to the use of N4 quaterpyridyl ligand which stabilizes low-valent intermediates and acts as an ideal electron reservoir, showing advantages over the Cr-based precedents with mixed N/O donors.

Fig. 1.

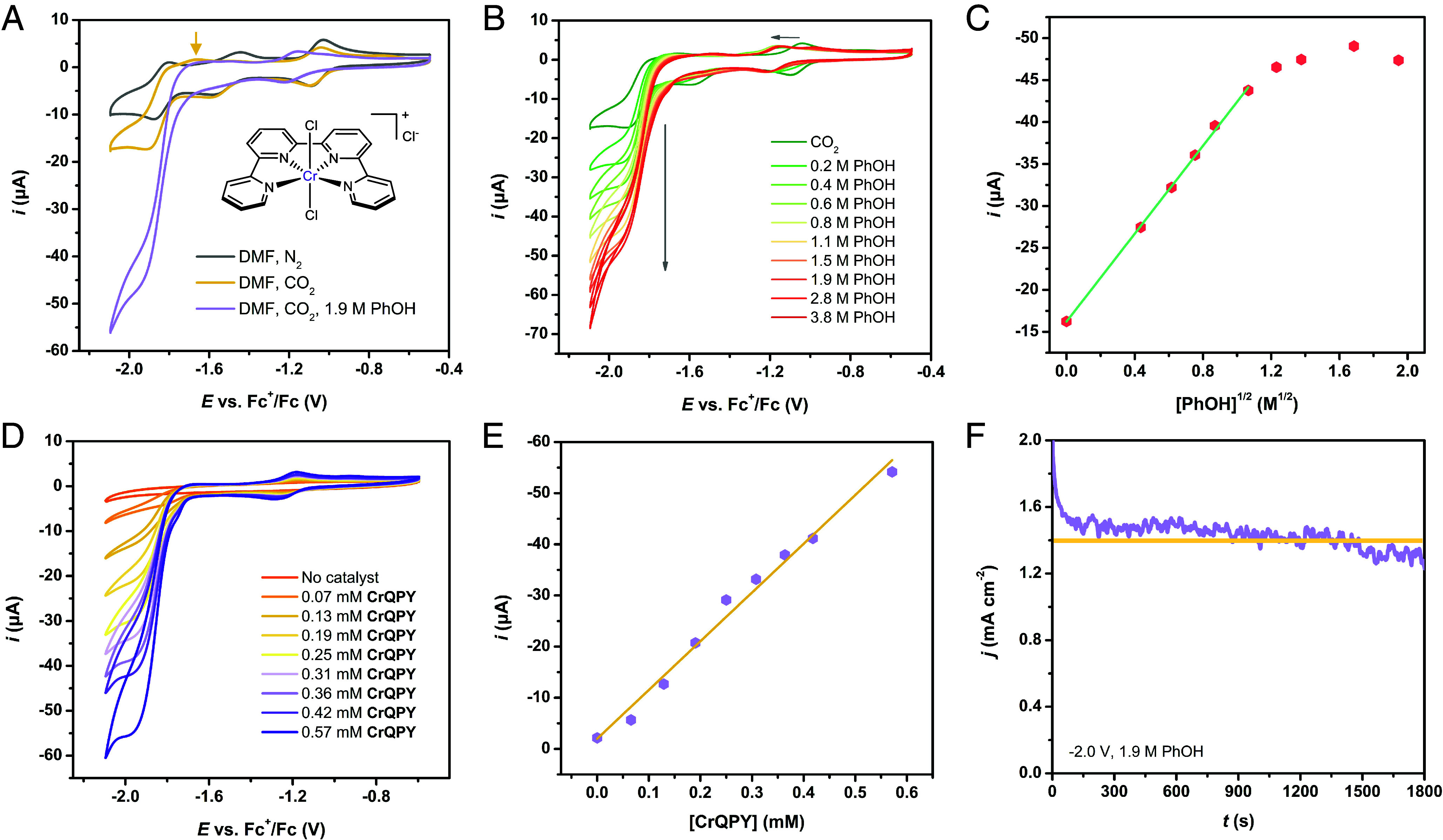

(A) CVs of 0.5 mM CrQPY under Ar (black), CO2 (gold), or CO2 with 1.9 M PhOH (violet). Inset: Chemical structure of CrQPY. (B) CVs of 0.5 mM CrQPY with varying [PhOH] under CO2. (C) Plot of current at −1.95 V versus the square root of [PhOH]. (D) CVs of varying [CrQPY] with 1.9 M PhOH under CO2. (E) Plot of current at −1.95 V versus [CrQPY]. General CV conditions: 3 mm GC disk working electrode, 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 DMF solution at 0.05 V s−1 scan rate. (F) CPE at −2.00 V with 0.5 mM CrQPY with 1.9 M PhOH at a GC plate (0.5 cm2) under stirring, giving Q = 2.05 C and a CO yield of 10.4 μmol during 30 min.

Table 1.

Performances of Cr-based molecular electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction to CO*

| Entry | Catalyst | Medium | Eapp (V) | FECO (%) | TOF (s−1)† | TON† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (this work) | CrQPY | DMF/PhOH (1.9 M) | −2.00 | 99.8 ± 4.0 | 86.6 | 1.56 × 105 |

| 2 (19) | Cr(tBudhbpy)Cl(H2O) | DMF/PhOH (0.62 M) | −2.10 | 96 ± 8 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 3 (20, 22) | DMF/PhOH (0.6 M) | −2.30 | 111 ± 14 | 7.12 | 1.42 × 105 | |

| 4 (21) | Cr(tpytbupho)Cl2 | DMF/PhOH (0.6 M) | −2.30 | 93 ± 7 | 1.82 | 3.40 × 104 |

| 5 (20) | Cr(tBudhtBubpy)Cl(H2O) | DMF/PhOH (0.6 M) | −2.30 | 95 ± 8 | 9.29 | 1.86 × 105 |

| 6 (22) | Cr(tBudhphen)Cl(H2O) | DMF/PhOH (0.6 M) | −2.30 | 101 ± 3 | 4.90 | 9.80 × 104 |

*(tBudhbpy)2− = 6,6′-([2,2′-bipyridine]-6,6′-diyl)bis(2,4-di-tert-butylphenolate), (tpytbupho)− = 2-(2,2′:6′,2″terpyridin-6-yl)-4,6-di-tert-butylphenolate, (tbudhtbubpy)2− = 6,6′-(4,4′-di-tert-butyl-[2,2′-bipyridine]-6,6′-diyl)bis(2,4-di-tert-butylphenolate), (tbudhphen)2− = 6,6′-(1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-diyl)bis(2,4-di-tert-butylphenolate). Error bars are the SD from three parallel experiments.

Results

Simple mixing qpy ligand with CrCl3·6H2O in hot ethanol afforded the gray microcrystalline CrQPY in high yield. Then, the redox properties of CrQPY were initially examined by cyclic voltammetry at a 3 mm glassy carbon (GC) disk electrode in dry DMF. The potentials were calibrated to ferrocenium/ferrocene (Fc+/Fc) unless otherwise stated. The cyclic voltammogram (CV) of 0.5 mM CrQPY under Ar features three redox couples at −1.07, −1.50, and −1.85 V (Fig. 1A), assignable to formal CrIII/II, CrII/I, and CrI/0 redox events, respectively. The first and third couples are reversible, while the CrII/I one is quasi-reversible for its large peak-to-peak separation (>120 mV at 0.05 V s−1 scan rate). But the scan rate–dependent CVs indicate that this couple is still freely diffusing (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (26).

Under CO2, the first two redox couples remained unaltered upon scanning to −1.7 V (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), implying the absence of CO2 binding. When scanned to −2.1 V, an enhanced current was initiated at the CrI/0 reduction wave, suggesting catalytic CO2 reduction (15). Particularly, the formal CrII/I oxidation wave negatively shifted from −1.44 to −1.67 V (indicated in Fig. 1A), inferring the formation of a CrI-CO species and thus the CO evolution, reminiscent of an iron porphyrin catalyst (12). Further addition of phenol (PhOH) induced a much larger current at an onset potential of ca. −1.7 V, showing the CO2 reduction facilitated by proton source (14). It can be noticed that the first redox couple underwent a positive shift with addition of PhOH under either Ar (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) or CO2, indicating the interaction between PhOH and CrQPY (21). The catalytic current shows a linear correlation with the square root of [PhOH] until reaching a plateau with >ca. 1.6 M PhOH, indicating the typical saturation kinetics expected for catalytic reactions and the first-order kinetics of the catalysis in [PhOH] (Fig. 1 B and C) (11, 17). The catalytic current also increased linearly with higher [CrQPY], showing that the electrocatalysis is first order in the catalyst concentration (Fig. 1 D and E) (17).

The electrocatalytic performance of CrQPY was then evaluated by controlled-potential electrolysis (CPE) in DMF/PhOH (1.9 M) electrolyte, exhibiting 99.8% ± 4.0% Faradaic efficiency for CO formation at −2.00 V (Table 1, entry 1). A stable current density (j; Fig. 1F) of ca. 1.4 mA cm−2 was observed, and a total turnover number (tTON) value of ca. 7 was calculated with the number of catalyst molecules in the bulk electrolyte within 30 min. This tTON value, however, underestimates the catalytic performance as only a small fraction of catalyst molecules that interact with the electrode could contribute to catalysis (27). Therefore, with the above CPE data (j = 1.4 mA cm−2; E = −2.00 V), we applied Eq. 1 (28) to calculate the intrinsic kinetic constant (kcat = 86.8 s−1; see SI Appendix for details) of CrQPY based on the number of catalyst molecules in the diffusion layer of the cathode. A record-high TOF of 86.6 s−1 could then be calculated via Eq. 2 (28), which is almost one order of magnitude higher than those pioneering CrIII catalysts in DMF with respective optimal [PhOH] (4.90 ~ 9.29 s−1; Table 1). It is also notable that the reported Cr catalysts generally demand applied potentials at −2.30 V in CPE (Table 1). In comparison, the complete CO formation at −2.00 V by CrQPY demonstrates its much lower overpotential [as low as 0.19 V (19); see SI Appendix for details] by 0.3 V under similar conditions. Such a low applied overpotential is tentatively comparable to the reported overpotentials of some pioneering molecular electrocatalysts based on first-row transition metals for CO2-to-CO conversion, albeit with different benchmarking standard potentials (E0(CO2/CO), such as an FeII quaterpyridine complex (240 mV; E0(CO2/CO) = −1.41 V) (29), a CoII tripodal complex (200 mV; E0(CO2/CO) = −1.29 V) (15), a cationic FeIII porphyrin (220 mV; E0(CO2/CO) = −1.43 V) (30), etc.

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

Meanwhile, a remarkable TON of 1.56 × 105 within 30 min could also be estimated via Eq. 3 (28), comparable to the reported instances (Table 1) and thus suggesting its good stability. However, the more sustained CPE was limited possibly by the CO poisoning of the catalyst suggested by the subsequent mechanistic studies. After CPE, the reuse of the used working electrode (no visible deposit) into a CO2-saturated, catalyst-free electrolyte for CPE at −2.0 V could not produce any CO, confirming the molecular nature in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Overall, the above results display the high performance and molecular nature of CrQPY in the CO2 electroreduction.

To shed light on the catalytic mechanism of CrQPY, UV–Vis spectroelectrochemistry (UV–Vis-SEC) was applied to identify its catalytic intermediates in DMF. We collected spectra at the reduction potentials where CrIII, CrII, CrI, and Cr0 should be the dominating species, under Ar, CO2, and CO (SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S7), respectively. Interestingly, the spectra of the formal Cr0 state under CO2 and CO are very similar, and different from the one obtained under Ar. This outcome suggests the formation of analogous species under both CO2 and CO, most possibly CO-bound species. The CO-binding behavior is consistent with the CV of CrQPY under CO (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). A notable positive shift (60 mV) of the formal CrI/0 redox couple was observed in the CV under CO in comparison to that under Ar, giving a thermodynamic CO-binding constant (18) (KCO) of 1.87 × 103 M−1 (see SI Appendix for details), confirming the CO binding (31) at the Cr0 species.

To further examine the CO-bound species, we conducted the differential infrared SEC (IR-SEC; Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S9) on CrQPY in DMF under CO and CO2. By applying −1.90 V, the formal Cr0 species under CO exhibits three CO stretching signals at 2,005, 1,895, and 1,831 cm−1 in its IR spectrum (blue trace in Fig. 2B). The IR spectrum with CO2 revealed similar signals at 2,004, 1,888, and 1,829 cm−1 (red trace in Fig. 2B), further suggesting the formation of the same CO-bound species under either CO or CO2. Moreover, the signals displayed an overall shift to lower wavenumbers when CO2 was replaced with 13CO2, verifying that these peaks were arising from the reaction with CO2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The small signal at 2,005/2,004 cm−1 is attributable to Cr(CO)x species (32). The other two CO signals can be assigned to the expected [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 species. This assumption is well consistent with the DFT-calculated IR spectrum of the singlet [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 intermediate, which reveals C=O stretching modes at 1,893 and 1,838 cm−1 (violet traces in Fig. 2B; see SI Appendix for details), whereas its triplet analog shows peaks at 1,878 and 1,975 cm−1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S11).

Fig. 2.

(A) UV–Vis-SEC spectra of 2.0 mM of CrQPY in DMF under Ar (green), CO (blue), and CO2 (red) at the Cr0 state. (B) FT-IR-SEC spectra of 2.0 mM of CrQPY in DMF under CO (blue) and CO2 (red), with DFT-simulated IR spectrum of singlet [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 (violet). (C) TDDFT-simulated UV–Vis spectra of singlet [Cr(qpy)]0 (green) and singlet [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 (blue). (D) X-Band EPR spectra of frozen 1.0 mM DMF solutions of CrIII (gray), CrII (orange), CrI (green), Cr0 (red), and [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 (blue) species of CrQPY at 10 K.

Moreover, the electronic absorption spectra of [Cr(qpy)]0 and [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 intermediates were predicted at the time-dependent DFT (TDDFT; SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2) level of theory. Notably, quantum chemical calculations on the two intermediates suggest a strong mixing of d(Cr) and π* orbitals of qpy ligand and thus the involvement of ligand-centered reduction, as exemplified by the electron density analysis on the singlet [Cr(qpy)]0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). The calculated UV–Vis spectrum of the singlet [Cr(qpy)]0 features a main metal-to-ligand charge transfer (1MLCT) excitation into S8 at 808 nm, in good agreement with the experimental data (green traces in Fig. 2 A and C). Meanwhile, the computed spectrum of the singlet [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 is also in good agreement with the experimental data, both featuring a broad absorption feature at ca. 630 nm, which mainly stems from three MLCT transitions (S6, S7 and S8; blue traces in Fig. 2 A and C). On the other hand, the possible open-shell, triplet species of [Cr(qpy)]0 and [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 were excluded computationally, as their calculated vibrational and UV–Vis signals (SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S13) are in stark contrast to the measure ones.

The electronic structures of CrIII and the electrochemically generated species at different oxidation states were further studied using X-band electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy in frozen DMF solutions. The EPR spectrum of 1.0 mM initial CrIII at 10 K shows a rhombic anisotropic signal, matching a high-spin S = 3/2 octahedrally coordinated CrIII complex (Fig. 2D) (33, 34). This is in accordance with the DFT-calculated spin density of the initial CrIII species which was determined as [CrIII(qpy)Cl2]+ by the mass spectrum of CrQPY in DMF solution (SI Appendix, Fig. S14), where the three unpaired α-electrons are distributed among the nearly degenerate t2g orbitals, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A). This is also in accordance with the literature regarding the electronic configuration of related CrIII complexes (35). The experimental EPR spectrum was simulated (see SI Appendix and SI Appendix, Table S3 for simulation details) with g-values of gx,y,z [1.989, 2.0303, 1.964], a zero-field splitting D = 0.68 cm−1 and a rhombicity factor E/D = 0.18 (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), within the range of reported systems (33, 34). Upon 1e− reduction, the EPR signal vanished as expected for a formal CrII system with an even number of electrons. Further applying a potential at −1.6 V enabled a sharp EPR fingerprint of the formal CrI species with good agreement with the simulations in SI Appendix, Fig. S17; this can be attributed to an S = 1/2 signal located at a g-value of 1.984, close to the g-values of reported CrI systems (36). This S = 1/2 feature can be interpreted as a low-spin configuration in the metal center. Notably, the DFT results for this CrI intermediate, predicted as [CrI(qpy)]+·2Cl−, reveal a d 4 species instead of a d 5 character, as one unpaired β-electron is localized within a π* orbital (HOMO-1; SI Appendix, Fig. S15B). Finally, the EPR spectra of the Cr0 systems are silent under either N2 or CO. Presumably, it is less likely to form high-spin Cr0 species as it demands additional energy for the spin transition from the low-spin CrI intermediate, as supported by the quantum chemically predicted IR and UV–Vis signals of the various spin species. Overall, the EPR measurements on CrQPY reveal the isolations of the EPR-silent CrII, Cr0 and [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 intermediates as well as the EPR-active CrIII and CrI species.

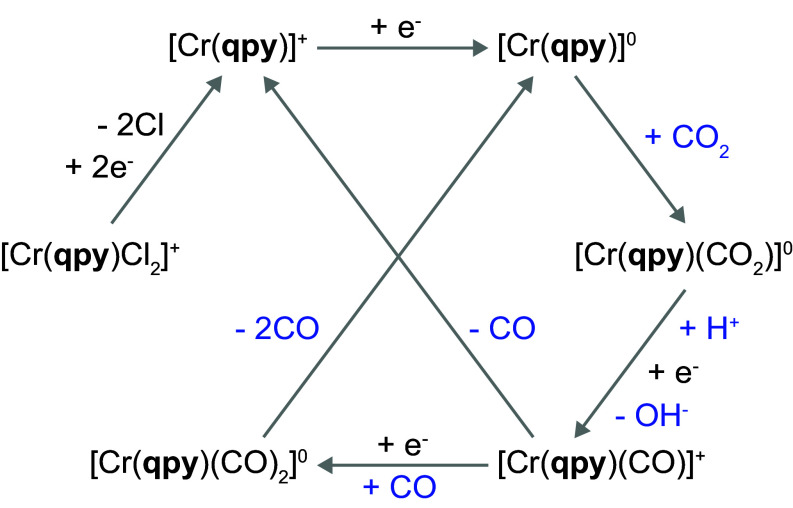

Based on the above mechanistic insights, a plausible mechanism for the CO2-to-CO conversion catalyzed by CrQPY can be proposed in Fig. 3. The catalytic cycle is initiated by three times of 1e− reduction of [Cr(qpy)Cl2]+, forming the active [Cr(qpy)]0 species for CO2 binding. The CO2-adduct presumably experiences a proton-coupled electron transfer to generate a Cr-COOH species with PhOH as the proton source, which then undergoes C-OH cleavage to afford [Cr(qpy)(CO)]+ (5, 10). This CrI-CO adduct is not thermodynamically stable as it was suggested by the negatively shifted CrII/I oxidation wave under dry CO2 (Fig. 1A) but not revealed by the SEC. Thus, [Cr(qpy)(CO)]1+ can release CO to recover [Cr(qpy)]+ for the next cycle. Meanwhile, it can also bind to another CO with 1e− reduction to afford the detected [Cr(qpy)(CO)2]0 intermediate in which two CO molecules will dissociate to give [Cr(qpy)]0 into another catalytic cycle.

Fig. 3.

Proposed catalytic cycle for CO2 reduction catalyzed by CrQPY.

Discussion

In summary, we here disclose the evaluations and mechanistic studies on a CrIII quaterpyridine complex for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction, which achieves 99.8% ± 4.0% Faradaic efficiency for CO production in DMF/PhOH medium. Impressively, a record-high TOF among the documented CrIII catalysts has been achieved at an overpotential of merely 190 mV. Such a low overpotential is also comparable to some pioneering molecular catalysts featuring earth-abundant metals. These excellent performances can be ascribed to the use of four N donors instead of the mixed N/O ones in most reported CrIII examples, which should better stabilize the low-oxidation-state species (37) for catalysis at lower overpotentials. Notably, the electronic structures of the key intermediates involved in CO2 reduction have been revealed by electrochemistry, SEC, EPR, and quantum chemical calculations, which are scarcely documented but desirable for understanding the mechanisms of Cr-based molecular catalysts. The ligand-radical-based reactive Cr0 species further emphasizes the merits of the quaterpyridine ligand as a versatile electron reservoir with its extended π-delocalized network. The mechanistic results also indicate the CO-binding behavior which may induce the catalyst poisoning, while it can be circumvented by surface immobilization (38) within our future efforts. We believe that these findings provide a promising noble-metal-free molecular electrocatalyst for CO2 reduction, along with valuable mechanistic insights for further rational design on the Cr-based catalysts.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

CrQPY was prepared following the previously reported method (39), and other chemicals were commercially available and used without further purification.

Methods.

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660D). The generated gas samples in the head space were analyzed by an Agilent 7890B Series GC custom chromatograph equipped with thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and flame ionization detector (FID), and the products in the solution were analyzed by 1H NMR (Bruker Avance III 500 MHz) following the protocol reported by Nocera et al. (40). UV–Vis spectra were collected on a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer. FT-IR spectra were obtained on a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). All experiments were operated at room temperature (24 to 25 °C) unless otherwise stated. All quantum chemical calculations determining structural and electronic properties were performed using the Gaussian 16 program (41).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

M.G.-S. and O.R. acknowledge the Max Planck Society for funding and Daniel J. SantaLucia for support with the electron paramagnetic resonance simulations. M.G.-S acknowledges the support of the HORIZON-MSCA-2021-PF project TRUSol No.101063820. G.Y. and S.K. acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation)—Projektnummer 456209398. All calculations were performed at the Universitätsrechenzentrum of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

Author contributions

J.-W.W. designed research; J.-W.W., Z.-M.L., G.Y., and S.K. performed research; J.-W.W., G.Y., M.-G.S., S.K., O.R., and G.O. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.-W.W., Z.-M.L., G.Y., M.-G.S., and O.R. analyzed data; and J.-W.W., M.-G.S., S.K., O.R., and G.O. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Cheng Y., Hou P., Wang X., Kang P., CO2 electrolysis system under industrially relevant conditions. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 231–240 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peter S. C., Reduction of CO2 to chemicals and fuels: A solution to global warming and energy crisis. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 1557–1561 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominguez-Ramos A., et al. , Global warming footprint of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate. J. Cleaner Prod. 104, 148–155 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma F., et al. , Earth-abundant-metal complexes as photosensitizers in molecular systems for light-driven CO2 reduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 500, 215529 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider J., Jia H., Muckerman J. T., Fujita E., Thermodynamics and kinetics of CO2, CO, and H+ binding to the metal centre of CO2 reduction catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2036–2051 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosugi K., Kashima H., Kondo M., Masaoka S., Copper(II) tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)porphyrin: Highly active copper-based molecular catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem. Commun. 58, 2975–2978 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siritanaratkul B., Eagle C., Cowan A. J., Manganese carbonyl complexes as selective electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction in water and organic solvents. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 955–965 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Allsburg K. M., et al. , Early-stage evaluation of catalyst manufacturing cost and environmental impact using CatCost. Nat. Catal. 5, 342–353 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J. W., et al. , Boosting CO2 photoreduction by π–π-induced preassembly between a Cu(I) sensitizer and a pyrene-appended Co(II) catalyst. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2221219120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J.-W., et al. , Precious-metal-free CO2 photoreduction boosted by dynamic coordinative interaction between pyridine-tethered Cu(I) sensitizers and a Co(II) catalyst. JACS Au 3, 1984–1997 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson M. D., et al. , Manganese catalysts with bulky bipyridine ligands for the electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide: Eliminating dimerization and altering catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5460–5471 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhugun I., Lexa D., Savéant J.-M., Catalysis of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide by iron(0) porphyrins: Synergystic effect of weak Brönsted acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 1769–1776 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M., et al. , Tandem electrocatalytic CO2 reduction with Fe-porphyrins and Cu nanocubes enhances ethylene production. Chem. Sci. 13, 12673–12680 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J.-W., et al. , CH–π interaction boosts photocatalytic CO2 reduction activity of a molecular cobalt catalyst anchored on carbon nitride. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 100681 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J. W., et al. , Electrocatalytic and photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO by cobalt(II) tripodal complexes: Low overpotentials. High efficiency and selectivity. ChemSusChem 11, 1025–1031 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J. W., Liu W. J., Zhong D. C., Lu T. B., Nickel complexes as molecular catalysts for water splitting and CO2 reduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 378, 237–261 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J.-W., et al. , Syngas production with a highly-robust nickel(II) homogeneous electrocatalyst in a water-containing system. ACS Catal. 8, 7612–7620 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froehlich J. D., Kubiak C. P., The homogeneous reduction of CO2 by [Ni(cyclam)](+): Increased catalytic rates with the addition of a CO scavenger J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3565–3573 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooe S. L., Dressel J. M., Dickie D. A., Machan C. W., Highly efficient electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO by a molecular chromium complex. ACS Catal. 10, 1146–1151 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid A. G., et al. , Inverse potential scaling in co-electrocatalytic activity for CO2 reduction through redox mediator tuning and catalyst design. Chem. Sci. 13, 9595–9606 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid A. G., et al. , Homogeneous electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 by a CrN3O complex: Electronic coupling with a redox-active terpyridine fragment favors selectivity for CO. Inorg. Chem. 61, 16963–16970 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid A. G., et al. , Comparisons of bpy and phen ligand backbones in Cr-mediated (co-)electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Organometallics 42, 1139–1148 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouchfiq A., et al. , A bioinspired molybdenum-copper molecular catalyst for CO2 electroreduction. Chem. Sci. 11, 5503–5510 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogeron T., et al. , Pyranopterin related dithiolene molybdenum complexes as homogeneous catalysts for CO2 photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 17033–17037 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark M. L., et al. , Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by M(bpy-R)(CO)4 (M = Mo, W; R = H, tBu) complexes. Electrochemical, spectroscopic, and computational studies and comparison with group 7 catalysts. Chem. Sci. 5, 1894 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Y., Wu Y., Lai W., Cao R., Electrocatalytic water oxidation by a water-soluble nickel porphyrin complex at neutral pH with low overpotential. Inorg. Chem. 54, 5604–5613 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P., et al. , A molecular copper catalyst for electrochemical water reduction with a large hydrogen-generation rate constant in aqueous solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 13803–13807 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costentin C., Drouet S., Robert M., Savéant J. M., Turnover numbers, turnover frequencies, and overpotential in molecular catalysis of electrochemical reactions. Cyclic voltammetry and preparative-scale electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11235–11242 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cometto C., et al. , Highly selective molecular catalysts for the CO2-to-CO electrochemical conversion at very low overpotential. contrasting Fe vs Co quaterpyridine complexes upon mechanistic studies. ACS Catal. 8, 3411–3417 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azcarate I., Costentin C., Robert M., Saveant J. M., Through-space charge interaction substituent effects in molecular catalysis leading to the design of the most efficient catalyst of CO2-to-CO electrochemical conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16639–16644 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujita E., Creutz C., Sutin N., Szalda D. J., Carbon dioxide activation by cobalt(I) macrocycles: Factors affecting carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 343–353 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shufler S. L., Sternberg H. W., Friedel R. A., Infrared spectrum and structure of chromium hexacarbonyl, Cr(CO)6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78, 2687–2688 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonomo R. P., Di Bilio A. J., Riggi F., EPR investigation of chromium(III) complexes: Analysis of their frozen solution and magnetically dilute powder spectra. Chem. Phys. 151, 323–333 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaham N., Cohen H., Meyerstein D., Bill E., EPR Measurements corroborate information concerning the nature of (H2O)5CrIII–alkyl complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 18, 3082–3085 (2000), 10.1039/b004755o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Förster C., Heinze K., Bimolecular reactivity of 3d metal-centered excited states (Cr, Mn, Fe, Co). Chem. Phys. Rev. 3, 041302 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabeah J., et al. , Formation, operation and deactivation of Cr catalysts in ethylene tetramerization directly assessed by operando EPR and XAS. ACS Catal. 3, 95–102 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L., et al. , Molecular quaterpyridine-based metal complexes for small molecule activation: Water splitting and CO2 reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 7271–7283 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu X. M., et al. , Enhanced catalytic activity of cobalt porphyrin in CO2 electroreduction upon immobilization on carbon materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6468–6472 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constable E. C., Elder S. M., Tocher D. A., The preparation and structural characterization of a chromium(III) complex with a potentially helicating ligand: The X-ray crystal structure of trans-dichloro(2,2′:6′,2″:6″,2‴-quaterpyridine-N, N′, N″, N‴)chromium(III) chloride tetrahydrate. Polyhedron 11, 1337–1342 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margarit C. G., Asimow N. G., Costentin C., Nocera D. G., Tertiary amine-assisted electroreduction of carbon dioxide to formate catalyzed by iron tetraphenylporphyrin. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 72–78 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frisch M. J., et al. , Gaussian 16, Revision A.03(Gaussian, Inc., 2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.