Abstract

Depression has robust natural language correlates and can increasingly be measured in language using predictive models. However, despite evidence that language use varies as a function of individual demographic features (e.g., age, gender), previous work has not systematically examined whether and how depression’s association with language varies by race. We examine how race moderates the relationship between language features (i.e., first-person pronouns and negative emotions) from social media posts and self-reported depression, in a matched sample of Black and White English speakers in the United States. Our findings reveal moderating effects of race: While depression severity predicts I-usage in White individuals, it does not in Black individuals. White individuals use more belongingness and self-deprecation-related negative emotions. Machine learning models trained on similar amounts of data to predict depression severity performed poorly when tested on Black individuals, even when they were trained exclusively using the language of Black individuals. In contrast, analogous models tested on White individuals performed relatively well. Our study reveals surprising race-based differences in the expression of depression in natural language and highlights the need to understand these effects better, especially before language-based models for detecting psychological phenomena are integrated into clinical practice.

Keywords: depression, racial differences, social media, mental health

Language on social media can reveal mental health disorders (1, 2). Computational models trained to detect depression in language hold the promise of offering a scalable and affordable assessment of mental health disorders (3). However, it is unknown whether these computational methods perform equally well across all sub-populations. While early evidence suggests that the language of individuals with self-identified mental illnesses differs as a function of gender, geographical location, and race (4), the latter has only been examined in exploratory analyses, making comparison difficult.

Race seems to have been especially neglected in work on language-based assessment of mental illness. A systematic review of studies predicting mental illness using social media data found that no study accounted for demographic features beyond age and gender (5). Though first-person pronouns (e.g., I, we, us) are robustly associated with depression (6), early evidence suggests this effect could depend on race (7). Relatedly, depressed individuals living in communities with stigmatized attitudes toward mental disorders are reported to inhibit negative emotions (8, 9). Furthermore, the datasets on which depression language models are trained do not reflect the racial composition of the US population, which may result in these models showing worse performance for people of color (7).

To our knowledge, there has been no direct examination of whether race moderates the relationship between depression and language use, in part because researchers frequently fail, or are unable, to measure race. To address this gap, we examined whether race moderates depression’s association with social media language in a sample of English speakers in the United States. We focused on language markers previously found related to depression, specifically first-person pronoun use, and negative emotion language. As Black individuals have been under-represented in much previous research on the language of depression, raising concerns about the representativeness of findings (7), we employed a matched-pairs design to obtain equal numbers of Black and White participants with similar age and gender distribution in our final sample (See Materials and Methods in SI Appendix). Further, we evaluate the relative performance of predicting depression using language using machine learning models in Black and White participants, keeping the amount of training data consistent. Participants were recruited using Qualtrics; the final matched sample consisted of participants who self-reported depression severity using Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 and demographic details, including race, and consented to share their Facebook status updates (n = 868, 76% Female). The studypopulation is similar to that of US adults who use social media, specifically Facebook. All study protocols and procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board; all participants provided informed consent.

Effect of Race on the Language of Depression

Linguistic Inquiry of Word Count.

We began by examining the main effect of depression on first-person pronoun use and negative emotion language using predefined categories in Linguistic Inquiry of Word Count (LIWC-2022). Consistent with prior work (6), individuals with higher levels of depression used more first-person singular pronouns* (“I-usage”; e.g., I, me, my) and negative emotion terms (e.g., bad, hate, the emoticon:(). In contrast, individuals with lower levels of depression used more first-person plural pronouns (e.g., we, our, us).

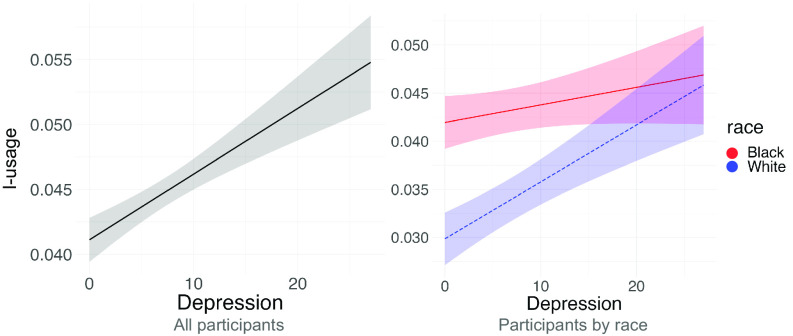

We next examined whether race moderates the effect of depression on language. Race significantly moderated the relationship between depression and I-usage: Greater depression severity was associated with more I-usage for White, but not Black, individuals (Fig. 1). To explore one possible explanation for this finding that a lack of variability in I-usage in the Black subgroup might explain why this language feature was unrelated to depression, we examined variance in I-usage by race. While there was a main effect of race on I-usage, with Black individuals showing greater I-usage overall, I-usage was roughly similarly distributed within each race subgroup (see SI Appendix for more details).

Fig. 1.

Left: I-usage as a function of depression severity (measured via PHQ-9). I-usage grows linearly with depression. Right: I-usage by participant’s race after interaction. For White participants, higher levels of depression led to greater I-usage, while Black participants exhibited levels of I-usage that did not vary as a function of depression severity.

Topic Modeling.

We examined the main effect of depression on semantically related groups of words (“topics”) obtained by Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). Here we focus on the significant topics (correlated with PHQ-9) that reflect negative emotion (n = 23, See SI Appendix). More depressed individuals showed increased use of negative emotions; the top-3 topics discuss the feelings of emptiness-longing (e.g., inside, deep, longing), disgust (e.g., ew, yuck, disgusting), and despair (e.g., begging, knees, hollow).

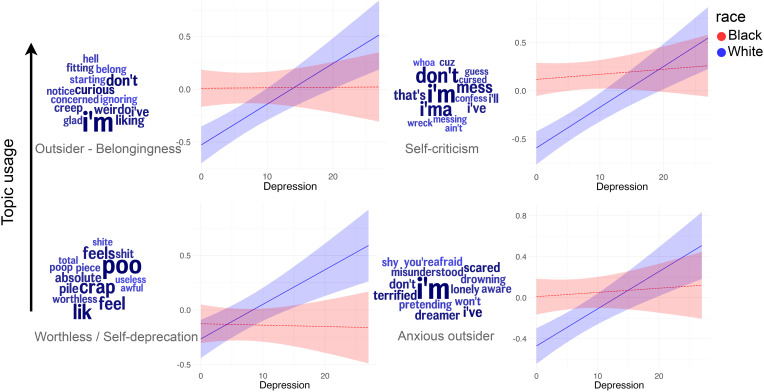

Next, we examined moderation by race. Of the original 23 topics sharing a main effect with depression, race was a significant moderator for five, that is, outsider-belongingness (e.g., weirdo, creep, belong), self-criticism (e.g., i’ma, mess, wreck), worthlessness/self-deprecation (e.g., worthless, crap, absolute), anxious-outsider (e.g., terrified, shy, misunderstood), and despair (e.g., begging, knees, hollow). Each of these topics was related to depression severity among White, but not Black, individuals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Normalized topic usage frequency for negative emotion topics (i.e., clusters of co-occurring words generated by LDA) as a function of depression severity, separately by participant race (in decreasing order of interaction effect—depression x race). For White participants, higher levels of depression led to greater topic usage, whereas Black participants used topics at similar levels across the range of depression severity.

Performance of Language-based Models for Predicting Depression across Races.

Last, we examined how race impacted the performance of language-based depression models. Specifically, we trained models on Black () and White () subsamples, respectively, and then tested them on Black and White subsamples, respectively. Results from these analyses, following a 2 × 2 design (Black vs. White train; Black vs. White test), are presented in Table 1. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the model trained on language exclusively from White participants () showed strong performance when tested on a held-out dataset of White participants (r = 0.392); model performance was attenuated when tested on Black participants (r = 0.132). In contrast, the model trained on a similar amount of language exclusively from Black participants () performed poorly when tested on a held-out dataset of Black participants (r = 0.126); surprisingly, this model showed improved (but still relatively poor) performance when tested on White participants (r = 0.204). The regression model trained on BERT embeddings performed similarly, that is, the strongest correlation is obtained for the White test set, whereas the performance attenuated when tested on the Black test set irrespective of the training model.

Table 1.

Pearson r with p values for 5-fold cross-validation

| White test set | Black test set | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature set: 1-3 gm, LIWC categories and LDA topics | ||

| 0.392 (0.000) | 0.132 (0.006) | |

| 0.204 (0.000) | 0.126 (0.009) | |

| Feature set: BERT embeddings (Layer 11 and 12) | ||

| 0.347 (0.000) | 0.104 (0.031) | |

| 0.161 (0.001) | 0.058 (0.225) |

Models trained on White individuals’ language showed the strongest correlation with the White test set whereas the models (trained on either Black or White language) have a weak correlation with the Black test set.

Discussion

We showed that race moderates the relationship between depression and several language features. Specifically, greater depression severity is related to increased I-usage among White, but not Black, individuals. Negative emotions expressing the feelings of outsider-belongingness, self-criticism, worthlessness/self-deprecation, and anxious-outsider language are related to greater depression severity only in White individuals. Lastly, we showed that language-based prediction models performed poorly when tested on data from Black individuals, regardless of whether they had been trained using language from White or Black individuals. This stood in contrast to the performance of prediction models tested on White individuals, which showed relatively strong performance across the board.

While first-person pronoun use (“I” + “we”) was found to be unrelated to depression in people of color (7), our study reveals that I-usage in particular is unrelated to depression in Black individuals. One possible explanation behind this could be independent model of self in European Americans (10) and dual model of self in Black Americans (11). A strength of our study was our matched design, which ensured parity between Black and White participants in our sample, thus ruling out other variables to explain these effects. Relatedly, by including equal numbers of Black and White individuals in our study, we ensured we were adequately powered to test race as a moderator. Our study also had weaknesses, including that we only examined two racial subgroups: Black and White individuals. Additionally, we analyzed Facebook language, raising the question of whether our results relate to natural language in general or written social media language in particular. Further, expanding this research to other racial subgroups, and analyzing a broader range of language formats (including spoken language), is needed.

Our findings that key language features track with depression severity in White but not Black individuals and that language-based models of depression perform poorly in Black populations raise concerns about the generalizability of previous computational language findings. One explanation for these findings is that depression may not manifest in language for Black individuals. Another possibility is that different language markers not examined here, such as other word categories or paralinguistic features (e.g., tone, speech rate), could relate to depression among Black individuals. Regardless, our results highlight the pressing need to ensure language-based depression prediction models show racial invariance before such models are integrated into research or clinical practice.

Relatedly, our results complicate robust evidence for a link between depression and I-usage (6), which has implications for understanding the nature of depression. The linguistic marker I-usage has been taken to reflect self-focus or self-immersed perspective taking (2); these processes have been identified as possible risk or maintaining factors for depression. That depression was unrelated to I-usage among Black participants in our study threatens the generalizability of these assumptions. More broadly, our results raise concern that certain psychological processes thought to predict or maintain depression may be less relevant, or even irrelevant, to populations historically excluded from psychological research, including Black individuals.

matseccnt1

Methods

We used LIWC 2022 and topic modeling to extract language markers associated with depression from matched participants’ social media posts. We regressed each language marker on depression severity and probed significant interactions using simple-slopes analyses (See SI Appendix for more details).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Intramural Research Program of the NIH-NIDA (ZIA-DA000628, ZIA DA000632), NIH-NIMHD (R01MD018340) and NIH-NIAAA (R01 AA028032-01). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions

S.R., S.G., and S.C.G. designed research; S.R., E.C.S., A.F., B.C., and S.C.G. performed research; S.R., E.C.S., S.G., A.F., and S.C.G. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.R., E.C.S., S.G., A.F., and S.C.G. analyzed data; and S.R., E.C.S., L.H.U., B.C., and S.C.G. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

*First-person singular pronouns and I-usage are used interchangeably in this draft.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The mean language marker scores (LIWC-2022 categories, i.e., First person pronouns and Negative Emotion and 23 LDA topics) for all depression scores in PHQ9, for matched participants, is available at https://osf.io/hkep7/ (12).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Guntuku S. C., Yaden D. B., Kern M. L., Ungar L. H., Eichstaedt J. C., Detecting depression and mental illness on social media: An integrative review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 18, 43–49 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.E. Stade, L. H. Ungar, G. Sherman, A. M. Ruscio, Depression and anxiety have distinct and overlapping language patterns: Results from a clinical interview (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Milintsevich K., Sirts K., Dias G., Towards automatic text-based estimation of depression through symptom prediction. Brain Informat. 10, 1–14 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vyas C. M., et al. , Association of race and ethnicity with late-life depression severity, symptom burden, and care. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201606 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry L. C., et al. , Race-related differences in depression onset and recovery in older persons over time: The health, aging, and body composition study. Am. J. Geriat. Psych. 22, 682–691 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtzman N. S., et al. , A meta-analysis of correlations between depression and first person singular pronoun use. J. Res. Person. 68, 63–68 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.C. Aguirre, K. Harrigian, M. Dredze, “Gender and racial fairness in depression research using social media” in Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, P. Merlo, J. Tiedemann, R. Tsarfaty, Eds. (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021), pp. 2932–2949.

- 8.M. De Choudhury, M. Gamon, S. Counts, E. Horvitz, “Predicting depression via social media” in Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, E. Kiciman, N. Ellison, B. Hogan, P. Resnick, I. Soboroff, Eds. (The AAAI Press, 2013), vol. 7, pp. 128–137.

- 9.Bailey R. K., Mokonogho J., Kumar A., Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neurops. Dis. Treat., 603–609 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chentsova-Dutton Y. E., Tsai J. L., Self-focused attention and emotional reactivity: The role of culture. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 98, 507 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brannon T. N., Markus H. R., Taylor V. J., “Two souls, two thoughts,’’ two self-schemas: Double consciousness can have positive academic consequences for African Americans. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 108, 586 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.S. Rai et al., Key language markers of depression on social media depend on race. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/hkep7/. Deposited 24 October 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The mean language marker scores (LIWC-2022 categories, i.e., First person pronouns and Negative Emotion and 23 LDA topics) for all depression scores in PHQ9, for matched participants, is available at https://osf.io/hkep7/ (12).