Abstract

The retroviral Gag protein plays the central role in the assembly process and can form membrane-enclosed, virus-like particles in the absence of any other viral products. These particles are similar to authentic virions in density and size. Three small domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag protein have been previously identified as being important for budding. Regions that lie outside these domains can be deleted without any effect on particle release or density. However, the regions of Gag that control the size of HIV-1 particles are less well understood. In the case of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), the size determinant maps to the CA (capsid) and adjacent spacer sequences within Gag, but systematic mapping of the HIV Gag protein has not been reported. To locate the size determinants of HIV-1, we analyzed a large collection of Gag mutants. To our surprise, all mutants with defects in the MA (matrix), CA, and the N-terminal part of NC (nucleocapsid) sequences produced dense particles of normal size, suggesting that oncoviruses (RSV) and lentiviruses (HIV-1) have different size-controlling elements. The most important region found to be critical for determining HIV-1 particle size is the p6 sequence. Particles lacking all or small parts of p6 were uniform in size distribution but very large as measured by rate zonal gradients. Further evidence for this novel function of p6 was obtained by placing this sequence at the C terminus of RSV CA mutants that produce heterogeneously sized particles. We found that the RSV-p6 chimeras produced normally sized particles. Thus, we present evidence that the entire p6 sequence plays a role in determining the size of a retroviral particle.

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag polyprotein, Pr55gag (Fig. 1A), is synthesized on membrane-free polysomes and subsequently transported to the plasma membrane, the site of virus assembly. Very late during or immediately after budding, cleavage of Pr55gag by the virally encoded PR (protease) releases the mature products p17 (MA [matrix]), p24 (CA [capsid]), p7 (NC [nucleocapsid]), and the C-terminal peptide p6, as well as two small peptides, p1 and p2 (21, 27). This proteolysis is associated with condensation of the core and is a prerequisite for viral infectivity but not for particle assembly or release (30, 40).

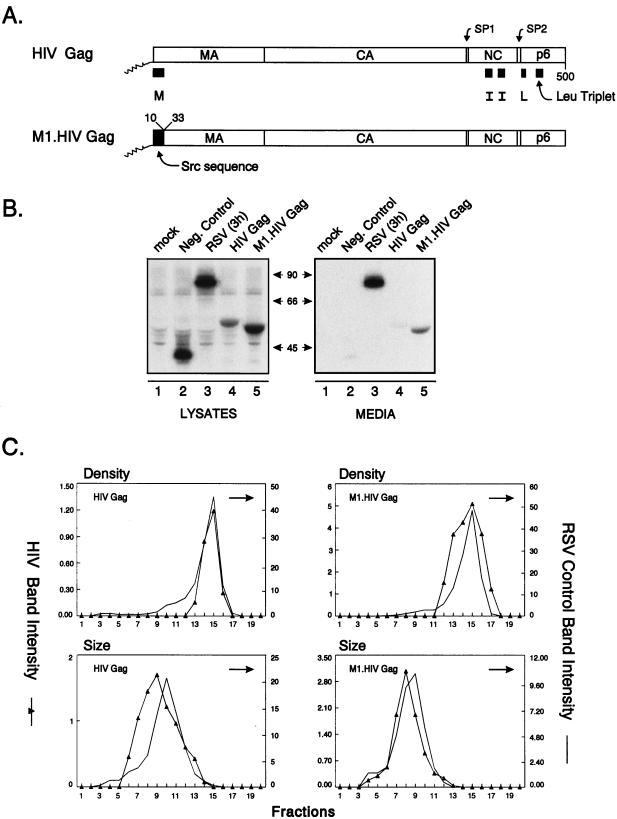

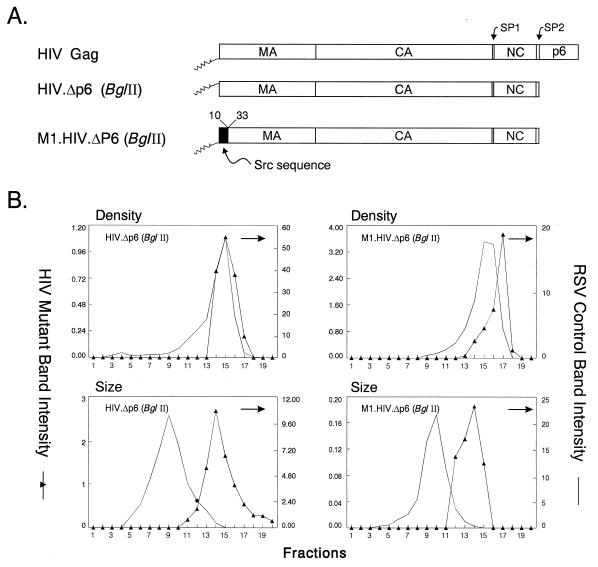

FIG. 1.

Control experiments. (A) The wild-type HIV-1 Gag protein is designated HIV Gag. In M1.HIV Gag the black box at its N terminus represents the first 10 residues of pp60v-scr, which were substituted for the first 32 residues of HIV-1 Gag. The squiggle depicts the fatty acid myristate. The names of the Gag cleavage products (MA, CA, NC, and p6) are indicated. The two arrows above the Gag protein show the spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2). The black rectangles beneath M1.HIV Gag protein indicate domains essential for membrane binding (M), a late event in particle budding (L), and interactions between Gag molecules (I) as well as the leucine triplet sequence important for Vpr incorporation. Numbers refer to amino acid residues. (B) COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated DNAs and were labeled as described in Materials and Methods. For comparison, an assembly-incompetent deletion mutant (RHB.T10C [37], which lacks late domains needed for budding) is shown in lanes 2. Molecular weight standards (in kilodaltons) are shown between the two panels. (C) The graphs represent the measurement of particle density in isopycnic sucrose gradients and the distribution of particle size in rate zonal gradients. COS-1 cells were transfected with pSV.HIV Gag or pSV.M1.HIV Gag. After 48 h, the cells and RSV-infected turkey embryo fibroblasts were labeled with [35S]methionine for 8 h (for isopycnic gradients) or 5 h (for velocity gradients). After the labeling period, particles and densities were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the direction of sedimentation.

It is well known that the Gag protein plays the central role in the assembly of retroviruses (for a review, see reference 11). Indeed, the process of particle formation in different Gag expression systems mimics the budding of authentic immature virions with regard to particle size, density, physical shape, and core morphology (18, 28, 32). Extensive studies of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) and HIV-1 Gag proteins have led to the conclusion that only three small functional domains are essential for particle production (Fig. 1A). The M domain, located at the amino terminus of MA, provides the membrane-binding and -targeting functions (47, 49, 53, 57). At the membrane, interactions take place among roughly 2,000 Gag molecules via the I domain, of which there are two copies within NC (2, 51, 55). The L domain, located near the beginning of the p6 sequence in HIV-1 and in the p2b sequence of RSV, is presumed to operate late in budding, mediating the pinching-off step (17, 20, 37, 54). These assembly domains are fully exchangeable between RSV and HIV-1 in spite of their lack of sequence conservation and, in the case of the L domain, are also positionally independent (2, 37).

While mutations within the assembly domains abolish or severely impair particle production, regions that lie outside these domains can be deleted without any effect on particle release or density. Several lines of evidence indicate that these dispensable regions for assembly process play critical roles early and late in the infectious cycle. The HIV-1 MA protein is targeted to the nucleus, and some evidence suggests that it contributes to the transport of the viral preintegration complex from the cytoplasm to the nucleus of nondividing cells (4, 5). In addition, this sequence in the context of the Gag precursor is implicated in the specific incorporation of viral glycoproteins into virions (14, 56). The HIV-1 NC sequence contains two copies of a conserved zinc finger motif known as the cysteine-histidine box which are critical for the packaging of genomic RNA (1, 13, 19). The C-terminal p6 domain is required for Vpr incorporation into virus particles (31, 35). With regard to CA, conflicting reports concerning an essential role for this sequence in particle assembly have been published. It has been reported that some deletions or linker insertions within CA prevent assembly (8, 15); however, such loss-of-function phenotypes could be due to misfolding of Gag as a result of the alterations to CA. In fact, other studies have shown that the HIV-1 capsid region is not critical for particle formation, although it is essential for infectivity (42, 48, 49). Indeed, it has been shown that the N terminus and middle region of the HIV-1 CA protein seem to be critical in the production of mature virions with the correct morphology (43). Therefore, it seems that the normal size and shape of the emerging particle is a required element for infectivity.

Little is known about the regions of Gag that control the size of a retroviral particle. A recent study of RSV (34) shows that the size determinants map to the segment of Gag consisting of CA plus the spacer peptides located between CA and NC. That is, deletions within the CA-spacer peptide (CA-SP) sequence result in particles that are large and heterogeneous in size (34). In the case of HIV-1, mutants that have a linker insertion within spacer peptide 1 (SP1) or lack this entire spacer peptide have been reported to release particles that are more heterogeneously sized (33, 43) than wild-type virions (15, 16, 43). Other studies have suggested that the HIV-1 CA domain may have a role in determining virion size (8, 15). Furthermore, in vitro assembly studies have suggested that regions surrounding the CA sequence are required for determining particle assembly and morphology (6). In these experiments, Escherichia coli-expressed CA-NC fragments of RSV and HIV-1 Gag as well as CA-NC-p6 segments of HIV-1 Gag were shown to be able to form particles in the presence of RNA (6). These results suggest also that RNA may initiate and organize the assembly process by acting as a scaffold. Finally, unpublished results propose that the HIV-1 MA domain may play a role in constraining the shape of the particles in vitro (7).

The goal of the experiments described in this study was to systematically map the size determinants of HIV-1 in the context of Pr55gag, using rate zonal sedimentation. As is the case for RSV Gag (34), the data indicate that the entire HIV-1 Gag protein is not required for normal particle size. However, our results indicate that the HIV CA sequence, unlike that of RSV, is not important for controlling particle size; rather, the main region found to be critical for this resides in the NC and p6 sequences. Altogether, these results reveal a new role of the p6 domain as a determinant of retroviral size particle and provide strong evidence that oncoviruses and lentiviruses have different size-controlling elements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All of the constructs used in this study (except pSV.Myr0.LOC7) encode an inactivated protease (2, 10, 52).

Construction of pSV.HIV Gag and pSV.M1.HIV Gag.

All DNA manipulations were carried out by using standard methods (45). Recombinant plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH-1 with Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin (25 μg/ml). Each of the gag alleles made by PCR amplification was sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired deletions. Furthermore, two independent clones of each mutant were analyzed in transfection experiments to rule out the possibility of unwanted mutations.

HIV-1 sequences were derived from pHXB2Dgpt and the Rev-independent mutant p17M1234 (46) (a kind gift from George Pavlakis, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.). To make pSV.HIV Gag, two PCR amplifications were performed. The first 117 gag codons of plasmid p17M1234 were amplified in order to create an NdeI site at the initiator ATG, using the upstream primer described previously (38) and the following downstream primer (the AlwNI restriction endonuclease recognition site is underlined, as are restriction sites as indicated in parentheses for subsequent primers): 5′-TGTCCTGTGTCAGCTGCTGCCTGCTGGGCCTTCTTCTT-3′. The gag gene, except the first 117 codons, was also amplified from plasmid pSV.HGagE (2), using 5′-AAGAAAAAAGCACAGCAAGCAGCAGCTGACACAGGA-3′ (AlwNI) as the upstream primer and 5′-TACCTATAGCGCGCTGTCCACAGATTTCTATGAGTA-3′ (BssHII) as the downstream primer. The PCR products were digested only with AlwNI and religated. The ligated DNA was used as the template for a second round of PCR amplification with the NdeI upstream and BssHII downstream primers. The recombinant product was digested with NdeI and BssHII and cloned into equivalent sites of pSV.Myr0.N (38). Collectively, these manipulations replace the RSV gag gene in the simian virus 40 expression vector with the Rev-independent allele of HIV gag.

To make pSV.M1.HIV Gag, the first 32 codons of the HIV-1 gag gene were substituted with the first 10 codons for the pp60v-src (Src) oncoprotein. PCR amplification of the gag sequence of pSV.HIV Gag was performed to create an MluI site (a Leu codon was introduced) immediately upstream of the 33rd codon, using the upstream primer 5′-AAGAAGTACAACGCGTTGCACATCGTATGGGCAAGCA-3′ (MluI) and the downstream BssHII primer described above. Following digestion with MluI and SpeI, the resulting fragment was engineered into a Src-RSV-HIV Gag chimera, using the MluI site situated between the Src and RSV coding sequences and the SpeI site within the HIV coding sequence.

Construction of deletion mutants.

Matrix deletion mutants M1.HMΔ1, M1.HMΔ2, and M1.HMΔ3 were created by PCR amplification of fragments from the matrix coding sequence of pSV.M1.HIV Gag, using the upstream primers 5′-TGGCCTGTTAGACGCGTCAGAAGGCTGTAGACAAATACT-3′ (MluI), 5′-TAGCAACCCACGCGTGTGTGCACCAGCGGATCGAGA-3′ (MluI), and 5′-AGGCCCAGCAGGACGCGTCTGACACAGGACACAGCAATCAGGT-3′ (MluI), respectively. The downstream BssHII primer described previously was used. Following digestion with MluI and BssHII, the PCR products were ligated into the MluI-BssHII sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag.

To make capsid deletion mutants M1.HCΔ4 and M1.HCΔ5, two PCR amplifications of nucleotides 255 to 815 and 908 to 1100 (for M1.HCΔ4) and 255 to 908 and 1008 to 1100 (for M1.HCΔ5) of gag from pSV.M1.HIV Gag were performed to create an EspI site at the site of the deletion. For M1.HCΔ4, the following upstream and downstream primers were used: 5′-AGAAGGTACCGAGCTCTACTGCAGGGA-3′ (SacI) plus 5′-AAGTTCTAGGTGGCTTAGCCTGATGTACCATTT-3′ (EspI) and 5′-ATGTTTTCAGCAGCTAAGCAAGGAGCCACCCCACAA-3′ (EspI) plus 5′-TTCCTGAAGGGTACTAGTAGTTCCTGCTAT-3′ (SpeI), respectively. Construction of M1.HCΔ5 used the same upstream SacI primer in combination with downstream primer 5′-TTGTGGGGTGGCTCCTTGCTTAGCTGCTGAAAACAT-3′ (EspI) and the same downstream SpeI primer in combination with upstream primer 5′-ACCATCAATGAGGCTAAGCCAGAATGGGATAGATGTCAT-3′ (EspI). The resulting products were digested only with EspI and religated. The ligated DNA was used as the template for a second round of PCR amplification with the upstream SacI and the downstream SpeI primers. The product was digested with SacI and SpeI and cloned into equivalent sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag, M1.HCΔ4 contains two foreign residues (Lys-Glu), whereas M1.HCΔ5 contains three extra amino acids (Thr-Lys-Pro) at the site of the deletion.

Capsid and nucleocapsid deletion mutants M1.HCΔ6, M1.HCΔ7, M1.HCΔ8, and M1.HCNCΔ were created by PCR amplification of fragments from the capsid and the nucleocapsid sequence of pSV.M1.HIV Gag, using the upstream primers 5′-AGAATGTATACTAGTACCAGCATTCTGGACATA-3′ (SpeI), 5′-AAGAGCCGAGACTAGTTCACAGGAGGTAAAAAT-3′ (SpeI), 5′-AGAAGAAATGACTAGTGCATGTCAGGGAGTAGGA-3′ (SpeI), and 5′-CAGAGAGGCACTAGTAGGAACCAAAGAAAGATT-3′ (SpeI), respectively. Construction of these mutants used the downstream BssHII primer described earlier. Following digestion with SpeI and BssHII, the PCR products were ligated into the SpeI-BssHII sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag.

Nucleocapsid mutant M1.HNCΔ was constructed by digesting pSV.M1.HIV Gag with ApaI and BglII, treating it with T4 DNA polymerase, and religating the DNA.

To make M1.HΔSP1 in which the coding sequence for SP1 is deleted, two PCR amplifications of nucleotides 1096 to 1465 and 1510 to 2050 of gag from pSV.M1.HIV Gag were performed to create a PstI site at the site of the deletion, using the following upstream and downstream primers: 5′-GAACTACTAGTACCCTTC-3′ (SpeI) with 5′-TCATTGCTTCCTGCAGAACTCTTGCCTTATGGCC-3′ (PstI) and 5′-ACCATAATGCTGCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGG-3′ (PstI) with the downstream BssHII primer described above. The resulting products were digested with PstI and religated. The ligated DNA was used as the template for a second round of PCR amplification with upstream SpeI and downstream BssHII primers. The product was digested with SpeI and BssHII and cloned into equivalent sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag. One foreign residue (Leu) was introduced at the site of the deletion.

Construction of p6 deletion mutants.

To make SP2/p6 deletion mutants pSV.HIV.Δp6 (BglII) and pSV.M1.HIV.Δp6 (BglII), pSV.HIV Gag and pSV.M1.HIV Gag, respectively, were digested with BglII, treated with Klenow enzyme, digested with BssHII, and religated.

Two other p6 deletion mutants were constructed: M1.HIVΔp6 (stop codon TAA created in place of the p6 initiator CTT) and M1.HIVΔLeuT (stop codon created just downstream of the PEPTAP motif located in the p6 sequence). M1.HIVΔp6 was made by annealing overlapping oligonucleotides 5′-GATCTGGCCTTCCTACAAGGGAAGGCCAGGGAATTTTTAAG-3′ and 5′-CGCGCTTAAAATTCCCTGGCCTTCCCTTGTAGGAAGGCCA-3′ to give a double-stranded DNA fragment with 5′ BglII and 3′ BssHII sticky ends. The oligonucleotide pair was cloned into the BglII and BssHII sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag. To make M1.HIVΔLeuT, nucleotides downstream of the PEPTAP motif were removed from pSV.M1.HIV Gag by PCR with upstream primer 5′-TTTAGGGAAGATCTGGCCTTCCTACAAGGGA-3′ (BglII) and downstream primer 5′-ATAGCTTTAGCGCGCCTATGGGGCTGTTGGCTCTGG-3′ (BssHII). The amplified fragment was digested with BglII and BssHII and ligated into plasmid pSV.M1.HIV Gag which had been digested with the same enzymes.

To make pSV.M1.Gag.P10L, pSV.M1.Δp6.32-47, pSV.M1.Δp6.35-47, pSV .M1.Δp6.38-47, and pSV.M1.Δp6.43-52, we used pTM-p6(P10L), pTM-GAG(p632-47), pTM-GAG(p635-47), pTM-GAG(p638-47), and pTM-GAG (p643-52) (35) (kindly provided by Lee Ratner, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.), respectively. These were digested with SalI, treated with Klenow enzyme, and digested with SpeI. The resulting fragments were ligated into the BssHII site, which had been treated with Klenow enzyme, and the SpeI site of pSV.M1.HIV Gag.

pSV.M1.Δp6.19-52 was constructed by insertion of a PCR product with nucleotides 2567 to 2840 of gag from pSV.M1.HIV Gag, obtained with the upstream primer 5′-TTAGGGAAGATCTCAGTAGAGACAACAACTCCCCCT-3′ (BglII) and the downstream BssHII primer described above. The resulting fragment was digested with BglII and BssHII and cloned into the BglII and BssHII sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag. pSV.M1.Δp6.32-52 was constructed by a similar strategy with nucleotides 2605 to 2840, using the upstream primer 5′-TTAGGGAAGATCTCAGACAAGGAACTGTATCCTTTA-3′ (BglII) and the same downstream primer. In both constructs, an extra amino acid (Ser) is inserted between the HIV-1 Gag spacer region and p6 sequences.

pSV.M1.Gag.P5A and pSV.M1.Gag.P7A have mutations in the PEPTAP motif. The following upstream primers were used to introduce mutations changing PEPTAP to AEPTAP (P5A) and PEPTAP to PEATAP (P7A); 5′-TAGGGAAGATCTGGCCT TCC TACAAGGGAAGGCCAGGGAAT T T TCT TCAGAG CAGAGCAGAGCCAACA-3′ (BglII) and 5′-TAGGGAAGATCTGGCCTTCCTACAAGGGAAGGCCAGGGAATTTTCTTCAGAGCAGACCAGAGGCAA CAGCCCCA-3′ (BglII), respectively. Construction of these mutants used the downstream BssHII primer described earlier. The resulting PCR products were digested with BglII and BssHII and cloned into the BglII-BssHII sites of pSV.M1.HIV Gag.

Chimeric RSV-HIV gag alleles.

Several of the chimeras used in this study (Fig. 7) have been previously reported: pSV.Myr1.R-3J (53), pSV.Myr0.LOC7 (34), pSV.T10C.p6 (37), pSV.RHE.T10C- (37), and pSV.RHB (2).

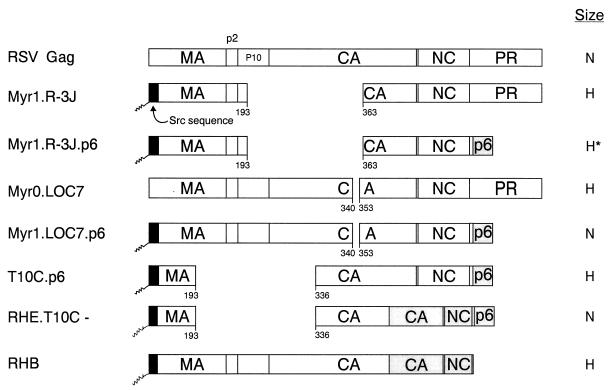

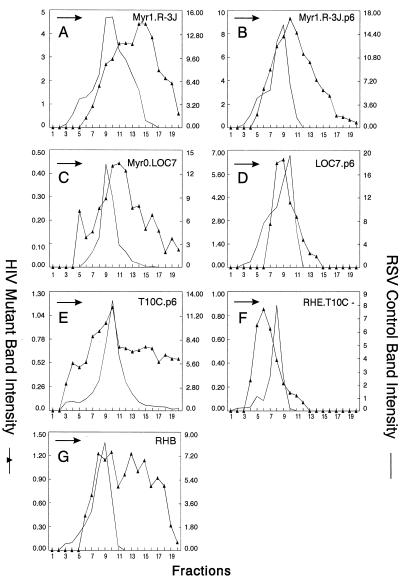

FIG. 7.

Schematic diagrams of chimeric RSV-HIV Gag proteins. The wild-type RSV Gag protein (open box) is shown at the top. The names of the Gag cleavage products (MA, p2, p10, CA, NC, and PR) are indicated. Shaded boxes represent HIV-1 sequences. The black boxes at the N termini of the constructs depict the first 10 amino acids from pp60v-scr. The squiggle indicates the fatty acid myristate. Numbers refer to amino acid residues. The column at the right summarizes the size distribution of the mutants: N, homogeneous particles of normal size; H, particles that are heterogeneous in size; H*, particles more normal but still heterogeneous.

pSV.Myr1.Loc7.p6 and pSV.Myr1.R-3J.p6 were created by digesting Myr1.Loc7 and Myr1.R-3J with SacI and BglII, respectively. The resulting fragments were ligated into the SacI-BglII sites of pSV.RH.p6 (2).

Transfection of cells and metabolic labeling.

COS-1 cells were grown in 60-mm-diameter dishes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum and 7% bovine calf serum (HyClone, Inc.). Authentic retroviruses for use as an internal control in sucrose gradients were obtained from RSV-infected turkey embryo fibroblasts which were propagated in supplemented F10 medium as described previously (25). COS-1 cells were transfected with XbaI-digested and ligated plasmids by the DEAE-dextran-chloroquine method as described previously (52). At 48 h after transfection, COS-1 cells were labeled with [35S]methionine (50 μCi; >1,000 Ci/mmol). After 2.5 h of labeling, the cells and growth medium from each labeled culture were mixed with lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, and the Gag proteins were immunoprecipitated at 4°C with a human HIV immunoglobulin (41), electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gels, and visualized by fluorography. The autoradiograms were then quantitated by laser densitometry.

Sucrose gradient analysis.

Two days posttransfection, COS-1 cells were labeled in methionine-free, serum-free Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with [35S]methionine (50 μCi; >1,000 Ci/mmol) for 5 h in 0.5 ml (for velocity gradients) or 8 h in 1.0 ml (for isopycnic gradients). After the labeling period, the medium was immediately centrifuged at a low speed to remove cellular debris. Infectious RSV was added to each sample to provide an internal control. This virus was grown in turkey embryo fibroblasts and labeled with [35S]methionine as described above. Each mixture was layered onto 10 to 30% sucrose (for velocity gradients) or 10 to 50% (for isopycnic gradients) and centrifuged at 83,500 × g for 0.5 h (for velocity gradients) or 16 h (for isopycnic gradients) in a Beckman SW41Ti. Then 0.6-ml fractions were collected from each gradient. Gag proteins in every fraction were immunoprecipitated with a mixture containing a rabbit antiserum against RSV and a human HIV immunoglobulin (41) and subjected to electrophoresis. All gradients were repeated at least once to confirm the results.

RESULTS

In an attempt to map size determinants of the HIV-1 Gag protein, a series of gag deletions was generated, and particles produced by these mutants were analyzed in rate zonal gradients. In the interpretation of the gradients, the peak positions of the deletion mutants relative to the internal control and the distribution of the particles within the gradient are more important indicators of particle size, mass, or shape than are the heights of the peaks. The gradient analyses were performed a minimum of two times for each mutant, and representative data for each are presented here.

Expression of full-length Pr55gag.

By using a transient expression system described previously for RSV (52), the HIV-1 Gag protein was expressed in simian cells without any other viral products. Expression was made possible by using a Rev-independent mutant (46). COS-1 cells transfected with the wild-type construct produced a protein with the expected size (55 kDa) both in cell lysates and in the culture medium (Fig. 1B, lane 4). Because the coding region for HIV-1 protease is not present, no smaller protein species were observed. However, Pr55gag appeared not to be very proficient in its ability to induce budding compared with RSV Gag (PR deletion mutant 3h [50]) (Fig. 1B, lane 3). In an attempt to enhance the rate of budding, the 32-residue-long M domain of HIV-1 Gag (38, 57) was replaced by the N-terminal M domain of the Src oncoprotein. The first few amino acids of the Src protein have been previously used to direct heterologous proteins to the plasma membrane including RSV Gag (39, 52, 53). The chimeric Gag protein was named M1.HIV Gag (Fig. 1A). In COS-1 cells, the M1 protein was produced at higher levels and directed the rapid release of viruslike particles into the growth medium (Fig. 1B, lane 5). All mutants used in this study have the first 10 residues of Src, except mutant pSV.Myr0.LOC7, which is a RSV Gag construct (34).

The densities of the proteins released into the medium by wild-type HIV Gag (1.17 g/ml) and M1.HIV Gag (1.17 g/ml) were found to be similar to those of authentic RSV particles (1.15 to 1.18 g/ml [12]) when analyzed in 10 to 50% isopycnic sucrose gradients (Fig. 1C).

When particle size was analyzed in 10 to 30% rate zonal gradients, wild-type particles and M1.HIV particles were homogeneous and sedimented one or two fractions more slowly than authentic RSV virions (Fig. 1C). This difference may be explained by the lack of viral components other than Gag and/or the smaller size of HIV-1 Gag compared to RSV Gag (500 versus 701 residues, respectively). That is, if RSV and HIV particles contain the same number of Gag proteins, then the molecular weight of an HIV particle would be 30% less than that of an RSV particle and hence sediment more slowly. From the protein profiles, we can conclude that the size distributions of the wild-type and M1.HIV particles are identical to one another, implying that the addition of the Src M domain to the N terminus of Gag influences neither particle size nor density. It should be noted that the sedimentation profile of wild-type virions does not necessarily imply a completely homogeneous distribution of particles. Electron microscopy (EM) analyses have shown that authentic HIV-1 particles vary in diameter between 90 and 160 nm (43), 95 and 175 nm (15), or 120 and 260 nm (16). The explanation for this heterogeneity is unknown and is not the focus here. Rather, the goal of the following experiments was to identify the regions of HIV Gag that prevent even larger and more heterogeneous particles from being released.

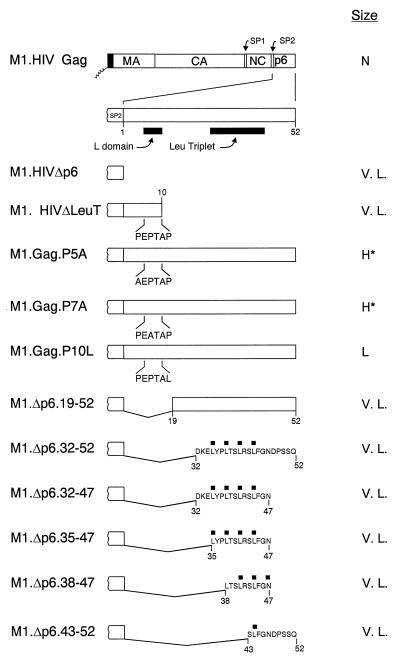

MA deletion mutants.

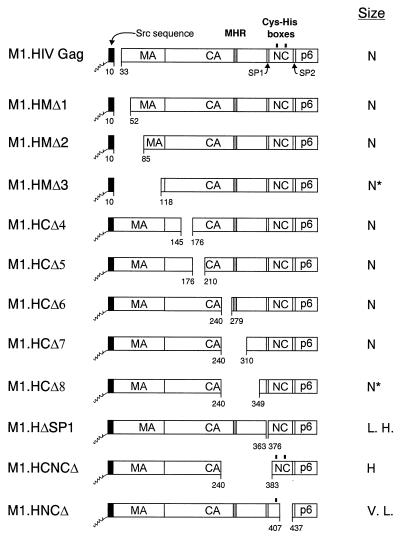

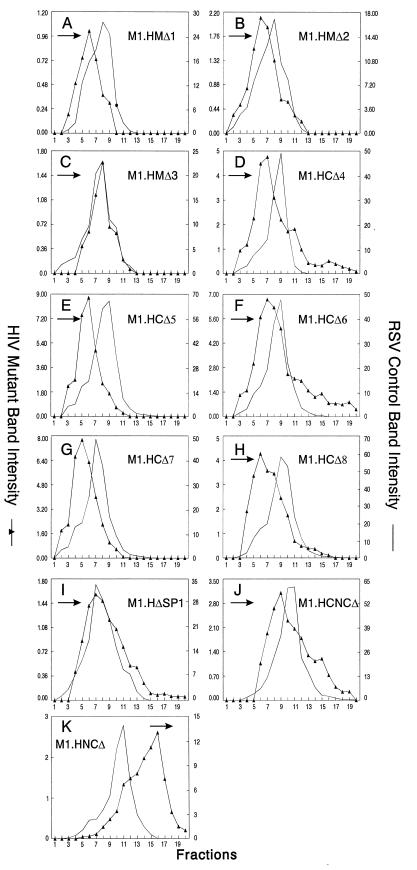

In RSV, the MA sequence has little influence on particle size (34), and the normal size distribution observed for deletion mutant M1.HIV suggested that this might be the case for HIV, too. To address this further, mutants with extensive deletions in MA were made. M1.HMΔ1, lacks the residues from 1 to 52; M1.HMΔ2 lacks the amino acids from 1 to 85; and in M1.HMΔ3, almost the entire MA sequence is deleted (Fig. 2). Each of these MA mutants released particles at approximately wild-type levels (i.e., the amount of Gag in the medium was reduced about twofold [data not shown]). The particles produced by M1.HMΔ1 and M1.HMΔ2 were homogeneous, uniform in size, and identical to wild-type HIV particles (i.e., slightly smaller than the control RSV particles) (Fig. 3A and B). In the case of M1.HMΔ3, mutant particles sedimented slightly faster (i.e., with the control particles) (Fig. 3C). The explanation for this minor shift is not understood, but it may be that the large deletion in the MA domain slightly alters the overall conformation of the protein. Therefore, it appears that the HIV-1 MA domain does not greatly influence particle size.

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagrams of deletion mutants of M1.HIV Gag. The names of the Gag cleavage products (MA, CA, NC, and p6) are indicated. The shaded region within CA marks the MHR. The black boxes at the N termini of the constructs represent the first 10 amino acids from pp60v-scr. The squiggle depicts the fatty acid myristate. The black rectangles above the Gag proteins M1.HIV Gag, M1.HCNCΔ, and M1.HNCΔ mark the cysteine-histidine boxes. The two arrows beneath M1.HIV Gag protein indicate the spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2). Numbers refer to amino acid residues. The column at the right summarizes the size distribution of the mutants: N, homogeneous particles of normal size; N*, homogeneous particles that are slightly smaller; L. H., large particles that are heterogeneous in size; H, particles that are heterogeneous in size; V. L., homogeneous particles of very large size.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of particle size in rate zonal gradients. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated deletion mutant DNAs and labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 h. After the labeling period, particle sizes were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the direction of sedimentation.

CA and SP1 deletion mutants.

The CA-SP sequence of RSV is critical for normal size, and small deletions throughout it have dramatic effects resulting in large, heterogeneously sized particles (34). To see whether this is true for HIV, we next analyzed mutants that lack various amounts of the CA sequence. M1.HCΔ4, M1.HCΔ5, and M1.HCΔ6 have deletions N terminal to the major homology region (MHR) (Δ145-176, Δ176-210, and Δ240-279, respectively [Fig. 2]). The deletions in M1.HCΔ7 and M1.HCΔ8 removed the MHR or the C-terminal part of CA (Δ240-310 and Δ240-349, respectively [Fig. 2]). Since none of the capsid deletions greatly affected the efficiency of particle release (i.e., the amount of Pr55gag was reduced about two- to threefold [data not shown]), the particles were examined in rate zonal gradients. Surprisingly, the sedimentation profiles for these mutants were identical to that for the wild type (Fig. 3D to H), with the exception of the mutant with the largest deletion, M1.HCΔ8, whose peak was shifted to a position one fraction higher in the gradient than the other CA mutants. The reduced sedimentation rate for the latter mutant is consistent with the reduced mass of Gag. Thus, it appears that the CA sequence, including the MHR, is not important for HIV particle size.

To address whether SP1 is critical for particle size, we made a mutant lacking the entire SP1 sequence (M1.HΔSP1 [Fig. 2]). The amount of Pr55gag was reduced about two- to threefold as a consequence of the deletion (data not shown). M1.HΔSP1 produced larger particles with a broader peak (Fig. 3I), suggesting that SP1 may play a role in determining the size of an HIV particle. However, the size heterogeneity seen with M1.HΔSP1 is much less drastic than those reported for RSV CA-SP1 mutants (34). Altogether, these results point to a fundamental difference between oncoviruses and lentiviruses (see Discussion).

NC deletion mutants.

Although the NC sequence does not provide a size determinant in RSV, it promotes the interactions between the neighboring CA-SP domains (34). To produce particles of uniform and homogeneous size, the RSV Gag protein must have an intact CA-SP domain and at least one copy of the I domain, suggesting that CA and NC function as a unit (34). To address whether this is the case for HIV, we next analyzed two NC deletion mutants. Both constructs produced particles of normal density when analyzed in 10 to 50% isopycnic sucrose gradients (data not shown). M1.HCNCΔ contains a deletion which removes a portion of the CA upstream of the MHR along with SP1 and the first six residues from NC (Δ240-383 [Fig. 2]). This deletion did not significantly affect particle release (the amount of Pr55gag was reduced about twofold [data not shown]). This NC mutant produced relatively heterogeneously sized particles (Fig. 3J), suggesting again that SP1 might be critical for particle size.

A very different result was obtained with mutant M1.HNCΔ. This mutant lacks the second half of the NC sequence and the first four residues of SP2 (Δ407-437 [Fig. 2]), but the mutant retains I domain activity and, as mentioned above, produces particles of normal density. The amount of Pr55gag was reduced about sixfold as a consequence of this deletion (data not shown). M1.HNCΔ produced homogeneous but very large particles (Fig. 3K) and thus is obviously defective for an important size determinant located within NC and/or SP2 sequences. Our next step was to analyze the size distributions of SP2 and p6 deletion mutants.

SP2 and p6 deletion mutants.

To examine the role of SP2 and p6 in particle size, two constructs with identical deletions of the entire p6 sequence and 11 residues of SP2 were made (Fig. 4A). In HIV.Δp6 (BglII), the wild-type M domain is present, whereas in M1.HIV.Δp6 (BglII), the M domain is replaced by the first 10 residues of the Src protein (Fig. 4A). As reported by many other groups, deletions of p6 and SP2 did not affect particle release, even though the L domain is missing (22–24, 26, 35, 44). Moreover, the densities of the HIV.Δp6 (BglII) (1.18 g/ml) and M1.HIV.Δp6 (BglII) (1.18 g/ml) particles were found to be similar to those of RSV authentic retrovirions when analyzed in 10 to 50% isopycnic sucrose gradients (Fig. 4B). However, rate zonal gradient analysis revealed that particles lacking SP2 and p6 were very large but uniform in size (Fig. 4B). The similarity of these two mutants rules out the possibility that the first few amino acids of the Src protein are responsible for the release of uniform but larger particles. Therefore, these data suggest that SP2 or/and the p6 sequences play an active role in constraining particle size.

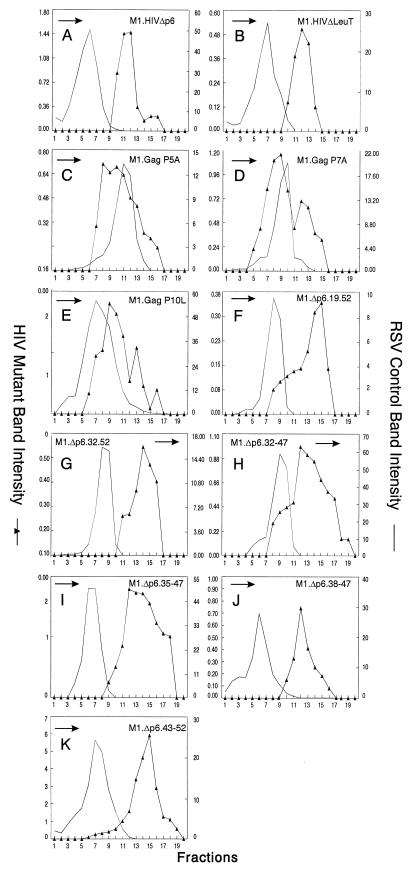

FIG. 4.

Deletion of the HIV-1 (SP2/p6) sequence. (A) The wild-type HIV Gag protein is shown at the top. HIV.Δp6 (BglII) is a designation of the wild-type HIV Gag protein deleted of SP2 and the p6 sequence by using the BglII site. In M1.HIV.Δp6 (BglII), the black box at its N terminus represents the first 10 residues of pp60v-scr. The squiggle depicts the fatty acid myristate. The names of the Gag cleavage products (MA, CA, NC, and p6) are indicated. The two arrows above the wild-type HIV Gag protein show the spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2). Numbers refer to amino acid residues. (B) The graphs represent the measurement of particle density in isopycnic sucrose gradients and the distribution of particle size in rate velocity gradients. COS-1 cells were transfected with pSV.HIV.Δp6 (BglII) or pSV.M1.HIV.Δp6 (BglII), and particle sizes and densities were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the direction of sedimentation.

Smaller deletions within p6.

To address the question of whether SP2 was a determinant of HIV-1 particle size by itself, M1.HIVΔp6 (Fig. 5) was constructed to express a truncated polyprotein missing only the p6 sequence. The particles released by this mutant were again uniform but very large (Fig. 6A). Therefore, the presence of SP2 in M1.HIVΔp6 is not sufficient to obtain normally sized particles.

FIG. 5.

Schematic diagrams of smaller p6 deletion mutants. M1.HIV Gag protein is shown at the top. The names of the Gag cleavage products (MA, CA, NC, and p6) are indicated. The black box at its N-terminus represents the first 10 amino acids from pp60v-scr. The squiggle represents the fatty acid myristate. The two arrows above the wild-type Gag protein indicate the spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2). The black rectangles beneath the p6 sequence indicate the L domain and the leucine triplet region. The various deletion mutants of M1.HIV Gag are illustrated below, and the residues retained in the p6 sequence are shown. The PEPTAP motif and the mutations within this motif are shown beneath the Gag proteins M1.HIVΔLeuT, M1.Gag.P5A, M1.Gag.P7A, and M1.Gag.P10L. The squares above the Gag proteins M1.Δp6.32-52, M1.Δp6.32-47, M1.Δp6.35-47, M1.Δp6.38-47, and M1.Δp6.43-52 mark the leucine residues. Numbers refer to amino acid residues. The column at the right summarizes the size distribution of the mutants: N, homogeneous particles of normal size; V. L., homogeneous particles of very large size; H*, particles that are heterogeneous in size (normal peak); L, particles of larger size.

FIG. 6.

Distribution of particle size in rate zonal gradients. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated smaller p6 deletion mutant DNAs and labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 h. Particle sizes were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows indicate the direction of sedimentation.

Since SP2 had no effect on particle size by itself, we next tried to map a subdomain in p6 that controls HIV-1 particle size. Previously published data have shown that the HIV-1 L domain, located near the beginning of the p6 sequence, is a small proline-rich motif (P7-T8-A9-P10) required late in budding (20, 37). It was of interest to determine whether this domain is solely involved in particle size. To address this, we constructed M1.HIVΔLeuT, in which amino acid residues 12 to 52 of p6 were deleted (insertion of a stop codon just downstream of the PTAP motif [Fig. 5]). The particles released by this mutant were homogeneous but larger than wild-type particles (Fig. 6B), indicating that the L domain does not alone constrain particle size. We also made single amino acid substitutions in the wild-type PEPTAP sequence to create AEPTAP (P5A), PEATAP (P7A), and PEPTAL (P10L) (Fig. 5). These mutants had smaller but obvious effects, and the particles appeared in broad peaks that overlapped the internal control (Fig. 6C and D). Particles produced by M1.Gag P10L were noticeably larger than wild-type HIV particles (Fig. 6E).

To determine whether the C-terminal sequence of p6 can alone control particle size, we next generated two N-terminal deletion mutants (M1.Δp6.19-52 and M1.Δp6.32-52 [Fig. 5]). Particles released were again uniform but very large (Fig. 6F and G). We also addressed whether sequences essential for the incorporation of Vpr into particles were important for controlling particle size. Previous studies demonstrated that the region of p6 involved in Vpr packaging contains an (LXX)4 domain (31, 35). Moreover, all four LXX motifs are required for this function (35). The constructs deleted of the entire or some parts of this region (Fig. 5) displayed the same phenotype as the previous p6 deletion mutants (Fig. 6H to K). Thus, we were unable to map a subdomain in p6 that is responsible for particle size. Altogether, these results indicate that SP2 is not a determinant of HIV-1 size particle by itself and the folded structure of the entire p6 sequence is required to constrain the size of the emerging particle.

Can p6 influence the particle size of other retroviruses?

To test the hypothesis that the p6 sequence provides a size determinant, chimeric Gag expression constructs were generated by combining portions of the gag genes of RSV and HIV-1 (Fig. 7). Recent studies of RSV have shown that the CA-SP sequence of RSV Gag is critical for the production of normally sized particles (34). Therefore, we added the entire p6 sequence to the C terminus of three previously described RSV Gag proteins containing either large (R-3J and T10C-) or small (LOC7) internal capsid deletions that produce heterogeneously sized particles (R-3J and LOC7 [Fig. 8A and C]). Mutant T10C- has no L domain and so is defective for particle release (50, 53); however, budding is restored when the p6 sequence and its associated L domain is placed at the C terminus of this mutant (37).

FIG. 8.

Distribution of particle size in rate zonal gradients. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated chimeric RSV-HIV mutant DNAs and labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 h. Particle sizes were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. For pSV.Myr0.LOC7, the internal control used was Myr1.D37S (34). Arrows indicate the direction of sedimentation.

The LOC7.p6 chimera was found to release particles of uniform size (compare Fig. 8C and D). Chimera R-3J.p6 did not produce particles as heterogeneous in size as the R-3J parent particles but had a broad peak that overlapped control particles (compare Fig. 8A and B). These data suggest that the HIV p6 sequence alone can dramatically reduce the heterogeneity of RSV capsid mutants when placed at the C terminus of Gag, and the effect of p6 is most noticeable with the small CA deletions. The p6 sequence alone did not reduce the heterogeneity seen with the largest internal CA deletion mutant (T10C.p6 [Fig. 8E]); however, when HIV sequences adjacent to p6 were included (RHE.T10C- [Fig. 7]), the T10C particles were normal in size (Fig. 8F). These data illustrate the importance of the C-terminal sequences of HIV Gag in constraining particle size. The importance of the p6 sequence is once again emphasized by chimera RHB (Fig. 7), an RSV-HIV chimera that lacks the p6 sequence and does not contain the RSV size determinant (CA-SP). As expected, RHB particles were found to be heterogeneous in size (Fig. 8G).

DISCUSSION

The experiments described in this report give insight into the location of the size determinants within HIV-1 Gag protein. We showed that a fully intact HIV-1 Gag polyprotein is not required for normal particle size and that the size-controlling elements are contained exclusively within the C-terminal sequences of Gag. A particularly important function resides within the entire p6 sequence.

To locate the size determinants of HIV-1 Gag, we chose to use the rate zonal sedimentation method rather than EM analysis. The main advantage of the sucrose gradient approach is that the entire population of particles is visualized regardless of their morphological appearance. By EM, abnormally sized particles might not be recognized as being of viral origin. However, the principal disadvantage of the sucrose gradient technique is that variations in sedimentation rate do not allow easy calculation of the actual size of the particles. The relationship of size to sedimentation rate is not linear, and small shifts in the peak positions represent larger differences in size. Therefore, it will be interesting to determine the exact morphology of the particles produced by the different deletion mutants by EM analysis. In addition, gradient sedimentation does not reveal the heterogeneity of particle size that exists even in wild-type HIV particles (15, 16, 42). Nevertheless, this method does allow mapping of the most important determinants of particle size, ones whose absence leads to dramatically different sedimentation profiles.

The entire HIV-1 Gag protein is not required for normal particle size.

The finding that the main region critical for determining HIV-1 particle size resides in the NC and p6 sequences is surprising. Our results are very different from those of a recent study carried out with RSV, in which it was shown that CA and the spacer peptides between CA and NC are important for controlling the size of the emerging particle (34). Although systematic mapping for size determinants of the HIV-1 Gag protein has not been reported, there is one discrepancy between our results and previously published work. Kraüsslich et al. (33) have reported that particles released by an SP1 deletion mutant identical to ours are extremely heterogeneous in size. In their experiment, no internal control was used for the rate zonal gradients, and hence the quality of the gradient is unknown. The size heterogeneity seen with our SP1 deletion mutant is much less drastic, although we did observe a minor effect. Our results are more similar to the results from another recent study which also concluded from several linker insertion mutants that, in addition to SP1, the N-terminal and middle region of CA are not important for particle size (43). That study also showed that these regions are critical for the formation of morphologically normal virions (43), and we predict that our more severely altered CA-SP mutants would also have abnormal core morphology within normal-size particles.

Our results with the capsid deletion mutants clearly demonstrate that the HIV-1 CA is not required for determining particle size and also that the majority of the capsid region (between residues 14 and 218), including the MHR, can be removed without greatly affecting budding and release of the Pr55gag precursor. Previously, a number of studies found that some residues throughout the capsid protein might be critical for particle release (8, 15, 29). Others reported that the capsid region is not essential for release (42, 48, 49). Our data are in agreement with those of these latter studies as well as those of RSV which indicate that large deletions of Gag protein do not affect budding (54).

A new role of HIV-1 p6?

Previously, two functions for the p6gag protein have been proposed. p6 appears to be required for the incorporation of the HIV-1 accessory protein Vpr into virions (31, 35). The sequence critical to this function has been mapped to the leucine triplet repeat located at the C-terminal part of p6 (31, 35). It has also been reported that the proline-rich region PTAP, located near the beginning of the p6 sequence and referred to as the L domain, plays a role in virus particle production at a late stage in the budding process (20, 37). The PTAP sequence fits the consensus of an SH3 ligand (9), suggesting that this sequence might interact with a cellular protein via the SH3 domain during the assembly process. In the experiments described here, our p6 deletion mutants produced particles at wild-type efficiencies, which is in agreement with the notion that the effects of p6 on virus release may be affected by PR or may be cell type specific (24, 27, 47). However, the particles released are tremendously larger in size, suggesting a difference in the budding mechanism in absence of p6 (leading to large particles) and/or the existence of another L domain located elsewhere in Gag.

How the p6 sequence functions to determine the normal size of the particles is unknown. One possibility is that the interaction between the L domain (motif PTAP) with a host protein is the determining factor leading to the release of a particle of normal size from the cell surface. In this study, we were unable to map a subdomain that is responsible for particle size, suggesting that the normal folded structure of this sequence is required. One explanation is that deletions in the C-terminal part of p6 might alter the overall conformation of p6 and hence might inhibit or greatly reduce the interaction of the PTAP motif with a cellular protein. To test the hypothesis that the L domain plays a role in determining the size of a particle, we are currently testing the ability of p2b from RSV and its associated L domain (54) to function in place of p6. Another possibility may be that the p6 protein will form an inner scaffold-like shell, although it has not been demonstrated that the p6 domain can interact with itself (e.g., formation of dimers).

The results with the RSV-HIV chimeras also suggest that the sequences upstream of p6 (i.e., the I domains present within NC) are necessary to constrain the size of the particle by providing protein-protein interactions during the assembly process. These strong interactions lead to the tight packing of Gag molecules.

Comparison of lentiviruses and oncoviruses.

Altogether, our results strongly suggest that the size-controlling elements are very different in oncoviruses and lentiviruses. Although this finding was unexpected at the outset of our experiments, it is not unreasonable in light of other known differences between these two groups of retroviruses. For example, EM analyses have shown that the immature particles of RSV and HIV have different morphologies. In HIV particles, the electron-dense layer resides tightly packed against the viral membrane, whereas in RSV there is an intermediate layer and the electron-dense material extends almost to the center of the particle (for a review, see reference 36). Although the arrangement of Gag proteins within the immature capsid has not been determined, one might expect the different morphologies in the immature virions to be greatly influenced by the CA sequence since it is the largest component of Gag. We also know that the inner cores of the mature capsids of RSV (spherical) and HIV (cone shaped) are very different, again suggesting that the CA interactions during the maturation of the particle may be different. Other differences have been found in cell fractionation experiments, where the CA protein of murine leukemia virus but not CA of HIV is found in preintegration complexes (3, 4). Finally, a p6-like sequence does not exist at the end of RSV Gag; rather, the viral protease resides at this location.

In summary, we present evidence that the p6 sequence provides a size determinant by itself, but we do not know how p6 acts to constrain the size of a retroviral particle. These results emphasize the need to find the host factors that interact with different L domains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Neel Krishna, George Pavlakis, and Yuh-Ling Lu for providing the RSV capsid deletion mutants, the Rev-independent mutant p17M1234, and some of the smaller p6 deletion constructs, respectively. Many thanks are also given to Leslie Parent and Tina Cairns for the M1.HIV construct and to Eric Callahan for the CA deletion constructs. We appreciate the time given by Leslie Parent and Neel Krishna for many helpful discussions. The HIV immunoglobulin (from A. Prince) was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health awarded to J.W.W (CA47482) and L.R. (AI36071 and AI34736) and by a grant from the American Cancer Society awarded to J.W.W (FRA-427). Support for L.G. was provided by Pasteur Merieux Connaught Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldovini A, Young R A. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1920-1926.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett R P, Nelle T D, Wills J W. Functional chimeras of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:6487–6498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6487-6498.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowerman B, Brown P O, Bishop J M, Varmus H E. A nucleoprotein complex mediates the integration of retroviral DNA. Genes Dev. 1989;3:469–478. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S, Dempsey M P, Sharova N, Adzhubel A, Spitz L, Lewis P, Goldfarb D, Emerman M, Stevenson M. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature (London) 1993;365:666–669. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, McDonald T I, Pushkarskaya T, Tarpley W G, Stevenson M. Association of integrase, matrix, and reverse transcriptase antigens of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with viral nucleic acids following acute infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6125–6129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell S, Vogt V M. Self assembly in vitro of purified CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6487–6497. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, S. Personal communication.

- 8.Chazal N, Carriere C, Gay B, Boulanger P. Phenotypic characterization of insertion mutants of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor expressed in recombinant baculovirus-infected cells. J Virol. 1994;68:111–122. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.111-122.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H I, Sudol M. The WW domain of Yes-associated protein binds a proline-rich ligand that differs from the consensus established for Src homology 3-binding modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7819–7823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craven R C, Bennett R P, Wills J W. Role of the avian retroviral protease in the activation of reverse transcriptase during virion assembly. J Virol. 1991;65:6205–6217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6205-6217.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craven R C, Parent L J. Dynamic interactions of the Gag polyprotein. In: Kraüsslich H-G, editor. Retroviral morphogenesis and maturation. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickson C R, Eisenman R, Fan H, Hunter E, Teich N. Protein biosynthesis and assembly. In: Weiss R, Teich N, Varmus H, Coffin J M, editors. RNA tumor viruses. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. pp. 513–648. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorfman T, Luban J, Goff S P, Haseltine W A, Gottlinger H G. Mapping of functionally important residues of a cysteine-histidine box in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6159–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6159-6169.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorfman T, Mammano F, Haseltine W A, Göttlinger H G. Role of the matrix protein in the virion association of the human immunodeficiency virus type I envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:1689–1696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1689-1696.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorfman T, Bukovsky A, Öhagen A, Höglund S, Göttlinger H G. Functional domains of the capsid protein of immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:8180–8187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8180-8187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller S D, Wilk T, Gowen B E, Kräusslich H-G, Vogt V M. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals ordered domains in the immature HIV-1 particle. Curr Biol. 1997;7:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnier L, Wills J W, Verderame M F, Sudol M. WW domains and retrovirus budding. Nature (London) 1996;381:744–745. doi: 10.1038/381744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gheysen D, Yancey R, Petrovskis E, Timmins J, Post L. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor Pr55gag virus-like particles from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Cell. 1989;59:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorelick R J, Henderson L E, Hanser J P, Rein A. Point mutants of Moloney murine leukemia virus that fail to package viral RNA: evidence for specific RNA recognition by a “zinc finger-like” protein sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8420–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlinger H G, Dorfman T, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Effect of mutations affecting the p6 Gag protein on human immunodeficiency virus particle release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3195–3199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson L E, Bowers M A, Sowder II R C, Serabyn S A, Johnson D G, Bess J W, Arthur L O, Bryant D K, Fenselau C. Gag proteins of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processing, and complete amino acid sequences. J Virol. 1992;66:1856–1865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1856-1865.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hockley D J, Nermut M V, Grief C, Jowett J B M, Jones I M. Comparative morphology of Gag protein structures produced by mutants of the gag gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2985–2997. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshikawa N, Kojima A, Yasuda A, Takayashiki E, Masuko S, Chiba J, Sata T, Kuryata T. Role of the gag and pol genes of human immunodeficiency virus in morphogenesis and maturation of retrovirus-like particles expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus: an ultrastructure study. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2509–2517. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang M, Orenstein J M, Martin M A, Freed E O. p6gag is required for particle production from full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones expressing protease. J Virol. 1995;69:6810–6818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6810-6818.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter E. Biological techniques for avian sarcoma viruses. Methods Enzymol. 1994;58:379–392. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(79)58153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jowett J B M, Hockley D J, Nermut M V, Jones I M. Distinct signals in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55 necessary for RNA binding and particle formation. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3079–3086. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan A H, Manchester M, Swanstrom R. The activity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated at the membrane of infected cells before the release of viral proteins and is required for release to occur with maximum efficiency. J Virol. 1994;68:6782–6786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6782-6786.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karacostas V, Nagashima K, Gonda M A, Moss B. Human immunodeficiency virus-like particles produced by a vaccinia virus expression vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8964–8967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karacostas V, Wolffe E J, Nagashima K, Gonda M A, Moss B. Overexpression of the HIV-1 Gag-Pol polyprotein results in intracellular activation of HIV-1 protease and inhibition of assembly and budding of virus-like particles. Virology. 1993;193:661–671. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl N E, Emini E A, Schleif W A, Davis L J, Heimbach J C, Dixon R A, Scolnick E M, Sigal I S. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondo E, Mammano F, Cohen E A, Gottlinger H G. The p6gag domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is sufficient for the incorporation of vpr into heterologous viral particles. J Virol. 1995;69:2759–2764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2759-2764.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraüsslich H G, Ochsenbauer C, Traenckner A M, Mergener K, Facke M, Gelderblom H R, Bosch V. Analysis of protein expression and virus-like particle formation in mammalian cell lines stably expressing HIV-1 gag and env gene products with or without active HIV proteinase. Virology. 1993;192:605–617. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraüsslich H G, Facke M, Heuser A-M, Konvalinka J, Zentgraf H. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:3407–3419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3407-3419.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishna N K, Campbell S, Vogt V M, Wills J W. Genetic determinants of Rous sarcoma virus particle size. J Virol. 1998;72:564–577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.564-577.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Y-L, Bennett R B, Wills J W, Gorelick R, Ratner L. A leucine triplet repeat sequence (LXX)4 in p6gag is important for Vpr incorporation into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1995;69:6873–6879. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6873-6879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nermut M V, Hockley D J. Comparative morphology and structural classification of retroviruses. In: Kraüsslich H-G, editor. Retroviral morphogenesis and maturation. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parent L J, Bennett R P, Craven R C, Nelle T D, Krishna N K, Bowzard J B, Wilson C B, Puffer B A, Montelaro R C, Wills J W. Positionally independent and exchangeable late budding functions of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J Virol. 1995;69:5455–5460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5455-5460.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parent L J, Wilson C B, Resh M D, Wills J W. Evidence for a second function of the MA sequence in the Rous sarcoma virus Gag proteins. J Virol. 1996;70:1016–1026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1016-1026.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellman D, Garber E A, Cross F R, Hanafusa H. An N-terminal peptide from p60src can direct myristylation and plasma membrane localization when fused to heterologous proteins. Nature (London) 1985;346:84–86. doi: 10.1038/314374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng C, Ho B K, Chang T W, Chang N T. Role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protease in core protein maturation and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1989;63:2550–2556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2550-2556.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince A M, Horowitz B, Baker L, Shulman R W, Ralph H, Valinsky J, Cudell A, Brotman B, Boehle W, Rey F, Barbosa L, Piet M, Reesink H, Lelie N, Tersmette M, Miedema F, Nemo G, Nastala C L, Allan J S, Lee D R, Eichberg J W. Failure of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) immune globulin to protect chimpanzees against experimental challenge with HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6944–6948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reicin A S, Paik S, Berkowitz R D, Luban J, Lowy I, Goff S P. Linker insertion mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene: effects on virion particle assembly, release, and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:642–650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.642-650.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reicin A S, Ohagen A, Yin L, Hoglund S, Goff S P. The role of Gag in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion morphogenesis and early steps of the viral life cycle. J Virol. 1996;70:8645–8652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8645-8652.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royer M, Cerutti M, Gay B, Hong S-S, Devauchelle G, Boulanger P. Functional domains of HIV-1 gag-polyprotein expressed in baculovirus-infected cells. Virology. 1991;184:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz S, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Harrison J, Felber B K, Pavlakis G. Mutational activation of an inhibitory sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in Rev-independent gag expression. J Virol. 1992;66:7176–7182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7176-7182.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spearman P, Wang J J, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J Virol. 1994;68:3232–3242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3232-3242.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srinivasakumar N, Hammarskjold M-L, Rekosh D. Characterization of deletion mutations in the capsid region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that affect particle formation and Gag-Pol precursor incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:6106–6114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6106-6114.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang C T, Barklis E. Assembly, processing, and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag mutants. J Virol. 1993;67:4264–4273. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4264-4273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weldon R A, Jr, Erdie C R, Oliver M G, Wills J W. Incorporation of chimeric Gag protein into retroviral particles. J Virol. 1990;64:4169–4179. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4169-4179.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weldon R A, Jr, Wills J W. Characterization of a small (25-kilodalton) derivative of the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein competent for particle release. J Virol. 1993;67:5550–5561. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5550-5561.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wills J W, Craven R C, Achacoso J A. Creation and expression of myristylated forms of Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein in mammalian cells. J Virol. 1989;63:4331–4343. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4331-4343.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wills J W, Craven R C, Weldon R A, Jr, Nelle T D, Erdie C R. Suppression of retroviral MA deletions by the amino-terminal membrane-binding domain of p60src. J Virol. 1991;65:3804–3812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3804-3812.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wills J W, Cameron C E, Wilson C B, Xiang Y, Bennett R P, Leis J. An assembly domain of the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein required late in budding. J Virol. 1994;68:6605–6618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6605-6618.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang Y, Ridky T W, Krishna N K, Leis J. Altered Rous sarcoma virus Gag polyprotein processing and its effects on particle formation. J Virol. 1997;71:2083–2091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2083-2091.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu X, Yuan X, Matsuda Z, Lee T-H, Essex M. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J Virol. 1992;66:4966–4971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4966-4971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou W, Parent L J, Wills J W, Resh M D. Identification of a membrane-binding domain within the amino-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein which interacts with acidic phospholipids. J Virol. 1994;68:2256–2269. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2556-2569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]