Abstract

Background

An earlier systematic review and meta-analysis found that patients with a certain histological variant of upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) exhibited more advanced disease and poorer survival than those with pure UTUC. A difference in the clinicopathological UTUC characteristics of Caucasian and Japanese patients has been reported, but few studies have investigated the clinical impact of the variant histology in Japanese UTUC patients.

Methods

We retrospectively enrolled 824 Japanese patients with pTa-4N0-1M0 UTUCs who underwent radical nephroureterectomy without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Subsequently, we explored the effects of the variant histology on disease aggressiveness and the oncological outcomes. We used Cox’s proportional hazards models to identify significant predictors of oncological outcomes, specifically intravesical recurrence-free survival (IVRFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and overall survival (OS).

Results

Of the 824 UTUC patients, 32 (3.9%) exhibited a variant histology that correlated significantly with a higher pathological T stage and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). Univariate analysis revealed that the variant histology was an independent risk factor for suboptimal RFS, CSS, and OS. However, significance was lost on multivariate analyses.

Conclusions

The variant histology does not add to the prognostic information imparted by the pathological findings after radical nephroureterectomy, particularly in Japanese UTUC patients.

Keywords: Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC), variant histology, oncological outcomes, Japanese patients

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Variant histology does not provide additional prognostic information beyond the pathological findings following radical nephroureterectomy in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC).

What is known and what is new?

• Pathologists widely recognize that certain histological variants of bladder urothelial carcinoma are associated with increased morphological aggressiveness and an unfavorable prognosis when compared to pure bladder urothelial carcinoma.

• There have been few reports on UTUC patients with variant histology due to its rarity.

• This study, using the largest database, investigates the impact of variant histology on the cancer outcomes of Japanese UTUC patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Patients with variant UTUCs tend to have higher pathological T stages and more lymphovascular invasion (LVI) than others. Consequently, variant histology does not contribute to predictive information beyond the pathological findings after radical nephroureterectomy.

Introduction

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is a rather uncommon malignancy that constitutes 5–10% of all urothelial carcinomas (1,2). After radical nephroureterectomy with excision of the bladder cuff, that is, the benchmark treatment for clinically non-metastatic disease, a substantial proportion of individuals with UTUC experience recurrence and metastasis (2). Several studies have revealed that the prognostic factors include tumor stage, lymph node involvement, and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (3,4).

Bladder urothelial carcinoma associated with a certain histological variant is widely recognized by pathologists to exhibit a propensity toward heightened morphological aggressiveness and an unfavorable prognosis relative to that of patients with pure bladder urothelial carcinoma (5,6). On the contrary, due to its infrequency, few reports have evaluated UTUC patients with the variant histology (7-9). Thus, the conclusions of the studies vary, and the findings thus remain controversial.

The incidence of UTUC varies geographically, being higher in Taiwan and the Balkan countries than elsewhere (10). The clinicopathological characteristics differ markedly between Caucasian and Japanese patients (11), emphasizing the need for race-specific data. Here, we explored the oncological outcomes associated with the histological variant of UTUC among Japanese patients. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-23-561/rc).

Methods

Patients

We enrolled patients who underwent radical nephroureterectomy from January 2012 to December 2021 at the Jikei University Hospital and 16 affiliated facilities of the JIKEI YAYOI Collaborative Group. Patients exhibiting the following characteristics were excluded: A lack of clinical detail (n=32), pathological T0 status (n=2), indeterminate pathological findings (n=2), and non-urothelial carcinomas (n=39). After excluding patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=74), 824 patients were included in the final total. All were operated upon by genitourinary surgeons via either an open or laparoscopic approach based on the preferences of both the patients and surgeons. All institutions performed standard radical nephroureterectomies with excision of the bladder cuffs. The detailed executions and the extents of lymph node dissection were at the discretion of the physicians. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Jikei University Institutional Review Board [approval No. 33-260(10878)] and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Clinicopathological data

We recorded baseline demographics and clinicopathological features, operative and management details, and follow-up and oncological outcomes. Patients were classified into either pure or variant UTUC groups based on histological differentiation status. Tumor staging was conducted as suggested by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th ed., 2017). LVI was defined as tumor cells within the endothelial linings of vascular or lymphatic channels. Tumor grading and variant classification were performed as suggested by the 2016 document of the World Health Organization (12).

Outcomes

Intravesical recurrence (IVR) was defined as urothelial recurrence in the bladder. Recurrence was defined as recurrent disease outside the urinary tract and bladder. Routine monitoring included complete blood counts, liver and kidney function tests, chest X-rays, urine cytology, cystoscopy, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) at 3–6-month intervals for the first 2 years and at 6-month intervals thereafter.

Statistical analysis

The associations between histological variants and clinicopathological variables were evaluated using the chi-squared test or the Fisher exact test. IVR-free survival (IVRFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and overall survival (OS) (all from the day of nephroureterectomy) were computed using the Kaplan-Meier method; log-rank comparisons were performed when necessary. Variables that affected the IVRFS, RFS, CSS, and OS were identified using Cox’s proportional hazards regression models. A P value less than 0.05 was taken to denote statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 13.1, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 824 included patients, 792 (96.1%) were diagnosed with pure UTUC and 32 (3.9%) with the histological variant including 23 (2.8%), 5 (0.61%), 3 (0.36%), and 1 (0.12%) case of squamous, glandular, sarcomatoid, and both squamous and glandular differentiation respectively. The median age was 74 years (range, 32–94 years). The overall median duration of follow-up was 28 months (range, 1–135 months) and the median follow-up of those alive at final follow-up was 30 months (range, 1–135 months). Lymph node dissection was performed on 289 patients (35.1%), of whom 62 (7.5%) exhibited lymph node involvement. Adjuvant chemotherapy was prescribed for 115 patients (14.0%) after radical nephroureterectomy. Table 1 compares the clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups. Patients with the variant histology exhibited a more advanced T stage (≥ pT3: 81.3% vs. 53.3%, P<0.001) and more LVI (LVI: 59.4% vs. 31.2%, P=0.003) than did those with pure UTUC.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

| Variable | All patients (n=824) | Pure UC (n=792) | UC with variant (n=32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year, median [range] | 74 [32–94] | 74 [32–94] | 78 [51–88] | 0.011 |

| Follow-up, month, median [range] | 28 [1–135] | 28 [1–135] | 16 [1–54] | 0.0002 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 588 (71.4) | 567 (71.6) | 21 (65.6) | 0.47 |

| Female | 236 (28.6) | 225 (28.4) | 11 (34.4) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 638 (77.4) | 617 (77.9) | 21 (65.6) | 0.25 |

| 1 | 150 (18.2) | 140 (17.7) | 10 (31.3) | |

| ≥2 | 36 (4.4) | 35 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Laterality, n (%) | ||||

| Right | 395 (47.9) | 379 (47.9) | 16 (50.0) | 0.81 |

| Left | 429 (52.1) | 413 (52.1) | 16 (50.0) | |

| Hydronephrosis, n (%) | ||||

| Absent | 397 (48.2) | 384 (48.5) | 13 (40.6) | 0.38 |

| Present | 427 (51.8) | 408 (51.5) | 19 (59.4) | |

| Operative method, n (%) | ||||

| Open | 236 (26.6) | 226 (28.5) | 10 (31.3) | 0.38 |

| Laparoscopic | 588 (71.4) | 566 (71.5) | 22 (68.7) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | ||||

| Renal pelvis | 399 (48.4) | 385 (48.6) | 14 (43.8) | 0.22 |

| Ureter | 374 (45.4) | 356 (44.9) | 18 (56.2) | |

| Both | 51 (6.2) | 51 (6.4) | 0 | |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | ||||

| Low grade | 157 (19.0) | 155 (19.6) | 2 (6.3) | 0.06 |

| High grade | 595 (72.2) | 566 (71.5) | 29 (90.6) | |

| NR | 72 (8.7) | 71 (9.0) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Pathological T stage, n (%) | ||||

| pTa/is/1 | 372 (45.1) | 367 (46.3) | 5 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| pT2 | 104 (12.6) | 103 (13.0) | 1 (3.1) | |

| pT3 | 308 (37.4) | 284 (35.9) | 24 (75.0) | |

| pT4 | 40 (4.8) | 38 (4.8) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Lymph node status, n (%) | ||||

| pN0 | 227 (27.5) | 219 (27.7) | 8 (25.0) | 0.73 |

| pN1–2 | 62 (7.5) | 58 (7.3) | 4 (12.5) | |

| pNx | 535 (64.9) | 515 (65.0) | 20 (62.5) | |

| Concomitant CIS, n (%) | ||||

| Absent | 696 (84.5) | 669 (84.5) | 27 (84.4) | >0.99 |

| Present | 128 (15.5) | 123 (15.5) | 5 (15.6) | |

| LVI, n (%) | ||||

| Absent | 559 (67.8) | 545 (68.8) | 13 (40.6) | 0.003 |

| Present | 265 (32.2) | 247 (31.2) | 19 (59.4) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | ||||

| Absent | 709 (86.0) | 683 (86.2) | 26 (81.3) | 0.425 |

| Present | 115 (14.0) | 109 (13.7) | 6 (18.7) |

UC, urothelial carcinoma; NR, not reported; CIS, carcinoma in situ; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

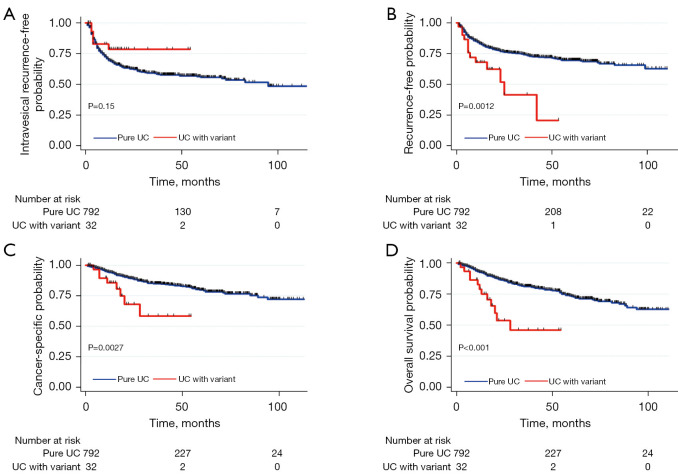

During follow-up, 294 (35.7%) patients developed IVR and 210 (25.5%) developed metastases. A total of 123 (14.9%) succumbed to cancer-specific mortality; 165 (20.0%) died of any cause. The 3-year IVRFS, RFS, CSS, and OS were 59.4%, 73.2%, 84.0%, and 79.8% respectively. The Kaplan-Meier curve for IVR indicated no significant difference between patients with or without the histological variant (P=0.15, Figure 1A). Conversely, the Kaplan-Meier curves revealed significantly inferior RFS, CSS, and OS in patients with than without the histological variant (P=0.0012, P=0.0027, and P<0.001 respectively) (Figure 1B-1D). The 3-year IVRFS rates were 58.8% for patients with pure UTUC and 78.2% for those with the histological variant. The 3-year RFS rates were 74.0% for patients with pure UTUC and 39.8% for those with the histological variant. The 3-year CSS rates were 84.7% for patients with pure UTUC and 57.8% for those with the histological variant. The 3-year OS rates were 81.0% for patients with pure UTUC and 45.5% for those with the histological variant.

Figure 1.

Intravesical recurrence-free (A), recurrence-free (B), cancer-specific (C), and overall (D) survival by variant histology status in 824 patients with upper tract urothelial carcinomas. UC, urothelial carcinoma.

Multivariate Cox’s regression analysis revealed that female gender [hazard ratio (HR) =0.51, P=0.008], hydronephrosis (HR =0.53, P=0.015), and adjuvant chemotherapy status (‘yes’) (HR =0.44, P=0.004) independently affected IVRFS. All of pT3, pN1–2, and LVI status independently impacted RFS (HR =2.12, P=0.011; HR =2.06, P=0.012; HR =2.68, P=0.001) and CSS (HR =2.33, P=0.022; HR =2.42, P=0.01; HR =2.21, P=0.002) respectively. Of these variables, pN1–2 and LVI status independently affected OS (HR =2.58, P=0.002; HR =2.57, P=0.001) (Table 2). The variant histology did not significantly influence any of IVRS, RFS, CSS, or OS (HR =0.84, P=0.69; HR =1.46, P=0.22; HR =1.56, P=0.26; HR =1.63, P=0.12).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis for survival.

| Covariant | References | Intravesical recurrence-free survival | Recurrence-free survival | Cancer-specific survival | Overall survival | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |||||

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.47 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.6 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.005 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 | 0.002 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | Male | 0.51 | 0.31–0.83 | 0.008 | 1.11 | 0.76–1.63 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.49–1.36 | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.04 | 0.075 | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||||||||||||

| ≥2 | 0–1 | 1.9 | 0.85–4.25 | 0.12 | 1.89 | 0.89–4.02 | 0.096 | 1.4 | 0.55–3.60 | 0.48 | 1.65 | 0.74–3.67 | 0.22 | |||

| Tumor location | ||||||||||||||||

| Ureter | Renal pelvis | 1.69 | 0.94–3.06 | 0.08 | 1.06 | 0.68–1.66 | 0.8 | 0.95 | 0.54–1.64 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.58–1.61 | 0.9 | |||

| Both | 2.43 | 1.17–5.06 | 0.017 | 1.04 | 0.49–2.21 | 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.24–2.18 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.37–2.31 | 0.87 | ||||

| Hydronephrosis | ||||||||||||||||

| Present | Absent | 0.53 | 0.32–0.89 | 0.015 | 0.91 | 0.59–1.40 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.50–1.47 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.52–1.38 | 0.51 | |||

| Pathological T stage | ||||||||||||||||

| ≥ pT3 | ≤ pT2 | 0.81 | 0.46–1.42 | 0.46 | 2.12 | 1.19–3.81 | 0.011 | 2.33 | 1.13–4.82 | 0.022 | 2.08 | 1.10–3.96 | 0.025 | |||

| Histology | ||||||||||||||||

| UC with variant histology | Pure UC | 0.84 | 0.36–1.97 | 0.69 | 1.46 | 0.80–2.67 | 0.22 | 1.56 | 0.72–3.39 | 0.26 | 1.63 | 0.89–3.01 | 0.12 | |||

| Lymph node status | ||||||||||||||||

| pN1–2 | pN0 | 0.82 | 0.33–2.06 | 0.68 | 2.06 | 1.17–3.62 | 0.012 | 2.42 | 1.24–4.74 | 0.01 | 2.58 | 1.40–4.75 | 0.002 | |||

| pNx | 1.22 | 0.78–1.93 | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.65–1.47 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.58–1.64 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 0.65–1.67 | 0.85 | ||||

| Concomitant CIS | ||||||||||||||||

| Present | Absent | 1.26 | 0.73–2.18 | 0.41 | 0.77 | 0.46–1.29 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.22–1.03 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.32–1.15 | 0.12 | |||

| LVI | ||||||||||||||||

| Present | Absent | 1.44 | 0.91–2.26 | 0.12 | 2.68 | 1.77–4.06 | 0.001 | 2.21 | 1.33–3.67 | 0.002 | 2.57 | 1.61–4.11 | 0.001 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||||

| Present | Absent | 0.44 | 0.26–0.77 | 0.004 | 0.87 | 0.58–1.30 | 0.49 | 1.3 | 0.80–2.14 | 0.29 | 1.18 | 0.75–1.84 | 0.48 | |||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; UC, urothelial carcinoma; CIS, carcinoma in situ; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

Discussion

The absence of conclusive evidence indicating that a variant histology should affect the management of UTUC poses challenges for clinicians. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the largest to date to evaluate the effects of the variant histology on the oncological outcomes of Japanese patients with UTUC. The variant histology was present in 3.9% of UTUC specimens, with prior series ranging from 3.6% to 24.2%, which is relatively lower than those reported in previous studies (7,13-18). The variant histology was associated with reduced RFS, CSS, and OS, but not IVRFS, after radical nephroureterectomy. However, multivariate analysis revealed that the variant histology was not associated with any survival after adjusting for clinicopathological factors. Patients with variant UTUCs tend to exhibit higher pathological T stages and more LVI than others. The inferior oncological outcomes associated with the variant histology are attributable to the higher pathological T stage and LVI. Thus, the variant histology does not add to the predictive information imparted by the pathological findings after radical nephroureterectomy. Although we did not evaluate the concordance of the detection of variant histology between the radical nephroureterectomy specimen and biopsy specimen, our findings reveal that valuable prognostic indicators of high risk are afforded by examining presurgical biopsy specimens.

Several studies have explored the clinical implications of the variant histology in terms of the oncological outcomes of UTUC patients. One meta-analysis of 26 studies involving 12,865 patients revealed that the variant histology was associated with a two-fold rise in cancer-specific mortality after radical nephroureterectomy (19). However, in this meta-analysis, the impact of variant histology on oncological outcomes focusing on Japanese patients were not investigated. Three reports have specifically examined the clinical impact of the variant histology in Japanese UTUC patients after radical nephroureterectomy (7,20,21). In the retrospective study of Sakano et al., the oncological outcomes of 502 patients with UTUC were examined; multivariate analysis revealed that the variant histology did not exhibit a significant association with inferior CSS (7). Murakami et al. studied the oncological outcomes of 37 patients with variant UTUC and 404 with pure UTUC (20). A multivariate analysis of factors affecting CSS indicated that the variant histology was not an independent predictor (20). Conversely, Takemoto et al. reported that, on multivariate analysis of 223 UTUC patients, the variant histology was an independent predictor of CSS (21). In our present study, as in Sakano et al.’s (7) and Murakami et al.’s studies (20), the variant histology was not a significant predictor of CSS on multivariate analysis. Eight other studies (22-29) included the variant histology when performing multivariate analysis. Only one study (25) found that the variant histology significantly affected the CSS of UTUC patients after radical nephroureterectomy. Therefore, although further clinical investigation would be required, as the difference of the clinicopathological characteristics of UTUC between Caucasian and Japanese patients were reported (11), the clinical impact of the variant histology may also differ.

Zamboni et al. explored CSS stratified by the variant histology including squamous, micropapillary, and sarcomatoid differentiation. Only the sarcomatoid variant was associated with an inferior CSS after adjusting for confounding factors (9). In contrast, a recent meta-analysis reported a significant association between the squamous variant and CSS of UTUC patients (19). As the variant histology is rare in UTUC patients, the impacts of the various subtypes on the oncological outcomes have not been extensively investigated. We found that squamous carcinoma was the most prevalent variant, as did previous authors (19). We encountered only three cases of UTUC with sarcomatoid differentiation. The variant histology distribution within a study greatly affects the oncological outcomes. Therefore, in future, a collaborative study investigating the effects of all variant subtypes, and those of the specific subtypes, is required. Indeed, a recent study identified five distinct mutational UTUC subtypes, each with unique gene expression profiles (30), indicating that the molecular profiles differ among the variant subtypes. Thus, distinctions among the variant subtypes may explain the reported differences in the effects of adjuvant systemic therapy following radical nephroureterectomy.

Our study had certain limitations. Although this was a multicenter work, it was retrospective in nature and the follow-up duration was rather short. Notably, the current American Urological Association (AUA) (31) and European Association of Urology (EAU) (32) guidelines recommend adjuvant systemic therapy following nephroureterectomy, but only about 30% of our patients received such treatment; their courses may thus not have followed that of the contemporary clinical trajectory. Moreover, the follow-up protocols, including the types of examinations and the frequency thereof, were not fully standardized. Pathological data were obtained from the individual facilities; there was no centralized pathology review, potentially associated with some diagnostic inconsistency.

Conclusions

The variant histology was associated with reduced RFS, CSS, and OS because of the elevated pathological T stage and the presence of LVI. Thus, the most valuable insights afforded by the variant histology are available prior to radical nephroureterectomy, on examination of pretreatment biopsy samples. The variant histology does not add any predictive information to that imparted by the pathological findings after nephroureterectomy, particularly for Japanese patients with UTUC.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Textcheck Inc. for English language editing. We thank all members of the JIKEI YAYOI Collaborative Group for their constructive feedback.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Jikei University Institutional Review Board [approval No. 33-260(10878)] and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-23-561/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-23-561/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-23-561/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-23-561/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023;73:17-48. 10.3322/caac.21763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz JJ, Ellison LM. Upper tract urothelial neoplasms: incidence and survival during the last 2 decades. J Urol 2000;164:1523-5. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67019-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cha EK, Shariat SF, Kormaksson M, et al. Predicting clinical outcomes after radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol 2012;61:818-25. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margulis V, Shariat SF, Matin SF, et al. Outcomes of radical nephroureterectomy: a series from the Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Collaboration. Cancer 2009;115:1224-33. 10.1002/cncr.24135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black PC, Brown GA, Dinney CP. The impact of variant histology on the outcome of bladder cancer treated with curative intent. Urol Oncol 2009;27:3-7. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin MB. Histological variants of urothelial carcinoma: diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic implications. Mod Pathol 2009;22 Suppl 2:S96-S118. 10.1038/modpathol.2009.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakano S, Matsuyama H, Kamiryo Y, et al. Impact of variant histology on disease aggressiveness and outcome after nephroureterectomy in Japanese patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:362-8. 10.1007/s10147-014-0721-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nogueira LM, Yip W, Assel MJ, et al. Survival Impact of Variant Histology Diagnosis in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J Urol 2022;208:813-20. 10.1097/JU.0000000000002799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamboni S, Foerster B, Abufaraj M, et al. Incidence and survival outcomes in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma diagnosed with variant histology and treated with nephroureterectomy. BJU Int 2019;124:738-45. 10.1111/bju.14751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazaki J, Nishiyama H. Epidemiology of urothelial carcinoma. Int J Urol 2017;24:730-4. 10.1111/iju.13376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto K, Novara G, Gupta A, et al. Racial differences in the outcome of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: an international study. BJU Int 2011;108:E304-9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, et al. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol 2016;70:106-19. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin C, Liang EL, Du ZY, et al. Prognostic significance of urothelial carcinoma with divergent differentiation in upper urinary tract after radical nephroureterectomy without metastatic diseases: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6945. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Q, Xiong G, Li X, et al. The prognostic impact of squamous and glandular differentiation for upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients after radical nephroureterectomy. World J Urol 2016;34:871-7. 10.1007/s00345-015-1715-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JK, Moon KC, Jeong CW, et al. Variant histology as a significant predictor of survival after radical nephroureterectomy in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2017;35:458.e9-458.e15. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibing Y, Turun S, Qiang W, et al. Effect of concomitant variant histology on the prognosis of patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma after radical nephroureterectomy. Urol Oncol 2015;33:204.e9-16. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rink M, Robinson BD, Green DA, et al. Impact of histological variants on clinical outcomes of patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol 2012;188:398-404. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fradet V, Mauermann J, Kassouf W, et al. Risk factors for bladder cancer recurrence after nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial tumors: results from the Canadian Upper Tract Collaboration. Urol Oncol 2014;32:839-45. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori K, Janisch F, Parizi MK, et al. Prognostic Value of Variant Histology in Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Treated with Nephroureterectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol 2020;203:1075-84. 10.1097/JU.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami Y, Matsumoto K, Ikeda M, et al. Impact of histologic variants on the oncological outcomes of patients with upper urinary tract cancers treated with radical surgery: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Int J Clin Oncol 2019;24:1412-8. 10.1007/s10147-019-01486-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takemoto K, Hayashi T, Hsi RS, et al. Histological variants and lymphovascular invasion in upper tract urothelial carcinoma can stratify prognosis after radical nephroureterectomy. Urol Oncol 2022;40:539.e9-539.e16. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abe T, Shinohara N, Harabayashi T, et al. The role of lymph-node dissection in the treatment of upper urinary tract cancer: a multi-institutional study. BJU Int 2008;102:576-80. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda M, Matsumoto K, Hirayama T, et al. Selected High-Risk Patients With Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Treated With Radical Nephroureterectomy for Adjuvant Chemotherapy: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2018;16:e669-75. 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inamoto T, Komura K, Watsuji T, et al. Specific body mass index cut-off value in relation to survival of patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas. Int J Clin Oncol 2012;17:256-62. 10.1007/s10147-011-0284-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawashima A, Nakai Y, Nakayama M, et al. The result of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized pT3 upper urinary tract carcinoma in a multi-institutional study. World J Urol 2012;30:701-6. 10.1007/s00345-011-0775-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuroda K, Asakuma J, Horiguchi A, et al. Prognostic factors for upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma after nephroureterectomy. Urol Int 2012;88:225-31. 10.1159/000335274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makise N, Morikawa T, Kawai T, et al. Squamous differentiation and prognosis in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:7203-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shigeta K, Kikuchi E, Hagiwara M, et al. The Conditional Survival with Time of Intravesical Recurrence of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J Urol 2017;198:1278-85. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.06.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahara K, Inamoto T, Komura K, et al. Post-operative urothelial recurrence in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma managed by radical nephroureterectomy with an ipsilateral bladder cuff: Minimal prognostic impact in comparison with non-urothelial recurrence and other clinical indicators. Oncol Lett 2013;6:1015-20. 10.3892/ol.2013.1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujii Y, Sato Y, Suzuki H, et al. Molecular classification and diagnostics of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2021;39:793-809.e8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coleman JA, Clark PE, Bixler BR, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Non-Metastatic Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: AUA/SUO Guideline. J Urol 2023;209:1071-81. 10.1097/JU.0000000000003480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023. ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. Available online: http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as