Abstract

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses, which are murine picornaviruses, can cause central nervous system inflammatory disease. To study the role of loop II in capsid protein VP1, two mutant viruses of strain DA in which DA loop II amino acids were replaced with strain GDVII amino acids were constructed. Infection of mice with the two mutant viruses led to dramatically different patterns of disease.

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses (TMEV) are picornaviruses that cause neurologic and enteric infections in their natural host, the mouse. From sequence comparisons among picornaviruses, TMEV have been classified as cardioviruses (8, 10). In addition, TMEV can be divided into two major subgroups, GDVII and TO, based upon neurovirulence. The GDVII subgroup usually causes acute fatal encephalomyelitis in which infected mice die in about a week (5). If mice survive the initial infection, the GDVII virus is cleared and mice do not develop chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease (3). In contrast, the DA virus and other members of the TO subgroup produce a biphasic central nervous system (CNS) disease, and mice infected with the TO subgroup generally survive the acute phase. Viruses of this subgroup persist, and demyelination in the CNS is observed during the chronic phase of disease (2). Infection of mice with the DA virus leads to a chronic demyelinating disease similar to multiple sclerosis (reviewed in references 14 and 16).

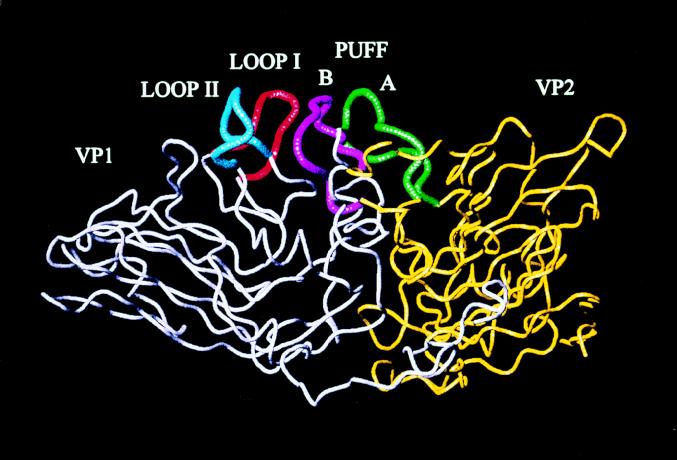

TMEV have four capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 (4, 13). VP1 is an external capsid protein and has various neutralizing epitopes defined by different monoclonal antibodies. Previous studies using two mutant viruses which differed from DA virus only at amino acid position 101 within VP1 showed altered pathogenicity, and the mutants caused similar patterns of chronic demyelinating disease with little or no virus persistence compared with wild-type DA (DAwild) virus infection (15, 17). This amino acid change occurred in the second loop (loop II), between the C and D strands of the beta barrel of VP1 (Fig. 1). Loop II is highly exposed on the surface of DA virus, whose structure has been determined by X-ray crystallography (1).

FIG. 1.

Visualization of loop II of VP1, loop I of VP1, and the puff region, including strands A B of VP2, in DA virus. VP1 is shown in grey; loop II is shown in blue.

Comparison of the regions comprising loop II between the DA and GDVII viruses found that the DA virus lacks two amino acids between positions 102 and 103 and has two different amino acids at positions 101 and 102 (1, 9, 11). This is shown in Table 1. To determine whether this loop contributes to demyelination and viral persistence, we constructed two mutant viruses from the DA virus infectious cDNA, pDAFL3 (12). The first DA mutant virus was generated to mimic GDVII virus by the addition of two additional amino acids (DA9 virus), and the other DA mutant virus has the entire loop II of GDVII virus (DA8 virus) in the background of DA virus. We found that infection of mice with the DA8 virus induced enhanced clinical symptoms, whereas the DA9 virus caused a waxing and waning inflammatory disease. The changes in loop II alone cannot account for the biological differences between the GDVII and DA viruses.

TABLE 1.

Amino acids comprising loop II in VP1

| Virus | Amino acid positiona

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 102 | 102a | 102b | 103 | 104 | 105 | |

| GDVII | S | G | G | A | N | G | A | N | F | P |

| DAwild | S | G | G | T | T | N | F | P | ||

| DA9 | S | G | G | T | T | G | A | N | F | P |

| DA8 | S | G | G | A | N | G | A | N | F | P |

The DA virus lacks two amino acids between positions 102 and 103 and has two different amino acids at positions 101 and 102. The DA9 virus was designed to have two amino acids between positions 102 and 103 of VP1 (shown in boldface type). The DA8 virus was constructed to have loop II of GDVII virus (four pertinent amino acids shown in boldface type).

Mutations were generated by in vitro site-directed mutagenesis of pDAFL3 with PCR. pDAFL3, kindly furnished by Raymond P. Roos, University of Chicago, is a full-length infectious cDNA clone of the DA virus in the transcription vector pBluescript II SK− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). pDAFL3 has been characterized previously (12). To add two amino acids between amino acids 102 and 103 of VP1 in pDAFL3, 6 nucleotides (GGAGCT) were inserted between nucleotide positions 3309 and 3310 and pDA9 was generated. To obtain loop II of the GDVII virus (pDA8), an extended overlapping PCR was performed with pDA9 as a template to change the nucleotides at two positions, 3304 and 3308. cDNAs in this region were sequenced to confirm that the correct mutations were generated.

One-step growth curves were performed with BHK-21 cells. Cells infected with DAwild, DA9, and DA8 viruses produced comparable amounts of virus, although the peak titers of DA9 virus and DA8 virus were somewhat delayed, by about 12 h. The titer of DAwild virus was slightly higher than those of the DA9 and DA8 viruses at all time points up to 24 h postinfection (p.i.). No variations in plaque phenotypes among the three viruses were observed.

Though infected mice had neuronal destruction and inflammatory infiltrates during the acute phase of the disease, mice did not have any obvious clinical signs during the acute polioencephalomyelitis phase of infection. Clinical signs were observed during the chronic phase of the disease and progressively worsened in DA8 virus- and DAwild virus-infected mice. Hind-limb paralysis and increased spasticity of the hind limbs, with a slow and ataxic gait, were common clinical features due to the involvement of the white matter (dorsal columns and the spinocerebellar and pyramidal tracts) in the spinal cord.

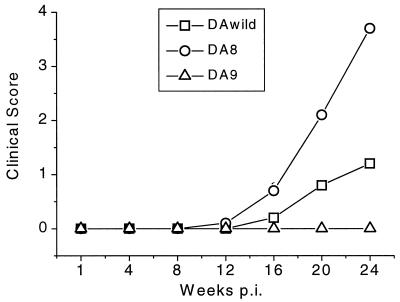

A few DAwild virus-infected mice started to show clinical signs at 16 weeks p.i. (Fig. 2). The conditions of the mice worsened, with 2 of 10 mice having mild paralysis and 1 mouse having severe spastic paralysis (average clinical score of 0.5 at 20 weeks p.i.). In contrast, DA8 virus-infected mice began developing clinical signs by 12 weeks p.i. At 20 weeks p.i., 7 of 10 mice had severe spastic paralysis, and by 24 weeks p.i., 1 mouse had died due to paralysis and 5 were moribund. DA8 virus infection of mice produced a more severe clinical disease with a shorter incubation time than did DAwild or DA9 virus (Fig. 2). DA9 virus-infected mice had no clinical symptoms during the observation period (24 weeks).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of clinical disease among DAwild, DA8, and DA9 virus-infected mice. Thirty mice (10 mice per virus group) were infected with 2 × 105 PFU of virus intracerebrally. To evaluate and quantify clinical abnormalities, mice were assessed for clinical signs with the following scale: 0, no weakness; 1, mild paralysis of one or both hind limbs; 2, moderate paralysis or ataxic gait; 3, severe paralysis; 4, total flaccid paralysis with incontinence; and 5, moribund state. The clinical scores were averaged for each group (10 mice). DA9 virus-infected mice never developed clinical symptoms during the observation period. The clinical signs in DAwild virus-infected mice began at 16 weeks p.i. In DA8 virus-infected mice, the clinical signs started at 12 weeks p.i., were more severe, and progressed rapidly.

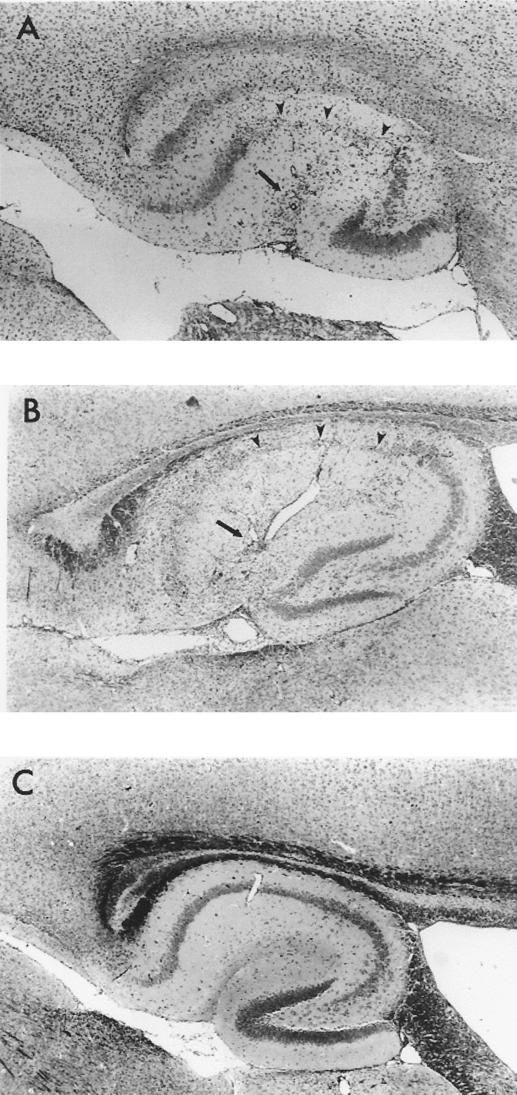

Progression of CNS disease was monitored at 1 week p.i. and thereafter. During the acute phase, infection of SJL/J mice with DAwild or DA8 virus resulted in a wide distribution of inflammatory lesions within the brain. The hippocampus, thalamus, brain stem, and spinal cord all contained inflammatory lesions. Degenerated neurons, neuronophagia, perivascular infiltrates consisting mainly of lymphocytes, and microglial proliferation comprised these lesions. Many pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were destroyed by DAwild virus and DA8 virus infection (Fig. 3A and B). DAwild virus infection had a higher pathologic score than DA8 virus at 1 week p.i. (Fig. 4). In contrast, mice infected with DA9 virus had fewer inflammatory lesions than mice infected with DAwild virus, and pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were rarely involved (Fig. 3C). From 2 to 4 weeks p.i., the pathologic score of DA8 virus infection was higher than that of DAwild virus. However, mice infected with DA9 virus had markedly fewer inflammatory lesions within the spinal cord (Fig. 4).

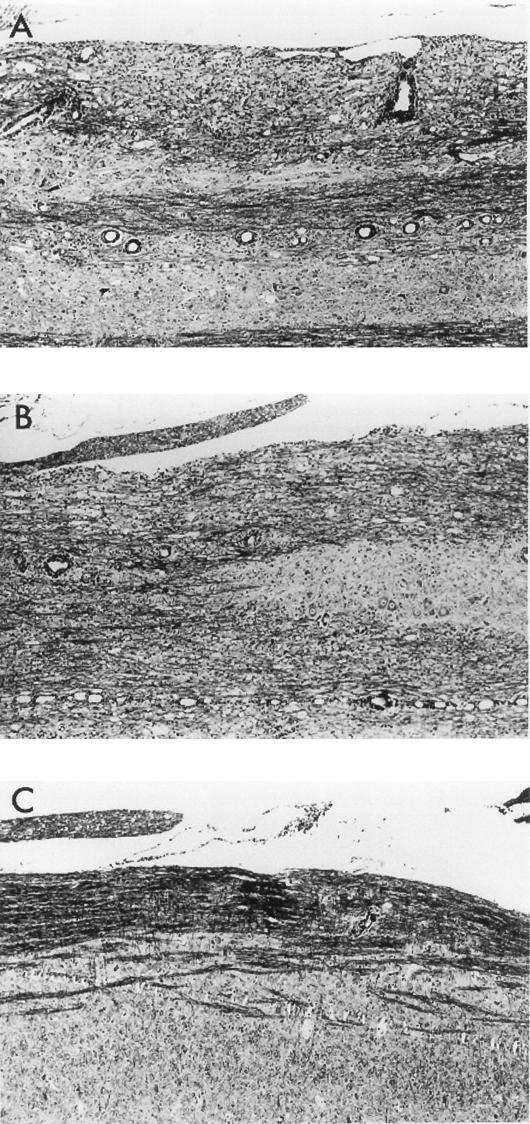

FIG. 3.

Inflammation (arrows) during DAwild virus infection (A) and DA8 virus infection (B) (2 weeks p.i.). Pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were destroyed (arrowheads). (C) No hippocampal involvement in DA9 virus infection. Neuronal structures were preserved, and rarely were infiltrates observed. (Magnification, ×100. Hematoxylin-eosin staining.)

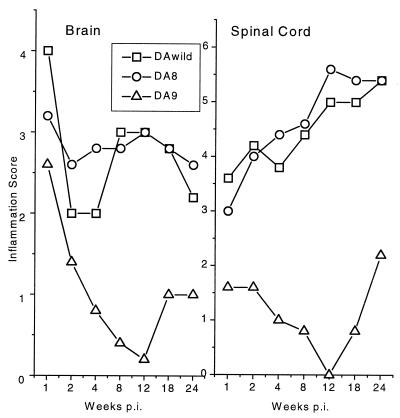

FIG. 4.

Comparison of histopathologies of DAwild, DA8, and DA9 virus infection. Tissue sections were scored for the presence of inflammatory cells and demyelination. The inflammation score measured the presence of meningitis and the extent of perivascular cuffing. For the brain, histological scoring included meningitis (0, no infiltrates; 1, few cellular infiltrates; 2, many cellular infiltrates) and the number of perivascular cuffs (0, no perivascular cuffing; 1, 1 to 15 lesions; 2, 15 to 50 lesions; 3, over 50 lesions). Scoring of the spinal cord was also based on the presence of meningitis in the cervical, thoracic, and/or lumbosacral regions of the spinal cord (0, no involved segment; 1, one involved segment; 2, two involved segments; 3, three involved segments) and the number of perivascular cuffs (0, no perivascular cuffing; 1, 1 to 15 lesions; 2, 15 to 50 lesions; 3, over 50 lesions). Demyelination was assessed with the following scale: 0, no demyelination; 1, one involved segment; 2, two involved segments; and 3, three involved segments of the spinal cord. In the brain at 1 week p.i., DAwild virus and DA8 virus infections produced more extensive inflammation than did DA9 virus infection. At 8 weeks p.i., the inflammatory response in DA9 virus infection was lower than those in DAwild and DA8 virus infection, while there was no difference between DAwild and DA8 virus infection. In the spinal cord during the observation period, DA9 virus-infected mice had less inflammation than DAwild or DA8 virus-infected mice. DAwild and DA8 virus-infected mice had similar degrees of inflammation. CNS of five mice were observed at each time point.

During the chronic phase, 4 weeks p.i. and thereafter for mice infected with DAwild or DA8 virus, many inflammatory lesions were present within the CNS white matter (Fig. 4). Numerous demyelinating lesions in the spinal cord were evident in all DAwild virus- and DA8 virus-infected mice. In contrast, at 4 to 8 weeks p.i., DA9 virus-infected mice had only a few inflammatory lesions in both the brain and spinal cord. At 12 weeks p.i., no inflammatory lesions were observed within the spinal cords of any of the five DA9 virus-infected mice (Fig. 4). Interestingly, after 18 weeks p.i., DA9 virus reappeared in the CNS (see below) and very small demyelinating areas began to appear. The infection caused by DA9 virus had a consistently lower inflammatory score than those of the DAwild and DA8 viruses during the observation period (Fig. 4).

The demyelination caused by TMEV occurred within the spinal cord during the chronic phase of infection. Demyelination started to appear at 4 weeks p.i. in the mice infected with DAwild virus and DA8 virus. From 4 to 12 weeks p.i., the score in DA8 virus-infected mice was higher than that of DAwild virus-infected mice (data not shown and Fig. 5A and B). The demyelination caused by DA9 virus infection was usually limited to small areas and was observed later, at 24 weeks p.i. (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

CNS demyelination during infection. Large demyelinating lesions with infiltrates were present in mice with DAwild virus infection (A) and DA8 virus infection (B). (C) No demyelination or infiltrates were observed in DA9 virus-infected mice. (Spinal cord, 12 weeks p.i. Magnification, ×400. Hematoxylin-eosin staining.)

To analyze the distribution and extent of infected cells in the CNS, immunohistochemistry was performed. At 1 week p.i., many neurons, including pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus, contained viral antigen in the brains of mice infected with DAwild and DA8 viruses. The numbers of viral antigen-positive cells were decreased at 2 weeks p.i. After 4 weeks p.i., the numbers of infected cells (mainly glial cells) gradually increased (Fig. 6). In contrast, at 1 week p.i., the brains of mice infected with DA9 virus contained only a few demonstrable viral antigen-positive cells, and by 2 weeks p.i., no infected cells within the brains were detected. From 4 to 8 weeks p.i., small numbers of cells (glial cells) were found to contain viral antigens. Interestingly, by 12 weeks p.i., viral antigen-containing cells were again undetectable. None of the sections from five mice contained antigen-positive cells. After 18 weeks p.i., DA9 virus reappeared (Fig. 6).

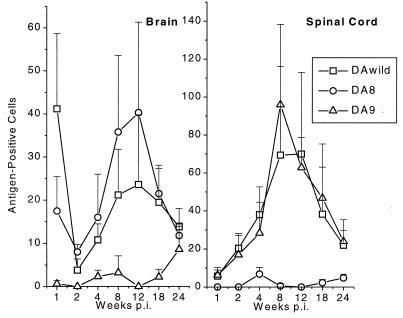

FIG. 6.

Detection of virus-infected cells in the CNS. To evaluate the distribution of virus and to quantify the number of cells containing viral antigen in the CNS, immunohistochemistry with polyclonal rabbit anti-DA virus antibody was performed. The numbers of viral antigen-positive cells were counted in the brain and spinal cord. The number of infected cells in the brain during the acute phase of infection (1 week p.i.) in DAwild virus-infected mice was larger than with DA8 virus. After 2 weeks p.i., DA8 virus-infected mice had more infected cells than did DAwild virus-infected mice. In the spinal cord, there was no difference between DAwild virus and DA8 virus, and the highest numbers of antigen-positive cells were observed at 8 weeks p.i. In contrast, DA9 virus-infected mice had only a small number of antigen-positive cells in the CNS. Five mice at each time point were studied.

In the spinal cord, DAwild virus and DA8 virus infection resulted in a gradual increase in the numbers of viral antigen-positive cells. During the chronic phase of DAwild virus infection, the predominant target site was the white matter of the spinal cord. In contrast, in the spinal cords of mice infected with DA9 virus, no viral antigen was visualized until 4 weeks p.i. At 4 and 8 weeks p.i., small numbers of viral antigen-positive cells were observed in the white matter, but by 12 weeks p.i., viral antigen-positive cells were undetectable. At 24 weeks p.i., small numbers of cells in three of five mice again contained viral antigens (Fig. 6).

To determine the amount of infectious virus in the CNS, brain and spinal cord homogenates from infected mice were tested. In the brain, the amount of infectious DAwild virus gradually decreased with time. The amount of infectious DA8 virus was similar to that of DAwild virus in infected mice (Table 2). In contrast, the amount of infectious DA9 virus in the brain was much smaller than those of DAwild and DA8 viruses, and DA9 virus was almost undetectable at 4 weeks p.i. Infectious virus could not be isolated after 12 weeks p.i.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of amounts of infectious virus isolated from the CNS of DAwild, DA9, and DA8 virus-infected mice

| Wk p.i. | Amt of virus (PFU/g of tissue)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAwild

|

DA9

|

DA8

|

||||

| Brain | Spinal cord | Brain | Spinal cord | Brain | Spinal cord | |

| 1 | 1.5 × 105 | 1.4 × 105 | 4.0 × 103 | 1.6 × 104 | 7.0 × 104 | 1.4 × 105 |

| 2 | 2.6 × 104 | 9.2 × 104 | 3.3 × 102 | 1.6 × 104 | 9.0 × 103 | 1.2 × 105 |

| 4 | 4.9 × 103 | 1.8 × 104 | 4.0 × 101 | 1.8 × 103 | 1.1 × 103 | 6.5 × 103 |

| 8 | 1.4 × 103 | 3.3 × 104 | 5.2 × 102 | 2.9 × 103 | 1.5 × 103 | 3.2 × 104 |

| 12 | 2.2 × 102 | 2.4 × 104 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 × 103 | 6.6 × 103 |

| 18 | 2.5 × 102 | 1.8 × 104 | 0 | 0 | 4.0 × 102 | 2.5 × 104 |

| 24 | 2.2 × 102 | 3.0 × 104 | 0 | 3.5 × 102 | 1.8 × 102 | 2.4 × 104 |

Values are averages from five mice at each time point.

In the spinal cord after 4 weeks p.i., the amounts of infectious DAwild and DA8 viruses were maintained at a constant level (104 PFU/g of tissue). In contrast, DA9 virus gradually declined and was undetectable at 12 and 18 weeks p.i.; however, by 24 weeks p.i., DA9 virus reappeared (in three of five mice). Virus (three independent plaques) was obtained at 24 weeks p.i., and the capsid region was sequenced. These data confirmed the mutation of the DA9 virus. Thus, the DAwild and DA8 viruses were able to persist mainly in the spinal cord; however, although the amount of DA9 virus within the CNS was substantially smaller than the amounts of the other two viruses, the DA9 virus disappeared and then reappeared (Table 2).

Loop II of VP1 is highly exposed on the surface of the virion and located on the periphery of a deep depression (Fig. 1). The depression is the likely binding site for TMEV (1, 11), mengovirus (6), and poliovirus (7). Alterations of this loop influence the virus’s ability to bind to target cells by changing the geometry of receptor entry into the depression. Two studies, by Zurbriggen et al. (17) and Wada et al. (15), demonstrate the importance of this loop. Zurbriggen et al. (17) found that a mutant virus in loop II caused the same acute disease as that of wild-type DA virus but was attenuated in inducing a chronic demyelinating disease. This suggested that loop II is important for virus-glial cell and/or macrophage interactions during the chronic phase but not during the acute phase. However, in further studies, Wada et al. (15) showed that a change in loop II created an attenuation of disease not only during the chronic phase but also during the acute phase. The attenuated disease phenotype demonstrated in this study may be due to a decreased spread by an altered attachment to neurons during the acute phase, limiting the amount of virus produced early in the CNS. Thus, from these studies, we feel that loop II of VP1 is important for virus-cell interactions during both the acute and chronic phases of DA virus infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Searles, Sheri Williams, Charles Porter, and Craig Bailey for dedication and excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Jewelyn Jenson and Kathleen Borick for preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 NS34497.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grant R A, Filman D J, Fujinami R S, Icenogle J P, Hogle J M. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler’s virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2061–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton H L. Theiler’s virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton H L. Persistent Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection in mice depends on plaque size. J Gen Virol. 1980;46:169–177. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-46-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton H L, Friedmann A. Purification of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus and analysis of the structural virion polypeptides: correlation of the polypeptide profile with virulence. J Virol. 1980;33:1165–1172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1165-1172.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorch Y, Friedmann A, Lipton H L, Kotler M. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus group includes two distinct genetic subgroups that differ pathologically and biologically. J Virol. 1981;40:560–567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.40.2.560-567.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo M, Vriend G, Kamer G, Minor I, Arnold E, Rossmann M G, Boege U, Scraba D G, Duke G M, Palmenberg A C. The atomic structure of Mengo virus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 1987;235:182–191. doi: 10.1126/science.3026048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendelsohn C L, Wimmer E, Racaniello V R. Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell. 1989;56:855–865. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nitayaphan S, Omilianowski D, Toth M M, Parks S, Rueckert R R, Palmenberg A C, Roos R P. Relationship of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus to the cardiovirus genus of picornaviruses. Intervirology. 1986;26:140–148. doi: 10.1159/000149693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pevear D C, Borkowski J, Calenoff M, Oh C K, Ostrowski B, Lipton H L. Insight into Theiler’s virus neurovirulence based on a genomic comparison of the neurovirulent GDVII and less virulent BeAn strains. Virology. 1988;165:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pevear D C, Calenoff M, Rozhon E, Lipton H L. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the picornavirus Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus indicates that it is closely related to cardioviruses. J Virol. 1987;61:1507–1516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1507-1516.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pevear D C, Luo M, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional model of the capsid proteins of 2 biologically different Theiler virus strains: clustering of amino acid differences identifies possible locations of immunogenic sites on the virion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4496–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roos R P, Stein S, Ohara Y, Fu J, Semler B L. Infectious cDNA clones of the DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1989;63:5492–5496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5492-5496.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroop W G, Baringer J R. Biochemistry of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus isolated from acutely infected mouse brain: identification of a previously unreported polypeptide. Infect Immun. 1981;32:769–777. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.769-777.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsunoda I, Fujinami R S. Two models for multiple sclerosis: experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;55:673–686. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wada Y, Pierce M L, Fujinami R S. Importance of amino acid 101 within capsid protein VP1 for modulation of Theiler’s virus-induced disease. J Virol. 1994;68:1219–1223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1219-1223.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada M, Zurbriggen A, Fujinami R S. The pathogenesis of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. Adv Virus Res. 1991;39:291–320. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60798-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zurbriggen A, Thomas C, Yamada M, Roos R P, Fujinami R S. Direct evidence of a role for amino acid 101 of VP-1 in central nervous system disease in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection. J Virol. 1991;65:1929–1937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1929-1937.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]