Abstract

The N6-methyladenosine modification is one of the most abundant post-transcriptional modifications in ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules. Using molecular dynamics simulations and alchemical free-energy calculations, we studied the structural and energetic implications of incorporating this modification in an adenine mononucleotide and an RNA hairpin structure. At the mononucleotide level, we found that the syn configuration is more favorable than the anti configuration by 2.05 ± 0.15 kcal/mol. The unfavorable effect of methylation was due to the steric overlap between the methyl group and a nitrogen atom in the purine ring. We then probed the effect of methylation in an RNA hairpin structure containing an AUCG tetraloop, which is recognized by a “reader” protein (YTHDC1) to promote transcriptional silencing of long noncoding RNAs. While methylation had no significant conformational effect on the hairpin stem, the methylated tetraloop showed enhanced conformational flexibility compared to the unmethylated tetraloop. The increased flexibility was associated with the outward flipping of two bases (A6 and U7) which formed stacking interactions with each other and with the C8 and G9 bases in the tetraloop, leading to a conformation similar to that in the RNA/reader protein complex. Therefore, methylation-induced conformational flexibility likely facilitates RNA recognition by the reader protein.

Introduction

RNA is one of the most functionally versatile chemical species with essential roles in gene expression and silencing,1−3 biochemical reactions,4,5 development of diseases,6,7 and therapeutic modalities.8−12 This broad range of functions in RNA is achieved due to its ability to undergo diverse post-transcriptional modifications which expand RNA’s conformational and functional diversity.13−18 Chemically modified RNA molecules can also adapt to thermal and environmental changes19−22 or lead to various diseases, including obesity, heart failure, and cancer.14,18,23,24 Therefore, chemical modifications in RNA may also be targeted for therapeutic intervention.23−31

RNA chemical modifications range from methylation to more complex modifications, including glycosylation, carboxylation, geranylation, isomerization, and phosphorylation.14,32,33 Among these, methylation is a commonly characterized RNA modification.14,18,34 RNA nucleotides can be methylated at distinct nitrogen atoms in nucleobases (e.g., N1, N2, N6, or N8) or on the 2′ oxygen of the ribose sugar.31 However, the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent modification in eukaryotic RNA.14 The “writer” enzymes (e.g., METTL3, METTL14) add the N6-methyl group primarily in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) and near the splicing sites in RNA.14,35 The mechanism of gene regulation by m6A was suggested to depend on reader proteins (e.g., YTHDC1) which recognize the m6A-modified nucleotides and alter the RNA structure.25,31,36,37

The m6A modification is proposed to act as a biological switch for modulating RNA activity and function.38,39 Specifically, this modification can stabilize or destabilize base pairing and stacking interactions in RNA, thereby altering RNA’s folding, stability, and function.40,41 These effects are hypothesized to further depend on the position of m6A in RNA and on the types of interactions formed between the modified base and the neighboring bases.39−42 Furthermore, the binding and dynamics of proteins selectively recognizing m6A sites in RNA could be impacted by the m6A modification via structural changes in RNA.39,41,43−45 However, a full understanding of the effects of methylation on the RNA structure, folding, and dynamics still remains elusive.14,40,46 Specifically, it is crucial to probe the diverse effects of m6A on the local and global conformational dynamics of RNA to fully resolve the structural details of recognition of methylated RNA molecules by proteins.14,41,46

Computational methods have been applied to characterize the structural effects of naturally occurring modifications in tRNA molecules.47−54 These studies have suggested that a modified base could destabilize the local base pairing interactions in which the base is directly involved, leading to the formation of new interactions which can improve the overall stability of tRNA. Additionally, quantum mechanical calculations and the nearest neighbor models were used to evaluate the effect of selective post-transcriptional modifications on the interaction energies of the modified base-pairs in RNA duplexes.55−58 The interactions between a methylated RNA mononucleotide or short methylated RNA transcripts (3–5 nucleotides-long) and a reader protein were investigated using MD simulations.59−61 These studies revealed that the hydrophobic interactions between the methyl group of the modified base and the sidechains of protein residues, coupled with the desolvation of the protein binding site, stabilized the methylated RNA nucleotide within the protein binding site.59−61 However, the RNA transcripts utilized in these studies were relatively short (3–5 nucleotides-long),59−61 lacking complete hairpin structures, thereby confounding the mechanistic details of recognition of the entire RNA hairpin by the reader protein. These limitations highlight the need to further examine the conformational effects of methylation on RNA structure and dynamics.

In this work, we applied all-atom MD simulations with alchemical free-energy calculations62−68 to probe the effects of m6A modification on the RNA structure at two distinct structural levels. Initially, we characterized the energetics of syn/anti configurations adopted by the methyl group in the methylated adenine mononucleotide, thus resolving the effects of methylation on one of the basic building blocks of RNA.69 Then, we studied an RNA hairpin capped by a methylated tetraloop motif, a commonly observed structural motif in RNA consisting of four nucleotides which serves as a recognition site for proteins.70 We observed that methylation of the tetraloop increased its flexibility, thereby revealing conformations that are accessible to the reader protein. These results highlight the significance of conformational effects in RNA originating from chemical modifications to its nucleotides.

Materials and Methods

System Setup

RNA Mononucleotide

At first, we established the conformational effects of the m6A modification on the isolated adenine RNA mononucleotide. We extracted an unpaired adenine nucleotide from the 3′-end of a single-stranded RNA structure (PDB code: 1AV6).71 We then used the Molefacture plugin in the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software72 to introduce the m6A modification in the adenine mononucleotide in both syn and anti configurations, thereby generating two distinct isomers of the m6A mononucleotide. We solvated each (syn/anti) structure of the RNA mononucleotide in a 50 Å × 50 Å × 50 Å periodic simulation domain of TIP3P water molecules73 and neutralized the overall charge of each system with one Mg2+ ion and one Cl– ion, thereby creating the solvated and ionized systems containing ∼10 000 atoms (Table S1).

RNA Hairpin

To characterize the conformational effects of methylation on the RNA structure and dynamics, we used an RNA hairpin with a methylated m6A6 nucleotide (hereafter termed A6*) as our model system. We obtained the initial coordinates for the methylated and unmethylated hairpin from the NMR structures (PDB code 7POF, methylated; PDB code 2Y95, unmethylated).46,74 We solvated each structure in a 69 Å × 68 Å × 68 Å periodic simulation domain of TIP3P water molecules73 and neutralized the overall charge of each system with seven Mg2+ ions and one Cl– ion, thereby creating the solvated and ionized systems containing ∼30 000 atoms (Table S1).

All-Atom MD Simulations

The solvated and ionized systems (RNA mononucleotide and RNA hairpin) were energy-minimized and equilibrated according to the following simulation protocol. We performed an energy minimization for 1000 steps and a brief initial equilibration for 2 ns for each RNA mononucleotide system. We subjected each RNA mononucleotide system to three 100 ns-long production MD simulations (Table S1). For the RNA hairpin, we performed an energy minimization for 4000 steps and an initial equilibration for 10 ns for each system. We subjected each RNA hairpin system to 5 independent 500 ns-long production MD simulations (Table S1). We conducted all simulations in the NPT ensemble with a 2 fs time step. The temperature and pressure were maintained at 300 K and 1 atm using the Langevin thermostat and the Nóse-Hoover barostat in all MD simulations, respectively. Periodic boundary conditions were used in all simulations, and electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald method. For van der Waals interactions, a cutoff of 16 Å with switching initiated at 15 Å was used. All simulations were conducted using the NAMD software package75 and the CHARMM36 force-field for RNA as well as for the m6A modification in RNA,76−78 the improved CHARMM36 force-field parameters for magnesium ions in the nucleic acid systems,79 and the TIP3P water model.73 All trajectories were analyzed using the VMD software.72

Alchemical Free-Energy Calculations

We calculated the relative free-energy differences by alchemically transforming the modified m6A nucleotide into an unmodified nucleotide (Figure S1). The alchemical or in silico transformation is a widely used computational method for computing thermodynamic properties by transforming a chemical species into a different one.62 The core principles of this method are rooted in Zwanzig’s mathematical formalism for relating the free-energy differences between the initial and the final state of a chemical system.80 The pathway connecting the two end states is discretized into a series of unphysical intermediate states.80 By utilizing the state-function property of the free energy, the final free-energy difference can be computed by integrating over free-energy values in each intermediate state. This technique has been successfully applied to determine the energetic contribution of individual residues in RNA/protein,65,66,68 protein/protein,81 and protein/ligand82 systems.

To compute thermodynamic changes for RNA chemical modifications, we utilized a single topology approach because the alchemical transformations in our work are focused on nucleotides sharing a common purine core (Figure S1). Thus, we defined a unique topology to describe the initial, final, as well as each intermediate state along the transformation pathway.83,84 Each state was defined in terms of a coupling parameter λ such that the initial and the final states along the transformation pathway correspond to λ = 0 and 1, respectively, and the intermediate states correspond to the intermediate values of λ.85 Accordingly, λ is used for modifying the nonbonded interaction energy terms (electrostatics and van der Waals) and the bonded terms of the potential energy function.83,86 These changes are represented by a system of linear equations in terms of λ

|

1 |

here, qi, Kb,i, rb,i, Rij, and εij correspond to the atomic charge, the bond force constant, the equilibrium distance between two atoms, and the van der Waals parameters for atomic pair {i,j}, respectively. The superscripts (0) and (1) refer to the initial and the final states, respectively.

Following Bash et al.,87,88 we performed alchemical transformations in a two-stage procedure, where calculations of the electrostatic contributions were decoupled from the calculations of the van der Waals contributions. In the first stage, the atomic charges were systematically adjusted to their final values, while the van der Waals and the bonded parameters were kept at their initial values.88 In the second stage, the van der Waals and the bonded parameters were systematically adjusted to their final values.88 The total free-energy difference between the initial and final states was determined from the sum of free-energy differences from the separate stages of the alchemical transformation.80 Thus, unique coupling parameters, λelec and λvdW, were defined for the two steps outlined above, and the resulting potential energy function for the transformation was defined as U = U(λelec, λvdW) = Uelec + UvdW. Here, Uelec and UvdW were computed using the equations below

| 2 |

furthermore, the resulting potential energy was used to compute the final free-energy differences between the states (0) and (1) using the thermodynamic integration (TI) method.83,87,89

| 3 |

here, λ represents either λelec or λvdW depending on the transformation stage, and the brackets ⟨ and ⟩ correspond to the averaging over the MD trajectory for a particular value of λ.

For the first calculation stage involving modification of the electrostatic energy terms, we used 21 equally spaced λelec windows. For the second calculation stage with changes in the van der Waals energy terms, we used 20 equally spaced λvdW windows between 0.05 and 1, followed by narrower windows at 0.0001, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04. We simulated each λ window for 1 ns while using the last 0.6 ns of each simulation for the averaging calculations. We computed the free-energy derivative ⟨∂U/∂λ⟩λ at each λ window using the finite-difference estimate and the free-energy change using the trapezoidal integration method for both the electrostatic and van der Waals stages. We estimated uncertainties in the free-energy derivatives at each λ value by splitting the trajectory segment used for averaging into two equal parts and taking the deviation of their average. To improve the accuracy of free-energy calculations, we conducted reverse simulations starting from the last saved configuration of the forward trajectory and averaging the total free-energy change over forward and reverse simulations.80 For each system, we performed five sets of forward and reverse transformations, reporting the resulting free-energy values for each system in Tables S2, S3. Furthermore, we used these free-energy values for computing the relative free-energy change (ΔΔG) for rotational isomerization of the methyl group in the m6A RNA mononucleotide. Specifically, we designed a thermodynamic cycle (Figure S2) where the horizontal arms correspond to the alchemical transformation of the m6A mononucleotide into an unmodified adenine mononucleotide, and the vertical arms correspond to the rotation of atoms around the N6 atom in the m6A and in the unmodified adenine.

Results

Energetics of syn and antim6A Isomers

We first implemented alchemical free-energy calculations to determine the structural and energetic effects of methylation in an isolated adenine RNA mononucleotide (Figures 1A, S1). Due to the presence of an additional methyl group on the N6 atom, m6A is known to exist in two distinct rotational isomers (rotamers), termed syn and anti configurations (Figure 1A).39,90 The position of the N6-methyl group in m6A is crucial for the stability of the RNA structure due to the likelihood of a steric overlap of the methyl group with the complementary Watson–Crick base.39,41,90 Using alchemical free-energy calculations, we determined that the syn configuration is favorable over the anti configuration by 2.05 ± 0.15 kcal/mol (Figure S2, Table S2). A comparison of the ΔU probability distributions characterizing the forward and reverse transformations of anti and syn rotamers showed no hysteresis, indicating convergence of free-energy estimates obtained from forward and reverse transformations (Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Two configurations of the methylated adenine (m6A) mononucleotide. (A) Structures of m6A in syn and anti configurations, (B) distances between the N7 atom (center of mass) and the methyl group (center of mass) during the alchemical transformation of the syn or anti configuration methylated adenine into an unmethylated adenine nucleotide, and (C) snapshots from an alchemical transformation simulation of anti m6A highlighting the steric overlap of the methyl group and the N7 atom (red arrow). In all panels, the methyl group in the anti configuration is highlighted in dark green color. See also Figures S4, S5.

We further evaluated the relative position of the methyl group with respect to the N7 atom (based on their centers of mass) using the alchemical pathway and conventional MD simulations (Figures 1A,B, and S4). For the anti m6A to adenine transformation, we observed that the methyl group maintained the initial anti state until λ ≈ 0.8 (Figures 1B, S4A). After that, the methyl group resembled the final state (a hydrogen atom) more than the initial state (the methyl group), making it more flexible. Thus, the transformed methyl group could overcome the steric overlap with the N7 atom and rotate into the syn isomeric state (Figures 1B,C, S5). For the syn m6A to adenine transformation, we observed that the methyl group maintained the initial syn state until λ ≈ 0.9 (Figures 1B, S4B). After that, the methyl group resembled the hydrogen atom in the final state (λ = 1) to a greater extent and was flexible enough to rotate into the anti isomeric state. In the course of the reverse simulations of the syn m6A, the methyl group rotated back into the syn state (Figure S5B). During conventional MD simulations, we observed that the methyl group maintained the initial syn or anti configurations (Figure S4).

It has been previously proposed that the less favored anti configuration of the methyl group was likely coupled with its position near the N7 atom of the purine ring, thereby creating a steric overlap between these entities.41,90 Based on our data, we find that the methyl group in the anti position indeed presents a steric overlap with the N7 atom (red arrows; Figure 1C), which further prevents the rotation of the methyl group into the syn configuration (Figure S4). A similar steric overlap between the methyl group and the N1 atom was absent in the syn rotamer (Figure S5). Thus, the methyl group experienced a higher steric overlap in the anti configuration than in the syn configuration, thereby leading to a free-energy penalty of 2.05 ± 0.15 kcal/mol (Figure S2).

Adenine Methylation Enhances Conformational Flexibility of the RNA Hairpin Tetraloop

We further studied the effect of methylation in an RNA hairpin containing a tetraloop which is one of the most abundant RNA structural motifs.70 Specifically, we focused on the AUCG tetraloop in the RNA hairpin from the X-inactive specific transcript (Xist) (Figure 2A), a long noncoding RNA responsible for inactivation of the X-chromosome in female placental mammals.46,74 The NMR structures of this hairpin with and without methylation exhibited well-defined A-form helical configurations (Figure 2B,C). These structures showed that the N6-methyl modification of A6 did not disrupt the overall RNA stem conformation, but it promoted conformational rearrangements in the tetraloop motif (Figure 2B). Specifically, the U7 nucleotide was exposed to the solvent in the methylated RNA hairpin while also inducing an additional twist in the phosphate backbone (Figure 2B). Due to this twist, the C8 and G9 nucleotides switched conformations to a largely flipped-out configuration than in the unmethylated RNA hairpin (Figure 2B,C).46,74 Despite these differences, the methylated and unmethylated tetraloops were stabilized through the formation of extended base stacking interactions between the C5, A6/A6*, and U7 nucleotides (Figure 2B,C).46,74 Therefore, it was concluded that the m6A modification introduced minor changes to the A*UCG tetraloop but did not destabilize the overall RNA hairpin structure.39,46

Figure 2.

Secondary and tertiary structures of RNA hairpin in methylated and unmethylated forms. (A) Secondary structure, (B) methylated NMR structure (PDB code: 7POF) with the methyl group highlighted in red color, and (C) unmethylated NMR structure (PDB code: 2Y95). Key nucleotides are uniquely colored and labeled.

We first assessed the conformations of the N6-methyl group in the A*UCG RNA hairpin by alchemically transforming m6A (A6*) into an adenine (A6). Based on alchemical free-energy calculations, we determined that the presence of the N6-methyl group in the A*UCG RNA hairpin was energetically less favorable than that of the unmethylated adenine by 56.54 ± 0.20 kcal/mol (Table S3). The energetically unfavorable effect of the N6-methyl group was due to the increased flexibility of the A*UCG tetraloop motif in comparison to the unmethylated tetraloop. To assess the flexibility of the tetraloop, we computed the heavy-atom RMSD values for nucleotides forming the tetraloop.

We observed that the unmethylated and methylated tetraloops deviated from their initial structures by 2.89 ± 0.25 and 4.18 ± 0.34 Å, respectively, signifying that the methylated tetraloop was more flexible than the unmethylated tetraloop (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the RMSD data for individual tetraloop nucleotides (A6, U7, C8, and G9) showed lower RMSD values in the unmethylated state, suggesting a reduced flexibility of each nucleotide (Figure 3A). The data on the change in RMSF per nucleotide (ΔRMSF) (Figure S6), where a negative ΔRMSF value indicates an increase in the flexibility of a nucleotide on methylation, showed that A6* and U7 were more flexible in methylated hairpin simulations in comparison to unmethylated hairpin simulations. Overall, these data showed that the tetraloop nucleotides were conformationally more flexible upon methylation, since these nucleotides deviated to a larger extent from their initial conformations in the methylated state than in the unmethylated state. However, the RMSD data for the RNA stem motif, defined by the nucleotides G1-C5 and G10-C14, showed that the stem motif deviated from the initial structure to the same extent with/without methylation. Therefore, methylation did not significantly affect the flexibility of the RNA stem (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

RMSD and occupancy analyses. (A) Histograms (with error bars) of mean RMSD values computed with respect to the initial structure based on MD simulations of the unmethylated (lighter shades) and methylated (darker shades) hairpin including the entire tetraloop motif (labeled TL), the individual tetraloop nucleotides (labeled A6/A6*, U7, C8, G9), and the entire stem motif (labeled stem). The experimental structures of the RNA tetraloop in (B) methylated and (C) unmethylated states, highlighting initial distances between residues involved in stacking and hydrogen-bonding interactions for which the occupancy values (shown as heat maps in panels B and C) are computed based on 5 independent MD simulations of each hairpin state. Nucleotides are uniquely colored and labeled.

To further probe interactions governing the conformation of the RNA hairpin with and without methylation, we analyzed the stacking and hydrogen-bonding interactions between several key nucleotides in the RNA tetraloop (Figure 3B,C). Specifically, we determined the initial distances between each pair of nucleotides (C5 and A6/A6*, A6/A6* and U7, A6/A6* and G10, and C5 and G10) in the methylated and unmethylated NMR structures (Figure 3B,C). These initial distances observed in the experimental NMR structures (PDBs: 7POF and 2Y95) were used as the cutoff-values for the occupancy analysis of the corresponding interactions across each of the five methylated (Figure 3B) and five unmethylated hairpin simulations (Figure 3C).

For methylated RNA hairpin simulations, we observed that the initial stacking interactions between the A6* and U7 bases were disrupted in all MD simulations, as characterized by occupancy values below 21% (Figure 3B). Additionally, the initial stacking interactions between the C5 and A6* bases were unstable, as characterized by a mean occupancy value of ∼48.4% (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the initial hydrogen-bonding interactions between the A6* and G10 bases were disrupted in all methylated hairpin simulations with occupancy values below 19% (Figure 3B). On the contrary, we observed the initial stacking interactions between C5 and A6 to be more stable in the majority of unmethylated hairpin simulations in comparison to methylated hairpin simulations, as characterized by the mean occupancy value of ∼74.6% (Figure 3C). The hydrogen-bonding interactions between A6 and G10 were also more stable in simulations without methylation (Figure 3C). Collectively, these data suggest that the initial interactions between the tetraloop nucleotides were less conserved in methylated hairpin simulations than in unmethylated hairpin simulations, further confirming the enhanced flexibility of the methylated tetraloop.

The increased flexibility of the methylated RNA tetraloop was due to the outward flipping of methylated A6. To characterize this flipping event, we calculated a base flipping angle (φ) that is defined by the centers of mass of each of the four groups of atoms (Figure S7A). This metric has been utilized previously to characterize the base flipping process in nucleic acids.91,92 For the flipped-in configuration, φ was defined between 0 and 60°, and for the flipped-out configuration, it was defined above 60° (Figure 4A). We observed the outward flipping of A6* in three independent methylated hairpin simulations (Figures 4A, S7B, and S7C). During this flipping process, A6* was initially in the flipped-in configuration, forming stacking interactions with nucleotides C5 and U7 (Figure 4B). Then, U7 flipped outward, disrupting the initial stacking interaction with A6* and forming a stacking interaction with C8 (Figure 4B). After that, the inward-flipped configuration of A6* was stabilized only by the stacking interaction with the adjacent nucleotide C5 (Figure 4B). Upon rupture of this interaction, A6* transitioned into the outward state, reforming the initial stacking interaction with U7 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Base flipping in the RNA hairpin tetraloop. (A) Traces of the base flipping angle (φ) from a representative MD simulation for each of the unmethylated (light green) and methylated A6 (dark green) states and (B) snapshots showing conformational rearrangements in methylated A6 and other neighboring tetraloop nucleotides, corresponding to various values of φ labeled with ① through ⑤ in panel A. The gray rectangle in panel A marks the angle range (0° ≤ φ ≤ 60°) for the inward flipped state. Nucleotides are uniquely colored and labeled. See also Figures S7, S8.

However, in unmethylated hairpin simulations, we observed that A6 predominantly existed in the flipped-in state (Figures 4A, S7B, and S7D). This was due to the preserved stacking interaction between A6 and U7, as observed in the initial experimental structure (Figures 3C, S8). Additionally, the stacking interaction between C5 and A6 was more preserved than a similar interaction between C5 and A6* in methylated hairpin simulations (Figures 3B, S8). Therefore, the initial stacking interactions between C5, A6, and U7 were maintained throughout the majority of MD simulations, preventing the transition of A6 into the outward state. Importantly, in one of the simulations where U7 did flip outward, A6 remained in the inward state due to continued stacking interaction with C5 (Figure S8). Furthermore, we observed A6 to flip outward in a separate unmethylated hairpin simulation, following a flipping mechanism similar to that of A6* in methylated hairpin simulations (Figure S9). After flipping outward at ∼450 ns, A6 remained in the outward state for the rest of the MD simulation. However, A6 flipped outward through the minor groove, which was distinct from the flipping of A6*, always occurring through the major groove (Figures 4B, S9). The base flipping through the minor groove was due to a conformational change in the RNA tetraloop, which led to its opening (Figure S9). Although the base flipping process is more frequently observed to proceed through the major groove in nucleic acids, it is not uncommon to observe purine nucleotides flipping via the minor groove pathway.93,94

Tetraloop Adopts Conformations Conducive to Binding of the Reader Protein

A crystal structure of the A*UCG tetraloop bound to the reader (YTHDC1) protein shows that the tetraloop is recognized by the reader protein in a single-stranded conformation (Figure S10).46 However, A6* is not in the flipped-out configuration in the unbound but methylated (A*UCG) hairpin structure (Figure 2B).46 These structures suggest that conformational transitions are necessary in A6* for it to become accessible for binding and recognition by the reader protein.46 It has been previously proposed that these conformational changes could be induced by protein binding, local unfolding of the tetraloop motif, or both of these processes.46

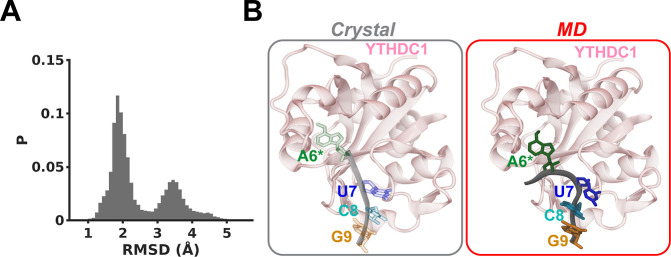

Since we observed the outward flipping of all tetraloop nucleotides in methylated hairpin simulations, we compared if the tetraloop structures with flipped-out nucleotides resembled the protein bound state. Thus, we measured the RMSD of the tetraloop nucleotides (A6*, U7, C8, and G9) with respect to the same tetraloop molecule bound to the YTHDC1 protein (Figures 5, S11). Initially, the unbound A*UCG tetraloop structure differed from the reference bound state by ∼4 Å, according to the RMSD analysis (Figure S11A). In 4 out of 5 MD simulations, we observed the RMSD values reached within 2 Å, indicating that the conformation of the tetraloop bases converged toward the protein-bound conformation (Figure S11A). Specifically, we observed that at least 3 out of 4 tetraloop bases (U7, C8, and G9) were capable of forming stacking interactions with each other, similar to the tetraloop conformation in the protein-bound state (Figure S11B). These stacking interactions in the flipped-out configuration formed irrespective of the configuration of A6* (Figure S11; flipped inward: labels 1 and 2; flipped outward: labels 3 and 4). Thus, the nucleotides U7, C8, and G9 adopted conformations similar to those observed in the RNA hairpin bound to the reader protein.

Figure 5.

(A) RMSD distribution for the tetraloop nucleotides (A6*, U7, C8, and G9), computed based on data from an MD simulation of the methylated hairpin, relative to the protein-bound conformation of the tetraloop observed in the crystal structure (PDB code: 7PO6). (B) Structural comparison of tetraloop conformations in the crystal structure (left) and from an MD simulation (right). See also Figures S11, S12.

Importantly, the rest of the hairpin structure protruded away from the protein domain without introducing any steric overlap with the protein (Figure S12). These tetraloop conformations resulted from disruption of the C5-G10 base pair, which is adjacent to the A6* nucleotide (Figure S13). The disruption of the C5-G10 base-pairing interaction was also confirmed by the occupancy analysis, which showed it to be stable only for 28% of the simulation time (label sim5; Figure 3B). Previous experimental work showed that mutating the C5 nucleotide in the C5-G10 base pair to create an unstable U5-G10 base pair improved the binding affinity of the reader protein for the mutated RNA hairpin relative to the wild-type RNA hairpin.46 Furthermore, based on the NMR data, it was proposed that the C5-G10 base pair must be open to enable recognition of the RNA tetraloop by the reader protein.46 Consistent with the previous experimental work, we observed that opening of the C5-G10 base pair resulted in a converged protein bound state. We did not observe instability in the C5-G10 base-pairing interactions in any unmethylated hairpin simulations, thereby preventing A6 from flipping outward (Figure 3C). Thus, in unmethylated hairpin simulations, A6 did not facilitate a tetraloop conformation, which can potentially serve as a binding site for the reader protein. In contrast, the methylated tetraloop revealed conformations conducive to recognition by the reader protein.

Discussion

In this work, we conducted all-atom MD simulations and alchemical free-energy calculations to probe the effect of one of the most abundant RNA modifications (m6A) on the structure and dynamics of two RNA systems: an RNA mononucleotide and an RNA hairpin. Initially, we characterized the energetic effect of the relative position of the N6-methyl group which can adopt syn or anti configurations with respect to the N1 atom in the purine ring of m6A. We alchemically transformed the methyl group to a hydrogen atom in both rotamers and estimated the resulting free-energy values. We identified that the syn configuration was energetically more favorable than the anti configuration by 2.05 ± 0.15 kcal/mol. Our free-energy results are in agreement with prior experimental work, suggesting that the syn configuration was more favorable than the anti configuration by ∼1.9 kcal/mol.90 We find that the anti configuration was less favorable due to the steric overlap between the methyl group and the N7 atom. Therefore, the methyl group in the m6A mononucleotide would preferentially adopt the syn configuration to avoid a steric clash with the purine ring. However, in an RNA duplex, the syn configuration of the methyl group may interfere with the hydrogen-bonding interactions formed between two Watson–Crick bases.39,41,90 Thus, the methyl group would be induced to transition from the syn configuration into the anti configuration by the opposing base in the Watson–Crick base pair, thereby overcoming the energetic penalty of the anti configuration.

After assessing the effect of the N6-methyl group on the RNA mononucleotide, we probed the effect of methylation on an RNA hairpin from the Xist RNA transcript. In the RNA hairpin structure, we found that the methylated adenine (A6*) was energetically less favorable (by 56.54 ± 0.20 kcal/mol) than the unmethylated adenine. This was due to the increased flexibility of the A*UCG tetraloop in comparison to that of the unmethylated AUCG tetraloop. Furthermore, the structural analyses showed that the nucleotides with a higher flexibility (A6* and U7) were located in the tetraloop motif. The increased flexibility of these nucleotides was primarily caused by the base flipping in U7 that resulted in reduced stacking interactions between A6* and U7. Due to the loss of these interactions, A6* also flipped outward, reforming stacking interactions with the U7 nucleotide. Therefore, all nucleotides in the methylated tetraloop motif were conformationally dynamic, consistent with previous experimental findings, suggesting that these nucleotides were flexible even upon protein binding.46,59,61 Importantly, the increased flexibility of the A*UCG tetraloop did not destabilize the RNA stem. This is consistent with the NMR and fluorescence data, which demonstrated that the lower RNA stem remained base-paired both in the protein-bound and -unbound states.46

We further compared the flipped-out configurations of the methylated tetraloop with the protein bound structure of the RNA hairpin. We observed MD-derived conformations of the tetraloop converging to the conformation of the tetraloop in its protein-bound state. Specifically, we observed that the methylated tetraloop with all bases in their flipped-out configurations was similar to the bound state. Importantly, this transition was coupled with an open configuration of the C5-G10 base pair, consistent with prior experimental observations suggesting that this base pair should exist in an open conformation to enable hairpin recognition by the reader protein.46 Another potentially important step in recognition of the A*UCG tetraloop by the protein could be the outward flipping of the U7 base, leading to stacking with the C8 and G9 bases. These structural rearrangements lead to a tetraloop conformation, which can potentially serve as a binding site for the reader protein and provide further access to A6*. The incorporation of methylation into the RNA hairpin tetraloop did not disrupt the overall RNA hairpin structure but still enhanced the flexibility of the nucleotides in the tetraloop. Thus, the recognition of the RNA hairpin by the reader protein might not necessarily require complete unfolding of the hairpin structure while primarily depending on the flipping of the methylated nucleotide (A6*).

Conclusions

The m6A modification is one of the most abundant modifications in RNA that is yet to be extensively explored. In this work, we combined all-atom MD simulations and alchemical free-energy calculations to study the energetic and structural effects of incorporating the N6-methyl group in an RNA mononucleotide (e.g., adenine) and in a commonly observed RNA structural motif (e.g., tetraloop). In the RNA mononucleotide, we characterized the relative position of the methyl group, which is known to exist in syn and anti configurations. We determined that the syn rotamer of the m6A mononucleotide was more favorable than the anti rotamer by 2.05 ± 0.15 kcal/mol. The free-energy penalty in the anti configuration resulted from a steric overlap between the N6-methyl group and the purine ring. We also identified that the methylated RNA hairpin was energetically less favorable than the unmethylated hairpin due to destabilization of the tetraloop structure induced by the N6-methyl group. Specifically, we observed that all nucleotides in the methylated tetraloop were conformationally more flexible than the unmethylated tetraloop nucleotides. The dynamic behavior was limited to the outward flipping of A6* and U7, thereby converging to a tetraloop conformation that can potentially serve as a binding site for the reader protein. Our approaches and findings are broadly useful for characterizing other chemical modifications and their structural effects in RNA.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R35GM138217). We also acknowledge computational support through the following resources: Premise, a central shared HPC cluster at UNH supported by the Research Computing Center; BioMade, a heterogeneous CPU/GPU cluster supported by the NSF EPSCoR award (OIA-1757371). We thank Dr. Amit Kumar (Wayne State University) for discussions related to alchemical free-energy methods.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c00522.

Summary of simulated systems, additional free-energy data from all alchemical free-energy calculations, thermodynamic cycle for estimating the relative free energy of the rotational isomerization in m6A mononucleotide, ΔRMSF data of the unmethylated and methylated RNA hairpin, base flipping angle data, and structural insights from MD simulations of the methylated/unmethylated RNA mononucleotide and RNA hairpin (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry Bvirtual special issue “Charles L. Brooks III Festschrift”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cech T. R.; Steitz J. A. The noncoding RNA revolution—trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell 2014, 157, 77–94. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M.; Breaker R. R. Gene regulation by riboswitches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 451–463. 10.1038/nrm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle J. M.; Ramakrishnan V. Structural insights into translational fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 129–177. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.061903.155440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger K.; Grabowski P. J.; Zaug A. J.; Sands J.; Gottschling D. E.; Cech T. R. Self-splicing RNA: autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of tetrahymena. Cell 1982, 31, 147–157. 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech T. R. RNA as an enzyme. Sci. Am. 1986, 255, 64–75. 10.1038/scientificamerican1186-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson H. Repeat expansion diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 147, 105–123. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall G. J.; Wickramasinghe V. O. RNA in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 22–36. 10.1038/s41568-020-00306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C. F. Therapeutic antisense oligonucleotides are coming of age. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 307–321. 10.1146/annurev-med-041217-010829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs-Disney J. L.; Yang X.; Gibaut Q. M.; Tong Y.; Batey R. T.; Disney M. D. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2022, 21, 736–762. 10.1038/s41573-022-00521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe J. A.; Wang H.; Fischmann T. O.; Balibar C. J.; Xiao L.; Galgoci A. M.; Malinverni J. C.; Mayhood T.; Villafania A.; Nahvi A.; et al. Selective small-molecule inhibition of an RNA structural element. Nature 2015, 526, 672–677. 10.1038/nature15542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disney M. D. Targeting RNA with small molecules to capture opportunities at the intersection of chemistry, biology, and medicine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6776–6790. 10.1021/jacs.8b13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T.Viral RNA targets and their small molecule ligands. RNA Therapeutics; Springer, 2017; Vol. 27, pp 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. J.; Pan T.; Kalsotra A. RNA modifications and structures cooperate to guide RNA–protein interactions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 202–210. 10.1038/nrm.2016.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzumanian V. A.; Dolgalev G. V.; Kurbatov I. Y.; Kiseleva O. I.; Poverennaya E. V. Epitranscriptome: review of top 25 most-studied RNA modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13851. 10.3390/ijms232213851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito R. J.; Myers C. A.; Chen A. A.; Vangaveti S. Challenges with simulating modified RNA: insights into role and reciprocity of experimental and computational approaches. Genes 2022, 13, 540. 10.3390/genes13030540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Li H.; Lian Z.; Deng S. The role of RNA modification in HIV-1 infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7571. 10.3390/ijms23147571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine L.; Bahena-Ceron R.; Devi Bunwaree H.; Gobry M.; Loegler V.; Romby P.; Marzi S. RNA modifications in pathogenic bacteria: impact on host adaptation and virulence. Genes 2021, 12, 1125. 10.3390/genes12081125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruehanroengra P.; Zheng Y. Y.; Zhou Y.; Huang Y.; Sheng J. RNA modifications and cancer. RNA Biol. 2020, 17, 1560–1575. 10.1080/15476286.2020.1722449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz C.; Lünse C.; Mörl M. tRNA modifications: impact on structure and thermal adaptation. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 35. 10.3390/biom7020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. N.; Jones C. I.; Graham W. D.; Agris P. F.; Spremulli L. L. A disease-causing point mutation in human mitochondrial tRNAMet results in tRNA misfolding leading to defects in translational initiation and elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 34445–34456. 10.1074/jbc.M806992200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näsvall S. J.; Chen P.; Björk G. R. The wobble hypothesis revisited: uridine-5-oxyacetic acid is critical for reading of G-ending codons. RNA 2007, 13, 2151–2164. 10.1261/rna.731007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denmon A. P.; Wang J.; Nikonowicz E. P. Conformation effects of base modification on the anticodon stem–loop of Bacillus Subtilis tRNATyr. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 412, 285–303. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri I.; Kouzarides T. Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 303–322. 10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Hu Y.; Zhou B.; Bao Y.; Li Z.; Gong C.; Yang H.; Wang S.; Xiao Y. The role of m6A modification in physiology and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 960. 10.1038/s41419-020-03143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Puig R.; Bueno-Costa A.; Esteller M. Writers, readers and erasers of RNA modifications in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 474, 127–137. 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler R.; Gillis E.; Lasman L.; Safra M.; Geula S.; Soyris C.; Nachshon A.; Tai-Schmiedel J.; Friedman N.; Le-Trilling V. T. K.; et al. m6A modification controls the innate immune response to infection by targeting type I interferons. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 173–182. 10.1038/s41590-018-0275-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson E.; Cui Y.-H.; He Y.-Y. Roles of RNA modifications in diverse cellular functions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 828683. 10.3389/fcell.2022.828683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Eckert M. A.; Harada B. T.; Liu S.-M.; Lu Z.; Yu K.; Tienda S. M.; Chryplewicz A.; Zhu A. C.; Yang Y.; et al. m6A mRNA methylation regulates AKT activity to promote the proliferation and tumorigenicity of endometrial cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1074–1083. 10.1038/s41556-018-0174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selberg S.; Zusinaite E.; Herodes K.; Seli N.; Kankuri E.; Merits A.; Karelson M. HIV replication is increased by RNA methylation METTL3/METTL14/WTAP complex activators. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 15957–15963. 10.1021/acsomega.1c01626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.; Ouyang Q.-Y.; Zhan Y.; Yin H.; Liu B.-X.; Tan L.-M.; Liu R.; Wu W.; Yin J.-Y. Pharmacoepitranscriptomic landscape revealing m6A modification could be a drug-effect biomarker for cancer treatment. Mol. Ther.--Nucleic Acids 2022, 28, 464–476. 10.1016/j.omtn.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulias K.; Greer E. L. Biological roles of adenine methylation in RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 143–160. 10.1038/s41576-022-00534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown P. J.; Ruszkowska A.; Kunkler C. N.; Breger K.; Hulewicz J. P.; Wang M. C.; Springer N. A.; Brown J. A.. Naturally occurring modified ribonucleosides; Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA, 2020; Vol. 11, p e1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontiveros R. J.; Stoute J.; Liu K. F. The chemical diversity of RNA modifications. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 1227–1245. 10.1042/BCJ20180445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Mohapatra T. Deciphering epitranscriptome: modification of mRNA bases provides a new perspective for post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 628415. 10.3389/fcell.2021.628415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D.; Saletore Y.; Zumbo P.; Elemento O.; Mason C. E.; Jaffrey S. R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W.; Adhikari S.; Dahal U.; Chen Y.-S.; Hao Y.-J.; Sun B.-F.; Sun H.-Y.; Li A.; Ping X.-L.; Lai W.-Y.; et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccara S.; Ries R. J.; Jaffrey S. R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 608–624. 10.1038/s41580-019-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G.; Fu Y.; He C. Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 108–115. 10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roost C.; Lynch S. R.; Batista P. J.; Qu K.; Chang H. Y.; Kool E. T. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2107–2115. 10.1021/ja513080v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K. I.; Parisien M.; Dai Q.; Liu N.; Diatchenko L.; Sachleben J. R.; Pan T. N6-methyladenosine modification in a long noncoding RNA hairpin predisposes its conformation to protein binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 822–833. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H.; Liu B.; Nussbaumer F.; Rangadurai A.; Kreutz C.; Al-Hashimi H. M. NMR chemical exchange measurements reveal that N6-methyladenosine slows RNA annealing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19988–19993. 10.1021/jacs.9b10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierzek E.; Kierzek R. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 4472–4480. 10.1093/nar/gkg633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Liu K.; Ahmed H.; Loppnau P.; Schapira M.; Min J. Structural basis for the discriminative recognition of N6-methyladenosine RNA by the human YT521-B homology domain family of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 24902–24913. 10.1074/jbc.M115.680389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S.; Tong L. Molecular basis for the recognition of methylated adenines in RNA by the eukaryotic YTH domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 13834–13839. 10.1073/pnas.1412742111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Wang X.; Liu K.; Roundtree I. A.; Tempel W.; Li Y.; Lu Z.; He C.; Min J. Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 927–929. 10.1038/nchembio.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. N.; Tikhaia E.; Mourão A.; Sattler M. Structural effects of m6A modification of the Xist A-repeat AUCG tetraloop and its recognition by YTHDC1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 2350–2362. 10.1093/nar/gkac080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrate N. E.; Varner M. E.; Kim K. I.; Nagan M. C. Molecular dynamics simulations of human Formula: the role of modified bases in mRNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 5361–5368. 10.1093/nar/gkl580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhar N. M.; Kumbhar B. V.; Sonawane K. D. Structural significance of hypermodified nucleic acid base hydroxywybutine (OHyW) which occur at 37th position in the anticodon loop of yeast tRNAPhe. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2012, 38, 174–185. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi R. S.; Sambhare S. B.; Sonawane K. D. MD simulation studies to investigate iso-energetic conformational behaviour of modified nucleosides m2G and m22 G present in tRNA. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2013, 5, e201302015 10.5936/csbj.201302015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Walker R. C.; Phizicky E. M.; Mathews D. H. Influence of sequence and covalent modifications on yeast tRNA dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 3473–3483. 10.1021/ct500107y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane K. D.; Sambhare S. B. The influence of hypermodified nucleosides lysidine and t6A to recognize the AUA codon instead of AUG: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Integr. Biol. 2015, 7, 1387–1395. 10.1039/C5IB00058K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandilolu P. M.; Kamble A. S.; Dound A. S.; Sonawane K. D. Role of wybutosine and Mg2+ ions in modulating the structure and function of tRNAPhe: a molecular dynamics study. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 21327–21339. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelam Prabhakar P.; Takyi N. A.; Wetmore S. D. Posttranscriptional modifications at the 37th position in the anticodon stem–loop of tRNA: structural insights from MD simulations. RNA 2021, 27, 202–220. 10.1261/rna.078097.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangaveti S.; Ranganathan S. V.; Agris P. F. Physical chemistry of a single tRNA-modified nucleoside regulates decoding of the synonymous lysine wobble codon and affects type 2 diabetes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 1168–1177. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c09053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla M.; Oliva R.; Bujnicki J. M.; Cavallo L. An atlas of RNA base pairs involving modified nucleobases with optimal geometries and accurate energies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 6714–6729. 10.1093/nar/gkv606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfinger M. C.; Kirkpatrick C. C.; Znosko B. M. Predictions and analyses of RNA nearest neighbor parameters for modified nucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8901–8913. 10.1093/nar/gkaa654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst T.; Chen S.-J. Deciphering nucleotide modification-induced structure and stability changes. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 1920–1930. 10.1080/15476286.2021.1882179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierzek E.; Zhang X.; Watson R. M.; Kennedy S. D.; Szabat M.; Kierzek R.; Mathews D. H. Secondary structure prediction for RNA sequences including N6-methyladenosine. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1271. 10.1038/s41467-022-28817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Bedi R. K.; Wiedmer L.; Huang D.; Sledz P.; Caflisch A. Flexible binding of m6A reader protein YTHDC1 to its preferred RNA motif. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 7004–7014. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Bedi R.; Wiedmer L.; Sun X.; Huang D.; Caflisch A. Atomistic and thermodynamic analysis of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) recognition by the reader domain of YTHDC1. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 1240–1249. 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c01136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepl M.; Damberger F. F.; von Schroetter C.; Theler D.; Pokorná P.; Allain F. H.-T.; Sponer J. Recognition of N6-methyladenosine by the YTHDC1 YTH domain studied by molecular dynamics and NMR spectroscopy: the role of hydration. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 7691–7705. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c03541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohorille A.; Jarzynski C.; Chipot C. Good practices in free-energy calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 10235–10253. 10.1021/jp102971x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.-C.; Lee T.-S.; Ganguly A.; Giese T. J.; Ebert M. C.; Labute P.; Merz K. M.; York D. M. AMBER free energy tools: a new framework for the design of optimized alchemical transformation pathways. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 640–658. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournia Z.; Chipot C.; Roux B.; York D. M.; Sherman W.. Free energy methods in drug discovery: current state and future directions; Armacost K. A., Thompson D. C., Eds.; ACS Publications, 2021, Chapter Introduction, pp 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Vashisth H. Conformational dynamics and energetics of viral RNA recognition by lab-evolved proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 24773–24779. 10.1039/D1CP03822B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Vashisth H. Role of mutations in differential recognition of viral RNA molecules by peptides. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 3381–3390. 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Vashisth H. Mechanism of ligand discrimination by the NMT1 riboswitch. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 4864–4874. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c00835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S.; Kumar A.; Vashisth H. Role of dynamics and mutations in interactions of a zinc finger antiviral protein with CG-rich viral RNA. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 1002–1011. 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick T.Molecular modeling and simulation: an interdisciplinary guide; Antman S. S., Marsden J. E., Sirovich L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2010; Vol. 2; Chapter Nucleic Acids Structure Minitutorial. [Google Scholar]

- Thapar R.; Denmon A. P.; Nikonowicz E. P.. Recognition modes of RNA tetraloops and tetraloop-like motifs by RNA-binding proteins; Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA, 2014; Vol. 5, pp 49–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel A. E.; Gershon P. D.; Quiocho F. A. Structural basis for sequence-nonspecific recognition of 5′-capped mRNA by a cap-modifying enzyme. Mol. Cell 1998, 1, 443–447. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandrasekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duszczyk M. M.; Wutz A.; Rybin V.; Sattler M. The Xist RNA A-repeat comprises a novel AUCG tetraloop fold and a platform for multimerization. RNA 2011, 17, 1973–1982. 10.1261/rna.2747411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. C.; Hardy D. J.; Maia J. D.; Stone J. E.; Ribeiro J. V.; Bernardi R. C.; Buch R.; Fiorin G.; Hénin J.; Jiang W.; et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. 10.1063/5.0014475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foloppe N.; MacKerell A. D. Jr All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 86–104. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denning E. J.; Priyakumar U. D.; Nilsson L.; Mackerell A. D. Jr Impact of 2′-hydroxyl sampling on the conformational properties of RNA: update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for RNA. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1929–1943. 10.1002/jcc.21777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Vanommeslaeghe K.; Aleksandrov A.; MacKerell A. D. Jr; Nilsson L.; Nilsson L. Additive CHARMM force field for naturally occurring modified ribonucleotides. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 896–912. 10.1002/jcc.24307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J.; Aksimentiev A. Improved parametrization of Li+, Na+, K+, and Mg2+ ions for all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of nucleic acid systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 45–50. 10.1021/jz201501a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chipot C.; Pohorille A.. Free energy calculations; Castleman A., Toennies J. P., Yamanouchi K., Wolfgang Z., Eds.; Springer Series in Chemical Physics; Springer Berlin: Heidelberg, 2007; Vol. 86; Chapter Calculating free energy differences using perturbation theory. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova A.; Zhang Z.; Acharya A.; Lynch D. L.; Pang Y. T.; Mou Z.; Parks J. M.; Chipot C.; Gumbart J. C. Machine learning reveals the critical interactions for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding to ACE2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 5494–5502. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.; Ramaswamy V. S.; Levy R.; Deng N. Computational design of small molecular modulators of protein–protein interactions with a novel thermodynamic cycle: allosteric inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 438–447. 10.1002/pro.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman D. A. A comparison of alternative approaches to free energy calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 1487–1493. 10.1021/j100056a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Chipot C.; Roux B. Computing relative binding affinity of ligands to receptor: an effective hybrid single-dual-topology free-energy perturbation approach in NAMD. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 3794–3802. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge D. L.; Dicapua F. M. Free energy via molecular simulation: applications to chemical and biomolecular systems. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1989, 18, 431–492. 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman D. A.; Kollman P. A. The overlooked bond-stretching contribution in free energy perturbation calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 94, 4532–4545. 10.1063/1.460608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bash P. A.; Singh U.; Langridge R.; Kollman P. A. Free energy calculations by computer simulation. Science 1987, 236, 564–568. 10.1126/science.3576184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bash P. A.; Singh U. C.; Brown F. K.; Langridge R.; Kollman P. A. Calculation of the relative change in binding free energy of a protein-inhibitor complex. Science 1987, 235, 574–576. 10.1126/science.3810157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood J. G. Statistical mechanics of fluid mixtures. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 300–313. 10.1063/1.1749657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J. D.; Von Hippel P. H. Effects of methylation on the stability of nucleic acid conformations. Monomer level. Biochemistry 1974, 13, 4143–4158. 10.1021/bi00717a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banavali N. K.; MacKerell A. D. Jr Free energy and structural pathways of base flipping in a DNA GCGC containing sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 319, 141–160. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levintov L.; Paul S.; Vashisth H. Reaction coordinate and thermodynamics of base flipping in RNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 1914–1921. 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c01199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mohan V.; Griffey R. Spontaneous base flipping in DNA and its possible role in methyltransferase binding. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 1133–1137. 10.1103/PhysRevE.62.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicy; Chakraborty D.; Wales D. J. Energy landscapes for base-flipping in a model DNA duplex. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 3012–3028. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.