Abstract

Bovine leukemia virus (BLV) and human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2) belong to the same subfamily of oncoviruses. Defective HTLV-1 proviral genomes have been found in more than half of all patients with adult T-cell leukemia examined. We have characterized the genomic structure of integrated BLV proviruses in peripheral blood lymphocytes and tumor tissue taken from animals with lymphomas at various stages. Genomic Southern hybridization with SacI, which generates two major fragments of BLV proviral DNA, yielded only bands that corresponded to a full-size provirus in all of 23 cattle at the lymphoma stage and in 7 BLV-infected but healthy cattle. Long PCR with primers located in long terminal repeats clearly demonstrated that almost the complete provirus was retained in all of 27 cattle with lymphomas and in 19 infected but healthy cattle. However, in addition to a PCR product that corresponded to a full-size provirus, a fragment shorter than that of the complete virus was produced in only one of the 27 animals with lymphomas. Moreover, when we performed conventional PCR with a variety of primers that spanned the entire BLV genome to detect even small defects, PCR products were produced that specifically covered the entire BLV genome in all of the 40 BLV-infected cattle tested. Therefore, it appears that at least one copy of the full-length BLV proviral genome was maintained in each animal throughout the course of the disease and, in addition, that either large or small deletions of proviral genomes may be very rare events in BLV-infected cattle.

Bovine leukemia virus (BLV) is associated with enzootic bovine leukosis (EBL), which is the most common neoplastic disease of cattle. Infection by BLV can remain clinically silent, with cattle in an aleukemic state, or it can emerge as a persistent lymphocytosis (PL), characterized by an increased number of B lymphocytes, and, more rarely, as B-cell lymphomas in various lymph nodes after a long latent period (4). Under experimental conditions, the same virus can easily infect sheep, which develop B-cell lymphosarcomas at higher frequencies and after a shorter latent period than cattle (1, 4).

BLV is closely related to human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2 (HTLV-1 and -2), agents associated with adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) and with the chronic neurological disorder tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (12). In addition to structural genes, BLV and HTLV have a special pX region, located between the env gene and the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR), which contains two well-characterized open reading frames (ORFs), one encoding a transactivator protein, Tax, and another encoding the Rex protein, which is involved in promoting the expression of viral structural proteins (7, 12, 37). Tax protein activates the transcription of the viral genome (6, 9, 18) and also that of many cellular genes (12). Such observations suggest that Tax promotes viral replication that results in random infection of cells and that it also promotes polyclonal proliferation of infected cells. In addition, BLV and HTLV contain several other small ORFs in the region between the env gene and the tax/rex genes of the pX region, whose products have been designated R3 and G4 in BLV (3) and p30, p13, and p12 in HTLV (5, 26). p12 of HTLV-1 seems to be weakly oncogenic (11), but the other two proteins are believed not to be essential for maintenance of the disease. Deletion of the R3 and G4 genes of BLV in an infectious and tumorigenic BLV molecular clone induced loss of the leukemogenic phenotype and, moreover, a recent report indicated that G4 exhibited oncogenic potential in vivo and in vitro (21, 44). However, the precise roles of the corresponding proteins in the pathogenesis of the viruses remain to be identified.

Transcription of the BLV or HTLV genome in fresh tumor cells or fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells from infected individuals is almost undetectable by conventional techniques (10, 22). However, in situ hybridization revealed the expression of viral RNA at low levels in many cells and at a high level in a few cells in populations of freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from clinically normal BLV-infected sheep (28) and from patients with ATL (13). Because of the low levels of expression of Tax, Rex, and products of the novel ORFs, these gene products also have not been observed directly in vivo (3, 13, 17, 24).

Many cases of ATL with defective HTLV-1 proviruses have been reported (25, 27, 33, 40). Recently, the defective viruses were classified as being of two distinct types (40). The first type retains both LTRs but lacks internal viral sequences, and the second type has a deletion of the 5′ LTR and an internal viral sequence. The defective viruses of both types lack all or part of the ORFs of the gag, pol, and env genes and exon 2 of the tax gene, which contains the initiation codon of the Tax protein, and thus, they cannot express viral proteins, such as Tax (38). Therefore, the expression of viral genes, including tax, might not be required for leukemogenesis or for maintenance of the leukemic state. In addition, the high frequency of defective viruses in the aggressive form of ATL also suggests that a correlation probably exists between clinical subtypes and the defective viruses (40, 41). Likewise, defective proviruses have been found in BLV-induced lymphoid tumors and cell lines which have been established from leukemic cells of BLV-infected hosts with lymphosarcomas (16, 23, 32). Deletions were found in 1 of 9 (11.1%) (32) and in 4 of 17 (23.5%) (23) cases of EBL, and they involved sequences located mainly in the 5′ half of the provirus as well as those in HTLV-1. However, the frequency of deletion was lower than that in HTLV-1 in patients with ATL (29 to 56%) (27, 33, 40). Transient-expression assays with cloned proviruses revealed that, in contrast to the complete provirus, truncated BLV provirus, with a deletion from the middle of the gag gene to the middle of the env gene, was unable to express viral proteins, including Tax (42). However, it is still necessary to characterize in further detail the genomic structure of the integrated provirus in BLV-infected animals and, in particular, in individuals at the asymptomatic stage.

In the present study, to investigate the structure of the BLV proviral genome in BLV-infected cattle that showed evidence of different stages of the progression of EBL, we analyzed the chromosomal DNA extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), which were obtained from 20 BLV-infected but clinically and hematologically normal cattle, and from neoplastic tissues, which were obtained from 27 BLV-infected cattle with lymphosarcomas (Table 1), by using genomic Southern hybridization and both long and conventional PCR.

TABLE 1.

Results of genomic Southern blotting and PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA from BLV-infected cattlea

| Group and animal | Age (yr) | WBCb/ mm3 | PBL/ mm3 | BLV proviral genome detection by:

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Southern analysis

|

PCRe

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

SacI digestc

|

No. of copies/ diploidd | Long

|

Conventional

|

|||||||||||||||||

| 7.9 kb | 8.2 kb | 5LTR

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

||||||||||||||

| 6.8 kb | 1.3 kb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-3 | 3 | 2 | 2-1 | 2-2 | |||||||

| Healthy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| K67 | 8 | 4,800 | 3,696 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| K69 | 8 | 9,600 | 7,680 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A40 | 11 | 8,300 | 5,561 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A46 | 11 | 5,200 | 4,680 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A51 | 10 | 9,500 | 5,605 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A54 | 14 | 4,300 | 3,483 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A60 | 9 | 3,900 | 2,847 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A63 | 14 | 5,100 | 4,182 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A69 | 9 | 17,700 | 10,089 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A78 | 8 | 2,000 | 1,520 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| S115 | 16 | 8,700 | 8,448 | + | + | Many | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| S155 | 10 | 10,900 | 6,213 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| 25Y | 10 | 10,000 | 5,600 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| A42 | 11 | 2,500 | 2,275 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NT |

| A50 | 10 | 8,000 | 6,080 | ND | ND | NT | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | NT |

| A52 | 10 | 3,400 | 3,128 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | NT |

| A43 | 11 | 3,400 | 1,802 | ND | ND | NT | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NT |

| S1 | 12 | 12,600 | 4,032 | ND | ND | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| A30 | 13 | 4,200 | 2,142 | ND | ND | NT | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | NT |

| A37 | 11 | 5,200 | 3,900 | ND | ND | NT | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | NT |

| With EBL | ||||||||||||||||||||

| pr1693 | 10 | 9,500 | 2,613 | + | + | 3 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr1698 | 8 | 19,700 | 4,334 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr1707 | 7 | 13,900 | 4,518 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr1717 | 13 | 12,100 | 5,324 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr1720 | 11 | 5,800 | 4,582 | NTg | NT | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2107 | 7 | 12,900 | 5,225 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2108 | 3 | 22,700 | 5,108 | NT | NT | NT | + (2.0)h | + (2.3)h | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2169 | 10 | 85,200 | 5,538 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2175 | 12 | 15,500 | 5,115 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2197 | 4 | 11,800 | 5,074 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2230 | 11 | 7,370 | 10,778 | + | + | 3 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2284 | 20 | 10,778 | 7,370 | NT | NT | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2374 | 8 | 36,800 | 11,040 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2436 | 7 | 28,600 | 3,432 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2493 | 1 | 74,500 | 10,430 | + | + | 2 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2501 | 4 | 28,500 | 23,085 | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2503 | 7 | 24,100 | 21,449 | + | + | 2 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2506 | 10 | 138,400 | NDf | + | + | 2 | + | + | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2507 | 3 | 164,100 | 54,974 | + | + | 1 | + | − | + | NT | NT | + | NT | + | NT | NT | NT | + | NT | NT |

| pr2119 | 3 | 6,200 | 2,263 | NT | NT | NT | + | + | + | NT | NT | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | NT |

| pr2365 | 11 | 7,100 | 2,201 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2375 | 5 | 8,700 | 4,176 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2378 | 4 | 31,000 | 12,400 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2406 | 7 | 24,100 | 14,629 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2408 | 11 | 19,800 | 8,514 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2448 | 8 | 20,700 | 7,452 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| pr2487 | 8 | 15,000 | 5,550 | + | + | 1 | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

BLV-infected cattle were classified according to previously established criteria (2, 29). Total chromosomal DNA was extracted from PBL as described by Hughes et al. (14) and from frozen blocks of tumor tissue with 10% SDS and phenol-chloroform (31).

WBC, leukocytes.

Chromosomal DNA (10 μg) was completely digested with SacI, which generates 6.8- and 1.3-kb fragments of BLV genome, and analyzed by Southern blotting with a 32P-labeled full-length BLV infectious molecular clone as a probe. +, detected; −, not detected.

Chromosomal DNA was digested with HindIII, which cleaves only once in BLV proviral DNA, and analyzed by Southern blotting as described in note c. The number of copies was estimated from the number of BLV-positive bands.

BLV genome was amplified from chromosomal DNA (100 ng to 1 μg) with various sets of primers as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis and then analyzed by Southern blotting as described in note c. +, detected; −, not detected.

ND, not determined.

NT, not tested.

Number in parentheses is length of a second fragment.

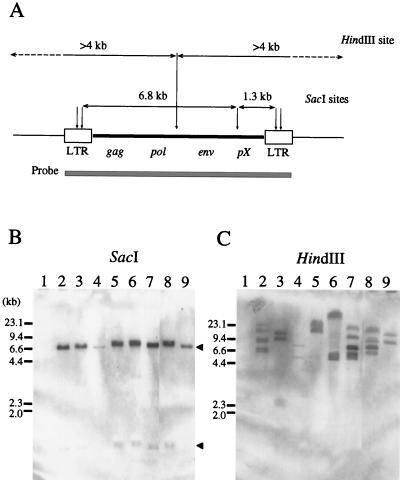

We first characterized the genomic structure of BLV provirus integrated into the host cell genome by genomic Southern hybridization. To estimate the number of copies of exogenous BLV provirus, DNA from PBL from 20 BLV-infected but healthy cattle and from tumors from 23 cattle with EBL was digested with HindIII and fragments were allowed to hybridize with 32P-labeled full-size BLV proviral DNA. As shown in Fig. 1A, HindIII cleaves the full-length BLV molecular clone λBLV-I (35) only once to generate two fragments of the viral genome per integrated copy of BLV. In the cases of 18 of 23 cattle with EBL, two BLV-positive bands were detected (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 to 6 and 9), suggesting that the 18 samples of tumor DNA represented monoclonal expansions derived from single cells that carried only one copy of the viral genome (Table 1). Three tumors (pr2493, pr2503, and pr2506) contained two copies of BLV proviral DNA, and four BLV-positive HindIII fragments were visualized, as in the case of pr2493 (Fig. 1C, lane 8). Two tumors, pr1693 and pr2230, harbored three copies of BLV (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 7), and the HindIII digests yielded six BLV-positive fragments (23.0, 17.0, 9.4, 9.0, 7.0, and 6.5 kb for pr1693 and 20.0, 10.0, 7.4, 7.3, 5.8, and 5.2 kb for pr2230). No hybridization occurred with control DNA from the BLV-free healthy animal 276 (Fig. 1C, lane 1). This analysis showed that all tumors had one to three copies of the provirus. By contrast, a smeared band of fragments from 5 to 20 kb was detected in the cases of 7 of 20 healthy cattle, indicating that the PBL from BLV-infected but healthy cattle consisted of polyclonal populations of various cells that carried multiple BLV proviruses (Table 1). Next, to determine whether the integrated BLV proviruses contained complete internal fragments, SacI-cleaved DNA from BLV-infected cattle was hybridized with 32P-labeled full-size BLV proviral DNA (Fig. 1B and Table 1). In the full-length BLV molecular clone λBLV-I, SacI cleaves at five sites in the BLV proviral DNA, generating two major fragments, one of 6.8 kb, which contains the gag, pol, and env genes and a part of the pX region, and one of 1.3 kb, which contains most of the pX region (Fig. 1A). In all of the 2 cattle with EBL that harbored three copies of provirus, the 3 EBL cattle that harbored two copies of provirus, and the 18 cattle with EBL that harbored one copy of provirus, two SacI fragments of 6.8 and 1.3 kb were detected, providing strong evidence that the integrated provirus might have been complete, regardless of the number of copies of BLV provirus in cattle at the lymphoma stage. Similar results were obtained with BLV-infected but healthy cattle. Although we detected the BLV proviral genome in only 7 of 20 healthy animals, confirming the results of genomic Southern hybridization of HindIII-cleaved DNA, in all 7 cases only two fragments of 6.8 and 1.3 kb were detected (Table 1). Thus, no defective forms of the BLV proviral genome were found in BLV-infected cattle at the asymptomatic stage, during which integration of provirus occurs at multiple sites within the host’s genome.

FIG. 1.

Genomic Southern blot analysis of BLV proviral genomes from BLV-infected cattle with EBL. (A) Structure of BLV provirus. The shaded box represents the DNA fragment used as a probe. The predicted sizes of fragments and the sites of cleavage by SacI and HindIII are also shown. SacI can generate two major fragments (6.8 and 1.3 kb), while HindIII can generate two fragments of more than 4.0 kb in length per integrated copy of the complete BLV provirus. (B and C) Ten micrograms of genomic DNA from BLV-negative animal 276 (lanes 1) and EBL tumors (lanes 2 to 9) was digested with SacI (B) and HindIII (C), subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, and then transferred to a nylon membrane. Hybridization was carried out at 42°C overnight with 2 × 106 cpm of probe per ml in 50% formamide, 5× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4), 1× Denhardt’s solution (0.02% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin, 0.02% [wt/vol] Ficoll, and 0.02% [wt/vol] polyvinylpyrrolidone), 10% dextran sulfate, 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 100 μg of heat-denatured salmon sperm DNA/ml with a 32P-labeled full-length BLV infectious clone, pBLV-IF (15), as a probe. The filters were washed twice at room temperature in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS for 20 min and then twice at 50°C with 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 min and autoradiographed. The 6.8- and 1.3-kb fragments generated by digestion of complete BLV provirus by SacI are indicated by arrowheads. The positions of the DNA molecular size markers (HindIII-digested λ DNA) are indicated. Lanes 2, pr1693; lanes 3, pr1698; lanes 4, pr1717; lanes 5, pr2169; lanes 6, pr2197; lanes 7, pr2230; lanes 8, pr2493; lanes 9, pr2501.

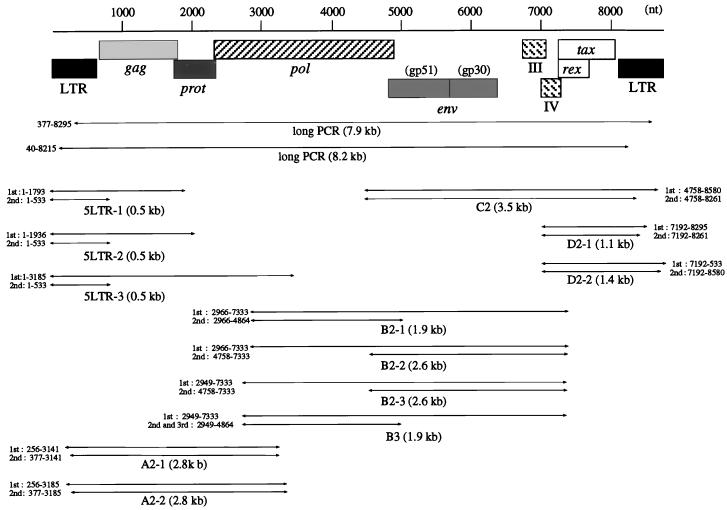

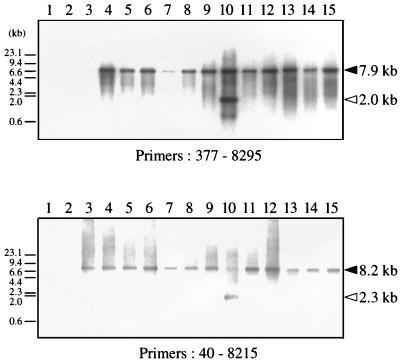

Genomic Southern analysis demonstrated that complete BLV proviral genomes were present in BLV-infected cattle throughout the course of the disease. However, we failed to detect integrated BLV viruses in 13 of 20 BLV-infected but clinically healthy cattle. Because the population of BLV-carrying circulating lymphocytes in the blood was very small, it would have been difficult to demonstrate the presence of the BLV proviral genome in these animals. Therefore, we looked for further evidence of full-size BLV provirus by long PCR, which is a more sensitive method for detecting proviral genomes than genomic Southern analysis. In 47 BLV-infected cattle, including the 13 cases in which we failed to detect integrated BLV viruses as described above, we performed long PCR with two sets of primers (Table 2 and Fig. 2): (i) 377 and 8295, which were located in the 5′ LTR R region and the 3′ LTR U3 region, respectively, amplified the 7.9-kb proviral fragment containing the U5-gag-pol-env- pX region; and (ii) 40 and 8215, which were located in the 5′ LTR U3 region and the 3′ LTR U3 region, respectively, amplified the 8.2-kb proviral fragment containing the regulatory sequences on the 5′ LTR involved in viral expression (19) in addition to all of the ORFs. The PCR products were subsequently hybridized with a full-length BLV molecular clone. Only 7.9- and 8.2-kb products corresponding to a complete copy of the provirus were found in 25 of 27 cattle with EBL, suggesting that these cattle retained the complete BLV provirus (Fig. 3, lanes 9 and 11 to 15, and Table 1). In pr2108, which we had not included in our genomic Southern analyses, we observed 2.0- and 2.3-kb fragments in addition to the 7.9- and 8.2-kb fragments, an indication that two copies of the provirus, one complete and one with a deletion of 5.9 kb, were present in this tumor (Fig. 3, lanes 10). The deletion might have been located in either the gag-pol-env region or the pol-env-pX region of the provirus. In another case, pr2507, only one (377 to 8295) of two long PCR products was amplified (Table 1). On the other hand, in 16 (including 7 cases in which we could confirm the presence of the complete provirus by genomic Southern analyses) of 20 cases of BLV-infected healthy cattle, 7.9 and 8.2 kb of the full-size proviral genome was detected (Fig. 3, lanes 3 to 8, and Table 1). In three cases, A30, A37, and A50, only one of two regions was amplified to full size (Fig. 3, lanes 2, and Table 1). In one case, A43, no BLV proviral genome was detected (Table 1). Thus, the long PCR analyses showed that at least one copy of the full-length BLV proviral genome was retained in 46 of 47 BLV-infected cattle.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification of BLV proviral genomea

| Strand | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Position in genome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | 1 | TGTATGAAAGATCATGCCGAC | 1–21 |

| 40 | CCGTAAACCAGACAGAGACGTCA | 40–62 | |

| 256 | GAGCTCTCTTGCTCCCGAGAC | 256–276 | |

| 377 | CGTCTCCACGTGGACTCTCTCCTTTGGCTCCTGACC | 377–412 | |

| 428 | AGACTAGTCTGGCTTGCACCCGCGTTTGTTTCCTG | 428–456 | |

| 2949 | GGTCCATGAGCAGATTGTCACCTACCAGTCCCTAC | 2949–2983 | |

| 2966 | TCACCTACCAGTCCCTACCTACCTTGC | 2966–2992 | |

| 4758 | AGGCGCTCTCCTGGCTACTG | 4758–4776 | |

| 7192 | GAGCTCTTCGGGATCCATTACCTG | 7192–7215 | |

| Reverse | 533 | AATTGTTTGCCGGTCTCTC | 533–515 |

| 1793 | TTGAGGGTTGGACAGTCTCG | 1793–1774 | |

| 1936 | CCAGACAGGTATACAGCCAC | 1936–1917 | |

| 3141 | TGCAGCTGTTCCGGGGAAAGC | 316–3141 | |

| 3185 | GCTTGTCGAAGCTCTGCAATGC | 3185–3164 | |

| 4864 | ATGATCGGTTGTGGGCGTCTTCGGGACCGT | 4864–4835 | |

| 7333 | GGCACCAGGCATCGATGGTG | 5619–5600 | |

| 8215 | CGGCTCCTAGGTCGGCATGATC | 8215–8194 | |

| 8261 | CGATCGCGAGCTTTTCTGGCAGCTGACGTCTCTGTC | 8261–8244 | |

| 8295 | GGTACGGGGATTCTAGCCACCAGCTGCCGTCACCAG | 8295–8260 | |

| 8580 | AGAGAGTCCACGTGGAGACGGTCAG | 8580–8556 |

Sequences and nucleotide numbers are based on data from Sagata et al. (36).

FIG. 2.

Regions of the BLV provirus amplified by PCR. Primer pairs and the lengths of products expected after PCR are also shown.

FIG. 3.

Long PCR analysis of BLV proviral genomes in BLV-infected cattle. Approximately 100 ng to 1 μg of genomic DNA from healthy cattle (lanes 2 to 8) and cattle with EBL (lanes 9 to 15) was amplified in 1× EX Taq buffer, 0.25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate 0.33 μM each oligonucleotide primer, and 1 U of EX Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo), a high-fidelity thermostable polymerase. Two sets of primers 377 and 8295 (top panel) and 40 and 8215 (bottom panel), as shown in Fig. 2, were used. Amplification was achieved by 30 or 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 8 min, followed by a 5-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel and then transferred to a nylon membrane. Southern blot hybridization was carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Products derived from full-size and defective BLV proviral genomes are indicated by solid and open arrowheads, respectively. The positions of DNA molecular size markers (HindIII-digested λ DNA) are indicated. Lanes 1, BLV-negative animal 276; lanes 2, A37; lanes 3, A46; lanes 4, A51; lanes 5, A60; lanes 6, A78; lanes 7, K67; lanes 8, K69; lanes 9, pr1698; lanes 10, pr2108; lanes 11, pr2119; lanes 12, pr2169; lanes 13, pr2374; lanes 14, pr2436; lanes 15, pr2503.

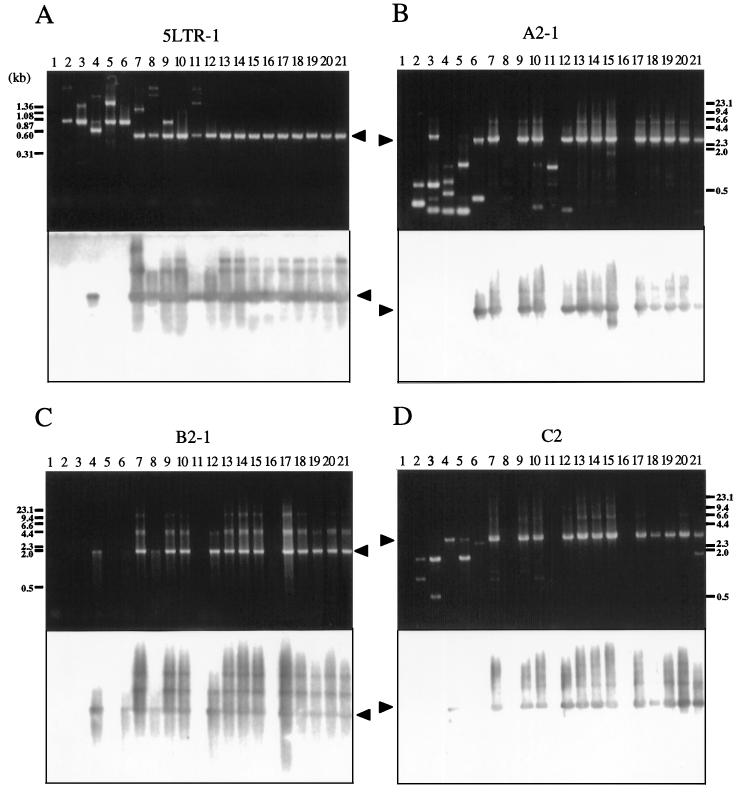

Analysis by conventional PCR can detect even small changes, such as a few hundred base pairs, that are not identifiable by genomic Southern blotting or long PCR. Therefore, we amplified DNA from 20 BLV-infected but healthy cattle and from 20 cattle with EBL by PCR with various sets of primers, as indicated in Fig. 2, and we analyzed the products by Southern blot analysis with a full-length BLV clone as the probe (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The following five regions were amplified by nested PCR with a variety of primers that spanned the BLV genome, because of the presence of variations in the sequence of BLV among BLV-infected animals: 5LTR (5LTR-1, 5LTR-2, and 5LTR-3) contained the 5′ LTR; A (A2-1 and A2-2) contained part of the 5′ LTR and the pol gene and the entire gag gene; B (B2-1, B2-2, B2-3, and B3) contained most of the pol gene; C (C2) contained the entire env gene and pX plus part of the 3′ LTR; and D (D2-1 and D2-2) contained part of pX and the 3′ LTR. Among tumors from 20 cattle with EBL, 19 gave the full-length products of PCR, 5LTR-1, A2-1, B2-1, and C2, in each of the four regions (Fig. 4, lanes 13 to 21, and Table 1). One tumor, pr2119, gave the full-length products 5LTR-1, A2-2, B2-2, B2-3, B2-4, and D2-1 but not A2-1, B2-1, and C2 (Fig. 4, lanes 16, and Table 1). Of 20 BLV-infected healthy cattle, 13 gave the full-length products 5LTR-1, A2-1, B2-1, and C2. On the other hand, in the remaining seven healthy cattle, A30, A37, A42, A43, A50, A52, and S1, at least one of the four regions was not amplified (Fig. 4, lanes 2 to 12, and Table 1). Therefore, in these seven cases, we next attempted to amplify the remaining eight regions: 5LTR-2, 5LTR-3, A2-2, B2-2, B2-3, B3, D2-1, and D2-2. Some sequences corresponding to the five main regions were specifically amplified to give full-size products covering the entire BLV genome in all seven cases (Table 1). No PCR products shorter than the expected length, which were found in some cases, were hybridized to 32P-labeled full-size BLV proviral DNA probe (Fig. 4). Thus, these results confirmed the existence of the complete BLV provirus without even a small deletion in all of 40 BLV-infected cattle tested, including a case at the asymptomatic stage, A43, in which we could not confirm the presence of the complete BLV proviral genome by genomic Southern and long PCR analyses. We also demonstrated the lack of deletion of part of the LTR in four cases, pr2507, A30, A37, and A50, in which only one of two regions was amplified by long PCR. Since data from conventional PCR showed tendencies similar to those shown by data from genomic Southern and long PCR analyses, we can conclude that no small deletions of the proviral genome had generally occurred in any cattle at the lymphoma and healthy stages.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of BLV proviral genomes in BLV-infected cattle by conventional PCR. Each panel shows an ethidium bromide-stained gel (above) and patterns of hybridization (below) of PCR products in regions 5LTR-1 (A), A2-1 (B), B2-1 (C), and C2 (D). Genomic DNA from healthy cattle (lanes 2 to 12) and from cattle with EBL (lanes 13 to 21) was amplified by nested or seminested PCR with the primers shown in Fig. 2. Amplification was achieved by 30 or 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1 to 5 min, followed by a 5-min extension at 72°C. A second or third PCR was performed for 30 cycles with 1-μl samples from the first or second amplification. PCR products were separated on 2.0% (A) or 0.8% (B to D) agarose gels and hybridized with a full-length BLV probe as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Products derived from BLV proviral genomes are indicated by arrowheads. The positions of DNA molecular size markers (HaeIII-digested φX174 DNA [A] and HindIII-digested λ DNA [B to D]) are indicated. Lanes 1, BLV-negative animal 276; lanes 2, A30; lanes 3, A37; lanes 4, A42; lanes 5, A43; lanes 6, A50; lanes 7, A51; lanes 8, A52; lanes 9, A60; lanes 10, A78; lanes 11, S1; lanes 12, K67; lanes 13, pr1698; lanes 14, pr1720; lanes 15, pr2108; lanes 16, pr2119; lanes 17, pr2169; lanes 18, pr2374; lanes 19, pr2436; lanes 20, pr2501; lanes 21, pr2506.

Genomic Southern analysis showed that tumors from BLV-infected cattle with EBL appeared to harbor one to three integrated copies of BLV in their genomic DNA, and most of these proviruses were full size, without any deletions. Likewise, DNA from PBL of some BLV-infected but healthy cattle also contained complete BLV proviruses. Further evidence for the complete viral sequences of these proviruses was provided by long PCR and conventional PCR with various primers that allowed amplification of the BLV proviral genome. Thus, BLV-infected cattle retain a complete proviral genome throughout the course of the disease. In addition to a PCR product that corresponded to a full-length copy of the provirus, a PCR product shorter than the complete virus was detected in only one animal with EBL of 47 BLV-infected cattle we studied by long PCR, strongly indicating that a large deletion of the proviral genome might be a very rare event in BLV-infected cattle. Earlier studies indicated that large deletions in the BLV provirus occurred at a frequency of from 11% (1 of 9) (32) to 23.5% (4 of 17) (23) in BLV-infected cattle with EBL. The difference in results might be related to the source of materials from BLV-infected animals. Moreover, the results of long and conventional PCRs with primers spanning to the 5′ LTR showed that these proviruses retained not only all the ORFs on the proviral genome but also all three 21-bp enhancer elements on the 5′ LTR U3 region, which are responsible for viral expression (19), and these have the features expected of a virus that expresses viral proteins. It is unclear whether complete BLV proviruses that have been integrated into the chromosomal DNA in BLV-infected cattle can be expressed and can function. However, their expression and function is supported by two observations: (i) BLV-infected animals develop a marked and persistent humoral immune response against all viral proteins (8), suggesting the continuous, albeit low-level, production of viral proteins; and (ii) transcription of the BLV genome has been demonstrated in BLV-infected cattle by sensitive techniques, such as reverse transcriptase PCR and in situ hybridization (28).

It was reported recently that 29 to 56% of patients with ATL carried HTLV-1 proviruses, with deletions that extended not only over gag, pol, and env but also to a part of the pX region that contains the tax gene. Such truncated proviruses were unable to encode viral proteins (27, 33, 40). Perhaps cells infected with a defective virus can escape cytotoxic T lymphocytes, with a consequently greater likelihood of leukemic changes. By contrast, we found that the complete BLV provirus, with the features expected for a genome that can generate viral particles, was present in nearly all of the BLV-infected cattle examined. According to a previous study, when the complete proviruses were cloned from fresh tumors in which no transcription of viral sequences was evident and were used to transfect mammalian cell lines, the proviruses retained the ability to express the structural proteins (42). Furthermore, full-length molecular clones of BLV have been shown to be capable of establishing infection and inducing disease when inoculated into sheep in vivo (34, 43). However, little or no transcript of BLV has been detected in BLV-infected cattle (17, 22, 29). It is unknown why proviruses are expressed in vivo at levels too low to be detected by conventional methods. Two major conclusions can be reached from the earlier findings and our results. First, a very low level of expression of a BLV provirus in vivo does not necessarily imply any dynamic structural alterations in viral information, such as a large deletion in the proviral genome. Rather, expression is likely to be blocked at the transcriptional level. Recent findings (20) showed that expression of BLV was not correlated with the activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and was even inhibited by cyclic AMP, although it was correlated with the activation of protein kinase C (PKC) ex vivo, suggesting that some signal transduction pathways in the host cell might regulate the expression of BLV provirus. Second, it is probable that there are differences between HTLV-1 and BLV in the role of the proviral genome in leukemogenesis, in the molecular mechanisms that control proviral expression, and in strategies for evading the host’s immunosurveillance system.

Several primers used in this study allowed us to amplify proviral genomes from some BLV-infected animals but not others. One possible interpretation of these results is the presence of sequence variations among BLV-infected animals. The nucleotide sequences of the env genes of seven isolates of BLV demonstrated that the few nucleotide substitutions represented about 6% of the sequence (30). We have also found several BLV variants or amino acid substitutions in gag and tax gene products in the same BLV-infected animals that we examined in this study (39), although the incidence of missense mutations was much lower than that in human immunodeficiency virus, which has a high rate of sequence variation. Such variations in BLV sequences might be a strategy, adopted by complete proviruses without large deletions, that allows them to persist under immunological attack by the host’s immune response.

We have demonstrated clearly here that BLV-infected cattle retained a full-length proviral genome throughout the course of the disease, in sharp contrast to the high frequencies of deletions in proviruses in HTLV-1-induced tumors. However, the biological properties and transforming potentials of these complete BLV proviruses still remain to be characterized. It was originally proposed that both HTLV-1 and BLV might potentially express, in addition to the Tax and Rex ORFs, several other small ORFs in the pX region (i.e., those encoding R3 and G4 for BLV and p30, p13 and p12 for HTLV). Alexandersen et al. (3) reported that alternatively spliced mRNAs that encoded R3 and G4 were specifically detected in cattle with PL and that these gene products might be responsible for the development of PL. Recently, a Belgian group (21, 44) showed that the ORFs encoding G3 and G4 were required for maintenance of high virus loads during the course of persistent infection in vivo and that G4 exhibited oncogenic potential in vivo and in vitro, suggesting that these viral proteins might be important for leukemogenesis. Therefore, since the complete BLV proviruses had the features expected of a virus that expresses viral proteins, such as Tax, Rex, and the newly identified proteins, transcription of these proviral genes must now be analyzed in the cattle used in this study. Moreover, it is now essential to define the roles of the complete BLV provirus in the induction and development of leukemogenesis and in the maintenance of the tumorous state.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kousuke Okada for providing tumors and peripheral blood from BLV-infected cattle.

This work was supported by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting of Science and Technology of the Science and Technology Agency of the Japanese Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida Y, Miyasaka M, Okada K, Onuma M, Kogure S, Suzuki M, Minoprio P, Levy D, Ikawa Y. Further phenotypic characterization of target cells for bovine leukemia virus experimental infection in sheep. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aida Y, Okada K, Ohtsuka M, Amanuma H. Tumor-associated Mr 34,000 and Mr 32,000 membrane glycoproteins that are serine phosphorylated specifically in bovine leukemia virus-induced lymphosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6463–6470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandersen S, Carpenter S, Christensen J, Storgaard T, Viuff B, Wannemuehler Y, Belousov J, Roth J A. Identification of alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding potential new regulatory proteins in cattle infected with bovine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1993;67:39–52. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.39-52.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burny A, Bruck C, Cleuter Y, Couez D, Deschamps J, Ghysdael J, Gregoire D, Kettmann R, Mammerickx M, Marbaix G, Portetelle D. Bovine leukemia virus: a new mode of leukemogenesis. In: Klein G, editor. Advances in viral oncology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1985. pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciminale V, Pavlakis G, Derse D, Cunningham C, Felber B. Complex splicing in the human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV) family retrovirus: novel mRNAs and proteins produced by HTLV type I. J Virol. 1992;66:1737–1745. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1737-1745.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derse D. Bovine leukemia virus transcription is controlled by a virus-encoded trans-acting factor and by cis-acting response elements. J Virol. 1987;61:2462–2471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2462-2471.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derse D. trans-Acting regulation of bovine leukemia virus mRNA processing. J Virol. 1988;62:1115–1119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1115-1119.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshayes L, Levy D, Parodi A L, Levy J. Spontaneous immune response of bovine leukemia-virus-infected cattle against five different viral proteins. Int J Cancer. 1980;25:503–508. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910250412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felber B K, Paskalis H, Kleinman-Ewing C, Wong-Staal F, Pavlakis G N. The pX protein of HTLV-1 is a transcriptional activator of its long terminal repeats. Science. 1985;229:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.2992082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchini G, Wong-Staal F, Gallo R C. Human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-1) transcripts in fresh and cultured cells of patients with adult T-cell leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6207–6211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini G, Mulloy J C, Koralnik I J, Lo Monico A, Sparkowski J J, Andresson T, Goldstein D J, Schlegel R. The human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I p12I protein cooperates with the E5 oncoprotein of bovine papillomavirus in cell transformation and binds the 16-kilodalton subunit of the vacuolar H+ ATPase. J Virol. 1993;67:7701–7704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7701-7704.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franchini G. Molecular mechanisms of human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I infection. Blood. 1995;86:3619–3639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa Y, Osame M, Kubota R, Tara M, Yoshida M. Human T-cell leukemia virus type-1 (HTLV-1) Tax is expressed at the same level in infected cells of HTLV-1-associated myelopathy or tropical spastic paraparesis patients as in asymptomatic carriers but at a lower level in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Blood. 1995;85:1865–1870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes S H, Shank P R, Spector D H, Kung H-J, Bishop J M, Vermus H E, Vogt P K, Breitman M L. Proviruses of avian sarcoma virus are terminally redundant, co-extensive with unintegrated linear DNA and integrated at many sites. Cell. 1978;15:1397–1410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inabe K, Ikuta K, Aida Y. Transmission and propagation in cell culture of virus produced by cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone of bovine leukemia virus. Virology. 1998;245:53–64. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itohara S, Sekikawa K, Mizuno Y, Kono Y, Nakajima H. Establishment of bovine leukemia virus-producing and nonproducing B-lymphoid cell lines and their proviral genomes. Leuk Res. 1987;11:407–414. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(87)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen W A, Rovnak J, Cockerell G L. In vivo transcription of the bovine leukemia virus tax/rex region in normal and neoplastic lymphocytes of cattle and sheep. J Virol. 1991;65:2484–2490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2484-2490.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katoh I, Sagata N, Yoshinaka Y, Ikawa Y. The bovine leukemia virus X region encodes a trans-activator of its long terminal repeat. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1987;78:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoh I, Yoshinaka Y, Ikawa Y. Bovine leukemia virus trans-activator p38tax activates heterologous promoters with a common sequence known as a cAMP responsive element or the binding site of a cellular transcription factor ATF. EMBO J. 1989;8:497–503. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerkhofs P, Adam E, Droogmans L, Portetelle D, Mammerickx M, Burny A, Kettmann R, Willems L. Cellular pathways involved in the ex vivo expression of bovine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1996;70:2170–2177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2170-2177.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerkhofs P, Heremans H, Burny A, Kettmann R, Willems L. In vitro and in vivo oncogenic potential of bovine leukemia virus G4 protein. J Virol. 1998;72:2554–2559. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2554-2559.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kettmann R, Cleuter Y, Mammerickx M, Meunier-Retival M, Bernadi G, Chantrenne H. Genomic integration of bovine leukemia provirus: comparison of persistent lymphocytosis with lymph node tumor form of enzootic bovine leukosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2577–2581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kettmann R, Deschamps J, Cleuter Y, Couez D, Burny A, Marbaix G. Leukemogenesis by bovine leukemia virus: proviral DNA integration and lack of RNA expression of viral long terminal repeat and 3′ proximate cellular sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2465–2469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinoshita T, Shimoyama M, Tobinai K, Ito M, Ito S, Ikeda S, Tajima K, Shimotono K, Sugimura T. Detection of mRNA for the tax1/rex1 gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type I in fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells of adult T-cell leukemia patients and viral carriers by using the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5620–5624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konishi H, Kobayashi N, Hatanaka M. Defective human T-cell leukemia virus in adult T-cell leukemia patients. Mol Biol Med. 1984;2:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koralnik I J, Gessain A, Klotman M E, Monico A L, Berneman Z N, Franchini G. Protein isoforms encoded by the pX region of human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8813–8817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korber B, Okayama A, Donnelly R, Tachibana N, Essex M. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of defective human T-cell leukemia virus type I proviral genomes in leukemic cells of patients with adult T-cell leukemia. J Virol. 1991;65:5471–5476. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5471-5476.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagarias D M, Radke K. Transcriptional activation of bovine leukemia virus in blood cells from experimentally infected, asymptomatic sheep with latent infections. J Virol. 1989;63:2099–2107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2099-2107.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy D, Deshayes L, Guillemain B, Parodi A-L. Bovine leukemia virus specific antibodies among French cattle. 1. Comparison of complement fixation and hematological tests. Int J Cancer. 1977;19:822–827. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910190613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamoun R Z, Morisson M, Rebeyrotte N, Busetta B, Couez D, Kettmann R, Hospital M, Guillemain B. Sequence variability of bovine leukemia virus env gene and its relevance to the structure and antigenicity of the glycoproteins. J Virol. 1990;64:4180–4188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4180-4188.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKnight G S. The induction of ovalbumin and conalbumin mRNA by estrogen and progesterone in chick oviduct explant cultures. Cell. 1978;14:403–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa Y, Sagata N, Tsuzuku-Kawamura J, Koyama H, Onuma M, Izawa H, Ikawa Y. Structure of a defective provirus of bovine leukemia virus. Microbiol Immunol. 1987;31:1009–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1987.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohshima K, Kikuchi M, Masuda Y-I, Kobari S, Sumiyoshi Y, Eguchi F, Mohtai H, Yoshida T, Takeshita M, Kimura N. Defective provirus form of human T-cell leukemia virus type I in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma: clinicopathological features. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4639–4642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rovnak J, Boyd A L, Casey J W, Gonda M A, Jensen W A, Cockerell G L. Pathogenicity of molecularly cloned bovine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1993;67:7096–7105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7096-7105.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagata N, Ogawa Y, Kawamura J, Onuma M, Izawa H, Ikawa Y. Molecular cloning of bovine leukemia virus DNA integrated into the bovine tumor cell genome. Gene. 1983;26:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sagata N, Yasunaga T, Tsuzuku-Kawamura J, Ohishi K, Ogawa Y, Ikawa Y. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of bovine leukemia virus: its evolutionary relationship to other retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:677–681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sagata, N., J. Tsuzuku-Kawamura, M. Nagayoshi, F. Shimizu, K. Imagawa, and Y. Ikawa. Identification and some biochemical properties of the major Xbl product of bovine leukemia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:7879–7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sakurai H, Kondo N, Ishiguro N, Mikuni C, Ikeda H, Wakisaka A, Yoshiki T. Molecular analysis of a HTLV-1 pX defective human adult T-cell leukemia. Leuk Res. 1992;16:941–946. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90040-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tajima, S., and Y. Aida. Unpublished data.

- 40.Tamiya S, Matsuoka M, Etoh K-I, Watanabe T, Kamihara S, Yamaguchi K, Takatsuki K. Two types of defective human T-lymphotropic virus type I provirus in adult T-cell leukemia. Blood. 1996;88:3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsukasaki T, Tsushima H, Yamamura M, Hata T, Murata K, Maeda T, Atogami S, Sohda H, Momita S, Ideda S, Katamine S, Yamada Y, Kamihira S, Tomonaga M. Integration patterns of HTLV-1 provirus in relation to the clinical course of ATL: frequent clonal change at crisis from indolent disease. Blood. 1997;89:948–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Den Broeke A, Cleuter Y, Chen G, Portetelle D, Mammerickx M, Zagury D, Fouchard M, Coulombel L, Kettmann R, Burny A. Even transcriptionally competent proviruses are silent in bovine leukemia virus-induced sheep tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9263–9267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willems L, Portetelle D, Kerkhofs P, Chen G, Burny A, Mammerickx M, Kettmann R. In vivo transfection of bovine leukemia virus into sheep. Virology. 1992;189:775–777. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90604-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willems L, Kerkhofs P, Dequiedt F, Portetelle D, Mammerickx M, Burny A, Kettmann R. Attenuation of bovine leukemia virus by deletion of R3 and G4 open reading frames. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11532–11536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]