Abstract

Objective:

Suicide is a major public health concern among military servicemembers, and previous research has demonstrated an association between bullying and suicide. This study evaluated the association between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation via perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness which were hypothesized to mediate this association.

Method:

471 suicidal Army Soldiers and US Marines completed self-report measures of suicidal ideation, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and bullying. A series of regressions were used to test the hypothesized mediation model using the baseline data from a larger clinical trial.

Results:

Perceived burdensomeness was a significant mediator of the association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation, but thwarted belongingness was not a significant mediator.

Conclusions:

Perceived burdensomeness may represent a malleable target for intervention to prevent suicide among military servicemembers, and should be evaluated further as an intervening variable with regard to suicidality in the setting of bullying victimization.

Keywords: Military, suicide, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, bullying, Army, Marines

Suicide in the Military

In 2008, for the first time in recorded history, the suicide rate in active duty military servicemembers who were male overtook the rate for comparable males in civilian samples (Nock et al., 2013). Suicide is now the second leading cause of death across the US Armed Forces, and represents the most frequent traumatic death during armed forces training (Scoville, Gardner, Magill, Potter, & Kark, 2004). Given that military servicemembers are screened for serious mental illness by means of a general psychiatric evaluation prior to enlistment (Cardona & Ritchie, 2007), this already disconcerting statistic takes on a new tone. A population that is theoretically healthy, mostly young, and mostly male often does not make use of services and structures in place to deal with the challenges of military service (Sharp et al., 2015) or their needs are not met by existent mental health care in the military (Waitzkin et al., 2018). Indeed, there is a distinct under-utilization of mental health services in the military: up to 60% of military servicemembers with a mental health problem do not seek help (Sharp et al., 2015), a problem that may further complicate military suicide prevention efforts. This under-utilization of service is often due to barriers such as stigma and inadequate facilitation of care (Hom, Stanley, Schneider, & Joiner, 2017). However, under-utilization does not wholly explain the problem of military suicide; according to the Department of Defense Sentinel Event Report, 44% of soldiers in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq who attempted suicide had received behavioral health care in the month prior to their attempt, as well as 22% of soldiers who died by suicide (Archuleta et al., 2014). Thus, the care provided to suicidal military personnel may not be sufficient, nor does it have a wide enough reach to afford care to everyone who needs it.

Hazing and Bullying in the Military

Despite condemnation from the Department of Defense, hazing remains a longstanding practice in many military units (Keller et al., 2015). According to the Department of Defense’s Hazing Report to Congress, from April 26, 2016 to September 30, 2017, there were 415 hazing complaints, involving 824 alleged offenders and 733 complainants across all military branches (Department of Defense, 2017). As most bullying and hazing is not reported, this is likely as substantial underestimate. In response to the prevalence of hazing, the Department of Defense has made tangible changes, and cite hazing as being fundamentally in opposition to their values (DiRosa & Goodwin, 2014).

There is no federally accepted definition of hazing, though Florida’s law, colloquially regarded as one of the best state hazing laws, defines hazing as “any action or situation that recklessly or intentionally endangers the mental or physical health or safety of a person for purposes including, but not limited to, initiation or admission into or affiliation with any organization operating under the sanction of a postsecondary institution”, (Hernandez, 2015). Keller and colleagues (2015) note that hazing is justified within the military by its purported ability to create a group bond. This bonding phenomenon, however, is not empirically supported, and in fact, hazing has been associated with lower levels of group liking (Keller et al., 2015).

Bullying, meanwhile, is generally defined as repeated exposure to negative actions from one or more people, wherein there is an imbalance of power between the victim and the perpetrator(s) (Moore et al., 2017). The line between hazing and bullying is not easily distinguished among military personnel: authors of a 2001 study of the Norwegian Army were unable to distinguish the distinction between hazing and bullying (Østvik and Rudmin, 2001), arguing that it’s easy for bullying and hazing to be confounded given that bullying can be rationalized as hazing, the actions of hazing and bullying can be identical, and that making that distinction requires information such as the contexts and cognitions of bullying, which are not always evident in a particular action. Given the prevalence of hazing in the military and the ambiguous distinction between hazing and bullying, it is reasonable to assume that there is a significant amount of bullying in the military, a phenomenon that is entrenched within the structure of the military itself.

The Psychological Effects of Bullying

The psychological effects of bullying are well-documented. There are a host of negative psychological consequences to bullying, including the development of anxiety disorders, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, decline or problems in physical health, and even have shown poorer economic futures (Wolke & Lereya, 2015). One meta-analysis reported that 57% of bullying victims report symptoms of PTSD above cut-off thresholds (Nielsen, Nielsen, Notelaers, & Einarsen, 2015). This result is especially concerning given that Brake and colleagues (2017) suggest the link between PTSD and suicide risk, which appear to be highly related but are not yet causally linked. Opperman and colleagues (2015) conducted a study with adolescents who were experiencing interpersonal problems such as bully victimization, bully perpetration, and/or low interpersonal connectedness. They found the interaction of a high sense of perceived burdensomeness and low family connectedness (their construct for thwarted belongingness) predicted more severe suicidal ideation.

Nielsen and colleagues (2015) found that victimization from bullying was associated with later suicidal ideation. Childhood bullying is similarly intransient: Tazikawa, Maughan, and Arseneault (2014) note that children, especially those who are frequently bullied, are at risk of a host of adverse health, social, and economic outcomes for four decades following exposure; as such, Tazikawa and colleagues (2014) note that interventions need to focus on the reduction of bullying itself if real change is to be expected.

Further, there is evidence suggesting several types of bullying may have more detrimental effects on mental health than others. While no study has directly compared different types of bullying and their effects on mental health, several studies have investigated the mental health outcomes of different types of bullying. For instance, Goodenow and colleagues (2016) found persistent disparities in bullying and school-related violence between LGB individuals and their heterosexual peers. Russell and colleagues (2012) found that those living with devalued social identities (such as youth who are LGBTQ, overweight and obese, or are of a minority racial group) were more likely to experience frequent bullying by their peers. Thus, it is important to investigate if the “causes” of bullying have differential psychological impact.

Workplace Bullying

Workplace bullying has been positively related to workload, organizational constraints, bad and stressful work situations, while being negatively linked to workplace cohesion, social support, communication and trust, sense of community at work, and job control (Trepanier, Fernet, Austin, & Boudrias, 2016). There is a dearth of research on workplace bullying and suicide, though a few papers have addressed the topic. Milner and colleagues (2016) found that those who experienced suicidal ideation were more likely to have been exposed to workplace bullying or harassment and that low job control as well as high job insecurity were predictive of suicidal ideation. They interpreted their results in line with the interpersonal theory of suicide, suggesting that people who experience workplace bullying may perceive themselves to be socially alienated, and that their experiences of bullying are painful and provocative and thus qualify as events that will eventually lead to acquired capacity to overcome self-preservation instincts.

Similar to adolescent bullying, bullying in the workplace has a host of psychological consequences including disengagement from the workplace (analogous to thwarted belongingness) and the undermining of the well-being of employees via ineffective coping (Trepanier, Fernet, Austin, & Boudrias, 2016). There is empirical evidence that suggests that while there are tenable differences between adult and childhood bullying, they are strongly interrelated and are similar enough to be studied together (Nielsen, Nielsen, Notelaers, & Einarsen, 2015).

Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal theory of suicide offers a potential explanation to the behavior of suicide. It suggests that acute suicidal desire occurs when an individual both perceives themselves as burden on others (perceived burdensomeness), viewing themselves as unable to contribute to their family and to society, and experiences thwarted belongingness, which demonstrates itself in feelings of loneliness and disconnection from others. In addition, these feelings are perceived to be stable and unchanging (Silva et al., 2017). Completed suicides and near lethal suicide attempts emerge when suicidal desire intersects with the capability for suicide (AC), which is the ability to enact lethal self-harm that occurs due to physical and psychological provocation that unfolds over time, and leads to fearlessness of death (Joiner, 2005).

The Current Study

Though bullying and the interpersonal theory have both been investigated in the military, little research links the two and their impact on suicidality. It is reasonable to expect that bullying in the military is associated with suicidal ideation in a population that is well-equipped to enact suicide, thereby creating a serious risk to soldiers. Therefore, this study evaluated the connection of bullying and level of suicidal ideation, as well as the intervening role of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, in a large sample of suicidal military personnel. We hypothesized that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would mediate a positive association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation. We thought this phenomenon especially important to investigate in a military context, where desertion can be punishable with enormous consequences; this can potentially create an environment of entrapment, wherein soldiers feel as if they’re a burden, that they don’t belong, and that they can’t escape. This is especially troubling given that Teismann and Forkmann (2017) found that perceptions of entrapment mediated the relationship between rumination and suicidal ideation, an effect independent of depression, anxiety, and distress.

This study examined the indirect effect of workplace bullying upon level of suicidal ideation via perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. It was hypothesized that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would mediate the positive association of workplace bullying and level of suicidal ideation adjusting for socio-demographic confounders and childhood history of bullying.

Methods

Participants

This study utilized baseline data collected prior to randomization from a larger treatment effectiveness trial, known as the Military Continuity Project (MCP; Comtois et al., 2019) with the following inclusion criteria: 1) Active duty, Reserve, National Guard, 2) 18 or more years of age, 3) English speaking, 4) identification to a behavioral health or medical service (inpatient, outpatient, or emergency) due to suicidal behavior - either suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, 5) has current suicidal ideation as defined by a score of 1 or more on the Scale for Suicide Ideation, and 6) mobile phone or pager that can affordably receive 11 text messages in a year. Exclusion criteria were 1) too cognitively impaired at best mental status to consent, 2) treating clinician evaluates the intervention as contra-indicated (for instance, paranoia may be exacerbated by being contacted), 3) prisoner or otherwise under judicial order such that study participation could not be considered to be truly voluntary, or 4) doesn’t speak and read English well enough to consent and to understand texts in English. Participants could enter the study through clinician referral or self-referral. All self-referrals were confirmed as appropriate to participate by an installation clinician prior to screening.

This analysis included 470 active military servicemembers who completed pre-treatment assessments of bullying, level of suicidal ideation, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness. Similar to the larger military, participants ranged in age from 18 to 50 (M = 25.50, SD = 6.03) were mostly male (n = 392, 83.2%), two thirds European-American (n = 287, 60.9%). Three quarters self-identified as “exclusively heterosexual” (n = 359, 76.2%). All participants had completed high school or a GED, and approximately seven percent (n = 35) had attained a Bachelor’s degree or higher. Participants in this study were all active duty, and included Army soldiers (n = 264, 56.1%) and US Marines (n = 207, 43.9%). Approximately 40 percent (n = 198) of servicemembers reported at least one deployment in a combat zone.

Measures

We analyzed a subset of relevant measures from the MCP baseline dataset. The Scale for Suicide Ideation-Current (SSI-C) (Beck, Brown, & Steer, 1997; Beck, Brown, Steer, Dahlsgaard, & Grisham, 1999; Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979) is an interviewer-administered scale that measures the level of a servicemember’s suicidal ideation at its worst point in the past 2 weeks. This measure has been found to be a valid and reliable measure of 19 characteristics associated with suicidal ideation and intent.

The Bullying Survey (Hamburger, Basile, & Vivolo, 2011) was created from items in the Center for Disease Control (CDC)’s recent compendium of bullying assessment tools. The present study assessed three binary (yes/no) constructs: (1) having experienced bullying during school age (i.e., Based on the definition [of bullying], were you bullied during your school-age years?”), (2) having ever experienced workforce bullying (i.e., “Have you ever experienced bullying in your workplace (including during military service)?”), and having experienced bullying in the past six months (i.e., Have you been bullied in your workplace (including during military service) in the last six months?”). Additionally we collected information about frequency of bullying in the past six months (i.e., never, rarely, occasionally, frequently) and we assessed perceived reasons for being bullied by 17 categories (e.g., “Because of my appearance or weight; because of my religion”). Participants checked any and all categories that were applicable to them and the total count of perceived reasons for being bullied (i.e., 1 to 17) was used as a continuous variable in the analytic models.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) (Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Gordon, K. H., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. J., 2008) is an 18-item measure rated on a Likert scale from 0 (“Not at all true for me”) to 7 (“Very true for me”) and it assesses the extent to which individuals feel connected to others (i.e., belongingness), such as, “These days, I feel disconnected from other people;” and the extent to which they feel like a burden on the people in their lives (i.e., perceived burdensomeness), such as, “These days the people in my life would be better off if I were gone.” Psychometric results indicated that the latent variable thwarted belongingness significantly predicted suicidal ideation scores providing support for the construct validity of the thwarted belongingness latent variable. Strong evidence for convergent and discriminant validity was also found for the thwarted belongingness (Van Orden et al, 2008).

Procedure

Baseline surveys were completed with a licensed clinician using a REDCap online survey (Harris et al., 2009) or by paper and pencil if a computer with internet connection was not easily available. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Institutional review boards at the University of Washington, Womack Army Medical Center, and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Human Research Protection Office in addition to a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) and a Research Monitor approved and monitored the research protocol and adverse events throughout the trial. Recruitment took place at three military installations: an Army base in the Southern U.S., a Marine Corps base and nearby air stations in the Southern U.S., and a Marine Corps base in the Western U.S.

Analytic Strategy

The hypothesized mediation model was evaluated via a series of regressions using a product-of-coefficients approach (Hayes, 2013). Given our hypothesis that bullying would be associated with both TB and PB, and the related hypothesis concerning the indirect effect of bullying upon level of suicidal ideation via TB and PB, we evaluated these constructs as mediators rather than moderators of the association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation. The continuous variables of count of perceived reasons for being bullied in childhood and at workplace were used as predictor variables that represented bullying in analytic models. Age in years, gender, and childhood history of bullying (i.e., count of perceived reasons for being bullied in childhood) were chosen a priori as covariates in all analyses. All calculations were conducted in SPSS using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013), and the significance of indirect effects was assessed by calculating their associated 95% Bootstrap confidence intervals with 5,000 bootstrap samples. Confidence intervals that did not include zero were assumed to be statistically significant. Missing data were addressed via listwise deletion, as only one case had any missing data on variables included in the present analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

More than half (n = 268, 56.9%) of participants reported experiencing some form of bullying in their lifetime, and approximately one-third (n = 165, 35.0%) disclosed recent bullying at baseline (see Table 2). All participants reported at least one indicator of suicidal ideation, consistent with the inclusion criteria for the larger clinical trial, and scores on the SSI-C ranged from 1 to 34 (M = 17.03, SD = 8.51). Nearly all participants endorsed at least one aspect of perceived burdensomeness (n = 457, 97.0%; M = 3.61, SD = 1.48), and nearly all endorsed at least one aspect of thwarted belongingness (n = 460, 97.7% M = 4.26, SD = 1.42).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Timepoint of Bullying

| Yes, n(%) | No, n(%) | Missing, n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the Workplace (Including Military Service) | 206 (43.7) | 264 (56.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| In the Last Six Months | 165 (80.1) | 39 (18.9) | 2 (1.0) |

| Rarely | 43 (20.9) | ||

| Occasionally | 64 (31.1) | ||

| Frequently | 58 (28.2) | ||

| During Childhood | 268 (56.9) | 203 (43.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Participants’ self-reported perceived reasons for being bullied were varied, and several reasons for being bullied were pronounced: 114 participants (55.3% of those bullied) perceived they were being bullied because they were different, 106 participants (51.5%) perceived they were being bullied because of physical weakness or inability to keep up, 101 participants (49.0%) perceived they were being bullied because of their appearance or weight, 98 participants (47.6%) perceived they were being bullied because they didn’t get along with others, 43 participants (20.9%) perceived they were being bullied because of their race, ethnicity, or country of origin, and 32 participants (15.5%) perceived they were being bullied because people said they were gay. See Table 1 for further details.

Table 1.

Self-Reported Reasons for Bullying

| Yes, n(%) | No, n(%) | Missing, n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Because I was Different | 114 (55.3) | 89 (43.2) | 3 (1.5) |

| Because I Didn’t Get Along with Others | 98 (47.6) | 107 (51.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| They Said I was Gay | 32 (15.5) | 173 (84) | 1 (0.5) |

| Because of my Race, Ethnicity, or Country of Origin | 43 (20.9) | 161 (78.2) | 2(1.0) |

| Because of Physical Weakness / Inability to Keep Up | 106 (51.5) | 99 (48.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Because of My Appearance or Weight | 101 (49.0) | 102 (49.5) | 3 (1.5) |

Mediational Analyses

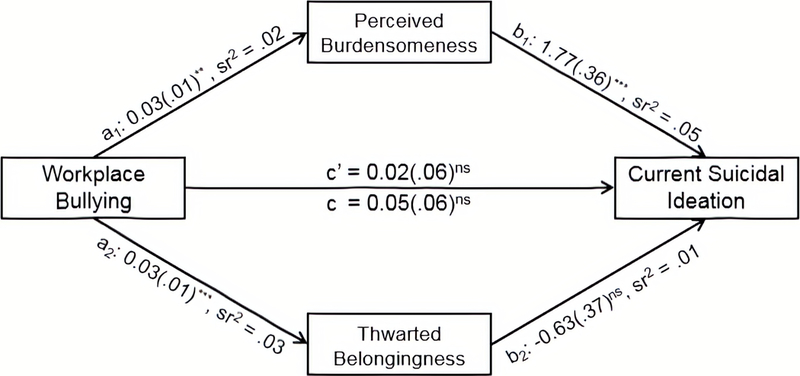

In the first regression model (see Figure 1 for more details) (a1-path; F(4, 465) = 7.61, p <.001, R2 = .06), number of perceived reasons for being bullied at workplace was a significant predictor of perceived burdensomeness (b[SEb] = 0.03[.01], 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.05, p = .002), above and beyond gender (b[SEb] = −0.38[.18], 95% CI: −0.73 to −0.03 p = .034), age (b[SEb] = −0.01[.01], 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.01, p = .347), and number of types of childhood bullying (b[SEb] = 0.03[.01], 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.05, p = .006). In the second regression model (a2-path; F(4, 465) = 5.45, p <.001, R2 = .04), perceived reasons for being bullied in the workplace was associated with thwarted belongingness (b[SEb] = 0.03[.01], 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.05, p < .001), above and beyond gender (b[SEb] = −0.23[.17], 95% CI: −0.57 to 0.11, p = .178), age (b[SEb] = −0.01[.01], 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.01, p = .307), and childhood bullying (b[SEb] = 0.01[.01], 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.03, p = .280).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediation model with unstandardized regression coefficients and squared semipartialcorrelations reported;N= 467.ns, nonsignificant. **p< .01 and ***p< .001

In the final regression model (b1- and b2-paths, and c’-path; F(6, 463) = 5.67, p <.001, R2 = .07), perceived burdensomeness (b[SEb] = 1.77[.36], 95% CI: 1.06 to 2.47, p < .001) was associated with current suicidal ideation, above and beyond gender (b[SEb] = −1.42[1.03], 95% CI: −3.45 to 0.61, p = .170), age (b[SEb] = −0.002[.06], −0.13 to 0.12, p = .971), and number of perceived reasons for being bullied in childhood (b[SEb] = −0.09[.06], 95% CI: −0.21 to 0.02, p = .138). Neither thwarted belongingness (b[SEb] = −0.63[.37], 95% CI: −1.35 to 0.10, p = .091), nor workplace bullying (b[SEb] = 0.02[.06], 95% CI: −0.09 to 0.13, p = .718) were significantly associated with level of suicidal ideation. Perceived burdensomeness was a significant mediator of the association between workplace bullying and level of suicidal ideation (Product-of-coefficients = .05, 95% Bootstrap CI = .003 to .071), but thwarted belongingness was not (Product-of-coefficients = −.02, 95% Bootstrap CI = −.055 to .001).

Discussion

Foremost, the present findings demonstrate the hypothesized indirect effect of workplace bullying upon level of current suicidal ideation via perceived burdensomeness, above and beyond the effects of age, gender, and childhood bullying. Our findings were consistent with extant work in female veterans exposed to military sexual trauma, which found only perceived burdensomeness but not thwarted belongingness to be significant in predicting suicidal ideation (Monteith, Bahraini, & Menefee, 2017). While military sexual trauma and bullying are conceptually distinct phenomena, it is nonetheless illustrative that, in both populations, suicidal ideation was underpinned by perceived burdensomeness. Similarly, the research conducted with active duty military personnel with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and those seeking outpatient mental health care (Bryan, Clemans, & Hernandez, 2012) found that only perceived burdensomeness and fearlessness about death were significant in predicting suicidality. These previous studies defined suicidality as previous suicide attempts, frequency of suicidal ideation, communication about suicidality, and likelihood of future suicide. Our work extends this literature by demonstrating workplace bulling to be indirectly associated with level of suicidal ideation via perceived burdensomeness in a large sample of Soldiers and Marines who expressed acute suicidality.

Our results combined with previous research suggest perceived burdensomeness is an antecedent for suicidality and therefore a potentially malleable point of therapeutic intervention. Burdensome cognitions (i.e. perceived burdensomeness) are hypothesized to be maladaptive misperceptions in nearly all cases (Hill & Pettit, 2016), and therefore can potentially be intervened upon by cognitive interventions. One such intervention, compuLsive Exercise Activity TheraPy (LEAP), uses CBT principles through a web-based platform, and targets perceived burdensomeness in adolescents to reduce risk for suicidality (Hill & Petit, 2016). LEAP successfully reduced burdensome cognitions, an effect that was strengthened over time (Hill & Petit, 2016), which provides reason for optimism that a similar intervention could be efficacious and adapted in a military population in the future. Furthermore, our finding that perceived burdensomeness, but not thwarted belongingness, mediated the association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation suggests that directly addressing one’s ability to make meaningful contributions may be a relatively more salient mechanism of suicide prevention than directly addressing sense of connectedness and belonging.

The military has recognized the prevalence of suicide in its ranks and has made a concerted effort to enact prevention programs. Our results serve to further inform the underlying mechanisms of action in suicidal military personnel, providing nuance to the understanding of specific targets of therapeutic intervention.

Limitations

Our findings are limited by the self-report and cross-sectional nature of the data collected, which do not support causal inference. These findings were based on data collected from treatment-seeking suicidal servicemembers and thus may not generalize to other military sub-populations or clinical samples outside of military contexts. Further, our assessment of bullying did not permit specific estimation of the frequency and duration of particular forms of bullying, and thus was limited to the count of different types of bullying that was included in the present analyses. This may have limited our ability to fully assess the impact of the severity and/or chronicity of bullying victimization that only represented one or few different types of bullying. Finally, our analysis of TB and PB as mediators of the association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation does not account for the interaction between these two variables, which has been found to be associated with suicide-specific outcomes. However, this association has tended to be small in magnitude, and recent scholarship has noted the need for both refinement of these constructs relative to the intractability of thwarted interpersonal needs, as well as investigation concerning the unique contribution of each variable above and beyond their interaction (Chu et al., 2017). Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate that bullying was indirectly associated with level of suicidal ideation via perceived burdensomeness, which suggests points of intervention for future efforts to prevent bullying-related suicidality.

Due to the cross-sectional nature of our study design, we are unable to disconfirm the possibility that burdensomeness drives bullying, rather than being an outcome of bullying. That is, it is possible that if an individual soldier is identified as at risk of suicide, that they may perceive themselves to be a burden on others, and in turn may be bullied because of related decrements in performance or engagement in unit activities. Further investigation of the origins of bullying behavior using prospective methods is warranted, and would allow for clarification as to the temporal precedence of burdensomeness and bullying with regard to suicidality.

Furthermore, our sample only included individuals with current suicidal ideation. Thus, we are unable to generalize our sample to military personnel at large and can only draw conclusions about military servicemembers currently experiencing suicidal ideation.

Lastly, though there is no established way to categorize severity of bullying, Van Noorden et al. (2016) found that in children who were bullied, frequency of bullying was not associated with perceived severity of bullying. For this reason, we chose to investigate whether the CDC’s compendium of bullying assessment tools adequately measured the holistic experience of bullying.

Implications

The present findings have important policy implications. Our findings demonstrate the need for bullying/hazing prevention programs of some sort. It is clear from our results that bullying is common in military culture, and that it can have potentially fatal outcomes. In a similar fashion, the Montreal Police Force developed an intervention called ‘Together for Life’, wherein the department aimed to address suicide among officers via training for all units (including an educational program to develop awareness of suicide and help-seeking), improving access to police-centric resources such as a police hotline, training of supervisors and union reps, and publicly campaigning for the program (Mishara & Martin, 2012). Police were tracked for 12 years, and showed significant improvement; police suicide rates declined by 78.9%, compared to an 11% increase in the control city (6.4 suicides per 100,000 and 29.0 suicides per 100,000, respectively; Mishara and Martin, 2012). Similar programs could be implemented in a military population, tailoring the program to fit institutional needs and catering to the specific risk factors that are empirically supported. There has been postulated similarity between military and police culture via organizational mimicry (Campbell & Campbell, 2014), which could suggest that interventions that have efficacy in the police could translate to military populations.

There have been a host of potential interventions suggested to reduce military suicide over the years. Isaac et al. (2009) suggested that training gatekeepers could be a useful means to reduce suicide, Comtois has investigated caring text messages (Comtois et al., 2019), Stanley et al. (2018) have discussed the development of safety plans, and Bryan (2011) has suggested the development of a crisis response plan to reduce suicidality. These brief suicide-specific interventions all address efforts to enhance connectedness and promote positive coping. The present findings support continued development of these and similar suicide-specific interventions to enhance the extent to which they explicitly address military servicemembers potentially compromised perceptions as to their ability to make meaningful contributions (i.e., perceived burdensomeness), as a mechanism for reducing risk of suicide. Additional research is necessary to understand the antecedents, predictors, mediators, and moderators of suicidality in the setting of bullying, so as to promote the tailoring of context and population-specific interventions.

Clinically, this research can be used to inform the dominant approaches to therapeutic intervention for suicide, such as Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CT-SP), developed by Brown and colleagues in 2005. Key to the success of CT-SP is the understanding of proximal risk factors and stressors (such as emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and familial processes surrounding a suicidal crisis; Stanley et al., 2009). Better understanding of these risk factors and stressors can help inform the therapeutic process, especially for military clinicians who need to understand the struggles their population faces.

Bullying remains an under-studied stressor within the workplace settings of military personnel, and should be more directly considered within the broader context of psychotherapy to prevent suicide for servicemembers. CT-SP is well-positioned to explicitly address cognitive distortions that arise within the domain of perceived burdensomeness, and thus may be especially effective for military personnel who experience suicidal thoughts in this context. This may be efficacious in helping individuals who perceived they were bullied due to being different, or because they didn’t get along with others. However, 51.5% of participants in our study reported being bullied for physical weakness or inability to keep up; in this instance, burdensomeness may be actual as well as perceived, in that they are potentially seen by their entire unit as a burden. In this way, CT-SP may not be sufficient as an intervention, as the burdensomeness is not merely perceived. Previous research has identified higher perceived burdensomeness among those with physical disabilities (Khazem, Jahn, Cukrowicz, & Anestis, 2015) and older adults (Cukrowicz, Cheavens, Van Orden, Ragain, & Cook, 2011), which suggests a need for tailored treatment for such individuals. Additionally, those bullied due to sexual orientation or race are members of socially vulnerable groups that are susceptible to higher rates of bullying, and may require programs specifically directed towards eliminating the bullying of minority groups (Llorent, Ortega-Ruiz, & Zych, 2016).

Beyond the relationship to suicidal ideation, bullying in the military may have unique weight in the military due to the acquired capacity for death that military servicemembers possess. Selby and colleagues (2010) offer that, by the interpersonal theory, military servicemembers are uniquely positioned to have acquired capability for suicide as a result of military training and combat exposure. Indeed, the type of training that members of the military receive may result in habituation specific to that training, as suggested by 2004 study by Scoville and colleagues. This is indicative that military servicemembers may be at heightened risk for suicide if they develop perceived burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness, which is consistent with the results from Silva and colleagues’ work (2017) that indicated that among US Army recruits with high perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness was associated with increased suicidal ideation. This effect that was especially pronounced among those with a high AC for suicide. Silva’s work is, further, consistent with research from Anestis, Khazem, Mohn, and Green (2015) that demonstrated that the interaction between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness was associated with suicidal ideation, and that the three-way interaction between thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and AC was associated with lifetime suicide attempts. This highlights the importance of continued work in understanding suicide in the military, a population that is at especially high risk for suicide.

Conclusion

Overall, our hypotheses were partially supported, and demonstrated results similar to other military samples. Our findings suggest potentially malleable points of therapeutic intervention, and demonstrated that workplace bullying in the military could be an antecedent to perceived burdensomeness, which in turn may be an antecedent to level of suicidal ideation. Given the elevated risk of suicidal behavior and death by suicide in the military, it is crucial that we tailor clinical, research, and policy outcomes to addressing this longstanding public health concern. Future work should include prospective designs that would permit causal inference concerning the role of perceived burdensomeness as an intervening variable via repeated measurements over time. Future studies should also explore other mediators of the association between bullying and level of suicidal ideation, including perceptions of parental and familial connectedness, caring relationships with others, unit cohesion, and perceived safety in the workplace as possible protective factors against bullying-related suicidality. Finally, future studies should employ more detailed measures of bullying severity and duration, including severity and duration of specific types of bullying to allow for more nuanced understanding of these dimensions (see Table 1 for different reasons for bullying; it is conceivable different types of bullying could lead to different outcomes, but this phenomenon has not been studied as of yet).

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under Award No. W81XWH-10–2-0181. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army Medical Department, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or the Military Suicide Research Consortium. The preparation of this article was also supported in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Development of the National Institutes of Health (T32HD057822; DeCou). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Anestis MD, Khazem LR, Mohn RS, & Green BA (2015). Testing the main hypotheses of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a large diverse sample of United States military personnel. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 78–85. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archuleta D, Jobes D, Pujol L, Jennings K, Crumlish J, Lento R, Brazaitis K, Moore B, & Crow B, (2014). Raising the clinical standard of care for suicidal soldiers: An army process improvement initiative. U.S. Army Medical Department journal Oct-Dec. 55–66. [PubMed]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, & Steer RA (1997). Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00073-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA, Dahlagaard KK, & Grisham JR (1999) Suicide ideation at its worst point: A predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, & Weissman A (1979). Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 47, 343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake CA, Rojas SM, Badour CL, Dutton CE, & Feldner MT (2017). Self-disgust as a potential mechanism underlying the association between PTSD and suicide risk. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 47, 1–9. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, & Beck AT (2005). Cognitive Therapy for the Prevention of Suicide Attempts: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 294(5), 563–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, & Hernandez AM (2012). Perceived burdensomeness, fearlessness of death, and suicidality among deployed military personnel. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 374–379. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Stone SL, & Rudd MD (2011). A practical, evidence-based approach for means-restriction counseling with suicidal patients. Professional Psychology, 42, 339–346. doi: 10.1037/a0025051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, & Campbell K (2016). Police/military convergence in the USA as organisational mimicry. Policing and Society, 26, 332–353. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona RA, & Ritchie EC (2007). U.S. military enlisted accession mental health screening: History and current practice. Military Medicine, 172(1), 31–35. 10.7205/MILMED.172.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, et al. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. 10.1037/bul0000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Kerbrat AH, DeCou CR, Atkins DC, Majeres JJ, Baker JC & Ries RK (2019). Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 474–483. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukrowicz KC, Cheavens JS, Van Orden KA, Ragain RM, & Cook RL (2011) Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychology and Aging 26, 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRosa GA, & Goodwin GF, (2014). Moving Away from Hazing: The Example of Military Initial Entry Training. AMA Journal of Ethics, 16(3), 204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Watson RJ, Adjei J, Homma Y, & Saewyc E (2016). Sexual orientation trends and disparities in school bullying and violence-related experiences, 1999–2013. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 386–396. 10.1037/sgd0000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger ME, Basile KC, & Vivolo AM (2011). Measuring Bullying Victimization, Perpetration, and Bystander Experiences: A Compendium of Assessment Tools Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez SM (2015). A Better Understanding of Bullying and Hazing in the Military. Military Law Review, 415–439.

- Hill RM, & Pettit JW (2016). Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of LEAP: A Selective Preventive Intervention to Reduce Adolescents’ Perceived Burdensomeness. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–12. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom MA, Stanley IH, Schneider ME, & Joiner TE (2017). A systematic review of help-seeking and mental health service utilization among military servicemembers. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 59–78. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac M, Elias B, Katz LY, et al. (2009). Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), 260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T Why people die by suicide Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Khazem LR, Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC, & Anestis MD, (2015). Physical disability and the interpersonal theory of suicide. Death Studies, 39, 641–646. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2015.1047061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller KM, Miriam M, Hall KC, Marcellino W, Mauro JA, & Lim N (2015). Hazing in the U.S. Armed Forces: Recommendations for Hazing Prevention Policy and Practice, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-941-OSD, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Llorent VJ, Ortega R, & Zych I (2016). Bullying and cyberbullying in minorities: Are they more vulnerable than the majority group? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner A, Page K, Witt K, & LaMontagne AD (2016). Psychosocial Working Conditions and Suicide Ideation: Evidence From a Cross-Sectional Survey of Working Australians. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(6), 584–587. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara BL, & Martin N (2012). Effects of a Comprehensive Police Suicide Prevention Program. Crisis, 33(3), 162–168. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith LL, Bahraini NH, & Menefee DS (2017). Perceived Burdensomeness, Thwarted Belongingness, and Fearlessness about Death: Associations With Suicidal Ideation among Female Veterans Exposed to Military Sexual Trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12), 1655–1669. 10.1002/jclp.22462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, & Scott JG (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60. 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MB, Nielsen GH, Notelaers G, & Einarsen S. Workplace bullying and suicidal ideation: A 3-wave longitudinal Norwegian study. Am J Public Health 2015;11:e23–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock Matthew K., Deming CA, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Goldenberg M, Kessler RC, … Ursano RJ. (2013). Suicide Among Soldiers: A Review of Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 76(2), 97–125. 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.2.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman K, Czyz EK, Gipson PY, & King CA (2015). Connectedness and Perceived Burdensomeness among Adolescents at Elevated Suicide Risk: An Examination of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(3), 385–400. 10.1080/13811118.2014.957451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østvik K., & Rudmin F. (2001). Bullying and hazing among Norwegian army soldiers: Two studies of prevalence, context and cognition. Military Psychology, 13, 17–39. doi: 10.1207/S15327876MP1301_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair K, Poteat V, & Koenig B (2012). Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 493–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville SL, Gardner JW, Magill AJ, Potter RN, & Kark JA (2004). Nontraumatic deaths during U.S. Armed Forces basic training, 1977–2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 26(3), 205–212. 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Ribeiro JD, Nock MK, Rudd MD, … Joiner TE (2010). Overcoming the fear of lethal injury: Evaluating suicidal behavior in the military through the lens of the Interpersonal–Psychological Theory of Suicide. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 298–307. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M-L, Fear NT, Rona RJ, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Jones N, & Goodwin L (2015). Stigma as a Barrier to Seeking Health Care Among Military Personnel With Mental Health Problems. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37(1), 144–162. 10.1093/epirev/mxu012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, Hagan CR, Rogers ML, Chiurliza B, Podlogar MC, Hom MA, … Joiner TE (2017). Evidence for the Propositions of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide Among a Military Sample: Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 669–680. 10.1002/jclp.22347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, Galfalvy HC, Currier GW, Knox KL, Chaudhury SR, Bush AL, Green KL, (2018). Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention With Follow-up vs Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA, Wells K, Poling K, Curry J, et al. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): Treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 1005–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazikawa R, Maughan B, &Arseneault L, (2014). Adult Health Outcomes of Childhood Bullying Victimization: Evidence From a Five-Decade Longitudinal British Birth Cohort. Am J Psychiatry, 171, 777–784. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teismann T, & Forkmann T (2017). Rumination, Entrapment and Suicide Ideation: A Mediational Model: Rumination, Entrapment and Suicide Ideation: A Mediational Model. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 226–234. 10.1002/cpp.1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier S-G, Fernet C, Austin S, & Boudrias V. (2016). Work environment antecedents of bullying: A review and integrative model applied to registered nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 55, 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Defense. (2017). Hazing Prevention and Response in the Armed Forces: Annual Summary Report to Congress Washington, DC: Office of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity. [Google Scholar]

- Van Noorden TH, Bukowski WM, Haselager GJ, Lansu TA, & Cillessen AH (2016). Disentangling the Frequency and Severity of Bullying and Victimization in the Association with Empathy. Social Development, 25(1), 176–192. doi: 10.1111/sode.12133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, & Joiner TJ (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H, Cruz M, Shuey B, Smithers D, Muncy L, & Noble M (2018). Military personnel who seek health and mental health services outside the military. Military Medicine, 183(5–6), e232–e240. 10.1093/milmed/usx051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, & Lereya ST (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–885. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]