Abstract

Introducing degrees of unsaturation into small molecules is a central transformation in organic synthesis. A strategically useful category of this reaction type is the conversion of alkanes into alkenes for substrates with an adjacent electron-withdrawing group. An efficient strategy for this conversion has been deprotonation to form a stabilized organozinc intermediate that can be subjected to α,β-dehydrogenation through palladium or nickel catalysis. This general reactivity blueprint presents a window to uncover and understand the reactivity of Pd- and Ni-enolates. Within this context, it was determined that β-hydride elimination is slow and proceeds via concerted syn-elimination. One interesting finding is that β-hydride elimination can be preferred to a greater extent than C–C bond formation for Ni, more so than with Pd, which defies the generally assumed trends that β-hydride elimination is more facile with Pd than Ni. The discussion of these findings is informed by KIE experiments, DFT calculations, stoichiometric reactions, and rate studies. Additionally, this report details an in-depth analysis of a methodological manifold for practical dehydrogenation and should enable its application to challenges in organic synthesis.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Polarized alkenes are regularly employed functional groups for enabling regioselective addition reactions. Their utility and versatility lead to their widespread occurrence as synthetic intermediates in the multistep synthesis of natural products, pharmaceuticals, and other complex small molecules. While numerous building blocks can give rise to polarized alkenes, one particularly advantageous approach is to desaturate the positions adjacent to the electron-withdrawing groups. In particular, the goal to introduce an olefin next to a carbonyl has propelled the development of several methodologies.1

To access this vital class of α,β-unsaturated compounds, direct α,β-dehydrogenation from their ubiquitous saturated counterparts is a straightforward strategy. Classic approaches for carbonyl dehydrogenation typically involve two steps: introduction of the necessary oxidation state at the carbonyl α-position, followed by an elimination reaction (e.g., α-halocarbonyl elimination, selenoxide sigmatropic rearrangement, etc.).2

The global strategy to prefunctionalize and, in a subsequent operation, generate an alkene has also been employed in transition metal catalysis. In pioneering dehydrogenation studies in 1978, Saegusa demonstrated that enoxysilanes could undergo transmetalation to provide palladium enolates that yield enones upon β-hydride elimination.3 Relatedly, Tsuji showed that allyl-Pd enolates generated from either allyl β-keto esters or allyl enol carbonates could also form enones through decarboxylation (Figure 1A).4 More recently, Stahl developed a single-step aerobic dehydrogenation of aldehydes and ketones using catalytic Pd.5

Figure 1.

Previous dehydrogenation methodologies.

The general challenge with these approaches has been that they are either limited to more acidic carbonyls (e.g., ketones and aldehydes) or that they require multiple steps. We addressed this key challenge by inventing a mechanistic approach to dehydrogenate a wide range of electron-deficient molecules in a single operation.6 To date, numerous elegant one-step α,β-dehydrogenations of ketones and aldehydes have been developed,7 while our group reported several methods for less acidic functionalities, including esters, amides, carboxylic acids, nitriles, and heterocycles.8 Other methods have also emerged that complement our approach and the accompanying scope. Dong and co-workers reported a Pd- or Pt-catalyzed desaturation of lactams using boron enolates and shortly thereafter reported a strategy utilizing Cu-catalyzed enolization, followed by oxidative elimination to access unsaturated lactones, lactams, and ketones (Figure 1B).9 Huang has reported a dehydrogenation of amides and carboxylic acids, which proceeds through an allyl-Ir intermediate to generate dienes (Figure 1C).10 A one-pot electrophilic activation followed by selective selenium(IV)-mediated α,β-dehydrogenation of amides has also been reported by Maulide.11 Yu and co-workers achieved the Pd-catalyzed dehydrogenation of carboxylic acids via their weak coordination approach and β-C–H activation (Figure 1D).12 Additionally, Baran reported an electrochemical desaturation of carbonyl-containing compounds, highlighting the complementarity of this approach to reported metal-catalyzed methodologies.13 Specifically, our group showed that Pd- and Ni-catalyzed methods using either stoichiometric allyl or aryl oxidants could be developed to promote α,β-dehydrogenation of ketones, esters, amides, carboxylic acids, nitriles, and heterocycles (Figure 1E).8 The development of these methodologies has enabled access to synthetically useful unsaturated molecules, as shown in Figure 1F.6,14 Many transition metal-catalyzed dehydrogenation methods are still being developed, underscoring the importance of this transformation.15

Questions of Mechanistic Interest.

After the successful development of our α,β-dehydrogenation approach, many questions were prompted by the mechanism of these Pd- and Ni-catalyzed reactions. Can dehydrogenation serve as a mechanistic probe to learn about the fundamental reactivity differences between Pd and Ni? Does the metal amide base play a role outside of enolate formation? How can undesired pathways involving incorporation of the oxidant be suppressed? Which step or steps are turnover limiting and how can they be accelerated? In this report, we describe insights into the mechanism of our reported allyl-Pd-/Ni-catalyzed α,β-dehydrogenation reactions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mechanistic Blueprint.

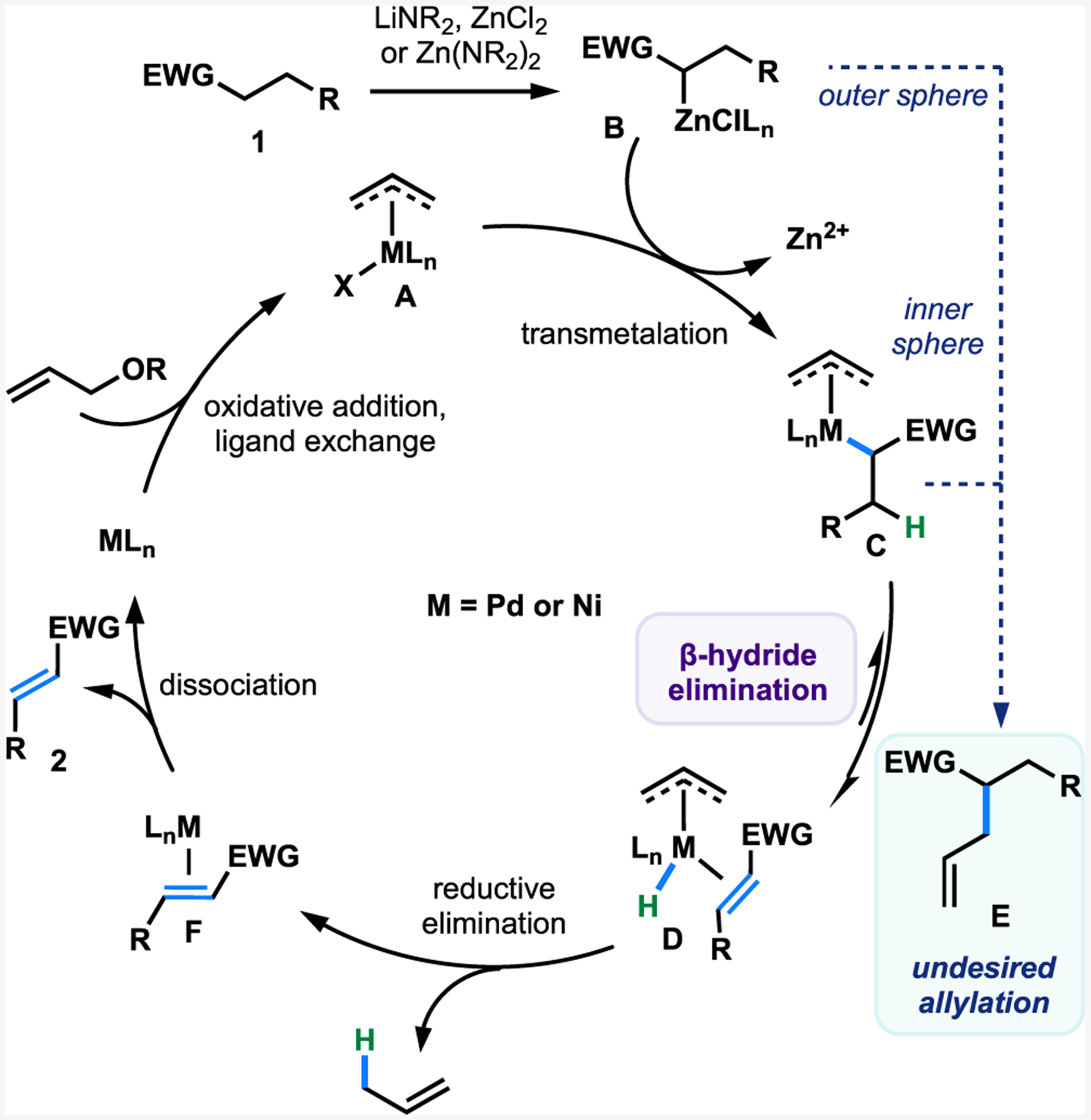

Throughout the development of our dehydrogenation strategy, we envisioned a plausible mechanism (Figure 2) inspired by Tsuji’s pioneering efforts.4a It should be noted that the mechanistic blueprint in Figure 2 is meant as a guide for reaction optimization. Allyl-metal complex A undergoes transmetalation with zinc enolate B, which is formed from in situ deprotonation of the substrate, resulting in allyl-metal enolate C. Subsequent β-hydride elimination gives the desired product and allyl-metal hydride species D, which undergoes reductive elimination to generate propene gas and a low-valent metal species. Oxidative addition with an allyl oxidant regenerates active allyl-metal catalyst A. Alternative reactivity would be observed if intermediate C undergoes reductive elimination instead of β-hydride elimination to form allylation product E or if nucleophilic substitution of allyl-metal species A occurs with enolate B.

Figure 2.

Proposed catalytic cycle.

A number of variations on this proposed cycle can be envisioned, but our attention has focused mostly on the key selectivity questions that relate to β-hydride elimination. One alternative possibility to that elementary step is that species F could be formed directly from species C via a concerted transfer of the hydride to the allyl ligand. An additional possibility is that instead of β-hydride elimination, a Yu-type directed C–H insertion occurs.12 Even along the path outlined in Figure 2, there is the potential to form multimetallic intermediates wherein either multiple Pd/Ni catalytic centers are involved or mixed metallic intermediates with Zn and a catalytically active metal center participate synergistically.16 Furthermore, the aggregation state of the enolate is not known, and monomers, dimers, tetramers, and other mono- or mixed metallic aggregates are conceivable and even likely.17 Considerations about the enolate structure and the role of multimetallic intermediates are certainly important but are beyond the scope of the present study.

Base Effects.

The role of the base is complicated in α,β-dehydrogenation by serving the primary function of enolate formation and the secondary function of impacting the speciation of the catalytically active metal. While differences in the base employed can alter enolate structure, and that aggregation state is likely important,17 we focused our attention on the impact that this reaction component may have on Pd or Ni catalysis.18 We examined whether lithium amide bases are essential to the reaction and found that they impact the efficiency of the transformation beyond deprotonation (Table S1). Even for substrates that cannot adopt E-and Z-diastereomeric enolates, the base impacts the synthetic efficiency to a significant extent. We then determined the extent to which the base impacts the rate of dehydrogenation, as evaluated in the Supporting Information (Figure S4). While LiTMP is competent in the reaction, using LiCyan results in an increased initial rate of the reaction, as well as improved yields.

Using amide 1a as a substrate, we compared the rates of dehydrogenation using lithium cyclohexyl(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)amide (LiCyan, 2) and LiTMP as the base for both Pd and Ni catalysts. The product was generated significantly faster and in higher yield when Pd was used as the catalyst with LiCyan as the base (Figure S4, gray line vs yellow line). With Ni as the catalyst, the initial reaction rates among LiCyan and LiTMP were approximately comparable, but LiCyan provided a higher yield of the desired product by more than 20% (Figure S4, blue line vs orange line). That said, these results do not rule out that the base may influence the aggregation state of the deprotonated substrates.

A byproduct of this transformation is derived from the oxidation of CyanH (3) to the corresponding imine (4). We postulate that Cyan imine (4) is formed via β-hydride elimination of an N-bound Pd complex.19,20 In order to test this hypothesis, we subjected LiCyan (2) to dehydrogenation reaction conditions using a stoichiometric amount of [Pd-(allyl)Cl]2, and 8% of CyanH and 76% of imine 4 were recovered (Figure 3A). This imine (4) is formed when LiCyan reacts directly with allyl-Pd/Ni species such as the monomer 5 or the corresponding dimer. This would occur via the transmetalation of LiCyan to 6, followed by β-hydride elimination to yield 4. Reacting catalytic amounts of [Pd-(allyl)Cl]2 or Ni(dme)Br2 with LiCyan under the same conditions at ambient temperature generated a similar ratio of CyanH and imine 4 that was observed in the stoichiometric reaction (9:1, Cyan imine/CyanH). These experiments demonstrate that even though the base is sterically hindered, it is capable of binding to Pd and Ni centers.

Figure 3.

Examination of CyanH and its derivatives as ligands.

In order to determine whether 3 or 4 could bind to the metal center, we evaluated this question by 1H NMR. A solution of CyanH (3) and a stoichiometric amount of [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 did not show evidence of complexation (Figure 3B), even after refluxing in THF-d8. However, Cyan imine (4) was discovered to bind to [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 at ambient temperature, as evidenced by the 1H NMR spectrum in Figure 3. These spectra show deviated shifts for the allylic protons and significant peak broadening consistent with previously reported amino-Pd-allyl complexes.21 In the case of LiCyan (2), an unstable complex forms, as evidenced by the formation of Pd black upon treatment of LiCyan with a Pd(II) source. These results are surprising, as there are sparse examples of monodentate amides binding to transition metals in the context of catalysis.19

Given the presence of Pd- and Ni-bound intermediates, we set out to determine whether Cyan imine, CyanH, or LiCyan had an influence on the rate or efficiency of catalysis. Three supplementary time-track experiments were carried out with catalytic amounts of Cyan imine (Figure 3C, green line), CyanH (red line), or LiCyan (pink line) with Pd or Ni as the catalyst and LiTMP as base. The addition of 0.20 equiv of Cyan imine significantly decreased the amount of product formed for both Pd and Ni, presumably via coordination that inhibits catalysis. Based on the data obtained from Figure 3, we conclude that Cyan imine, which can coordinate to the metal center, inhibits Pd- and Ni-catalyzed dehydrogenation.

The addition of 0.20 equiv of CyanH (red line) did not significantly increase or decrease the yield for either Ni or Pd. These data show that for the Ni-catalyzed dehydrogenation, LiTMP and its TMPH participate less productively in the reaction than LiCyan and its CyanH (orange line vs blue line).

Interestingly, when 0.20 equiv of LiCyan (pink line) were added using Pd as the catalyst, the yield could be recovered completely. However, for the analogous experiment with Ni as the catalyst, the yield decreases dramatically. These results suggest that Cyan increases the initial rate and overall yield of the reaction for Pd, but that this effect is not translatable to the Ni-based system.

From the rate experiments in Figure 3, it is evident that Cyan imine acts as an inhibitor in both the Pd and Ni dehydrogenation reactions. This may be due to the binding of the imine to the metal center. However, alternatives such as the imine impacting speciation of the lithium or zinc enolates cannot be ruled out. At this juncture, the structural basis for how the amide base impacts the speciation of the Pd and Ni centers is unknown.

Inhibition Studies.

In addition to the imine byproduct, we hypothesized that other reaction components that coordinate to the metal center, such as electron-deficient alkenes, decrease the rate of dehydrogenation. We conducted a series of experiments that demonstrate that alkene products act as inhibitors, reducing yields of dehydrogenation by 20–100% (Supporting Information, Figure S5 and Table S2).22

A variety of allyl electrophiles, precatalysts, metal salt additives, and Zn sources were examined in comprehensive optimization studies, and the results of those studies can be found in the Supporting Information (Tables S5–S8). Interestingly, when LiOH or LiCl are added, yields decreased to 84 and 78% (from 91%) under Pd-catalyzed conditions; under Ni-catalyzed conditions, these effects are more pronounced, with yields decreased to 68 and 4% (from 90%). These outcomes are indicative of the greater moisture sensitivity of the Ni-catalyzed reaction relative to the Pd-catalyzed condition.

Avoiding C–C Bond Formation.

Allylation is the primary undesired pathway in Pd-catalyzed α,β-dehydrogenation of carbonyls via enolates when allyl oxidants are employed (Figure 4A). Allylation products could arise both from the conventional mechanism wherein the enolate attacks at the electrophilic carbon of the allyl unit, and additionally, these could be generated after transmetalation via an inner-sphere reductive elimination of an allyl-metal-enolate intermediate.23,24 A concern with using this mechanistic approach is that the extent of dehydrogenation can be limited by the possibility of both inner- and outer-sphere reductive elimination.

Figure 4.

Allylation is suppressed by ZnCl2.

As a representative example, for α-aryl nitrile 1b, without the addition of ZnCl2, the allylation byproduct 9b is observed in high yield (Figure 4B, 80% for Pd and 60% for Ni), which we attribute to its increased nucleophilicity. However, with the addition of ZnCl2, allylation is observed to a lesser extent under Pd-catalyzed conditions (16%) and is entirely eliminated under Ni-catalyzed conditions. This may be due to the decreased nucleophilicity of the softer zinc enolate compared to the lithium enolate and the greater propensity of zinc enolates to undergo transmetalation.25 The difference in reactivity between Ni and Pd with regard to C–C bond formation may be due to the differential electronegativity of the allyl-metal species.26

The degree of allylation is substrate-dependent, and the addition of ZnCl2 to form zinc enolates generally overcomes this side reactivity (Supporting Information, Table S4). The decreased propensity for Ni to undergo reductive elimination is beneficial in this reaction by decreasing the likelihood of undesired allylation.27 A full discussion regarding allylation can be found in the Supporting Information (SI-54–59).

Rate-Determining Steps.

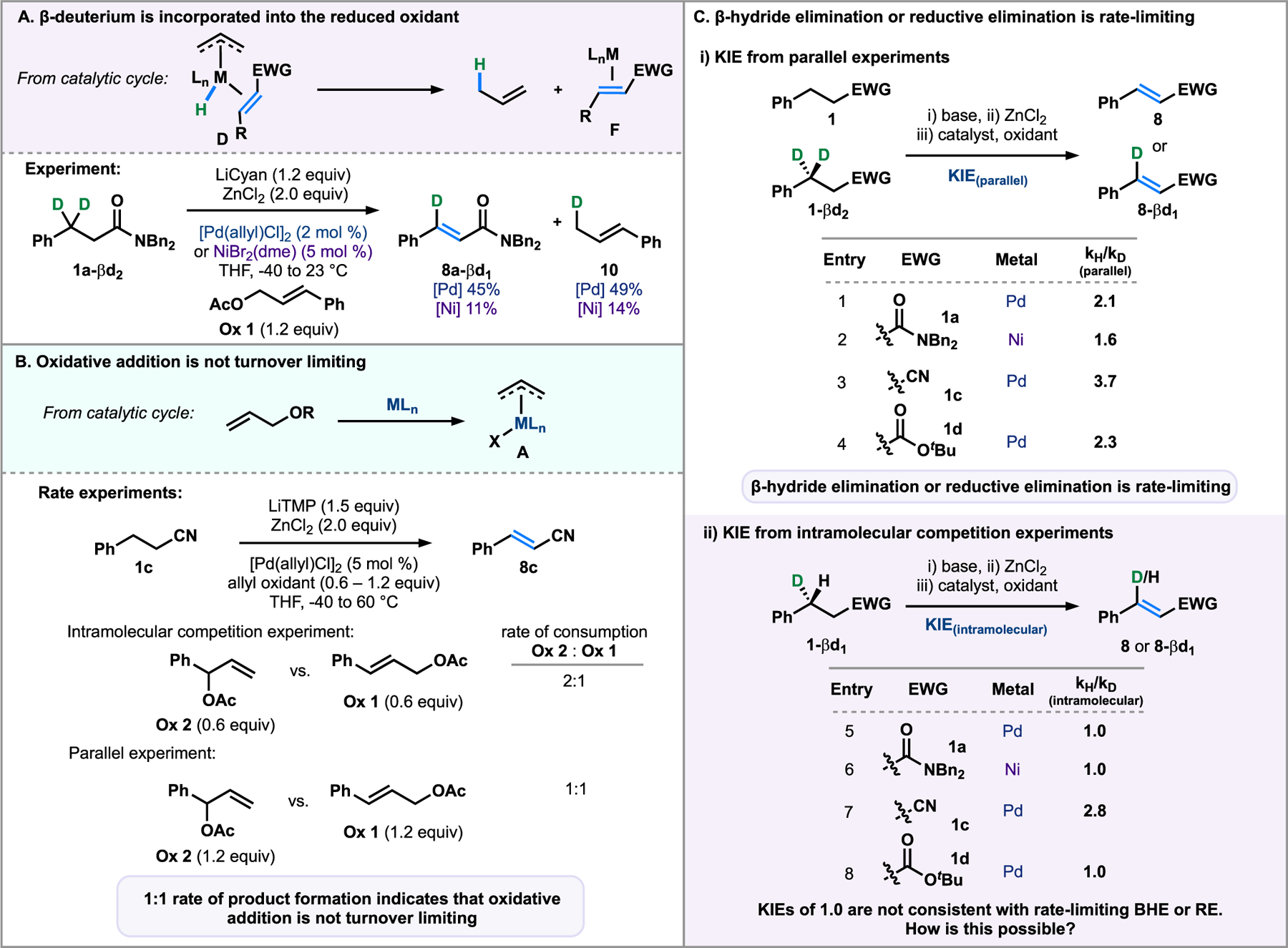

To confirm that the hydride at the β-position is incorporated into propene gas, cinnamyl acetate was substituted for allyl acetate in a typical dehydrogenation reaction (Figure 5A) so that the formation of the reduced oxidant could more easily be monitored. The dehydrogenation was performed with amide 1a-βd2 and less volatile Ox 1 using both palladium and nickel, which yielded 45 and 11% of unsaturated amide 8a-βd1 and 49 and 14% of 10. This indicates that the eliminated deuterium is incorporated into the allyl benzene and provides support for our proposed mechanism involving β-hydride elimination, followed by reductive elimination.

Figure 5.

From KIE and competition experiments, β-hydride elimination or reductive elimination is turnover limiting.

We designed a competition experiment to evaluate whether oxidative addition is turnover limiting by analyzing differences in rate when branched or linear allyl oxidants are employed (Figure 5B).28 For a competition experiment where these oxidants are used in equal portions in the same reaction vessel, the extent of conversion for the more reactive branched oxidant (Ox 2) was double that of the linear cinnamyl acetate (Ox 1, 2:1).28 Given this difference in rate, if the rate-determining step involved oxidative addition, it would be expected that the more reactive branched oxidant would have an overall faster rate of reaction than the linear oxidant. However, a significant rate difference was not observed when these two oxidants were used in parallel reactions (1:1), ruling out oxidative addition as a possibility for the slow step of the reaction.29

We questioned whether β-hydride elimination from intermediate C and/or reductive elimination from intermediate D could be turnover limiting, so we conducted a series of kinetic isotope effect (KIE) studies (Figure 5C, Supporting Information Figures S1–S3). If a primary KIE were observed when measured by parallel experiments, the turnover-limiting step would involve C–H bond cleavage or formation, either through β-hydride elimination or reductive elimination.30 These experiments were performed with an amide, ester, and nitrile substrate. Under Pd catalysis, primary KIE values were observed and ranged from 2.1–3.7 (entries 1, 3, and 4), whereas under Ni-catalyzed conditions a somewhat lower value (1.6, entry 2) was observed. This outcome is consistent with values determined by Hartwig and Alexanian with related Ptenolate complexes (KIE = 3.2).31 These results indicate that C–H bond cleavage and/or formation—here, β-hydride elimination and/or reductive elimination—are slow steps for each of the cases surveyed.30 This data also rules out transmetalation as the turnover-limiting step, as we would not expect a primary KIE to be observed from parallel rate experiments.

An intramolecular competition experiment with a mono-β-deutero-substrate (1-βd1) was also used as a mechanistic probe.31 For the intramolecular competition experiment, during the β-hydride elimination, either C–H or C–D bond cleavage must occur, which was anticipated to result in a normal primary KIE value, given the parallel KIE measurement above. However, in the intramolecular competition experiments, striking KIE values of 1.0 were observed for both the amide (1a, entry 5) and the ester (1d, entry 8) under Pd-catalyzed conditions. Ni-catalyzed conditions also resulted in a KIE value of 1.0 for 1a (entry 6). Similarly, for the nitrile substrate (1c, entry 7), there is a depreciation of the value of the parallel KIE measurement from 3.7 to a lower value of 2.8 for the intramolecular competition experiment.31 The unusual outcome that there is a KIE from the parallel experiments but not from the intramolecular measurements provides a mechanistic opportunity.32

The peculiar differences in KIE values were reproducible across conditions and substrates and perplexing, such that additional study was warranted to uncover the phenomena underlying these findings. From the observation of this phenomenon for substrate 1d-βd1 (Figure 6A), it was previously proposed that a reversible β-hydride elimination is followed by a turnover-limiting reductive elimination.8a Alternatively, the extent of proteo- or deuterioproduct formation, 8 or 8-βd1, for the intramolecular competition experiment could be a function of the facial selectivity of transmetalation to form one of two diastereomeric Pd or Ni C-bound enolates. The metal would either be syn or anti to the deuterium. Via a presumed syn-β-hydride elimination, pro-8 could lead only to 8, and pro-8-βd1 could lead only to 8-βd1, which would obfuscate the attempted isotopic measurement.

Figure 6.

Lack of facial selectivity results in an intramolecular KIE of 1.0.

This mechanistic suggestion warranted an additional measurement of the intramolecular competition experiment that would eliminate facial selectivity as a potential contributor (Figure 6B). Substrate 1e-βd2 is not subject to the same limitations of 1d-βd1, and for 1e-βd2, a primary KIE value of 4.0 was observed. This finding is consistent with turnover-limiting β-hydride elimination and/or reductive elimination and suggests that if β-hydride elimination is reversible, it does not lead to differentiation of intramolecular and parallel KIE results.

This interpretation requires that interconversion between the C-bound Pd or Ni facial diastereomers (via the O-bound enolate 11) is less facile than product formation (Figure 6C). Consistent with this view, the energy of the O-bound enolate intermediate is considerably higher than the transition state energies that correspond to β-hydride elimination and reductive elimination (see SI Figures S9–11). Given this mechanistic consideration, the stereoselectivity of C-bound Pd enolate formation would dictate which β-hydrogen undergoes elimination due to the conformational preference about the σCα–Cβ bond rather than an otherwise equivalent selection between H and D isotopes. Consequently, it would be expected that a 1:1 mixture of products would arise from the experiment because only subtle differences in agostic interactions could differentiate the energies of these diastereomers.33 Rotation of pro-8d followed by syn-elimination would lead to the Z-product. However, only the E-alkene product was observed experimentally. Alternatively, if this rotation were to occur, then an anti-elimination would be required to generate the same E-product. However, the deuterium labeling experiment shown in Figure 5A, wherein allylbenzene is produced as the deuterated product, is indicative of a syn-elimination pathway. Furthermore, the comparison of the geminal-intramolecular KIE value (1.0) and that of the additional intramolecular KIE measurement with 1e-βd2 (4.0) suggests that interconversion between the C-bound Pd enolates is less facile than product formation.

Computational Study.

In order to gain insights into whether β-hydride elimination and/or reductive elimination is turnover limiting, we used density functional theory (DFT) to calculate the transition states for β-hydride elimination for both Ni- and Pd-catalyzed pathways (Figure 7A). Benzyl groups were truncated to methyl groups to reduce computational cost, and calculations were performed at the ωb97X-D/6–311+G(d,p)-LANL2DZ(Ni,Pd)//ωb97X-D/def2TZVP-LANL2DZ(Pd,Ni)-SMD-THF level of theory. Broader examination of other functionals, such as B3LYP-D3 and M06, and basis sets can be found in the Supporting Information (Tables S10 and S11).

Figure 7.

β-Hydride elimination is a turnover-limiting step and proceeds through concerted syn-elimination. Calculations were performed at the ωb97X-D/6–311+G(d,p)-LANL2DZ(Ni,Pd)//ωb97X-D/def2TZVP-LANL2DZ(Pd,Ni)-SMD-THF level of theory.

We constrained our analysis to monometallic Pd intermediates that proceed via Pd(0/II)-catalysis, as this is the simplest scenario that may provide general insights into the elementary steps of interest. Two different mechanistic pathways were examined for the conversion of the C-bound metal enolates to the metal-coordinated products, namely, from neutral and halide-bound anionic complexes. For the neutral transition state, an (η3-allyl)-metal complex was the lowest in energy, and a transition state for the syn-coplanar β-hydride elimination was located. For the anionic transition state, an (η1-allyl)-metal complex was the lowest in energy and lacks the open coordination site for an inner sphere syn-β-hydride elimination, such that direct transfer of a hydride from the substrate to the allyl group was located (Figure 7A).34

These two pathways were compared for Ni and Pd. The transition state barriers for both Ni and Pd in the neutral pathway are lower than the anionic pathway (Figure 4, ΔG‡ = 5.9 vs 9.8 kcal/mol in the neutral pathway and 13.2 vs 16.4 kcal/mol in the anionic pathway). The higher barrier for the anionic pathway is consistent with the observation that excess salts reduce conversion and yield (Table S7). More surprisingly, the barriers for β-hydride elimination for the Ni-catalyzed pathways were lower in energy than the barriers for the transition states in the Pd-catalyzed pathways.35

For the lower-energy neutral pathway, we computed the barrier for reductive elimination for Pd (Figure 7B). We found that the barrier for reductive elimination is significantly lower in energy than the barrier for β-hydride elimination (ΔG‡ = 3.0 vs 9.8 kcal/mol). Additionally, from the allyl-metal hydride intermediate (14), the barriers for the reverse pathway showed a value comparable to the reductive elimination step. These calculations were conducted with the ωb97X-D functional and the def2TZVP basis set with implicit solvation correction, and additionally, the same conclusions are derived from other levels of theory (see Supporting Information, Figure S6). These calculations are consistent with the KIE data that implicate β-hydride elimination and reductive elimination as turnover-limiting steps.

For β-hydride elimination, there are several pathways that could be operative for this elementary step (Figure 7C). An anti-elimination (Path A), wherein an exogenous base deprotonates the β-position and eliminates the metal has been proposed for related π-allyl Pd intermediates.36 However, as shown in Figure 5A, H (or D) at the β-position is incorporated into the allyl oxidant, which rules out this pathway as a possibility.

A direct hydride transfer pathway (Path B), wherein a metal-hydride species is not formed, and the β-hydrogen is transferred directly to the allyl oxidant, is another mechanistic possibility.34c,37 However, Figure 7A shows that the transition states for the anionic pathway that proceeds via a direct hydride transfer are ~7 kcal/mol higher in energy than the corresponding transition states in the neutral pathway. This significant energetic difference argues against a direct hydride transfer pathway.

A β-C–H insertion pathway could also be operative, similar to the mechanism recently proposed by Yu and co-workers in their method for the dehydrogenation of carboxylic acids (Path C).12a In this mechanism, an O-bound Pd-center could induce C–H functionalization of the β-position, reductively eliminate the hydride and allyl ligands, and then undergo β-elimination by the enolate to give the desired product. Unlike a mechanism involving a concerted syn-elimination, it is not expected that the C–H insertion pathway via the O-bound Pd atom would have the same consequences as the facial selectivity of the Pd atom of the C-bound Pd enolate. The C–H insertion pathway (Path C) would not be expected to give rise to the observed intramolecular competition experiment (KIE = 1.0). Therefore, this pathway is ruled out as a possible mechanism.

The final pathway discussed herein is a concerted syn-elimination via a four-membered transition state to give a metal-hydride species that undergoes reductive elimination (Path D). Experimentally, this pathway is supported by the isotope labeling studies described in Figure 5A, wherein the deuterium from the substrate is incorporated into the allyl oxidant, suggesting that either syn-elimination or direct hydride transfer to the allyl oxidant is operative. Lastly, the DFT calculations show that the syn-elimination pathway is lower in energy compared with a direct hydride transfer pathway.

SUMMARY

In summary, a detailed mechanistic study of the Pd- and Ni-catalyzed α,β-dehydrogenation of electron-withdrawing groups has been conducted. There were several key findings that may be useful to those attempting to employ this methodological approach and perhaps to other reaction types. Based on the KIE measurements (Figures 5 and 6) and computational data (Figure 7), the turnover-limiting steps are β-hydride elimination and reductive elimination. C–C bond formation via allylation was identified as the primary side reaction. It was found that zinc enolate intermediates are essential to inhibit allylation and improve the yield of dehydrogenation (Figure 4).

OUTLOOK

An advantage of concerted efforts to develop first-row transition metal catalysis is their generally more favorable sustainability and costs.26,38 The complementary differences in reactivity up or down a periodic group provide opportunities to control selectivity in a predictable fashion. Continued comparative investigations into catalysis will allow for the development of new methods and mechanistic pathways to subvert generally assumed reactivity trends across metals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for financial support from Yale University, the NSF (CHE-1653793 and GRFP to A.K.B.), the ACS Petroleum Research Fund, and the NIH (GM118614). Additional support comes from the Swiss National Science Foundation (fellowship to Y.S.). Dr. Fabian Menges is gratefully acknowledged for obtaining the high-resolution mass spectrometry data. Additionally, we would like to thank Prof. Robert H. Crabtree for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c02572.

Primary NMR FID files for compounds (R)-1c-βd1, 8a-Z, SI-2-βd2, 1c-βd2, 4, 9a, 1a, 1a-βd1, 1a-βd2, SI-11, 8a, 8a-βd1, SI-14, SI-9, SI-8, and 1e-βd2 (ZIP)

Experimental procedures, spectroscopic data for all new compounds including 1H- and 13C NMR spectra, XYZ coordinates, and full computational details (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.joc.3c02572

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Alexandra K. Bodnar, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States

Suzanne M. Szewczyk, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States

Yang Sun, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States.

Yifeng Chen, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States.

Anson X. Huang, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States

Timothy R. Newhouse, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, United States

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- (1).Knochel P; Molander GA Comprehensive Organic Synthesis; Newnes, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Miller B; Wong H-S Reactions of 2-Phenylcyclohexanone Derivatives. A Re-Examination. Tetrahedron 1972, 28, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stotter PL; Hill KA α-Halocarbonyl Compounds. II. A Position Specific Preparation of α-Bromoketones by Bromination of Lithium Enolates. Position-Specific Introduction of α,β-Unsaturation into Unsymmetrical Ketones. J. Org. Chem 1973, 38, 2576–2578. [Google Scholar]; (c) Reich HJ; Reich IL; Renga JM Organoselenium Chemistry. A-Phenylseleno Carbonyl Compounds as Precursors for α,β-Unsaturated Ketones and Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 5813–5815. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sharpless KB; Lauer RF; Teranishi AY Electrophilic and Nucleophilic Organoselenium Reagents. New Routes to α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 6137–6139. [Google Scholar]; (e) Reich HJ; Wollowitz S Preparation of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds and Nitriles by Selenoxide Elimination. Org. React 1993, 44, 1–296. [Google Scholar]; (f) Trost BM; Salzmann TN; Hiroi K New Synthetic Reactions. Sulfenylations and Dehydrosulfenylations of Esters and Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98, 4887–4902. For a review, see: [Google Scholar]; (g) Newhouse T; Turlik A; Chen Y Dehydrogenation Adjacent to Carbonyls Using Palladium-Allyl Intermediates. Synlett 2015, 27, 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Ito Y; Hirao T; Saegusa T Synthesis of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds by Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Dehydrosilylation of Silyl Enol Ethers. J. Org. Chem 1978, 43, 1011–1013. [Google Scholar]; (b) Theissen R A New Method for the Preparation of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds. J. Org. Chem 1971, 36, 752–757. [Google Scholar]; (c) Larock RC; Hightower TR; Kraus GA; Hahn P; Zheng D A Simple, Effective, New, Palladium-Catalyzed Conversion of Enol Silanes to Enones and Enals. Tetrahedron Lett 1995, 36, 2423–2426. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Shimizu I; Tsuji J Palladium-Catalyzed Decarboxylation–Dehydrogenation of Allyl β-Keto Carboxylates and Allyl Enol Carbonates as a Novel Synthetic method for α-Substituted α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 5844–5846. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shimizu I; Minami I; Tsuji J Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of α,β-Unsaturated Ketones from Ketones via Allyl Enol Carbonates. Tetrahedron Lett 1983, 24, 1797–1800. [Google Scholar]; (c) Minami I; Takahashi K; Shimizu I; Kimura T; Tsuji J New Synthetic methods for α,β-Unsaturated Ketones, Aldehydes, Esters and Lactones by the Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions of Silyl Enol Ethers, Ketene Silyl Acetals, and Enol Acetates with Allyl Carbonates. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 2971–2977. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Diao T; Stahl SS Synthesis of Cyclic Enones via Direct Palladium-Catalyzed Aerobic Dehydrogenation of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 14566–14569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Diao T; Wadzinski TJ; Stahl SS Direct Aerobic α,β-Dehydrogenation of Aldehydes and Ketones with a Pd(TFA)2/4,5-diazafluorenone Catalyst. Chem. Sci 2012, 3, 887–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Huang D; Newhouse TR Dehydrogenative Pd and Ni Catalysis for Total Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 1118–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) For selected reviews:Muzart, J. One-Pot Syntheses of α,β-Carbonyl Compounds through Palladium-Mediated Dehydrogenation of Ketones, Aldehydes, Esters, Lactones and Amides. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2010, 2010, 3779–3790. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stahl SS; Diao T Oxidation Adjacent to C = X Bonds by Dehydrogenation in Comprehensive Organic Synthesis II Knochel P, Molander GA, Eds.; Elsevier, 2014; Vol. 7, pp 178–212. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen H; Liu L; Huang T; Chen J; Chen T Direct Dehydrogenation for the Synthesis of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal 2020, 362, 3332–3346. [Google Scholar]; (d) Gnaim S; Vantourout JC; Serpier F; Echeverria PG; Baran PS Carbonyl Desaturation: Where Does Catalysis Stand? ACS Catal 2021, 11, 883–892. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Chen Y; Romaire JP; Newhouse TR Palladium-Catalyzed α,β-Dehydrogenation of Esters and Nitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5875–5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Y; Turlik A; Newhouse TR Amide α,β-Dehydrogenation Using Allyl-Palladium Catalysis and a Hindered Monodentate Anilide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao Y; Chen Y; Newhouse TR Allyl-Palladium-Catalyzed α,β-Dehydrogenation of Carboxylic Acids via Enediolates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 13122–13125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang D; Zhao Y; Newhouse TR Synthesis of Cyclic Enones by Allyl-Palladium-Catalyzed α,β-Dehydrogenation. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 684–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang P; Huang D; Newhouse TR Aryl-Nickel-Catalyzed Benzylic Dehydrogenation of Electron-Deficient Heteroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1757–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Chen M; Dong G Direct Catalytic Desaturation of Lactams Enabled by Soft Enolization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7757–7760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen M; Rago AJ; Dong G Platinum-Catalyzed Desaturation of Lactams, Ketones, and Lactones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 16205–16209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen M; Dong G Copper-Catalyzed Desaturation of Lactones, Lactams, and Ketones under pH-Neutral Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 14889–14897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wang Z; He Z; Zhang L; Huang Y Iridium-Catalyzed Aerobic α,β-Dehydrogenation of γ,δ-Unsaturated Amides and Acids: Activation of Both α- And β-C-H Bonds through an Allyl-Iridium Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Teskey CJ; Adler P; Gonçalves CR; Maulide N Chemoselective α,β-Dehydrogenation of Saturated Amides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Wang Z; Hu L; Chekshin N; Zhuang Z; Qian S; Qiao JX; Yu J-Q Ligand-Controlled Divergent Dehydrogenative Reactions of Carboxylic Acids via C-H Activation. Science 2021, 374, 1281–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sheng T; Zhuang Z; Wang Z; Hu L; Herron AN; Qiao JX; Yu J-Q One-Step Synthesis of β-Alkylidene-γ-lactones via Ligand-Enabled β,γ-Dehydrogenation of Aliphatic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 12924–12933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gnaim S; Takahira Y; Wilke HR; Yao Z; Li J; Delbrayelle D; Echeverria PG; Vantourout JC; Baran PS Electrochemically Driven Desaturation of Carbonyl Compounds. Nat. Chem 2021, 13, 367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhao L-P; Zhang S-Y; Liu H-K; Cheng Y-J; Liu Z-P; Wang L; Tang Y Insights into Stereoselectivity Switch in Michael Addition-Initiated Tandem Mannich Cyclizations and Their Extension from Enamines to Vinyl Ethers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 15553–15564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).For additional recently reported metal-mediated carbonyl dehydrogenation methods, see:; (a) Wang M-M; Ning X-S; Qu J-P; Kang Y-B Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Linear α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes with Oxygen at Room Temperature Enabled by tBuONO. ACS Catal 2017, 7, 4000–4003. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shang Y; Jie X; Jonnada K; Zafar SN; Su W Dehydrogenative Desaturation-Relay via Formation of Multicenter-Stabilized Radical Intermediates. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen M; Dong G Platinum-Catalyzed α,β-Desaturation of Cyclic Ketones through Direct Metal-Enolate Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 7956–7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang X-W; Jiang G-Q; Lei S-H; Shan X-H; Qu J-P; Kang Y-B Iron-Catalyzed α,β-Dehydrogenation of Carbonyl Compounds. Org. Lett 2021, 23, 1611–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yu W-L; Ren Z-G; Ma K-X; Yang H-Q; Yang J-J; Zheng H; Wu W; Xu P-F Cobalt-Catalyzed Chemoselective Dehydrogenation through Radical Translocation under Visible Light. Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 7947–7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yang S; Fan H; Xie L; Dong G; Chen M Photoinduced Desaturation of Amides by Palladium Catalysis. Org. Lett 2022, 24, 6460–6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Li H; Yin C; Liu S; Tu H; Lin P; Chen J; Su W Multiple Remote C(sp3)-H Functionalizations of Aliphatic Ketones via Bimetallic Cu-Pd Catalyzed Successive Dehydrogenation. Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 13843–13850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Pérez-Temprano MH; Casares JA; Espinet P Bimetallic Catalysis using Transition and Group 11 Metals: An Emerging Tool for C-C Coupling and Other Reactions. Chem.–Eur. J 2012, 18, 1864–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pye DR; Mankad NP Bimetallic Catalysis for C-C and C-X Coupling Reactions. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 1705–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ackerman-Biegasiewicz LK; Kariofillis SK; Weix DJ Multimetallic-Catalyzed C-C Bond Forming Reactions: From Serendipity to Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 6596–6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Reich HJ Role of Organolithium Aggregates and Mixed Aggregates in Organolithium Mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 7130–7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Van der Steen FH; Boersma J; Spek A; Van Koten G Synthesis and Properties of Novel Organozinc Enolates of N, N-disubstituted Glycine Esters. Molecular Structure of [cyclic] [EtZnOC(OMe):C(H)N(tert-Bu)Me]4. Organometallics 1991, 10, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar]; (c) Collum DB; McNeil AJ; Ramirez A Lithium Diisopropylamide: Solution Kinetics and Implications for Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2007, 46, 3002–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hall PL; Gilchrist JH; Harrison AT; Fuller DJ; Collum DB Mixed Aggregation of Lithium Enolates and Lithium Halides with Lithium 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidide (LiTMP). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 9575–9585. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhang P; Cantrell RL; Newhouse TR Role of Benzylic Deprotonation in Nickel-Catalyzed Benzylic Dehydrogenation. Synlett 2021, 32, 1652–1656. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Jacobs BP; Wolczanski PT; Lobkovsky EB Oxidatively Triggered Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation in Ene-Amide Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2016, 55, 4223–4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Muzart J On the Behavior of Amines in the Presence of Pd(0) and Pd(II) Species. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem 2009, 308, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hegedus LS; Aakermark B; Olsen DJ; Anderson OP; Zetterberg K (pi-Allyl) Palladium Complex Ion Pairs Containing Two Different, Mobile. pi-allyl groups: NMR and X-ray Crystallo-graphic Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 697–704. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lau J; Sustmann R Diethyl-2,2’-bipyridyl-palladium(II), a Case for the Study of Combination vs. Disproportionation Products. Tetrahedron Lett 1985, 26, 4907–4910. [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Trost BM; Van Vranken DL Asymmetric Transition Metal-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylations. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 395–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM; Crawley ML Asymmetric Transition-Metal Catalyzed Allylic Alkylations: Applications in Total Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2921–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Weaver JD; Recio III A; Grenning AJ; Tunge JA Transition-Metal Catalyzed Decarboxylative Allylation and Benzylation Reactions. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 1846–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) James J; Jackson M; Guiry PJ Palladium-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation: Development, Mechanistic Understanding and Recent Advances. Adv. Synth. Catal 2019, 361, 3016–3049. [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) Steinhagen H; Reggelin M; Helmchen G Palladium-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylation with Phosphinoaryldihydrooxazole Ligands: First Evidence and NMR Spectroscopic Structure Determination of a Primary Olefin–Pd0 Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1997, 36, 2108–2110. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bai D-C; Yu F-L; Wang W-Y; Chen D; Li H; Liu Q-R; Ding C-H; Chen B; Hou X-L Palladium/N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysed Regio and Diastereoselective Reaction of Ketones with Allyl Reagents via Inner-Sphere Mechanism. Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sha SC; Jiang H; Mao J; Bellomo A; Jeong SA; Walsh PJ Nickel-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylation with Diarylmethane Pronucleophiles: Reaction Development and Mechanistic Insights. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 1070–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Jarugumilli GK; Zhu C; Cook SP Re-Evaluating the Nucleophilicity of Zinc Enolates in Alkylation Reactions. Eur. J. Org Chem 2012, 2012, 1712–1715. [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Tasker SZ; Standley EA; Jamison TF Recent Advances in Homogeneous Nickel Catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ananikov VP Nickel: The “Spirited Horse” of Transition Metal Catalysis. ACS Catal 2015, 5, 1964–1971. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chernyshev VM; Ananikov VP Nickel and Palladium Catalysis: Stronger Demand than Ever. ACS Catal 2022, 12, 1180–1200. [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Mackenzie PB; Whelan J; Bosnich B Asymmetric Synthesis. Mechanism of Asymmetric Catalytic Allylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 2046–2054. [Google Scholar]; (b) Osakada K; Chiba T; Nakamura Y; Yamamoto T; Yamamoto A Steric Effect of Substituents in Allylic Groups in Oxidative Addition of Allylic Phenyl Sulphides to a Palladium (0) Complex. C-S Bond Cleavage Triggered by Attack of Pd on the Terminal Carbon of the C-C Double Bond. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1986, 21, 1589–1591. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kurosawa H; Kajimaru H; Ogoshi S; Yoneda H; Miki K; Kasai N; Murai S; Ikeda I Novel Syn Oxidative Addition of Allylic Halides to Olefin Complexes of Palladium (0) and Platinum (0). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 8417–8424. [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Trost BM; Verhoeven TR Allylic Alkylation. Palladium-Catalyzed Substitutions of Allylic Carboxylates. Stereo-and Regiochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 4730–4743. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM; Ariza X Enantioselective Allylations of Azlactones with Unsymmetrical Acyclic Allyl Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 10727–10737. [Google Scholar]

- (30).(a) Gómez-Gallego M; Sierra MA Kinetic Isotope Effects in the Study of Organometallic Reaction Mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 4857–4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Simmons EM; Hartwig JF On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C–H Bond Functionalizations by Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Alexanian EJ; Hartwig JF Mechanistic Study of β-Hydrogen Elimination from Organoplatinum (II) Enolate Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 15627–15635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Jones WD Isotope Effects in C-H Bond Activation Reactions by Transition Metals. Acc. Chem. Res 2003, 36, 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).(a) Brookhart M; Green ML Carbon-Hydrogen-Transition Metal Bonds. J. Organomet. Chem 1983, 250, 395–408. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ryabov AD; Sakodinskaya IK; Yatsimirsky AK Kinetics and Mechanism of Ortho-Palladation of Ring-Substituted N,N-Dimethylbenzylamines. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1985, 12, 2629–2638. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ryabov AD Chem. Rev 1990, 2, 403–424. [Google Scholar]; (d) Crabtree RH Transition Metal Complexation of σ Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1993, 32, 789–805. [Google Scholar]; (e) Brookhart M; Green ML; Parkin G Agostic Interactions in Transition Metal Compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2007, 104, 6908–6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).(a) Solin N; Szabó KJ Mechanism of the η3–η1–η3 Isomerization in Allylpalladium Complexes: Solvent Coordination, Ligand, and Substituent Effects. Organometallics 2001, 20, 5464–5471. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM; Bunt RC On the Effect of the Nature of Ion Pairs as Nucleophiles in a Metal-Catalyzed Substitution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 70–79. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sakaki S; Satoh H; Shono H; Ujino Y Ab Initio MO Study of the Geometry, η3⇄η1 Conversion, and Reductive Elimination of a Palladium (II) η3-Allyl Hydride Complex and Its Platinum (II) Analogue. Organometallics 1996, 15, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar]

- (35).(a) Lin B-L; Liu L; Fu Y; Luo S-W; Chen Q; Guo Q-X Comparing Nickel-and Palladium-Catalyzed Heck Reactions. Organometallics 2004, 23, 2114–2123. [Google Scholar]; (b) Menezes da Silva VH; Braga AA; Cundari TR N-Heterocyclic Carbene Based Nickel and Palladium Complexes: A DFT Comparison of the Mizoroki-Heck Catalytic Cycles. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3170–3181. [Google Scholar]

- (36).(a) Andersson PG; Schab S Mechanism of the Palladium-Catalyzed Elimination of Acetic Acid from Allylic Acetates. Organometallics 1995, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar]; (b) Takacs JM; Lawson EC; Clement F On the Nature of the Catalytic Palladium-Mediated Elimination of Allylic Carbonates and Acetates to Form 1,3-Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 5956–5957. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Biswas B; Sugimoto M; Sakaki S Theoretical Study of the Structure, Bonding Nature, and Reductive Elimination Reaction of Pd (XH3)(η3-C3H5)(PH3)(X = C, Si, Ge, Sn). Hypervalent Behavior of Group 14 Elements. Organometallics 1999, 18, 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- (38).For reviews and perspectives, see:; (a) Zweig JE; Kim DE; Newhouse TR Methods Utilizing First-Row Transition Metals in Natural Product Total Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 11680–11752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holland PL Reaction: Opportunities for Sustainable Catalysts. Chem 2017, 2, 443–444. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayler JD; Leahy DK; Simmons EM A Pharmaceutical Industry Perspective on Sustainable Metal Catalysis. Organometallics 2019, 38, 36–46. [Google Scholar]; (d) Haibach MC; Ickes AR; Wilders AM; Shekhar S Recent Advances in Nonprecious Metal Catalysis. Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 2428–2444. [Google Scholar]; (e) Rana S; Biswas JP; Paul S; Paik A; Maiti D Organic Synthesis with the Most Abundant Transition Metal - Iron: From Rust to Multitasking Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50, 243–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.