Abstract

The impact of chronic urticaria on work has been scarcely reported, whereas its peak incidence is between the ages of 20 and 40. The aim of this study was to assess the occupational impact of chronic urticaria and its treatment, by combining objective and patient-reported data. A monocentric observational study was performed using questionnaires over a 1-year period from 2021 to 2022 in chronic urticaria patients who were in a period of professional activity and agreed to participate. Of the 88 patients included, 55.7% assessed the occupational impact of their chronic urticaria as significant, and even more severe when chronic urticaria was poorly controlled. Some 86% of patients had symptoms at work, in a third of cases aggravated by work. However, occupational physical factors were not associated with an aggravation of inducible chronic urticaria. A total of 20% reported treatment-related adverse effects affecting their work. Despite low absenteeism, presenteeism and reduced productivity were important (> 20%). Six patients (6.8%) had difficulties keeping their work. For 72.7% of the patients, the occupational physician was not informed. The occupational impact of chronic urticaria should be discussed during consultations, particularly when it is insufficiently controlled. The occupational physician should be informed in order to support patients’ professional project.

SIGNIFICANCE

Chronic urticaria is frequent and its peak incidence occurs during the occupational period of life. However, specific assessment of the occupational impact of chronic urticaria is insufficiently reported. By combining objective and patient-reported data, this French monocentric study showed that for more than half of the patients urticaria and/or its treatment had a subjective significant impact on their occupational life, even more severe when urticaria was poorly controlled. Absenteeism was low and few patients were fired because of urticaria, but presenteeism and reduced productivity were important. Importantly, the occupational physicians were not informed enough, whereas they could support patients’ professional project.

Key words: chronic spontaneous urticaria, chronic inducible urticaria, occupational status, work impairment, productivity impairment, presenteeism

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a common dermatosis, affecting approximately 1% of the general population, mostly between the ages of 20 and 40 (1), thus during the full working period. Fleeting, pruritic, sometimes diffuse erythemato-papular rash can associate with transient angioedema that can be disfiguring, painful or disabling when involving the joints areas. In a given individual, attacks may occur unpredictably (chronic spontaneous urticaria, CSU) and/or be triggered by physical factors (chronic inducible urticaria, CIndU), which may be present at work: friction, pressure, exposure to cold, heat, etc. (2).

The duration of chronic urticaria is unpredictable, averaging between 1 and 4 years, and sometimes several decades (3) and there is no curative treatment. Symptomatic treatment is based on 2nd-generation anti-H1 antihistamines (2GAH1) and the anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab for CSU only. Nevertheless, disease control is frequently incomplete, sometimes due to undertreatment (4).

The impact of CU on quality of life is considerable (5). Several recent studies have suggested an impact on the professional sphere in terms of presenteeism and loss of productivity based on the WPAI-CU (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Chronic Urticaria) score (6–9). In the workplace, CIndU could theoretically be improved by avoiding physical triggers. Moreover, disfiguring angioedema is less frequent during CIndU than CSU. However, CIndU may preferentially affect hands and feet exposed to a physical factor such as pressure or friction, and in patients with cold urticaria a massive occupational exposure to cold may induce dizziness or even an anaphylactic reaction. Moreover, CIndU is more refractory to antihistamines, and is not a marketing indication for omalizumab (10). Finally, the average duration of CIndU is longer than CSU. To assess and compare the occupational impact of CSU and/or CIndU and their treatment, we used objective data combined with patient-reported data in a prospective monocentric study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary endpoint

We assessed the subjective impact of CSU versus CIndU on patients’ working time using a self-questionnaire with a visual analogue scale graduated from 0 to 10, but without visible annotation of the graduation lines (in line with the recommendations for assessment of the impact of CU (3) and of professional difficulties in the literature [11–13]). A VAS response > 5 was considered as reflecting a significant impact of CU on life at work, and a VAS response ≥ 7 as a severe impact.

Secondary endpoints

We compared the medico-social consequences of CSU versus CIndU in terms of number and duration of work stoppages, job loss, workstation adjustments, change of profession, etc. We also compared the WPAI-CU score (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Chronic Urticaria) in CSU versus CIndU patients (11).

Study population

We conducted a monocentric descriptive observational study using questionnaires in the dermato-allergology department of Montpellier University Hospital.

All adult patients referred between 19 July 2021 and 22 July 2022 with a known diagnosis of CU (follow-up visit) or established in the department (following consultation or additional examinations) and meeting the diagnostic criteria for CU according to the recommendations of the French Society of Dermatology were included successively (14). The diagnosis of CIndU was systematically confirmed by provocation tests according to the latest recommendations (15).

Patients with a diagnosis of contact urticaria, acute urticaria, protein contact dermatitis, students who had never worked, retired people, adults under protective measures and patients for whom the questionnaire was impossible to complete due to difficulties of comprehension or expression, or for any other reason not allowing standardized data collection, were excluded.

Survey

An original questionnaire was designed for the study, including a 3-part self-questionnaire for the patients and a single questionnaire for the physicians.

The following data were collected: age, sex, smoking habits, type of CU, age at diagnosis, age on first symptoms, treatment and comorbidities, socio-professional characteristics (employment status, professional category, sector of professional activity, length of service in the company, etc.), and level of education assessed on the basis of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 (16). For simplicity’s sake, the first 3 of the 9 levels were grouped together (levels 0, 1 and 2 corresponding to pre-primary education through to secondary school in France). Sectors of activity and professional categories were determined according to the second Revision of the French National Classification of Activities 2008 (NAF) (16) and the short titles of the 2020 nomenclature of Occupations and Socio-professional Categories (PCS) (17) using the 2-position levels of the PCS 2020 nomenclature. In addition, the questionnaire included 14 questions with visual analogue scales (VAS) graduated from 0 to 10, with no annotation of the graduation lines (3, 11, 15, 16), and the following validated standardized questionnaires: UCT (Urticaria Control Test), CU-Q2oL (Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire) and WPAI-CU (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Chronic Urticaria).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GMRC Shiny Stats® (https://lepcam.fr/index.php/ressources/logiciels-statistiques/gmrc-shiny-stats/) and pvalue.io® (https://www.pvalue.io/) software. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and confidence intervals were estimated at 95%.

Variables were presented in numbers and percentages. Quantitative variables were described by their means and standard deviations in the case of a Gaussian distribution, or by their medians and interquartile ranges (Q1–Q3) in the opposite case.

Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test, a Mann–Whitney test or a Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the conditions under which the tests were applied. Qualitative variables were compared using a χ2 or Fischer test, depending on the test conditions.

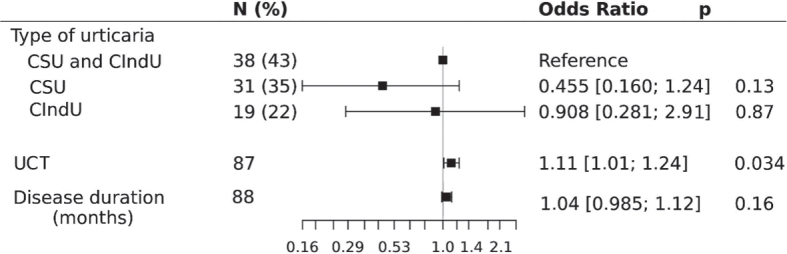

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed to explore any potential link between a significant occupational impact of CU (VAS > 5) and the type of CU when adjusted for disease duration and control. Odds ratio with their 95% confidence interval are presented.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 88 patients (mean age 40.9 ± 12 years, 60.2% female) were included (Table I). 35.2% (n = 31) had isolated CSU, 21.6% (n = 19) had isolated CIndU and 43.2% (n = 38) had a combination of CSU and CIndU. Four patients (4.5%) had a combination of two different CIndUs.

Table I.

Characteristics of the population (n = 88)

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 35 (39.8) |

| Female | 53 (60.2) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 40.9 ± 12 |

| Type of urticaria, n (%) | |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | 31 (35.2) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria | 38 (43.2) |

| Chronic inducible urticaria | 19 (21.6) |

| Type of chronic inducible urticaria, n (%) | |

| Dermographism | 40 (45.5) |

| Cold urticaria | 4 (4.6) |

| Cholinergic urticaria | 5 (5.7) |

| Delayed-pressure urticaria | 8 (9.1) |

| Vibratory urticaria | 2 (2.3) |

| Aquagenic urticaria | 2 (2.3) |

| Angioedema, n (%) | 44 (50) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | 24 (27.2) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria | 18 (20.5) |

| Chronic inducible urticaria | 2 (2.3) |

| Age at onset, years, mean ± SD | 36.6 + 14 |

| Disease duration, months, mean ± SD | 55.4 ± 76.1 |

| Median [interquartile range] | 24.0 [7–60] |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 56 (63.4) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 29 (33) |

| Asthma | 11 (12.5) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 22 (25) |

| Auto-immune thyroiditis | 9 (10.2) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 6 (6.8) |

| Eczema | 4 (4.5) |

| Psoriasis | 1 (1.1) |

| Treatment, n (%) | 80 (90.9) |

| 2GAH1 | 71 (80.7) |

| Omalizumab | 26 (29.6) |

| Others | 5 (5.7) |

| Urticaria Control Test, mean ± SD | 7.3 ± 4.6 |

| < 12: poorly controlled disease, n (%) | 71 (81.6) |

| ≥ 12: well-controlled disease, n (%) | 16 (18.3) |

| CU-Q2oL, mean ± SD | 49.7 ± 18.6 |

SD: standard deviation; CU-Q2oL: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire; 2GAH1: 2nd-generation anti-H1-antihistamines.

Fifty percent of patients (n = 44) reported episodes of angioedema, mostly of the face, and nine patients (10.2%) regularly reported angioedema of the hands.

At the time of completing the questionnaire, 90.9% (n = 80) were receiving medication. A total of 52 patients (65%) were on 2GAH1 alone and 26 patients (32.5%) were on omalizumab, including 19 patients (23.8%) on 2GAH1 and omalizumab; 5.7% (n = 5) of patients were treated with another therapy.

CU was poorly controlled, with a mean UCT score of 7.3 ± 4.6. Quality of life appeared moderately impaired, with a mean CU-Q2oL score of 49.7 ± 18.6/115.

Occupational characteristics of the study population

In all, 96.6% of the patients were working at the time of completing the questionnaire, including 2/3 with a fixed-term contract (Table II). The average salary was between once and twice the minimum growth wage (SMIC) in France in 46.5% of cases, and between two and three times the SMIC in a third.

Table II.

Socio-professional characteristics of the study population

| Currently employed, n (%) | 85 (96.6) |

| Type of employment contract, n (%) | |

| Fixed-term contract | 8 (9.4) |

| Permanent contract | 39 (45.9) |

| Civil servant | 16 (18.8) |

| Seasonal workers | 1 (1.2) |

| Self-employed | 17 (20.0) |

| Other | 4 (4.7) |

| Full-time contract, n (%) | 77 (90.6) |

| Part-time contract, n (%) | 8 (9.4) |

| Length of service in the company, n (%) | |

| 0–4 years | 46 (54.1) |

| 5–10 years | 10 (11.8) |

| 11–14 years | 8 (9.4) |

| 15–20 years | 7 (8.2) |

| Over 20 years | 14 (16.5) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |

| No diploma | 16 (18.2) |

| College | 21 (23.9) |

| Between college and bachelor’s degree | 13 (14.8) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 (14.8) |

| Master’s degree | 22 (25.0) |

| Doctorate | 3 (3.4) |

| Professional sector of activity (group NAF codes), n (%) | |

| Construction (F) | 12 (13.6) |

| Industries (C, D) | 7 (8.0) |

| Health and social care (Q, S) | 25 (28.4) |

| Tertiary services (J, K, L, N, O) | 17 (19.3) |

| Others (A, G, H, I, P, R) | 27 (30.7) |

| Socio-professional categories (PSC), n (%) Farmers Craftsmen, shopkeepers, company directors Executives, higher intellectual occupations Intermediate occupation Employees Workers |

2 (2.3) 7 (8.0) 22 (25.0) 18 (20.5) 29 (33.0) 10 (11.4) |

| Working with the public, n (%) | 66 (77.5) |

| Physical work, n (%) | 43 (50.6) |

| Work involving fine manual tasks, n (%) | 40 (47.1) |

| Working outdoor, n (%) | 23 (27.1) |

NAF: 2008 French National Classification of Activities (letters in parentheses correspond to professional sectors); PSC: French Classification of Occupations and Socio-Professional Categories (2020).

Occupational impact of chronic urticaria

A total of 85.9% of patients (n = 73) had CU symptoms at work, in 69.5% of cases at least several times a week. The occupational impact of CU was assessed by patients with a mean VAS score of 5.5 ± 3 (Table III). CU had a significant impact on work (VAS > 5) in 55.7% of patients, and a major impact (VAS ≥ 7) in 40.9%. Conversely, work aggravated CU in 32.9% (n = 24/73) of patients reporting symptoms at work. Moreover, 18.2% of patients (n = 16) reported adverse effects of their CU treatment occurring at work and impacting it: somnolence, asthenia, dizziness, headaches.

Table III.

Occupational impact of chronic urticaria (n = 88)

| Factor | Total population (n = 88) | Isolated CSU (n = 31) | CSU + CindU (n = 57) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms at work, n (%) | 73 (85.9) | 27 (87.1) | 46 (85.2) | 1.00 |

| Frequency of symptoms at work, n (%) | ||||

| Every day | 30 (34.9) | 11 (35.5) | 19 (33.3) | 0.84 |

| Several times a week | 20 (22.7) | 8 (25.8) | 12 (21.1) | 0.61 |

| Once a week | 6 (6.8) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (5.3) | 0.66 |

| Several times a month | 6 (6.8) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (7.0) | 1.00 |

| Once a month or less | 11 (12.5) | 3 (9.7) | 8 (14.0) | 0.74 |

| Symptoms worsened by work, n (%) | 24 (27.6) | 10 (32.3) | 14 (25.0) | 0.47 |

| VAS assessing the occupational impact of CU, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 3 | 5.9 ± 2.8 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 0.35 |

| VAS > 5, n (%) | 49 (55.7) | 21 (67.8) | 28 (49.1) | 0.09 |

| VAS ≥ 7, n (%) | 36 (40.9) | 13 (41.9) | 23 (10.4) | 0.89 |

| Working conditions affecting CU | ||||

| Role of stress | 9 (10.2) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (5.3) | 0.03 |

| Exposure to extreme temperatures | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 0.54 |

| Physical exertion/sweating | 7 (7.9) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (7.0) | 0.69 |

| (Micro)traumatic work tools | 11 (12.5) | 3 (9.7) | 8 (14.0) | 0.74 |

| Occupational consequences of CU, n (%) | ||||

| RQTH (Recognition of the Status of Disabled Worker) because of CU | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Workstation adjustments | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.54 |

| Occupational reclassification (same company, other workstation) | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 1.00 |

| Change of job or profession | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1.00 |

| Employee did not renew the employment contract | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1.00 |

| Employer did not renew the employment contract | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1.00 |

| Dismissal for medical unfitness | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | |

| Occupational physician was informed about CU, n (%) | 24 (28.6) | 12 (38.7) | 12 (22.7) | 0.12 |

| Employer was informed about CU, n (%) | 34 (40.5) | 12 (38.7) | 22 (41.5) | 0.80 |

| Questions about occupational impact of CU (VAS > 5), n (%) | ||||

| “The adverse effects of my CU treatment affect my work” | 16 (19.1) | 9 (29.0) | 7 (13.2) | 0.07 |

| “I can’t take my CU treatment properly because of my work” | 3 (3.6) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.9) | 1.00 |

| “The symptoms of CU are worsened by my work” | 17 (20.5) | 8 (25.8) | 9 (17.3) | 0.35 |

| “The symptoms of CU make me postpone and/or temporarily interrupt my activity at work” | 14 (16.9) | 6 (19.5) | 8 (15.4) | 0.64 |

| “I’m afraid of losing my job because of my CU” | 10 (11.9) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (13.2) | 0.74 |

| “My CU slows my career development” | 15 (17.9) | 5 (16.1) | 10 (18.9) | 0.75 |

| “Because of CU, I get less satisfaction at work” | 20 (24.1) | 9 (17.3) | 11 (35.5) | 0.06 |

| “My colleagues support me with my CU” | 32 (38.6) | 11 (35.5) | 21 (40.4) | 0.66 |

| “My boss supports me with my CU” | 29 (35.0) | 10 (32.3) | 19 (36.5) | 0.69 |

| “I suffer discrimination at work because of my CU” | 2 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.9) | 1.00 |

| “My CU makes me feel less effective” | 28 (33.7) | 13 (41.9) | 15 (28.8) | 0.22 |

| “I have fewer responsibilities because of my CU” | 4 (4.8) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (5.8) | 1.00 |

| “There are activities at work that I can no longer do because of my CU” | 10 (12.1) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (13.5) | 0.74 |

| WPAI-CU, mean (%) ± SD | ||||

| Absenteeism (n = 72) | 2.7 ± 10.9 | 5.1 ± 15 | 1 ± 6,4 | 0.09 |

| Presenteeism (n = 75) | 23.1 ± 27.7 | 23.3 ± 32.4 | 22.9 ± 24.4 | 0.46 |

| Overall work impairment (n = 72) | 22.9 ± 28.5 | 24.2 ± 33.9 | 22 ± 24.4 | 0.55 |

| Activity impairment (n = 79) | 33.1 ± 30.3 | 27.7 ± 32.9 | 36.3 ± 28.6 | 0.15 |

CU: chronic urticaria; CSU: chronic spontaneous urticaria; CIndU: chronic inducible urticaria; WPAI-CU: Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Chronic Urticaria; SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analogue scale; RQTH: Recognition of the Status of Disabled Worker. p-value, calculated with Fischer or χ2 or Mann–Whitney tests.

Some 22.7% of patients (n = 20) had less job satisfaction as a result of CU, and 31.8% (n = 28) felt less effective at work. Despite low absenteeism, presenteeism and reduced productivity were significant (> 20%) on the WPAI-CU score. In the 49 patients (55.7%) who reported a significant impact of CU on their working life (VAS > 5), the duration of CU was shorter (43.5 months ± 63.4 versus 70.4 months ± 88.1; p = 0. 04), CU control was poorer, quality of life impairment was greater (mean Cu-Q2oL 55.8 ± 21.4 versus 43 ± 12.1, p = 0.005), and presenteeism and impact on activity were greater (Table IV). In multivariate analysis (Fig. 1), adjusted for disease type (i.e. CSU and/or CIndU), duration and control (UCT score), only poor control of CU (low UCT score) was associated with a strong impact on work (odds ratio 1.11 [1.01; 1.24], p = 0.034).

Table IV.

Subjective occupational impact

| Factor | Little or no occupational impact (Visual analogue scale ≤ 5) | Significant occupational impact (Visual analogue scale > 5) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 39 (44.3) | 49 (55.7) | |

| Type of urticaria, n (%) | |||

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | 10 (26.0) | 21 (43.0) | 0.24 |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria | 19 (49.0) | 19 (39.0) | |

| Chronic inducible urticaria | 10 (26.0) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Angioedema, n (%) | 19 (48.7) | 25 (51.2) | 0.83 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 25 (64.1) | 28 (57.1) | 0.51 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 38.7 ± 11.3 | 42.7 ± 13.9 | 0.24 |

| Age at onset (years), mean ± SD | 33.5 ± 12.9 | 39.1 ± 15 | 0.08 |

| Disease duration (months) | 70.4 ± 88.1 | 43.5 ± 63.4 | 0.04 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 24 (61.5) | 32 (65.3) | 0.72 |

| Level of education, n (%) | 0.13 | ||

| No diploma | 4 (10.3) | 12 (24.5) | |

| College | 8 (20.5) | 13 (26.5) | |

| Between college and bachelor’s degree | 6 (15.4) | 7 (14.3) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 8 (20.5) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Master’s degree | 13 (33.3) | 9 (18.4) | |

| Doctorate | 0 | 3 (6.1) | |

| Professional sector of activity (group NAF codes), n (%) | |||

| Construction (F) | 6 (15.4) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Industries (C, D) | 3 (7.7) | 4 (8.2) | |

| Health and social care (Q, S) | 14 (35.9) | 11 (22.5) | |

| Tertiary services (J, K, L, N, O) | 9 (23.1) | 8 (16.3) | |

| Others (A, G, H, I, P, R) | 7 (18) | 20 (40.8) | |

| Socio-professional categories (PSC), n (%) | 0.25 | ||

| Farmers | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2) | |

| Craftsmen, shopkeepers, company directors | 1 (2.6) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Executives, higher intellectual occupations | 12 (30.8) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Intermediate occupation | 9 (23.1) | 9 (18.4) | |

| Employees | 14 (35.9) | 15 (30.6) | |

| Workers | 2 (5.1) | 8 (16.3) | |

| Frequency of sick leave due to chronic urticaria, n | 2 | 11 | 0.10 |

| Cumulative duration of sick leave (days) | 15.5 ± 20.5 | 129.1 ± 341.2 | 0.75 |

| Loss of income due to chronic urticaria, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 6 (12.5) | 0.12 |

| Working with the public, n (%) | 30 (76.9) | 36 (73.5) | 0.71 |

| Physical work, n (%) | 17 (43.6) | 26 (53.1) | 0.38 |

| Work involving fine manual tasks, n (%) | 16 (41.0) | 25 (51.0) | 0.35 |

| Working outdoors, n (%) | 8 (20.5) | 15 (30.6) | 0.28 |

| Urticaria Control Test, mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 4.4 | 6.4 ± 4.6 | 0.03 |

| Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire | 43 ± 12.1 | 55.8 ± 21.4 | 0.005 |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Chronic Urticaria, mean (%) ± SD | |||

| Absenteeism | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 14.7 | 0.06 |

| Presenteeism | 13.3 ± 17.4 | 32.1 ± 32.3 | 0.03 |

| Overall work impairment | 12.6 ± 16.1 | 32.2 ± 33.8 | 0.05 |

| Activity impairment | 24.2 ± 24.1 | 40.3 ± 33.1 | 0.04 |

SD: standard deviation; NAF: French National Classification of Activities (2008); PSC: French Classification of Occupations and Socio-Professional Categories (2020). p-value calculated with Fischer or χ2 or Mann–Whitney tests.

Fig. 1.

Multivariate analysis of the association between a significant occupational impact of chronic urticaria (VAS > 5) and the disease type, control and duration. UCT: Urticaria Control Test; CSU: chronic spontaneous urticaria; CIndU: chronic inducible urticaria.

Almost 15% of patients (n = 13) had at least one absence from work, with a median duration of 8.5 days (range, 4–23.5); 8% of patients reported a loss of income linked to their CU.

Six patients (6.8%) had encountered difficulties in maintaining employment in manual occupations: 3 had undergone a change of position or profession, 3 had had their contract non-renewed or had been dismissed for medical unfitness because of their CU.

Comparative analysis of the isolated CIndU group, the isolated CSU group and the CSU + CIndU group showed no significant differences on self-assessment of the occupational impact of CU (see Table III) or on other data concerning work repercussions (see Table III).

DISCUSSION

The socio-demographic characteristics of our population were comparable to those reported in the literature, with a predominance of middle-aged women, the presence of angioedema in half the patients and an association with atopic or autoimmune comorbidities in two-thirds of cases (18, 19). The most frequent CIndU in descending order were dermographism, delayed pressure urticaria, cholinergic urticaria and cold urticaria. CU was uncontrolled in almost 80% of patients, similar to results in the literature (7, 19, 20). This could reflect under-treatment, as less than a third of the patients (32.5%) were on omalizumab at the time of the questionnaire. Also, 64.8% of the patients had isolated CIndU (n = 19), thus were not eligible for omalizumab, or a combination of CSU + CIndU (n = 38), which could explain a lower response to treatment. This study showed that the subjective and objective occupational impact of CU was significant for a majority of patients. Both univariate and multivariate analyses showed that poor disease control, but not the disease type (i.e. the presence of CIndU) or its duration, influenced the occupational impact of the disease. The WPAI score showed that, despite low absenteeism, presenteeism and reduced productivity were significant (> 20%), in line with the literature and correlated with the UCT score (7, 8, 20–24). These results are comparable to atopic dermatitis, moderate-to-severe psoriasis and severe asthma, but less high than scleroderma or other autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases (20, 22, 25, 26). On the other hand, CIndU, either isolated or combined with CSU, had a similar occupational impact to isolated CSU (p = 0.55). This may reflect the fact that physical triggers are not avoided at work, either because of technical impossibility or because the occupational physician was not informed (71.4% of patients). The occupational physician is frequently not informed, which results in the absence of workstation adjustments and of the supporting aids available; 65% of employees do not know the role of the occupational physician (27). Some of them may be afraid that their occupational physician might make them lose their jobs. Sometimes there is no occupational physician to look after the company (28). It is also possible that avoiding physical triggers does not improve the overall course of CU, or that patients have difficulty individualizing CIndU, as there are no specific questionnaires adapted in French for all forms of CIndU. Among the 24 patients who declared that their CU was aggravated by their working conditions, the role of stress was more important in patients with isolated CSU than when CIndU was present (p = 0.03), but the role of physical triggers (exercise, high or cold ambient temperature, carrying heavy loads, etc.) was not mentioned more by CIndU patients. Nearly 15% of patients in our study had missed at least 1 day of work due to CU, for a median duration of 8.5 days, which is comparable to data in the recent literature, reporting 5.8 and 62.5% of patients missing at least 1 day of work, for a median duration of 0.8 to 26.6 days (5, 7–9).

Difficulties in maintaining employment were highlighted in our study for 6.8% of patients, in a manner comparable to a previous study concerning cutaneous psoriasis, but with a job adaptation rate of 12% (29). The absence of workstation adjustments in our study, while job loss is comparable to the aforementioned psoriasis study, shows that the impact of CU is underestimated by healthcare professionals. Our study thus suggests that physicians should more systematically investigate the occupational impact of CU during a consultation to optimize the quality of life at work and maintain employment.

The major limitations of this study are its cross-sectional nature, which makes it impossible to assess in particular the effect of optimized treatment on quality of life and productivity at work, the monocentric nature of this study in a territory with particular economic features (high rate of unemployment, large number of retired people) and the absence of CIndU specific quality of life questionnaires in French. The exploratory nature of this study also means that these results will need to be replicated in future research.

In conclusion, CU, whether spontaneous and/or inducible, has a considerable impact on productivity and quality of life at work, especially when it is poorly controlled and unrecognized. The question of work should be systematically addressed in CU consultations, particularly in cases of inadequate disease control. Communication with the occupational physician should be systematically proposed. A study evaluating the benefit of optimized treatment of CU (including emerging treatments for CIndU) on quality of life at work and productivity is necessary, with the help of additional specific tools for assessing CIndU impact.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

IRB approval status

Approved IRB-MTP_2021_07_202100903

Conflicts of interest declaration

ADT: principal or sub-investigator, speaker for Novartis. NRP: sub-investigator for Novartis. AB, MNC and CS have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fricke J, Ávila G, Keller T, Weller K, Lau S, Maurer M, et al. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy 2020; 75: 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, Aquilina S, Asero R, Baker D, et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy 2022; 77: 734–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moestrup K, Ghazanfar MN, Thomsen SF. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in chronic urticaria. Int J Dermatol 2017; 56: 1342–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer M, Ortonne JP, Zuberbier T. Chronic urticaria: a patient survey on quality-of-life, treatment usage and doctor–patient relation. Allergy 2009; 64: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonçalo M, Gimenéz-Arnau A, Al-Ahmad M, Ben-Shoshan M, Bernstein JA, Ensina LF, et al. The global burden of chronic urticaria for the patient and society. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer M, Houghton K, Costa C, Dabove F, Ensina LF, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. Differences in chronic spontaneous urticaria between Europe and Central/South America: results of the multi-center real world AWARE study. World Allergy Organ J 2018; 11: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomsen SF, Pritzier EC, Anderson CD, Vaugelade-Baust N, Dodge R, Dahlborn AK, et al. Chronic urticaria in the real-life clinical practice setting in Sweden, Norway and Denmark: baseline results from the non-interventional multicentre AWARE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 1048–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sussman G, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F, Canonica W, Oude Elberink H, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. Angioedema in chronic spontaneous urticaria is underdiagnosed and has a substantial impact: analyses from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy 2018; 73: 1724–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurer M, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F, Canonica W, Oude Elberink H, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: real-world evidence from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy 2017; 72: 2005–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurer M, Metz M, Brehler R, Hillen U, Jakob T, Mahler V, et al. Omalizumab treatment in patients with chronic inducible urticaria: a systematic review of published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 638–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang K, Beaton DE, Boonen A, Gignac MAM, Bombardier C. Measures of work disability and productivity: Rheumatoid Arthritis Specific Work Productivity Survey (WPS-RA), Workplace Activity Limitations Scale (WALS), Work Instability Scale for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA-WIS), Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ), and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63: S337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomas H, Delaubier A. Handicap locomoteur et maintien en emploi: étude rétrospective à propos de 352 salariés reconnus travailleurs handicapés en 2013. Arch Mal Prof Enviro 2021; 82: 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolas A, Launay D, Duprez C, Citerne I, Morell-Dubois S, Sobanski V, et al. Impact de l’angiœdème héréditaire sur les activités de la vie quotidienne, la sphère émotionnelle et la qualité de vie des patients. Rev Med Interne 2021; 42: 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traitement de l’urticaire chronique spontanée – Document de synthèse. 2019. Available from: https://reco.sfdermato.org/fr/recommandations-urticaire-chronique-spontan%C3%A9e/bibliographie.

- 15.Magerl M, Altrichter S, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, Grattan CEH, Lawlor F, et al. The definition, diagnostic testing, and management of chronic inducible urticarias: the EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus recommendations 2016 update and revision. Allergy 2016; 71: 780–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNESCO Institute for Statistics . International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. 2011. Available from: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-fr.pdf.

- 17.INSEE . Nomenclature des professions et catégories socioprofessionnelles (PCS 2020). 2020. Available from: https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/6051913.

- 18.Zuberbier T, Balke M, Worm M, Edenharter G, Maurer M. Epidemiology of urticaria: a representative cross-sectional population survey. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35: 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillet G, Bécherel PA, Pralong P, Delbarre M, Outtas O, Martin L, et al. The burden of chronic urticaria: French baseline data from the international real-life AWARE study. Eur J Dermatol 2019; 29: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itakura A, Tani Y, Kaneko N, Hide M. Impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life and work in Japan: results of a real-world study. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira ARF, Motta AA, Kalil J, Agondi RC. Chronic inducible urticaria: confirmation through challenge tests and response to treatment. Einstein Sao Paulo Braz 2020; 18: eAO5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendelson MH, Bernstein JA, Gabriel S, Balp MM, Tian H, Vietri J, et al. Patient-reported impact of chronic urticaria compared with psoriasis in the United States. J Dermatol Treat 2017; 28: 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balp MM, Khalil S, Tian H, Gabriel S, Vietri J, Zuberbier T. Burden of chronic urticaria relative to psoriasis in five European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson AK, Finn AF, Schoenwetter WF. Effect of 60 mg twice-daily fexofenadine HCl on quality of life, work and classroom productivity, and regular activity in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bérezné A, Seror R, Morell-Dubois S, de Menthon M, Fois E, Dzeing-Ella A, et al. Impact of systemic sclerosis on occupational and professional activity with attention to patients with digital ulcers. Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63: 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Young A, Singh A, Anis AH. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire: general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barotto F, Martin F. Services de santé au travail: qu’en pensent les salariés? Arch Prof Mal Enviro 76: 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peres N, Morell-Dubois S, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Duhamel A, Godard D, et al. Sclérodermie systémique et difficultés professionnelles: résultats d’une enquête prospective. Rev Med Interne 2017; 38: 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maoua M, El Maalel O, Boughattas W, Kalboussi H, Ghariani N, Nouira R. Qualité de vie et activité professionnelle des patients atteints de psoriasis au centre tunisien. 2015; 76: 439–448. [Google Scholar]