Abstract

Background:

Sexual health is critical to overall health, yet sexual history taking is challenging. LGBTQ+ patients face additional barriers due to cis/heteronormativity from the medical system. We aimed to develop and pilot test a novel sexual history questionnaire called the Sexual Health Intake (SHI) form for patients of diverse genders and sexualities.

Methods:

The SHI comprises four pictogram-based questions about sexual contact at the mouth, anus, vaginal canal, and penis. We enrolled 100 sexually active, English-speaking adults from a gender-affirming surgery clinic and urology clinic from November 2022 to April 2023. All surveys were completed in the office. Patients also answered five feedback questions and 15 questions from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction (PROMIS-SexFS) survey as a validated comparator.

Results:

One hundred patients aged 19–86 years representing an array of racial/ethnic groups, gender identities, and sexuality completed the study. Forms of sexual contact varied widely and included all possible combinations asked by the SHI. Feedback questions were answered favorably in domains of clinical utility, inclusiveness of identity and anatomy, and comprehensiveness of forms of sexual behavior. The SHI captured more positive responses than PROMIS-SexFS in corresponding questions about specific types of sexual activity. The SHI also asks about forms of sexual contact that are not addressed by PROMIS-SexFS, such as penis-to-clitoris.

Conclusions:

SHI is an inclusive, patient-directed tool to aid sexual history taking without cisnormative or heteronormative biases. The form was well received by a diverse group of participants and can be considered for use in the clinical setting.

Takeaways

Question: Can we develop and test a more inclusive sexual history intake survey for patients of diverse genders and sexualities?

Findings: One hundred sexually active adult patients completed the Sexual Health Intake (SHI) form in clinic and rated it favorably in clinical utility, inclusiveness of identity and anatomy, and comprehensiveness of forms of sexual behavior.

Meaning: In this pilot study, a diverse group of participants completed the SHI with minimal guidance and rated it highly. The SHI captured more positive responses than PROMIS-SexFS, an existing validated sexual activity survey, and asked about forms of sexual contact not addressed by PROMIS-SexFS.

INTRODUCTION

Sexual health is critical to overall health, but sexual history taking can be a challenging experience for both patients and providers. Although patients may feel uneasy addressing their sexual activities in a clinical setting,1 providers report inadequate training, time constraints, and their own lack of comfort or embarrassment as potential barriers, among many others.2–6 Obtaining a sexual history can facilitate conversations about safe sex practices, sexually transmitted infections, contraception and family planning, and sexual well-being and sex-related quality of life.7–9 Yet, studies indicate that the majority of providers do not routinely ask patients about their sexual history.9 Perhaps even more tellingly, a large international study showed that while half of sexually active individuals had at least one sexual problem, only 19% sought medical care, and even worse, only 9% were asked about sexual health in the last 3 years.10

Gaps in assessing sexual history are further exacerbated in LGBTQ+ patients who already experience numerous barriers to equitable, culturally competent care.11 Providers report even less comfort when discussing sexual health with LGBTQ+ patients compared with patients who are heterosexual, cisgender, or participating primarily in penile-vaginal sexual intercourse.5,12 Cultural cisnormativity and heteronormativity may lead many providers to assume similar sexual preferences and practices among patients of various gender identities and sexual orientations, ultimately resulting in patient unease and missed care opportunities.13–15

There have been previous efforts to improve provider and trainee sexual history taking skills in general1,9 and for LGBTQ+ patients specifically.5,8 One adjunctive approach would be to use a standardized sexual history intake form that patients can complete before clinic visits along with the rest of their medical history, as is commonplace in many outpatient offices. Such a form could give providers a starting point from which to draw clinical information and initiate the conversation. To the best of our knowledge, however, there is no currently available history-taking aide that addresses sexual activities without assuming that genital anatomy matches sex or gender of record, or that conscientiously avoids cisnormative and heteronormative biases. The objective of this study was to pilot test a novel, clinically useful sexual history questionnaire called the Sexual Health Intake (SHI) form for patients of all genders and sexualities. We aimed to ask patients primarily about the uses of their current genitalia for sexual activity and associated sexual satisfaction from an open-ended, unbiased perspective, in addition to soliciting patient feedback on the questionnaire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the New York University (NYU) Langone institutional review board (s21-00642). We followed the SQUIRE 2.0 standards for healthcare quality improvement reporting,16 as our goal was to test a more comprehensive, gender-conscious method of assessing sexual history during the medical intake process. Before pilot testing, a multidisciplinary, gender identity–diverse team comprising urology and plastic surgery faculty and resident trainees who perform gender-affirming surgery and research personnel from the gender-affirming surgery program at NYU Langone developed the SHI questionnaire. Our pilot sites were a gender-affirming surgery clinic and an adult urology clinic at NYU Langone.

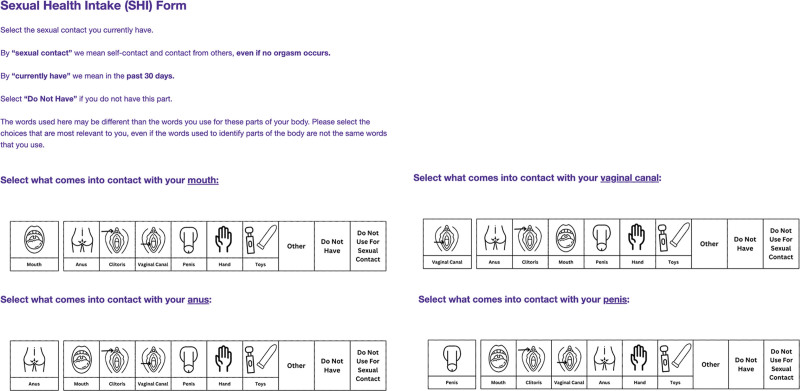

The SHI consists of four open-ended, pictogram-based questions about sexual contact in the last 30 days, each addressing one index body part belonging to the patient: mouth, anus, vaginal canal, and penis. We selected these four body parts not only because they are frequently used in sexual activities, but because they are potential routes of STI transmission. For each index body part, other body parts in addition to “toys” can be selected if they come into contact with the index body part in a sexual manner, in addition to options for “other” (type in), “do not have index body part,” and “do not use index body part for sexual contact.” Figure 1 illustrates the instructions and the four primary questions of SHI. For each index body part, the SHI also asks about satisfaction with sexual contact on a scale of 1–5.

Fig. 1.

SHI form (as it appears for patients).

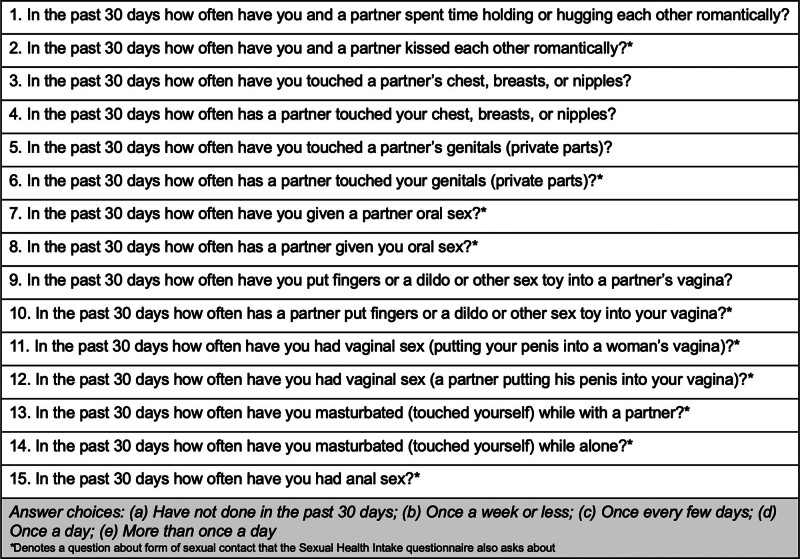

For this pilot phase, the SHI was only created in English and uploaded to Qualtrics for completion on an iPad. After the SHI questions, patients were automatically taken to three additional question sections. First, the form asked patients a series of five specific feedback questions regarding their opinion of the SHI, and were provided an open-response field to provide any additional feedback. Second, to compare SHI results against an existing validated questionnaire, 15 relevant questions from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction (PROMIS-SexFS) survey were also included: three sexual function screening questions and 12 sexual activities questions,17,18 as shown in Figure 2. Importantly, PROMIS-SexFS also asks about sexual activities in the last 30 days. Third, the form asked a comprehensive series of questions about patient demographic information, including age, race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and history of gender-affirming surgery and hormonal therapies. We used a two-step gender assessment method, asking about both assigned sex at birth and current gender identity.19

Fig. 2.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction questions.

In-person enrollment and SHI questionnaire completion were performed from November 8, 2022 to April 11, 2023. We recruited adult patients 18 years or older from all racial and ethnic origins, gender identities, and sexual orientations physically seen at the NYU Langone gender-affirming surgery clinic and an adult urology clinic as part of their standard clinical follow-up. Patients who were not sexually active, unable to read in English, being seen for new encounters, or presenting with acute issues were not eligible for this study. Participants were directly identified by LCZ in clinic based on the aforementioned criteria, and the study was discussed with the patient. We enrolled patients until a total of 100 participants completed the questionnaire.

Interested patients were directed to TRZ or CDR either before or after their clinic visits, who explained the key information form and obtained electronic signed informed consent, which was collected via REDCap. During the enrollment process, participants were each offered a $25 gift card for their time and involvement. Upon signing of the electronic consent form, participants were routed directly to the anonymous study questionnaire in Qualtrics, the results of which were not linked to the REDCap record. Study personnel explained how to interface with the questionnaire on an iPad and remained available to answer questions throughout the duration of the completion of the questionnaire. The majority of patients completed the survey in less than 10 minutes, and median completion time was 9 minutes and 51 seconds (though these times include the feedback and PROMIS-SexFS questions, which would not be asked in a standalone SHI form).

At the end of the study period, descriptive statistics were performed for the questionnaire results and study population demographics. Next, a matrix was created containing all forms of possible sexual contact asked about by SHI and corresponding PROMIS-SexFS questions, when available. For each type of sexual contact that was covered by both SHI and PROMIS-SexFS, we compared the number of patients that responded to both questionnaires. Finally, we assessed the types of sexual contact uniquely asked about by SHI and the number of patients reporting to demonstrate types of sexual activity that PROMIS-SexFS fails to capture.

RESULTS

One hundred patients completed the SHI questionnaire, ranging in age from 19 to 86 years, with a mean age of 41.9 years [SD 17.4]. Table 1 summarizes the study participant characteristics. The majority were 35 years old or younger (53%). About two-thirds identified as White. The cohort was diverse in terms of gender identity and sexuality, and participants could select as many as applied for both categories. The most frequently selected gender identities were “man” (40%), “woman” (35%), “transgender woman” (28%), and “transgender man” (11%). The most frequently selected sexualities were “straight” (61%), “queer” (15%), “bisexual” (14%), and “pansexual” (14%). Half of participants had undergone any form of gender-affirming surgery; one-third had vaginoplasty, 16% phalloplasty, and 1% metoidioplasty.

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics

| n = 100 | No. = % |

|---|---|

| Age (y), mean [SD, range] | 41.9 [17.4, 19–86] |

| 19–25 | 19 |

| 26–35 | 34 |

| 36–45 | 10 |

| 46–55 | 9 |

| 56–65 | 11 |

| 66–75 | 14 |

| 76+ | 3 |

| Race/ethnicity* | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 |

| Black | 10 |

| White | 68 |

| Hispanic | 21 |

| Other/choose not to disclose | 19 |

| Gender* | |

| Man | 40 |

| Woman | 35 |

| Cisgender man | 0 |

| Cisgender woman | 1 |

| Transgender man | 11 |

| Transgender woman | 28 |

| Transmasculine | 2 |

| Transfeminine | 6 |

| Nonbinary | 6 |

| Agender | 1 |

| Gender queer/gender nonconforming | 6 |

| Other/choose not to disclose | 0 |

| Sexuality* | |

| Straight | 61 |

| Gay | 8 |

| Lesbian | 8 |

| Bisexual | 14 |

| Pansexual | 14 |

| Queer | 15 |

| Asexual | 0 |

| Other/choose not to disclose | 2 |

| Gender-affirming surgical history* | |

| Vaginoplasty | 33 |

| Phalloplasty | 16 |

| Metoidioplasty | 1 |

| None | 50 |

| Currently taking hormonal therapy* | |

| Yes, testosterone | 19 |

| Yes, estrogen | 35 |

| Yes, progesterone | 15 |

| Yes, other | 5 |

| No | 45 |

Participants selected all that applied.

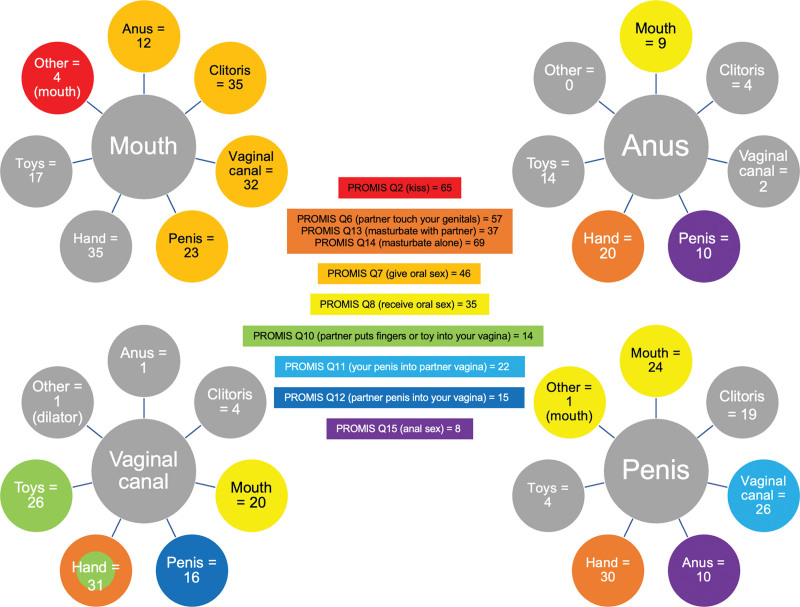

Forms of sexual activity were varied and included all possible combinations of index body parts and selectable body parts or objects on the SHI form. Figure 3 illustrates the four index body parts of SHI (mouth, anus, vaginal canal, penis) linked with each of the possible corresponding sexual contact options. Only the index body part necessarily belongs to the participant. For example, 31 participants indicated that their vaginal canal came into contact with a hand in a sexual manner, but the hand may have been their own or belonging to someone else. For sexual contact combinations that had a corresponding PROMIS-SexFS question, these were color-coded with the matching question. For example, pictured in light orange is PROMIS-SexFS question 7 (Q7), which asks how often a respondent “gives oral sex,” for which 46 participants answered positively (eg, any frequency other than “none”). The corresponding SHI responses are also pictured in light orange: mouth-to-anus (12 participants), mouth-to-clitoris (35), mouth-to-vaginal canal (32), and mouth-to-penis (23). The vaginal canal-to-hand response is both orange and green because it is possible that combination corresponds to multiple PROMIS-SexFS questions. SHI combinations that did not have a corresponding PROMIS-SexFS question are gray, and include vaginal canal-to-clitoris (four participants), anus-to-toy (14), and penis-to-clitoris (19).

Fig. 3.

SHI sexual contact responses (circles) and corresponding Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction responses (center).

When asked about sexual satisfaction at each index body part, participants generally reported being neutral to somewhat satisfied (Table 2). On a scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), mean scores ranged from 3.65 [SD 1.24] at the anus to 4.08 [SD 1.11] at the vaginal canal. When asked for feedback about the SHI form, responses were favorable (Table 3). On a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants answered positively in five questions about clinical usefulness (4.57 [SD 0.71]), inclusiveness of identity and anatomy (4.60 [SD 0.76]), and comprehensiveness of forms of sexual behavior (4.08 [SD 1.15]). In an open-response section, one patient suggested including “mouth” and “nipple,” whereas another suggested including “thigh.”

Table 2.

SHI Form Satisfaction Question Responses

| Mean Score* [SD] | |

|---|---|

| 1. Mouth | 3.68 [1.28] |

| 2. Anus | 3.65 [1.24] |

| 3. Vaginal canal | 4.08 [1.11] |

| 4. Penis | 3.70 [1.17] |

1 = very unsatisfied; 2 = somewhat unsatisfied; 3 = neutral; 4 = somewhat satisfied; 5 = very satisfied.

Table 3.

SHI Form Feedback Question Responses

| Mean Score* [SD] | |

|---|---|

| 1. I found the SHI form helpful to communicate with my healthcare professional | 4.33 [0.86] |

| 2. The SHI form was inclusive of my identity/anatomy | 4.60 [0.76] |

| 3. The SHI form entailed all forms of sexual behavior | 4.08 [1.15] |

| 4. The SHI form did not offend me | 4.79 [0.74] |

| 5. The SHI form would be useful again in a clinical setting | 4.57 [0.71] |

1 = strongly disagree; 2 = somewhat disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = somewhat agree; 5 = strongly agree.

DISCUSSION

The SHI questionnaire was developed to facilitate better understanding of current sexual practices of patients while reducing clinician assumptions and biases about patient sexual preferences and behaviors. In this real-world pilot test study, 100 participants with diversity in age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexuality found the SHI helpful for patient–provider communication and in clinical scenarios, and that it was inclusive, nonoffensive, and entailed many forms of sexual activity. All participants were able to complete the full questionnaire with minimal guidance from study personnel, with their responses offering different and additional insights into their sexual history compared with PROMIS-SexFS.

Several salient differences in participant responses between SHI and PROMIS-SexFS deserve further discussion. First, many types of sexual contact asked about by both SHI and PROMIS-SexFS in different ways ultimately had more positive responses via SHI, suggesting it is a more sensitive questionnaire capable of casting a wider net and picking up more positive responses. One possible explanation is that the SHI asks in a nondiscriminate fashion about “whether A comes into contact with B,” rather than naming forms of contact with labels such as “oral sex” (PROMIS-SexFS Q7–8) or “vaginal sex” (Q11–12). Patients may not necessarily have the same names (or any at all) for different types of sexual activity, thus limiting their responses to certain PROMIS-SexFS questions. For example, 35 participants answered positively on PROMIS-SexFS that they “receive oral sex” (Q8), compared with 54 participants on SHI (20 vaginal canal-to-mouth, 25 penis-to-mouth, nine anus-to-mouth). A similar observation is made with the PROMIS-SexFS question on “giving oral sex” (Q7), resulting in 45 responses versus 102 distinct answers on SHI: 12 mouth-to-anus, 35 mouth-to-clitoris, 32 mouth-to-vaginal canal, and 23 mouth-to-penis.

Second, on sexual contact with seemingly direct corresponding questions between PROMIS-SexFS and SHI, the latter again records higher positive respondents: 22 on “your penis into partner vagina” (Q11) compared with 26 penis-to-vaginal canal on SHI, and 15 on “partner penis into your vagina” (Q12) compared with 16 on vaginal canal-to-penis on SHI. Although we may not know the exact reasons for these differences, a potential explanation is the use of the word “partner,” which may imply a relationship with another person beyond a sexual interaction that not all respondents identify with. The only major question that PROMIS-SexFS generated a higher number of responses for was “kissing” (Q2), 65 compared with only four in SHI, though SHI does not directly ask about kissing and it was typed in under “other” by some respondents. This finding may be due to the fact that PROMIS-SexFS asks about kissing a partner “romantically,” as opposed to the SHI explicitly framing contact as “sexual” acts, for which participants may not readily think to fill in with “kissing” when mouth-to-mouth contact was not an explicit option to select.

Third, there are a number of SHI sexual contact questions that are not addressed by PROMIS-SexFS, including vaginal canal-to-clitoris and penis-to-clitoris as forms of overlooked sexual activities. Not only is the inability to indicate those sexual activities a missed opportunity in history taking, but their absence may also signal to patients that only certain forms of sexual activity are considered “normal” or important. On the other hand, PROMIS-SexFS questions that the SHI does not address are about forms of nongenital contact such as “holding or hugging” (Q1) and touching the chest or breast (Q3–4), and participant hand-to-partner genitalia contact (Q5 and Q9). Although future iterations of SHI can be expanded, we wanted to focus primarily on areas of potential STI transmission and sexual satisfaction in the participant, not sexual partners.

Taking the previous factors together, in addition to the fact that SHI asks about sexual satisfaction at different parts of the body, we believe it represents a useful addition to existing ways of assessing sexual history. Former efforts on improving sexual history taking—including in the LGBTQ+ patient population—have focused primarily on provider education via standardized patient encounters, implicit bias training, and other didactic strategies,5,8,9 whereas SHI offers a complementary approach to supplement good provider history taking skills with a standardized, patient-directed, and nongender-or-sexuality-biased format that can serve as a baseline screening tool. Ultimately, we hope that SHI can be integrated into clinical practice for providers in relevant specialties such as primary care, family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, urology, plastic and gender-affirming surgery, and sexual medicine to improve dialogue and understanding about sexual activities with their patients. We also envision that sexual history taking becomes much more standardized and normalized through the deployment of forms such as SHI for all patients, but especially for LGBTQ+ patients.

Of course, clinical implementation can often be challenging. During this pilot phase, the SHI workflow did not seem to interrupt patient care as the form was deployed after check-in while the patient was waiting to be seen, much like a basic medical history form is filled out just before new patient visits. Our clinic had iPads readily available, but the form could also be completed on paper in settings without access to iPads or computers. Indeed, previous work on implementation of gender-affirming patient-reported outcome measures indicated that varied engagement formats (online or in-person) and shorter forms facilitate real-life use.20 The SHI could also be provided via an electronic link for patients to fill out on their own time. Ideally, whether completed online or in person, the data would be uploaded into the medical record.

Limitations to this pilot study include its testing in two clinics at one hospital system, which may reduce generalizability, though the overall cohort is quite diverse. Some may argue that the high percentage of LGBTQ+ patients limits the generalizability of our findings; however, we believe that including as many gender-and-sexuality-diverse voices is not only beneficial but crucial, given how little input previous “standard” sexual history questionnaires solicited from LGBTQ+ patients. Next, the patient enrollment process was also not completely free of selection bias, as providers identified potential participants during clinic visits, rather than relying on a system where all patients were offered an opportunity to enroll, or patients were randomly selected. The form was also only available in English and required completion on an iPad, which not all patients may be familiar with, though we intend on making the form available in multiple languages and on paper, maintaining the use of pictograms to facilitate understanding. Of note, the SHI form asked about many forms of sexual activity but still did not and could not cover all forms. Notably, the index body parts were not additionally included in the other body parts listed, which may result in a lack of inclusion of sexual activities if patients do not write in these activities (eg, penis-to-penis or clitoris-to-clitoris). A key next step should be to involve gender-diverse patients in refining and/or adding relevant body parts to reflect a wider range of sexual activities, and perhaps a modified Delphi process21 involving clinicians, researchers, and patients to ensure the final iteration of SHI captures sexual history information in the most complete and accurate way. Finally, although we compared SHI against PROMIS-SexFS, psychometric testing to assess validity22 was not within the scope of this study, and will be an important future step.

CONCLUSIONS

SHI is an inclusive, patient-directed tool to aid in sexual history taking. It covers a broad range of sexual activities without capitulating to cisnormativity or heteronormativity, which may exist in other questionnaires or provider biases. The form was well received by a diverse group of participants and can be considered for integration into clinical workflows in multiple specialties pending further validation studies.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. Part of this study was completed with a grant from the French Foundation.

Footnotes

Published online 5 April 2024.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Althof SE, Rosen RC, Perelman MA, et al. Standard operating procedures for taking a sexual history. J Sex Med. 2013;10:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsimtsiou Z, Hatzmouratidis K, Nakopoulou E, et al. Predictor of physicians’ involvement in addressing sexual health issues. J Sex Med. 2006;3:583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morand A, McLeod S, Lim R. Barriers to sexual history taking in adolescent girls with abdominal pain in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes V, Blondeau W, Bing-You RG. Assessment of medical student and resident/fellow knowledge, comfort, and training with sexual history taking in LGBTQ patients. Fam Med. 2015;47:383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonardi-Warren K, Neff I, Mancuso M, et al. Sexual health: exploring patient needs and healthcare provider comfort and knowledge. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:E162–E167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, et al. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of United States obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayfield JJ, Ball EM, Tillery KA, et al. Beyond men, women, or both: a comprehensive, LGBTQ-inclusive, implicit-bias-aware, standardized-patient-based sexual history taking curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin ES, Rullo J, Tsai P, et al. Best practices in North American pre-clinical medical education in sexual history taking: consensus from the Summits in Medical Education in Sexual Health. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1414–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreira E, Brock G, Glasser A, et al. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waryold JM, Kornahrens A. Decreasing barriers to sexual health in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community. Nurs Clin North Am. 2020;55:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine DA, Adolescence CO. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e297–e313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, et al. “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J Assoc Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20:348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:S1–S259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brookmeyer KA, Coor A, Kachur RE, et al. Sexual history taking in clinical settings: a narrative review. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Quality Safety. 2016;25:986–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS sexual function and satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures user manual. Available at https://assessmentcenter.net/documents/Sexual%20Function%20Manual.pdf. Published July 8, 2015. Accessed July 8, 2023.

- 19.Lagos D, Compton D. Evaluating the use of a two-step gender identity measure in the 2018 General Social Survey. Demography. 2021;58:763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamran R, Jackman L, Chan C, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcome measures for gender-affirming care worldwide: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e236425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11:116–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]