Abstract

Purpose:

Speech motor control changes underlying louder speech are poorly understood in children with cerebral palsy (CP). The current study evaluates changes in the oral articulatory and laryngeal subsystems in children with CP and their typically developing (TD) peers during louder speech.

Method:

Nine children with CP and nine age- and sex-matched TD peers produced sentence repetitions in two conditions: (a) with their habitual rate and loudness and (b) with louder speech. Lip and jaw movements were recorded with optical motion capture. Acoustic recordings were obtained to evaluate vocal fold articulation.

Results:

Children with CP had smaller jaw movements, larger lower lip movements, slower jaw speeds, faster lip speeds, reduced interarticulator coordination, reduced low-frequency spectral tilt, and lower cepstral peak prominences (CPP) in comparison to their TD peers. Both groups produced louder speech with larger lip and jaw movements, faster lip and jaw speeds, increased temporal coordination, reduced movement variability, reduced spectral tilt, and increased CPP.

Conclusions:

Children with CP differ from their TD peers in the speech motor control of both the oral articulatory and laryngeal subsystems. Both groups alter oral articulatory and vocal fold movements when cued to speak loudly, which may contribute to the increased intelligibility associated with louder speech.

Supplemental Material:

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by central nervous system differences that can result in movement, sensory, communication, and/or cognitive impairments (Rosenbaum et al., 2007). Prevalence studies of dysarthria in children with CP indicate that approximately more than 50% of children with CP have dysarthria (Himmelmann & Uvebrant, 2011; Nordberg et al., 2013; Parkes et al., 2010). Those with dysarthria secondary to CP have reduced intelligibility (e.g., Allison & Hustad, 2014; Ansel & Kent, 1992; Hodge & Gotzke, 2014; Hustad et al., 2012; Nip, 2017), increased number of consonant production errors (Nordberg et al., 2014), and increased number of phonetic contrast errors (Ansel & Kent, 1992; Whitehill & Ciocca, 2000). The most likely reason for the impaired intelligibility is the impaired speech motor control in this population (Hustad et al., 2012; Nip, 2017), rather than audibility or linguistic task demands, though those and other variables may also play a role (Hustad et al., 2012).

Reduced intelligibility in this group may be due to differences in the speech motor control of multiple subsystems, such as reduced loudness (e.g., Workinger & Kent, 1991) and/or imprecise articulation (e.g., Ansel & Kent, 1992). In the oral articulatory subsystem, these individuals speak with greater excursions and faster speeds of the oral articulators (Hong et al., 2011; Nip, 2013; Nip et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2013). Children with CP also produce speech with reduced interarticulator coordination, which is highly correlated with increased dysarthria severity, as indexed by intelligibility (Nip, 2017). Many children with dysarthria secondary to CP also have speech characteristics related to impaired laryngeal control, including changes in voice quality (Allison & Hustad, 2018; Nip & Garellek, 2021), reduced prosodic control (Patel, 2002, 2003), and reduced loudness (Workinger & Kent, 1991). Voice quality changes may be used to distinguish children with dysarthria secondary to CP from typically developing (TD) peers (Allison & Hustad, 2018; Nip & Garellek, 2021). Children with CP have reduced spectral tilt and CPP when compared to TD children, which may account for, in part, the more constricted and creaky voice quality in this group (Nip & Garellek, 2021). Furthermore, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the presentation of the speech impairments for this population (e.g., Hustad et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014). For example, some children may demonstrate a greater degree of impairment in the articulatory subsystem as compared to the laryngeal subsystem. For these children, intelligibility may be impacted more by supraglottal movements (Lee et al., 2014; Whitehill & Ciocca, 2000).

Articulatory and Laryngeal Changes Due to Louder Speech Are Not Fully Understood

Strategies, such as loudness manipulations, can improve the intelligibility of people with dysarthria (Langlois et al., 2020; Spencer et al., 2003; Tjaden et al., 2013; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004; Yorkston, Hakel, et al., 2007; Yorkston et al., 2003). Loudness can be a feasible treatment target for children with dysarthria secondary to CP because of their relatively preserved ability to manipulate loudness (Patel, 2003). Increasing loudness is an important component for various published treatment studies in children with dysarthria secondary to CP, including Lee Silverman Voice Treatment Loud (LSVT-LOUD; Boliek & Fox, 2017; Fox & Boliek, 2012), the subsystem approach (Pennington et al., 2006, 2010, 2013), and the Speech Intelligibility Treatment (Levy et al., 2021; Moya-Galé et al., 2021). Prior small studies have demonstrated that increasing loudness improves speech production and functional communication (Boliek & Fox, 2017; Fox & Boliek, 2012; Levy, 2014) and intelligibility (Langlois et al., 2020) in children with CP.

Despite the use of loudness interventions to improve speech intelligibility in this population, there is little understanding about the speech motor control changes associated with loudness adjustments for TD children or children with CP. Findings from studies examining the association between loudness intervention and speech intelligibility are somewhat mixed. For example, although Langlois et al. (2020) found that children with dysarthria secondary to CP increased in both vocal loudness and intelligibility after an intervention focusing on healthy vocal loudness (LSVT-LOUD), Pennington et al. (2018) found that small vocal intensity and fundamental frequency decreases were associated with speech intelligibility increases after a treatment that focused on improving respiration, phonation, and rate. In contrast, Levy et al. (2021) observed that intelligibility, as measured via ratings of ease of understanding, improved whereas vocal intensity did not after an intervention that included a focus on increasing loudness. Explicating the mechanism of change is required for behavioral treatments to maximize effectiveness (Van Stan et al., 2019, 2021). For example, understanding this mechanism of change could provide the basis for testable hypotheses as to why some children with dysarthria secondary to CP demonstrate stronger responses (e.g., a large gain in intelligibility) compared to others who demonstrate a much weaker response to treatment (Fox & Boliek, 2012; Levy, 2014; Pennington et al., 2010). Potentially, obtaining information on profiles of children who may respond best to a given intervention would allow clinicians to better match an intervention or intervention target (e.g., louder speech vs. slow speech) to a specific child.

Respiratory and laryngeal adjustments are responsible for louder speech (Neel, 2009; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004), which can increase the audibility of the speech signal (Neel, 2009). However, audibility does not fully account for the improved speech intelligibility on its own (Neel, 2009; Pittman & Wiley, 2001). Healthy adult talkers produce articulatory adjustments beyond increasing vocal intensity, which can improve listeners' word recognition even after controlling for the vocal intensity increases (Pittman & Wiley, 2001). Evidence that children with CP may also make articulatory adjustments beyond increasing vocal intensity when talking more loudly comes from treatment studies that demonstrate improved listener ratings of articulatory precision (Boliek & Fox, 2017), suggesting that louder speech may affect oral articulatory control in these children, though this has yet to be directly quantified with kinematic recordings.

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed as potential reasons for why speech production and intelligibility may improve with louder speech, beyond increased audibility. One hypothesis is that the increased effort that talkers use to make laryngeal and respiratory adjustments when talking loudly may spread to other parts of the vocal tract (Rosenbek & LaPointe, 1985; Sapir et al., 2011; Tjaden et al., 2013), contributing to greater articulatory effort. Others have suggested that improvements in vocal fold movements might impact intelligibility because it would improve the vocal sound source required for many speech sounds (Ramig, 1992).

Speech Motor Control Changes in Children With CP When Cued to Speak Loudly

Studies that have explored speech changes as a result of cueing, or in response to instruction rather than more long-term treatment, have demonstrated that children with CP can change their speech when asked to produce behavioral modifications, such as slow speech (e.g., Sakash et al., 2020) or louder speech (Levy et al., 2020). When cued to produce louder speech, children with CP increase their vocal intensity (Levy et al., 2020) and increase F1 for vowels, suggesting that louder speech is produced with larger oral movements, particularly in the vertical plane (Levy et al., 2020).

No known study has directly evaluated how oral movements in children with and without CP change when they are asked to produce louder speech, though studies of loudness manipulations in other groups could inform hypotheses of how these children may change their speech motor control in response to being cued to speak more loudly. Louder speech is characterized by greater displacements of the lips, jaw, and tongue of healthy adults and people with Parkinson's disease (PD; Darling & Huber, 2011; Goozee et al., 2011; Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Mefferd & Green, 2010). The observed increased displacements during louder speech have led researchers to suggest that louder speech is produced with increased articulatory specification through the use of hyperarticulation (Lindblom, 1990). When talkers produce louder speech, presumably the reason for the increased loudness is to increase the likelihood that the intended message is understood by a listener. Therefore, louder speech may be one strategy to increase the distinctiveness of individual words and sounds, or hyperarticulate. Increasing articulatory displacements is one way to ensure this articulatory distinctiveness, which is required for highly intelligible speech (Mefferd, 2017; Mefferd & Green, 2010). Support for this hypothesis also includes findings that acoustic vowel space increases with louder speech, implying an increase in articulatory distinctiveness (Tjaden & Wilding, 2004; Tjaden et al., 2013).

Movement variability and coordination have also been investigated to determine how this task might affect articulatory specification during louder speech. Increased movement variability has been hypothesized to increase phonetic variability (Mefferd & Green, 2010) and to reflect an increase in motor programming demands (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006). Evaluation of movement variability in previous studies of adults producing louder speech has primarily used two different measures: the spatiotemporal index (STI; Smith et al., 1995), which examines the trial-to-trial variability of movement patterns for a specific articulator, and the closely related lip aperture variability index (LAVI; Smith & Zelaznik, 2004), which examines the intertrial variability of the coordination for the two lips. Movement variability has been shown to decrease with louder speech in healthy adults in some studies (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Mefferd & Green, 2010), suggesting that louder speech increases articulatory consistency and precision (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Mefferd & Green, 2010). Other studies, however, have demonstrated no difference in movement variability between habitual and louder speech (Goozee et al., 2011; Kleinow et al., 2001). The variability of lip coordination, as measured by the LAVI, can be used to distinguish adults with hypokinetic dysarthria secondary to PD and healthy adults, though no change was observed in this measure between loudness conditions (Darling & Huber, 2011).

Similarly, interarticulator coordination of speech movements can differentiate children with CP and TD children (Nip, 2017). Particularly, decreased spatial coordination (i.e., whether both lips move apart during opening) and temporal coordination (i.e., whether both lips begin to move apart at the same time) for the upper and lower lip are strongly associated with increased severity of the speech disorder during habitual speech (Nip, 2017). If loudness training (e.g., LSVT-LOUD) can reduce the severity of the dysarthria (e.g., Boliek & Fox, 2017), perhaps interarticulator coordination similarly increases in children with CP when they produce louder speech.

Changes in vocal fold articulation may also contribute to the improved intelligibility associated with louder speech, because this change would improve the vocal sound source (Ramig, 1992). For example, after treatment focusing on respiration, phonation, and rate, improvements in listener ratings of voice quality severity and weakness were associated with speech intelligibility gains for children with dysarthria secondary to CP (Miller et al., 2013). Despite the acknowledgement that louder speech is, at least partially, produced through laryngeal adjustments (Neel, 2009; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004), few studies have examined how louder speech affects vocal fold adjustments and vibratory patterns.

Two variables related to vocal fold vibratory patterns that may change in response to being asked to speak more loudly are spectral tilt and CPP, which may also distinguish children with CP from their TD peers during the production of habitual speech (Nip & Garellek, 2021). Spectral tilt refers to the change in energy between harmonics within the acoustic signal, and children with CP have reduced spectral tilt in comparison to TD children (Nip & Garellek, 2021). The reduced energy at higher harmonics, as reflected by the reduced spectral tilt, suggests that children with CP have less vocal fold contact (Zhang, 2016), less regular vocal fold vibrations (Hanson et al., 2001), and possibly the presence of a posterior opening of the glottis during voicing (Hanson et al., 2001). In terms of speaking more loudly, previous studies have shown that louder speech is produced with reduced spectral tilt in adults (e.g., Lu & Cooke, 2008) and children (Hazan et al., 2016), though this has not yet been examined in children with CP. Reducing or flattening spectral tilt provides increased acoustic energy at higher frequencies, which is associated with healthy listeners' increased accuracy of key word identification, suggesting that this change may contribute to intelligibility gains (Lu & Cooke, 2009).

Children with CP also have reduced CPP values when compared to their TD peers (Nip & Garellek, 2021). CPP is a harmonic-to-noise measure that indicates the degree of aperiodic noise that is produced during vocal fold vibration (Garellek, 2019). The reduced CPP may reflect that children with CP have more noisy and irregular vocal fold vibrations (Garellek, 2019; Samlan & Kreiman, 2014; Zhang et al., 2013). CPP also increases when healthy adults are asked to speak more loudly, indicating that the acoustic energy for harmonics in the speech signal is increased during louder speech (Brockmann-Bauser et al., 2021). Potentially, spectral tilt may decrease and CPP may increase when children with CP and their TD peers speak more loudly.

Rationale

Loudness is a commonly used target in speech intelligibility intervention research in children with dysarthria secondary to CP (e.g., Boliek & Fox, 2017; Fox & Boliek, 2012; Langlois et al., 2020; Levy et al., 2021). Intelligibility gains with louder speech cannot be explained entirely by the increase in audibility of the utterances (Neel, 2009); therefore, there are likely changes with louder speech in both the oral articulatory and laryngeal subsystems. A better understanding of the speech motor control changes associated with louder speech in this population may assist clinicians and researchers to predict an individual client's response to these loudness interventions.

The current cueing study attempts to identify how louder speech affects oral articulatory and vocal fold movements and movement patterns in children with CP and their TD peers. It is hypothesized that children with CP and their TD peers will have less variable movement patterns (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Mefferd & Green, 2010), increased interarticulator coordination, greater articulatory excursions, and greater speeds (Darling & Huber, 2011; Goozee et al., 2011; Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Levy et al., 2020; Mefferd & Green, 2010) in louder speech as compared to habitual speech for the lips and jaw. In regard to the measures of vocal fold articulation, it is hypothesized that both groups will reduce their spectral tilt (Lu & Cooke, 2008) and increase CPP (Brockmann-Bauser et al., 2021) during louder speech relative to habitual speech.

Method

Participants

Institutional review board approval for the study was obtained from San Diego State University. Participants were part of a larger study, and many (n = 16) were included in previously reported data sets (Nip, 2017; Nip & Garellek, 2021). The Nip (2017) study included the analyses of a single bilabial and closing gesture from the sentence, “Buy Bobby a puppy,” produced in the habitual condition (see below) rather than the entire sentence, which is the unit analyzed for the current study. The vowels reported by Nip and Garellek (2021) were from vowel singletons and from a story retell task, rather than from sentence repetitions. Therefore, although data from most of the study's participants have been reported elsewhere, there was no overlap in speech tasks between the current study and the prior studies (Nip, 2017; Nip & Garellek, 2021). Participants included nine children with CP (M = 9.1 years, SD = 3.2 years; six boys) and nine age- and sex-matched TD peers (M = 9.0 years, SD = 3.6 years; six boys). Details about each participant are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants with cerebral palsy (CP), including age (in years;months), sex, type of CP, Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS; Palisano et al., 1997; I is most mild and V is most severe), dysarthria type, single-word intelligibility, sentence intelligibility, Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition (CELF-4; Semel et al., 2003; scores of 85 and higher represent language scores within normal limits) Core Language standard score, and the age of the sex-matched typically developing (TD) peer.

| Participant | Age | Sex | CP type | GMFCS | Word intelligibility | Sentence intelligibility | CELF-4 | Age of TD peer | Speech characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5;4 | Male | Spastic hemiplegia | III | 72% | N/A | 75 | 5;7 | Spastic dysarthria: slow rate, distorted vowels, imprecise articulation, reduced pitch, reduced loudness, strain-strangled voice, hypernasality, short breath groups |

| 2 | 5;8 | Female | Spastic quadriplegia | V | 23% | 18% | 106 | 5;2 | Spastic dysarthria: slow rate, imprecise articulation, reduced loudness, mild hypernasality, mild strain-strangled voice, short breath groups, voice breaks |

| 3 | 6;6 | Male | Spastic diplegia | III | 72% | 83% | 106 | 6;2 | Spastic dysarthria: slow rate, mild monopitch, reduced loudness, /s/ articulation error |

| 4 | 7;5 | Female | Spastic hemiplegia | III | 76% | 86% | 102 | 7;4 | Spastic dysarthria: reduced pitch, mild strained-strangled voice, hypernasality, glottal fry |

| 5 | 8;2 | Male | Spastic diplegia | II | 80% | 77% | 98 | 8;9 | Mild spastic dysarthria: occasional glottal fry, slow rate, /s/ articulation error |

| 6 | 9;9 | Male | Spastic hemiplegia | III | 79% | 76% | 67 | 9;0 | Spastic dysarthria: mild strained-strangled voice, hypernasality |

| 7 | 10;7 | Male | Spastic quadriplegia | IV | 85% | 96% | 127 | 10;11 | No detectable dysarthria, /r/ articulation error |

| 8 | 12;4 | Male | Spastic diplegia | II | 89% | 96% | 112 | 13;2 | No detectable dysarthria, some glottal fry |

| 9 | 15;0 | Female | Spastic diplegia | II | 82% | 93% | 129 | 15;7 | No detectable dysarthria |

Note. N/A = not applicable.

Children in the CP group had a medical diagnosis of spastic CP. Most of the children in this group had age-appropriate language per the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition (CELF-4; Semel et al., 2003). Gross Motor Function Classification System scores (Palisano et al., 1997) were rated to broadly categorize each child's degree of gross motor involvement (I = can walk without assistance, V = requires a manual wheelchair). Finally, three certified speech-language pathologists (SLPs) with a mean of 19.67 years of experience in the profession, including the author, identified the speech characteristics for all participants individually. A group discussion among all three SLPs was conducted to compare judgments. In cases where there were some differences in the judgments, the SLPs discussed their perceptions of that child's speech until a consensus was reached. These characteristics are also listed in Table 1. Intelligibility for the CP group was tested with the Test of Children's Speech (Hodge et al., 2009) for the younger children. Older children (over the age of 11 years) were assessed with the Speech Intelligibility Test (Yorkston, Beukelman, et al., 2007). Both tests have single-word and sentence intelligibility subtests. Intelligibility for both tests were judged by three naïve listeners using orthographic transcription, which is the most reliable for method of obtaining information on listeners' ability to decode the speech signals produced by this population (Hustad et al., 2015).

Three of the participants (Participants 7, 8, and 9) did not have a clinical diagnosis of dysarthria, although Participant 7 did have articulation errors for /r/. Although not all children with CP have dysarthria (e.g., Hustad et al., 2010), previous studies have indicated that children with CP and no clinical signs of dysarthria can demonstrate speech changes when their systems are more taxed, such as when they are asked to produce longer utterances (Allison & Hustad, 2014). Similarly, aspects of speech motor control, such as temporal coordination of lip movements, can be impaired in less familiar speech tasks (e.g., repeating nonsense syllables, DDK) even for some children with CP and no clinical signs of dysarthria (Nip, 2017). Therefore, these participants without dysarthria were included in this study to provide some preliminary descriptive information on whether children with CP and no clinical diagnosis of dysarthria demonstrated similar patterns of speech motor control changes related to loudness manipulations to their peers with dysarthria secondary to spastic CP.

Children in the TD group had no history of neurological, motor, speech, language, and/or hearing difficulties, per parent report. All participants in the TD group were also tested with the CELF-4 to verify that their language skills were within normal limits. All participants passed a hearing screening at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz at 20 dB HL in at least one ear. Participants' oral mechanism was screened Oral Speech Mechanism Screening Examination–Third Edition (St. Louis & Ruscello, 2000), and no structural differences (e.g., cleft palate) in their oral mechanism were noted for any of the participants.

Recording Lip and Jaw Movement

Participants were seated in front of an eight-camera optical motion capture system (Motion Analysis, Ltd.). Fifteen spherical reflective markers were placed on the face. Four of these markers were placed on a rigid head plate that was later used to express an anatomical coordinate system. Markers were also placed above each eyebrow, at the top of the nose, and at the tip of the nose. Lip markers were placed on the vermillion border of the upper and lower lips and at the corners of the mouth. A jaw marker placed on the midline of the chin and markers were placed approximately 2 mm to each side of this central jaw marker. A head-mounted condenser microphone (Shure MC50B) placed approximately 10 cm from the mouth, and the audio signal was split so that audio was recorded both by a Marantz digital recorder (PMD660) and a video recorder (Sony HDR-HC9). The Marantz PMD660 recorded the audio in .wav format (16 bit, 44.1 kHz), while the SONY HDR-HC9 recorded a digital video and audio signal (.avi) that was aligned with the kinematic data that were later used to identify the kinematic signals of interest (see below). A reference tone of 1000 Hz at 90 dB SPL, as measured by a sound pressure level meter (Extech HD600), was also recorded 30 cm from the speaker after each participant's experimental session.

Speaking Tasks

Participants were asked to produce the sentence, “Buy Bobby a puppy,” in two different speaking conditions. First, they were asked to produce 10 repetitions of the sentence in their habitual rate and loudness before being asked to produce 10 repetitions of the same sentence in their “loud voice.” Instruction to speak in a loud voice and models produced by trained research assistants were provided for the participants to ensure they understood the task.

Data Processing

Each repetition was separated into its own file, and the markers were labeled in Cortex (Motion Analysis, Ltd.). These files were then analyzed using SMASH (Green et al., 2013), a set of algorithms to analyze speech data in MATLAB (MathWorks, 2015). The beginning of each repetition was defined as the jaw closure for the /b/ in “buy”; the end of each repetition was defined as the jaw opening for /i/ in “puppy.”

Measures of average speed, range of movement, and utterance duration were obtained for the upper lip, lower lip, and jaw. All three articulators were included as they differentially contribute to oral closure (Green et al., 2000), and no known study has determined which articulator might change more when children with and without CP are asked to talk more loudly.

To evaluate movement pattern variability, the LAVI (Smith & Zelaznik, 2004) was calculated using SMASH because it also provides an overall index of coordination. To calculate the LAVI, the distance between the lower lip and upper lip was calculated for each time point. This new signal was then time-normalized across a 1000-point time axis, and the repetitions for each participant during each task (habitual speech, louder speech) were amplitude-normalized. The standard deviations among the 10 repetitions were calculated at 50 points and summed together (Smith & Zelaznik, 2004).

Interarticulator coordination of the upper and lower lips was also calculated because of its strong association with the severity of the speech impairment (Nip, 2017) and to provide an indication of whether spatial or temporal coordination may be the primary contributor to any observed LAVI changes. To calculate interarticulator coordination, a cross-correlation analysis was completed (Green et al., 2000), yielding the cross-correlation coefficient, which represents the degree of spatial coordination, and the lag, which represents the temporal coordination.

To obtain measures of spectral tilt and CPP, the /ɑ/ in “Bobby” was extracted from the audio recording of each sentence repetition using Adobe Audition 2023 (Adobe, 2023). The onset and offset of the vowel were defined as the first glottal pulse after the stop burst and the final glottal pulse before the stop gap of the following /b/, respectively.

VoiceSauce (Shue et al., 2011) was used to calculate measures of spectral tilt (H1* − H2*, H1* − A2*). The asterisks (*) represent that the VoiceSauce algorithm accounts for the formants, which would amplify harmonics around those formant frequencies, by correcting the harmonic amplitudes affected by the formants and the associated bandwidths.

H1* − H2*, which measures the change in amplitude between the first (H1) and second harmonic (H2), represents low-frequency spectral tilt. H1* − A2*, which measures the change in amplitude between the first harmonic (H1) and the harmonic closest to F2 (A2), represents high-frequency spectral tilt. Although highly related, H1* − H2* and H1* − A2* provide insights into different aspects of vocal fold articulation. H1* − H2* is more associated with the glottal open quotient (Kreiman & Gerratt, 2012; Samlan et al., 2013) and the stiffness of the medial vocal fold (Zhang, 2016). In contrast, H1* − A2* is more associated with vocal fold closing speed and symmetry (Hanson et al., 2001; Stevens, 1977). VoiceSauce was also used to calculate CPP, which is a harmonics-to-noise measure that is associated with the degree of aperiodic noise caused by aspiration or irregular vocal fold vibration (Garellek, 2019; Samlan & Kreiman, 2014; Zhang et al., 2013).

Data Analysis

Multiple mixed models with participants on the random statement, which accounts for the individual variation, were calculated with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., 2014) PROC MIXED to determine how all dependent variables, except for LAVI, were affected by the independent variables of group (CP, TD) and task (habitual, loud). Because the LAVI is calculated using all the repetitions for a given participant, a mixed model, without participants on the random statement was used to evaluate the effect of group and task on that variable. All models included age and sex as covariates. Post hoc testing was completed using LSMEANS with a Bonferroni correction. The significance level was set to .05 for all models. Individual means and standard deviations for each dependent variable during habitual and loud speaking tasks are provided in Supplemental Material S1.

Results

To ensure that participants did significantly change their vocal intensity between the two speaking tasks, the root mean square (RMS) for each repetition, obtained from the .wav recordings, and the 1000 Hz reference tone was obtained using TF-32 (Milenkovic, 2005). The RMS for each repetition was then expressed relative to the RMS of the reference tone. Because the recordings of the reference tone were either missing or corrupted for two participants, group analyses to evaluate changes in RMS between habitual and louder speech could not be conducted. Instead, mixed models for each participant were conducted to examine the effect of task (habitual, loud) on the RMS relative to the calibration tone. For the two participants (Participants 1 and 4) with corrupted calibration tone recordings, video recordings were used to verify that the microphone was in the same position for each task. The raw RMS values for each repetition were then used to verify that there was a change in vocal intensity between habitual speech and louder speech conditions for these two participants. Findings for each individual participant are listed in Table 2. All participants, except Talker 1, had significant changes in RMS between habitual and louder speech.

Table 2.

F and p values for models of root mean square changes by speaking task (habitual vs. loud speech) for each participant with cerebral palsy (CP) and their age- and sex-matched typically developing (TD) peer.

| Participant | CP |

TD peer |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | |

| 1 | 1.22 | .28 | 40.37 | < .0001 |

| 2 | 4.66 | .04 | 61.86 | < .0001 |

| 3 | 107.75 | < .0001 | 21.92 | < .0001 |

| 4 | 318.3 | < .0001 | 54.08 | < .0001 |

| 5 | 235.33 | < .0001 | 75.74 | < .0001 |

| 6 | 34.68 | < .0001 | 148.94 | < .0001 |

| 7 | 392.03 | < .0001 | 1663.32 | < .0001 |

| 8 | 436.92 | < .0001 | 431.59 | < .0001 |

| 9 | 196.05 | < .0001 | 6318.62 | < .0001 |

Utterance Duration

Figure 1 shows the results of utterance duration. Age was the only variable with a significant effect on utterance duration, F(1, 175) = 89.25, p < .001, with older children having shorter utterance durations (or faster speaking rates) than younger children. There were no significant main effects of group, F(1, 176) = 0.6, p = .42, or task, F(1, 168) = 0.39, p = .53, and there was no significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 168) = 1.77, p = .19.

Figure 1.

Utterance duration and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

Kinematic Measures

For the kinematic measures, results are discussed for each articulator. Figures 2 and 3 depict path distance and average speed, respectively, for all three articulators (jaw, lower lip, and upper lip).

Figure 2.

Path distances and standard errors of the mean for habitual (H) and louder (L) speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups. The left-most panel represents data for the jaw, the middle represents data for the lower lip, and right-most panel represents data for the upper lip.

Figure 3.

Average speeds and standard errors of the mean for habitual (H) and louder (L) speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups. The left-most panel represents data for the jaw, the middle represents data for the lower lip, and right-most panel represents data for the upper lip.

Jaw

Path Distance

There was a significant main effect of age, F(1, 166) = 16.38, p < .001, on path distance, with greater distances for older children. Although there were significant main effects of group, F(1, 168) = 11.05, p < .01, and task, F(1, 165) = 247.22, p < .001, these were qualified by the significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 165) = 3.99, p < .05. Post hoc testing revealed that for both the CP and TD groups, louder speech was produced with greater path distances than habitual speech. Furthermore, the TD group produced utterances with larger path distances than the CP group but only for louder speech (t = 3.90, adjusted p < .001). There was no difference between the two groups in jaw path distance for habitual speech (t = 1.72, adjusted p = .53). There was also no significant main effect of sex, F(1, 165) = 0.37, p = .54.

Average Speed

Similar to path distance, jaw average speed had a significant age effect, F(1, 172) = 292.30, p < .001; older children had faster jaw speeds than younger children. There was a significant main effect of group, F(1, 173) = 8.99, p < .01, with slower speeds for the CP group. Task was also significant, F(1, 170) = 243.52, p < .001. Overall, louder speech was produced at faster speeds than habitual speech. The main effect of sex, F(1, 171) = 1.26, p = .26, and the Group × Task interaction, F(1, 170) = 2.46, p = .12, was not significant.

Lower Lip

Path Distance

For the lower lip, both age, F(1, 174) = 5.73, p < .05, and sex, F(1, 173) = 76.38, p < .001, had a significant effect on path distance. Older children moved their lower lip less, and girls moved their lower lip with smaller path distances than boys. There were significant main effects of group, F(1, 175) = 34.46, p < .001, and task, F(1, 169) = 165.04, p < .001, which were qualified by a significant two-way Group × Task interaction, F(1, 169) = 9.30, p < .01. Post hoc testing indicated that children with CP produced utterances with greater lower lip path distances than the TD peers (t = 5.87, adjusted p < .001), and both groups had greater path distances for louder speech than habitual speech (t = 12.85, adjusted p < .001).

Average Speed

There was a significant effect of age, F(1, 174) = 19.11, p < .001, on lower lip speed; older children produced speech with faster average lower lip speeds. The effect of sex was also significant, F(1, 174) = 60.45, p < .001, with girls having slower speeds than boys. The main effects of group, F(1, 175) = 31.22, p < .001, and task, F(1, 168) = 176.95, p < .001, were significant but these were qualified by the significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 168) = 20.00, p < .001. Post hoc testing indicated that both groups produced louder speech with faster lower lip average speeds than habitual speech (t = 13.30, adjusted p < .001) and that the CP group produced speech with faster speeds than the TD group for habitual and louder speech (t = 5.59, adjusted p < .001).

Upper Lip

Path Distance

The model for upper lip path distance revealed a significant main effect of task, F(1, 169) = 52.38, p < .001; however, this was qualified by the significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 169) = 5.53, p < .05. Post hoc testing revealed that both groups produced louder speech with greater upper lip path distances (t = 7.24, adjusted p < .001). There was no significant effect of group, F(1, 174) = 0.85, p = .36; age, F(1, 173) = 2.36, p = .12; or sex, F(1, 172) = 0.52, p = .47.

Average Speed

There was a significant effect of age, F(1, 174) = 21.08, p < .001, in the model for upper lip average speed, with older children producing speech with faster speeds than younger children. The main effect of task was also significant, F(1, 170) = 50.57, p < .001. Louder speech was produced with faster upper lip average speeds than habitual speech. There were no significant main effects of group, F(1, 175) = 2.90, p = .09, or sex, F(1, 173) = 1.61, p = .21, and the Group × Task interaction was also not significant, F(1, 170) = 2.57, p = .11.

Interarticulator Coordination

LAVI

The LAVI, as shown in Figure 4, was used to determine the movement pattern variability during habitual and louder speech. There was a significant effect of age, F(1, 30) = 17.85, p < .001, with less variability for older children. The main effect of task, F(1, 30) = 5.01, p < .05, was also significant. Louder speech was associated with less variability than habitual speech. There was no significant effect of group, F(1, 30) = 1.48, p = .23, or sex, F(1, 30) = 3.86, p = .06, and there was no significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 30) = 0.03, p = .85. Overall, this indicates that both groups produced louder speech with less variability than habitual speech.

Figure 4.

Lip aperture variability index and standard deviation for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

Spatial Coordination

Cross-correlation of the lower and upper lips was conducted for each repetition to identify if the change in coordination for louder speech was primarily due to changes in spatial coordination or temporal coordination. The cross-correlation coefficient, as shown in Figure 5, represents the degree of spatial coordination between the upper and lower lips. There was a significant effect of age, F(1, 177) = 14.06, p < .001. Older children had greater spatial coordination than younger children. There was also a significant effect of sex, F(1, 177) = 10.15, p < .01. Overall, girls produced speech with reduced spatial coordination than boys. The main effect of group, F(1, 178) = 12.29, p < .001, was also significant in the model. Children with CP produced speech with less spatial coordination between the lips than their TD peers. There was no significant main effect of task, F(1, 182) = 0.97, p = .32, or a significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 170) = 1.70, p = .19.

Figure 5.

Cross-correlation coefficients of the upper and lower lip and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

Temporal Coordination

The lag values obtained by the cross-correlation function represent the degree of coordination between the lips in time. Lower lag values represent a higher degree of temporal coordination. Because the lag values were not normally distributed, a log transformation was used before the mixed model was run. Figure 6 shows the results of lag values but without the log transformation to ease interpretation. There were significant effects of age, F(1, 168) = 4.00, p < .05, and sex, F(1, 167) = 6.82, p < .01. Increased age was associated with decreased lag and girls had increased lag values when compared to boys. The main effect of task was also significant, F(1, 173) = 30.34, p < .001. For both groups, habitual speech had significantly greater lag values than louder speech. There was no significant effect of group, F(1, 168) = 2.06, p = .15, nor was there a significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 173) = 0.01, p = .93.

Figure 6.

Lag values of the upper and lower lip and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

Vocal Fold Articulation Measures

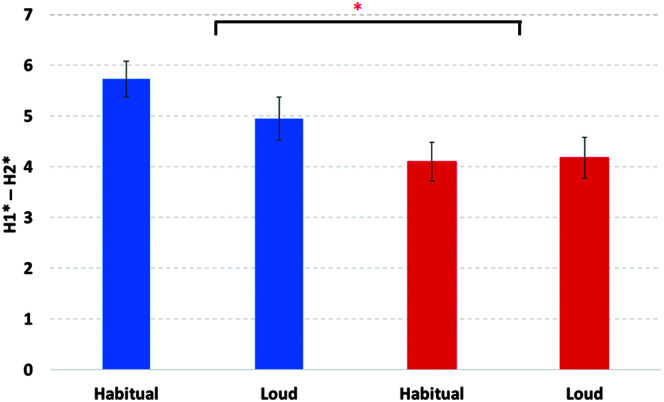

H1* − H2*

The model for H1* − H2* or low-frequency spectral tilt, as shown in Figure 7, had a significant effect of age, F(1, 174) = 13.78, p < .001. Older children had lower H1* − H2* values than younger children. The main effect of group, F(1, 176) = 8.88, p < .01, was also significant. Children with CP had greater H1* − H2* values when compared to their TD peers. There was no significant main effect of sex, F(1, 175) = 1.03, p = .31; task, F(1, 177) = 0.98, p = .32; or a significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 177) = 1.38, p = .24.

Figure 7.

Low-frequency spectral tilt (H1* − H2*) and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

H1* − A2*

Figure 8 shows the results for H1* − A2* or high-frequency spectral tilt. There was a significant effect of sex, F(1, 175) = 10.62, p < .01, on H1* − A2*. Girls had greater high-frequency spectral tilt in comparison to boys. There was a significant main effect of task, F(1, 178) = 58.19, p < .001. Louder speech had lower H1* − A2* values or reduced high-frequency spectral tilt when compared to habitual speech. There was no main effect of age, F(1, 175) = 0.21, p = .65, or group, F(1, 176) = 0.96, p = .33, nor was there a significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 178) = 0.57, p = .45.

Figure 8.

High-frequency spectral tilt (H1* − A2*) and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

CPP

Figure 9 shows the results for CPP. A significant effect of age, F(1, 175) = 38.89, p < .001, was found in the model for CPP. Older children had higher CPP values than younger children. There were significant main effects of group, F(1, 177) = 13.68, p < .01, and task, F(1, 177) = 300.44, p < .001. These were qualified by the significant Group × Task interaction, F(1, 177) = 17.06, p < .001. Both groups had greater CPP values for louder speech when compared to habitual speech (t = 17.33, adjusted p < .001). The TD group had greater CPP values than the CP group but only for habitual speech (t = 5.30, adjusted p < .001). There was no significant difference in CPP between the groups for louder speech. There was no significant main effect of sex, F(1, 176) = 0.20, p = .66.

Figure 9.

Cepstral peak prominence (CPP) and standard errors of the mean for habitual and louder speech for the cerebral palsy (blue) and typically developing (red) groups.

Discussion

The current study is the first known investigation to identify articulatory and laryngeal changes in response to speaking louder in children with CP and their TD peers. Overall, the findings suggest that the two groups change both oral articulatory and vocal fold movements when speaking more loudly. In addition, the results also demonstrate that the speech motor control of children with CP differs from their TD peers in both subsystems.

The individual patterns of change between habitual and louder speech, as presented in Supplemental Material S1, demonstrates that participants generally followed the statistically significant results for all the dependent variables. For example, the group statistical analyses indicated that louder speech was found to be produced with greater lower lip path distances. This pattern is reflected in the individual data for all participants except one of the TD peers (age- and sex-matched peer of Participant 9), who had the same path distance for both tasks. This general concordance of group and individual data was somewhat surprising because the CP group was heterogeneous. Participants had a large age range (5–15 years), and they varied in their presence and/or severity of the speech impairments. It might be expected that the participants with CP and no perceptible signs of dysarthria would have differing patterns of results in comparison to the participants with CP with dysarthria. However, the individual data for both Participants 8 and 9 follow the same patterns as the other CP participants for all the dependent variables. Participant 7, who had a residual /r/ articulation error but no signs of dysarthria, demonstrated some differences in his pattern of results, including decreasing jaw and upper lip path distances, decreasing upper lip average speed, no change in LAVI, and increasing lag (reducing temporal coordination) for louder speech. However, his pattern of results was the same for every other dependent variable (lower lip path distance, jaw and lower lip average speed, H1* − H2*, H1* − A2*, and CPP).

Only one child (Participant 1) did not significantly change his vocal intensity (RMS) when cued to speak loudly despite repeated models and extended instruction throughout the task. Interestingly, his pattern of findings (see Supplemental Material S1) matched the overall pattern of findings of task differences, including having increased jaw and lower lip path distances, faster jaw and lower lip average speeds, lower LAVI, reduced lag, reduced H1* − A2*, and increased CPP for louder speech as compared to habitual speech. He only differed from the overall pattern of findings in his upper lip path distance and average speed. This finding suggests that although there may not be observable changes in vocal intensity, the hypothesized increased articulatory effort associated with louder speech (Rosenbek & LaPointe, 1985; Sapir et al., 2011; Tjaden et al., 2013) might still be reflected in speech motor control for some children with CP.

Oral Articulatory Motor Control Differs Between Louder and Habitual Speech in Both Children With CP and TD Peers

Both groups increase path distances and average speeds for the jaw, lower lip, and upper lip; increase temporal coordination between the lips, reduce movement pattern variability; reduce high-frequency (H1* − A2*) spectral tilt; and increase CPP when speaking more loudly, matching the experimental hypotheses. The findings of larger path distances for louder speech are consistent with increased F1 values observed in children with CP when they are cued to produce louder speech (Levy et al., 2020). In treatment studies, children with CP demonstrate increased F1 after intervention (Langlois et al., 2020), which is also consistent with the kinematic findings from the current study. The observed increase in path distance and average speed during louder speech is also consistent with the increased range of movement and speed as seen in previous research in healthy young adults for the lower lip and jaw (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006; Kleinow et al., 2001). Interestingly, sentences produced with louder speech were not significantly different from those produced with habitual speech in utterance duration, unlike prior studies in children with dysarthria secondary to CP (Levy et al., 2020). Changes in utterance duration in response to being cued to speak more loudly have also been mixed in studies of adults. Increases in utterance duration or a corresponding decrease in rate have been observed in healthy adults, but not those with dysarthria (Tjaden & Wilding, 2004). However, other studies of healthy adults have observed no changes in utterance duration or rate (Mefferd & Green, 2010).

Prior studies have also shown mixed findings for movement pattern variability differences between habitual and louder speech. The current study found that the LAVI decreased for louder speech in comparison to habitual speech for both groups, indicating that movement pattern variability decreased with louder speech. A prior study of louder speech changes in young adults and adults with PD have shown no changes in the LAVI (Darling & Huber, 2011). However, other studies have examined changes to movement variability using the STI (Smith et al., 1995), which is a measure of movement pattern variability for a single articulator. These studies have also demonstrated a mixed pattern of findings of movement pattern variability for habitual and louder speech. One study reported decreased movement pattern variability for louder speech when compared to habitual speech in healthy young adult talkers (Huber & Chandrasekaran, 2006). However, other studies have found no changes between habitual and louder speech in young adults (Kleinow et al., 2001; Mefferd & Green, 2010), older adults, or adults with PD (Kleinow et al., 2001).

As LAVI also reflects overall coordination between the upper and lower lips, the reduction in LAVI for louder speech in both groups indicates that overall coordination between these two articulators improved during louder speech. Interarticulator coordination was also examined to identify if spatial or temporal coordination is more affected by louder speech. Notably, both the CP and TD groups had reduced lag values or increased temporal coordination when producing louder speech whereas spatial coordination did not change for either group.

Taken together, results from the current study and prior studies suggest that increased amplitude of movements, as reflected by the path distance, is the aspect of oral articulatory control that changes with louder speech. Further research is needed to better determine how other variables, in particular movement pattern variability and interarticulator coordination, are affected in either children with CP or their TD peers.

Vocal Fold Articulation Changes in Response to Louder Speech in Both Children With CP and TD Peers

For both groups, high-frequency spectral tilt (H1* − A2*) decreased during louder speech in comparison to habitual speech. This finding indicates that when speaking louder, both groups have greater energy for higher frequency harmonics and, therefore, higher formants than when speaking at their habitual loudness, and this change may represent more complete vocal fold adduction (Hanson et al., 2001). Similarly, TD children increase the mean energy between 1 and 3 kHz, which reduces spectral tilt, when they try to speak more clearly in challenging communicative environments (e.g., increased background noise), which required the children to increase their vocal loudness (Hazan et al., 2016). Furthermore, louder speech is produced with greater CPP values than habitual speech by both groups, indicating that the vocal fold vibrations are less noisy during louder speech. Speaking more loudly also provides the CP group with an additional benefit; although TD children have significantly higher CPP (less noisy) values than the CP group during habitual speech, there is no significant difference in CPP between the two groups during the production of louder speech.

Speech Motor Control of Children With CP Differ From Their TD Peers

The habitual speech condition also provides some insight into the speech motor control differences between the two groups. Similar to previous studies (Hong et al., 2011; Nip, 2013), the CP group had increased lower lip path distances for children with CP, which likely account for the faster lower lip speeds observed in the CP group (Nip, 2013). However, the results for the jaw did not match those of prior studies, which reported that children with CP had larger and faster jaw movements (Hong et al., 2011; Nip et al., 2017). In the current study, jaw path distances were the same between both groups for habitual speech, and the TD group had faster average jaw speeds as compared to the CP group. This difference in jaw movement characteristics may be due to the stimuli utilized between studies (e.g., sentence primarily loaded with bilabial consonants in the current study vs. sentences loaded with alveolar consonants in the study of Nip et al., 2017).

Only a very small number of studies have examined movement pattern variability and interarticulator coordination in children with CP. The current study found no group differences in movement pattern variability whereas Nip et al. (2017) demonstrated that children with CP had increased movement pattern variability, as measured by the STI, for both the jaw and tongue tip when compared to TD peers (Nip et al., 2017). One reason for the discrepancy in findings between these studies is the use of the LAVI, which evaluates the distance between the two lips across the utterance, rather than the STI of individual articulators, to examine movement pattern variability.

Similar to a prior study, the CP group had reduced spatial coordination (cross-correlation coefficient) when compared to their TD peers (Nip, 2017). However, in contrast to previous investigations (Hong et al., 2011; Nip, 2017), there were no group differences in temporal coordination (lag values). The similarity in spatial coordination finding between the current study and that of Nip (2017) should not be surprising given that much of the sample in the current study overlaps with that prior study. However, a key difference in the two studies is that Nip (2017) examined one closing and opening gesture for the sentence whereas the current study examined the cross-correlation for the entire sentence. Potentially, temporal coordination may be more sensitive than spatial coordination to which segments are analyzed (e.g., a single articulatory gesture vs. an entire utterance). Additional studies with larger samples are required to determine how movement pattern variability and interarticulator coordination might differentiate children with CP from their TD peers.

In the laryngeal subsystem, children with CP have reduced CPP values as compared to TD peers, which is similar to a prior study (Nip & Garellek, 2021). However, unlike previous findings (Nip & Garellek, 2021), children with CP had greater low-frequency (H1* − H2*) spectral tilt, but no differences in high-frequency (H1* − A2*) spectral tilt when compared to their TD peers. H1* − H2* increases for tasks requiring greater linguistic processing, such as narrative retell as compared to single vowels (Nip & Garellek, 2021). Future research is needed to better understand how linguistic processing might impact speech motor control of the laryngeal subsystem, particularly for spectral tilt.

Clinical and Theoretical Implications and Limitations

Multiple treatment paradigms, such as LSVT-LOUD (Boliek & Fox, 2017; Fox & Boliek, 2012; Langlois et al., 2020), the subsystem approach (Pennington et al., 2006, 2010, 2013), and Speech Intelligibility Treatment (Levy et al., 2021; Moya-Galé et al., 2021), include a focus on improving vocal loudness to improve speech production and/or intelligibility in children with CP. The changes in both the articulatory (increased path distance, increased average speed, reduced movement pattern variability, improved temporal coordination) and laryngeal (reduced high-frequency spectral tilt and increased CPP) subsystem variables associated with louder speech may be part of the reason intervention focusing on louder speech may increase intelligibility in this population (e.g., Langlois et al., 2020). Although talking more loudly increases the audibility of the speech signal (Neel, 2009), the interactions between vocal intensity and articulatory adjustments may also contribute to the increased intelligibility (Pittman & Wiley, 2001). Potentially, the observed increased articulatory excursion and coordination during louder speech may help with improving articulatory precision associated with loudness intervention in this population (Boliek & Fox, 2017). The decreased noisiness of the vocal fold vibrations and increased acoustic energy in higher harmonics and formants may also allow listeners to better distinguish what is being said by these children. These findings also suggest that children with CP and their TD peers may use louder speech to hyperarticulate (Lindblom, 1990) and that although respiratory and laryngeal adjustments are made to produce louder speech, the putative increased effort required for louder speech also spreads to the oral articulatory subsystem (Rosenbek & LaPointe, 1985; Sapir et al., 2011; Tjaden et al., 2013).

The current study has a number of limitations. Notably, the current study has a small sample size and a large age range. Given the great deal of heterogeneity in speech production abilities and impairments in children with CP in the current sample and the significant effect of age on almost all the variables, studies with larger sample sizes are required before generalization of these findings can be made to the population of children with CP. In addition, although the individual data for almost all of the participants with CP reflect the general pattern of findings, not all of these participants had dysarthria. Future studies that compare and contrast how louder speech affects speech motor control in children with dysarthria secondary to CP and in children with CP and no dysarthria are warranted. The current study utilized optical motion capture; therefore, only lip and jaw kinematic data could be obtained and analyzed. As the tongue is the major articulator for most phonemes (Wang et al., 2013), future studies should examine how lingual movements change in response to being cued to produce louder speech in this population. The relative contribution of audibility and speech motor control changes associated with louder speech on speech intelligibility ratings has not been explored in children with dysarthria and should be explored in future studies. Finally, the current study is in children who are cued to produce louder speech, and the findings may not reflect the speech motor control changes after loudness intervention. Examination of articulatory and laryngeal changes after loudness intervention should be conducted to determine if the same variables change after intervention. If the same variables (e.g., path distance, spectral tilt) change in both cueing and intervention studies, then these variables could be the basis for clinical tasks that would dynamically assess if a child with dysarthria secondary to CP might respond more or less strongly to a speech intervention that targets louder speech.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of the study, the speech data generated and analyzed for the current study are not publicly available to be compliant with the institutional review board requirements. However, data spreadsheets with de-identified participant information may be available from the author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R03-DC012135 awarded to the author, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation, and the San Diego State University Grants Program. We wish to thank all participants in this study. Thank you to Carlos Arias, Katherine Bristow, Jennise Corcoran, Mackenzie Gomes, Matthew Gutierrez, Casey Hine, Nicole Ishihara, Rachel Isteepho, Lindsay Kempf, Taylor Kubo, Alison Lebenbaum, Jordan Mantel, Kristen Morita, Cara Nutt, Hannah Richardson, Jennifer Rowe, Emily Shearon, and Tatiana Zozulya for their assistance with data collection and data analysis.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R03-DC012135 awarded to the author, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation, and the San Diego State University Grants Program.

References

- Adobe. (2023). Adobe Audition [Computer software].

- Allison, K. M., & Hustad, K. C. (2014). Impact of sentence length and phonetic complexity on intelligibility of 5-year-old children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 396–407. 10.3109/17549507.2013.876667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison, K. M., & Hustad, K. C. (2018). Data-driven classification of dysarthria profiles in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(12), 2837–2853. 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-17-0356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansel, B. M., & Kent, R. D. (1992). Acoustic–phonetic contrasts and intelligibility in the dysarthria associated with mixed cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35(2), 296–308. 10.1044/jshr.3502.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boliek, C. A., & Fox, C. M. (2017). Therapeutic effects of intensive voice treatment (LSVT LOUD®) for children with spastic cerebral palsy and dysarthria: A Phase I treatment validation study. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(6), 601–615. 10.1080/17549507.2016.1221451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann-Bauser, M., Stan, J. H. V., Sampaio, M. C., Bohlender, J. E., Hillman, R. E., & Mehta, D. D. (2021). Effects of vocal intensity and fundamental frequency on cepstral peak prominence in patients with voice disorders and vocally healthy controls. Journal of Voice, 35(3), 411–417. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling, M., & Huber, J. E. (2011). Changes to articulatory kinematics in response to loudness cues in individuals with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(5), 1247–1259. 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C. M., & Boliek, C. A. (2012). Intensive voice treatment (LSVT LOUD) for children with spastic cerebral palsy and dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(3), 930–945. 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garellek, M. (2019). The phonetics of voice. In Katz W. & Assmann P. (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of phonetics (pp. 75–106). Routledge. 10.4324/9780429056253-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goozee, J. V., Shun, A. K., & Murdoch, B. E. (2011). Effects of increased loudness on tongue movements during speech in nondysarthric speakers with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 19(1), 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. R., Moore, C. A., Higashikawa, M., & Steeve, R. W. (2000). The physiologic development of speech motor control: Lip and jaw coordination. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43(1), 239–255. 10.1044/jslhr.4301.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. R., Wang, J., & Wilson, D. L. (2013). SMASH: A tool for articulatory data processing and analysis. Interspeech 2013, 1331–1335.

- Hanson, H. M., Stevens, K. N., Kuo, H.-K. J., Chen, M. Y., & Slifka, J. (2001). Towards models of phonation. Journal of Phonetics, 29(4), 451–480. 10.1006/jpho.2001.0146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, V., Tuomainen, O., & Pettinato, M. (2016). Suprasegmental characteristics of spontaneous speech produced in good and challenging communicative conditions by talkers aged 9–14 years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(6), S1596–S1607. 10.1044/2016_JSLHR-S-15-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelmann, K., & Uvebrant, P. (2011). Function and neuroimaging in cerebral palsy: A population-based study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 53(6), 516–521. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, M. M., Daniels, J., & Gotzke, C. L. (2009). TOCS+ Intelligibility Measures (Version 5.3) [Computer software]. University of Alberta.

- Hodge, M. M., & Gotzke, C. L. (2014). Construct-related validity of the TOCS measures: Comparison of intelligibility and speaking rate scores in children with and without speech disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 51, 51–63. 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.-H., Chen, H.-C., Yang, F. G., Wu, C.-Y., Chen, C.-L., & Wong, A. M. (2011). Speech-associated labiomandibular movement in Mandarin-speaking children with quadriplegic cerebral palsy: A kinematic study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2595–2601. 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, J. E., & Chandrasekaran, B. (2006). Effects of increasing sound pressure level on lip and jaw movement parameters and consistency in young adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(6), 1368–1379. 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/098) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad, K. C., Gorton, K., & Lee, J. (2010). Classification of speech and language profiles in 4-year-old children with cerebral palsy: A prospective preliminary study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53(6), 1496–1513. 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad, K. C., Oakes, A., & Allison, K. (2015). Variability and diagnostic accuracy of speech intelligibility scores in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), 1695–1707. 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-S-14-0365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad, K. C., Schueler, B., Schultz, L., & DuHadway, C. (2012). Intelligibility of 4-year-old children with and without cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(4), 1177–1189. 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/11-0083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinow, J., Smith, A., & Ramig, L. O. (2001). Speech motor stability in IPD: Effects of rate and loudness manipulations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(5), 1041–1051. 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/082) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiman, J., & Gerratt, B. R. (2012). Perceptual interaction of the harmonic source and noise in voice. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 131(1), 492–500. 10.1121/1.3665997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, C., Tucker, B. V., Sawatzky, A. N., Reed, A., & Boliek, C. A. (2020). Effects of an intensive voice treatment on articulatory function and speech intelligibility in children with motor speech disorders: A phase one study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 86, Article 106003. 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., Hustad, K. C., & Weismer, G. (2014). Predicting speech intelligibility with a multiple speech subsystems approach in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(5), 1666–1678. 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-13-0292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, E. S. (2014). Implementing two treatment approaches to childhood dysarthria. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 344–354. 10.3109/17549507.2014.894123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, E. S., Chang, Y. M., Hwang, K., & McAuliffe, M. J. (2021). Perceptual and acoustic effects of dual-focus speech treatment in children with dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(6S), 2301–2316. 10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, E. S., Moya-Galé, G., Chang, Y. M., Campanelli, L., MacLeod, A. A. N., Escorial, S., & Maillart, C. (2020). Effects of speech cues in French-speaking children with dysarthria. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(3), 401–416. 10.1111/1460-6984.12526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, B. (1990). Explaining phonetic variation: A sketch of the H&H theory. In Hardcastle W. J. & Marchal A. (Eds.), Speech production and speech modelling (pp. 403–439). Springer. 10.1007/978-94-009-2037-8_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y., & Cooke, M. P. (2008). Speech production modifications produced by competing talkers, babble and stationary noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 124(5), 3261–3275. 10.1121/1.2990705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y., & Cooke, M. P. (2009). The contribution of changes in F0 and spectral tilt to increased intelligibility of speech produced in noise. Speech Communication, 51(12), 1253–1262. 10.1016/j.specom.2009.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks. (2015). MATLAB R2015a [Computer software].

- Mefferd, A. S. (2017). Tongue- and jaw-specific contributions to acoustic vowel contrast changes in the diphthong /ai/ in response to slow, loud, and clear speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(11), 3144–3158. 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-17-0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefferd, A. S., & Green, J. R. (2010). Articulatory-to-acoustic relations in response to speaking rate and loudness manipulations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53(5), 1206–1219. 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic, P. (2005). TF32 [Computer software]. University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Miller, N., Pennington, L., Robson, S., Roelant, E., Steen, N., & Lombardo, E. (2013). Changes in voice quality after speech-language therapy intervention in older children with cerebral palsy. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 65(4), 200–207. 10.1159/000355864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Galé, G., Keller, B., Escorial, S., & Levy, E. S. (2021). Speech treatment effects on narrative intelligibility in French-speaking children with dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(6S), 2154–2168. 10.1044/2020_jslhr-20-00258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel, A. T. (2009). Effects of loud and amplified speech on sentence and word intelligibility in Parkinson disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(4), 1021–1033. 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/08-0119) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nip, I. S. B. (2013). Kinematic characteristics of speaking rate in individuals with cerebral palsy: A preliminary study. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 88–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nip, I. S. B. (2017). Interarticulator coordination in children with and without cerebral palsy. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 20(1), 1–13. 10.3109/17518423.2015.1022809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nip, I. S. B., Arias, C. R., Morita, K., & Richardson, H. (2017). Initial observations of lingual movement characteristics of children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(6S), 1780–1790. 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-16-0239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nip, I. S. B., & Garellek, M. (2021). Voice quality of children with cerebral palsy: A preliminary study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(8), 3051–3059. 10.1044/2021_JSLHR-20-00633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, A., Miniscalco, C., & Lohmander, A. (2014). Consonant production and overall speech characteristics in school-aged children with cerebral palsy and speech impairment. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 386–395. 10.3109/17549507.2014.917440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, A., Miniscalco, C., Lohmander, A., & Himmelmann, K. (2013). Speech problems affect more than one in two children with cerebral palsy: Swedish population-based study. Acta Paediatrica, 102(2), 161–166. 10.1111/apa.12076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E., & Galuppi, B. (1997). Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39(4), 214–223. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, J., Hill, N., Platt, M. J., & Donnelly, C. (2010). Oromotor dysfunction and communication impairments in children with cerebral palsy: A register study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 52(12), 1113–1119. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R. (2002). Prosodic control in severe dysarthria: Preserved ability to mark the question–statement contrast. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45(5), 858–870. 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R. (2003). Acoustic characteristics of the question–statement contrast in severe dysarthria due to cerebral palsy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46(6), 1401–1415. 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L., Lombardo, E., Steen, N., & Miller, N. (2018). Acoustic changes in the speech of children with cerebral palsy following an intensive program of dysarthria therapy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(1), 182–195. 10.1111/1460-6984.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L., Miller, N., Robson, S., & Steen, N. (2010). Intensive speech and language therapy for older children with cerebral palsy: A systems approach. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 52(4), 337–344. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L., Roelant, E., Thompson, V., Robson, S., Steen, N., & Miller, N. (2013). Intensive dysarthria therapy for younger children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(5), 464–471. 10.1111/dmcn.12098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L., Smallman, C., & Farrier, F. (2006). Intensive dysarthria therapy for older children with cerebral palsy: Findings from six cases. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 22(3), 255–273. 10.1191/0265659006ct307xx [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, A. L., & Wiley, T. L. (2001). Recognition of speech produced in noise. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(3), 487–496. 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig, L. O. (1992). The role of phonation in speech intelligibility. In Kent R. D. (Ed.), Intelligibility in speech disorders: Theory, measurement and management (pp. 119–155). John Benjamins. 10.1075/sspcl.1.05ram [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rong, P., Loucks, T., Kim, H., & Hasegawa-Johnson, M. (2012). Relationship between kinematics, F2 slope and speech intelligibility in dysarthria due to cerebral palsy. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 26(9), 806–822. 10.3109/02699206.2012.706686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P., Paneth, N., Leviton, A., Goldstein, M., Bax, M., Damiano, D., Bernard, D., & Jacobsson, B. (2007). A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbek, J. C., & LaPointe, L. L. (1985). The dysarthrias: Description, diagnosis, and treatment. In Johns D. (Ed.), Clinical management of neurogenic communicative disorders (2nd ed., pp. 97–152). Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Sakash, A., Mahr, T. J., Natzke, P. E. M., & Hustad, K. C. (2020). Effects of rate manipulation on intelligibility in children with cerebral palsy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(1), 127–141. 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samlan, R. A., & Kreiman, J. (2014). Perceptual consequences of changes in epilaryngeal area and shape. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 136(5), 2798–2806. 10.1121/1.4896459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samlan, R. A., Story, B. H., & Bunton, K. (2013). Relation of perceived breathiness to laryngeal kinematics and acoustic measures based on computational modeling. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(4), 1209–1223. 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0194) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir, S., Ramig, L. O., & Fox, C. M. (2011). Intensive voice treatment in Parkinson's disease: Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 11(6), 815–830. 10.1586/ern.11.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. (2014). SAS Version 9.4 [Computer software].

- Semel, E., Wiig, E. H., & Secord, W. A. (2003). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition. PsychCorp. [Google Scholar]

- Shue, Y.-L., Keating, P. A., Vicenik, C., & Yu, K. (2011). Voicesauce: A program for voice analysis. Proceedings of the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 1846–1849). UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A., Goffman, L., Zelaznik, H. N., Ying, G., & McGillem, C. (1995). Spatiotemporal stability and patterning of speech movement sequences. Experimental Brain Research, 104(3), 493–501. 10.1007/BF00231983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A., & Zelaznik, H. N. (2004). Development of functional synergies for speech motor coordination in childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychobiology, 45(1), 22–33. 10.1002/dev.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, K. A., Yorkston, K. M., & Duffy, J. R. (2003). Behavioral management of respiratory/phonatory dysfunction from dysarthria: A flowchart for guidance in clinical decision making. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 11(2), xxxiv–lxi. [Google Scholar]

- St. Louis, K. O., & Ruscello, D. M. (2000). Oral Speech Mechanism Screening Examination–Third Edition.

- Stevens, K. N. (1977). Physics of laryngeal behavior and larynx modes. Phonetica, 34(4), 264–279. 10.1159/000259885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden, K., Lam, J., & Wilding, G. (2013). Vowel acoustics in Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis: Comparison of clear, loud, and slow speaking conditions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(5), 1485–1502. 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0259) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden, K., & Wilding, G. E. (2004). Rate and loudness manipulations in dysarthria: Acoustic and perceptual findings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(4), 766–783. 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Stan, J. H., Dijkers, M. P., Whyte, J., Hart, T., Turkstra, L. S., Zanca, J. M., & Chen, C. (2019). The rehabilitation treatment specification system: Implications for improvements in research design, reporting, replication, and synthesis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(1), 146–155. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.09.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]