ABSTRACT

The rise of Islam in Arabia witnessed a scientific pursuit from 8th CE to 14th CE in its vast dominion. Medicine was one among many disciplines that was reshaped during the golden ages of Islamic world. Physicians and scholars from diverse faiths and background flocked in learning centers of Baghdad, Cordoba, and other cities. A multicultural environment of medical research was evolved with fundings from state. From medical teaching and clinical training to the licensing of physicians, many of the modern attributes of medical education were pioneered in Islamic world. The scholarly transfusion from European territories of Islamic world to the Western world in medieval era laid the foundation of modern medical education.

KEYWORDS: Islamic medicine, medical education, research in medicine

INTRODUCTION

Islamic medicine, a historically significant branch of medical knowledge, has played a pivotal role in the development of medical science and healthcare practices in the Islamic world and beyond.[1] Emerged in the 7th century CE with the advent of Islam, Islamic medicine represents a multifaceted amalgamation of ancient medical traditions, primarily rooted in Greco-Roman, Persian, Indian, and pre-Islamic Arabian medical knowledge, and has been shaped by Islamic principles and ethical considerations.[2] The newly formed empire witnessed a tremendous territorial expansion. By the end of the 7th century, it extends from Trans-Oxonian provinces in Central Asia and Western borders to African continent with later addition to the territories of Iberian Peninsula and Sindh. The syncretic fusion of old medical knowledge (mainly Greco-Roman, Persian, Indian, and Chinese) enriched with new experiences of vast multicultural dominion ruled by the Umayyads, and Abbasids reshaped the medieval understanding of Medicine.[3] One of the foundational principles of Islamic medicine was the preservation and promotion of health and well-being, as guided by Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia), and prophetic teachings (Hadith) -- a concept deeply entrenched with the Quranic injunctions.[4] From Ibn Sina (Avicenna) to Ibn Rushd (Averroes), the countless number of physicians and medical scholars evolved down the centuries in Saracen world. Islamic medicine pioneered the advancements in medical education, with the establishment of hospitals, medical schools, and the creation of medical textbooks that were used as references for centuries.[5] The legacy of Islamic medicine that evolved between 8th CE and 14th CE has left an indelible mark on the global history of medicine and continues to influence healthcare practices today.[6] This review will trace the evolution of medical education and its key attributes during this time period (8th CE to 14th CE) that has been defined by scholars as Islamic Golden ages.

Historical events that impacted Islamic medical education

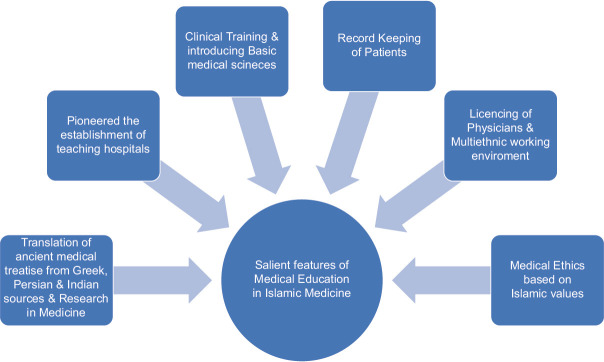

The evolution of medicine in human history can be traced thousands years back in antiquity from the time of Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Hellenic civilizations.[7] Till 5th CE, the concept of treatment centers was limited up to sanatoria or temple annexures where priest blended the care with divine interventions and drugs.[8] It was in the year 555 CE; the first established medical school along with a hospital was started in the near East by Sassanid King, Khusraw at Jundi-Shahpur, a city in the Khuzistan Province of modern Iran. This center evolved as the gathering place for the study of Persian philosophical and medicinal traditions, where Indians, Greeks, Jews, Nestorians, and Zoroastrians create the foundation for the massive medical advancement that was witnessed under the golden ages of Islamic Empire. Even, Harith bin Kalada, the physician to the Prophet Mohammed, studied in Jundi-Shapur.[9] During 7th CE, it was Umayyads who laid the ground for the advancement in health care. Jundi-Shahpur served as a model for the Islamic world and its physician served all across Damascus along with other major centers of Umayyads.[10] Creating health awareness by educating masses on personal hygiene and preventive health measures were key achievements of this period. It was an integrated model based on prophetic traditions related to health and scientific understanding of its time.[10] In 750 CE, Abbasid toppled Umayyads, and the center was shifted from Damascus to the newly founded city of Baghdad. It was during this period, a phase of scientific research was patronized by Abbasid Caliphs, especially under Harun Al Rashid, his successor Al Mamun. The Abbasid Caliphate witnessed a culture of scholarship that leads to absorption of old medical knowledge, synthesis of new ideas from diverse cultures, and laying of the foundation of medieval medical education [Figure 1]. In Iberian Peninsula, Umayyads continued to rule even after their fall in the main lands of Islam. Al Andalusia bloomed as an intellectual center and for centuries, it remained the center of studying medicine, sciences, and arts in Europe.[11] Transfusion from these vessels of learning makes inroads to Europe and laid the basis of medical scholarship in Middle Ages.[12]

Figure 1.

Smart art depicting core attributes of Islamic medicine

Key Features in Pioneering Medical Education

Translation movement and research in medicine

With the fall of the Roman empire in 5th CE, most of the remarkable works of Hellenic world related to Medicine have vanished from Western World.[5] Translations of the Medicinal treasures from antiquities from Hellenic world to Ancient Indians were patronized by Abbasids and Umayyads centered at Baghdad and Cordoba.[13] Jirjis bin Bukhtyishu, the chief physician of Jundi-Shapur was appointed as the court physician by Caliph Mansur in 762 CE.[4] From this moment to fall of Baghdad by Mongols, in 1258 CE, the translation movement prospered for the centuries. The House of Wisdom started in Library of Mamun became the center of scientific research and translations. On its zenith almost, 75 translators worked on translating manuscripts of Greek, Syriac, Aramaic, Persian, and Sanskrit into Arabic.[14] Hunyan Ibn Ishaq, a Nestorian Christian physician from Basra became a lead translator at the House of Wisdom. Treatise from Ophthalmology to systemic anatomy and physiology were compiled by Yuhanna bin Masawaiyh and Hunyan Ibn Ishaq, the first two directors of the House of Wisdom.[15] The translation movement that was started from the House of Wisdom spread all across the Islamic world and principles of Islam laid the ground for rational pursuance of scientific research. Hunyan Ibn Ishaq, Yuhanna bin Masawaiyh, Avicenna, Al Razi, Avenzoar, Abulcasis, Ibn Nafis, Mansur Ibn Ilyas and many others contributed medical treatises on diverse disciplines that continued as part of curriculum in medieval Europe for centuries.[5] The medical research continued all across Islamic world for centuries.

Establishment of hospitals

Structured hospitals were considered as a remarkable contribution of medieval Islamic world.[16] In Islamic Medicine, the word, Bimaristan has been used for hospitals; that’s a loan word taken from Persian, literally meaning, Dwellings of sick. From the time of Prophet, the use of mobile hospitals has been recorded during battles and first time used in the Battle of Trench.[8] Caliph Walid ibn Abd al-Malik was credited to establish a sanatoria for disabled and lepers in Damascus. The first free public hospital was established by Harun Al Rashid in Baghdad and then by 850 CE in Egypt. After this, the hospitals were established all across the Islamic world from Spain to Central Asia.[17] On its zenith, the Cordoba in Spain has around 50 hospitals during 10th century where some were exclusively military hospitals while others were used for clinical training. The wards were divided according to specialty such as Medicine, Surgery, Infectious disease, Mental illness and also segregated based on gender.[8] Patients from all genders, ethnicities, and religions were welcomed. Library, lecture halls, outpatient clinics, drug store, kitchen, bath, mosque, chapels, and music rooms were attached to the hospital. The patients were provided with clothes, medication, and food during the stay. The expense of managing the hospital was taken from endowments known as Waqf.[18] Al Mansuri hospital constructed at Cairo (1284 CE) was one of the largest hospitals in Islamic world with the capacity of 8000 beds.[8] Many of the centers served as teaching hospital for trainees and interns.[16,18]

Introducing basic sciences and clinical training

The Bimaristan of Islamic world served as medical schools both for residents and medical students. The foundation subjects such as anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology were taught separately.[8] Disciplines such as toxicology and chemistry were also taught as prerequisite knowledge for Physicians. The dissection was performed on animals and colored illustrations of body parts were used in teaching. Physicians like Avicenna, Rhazes, and Avenzoar were directors and deans of the medical schools.[19] The wards were used for clinical teaching and cases were documented for this purpose. The libraries affiliated with medical schools and hospitals served as learning resource for clinicians and trainees. Clinical skills, such as amputation, removal of hemorrhoids, removal of varicose veins were a part of medical curriculum. Psychotherapy, anesthesia, and ophthalmology were taught at specialty level.[19] Record keeping of the patients was the responsibility of medical students.

Licensing of physicians and work environment

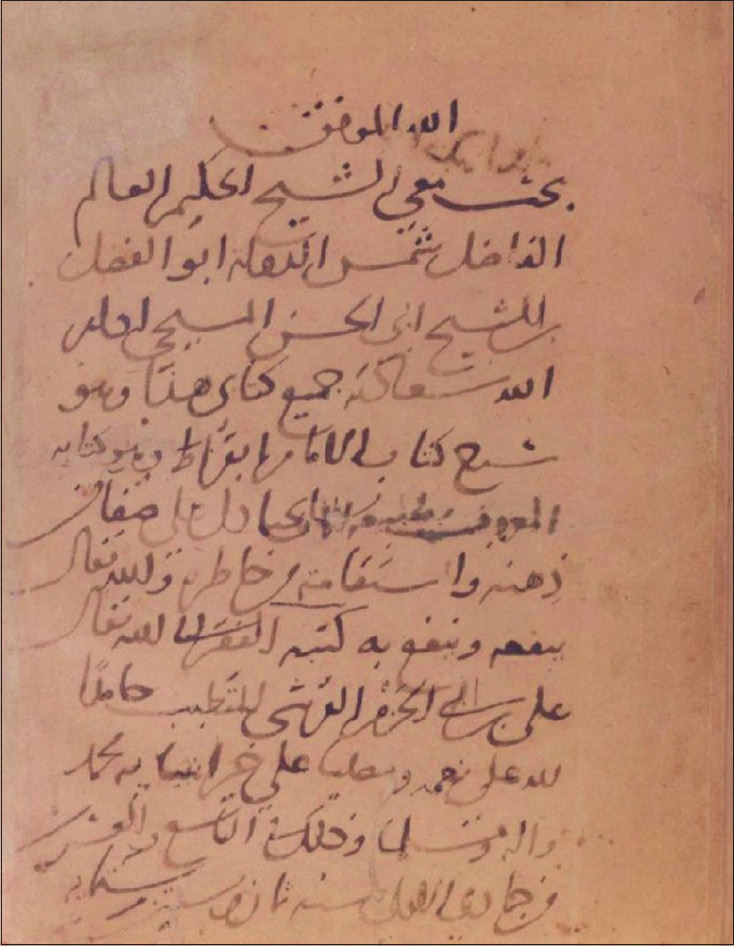

In 931 CE, one medical error leads to the death of patient in Baghdad, and results in an implementation of exit exam and licensing of the trainees by Caliph Al Muqtadir. Chief of physicians (rais-al-tibba) and public services inspector (muhtasib) worked jointly as a regulatory authority to examine the conduct of physicians. Signed certificates were issued by the physicians to attest the completion of knowledge and skills [Figure 2].[20] Physicians from diverse faith and ethnicities were appointed in the system. Arabic was the lingua franca in entire Islamic world. Students from Italy and France came to study in the schools of Cordoba in Spain.[11]

Figure 2.

The signed statement made by Ibn al-Nafis (d. 1288/687 H) that his student, a Christian named Shams al-Dawlah ibn Abi al-Hasan al-Masihi, had read and mastered Ibn al-Nafis’s commentary on a Hippocratic treatise. Source: NLM, MSA69, fol. 67b[20]

Medical ethics

Medical ethics has roots from Mesopotamian and Hellenic era but Islamic medicine draws its framework mainly on Quran and Sunnah. Ishaq bin Ali Rahawi pioneered in framing first ethical framework for physicians.[9,10] The initial work of medical ethics was derived from early Hellenic sources and got fused with Quranic principles. The famous physician al-Tabari compiled medical ethics titled Firdaws Al Hikma (Paradise of Wisdom). His code of ethics based on four attributes:

Personal character of physicians

His obligation towards physicians

His obligation towards community

His obligation towards Colleague.

CONCLUSION

The advancements in medical education during the golden age of Islam greatly influenced Europe during the late medieval period. The present healthcare and medical education system is indebted from this significant phase in human history.

Financial support and sponsorship

The author would like to thanks Deanship of Scientific Research, Majmaah University for supporting this article under project number R-2023-666.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We authors would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, Majmaah University for supporting this article under project number R-2023-666.

REFERENCES

- 1.AlRawi SN, Khidir A, Elnashar MS, Abdelrahim HA, Killawi AK, Hammoud MM, et al. Traditional Arabic &Islamic medicine: Validation and empirical assessment of a conceptual model in Qatar. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:157. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1639-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alrawi SN, Fetters MD. Traditional Arabic &Islamic medicine: A conceptual model for clinicians and researchers. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:164–9. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n3p164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber AS. Clinical applications of the history of medicine in Muslim-majority nations. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2023;78:46–61. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jrac039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahpesandy H, Al-Kubaisy T, Mohammed-Ali R, Oladosu A, Middleton R, Saleh N. A concise history of Islamic medicine: An introduction to the origins of medicine in Islamic civilization, its impact on the evolution of global medicine, and its place in the medical world today. Int J Clin Med. 2022;13:180–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edriss H, Rosales BN, Nugent C, Conrad C, Nugent K. Islamic medicine in the middle ages. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majed CP, Hassan CP. The contribution of Islamic culture to the development of medical sciences. Journal of British Islamic Medical Association. 2020;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elgood C. A medical history of Persia and the eastern Caliphate: From the earliest times until the year AD. Cambridge University Press; 1932. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AC. Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centres. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:615–7. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.12.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer H. Historical perspectives on health. Early Arabic medicine. J R Soc Promot Health. 2004;124:184–7. doi: 10.1177/146642400412400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alotaibi MJ. Achieving health security during the Umayyad Era (41-132 AH/661-750 AD) Inf Sci Lett. 2023;12:2607–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halilović S. Islamic civilization in Spain-A magnificient example of interaction and unity of religion and science. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29(Suppl 1):64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majeed A. How Islam changed medicine. BMJ. 2005;331:1486–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragab A. Translation and the making of a medical archive: The case of the Islamic translation movement. Osiris. 2022;37:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery SL. Mobilities of science: The era of translation into Arabic. Isis. 2018;109:313–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johna S. Hunayn ibn-Ishaq: A forgotten legend. Am Surg. 2002;68:497–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savage-Smith E. hospitals, Islamic cultures &medical arts, history of medicine, national library of medicine. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 15]. Available from:https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/islamic_medical/islamic_12.html .

- 17.Glubb JB. A Short History of the Arab Peoples. Hodder and Stoughton; London, U. K: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Majali SA. Contribution of medieval Islam to the modern hospital system. Historical Research Letter. 2017;43:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syed IB. Islamic medicine:1000 years ahead of its times. Journal for the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2002;2:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savage-Smith E. The arts as a profession, Islamic cultures &medical arts, history of medicine, national library of medicine. [Last accessed on 2011, Dec 15]. Available from:https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/islamic_medical/islamic_13.html .