ABSTRACT

Cemento-osseous dysplasia is a subgroup of fibro-osseous dysplasia commonly invading the tooth-bearing regions of the mandible quite often. These bony pathologies are asymptomatic and are seen on radiographs as an incidental finding. Accurate diagnosis of periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia is very crucial as it will help in the proper management of the patient as the incorrect diagnosis can lead to the unnecessary endodontic treatment of the concerned teeth as it may be misdiagnosed as a periapical pathology. We describe a case of periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia in which a 52-year-old woman had been experiencing discomfort in the right mental area of her mandible for the previous 6 months and had finally sought help at the outpatient department. This case study aims to highlight the significance of making an accurate diagnosis of cemento-osseous dysplasias in the tooth-bearing area.

KEYWORDS: Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), osteoblast, periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia

INTRODUCTION

Occurs when fibrous tissue and metaplastic bone replace normal bone in the periapical tooth region and is considered a reactive and non-neoplasic process.[1] Cementum’s periapical dysplasia is also known as periapical cemental dysplasia, focused cement-osseous dysplasia, periapical osseous dysplasia, periapical cementoma, and periapical osseous dysplasia.[2,3,4] Tooth-bearing regions often exhibit cemento-osseous dysplasias, a kind of fibro-osseous illness. benign cancers of the skeletal system[5,6]

The previous WHO guidelines were modified by Su et al. (1997) proposing the use of the term focal osseous dysplasia for lesions occurring in the anterior mandible, other parts of the maxilla and mandible, Florid OD for similar lesions involving more than one quadrant in the jaws.[7,8,9]

Clinically periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia is an asymptomatic entity, rarely pain presented by the patient. It is most commonly seen in the anterior mandible. These osseous lesions typically show up on X-rays as a radiolucent mass in the apical regions of teeth during the osteolytic phase, a radiolucent and radiopaque mass during the blastic phase, and an osteogenic radiopaque mass with a radiolucent peripheral ring during the final stage of the lesion’s progression.[1]

We provide a case with periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia, complete with a CT scan and a discussion of the pathology.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old woman came into the OPD because she’d been experiencing discomfort in the right mandibular mental area for the last six months. Medical records for the patient turned up nothing. Examination of the whole body revealed no signs of illness, and probing of the lymph nodes revealed no abnormalities. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy or any other related disorders in the extra-oral examination. On intra-oral examination no swelling was evident. Tenderness on vertical percussion was positive with respect to 43 44. No swelling was evident in association with 43 and 44.

Based on patient’s case history and clinical examination diagnosis of a periapical lesion was made.

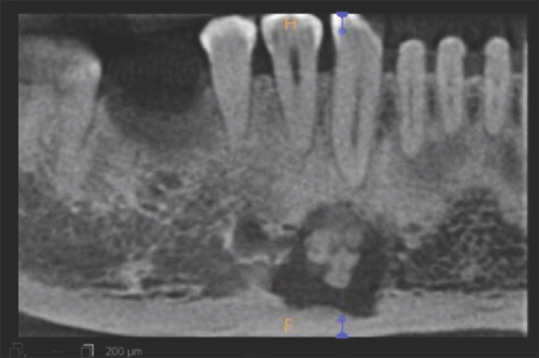

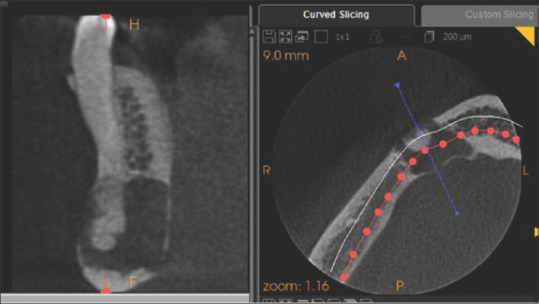

Patient was advised cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) a radiographic investigation. CBCT revealed a mixed radiolucent and radiopaque lesion at the root apice with respect to 33. As shown in Figure 1, perforation of buccal and lingual cortical plate is seen with respect to the 33-tooth region as seen in the axial and sagittal cross section [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Showing Panoramic reconstructed image showing mixed radiolucent radiopaque lesion

Figure 2.

Showing perforation of buccal and lingual cortical plate

Excisional Biopsy revealed a mixture of gritty bone-like material within an empty cavity with soft tissue lining.

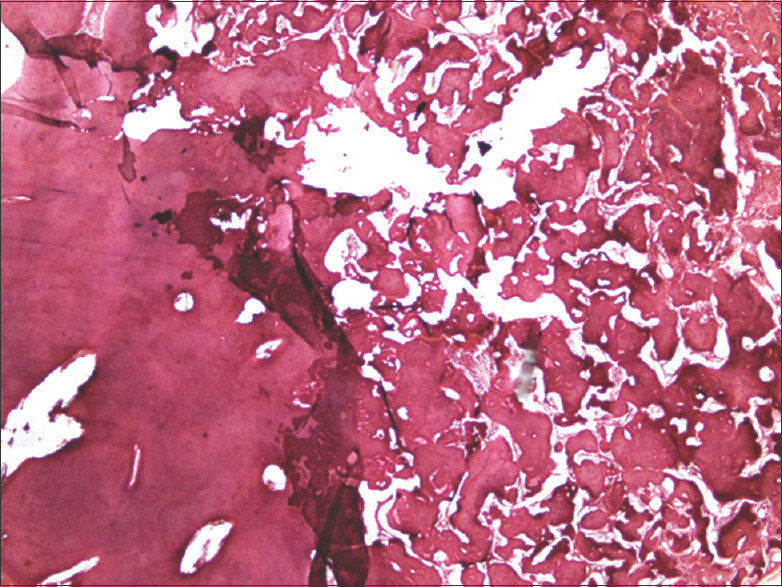

Lesional tissue consists of epithelium and underlying connective tissue stroma, as shown in a 4×: H and E stain scanning image [Figure 3]. It shows a cystic lumen walled with thin, non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium with fibro cellular connective tissue capsule including collagen fiber bundles, mild to moderate fibroblasts, endothelial-lined blood vessels, and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration suggestive of possible periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia.

Figure 3.

Showing H & E-stained section (4× Power view)

DISCUSSION

In maxillofacial complexes, periapical fibro-osseous lesions are rare but sometimes misinterpreted and mistreated as illness. To avoid this, general dentists need radiological and clinical knowledge. Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia is more common in the anterior jaw. Teeth-dominated area. Middle-aged women suffer the most.[10,11,12,13,14]

Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia has three radiographic stages: Phase I Stage II osteolysis begins with a radiolucent lesion in the apical part of a tooth’s root. Phase III, the mature stage, comprises a well-defined dense radiopaque zone surrounded by a radiolucent halo and a mixed radiolucent radiopaque structure with nodular radiopaque deposits. The periodontal ligament now separates the lesion from the root.[15,16,17,18] This periapical cemento-osseous lesion may progress over months or years.

CBCT helps diagnose periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia by showing the lesion’s location, extent, and influence on the tooth’s cortical plates and root apices.[14,19,20] The buccal and lingual cortical plates resorbed in this example, making CBCT scans invaluable. Periapical and panoramic imaging cannot detect this unusual radiographic abnormality. The CBCT scan showed a mixed radiolucent radiopaque lesion at the root apices w.r.t 33 with a radiolucent halo at the periphery.

CONCLUSION

When diagnosing periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia, the stage is crucial. Phase III lesions may have cemento-ossifying fibroma, Paget disease, chronic osteomyelitis, or cementoma. This condition made 2D image diagnosis challenging. We used cutting-edge 3D imaging for radiographic diagnostics. Histological results helped make a definitive diagnosis in this case. Exam, histology, and radiography determined the diagnosis. Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia has no treatment, only clinical and radiological surveillance. However, the patient’s aggressive conduct required an excisional biopsy for diagnosis and surveillance.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brannon RB, Fowler CB. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: A review of current concepts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:126–43. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melrose RJ. The clinicopathologic spectrum of cemento-osseous dysplasia. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1997;9:643–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slootweg PJ. Bone diseases of the jaws. Int J Dent 2010. 2010:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2010/702314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slootweg PJ. Lesions of the jaws. Histopathology. 2009;54:401–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JM. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: Odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:68–77. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald DS. Maxillofacial fibro-osseous lesions. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su L, Weathers DR, Waldron CA. Distinguishing features of focal cemento-osseous dysplasia and cemento-ossifying fibromas. II. A clinical and radiologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:540–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su L, Weathers DR, Waldron CA. Distinguishing features of focal cemento-osseous dysplasias and cemento-ossifying fibromas: I. A pathologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:301–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eskandarloo A, Yousefi F. CBCT findings of periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia: A case report. Imaging Sci Dent. 2013;43:215–8. doi: 10.5624/isd.2013.43.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramovitch K, Rice DD. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60:167–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Noronha Santos Netto JN, Cerri JM, Miranda AMMA, Pires FR. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: Clinicopathologic features from 143 cases diagnosed in an oral diagnosis setting. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:e56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad M, Gaalaas L. Fibro-osseous and other lesions of bone in the jaws. Radiol Clin North Am. 2018;56:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavalcanti PHP, Nascimento EHL, Pontual MLA, Pontual AA, Marcelos PGCL, Perez DEC, et al. Cemento-osseous dysplasias: Imaging features based on cone beam computed tomography scans. Braz Dent J. 2018;29:99–104. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. St. Louis, USA: Mosby; 2002. Bone lesions. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senia ES, Sarao MS. Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia: A case report with twelve-year follow-up and review of literature. Int Endod J. 2015;48:1086–99. doi: 10.1111/iej.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo SB. Central cemento-ossifying fibroma: Primary odontogenic or osseous neoplasm? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:S87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mainville GN, Turgeon DP, Kauzman A. Diagnosis and management of benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws: A current review for the dental clinician. Oral Dis. 2017;23:440–50. doi: 10.1111/odi.12531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heuberger BM, Bornstein MM, Reichart PA, Hürlimann S, Kuttenberger JJ. Periapical osseous dysplasia of the anterior maxilla: A case presentation. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2010;120:1001–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigues CD, Estrela C. Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia in maxillary teeth suggesting apical periodontitis: Case report. Gen Dent. 2009;57:21–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]