Abstract

Background:

Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches (CIHA), including but not limited to, natural products and Mind and Body Practices (MBPs), are promising non-pharmacological adjuvants to the arsenal of pain management therapeutics. We aim to establish possible relationships between use of CIHA and the capacity of descending pain modulatory system in the form of occurrence and magnitude of placebo effects in a laboratory setting.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study investigated the relationship between self-reported use of CIHA, pain disability, and experimentally induced placebo hypoalgesia in chronic pain participants suffering from Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD). In the 361 enrolled TMD participants, placebo hypoalgesia was measured using a well-established paradigm with verbal suggestions and conditioning cues paired with distinct heat painful stimulations. Pain disability was measured with the Graded Chronic Pain Scale, and use of CIHA were recorded with a checklist as part of the medical history.

Results:

Use of physically oriented MBPs (e.g., yoga and massage) was associated with reduced placebo effects (F1,2110 44 = 23.15, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.171). Further, linear regressions indicated that greater number of physically oriented MBPs predicted smaller placebo effects (β = −0.17, p = 0.002), and less likelihood of being a placebo responder (OR = 0.70, p = 0.004). Use of psychologically oriented MBPs and natural product were not associated with placebo effects magnitude and responsiveness.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that use of physically oriented CIHA was associated with experimental placebo effects possibly through an optimized capability to recognize distinct somatosensorial stimulations. Future research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying placebo-induced pain modulation in CIHA users.

Significance:

Chronic pain participants who use physically oriented mind-body practices, such as yoga and massage, demonstrated attenuated experimentally induced placebo hypoalgesia in comparison with those who do not use them. This finding disentangled the relationship between use of complementary and integrative approaches and placebo effects, providing the potential therapeutic perspective of endogenous pain modulation in chronic pain management.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain is a prevalent and, at times, debilitating condition that results in suffering from significant personal and societal burden (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2020). Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a particular set of chronic pain conditions that involve dysfunction of the complicated temporomandibular joint and/or mastication muscles, which can lead to chronic pain, affecting 5%−12% of the general population (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2020). Moreover, there is no standard form of treatment that makes TMD difficult for clinicians to treat thus furthering the perspective of endorsing endogenous pain modulation (Clark et al., 2016; Mogil et al., 1996; Pecina & Zubieta, 2015;Tchivileva et al., 2020) with Complementary and Integrative Health Approaches (CIHA) (Phutrakool & Pongpirul, 2022).

CIHA have been gaining popularity and are used either in substitution or in conjunction with conventional medicine (Ernst, 2022; Reddy & Fan, 2022). These approaches consist of a wide array of treatments that can be categorized by their mode of delivery such as Mind and Body Practices (MBPs, e.g., relaxation techniques, yoga, etc.), natural products (e.g., valerian root, ginseng, etc.), and others (e.g., Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine) (Chen & Michalsen, 2017; Garland et al., 2019). It should be noted that there is a lack of strong evidence supporting CIHA efficacy (Arienti, 2021; Boyd et al., 2019; Wieland et al., 2022) and many studies on CIHA have relatively low quality, producing inconclusive findings (Wieland et al., 2022). One point of view on the efficacy of CIHA is that its impact on pain relief might be due to placebo mechanisms (Kaptchuk, 2002), which are improvements in symptoms that are triggered by psychosocial contexts rather than an active component. The placebo effect is not simply a bias but a phenomenon that involves distinct neurobiological and physiological mechanisms, such as the activation of descending pain modulatory systems and the release of neural substances like endogenous opioids, oxytocin, and vasopressin (Colloca, 2019b; Zunhammer et al., 2021). Since placebo effects can be considered a proxy of endogenous descending pain modulation, it is plausible that CIHA may work, at least in part, through placebo mechanisms. If CIHA and placebo share similar psychological and physiological mechanisms, then the use of CIHA might link to the magnitudes and responsiveness of placebo effects. However, there is still insufficient empirical evidence disentangling the relationship between CIHA and placebo hypoalgesia.

To address this gap, we aimed at investigating the relationship between use of CIHA and placebo effects given the potential therapeutic prospective of endogenous pain modulation in chronic pain management (Bannister & Hughes, 2022). It should be noted that efficacy of CIHA is beyond the scope of this study. We adopted a cross-sectional study design to determine the relationship between self-reported use of CIHA and occurrence and responsiveness to experimentally induced placebo hypoalgesic effects.

2 |. METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study design in which participants went through an experimental placebo manipulation and completed a CIHA checklist as part of medical history. The study was conducted from August 2016 to February 2020 at the University of Maryland School of Nursing Clinical Suites and University of Maryland School of Dentistry Brotman Orofacial Pain Clinic. The participants were recruited from the Baltimore area. We adopted a community-based recruitment strategy where flyers and advertisement were posted in dental clinics, pain management clinics, newspapers, local blogs and archives, restaurants and stores that have public bulletins, public transportation, social media including twitter, Instagram, Facebook, as well as academic fairs, music/art festivals, and health fairs. All participants provided both verbal and written consent for participating in the current study. This study was approved by the University of Maryland institutional review-board (IRB Protocol # HP-00068315) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles (World Medical, 2013). The study’s methodological approach and results were reported in accordance with the guidelines for cross-sectional study following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007; von Elm et al., 2008).Participants were compensated for their time ($100). The current study is part of a larger project that aimed to examine the role of genetic, cognitive-emotional factors in influencing endogenous modulatory systems in chronic orofacial pain population. Findings from this project have been published elsewhere determining the influences of learning (Wang et al., 2020) and expectations (Colloca et al., 2020), sex (Olson et al., 2021), race (Okusogu et al., 2020), and psychological factors (Wang et al., 2022) on placebo effects.

2.1 |. Study population

To avoid selection bias, we adopted a community-based recruitment strategy where participants were enrolled from the greater Baltimore area, Maryland State and other nearby states. We screened 421 chronic pain participants who were primarily diagnosed with TMD and 409 of them were enrolled in the study with 7 being lost to the follow-up (see flow chart in the Appendix S1). A total of 402 were successfully enrolled and completed the placebo procedure. And 361 out of 402 completed the survey with a response rate of 89.8%. The remaining 41 participants had missing data and were removed from the data analyses.

The inclusion criteria included TMD duration longer than 3 months and ages between 18 and 65. All potential participants were screened by telephone first before being screened in person by a trained TMD examiner at the University of Maryland School of Dentistry, the Brotman Orofacial Clinic to confirm the TMD diagnosis and related phenotypes. The trained, experienced examiner used the Axis I Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) to make the research diagnosis of TMD (Schiffman et al., 2014). For each participant, a physician examined their medical history, current health, and comorbidities (e.g., overlapping chronic pain conditions, and any other systemic or localized diseases).

The exclusion criteria included a history of neurological, cardiovascular, or pulmonary disorder; degenerative muscular, kidney, or liver disease; cancer within the past 3 years, certain types of colour blindness; uncorrected impaired hearing; facial trauma; cervical pain due to stenosis or radiculopathy; or were breast feeding at the time. Participants that indicated that they suffered from severe psychiatric diseases, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, reported dependence on or abuse of alcohol or drugs were also excluded from the study after consultation with a licensed expert psychiatrist.

2.2 |. Clinical pain assessment

TMD pain was assessed using the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) (Dixon et al., 2007). The GCPS contained 3 items assessing characteristic pain intensity and 3 items assessing pain interference. The characteristic pain intensity items assessed the participant’s levels of current pain, worst pain, and average pain during the last 30 days from 0 (no pain) to 100 (pain as bad could be). TMD characteristic pain intensity was then derived from the 3 pain intensity questions, calculating as the mean of ‘pain right now’, ‘worst pain’ and ‘average pain’ multiplied by 10. TMD characteristic pain intensity ranges from 0 to 100 with a greater number representing a higher level of TMD pain intensity ratings. The pain interference items asked about to what extent the participant’s pain interfered with their usual daily activities, social activities, and work activities on a scale from 0 (no interference) to 10 (unable to carry on any activities). The average rating of the 3 interference items multiplied by 10 was calculated as an index for pain interference, resulting in a range from 0 to 100 following the scoring criteria (Dixon et al., 2007).

2.3 |. Complementary health approaches

Participants filled out a CIHA checklist that we developed by adopting the definition from National Center of Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) classification to track the use of complementary and integrative medicine. Participants were asked about their use of CIHA in the form of checkbox answer choices (yes or no) (the Appendix S1 for CIHA questionnaire) as part of medical history and sociodemographic information. Based on the NCCIH classification (https://www.ncdh.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name), CIHA can be divided into 3 main categories: (1) physically oriented mind-body practices (MBPs, e.g., yoga, massage, acupuncture, reiki), (2) psychologically oriented mind-body practices (e.g., breathing, mindfulness meditation, relaxation, CBT), and (3) natural products (e.g., vitamins, probiotics, minerals, ginseng, valerian root, turmeric, St. John’s wort, kava) (Chen & Michalsen, 2017; Garland et al., 2019). Physically oriented MBPs prioritized physical techniques to alleviate pain whereas psychologically oriented MBPs adopted primarily mental techniques to reduce pain (Garland et al., 2019). Sociodemographic factors including sex, age, race, socioeconomic status, marital status, and educational level were also assessed.

2.4 |. Heat pain sensitivity assessment and calibration

Upon arrival, each participant went through a pain sensitivity test using the limits paradigm (Fruhstorfer et al., 1976; Nielsen et al., 2005) which assessed warmth threshold, pain threshold, medium pain level, and maximum pain tolerance in an ascending manner. The heat stimulations were delivered using the PATHWAY Pain and Sensory Evaluation System (Medoc Advanced Medical Systems) with a 3 × 3 cm ATS thermode. The thermode was applied to participant’s ventral forearm of the dominant hand. The stimulations were delivered at the same location for each trial to prevent issues stemming from regional variation in sensitivity.

The heat simulations started from 32°C and gradually increased with an increasing rate of 0.3°C/s. The participants were given a remote control (stop) button and were told to press the stop button when they first detected warm, minimal heat pain (heat pain threshold), medium level of heat pain, and maximum level of heat pain (heat pain tolerance). Each of these four measurements including warmth, heat pain threshold, medium, and heat pain tolerance was assessed four times. During these assessments, participants were instructed to rate their pain using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), with 0 = no pain and 100 = maximum tolerable pain. The VAS rating served as a way to facilitate interaction with the experimenter and, when appropriate, the cessation of the stimulations. The average temperature of the four maximum pain tolerance was then used to determine the participant’s heat intensity levels in Celsius degree for the following conditioning and testing phases of the experimental placebo procedures.

2.5 |. Experimental placebo manipulation

The placebo manipulation followed the pain sensitivity assessment and consisted of a well-established and validated paradigm of conditioning and verbal suggestion for placebo manipulation (Colloca et al., 2020; Okusogu et al., 2020; Olson et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022).

The placebo procedure included one conditioning phase (24 trials with 12 red and 12 green screens) and one testing phase (12 trials with 6 red and 6 green screens). In the conditioning phase, a red screen was paired with a high heat temperature which was primarily set as 2°C lower than the participants’ average maximum tolerance temperature, and the green screen was paired with a low heat temperature that was primarily set to 6°C lower than the participants’ average maximum tolerance temperature. In this way, the participant learned the associations between high pain experience with red screen cue, and low pain experience with green screen cue. In the testing phase, without informing the participants, the temperatures for the red and green screens were switched to the same temperature which was 1°C lower than the red screens from the conditioning phase. The temperatures for red and green screens were also confirmed with subjective VAS ratings, with the greens screen corresponding to around 20 and the red screen corresponding to around 80 out of 100 VAS ratings. Participants were instructed to rate their pain experience using a 0–100 VAS scale with 0 = not pain at all to 100 = maximum tolerable pain. Any differences in pain ratings between the red and green screens during the testing phase were operationalized as the magnitude of placebo hypoalgesic effects.

At the outset, participants were told that the goal of the study was to examine the efficacy of a new pain intervention presented as a Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) (in reality it was a sham electrode with no delivery of any electrical stimulation) which would reduce pain experiences by sending a subthreshold pulse to the nerves under the skin. The underlying mechanism was the gate theory, which posited that a non-painful stimulation could inhibit the pain signal travelling from peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system. The sham TENS electrode was applied above the ATS thermode location to the ventral forearm of the dominant hand. Participants were further told that the sham TENS electrode would be turned on and off randomly. When the screen of the laptop was green, the sham electrode was turned on, and when the screen was red, the electrode was turned off (Figure 1). Each colourful screen was paired with continuous heat pain stimulation, which lasted for 10 s. At the offset of the screen, a 0 (no pain) to 100 (maximum pain) VAS scale was displayed for 8 s for participants to rate their pain experiences for each trial. The interstimulus-interval was set between 10 to 13 s. To rule out the potential sequence effects of the trials and minimizing the confounding effects of pain habituation effects, red trials and green trials were displayed in a randomized order. Specifically, we generated four random sequences and participants were randomly assigned to one of four random sequences.

FIGURE 1.

Placebo manipulation. A calibration was completed to tailor painful stimuli to the individual sensitivity. Participants then entered a conditioning phase with delivery of non-painful and painful stimuli to make them believe that a TENS would have reduced their painful sensation. The TENS (sham) electrode was applied to the dominant arm. Participants were told the activation of the TENS electrode was activated would have reduced their painful sensation. Afterwards a testing phase was conducted with pairing both red and green screens to a moderate heat painful stimuli to assess for individual placebo effects. Placebo effects were operationally defined as the reduction in pain reports between red- and green-paired stimuli. Pain was assessed by means of a VAS with “no pain” and “maximum pain tolerable” as anchors. TENS, Trans Electrical Nerve Stimulation; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

2.6 |. Expectation assessment

We adapted the Credibility/Expectancy questionnaire (CEQ) (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) to assess pain relief expectations of TMD participants. The original CEQ (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) contains three items of treatment credibility assessments and three items of treatment expectation measurements. The current study used the three items of expectation measurements including one item for cognitively based expectations (“by the end of the therapy, how much improvement in your symptoms do you think will occur?”) and two items for affectively based expectations (e.g., “At this point, how much do you really feel that therapy will help you to reduce your symptoms?” “By the end of the therapy, how much improvement in your symptoms do you really feel will occur?”). The sum scores were calculated to represent the levels of cognitively based expectations (ranging from 0 to 10) and affectively based expectations (ranging from 0 to 20). The reliability coefficient of the three items were acceptable with Cronbach’s α=0.676.

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of this study were the magnitude of placebo hypoalgesia and the placebo responsiveness (i.e., placebo responders vs. non-responders) in TMD participants. The secondary outcome was the TMD pain intensity and pain interference assessed by GCPS tool (Dixon et al., 2007). Two authors ran all analyses independently and cross-checked the results.

The power analysis was conducted based on the primary outcome placebo hypoalgesia. No previous studies have examined how the use of CIHA could be related to placebo effects. However, some posited that mindfulness, a specific type of CIHA, might rely on a different neurobiological mechanism than placebo effects (Zeidan et al, 2015). Therefore, we assumed a small effect size Cohen’s f = 0.18 for the main effects of the use of CIHA on placebo hypoalgesia. The power analysis indicated we would need a minimum of 348 TMD participants including at least 87 participants for each of the subgroup of those who were using or not using CIHA, to reach 0.8 statistical power at an alpha level of 0.05. Therefore, the final dataset of 361 participants would have sufficient statistical power to detect a small effect of CIHA use on the placebo hypoalgesia. Power analysis was conducted using G*Power software (Faul et al, 2007).

2.7.1 |. CIHA and placebo hypoalgesia

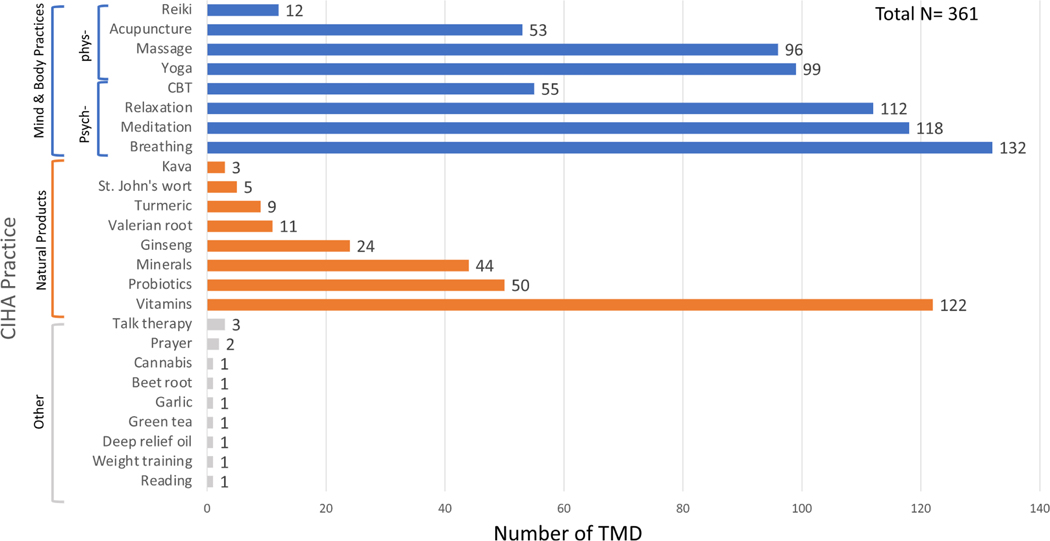

The statistical analyses were limited to three types of CIHA following the classification of NCCIH, namely, the use of physically oriented MBPs, psychologically oriented MBPs, and the use of natural products (Figure 2). In addition to the three types of CIHA, specific CIHA including use of vitamins, probiotics, minerals, breathing techniques, meditation, relaxation, yoga, massage, cognitive behavioural therapy, acupuncture were examined because all of the aforementioned CIHA had been used by at least 50 participants. Finally, because one individual may use multiple CIHA, we calculated the number of physically oriented, psychologically oriented MBPs and natural products used for each participant. Given that only a small number of participants reported using other CIHA (n = 10), other type of CIHA was excluded from the analysis. Analyses and results regarding general use of CIHA and placebo effects are reported in Appendix S1.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of CIHA therapies used by TMD participants. Of the three CIHA categories, the most commonly used was MBPs followed by natural products. Few people reported using other CIHA. The most commonly used psychologically oriented MBPs included breathing exercises, meditation, relaxation techniques, and cognitive-behavioural therapies. The most commonly used physically oriented MBPs included yoga, massage therapy, acupuncture, and reiki. The most commonly used natural produces included vitamins, probiotics, and minerals. The colour orange indicates the CIHA is a natural product. Blue colour indicates it is a mind body practice, and green colour indicates it is in the other category. Frequencies of the CIHA using were presented for each CIHA categories. Colour image is available online only at the Psychosomatic Medicine web site.

Any sociodemographic variables (i.e., age, sex, race, educational levels, marital status, annual income) and clinical variables (i.e., TMD pain duration [less vs. more than 5years], existence of chronic overlapping pain conditions, COPCs (Maixner et al., 2016), and use of pain medications) that were significantly different between CIHA users and CIHA non-users were treated as covariates. Independent t tests were conducted on the continuous variables and chi-square analyses were conducted on the categorical variables. According to these preliminary analyses, individual sex, race, educational level, TMD duration and use of conventional medicines were set as covariates in the main analyses (see Table SI).

First, we examined whether use of the three types CIHA would change the level of experimental placebo hypoalgesia while controlling for individual variabilities in socio-demographic variables and chronic pain intensity. The magnitude of placebo hypoalgesia was operationalized as the 6 trials of red-minus-green pain intensity ratings differences scores during the testing phase. LMMs were built with the 6 trials of delta scores as the dependent variable. TMD pain intensity was set as a covariate together with the pre-identified socio-demographic variables. The physically oriented MBPs (yes or no), psychologically oriented MBPs (yes or no), and use of natural products (yes or no), were treated as the fixed factors in separate LMM. Similar LMMs were also adopted for each CIHA including use of vitamins, probiotics, minerals, breathing techniques, meditation, relaxation, yoga, massage, cognitive behavioural therapy, acupunctures, and their relationships with placebo effects following the best practice and guidelines for subgroup analyses (Sun et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2007). To account for multiple comparison problems, Bonferroni corrections were applied to adjust the p-value for the pair-wise comparisons in the LMMs.

In terms of placebo responsiveness, we identified participants as responders or non-responders to the placebo manipulation using a permutation test (Colloca, 2019a; Vachon-Presseau et al., 2018). The permutation test was performed on the 6 red and 6 green trials of pain ratings for each participant. In detail, a difference score of red minus green pain ratings of an individual was calculated as . The null hypothesis is that both red and green trial ratings were from the same population. Under this null hypothesis, 6 red ratings and 6 green ratings were pooled together, and a 1000 times random resampling was performed to create a new distribution of red minus green difference scores ratings. Two-sided p values were determined based on the proportions of resampled permutations in which the absolute difference was larger than . In other words, a participant was classified as placebo responder if the pain ratings for 6 green trials were significantly lower than pain ratings for the 6 red trials. The remaining participants were classified as placebo non-responders. Chi-square tests were conducted to determine if the different types of CIHA, including physically, psychologically oriented MBPs, and the use of natural products may have been related to being a placebo responder or non-responder.

Finally, we ran hierarchical regression analyses to determine whether the number of physically, psychologically oriented MBPs, and natural product usages affected the magnitude of placebo hypoalgesia (linear regression) and rate of responsiveness (logistic regression). Sex, race, educational level, TMD duration, use of conventional medicines, and TMD pain intensity were entered in block 1 to be used for controlling purposes, while number of physically, psychologically oriented MBPs, and natural product usages were entered in block 2, respectively. In order to avoid biased parameter estimates and arbitrary selections of predictor variables, we adopted a full model instead of step-wise algorithm (Smith, 2018).

2.7.2 |. Expectation as mediators in driving the effect of CIHA on placebo hypoalgesia

We examined if pain relief expectations would mediate the effects of CIHA on placebo hypoalgesia. Bivariate Pearson correlation matrix was first calculated among placebo hypoalgesia, use of physically oriented MBPs, use of psychologically oriented MBPs, use of natural products as well as the cognitively based and affectively based expectations. Variables that were significantly correlated to placebo hypoalgesia entered the mediation model.

For the mediation model, the number of physically oriented MBPs used was set as the independent variable (X). Placebo hypoalgesia, defined as the average pain ratings of red trials minus green trials, was set as the dependent variable (Y). Pain relief expectation was set as the mediator. We used a bias-corrected bootstrapping method (5000 times resampling) to determine the indirect effects. When the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval (BCI) did not include zero, the indirect effect was considered to be significant (Hayes, 2017).

2.7.3 |. CIHA and chronic pain

LMMs were conducted with the use of the three different types of CIHA [i.e., physically oriented MBPs (yes or no), psychologically oriented MBPs (yes or no), and natural products (yes or no)], as well as specific CIHA treated as the fixed factors on chronic pain intensity and interference. We also performed two hierarchical regressions with the number of CIHA uses as predictor (Block 2) and chronic pain intensity/interference as dependent variables while controlling for sex, race, educational level, TMD duration and use of conventional medicines (Block 1).

Finally, we expanded our analyses to the subgroup of TMD participants that reported using any CIHA together with any pharmacological pain therapeutics or not (exploratory analyses). We classified the TMD participants into those who were using CIHA together with pharmacological pain therapeutics (n = 241) and those who were using CIHA in place of pharmacological pain therapeutics (n = 34). We compared those two groups in terms of experimental placebo hypoalgesia and chronic pain intensity/interference using LMMs.

To quantify the magnitude of the effects of CIHA on placebo hypoalgesia, effect size Cohen’s d was calculated whenever a significant CIHA group difference was found. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM). The mediation analysis was conducted via PROCESS macro implemented in SPSS version 27. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was set as the level of significance.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Population characteristics

The participants were mostly women (77%), White (52%) and African American/Black (34%) participants, who at least completed high school (100%), with an average aged of 41.25 (SEM = 0.75)years (Table 1). Chronic pain intensity was moderate, equal to 47.7 (SEM = 1.14) on a range from 0 (=no pain) to 100 (=maximum pain severity) and pain interference was 27.2 (SEM = 1.44, range: 0 = no interference −100 = unable to carry on any activities).

TABLE 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical variables of TMD participants (n = 361).

| TMD participants | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 41.25 (14.21) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Women | 279 (77.28) |

| Men | 82 (22.72) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 20 (5.54) |

| Non-Hispanic | 332 (91.97) |

| Unknown | 9 (2.49) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Native American | 1 (0.28) |

| Asian | 25 (6.93) |

| African-American/Black | 122 (33.80) |

| White | 187 (51.80) |

| Mixed | 26 (7.20) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Completed high school | 43(11.92) |

| Some college | 92 (25.48) |

| College graduate | 130 (36.01) |

| Professional or post-graduate level | 96 (26.59) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married/living as married | 93 (25.76) |

| Divorced | 52 (14.40) |

| Separated | 10 (2.77) |

| Widowed | 12(3.33) |

| Never married | 194 (53.74) |

| Annual income, n (%) | |

| $0-$19,999 | 78 (21.60) |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 69(19.11) |

| $40,000–859,999 | 57(15.79) |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 42 (11.64) |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 33 (9.14) |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 47(13.03) |

| $150,000 or higher | 31 (8.59) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 28.47 (7.17) |

| Chronic pain severity, mean (SD) | 47.73 (21.70) |

| Chronic pain interference, mean (SD) | 27.16 (27.23) |

| TMD duration, mean (SD), months | 145.08 (130.76) |

Self-reported use of CIHA was common, with 76.2% of participants reporting some form of CIHA use. Of the three CIHA categories outlined above, the most used was psychologically oriented MBPs (n = 191, 52.9%) followed by physically oriented MBPs (n = 162, 44.9%), and natural products (n = 149, 41.3%). Only 10 participants reported using other CIHA (n = 10, 2.8%, see word cloud in Figure SI of Appendix S1). The most commonly used MBPs included breathing exercise (n = 132, 36.6%), meditation (n = 118, 32.7%), relaxation techniques (n = 112, 31.0%), yoga (n = 99, 27.4%), massage therapy (n = 96, 26.6%), cognitive-behavioural therapy (n = 55,15.2%), and acupuncture (n = 53,14.9%). The most used natural products included vitamins (n = 122, 33.8%), probiotics (n = 50, 13.9%), and minerals (n = 44,12.2%) (Figure 2).

Regarding the socio-demographic distributions, a significantly higher percentage of women reported using CIHA (n = 221, 79.2%) than men (n = 50, 65.9%, χ2 = 6.23, p = 0.013). African-American/black participants were less likely to report use of CIHA (n = 76, 62.3%) than non-African-American/Black participants (n = 195, 83.3%, χ2 = 19.57, p< 0.001). TMD participants with a higher educational level (n = 184, 81.4%) were more likely to report use of CIHA than those with a lower educational level (n = 87, 67.4%, χ2 = 9.14, p = 0.003). In terms of clinical factors, those who had a TMD duration at least 5 years were more likely to use CIHA (n = 200, 80.0%) than those who had a shorter TMD duration (n = 71, 67.0%, χ2 = 6.94, p = 0.008). TMD participants who have been using conventional medicines to treat pain were also more likely to use CIHA (n = 241, 78%) than those who did not use conventional medicines (n = 30, 65.4%, χ2 = 3.90, p = 0.048). Therefore, sex, race, educational level, TMD duration and use of conventional medicines were treated as covariates in the main analyses. Socio-demographic distributions about MBPs and natural products usage are reported in Appendix S1.

3.2 |. CIHA and placebo hypoalgesia

TMD participants using physically oriented MBPs showed slightly reduced placebo hypoalgesic effects (mean = 16.38, SEM = 0.71) compared to those who did not (mean = 21.04, SEM = 0.64, F1,2110.44 = 23.15, p< 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.171, Figure 3a). Use of natural pain products (F1,2112.11 = 0.17, p = 0.68) or use of psychologically oriented MBPs (F1,2111.96 = 0.35, p = 0.56) were not significantly associated with placebo hypoalgesia. Given that adding covariates may add unknown pathways between covariates and main effects that might contribute to biased estimates, we further confirmed the findings without adding the covariates to the model. Controlling or not controlling for the covariates did not change the findings (see Appendix S1).

FIGURE 3.

CIHA types and placebo hypoalgesia. (a) Physically oriented MBPs reduced experimental placebo hypoalgesic effects. TMD participants who were using physically oriented MBPs such as yoga, massage, acupuncture or reiki, had significantly lower placebo hypoalgesia compared to those who were not using. This result was independent of age, sex, race, TMD pain duration, educational and income levels. ***p < 0.001. (b) Number of MBPs and placebo hypoalgesia. MBPs number predicted reduced placebo hypoalgesia. Blue bar represented the mean and standard error of placebo hypoalgesia for each number of MBPs. Data were presented as regression line with 95% confidence interval shown in crimson. (c) Use of yoga and placebo hypoalgesia. TMD participants using yoga exhibited reduced placebo hypoalgesia compared to those who did not. (d) Use of massage and placebo hypoalgesia. TMD participants using massage exhibited reduced placebo hypoalgesia compared to those who did not. Data were presented with medium, quartiles, minimal and maximum. Each dot represented individual placebo hypoalgesia. ***p < 0.001.

We also found that use of a greater number of physically oriented MBPs was associated with smaller magnitude of placebo effects (β = −0.17, p = 0.002, Figure 3b) after controlling for sex, race, TMD duration, TMD intensity and use of pharmacological treatments. No significant association was observed in terms of the number of psychologically oriented MBPs (β = −0.06, p = 0.28) or the number of natural products (β = −0.07, p = 0.21). These results were also independent of individual variability in heat painful sensitivity as revealed by non-significant bivariate correlations of the number of physically oriented MBPs with heat painful threshold (Pearson r = −0.03, p = 0.551) and with heat painful tolerance (Pearson r= −0.02, p = 0.728).

Among specific CIHA, TMD participants using Yoga exhibited significantly smaller placebo hypoalgesia (mean = 14.41, SEM = 0.91) compared to those who did not (mean = 20.67, SEM = 0.55, F1,2111.40 = 33.66, Bonferroni corrected p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.232 Figure 3c). This result was unrelated to heat pain threshold (F1,349 = 1.28, p = 0.26) and heat pain tolerance (F1,348 = 0.410, p = 0.29).

Moreover, TMD participants using massage also exhibited reduced placebo hypoalgesia (mean = 15.55, SEM = 0.92) compared to those who did not (mean = 20.15, SEM = 0.54, F1,2111.40 = 18.17, Bonferroni corrected p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.167 Figure 3d). The above results were independent of sex, race, educational level and TMD duration. This result was unrelated to heat pain threshold (F1,349 = 0.19, p = 0.660) and heat pain tolerance F1,348 = 1.53, p = 0.22). Other specific CIHA were not significantly related to placebo hypoalgesia (all p > 0.090).

Regarding placebo responsiveness, 200 out of 361 TMD participants (55.4%) were placebo responders while 44.6% were non-responders (Figure 4a). TMD participants using less physically oriented MBPs were more likely to be placebo responders (OR = 0.70, p = 0.004, 95% CI = 0.55–0.89 Figure 4b). To further determine the relationship between the number of physically oriented MBPs and the likelihood of being a placebo non-responder, we estimated the probability of being non-responders based on logistic regression. The probability of being placebo non-responders was greater than chance (mean = 58.95%, SD = 8.96%) when participants used at least 3 physically oriented MBPs (Table 2). We further confirmed this cut-off by running chi-square analysis to compare the proportion of placebo non-responders in participants who had 3 or above physically oriented MBPs vs. 2 or less physically oriented MBPs. We found that 62.5% of participants who were using 3 or above physically oriented MBPs were placebo non-responders, while 43.3% of participants who were using 2 or less physically oriented MBPs were non-responderswith a marginal significant χ2 = 3.34, p = 0.068. The number of psychologically oriented MBPs used (OR=0.86, p = 0.08) and the number of natural products used (OR=0.87, p = 0.10) were not significantly associated with the placebo responsiveness status. Similarly, use of CIHA did not significantly influence the placebo responsiveness (use of psychologically oriented MBPs: χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.97; use of physically oriented MBPs: χ2 = 1.02, p = 0.31; use of natural product: χ2 = 0.96, p = 0.33).

FIGURE 4.

Interconnection between physically oriented mind-body practices and occurrence of placebo effects. (a) Placebo responsiveness distribution. Based on the results of permutation tests, 200 out of 361 TMD participants (55.4%) were placebo responders while 44.6% were non-responders. Pink dots represent placebo non-responders, and blue dots represent placebo responders. (b) Number of physically oriented MBPs and placebo responsiveness. Those who used less MBPs were more likely to be placebo responders independently of the pain severity/interference. Regression line and 95% confidence interval were displayed in crimson. (c) Mediation role of cognitively and affectively based expectations. Affectively based expectations partially mediated the relationship between the number of physically oriented MBPs and placebo effects magnitudes. Cognitively based expectation did not serve as a significant mediator. Solid lines indicated significant paths while dashed lines represented non-significant paths.

TABLE 2.

Probability of placebo non-responders based on logistic regression.

| Number of physically oriented MBP | Probability of placebo non-responders |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N a | |

| 0 | 0.4072 | 0.12282 | 198 |

| 1 | 0.4535 | 0.12137 | 93 |

| 2 | 0.4977 | 0.09011 | 45 |

| 3 | 0.5895 | 0.08957 | 19 |

| 4 | 0.7217 | 0.12953 | 5 |

Data from one TMD participant was not included in the regression due to missing of chronic pain severity data.

3.3 |. Expectation of pain relief as a mediator

Bivariate correlation indicated that both cognitively based (Pearson r = 0.11, p = 0.032) and affectively based expectations (Pearson r = 0.16, p = 0.003) were positively correlated with the magnitude of placebo hypoalgesic effects. Moreover, a greater number of physically oriented MBPs were related with higher level of affectively based expectations (Pearson r = 0.13, p = 0.011).

Mediation analysis was therefore conducted with the number of physically oriented MBPs set as , placebo effects set as , and cognitively based and affectively based expectations as two mediators (M1 and M2). The result from mediation analysis indicated that affectively based expectations, not cognitively based expectations, partially mediated the effects of the number of physically oriented MBPs on placebo effects (indirect effect: a×b = 0.33, BCI = 0.03–0.79). The direct effect of the number of physically oriented MBPs on placebo hypoalgesia was significant ( = −2.70, BCI = −4.56 to −0.85, Figure 4c). This result suggested that despite TMD participants using a greater number of physically oriented MBPs, they generally had smaller placebo effects and higher levels of affectively based expectations that still resulted in larger placebo effects, after accounting for part of the influences of physically oriented MBPs on placebo effects.

3.4 |. CIHA and TMD disability

TMD disability was expressed as chronic pain intensity and chronic pain interference. The use of CIHA was not significantly associated with chronic intensity (use of physically oriented MBPs: F1,349 = 0.01, p = 0.97; use of psychologically oriented MBPs: F1,349 = 0.00, p =0.98; and use of natural product: F1,349 = 0.08, p = 0.79). CIHA was also not significantly associated with chronic pain interference (use of CIHA: F1,349 = 0.79, p = 0.38; use of physically oriented MBPs: F1,349 = 0.35, p = 0.68; use of psychologically oriented MBPs: F1,349 = 0.01, p = 0.95; use of natural product: F1,349 = 0.04, p = 0.85) after controlling for sex, race, educational level, TMD duration and use of pharmacological treatments. Further comparisons were made between Yoga users vs. non-users but no significant differences were found in chronic pain intensity (F1,349 = 0.02, p = 0.89) or chronic pain interference (F1,349 = 2.16, p = 0.14). Similarly, use of massage was not related to chronic pain intensity (F1,349 = 0.78, p = 0.38) or interference (F1,349 = 0.04, p = 0.84).

A portion of participants (n = 161) reported having TMD and other chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs) including migraine (n = 53), fibromyalgia (n = 19), low back pain (n = 122), and irritable bowel syndrome (n = 15). Comparing TMD with no COPCs and with COPCs, there were no differences for use of natural products (χ2 = 1.424, p = 0.23) and MBPs (χ2 = 1.321, p = 0.25).

Finally, we examined the differences between those who were using CIHA together with pharmacological pain therapeutics (n = 241) and those who were using CIHA in place of pharmacological pain therapeutics (n = 34). We found no significant differences for chronic pain intensity (F1,263 = 0.05, p = 0.82), pain interference (F1,263 = 2.63, p = 0.11), and placebo hypoalgesia (F1,1602.33 = 0.19, p = 0.67).

4 |. DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study investigated the interconnection between self-reported use of CIHA and placebo effects in chronic pain. We found that physically oriented MBP users such as yogis and massage users responded less to the placebo manipulation. This finding was independent of the underlying clinical pain severity, experimental pain thresholds and pain tolerance limits. Moreover, affective-based expectations mediated the relationship between the number of physically oriented MPBs and the magnitude of placebo effects.

Our results shed light on CIHA use patterns in a TMD cohort. We found that chronic pain patients seek complementary health approaches independently of their pain disability. Additionally, we found that there are no significant differences in chronic pain interference, chronic pain intensity, or placebo hypoalgesia between those who use CIHA with pharmacological therapeutics and those who use CIHA in place of pharmacological therapeutics. These findings were in line with previous studies where the patients chose to use CIHA because CIHA approaches are more consistent with their beliefs, values, and philosophical orientations and not because of their dissatisfaction with the outcomes of conventional medicine treatments (Astin, 1998; Tan et al., 2013). It should be noted that although the literature suggests CIHA are relatively effective in pain management (Astin, 2004; Garland et al., 2019), the results remain inconclusive (Arienti, 2021; Wieland et al., 2022).

To further illuminate CIHA use patterns, our results indicated that participants who suffer from chronic pain for more than 5years (250 out of 369, 69.3%) were more likely to use MBPs (70.8%) and natural products (44.8%). This finding is in line with previous research that indicated, for example, that chronic low back pain (cLBP) patients are more likely to use CIHA (Dubois et al., 2017). The significant interaction between use of CIHA and TMD duration could reflect a need within patients suffering from long durations of pain to explore a variety of pain therapeutics.

Our main finding was that use of physically oriented MBPs, but not psychologically oriented MBPs, were tied to reduced experimentally induced placebo hypoalgesia; this presents as an innovative and interesting result. Specifically, participants reporting use of yoga and massage exhibited significantly smaller experimental placebo hypoalgesic effects than those who did not report using them. This negative association suggests a potential interaction between the hypoalgesic mechanisms of physically oriented MBPs (e.g., touch based alternative treatments) and placebo effects.

Certain types of physically oriented MBPs such as yoga (Brems et al., 2016; Freeman et al., 2017) require introspection and concentration during the practice. Introspection is an increased internal awareness of mental state or processes. It is plausible that the process of introspection may have facilitated a more accurate assessment of the internal state including more stable and less variability in pain ratings in response to the heat temperature. In line with this reasoning, evidence from Triester et al. indicated that greater variabilities in pain reports were significantly associated with smaller placebo responses in a clinical trial (Treister et al., 2019). Further, it is well known that placebo effects are elicited in laboratory settings by exposing participants to distinct levels of stimulations (e.g., conditioning phase). It has also been hypothesized that placebo effects may depend on an altered ability to detect pain signals (e.g., pain signal detection (Allan & Siegel, 2002)) or Bayesian approach to perception (Arandia & Di Paolo, 2022; Ongaro & Kaptchuk, 2019), which considers placebo effects as a “false positive” behaviour in response to physical pain signals (Allan & Siegel, 2002). With this somatosensorial and introspective basis for placebo in mind, Yogis may have developed a greater ability to distinguish between distinct heat-pain stimulations. With a more accurate assessment of the heat-pain simulations during the sham-intervention trials, the resulting placebo hypoalgesia effect would be smaller. It is possible that more precise sensory input because of regularly practicing physically oriented MBPs decreases the impact of prior experiences of pain relief thereby rendering experimentally induced expectations less powerful in provoking placebo effects. In line with this interpretation, other studies also support that yoga users process pain signals differently. For example, Cotton et al. found that yogis, when faced with pain, do not experience a decrease in parasympathetic nervous system response like controls did (Cotton et al., 2018), and Villemure et al. found that yogis have increased intra-insular white matter integrity, facilitating stronger integration of nociceptive stimuli (Cotton et al., 2018; Villemure et al., 2014). These differences in pain sensitivity and bodily awareness have also been noted in studies on non-CIHA exercise like long-distance running, especially about pacing strategies (Edwards & Polman, 2013; Zeller et al., 2019). Those studies also noted that neural mechanisms are responsible for regulating exercise performance and that higher pain threshold characterize long-distance runners’ capabilities (Edwards & Polman, 2013; Zeller et al., 2019). The importance of bodily awareness in exercise elucidates the greater sensitivity of yoga users in a broader context.

Similar to our finding regarding yoga, we also found that participants who were using massage demonstrated smaller placebo hypoalgesic effects. Although no studies have investigated the link between massage and occurrence of placebo effects, previous studies have investigated massage in the context of pain modulation (Belavy et al., 2020; Loghmani et al., 2021). A meta-analysis indicated that massage among other CIHA interventions, improved pain sensitivity, supporting the conclusion that introspection and pain modulation systems can be regulated from massage-like practices (Belavy et al., 2020). Individuals with chronic pain may have an altered perception of their body, making it difficult for them to correctly interpret safe stimuli from the environment (Viceconti et al., 2020). Touch-based therapy, such as massage, can be viewed as one potential strategy to reorganize their somato-perceptual system (Geri et al., 2019). This reorganization could lead to an improvement in their ability to self-oriented concentration, and ultimately result in decreased placebo effects. With the modulatory role of introspection in placebo mechanisms in mind, massage, like yoga, may result in a smaller placebo hypoalgesic effect.

The study findings also highlight the importance of affective pain relief expectations rather than cognitively based pain relief expectations in mediating placebo effects. We found that greater level of affectively based expectations mediated the effects of the number of MBPs on the placebo hypoalgesia. Interestingly, those who used a larger number of physically oriented MBPs exhibited placebo hypoalgesic effects only when mediated by higher affectively based expectation. Notably, the logical thought about effectiveness of a treatment (cognition) may differ from the how an individual feels about the situation (affection) (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000), and neural affective components have emerged as critical mediators of placebo effects in previous studies (Zunhammer et al., 2018; Zunhammer et al., 2021).

Some limitations should be acknowledged. This study focuses on a specific population: TMD participants in the greater Baltimore region and may not be generalizable to the larger chronic pain population. Furthermore, this study examined experimental placebo effects, but we cannot prove causality. Mechanistic studies are needed to understand the role of yoga and massage in minimizing placebo effects. It should also be noted that the current study adopted a self-reported checklist assessing general information about CIHA usage. As far as we know, there are scales assessing the attitudes towards use of CIHA (Kersten et al., 2011; Rawsthorne et al., 1999) but no validated tools for assessing CIHA aspects such as the frequencies of using CIHA, perceived effectiveness and beliefs in CIHA approaches. Future studies would be needed to further develop and validate CIHA surveys to systematically assess CIHA use. Finally, it is worthy to note that clinical placebo effects may differ in certain ways from experimental placebo effects (Vase et al., 2002), so placebo effects in clinical practice and CIHA research should be further investigated to illuminate their interactions.

Despite the above limitations, this study serves to provide a well-rounded understanding of how placebo effects may be affected by CIHA use, an often-overlooked-yet-popular treatment option. Most notably, physically orientated MBPs such as yoga and massage are characterized by introspective processes that can make participants capable to detect distinct levels of painful sensation that are independent of the underlying pain severity and interference. The use of a treatment-based procedure in the current study, rather than a cue-based procedure, to induce placebo effects has important clinical implications. A treatment-based procedure enhances the ecological validity of the study by creating a longer-lasting expectation of treatment benefits. In contrast, a cue-based procedure would only produce an anticipatory expectation for the upcoming painful stimuli (Atlas, 2021). This finding highlights the potential clinical applications of treatment-based procedures to harness placebo effects as part of pain management strategies. Considering that CIHA and placebo effects have been shown to affect pain experience, it is imperative that further research investigates the unique relationship between CIHA, chronic pain, and placebo from a mechanistic perspective.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Individuals who were using physically oriented CIHA showed decreased placebo effects in experimental settings possibly through their improved ability to influence psychophysical behaviours. Future research is required to understand how placebo effects might influence pain management in those who use CIHA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the study participants for their time. We also thank Nathaniel Haycock for his comments on the first version of this manuscript. We thank Gilda Martinez-Alba for her input on the survey per se and Katherine Tuttle for beta-testing the CIHA survey.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental Craniofacial Research (ROI DE025946, LC) and by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NCCIH: R01AT011347, LC). The funding agencies have no roles in the study. The views expressed here are the authors’ own and do not reflect the position or policy of Maryland State and National Institutes of Health or any other part of the federal government.

National Institute of Dental Craniofacial Research, Grant/Award Number: R01 DE025946; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Grant/Award Number: R01AT011347; National Institue of Dental Craniofacial Research, Grant/Award Number: R21DE032532

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Allan LG, & Siegel S. (2002). A signal detection theory analysis of the placebo effect. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 25, 410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arandia IR, & Di Paolo EA (2022). On symptom perception, placebo effects, and the Bayesian brain. Pain, 163, e604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arienti C. (2021). Can herbal medicinal products or preparations alleviate neuropathic pain in adults? A Cochrane review summary with commentary. NeuroRehabilitation, 48, 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astin JA (1998). Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. JAMA, 279,1548–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astin JA (2004). Mind-body therapies for the management of pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 20, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas LY (2021). A social affective neuroscience lens on placebo analgesia. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25, 992–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister K, & Hughes S. (2022). One size does not fit all: Towards optimising the therapeutic potential of endogenous pain modulatory systems. Pain, 164, e5–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belavy DL, Van Oosterwijck J, Clarkson M, Dhondt E, Mundell NL, Miller CT, & Owen PJ (2020). Pain sensitivity is reduced by exercise training: Evidence from a systematic review and metaanalysis. Neuroscience &Biobehavioral Reviews, 120,100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Bleakley C, Hurley DA, Gill C, Hannon-Fletcher M, Bell P, & McDonough S. (2019). Herbal medicinal products or preparations for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD010528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems C, Colgan D, Freeman H, Freitas J, Justice L, Shean M, & Sulenes K. (2016). Elements of yogic practice: Perceptions of students in healthcare programs. International Journal of Yoga, 9,121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, & Michalsen A. (2017). Management of chronic pain using complementary and integrative medicine. BMJ, 357, j1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GT, Padilla M, & Dionne R. (2016). Medication treatment efficacy and chronic orofacial pain. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 28,409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L. (2019a). How do placebo effects and patient-clinician relationships influence behaviors and clinical outcomes? Pain Reports, 4, e758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L. (2019b). The placebo effect in pain therapies. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 59,191–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L, Akintola T, Haycock NR, Blasini M, Thomas S, Phillips J, Corsi N, Schenk LA, & Wang Y. (2020). Prior therapeutic experiences, not expectation ratings, predict placebo effects: An experimental study in chronic pain and healthy participants. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89, 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton VA, Low LA, Villemure C, & Bushnell MC (2018). Unique autonomic responses to pain in yoga practitioners. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80, 791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, & Borkovec TD (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31, 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D, Pollard B, & Johnston M. (2007). What does the chronic pain grade questionnaire measure? Pain, 130, 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J, Scala E, Faouzi M, Decosterd I, Burnand B, & Rodondi PY (2017). Chronic low back pain patients’ use of, level of knowledge of and perceived benefits of complementary medicine: A cross-sectional study at an academic pain center. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AM, & Polman RC (2013). Pacing and awareness: Brain regulation of physical activity. Sports Medicine, 43,1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E. (2022). What Prince Charles tells us about complementary medicine-an essay by Edzard Ernst. BMJ, 376, o310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, & Buchner A. (2007). G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39,175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, Vladagina N, Razmjou E, & Brems C. (2017). Yoga in print media: Missing the heart of the practice. International Journal of Yoga, 10,160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhstorfer H, Lindblom U, & Schmidt WC (1976). Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 39, 1071–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Brintz CE, Hanley AW, Roseen EJ, Atchley RM, Gaylord SA, Faurot KR, Yaffe J, Fiander M, & Keefe J. (2019). Mind-body therapies for opioid-treated pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(1), 91–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geri T, Viceconti A, Minacci M, Testa M, & Rossettini G. (2019). Manual therapy: Exploiting the role of human touch. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 44,102044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptchuk TJ (2002). The placebo effect in alternative medicine: Can the performance of a healing ritual have clinical significance? Annals of Internal Medicine, 136, 817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten P, White PJ, & Tennant A. (2011). Construct validity of the holistic complementary and alternative medicines questionnaire (HCAMQ)—An investigation using modem psychometric approaches. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011, 396327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loghmani MT, Tobin C, Quigley C, & Fennimore A. (2021). Soft tissue manipulation may attenuate inflammation, modulate pain, and improve gait in conscious rodents with induced low back pain. Military Medicine, 186, 506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, & Slade D. (2016). Overlapping chronic pain conditions: Implications for diagnosis and classification. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society, 17, T93–T107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Sternberg WF, Marek P, Sadowski B, Belknap JK, & Liebeskind JC (1996). The genetics of pain and pain inhibition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93, 3048–3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Temporomandibular disorders: Priorities for research and care. The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen CS, Price DD, Vassend O, Stubhaug A, & Harris JR (2005). Characterizing individual differences in heat-pain sensitivity. Pain, 119, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okusogu C, Wang Y, Akintola T, Haycock NR, Raghuraman N, Greenspan JD, Phillips J, Dorsey SG, Campbell CM, & Colloca L. (2020). Placebo hypoalgesia: Racial differences. Pain, 161,1872–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EM, Akintola T, Phillips J, Blasini M, Haycock NR, Martinez PE, Greenspan JD, Dorsey SG, Wang Y, & Colloca L. (2021). Effects of sex on placebo effects in chronic pain participants: A cross-sectional study. Pain, 162, 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro G, & Kaptchuk TJ (2019). Symptom perception, placebo effects, and the Bayesian brain. Pain, 160,1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina M, & Zubieta JK (2015). Over a decade of neuroim-aging studies of placebo analgesia in humans: What is next? Molecular Psychiatry, 20,415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phutrakool P, & Pongpirul K. (2022). Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: A 15-year systematic review and data synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 11,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne P, Shanahan F, Cronin NC, Anton PA, Löfberg R, Bohman L, & Bernstein CN (1999). An international survey of the use and attitudes regarding alternative medicine by patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 94,1298–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy B, & Fan AY (2022). Incorporation of complementary and traditional medicine in ICD-11. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 21, 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, List T, Svensson P, Gonzalez Y, Lobbezoo F, Michelotti A, Brooks SL, Ceusters W, Drangsholt M, Ettlin D, Gaul C, Goldberg LJ, Haythornthwaite JA, Hollender L, ... International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. (2014). Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network* and orofacial pain special interest Groupdagger. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache, 28, 6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. (2018). Step away from stepwise. Journal of Big Data, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, & Guyatt GH (2010). Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ, 340, c117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Ioannidis JP, Agoritsas T, Alba AC, & Guyatt G. (2014). How to use a subgroup analysis: Users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA, 311, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Win MT, & Khan SA (2013). The use of complementary and alternative medicine in chronic pain patients in Singapore: A single-Centre study. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 42,133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchivileva IE, Hadgraft H, Lim PF, Di Giosia M, Ribeiro-Dasilva M, Campbell JH, Willis J, James R, Herman-Giddens M, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Arbes SJ Jr., & Slade GD (2020). Efficacy and safety of propranolol for treatment of TMD pain: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain, 161,1755–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treister R, Honigman L, Lawal OD, Lanier RK, & Katz NP (2019). A deeper look at pain variability and its relationship with the placebo response: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of naproxen in osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain, 160,1522–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon-Presseau E, Berger SE, Abdullah TB, Huang L, Cecchi GA, Griffith JW, Schnitzer TJ, & Apkarian AV (2018). Brain and psychological determinants of placebo pill response in chronic pain patients. Nature Communications, 9, 3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, & STROBE Initiative. (2007). Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147, W163–W194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vase L, Riley JL 3rd, & Price DD (2002). A comparison of placebo effects in clinical analgesic trials versus studies of placebo analgesia. Pain, 99,443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viceconti A, Camerone EM, Luzzi D, Pentassuglia D, Pardini M, Ristori D, Rossettini G, Gallace A, Longo MR, & Testa M. (2020). Explicit and implicit own’s body and space perception in painful musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases: A systematic scoping review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemure C, Ceko M, Cotton VA, & Bushnell MC (2014). Insular cortex mediates increased pain tolerance in yoga practitioners. Cerebral Cortex, 24, 2732–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, & Initiative S. (2008). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, & Drazen JM (2007). Statistics in medicine — Reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 2189–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chan E, Dorsey SG, Campbell CM, & Colloca L. (2022). Who are the placebo responders? A cross-sectional cohort study for psychological determinants. Pain, 163, 1078–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tricou C, Raghuraman N, Akintola T, Haycock NR, Blasini M, Phillips J, Zhu S, & Colloca L. (2020). Modeling learning patterns to predict Placebo analgesic effects in healthy and chronic orofacial pain participants. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, Harbin S, Vempati R, & Berman BM (2022). Yoga for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD010671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310, 2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F, Emerson NM, Farris SR, Ray JN, Jung Y, McHaffie JG, & Coghill RC (2015). Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief employs different neural mechanisms than Placebo and sham mindfulness meditation-induced analgesia. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35,15307–15325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller L, Shimoni N, Vodonos A, Sagy I, Barski L, & Buskila D. (2019). Pain sensitivity and athletic performance. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 59,1635–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunhammer M, Bingel U, Wager TD, & Placebo Imaging Consortium. (2018). Placebo effects on the neurologic pain signature: A meta-analysis of individual participant functional magnetic resonance imaging data. JAMA Neurology, 75, 1321–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunhammer M, Spisak T, Wager TD, Bingel U, & Placebo Imaging Consortium. (2021). Meta-analysis of neural systems underlying placebo analgesia from individual participant fMRI data. Nature Communications, 12,1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.