Abstract

Background

Home haemodialysis (HHD) may be associated with important clinical, social or economic benefits. However, few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated HHD versus in‐centre HD (ICHD). The relative benefits and harms of these two HD modalities are uncertain. This is an update of a review first published in 2014. This update includes non‐randomised studies of interventions (NRSIs).

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of HHD versus ICHD in adults with kidney failure.

Search methods

We contacted the Information Specialist and searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 9 October 2022 using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We searched MEDLINE (OVID) and EMBASE (OVID) for NRSIs.

Selection criteria

RCTs and NRSIs evaluating HHD (including community houses and self‐care) compared to ICHD in adults with kidney failure were eligible. The outcomes of interest were cardiovascular death, all‐cause death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke, all‐cause hospitalisation, vascular access interventions, central venous catheter insertion/exchange, vascular access infection, parathyroidectomy, wait‐listing for a kidney transplant, receipt of a kidney transplant, quality of life (QoL), symptoms related to dialysis therapy, fatigue, recovery time, cost‐effectiveness, blood pressure, and left ventricular mass.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed if the studies were eligible and then extracted data. The risk of bias was assessed, and relevant outcomes were extracted. Summary estimates of effect were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Confidence in the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Meta‐analysis was performed on outcomes where there was sufficient data.

Main results

From the 1305 records identified, a single cross‐over RCT and 39 NRSIs proved eligible for inclusion. These studies were of varying design (prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, cross‐sectional) and involved a widely variable number of participants (small single‐centre studies to international registry analyses). Studies also varied in the treatment prescription and delivery (e.g. treatment duration, frequency, dialysis machine parameters) and participant characteristics (e.g. time on dialysis). Studies often did not describe these parameters in detail. Although the risk of bias, as assessed by the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale, was generally low for most studies, within the constraints of observational study design, studies were at risk of selection bias and residual confounding.

Many study outcomes were reported in ways that did not allow direct comparison or meta‐analysis. It is uncertain whether HHD, compared to ICHD, may be associated with a decrease in cardiovascular death (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.07; 2 NRSIs, 30,900 participants; very low certainty evidence) or all‐cause death (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.95; 9 NRSIs, 58,984 patients; very low certainty evidence). It is also uncertain whether HHD may be associated with a decrease in hospitalisation rate (MD ‐0.50 admissions per patient‐year, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.02; 2 NRSIs, 834 participants; very low certainty evidence), compared with ICHD.

Compared with ICHD, it is uncertain whether HHD may be associated with receipt of kidney transplantation (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.63; 6 NRSIs, 10,910 participants; very low certainty evidence) and a shorter recovery time post‐dialysis (MD ‐2.0 hours, 95% CI ‐2.73 to ‐1.28; 2 NRSIs, 348 participants; very low certainty evidence). It remains uncertain if HHD may be associated with decreased systolic blood pressure (SBP) (MD ‐11.71 mm Hg, 95% CI ‐21.11 to ‐2.46; 4 NRSIs, 491 participants; very low certainty evidence) and decreased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) (MD ‐17.74 g/m2, 95% CI ‐29.60 to ‐5.89; 2 NRSIs, 130 participants; low certainty evidence). There was insufficient data to evaluate the relative association of HHD and ICHD with fatigue or vascular access outcomes.

Patient‐reported outcome measures were reported using 18 different measures across 11 studies (QoL: 6 measures; mental health: 3 measures; symptoms: 1 measure; impact and view of health: 6 measures; functional ability: 2 measures). Few studies reported the same measures, which limited the ability to perform meta‐analysis or compare outcomes.

It is uncertain whether HHD is more cost‐effective than ICHD, both in the first (SMD ‐1.25, 95% CI ‐2.13 to ‐0.37; 4 NRSIs, 13,809 participants; very low certainty evidence) and second year of dialysis (SMD ‐1.47, 95% CI ‐2.72 to ‐0.21; 4 NRSIs, 13,809 participants; very low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Based on low to very low certainty evidence, HHD, compared with ICHD, has uncertain associations or may be associated with decreased cardiovascular and all‐cause death, hospitalisation rate, slower post‐dialysis recovery time, and decreased SBP and LVMI. HHD has uncertain cost‐effectiveness compared with ICHD in the first and second years of treatment.

The majority of studies included in this review were observational and subject to potential selection bias and confounding, especially as patients treated with HHD tended to be younger with fewer comorbidities. Variation from study to study in the choice of outcomes and the way in which they were reported limited the ability to perform meta‐analyses. Future research should align outcome measures and metrics with other research in the field in order to allow comparison between studies, establish outcome effects with greater certainty, and avoid research waste.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Ambulatory Care Facilities; Bias; Cardiovascular Diseases; Cardiovascular Diseases/mortality; Cause of Death; Hemodialysis, Home; Hemodialysis, Home/adverse effects; Hemodialysis, Home/methods; Hemodialysis, Home/mortality; Hospitalization; Hospitalization/statistics & numerical data; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Kidney Failure, Chronic/complications; Kidney Failure, Chronic/mortality; Kidney Failure, Chronic/therapy; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/mortality; Non-Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Renal Dialysis; Renal Dialysis/adverse effects; Renal Insufficiency; Renal Insufficiency/mortality; Renal Insufficiency/therapy; Stroke; Stroke/mortality

Plain language summary

Is home haemodialysis better than in‐centre haemodialysis for people with kidney failure?

Key messages

‐ Home haemodialysis may be preferred by some patients. However, the research gives us very uncertain answers.

‐ We are unsure whether the better patient outcomes with home haemodialysis are because of the dialysis treatment itself or because patients receiving home haemodialysis are younger and less sick.

Why perform haemodialysis at home rather than in a dialysis centre?

Kidney failure is a common and increasingly prevalent public health problem, which results in increases in illness, death and healthcare costs. People with kidney failure require kidney replacement therapy (dialysis and kidney transplantation) to remove the accumulation of waste products in the blood, which in turn may assist with reducing symptoms such as fatigue, nausea and itching and may improve a person's overall quality of life. Unfortunately, some patients lack access to hospital dialysis care.

What did we want to find out?

People who are treated with haemodialysis at home may experience increased well‐being and might live longer. However, home haemodialysis may also increase the burden of healthcare for patients and families and increase technical problems for patients.

What did we do?

We searched for randomised and non‐randomised studies comparing home haemodialysis with hemodialysis treatment performed in a hospital or clinical setting. We compared and summarised the trials' results and rated our confidence in the information based on factors such as trial methods and size.

What did we find?

We found only one randomised study (where patients are randomly allocated to one treatment or the other) that compared home haemodialysis with in‐centre haemodialysis in nine patients. All other studies (39) were observational (where the treatment was not randomly assigned).

Home haemodialysis may be associated with outcomes including increased length of life, fewer hospital stays, higher chance of receiving a kidney transplant, shorter recovery time from dialysis itself and increased control of blood pressure. Patients receiving home haemodialysis tended to have more dialysis (more hours or more often). Some of the differences in outcomes for patients may have been due to factors that were not related to dialysis treatment since patients receiving home haemodialysis were younger and had fewer other illnesses.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

The small number and size of the studies were limitations in this review. Not all the studies provided data about the outcomes we were interested in, and we are unsure about the results.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

The evidence is up to date as of October 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Cardiovascular death | RR 0.92 (0.80 to 1.07) | 30,900 (2) | Very low1 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

‐ |

| All‐cause death | RR 0.80 (0.67 to 0.95) | 58,984 (9) | Very low2 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Studies varied from small single centre studies and large registry analyses. Follow‐up duration varied from less than two years to more than 10 years |

| Hospitalisation | ||||

| All‐cause annual hospitalisation rate (admissions/patient‐year) | MD ‐0.50 admissions (‐0.98 to ‐0.02) | 834 (2) | Very low3 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

‐ |

| All‐cause annual hospitalisation days (days/patient‐year) | MD ‐1.90 days (‐2.28 to ‐1.53) | 834 (2) | Low4 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

‐ |

| Received kidney transplantation | RR 1.28 (1.01 to 1.63) | 10,910 (6) | Very low5 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Studies varied from small single centre studies and large registry analyses |

| Health‐related quality of life | ||||

| Physical Component Summary | SMD 0.42 (0.10 to 0.73) | 922 (5) | Very low6 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

All studies were cross‐sectional design. The time on dialysis varied substantially between studies (Table 2) |

| Mental Component Summary | SMD 0.10 (‐0.05 to 0.25) | 922 (5) | Very low7 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

All studies were cross‐sectional design. The time on dialysis varied substantially between studies (Table 2) |

| Recovery time (hours) | MD ‐2.00 (‐2.73 to ‐1.28) | 348 (2) | Low8 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

Included one longitudinal cohort study of patients transitioning dialysis modality, and reported mean of weekly responses during 8‐week period on each modality, and one cross‐sectional survey of prevalent dialysis patients (time current on modality not reported) |

| Blood pressure7 | ||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | MD ‐11.78 (‐21.11 to ‐2.46) | 491 (4) | Very low9 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Included both longitudinal cohort and cross‐sectional studies. Exclusion of cross‐sectional studies led to similar relative effect with reduced heterogeneity (MD ‐19.47, 95% CI ‐24.40 to ‐14.54; I2 = 42%) Data from one RCT also indicated lower BP with HHD versus ICHD (155 ± 18 vs 169 ± 24 mm Hg) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | MD 1.81 (‐1.31 to 4.94) | 383 (3) | Very low10 ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Included both longitudinal cohort and cross‐sectional studies Data from one RCT indicated lower BP with HHD versus ICHD (89 ± 6 vs 93 ± 9 mm Hg) |

HHD: home haemodialysis; ICHD: in‐centre haemodialysis; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference; BP: blood pressure; NRSI: non‐randomised study of intervention; RCT: randomised controlled trial

- Downgraded due to imprecision of relative effect (CI includes the possibility of no effect or harm)

- Downgraded due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 84%)

- Downgraded due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 90%)

- Downgraded based on 2 non‐randomised observational studies

- Downgraded due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 78%)

- Downgraded due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 74%) and risk of bias

- Downgraded due to imprecision of relative effect (CI includes the possibility of no effect or harm) and risk of bias

- Relative effect based on data from NRSIs, as only one RCT was identified during the systematic review

- Downgraded due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 81%)

- Downgraded due to imprecision of relative effect, CI includes the possibility of no effect or harm

1. Vintage of patients included in Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary analysis.

| Metric | HHD | ICHD | |

|

Jayanti 2016 ICHD (197) HHD (91) |

Median dialysis vintage (years) | 3.47 (IQR 1.39, 6.82) | 2.68 (IQR 1.05, 5.12) |

|

Toronto Group 2002 ICHD (163) HHD (56) |

Not reported | Not reported | |

|

Wong 2019a ICHD (253) HHD (41) |

Mean duration of ESKD diagnosis (years) | 7.5 ± 4.9 | Not reported |

|

Wright 2015 ICHD (29) HHD (22) |

Time on dialysis (number of patients) | ||

| 6 to 12 months | 7 | 3 | |

| 1 to 5 years | 8 | 17 | |

| 5 to 10 years | 6 | 6 | |

| 10 to 20 years | 0 | 2 | |

| > 20 years | 1 | 1 | |

|

Watanabe 2014 ICHD (34) HHD (46) |

Time on dialysis (years) | 7.4 ± 8.3 | 6.4 ± 5.7 |

ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; HHD: home haemodialysis; ICHD: in‐centre haemodialysis; IQR: interquartile range

Background

Description of the condition

Kidney failure is a common and increasingly prevalent public health problem, which results in excess morbidity, death and healthcare costs (Bello 2017a; Bello 2019). People with kidney failure require kidney replacement therapy (KRT; dialysis and kidney transplantation) to address the physiological accumulation of fluid and metabolites, which in turn may assist with reducing uraemic symptoms (such as fatigue, anorexia, nausea and pruritus), improving health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and prolonging survival (Cabrera 2017). Unfortunately, some patients lack access to dialysis care, and although kidney transplantation is associated with increased survival and quality of life (QoL) compared with dialysis (Laupacis 1996; Tonelli 2011; Wolfe 1999), only 22% of all patients with treated kidney failure around the world receive kidney transplantation (Bello 2019). The remaining patients are treated with either haemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) (Bello 2017a; Bello 2019). The median survival of patients with kidney failure on dialysis is considerably shorter than for patients with common types of cancer (e.g. breast, colorectal, prostate) (Naylor 2019). Moreover, kidney failure results in substantial financial costs to the health system, accounting for 2% to 3% of healthcare spending in higher‐resource countries, despite patients with kidney failure comprising 0.1% to 0.2% of the population (Bello 2017b).

Ascertaining the optimal means of delivering dialysis in terms of patient‐reported, clinical and health‐economic outcomes is important information for patients, people who support their care, clinicians and healthcare policymakers.

Description of the intervention

HD is the most commonly used dialysis modality, comprising 89% of all dialysis and 69% of KRT globally (Pecoits‐Filho 2020). HD can be performed either in a centre (e.g. hospital or satellite dialysis units) or the patient’s own home. The prevalence of home HD (HHD) use varies widely worldwide, with 14% of prevalent dialysis patients doing HHD in Aotearoa, New Zealand, in 2019 (ANZDATA 2021). On the other hand, in the USA, only 1.9% of prevalent dialysis patients were doing HHD in 2019 (USRDS 2021). This is despite the fact that home‐based dialysis therapies have significant cost benefits compared to in‐centre HD (ICHD), with a Canadian study estimating the total annual cost of ICHD to be $73,920 after the first year, compared to $45,203 for HHD (Klarenbach 2014).

ICHD is usually performed by a trained nurse, who sets up the equipment, inserts the needles, monitors the patient, and adjusts treatment parameters as needed throughout the treatment. ICHD prescriptions typically involve four to five hours of dialysis three times/week (ANZDATA 2021).

Patients wishing to do HHD usually undertake one to four months of training, which covers machine set‐up and basic maintenance, needling of their fistula or graft, or accessing their dialysis vascular catheter, troubleshooting and managing alarms on dialysis (Kidney Health Australia 2013; USRDS 2021). In addition, home assessment and modifications may be required to confirm patients have a suitable space to perform dialysis and store supplies, as well as an adequate power and water supply. As most patients performing HD in their own homes do so independently or with the assistance of a family member or support person, this allows considerably greater flexibility in treatment duration and frequency compared with those undergoing ICHD, who must fit into more rigid schedules (Kidney Health Australia 2013). Patients receiving HHD may also utilise extended hours regimens, such as nocturnal (6 to 10 hours overnight), extended hours (6 to 10 hours/session), or short daily dialysis (< 4 hours/session, performed on a daily basis).

How the intervention might work

Epidemiological studies have indicated that HHD treatment may be associated with improved patient outcomes compared to ICHD. However, there is likely selection bias since patients receiving HHD tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities (Mailloux 1996; Woods 1996). HHD has also been associated with increased patient autonomy and QoL (Cases 2011; Walsh 2005). Since HHD enables increased dialysis hours and frequency compared to ICHD, there are a number of potential treatment‐related benefits compared to conventional HD, including increased small solute clearance (typically measured as Kt/Vurea), improved control of serum phosphate and blood pressure (BP) (FHN Trial Group 2010), reduced myocardial stunning (Jefferies 2011), and shorter interdialytic intervals which may mitigate the heightened risk of death associated with long (three‐day) interdialytic intervals (Foley 2011; Krishnasamy 2013). Augmented dialysis duration and/or frequency can also assist with reducing ultrafiltration rate requirements, which in turn have been associated with reduced death (Assimon 2016). Thus, it is possible that HHD improves survival compared to ICHD, perhaps through a reduction in cardiovascular events.

On the other hand, HHD can result in an increased burden on patients, families and support people (Gilbertson 2019; Iyasere 2016; Morton 2010; Suri 2011). In addition, due to reduced clinical oversight of dialysis technique, patients performing HHD may be at increased risk of complications, such as infection and thrombosis (FHN Trial Group 2010; Suri 2013). These potential risks need to be weighed against the potential benefits of HHD.

Why it is important to do this review

HHD may increase survival and QoL and is less costly to healthcare systems than ICHD (Klarenbach 2014; Walker 2014). However, these potential benefits need to be considered against the potential disadvantages of HHD, which include increased burden and risk of complications. Evaluation of research comparing HHD and ICHD is limited, and a previous systematic review identified a single randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Palmer 2014). This updated version of that systematic review includes randomised and non‐randomised studies of interventions (NRSIs), using the available evidence to inform shared decision‐making by clinicians and patients regarding HD modality choice and its effects on patient‐reported, clinical and surrogate outcomes and adverse events.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of HHD versus ICHD in adults with kidney failure.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) and NRSIs (observational studies with prospective and retrospective identification of participants, including registry studies) comparing HHD with ICHD in patients with kidney failure were eligible. In order for data to be from studies providing dialysis in a manner comparable to current practice, studies published from the year 2000 onwards were eligible (Marshall 2015).

Studies were required to include:

Comparison of HHD and ICHD between two or more groups of participants or within the same group of participants over time.

Groups of individuals formed by randomisation, quasi‐randomisation, time differences, location differences, or health professionals' or participants' preferences.

Identification of participants, assessment before intervention, actions/choices leading to an individual becoming a member of a group and assessment of outcomes carried out before or after the study was designed (prospective or retrospective design).

An assessment of the comparability between groups of potential confounders or not (e.g. non‐adjusted analyses).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults (≥ 18 years) with kidney failure receiving ICHD or HHD

Incident and prevalent HD patients

HD patients previously treated with PD

Patients previously treated with kidney transplantation.

Exclusion criteria

The review did not include data obtained from children or patients with acute kidney injury, as these patients are rarely treated with HHD due to anticipated recovery of kidney function.

Types of interventions

HD provided using any dialysis machine, dialysate, blood or dialysate flow rate, membrane type, dialysis dose (urea clearance), or vascular access type (central venous catheter (CVC), arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or arteriovenous graft (AVG)) was included. We included studies with any duration of dialysis and any frequency in either treatment arm.

HHD was defined as any type of HD, haemodiafiltration, or haemofiltration carried out by the patient or caregiver at home.

HHD included HD performed independently by patients (without the assistance of nursing or technical staff) in a community home or self‐care unit.

ICHD included HD provided in a hospital unit, a private dialysis unit, or a satellite dialysis unit in which nursing or technical staff provided dialysis care. Patients provided with HD by nursing or technical staff in their own homes were considered ICHD.

Studies evaluating PD as a home dialysis modality were excluded, except where data regarding participants receiving ICHD and HHD were disaggregated.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Cardiovascular death: fatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal stroke, sudden death, heart failure.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical outcomes

All‐cause death

Non‐fatal MI

Non‐fatal stroke

All‐cause hospitalisation: number of patients with one or more hospitalisation events

Kidney transplantation

-

Vascular access events

AVF/AVG intervention: surgical revision, thrombolysis/thrombectomy, fistulogram/fistuloplasty

CVC insertion/exchange

-

Infection

Local infection: exit‐site infection, cellulitis, abscess/collection

Systemic infection: bacteraemia

Parathyroidectomy

Patient‐reported outcomes

QoL: we considered and tabulated, where necessary, all reports of QoL outcomes using any instrument. Meta‐analyses were conducted when sufficient studies reported QoL outcomes using a single instrument, including measures of depression and household financial stress.

End‐of‐treatment employment status: employed, unemployed, not eligible for employment

Symptoms related to dialysis therapy: intradialytic cramping, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, headache

Fatigue

Recovery time

Health economics outcomes

Cost‐effectiveness

Surrogate outcomes

BP (systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse pressure measured in pre‐dialysis or other setting) (mm Hg)

Left ventricular mass (LVM): described using any diagnostic tool, including magnetic resonance imaging or echocardiography (g; g/m²)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 7 October 2022 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of hand‐searched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website under CKT Register of Studies.

For non‐randomised studies, we searched MEDLINE (OVID) 1 January 2000 to 20 July 2020 and EMBASE (OVID) 1 January 2000 to 20 July 2020.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this and the previous review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals or organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The search was performed unrestricted by language; non‐English articles were translated before assessment. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, if necessary, the full text of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Any further information required from the original author(s) was requested by written correspondence, and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication from one study existed, reports were grouped together, and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses (Higgins 2022). Where multiple publications reported the same outcome in the same or overlapping populations, or where we could not be certain that this did not occur, the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted. Disagreements were resolved by consultation with the authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Randomised controlled trials

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the Risk of Bias assessment tool version 2 (RoB 2) (Higgins 2022). The domains included in the assessment were as follows.

Bias arising from the randomisation process

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions

Bias due to missing outcome data

Bias in the measurement of the outcome

Bias in the selection of the reported result.

Non‐randomised studies of interventions

The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) (www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf) for assessing the quality of NRSIs was used. The NOS was used to adjudicate the risk of bias in non‐randomised studies. For cohort studies, the NOS used a star scoring system based on the selection of study groups (four items), comparability between the study group and the control group (two items) and the ascertainment of the exposure or outcome of interest (three items), for a total maximum score of nine stars (Appendix 2). An adapted NOS was used for studies using a cross‐sectional design (Herzog 2013). Selection (maximum five stars), comparability of cohorts based on the design or analysis (maximum two stars) and outcome (maximum two stars) were evaluated for a total maximum score of 10 stars (Appendix 3).

-

For case‐control studies, the following items were evaluated.

Selection: adequacy of definition, representativeness of the cases, selection of controls, definition of controls

Comparability: comparability of cases and controls based on the design or analysis

Exposure: ascertainment of exposure, same method of ascertainment for cases and controls, non‐response rate

-

For cohort studies, the following items were evaluated.

Selection: representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non‐exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study

Comparability: comparability of cohorts based on the design or analysis

Outcome: assessment of outcome, adequacy of follow‐up and duration of follow‐up

-

For cross‐sectional studies, an adapted NOS was used (Herzog 2013). The following items were evaluated.

Selection: representativeness of the sample, sample size, comparability of non‐respondents, ascertainment of the exposure

Comparability: comparability of cohorts based on the design or analysis

Outcome: assessment of outcome, suitability of statistical testing.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. death, cardiovascular events, hospitalisation, vascular access adverse events), results were expressed as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. QoL scale, BP, doses of medication, haemoglobin, biochemical variables), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. For effect measures reported as means and standard errors (SE), we obtained the standard deviation (SD) using the calculation provided in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2022). For effect measures reported as medians, ranges and/or interquartile ranges (IQR), we estimated means and SD using the approach described by Wan and colleagues (Wan 2014). Outcomes from RCTs and NRSIs were reported separately.

Meta‐analysis of change scores

Where data on both change‐from‐baseline and final value scores existed, we planned to combine data (e.g. LVM, BP) in a meta‐analysis using the (unstandardised) MD method (Higgins 2022). End‐of‐treatment values and change‐from‐baseline scores were placed in subgroups for clarity and summarised using random effects meta‐analysis.

Imputing standard deviation

When none of the above methods allowed calculation of the SD, we imputed change‐from‐baseline SD using an imputed correlation coefficient when sufficient data were available (Abrams 2005; Follmann 1992). If possible, we conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate the effect of imputing missing SD data in our meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only data from the first period of treatment in cross‐over studies (Higgins 2022). Data in different metrics were analysed by converting reported values to International System (SI) units. The final results were presented in SI units with conventional units in parentheses.

Dealing with missing data

If possible, data for each prespecified outcome were evaluated regardless of whether the analysis was based on intention‐to‐treat (ITT) or completeness of follow‐up. In particular, dropout rates were investigated and reported in detail (e.g. dropout due to discontinuation of dialysis modality, treatment failure, death, transplantation, withdrawal of consent or loss to follow‐up). Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing the corresponding author). Any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. We assessed all studies for risks of bias due to incomplete reporting of results. Evaluation of important numerical data, such as screened, randomised patients, as well as ITT, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2022). The following is a guide to the interpretation of I² values.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depended on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi² test or a CI for I²) (Higgins 2022).

Assessment of reporting biases

When there were at least 10 studies included in the meta‐analyses (Higgins 2022), we planned to test for asymmetries in the inverted funnel plots (i.e. for systematic differences in the effect sizes between more precise and less precise studies) using the original and modified Egger tests (Egger 1997) and the Begg and Mazumdar correlation test (Begg 1994). There are many potential explanations for why an inverted funnel plot may be asymmetric, including chance, heterogeneity, publication and reporting bias (Terrin 2005). We planned to refrain from judging funnel plot asymmetries based on visual inspection, as this has been shown to be misleading in empirical research (Lau 2006). Since our meta‐analyses did not include at least 10 studies for any of the outcomes evaluated, funnel plot asymmetries were not assessed.

Publication bias was also evaluated by testing the robustness of the results according to publications, namely publication as a full manuscript in a peer‐reviewed journal versus studies published as abstracts, letters or editorials.

Data synthesis

Data were summarised using the random‐effects model, but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure the robustness of the chosen model and susceptibility to outliers. We qualitatively summarised data where insufficient data were available for meta‐analysis. A qualitative review was conducted for adverse events and QoL outcomes in studies where a validated tool or metric was not used.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were planned to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants, interventions, and study quality). Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age and HD methods. Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to prior agent(s) used and the agent, dose, and duration of therapy.

Heterogeneity was planned to be investigated by analysing the data using subgroups according to the following parameters.

Age (< 60 years versus ≥ 60 years)

Presence of diabetes

Presence of cardiovascular disease

Study design (RCT versus NRSI)

Methodological quality.

However, subgroup analyses were not done due to the small number of studies and insufficient data available.

Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques. Where possible, the risk difference (RD) with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were done to explore the robustness of findings to key decisions in the review process. These were determined as the review process took place (Higgins 2022). Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore the influence of a study's risk of bias on the results.

Repeating the analysis, excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis, taking account of the risk of bias, as specified above

Repeating the analysis, excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeat the analysis, excluding studies, using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in Summary of findings tables. These tables present key information concerning the certainty of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2022a). The Summary of findings tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each main outcome using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2022b). We initially intended to present vascular access complications and fatigue in the summary of findings. However, there was insufficient data to meta‐analyse these outcomes. We therefore presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Cardiovascular death

All‐cause death

All‐cause hospitalisation

Kidney transplantation

HRQoL

Recovery time

BP.

Results

Description of studies

The following section contains broad descriptions of the studies considered in this review. For further details on each individual study, please see Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

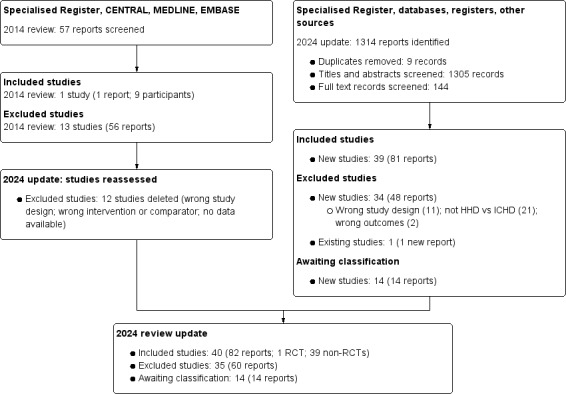

Results of the search

The search of databases and registers was conducted on 7 October 2022 and identified 1280 records; an additional 34 records were identified through other sources. After duplicate records were removed, 1305 studies were screened, and 144 records were selected for full‐text review. Of these, 39 new studies were included (81 records), 34 new studies were excluded (48 records), and 14 studies (14 records) are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We also identified one new report of an existing excluded study.

We reassessed and deleted 12 previously excluded studies (wrong study design, not HHD versus ICHD, no outcomes of interest).

A total of 40 studies were included (82 reports; 1 RCT, 39 NRSIs), 35 studies were excluded (60 reports), and 14 studies are awaiting classification. The search results are summarised in (Figure 1).

1.

2024 flow diagram for study selection

Included studies

One RCT, already included in the previous version of this systematic review, was included (McGregor 2001). The search did not find any additional RCTs. The search yielded 81 reports of 39 eligible NRSIs. Three of these studies were published as conference abstracts, with no related full article published (Bragg‐Gresham 2018; Dumaine 2018; Ha 2018). Included studies were published between 2001 and 2022, with half of the studies being published from 2015 onwards.

Various study designs were seen across the included studies. Many were small single‐centre prospective studies, cross‐sectional studies and large retrospective registry studies. Details on the design, setting and size of studies are shown in Table 3.

2. Design, setting and size of included studies.

| Study ID | Study setting | Study size |

| Ageborg 2005 | Prospective cohort study Cross‐sectional Stockholm (Sweden) |

HHD (5) Self‐care HD (6) Conventional ICHD (8) |

| Bragg‐Gresham 2018 | Retrospective cohort study USRDS – data available in the Medical Evidence Report 2006‐2015 |

Incident dialysis patients (156,377) |

| Dumaine 2018 | Prospective, mixed‐methods, pilot study Comparing transitions (from CKD to initiating dialysis or transition from one dialysis modality to another) |

CKD to ICHD (5) CKD to PD (9) CKD to HHD (2) PD to ICHD (2) PD to HHD (4) ICHD to PD (4) ICHD to HHD (7) |

| Griva 2010 | Cross‐sectional 2 dialysis units (affiliated with Royal Free and University College Hospitals), London (UK) |

HHD (25) ICHD (52) CAPD (45) APD (23) |

| Ha 2018 | Single‐centre, prospective cohort study Cross‐sectional Sydney (Australia) From 2015‐2017 |

HHD (27) PD (48) ICHD (113) Transplant recipients (85) |

| Hayhurst 2015 | Cross‐sectional Single‐centre, Royal Preston Hospital (UK) May‐June 2014 |

CKD stage 3‐5 (17) ICHD (28) HHD (17) PD (17) Transplant recipients (21) Controls: matched by age and sex (50) |

| Jayanti 2016 | Prospective study (BASIC‐HHD study); combined cross‐sectional and prospective study design Multi‐centre across 5 tertiary centres (UK) |

HHD (91) Prevalent ICHD (197) |

| Kasza 2016 | Observational cohort study ANZDATA Registry (Australia & New Zealand) 1 Oct 2003‐31 Dec 2011 |

ICHD CVC (7414) ICHD AVF (5729) HHD AVF (357) PD (6665) HHD CVC: not included in analysis (26) |

| Kojima 2012 | Observational cohort study, retrospectively collected data Single‐centre (Kidney Disease Center, Saitama Medical University, Japan) |

Patients transitioned from ICHD to HHD (54) |

| Krahn 2019 | Population‐based retrospective cohort study à linked registry (CORR) and administrative data Ontario (Canada) 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2014 |

HHD (112) ICHD (9687) short‐daily/slow nocturnal ICHD (65) PD (2827) |

| Kraus 2007 | Prospective, multicenter, open‐label, feasibility study 6 USA centres |

Patients transitioning from ICHD to HHD with NxStage System One (32) |

| Krishnasamy 2013 | Observational cohort study ANZDATA Registry (Australia & New Zealand) 1999‐2008 |

ICHD (9765) PD (4298) HHD (573) |

| Lee 2002 | Prospective cohort study South Alberta Renal Program (Calgary, Canada) 1999‐2000 |

HHD (9) ICHD (88) Satellite ICHD (31) PD (38) |

| Lorenzen 2012 | Retrospective, longitudinal, single‐centre study Kuratorium für Dialyse und Nierentransplantation (Hannover, Germany) |

Patients on maintenance dialysis transferring from ICHD to short daily HHD (11) |

| Malmstrom 2008 | Cross‐sectional (15 Oct 2004) and retrospective (year 2004) Single‐centre (Helsinki University Hospital), Helsinki (Finland) |

HHD (33) Satellite ICHD (32) |

| McGregor 2001 | Randomised crossover trial Single‐centre, New Zealand |

HHD patients assigned to receive short in‐centre HD and long HHD in a randomised sequence (9) |

| Murashima 2010 | Retrospective cohort study Single‐centre |

Patients converted from CHD to HHD (12) |

| Nebel 2002 | Retrospective cohort study Single‐centre, Cologne‐Merheim Hospital (Germany) 1990‐1999 |

HHD (37) Satellite ICHD (66) PD (69) Transplant recipients (72) |

| Nesrallah 2012 | Multinational renal databases: International Quotidian Dialysis Registry (IQDR) [intensive] + DOPPS [conventional] Secondary IQDR data from REIN registry (France), Fresenius Medical Care North America, PROMIS database (British Columbia, Canada) France, USA, Canada Between Jan 2000 and Aug 2010 |

Intensive HD (420) Conventional HD (5646) Matched patients by country, duration of ESKD before study enrolment and propensity score Intensive HD (338) Conventional HD (1388) |

| Nitsch 2011 | UK Renal registry England and Wales 1 Jan 1997‐31 Dec 2005 |

Incident HHD (225) Incident PD: matched by age and sex (900) Incident hospital ICHD: matched by age and sex (900) Incident satellite ICHD: matched by age and sex (450) |

| Piccoli 2004 | Prospective cohort study Single‐centre SMOM Unit (satellite of a large university centre) Turin (Italy) Nov 1998‐Nov 2002 |

HHD (at home or in training) (42) Limited care ICHD (35) |

| Rydell 2016 | Retrospective, observational case‐control study HHD: Lund University Hospital from 1 Jan 1983 to 31 Dec 2002 ICHD: Malmo General Hospital from 1 Jan 1978 to 31 Dec 2007 (Sweden) Data on dialysis from Swedish Renal Registry; survival data from Swedish Census |

Matched according to sex, age, comorbidity and date of start HHD (41 from 118) IHD (41 from 377) Followed until death or 1 Jan 2013; median follow up duration 14 years (HHD) and 11 years (IHD) |

| Sands 2009 | Retrospective study Fresenius Medical Services facilities (USA) 1 Nov 2006‐12 March 2007 |

Patients who transitioned from ICHD to HHD (29) |

| Saner 2005 | Nested case‐cohort study; retrospective chart analysis – For each patient trained for HHD at the dialysis centre between 1970 and 1995 corresponding match searched from ICHD by retrospective chart analysis Single‐centre (University Hospital of Berne), Bern (Switzerland) From 1970 to 1995 |

HHD (58) ICHD: matched for sex, age, time of dialysis onset and renal disease category (58) |

| Suri 2015 | Observational retrospective cohort study HHD patients from a large US dialysis provider’s administrative database – propensity score matched to contemporaneous USRDS patients Jan 2004‐Dec 2009 |

All adults who began DHD between 2004‐2009 HHD (1187) ICHD patients from USRDS (3173) |

| Tennankore 2022 | Canadian Organ Replacement Registry (CORR) analysis 2005‐2014 |

|

| Van Oosten 2018 | National data (Netherlands) Health insurance claims data from 2012‐2014 Data validated with external database (Dutch Renal Registry – Renine) |

HHD (197) ICHD (6463) CAPD (463) APD (477) Mix (281) Transplant recipients: living donor (1554) Transplant recipients: deceased donor (1275) |

| Watanabe 2014 | Prospective cohort study Cross‐sectional Single‐centre (Saitama Medical University Hospital), Saitama (Japan) 2011 |

HHD (46) ICHD: matched for age, sex, cause of ESKD (34) |

| Wong 2019a | Cross‐sectional data of ESKD patients pooled from the following studies:

Hong Kong *Chen JY, Choi EPH, Wan EYF et al. Validation of the disease‐specific components of the kidney disease quality of Life‐36 (KDQOL‐36) in Chinese patients undergoing maintenance dialysis. PLoS One 2016;11: e0155188. |

NHHD (41) PD (103) HICHD (135) CICHD (118) |

| Wong 2019b | Multi‐centre 3 public hospitals in Hong Kong Information from medical records + face‐to‐face interview with patients between May 2016 and Oct 2016 |

HHD (43) ICHD (170) PD (189) |

| Wright 2015 | Cross‐sectional Pilot study 4 outpatient dialysis facilities located in Pennsylvania (USA) |

HHD (22) ICHD (29) PD (26) |

| Xue 2015 | Retrospective cohort study HHD: Virginia Lynchburg Dialysis Facility (USA) from 1997 to 2010 ICHD: Fresenius Medical Care North America facilities in Virginia (USA) from 1 Jan 2007 to 31 Dec 2010 |

HHD (63) ICHD: matched by age, gender, race, dialysis vintage, diabetes (121) |

| Yeung 2021 | Prospective cohort study HHD: Single‐centre, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne (Australia) ICHD: ANZDATA Registry Jan 2000‐June 2017 |

HHD (181) ICHD: matched by age, gender and cause of ESKD (413) |

| Zimbudzi 2014 | Retrospective cohort study Single‐centre, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne (Australia) Aug 2012‐Aug 2013 |

HHD (25) ICHD: satellite HD (25) |

Note: refer to Table 4 for characteristics studies containing grouped reports.

AVF: arteriovenous fistula; AVG: arteriovenous graft; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVC: central venous catheter; ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; HD: haemodialysis; HHD: home haemodialysis; ICHD: in‐centre haemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis

In some cases, there were multiple publications generated from the same trial or study, which we have grouped together (Kjellstrand 2008; Rydell 2019; Tablo IDE 2020). In other cases, there were multiple publications which were generated from different studies but were performed within the same or overlapping populations. Marshall 2021 conducted multiple registry studies based on the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry and reporting on death. Populations included in these studies were overlapping over the period from 1996 to 2017. NxStage‐USRDS 2012 compared the HHD patients registry of NxStage System One users (NxStage Medical Inc) to matched patients from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) over the 2006 to 2012 period. Finally, there were instances of multiple studies being performed within the same clinical dialysis program over the same or overlapping time periods. Many studies comparing HHD to ICHD were conducted at the University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto, Canada, from 1993 to 2009. As we could not be certain that the populations included in these studies were not overlapping, all studies involving the UHN HHD unit were grouped as Toronto Group 2002. In the aforementioned situations of study grouping, data were extracted only from publications which reported outcomes relevant to this review. Where more than one publication from a study group reported a relevant outcome, the publication with the most complete data was used for analyses. Details on the design, setting and size of reports within study groups are shown in Table 4.

3. Characteristics of grouped reports within studies.

| Study/report | Study design and setting | Population | Study period | Outcomes |

| Kjellstrand 2008 | ||||

| Kjellstrand 2008* | Observational retrospective cohort study 5 centres from USA and Europe |

HHD or self‐care HD (265) ICHD (150) |

1982 to Jun 2005 | Survival (%) |

| Kjellstrand 2010 | Observational retrospective cohort study 5 centres from USA and Europe |

HHD (189) ICHD (73) |

1982 to Jun 2005 | Survival (%) |

| Marshall 2021 | ||||

| Marshall 2011 | Observational retrospective cohort study ANZDATA Registry |

HHD (3190) ICHD (21,968) |

31 Mar 1996 to 31 Dec 2007 | Death (HR for death) |

| Marshall 2013 | Observational retrospective cohort study ANZDATA Registry (NZ only) |

HHD (1532) ICHD (5647) |

31 Mar 2000 to 31 Dec 2010 | Death (HR for death) |

| Marshall 2014 | Observational retrospective cohort study ANZDATA Registry (NZ only) |

HHD (1547) ICHD (8713) |

1 Jan 1997 to 31 Dec 2011 | Death (HR for death) |

| Marshall 2016 | Observational retrospective cohort study ANZDATA Registry |

HHD (5764) ICHD (34,952) |

31 Mar 1996 to 31 Dec 2012 | Death (HR for death) |

| Marshall 2021* | Observational retrospective cohort study ANZDATA Registry |

Complete cohort: 52097 Modality comparison cohort: HHD (1236), ICHD (29,548) |

Complete cohort: 1998 to 2017 Modality comparison cohort: 2013 to 2017 |

Death (HR for death) Proportion cardiovascular death as cause of death |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 | ||||

| Kansal 2019 | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (521) ICHD: USRDS (32,931) |

2006 to 2012 | Survival (%) Death (HR for death) |

| Weinhandl 2012* | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (1873) ICHD: USRDS (9365) |

1 Jan 2005 to 31 Dec 2007 | All‐cause death (HR for death) Cardiovascular death (HR for death) Infection death (HR for death) Interval‐specific death (HR for death) |

| Weinhandl 2015a* | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (3480) ICHD: USRDS (17,400) |

1 Jan 2006 to 31 Dec 2009 | All‐cause hospital admissions (RR) Cardiovascular hospital admissions (RR) Vascular hospital admissions (RR) All‐cause hospital duration (RR) Cardiovascular hospital duration (RR) Vascular hospital duration (RR) |

| Weinhandl 2015b | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (834) ICHD: USRDS (4170) |

1 Jan 2007 to 30 Jun 2010 | Death (HR for death) Cardiovascular death (HR for death) Infection death (HR for death) |

| Weinhandl 2015c | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (3560) ICHD: USRDS (17,800) |

1 Jan 2007 to 30 Jun 2010 | 30‐day readmission after discharge for heart failure 30‐day readmission after discharge for hypertension |

| Weinhandl 2015d* | Observational retrospective cohort study NxStage Medical user registry linked to USRDS (USA) |

HHD: NxStage (1368) ICHD: USRDS (6840) |

1 Jan 2007 to 30 Jun 2010 | Relative incidence of transplant |

| Rydell 2019 | ||||

| Rydell 2019a* | Observational retrospective cohort study Swedish Renal Registry, Swedish Inpatient Registry and Swedish Mortality Database |

HHD (152) ICHD (608) |

1991 to 2012 | All‐cause death Median survival (years) |

| Rydell 2019b* | Observational retrospective cohort study Swedish Renal Registry, Swedish Inpatient Registry and Swedish Mortality Database |

HHD (152) ICHD (608) |

1991 to 2012 | All‐cause annual hospital admission rate All‐cause hospitalization days per patient‐year |

| Tablo IDE 2020 | ||||

| Chertow 2020* | Prospective cross‐over study Multicentre (USA) |

Cross‐over design (30) | Not specified | Recovery time (hours) EQ‐5D‐5L Sleep duration (hours) |

| Aragon 2020 | Awaiting classification: contact made with author | |||

| Chahal 2020a | Awaiting classification: contact made with author | |||

| Chahal 2020b | Awaiting classification: contact made with author | |||

| Plumb 2020 | Awaiting classification: contact made with author | |||

| Plumb 2021 | Awaiting classification: contact made with author | |||

| Toronto Group 2002 | ||||

| Bergman 2008* | Controlled cohort study Toronto (Canada) |

HHD (32) ICHD (42) |

1993 to 2003 | Dialysis or cardiovascular‐related admission (per patient year) Duration of dialysis or cardiovascular‐related admission (days per year) All‐cause hospitalisation (per patient year) Duration of all‐cause hospitalisation (days per year) Emergency department visits (per patient year) |

| Bugeja 2004 | Prospective observational cohort study University Health Network, Toronto (Canada) |

Cross‐over design (11) | Not specified | Systolic BP Diastolic BP |

| Cafazzo 2009 | Cross‐sectional survey of prevalent patients Toronto (Canada) |

HHD (56) ICHD (153) |

Not specified | Appraisal of Self‐Care Agency (ASA scale) SF‐12 (Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Anxiety State (Spielberger) Anxiety Trait (Spielberger) |

| Chan 2002 | Prospective observational cohort study University Health Network, Toronto (Canada) |

Cross‐over design (6) | Since Oct 1997; no end date specified | Mean systolic BP Mean diastolic BP LVMI (g/m2) |

| Chan 2003 | Prospective observational cohort study University Health Network, Toronto (Canada) |

Cross‐over design (18) | Not specified | Systolic BP Diastolic BP 24‐hour systolic BP 24‐hour diastolic BP |

| Chan 2005* | Cohort study Cross‐sectional University Health Network, Toronto (Canada) |

HHD (10) ICHD (12) |

Not specified | Systolic BP Diastolic BP Mean BP LVMI (g/m2) |

| Chan 2005a | Cohort study University Health Network, Toronto (Canada) |

Cross‐over design (10) | Not specified | Systolic BP Diastolic BP |

*outcome data utilised in analyses

BP: blood pressure; HHD: home haemodialysis; HR: hazard ratio; ICHD: in‐centre haemodialysis; LVMI: left ventricular mass index; RR: risk ratio

Intervention groups

Most compared groups were parallel, while a few studies used a non‐randomised, single‐cross‐over design in which each participant served as their own control in situations where patients were transitioning from one modality to another (Kojima 2012; Lorenzen 2012; McGregor 2001; Murashima 2010; Sands 2009; Tablo IDE 2020). While all studies compared some form of HHD to ICHD, some studies specified additional subgroups based on treatment duration/timing (e.g. intensive, conventional, nocturnal, daily), setting (e.g. satellite centre, community house), staff involvement (e.g. self‐care, limited care) or vascular access (CVC versus AVF/AVG). Many studies did not specify the treatment duration or did not define “intensive” or “conventional” duration. Additionally, some studies included other comparison groups (e.g. people treated with PD, recipients of a kidney transplant, people with earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and healthy controls). Details on intervention groups across studies are provided in Table 5.

4. Detailed intervention comparisons by study.

| Study ID/report | HHD | ICHD | Other comparisons |

| Ageborg 2005 | HHD (NS) | Self‐care ICHD ICHD: conventional |

‐ |

| Bragg‐Gresham 2018 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) Self‐care ICHD (NS) |

CAPD CCPD |

| Dumaine 2018 | Transition from ICHD to HHD | ‐ | Transition from CKD to ICHD Transition from CKD to PD Transition from CKD to HHD Transition from PD to IHD Transition from PD to HHD Transition from ICHD to PD |

| Griva 2010 | HHD: conventional; 3 times/week) | ICHD (NS) | CAPD APD |

| Ha 2018 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD Transplant recipient |

| Hayhurst 2015 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD CKD stages 3‐5 Transplant recipients Controls (healthy) |

| Jayanti 2016 | Intensive HHD: 30.8% conventional HHD; variable dialysis prescriptions | ICHD: conventional; 12 hours/week; 54% HDF | ‐ |

| Kasza 2016 | HHD: AVF/AVG | ICHD: CVC ICHD: AVF/AVG |

PD |

| Kjellstrand 2008 | Intensive HHD: short daily | Intensive ICHD: short daily | Survival probabilities derived from 2005 USRDS incident HD population |

| Kojima 2012 | Intensive HHD | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Krahn 2019 | HHD: short daily (2 to 3 hours; 6 to 7 times/week (awake)) or slow nocturnal (6 to 9 hours; 5 to 7 times/week) Canadian Organ Replacement Register |

ICHD: conventional Intensive ICHD: short daily (2 to 3 hours; 6 to 7 times/week (awake)) or slow nocturnal (6 to 9 hours; 5 to 7 time/week Canadian Organ Replacement Register |

PD (CAPD or APD) |

| Kraus 2007 | Intensive HHD: 2 to 3 hours; 6 times/week (NxStage System One) | Intensive ICHD: 2 to 3 hours; 6 times/week (NxStage System One) | ‐ |

| Krishnasamy 2013 | HHD: mix of intensive and conventional | ICHD: 97% conventional | PD |

| Lee 2002 | HHD/self‐care: ≥ 4 hours/session; ≥ 3 times/week | ICHD: ≥ 4 hours/session; ≥ 3 times/week Satellite HD: ≥ 4 hours/session; ≥ 3 times/week |

PD (CAPD and APD) |

| Lorenzen 2012 | Intensive HHD: short daily | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Malmstrom 2008 | HHD: flexible schedule and length of dialysis | Self‐care satellite HD: 3 times/week | ‐ |

| Marshall 2021 / Marshall 2011 | HHD: conventional Intensive HHD: frequent/extended; > 3 sessions of ≥ 4 hours or 3 sessions of > 6 hours or 5 sessions of ≥ 3 hours or > 5 sessions of ≥ 2 hours per week |

ICHD: conventional Intensive ICHD: frequent/extended; > 3 sessions of ≥ 4 hours or 3 sessions of > 6 hours or 5 sessions of ≥ 3 hours or > 5 sessions of ≥ 2 hours per week |

PD |

| Marshall 2021 / Marshall 2013 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | Community house HD PD |

| Marshall 2021 / Marshall 2014 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD |

| Marshall 2021 / Marshall 2016 | Intensive HHD: any hours/session; ≥ 5 times/week Quasi‐intensive HHD: between conventional and intensive HHD: conventional; ≤ 3 times /week; ≤ 6 hours/session |

Intensive ICHD: any hours/session; ≥ 5 times/week Quasi‐intensive ICHD: between conventional and intensive ICHD: conventional; ≤ 3 times /week; ≤ 6 hours/session |

PD Deceased donor transplant recipient Living donor transplant recipient |

| Marshall 2021 / Marshall 2021 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | CAPD APD |

| McGregor 2001 | HHD: 6 to 8 hours/session; 3 times/week | ICHD: 3.5 to 4.5 hours/session; 3 times/week | ‐ |

| Murashima 2010 | Intensive HHD: short daily (NxStage System One) | ICHD: 3 times/week) | ‐ |

| Nebel 2002 | HHD (NS) | Satellite HD (NS) | PD (CAPD and APD) Kidney transplant recipient Inpatient acute ICHD (reported but not analysed due to low numbers) |

| Nesrallah 2012 | Intensive HHD: ≥ 5.5 hours/session; 3 to 7 times/week; day or nocturnal International Quotidian Dialysis Registry (none with NxStage) |

ICHD: conventional; < 5.5 hours/session; 3 times/week | ‐ |

| Nitsch 2011 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) Satellite HD (NS) |

PD |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Kansal 2019 | Intensive HHD: previously receiving PD; 92% prescribed 5 to 6 times/week | ICHD: previously receiving PD (USRDS) | ‐ |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Weinhandl 2012 | Intensive HHD: daily (NxStage System One) | ICHD: conventional; 3 times/week (USRDS) | ‐ |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Weinhandl 2015a | Intensive HHD: daily; 5 to 6 times/week (NxStage System One) | ICHD: conventional; 3 times/week | ‐ |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Weinhandl 2015b | Intensive HHD: daily (NxStage System One) | ICHD: conventional (USRDS) | ‐ |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Weinhandl 2015c | Intensive HHD: daily (NxStage System One) | ICHD: conventional (USRDS) | PD |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 / Weinhandl 2015d | Intensive HHD: daily (NxStage System One) | ICHD: conventional (USRDS) | PD |

| Piccoli 2004 | HHD: not daily Intensive HHD: daily) |

Limited care ICHD: not daily Intensive limited care ICHD: daily |

‐ |

| Rydell 2016 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | ‐ |

| Rydell 2019 / Rydell 2019a | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD |

| Rydell 2019 / Rydell 2019b | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD |

| Sands 2009 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | ‐ |

| Saner 2005 | HHD (NS): same prescription at home then in‐centre | ICHD (NS) same prescription at home then in‐centre | ‐ |

| Suri 2015 | Intensive HHD: daily; 1.5 to 4.5 hours/session; > 5 times/week | ICHD: conventional | PD |

| Tablo IDE 2020 / Chertow 2020 | Intensive HHD: 4 sessions/week | Intensive ICHD: 4 sessions/week | ‐ |

| Tennankore 2022 | HHD Intensive HHD: frequent |

ICHD Intensive ICHD: frequent |

PD |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Bergman 2008 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Bugeja 2004 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal; 6 to 8 hours/session; 5 to 6 times/week) | ICHD: conventional; 4 hours/session; 3 t imes/week | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Cafazzo 2009 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal; 6 to 8 hours/session; 4 to 6 times/week | ICHD: conventional; 4 hours/session; 3 times/week | Predialysis included in qualitative interviews |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Chan 2002 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Chan 2003 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal; 8 to 10 hours/session; 6 times/week) | ICHD: conventional; 4 hours/session; 3 times/week | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Chan 2005 | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 / Chan 2005a | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Van Oosten 2018 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | CAPD APD Deceased donor transplant recipient Living donor transplant recipient Mix: multiple dialysis modalities in a year |

| Watanabe 2014 | Intensive HHD: 3 to 5 hours/session; 5 to 6 times/week; no nocturnal treatment; large segment had previously undergone PD or PD+HD combined therapy; AVF for all | ICHD: 3 to 5 hours/session; 3 times/week; AVF for all | ‐ |

| Wong 2019a | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: (NS); hospital‐based Satellite HD (NS); community in‐centre |

PD |

| Wong 2019b | Intensive HHD: nocturnal | ICHD: (NS); hospital‐based | PD |

| Wright 2015 | HHD (NS) | ICHD (NS) | PD |

| Xue 2015 | Intensive HHD: frequent nightly | ICHD: conventional | ‐ |

| Yeung 2021 | HHD: 6 to 8 hours/session; alternate days | ICHD: 4 to 5 hours/session; 3 times/week | ‐ |

| Zimbudzi 2014 | Intensive HHD: > 75% 8 hours alternate days | Satellite HD patients on Category 1 transplant waitlist: 5 hours/session; 3 times/week | ‐ |

AVF/AVG: arteriovenous fistula/arteriovenous graft; CCPD: continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis; CVC: central venous catheter; HHD: home haemodialysis; ICHD: in‐centre haemodialysis; NS: (duration and frequency) not specified; PD: peritoneal dialysis; APD: automated PD; CAPD: continuous ambulatory PD

Tablo IDE 2020 specifically evaluated the Tablo HD device at home and in‐centre, while NxStage‐USRDS 2012 (and related reports) evaluated the use of the NxStage dialysis system in HHD compared to ICHD based on matched cohorts from USRDS. In contrast, another study from the USA, where the NxStage System is more broadly used, specified that this device was not used in their study (Nesrallah 2012). However, most studies did not provide details on the type of machine used or other dialysis parameters (e.g. vascular access, blood flow rate).

Specific definitions and prescription details (e.g. duration, frequency) of the HHD and ICHD groups were not always provided. In registry analyses, which included incident patients starting HD, some studies defined groups according to the modality 90 days after dialysis initiation (Marshall 2021) or the current modality at the time of the event of interest (Krishnasamy 2013), whereas others did not describe how groups were defined. Moreover, modality transfers were addressed differently across studies. Some studies used ITT (dialysis modality modelled as fixed) and as‐treated (dialysis modality modelled as time‐varying) frameworks, whereas others censored patients at modality switch.

Reported outcomes

Most studies reported outcomes of interest from only one category (clinical, patient‐reported, health economics or surrogate outcomes) (Table 6). No studies specifically reported on non‐fatal MI, non‐fatal stroke, parathyroidectomy or fatigue. Employment after the commencement of dialysis was reported in Helantera 2012; however, this study included patients from the age of 15 years, and data for adult patients could not be extracted separately. The metrics used to report outcomes were highly variable across studies. For example, vascular access‐related outcomes were reported as vascular access event‐free survival (Piccoli 2004), access complications (Sands 2009), vascular access surgery (Saner 2005) and catheter‐related sepsis (Xue 2015). Similarly, hospitalisation was reported as hospital admission rate (NxStage‐USRDS 2012; Rydell 2019; Suri 2015; Tennankore 2022; Toronto Group 2002), mean number of hospitalisations/patient (Saner 2005), hospitalisation days (NxStage‐USRDS 2012; Rydell 2019; Suri 2015; Toronto Group 2002; Zimbudzi 2014), number of patients experiencing a hospitalisation event (Sands 2009), and number of hospitalisation events in the study (Suri 2015; Tennankore 2022; Zimbudzi 2014). Despite attempts to gain further data from authors, measures of variability (SD, standard errors or IQR) were unobtainable for continuous outcomes in many studies. Likewise, many studies provided the total number of events overall for dichotomous outcomes but did not provide the number of events per treatment arm. In these situations, the study outcomes were unable to be included in the meta‐analyses.

5. Reported outcomes of interest by study.

| Study ID | Clinical outcomes | Patient‐reported outcomes | Health economics outcomes | Surrogate outcomes |

| Ageborg 2005 | ‐ | SF‐36 (physical functioning, role‐physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role‐emotional, mental health) Appraisal of Self‐Care Agency (ASA scale) Sense of Coherence (SOC) questionnaire |

‐ | ‐ |

| Bragg‐Gresham 2018 | ‐ | Employment prior to dialysis initiation (6 months, %) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Dumaine 2018 | ‐ | KDQOL‐SF (Symptoms and Problems, Effects of Kidney Disease, Burden of Kidney Disease, Physical Component Summary, Mental Component Summary) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Griva 2010 | ‐ | Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (Identity score) Illness Effects Questionnaire Treatment Effects Questionnaire Beck Depression Inventory‐II Cognitive Depression Index |

‐ | ‐ |

| Ha 2018 | ‐ | iPOS‐Renal | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hayhurst 2015 | ‐ | Maximum activity score Total activity score Activity loss score |

‐ | ‐ |

| Jayanti 2016 | ‐ | Recovery time (hours) | ‐ | Proportion of patients with systolic BP >115 mm Hg Proportion of patients with diastolic BP > 85 mm Hg |

| Kasza 2016 | Unadjusted survival (number at risk) Death (HR for death) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kjellstrand 2008 | Death (HR for death) Survival (HR by modality) |

‐ | ‐ | |

| Kojima 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Pre‐dialysis systolic BP LVMI |

| Krahn 2019 | Unadjusted survival (number at risk) | ‐ | 30‐day costs (CAD) Cumulative costs (CAD) |

‐ |

| Kraus 2007 | ‐ | KDQOL‐SF | ‐ | Systolic BP Diastolic BP Pulse pressure |

| Krishnasamy 2013 | Day of week as predictor of cardiac death (adjusted OR) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Lee 2002 | ‐ | ‐ | Annual total health‐care related costs per patient (USD) Annual outpatient dialysis costs (USD) Annual inpatient costs (USD) Total outpatient costs (USD) Annual physician billing costs (USD) |

‐ |

| Lorenzen 2012 | ‐‐ | ‐ | Pre‐dialysis MAP Post‐dialysis MAP |

|

| Malmstrom 2008 | ‐ | 15D | Annual hospital costs (EUR) Annual total health‐care‐related costs per patient (EUR) |

Pre‐dialysis systolic BP Post‐dialysis systolic BP Pre‐dialysis diastolic BP Post‐dialysis diastolic BP |

| Marshall 2021 | Death (HR for death) Proportion cardiovascular death as cause of death |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| McGregor 2001 | ‐ | Symptoms and quality of life (uraemia‐related symptoms, physical suffering, interference with social activity, burden on families) | ‐ | Pre‐dialysis BP Post‐dialysis BP Ambulatory BP Symptomatic hypotension LVMI |

| Murashima 2010 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Pulse pressure Incidence of intradialytic hypotension (OR) Clinically significant hypotension during dialysis (OR) |

| Nebel 2002 | ‐ | ‐ | Annual healthcare costs (DM) | ‐ |

| Nesrallah 2012 | Death(HR for death) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nitsch 2011 | 1‐year survival (%) Survival after KRT start (HR) Long‐term survival (HR) Waitlisting for kidney transplantation before KRT start (OR) Waitlisting for kidney transplantation after KRT start (HR) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| NxStage‐USRDS 2012 | All‐cause death (HR for death) Cardiovascular death (HR for death) Infection death (HR for death) Interval‐specific death (HR for death) All‐cause hospital admissions (RR) Cardiovascular hospital admissions (RR) All‐cause hospital duration (RR) Cardiovascular hospital duration (RR) 30‐day readmission after discharge for heart failure 30‐day readmission after discharge for hypertension Relative incidence of transplant Survival (%) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Piccoli 2004 | Adverse event‐free survival Vascular access event‐free survival |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Rydell 2016 | Mean survival (years) Survival (%) Number of patients who received a kidney transplant |

‐ | ‐ | Mean systolic BP Mean diastolic BP |

| Rydell 2019 | Median survival (years) All‐cause annual hospital admission rate Hospitalisation (days per year) Time to hospitalisation (years) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sands 2009 | Hospitalisations (per 100 treatments) Arterial site access complications (per 100 treatments) Venous site access complications (per 100 treatments) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Saner 2005 | Survival (%) Cardiovascular death during study Vascular access surgery (per patient) All‐cause hospitalisation (per patient) Number of patients who received a kidney transplant during study |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Suri 2015 | Composite hospitalisation (HR) Composite hospitalisation rate (per patient‐year) Time to first hospitalisation (HR) Cardiovascular hospitalisations (HR) Access‐related hospitalisations (HR) Access infection‐related hospitalisations (HR) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tablo IDE 2020 | Recovery time (hours) EQ‐5D‐5L Sleep duration (hours) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tennankore 2022 | All‐cause hospital admissions (per 1000 patient‐days) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Toronto Group 2002 | Dialysis or cardiovascular related admission (per patient year) Duration of dialysis or cardiovascular related admission (days per year) All‐cause hospitalisation (per patient year) Duration of all‐cause hospitalisation (days per year) |

Modified Appraisal of Self‐Care Agency (ASA) subscale SF‐12 (Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Anxiety State (Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults) |

Mean systolic BP Mean diastolic BP Mean BP 24‐hour systolic BP 24‐hour diastolic BP LVMI |

|

| Van Oosten 2018 | ‐ | ‐ | Annual RRT costs (EUR) Annual healthcare costs (EUR) |

‐ |

| Watanabe 2014 | ‐ | SF‐36 (physical functioning, role‐physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role‐emotional, mental health; Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary) KDQOL (Symptoms and Problems, Effects of Kidney Disease, Burden of Kidney Disease, Work Status, Cognitive Function, Quality of Social Interaction, Sexual Function, Sleep) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Wong 2019b | ‐ | SF‐12 (physical functioning, role‐physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role‐emotional, mental health; Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wong 2019a | Annual hospitalisation utilisation (IRR) | ‐ | First year direct cost (HKD) Second year direct cost (HKD) Yearly indirect cost (HKD) First year societal cost (HKD) Second year societal cost (HKD) First year healthcare provider cost (HKD) Second year healthcare provider cost (HKD) |

‐ |

| Wright 2015 | ‐ | KDQOL‐SF (Symptoms and Problems, Effects of Kidney Disease, Burden of Kidney Disease, Work Status, Cognitive Function, Quality of Social Interaction, Sexual Function, Sleep, Social support, Dialysis staff encouragement, Patient satisfaction, Overall health) SF‐12 (Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary) SUPPH (positive attitude, stress reduction, decision making) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Xue 2015 | Death rate (per 100 patient‐months) Catheter‐related sepsis (per 100 patient‐months) Catheter‐related sepsis (HR) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Yeung 2021 | Death (HR for death) Transplantation rate |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Zimbudzi 2014 | Number of patients hospitalised Hospital admissions (days per patient‐year) Mean length of stay hospitalisation (days) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

BP: blood pressure; HR: hazard ratio; IRR: incidence rate ratio; KDQOL‐SF: Kidney Disease Quality of Life Instrument Short Form; KRT: kidney replacement therapy; LVMI: left ventricular mass index; MAP: mean arterial pressure; OR: odds ratio;SF‐12: 12‐Item Short Form Survey; SF‐36: 36‐Item Short Form Survey; Short form; SUPPH: Strategies Used by People to Promote Health

Patient‐reported outcome measures were reported in a wide variety of ways, encompassing measures of QoL (SF‐12, SF‐36, KDQOL‐SF, SF‐6D, EQ‐5D‐3L, 15D), mental health (Beck Depression Inventory‐II (BDI‐II), Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory; Cognitive Depression Index), symptoms (IPOS‐Renal), impact and view of health (Sense of Coherence (SOC) questionnaire, Strategies Used by People to Promote Health (SUPPH), Illness Perceptions Questionnaire, Illness Effects Questionnaire, Treatments Effects Questionnaire, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Support), functional ability (ASA scale, activity score), and recovery time.

Due to variations in how outcomes were defined and reported by studies, pooled analysis was only possible for a few reported outcomes.

Cardiovascular death (2 studies)

All‐cause death (9 studies)

All‐cause annual hospitalisation rate (2 studies)

All‐cause hospitalisation days per patient‐year (2 studies)

Kidney transplantation during the study period (6 studies)

Physical functioning, role‐physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role‐emotional, and mental health domains of the SF‐12 or SF‐36 (2 studies)

Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary of the SF‐12 or SF‐36 (5 studies)

Symptoms and problems, effects of kidney disease, burden of kidney disease, work status, cognitive function, quality of social interaction, sexual function and sleep domains of the KDQOL‐SF (2 studies)

BDI‐II (2 studies)

Recovery time (2 studies)

Healthcare costs (4 studies)

SBP (4 studies)

DBP (3 studies)

MAP (2 studies)

LVM index (2 studies).

Outcomes that were reported in a manner permitting extraction and analysis are demonstrated in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10.