Abstract

Purpose:

The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) study is a randomized clinical trial designed to determine the effects of a best-practice hearing intervention versus a successful aging health education control intervention on cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults with untreated mild-to-moderate hearing loss. We describe the baseline audiologic characteristics of the ACHIEVE participants.

Method:

Participants aged 70–84 years (N = 977; Mage = 76.8) were enrolled at four U.S. sites through two recruitment routes: (a) an ongoing longitudinal study and (b) de novo through the community. Participants underwent diagnostic evaluation including otoscopy, tympanometry, pure-tone and speech audiometry, speech-in-noise testing, and provided self-reported hearing abilities. Baseline characteristics are reported as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables or medians (interquartiles, Q1–Q3) for continuous variables. Between-groups comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. Spearman correlations assessed relationships between measured hearing function and self-reported hearing handicap.

Results:

The median four-frequency pure-tone average of the better ear was 39 dB HL, and the median speech-in-noise performance was a 6-dB SNR loss, indicating mild speech-in-noise difficulty. No clinically meaningful differences were found across sites. Significant differences in subjective measures were found for recruitment route. Expected correlations between hearing measurements and self-reported handicap were found.

Conclusions:

The extensive baseline audiologic characteristics reported here will inform future analyses examining associations between hearing loss and cognitive decline. The final ACHIEVE data set will be publicly available for use among the scientific community.

Supplemental Material:

Epidemiologic studies indicate that hearing loss is independently associated with accelerated cognitive decline and dementia. A recent Lancet global commission on dementia analysis found hearing loss potentially accounts for the largest population attributable risk among modifiable risk factors for dementia. Specifically, the report suggests nearly 8% of dementia cases across the globe could be attributable to hearing loss (Livingston et al., 2020). Evidence linking hearing loss and cognition has been obtained from self-reported and measured cognition (e.g., standardized neurocognitive test batteries designed to assess domains of attention, memory, language, processing speed, visuospatial, and executive functions), as well as self-reported and measured hearing (e.g., pure-tone thresholds) loss. A meta-analysis including three studies examining the relationships between measured hearing loss and standardized cognitive measures estimated a pooled relative risk ratio of 1.94 (95% confidence interval [CI; 1.38, 2.73]), indicating an increased likelihood developing dementia among included persons with measured peripheral hearing loss (Livingston et al., 2017).

A number of mechanisms seek to explain the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Lin & Albert, 2014; Powell et al., 2021; Wayne & Johnsrude, 2015). These hypothesized mechanisms include (a) increased cognitive load, (b) structural changes in the brain as a result of the degraded auditory signal, and (c) impaired verbal communication leading to reduced social engagement and increases in loneliness. Importantly, these mechanistic pathways may be modifiable with comprehensive hearing loss treatment, the cornerstone of which is the use of hearing aids. Determining the efficacy of hearing loss intervention on cognitive decline is of high importance given the aging of the population and the personal, socioeconomic, and public health implications of both hearing loss and cognitive impairment in older adults (Livingston et al., 2020). Findings from studies investigating the relationships between hearing device use and cognition are mixed, with some individual studies demonstrating positive results (e.g., Dawes et al., 2015; Maharani et al., 2018) and some showing no relationship (Atef et al., 2023). Recently reported results of a meta-analysis pooling data across 19 observational studies and four trials found the use of hearing restorative devices (hearing aids; cochlear implants) was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive decline. Despite this finding, the authors highlighted the need to examine cognitive and other proximal benefits in randomized trials to better understand this relationship (Denham et al., 2023; Yeo et al., 2023).

A recently completed clinical trial, referred to as the “Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders” (ACHIEVE Study) is investigating the effect of best practice hearing intervention on cognitive decline, dementia, and other health outcomes. The ACHIEVE Study was designed to determine the effects of a best practices hearing intervention compared to a health education control intervention. The hearing intervention included four 1-hr sessions with a study audiologist where participants received systematic, yet personalized, hearing counseling and self-management support in addition to bilateral prescriptive-fit hearing aids and other hearing-assistive technologies (Sanchez et al., 2020). Participants assigned to the health education active control also completed four 1-hr intervention sessions with a certified health educator who discussed healthy aging, chronic disease, and disability prevention, per the standardized administration of the 10 Keys to Healthy Aging program (Newman et al., 2010).

The ACHIEVE protocol details are reported elsewhere (Deal et al., 2018) and included on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03243422), but, briefly, the trial recruited community-dwelling older adults with untreated mild-to-moderate hearing loss between 2018 and 2019 from four study sites located in the United States. Participants were recruited either from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) longitudinal observational study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00005131), which begin in 1987, or de novo from the local study site communities. The ARIC study is a prospective cohort study that enrolled 15,792 participants aged 45–64 years between 1987 and 1989 (ARIC, 1989; Wright et al., 2021) who have been continuously followed with study visits to the present. Participants recruited to the ACHIEVE Study were English-speaking adults between 70 and 84 years old and measured to be free from substantial cognitive impairment with a Mini-Mental State Examination (Arevalo-Rodriguez et al., 2021) ≥ 23 for high school degree or less ≥ 25 for some college or more. Participants reported adult-onset hearing loss that was measured (four-frequency pure-tone average [PTA; 500, 1000, 2000, 4000 Hz]) in the better-hearing ear to be ≥ 30 dB (dB HL) and < 70 dB HL with word recognition in quiet performance ≥ 60%. The degree and configuration of hearing loss was selected to allow for recruitment of individuals most likely to benefit from the use of conventional hearing aids (Humes, 2019; Stevens et al., 2011). Participants were randomized to receive either a best-practices hearing intervention (Sanchez et al., 2020) or a successful aging health education control intervention (Newman et al., 2010), and followed with semi-annual visits for 3 years. The primary outcome of the study evaluated rates of cognitive decline (measured global cognitive function; Lin et al., 2023). Additional analyses and dissemination of the results are forthcoming, with secondary cognitive outcomes including domain-specific cognitive declines (memory, executive function, and language) and incident cognitive impairment, and other outcomes including brain structure on magnetic resonance imaging, health-related quality of life, physical and social function, and physical activity.

The purpose of this work is to provide a comprehensive description of the baseline audiological characteristics of the ACHIEVE participants. Baseline characteristic reports are important to thoroughly describe the patient population enrolled in a clinical trial, especially in multidisciplinary and large-scale trials that cannot allow for such details to be reported in their outcome reports. Examples of similar baseline characteristics reports are commonly reported in the literature of large-scaled multisite trials, such as for treatments for cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, and diabetes (Mentz et al., 2017; Pfeffer et al., 2009). Included in this report of the enrolled ACHIEVE participants are hearing function and performance data (e.g., audiometry, word recognition in quiet performance, speech perception in noise) and self-reported hearing difficulty and hearing handicap. We review differences among audiologic results based on geographical location (e.g., study sites) and related to recruitment route (e.g., ARIC vs. de novo). Through our goal of thoroughly reporting the baseline hearing characteristics, we have a complete understanding of the cohort's hearing, and we will comment on the baseline characteristics with respect to the hearing intervention that was designed for the trial. This report thoroughly characterizing the audiological results will serve as one of several descriptive, genre-specific baseline papers, intended to offer deep complementary information for interpreting the main trial results and all outcome papers forthcoming. The work presented here will enrich future analyses evaluating the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline, and these data, as well as the broader ACHIEVE data set, will become publicly available to the scientific community once the main ACHIEVE study results are published in 2023–2024.

Method

Study Design, Setting, Recruitment, and Participant Demographics

The ACHIEVE Study is a randomized Phase III clinical trial to determine the effects of a best-practice hearing intervention versus a successful aging health education control intervention on cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults with untreated mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Full details of the ACHIEVE study design were described elsewhere (Deal et al., 2018). The study is supported by seven institutions: Johns Hopkins University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of South Florida, University of Pittsburgh, University of Minnesota, Wake Forest University, University of Mississippi Medical Center; with the four university-affiliated study sites located in Washington County, Maryland (MD); Jackson, Mississippi (MS); Forsyth County, North Carolina (NC); and Minneapolis, Minnesota (MN). The institutional review boards at all centers reviewed and approved the study protocol. There were no participant costs for the interventions provided as part of the protocol, and paid transportation to and from the study center was provided for participants if needed. Participants received monetized compensation for each study visit completed.

At the study sites, participants were recruited either from the ongoing ARIC study, or de novo from the local study site communities. Local study site recruitment methods included clinic referrals and advertisements posted throughout the community and via online forums. Recruitment through the ARIC study was targeted, with previous hearing loss data available for review. ARIC participants were directly contacted about the opportunity to join the ACHIEVE study either through mail, telephone, or at their next preplanned ARIC study visit (i.e., ARIC Visit 7, which was ongoing at the time of ACHIEVE study enrollment [ARIC, 1989]). Participants completed a screening and baseline visit, four intervention visits, and then were seen semi-annually and annually for the next 3 years.

At the screening visit, participants completed questionnaires that captured health history, demographics, education, and other social determinants of health. Sex and race/ethnicity were self-reported using federal guidelines in existence at that time. Participants self-reported sex, as either male or female, rather than gender. Questionnaire items related to hearing history included the presence/absence of tinnitus, noise exposure, and history of otologic disorders.

Audiological Evaluation

High-level overviews of the ACHIEVE comprehensive audiological evaluation, including audiometric-related inclusion/exclusion criteria, are available in the literature (Deal et al., 2018; Sanchez et al., 2020). The objective of the audiological evaluation was to quantify the type and magnitude of hearing loss and confirm participant candidacy for the hearing intervention designed for the ACHIEVE Study. The intervention, described in detail by Sanchez et al. (2020), is evidence-based and utilizes conventional hearing aids as a key component, along with goal setting, hearing-assistive technologies, counseling, education and self-support management, and hearing-related outcomes assessment. If the results of the audiological evaluation were suggestive of a possible conductive or retrocochlear condition, medical assessment and clearance for use of conventional hearing aids was required. All audiological assessments were conducted in single-walled, 7 × 7 sound-attenuating WhisperRooms at each site using Interacoustics Equinox 2.0 AC440 diagnostic, two-channel audiometers. Guidelines were followed for routine equipment calibration, maintenance, and sound-field specifications (American National Standards Institute, 1999, 2018) at each site.

Assessment of the Outer and Middle Ear Status

Otoscopy was completed to view the structure of the ear canal and tympanic membrane. The audiologist determined the potential for a collapsing ear canal, evaluated the presence of cerumen and need for self-management or professional removal of cerumen, or other problems (e.g., perforation, drainage, blood) that may interfere with audiometric testing. Additionally, tympanometry with a 226-Hz probe frequency was obtained with an Interacoustics Titan middle ear analyzer (Version 1). Tympanometry was completed to evaluate the physiological function of the middle ear. Site audiologists determined and reported the tympanogram tracings as normal (Type A) or abnormal (types: AS, AD, B, or C).

Assessment of Pure-Tone Sensitivity

Pure-tone air- and bone-conduction thresholds were obtained using a modified Hughson and Westlake (1944) psychophysical bracketing method (Carhart & Jerger, 1959). Air-conduction thresholds were measured at octaves from 250 to 8000 Hz, including the interoctave frequencies of 3000 and 6000 Hz. Pulsed tones were used with E-A-R 3A insert earphones, unless otherwise indicated. Bone-conduction thresholds were measured at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. Masking, using plateau method (Hood, 1960), for both air- and bone- conduction thresholds was completed if needed based on transducer-specific interaural attenuation levels. If the audiologist indicated there was “no response” at a given frequency (i.e., a measurable threshold could not be obtained due to limits of the audiometer), the audiologists indicated they could not measure that threshold and noted the limits of the audiometer that was attempted.

Assessment of Speech Recognition

As a criterion for the potential to successfully utilize hearing aids, participants were required to have word recognition performance in quiet greater than 60% in at least one ear for inclusion (based on criteria from Humes, 2019). Word recognition in quiet testing was performed using recorded speech stimuli to determine the participant's optimal performance under controlled, standardized conditions and to reveal any asymmetry in performance not uncovered by pure-tone audiometry. Word recognition in quiet stimuli were Northwestern University Auditory Test No. 6 ordered-by-difficulty monosyllables (Hurley & Sells, 2003) presented monaurally at a sensation level referenced to the 2000-Hz threshold that is a presumed optimal listening level (Guthrie & Mackersie, 2009). Based on recognition performance of the first 10 administered words and following the ordered-by-difficulty procedures, either just 10 words or 25 words were presented to each ear. Masking of the nontest ear was used, as needed, presented at 20 dB below the presentation level of the speech stimuli (Hood, 1960; Studebaker, 1967). E-A-R 3A insert earphones were used unless otherwise indicated. Scoring was determined by tallying the participant's correctly repeated words and was recorded as percentage correct scores. Speech recognition threshold (SRT) measurement with spondaic words was completed at the discretion of the audiologist, specifically to confirm reliability of pure-tone thresholds.

Speech recognition in noise performance was assessed in sound field using the Quick Speech-in-Noise Test (QuickSIN; Killion et al., 2004; Etymōtic Research, 2001). The QuickSIN consists of a series of lists of six sentences, with five target words per sentence, spoken by a woman talker, mixed with multitalker speech babble that increases in 5-dB increments with each consecutive sentence presentation, for a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) varying from 25 dB to 0 dB. The QuickSIN test was administered with Channel 1 and Channel 2 routed to separate RadioEar SP90 speakers. The sound-field environment was calibrated daily in dB SPL using the substitution method (Walker et al., 1984). Sentences were presented on Channel 1 at 0° azimuth using a fixed level of 70 dB SPL. Multitalker babble was presented on Channel 2 at 180° azimuth, manually adjusting the SNR from 25 dB to 0 dB in 5-dB increments. The most homogeneous QuickSIN lists were used in the ACHIEVE study (McArdle & Wilson, 2006). Participants were presented a practice list and then two test lists (Lists 1 and 2) for a total of 60 possible target words to recognize. Scoring was determined by tallying the participant's correctly repeated target words for each test list. The total correctly recognized words were summed to determine number of target words correctly recognized across both lists and all SNRs, allowing for a percentage correct calculation (e.g., number correct out of 60 possible target words). In addition, using the normalized threshold calculation based on the Spearman–Kärber equation (Killion et al., 2004), the “dB SNR Loss” was calculated using the average performance from the two test lists.

Self-Report Hearing Ability

Two self-report measures were used to assess subjective hearing ability, and both were completed in a face-to-face format. First, participants answered the single six-item Likert-type question from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (Question AUQ054; CDC, 2023). This NHANES-developed question is often adopted by others (e.g., Dillard et al., 2022; Marrone et al., 2019) and asks, “Which statement best describes your hearing? Would you say your hearing is:” with response options of: excellent, good, a little trouble, moderate trouble, a lot of trouble, and deaf. The second approach involved the use of a standardized measure of hearing handicap, the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly–Screening Version (HHIE-S; Ventry & Weinstein, 1983), The HHIE-S is a validated and highly reliable (r = .97) 10-item questionnaire that measures perceived hearing handicap. HHIE-S scores range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater self-perceived handicap, and the total scores can be categorized into no handicap (0–8), mild–moderate handicap (10–24), and severe handicap (26–40). A total score of 10 or greater is suggestive of significant self-perceived hearing handicap (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 1997).

Quality Control of Data, Database Management, and Statistical Analysis

An extensive quality assurance and quality control protocol was designed for the ACHIEVE Study. As described in detail elsewhere (Arnold et al., 2022), the comprehensive audiological evaluation was completed by licensed, nationally certified audiologists who completed training in ACHIEVE hearing-related protocol administration. Audiological procedures were monitored through direct observation and validating data entry, ensuring fidelity across the study sites. After the baseline data were captured in the electronic database, the data coordinating center, located at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, completed a database review followed by a database lock. During the database review process, data were assessed using visual inspection of plots as well as influence statistics and residuals from generalized additive models. Observations were flagged for review based on leverage and Cook's distance to identify unusual patterns among the variables. The verified and validated data were used for all analyses. Missing data were not imputed for analysis in the current study. Less than 2% of the data were missing with all missingness reported. For air-conduction pure-tone audiometry, if the audiologist indicated there was “no response” at a given frequency (i.e., a measurable threshold could not be obtained due to limits of the audiometer), the threshold was set to 110 dB HL for inclusion in the descriptive statistics reported. There were 156 participants with one or more “no response(s)” and a total of 324 thresholds set to 110 dB HL in the final data set. Using the pure-tone audiometric results, the “better ear” was determined by selecting the ear with lowest audiometric thresholds; however, if the ears were identical, then the right ear was defined as the better ear.

All statistical analyses were completed using R Version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), using the agicolae (1.3–5), boot (1.3–28.1), GLMMadaptive (0.8–8), multcomp (1.4–23), splines (4.2.3), and VGAM (1.1–8) packages. Descriptive statistics were used to present the audiologic characteristics and are provided as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables or medians (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables. To visualize QuickSIN results, data were fit to generalized linear mixed models to evaluate subject-specific associations between presentation level and speech-in-noise performance, accounting for the repeated measures (i.e., the two test lists administered) within individuals using subject-specific intercepts and slopes (i.e., random effects). Population-average associations were obtained by marginalizing (i.e., integrating) over the subject-specific effects, allowing visualization of the data through a psychometric function. Spearman rho correlational analyses were conducted to examine the bivariate relationships between four-frequency PTA, QuickSIN performance, word recognition in quiet, and self-reported handicap (i.e., HHIE-S). CIs for these correlations were obtained using 10,000 nonparametric bootstrap replicates. Differences between study sites and recruitment methods (de novo vs. ARIC) for objectively measured and subjectively measured baseline data were evaluated using a Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables (Kruskal & Wallis, 1952). Associations with categorical outcomes were assessed using proportional odds and multinomial logistic regression models. The proportional odds assumption was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. When the proportional odds assumption was violated, the multinomial model was used instead. Multiple comparisons were addressed using Holm's correction (Holm, 1979).

Results and Preliminary Discussion

Recruitment, Enrollment, Participant Demographics, and Hearing History Characteristics

Recruitment and enrollment occurred between 2018 and 2019. Additional information about recruitment results is published elsewhere (see Reed et al., in press). Of the 977 participants enrolled, 24.4% were recruited through the ARIC study, while 75.6% were recruited de novo from the surrounding communities of the four university-affiliated clinical study sites. Recruitment allocation across the study sites included 262 (26.8%) from Washington County, MD; 243 (24.9%) from Jackson, MS; 236 (24.2%) from Forsyth County, NC; and 236 (24.2%) from Minneapolis, MN.

Supplemental Material S1 provides demographic results by study site and recruitment route. Participants were community-dwelling adults aged 70–84 years (Mdn = 76.8 years, IQR: 6) and 53.5% women. Most participants were White (87.6%; 11.5% Black; 0.9% of another race). The median number of people living in their household was two (IQR: 1) with 62% reporting being currently married. Approximately half of participants (53.4%) had a bachelor's degree or higher, 42.8% had a high school diploma or had completed some college, and 3.8% did not complete high school.

Supplemental Material S1 also provides additional information about hearing history variables including self-reported tinnitus perception, noise exposure, and otologic medical history. Approximately half of the participants (52%) reported no history of tinnitus in either ear, with 37% indicating bilateral tinnitus. Occupational noise exposure was reported by 27% of the participants, and 11% reported other noise exposure. Nearly all participants denied any medical otologic history, with 97% indicating no ear surgery and 99% indicating neither a diagnosis of sudden idiopathic nor Meniere's disease related. The distributions of the hearing history characteristics reported are consistent with our goal of recruiting adults with primarily age-related SNHL. Visual inspection of the data in Supplemental Material S2 indicate that these hearing history characteristics appear comparable across study sites and recruitment routes.

Outer and Middle Ear Function

Shown in Supplemental Material S2 are the data for the results from otoscopy and tympanometry examinations. Of the 977 participants, 95% of the monaural otoscopic examinations were within normal limits. The ears indicated as abnormal otoscopy were noted as either required cerumen management (75 ears) or as abnormal (28 ears) for other reasons (e.g., foreign object in ear, blood visualized). As summarized in Supplemental Material S3, there were no difference in otoscopy by recruitment route, but differences across sites (right ear p < 0.001; left ear p = 0.005). Despite a significant difference overall in otoscopy across sites, the only pairwise difference that reached statistical significance was between MD and NC sites for both the right and left ears, but the largest difference in the number of abnormal otoscopic exams differed by only eight ears.

Most participants had normal middle ear function, with 85% and 84% of the participants having normal tympanograms (Type A) for the left (n = 830) and right (n = 824) ears, as classified for data entry by the site audiologist, respectively. There were missing data due to inability to maintain a hermetic seal to perform the measurement in 18 left ears and 13 right ears. As summarized in Supplemental Material S3, there were no differences in tympanometry by recruitment route, but differences across sites, right ear, χ2(3) = 18.97, p < .001; left ear, χ2(3) = 26.917, p < .001. There were pairwise differences in the proportions of participants with abnormal tympanometry as a function of study site. There were significant pairwise differences with NC being different from MS for both the right and left ears and different from MD for the right ear only. Across both right and left ears, the greatest proportion of abnormal results was found for the MS site (20.6% and 21.8%, respectively), while relatively few participants at the NC site had abnormal tympanograms (7.6% and 7.2% for the right and left ears, respectively). While these site differences were observed, overall, there was a small proportion of participants who exhibited abnormal otoscopic or tympanometric results, medical examination confirmed that no participants at any sites had outer or middle ear disorders or dysfunctions that were a contraindication for hearing aids.

Pure-Tone Audiometry Results

To determine the type of hearing loss in each ear, air-conduction and bone-conduction thresholds, with appropriate masking, were evaluated. As shown in Supplemental Material S2, hearing losses were classified as sensorineural (SNHL), conductive hearing loss (CHL), mixed hearing loss (MHL), or unable to determine (UD) based on pure-tone audiometry alone. For each frequency tested by air- and bone-conduction, an air–bone gap of 15 dB or greater resulted in a classification of a frequency-specific conductive component. There were 1,378 ears with no conductive component, and these ears were classified as SNHL. For the remaining ears, a present air–bone gap (576 ears or 288 participants), the type of hearing loss was vetted through an adjudication process for which two independent audiologists reviewed the audiogram to determine the overall type of hearing loss. Of 288 patients reviewed, 22 required a third reviewer and adjudication. The final classification of ears included 16 MHLs, five UD, zero CHLs, with the remaining typed as SNHL (1,933 ears). Therefore, 98.1% of participants had bilateral SNHL, 0.2% had bilateral MHL, and 1.7% had an SNHL ear and either an MHL or UD loss in the other ear; thus, overall, most participants had bilateral SNHL. Visual inspection of the hearing loss types did not differ across sites nor recruitment route. Along with most losses being sensorineural, most participants had symmetrical hearing (83.1%) as defined by no greater than a 10-dB difference in thresholds at three consecutive frequencies or no greater than a 20-dB difference at two consecutive octave frequencies between ears. Right and left ear–specific details of four-frequency and three-frequency PTAs are provided in Supplemental Material S2, and the ear-specific audiogram is displayed in Supplemental Material S4.

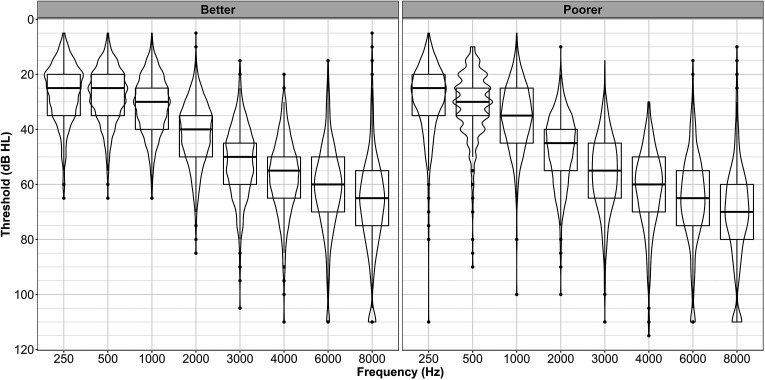

Better ear and poorer ear air-conduction threshold results are illustrated in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the pure-tone thresholds in violin plots, which depict the distributions of data using density curves, where the width of the curve corresponds with the approximate frequency of data points in each region. Our density curves are overlaid on box plots that depict numerical summaries of the data, with a central line marking the median value, the box denoting the 75th and 25th percentiles, lines extending showing the upper and lower fences of the data, and all observations outside the upper and lower fences are plotted individually. The median audiogram in Figure 1 shows a pattern of hearing loss, which is consistent with gradually sloping, symmetrical SNHL.

Figure 1.

Air-conduction pure-tone threshold violin plot for the better and poorer ear. The violin plot depicts the distributions of data using density curves with the width of the curve corresponding with the approximate frequency of data points in each region. Our density curves are overlaid on box plots that depict numerical summaries of the data, with a central line marking the median value, the box denoting the 75th and 25th percentiles, the lines extending showing the upper and lower fences of the data, and all observations outside the upper and lower fences are plotted individually.

Table 1.

Hearing characteristics of the 977 participants stratified by study site and recruitment source.

| Variable | Overall (n = 977) |

Study site |

Recruitment route |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 236) |

MS (n = 243) |

MN (n = 236) |

MD (n = 262) |

ARIC (n = 238) |

de novo (n = 739) |

||

| PTA (dB HL) | |||||||

| Better ear | 39 [33–43] | 38 [33–43] | 40 [35–45] | 38 [34–43] | 39 [34–44] | 38 [33–43] | 39 [34–44] |

| Poorer ear | 42 [38–48] | 42 [38–46] | 44 [39–51] | 41 [38–46] | 42 [38–50] | 42 [38–46] | 43 [38–49] |

| WHO criteriab | |||||||

| Mild | 284 (29) | 70 (30) | 58 (24) | 73 (31) | 83 (32) | 71 (30) | 213 (29) |

| Moderate | 600 (61) | 150 (64) | 152 (63) | 145 (61) | 153 (58) | 144 (61) | 456 (62) |

| Moderately severe | 91 (9) | 16 (7) | 33 (14) | 18 (8) | 24 (9) | 22 (9) | 69 (9) |

| Severe | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Word recognition in quietc (%) | |||||||

| Better ear | 90 [90–100] | 90 [90–96] | 90 [90–100] | 90 [90–100] | 90 [86–96] | 90 [88–99] | 90 [90–100] |

| Poorer ear | 90 [88–96] | 90 [88–96] | 90 [90–100] | 90 [90–100] | 90 [84–96] | 90 [86–96] | 90 [90–100] |

| Speech-in-noise performanced | |||||||

| Correctly recognized Words | 20 [16–22] | 20 [15–22] | 19 [15–21] | 19 [17–21] | 20 [17–22] | 19 [16–22] | 19 [16–22] |

| dB SNR loss | 6 [4–9] | 6 [4–11] | 7 [4–10] | 6 [4–8] | 5 [3–9] | 6 [4–10] | 6 [4–9] |

| HHIE-Se | |||||||

| No handicap | 304 (31) | 53 (22) | 76 (31) | 74 (31) | 101 (38) | 107 (45) | 197 (27) |

| Mild–moderate handicap | 487 (50) | 149 (63) | 103 (42) | 126 (53) | 109 (41) | 103 (43) | 384 (52) |

| Severe handicap | 179 (18) | 33 (14) | 61 (25) | 34 (14) | 51 (20) | 27 (11) | 152 (21) |

| Total score | 14 [8–22] | 16 [10–22] | 18 [8–26] | 12 [8–18] | 12 [6–22] | 10 [4–18] | 16 [8–24] |

| Self-reported trouble hearingf | |||||||

| Excellent | 12 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 9 (4) | 3 (0) |

| Good | 104 (11) | 12 (5) | 30 (12) | 25 (11) | 37 (14) | 39 (16) | 65 (9) |

| A little trouble | 412 (42) | 86 (36) | 80 (33) | 128 (54) | 118 (45) | 99 (42) | 313 (42) |

| Moderate trouble | 347 (36) | 109 (46) | 92 (38) | 70 (30) | 76 (29) | 74 (31) | 273 (37) |

| A lot of trouble | 99 (10) | 27 (11) | 38 (16) | 10 (4) | 24 (9) | 14 (6) | 85 (12) |

| Deaf | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

Note. Displayeda are the audiometry results, word recognition in quiet, speech perception in noise, and self-reported disability. NC = Forsyth, North Carolina; MS = Jackson, Mississippi; MN = Minneapolis, Minnesota; MD = Hagerstown, Maryland; ARIC = Participants recruited from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Epidemiologic study; de novo = participant recruited from the community; PTA = four-frequency pure-tone average measured at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz; WHO = World Health Organization; HHIE-S = Hearing Handicap Inventory–Elderly Screening version (Ventry & Weinstein, 1983); Sound Field Speech in Noise Performance was measured using the QuickSIN; QuickSIN = Quick Speech in Noise Test; dB SNR = decibel signal-to-noise ratio.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range, 25%–75%) or count (%) for a given column, unless otherwise noted in the table footnotes.

WHO grading criteria is determined by the pure-tone average (PTA) at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz for the better ear. Grading scale: No impairment = PTA < 19 dB HL; Mild = 20–34.9 dB HL; Moderate = 35–49.9 dB HL; Moderately severe = 50–64.9; Severe = 65–79 dB HL; Profound > 79 (World Health Organization, 2021).

Word recognition in quiet was measured using the Northwest University Ordered-by-Difficulty word lists (Hurley & Sells, 2003) presented monaurally for each ear under insert phones using the following presentation levels with sensation level (SL) referenced to the ear-specific 2000-Hz threshold: 2000-Hz threshold < 50 dB HL: 25 dB SL; 2000-Hz threshold 50–55 dB HL: 20 dB SL; 2000-Hz threshold 60–65 dB HL: 15 dB SL; 2000-Hz threshold 70–75 dB HL: 10 dB SL. Data are missing from one participant from the MN study site de novo group.

Speech-in-noise performance was measured using QuickSIN (Killion, 2004) Lists 1 and 2 presented binaurally in a sound field with speech presented at a fixed level of 70 dB SPL at 0° azimuth and multitalker babble ascending in 5-dB steps presented from 45 to 70 dB SPL at 180° azimuth. This paradigm created signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) ranging from +25 to 0, with five target words to be recognized at each SNR (60 total target words with both lists). The data are shown as number of correctly recognized words and as the derived dB SNR loss, which is the normalized threshold for which participants correctly identified 50% of the target words. Data are missing from five participants from the MS study site de novo group.

Data are missing from seven participants: one from the NC study site, two from the MN study site, three from the MS study site, and one from the MD study site. Six were from the de novo group, and one was from the ARIC group.

Self-reported trouble hearing was measured using a single item question with four possible responses. Data are missing from one participant from the NC study site ARIC group and one from the MD study site ARIC group.

Table 1 shows that the median four-frequency PTA for the better ear was 39 dB HL (IQR: 33–43), and the median for the poorer ear was 42 dB HL (IQR: 38–48). As summarized in Supplemental Material S3, there were some differences across sites. Despite a significant difference overall, in four-frequency PTA across sites, overall, χ2(3) = 8.109, p = .044, no pairwise differences reached statistical significance, with the largest difference in medians between sites being 2 dB HL. No difference in PTA was observed by recruitment route, χ2(1) = 0.461, p = .497, with the difference in medians between recruitment routes being 1 dB HL.

We also examined the better-ear four-frequency PTAs with respect to the World Health Organization (WHO) categorizations (WHO, 2021), for which a better-ear four-frequency PTA ≤ 19 dB HL corresponds to “normal”; 20–34.9 dB HL to “mild”; 35–49 dB HL to “moderate”; 50–64.9 dB HL to “moderately severe”; 65–79 dB HL to “severe”; and 80+ dB HL to “profound” hearing impairment. Based on this WHO grading criteria, 61% of our total number of participants had moderate hearing loss (PTA between 35 and 49.9 dB HL) and 29% had a mild loss (PTA between 20 and 34.9 dB HL), with very little variation in proportions across the two WHO categories as a function of study site or recruitment route. Although participants presented with a mild-to-moderate hearing loss, there was a large spread of the thresholds across the test frequencies as displayed in Figure 1.

Speech Audiometry Performance

Table 1 also shows median recognition performance in quiet for the better and poorer ears as determined by four-frequency PTA. Word recognition performance greater than 60% in at least one ear was part of the inclusion criteria; thus, the range of scores was restricted to 60%–100% for the higher performing ear. The median word recognition in quiet performance was 90% in both the better and poorer ears (IQRs of 90–100 and 88–96, respectively), with comparable findings shown for both ears as a function of recruitment route and a statistically significant difference was not observed (see Supplemental Material S3). Somewhat surprisingly, yet with a small effect size implicating the significant p value is likely due to our large sample size, word recognition in quiet in the better ear was statistically significantly different across sites, χ2(3) = 16.411, p < .001. However, the largest pairwise significant difference for word recognition in quiet (better ear) between the participants from the Jackson, MS, and Washington, MD, sites was only 2.7 percentage points, and, thus, would not be considered clinically meaningful (Thornton & Raffin, 1978). Overall, word recognition in quiet results are consistent with pure-tone audiometric results with respect to type, degree, and configuration of hearing loss.

In contrast to word recognition in quiet, participants' speech recognition in noise performance as measured binaurally in sound field showed a larger spread of performance abilities. The median number of words correctly recognized was 20 out of 60 (IQR: 16–22), indicating that across the various SNRs, participants recognized about 33% of the target words (see Table 1). Also shown in Table 1 are the mean normalized threshold calculations based off the Spearman–Kärber equation (dB SNR loss; Killion et al., 2004), with a median of 6-dB SNR loss (IQR: 4–9), indicating that most participants needed between 4 and 9 dB SNR to correctly recognize 50% of the target words.

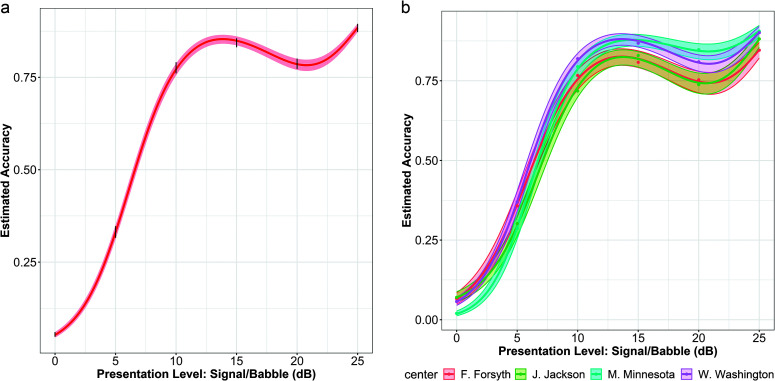

Figure 2 displays psychometric functions plotting speech recognition performance as a function of SNR from 25 to 0 dB. The left-side panel shows data from all participants while the right-side panel shows data stratified by study site. The median number of words correct varied by only one across study sites and recruitment routes. With no difference in median SNR values across recruitment routes, it is not surprising that there were no statistically significant differences (see Supplemental Material S3). As with word recognition in quiet, there was a statistically significant relation to study site, χ2(1) = 12.554, p = .006, and, again, the largest pairwise significant difference in SNR loss was between the participants from the Jackson, MS, and Washington, MD, sites. The magnitude of the difference was again relatively small at only 1.4 dB and unclear if clinically meaningful (Killion et al., 2004; McShefferty et al., 2015). The critical difference while using two QuickSIN lists is ± 2.7 dB SNR (95% CI; Killion et al., 2004), but it is appreciated that small changes in SNR can be perceived as large differences by individual listeners (McShefferty et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Speech-in-noise psychometric function performance. (a) Left panel shows all participants, while the (b) right panel shows functions per study site.

Self-Reported Hearing Handicap

Table 1 displays the results for the single-item self-reported hearing difficulty question and total HHIE-S scores. Examining of the data for the single-item self-report question, most participants reported either a little trouble (42%) or moderate trouble (36%) on the 6-point Likert scale, while only 12% reported excellent/good hearing and 10% reported a lot of trouble/deaf. Given these data, perhaps the results of the HHIE-S are not surprising, in that scores for 31% of the participants resulted in a classification of no handicap, while 50% had a mild–moderate handicap, and 18% were categorized as having a severe handicap. Furthermore, the median HHIE scores increased systematically as greater degrees of difficulty hearing were reported on the single question item (Supplemental Material S5).

The median HHIE-S score was 14 (IQR: 8–22), indicating that the average participant was classified as having a mild–moderate handicap. The median total score across sites ranged from 12 to 18, and the recruitment route medians differed by 6 points. Since self-reported hearing across sites, χ2(9) = 24.843, p < .001, and recruitment route, χ2(3) = 24.843, p < .001, reached statistical significance, logistic regression was used to assess differences by site and recruitment method. To further examine the data, comparisons of frequencies were done using contrasts of the coefficients, which revealed a significant difference between the Jackson, MS, site, which had the highest proportion of participants reporting a lot of trouble/deaf (16%) and the Minneapolis, MN, site in which only 4% of the participants reported this level of difficulty. Similarly, the Kruskal–Wallis analysis revealed that study site was significantly associated with HHIE-S scores, χ2(3) = 14.844, p = .002. Several pairwise comparisons were found to be statistically different for the HHIE-S scores, with the greatest hearing handicap observed for the Jackson, MS, participants and the least for the Minneapolis, MN, participants, consistent with the results for the single-item question about hearing difficulty.

Finally, in contrast to the objective audiological results presented above for recruitment route comparisons, the results of statistical analyses were significantly associated with both the single-item question of hearing difficulty, χ2(3) = 24.843, p < .001, and the HHIE-S score, χ2(1 = 37.881, p < .001. A larger proportion of the de novo participants indicated greater hearing difficulty and was categorized as having greater hearing handicap than the ARIC recruited participants. For example, only 27% of the de novo participants were classified as having no hearing handicap while 45% of ARIC participants' HHIE-S scores were classified as having no hearing handicap. Similarly, a greater proportion of de novo participants reported having a lot of trouble/deaf (11.5%) than did those recruited from ARIC (5.9%). In contrast, only 9% recruited de novo reported good/excellent hearing as compared to 20% of those recruited via ARIC.

Relationships Among Audiological Variables

Relationships between the audiological variables (i.e., PTA-better ear, PTA-poorer ear, word recognition-better ear, word recognition-poorer ear, HHIE-S, and SNR loss) were examined using Spearman rho analyses. Figure 3 displays scatter plots of the data and the results of the correlations. Not surprisingly, given our relatively large sample size, all relationships reached statistical significance (p < .001). Thus, we focus on the strength of the relationships, with reference to Cohen's effect size descriptors (Cohen, 2013), where r ≥ .50 is considered large, ≥ .20 is medium, and ≥ .10 is a small effect, and with consideration of the CIs for each statistic and the direction of the relationships (also displayed in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix showing relationship among the audiologic variables. The correlations are Spearman's rho, a rank-based correlation, with statistical significance indicated with asterisks (*) and 95% confidence intervals shown in brackets. Also shown are the scatter plots comparing audiologic data. PTA: B = pure-tone average of the better ear; QS: SNR L = Quick Speech-in-Noise Test signal-to-noise ratio loss; WR: P = word recognition of the poorer ear; WR: B = word recognition of the better ear; PTA: P = PTA of the poorer ear.

Given that most of the hearing losses, as measured via pure-tone audiometry, were noted to be symmetrical, it is not surprising that the strongest relationship between variables was between the PTAs for the better and poorer ears (r = .83, 95% CI [.79, .86]). The only other large effect size with PTA-better ear was with SNR loss (r = .56, 95% CI [.51, .60]) with, as expected, the greater the hearing loss (i.e., the higher PTA), the poorer speech understanding in noise (i.e., the greater SNR loss). Effect sizes are considered medium for the relationships between all other variables and PTA-better ear with 95% CIs supporting a conclusion of a medium effect, with the direction of all relationships as expected. The correlation between poorer-ear PTA and SNR loss was medium to large (r = .51, 95% CI [.46, .56]). The direction of the relationship however is as expected with those with greater PTA losses in the poorer ear having poorer speech recognition in noise performance. The correlation between poorer-ear PTA and word recognition in the poorer-ear was medium to large (r = −.45, 95% CI [−.50, −.39]). Point estimates and CIs for the relationships between PTA-poorer ear, word recognition-better ear, and HHIE-S scores revealed medium effect sizes.

The relationship between word recognition-better and poorer ear was also found to have a medium effect size (r = .34, 95% CI [.28, .39]). Similarly, the relationships between word recognition-better ear and SNR-Loss (r = −.33, 95% CI [−.38, −.26]) and word recognition-poorer ear and SNR-loss (r = −.33, 95% CI [−.39, −.27]) reflect medium effects with poorer monaural speech recognition in quiet reflective of poorer binaural speech recognition in noise. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprising given clinical experience, the weakest relationships were found between word recognition in quiet for better and poorer ears and self-report of hearing handicap with HHIE-S (r = −.12 and r = −19, respectively). In fact, the 95% CI [−0.18, −.05] for word recognition-better ear and HHIE-S suggest that the true effect size may be negligible. While the point estimate for the relationship between HHIE-S and SNR-loss was classified also as a medium effect, the CIs suggest a stronger association (r = .25, 95% CI [.19, .31]) than the relationships between the self-report measure and objective speech recognition performance in quiet.

Discussion

A growing amount of evidence describes the association between hearing and cognition (Dawes et al., 2015; Golub et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021; Lin, 2011; Livingston et al., 2017; 2020; Merten et al., 2020; West et al., 2022). Some of this evidence has included subjective hearing measurements and/or objective hearing measurements, yet very few have reported on thorough comprehensive hearing evaluations in conjunction with measures of cognition. Although we report here a study population that was restricted by our selected inclusion exclusion criteria, we provide extensive detail on how our data were collected as such detail is often lacking in studies examining the relationship between hearing loss and cognition (Loughrey, 2022; Marinelli et al., 2022).

Baseline data from large-scale clinical trials such as the ACHIEVE study are crucial for evaluating the validity and outcomes of a trial. Findings from systematic reviews of studies examining the relationship between hearing intervention and cognition call for increased rigor in the collection and reporting of hearing-related data. For example, Loughrey et al. (2018) found only 36 studies in which hearing loss was objectively assessed, and these studies used varying definitions of the objectively measured hearing loss such as a single-frequency threshold, monaural or binaural calculations of loss, and reports of thresholds for either the better or poorer ear. Sanders et al. (2021) identified 17 longitudinal studies, including 3,526 participants, which spanned over 30 years of research in which both audiometrically defined hearing loss and cognition were measured. The degree of hearing losses reported in included studies was similar to those in the ACHIEVE study (mild-to-moderate SNHL), but there was a lack of rigorous reporting regarding how hearing measurements were completed and how the audiological data were presented. Finally, the authors concluded that the effect of hearing intervention on cognition was equivocal, with the need for well-conducted, rigorous clinical trials, such as the ACHIEVE study, to fully understand these relationships. A more recent systematic review by Yeo et al. (2023) reported meta-analytic results from 31 observational studies indicating a decreased risk of cognitive decline from the use of hearing aids and cochlear implants. However, the detailed objective and subjective audiological data were not included in all reviewed studies.

The work presented here provides comprehensive information about the baseline hearing characteristics of the ACHIEVE study participants and the rigorous methods used to collect these data. Our findings were consistent with what is known clinically and in the literature. The ACHIEVE participants had mild-to-moderate hearing loss, aligning with the WHO estimation of debilitating hearing loss among older adults (WHO, 2021). The audiological profiles of the ACHIEVE participants are similar to large population-based reports (Humes, 2023; Reed et al., 2023). The degree of trouble listening in background noise, measured with the QuickSIN test, was consistent with similar patient populations, including community-dwelling adults and Veterans (McArdle & Wilson, 2006; Ou & Wetmore, 2020; Ross et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2007). It was interesting to see statistically significant difference in speech-noise performance across sites, which may be clinically meaningful and warrant future analyses including multivariable modeling to determine the influence of nonauditory variables (e.g., social determinants of health). Most participants had a little to moderate trouble hearing and had HHIE-S scores indicating more than a mild–moderate handicap.

Associations between audiologic characteristics and self-reported hearing were consistent in direction and magnitude with expectations and with other reports including participants with similar degrees of hearing loss evaluated with similar measures (Cassarly et al., 2019; Humes, 2023). In future analyses, we plan to evaluate if there are any site and recruitment route differences in the correlations between objective measures and self-reported measures. This may be informative and help disentangle the potential site and recruitment differences and inform future study outcome analyses. As of now, our results highlight the benefit of including both measured hearing performance (i.e., pure-tone and speech audiometry) and self-report assessments for the characterization of hearing loss in older adults, which is also consistent with other reports (Humes, 2019), as both objective and subjective measurements are needed to fully understand the influence of hearing loss (Humes, 2023). In summary, objective and subjective baseline audiological characteristics of ACHIEVE study participants align clinically with what would be expected in older adults meeting study inclusion criteria and with the literature.

Our study had limitations in that subjective hearing results from the ARIC participant group may not generalize to all adults seeking hearing health care. ARIC participants have a long history of volunteering for research and may have agreed to participate even though they did not perceive a hearing loss, while it is possible that de novo participants volunteered for a study with a hearing intervention arm because of self-perceived hearing problems. In addition, because of our long-standing history with ARIC participants, objective hearing loss status was known, so we specifically sought them out to participate in this study. This is unlike the de novo participants that presented to the study only after seeing recruitment advertisements. The observation of differences in self-report measures of hearing difficulty and hearing handicap based on recruitment route were not anticipated beforehand, but also not surprising and similar to other reports that evaluated self-reported hearing ability between those seeking and not seeking hearing health care (Humes & Dubno, 2021). Future studies may benefit from inclusion of qualitative data to elucidate motivations for participating in studies such as the ACHIEVE study. Within the ACHIEVE data set, it will be of interest to determine if there are other nonaudiological variables that may influence analyses and interpretations.

We consider that the most likely reason there are site differences observed in our analysis is due to having large sample sizes, as the effect sizes were small and most of the post hoc analyses did not reveal any clinically meaningful differences, at least for the objective data. It is well known that large sample sizes can influence statistical findings (Khalilzadeh & Tasci, 2017), and it is important to note that a p value does not provide any information on the magnitude of the effect and the clinical meaningfulness. Thus, while we reviewed the statistical analyses, we commented on the effect sizes and clinically meaningful differences. Although we suggest that most differences are likely explained by larger sample sizes, we also acknowledge differences could have been due to procedures being conducted differently across sites, as ensuring precision in methods across many sites is very challenging. We consider this highly unlikely considering the extensive quality assurance and quality control protocol designed for the ACHIEVE study. As described in detail elsewhere (Arnold et al., 2022), the comprehensive audiological evaluation was completed by licensed, nationally certified audiologists who completed training in ACHIEVE hearing-related protocol administration and audiological procedures were monitored through direct observation and validating data entry. Alternatively, it is also possible that the differences observed are true differences and may be related to variables not considered in the current analyses. We acknowledge that there are known geographic, socio-economic, sex-related differences, and many other social determinants of health that can influence audiometric profiles. It will be important to consider these variables in subsequent analyses.

Even with potential limitations in mind, knowing the baseline characteristics of the ACHIEVE study participants, the results reported here allows clinicians to assess how closely the participants match to the patients seen in their own practice, and therefore, they will be important for generalizability or external validity of the trial. The audiologic characteristics of the ACHIEVE study participants are appropriate for the hearing intervention designed for the trial (Sanchez et al., 2020). With the majority of the participants presenting with moderate hearing loss, word recognition in quiet performance greater than 60% in at least one ear, mild/moderate difficulty hearing speech in the presence of background noise, and moderate self-reported hearing handicap, the technical aspects of the treatment such as ear-level worn hearing aids with connective applications to additional hearing-assistive devices are known to sufficiently meet the needs of these audiometric characteristics. While it is not within the scope of this article to directly evaluate the appropriateness of the hearing intervention for a population with these hearing characteristics, future analyses will address these questions once the outcomes data are unblinded and available. Primary outcome results were recently released (Lin et al., 2023), with several additional outcomes and analyses expected to follow. It is noteworthy to share that we have extended the original study to conduct long-term follow-up. The ACHIEVE Brain Health Follow-Up Study (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT05532657) will continue following the ACHIEVE cohort for an additional 3 years (i.e., 6 years total) after randomization to determine the long-term effects of hearing intervention on brain health.

The National Institutes of Health requires sharing of scientific data to accelerate biomedical research discovery, enhance research rigor and reproducibility, and promote data reuse for future research studies. Our data set will be publicly available for the scientific community, and the details we provide here may be useful as a template for the level of detail that should be reported in future studies evaluating the effect of hearing intervention on cognition. These data will also be important for reference when the ACHIEVE main trial results are reported to contextualize the trial's major findings.

Conclusions

We present a thorough overview of the baseline audiological characteristics from enrolled ACHIEVE study participants. These participants were followed for 3 years with final study visits occurring in late 2022. The baseline audiometric and hearing-related self-report characteristics of the ACHIEVE participants will help to inform the planned analyses and serves as one of several descriptive, genre-specific baseline papers, intended to offer deep complementary information for interpreting the outcome results. We provide a thorough review of the audiologic results from a novel randomized trial that will be used to inform the findings on the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline.

Author Contributions

Victoria A. Sanchez: Conceptualization (Equal), Data curation (Equal), Formal analysis (Supporting), Funding acquisition (Supporting), Methodology (Supporting), Project administration (Lead), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Equal), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Supporting), Writing – original draft (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Lead). Michelle L. Arnold: Conceptualization (Equal), Data curation (Supporting), Formal analysis (Supporting), Methodology (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Equal), Validation (Equal), Writing – original draft (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Joshua F. Betz: Data curation (Equal), Formal analysis (Lead), Methodology (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Software (Lead), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Lead), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Nicholas S. Reed: Conceptualization (Supporting), Methodology (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Sarah Faucette: Data curation (Supporting), Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Elizabeth Anderson: Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Sheila Burgard: Writing – review & editing (Supporting), Data curation (Supporting). Josef Coresh: Funding acquisition (Equal), Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Jennifer A. Deal: Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Ann Clock Eddins: Conceptualization (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Adele M. Goman: Data curation (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Nancy W. Glynn: Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Lisa Gravens-Mueller: Writing – review & editing (Supporting), Data curation (Supporting). Jaime Hampton: Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Kathleen M. Hayden: Funding acquisition (Supporting), Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Alison R. Huang: Data curation (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Software (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Kaila Liou: Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Christine M. Mitchell: Data curation (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Thomas H. Mosley, Jr.: Funding acquisition (Supporting), Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Haley N. Neil: Data curation (Equal), Methodology (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Visualization (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). James S. Pankow: Funding acquisition (Supporting), Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). James R. Pike: Formal analysis (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Jennifer A. Schrack: Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Laura Sherry: Project administration (Supporting), Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Katherine H. Teece: Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Kerry Witherell: Investigation (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Frank R. Lin: Conceptualization (Supporting), Funding acquisition (Equal), Methodology (Supporting), Resources (Equal), Supervision (Supporting), Writing – review & editing (Supporting). Theresa H. Chisolm: Conceptualization (Equal), Formal analysis (Supporting), Funding acquisition (Supporting), Methodology (Supporting), Project administration (Supporting), Resources (Equal), Supervision (Equal), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Supporting), Writing – original draft (Equal), Writing – review & editing (Supporting).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the International Hearing Aid Conference (IHCON, 2022, Tahoe, CA), and the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO, 2023, Orlando, FL). The authors thank the staff and participants of the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) studies for their important contributions. Hearing aids, hearing assistive technologies, and related materials were provided at no cost to the researchers or the participants from Phonak, LLC; however, the sponsoring manufacturer did not participate in the design, data collection or analysis, nor the reporting within this article. The ACHIEVE Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Grant R01AG055426, with magnetic brain resonance examination funded by NIA R01AG060502 and with previous pilot study support NIAR34AG046548 and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation, in collaboration with the ARIC Study, supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Neurocognitive data in ARIC are collected by U01 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, and 2U01HL096917 from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NIA; and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders), and with previous brain magnetic resonance imaging examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI.

Funding Statement

Portions of this work were presented at the International Hearing Aid Conference (IHCON, 2022, Tahoe, CA), and the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO, 2023, Orlando, FL). The authors thank the staff and participants of the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) studies for their important contributions. Hearing aids, hearing assistive technologies, and related materials were provided at no cost to the researchers or the participants from Phonak, LLC; however, the sponsoring manufacturer did not participate in the design, data collection or analysis, nor the reporting within this article. The ACHIEVE Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Grant R01AG055426, with magnetic brain resonance examination funded by NIA R01AG060502 and with previous pilot study support NIAR34AG046548 and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation, in collaboration with the ARIC Study, supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Neurocognitive data in ARIC are collected by U01 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, and 2U01HL096917 from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NIA; and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders), and with previous brain magnetic resonance imaging examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI.>

References

- American National Standards Institute. (1999). Permissible ambient noise levels for audiometric test rooms (ANSI S3.1-1999).

- American National Standards Institute. (2018). Specification for audiometers (ANSI S3.6-2018).

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (1997). Guidelines for audiologic screening. http://asha.org/policy

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I., Smailagic, N., Roqué-Figuls, M., Ciapponi, A., Sanchez-Perez, E., Giannakou, A., Pedraza, O. L., Bonfill Cosp, X., & Cullum, S. (2021). Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(7), Article Cd010783. 10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M. L., Haley, W., Lin, F. R., Faucette, S., Sherry, L., Higuchi, K., Witherell, K., Anderson, E., Reed, N. S., Chisolm, T. H., & Sanchez, V. A. (2022). Development, assessment, and monitoring of audiologic treatment fidelity in the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Audiology, 61(9), 720–730. 10.1080/14992027.2021.1973126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atef, R. Z., Michalowsky, B., Raedke, A., Platen, M., Mohr, W., Mühlichen, F., Thyrian, J. R., & Hoffmann, W. (2023). Impact of hearing aids on progression of cognitive decline, depression, and quality of life among people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 92(2), 629–638. 10.3233/jad-220938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. (1989). The atherosclerosis risk in COMMUNIT (ARIC) study: Design and objectives. American Journal of Epidemiology, 129(4), 687–702. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B., & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12(1), 12–21. 10.1037/0882-7974.12.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart, R., & Jerger, J. F. (1959). Preferred method for clinical determination of pure-tone thresholds. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 24(4), 330–345. 10.1044/jshd.2404.330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cassarly, C., Matthews, L. J., Simpson, A. N., & Dubno, J. R. (2019). The revised hearing handicap inventory and screening tool based on psychometric reevaluation of the hearing handicap inventories for the elderly and adults. Ear and Hearing, 41(1), 95–105. 10.1097/aud.0000000000000746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203771587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, P., Emsley, R., Cruickshanks, K. J., Moore, D. R., Fortnum, H., Edmondson-Jones, M., McCormack, A., & Munro, K. J. (2015). Hearing loss and cognition: The role of hearing aids, social isolation, and depression. PLOS ONE, 10(3), Article e0119616. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal, J. A., Goman, A. M., Albert, M. S., Arnold, M. L., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Glynn, N. W., Gmelin, T., Hayden, K. M., Mosley, T., Pankow, J. S., Reed, N., Sanchez, V. A., Richey Sharrett, A., Thomas, S. D., Coresh, J., & Lin, F. R. (2018). Hearing treatment for reducing cognitive decline: Design and methods of the aging and cognitive health evaluation in elders randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 4(1), 499–507. 10.1016/j.trci.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham, M. W., Weitzman, R. E., & Golub, J. S. (2023). Hearing aids and cochlear implants in the prevention of cognitive decline and dementia—Breaking through the silence. JAMA Neurology, 80(2), 127–128. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, L. K., Walsh, M. C., Merten, N., Cruickshanks, K. J., & Schultz, A. (2022). Prevalence of self-reported hearing loss and associated risk factors: Findings from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(5), 2016–2028. 10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etymōtic Research. (2021). Quick Speech-in-Noise Test [soundfiles]. Elk Grove. [Google Scholar]

- Golub, J. S., Brickman, A. M., Ciarleglio, A. J., Schupf, N., & Luchsinger, J. A. (2020). Audiometric age-related hearing loss and cognition in the Hispanic community health study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 75(3), 552–560. 10.1093/gerona/glz119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, L. A., & Mackersie, C. L. (2009). A comparison of presentation levels to maximize word recognition scores. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20(6), 381–390. 10.3766/jaaa.20.6.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J. D. (1960). The principles and practice of bone conduction audiometry: A review of the present position. The Laryngoscope, 70(9), 1211–1228. 10.1288/00005537-196009000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson, W., & Westlake, H. (1944). Manual for program outline for rehabilitation of aural casualties both military and civilian. Transactions–American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. (2019). The World Health Organization's hearing-impairment grading system: An evaluation for unaided communication in age-related hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 58(1), 12–20. 10.1080/14992027.2018.1518598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. (2023). U.S. population data on hearing loss, trouble hearing, and hearing-device use in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–12, 2015–16, and 2017–20. Trends in Hearing, 27. 10.1177/23312165231160978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E., & Dubno, J. R. (2021). A comparison of the perceived hearing difficulties of community and clinical samples of older adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(9), 3653–3667. 10.1044/2021_jslhr-20-00728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, R. M., & Sells, J. P. (2003). An abbreviated word recognition protocol based on item difficulty. Ear and Hearing, 24(2), 111–118. 10.1097/01.AUD.0000058113.56906.0D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalilzadeh, J., & Tasci, A. D. A. (2017). Large sample size, significance level, and the effect size: Solutions to perils of using big data for academic research. Tourism Management, 62, 89–96. 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killion, M. C., Niquette, P. A., Gudmundsen, G. I., Revit, L. J., & Banerjee, S. (2004). Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116(4), 2395–2405. 10.1121/1.1784440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W. H., & Wallis, W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47(260), 583–621. 10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z., Li, A., Xu, Y., Qian, X., & Gao, X. (2021). Hearing loss and dementia: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, Article 695117. 10.3389/fnagi.2021.695117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. R. (2011). Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 66A(10), 1131–1136. 10.1093/gerona/glr115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. R., & Albert, M. (2014). Hearing loss and dementia—Who is listening? Aging & Mental Health, 18(6), 671–673. 10.1080/13607863.2014.915924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. R., Pike, J. R., Albert, M. S., Arnold, M., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Deal, J. A., Goman, A. M., Glynn, N. W., Gmelin, T., Gravens-Mueller, L., Hayden, K. M., Huang, A. R., Knopman, D., Mitchell, C. M., Mosley, T., Pankow, J. S., Reed, N. S., ACHIEVE Collaborative Research Group. (2023). Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 402(10404), 786–797. 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01406-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., … Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413–446. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Larson, E. B., Ritchie, K., Rockwood, K., Sampson, E. L., … Mukadam, N. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2673–2734. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey, D. G. (2022). Is age-related hearing loss a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia? The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 3(12), e805–e806. 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00252-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey, D. G., Kelly, M. E., Kelley, G. A., Brennan, S., & Lawlor, B. A. (2018). Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 144(2), 115–126. 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharani, A., Dawes, P., Nazroo, J., Tampubolon, G., & Pendleton, N. (2018). Longitudinal relationship between hearing aid use and cognitive function in older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(6), 1130–1136. 10.1111/jgs.15363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli, J. P., Lohse, C. M., Fussell, W. L., Petersen, R. C., Reed, N. S., Machulda, M. M., Vassilaki, M., & Carlson, M. L. (2022). Association between hearing loss and development of dementia using formal behavioural audiometric testing within the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA): A prospective population-based study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 3(12), e817–e824. 10.1016/s2666-7568(22)00241-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, N., Ingram, M., Bischoff, K., Burgen, E., Carvajal, S. C., & Bell, M. L. (2019). Self-reported hearing difficulty and its association with general, cognitive, and psychosocial health in the state of Arizona, 2015. BMC Public Health, 19(1), Article 875. 10.1186/s12889-019-7175-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]