Abstract

Background

Medical school clerkship grades are used to evaluate orthopedic surgery residency applicants, however, high interinstitutional variability in grade distribution calls into question the utility of clerkship grades when evaluating applicants from different medical schools. This study aims to evaluate the variability in grade distribution among medical schools and look for trends in grade distribution over recent years.

Methods

Applications submitted to Rush University's orthopedic surgery residency program from 2015, 2019, and 2022 were collected from the Electronic Residency Application Service. Applications from the top 100 schools according to the 2023–2024 U.S. News and World Report Research Rankings were reviewed. The percentage of “honors” grades awarded by medical schools for the surgery and internal medicine clerkships were extracted from applicants' Medical Student Performance Evaluation letters.

Results

The median percentage of honors given in 2022 was 36.0 % (range 10.0–82.0) for the surgery clerkship and 33.0 % (range 6.7–80.0) for the internal medicine clerkship. Honors were given 6.6 % more in the surgery clerkship in 2022 compared to 2015. There was a negative correlation between a higher (worse) U.S. News and World Report research ranking and the percentage of honors awarded in 2022 for the surgery and internal medicine clerkships.

Conclusion

There is substantial interinstitutional variability in the rate that medical schools award an “honors” grade with evidence of grade inflation in the surgery clerkship. Residency programs using clerkship grades to compare applicants should do so cautiously provided the variability demonstrated in this study.

Keywords: Clerkship grades, Education, Evaluation, Medical student, Orthopedics

Highlights

-

•

There is high variability in the distribution of 3rd-year clerkship grades.

-

•

There is evidence of grade inflation in the surgery clerkship from 2015 to 2022.

-

•

Better-ranked medical schools tend to give out more “honors” grades.

Key message

There is substantial interinstitutional variability in the rate that medical schools award an “honors” grade with evidence of grade inflation in the surgery clerkship. Residency programs using clerkship grades to compare applicants should do so cautiously provided the variability demonstrated in this study.

Introduction

The process of selecting medical students for orthopedic surgery residency in the United States is highly competitive, with a large number of applicants vying for a limited number of positions. In 2023, over 1400 applicants applied for only 899 spots, owing to one of the most selective cycles to date [1]. For residency program directors, selecting appropriate candidates becomes exceedingly complex given the lack of standardization and objectivity of evaluation methods across medical schools. In previous years, the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1 exam was used as an unofficial screening tool, despite lacking definitive evidence of its ability to predict success in residency. However, as of the 2023 application cycle, the USMLE Step 1 exam numerical score is no longer reported, and program directors must rely more heavily on alternative metrics when evaluating applicants [2,3]. Letters of recommendation have been utilized as a valuable tool but are subjective and prone to bias. Third-year clerkship grades, reported on the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE), are consistently cited as a significant factor in the applicant assessment. While they seem to be a logical alternative for objective evaluation, they may be far more unreliable than they appear [2,4].

The MSPE is a summary letter of evaluation provided by an applicant's medical school dean, providing program directors with comparative data about students' performance in medical school courses [5]. It serves as an important tool to assess student performance and professionalism in the medical setting; however, studies have reported significant inter- and intraschool grading variability, particularly for clerkship grades [2]. Currently, each medical school independently devises a grading system for its students, placing the responsibility on application reviewers to interpret these systems [4]. Residency programs may have to compare a student in a class where only 5 % receive a grade of “honors” compared to a student from a school where 50 % receive a grade of “honors.” [6] This lack of standardization raises concerns about the accuracy and reliability of clerkship grades, thus calling into question their utility in applicant evaluation [2]. While previous studies have assessed third-year clerkship grades, they are limited to a single application cycle year [6,7].

This study aims to investigate the variability and trends in grades in the surgery and internal medicine clerkships across three recent years for medical students applying to orthopedic surgery residency. We hypothesize that there is wide variability in clerkship grades and that the percentage of students receiving a grade of “honors” is increasing.

Methods

Applications submitted to our institution's orthopedic residency from the years 2015, 2019, and 2022 were collected from the Electronic Residency Application Service. 2015 and 2019 were selected to assess trends in applications before the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2022 was selected to see if COVID-19 had an accelerating effect on grade distribution changes. Applications from the top 100 schools, based on the 2023–2024 U.S. News and World Report Research Rankings [8], were reviewed. Of these medical schools, three schools did not have a graduating class by 2015, and two did not have a graduating class by 2019 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Medical schools included in analysis.

Schools that did not provide comparative data, meaning that they did not provide information on grade distributions, were excluded from the analysis. 11/97 schools did not provide comparative data for clerkship grade distribution in 2015, 10/98 schools did not provide comparative data in 2019, and 17/100 schools did not provide comparative data in 2022. (Fig. 1). For schools that gave letter grades, “A+” and “A” were considered equivalent to honors. For schools that gave numerical grades out of 100, a score greater or equal to 90 was considered equivalent to honors. The percent “honors” grades awarded by each school for the surgery and internal medicine clerkship were extracted from figures and tables from applicants' Medical Student Performance Evaluation letters. Including both the surgery and internal medicine clerkships was performed increase generalizability and provide insights to various specialties involved in the residency selection process.

SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.1.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) was used for descriptive and inferential analysis. The mean percentage of honors grades for included schools was calculated, median and interquartile ranges were identified, and descriptive statistics were performed. The grade distributions were treated as continuous variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the data for normality. Paired 2-sample t-tests were used to assess differences in the percentage of honors given between individual schools across application cycle years. Pearson's correlation was calculated to assess for a relationship between research ranking and the percentage of “honors” awarded for 2022 applicant cycle data. Pearson's Chi-Squared test was used to assess for differences in the rate that comparative data was omitted for the top 25 ranked schools versus schools ranked 26–100 for 2022 data. A sub-analysis was performed to evaluate for a difference in the percent “honors” awarded for schools ranked 1–25, 26–75, and 76–100 for the 2022 application cycle. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, and post-hoc analysis was performed using the Tukey test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The median percentage of honors given in 2015 was 30.5 % (IQR 24.0–40.0, range 4.0–73.0) for surgery and 31.4 % (IQR 22.8–40.3, range 6.0–58.0) for medicine. The median percentage of honors given in 2019 was 32.0 % (IQR 24.0–45.0, range 6.0–66.0) for surgery and 35.0 % (IQR 28.0–44.0, range 9.0–70.0) for medicine. The median percentage of honors given in 2022 was 36.0 % (IQR 26.3–5 0.0, range 10.0–82.0) for surgery, and 33.0 (IQR 24.2–45.0, range 6.7–80.0) for medicine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percent “honors” distribution by clerkship and year.

| Application cycle year and clerkship | n | Mean | SD | Median | Interquartile range | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | ||||||

| Surgery | 86 | 31.9 | 13.1 | 30.5 | 16.1 | 69.0 (4.0–73.0) |

| Medicine | 86 | 32.5 | 11.4 | 31.4 | 17.5 | 52.0 (6.0–58.0) |

| 2019 | ||||||

| Surgery | 88 | 34.6 | 13.8 | 32.0 | 21.0 | 54.0 (6.0–60.0) |

| Medicine | 88 | 35.8 | 12.2 | 35.0 | 16.0 | 61.0 (9.0–70.0) |

| 2022 | ||||||

| Surgery | 83 | 38.6 | 16.6 | 36.0 | 23.7 | 72.0 (10.0–82.0) |

| Medicine | 83 | 35.3 | 15.0 | 33.0 | 20.8 | 73.3 (6.7–80.0) |

When comparing the difference in the percentage of honors in the surgery clerkship awarded in 2019 versus 2015 via paired samples t-test, honors were given 2.9 % more on average in 2019 (CI 0.2–5.7, P = 0.036) in surgery and 3.3 % more on average in 2019 (CI 0.7–5.9, P = 0.015) in the internal medicine clerkship. For 2022 versus 2019, honors were given 4.4 % more on average (CI 1.0–7.88, P = 0.013) in surgery and 0.7 % less (CI 3.6–2.2, P = 0.626) in the internal medicine clerkship. When comparing 2022 versus 2015, honors were given 6.6 % more on average in the surgery clerkship in 2022 (CI 3.0–10.2, P < 0.001) and 2.5 % more on average (CI −0.7–5.6, P = 0.123) in the internal medicine clerkship.

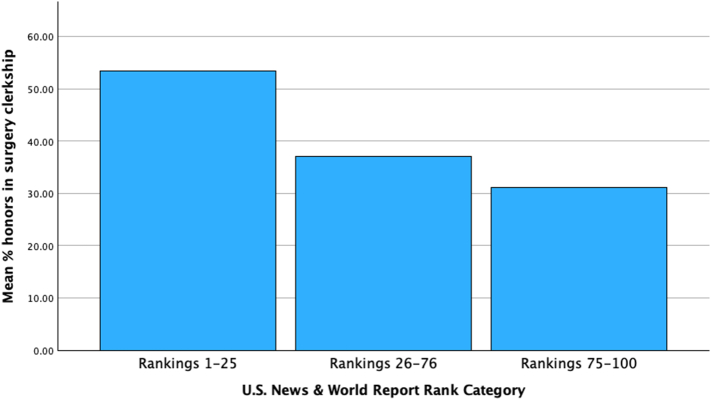

There was a negative correlation between a higher (worse) U.S. News and World Report research ranking and percentage of honors awarded in 2022 for the surgery clerkship (r = −0.401, P < 0.001) and the internal medicine clerkship (r = −0.366, P < 0.001). One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference in percent honors for the surgery clerkship for the 2022 application cycle for schools ranked in categories 1–25, 26–75, and 76–100 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Post hoc analysis showed a significant difference between the top 25 schools and both the middle 50 schools and schools ranked 76–100 (P < 0.001), but did not reveal a significant difference between schools ranked 26–75 and 76–100 (P = 0.270) Similarly, one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference in percent honors for the internal medicine clerkship in the 2022 application cycle for schools ranked in categories 1–25, 26–75, and 76–100 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Post hoc analysis showed a significant difference between the top 25 schools and both the middle 50 and 76–100 (P < 0.001), but did not reveal a significant difference between schools ranked 26–75 and 76–100 (p = 0.615). There was a significant difference in the proportion of schools that chose to omit comparative data in the top 25 schools (nine schools with no comparative data) versus schools ranked 26–100 (eight schools with no comparative data) (P = 0.003) for the 2022 application cycle.

Fig. 2.

% honors in surgery clerkship by U.S. News and World Report ranking.

Fig. 3.

% honors in internal medicine clerkship by U.S. News and World Report ranking.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are as follows: 1) There is significant interinstitutional variability in the rate at which schools award a grade of “honors” to their students. 2) There is evidence of grade inflation in the surgery clerkship from 2015 to 2022. 3) Schools with more favorable U.S. News & World and Report rankings are more likely to award their students a grade of “honors.”

The median percentage of honors given in 2022 was 36.0 (IQR 26.3–50.0, range 10.0–82.0) for surgery, and 33.0 (IQR 24.2–45.0, range 6.7–80.0) for medicine. This median and range are similar to Vokes et al. who, when analyzing data from orthopedic residency applicants in 2017, found a median percent “honors” awarded of 32.5 % (range 5–67) in the surgery clerkship and 32.0 % (range 7–80) in the internal medicine clerkship [6]. Earlier data from the 2005 application cycle demonstrated the percentage of honors awarded in the surgery clerkship ranged from 2 % to 75 % of students depending on the medical school [9]. This persistent variability in the rate of honors awarded across medical schools poses a significant challenge to applicant reviewers when considering clerkship grades in the resident selection process.

Metrics available for the applicant have changed in recent years, as many schools move to a “pass” or “fail” preclinical curriculum and are phasing out the Alpha-Omega Alpha (AOA) honor society [10]. In addition, the change in scoring of USMLE Step 1 to “pass” or “fail” in January of 2022 marks the loss of a metric historically ranked among the most important by orthopedic program directors [11]. With increasingly limited data to evaluate applicants, programs will be forced to rely more heavily on other metrics such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2, research experience, and third-year clerkship grades to evaluate applicants. However, due to the variable “honors” distribution in third-year clerkships among medical schools, whether a student receives a grade of “honors” or not should be interpreted cautiously. Consider a hypothetical scenario with two applicants, one from Medical School “A” and one from Medical School “B”. The applicant from Medical School “A” received a grade of “high-pass” in the surgery clerkship while the applicant from Medical School “B” received a grade of “honors.” When you investigate the grade distribution at these schools from the 2022 application cycle, Medical School “B” gave 79 % of their students a grade of “honors” in the surgery clerkship, while Medical School “A” only awarded 18 % of their students a grade of “honors” in the surgery clerkship. It may be of value for schools to develop a system to account for the percentage of honors awarded at a school in addition to the grade the individual applicant received. However, this is not possible with all medical schools, as there were 17 out of the top 100 schools in the 2022 application cycle that elected to not provide comparative data for students. Of note, schools that omit comparative data tend to be schools ranked more favorably in the U.S. News and World Report rankings. Of schools in the top 25 of these rankings, nine did not provide comparative data, while eight schools ranked from 26 to 100 did not provide comparative data. The lack of comparative data makes it even harder for programs to determine the relative magnitude of receiving (or not receiving) a grade of “honors” in each clerkship. Creating a reasonable solution to this problem is challenging, as grading policies differ widely among medical schools, and implementing a standardized grading system across all medical schools would be an arduous task. Most clerkships require students to pass the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject exam to pass each clerkship [12]. Encouraging medical schools to provide the score and percentile that each student achieved on these standardized exams would give an objective data point that may add more context to an individual student's performance in that clerkship.

In addition to interinstitutional variability, there was a trend of chronologically increasing “honors” awarded in surgery clerkships across the three years evaluated. There was a significant increase from 2015 to 2019 (2.9 %), as well as an even larger increase (4.4 %) from 2019 to 2022. Harris et al. found a median percentage of awarded honors of 25 % in the 2005 application cycle, which is markedly lower than what was found in the three years in this study [9]. This finding was also consistent with the Vokes et al. analysis of the 2017 application cycle [6]. Grade inflation has been previously described in third-year clerkships and has been noted to be a concern of clerkship directors [13]. The inflation of grades and the variability across institutions diminishes the reliability and utility of this metric to compare applicants.

In addition, it is interesting to compare grade distributions that occurred prior to and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 had a dramatic impact on medical education, including the replacement of in-person clerkships with virtual clerkships, as well as the shortening or cancellation of clerkships [14]. In this setting, it is difficult for students to be evaluated in a similar fashion to years prior. Those who were part of the 2022 application cohort in this study had their clerkships after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the 2015 and 2019 application cycle cohorts had finished their third-year clerkships [15]. This gives insight into how grade distributions may have changed in light of the pandemic. We found that in 2022, honors in surgery were given at the highest rate of all three years (mean, 38.6 %), and the increase from 2019 to 2022 (4.4 %) was greater than the increase from 2015 to 2019 (2.9 %). It is unclear if COVID-19 and its effect on medical education led to an increase in the rate of grade inflation, or if this is part of a larger trend of inflation across many years.

We also found a correlation between the U.S News & World Report Rankings and the percentage of “honors” awarded in both internal medicine (r = −0.366, P < 0.001) and surgery clerkships (r = −0.401, P < 0.001), indicating that a student at a top school is more likely to receive a grade of honors. When performing a sub-analysis comparing the top 25 ranked schools, the middle 50, and schools ranked 76–100, there was a statistically significant difference in the percent honors assigned by the top 25 schools when compared to the other two categories (P < 0.001).

There are limitations to this study. Only the top 100 medical schools from U.S. News and World Report Research Rankings were included and evaluated. It is possible that the distribution of grades for medical schools outside this range differs from that of the top 100 medical schools. In addition, there were several schools that did not provide comparative data for clerkship grades, ranging from 11 schools in 2015 to 17 schools in 2022. There were also a handful of schools that did not use the more typical “honors,” “high-pass,” and “pass” pass grading scheme. These schools were still included in the analysis by categorizing a grade of A+/A or ≥90 % as honors. This conversion yielded a percentage of honors similar to that of schools with the standard clerkship grading scheme, and these schools were included to reduce the chance of selection bias that would be caused by excluding them from the analysis.

Conclusions

There is high interinstitutional variability in the rate that medical schools award a grade of “honors” with evidence of grade inflation in the surgery clerkship. Schools with more favorable U.S. News & World Report rankings are more likely to award a student a grade of “honors” in surgery and internal medicine clerkships. Residency programs using clerkship grades to compare applicants from different schools should do so cautiously. As the selection of medical residents in the United States continues to evolve, there is an increasing need for standardized comparative performance reporting to ensure fairness and accuracy in applicant selection.

Funding sources

None.

Ethics approval

This research did not involve human subjects and thus did not require ethical approval from the institutional review board.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

John F. Hoy: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Samuel L. Shuman: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Shelby R. Smith: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Monica Kogan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Xavier C. Simcock: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Appendix A

Table A.1.

Percentage of students receiving an honors grade in the surgery and internal medicine clerkships from 2022 application cycle data.

| U.S. News and World Report ranking 2023–2024 | Medical school | Percentage of students receiving an honors grade in surgery clerkship | Percentage of students receiving an honors grade in internal medicine clerkship |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harvard University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 2 | Johns Hopkins University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 3 | University of Pennsylvania (Perelman) | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 4 | Columbia University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 5 | University of California – San Francisco | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 5 | Duke University | 52 | 36.4 |

| 5 | Stanford University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 5 | Washington University in St. Louis | 64 | 80 |

| 5 | Vanderbilt University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 10 | New York University (Grossman) | 56.3 | 52.1 |

| 10 | Yale University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 10 | Cornell University (Weill) | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 13 | University of Washington | 45 | 45 |

| 13 | Mayo Clinic School of Medicine | 65.3 | 55.2 |

| 13 | University of Pittsburg | 45 | 45 |

| 13 | Northwestern University (Feinberg) | 79 | 74 |

| 13 | University of Michigan – Ann Arbor | 30 | 26 |

| 18 | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai | 82 | 60 |

| 18 | University of California – Los Angeles (Geffen) | 71 | 71 |

| 18 | University of Chicago (Pritzker) | 62 | 54 |

| 21 | University of California – San Diego | 40 | 23 |

| 22 | Baylor College of Medicine | 25 | 28 |

| 23 | Emory University | 60 | 41.8 |

| 24 | University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center | 35 | 45 |

| 25 | Case Western Reserve University | 42 | 39 |

| 26 | University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill | 40 | 40 |

| 26 | University of Colorado | 36 | 40 |

| 28 | University of Southern California (Keck) | 22.6 | 24.2 |

| 28 | Ohio State University | 18 | 16 |

| 30 | University of Virginia | 48 | 32 |

| 30 | Oregon Health and Science University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 32 | University of Maryland | 15 | 24 |

| 32 | Boston University (Chobanian & Avedisian) | 65 | 30 |

| 32 | University of Rochester | 26.3 | 23.4 |

| 35 | University of Alabama – Birmingham | 30 | 28 |

| 35 | Brown University (Alpert) | 38 | 30 |

| 35 | University of Utah | 27 | 21 |

| 35 | University of Florida | 50 | 48 |

| 35 | University of Wisconsin – Madison | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 35 | University of Cincinnati | 30 | 28 |

| 35 | University of Minnesota | 38 | 66 |

| 42 | Albert Einstein College of Medicine | 55 | 44 |

| 42 | Indiana University – Indianapolis | 30.4 | 37.4 |

| 44 | University of Iowa (Carver) | 13 | 24 |

| 44 | University of Miami (Miller) | 60 | 45 |

| 44 | University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School | 24 | 44 |

| 44 | University of California – Irvine | 49 | 25 |

| 48 | Dartmouth College (Geisel) | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 48 | Wake Forest University | 54 | 31 |

| 50 | University of South Florida (Morsani) | 50 | 30 |

| 50 | University of Texas Health Science Center – San Antonio | 51.5 | 70 |

| 50 | University of California – Davis | 24 | 24 |

| 53 | Georgetown University | 50 | 33 |

| 53 | Tufts University | 32 | 37.5 |

| 53 | University of Connecticut | 21 | 33 |

| 56 | University of Texas Health Science Center – Houston (McGovern) | 20 | 20 |

| 56 | Medical University of South Carolina | 35 | 20 |

| 58 | Stony Brook University – SUNY (Renaissance) | 40 | 50 |

| 58 | University of Nebraska Medical Center | 30.6 | 25.6 |

| 58 | Thomas Jefferson University (Kimmel) | 60 | 25 |

| 58 | University of Illinois | 58 | 42 |

| 58 | George Washington University | 10 | 22 |

| 63 | University of Arizona – Tucson | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 64 | Virginia Commonwealth University | 56 | 50 |

| 64 | University of Kentucky | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 64 | University of Vermont (Larner) | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 64 | Texas A&M University | 33 | 14.3 |

| 68 | Hofstra University/Northwell Health (Zucker) | 42 | 41 |

| 68 | Rush University | 26.5 | 26.5 |

| 68 | Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School – New Brunswick (Johnson) | 30 | 25 |

| 71 | Temple University (Katz) | 36 | 34 |

| 71 | University of Tennessee Health Science Center | 59.6 | 59.8 |

| 71 | Wayne State University | 27 | 20 |

| 71 | Rutgers New Jersey – Newark | 30 | 25 |

| 75 | University of Kansas Medical Center | 39.2 | 34.8 |

| 76 | University at Buffalo – SUNY (Jacobs) | 40 | 25 |

| 76 | University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences | 46.6 | 51.6 |

| 76 | University of Oklahoma | 70 | 48 |

| 79 | Augusta University | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 79 | Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine | 32 | 20 |

| 81 | University of Hawaii – Manoa (Burns) | 40.5 | 36.11 |

| 81 | Virginia Tech Carillion School of Medicine | 22.2 | 27.3 |

| 81 | University of Louisville | 20 | 18 |

| 81 | University of New Mexico | No comparative data | No comparative data |

| 85 | Saint Louis University | 31 | 32 |

| 85 | University of Missouri | 13 | 17 |

| 87 | West Virginia University | 15 | 15 |

| 88 | Drexel University | 34 | 38 |

| 88 | SUNY Upstate Medical University | 18 | 14 |

| 88 | Michigan State University College of Human Medicine (Broad) | 39 | 26 |

| 88 | University of Missouri – Kansas City | 30 | 37 |

| 92 | New York University – Long Island | 56.3 | 52.1 |

| 93 | Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine | 13.33 | 6.67 |

| 94 | University of South Carolina | 13 | 33 |

| 95 | University of Nevada – Reno | 31.14 | 36.49 |

| 96 | Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center | 26 | 25 |

| 96 | University of California – Riverside | 20 | 20 |

| 98 | University of Central Florida | 45 | 48 |

| 98 | Florida State University | 24 | 23 |

| 100 | Eastern Virginia Medical School | 35 | 40 |

References

- 1.Residency data & reports. NRMP. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/residency-data-reports/.

- 2.Ramakrishnan D., Van Le-Bucklin K., Saba T., Leverson G., Kim J.H., Elfenbein D.M. What does honors mean? National analysis of medical school clinical clerkship grading. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Examination results and scoring | USMLE. https://www.usmle.org/scores-transcripts/examination-results-and-scoring Accessed September 5, 2023.

- 4.Fagan R., Harkin E., Wu K., Salazar D., Schiff A. The lack of standardization of allopathic and osteopathic medical school grading systems and transcripts. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerman M.E., Boe C., Bole R., et al. Evaluation of medical school grading variability in the United States: are all honors the same? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2019;94(12):1939–1945. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vokes J., Greenstein A., Carmody E., Gorczyca J.T. The current status of medical school clerkship grades in residency applicants. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(2):145–149. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00468.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visingardi J.V., Inouye B.M., Feustel P.J., Kogan B.A. Variability in third-year medical student clerkship grades. J Urol. 2022;208(5):952–954. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The best medical schools for research, ranked. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings Accessed September 29, 2023.

- 9.Harris D., Dyrstad B., Eltrevoog H., Milbrandt J.C., Allan D.G. Are honors received during surgery clerkships useful in the selection of incoming orthopaedic residents? Iowa Orthop J. 2009;29:88–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su C.A., Furdock R.J., Rascoe A.S., et al. Which application factors are associated with outstanding performance in orthopaedic surgery residency? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023;481(2):387. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein A.D., Jazrawi L.M., Elbeshbeshy B., Della Valle C.J., Zuckerman J.D. Orthopaedic resident-selection criteria. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(11):2090–2096. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200211000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilling D.C. Using the clerkship shelf exam score as a qualification for an overall clerkship grade of honors: a valid practice or unfair to students? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2019;94(3):328–332. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazio S.B., Papp K.K., Torre D.M., DeFer T.M. Grade inflation in the internal medicine clerkship: a national survey. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(1):71–76. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.741541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 12(3):e7492. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bergquist S., Otten T., Sarich N. COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(4):623–638. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]