Abstract

Introduction:

There is a growing number of older adults (≥65 years) who live with type 1 diabetes. We qualitatively explored experiences and perspectives regarding type 1 diabetes self-management and treatment decisions among older adults, focusing on adopting care advances such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

Methods:

Among a clinic-based sample of older adults ≥65 years with type 1 diabetes, we conducted a series of literature and expert informed focus groups with structured discussion activities. Groups were transcribed followed by inductive coding, theme identification, and inference verification. Medical records and surveys added clinical information.

Results:

29 older adults (age 73.4 ± 4.5 years; 86% CGM users) and four caregivers (age 73.3 ± 2.9 years) participated. Participants were 58% female and 82% non-Hispanic White. Analysis revealed themes related to attitudes, behaviors, and experiences, as well as interpersonal and contextual factors that shape self-management and outcomes. These factors and their interactions drive variability in diabetes outcomes and optimal treatment strategies between individuals as well as within individuals over time (i.e. with aging). Participants proposed strategies to address these factors: regular, holistic needs assessments to match people with effective self-care approaches and adapt them over the lifespan; longitudinal support (e.g., education, tactical help, sharing and validating experiences); tailored education and skills training; and leveraging of caregivers, family, and peers as resources.

Conclusions:

Our study of what influences self-management decisions and technology adoption among older adults with type 1 diabetes underscores the importance of ongoing assessments to address dynamic age-specific needs, as well as individualized multi-faceted support that integrates peers and caregivers.

Keywords: Older adults, type 1 diabetes, technology, continuous glucose monitoring, qualitative analysis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

As the US population ages and clinical care and self-management approaches for type 1 diabetes improve, the size of the older adult (OA) population (≥65 years) with type 1 diabetes has grown and is expected to rapidly increase in the coming decades.1 Given the recent emergence of this population, the experiences, barriers, and perceptions that shape behavior and clinical outcomes among OAs have not been well-characterized.2

At the same time, technological approaches to type 1 diabetes management like continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) have become standard of care.1 Studies show CGM may improve glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), improve glycemic variability, reduce risk of hypoglycemia and improve quality of life in OAs with type 1 diabetes.3–5 Despite documented benefits, CGM uptake among OAs with type 1 diabetes is low. A 2020 review article stated critical gaps in the evidence base included (a) limited knowledge surrounding OA with type 1 diabetes, their experiences, and the experiences of caregivers; and (b) use of diabetes technology, including need to learn more about OA perspectives to support adoption of and adaptation to new technological therapies.6

A strength of qualitative research is in-depth and nuanced elucidation of individuals’ perspectives and experiences, in addition to the contexts in which these perspectives and experiences operate.7,8 Our objective was therefore to rigorously conduct and report a qualitative study of the experiences and perspectives of OAs towards type 1 diabetes self-management and adopting new care advances, like CGM, in order to inform future efforts aimed at supporting optimal type 1 diabetes management in this population.

Methods

To support rigorous research and reporting, we selected the Total Quality Framework (TQF), a comprehensive set of evidence-based criteria for limiting bias and promoting validity in all phases of the applied qualitative research process.9 The TQF is comprised of four criteria to guide design and evaluation of qualitative research –credibility, analyzability, transparency, and usefulness. Table 1 describes the rationale for critical methodological choices undertaken in the present study or directs the reader to where each is discussed in the report. In addition to following TQF guidance for reporting, we report our research process and results according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) to facilitate critical appraisal and comparisons with other studies.10 Additional information on our use of qualitative research conduct and reporting guidelines can be found in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Total Quality Framework (TQF) Criteria for Planning, Conducting, Interpreting, and Evaluating Applied Qualitative Research*

| Criterion | Methodological Decisions | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility | Clearly defined target population | See “Methods – Participants” in report |

| Assessment of extent to which population sample is incomplete and implications of this omission for study conclusions | See “Discussion (para 7–8)” in report | |

| Sample design and size | For this pilot study that was limited in resources for recruitment and focus group facilitation logistics, we elected to recruit older adults with type 1 diabetes from a hospital-based outpatient endocrinology clinic. Recruitment was conducted on a rolling basis. Saturation was defined as the point when no new or original themes emerged.9 Because the same moderator and assistant led the groups, ARK and CS periodically assessed saturation of themes that emerged from discussion and group model building activities. Verification of saturation achievement was sought out by presenting preliminary themes to research mentors LAY and KHL who have extensive experience and training in clinical diabetes care for older adults and group model building. Recruitment was halted when consensus was reached that saturation had been achieved. We sought to conduct groups with 4–5 participants to maintain required COVID social distancing spacing in the room where the groups were able to be conducted, minimize intimidation of speaking in a larger group and because groups with <10 participants have been noted to promote depth and focus of discussion.9 We also conducted groups of variable sizes to accommodate participant availability and because dyads and triads have been shown to be particularly useful for rich data not too dissimilar from in-depth interviews. Groups were conducted separately with those who currently used CGM and those who formerly or never used a CGM, which was initially identified via medical record screening and confirmed by participant self-report. Because understanding perspectives and experiences about CGM was a prominent interest to our study and potentially a sensitive topic, we sought group homogeneity on this behavior to increase participant comfort in sharing thoughts with people who have lived through similar experiences and increase the nuance of our understanding of the reasons for use and non-use. Older adults vary in age, physical/cognitive limitations, relationships, and resources, and we therefore anticipated variability in the extent to which family members or other caregivers would be involved in older adult diabetes management. In order to limit introducing bias to our sample, we thus let all prospective participants choose whether to invite a caregiver to attend the groups with them. |

|

| Strategies to gain access and gain cooperation from participants | Selection of facilitated group model building process, which accommodates different forms of expression and support multiple ways for older adults to share their perspectives (See Methods – Data Collection (para 1) in report). In order to promote participant cooperation and honesty and minimize risk of participants disclosing what they thought were the ‘right answers’ that the moderator wanted to hear, the moderator prefaced each group by explaining the objectives of the research, as well as emphasizing that the participants were experts from whom the researchers sought to learn, and that all thoughts related to the research objectives were valuable. As part of efforts to build rapport with and promote uninhibited disclosure by participants, the moderator disclosed her own type 1 diabetes status to participants in her introduction given the possibility that participants might be less forthcoming with a moderator who was markedly younger and appeared unrelatable. An icebreaker prompted participants to describe their favorite thanksgiving food or candy and an open-ended prompt asked the participants to share their relationship with diabetes in order to naturally initiate group rapport building and discussion about the research objectives. All participants were prompted to share in order to prevent against dominance by extroverted participants. At the end of each group, participants were also given the opportunity to write down any additional information they felt was relevant but did not raise in the course of the discussion or felt was too private to share with the group. In order to limit bias introduced by the moderator, attention was paid to use neutral language in facilitating the group so as not to give participants indication that some responses were more right than others. The same moderator, the principal investigator (ARK), led the discussions and activities to promote consistency in quality of data gathered across groups and prevent against erroneous claims that variations in data exist because of variation in discussion guide coverage across groups.9 |

|

| Selection of constructs and attributes that map to research objectives | See “Methods – Data Collection (para 1)” in report | |

| Selection of data collection mode | See “Methods – Data Collection (para 1)” in report | |

| Operationalization of constructs and attributes in the form of a data collection tool | See “Methods – Data Collection (para 1)” in report | |

| Evaluation of data collectors as sources of bias and inconsistency | See “Strategies to gain access and gain cooperation from participants” in present table |

|

| Analyzability | Context and subject matter guided transcription | See “Methods – Data Processing and Analysis (para 1–3)” in report |

| Coding format that standardizes way data are processed | The principal investigator (ARK) along with two analysts (ACS, CS) with training and research experience in type 1 diabetes and qualitative methods read through all transcripts from the perspective of the research objectives and constructs of interest. Each analyst then independently inductively coded a different subset of all transcripts before meeting to discuss a preliminary set of codes to ensure that the codes were representative of the full range of data. Once analysts reached consensus about the draft codebook, each analyst independently applied the codebook to the same subset of transcripts, after which they met to compare code applications, resolve discrepancies, and revise the codebook. This process of codebook revision was repeated until all transcripts were coded. Two of the analysts (ACS, ARK) independently applied the final codebook to all transcripts and the third analyst (CS) compared code application and compiled any remaining divergences. All analysts then met to achieve consensus on final coding of all transcripts. | |

| Systematic identification of themes interpretations from the data | Once coding consensus was achieved by all analysts (ACS, ARK, CS), two analysts (ACS, ARK) independently identified categories across codes and identified themes within and across categories and summarized them independently. | |

| Verification of accuracy of the data, themes, and interpretations | A set of final results, interpretations, and implications were reached by analysts by a) comparing and reconciling those that they had independently drawn b) looking for data that contradicted analysts’ claims (i.e., deviant case analysis) and c) seeking verification by researchers with subject matter expertise and who had been involved in supporting research conceptualization, data collection and processing (CS, LS, RM). | |

| Transparency | Complete disclosure of all aspects related to study design, data collection, and analysis | Throughout report and the present supplement, by explaining rationale for methodological choices according to the Total Quality Framework (TQF) and ensuring reporting conforms to the TQF and Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).9,10 |

| Discussion of specific aspects of design, data collection, and analysis processes that impact outcomes and interpretations of data | ||

| Usefulness | Evaluation of relevant questions for researchers and users of research | Answers to the following questions can be found in “Discussion” in the report: • What can and should be done with the study now that it has been completed? (para 2–6) • Has the study identified important knowledge gaps that future research should try to help close? (para 7–8) • Has the study offered recommendations for action that are worthy of further testing or worthy of actionable next steps? (para 2–6) |

| Inclusion of “Usefulness of the study” section to articulate and justify how study should be interpreted, acted upon, or applied in other research contexts in the real world | See “Discussion” in report |

Roller, Margaret R., and Paul J. Lavrakas. Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach. Guilford Publications, 2015.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were ≥65 years of age at the time of recruitment, understood written/spoken English, type 1 diabetes diagnosis, used an insulin regimen of pump or multiple daily injections, HbA1c ≤86 mmol/mol (10.0%), and managed diabetes independently or with the help of a caregiver. All participants could invite a caregiver, defined as providing daily or regular care or support for the OA with type 1 diabetes. Exclusion criteria were <1 full COVID-19 vaccination series, diagnosis of dementia or a medical condition that investigators determined might interfere with discussion completion.

A convenience sample was recruited on a rolling basis from the outpatient endocrinology clinic at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in November- December 2021. Electronic health record screening of appointments June 2021 - May 2022 identified potentially eligible participants who were contacted through email and telephone. A standardized recruitment script informed participants about the study and written informed consent was given before participation. Table 1 summarizes the rationale for sampling method, size, and composition of the groups (2–5 people, stratified by CGM use).

Data collection

We adapted a facilitated group model building (GMB) approach, which is designed to provide a participatory structure for stakeholders to practice systems thinking and exchange their perceptions and experiences to collectively consider the causes of and solutions to complex problems.11–14 GMB approaches generate qualitative data through facilitated brainstorming, exercises, discussions, and drawing activities.11,14 We selected this data collection mode to fit our overarching objective to engage OAs as research collaborators in identifying how to support more optimal type 1 diabetes management and outcomes. The strengths of this method include multiple ways for participants to contribute insights and perspectives. Social interactions inherent to the focus group format also promote depth and range of data, which are naturally stimulated by points of convergence and divergence that arise through discussion.9 The facilitation script included an introduction to systems thinking and subsequent sections elicited conversations about the complexities of type 1 diabetes management in OAs. Specifically, prompts and activities were used to characterize the multi-level (e.g., individual, interpersonal, social, economic) and interacting determinants of CGM use or non-use over time, as well as determinants of self-management behaviors and outcomes more broadly. Additional prompts elicited suggestions about strategies to target these factors. Discussion guides and activities were informed by existing literature on diabetes management in OAs and expert input (LAY, RW, KHL). Methodology for all data collection procedures have been described in detail.15

For each discussion, the principal investigator and moderator (ARK) was supported by a research assistant familiar with the topic area (CS), who helped gather consent forms and answer questions throughout the discussion. Efforts undertaken to limit moderator and participant bias and to gain cooperation are described in Table 1.

To facilitate characterization of our sample and comparisons to our target population, as well as to contextualize results and inferences, participants completed questionnaires and medical records were reviewed to collect information about age, sex, race/ethnicity, type of health insurance, diabetes duration, HbA1c, severe hypoglycemia episodes, diabetes complications, insulin pump use, smart phone use, and current or prior CGM use.

Data processing and analysis

Groups were audio-recorded and transcribed by a professional service. Before analysis, transcripts were de-identified and verified by the investigator who led the groups (ARK).

Group Discussion Analysis

The main analysis focused on the group discussions. We conducted inductive coding and analysis according to TQF guidance in Atlas.ti.9,16 Detailed summaries of the data processing and analysis methodology are in Table 1. Descriptive statistics from questionnaire and medical record data were calculated in R Statistical Software (v3.6.0; Vienna, Austria)17

Side Discussion Analysis

During all group discussions, participants not only engaged in the formal questions and activities prompted by the moderator, but also engaged in various side discussions about diabetes strategies, knowledge, and experiences. Informal conversations are routinely analyzed as part of ethnographic research, but more recently have been recognized as an important yet underutilized part of other types of qualitative research.18 A separate inductive coding exercise was thus undertaken to focus on the side discussions that took place during all focus groups with the objective that systematically analyzing the content of these exchanges for the types of support and topics that OA sought out could therefore inform future care strategies to promote well-being in this population. More detail on the methods used for this analysis of side discussions can be found in Appendix 1.

Results

Thirty-three OAs and caregivers participated in one of nine in-person groups. The sample has been characterized in detail elsewhere.19 29 participants were OAs living with type 1 diabetes (age 73.4 ± 4.5 years) and 4 were caregivers (age 73.3 ± 2.9 years). All caregivers were spouses. The combined sample was 58% female, 82% non-Hispanic White, with a mean age of 73.4±4.3 years. Of participants living with diabetes, the majority were smartphone users (97%) with a high prevalence of CGM (86.2%) and insulin pump (78.9%) use. Mean HbA1c was 51±10 mmol/mol (6.8±0.9%), and more than half reported a history of severe hypoglycemia. The mean number of endocrinology visits in the past year was 3.4±0.9.

Attitudes, behaviors, and experiences that shape type 1 diabetes treatment decisions and self-management among older adults

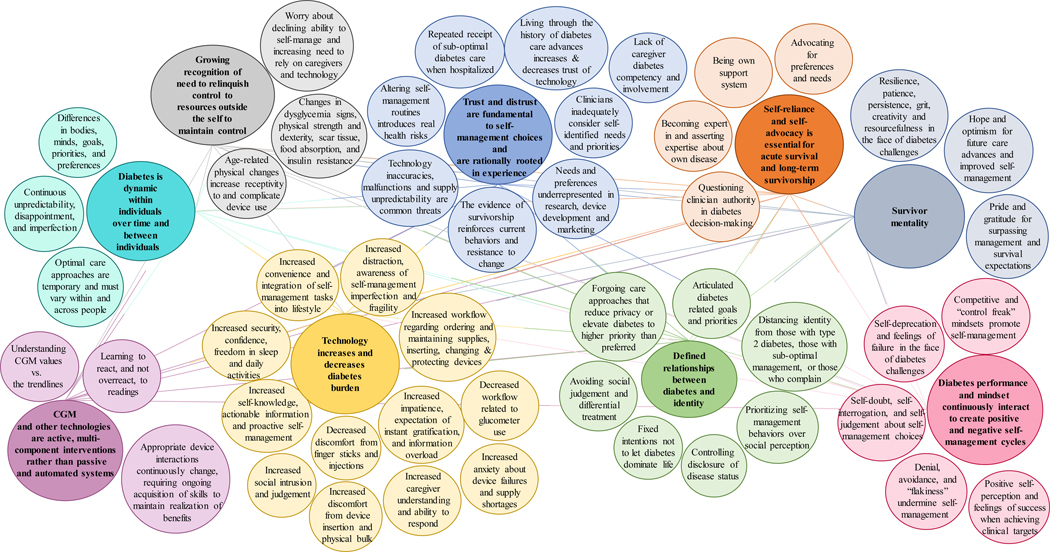

Figure 1 depicts the main themes (large circles) that emerged in our sample regarding the attitudes, behaviors, and experiences (small circles) that shape decision-making, self-management, and outcomes among OAs with type 1 diabetes. Select participant quotes that illustrate the themes can be found in Table 2. These themes are also described below:

Figure 1. Interrelated attitudes, behaviors, and experiences of ‘lived expertise’ in type 1 diabetes shape treatment decisions and self-management in older adults.

Main themes are denoted by large circles, and related attitudes, behaviors, and experiences that shape decision-making, self-management, and outcomes are shown in small circles.

Table 2.

Attitudes, Behaviors, and Experience of ‘Lived Expertise’ in Type 1 Diabetes

| Theme | Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences that Illustrate Theme | Select Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Survivor mentality | • Resilience, patience, persistence, grit, creativity and resourcefulness in the face of diabetes challenges • Pride and gratitude for surpassing management and survival expectations • Hope and optimism for future care advances and improved self-management |

“Either live with it, or you die with it. One or the other. I have been diabetic for 62 years and I’m still ticking. You just basically do what you have to do and just adjust as you go.” (I4, T3) ”[Needles] used to make me throw up. I was that bad about needles. I hated needles. When they told me I was a diabetic and I had to take shots, I said to the doctor, ‘So what happens if I don’t?’ He said, ‘You’ll feel bad the first day, you’ll feel really bad the second day, and the third day, you’ll be dead.’ I thought, ‘That’s not really what I wanna do’, so I started taking shots, and I did really well up until the point I was at five shots a day.” (I1, T7) “On my 40th birthday, my mother told me that a doctor told her when I was 14, that if I took really good care of myself, I could live to be 40, but he would expect me to be dead by the time I was 40…he was giving me 26 years.” (I2, T7) “I keep asking [Dexcom]. I keep calling. The people are wonderful, they really are attentive to the need [of older adults], and it works. Maybe someday when I get a little older, I’ll be able to do it without help, but not yet.” (I1, T1) |

| Self-reliance and self-advocacy are essential for acute survival and long-term survivorship | • Advocating for preferences and needs • Being own support system • Becoming expert in and asserting expertise about own disease • Questioning clinician authority in diabetes decision-making |

“I’m in charge of my diabetes. You have to be your own advocate.” (I3, T2) “My support system is myself. I am married. I’ve been married 47years. My husband, the only thing he’s every known to do is to get me juice if he sees me sweating or if I start acting funny in the bed and shaking”. (I3, T2) “You have to be able to take what you got for information and make an assessment on how your body functions. That’s one thing about diabetes is you have to learn how your body functions, not hers, his, or hers. It’s your own. (I4, T3) “I essentially realized I had to become my own doctor and [not just to] understand what doctors were saying, but to have a higher level of conversation with the doctors to improve my care.” (I4, T2) “There’s nobody who knows the patient better than the patient. They [doctors] often don’t believe us. Sometimes, we’re wrong, but they at least need to listen” (I5, T2) |

| Theme | Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences that Illustrate Theme | Select Illustrative Quotes |

| Trust and distrust are fundamental to self-management choices and are rationally rooted in experience | • Needs and preferences underrepresented in research, device development and marketing • The evidence of survivorship reinforces current behaviors and resistance to change • Clinicians inadequately consider self-identified needs and priorities • Repeated receipt of sub-optimal diabetes care when hospitalized • Technology inaccuracies, malfunctions, and supply unpredictability are common threats • Altering self-management routine introduces real health risks • Lack of caregiver diabetes competency and involvement • Living through the history of diabetes care increase and decrease trust of technological advances |

“When I first got my CGM, they said, “Watch this video of this little girl putting on her CGM,” and I thought, that’s not me [laughter]…that’s not me trying to do it. It’s her daddy doing it to her, and it just—those kind of things didn’t translate” (I2, T7) “[Older adults] they need to [be] brought in and sat down to see if they really want it. Then you tell them how it’s going to work and how it’s going to help them. You have to almost show them because most older adults, they feel like, “I’ve gotten to this age because I know whatI’m doing.” (I2, T4) “I’ve been to some [providers] that were not as open to my health concerns. I said, “I can’t stay here.”…so I just moved right along.” (I4, T8) “That sensor, I was tryin’ to change it myself. I just got so frustrated because he [my husband] was not available, and my daughter wasn’t available. I’m sayin’, ‘to heck with it’” (I4, T8) “I3: Sometimes, it tells me that I’m low and dangerously low. Low, low, low, low. I’m like, what the heck? I know I’m not low. I just drank juice 30minutes ago….” I5: Yeah…because your Dexcom reads interstitial glucose…it’s always gonna be slower. I can’t tell you the number of times that Dexcom has read higher than the glucometer or lower than the glucometer, which is the wrong way around, so go figure.” (T2) |

| Growing recognition of need to relinquish control to resources outside the self to maintain control with age | • Worry about declining ability to self manage and increasing need to rely on caregivers and technology • Changes in dysglycemia signs, hypoglycemia unawareness, physical strength and dexterity, scar tissue, food absorption, and insulin resistance • Aging-related physical changes increase receptivity to and complicate device use |

“The older you get, if you don’t have a caregiver.. Like my mom, she died when she was 90. She was just tired. She was tired of doing all what she had to do to keep her health good” (I4, T6) “What finally convinced me was reading stories about how, as you get older, your chances of having a really severe debilitating low blood sugar go up, which totally surprised me. I would have thought that, you know, ‘Hey, man. I don’t have all that hormonal stuff going on [anymore]’.” (I3, T3) “Me, now, aging, [I’m] more brittle than I was… now, the alarms, for me, is a safeguard.” (I4, T8) |

| Theme | Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences that Illustrate Theme | Select Illustrative Quotes |

| Defined relationships between diabetes and identity | • Articulated diabetes-related goals and priorities • Fixed intention not to let diabetes dominate life • Forgoing care approaches that reduces privacy or elevates diabetes to a higher priority than preferred • Controlling disclosure of disease status • Prioritizing public self-care behaviors over social perception • Distancing self from with those with type 2 diabetes, those with sub—optimal management, and those who complain • Avoiding social judgement and differential treatment |

“If it [the way I’m self-managing] isn’t broke, there’s nothing to fix…if we need to have a discussion over my goal or I’m not reaching my goal or whatever, then let’s talk about that, but as long as I’m reaching goal and I’m happy with my life and my experience trying to manage this disease on a daily basis, then let’s leave well enough alone.” (I3, T7) “I am still very much in a horse and buggy era. It’s my temperament. and I’m a little resistant to—like people wanna know things …why do you want to know so much?” (I1, T1) “Do you go out of your way to make sure people don’t know you’re diabetic? ‘Cause I do…I don’t want anybody to know. I’m okay, and I don’t want people somehow feeling sorry for me or saying, no, you can’t do that…” (I2, T7) “I did not wanna be the poster child for type I diabetes, so—I don’t deny it. I won’t if somebody asks me. I’m happy to admit it, but I don’t go around advertising myself. It’s not in me, ‘cause I’m a very—I’m private, too, and it’s none of anybody’s business.” (I3, T7) |

| Diabetes is dynamic within individuals over time and between individuals | • Continuous unpredictability, disappointment, and imperfection in symptoms and management • Differences in bodies, minds, goals, priorities and preferences • Living through the history of diabetes care increases and decreases receptivity to care advances • Optimal care approaches are temporary and must vary within and across people |

“You know, “I’m eating the same stuff I ate yesterday, but my blood sugars, they’re not completely gone [out of range], but they’re much higher. What’s going on?” (I2, T3) “I’ve had diabetes since August of 1969. My goal at diagnosis was—because I was fairly familiar with diabetes—was to not let this disease impact my life any more than it absolutely needed to. I don’t use a pump. I don’t use CGM. I have been at goal for 20 years, just with the tools available—the really basic tools available, and frankly, I like it that way “ (I3, T7) “A lot of illnesses and disease, you pretty much treat ‘em all the same. One thing I found about diabetes is just totally different from one person to the other person” (I1 T6) |

| Theme | Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences that Illustrate Theme | Select Illustrative Quotes |

| Diabetes outcomes and mindset continuously interact to create positive and negative self-management cycles | • Positive self-perception and feelings of success when achieving clinical targets • Self-deprecation and feelings of failure when facing diabetes challenges • Self-doubt, self- interrogation, and self-judgement about self-management choices • Denial, avoidance, and “flakiness” undermine self-management • Competitive and “control freak” mindsets promote self-management |

“One of the things that occurs to me is something that really underlies all of this, is the attitude I had about my diabetes from the very first day I got it” (I2, T7) “The better control you have, the better you feel about yourself” (I2, T1) “I’m a good girl. You ask Dr. [Name], she tells me I’m her number one patient, that I have the best readings of all her patients” (I4, T6). “I was not a technology guy, and then I’m trying to do this, the CGM monitor, and the phone, and that’s when I think I just got overwhelmed because I thought this was supposed to help, and right now, it’s just—it’s overwhelming my very simple mind” (I1, T7) “I got frustrated, and then I said I think I’m a failure and quit” (I1, T7) “You wonder, am I being stupid when the doctor says ‘you should try one’ and I say I don’t need it” (I2, T7) “Some people are gonna have a permanent denial. I’ve seen it. My father died of diabetes because he just simply didn’t wanna take the shots. I sat there and I took three, four shots every day all the time, and he wouldn’t do it. He saw what it did for me, and he just wouldn’t do it.” (I4, T3) |

| Theme | Attitudes, Behaviors and Experiences that Illustrate Theme | Select Illustrative Quotes |

| Technology increases and decreases diabetes burden | • Decreased workflow related to glucometer use; increased workflow related to ordering and maintaining supplies, inserting and changing devices, and navigating insurance; increased anxiety about device failures and supply shortages • Increased security, confidence, freedom in sleep and daily activities; Increased convenience and integration of self-management into lifestyle; Increased distraction, awareness of self-management imperfection and fragility • Increased self-knowledge, actionable information, and proactive self-management; Increased impatience, expectation of instant gratification, and information overload • Increased caregiver understanding and ability to respond; increased social intrusion and judgement • Decreased finger sticks and injections; Increased discomfort from device insertion and physical bulk |

“I3: Self-confidence in any daily activity, whether it’s camping –you’ve got your backup system. You’ve got your system to warn you of the lows and the highs, and you know how to take care of it …I know I can go for a three mile run ‘cause I’ve got this thing to help me. I know I can drive to the beach by myself because I’ve got this system. I5: It’s flying solo, right? I3:Yeah. Flying solo.” (T2) “[CGM] helps us to become more in tune to our bodies” (I2, T3) “I felt more in control of my life. I had a feeling of security.” (I3, T9) “‘I’ve become more brittle. It’s made me more aware I’m brittle…[it] causes more anxiety and, sometime, limits my freedom where I would’ve just continued because before [when] I [just] had my pump, I would check my finger before and after. See, now, it’s a constant reminder”. (I4, T8) “The first is, it’s a piece of equipment hanging off me 24 hours a day. The second is, the flood of data that I am getting 24 hours a day that I must cope with…I don’t wanna live that way…that was my thing, was, ‘I have one more thing’, ‘cause I already had the pod, and then I was gonna have to do this other thing and try to make sure all that was working”. (I3, T7) “What do I do when I go to an airport? Do I take it out? Do I put it—should I put everything in my pocketbook? Should I go through with it on? Should it go through the—in a suitcase? What should you do? ‘Cause you don’t know what to do. You don’t want to screw something up.” (I1, T2) |

| CGM and other technologies areactive, multi-component interventions rather than passive and automated systems | • Understanding the values vs. the trendlines • Learning to react, and not overreact, to readings • Appropriate interaction with the technology is always changing, requiring ongoing acquisition of skills to maintain benefits |

“What was hard is trying to remember that…the graph on the Dexcom is telling me what has happened to some extent, but not as reliably as I would like it to be. It’s telling you what’s going to happen if it’s got an upward arrow or a double whammy north or south, but that’s still an estimate.” (I5,T2) “Let’s just say there’s 10 things that are affecting how you’re gonna react to this particular meal, or whatever. You might have information about six of them. There is gonna be a lot of variability, day-to-day, meal-to-meal.” (I3, T3) “It’s a learning curve…we aren’t the same every day, all day.” (I1, T3) |

Abbreviations: I – Interviewee. T – Transcript.

“Diabetes is dynamic within individuals over time and between individuals” and “Technology increases and decreases diabetes burden”

Importantly, the attitudes, behaviors, and experiences in Figure 1 were portrayed as continuously interacting with each other such that the management decisions and outcomes that they influenced were also continuously changing. Study participants emphasized variability between individuals with regards to how these factors shaped self-management decisions and outcomes, as well as variability within individuals over time –specifically with increasing age. This intra-and inter-individual heterogeneity was perceived as an inherent aspect of living with diabetes and a key reason why a new self-care approach (e.g., diabetes device) could a) increase diabetes burden for one individual and decrease it for another, as well as b) increase burden for an individual at one point over the course of self-management, and decrease it for that same individual at a different point in time:

“Chronic disease is like a roller coaster. It isn’t like a straight highway. The things in your environment and the things going on in your life and in your family can all impact chronic disease and how well you’re faring, as well as the disease processes themselves. I think the things that help you cope are going to be as varied as the things that are causing you to have problems. The coping skills that you need at one point in managing diabetes and your life with diabetes are gonna be different than they are five years in the future.” (Interviewee 3, Transcript 7)

“Survivor mentality” and “Self-reliance and self-advocacy is essential for acute survival and long-term survivorship”

Many OAs self-identified as survivors, particularly with respect to defying prognoses at their diagnosis, and they conveyed grit and resilience as central to handling the roller-coaster that that they described diabetes management to be. Participants also expressed that OAs who have been living with type 1 diabetes for many years carry a vast fund of wisdom related to diabetes management, and their survivorship is tangible proof of this ‘lived expertise’. In general, OAs in our sample self-advocated that their insights, skills, and self-knowledge should be considered in clinical decision-making to promote well-being in this population, while simultaneously demonstrating humility and openness to unfamiliar care approaches due to witnessing the ever-changing history of diabetes care practices and having decades of experiences to prove to them that diabetes varies across and within individuals over time, and thus too, must ‘optimal’ approaches.

“Growing recognition of need to relinquish control to resources outside the self to maintain control with age”

Group discussions revealed that just as defined relationships between diabetes and identity and deeply entrenched self-reliance could impede OAs from adopting new approaches such as technology and caregiver support, openness towards these new approaches could also be enhanced through OAs’ growing acknowledgement of increasing physical and cognitive co-morbidities combined with their conviction that management techniques must be adjusted over the lifespan.

“Diabetes outcomes and mindset continuously interact to create positive and negative self-management cycles” and “CGM and other technologies are active, multi-component interventions rather than passive and automated systems”

Participants pointed out that the dynamism of diabetes makes the adoption of any new approach, including CGM, a complex undertaking that requires learning how to integrate the strategy into the management of a diverse number of unpredictable and ever-changing scenarios. They described this undertaking as even more complex for OAs due to the lower intuition around technology and the increased physical and cognitive challenges of this population. Participants also pointed out that despite the heightened management expertise and positive self-image conferred by survivorship, management ‘performance’ (e.g., time in range, HbA1c) ceaselessly influenced emotions and self-perception, and vice versa.

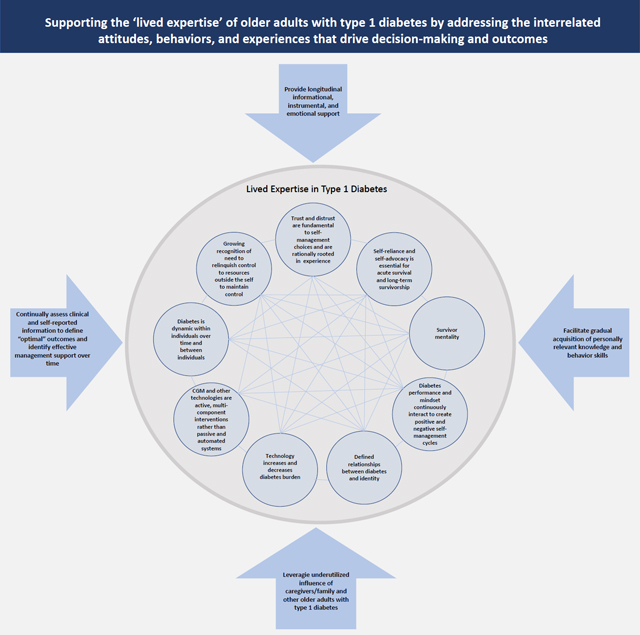

Strategies to support ‘lived expertise’ in type 1 diabetes

Our group discussions identified key strategies to address the behaviors, attitudes, and experiences of OAs and support type 1 diabetes self-management and outcomes throughout this life stage (Table 3).

Table 3.

Strategies to support the ‘lived expertise’ of older adults with type 1 diabetes

| Strategy | Description | Select Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Regularly conduct holistic needs assessments to match people with effective self-care approaches and adapt them over the lifespan | To match individuals with effective recommendations and support at the appropriate time, periodic assessments should combine clinical diabetes metrics and information about individuals’ attitudes and behaviors that shape diabetes-related decisions, management, and outcomes Suggested self-report metrics include: goals, priorities, and needs related to diabetes; satisfaction with current management and outcomes; level of trust and openness regarding technology; data overload, feeling overwhelmed by information; past and current technology use and skills; caregiver availability, nature of caregiver involvement, and willingness to involve caregivers; physical and cognitive limitations |

“I2: They could say, ‘Look, your A1Cs are really high, your blood sugar’s all over the place. I think this is something that would really help you control your blood glucose better’… I3: ..the flip side of that …’What problems are you having?”…’Here are some ways that a CGM might help the issues that you’re dealing with’….look at it from both the provider perspective as well as patient perspective” (T7) “Whether it’s not to be on a CGM or to be on a CGM or to take oral drugs…matching all those things up physically and then psychologically, making it make sense [for the patient].” (I1, T7) |

| Provide longitudinal multifaceted support | Informational, instrumental, and emotional support influence adoption and sustainment of care approaches and the combination of support types and pattern of delivering them across time will vary by individual |

“I had to go see a psychologist to work through switching from a shot that I hated to a pump, because then it meant that I was locked to the pump 24/7, and a shot, I could put on the shelf, and I didn’t see it the rest of the time.” (I1, T7) “Oh, my god, she [certified diabetes care and education specialist, was so patient and kind with me…When I get frustrated, after a while, I cry…I was just boo-hooing, and she was just, ‘you can do this. You can do this.’” (I2, T1) |

| Strategy | Description | Illustrative Quotes |

| Facilitate ongoing acquisition of personally relevant knowledge and behavior skills | Individually tailor information about new care approaches based on clinical and self-identified needs to empower comprehensive decisional balancing of relevant pros and cons Introduce information and skills over a more extended timeline to a) surmount emotional and psychological obstacles to altering existing care routines b) build behavioral competency with the different actions and reactions required between patient and technological device across diverse scenarios |

“Tailor the experience to their goals… it’s a continuing thing because your goals are gonna change over time when you’re living with a chronic disease.” (I3, T7) “One point…that I think, in general, is critical is the education component and simplifying things so that you’re not—I mean, I would get the Diabetes Forecast magazine, and I would try to read it and comprehend it make it make sense, and it was not me. I wanted it to relate to me. I think having…a slow rant of learning about the education of all this technology—instead of going, ‘Okay, we’re gonna switch you over to CGM, and you’re gonna get your stuff, and then you go ahead and get started’….That—especially as I’ve gotten older…I’m a slow adopter. I don’t want to just jump on board, and that’s why it took so long for me [to use a CGM].” (I1, T7) “The other thing to me would be having a real true sense of the learning style of the adult, because if they’re an auditory learner and you’re asking them to watch a video, or you’re not giving them hands-on and that’s all they know… it goes back to the customization because then you know the person and you’re not trying to put a square peg in this very round hole.” (I1 T7) |

| Leverage caregivers, family, and peers as resources | Caregivers and family members are key to behavior change and persistence, but support is needed to navigate tensions and build caregiver capacity to promote positive effects of caregiver involvement on management and outcomes Older adults highly weight and are eager to learn from the lived expertise of other older adults with type 1 diabetes, who also often provide superior levels of informational, instrumental, and emotional support as compared to other actors |

“I’m in the [name] diabetes center… they’ve got a 50 year old study… they have found that caregivers are a really critical part of your whole diabetes regimen. People that have them function much better and have much better control of all kinds of things.” (I3, T6) “In terms of caregivers…that’s a different world in terms of dealing with somebody on a CGM…if that person is partnered with the CGM user, that could change a lot of these outcomes.” (I1, T7) “Her caregiver could be a problem…” (I1, T4) “I5:… I think that maybe on even a monthly basis, if there was somebody at the clinic in between appointments checking just to see how that patient was doing and go, ‘hey… your variability has gone sky high, even though your A1C is okay, but that means…you’re having a lot of lows’. If it would had been me, what they would have said is, you’re overreacting to the data. Don’t wait for two more months. Make some changes now and talk through those changes… I4: In theory, that person is the diabetes educator. They don’t have the time. I5: Yeah. You’re right. The health care system isn’t really set up for that. Maybe it’s something as simple as having a workgroup, a user group, whatever you want to call it, and you could call me and say, “I’m a trained researcher too. You’re overreacting to your data.” Just that kind of support. It doesn’t have to be paid for by insurance.” (T2) “I2:It’s refreshing to talk to people who have the same problems and issues and share stories and stuff. I1: It is because sometimes you feel alone…you know,’I’m the only one in the world with diabetes’…” (T3) |

Abbreviations: I – Interviewee. T – Transcript.

Regularly conduct holistic needs assessments to match people with effective self-care approaches and adapt them over the lifespan

The inter- and intra-individual dynamism of diabetes underscored by OAs was described as requiring ongoing needs assessments that combine clinical and self-report metrics (e.g., trust of technology, diabetes-related goals, privacy preferences, learning style) in order to individualize the definition of ‘optimal’ outcomes, identify the malleable and potentially non-malleable factors relevant to self-management, and match individuals with effective approaches across time. Collecting self-reported metrics to facilitate provider-patient collaboration on the selection of treatment goals and strategies was conveyed as particularly important in the care of OAs whose survivorship confers decades of diabetes-related expertise (i.e., psychological, behavioral and physiological self-knowledge), as well as entrenched attitudes, behaviors, needs, preferences, goals, and priorities about diabetes that may or may not be modifiable –all of which significantly influence the success of care approaches proposed to OAs (e.g., CGM use), and consequently, health outcomes.

Provide longitudinal multifaceted support

Providing opportunities for informational (e.g., education), instrumental (e.g., tactical or technical help), and emotional support (e.g., sharing and validating experiences) was identified as crucial for both adoption and sustainment of diabetes technology and associated new self-management behaviors.20,21 All three types of support were articulated as important, given the complex interactions between knowledge, skills, emotion (e.g., anxiety, frustration, trust), self-management metrics (e.g., dysglycemia), and self-perception (e.g., feelings of failure, feeling in-control) that participants articulated shape behavioral and outcome trajectories.

Facilitate ongoing acquisition of personally relevant knowledge and behavior skills

The necessity of a more intensive and elongated timeline to support OA adoption of new treatments as compared to other age-groups was also emphasized due to age-specific factors. These age-specific considerations included lack of familiarity with and heightened distrust of technology, the involvement of multiple individuals in self-management (i.e., family, caregivers), as well as the behavioral inertia conferred by survivorship, habit, and the increased fragility of older age that make user errors or technological malfunctions potentially fatal and rationally feared.

Leverage caregivers, family, and peers with diabetes as resources

In addition to highlighting the importance of the clinical care team for influencing diabetes-related decisions as well as self-management behaviors like adoption and sustained use of CGM, group discussions identified caregivers and other OAs with type 1 diabetes as particularly impactful yet under-utilized support. They, along with device technical support staff, were proposed as more accessible and cost-effective resources given the limits of clinician support under the current healthcare system. Participants considered their peers –other OAs with type 1 diabetes– as largely unrivaled in their ability to provide all forms of support due to having built a portfolio of creative and practical strategies over decades of living with diabetes, as well as being able to relate to the dynamism of living with diabetes and the positive and negative psychological and behavioral feedback loops involved. In addition to these points being explicitly articulated by OAs in our discussions, 62% of the side discussions were related to informational support and 37% were related to sharing and sympathizing with experiences (Appendix 1). The most common informational support included advice on device use (e.g., placement, interpretation, extending use). These side discussions underscore that support is readily and eagerly exchanged when OAs with type 1 diabetes are convened, and thus point to the potential positive effects of facilitating these opportunities as part of clinical strategies to improve outcomes in OA when introducing OAs to new management approaches like CGM.

Discussion

Our investigation of experiences managing diabetes and adopting new approaches like CGM among a sample of OAs with type 1 diabetes revealed, above all, the complex and dynamic nature of managing type 1 diabetes over the lifespan. More specifically, our study identified 1) a concrete set of attitudes, behaviors, and experiences that continuously interact with each other to shape diabetes-related decisions and outcomes among OAs as well as 2) potential strategies to address the inter and intra-individual variability in these factors.

Our analysis provides valuable foundational information for future research efforts that aim to operationalize and trial strategies to improve well-being in this population, specifically through a) elucidating characteristics of clinical assessments and strategies that might address this complex system of attitudes, behaviors, and experiences that influence decision-making and outcomes b) highlighting the importance of assessing not only physiological metrics but also attitudes, behaviors, experiences related to diabetes management in order to individually tailor when and how providers propose OAs integrate a new approach into their self-management routines, and c) pointing out the necessity of periodically re-evaluating how OAs fare across these clinical metrics, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences after adopting a new self-management strategy in order to provide OAs with appropriate informational, instrumental, or emotional support at time points critical for behavioral perseverance.

Our provides additional insights into the interactions of OAs with emerging diabetes technologies such as CGM. Prior studies involving OAs and their perceptions of technology have shown that CGM can decrease management burden, such as by increasing security in sleep and confidence in daily activities, but can also increase anxiety due to technological inaccuracies as well as reduced privacy and control over the extent to which diabetes dominates daily life.22 Research also suggests that OAs who experience technical difficulties are less likely to trust CGM.23,24 Our study builds upon these findings by characterizing in great detail the multi-level barriers and facilitators that interact to influence adoption and sustainment of new management behaviors, including CGM. Our study also demonstrates that factors that facilitate or impede self-management, and whether a self-management approach is ultimately perceived as a net positive or negative, vary across individuals as well as within individuals over time.

Although previous research has documented the importance of involving caregivers in disease management for the well-being and longevity of OAs with chronic disease, and particularly with regards to interpersonal dynamics surrounding CGM,25,26 our study documents multiple practical, interpersonal, and psychological barriers to OAs’ realizing the health benefits of this strategy.27,28 Our results point to the complexity of caregiver involvement in OA diabetes management. Alongside the general conviction conveyed by OAs in our sample that relying on caregivers was important for diabetes management, and increasingly with age, participants expressed concern about intrusion, judgement, loss of privacy and independence when caregivers were involved in diabetes management, which was perceived as negatively impacting OA self-management via two pathways: by driving interpersonal conflict and other negative psychological effects and by restricting caregiver diabetes engagement and competency. That OAs in our sample described the importance of involving caregivers in their diabetes to support ongoing management and longevity alongside substantial challenges that impeded realization of positive effects highlighted the potential benefit of providing more structured support to OAs and their caregivers in order to address tensions and negotiate a constructive support routine that could be periodically revised as cognitive and physical limitations change or caregivers turn over.

Our results also highlight that effectively integrating caregivers into self-management requires ongoing assessments and informational, instrumental, and emotional support that include both caregiver and OA with type 1 diabetes.24,29 The overall low level of caregiver participation in our discussions (n=4) may in itself illustrate the complexity of constructively involving caregivers into self-management. By identifying various factors that influence caregiver involvement we provide an important foundation for the development of the content of these assessments and strategies to facilitate effective caregiver support.

Studies show social capital is an important aspect of well-being and longevity in OAs, and at the level of an individual, this construct relates to one’s social support system, social cohesion, and frequency of social interactions.30,31 Those with more social support better cope with stress and its physiologic effects, while those with less may become more frail.30,32 Research additionally indicates individuals with larger social networks self-report better health.31 Those who feel more connected to their community or to others who share similar defining characteristics (e.g., age, disease status) also have higher self-reported physical wellbeing.30 Our participants placed high value on interacting with and learning from other OAs with type 1 diabetes. Although this perceived value is likely influenced by the knowledge, skills and relatable experiences that OAs have amassed over a career of managing the unpredictability of type 1 diabetes, it also may be due to the social capital effects of interacting with other OAs with type 1 diabetes. As such, structuring groups of OAs as part of their ongoing clinical care could prove beneficial to health through multiple pathways, thereby supporting greater consideration of how to operationalize and formalize this strategy through future research. By identifying the factors OAs perceive as shaping their self-management and outcomes as well as characterizing the content of their side conversations with each other, our study usefully points out the types of support and topic areas (Appendix 1) that could be considered in further efforts to design and test effects of peer support in this population.

Although they did not emerge in our study, there may be gender differences in attitudes and behaviors that drive diabetes-related decisions and outcomes and strategies to address them. Further, due to our inclusion criteria, results and recommendations are of limited applicability to OAs with significant cognitive impairments such as dementia or those who seek diabetes care from a primary care provider. Investigating these lines of inquiry would be a valuable undertaking for improving management and outcomes among the broader population of OAs with type 1 diabetes.

Additional limitations include study participants were not involved in verifying data processing or analysis and our use of convenience sampling. Despite a small convenience sample, we achieved moderate representation of our target population across key characteristics, including sex and race/ethnicity, although technology use in our sample was high and average HbA1c met clinical targets. As often follows from clinic-based sampling, our sample was healthier and sought care more routinely than the general population meaning there may be additional key factors that influence outcomes and self-management behaviors in the broader population of OAs with type 1 diabetes that our study did not elucidate.33 Instrumental, or hands-on support, only encompassed 1–2% of side discussions, which could be due to the group discussion format (vs. OAs interacting with each other during activities of daily living) but could also be due to social distancing policies, and thus may have limited our understanding of how OAs could be leveraged to help each other within this support category. Validation of our findings in larger, more diverse samples is needed. Additional strengths include employing criteria to assess thematic saturation, intentional and systematic analysis of the side discussions held during focus groups, and verification procedures used throughout data collection, processing, analysis, and reporting by researchers and clinicians who have expertise in type 1 diabetes, OAs, and qualitative methods. Importantly, we used quality guidelines to guide our research and reporting to facilitate comparison with other studies and increase confidence in the rigor and use of findings to inform future research.

Ultimately, our findings provide useful direction for future efforts by holistically characterizing the ‘lived expertise’ of OAs with type 1 diabetes to elucidate key patient-perceived targets for one or more interventions as well as characteristics of strategies to improve self-management and well-being in this population.

Novelty Statement.

What is already known: Little is known about the perspectives of older adults with type 1 diabetes that shape treatment decisions and outcomes.

What this study has found: Focus group participants identified a set of interrelated factors operating at individual, interpersonal, and environmental levels. These factors vary in the way they shape diabetes self-management decisions and outcomes between individuals, and they also vary over time within individuals. Four strategies to address these factors and support diabetes management were identified by older adults and their caregivers.

What are the implications of the study: Identifying type 1 diabetes self-management barriers, facilitators, and strategies according to older adults informs future, patient-oriented research initiatives to improve clinical care and outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgements

Personal Thanks

The research team is indebted to the older adults with type 1 diabetes for their time and effort to participate in the group discussions. We are grateful to Noelé Daniels for her assistance with the study space and scheduling procedures. Damilola Ayinde, Kabir Dewan, Maya Loga, and Sharita Thomas provided research assistance during the group discussions.

Funding

ARK is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR002490. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The project was also supported by UL1TR002489 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and a research grant from the Diabetes Research Connection.

Appendix

Supporting the ‘lived expertise’ of older adults with type 1 diabetes: an applied focus group analysis to characterize barriers, facilitators, and strategies for self-management in a growing and understudied population.

Appendix A: Research conduct and reporting guidelines

For qualitative research to deliver on its purpose and generate accurate information that effectively informs research and practice, attention must be paid to ensuring methodological rigor throughout data collection, processing, analysis and reporting.9 However, there is widespread lack of a coherent set of criteria to systematically inform methodological decisions and promote quality throughout the research process, which threatens validity of results and inferences drawn from the research. Incomplete and unstandardized qualitative research reporting is also extremely common despite the availability of consensus guidelines, preventing readers from appraising the validity, relevance, and usefulness of study findings.10 Ultimately, these key weaknesses limit confidence in incorporating qualitative findings into future research and practice, resulting in persistent omission of the valuable perspectives of the very individuals that such efforts aim to support.

To support rigorous research and reporting, we selected the Total Quality Framework (TQF), a comprehensive set of evidence-based criteria for limiting bias and promoting validity in all phases of the applied qualitative research process (i.e., conceptualization, implementation, analysis, and reporting) to thereby promote confidence in using results from our study to inform future decision-making.9

The TQF is comprised of four criteria to guide design and evaluation of qualitative research –credibility, analyzability, transparency, and usefulness – all of which are shaped by methodological choices made throughout the conceptualization, implementation, evaluation, and reporting of research. Table 1 describes the rationale for each of these methodological choices undertaken according to these four criteria.

Table A1.

| Type of Support | % based on number of words2 | % based on number of quotes2 |

|---|---|---|

| Informational Support | 61.4% | 57.1% |

| Emotional Support | 36.3% | 38.8% |

| Instrumental Support | 2.3% | 4.1% |

Support was categorized into Informational Support, Emotional Support, and Instrumental Support based on prior research with similar categories: Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x

ATLAS.ti was initially used to code each of the side discussions (A.C.S, A.R.K, C.S.). Analyst consensus was first reached on categories of support to be used to sub-code the side discussions (A.C.S., A.R.K., R.M.), which were then sub-coded by R.M. by category of support. Percentage of side discussions by support category were calculated in two ways: percent of side discussions that fell into each category by number of overall words in all side discussions and percent of side discussions that fell into each category by number of participant quotes in all side discussions. Support category coding by R.M was verified by A.C.S.

Table A2.

| Type of Support and Topic | % based on number of words | % based on number of quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Informational Support | ||

| Device use | 32.3 | 30.8 |

| Blood glucose management | 8.9 | 10.5 |

| Supply management | 10.4 | 8.3 |

| Cost/insurance | 6.7 | 7.6 |

| Navigating activities of daily living with devices | 7.1 | 5.4 |

| Education | 4.0 | 4.4 |

| Specific considerations for age and type of diabetes | 5.1 | 4.4 |

| Instrumental Support | ||

| Demonstration of device functions | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| Emotional Support | ||

| Storytelling and validating experiences | 23.9 | 25.7 |

Support was categorized into Informational Support, Emotional Support, and Instrumental Support based on prior research with similar categories: Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x

ATLAS.ti was initially used to code each of the side discussions (A.C.S, A.R.K, C.S.). Analyst consensus was first reached on categories of support to be used to sub-code the side discussions (A.C.S., A.R.K., R.M.), which were then sub-coded by R.M. by category of support. Side discussions were then inductively coded based on topics of discussion. Code-document tables in ATLAS.ti were used to calculate percentage of words or quotes that corresponded to each topic.

Table A3.

Suggestions for Topics Covered in Provider Facilitated Older Adult Support Groups

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Type 1 Diabetes and Aging | A general overview on the effect that aging has on type 1 diabetes management. Older adults share of experiences, challenges and strategies to manage changes with age. |

| Device Placement | Challenges and best practices for device placement using older adult models, including considerations for different types of age-related impairments. In addition to advice about where to place sensors, address how to deal with bleeding or keeping sensors on. |

| Integration of CGM into Lifestyle | Tips for using CGM to suit activities of daily living, including different alert options for sleep and social situations, other technology available to integrate with CGM, data sharing options, planning for routine medical procedures, navigating travel (e.g., supply planning, using security checkpoints in airports). |

| How to Interpret and Respond to CGM | How to interpret data output, including different error messages, and suggestions for how to respond based on data output and activity. |

| Diabetes Supply Management | Strategies for ensuring there are enough supplies to last, balancing cost/insurance issues, rules and paperwork, and the utility of customer support to address barriers. Include overview of current Medicare rules regarding devices and supplies. |

| Hypoglycemia Management | Older adults discuss various strategies they have developed to prevent and treat low blood sugars across activities of daily living. |

| Advocating for Oneself in Different Spaces | Experiences as older adult with type 1 diabetes in the workplace, at clinician offices, in the hospital (e.g., with inpatient health care team to maintain glycemic management once admitted), and other public places. Older adults share ways of managing challenges. |

| Caregiver Roles | Older adults discuss various ways that caregivers challenge and benefit their diabetes management. Separate informational and behavioral groups include caregiver-older adult dyads to develop dyad-specific support activities that minimize interpersonal conflict and the diminution of older adult autonomy. |

Footnotes

Disclosures

Duality of Interest Disclosure

Conflict of Interest

RSW participated in multicenter clinical trials through her institution, sponsored by Insulet, Medtronic, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and has used donated DexCom CGMs in projects sponsored by NIH and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. The other authors have no disclosures to report. REP reports consulting fees from Bayer AG, Corcept Therapeutics Incorporated, Dexcom, Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co., Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Scohia Pharma Inc., and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and grants/research support from Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co., Janssen, Metavention, Novo Nordisk, Poxel SA, and Sanofi. All funds are paid directly to Dr. Pratley’s employer, AdventHealth, a nonprofit organization that supports education and research.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, ACS.

References

- 1.Laiteerapong N, Huang ES. Diabetes in Older Adults. In: Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al. , eds. Diabetes in America. 3rd ed. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); 2018. Accessed November 8, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567980/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeCarlo K, Aleppo G. Perspectives on the Barriers and Benefits of Diabetes Technology in Older Adults with Diabetes in the USA. US Endocrinology. 2021;17(1):1–8. Published online November 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.touchendocrinology.com/diabetes/journal-articles/perspectives-on-the-barriers-and-benefits-of-diabetes-technology-in-older-adults-with-diabetes-in-the-usa/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munshi M, Slyne C, Davis D, et al. Use of Technology in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Clinical Characteristics and Glycemic Metrics. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(1):1–9. Doi: 10.1089/dia.2021.0246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruedy KJ, Parkin CG, Riddlesworth TD, Graham C. Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Older Adults With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Using Multiple Daily Injections of Insulin: Results From the DIAMOND Trial. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(6):1138–1146. doi: 10.1177/1932296817704445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratley RE, Kanapka LG, Rickels MR, et al. Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring on Hypoglycemia in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2397–2406. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munshi MN, Meneilly GS, Mañas LR, et al. Diabetes in Aging: Pathways for Developing the Evidence-Base for Clinical Guidance. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):855–867. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30230-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malterud K Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazen A, Barg FK, Takeshita J. Research Techniques Made Simple: An Introduction to Qualitative Research. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(2):241–247.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roller M, Lavrakas P. Applied Qualitative Research Design: A Total Quality Framework Approach. Guilford Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovmand PS, Andersen DF, Rouwette E, Richardson GP, Rux K, Calhoun A. Group Model-Building ‘Scripts’ as a Collaborative Planning Tool. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 2012;29(2):179–193. doi: 10.1002/sres.2105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apostolopoulos Y, Lemke MK, Barry AE, Lich KH. Moving alcohol prevention research forward—Part I: introducing a complex systems paradigm. Addiction. 2018;113(2):353–362. doi: 10.1111/add.13955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cilenti D, Issel M, Wells R, Link S, Lich KH. System Dynamics Approaches and Collective Action for Community Health: An Integrative Review. Am J of Community Psychol. 2019;63(3–4):527–545. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen DF, Richardson GP. Scripts for group model building. System Dynamics Review. 1997;13(2):107–129. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahkoska AR, Smith C, Young LA, Lich KH. Use of Systems Thinking and Group Model Building Methods to Understand Patterns of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Use Among Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. medRxiv. 8 August 2022. [preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2022.08.04.22278427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS.ti 22 Windows/Mac/Web]. (2022). Retrieved from https://atlasti.com

- 17.R Core Team. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 3.6.0) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swain J, King B. Using Informal Conversations in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2022;21. doi: 10.1177/16094069221085056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahkoska AR, Smith C, Thambuluru S, Weinstein J, Batsis JA, Pratley R, Weinstock RS, Young LA, Hassmiller Lich K. “Nothing is linear”: Characterizing the Determinants and Dynamics of CGM Use in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes through Participatory System Dynamics Modeling. Under Review. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewinski AA, Anderson RA, Vorderstrasse AA, Fisher EB, Pan W, Johnson CM. Type 2 Diabetes Education and Support in a Virtual Environment: A Secondary Analysis of Synchronously Exchanged Social Interaction and Support. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e61. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatwin H, Broadley M, Jensen MV, et al. ‘Never again will I be carefree’: a qualitative study of the impact of hypoglycemia on quality of life among adults with type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e002322. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Divan V, Greenfield M, Morley CP, Weinstock RS. Perceived Burdens and Benefits Associated With Continuous Glucose Monitor Use in Type 1 Diabetes Across the Lifespan. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;16(1):88–96. doi: 10.1177/1932296820978769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vloemans AF, van Beers C a. J, de Wit M, et al. Keeping safe. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in persons with Type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia: a qualitative study. Diabet Med. 2017;34(10):1470–1476. doi: 10.1111/dme.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litchman ML, Allen NA, Colicchio VD, et al. A qualitative analysis of real-time continuous glucose monitoring data sharing with care partners: to share or not to share? Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2018;20(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritholz M, Beste M, Edwards S, Beverly E, Atakov‐Castillo A, Wolpert H. Impact of continuous glucose monitoring on diabetes management and marital relationships of adults with type 1 diabetes and their spouses: a qualitative study. Diabetic Medicine. 2014;31(1):47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz R, Eden J, Adults C on FC for O, Services B on HC, Division H and M, National Academies of Sciences E. Family Caregiving Roles and Impacts. National Academies Press (US); 2016. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396398/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz R, Eden J, Adults C on FC for O, Services B on HC, Division H and M, National Academies of Sciences E. Family Caregivers’ Interactions with Health Care and Long-Term Services and Supports. National Academies Press (US); 2016. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396396/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litchman ML, Allen NA. Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring Facilitates Feelings of Safety in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A Qualitative Study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(5):988–995. doi: 10.1177/1932296817702657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boen F, Pelssers J, Scheerder J, et al. Does Social Capital Benefit Older Adults’ Health and Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Physical Activity. J Aging Health. 2020;32(7–8):688–697. doi: 10.1177/0898264319848638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagaert S, Snaphaan T, Vyncke V, Hardyns W, Pauwels LJR, Willems S. A Multilevel Perspective on the Health Effect of Social Capital: Evidence for the Relative Importance of Individual Social Capital over Neighborhood Social Capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1526. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gale CR, Westbury L, Cooper C. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 2018;47(3):392–397. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee ML, Yano EM, Wang M, Simon BF, Rubenstein LV. . What Patient Population Does Visit-Based Sampling in Primary Care Settings Represent?. Medical Care. 2002; 40 (9): 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, ACS.