Abstract

Objective

This study aimed at developing and validating a web application on hypertension management called the D-PATH website.

Methods

The website development involved three stages: content analysis, web development, and validation. The model of Internet Intervention was used to guide the development of the website, in addition to other learning and multimedia theories. The content was developed based on literature reviews and clinical guidelines on hypertension. Then, thirteen experts evaluated the website using Fuzzy Delphi Technique.

Results

The website was successfully developed and contains six learning units. Thirteen experts rated the website based on content themes, presentation, interactivity, and instructional strategies. All experts reached a consensus that the web is acceptable to be used for nutrition education intervention.

Conclusion

D-PATH is a valid web-based educational tool ready to be used to help disseminate information on dietary and physical activity to manage hypertension. This web application was suitable for sharing information on dietary and physical activity recommendations for hypertension patients.

Keywords: Hypertension < Disease, dietary management, nutrition education, Physical Activity < Lifestyle, web-application

Introduction

The Nutrition Research Priorities in Malaysia for the 12th Malaysia Plan (2021–2025) and the World Health Organisation's (WHO) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) highlight that hypertension is one of the most critical areas for research as hypertension contributes significantly to the increase in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).1,2 Hypertension (HTN) has become a worldwide public health concern and the primary cause of morbidity and mortality.3,4 It poses a considerable risk for dementia, chronic kidney ailments, ischemic heart, cardiovascular ailments, and stroke.5 Besides, the WHO projects that 1.28 billion people aged 30 to 79 suffer from hypertension, with the majority (66%) living in low- and middle-income nations.5 Based on the Malaysia National Health and Morbidity Surveys (NHMS) in 2019, the prevalence of hypertension was reported at 32.6% in 2011, 30.3% in 2015 and 30% in 2019.6 Although the percentage has plateaued, there has been an increase in the number of patients with hypertension due to the growing number of populations. According to the 2019 NHMS report, Malay ethnicity had the highest prevalence of known and unknown hypertension (34.8%), followed by Indians (30.3%) and Chinese (27.6%). Moreover, Malay has the most significant rate of hypertension, estimated at 3 million people. On the other hand, the number of patients with hypertension who received medical treatment increased from 78.9% in 2006 to 83.2% in 2015.6 However, despite the higher proportions of patients receiving treatment, the control of hypertension remained poor, below 40%.7 Comparing blood pressure control between ethnicities, 33.2% of Malays had poor control of hypertension as compared to Chinese (46.8%) and Indians (40.8%). Missed medical appointments, low education level, sedentary lifestyle and poor dietary habits are contributing factors to uncontrolled hypertension.8,9 For example, excess sodium intake is correlated with hypertension in humans.10 Lifestyle changes are the first line of treatment and are one of the key tactics to reduce hypertension, according to clinical recommendations for its management.11–16 Lifestyle modifications such as dietary intake adjustment, increased physical activity level and smoking cessation have been proven effective in controlling blood pressure.13,16

The digital era has seen extensive adoption and offers individuals several ways to access health-related information. Numerous research works have been done to evaluate patients’ information-seeking behaviour (ISB) using interpersonal or online resources.17–19 Many patients access much information using information, communication and technologies (ICTs) platforms, such as websites, social media or health applications.20 A recent study found that most patients use online health information such as the Internet, social media or online courses, compared to the interpersonal approach.21 The use of health information on the Internet could play an important role in effectively improving one's self-efficacy and self-management skills. For example, a previous study showed the potential use of online guided self-determination programs to improve diabetes self-management in young adults.22

Various websites used for nutrition intervention show positive results in promoting behavioural changes. For example, many websites were used to improve the clinical outcomes in hypertension management, such as lowering and maintaining blood pressure to normal.23–26 Websites have become alternative and supporting educational tools for health education. As against in-person delivery, previous study found that Internet-based diet and physical activity instructions resulted in positive and similar nutrition-related improvements and offered the user effective, interactive, and customised content.27,28 Additionally, wherever physical contact is to be minimised, particularly in clinical settings where the transmission of contagious ailments, especially COVID-19, rises, interventions utilising ICTs should be given priority.29

Given the positive impacts of websites in improving health literacy and patient self-efficacy in controlling hypertension, this study aimed to develop and validate a web-based application for diet and physical activity management to control hypertension for the Malay population, also known as D-PATH (Dietary and Physical Activity Management to Control Hypertension) website. The validation of this website offers valuable insights into experts’ assessments of a newly developed platform that seamlessly integrates instructional design with multiple theories, including those related to learning and multimedia. Apart from this, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted patients to access health information through an online platform, justified the importance of creating a hypertension management website. D-PATH will serve as an educational tool for healthcare practitioners in government health institutions, enabling them to educate patients about hypertension management. Patients can independently utilise D-PATH anytime and anywhere, using their preferred devices.

Materials and methods

This study is of a cross-sectional nature, and the development of D-PATH followed the Design and Development Research (DDR) method. DDR research allows researchers to assess theories, models, and frameworks and validate practical applications.30

Development of D-PATH web-based application

D-PATH was created as a free online educational tool for patients with hypertension. The website is maintained by the development team's administrator and is overseen by a registered dietitian. The development of the D-PATH website involved three stages: (1) content analysis, (2) designing and developing the content and website, and (3) expert validation. The analysis of the literature involved several experts from multidisciplinary areas, such as medical doctor, dietitians, nutritionist, and psychologist. A systemic review of the literature was conducted to identify the preferences and effectiveness of web elements for nutrition education intervention programmes, such as content delivery method, use of notification, and interactivity and was published elsewhere.21 Additionally, several clinical guidelines were analysed to ensure the content was based on clinical evidence and up to date. Next, the content of the website was modified to suit the ethnicity of the targeted population in this study, which is Malay patients with hypertension aged 18 and above.

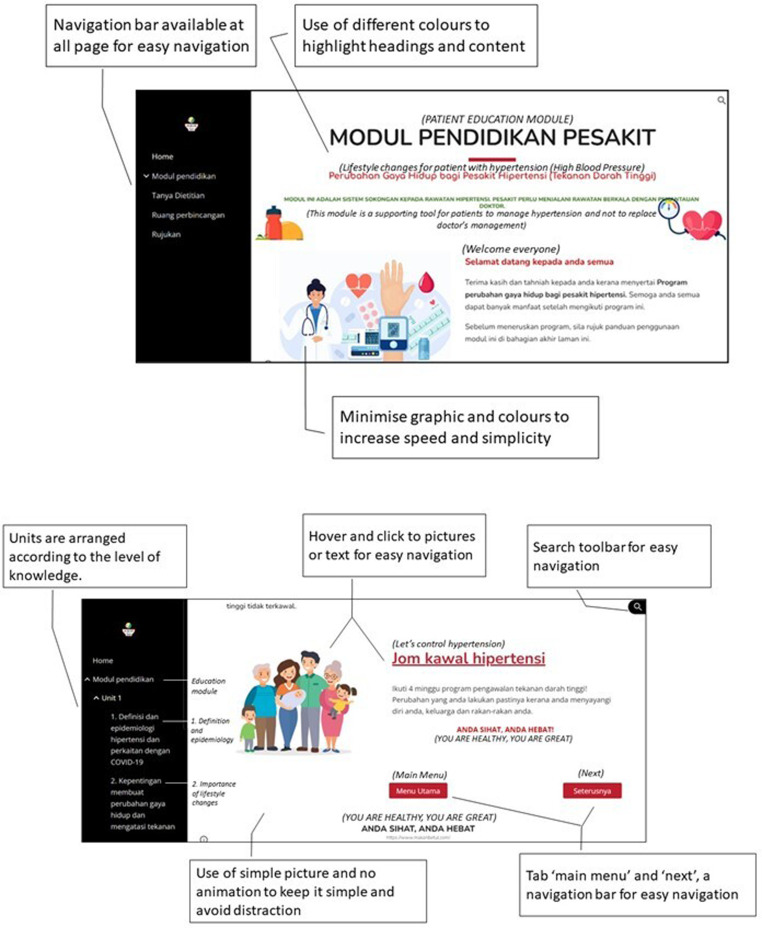

After completing the first step, the design and development of the website was done. D-PATH website was based on the Model of Internet Intervention to ensure it meets the objective of the website.28 This model assists in the development of Internet education or interventions, as well as in promoting behavioural changes. As such, the delivery of the content of the website integrated several multimedia components such as infographics and videos. Table 1 shows the application of the Model of Internet Intervention on the web. Other than that, various models and theories, such as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)31 and Flow Theory32 were adopted to design and develop the website. UTAUT seeks to clarify user intentions regarding the utilisation of an information system and its subsequent usage behaviour. This theory posits the existence of four fundamental constructs: (1) performance expectancy, (2) effort expectancy, (3) social influence, and (4) facilitating conditions. Table 2 shows the application of the UTAUT model on the web. Flow theory was used because learners can achieve optimal learning outcomes when engaging in tasks that balance skill and challenge levels, coupled with a person's interest, sense of control, and intense focus. Figure 1 shows the application of Flow theory in the web. Moreover, the website content, such as educational videos, was designed and developed using the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning.33 The use of fonts, colours, user interface, and content arrangement was done carefully based on the theories and models.

Table 1.

Application of the model of internet intervention in the D-PATH website.

| No | Characteristics | Application |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Appearance |

|

| 2 | Behavioural/ prescriptions | Users have been informed about the user manual on the web's homepage. New users must complete a registration form and agree to follow the guidelines to complete the module. Users are expected to complete the module in four weeks. In addition, users were informed about the profiles of the website administrator. |

| 3 | Burdens | The online content was divided into six parts to allow users to browse the content in stages to minimise the burden on users. The materials were presented in the form of videos and infographics. |

| 4 | Content | The information was supported by evidence. It was developed using a review of the literature and clinical guidelines. All references were listed on the website. |

| 5 | Delivery | The mode of delivery of the content was using videos, infographics, and text. |

| 6 | Message | The message was conveyed in layman's words. Medical jargon was avoided in the text, video, and infographics. Instead, the website's text was written in a conversational tone. |

| 7 | Participation | In addition to using a conversational tone to encourage users to participate, a chat room and forum have been set up to facilitate interaction between users and the administrator. In addition, the administrator will notify users once a week to ensure they continue using the website. Finally, users must complete the activities at the end of each unit. |

| 8 | Assessment | During the online registration process, a personality assessment concentrating on the stages of change was performed. This would allow the administrator to determine the individuals’ willingness to change. |

Table 2.

Application of the UTAUT model in the D-PATH website.

| Predictors | Definition | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | The degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help them to attain gains in job performance. | Users have been informed that the website contains information to help them better control their disease. The information was broken down into small parts and divided into sections to reduce the user's cognitive load. |

| Effort expectancy | The degree of ease associated with the use of the system. | Users do not have to log in and can go directly to the homepage and follow the instructions. The navigation bar and buttons are provided on each page. |

| Social Influence | The degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe they should use the new system. | Users have been informed that the website is accessible to everyone, especially hypertensive patients and their family members. In addition, the website provides a space for group discussion where users can interact and socialise. |

| Facilitating conditions | The degree to which an individual believes that an organisation's technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system. | Users have been given a contact number for user support. Support is available 24 h a day. |

Figure 1.

Application of flow theory in the D-PATH website.

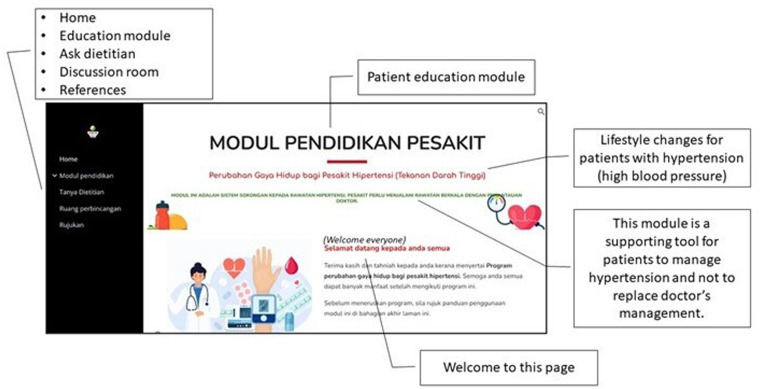

Regarding content development, the transtheoretical model of change (TTM) was used to structure the content on the web, including the pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance stage.36 TTM was used considering the heterogeneity stage of change among the users, as the web is opened to the public. In addition, the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCT)37 was also used to identify the specific behavioural change in each learning unit on the web. The web consists of six units: (1) general information about hypertension, (2) management of sodium intake, (3) Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and recommendation for fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, (4) fat and alcohol, (5) physical activity and exercise, (6) shopping tips. These units were created based on the recommendations from multiple clinical guidelines for the management of hypertension.14–16,38,39 These topics are important for patients to control their blood pressure. Figure 2 shows the user interface (UI) of the web. Additionally, activities were provided at the end of every unit to ensure users engaged with the web.

Figure 2.

User interface of the D-PATH website.

Apart from the behavioural change theories, as mentioned before, the web also integrates Bloom's taxonomy40 and a revised version of Nine Gagne's Events of Instruction.41 D-PATH uses the Malay language to ensure the patients can comprehend and apply the information from the web. In addition, Malay was chosen because it is the national language of Malaysia, and every Malaysian can understand it.

Videos have been proven effective in disseminating medical information and promoting behavioural changes.42,43 Therefore, 48 videos were embedded in the web. 9 videos explain the general information about hypertension, 14 videos on salt and sodium, 5 videos on fruits, vegetables and whole grains, 5 videos on fat and alcohol, 3 videos on physical activity and exercise, and 12 videos on shopping tips. Other than that, infographics were also used in every unit.

Validation of D-PATH web-based application

The last stage in the D-PATH development was the validation. The importance of the validation stage was to ensure the web is valid and ready to be used for nutrition education intervention. A purposive sampling was employed to recruit the experts. Researchers requested authentic feedback to enhance the website and its benefits for patients, emphasising that the review process remains free from any organisational influence. A panel of interdisciplinary health experts with experience in managing hypertension was invited to evaluate the module. The inclusion criteria for the experts were at least five years of experience in the field44 and high academic qualifications.45 A total of 13 experts, including 1 senior lecturer with a dietetics background, eleven dietitians, one specialist in family medicine and one clinical psychologist, were selected. The recruited number of experts is sufficient since it is more than the recommended number of 10.46,47 These experts evaluated the web, and the evaluation process was conducted face-to-face. All experts received the web link by email one week before the evaluation day to ensure sufficient time to go through the web.

Fuzzy Delphi Technique (FDT) was used to assess the website. The FDT presents numerous advantages, such as the capacity to solicit expert opinions, establish consensus and engage with research subjects without constraints related to time and location. The choice of this technique follows the aim of the study to obtain experts’ agreement on the content and elements used in the web application. The items in the questionnaire were developed based on the literature review and the researcher's experience.48,49 The completed questionnaire was given to four experts for face validation. Specifically, the questionnaire utilised a seven-point scale,50 as shown in Table 3. The questionnaire was distributed to 13 experts for module evaluation. The questionnaire has four sections: section A: Themes for the content, section B: Presentation interface design, section C: Interactivity interface design and Section D: Instructional Strategies.

Table 3.

Seven-point-scale for fuzzy Delphi technique.

| Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extremely strongly disagree | (0.0,0.0,0.1) |

| 2 | Strongly disagree | (0.0,0.1,0.3) |

| 3 | Disagree | (0.1,0.3,0.5) |

| 4 | Moderately agree | (0.3,0.5,0.7) |

| 5 | Agree | (0.5,0.7,0.9) |

| 6 | Strongly agree | (0.7,0.9,1.0) |

| 7 | Extremely strongly agree | (0.9,1.0,1.0) |

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was analysed systematically using Microsoft Excel software.51 The prerequisites for the Fuzzy Delphi technique are the Triangular Fuzzy Number and the Defuzzification Process. The Triangular Fuzzy Number must meet the two terms: first, the value of Threshold (d) ≤ 0.2, and second, involve a percentage of expert agreement. The expert agreement is attained for the first term when the resulting value is smaller or equal to 0.2.52 The following formula was used to determine the value:

The second term for the Triangular Fuzzy Number involves a percentage of expert agreement. The traditional Delphi technique states that it is acceptable if the expert group agreement exceeds 75%.53 On the other hand, the Defuzzification Process is the determination of the fuzzy (A) score value based on the α-cut value of 0.5.54,55 If the fuzzy score value (A) is equal to or greater than 0.5, then the measured item is accepted. Meanwhile, the measured item is rejected if A is less than 0.5. The determination of fuzzy (A) score value was calculated based on the following formula:

The triangular fuzzy numbers were established sequentially upon evaluating the collected values of the themes, sub-themes, presentation interface design, interactivity interface design, and instructional strategies.

Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Socio-demographic information

Table 4 presents the experts’ socio-demographic characteristics. Most experts were females (77%) with degrees (77%). The mean working experience was 12.5 years. The four professions involved in this study were dietitians (77%), a senior lecturer, a family medicine specialist, and a clinical psychologist.

Table 4.

Socio-demographic characteristics of experts (n = 13).

| Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.6 (3.3) | |

| Sex | ||

| • Male | 3 (25.1) | |

| • Female | 10 (76.9) | |

| Education level | ||

| • Degree | 10 (76.9) | |

| • Master | 2 (15.4) | |

| • PhD | 1 (7.7) | |

| Working experience (year) | 12.5 (5.6) | |

| Profession | ||

| • Dietitian | 10 (76.9) | |

| • Senior lecturer | 1 (7.7) | |

| • Family Medicine Specialist | 1 (7.7) | |

| • Clinical Psychologist | 1 (7.7) | |

Analysis of the themes for the content

Based on Table 5, all experts accepted the themes for the module's content. All items recorded a threshold (d) value ≤ 0.2. The experts’ agreement revealed that all items scored > 75%, and all defuzzification values for items exceeded the value of α – cut = 0.5. The items were positioned according to the expert agreement.

Table 5.

Analysis of the themes for the D-PATH website (n = 13).

| Item | Name | Condition of Triangular Fuzzy Number | Condition of Defuzzification Process | Expert consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The threshold value, d | Expert group consensus (%) | Fuzzy score (A) | |||

| 1 | General information about hypertension | 0.040 | 100.00 | 0.951 | Accepted |

| 2 | Management of Sodium Intake | 0.065 | 100.00 | 0.936 | Accepted |

| 3 | DASH Diet and recommendation for Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains | 0.082 | 92.30 | 0.931 | Accepted |

| 4 | Fat and Alcohol | 0.040 | 100.00 | 0.951 | Accepted |

| 5 | Physical Activity and Exercise | 0.040 | 100.00 | 0.951 | Accepted |

| 6 | Shopping Tips | 0.095 | 92.31 | 0.915 | Accepted |

Analysis of the presentation interface design

As depicted in Table 6, all experts accepted the presentation interface design of the website. Most items gained 100% consensus from the experts.

Table 6.

Analysis of the presentation interface design (n = 13).

| Item | Name | Condition of Triangular Fuzzy Number | Condition of Defuzzification Process | Expert consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The threshold value, d | Expert group consensus (%) | Fuzzy score (A) | |||

| 1 | The screen design of the website is simple, attractive and consistent. | 0.066 | 100.00 | 0.877 | Accepted |

| 2 | The use of text is straightforward to read. | 0.117 | 100.00 | 0.859 | Accepted |

| 3 | The integration of graphics, images, colours and icon buttons is attractive and appropriate. | 0.095 | 100.00 | 0.836 | Accepted |

| 4 | The arrangement and structure of the content are organised and engaging. | 0.102 | 100.00 | 0.844 | Accepted |

| 5 | The image is realistic to apply the information. | 0.072 | 100.00 | 0.905 | Accepted |

| 6 | The graphic elements are used to convey information. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.913 | Accepted |

| 7 | The video elements are used to convey information. | 0.072 | 100.00 | 0.928 | Accepted |

| 8 | The response time on the website is appropriate. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.913 | Accepted |

| 9 | Has a smooth transition from one display to another. | 0.205 | 84.62 | 0.833 | Accepted |

| 10 | The language used is appropriate and easy to understand. | 0.164 | 92.31 | 0.841 | Accepted |

| 11 | No technical glitches occurred during the application and presentation. | 0.078 | 100.00 | 0.885 | Accepted |

| 12 | The navigation icons are user-friendly. | 0.150 | 92.31 | 0.844 | Accepted |

| 13 | The primary menu system is simple and easy to use. | 0.105 | 100.00 | 0.879 | Accepted |

Analysis of the interactivity interface design

Based on Table 7, most items accept the website's presentation interface design. Experts rejected items 3 and 10, with the score of 38.5% and 23.8%, respectively. The website did not provide links to other websites or allow users to download all content from the website.

Table 7.

Analysis of the interactivity interface design (n = 13).

| Item | Name | Condition of Triangular Fuzzy Number | Condition of Defuzzification Process | Expert consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The threshold value, d | Expert group consensus (%) | Fuzzy score (A) | |||

| 1 | Encouraging feedback | 0.146 | 92.30 | 0.879 | Accepted |

| 2 | Different forms of feedback (typing answers, clicking options, others.) | 0.163 | 92.30 | 0.859 | Accepted |

| 3 | Provide links to other related websites | 0.400 | 38.50 | 0.708 | Rejected |

| 4 | Scenarios and activities focus on intended achievement in the learning process. | 0.112 | 92.31 | 0.877 | Accepted |

| 5 | Provides a systematic navigation structure to avoid confusion or loss while exploring it | 0.249 | 76.92 | 0.769 | Accepted |

| 6 | Provides an easy-to-follow direction for the presentation of information | 0.096 | 92.31 | 0.908 | Accepted |

| 7 | Provides more than one form of information access | 0.117 | 100.00 | 0.895 | Accepted |

| 8 | Eases the access to information needed | 0.105 | 100.00 | 0.879 | Accepted |

| 9 | Provides opportunities to interact through Web 2.0 applications (blog, interactive online wall, interactive whiteboard, forum, WhatsApp group and Facebook) | 0.123 | 92.31 | 0.892 | Accepted |

| 10 | Provides facilities to download the material provided | 0.403 | 23.08 | 0.554 | Rejected |

| 11 | Provides online evaluation or online reinforcement activities | 0.150 | 92.31 | 0.844 | Accepted |

| 12 | Provides user guides to facilitate navigation | 0.137 | 92.31 | 0.828 | Accepted |

Analysis of the instructional strategies

As highlighted in Table 8, all experts accepted the instructional strategies of the website. Most items gained 100% consensus from the experts.

Table 8.

Analysis of the instructional strategies (n = 13).

| Item | Name | Condition of Triangular Fuzzy Number | Condition of Defuzzification Process | Expert consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The threshold value, d | Expert group consensus (%) | Fuzzy score (A) | |||

| 1 | This module uses suitable theories and models to increase knowledge. | 0.065 | 100.00 | 0.936 | Accepted |

| 2 | This module uses suitable theories and models to promote behavioural changes. | 0.072 | 100.00 | 0.928 | Accepted |

| 3 | This module uses suitable theories and models for website development. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.921 | Accepted |

| 4 | This module uses suitable learning activities. | 0.173 | 84.62 | 0.856 | Accepted |

| 5 | This module clearly specified the objectives of learning. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.921 | Accepted |

| 6 | This module has an appropriate sequence of learning processes. | 0.094 | 100.00 | 0.900 | Accepted |

| 7 | This module uses suitable media elements (graphics, video). | 0.072 | 100.00 | 0.928 | Accepted |

| 8 | This module supports learners in recalling prior knowledge. | 0.078 | 100.00 | 0.885 | Accepted |

| 9 | This module provides new learning stimuli. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.913 | Accepted |

| 10 | This module provides guidance. | 0.076 | 100.00 | 0.921 | Accepted |

| 11 | This module encourages practice. | 0.117 | 100.00 | 0.895 | Accepted |

| 12 | This module allows users and facilitators to provide feedback. | 0.095 | 100.00 | 0.872 | |

| 13 | The duration of this module is sufficient. | 0.169 | 92.31 | 0.831 | Accepted |

Discussion

The web was developed in ‘Bahasa Malaysia’, which is the national language of Malaysia and comprises six units. The content was delivered through notes, infographics, videos and online activities. Numerous behavioural theories can be used to promote behavioural change in the target population. In this study, the transtheoretical model36 and the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCT)37 were used to develop the module. A systematic review suggested using the TTM for digital interventions as it is effective in promoting behaviour change.56 The TTM is appropriate for use in this study because it specifies the mediators to be used at each stage of change. Since the patients in this study are at different stages of readiness for change, the TTM model was the most appropriate. The sequence of the module was set to promote change in the participants from the pre-contemplation stage to the maintenance stage. The taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCT) was also used in the development of the module. The BCT specifies the mode of delivery and standardises the intervention protocol in this study. BCT has also been shown to be effective in many studies.57–59 The use of BCT is beneficial for this study because other researchers can replicate the intervention protocol of the current study. In addition, the content of the module was designed to be suitable for adult learning.60 Apart from the theories of behaviour change, the instructional design40,61 was used in the development of the module. The revised version of Gagne's nine events of instruction was used because it is appropriate for health behaviour change.41 Bloom's taxonomy was used to ensure that the level of information is arranged from a low to a higher level of difficulty. In addition, the taxonomy indicates the learning objective in each unit of the web.

The website in this study is designed for an educational intervention. This means users are expected to learn, practise, or adjust their behaviour based on the recommendations. Therefore, the model of Internet intervention was used to guide the development of the website.28 The mode of delivery was selected and coordinated for online usage. For example, the content of the module was delivered using infographics, videos and online activities. The cognitive theory of multimedia learning,62 cognitive load theory,63 flow theory32 and the revised version of Nine Gagne's Event of Instruction41 were carefully considered in developing the website, videos and infographics. In addition, the noble concept of edutainment was used in developing the videos.

The web was evaluated using the FDT. This method requires experts to evaluate the content and the website. The FDT method determined the agreement between the content of the module and the website to be used for the educational intervention to control hypertension. FDT is a revised version of the Delphi method to get consensus from experts on specific issues or topics. The Delphi method requires several rounds of discussion among experts to reach an agreement, but the ambiguity and uncertainty of expert opinions persisted.64 Therefore, to overcome the methodological limitations of the Delphi method, Murray introduced the FDT in 1985.65 FDT was used in this study since several rounds of discussion between the researcher and the experts are not required, thus equipped with the capacity to minimise the risk of information loss and avoid any ambiguity in the data. It also allows the experts to express their opinions about the research topic.66 The experts agreed to accept the content of the module based on the FDT analysis. The acceptance of the content could be linked to the selection of the content according to the recommendations of the clinical guidelines for managing hypertension. In terms of the website's presentation interface, user interface interactivity and instructional strategies, all experts agreed on all items except that the website provides links to other related websites and facilities to download the provided material. The website did not include these features to avoid redirecting users to another website. In addition, the materials, especially the videos, cannot be downloaded as YouTube policies do not allow downloading from the website. However, users can still download the infographics from the websites. Experts commented on the content and the web interface and suggested improvements. All feedback was considered, and measures were taken to improve the website.

The main strength of this study is the novelty of the website development foundation. This website incorporated the Transtheoretical Model theory of behaviour change and the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques for reporting, learning and multimedia theories. The development of the website started by creating a module with digital content such as videos and infographics. Furthermore, the module was structured using Gagne's Events of Instruction and Bloom's taxonomy. Finally, the website was developed based on a specific instructional design for multimedia learning. An internet intervention model was also used to identify important components of the website. In addition, the UTAUT model, cognitive theory of multimedia learning, cognitive load theory and flow theory were employed to develop the website carefully. The use of multiple theories in the development of the website makes it unique and novel compared to other online websites. Secondly, the content of the website is supported by scientific evidence. Experts such as dietitians, a family medicine specialist and a clinical psychologist were involved in validating the website. References are also provided on the website to increase the trustworthiness of the website. Also, the users can read the administrator's profile on the website's home page. Therefore, the users can use the website with confidence. The use of FDT is also one of the strengths of this study because it quantified the experts’ consensus of the web application.

The major limitation of the website is the language. The content of the website was developed in Malay, which limits users to those who understand Malay. Apart from this, scientific knowledge may change over time. Therefore, there is a possibility that the content may be outdated. However, the content can be updated from time to time to ensure that it is always relevant. With regard to methodology, the reliability of the questionnaires was not assessed. It is recommended that the reliability of the questionnaire be assessed, and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient be reported for each section. This paper centres its attention on the development of D-PATH, it is suggested that the web shall be further evaluated on its feasibility among hypertension patients. The assessment from patients will shed light on aspects like acceptance, satisfaction, and alterations in knowledge, attitude, and behaviour following their interaction with the D-PATH.

Conclusions

This study showed that D-PATH was valid and ready to be used for nutrition education intervention among patients with hypertension. The web was modified and updated according to the comments from the experts. The use of multiple theories and models make this web distinct and unique from other available online web application. In short, D-PATH is a valid web-based educational tool ready to be used to help disseminate information on dietary and physical activity to manage hypertension. This web application was suitable to share information on dietary and physical activity recommendations for patients with hypertension. However, the web is not to replace medical intervention but can be a helpful tool to complement care for patients with hypertension.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241242661 for Development and validation of D-PATH website to improve hypertension management among hypertensive patients in Malaysia by Mohd Ramadan Ab Hamid, Siti Sabariah Buhari, Harrinni Md Noor, Nurul ‘Ain Azizan, Khasnur Abd Malek, Ummi Mohlisi Mohd Asmawi and Norazmir Md Nor in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge team support from the Healthcare Facilities from Universiti Teknologi MARA.

Footnotes

Contributionship: Conceptualisation, M.R.A.H, S.S.B, and H.M.N.; methodology, M.R.A.H, S.S.B, H.M.N, N.A.A and N.M.N; validation, M.R.A.H and H.M.N.; formal analysis, M.R.A.H; investigation, M.R.A.H. and K.M.N.; resources, M.R.A.H, N.M.N and U.M.MA; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.A.H, S.S.B, H.M.N, N.A.A, N.M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.R.A.H; supervision, S.S.B, H.M.N, N.A.A and N.M.N.; funding acquisition, N.M.N and U.M.MA All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration principles and was approved by the UiTM Research Ethics Committee, 600-IRMI (5/1/6). Written consent was obtained from the participants.

Funding: This research has been funded by Universiti Teknologi MARA under DUCS 3.0 Research Grant no: 600-UITMSEL (PI. 5/4) (015/2021).

Universiti Teknologi MARA, (grant number DUCS 3.0 Grant No: 600-UITMSEL (PI. 5/4) (015/2021).

ORCID iD: Mohd Ramadan Ab Hamid https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1464-3210

Norazmir Md Nor https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4594-4115

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Guarantor: MRAH

References

- 1.Ministry of Health Malaysia. Nutrition Research Priorities in Malaysia for 12th Malaysia Plan (2021-2025). In: Nutrition Division MoHM, 2020, (ed.). Putrajaya: Technical Working Group on Nutrition Research, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: Fact Sheet on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Health Targets, https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2017-2381-42136-58046 (2021, accessed 12 December 2022 2021).

- 3.World Health Organization. Hypertension, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (2021, accessed 29 October 2022 2022).

- 4.Brouwers S, Sudano I, Kokubo Y, et al. Arterial hypertension. Lancet 2021; 398: 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, et al. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021; 18: 785–802. 20210528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: Vol. I: NCDs – Non-Communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and other Health Problems, https://iptk.moh.gov.my/images/technical_report/2020/4_Infographic_Booklet_NHMS_2019_-_English.pdf (2019, accessed June 6, 2021 2021).

- 7.Abdul-Razak S, Daher AM, Ramli AS, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, control and socio demographic determinants of hypertension in Malaysian adults. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 351. 2016/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meelab S, Bunupuradah I, Suttiruang J, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of uncontrolled blood pressure among hypertensive patients in the rural communities in the central areas in Thailand: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0212572. 20190219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AU, Falah SF, Shah SAS, et al. The prevalence and associated risk factors of uncontrolled hypertension amongst antihypertensive medicines taking patients. Pak J Med Health Sci 2022; 16: 833–835. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumer-Harrison C, Breza JM, Sumners C, et al. Sodium intake and disease: another relationship to consider. Nutrients 2023; 15: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Hypertension, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (2021, accessed 2 December 2021).

- 12.Rabi DM, McBrien KA, Sapir-Pichhadze R, et al. Hypertension Canada's 2020 comprehensive guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol 2020; 36: 596–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, et al. The Japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res 2019; 42: 1235–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Working Group on Hypertension CPG. Clinical Practice Guideline on Management of Hypertension, Putrajaya: Ministry of Health, 2018. https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/penerbitan/CPG/MSH%20Hypertension%20CPG%202018%20V3.8%20FA.pdf (2018, accessed August 31, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39: 3021–3104. 2018/08/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: e127–e248. 2017/11/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamid A, Allam FN B, Buhari SB, et al. Health information seeking behaviours during COVID-19 among patients with hypertension in selangor. Environ Behav Proc J 2022; 7: 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dean CA, Geneus CJ, Rice S, et al. Assessing the significance of health information seeking in chronic condition management. Patient Educ Couns 2017; 100: 1519–1526. 20170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e9. 20170119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bitar H, Alismail S. The role of eHealth, telehealth, and telemedicine for chronic disease patients during COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review. Digit Health 2021; 7: 20552076211009396. 2021/05/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baderol Allam FN, Ab Hamid MR, Buhari SS, et al. Web-based dietary and physical activity intervention programs for patients with hypertension: scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e22465. 2021/03/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen B, Wynter K, Hamblin PS, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an online guided self-determination program to improve diabetes self-management in young adults. Digital Health 2023; 9: 20552076231167008. 20230330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris P, et al. Health websites that people can trust – the case of hypertension. Interact Comput 2007; 19: 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muzquiz-Barbera P, Ruiz-Cortes M, Herrero R, et al. The impact of a web-based lifestyle educational program (‘living better’) reintervention on hypertensive overweight or obese patients. Nutrients 2022; 14: 2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen TY, Kao CW, Cheng SM, et al. A web-based self-care program to promote healthy lifestyles and control blood pressure in patients with primary hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh 2022; 54: 678–691. 20220608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lokker C, Jezrawi R, Gabizon I, et al. Feasibility of a web-based platform (trial my app) to efficiently conduct randomized controlled trials of mHealth apps for patients with cardiovascular risk factors: protocol for evaluating an mHealth app for hypertension. JMIR Res Protoc 2021; 10: e26155. 20210201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuenschwander LM, Abbott A, Mobley AR. Comparison of a web-based vs in-person nutrition education program for low-income adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013; 113: 120–126. 20121023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, et al. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med 2009; 38: 18–27. 2009/10/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavero-Redondo I, Saz-Lara A, Sequi-Dominguez I, et al. Comparative effect of eHealth interventions on hypertension management-related outcomes: a network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 124: 104085. 20210905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richey RC, Klein JD. Developmental research methods: creating knowledge from instruction design and develpment practice. J Comput Higher Educ 2005; 16: 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, et al. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q 2003; 27: 25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csikszentmihalyi M. Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: CA: Jossey-Bass, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer RE. Multimedia learning: are we asking the right questions? Educ Psychol 1997; 32: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alnasuan A. Color psychology. Am Res J Humanit Soc Sci 2016; 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu Z, Lou J. Data driven webpage color design. Comput Aided Des 2016; 77: 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12: 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013; 46: 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NICE. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management, www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (2020, accessed August 31, 2020).

- 39.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension 2020; 75(6): 1334–1357. 2020/05/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence (CATE). Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Chicago: University of Illinois Chicago, 2003, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinzie MB. Instructional design strategies for health behavior change. Patient Educ Couns 2005; 56: 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ab Hamid MR, Mohd Yusof NDB, Buhari SS, et al. Development and validation of educational video content, endorsing dietary adjustments among patients diagnosed with hypertension. Int J Health Promot Educ 2021; 7: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamid MR A, Yusof NDB M, Buhari SS. Understandability, actionability and suitability of educational videos on dietary management for hypertension. Health Educ J 2022; 81: 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berliner DC. Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bull Sci Technol Soc 2004; 24: 200–212. 20200715. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gambatese JA, Behm M, Rajendran S. Design’s role in construction accident causality and prevention: perspectives from an expert panel. Saf Sci 2008; 46: 675–691. 20200715. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adler M, Ziglio E. Gazing Into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. London: Jessiva Kingsley Publication, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones H, Twiss BL. Forecasting Technology for Planning Decisions. New York: Macmillan, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skulmoski GJ, Hartman FT, Krahn J. The delphi method for graduate research. J Inf Technol Educ 2007; 6: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag 2004; 42: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohamed Yusoff AF, Hashim A, Muhamad N, et al. Application of fuzzy delphi technique towards designing and developing the elements for the e-PBM PI-poli module. Asian J Univ Educ 2021; 17: 92. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohd Jamil MR, Mat Noh N. Kepelbagaian Metodologi dalam Penyelidikan Reka Bentuk dan Pembangunan. Bangi: Qaisar Prestige Resources, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng C-H, Lin Y. Evaluating the best main battle tank using fuzzy decision theory with linguistic criteria evaluation. Eur J Oper Res 2002; 142: 174–186. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chu HC, Hwang GJ. A delphi-based approach to developing expert systems with the cooperation of multiple experts. Expert Syst Appl 2008; 34: 2826–2840. 20070518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang C-W, Wu C-T. Obtaining a picture of undergraduate education quality: a voice from inside the university. High Educ 2010; 60: 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bodjanova S. Median alpha-levels of a fuzzy number. Fuzzy Sets Syst 2006; 157: 879–891. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hasriani, Sjattar EL, Arafat R. Transtheoretical model on the self-care behavior of hypertension patients: a systematic review. J Health Res 2022; 36: 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, et al. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol 2009; 28: 690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michie S, Hyder N, Walia A, et al. Development of a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in individual behavioural support for smoking cessation. Addict Behav 2011; 36: 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.West R, Walia A, Hyder N, et al. Behavior change techniques used by the English stop smoking services and their associations with short-term quit outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2010; 12: 742–747. 20100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bryan RL, Kreuter MW, Brownson RC. Integrating adult learning principles into training for public health practice. Health Promot Pract 2009; 10: 557–563. 2008/04/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gagne RM, Wager WW, Golas KG, et al. Principles of instructional design. Perform Improv 2005; 44: 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fisch SM. Bridging theory and practice: applying cognitive and educational theory to the design of educational Media. Cognitive development in digital contexts. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science, 2017, pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sweller J. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learn Instr 1994; 4: 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roldán López de Hierro AF, Sánchez M, Puente-Fernández D, et al. A fuzzy delphi consensus methodology based on a fuzzy ranking. Mathematics 2021; 9: 2323. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murray TJ, Pipino LL, van Gigch JP. A pilot study of fuzzy set modification of delphi. Hum Syst Manage 1985; 5: 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saffie NAM, Shukor NM, Rasmani KA. Fuzzy delphi method: issues and challenges. In: 2016 International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Sciences (LISS) 24-27 July 2016, 2016, pp.1–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241242661 for Development and validation of D-PATH website to improve hypertension management among hypertensive patients in Malaysia by Mohd Ramadan Ab Hamid, Siti Sabariah Buhari, Harrinni Md Noor, Nurul ‘Ain Azizan, Khasnur Abd Malek, Ummi Mohlisi Mohd Asmawi and Norazmir Md Nor in DIGITAL HEALTH