Abstract

The phylogenetic position of several clitocyboid/pleurotoid/tricholomatoid genera previously considered incertae sedis is here resolved using an updated 6-gene dataset of Agaricales including newly sequenced lineages and more complete data from those already analyzed before. Results allowed to infer new phylogenetic relationships, and propose taxonomic novelties to accommodate them, including up to ten new families and a new suborder. Giacomia (for which a new species from China is here described) forms a monophyletic clade with Melanoleuca (Melanoleucaceae) nested inside suborder Pluteineae, together with the families Pluteaceae, Amanitaceae (including Leucocortinarius), Limnoperdaceae and Volvariellaceae. The recently described family Asproinocybaceae is shown to be a later synonym of Lyophyllaceae (which includes also Omphaliaster and Trichocybe) within suborder Tricholomatineae. The families Biannulariaceae, Callistosporiaceae, Clitocybaceae, Fayodiaceae, Macrocystidiaceae (which includes Pseudoclitopilus), Entolomataceae, Pseudoclitocybaceae (which includes Aspropaxillus), Omphalinaceae (Infundibulicybe and Omphalina) and the new families Paralepistaceae and Pseudoomphalinaceae belong also to Tricholomatineae. The delimitation of the suborder Pleurotineae (= Schizophyllineae) is discussed and revised, accepting five distinct families within it, viz. Pleurotaceae, Cyphellopsidaceae, Fistulinaceae, Resupinataceae and Schizophyllaceae. The recently proposed suborder Phyllotopsidineae (= Sarcomyxineae) is found to encompass the families Aphroditeolaceae, Pterulaceae, Phyllotopsidaceae, Radulomycetaceae, Sarcomyxaceae (which includes Tectella), and Stephanosporaceae, all of them unrelated to Pleurotaceae (suborder Pleurotineae) or Typhulaceae (suborder Typhulineae). The new family Xeromphalinaceae, encompassing the genera Xeromphalina and Heimiomyces, is proposed within Marasmiineae. The suborder Hygrophorineae is here reorganized into the families Hygrophoraceae, Cantharellulaceae, Cuphophyllaceae, Hygrocybaceae and Lichenomphaliaceae, to homogenize the taxonomic rank of the main clades inside all suborders of Agaricales. Finally, the genus Hygrophorocybe is shown to represent a distinct clade inside Cuphophyllaceae, and the new combination H. carolinensis is proposed.

Taxonomic novelties: New suborder: Typhulineae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado. New families: Aphroditeolaceae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Melanoleucaceae Locq. ex Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Paralepistaceae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Pseudoomphalinaceae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Volvariellaceae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Xeromphalinaceae Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado. New species: Giacomia sinensis J.Z. Xu. Stat. nov.: Cantharellulaceae (Lodge, Redhead, Norvell & Desjardin) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Cuphophyllaceae (Z.M. He & Zhu L. Yang) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Hygrocybaceae (Padamsee & Lodge) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, Lichenomphaliaceae (Lücking & Redhead) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado. New combination: Hygrophorocybe carolinensis (H.E. Bigelow & Hesler) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado. New synonyms: Sarcomyxineae Zhu L. Yang & G.S. Wang, Schizophyllineae Aime, Dentinger & Gaya, Asproinocybaceae T. Bau & G.F. Mou. Incertae sedis taxa placed at family level: Aphroditeola Redhead & Manfr. Binder, Giacomia Vizzini & Contu, Hygrophorocybe Vizzini & Contu, Leucocortinarius (J.E. Lange) Singer, Omphaliaster Lamoure, Pseudoclitopilus Vizzini & Contu, Resupinatus Nees ex Gray, Tectella Earle, Trichocybe Vizzini. New delimitations of taxa: Hygrophorineae Aime, Dentinger & Gaya, Phyllotopsidineae Zhu L. Yang & G.S. Wang, Pleurotineae Aime, Dentinger & Gaya, Pluteineae Aime, Dentinger & Gaya, Tricholomatineae Aime, Dentinger & Gaya. Resurrected taxa: Fayodiaceae Jülich, Resupinataceae Jülich.

Citation: Vizzini A, Alvarado P, Consiglio G, Marchetti M, Xu J (2024). Family matters inside the order Agaricales: systematic reorganization and classification of incertae sedis clitocyboid, pleurotoid and tricholomatoid taxa based on an updated 6-gene phylogeny. Studies in Mycology 107: 67–148. doi: 10.3114/sim.2024.107.02

Keywords: Agaricales, Agaricanae, incertae sedis taxa, multi-locus, new taxa, phylogeny, taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

Tricholomatineae is one of the suborders in which order Agaricales is currently divided. It names a lineage whose monophyletic status is significantly supported by phylogenomic and multilocus phylogenetic analyses (Dentinger et al. 2016, Zhao et al. 2017, Varga et al. 2019, Ke et al. 2020, Olariaga et al. 2020, Sánchez-García et al. 2020, Wang et al. 2023b). This suborder corresponds to the Tricholomatoid clade as delimited by Binder et al. (2010), which was also detected before them by other authors (Moncalvo et al. 2002, Matheny et al. 2006, Garnica et al. 2007). It currently contains about thirty genera, including ectomycorrhizal and nonectomycorrhizal groups (Sánchez-García et al. 2014, Sánchez-García 2016). In addition to the Tricholomataceae (Sánchez-García et al. 2014), it currently encompasses another 10 families: Asproinocybaceae (Bau & Mou 2021), Biannulariaceae (Vizzini et al. 2020a), Callistosporiaceae (Vizzini et al. 2020a), Clitocybaceae (Alvarado et al. 2015, Vizzini et al. 2020b), Entolomataceae (Kluting et al. 2014), Fayodiaceae (Moncalvo et al. 2002), Lyophyllaceae (Hofstetter et al. 2014, Bellanger et al. 2015), Macrocystidiaceae (Dentinger et al. 2016), Omphalinaceae (Vizzini et al. 2020b), and Pseudoclitocybaceae (Alvarado et al. 2018a).

Still, many white-spored clitocyboid and tricholomatoidlooking genera cannot be easily classified within any of these families, and even their position inside suborder Tricholomatineae cannot be confirmed with phylogenetic analyses because of the incomplete data available from some of them (mostly ribosomal DNA sequences). For example, the classification of Asproinocybe, Aspropaxillus, Dendrocollybia, Giacomia, Hertzogia, Hygrophorocybe, Infundibulicybe, Lepistella, Leucocortinarius, Notholepista, Omphaliaster, Omphalina, Paralepista, Paralepistopsis, Pseudoclitopilus, Pseudoomphalina, Resupinatus, Rimbachia, Ripartites, Trichocybe or Tricholosporum is not fully clear (Vizzini et al. 2010, 2012a, b, 2020, Hofstetter et al. 2014, Sánchez-García et al. 2014, 2016, 2017, Vizzini 2014a, Angelini et al. 2017, Alvarado et al. 2018a, b, He et al. 2019, Raj et al. 2019, Varga et al. 2019, Kalichman et al. 2020, Olariaga et al. 2020, He & Yang 2022, Wiest 2022).

The classification of these incertae sedis lineages requires the reconstruction of the phylogeny of the entire order Agaricales. DNA-based studies of the evolutionary history and taxonomy of Agaricales can be classified in different stages, depending on the scope and the sources of information employed:

Early works: the first sequence-based phylogenetic analyses of fungi were not specifically focused on the internal structure of Agaricales, but instead addressed fungal classification at higher ranks and/or investigated the origin of specific morphological types (Swann & Taylor 1993, 1995a, b, Gargas et al. 1995, Hibbett et al. 1997, Bruns et al. 1998, Pine et al. 1999, Thorn et al. 2000, Hibbett & Donoghue 2001, Hibbett & Thorn 2001, Binder & Hibbett 2002, Hibbett & Binder 2002). These works were based on too scarce information, often coming from a single ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene region obtained from distant and highly diverse groups.

Mainly LSU-based works: the internal structure of order Agaricales was specifically addressed at first employing sequences of nuclear rDNA, typically the 28S or large subunit (LSU). These works (Moncalvo et al. 2000, 2002, Bodensteiner et al. 2004, Binder et al. 2005, 2006, Walther et al. 2005) successfully obtained significant support for multiple clades inside Agaricales, helping to delimit the phylogenetic concept of classical families. However, the relationships between these families were rarely resolved with this approach, and sometimes results varied if different datasets were employed.

Multigene works: the addition of more information coming from protein-coding genes greatly improved the outcome of phylogenetic analyses of Agaricales. A relationship between the amount of information and the significance of results seems plausible. For example, the use of LSU, SSU (the 18S nrDNA or small subunit), RPB1 (DNA-directed RNA polymerase II, largest subunit) and RPB2 (DNA-directed RNA polymerase II, second largest subunit) (Matheny et al. 2006) allowed to produce a seminal reconstruction of the structure of Agaricales, obtaining statistical support for multiple major clades (now suborders). However, a more limited analysis using only LSU and RPB1 (Garnica et al. 2007) led to good support values for most suborders, excepting Tricholomatineae and Marasmiineae, while Hygrophorineae could not be separated from the pteruloid lineages. The analysis of additional information, coming from LSU, SSU, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF1 (translation elongation factor 1-alpha) sequences (Matheny et al. 2007) suggested some changes to the previous results (i.e., in the position of Pluteus and Amanita) but the new dataset also contained a different selection of taxa. A too diverse dataset could be the cause behind the lack of support of most suborders of Agaricales in the analysis of Binder et al. (2010), a work focused on the closely related order Amylocorticiales which included also sequences of Boletales, Atheliales and Jaapiales, as well as other orders as outgroups. The phylogenies in Zhao et al. (2017) and He et al. (2019) used even larger datasets containing all lineages of Basidiomycotina and some Ascomycotina, and both failed to obtain significant support for most suborders and families of Agaricales. On the other hand, Olariaga et al. (2020) employed a dataset filling an important gap in the diversity of this order, that of typhuloid fungi, obtaining good support for most suborders, but missed important lineages from some of them (i.e., Giacomia, Hohenbuehelia, Limacella, Mycena, Resupinatus, Volvariella). The most recent study of Agaricales following the multigene phylogenetic approach is that of Sheikh et al. (2022), which analyzed a large dataset of LSU, SSU, RPB1 and RPB2 sequences of multiple species of Ascomycotina, Basidiomycotina and Mucoromycotina. While support values cannot be directly checked in the published figures, the position of several clades does not fit with that in previous works, i.e., Amanitaceae (nested in Agaricineae), Hypsizygus (nested in Pluteineae), Cantharocybe and Tricholomopsis (nested in Pleurotineae), Sarcomyxaceae (sister to Hygrophorineae), or Typhulaceae and Phyllotopsidineae (related and sister to Marasmiineae).

Phylogenomic works: Next generation sequencing (NGS) of entire genomes provides a much larger amount of information than Sanger sequencing of individual target regions. The first attempts to build a genome database of fungi (Grigoriev et al. 2014) were followed by the first phylogenomic analysis of Agaricales (Dentinger et al. 2016), that employed 208 different loci. The result was the proposal of a new taxonomic arrangement dividing Agaricales into seven distinct suborders, which matched more or less the clades found in previous phylogenetic studies based on 5–6 loci. Later, Ke et al. (2020) incorporated additional information from genomes produced by multiple researchers, as well as those of five bioluminiscent species of Mycenaceae obtained by them. After the analysis of 360 loci, they produced a phylogeny consistent with that of Dentinger et al. (2016), but unfortunately important clades were not included (i.e., Hygrophorineae, Clavariineae, Phyllotopsidineae, Tricholomatineae). Li et al. (2021) built a phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi based on sequences of 290 loci obtained from genomic data of 1 679 taxa (89 Agaricales), obtaining significant support for the suborders Agaricineae, Pluteineae and Tricholomatineae, but apparently merging Hygrophorineae and the family Clavariaceae, as well as Pleurotineae and Pterulaceae. Recently, Wang et al. (2023b) further improved the resolution of phylogenomic studies by sequencing 38 new genomes, from which 555 genes were compared with those of the other sequenced Agaricales. As a result, ten suborders were recognized (after separating Phyllotopsidineae and Sarcomyxineae from Pleurotineae), but some families did not nest inside any of them (i.e., Mycenaceae and Typhulaceae).

In the present study, new sequences from some of the aforementioned incertae sedis taxa (Tables 1–3, S1, Figs 6–8) were produced in order to resolve their most probable phylogenetic position after the analysis of an updated 6-gene dataset of Agaricales. Additional sequences from other clades were produced as well to create a representative background for phylogenetic analysis. Results are compared with those published in previous works and different taxonomic decisions are taken accordingly.

Table 1.

Taxa, vouchers, and GenBank accessions numbers of the DNA sequences used in the Agaricales-wide phylogenetic analysis inferred from a six-gene dataset (5.8S, LSU, SSU, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF1). Sequences in bold were generated in this study.

| Group | Species | Voucher | LSU | RPB2 | SSU | TEF1 | ITS | RPB1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricineae | Agaricus bisporus | AFTOL-ID 448, RWK1885 | AY635775 | genome | AY787216 | GU187673 | DQ404388 | — |

| Apioperdon pyriforme | AFTOL-ID 480, DSH 96-054 | AF287873 | AY218495 | AF026619 | AY883426 | AY854075 | AY860523 | |

| Bolbitius vitellinus | AFTOL-ID 730, MTS5020 | AY691807 | — | AY705955 | DQ408148 | DQ200920 | DQ435802 | |

| Conocybe lactea | AFTOL-ID 1675, CUWPBM2706 + NL1012 | DQ457660 | DQ470834 | DQ437683 | JX968427 | DQ486693 | DQ447893 | |

| Coprinopsis cinereus | A43mut B43mut pab1-1 #326 | AF041494 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Coprinus comatus | AFTOL-ID 626, ECV3198 | AY635772 | AY780934 | AY665772 | AY881026 | AY854066 | AY857983 | |

| Cortinarius iodes | AFTOL-ID 285, PBM2426 | AY702013 | AY536285 | AY771605 | AY881027 | AF389133 | AY857984 | |

| Crepidotus cf. applanatus | WTUPBM717 | AY380406 | AY333311 | AY705951 | DQ028581 | DQ202273 | AY333303 | |

| Crucibulum laeve | CBS:166.37 | MH867376 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Cyathus striatus | NPCB87405 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Cystoderma amianthinum | HKAS: 107327 + AFTOL-ID 1553 | MW258914 | MW289806 | DQ440632 | MW324496 | MW258862 | MW289817 | |

| Echinoderma flavidoasperum | KUN-HKAS:87905 | MN810098 | MN820969 | — | MN820903 | MN810147 | — | |

| Floccularia luteovirens | FLZJUC10 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Hebeloma velutipes | AFTOL-ID 980, PBM2277 | AY745703 | DQ472718 | AY752972 | GU187707 | AY818351 | DQ447904 | |

| Hydnangium cameurn | Trappe31123 | KU685892 | KU686038 | — | KU686144 | KU685741 | — | |

| Inocybe myriadophylla | AFTOL-ID 482, V19652F | AY700196 | AY803751 | AY657016 | DQ435791 | DQ221106 | DQ447916 | |

| Laccaria bicolor | S238N-H82 | genome | XM001873347 | genome | XM001873179 | JX312964 | XM001881359 | |

| Macrolepiota dolichaula | AFTOL-ID 481, HKAS:38718 | DQ411537 | DQ385886 | AY771602 | DQ435785 | DQ221111 | DQ447920 | |

| Mythicomyces corneipes | AFTOL-ID 972, PBM1210 | AY745707 | DQ408110 | DQ092917 | DQ029197 | DQ404393 | DQ447929 | |

| Parasola conopilea | ZRL20151990 + LO186-02 | DQ389725 | KY419025 | KY418946 | KJ732832 | LT716064 | — | |

| Pholiota gummosa | TENN:074768, HMJAU:37426, ET34-ET8 | MN251152 | MN329726 | — | MN311973 | MN209769 | — | |

| Romagnesiella clavus | AMB:15091, ALV16952 + LIPPAM06090110 | MK353795 | MK359092 | MK353799 | — | EF051060 | — | |

| Squamanita schreieri | ZT:Myc2185 | MW258904 | MW289801 | MW258882, MW258931 | MW324510 | MW258852 | — | |

| Tubaria confragosa | AFTOL-ID 498, PBM2105 | AY700190 | DQ408113 | AY665776 | — | DQ267126 | DQ447944 | |

| Clavariineae | Camarophyllopsis hymenocephala | AFTOL-ID 1892, DJL98-081505 | DQ457679 | DQ472726 | DQ444862 | — | DQ484066 | DQ516070 |

| Ceratellopsis acuminata | CBS:146691 + S.Huhtinen 15/07 - EPITYPE | NG_075348 | MT242330 | NG_070864 | MT242352 | MT232347 | MT242316 | |

| Clavaria inaequalis | AFTOL-ID 984, CUW:MB04-016 | AY745693 | DQ385880 | DQ437680 | DQ029198 | DQ202267 | DQ447890 | |

| Clavaria zollingeri | AFTOL-ID 563, TENN:58652 | AY639882 | AY780940 | AY657008 | AY881024 | AY854071 | AH014578 | |

| Ramariopsis kunzei | GG141104 | EF561638 | GU187807 | GU187647 | GU187745 | GU187552 | GU187479 | |

| Hygrophorineae | Ampulloclitocybe clavipes | AFTOL-ID 542, PBM2474 | AY639881 | AY780937 | AY771612 | AY881022 | AY789080 | AY788848 |

| Cantharocybe gruberi | AFTOL-ID 1017 | DQ234540 | DQ385879 | DQ234546 | DQ059045 | DQ200927 | — | |

| Chromosera cyanophylla | AFTOL-ID 1684, WTUPBM1577 | DQ457655 | KF381509 | DQ435813 | — | DQ486688 | — | |

| Chrysomphalina grossula | OSC:113683 | EU652373 | DQ470832 | AY752969 | — | EU644704 | DQ516072 | |

| Cuphophyllus aurantius | CFMRPR6601 | KF291100 | KF291102 | KF291101 | — | KF291099 | — | |

| Cuphophyllus sp. | KUN-HKAS:105671, JSP346 | MW763000 | MW789179 | — | — | MW762875 | MW789163 | |

| Gloioxanthomyces nitidus | GDGM:41710 | MG712282 | MG711911 | — | — | MG712283 | — | |

| Hygroaster albellus | AFTOL-ID 1997 | EF551314 | KF381510 | KF381532 | — | KF381521 | — | |

| Hygrocybe coccinea | AFTOL-ID 1715, WTUPBM915 | DQ457676 | DQ472723 | — | GU187705 | DQ490629 | DQ447910 | |

| Hygrophorocybe nivea | LPA:SMGC2020121621 | OR863514 | OR828267 | OR863576 | OR828325 | OR863446 | — | |

| Hygrophorus aurantiosquamosus | KUN-HKAS:112569 | MW763001 | MW789180 | — | MW773440 | MW762876 | MW789164 | |

| Hygrophorus pudorinus | AFTOL-ID 1723, CUWPBM2721 | DQ457678 | DQ472725 | DQ444861 | GU187710 | DQ490631 | DQ447912 | |

| Lichenomphalia umbellifera | CFMR:J.Geml2 + GAL9547 | GU811045 | KF381515 | KF381538 | GU811010 | GU810969 | — | |

| Neohygrocybe ingrata | TENN:DJL05TN62 | KF381558 | KF381516 | KF381539 | — | KF381525 | — | |

| Neohygrocybe ovina | Rhosisaf ABS + K:M187568, GEDC0877 | KF291234 | KF291236 | KF291230 | — | KF291233 | — | |

| Porpolomopsis aff. calyptrifbrmis | TENN:DJL05TN80 | KF291247 | KF291249 | KF291248 | — | KF291246 | — | |

| Porpolomopsis lewelliniae | CORTTJB10034 | KF291239 | KF291241 | KF291240 | — | KF291238 | — | |

| Pseudoarmillariella ectypoides | AFTOL-ID 1557, PBM1588 | DQ154111 | DQ474127 | DQ465341 | GU187733 | DQ192175 | DQ516076 | |

| Spodocybe rugosiceps | KUN-HKAS:112563 - TYPE | MW763013 | MW789192 | — | MW789160 | MW762888 | MW789176 | |

| Marasmiineae | Anthracophyllum archeri | AFTOL-ID 973, PBM2201 | AY745709 | DQ385877 | DQ092915 | DQ028586 | DQ404387 | DQ435799 |

| Armillaria mellea | AFTOL-ID 449, PBM2470 | AY700194 | AY780938 | AY787217 | AY881023 | AY789081 | AY788849 | |

| Baeospora myosura | AFTOL-ID 1799, CUWPBM2748 | DQ457648 | — | DQ435796 | GU187762 | DQ484063 | DQ435801 | |

| Cheimonophyllum candidissimum | AFTOL-ID 1765, WTUPBM2411 | DQ457654 | DQ470831 | DQ435812 | GU187760 | DQ486687 | DQ447888 | |

| Dictyopanus pusillus | LMB36 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Favolaschia claudopus | BBC-V001 23/10/2022 | OR863498 | OR828255 | OR863564 | OR828316 | OR863428 | — | |

| Flammulina velutipes | AFTOL-ID 558, TENN:52002 | AY639883 | AY786055 | AY665781 | AY883423 | AY854073 | AY858966 | |

| Gymnopus contrarius | AFTOL-ID 1758, CUWPBM2711 | DQ457670 | DQ472716 | DQ440643 | GU187700 | DQ486708 | DQ447902 | |

| Heimiomyces aff. tenuipes | McAdoo725 | OR863508 | OR828263 | OR863572 | OR828321 | OR863439 | — | |

| Hemimycena lactea | OULU:GAJ15636 | OR863509 | OR828264 | OR863573 | OR828322 | OR863440 | — | |

| Megacollybia platyphylla | AFTOL-ID 560, TENN:59432 | AY635778 | DQ385887 | AY786053 | DQ435786 | DQ249275 | DQ447923 | |

| Mycena chlorophos | 110903 Hualien Pintung | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycena citricolor | CBS:193.57 | MH869233 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycena galopus | ATCC:62051 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycena indigotica | 171206 Taipei | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycena kentingensis | 111111 Pintung | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycena sanguinolenta | 160909 Yilan | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Mycetinis alliaceus | AFTOL-ID 556, TENN:55620 | AY635776 | AY786060 | AY787214 | AY883431 | AY854076 | — | |

| Panellus luminescens | KLU:M1278, ACL205 | KJ206955 | KJ406362 | — | — | KJ206979 | — | |

| Panellus stypticus | CORT11CA052 | KR869943 | KC816996 | — | KC816902 | — | — | |

| Phloeomana gracilis | AFTOL-ID 1732, CUW:PBM2715 | DQ457671 | DQ472719 | DQ440644 | GU187709 | DQ490623 | DQ447905 | |

| Porotheleum fimbriatum | AFTOL-ID 1725, CBS:788.86 | DQ457673 | DQ472721 | DQ444854 | — | DQ490626 | DQ447907 | |

| Rhodocollybia maculata | AFTOL-ID 540, PBM2481 | AY639880 | AY787220 | AY752966 | DQ061279 | DQ404383 | DQ447936 | |

| Roridomyces sp. | KLU:M1292, ACL273 | KJ206958 | KJ406372 | — | — | — | — | |

| Xeromphalina Campanella | TENN:F069178 + GLM 46039 | KM011910 | KP835655 | — | — | KP835678 | DQ067940 | |

| Xerula radicata | AFTOL-ID 561, TENN:59235 | AY645051 | AY786067 | AY654884 | DQ029194 | DQ241780 | DQ447946 | |

| Outgroup | Amylocorticium cebennense | CFMR:HHB-2808 | GU187561 | GU187770 | GU187612 | GU187675 | GU187505 | GU187439 |

| Ceraceomyces borealis | CFMR:L-8014 | GU187570 | GU187782 | GU187624 | GU187686 | GU187512 | — | |

| Suillus pictus | AFTOL-ID 717, MB 03-002 | AY684154 | AY786066 | AY662659 | AY883429 | AY854069 | AY858965 | |

| Phyllotopsidineae | Aphanobasidium pseudotsugae | CFMR:HHB-822 | GU187567 | GU187781 | GU187620 | GU187695 | GU187509 | GU187455 |

| Aphroditeola sp. | HRL1230 | OR863490 | OR828247 | OR863558 | OR828309 | OR863420 | — | |

| Aphroditeola sp. | TRgmb00556 | OR863491 | OR828248 | OR863559 | OR828310 | OR863421 | — | |

| Aphroditeola sp. | TRgmb00561 | OR863492 | OR828249 | OR863560 | — | OR863422 | — | |

| Cristinia sp. | CFMR:FP100305 | GU187585 | — | GU187637 | GU187718 | GU187526 | GU187470 | |

| Lindtneria flava | K:M143556 | KM086909 | — | — | KM087001 | KM086815 | — | |

| Macrotyphula fistulosa | S:IO.14.214, UPS:IO.14.214 + 10.15.123 | KY224088 | MT242336 | MT232495 | MT242354 | MT232352 | MT242317 | |

| Macrotyphula juncea | 10.14.177 | MT232306 | MT242337 | — | MT242355 | MT232353 | — | |

| Macrotyphula phacorrhiza | S:IO.14.200 | MT232314 | — | MT232505 | MT242366 | MT232363 | — | |

| Phyllotopsis sp. | AFTOL-ID 773, MB35 | AY684161 | AY786061 | AY707090 | DQ059047 | DQ404382 | DQ447933 | |

| Pleurocybella porrigens | UPS:F611822 + AFTOL-ID 2001, JFA12544 + TUB:012154 | EF537894 | MT242339 | GU187660 | GU187740 | MT232355 | DQ067994 | |

| Pterula echo | AFTOL-ID 711, DJM302S58 | AY458123 | GU187805 | DQ092911 | GU187743 | DQ494693 | — | |

| Pterula echo | ZRL20151311 | KY418881 | KY419026 | KY418947 | KY419076 | LT716065 | KY418979 | |

| Pterula gracilis | S:IO.14.142 | MT232310 | — | MT232498 | — | MT232356 | — | |

| Radulomyces molaris | ARAN:Fungi2003 | MT232311 | MT242340 | MT232499 | MT242359 | — | MT242320 | |

| Sarcomyxa edulis | HMJAU7066 | GQ219739 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Sarcomyxa serotina | AFTOL-ID 536, PBM2519 | AY691887 | DQ859892 | U59088 | GU187754 | DQ494695 | DQ447938 | |

| Stephanospora caroticolor | IOC-137/97+ TUB:019072 | AF518652 | — | AF518591 | GU187747 | AJ419224 | KF211335 | |

| Tectella patellaris | McAdoo991 | OR863548 | OR828299 | OR863602 | OR828350 | OR863481 | — | |

| Tricholomopsis decora | AFTOL-ID 537, PBM2482 | AY691888 | DQ408112 | DQ092914 | DQ029195 | DQ404384 | DQ447943 | |

| Tricholomopsis osiliensis | ZRL20151760 | KY418884 | KY419029 | KY418949 | KY419079 | — | — | |

| Pleurotineae | Auriculariopsis ampla | NL-1724 | OL957174 | genome | genome | genome | OL957174 | — |

| Fistulina antarctica | AFTOL-ID 1335, CBS:701.85 | AY293181 | DQ472713 | AY293131 | GU187698 | DQ486702 | — | |

| Flagelloscypha sp. | PMI 526 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Hohenbuehelia atrocoerulea | AMB: 18080 | KU355389 | KU355418 | — | KU355439 | KU355304 | — | |

| Hohenbuehelia faerberioides | Mertens | MG553645 | MW240980 | — | MW240984 | MG553638 | — | |

| Hohenbuehelia grisea | MCVE:27293 | KU355394 | — | — | KU355447 | KU355329 | — | |

| Hohenbuehelia tremula | AFTOL-ID 1503, PBM2301 | — | — | DQ440645 | — | DQ182504 | — | |

| Hohenbuehelia tremula | DAOM:180808 | KU355405 | KU355434 | — | KU355465 | KU355357 | OR828361 | |

| Hohenbuehelia unguicularis | Z+ZT1112 | KU355408 | — | — | KU355467 | KU355361 | — | |

| Lachnella villosa | CBS:609.87, AFTOL-ID 525 + CCJ1547 | DQ097347 | — | AY705959 | GU187721 | DQ097362 | DQ068007 | |

| Pleurotus citrinopileatus | Hfpri PC 051Y1-BHFW01000088 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Pleurotus dryinus | AMB:18868 | OR863538 | OR828286 | OR863593 | OR828338 | OR863471 | OR828363 | |

| Pleurotus fuscosquamulosus | A. Baglivo 13-07-2014 | — | OR828287 | — | OR828339 | OR863472 | — | |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | AFTOL-ID 564, TENN:53662 | AY645052 | AY786062 | AY657015 | AY883432 | AY854077 | AY862186 | |

| Pleurotus salmoneostramineus | NBRC-31859 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Pleurotus tuber-regium | ACCC:50657-18 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Porodisculus orientalis | G0896 + SNU-m 030828-101 | MK278522 | EU423191 | — | — | EU423186 | — | |

| Resupinatus applicatus | AMB:18098 | MH430596 | — | — | MH449588 | MH137821 | — | |

| Resupinatus europaeus | AMB: 18078 | KU355409 | — | — | KU355468 | KU355368 | — | |

| Resupinatus griseopallidus | AMB:18277 | MH165881 | — | — | — | MH137823 | — | |

| Resupinatus kavinae | AMB:19612 | OR863543 | OR828293 | — | OR828344 | OR863477 | — | |

| Resupinatus niger | AMB: 18095 | KU355413 | — | — | KU355470 | KU355371 | — | |

| Resupinatus rouxii | Z+ZT971 | MH190787 | — | — | MH449590 | MH137828 | — | |

| Resupinatus striatulus | JA:Cussta8634 | MH430597 | — | — | MH449591 | MH137829 | — | |

| Resupinatus vetlinianus | TENNP69285, TFB14587 | KP987309 | — | — | — | KP026243 | — | |

| Schizophyllum radiatum | AFTOL-ID 516, CBS:301.32 | MH866782 | DQ484052 | AY705952 | — | MH855328 | DQ447939 | |

| Pluteineae | Amanita brunnescens | AFTOL-ID 673, PBM2429 | AY631902 | AY780936 | AY707096 | AY881021 | AY789079 | AY788847 |

| Amanita phalloides | HKAS:75773 + TUB:011556 | JX998060 | KJ466612 | — | JX998000 | JX998031 | DQ067953 | |

| Amanita subglobosa | HKAS:58837 | JN941152 | JQ031121 | JN941126 | KJ482004 | JN943177 | JN994123 | |

| Catatrama costaricensis | DAOM:211663 | KT833804 | KT833819 | — | KT833834 | — | — | |

| Giacomia mirabilis | AMB:19297 | JQ639154 | OR828261 | OR863570 | — | JQ639153 | — | |

| Giacomia mirabilis | ANGE1598 | OR863505 | OR828262 | OR863571 | OR828320 | OR863436 | OR828360 | |

| Giacomia sinensis | HMJU:265 - TYPE | MZ435884 | MZ441372 | MZ435869 | MZ441376 | MZ435888 | MZ441380 | |

| Giacomia sinensis | HMJU:268 | MZ435885 | MZ441373 | MZ435870 | MZ441377 | MZ435889 | MZ441381 | |

| Leucocortinarius bulbiger | AMB: 19593 | OR864301 | OR828271 | OR863581 | OR828326 | — | — | |

| Leucocortinarius bulbiger | TUB:011568 | DQ071745 | — | — | — | — | DQ068019 | |

| Limacella glioderma | HKAS:90169 + ZLYD 72 | KT833808 | KT833823 | — | KT833836 | MH508658 | DQ067952 | |

| Limacellopsis asiatica | HKAS:101436 | MH486964 | MH486357 | — | MH509184 | — | — | |

| Limacellopsis guttata | MB100157 | KT833813 | KT833828 | — | KT833841 | — | — | |

| Limnoperdon incarnatum | IFO:30398 | AF426958 | — | AF426952 | — | DQ097363 | — | |

| Limnoperdon sp. | CBS:160.95 | OR863524 | OR828272 | OR863582 | OR828327 | OR863457 | — | |

| Melanoleuca aff. graminicola | AMB:19613 | OR863528 | OR828276 | OR863586 | OR828331 | OR863461 | — | |

| Melanoleuca communis | ZRL20151882 | KY418885 | KY419030 | KY418950 | KY419080 | LT716069 | — | |

| Melanoleuca exscissa | AMB:19614 | OR863530 | OR828278 | OR863588 | OR828332 | OR863463 | — | |

| Melanoleuca exscissa | BRNM781061 + LAS97-019 | — | LT594191 | — | LT594175 | LT594122 | JX429104 | |

| Melanoleuca friesii | AMB: 18865 | OR863531 | OR828279 | OR863589 | OR828333 | OR863464 | — | |

| Melanoleuca microcephala | HMJAS:00138 + BRNM:817787 | MK660045 | MW488179 | — | MW488164 | MW491334 | — | |

| Melanoleuca rasilis | BRNM751967, G0924 | MK278374 | LT594187 | — | LT594171 | LT594154 | — | |

| Melanoleuca tristis | AMB:18866 | OR863532 | OR828280 | OR863590 | OR828334 | OR863465 | OR828362 | |

| Melanoleuca verrucipes | WTUPBM2289, AFTOL-ID 818 | DQ457687 | DQ474119 | DQ457645 | GU 187726 | DQ490642 | DQ447924 | |

| Pluteus cervinus | AMB:18870 | OR863539 | OR828288 | OR863594 | OR828340 | OR863473 | OR828364 | |

| Pluteus hongoi | ZRL20151600 | KY418878 | KY419023 | — | KY419074 | LT716062 | — | |

| Pluteus multiformis | PL40, AC4249, AH:40107 - TYPE | MK278503 | LR697101 | — | LR697100 | HM562201 | — | |

| Pluteus romellii | AFTOL-ID 625, ECV3201 | AY634279 | AY786063 | AY657014 | AY883433 | AY854065 | AY862187 | |

| Pluteus romellii | AMB:18871 | OR863540 | OR828289 | OR863595 | OR828341 | OR863474 | — | |

| Pluteus variabilicolor | AMB:18872 | OR863541 | OR828290 | OR863596 | OR828342 | OR863475 | OR828365 | |

| Pluteus variabilicolor | AMB:18873 | OR863542 | OR828291 | OR863597 | OR828343 | OR863476 | OR828366 | |

| Saproamanita thiersii | SKay4041 | HQ593114 | genome | genome | genome | HQ625010 | genome | |

| Volvariella aff. nigrovolvacea | AMB:18775 | OR863550 | OR828301 | OR863604 | OR828352 | OR863483 | OR828367 | |

| Volvariella aff. pusilia | AMB:19290 | OR863552 | OR828303 | OR863606 | OR828354 | OR863485 | OR828368 | |

| Volvariella aff. pusilia | K:M145618 | OR863551 | OR828302 | OR863605 | OR828353 | OR863484 | — | |

| Volvariella bombycina | AMB:19312 | OR863553 | OR828304 | OR863607 | OR828355 | OR863486 | — | |

| Volvariella caesiotincta | AMB:19319 | OR863554 | OR828305 | — | OR828356 | OR863487 | — | |

| Volvariella volvacea | PDD:96362, JAC12235 | MN738572 | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | |

| Volvopluteus earlei | AGMT-71 | OR863556 | OR828307 | OR863609 | OR828358 | MK204989 | — | |

| Volvopluteus gloiocephalus | AFTOL-ID 890 | AY745710 | — | DQ089020 | — | DQ494701 | DQ447945 | |

| Volvopluteus gloiocephalus | NTNU:27884555 | OR863557 | OR828308 | OR863610 | OR828359 | OR863489 | — | |

| Zhuliangomyces illinitus | HKAS:90168 | KT833814 | KT833829 | — | KT833842 | MH508659 | — | |

| Tricholomatineae | Asproinocybe sinensis | HMJAU:59026 | OK377051 | OK625401 | OK377040 | OK625331 | OK377048 | OK625398 |

| Aspropaxillus giganteus | AMB:18857 | OR863493 | OR828250 | OR863561 | OR828311 | OR863423 | — | |

| Atractosporocybe inornata | HKAS:105578 + TO:AV201012d | MZ714592 | MZ681898 | KJ681075 | MZ681877 | MZ714587 | MZ681888 | |

| Bonomyces sinopicus | KATO:Fungi-3689 | MG696627 | MG702595 | MG696623 | MG702592 | MG696619 | — | |

| Callistosporium graminicolor | AFTOL-ID 978, WTU:PBM2341 | AY745702 | — | AY752974 | GU187761 | DQ484065 | GU187493 | |

| Catathelasma ventricosum | DAOM:225247 | MN017477 | MN018851 | MN017585 | MN026906 | MN017537 | KP255480 | |

| Clitocella fallax | CBS:129.63 | AF223166 | EF421018 | — | EF421089 | AF357017 | EF421051 | |

| Clitocybe dealbata | IE-BSG HC95.cp3 | AF223175 | DQ825407 | DQ825431 | EF421080 | AF357061 | DQ825414 | |

| Clitocybe ditopa | AMB:19311 | OR863496 | OR828253 | OR863563 | OR828314 | OR863426 | — | |

| Clitocybe nebularis | AFTOL-ID 1495, WTU:PBM2259 + CBS:362.65 | DQ457658 | EF421011 | DQ437681 | EF421081 | AF357063 | DQ825415 | |

| Clitocybe subditopoda | AFTOL-ID 533, PBM2489 | AY691889 | AY780942 | AY771608 | DQ408150 | DQ202269 | DQ447892 | |

| Clitolyophyllum akcaabatense | P. Alvarado 5836 | OR863497 | OR828254 | — | OR828315 | OR863427 | — | |

| Clitopaxillus alexandri | TO:AV45634 | MG321393 | MG334546 | MG321329 | MG334537 | MG321345 | — | |

| Clitopilopsis hirneola | CORTTB8490 +CORTREH8490 | GU384611 | GU384646 | — | KC816820 | — | — | |

| Clitopilus pallidogriseus | MENoordeloos2004032 + CORTE652 | GQ289216 | GQ289283 | — | KC816875 | — | — | |

| Collybia tuberosa | AFTOL-ID 557, TENN:53540 | AY639884 | AY787219 | AY771606 | AY881025 | AY854072 | AY857982 | |

| Entoloma prunuloides | AFTOL-ID 523, TJB4765 | AY700180 | DQ385883 | AY665784 | DQ457633 | DQ206983 | DQ447898 | |

| Entoloma undatum | HKAS:115925 | MZ853561 | MZ852824 | — | — | MZ855875 | MZ852812 | |

| Fayodia bisphaerigera | OW241-19 | OR863499 | OR828256 | — | OR828317 | OR863429 | — | |

| Gamundia sp. | YM18172 | OR863500 | OR828257 | OR863565 | OR828318 | OR863430 | — | |

| Gamundia striatula | JL45-18 | OR863501 | OR828258 | OR863566 | OR828319 | OR863431 | — | |

| Harmajaea harperi | LIP:0401361 | MG321399 | MG334549 | MG321333 | MG334541 | MG321366 | — | |

| Hertzogia martiorum | AMB:18863 | OR863510 | OR828265 | OR863574 | OR828323 | OR863441 | — | |

| Hypsizygus ulmarius | DUKE:JM/HW | AF042584 | EF420996 | — | EF421062 | EF421105 | EF421030 | |

| Infundibulicybe geotropa | AMB:18861 | OR863518 | OR828268 | OR863577 | — | OR863450 | — | |

| Infundibulicybe gibba | AFTOL-ID 1508, CUW:JCS0704B | DQ457682 | DQ472727 | DQ115780 | GU187759 | DQ490635 | DQ447913 | |

| Lepista glaucocana | AMB: 18862 | OR863520 | — | OR863579 | — | OR863452 | — | |

| Lepista Irina | AFTOL-ID 815, WTUPBM2291 | DQ234538 | DQ385885 | AY705948 | DQ028591 | DQ221109 | DQ447919 | |

| Lepista ricekii | AMB: 18864 | OR863521 | OR828270 | OR863580 | — | OR863453 | — | |

| Lepista saeva | TENN:066100, ADW0097 | KJ417193 | KJ424376 | KJ417159 | — | KJ137270 | — | |

| Leucocybe candicans | AFTOL-ID 541, PBM2476 | AY645055 | DQ385881 | AY771609 | DQ408149 | DQ202268 | DQ447891 | |

| Lyophyllum semitale | HC85/13 | AF042581 | EF421002 | — | EF421068 | AF357049 | EF421036 | |

| Lyophyllum turcicum | GB:0065321 | OR863525 | OR828273 | OR863583 | OR828328 | OR863458 | — | |

| Macrocystidia cucumis | JX.1294733#45 | OR863527 | OR828275 | OR863585 | OR828330 | OR863460 | — | |

| Macrocystidia sp. | Kekki3956 | OR863526 | OR828274 | OR863584 | OR828329 | OR863459 | — | |

| Musumecia bettlachensis | TO:HG2284 | JF926521 | KJ681060 | KJ681069 | KJ681082 | JF926520 | — | |

| Nolanea sericea | VHAs03/02 | DQ367423 | DQ367435 | DQ367421 | DQ367428 | DQ367430 | DQ825424 | |

| Notholepista fistulosa | HKAS:115934 | OK104059 | OK105137 | — | OK105127 | OK104077 | OK105132 | |

| Notholepista fistulosa | HMJU:288 | MZ435886 | MZ441374 | MZ435871 | MZ441378 | MZ435890 | MZ441382 | |

| Notholepista fistulosa | HMJU:592 | MZ435887 | MZ441375 | MZ435872 | MZ441379 | MZ435891 | MZ441383 | |

| Notholepista subzonalis | GB:0087013 | KJ417208 | KJ424385 | KJ417167 | — | KP453695 | — | |

| Omphaliaster borealis | TROM:43 | OR863533 | OR828281 | — | OR828335 | OR863466 | — | |

| Omphalina pyxidata | AMB:19294 | OR863534 | OR828282 | OR863591 | — | OR863467 | — | |

| Omphalina pyxidata | AMB:19295 | OR863535 | OR828283 | OR863592 | — | OR863468 | — | |

| Paralepista flaccida | KUN-HKAS:115937 | MZ853571 | MZ681894 | — | MZ857193 | MZ855885 | MZ857194 | |

| Paralepista flaccida | TO:AV20140410 | OR863536 | OR828284 | — | OR828336 | OR863469 | — | |

| Paralepistopsis amoenolens | AMB:18867 | OR863537 | OR828285 | — | OR828337 | OR863470 | — | |

| Pogonoloma spinulosum | K:M107286 | KJ417238 | KJ424401 | KU058571 | — | KP453705 | KU139037 | |

| Pseudoclitocybe cyathiformis | AFTOL-ID 1998, WTUJFA12811 + GLM46020 | EF551313 | GU187815 | GU187659 | GU 187742 | GU187553 | DQ067939 | |

| Pseudoclitopilus rhodoleucus | GB:0110967, TK03/203 | KJ417218 | KJ424393 | KU058577 | — | KP453696 | KU139046 | |

| Pseudoclitopilus rhodoleucus | KUN-HKAS:105563 | MZ714594 | MZ681899 | — | MZ681878 | MZ714588 | MZ681889 | |

| Pseudolaccaria pachyphylla | GB:0066637, LAS07/012 | KU058542 | KU139006 | KU058579 | — | KU058504 | KU139048 | |

| Pseudoomphalina kalchbrenneri | GB:0066625, LAS06/037 | KU058541 | KU139005 | KU058578 | — | KU058503 | KU139047 | |

| Pseudoomphalina umbrinopur-purascens | LSS20181215-2 | MK424271 | OR828292 | OR863598 | — | MK424270 | — | |

| Pseudotricholoma metapodium | AH22102006-K | KJ417219 | KJ424394 | KJ417171 | — | KJ417308 | KU139049 | |

| Rhizocybe alba | KUN-HKAS:55110 | MZ675571 | MZ681893 | — | MZ681871 | MZ675560 | MZ681882 | |

| Rhodophana stangliana | KUN-HKAS:115926 | MZ853562 | MZ852825 | — | MZ852801 | MZ855876 | MZ852813 | |

| Ripartites odorus | F. Di Rita 08-12-2018 | MN595290 | OR828295 | OR863599 | OR828346 | MN595290 | — | |

| Ripartites odorus | T. Clements 248705 | OR863544 | OR828294 | — | OR828345 | MK559718 | — | |

| Ripartites sp. | Kekki2112 | OR863545 | OR828296 | OR863600 | OR828347 | OR863478 | — | |

| Ripartites tricholoma | Kekki1910 | OR863546 | OR828297 | OR863601 | OR828348 | OR863479 | — | |

| Ripartites tricholoma | KUN-HKAS77956 | MZ675573 | — | — | MZ681873 | MZ675562 | MZ681884 | |

| Singerocybe umbilicata | KUN-HKAS:105572 | MZ714591 | MZ681896 | — | MZ681875 | MZ714585 | MZ681886 | |

| Trichocybe puberula | Ferisin11.3.2016-03 | OR863549 | OR828300 | OR863603 | OR828351 | OR863482 | — | |

| Tricholoma viridiolivaceum | TENN:063670, PDD:97890, PBM3093 | JF706317 | JF706319 | JF706318 | — | JF706316 | KU139072 | |

| Tricholomella constricta | HC84/75 | AF223188 | DQ825412 | DQ825434 | AF357036 | DQ825422 | ||

| Tricholosporum goniospermum | AR122, TUR:A209107 | MW367864 | KU559863 | KU559865 | — | KU559848 | — | |

| Tricholosporum guangxiense | HMJAU:59028 | OK377056 | OK625403 | OK377043 | OK625333 | OK377047 | — | |

| Typhulineae | Typhula erythropus | S:IO.14.123, UPS:IO.14.123 | KY224096 | MT242343 | — | MT242362 | MT232359 | — |

| Typhula gyrans | S:IO.14.103, UPS:IO.14.103 | KY224097 | MT242344 | — | MT242363 | MT232360 | MT242323 | |

| Typhula incarnata | S:IO.14.92, UPS:IO.14.92 +CBS:35979 | MT232313 | MT242346 | MT232504 | MT242365 | MT232362 | MT242325 | |

| Typhula sclerotioides | S:IO.14.22 | MT232317 | MT242349 | MT232507 | MT242369 | MT232365 | MT242327 |

Table 3.

Taxa, vouchers, and GenBank/Unite accessions numbers of the DNA sequences used in the Cuphophylloideae-wide phylogenetic analysis inferred from a four-gene dataset (ITS, LSU, RPB2 and TEF1). Sequences in bold were generated in this study.

| Species | Herbarium | ITS | LSU | RPB2 | TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampulloclitocybe clavipes | KUN-HKAS:54426 | MW616462 | MW600481 | MW656471 | MW656461 |

| TENN:DJL06TN40 | FJ596912 | KF381542 | KF407938 | — | |

| WTU:PBM2474, AFTOL-ID 542 | AY789080 | AY639881 | AY780937 | AY881022 | |

| Amylocorticium cebennense | CFMR:HHB-2808 | GU187505 | GU187561 | GU187770 | GU187675 |

| Cantharocybe brunneovelutina | CFMR:DJLBZ1883 - TYPE | NR_160458 | NG_068731 | — | — |

| Cantharocybe gruberi | AH:24539 | JN006422 | JN006420 | — | — |

| WTU:PBM510, AFTOL-ID 1017 | DQ200927 | DQ234540 | DQ385879 | DQ059045 | |

| Cantharocybe virosa | HKAS:79012 | — | KF303143 | — | — |

| TENN:063483 | KX452405 | JX101471 | — | — | |

| Ceraceomyces borealis | CFMR:L-8014 | — | GU187570 | GU187782 | GU187686 |

| Cuphophyllus acutoides var. pallidus | CFMR:TN-257 | KF291096 | KF291097 | — | — |

| Cuphophyllus aff. pratensis | WTU:PBM2752, AFTOL-ID 1682 | DQ486683 | DQ457650 | — | — |

| Cuphophyllus aurantius | CFMR:PR-6601 | KF291099 | KF291100 | KF291102 | — |

| Cuphophyllus cinerellus | GB:0156961, EL30-16 | MK573935 | MN430913 | MN556847 | — |

| Cuphophyllus esteriae | TU:117603 | MK547063 | MN430911 | MN556855 | — |

| Cuphophyllus flavipes | TUR:A-199692, Campo131027 | MN453872 | MN430919 | MN556851 | — |

| Cuphophyllus fornicatus | CFMR:D.Boertmann 2009/94 | KF291123 | KF291124 | — | — |

| Cuphophyllus hygrocyboides | GB:0156992, EL177-13 | MK573937 | MN430917 | MN534321 | — |

| Cuphophyllus lamarum | TU:117564 | MK547062 | MN430915 | MN556853 | — |

| Cuphophyllus pratensis | CFMR:DJL-Scot-8 | KF291057 | KF291058 | — | — |

| Lueck7 | — | KP965789 | — | — | |

| Cuphophyllus sp. | KUN-HKAS:105671 | MW762875 | MW763000 | MW789179 | — |

| Hygrophorocybe aff. carolinensis | UCSC:F0690 | OR863442 | OR863511 | OR828266 | OR828324 |

| Hygrophorocybe aff. carolinensis (as Clitocybe carolinensis) | TENN:021888 - TYPE | NR_119886 | — | — | — |

| Hygrophorocybe nivea | AMB:19292 | OR863444 | OR863512 | — | — |

| AMB:19293 | OR863445 | OR863513 | — | — | |

| LPA:SMGC2020121621 | OR863446 | OR863514 | OR828267 | OR828325 | |

| TO:AV20100811 | OR863448 | OR863516 | — | — | |

| TO:AV20112411 | OR863449 | OR863517 | — | — | |

| Hygrophorocybe nivea (as Clitocybe alni-glutinosae) | IB:19960896 - TYPE | UDB023989 | — | — | — |

| Hygrophorocybe nivea (as Clitocybe hypotheja) | MCVE:530 - TYPE | OR863443 | — | — | — |

| Spodocybe bispora | KUN-HKAS:112564 | MW762882 | MW763007 | MW789186 | MW773446 |

| KUN-HKAS:73310 - TYPE | MW762880 | MW763005 | MW789184 | MW773444 | |

| Spodocybe cf. trulliformis (as Clitocybe cf. trulliformis) | G0460, DB1302 | — | MK277728 | — | — |

| Spodocybe collina | AMB:19296 | OR863480 | OR863547 | OR828298 | OR828349 |

| WU:0018453, G0342 | — | MK277717 | — | — | |

| Spodocybe herbarum (as Clitocybe herbarum) | G0171, NL-2261 | — | MK277719 | — | — |

| Spodocybe rugosiceps | KUN-HKAS:112563 - TYPE | MW762888 | MW763013 | MW789192 | MW789160 |

| KUN-HKAS:71071 | MW762886 | MW763011 | MW789190 | MW773449 | |

| Spodocybe sp. | KUN-HKAS:112560 | MW762889 | MW763014 | MW789193 | MW789161 |

| KUN-HKAS:112565 | MW762890 | MW763015 | MW789194 | MW789162 |

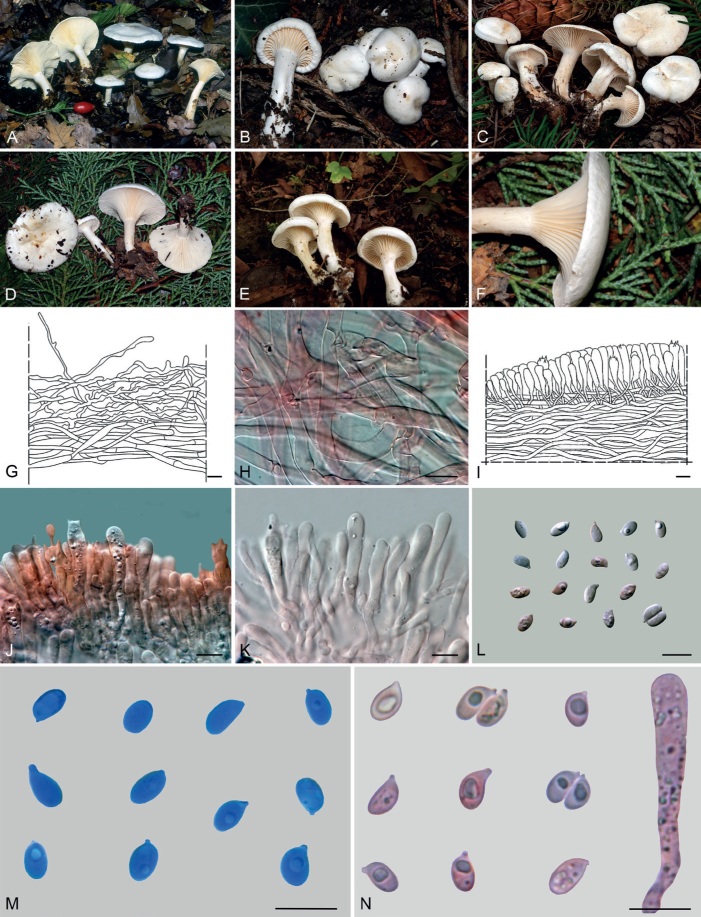

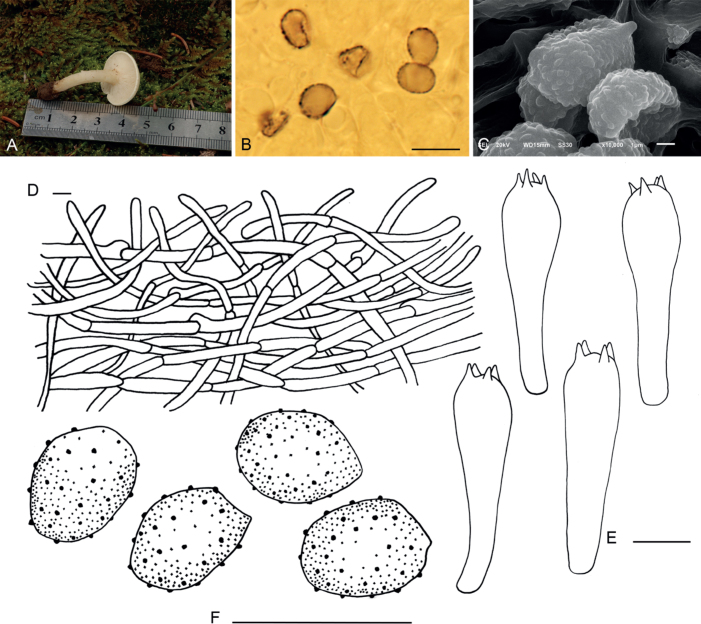

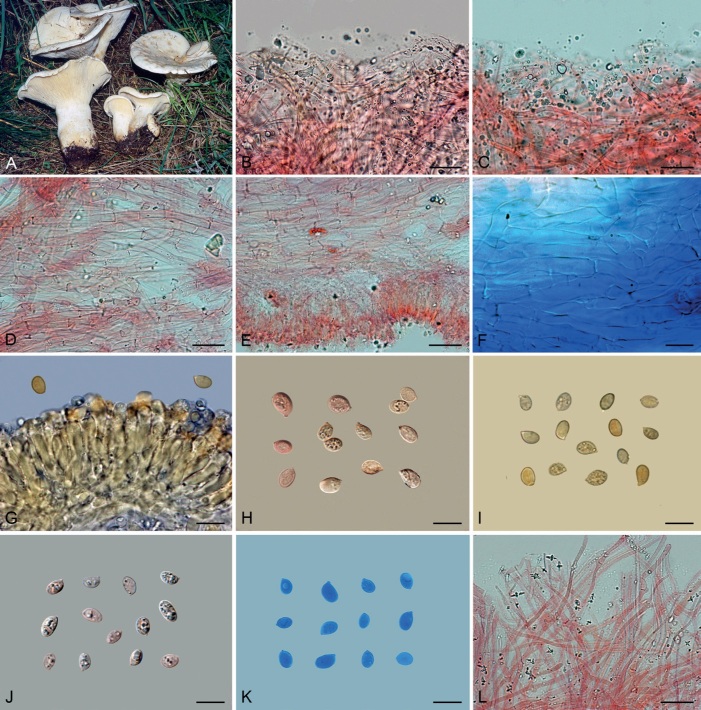

Fig. 6.

Basidiomes of taxa within Agaricales sequenced in the present work. A. Aphroditeola olida (HRL1230). B. Aspropaxillus giganteus (AMB:18858). C. Clitocybe ditopa (AMB:19311). D. Favolaschia claudopus (B. Child-Villiers 23-10-22). E. Fayodia bisphaerigera (OW241-19). F. Gamundia sp. (YM18172). G. Giacomia mirabilis [ANGE1598 (TO)]. H. Giacomia sinensis (HMJU:265 holotype). I. Heimiomyces aff. tenuipes (McAdoo 725). J. Hemimycena lactea (OULU:GAJ15636). K. Hertzogia martiorum (AMB:18863). L. Hygrophorocybe nivea (AMB:19292). M. Hygrophorocybe aff. carolinensis (UCSC:F0690). N. Infundibulicybe gibba (AMB:19313). O. Lepista glaucocana (AMB:18862). Photographs A by R. Lebeuf, B, C, K, L, N, O by G. Consiglio, D by B. Child-Villiers, E by Ø. Weholt, F by Y. Mourgues, G by C. Angelini, H by J. Xu, I by W. McAdoo, J by S. Huhmarniemi, M by C. Schwarz.

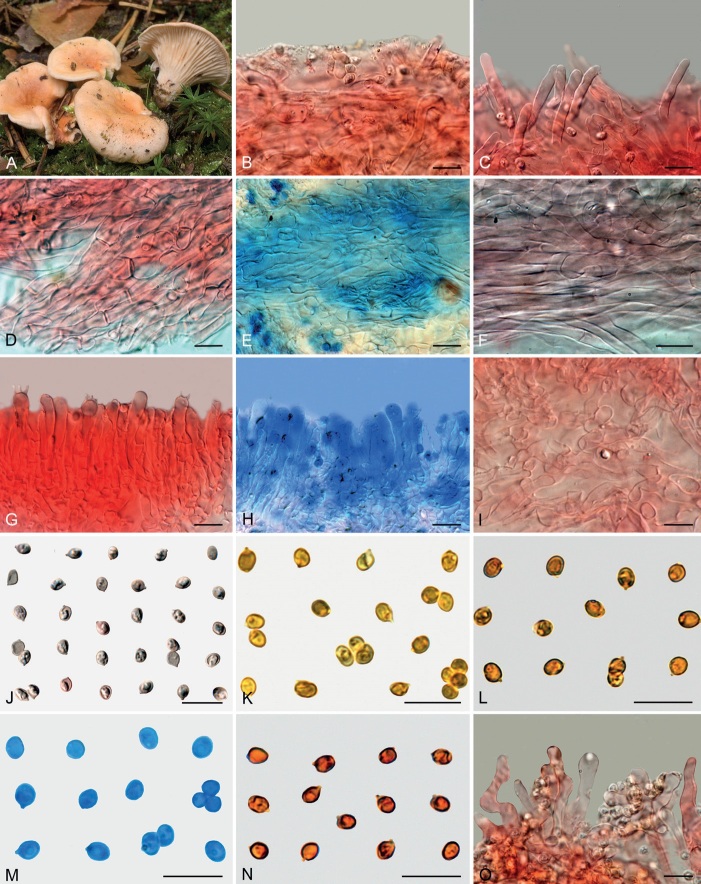

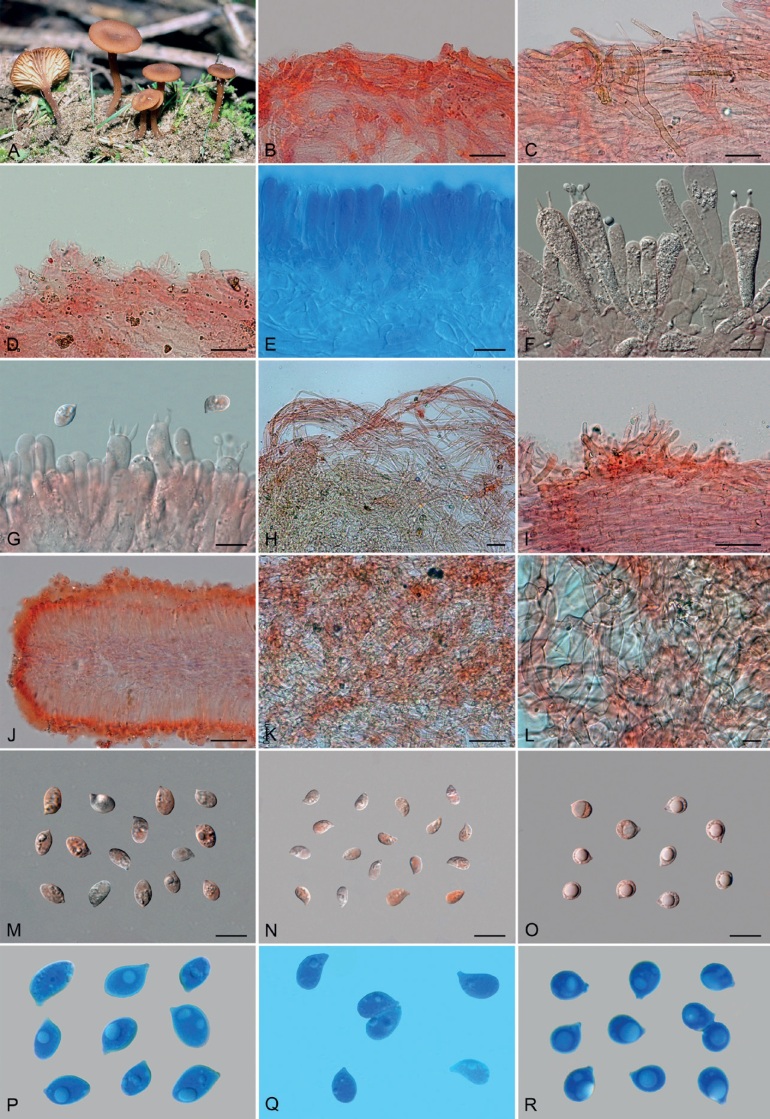

Fig. 8.

Basidiomes of taxa within Agaricales sequenced in the present work. A. Pseudoomphalina umbrinopurpurascens (LSS20181215-2). B. Resupinatus applicatus (AMB:18098). C. Ripartites odorus (F. Di Rita 08-12-2018). D. Ripartites tricholoma (Kekki1910). E. Spodocybe collina (AMB:19296). F. Tectella patellaris (McAdoo991). G. Trichocybe puberula (Ferisin11.3.2016-03). H. Volvariella bombycina (AMB:19312). I. Volvariella aff. nigrovolvacea (AMB:18775). J. Volvariella aff. pusilla (AMB:19290). K. Volvopluteus earlei (AGMT-71). L. Volvopluteus gloiocephalus (NTNU:27884555). Photographs A by L. Sánchez, B, E, H–J by G. Consiglio, C by M. Atzeni, D by T. Kekki, F by W. McAdoo, G by G. Ferisin, K by F. Giannoni, L by P.G. Larssen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

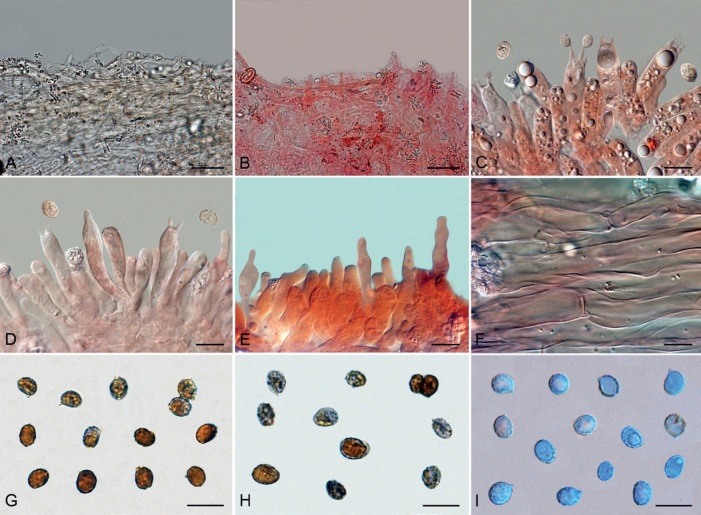

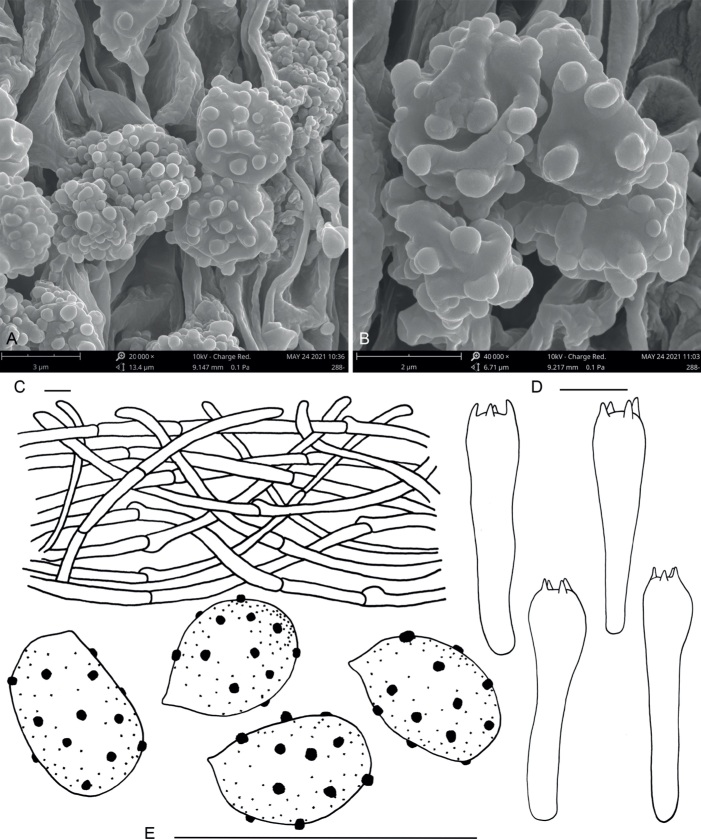

Morphological studies

Macroscopic morphological features were studied in fresh specimens. Colour codes follow Kornerup & Wanscher (1978). The following abbreviations are employed: L = number of lamellae reaching the stipe, l = number of lamellulae between each pair of lamellae. Microscopic structures were examined in dried material using different mounting media: water, L4 (Clémençon 1972), Melzer’s reagent, ammoniacal Congo red, phloxine, Cresyl blue and Cotton blue. Dried pieces of the samples were rehydrated in water and mounted in L4. All microscopic measurements were carried out with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope, using immersion oil at ×1 000. Spore measurements were taken by capturing images of a single visual field with multiple spores (obtained from lamellar squashes of exsiccate material of mature specimens) which were then measured using the DS-L1 Nikon camera control unit. Spore dimensions do not include the hilar appendix, and are reported as follows: (minimum–) average minus standard deviation of length–average of length–average plus standard deviation of length (−maximum) × (minimum–) average minus standard deviation of width–average of width–average plus standard deviation of width (−maximum); Q (ratio length/width) = (minimum–) average minus standard deviation–average–average plus standard deviation (−maximum); V (volume, μm3) = (minimum–) average minus standard deviation–average–average plus standard deviation (−maximum). The approximate spore volume was calculated as that of an ellipsoid (Gross 1972, Meerts 1999). The notation [n/m/p] indicates that measurements were made on ‘n’ randomly selected spores from ‘m’ basidiomes of ‘p’ collections. The width of the basidia was measured at the widest part, and the length was measured from the apex (sterigmata excluded) to the basal septum. Microscopy images were taken using a Nikon DS 5M digital connected to the microscope with both bright field and interferential contrast optics. Macro- and microchemical testing of pigments were performed using basic solutions (5 % KOH and 10 % ammonia, separately). In some cases, basidiospores were observed under the scanning electron microscope (SEM), using the following procedure: lamellae were attached to specimen holders by carbon tape, coated with platinum-palladium using a Hitachi MC 1000 Ion Sputter Coater and examined with a FEI Quanta 200 FE-SEM operated at 5–10 kV as in Xu et al. (2019). For nomenclatural matters, reference was made to the Shenzhen Code (Turland et al. 2018).

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from dry specimens (Table 1) employing a modified protocol based on Murray & Thompson (1980). Amplification reactions (Mullis & Faloona 1987) included 35 cycles with an annealing temperature of 54 ºC. The primers ITS1F and ITS4 (White et al. 1990, Gardes & Bruns 1993) were employed to amplify the internal transcribed spacer region 1, 5.8S rDNA and internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS), LR0R and LR5 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990, Cubeta et al. 1991) were used for the 28S rDNA region (LSU), NS19b and NS41 (Hibbett 1996) for the 18S rDNA (SSU), EF1-728F, EF1-983F, EF1-1567R and EF1-2218R (Carbone & Kohn 1999, Rehner & Buckley 2005) for the translation elongation factor-1a (TEF1) gene, bRPB2-6F2 (reverse of bRPB26R2), and bRPB2-7R2 for the DNA-directed RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) gene (Matheny et al. 2007), as well as RPB1-Af (Stiller & Hall 1997) and RPB1-Cr (Matheny et al. 2002) for DNA-directed RNA polymerase II largest subunit (RPB1) gene. The PCR products were checked in 1 % agarose gels, and amplicons were sequenced with one or both PCR primers. Sequences were corrected to remove reading errors in chromatograms using MEGA v. 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013).

Phylogenetic analyses

Three different datasets were built from sequences produced in the present work and others downloaded from public databases (Tables 1–3). Dataset 1 (Agaricales) aimed to resolve the phylogenetic relationships of the incertae sedis lineages studied with the different suborders of Agaricales. It included sequences of six different loci (5.8S, LSU, SSU, RPB1-exons, RPB2-exons, TEF1-exons) from the main lineages analyzed by Matheny et al. (2006), Varga et al. (2019), Ke et al. (2020), Olariaga et al. (2020) and Sánchez-García et al. (2020). Sequences of Amylocorticium cebennense and Ceraceomyces borealis (Amylocorticiales, Binder et al. 2010, Hodkinson et al. 2014, Zhao et al. 2017), as well as Suillus pictus (Boletales, Hodkinson et al. 2014, He et al. 2019) were employed as outgroup taxa. Dataset 2 (Hygrophorineae) aimed to provide a more accurate view of the major clades within suborder Hygrophorineae. This dataset included sequences of LSU, RPB2-exons (from which a small region of up to 57 bp with multiple insertions/deletions of codons was removed), and TEF1-exons from all specimens of Hygrophorineae in Dataset 1 (as well as A. cebennense and C. borealis as outgroups) plus additional lineages known to belong in this suborder (Lodge et al. 2014, He & Yang 2021). Finally, Dataset 3 (Cuphophylloideae) aimed to focus on species included in this subfamily, and employed sequences of ITS, LSU, RPB2-exons, and TEF1-exons (using A. cebennense and C. borealis again as outgroup taxa). Another two datasets of Agaricales including taxa of suborder Clavariineae (Dataset 4) or the family Cyphellopsidaceae (Dataset 5) were built too (same loci as Dataset 1), but they failed to produce significant support for several major clades of Agaricales, probably due to the insufficient information available from the linages included or missing lineages in the diversity analyzed. As a result, the phylogenetic trees obtained from them are provided as Supplementary Figs S1, S2 and their sequences are included in Table 1. Alignments of Datasets 1–5 are available online (https://figshare.com/; Dataset 1 – Agaricales: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24999359, Dataset 2 – Hygrophorineae: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24999371, Dataset 3 – Cuphophylloideae: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24999362, Dataset 4 – Clavariineae: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24999365, Dataset 5 – Cyphellopsidaceae: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24999368. Sequences newly generated in this study and their GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) accession numbers are shown in Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Table S1.

BLASTn (Altschul et al. 1990) was used to select related homologous sequences from the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration public database (INSDC, Arita et al. 2021) and UNITE (Nilsson et al. 2018). All sequences employed are listed in Table 1. Sequences were first aligned in MEGA v. 6.0 with its ClustalW application and then realigned manually as needed to establish positional homology. Dataset 1 (Agaricales) included the following partitions (variable sites/total sites/sequences): 53/158/209 (5.8S), 489/864/221 (LSU), 413/1 683/166 (SSU), 440/654/112 (RPB1), 629/999/203 (RPB2), and 548/960/183 (TEF1). Dataset 2 (Hygrophorineae) included the following partitions (variable sites/total sites/sequences): 416/792/100 (LSU), 344/660/63 (RPB2), and 171/472/26 (TEF1). Dataset 3 (Cuphophylloideae) included the following partitions (variable sites/total sites/sequences): 677/1 101/35 (ITS), 292/792/38 (LSU), 277/660/22 (RPB2), and 155/472/14 (TEF1). Aligned loci also were subjected to MrModeltest v. 2.3 (Nylander 2004) in PAUP v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003). Model GTR+G+I was selected and implemented in all partitions in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. 2012), where a Bayesian analysis was performed (each locus analyzed in a different partition, two simultaneous runs, four chains, temperature set to 0.2, sampling every 1 000th generation) until the average split frequencies between the simultaneous runs fell below 0.01 after 16.39 M (Agaricales), 2.01 M (Hygrophorineae) and 0.25 M (Cuphophylloideae) generations, respectively. Finally, a full search for the best-scoring maximum likelihood tree was performed in RAxML v. 8.2.12 (Stamatakis 2014) using the standard search algorithm (same partitions, GTRCAT model, 2 000 bootstrap replications). All the analyses were run through the CIPRES Science Gateway platform (Miller et al. 2010). The significance threshold was set above 0.95 for posterior probability (PP) and 70 % bootstrap proportions (BP).

RESULTS

DNA phylogeny

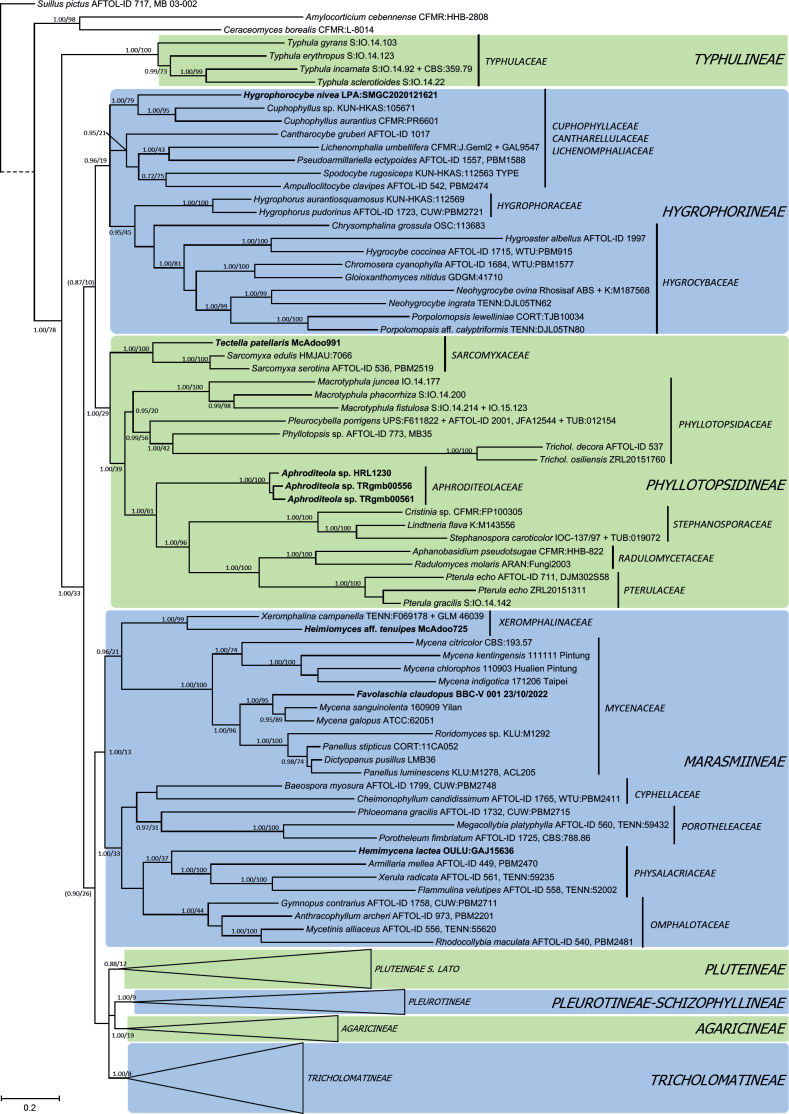

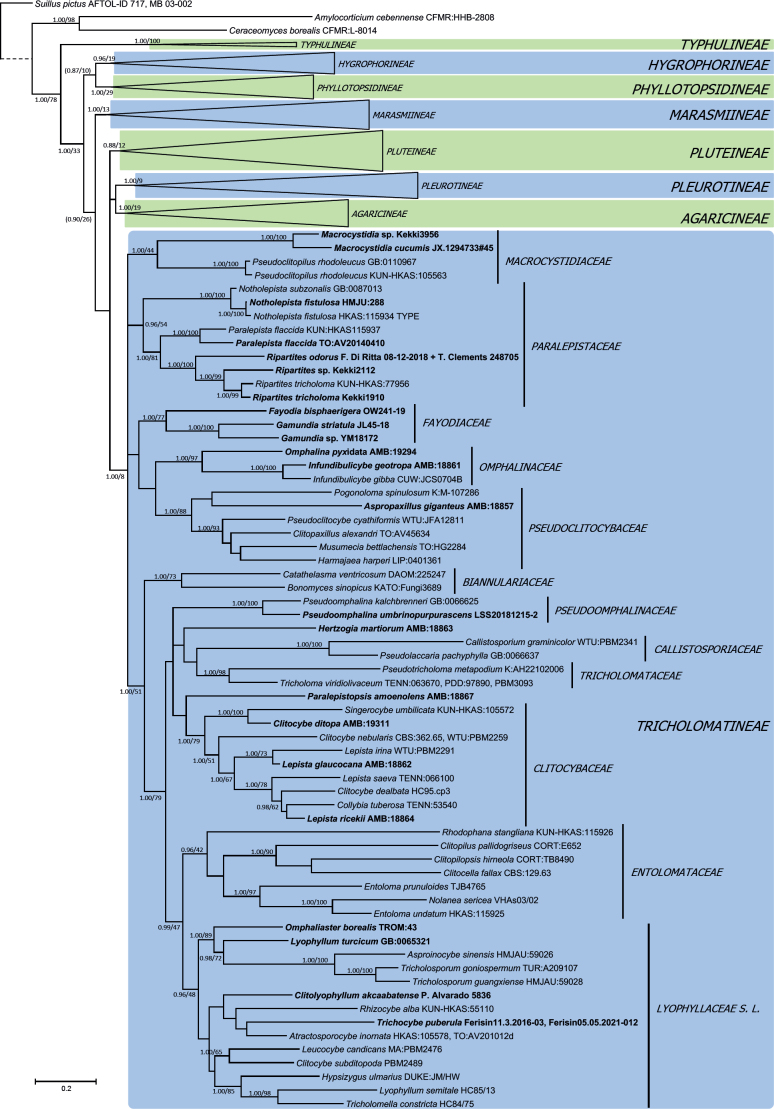

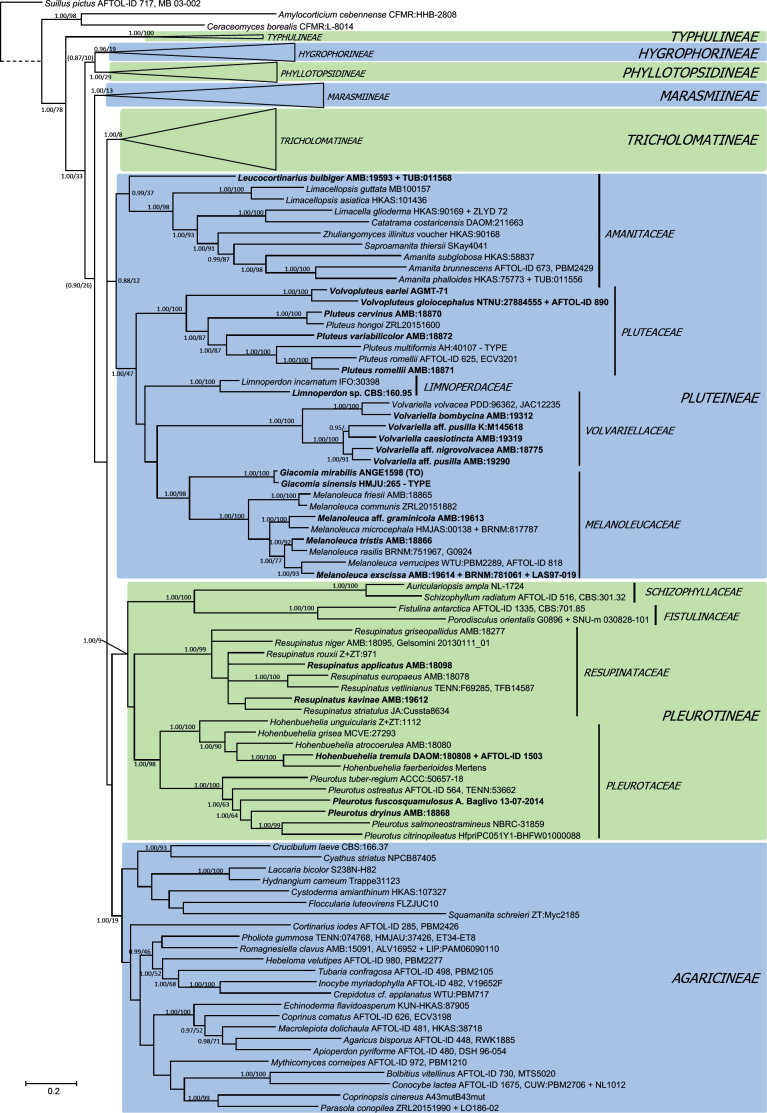

Bayesian analysis of Dataset 1, order Agaricales (Figs 1–3), significantly supported the following hypotheses: 1) family Typhulaceae has a basal position to the remaining suborders analyzed; 2) seven main clades with a significant monophyletic origin were found, matching suborders Agaricineae, Pleurotineae (including Schizophyllineae), Pluteineae, Hygrophorineae, Marasmiineae, Phyllotopsidineae (including Aphroditeola and Sarcomyxineae) and Tricholomatineae; 3) suborder Pleurotineae also encompasses the families Fistulinaceae and Schizophyllaceae, and so it could be considered a synonym of Schizophyllineae; 4) suborder Pluteineae includes Amanitaceae and Leucocortinarius (PP 0.99), as well as the families Pluteaceae, Limnoperdaceae, a strongly supported clade (1.00 PP, 98 % BP) consisting of Melanoleuca and Giacomia, and another including Volvariella; 5) suborder Tricholomatineae has at least twelve families: Macrocystidiaceae (type Macrocystidia, probably related to Pseudoclitopilus); Omphalinaceae (including Infundibulicybe and Omphalina), Pseudoclitocybaceae (including Aspropaxillus), Fayodiaceae (here including Fayodia and Gamundia, but probably also Caulorhiza, Conchomyces and Myxomphalia according to Moncalvo et al. 2002); Biannulariaceae, Callistosporiaceae, Tricholomataceae, Clitocybaceae, Lyophyllaceae sensu lato, Entolomataceae, as well as the unclassified lineages of Neohygrocybe/Pseudoomphalina, Paralepistopsis, Hertzogia and the clade formed by Notholepista, Ripartites, and Paralepista; 6) family Clitocybaceae includes the genera Clitocybe sensu stricto, Lepista, Singerocybe, Collybia sensu lato (He et al. 2023), and the lineage of C. ditopa; 7) family Lyophyllaceae sensu lato is integrated by Lyophyllaceae sensu stricto as well as the so-called hemilyophylloid lineages (Binder et al. 2010, Hofstetter et al. 2014), including the genera Asproinocybe/Tricholosporum (family Asproinocybaceae), Atractosporocybe, Clitolyophyllum, Leucocybe, Omphaliaster, Rhizocybe, Trichocybe, and several species whose generic status needs to be reviewed; 8) family Mycenaceae is part of the suborder Marasmiineae, where it is sister to the significant clade formed by Xeromphalina and Heimiomyces; 9) the previous concepts of the genera Mycena and Hemimycena are polyphyletic; 10) genus Hygrophorocybe is nested inside suborder Hygrophorineae.

Fig. 1.

Bayesian inference phylogram built with nucleotide sequence data of six loci (5.8S, LSU, SSU, RPB1-exons, RPB2-exons and TEF1-exons) of the main lineages inside order Agaricales (focused on suborders Hygrophorineae, Marasmiineae and Phyllotopsidineae), rooted with Suillus pictus (Boletales), Amylocorticium cebennense and Ceraceomyces borealis (Amylocorticiales) as outgroups. The main suborders are shown in color boxes, while family names are shown next to vertical bars. Nodes were annotated with Bayesian PP (left) and ML BP (right) values, with the significance threshold considered as Bayesian PP >0.95 and/or ML BP >70 %. Subsignificant support values were annotated in parentheses. Boldface names represent samples sequenced for this study. The dashed branch was shortened for graphic presentation.

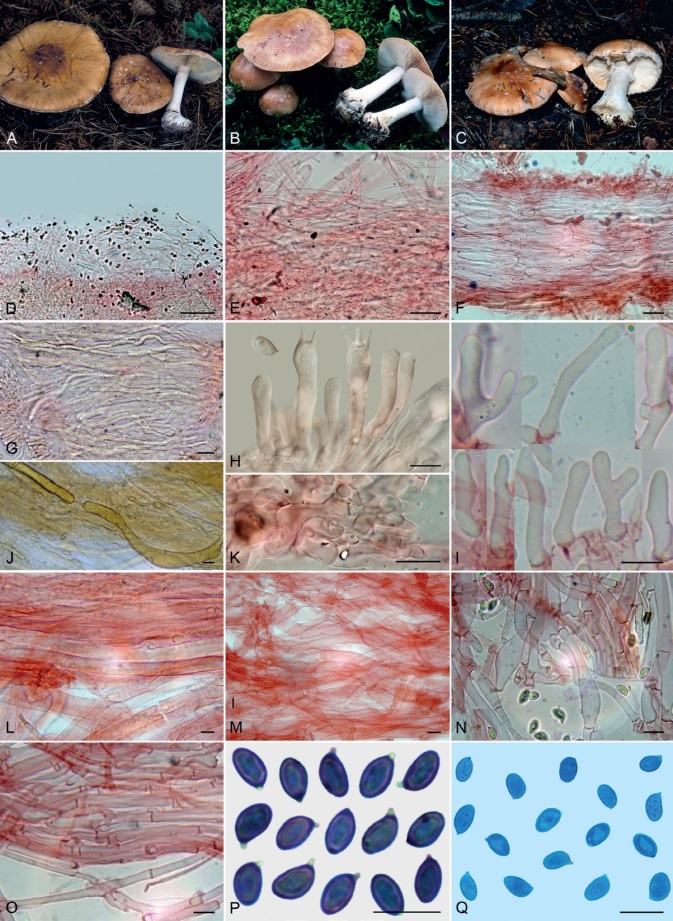

Fig. 3.

Bayesian inference phylogram built with nucleotide sequence data of six loci (5.8S, LSU, SSU, RPB1-exons, RPB2-exons and TEF1-exons) of the main lineages inside order Agaricales (focused on suborder Tricholomatineae), rooted with Suillus pictus (Boletales), Amylocorticium cebennense and Ceraceomyces borealis (Amylocorticiales) as outgroups. The main suborders are shown in color boxes, while family names are shown next to vertical bars. Nodes were annotated with Bayesian PP (left) and ML BP (right) values, with the significance threshold considered as Bayesian PP >0.95 and/or ML BP >70 %. Subsignificant support values were annotated in parentheses. Boldface names represent samples sequenced for this study. The dashed branch was shortened for graphic presentation.

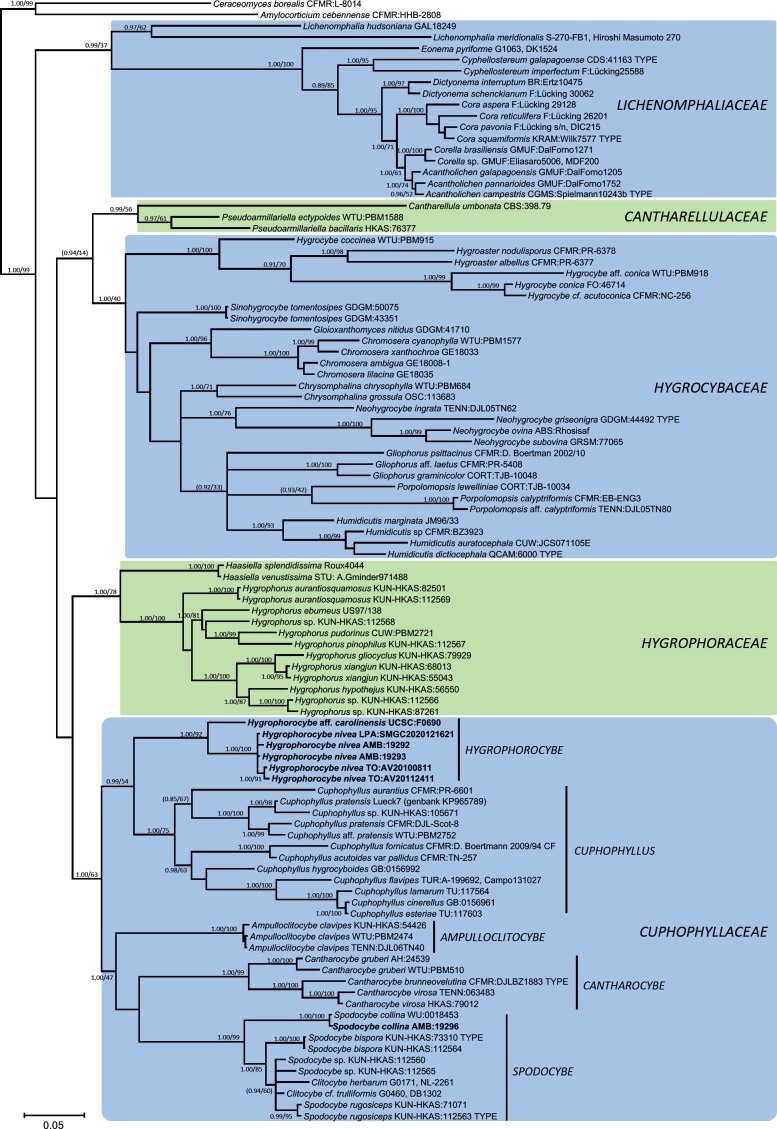

The Bayesian analysis of Dataset 2, the extended dataset of suborder Hygrophorineae (Fig. 4), supported the following five major monophyletic clades: 1) subfamily Lichenomphalioideae; 2) subfamily Hygrocyboideae, 3) tribe Cantharelluleae, 4) subfamily Hygrophoroideae, and 5) subfamily Cuphophylloideae, which includes the genera Ampulloclitocybe, Cantharocybe, Cuphophyllus, Hygrophorocybe (including Clitocybe aff. carolinensis) and Spodocybe.

Fig. 4.

Bayesian inference phylogram built with nucleotide sequence data of three loci (LSU, RPB2-exons and TEF1-exons) of the main lineages inside suborder Hygrophorineae rooted with Amylocorticium cebennense and Ceraceomyces borealis (Amylocorticiales) as outgroups. The main families are shown in color boxes, while generic names are shown next to vertical bars. Nodes were annotated with Bayesian PP (left) and ML BP (right) values, with the significance threshold considered as Bayesian PP >0.95 and/or ML BP >70 %. Subsignificant support values were annotated in parentheses. Boldface names represent samples sequenced for this study.

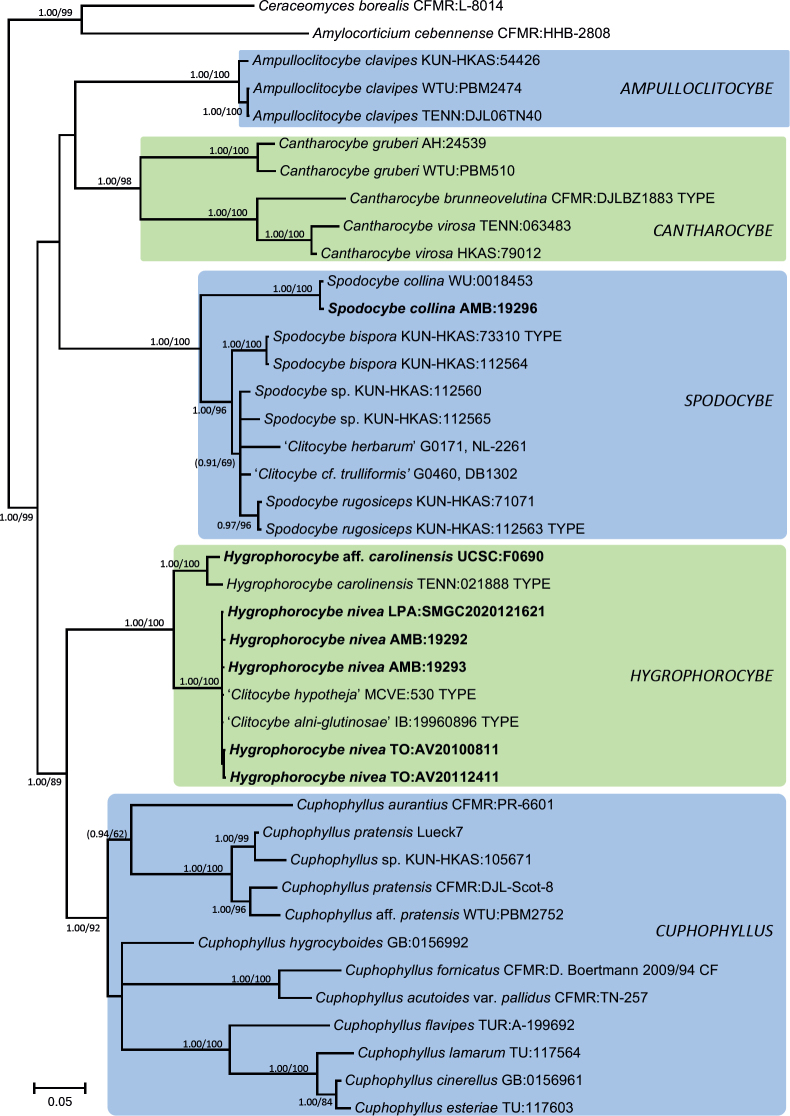

The Bayesian analysis of Dataset 3, the extended dataset of subfamily Cuphophylloideae (Fig. 5), supported the same hypotheses as Fig. 4. The analysis of ITS rDNA allowed also to infer that the holotype collections of Clitocybe alni-glutinosae and C. hypotheja are identical to that of Hygrophorocybe nivea and confirmed that the holotype of C. carolinensis belongs to another clade of Hygrophorocybe.

Fig. 5.

Bayesian inference phylogram built with nucleotide sequence data of four loci (ITS, LSU, RPB2-exons and TEF1-exons) of the main lineages inside family Cuphophyllaceae rooted with Amylocorticium cebennense and Ceraceomyces borealis (Amylocorticiales) as outgroups. The main genera are shown in color boxes. Nodes were annotated with Bayesian PP (left) and ML BP (right) values, with the significance threshold considered as Bayesian PP >0.95 and/or ML BP >70 %. Subsignificant support values were annotated in parentheses. Boldface names represent samples sequenced for this study.

The taxo nomy of all these lineages is updated below in accordance with the results obtained from phylogenetic analysis.

Taxonomy

Agaricales Underw., Moulds, mildews, and mushrooms: 97. 1899.

Synonyms: Agarics, Euagarics, Euagarics clade, Euagaricoid clade sensu Hibbett et al. (1997), Pine et al. (1999), Moncalvo (2000, 2002), Hibbett & Binder (2001), Hibbett & Thorn (2001), Redhead et al. (2002a, b), Bodensteiner et al. (2004), Larsson et al. (2004), Binder et al. (2005), Walther et al. (2005), Wilson & Desjardin (2005), Garnica et al. (2007).

Type: Agaricus L., Species Plantarum 2: 1171. 1753.

Representative suborders: Agaricineae, Clavariineae, Hygrophorineae, Marasmiineae, Phyllotopsidineae, Pluteineae, Pleurotineae, Tricholomatineae, and Typhulineae.

Notes: There is no known morphological synapomorphy that unites the order Agaricales. This lineage evolved into several basidiome types, from resupinate (corticioid) to conchate, cyphelloid, stereoid, clavarioid, agaricoid (pileostipitate, with open or enclosed hymenophore), and gasteroid/sequestrate (epigeous or hypogeous). Pileostipitate forms with protective veils (universal and partial) and lamellate hymenophore are the most frequent, but hymenophores can also be smooth, wrinkled, odontoid or poroid. The sequestrate forms show locules, and a columella (vestigial structure of the stipe) can be present, reduced, or absent. The hyphal system is mainly monomitic, with or without clamp connections, rarely dimitic or sarcodimitic. Basidia are holobasidiate, chiastic, usually sterigmate, ballistosporic (when the hymenophore is very early exposed to air) or statismosporic (in gasteroid/sequestrate epigeous to hypogeous forms). Basidiospores are extremely diverse with regards to their shape, wall thickness, colour in mass (white, pink, brown, purplebrown, black), ornamentation, and reactivity, sometimes being dextrinoid/amyloid (Melzer’s reagent), metachromatic (Cresyl blue), or cyanophilous (Cotton blue). Cystidia, pseudocystidia, setae and other sterile elements (acanthocytes, stephanocytes) may be present in the hymenium, pileus and stipe surface and basal mycelium. An asexual morph phase is sometimes present, conidiogenesis mainly thallic, rarely blastic. Dolipores are usually provided with perforate parenthesomes. For a delimitation of Agaricales see Matheny et al. (2006), Dentinger et al. (2016), (Agerer 2018), He et al. (2019), and Olariaga et al. (2020). Agaricales species are mostly ectomycorrhizal (mainly associated with the roots of conifers and dicotyledons), saprotrophic (decaying leaf litter, plant debris, and decaying wood, and include coprophilous, humicolous, and lignicolous species), or parasitic (red algae, plants, including some important phytopathogens), while endophytic and lichenized lifestyles are less frequent (Hibbett & Thorn 2001, Oberwinkler 2012, Agerer 2018). A few species are nematode-trapping or form mutualistic symbiosis with ants and termites (Money 2016, Agerer 2018, Kalichman et al. 2020). The vast majority of Agaricales is terrestrial, found in almost any habitat, from woods and grasslands to deserts and dunes (Kusuma et al. 2021), only a few taxa are known for freshwater (Desjardin et al. 1995, Frank et al. 2010, Abdel-Aziz 2016) or marine environments (Hibbett & Binder 2001, Binder et al. 2006, Jones et al. 2015, 2019, Abdel-Wahab et al. 2019). Lignicolous Agaricales are mainly associated with white rot (Worrall et al. 1997). Brown rot is a rare feeding strategy in Agaricales, associated with small genera such as Hypsizygus and Ossicaulis (Redhead & Ginns 1985). An unusual intermediate wood decomposition type was recently detected in the polyporoid Fistulina and corticioid Cylindrobasidium (Floudas et al. 2015). Enzymes secreted by Agaricales fungi responsible for wood rot are highly relevant to carbon and nutrient cycling in nature play important roles in maintaining environmental balance (Yang et al. 2017, Ruiz-Dueñas et al. 2020, Floudas et al. 2020, Sánchez-Ruiz et al. 2021). Toxic secondary metabolites as amatoxins, psilocybin, muscarine and oxazole compounds which can lead to poisoning in humans are produced mainly by taxa in Agaricineae, Pluteineae and Tricholomatineae (Enjalbert et al. 2002, Sgambelluri et al. 2014, Lee et al. 2018, Luo et al. 2018, Reynolds et al. 2018, Lüli et al. 2019, Sarawi et al. 2022, He et al. 2023). By now, about 25 400 species have been ascribed to the order Agaricales (Bánki et al. 2023), which contains 684 genera, including at least nine extinct (fossil) taxa (Hibbett et al. 2003, Poinar 2016, Cai et al. 2017, Heads et al. 2017), clustered in 45 families (Catalogue of Life, https://www.catalogueoflife.org/).

Agaricales is sister to Amylocorticiales (Binder et al. 2010, Hodkinson et al. 2014, Dentinger et al. 2016, Zhao et al. 2017, He et al. 2019, Sánchez-García et al. 2020, Li et al. 2021, Liu et al. 2023) together forming the superorder Agaricanae (Agerer 2018). Amylocorticiales consists mainly of lignicolous saprotrophic fungi with predominantly resupinate, rarely effuse-reflexed, cupulate or flabellate basidiomes with smooth, wrinkled to tuberculate, rarely tubulose hymenophore (Binder et al. 2010, Garnica et al. 2021). Agaricanae and “Boletanae ad int.” (composed of Boletales and Atheliales; Agerer 2018) form the subclass Agaricomycetidae of the class Agaricomycetes. Jaapiales was proposed in Agaricomycetidae based on multigene data (Binder et al. 2010), but later placed outside it by Li et al. (2021) based on genomic data.

Agaricineae Fr. [as ‘Agaricini’], Syst. orb. veg. (Lundae) 1: 65 (1825) emend. Aime et al., Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 117: 27. 2016.

Representative families: Agaricaceae (including Coprinaceae, Lycoperdaceae, Podaxaceae and Tulostomataceae), Bolbitiaceae, Cortinariaceae, Crassisporiaceae, Crepidotaceae, Galeropsidaceae, Hydnangiaceae, Hymenogastraceae (including Chromocyphellaceae), Inocybaceae, Mythicomycetaceae, Nidulariaceae, Psathyrellaceae, Squamanitaceae, Strophariaceae, and Tubariaceae.

Notes: Saprotrophic (Singer 1986), some associated with rodent latrines (ammonia-fungi or post-putrefaction fungi, Hymenogastraceae, Psathyrellaceae, Sagara 1975, 1995, Sagara et al. 2000, Suzuki 2009), ECM (ectomycorrhizal) forming (Cortinariaceae, Hydnangiaceae, Hymenogastraceae and Inocybaceae; Rinaldi et al. 2008, Tedersoo et al. 2010, Tedersoo & Smith 2013, Soop et al. 2016), arbutoid mycorrhizas forming (Smith & Read 2008, Kühdorf et al. 2016), leaf cutting ants associated (Leucoagaricus, Fisher et al. 1994, Araújo et al. 2022, Urrea-Valencia et al. 2023), nematode hunters (nematophagy, Vizzini 2008) or mycoparasitic (Squamanita, Dissoderma, Psathyrella epimyces; Redhead et al. 1994, Liu et al. 2021, Saar et al. 2022). A previously unknown ectomycorrhizal relationship between poplar roots and Bovista limosa (Agaricaceae) was recently described by Xiao et al. (2023a). The Agaricineae emend. Aime et al. represents one of the seven suborders of Agaricales identified by Dentinger et al. (2016) using a phylogenomic approach and later confirmed in different works, i.e., Varga et al. (2019), Olariaga et al. (2020), Li et al. (2021), Wang et al. (2023b). This suborder corresponds to the “Agaricoid” clade found in previous works (Matheny et al. 2006, 2015, Garnica et al. 2007, Binder et al. 2010, Kohler et al. 2015). The present results agree with recent studies focusing on relationships at the family level within Agaricineae, i.e., Matheny et al. (2015), Vizzini et al. (2019a) or Liu et al. (2021). Many species in Agaricineae show pigmented and/or thick-walled spores (Matheny et al. 2006, 2015, Garnica et al. 2007, Vizzini et al. 2019a). Although species producing dark-pigmented spores (dark-pigmented agarics) are present in a few other lineages (e.g., Melanomphalia, Hygrophorineae, Lichenomphaliaceae, Aime et al. 2005 or Ripartites, Tricholomatineae, Paralepistaceae, see below), the overwhelming majority of these have evolved within Agaricineae. The presence of basidiospores with a thickened, dark-pigmented wall, and occasionally also germ pores, is probably indicative of adaptations to survive harsh conditions in specialised environments (e.g., dung, burnt sites) (Watling 1988, Garnica et al. 2007, Halbwachs et al. 2015, Halbwachs & Bässler 2021). As pigmentation and thick walls are necessary, for example, to the basidiospores of coprophilous species to survive harsh conditions in digestive systems of animals but reduce their germination capability, the germ pore is suggested facilitating germination providing a preferential thin-walled spot where the germ tube can force its way through the tough spore wall (Watling 1988, Halbwachs et al. 2015, Halbwachs & Bässler 2021). In the taxa with asexual morphs, thallic conidiogenesis is the most frequent (Watling 1979, Pantidou et al. 1983, Buchalo 1988, Walther et al. 2005, Walther & Weiß 2006).

Clavariineae Olariaga et al., Stud. Mycol. 96: 171. 2020.

Type: Clavaria Vaill. ex L., Species Plantarum 2: 1182. 1753.

Representative family: Clavariaceae.

Notes: Suborder Clavariineae is characterized by clavarioid basidiomes (Ceratellopsis, Clavaria, Clavicorona, Clavulinopsis, Hirticlavula, Holocoryne, Ramariopsis), more rarely agaricoid, gymnocarpic with waxy hygrophoroid decurrent lamellae (Camarophyllopsis, Hodophilus, Lamelloclavaria), hydnoid (Mucronella) or corticioid (Hyphodontiella). Hyphal system monomitic, or more rarely dimitic. Basidiospores colourless, usually thin-walled, smooth or ornamented, usually with multiguttulate contents, sometimes with amyloid or dextrinoid reactions. Basidia claviform, with up to four sterigmata, occasionally sometimes with a loop-like (medallion) basal clamp (Clavaria subgen. Holocoryne). Cystidia usually absent. Pileipellis either a hymeniderm or a trichoderm with rounded terminal elements in genera with pileostipitate basidiomes. Clamp connections present or absent, sometimes restricted to basidia. Saprotrophic on dead wood, herbaceous plants, or leaves, or biotrophic with grasses and bryophyte gametophytes (Birkebak 2015, Birkebak et al. 2013, 2016). The presence of TEF1 intron 21 (numbering according to Matheny et al. 2007), absent in the rest of the Agaricales (Matheny et al. 2007), seems so far restricted to some genera of Clavariaceae (Camarophyllopsis, Clavaria, Clavulinopsis; absent in Ceratellopsis).

The traditional concept of the family Clavariaceae as circumscribed by Corner (1950, 1970), Thind (1961), Parmasto (1965), Jülich (1984), and Petersen (1988) was later expanded upon by several authors based on the results of DNA-based phylogenetic analyses. The family Clavariaceae was first shown to have affinities with the Agaricales by Pine et al. (1999) using nuclear and mitochondrial rDNA loci. Clavaria fusiformis (now Clavulinopsis) was apparently near to the /tricholomopsis clade and sister to the /hemimycena clade in Moncalvo et al. (2002). Clavaria, Clavulinopsis, Mucronella and Ramariopsis were found to be monophyletic by Larsson et al. (2004) and Dentinger & McLaughlin (2006). Matheny et al. (2006) demonstrated that the gilled pileate-stipitate genus Camarophyllopsis belongs in the Clavariaceae, and not inside the Hygrophoraceae as suggested by Hesler & Smith (1963), Arnolds (1974a, b, 1986), Kühner 1980, Singer (1986), Kovalenko (1989), Young (1999, 2005), and Boertmann (2002). The resupinate wood-inhabiting genus Hyphodontiella was shown to belong in the Clavariaceae too by Larsson (2007). Kautmanová et al. (2012a) included in their phylogenetic analysis of Clavariaceae the type of Clavaria (C. fragilis), confirming the previous assumptions. The genera Hodophilus (gilled) and Clavicorona (clavarioid) were also shown to be members of the Clavariaceae by Birkebak et al. (2013); and so was the clavarioid Hirticlavula by Petersen et al. (2014), the clavarioid Holocoryne, the gilled Lamelloclavaria by Birkebak et al. (2016), and the clavarioid Ceratellopsis emended by Olariaga et al. (2020).

As regards the phylogenetic placement of the family, members of Clavariaceae were considered incertae sedis for a long time by Pine et al. (1999), Moncalvo et al. (2002), Larsson et al. (2004), Larsson (2007), and in Lodge et al. (2014). In subsequent analyses, Clavariaceae was found to be an early diverging basal clade of Agaricales, either showing an isolated position (e.g., Binder et al. 2010, Sánchez-García et al. 2020, Olariaga et al. 2020) or related to Atheliaceae p.p. (Plicaturopsidoid clade, Matheny et al. 2006), or Hygrophoraceae (Ryberg & Matheny 2011, Dentinger et al. 2016, Varga et al. 2019). Based on a more diverse dataset, Olariaga et al. (2020) established suborder Clavariineae inside the order Agaricales, although most species were represented only by ribosomal DNA (LSU) sequences. Suborder Clavariineae was removed from the present analysis to avoid adding too much phylogenetic noise from a clade already shown to be basal to the remaining ones (Olariaga et al. 2020, Wang et al. 2023b), and because of the incomplete information available in databases (i.e., multigene data of Hirticlavula or Hyphodontiella are not available). However, additional analyses (Supplementary Fig. S1) agree to place Clavariineae in an early branching (basal) clade not related to any other in the dataset employed.

Hygrophorineae Aime et al., Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 117: 26. 2016.

Synonyms: Hygrophorales Bon, Flore mycologique d’Europe 1: 87. 1990.

Hygrophorales Locq., Mycol. Gén. Struct. (Paris): 98. 1984, nom. inval., Art. 39.1 (Shenzhen).

Type: Hygrophorus Fr., Fl. Scan.: 339. 1836. [1835].

Representative families: Cantharellulaceae, Cuphophyllaceae, Hygrocybaceae, Hygrophoraceae, and Lichenomphaliaceae.

Notes: Hygrophorineae is characterized by basidiomes primarily agaricoid, hymenophore predominantly lamellate, occasionally smooth, wrinkled or forked, often pigmented with L-DOPA betalains or carotenoids, and waxy; spore deposit white or rarely lightly pigmented (ochraceous, salmon, green); hyphae monomitic, usually with clamp connections; cystidia normally absent; basidia normally 2–4-sporic, mean ratio of basidia to basidiospore length 3–7; basidiospores colourless, predominantly inamyloid; terricolous, lignicolous, bryicolous, pteridicolous, saprotrophic, rarely parasitic on mosses, or symbiotic and then lichen-forming with cyanobacteria and/or green algae or ectomycorrhizal.

To treat the major monophyletic clades within Hygrophorineae (Fig. 4) at the same level as those of the other suborders, the main clades (four subfamilies and one tribe) recovered by Lodge et al. (2014) and He & Yang (2021) within Hygrophoraceae are here upgraded to the rank of independent families. As a result, five families are recognized in the present work inside Hygrophorineae (see below).

Hygrophoraceae Lotsy, Vortr. Bot. Stammesgesch. 1: 705. 1907. Perhaps based on Hygrophorées Roze, Bull. Soc. Bot. France 23: 110. 1876, nom. inval., Art. 32.1(b); see Art. 18.4 (Shenzhen).

Representative genera: Haasiella and Hygrophorus.

Notes: Hygrophoraceae is characterized by gymnocarpous or secondarily mixangiocarpous basidiomes; lamellae subdecurrent to deeply decurrent; trama inamyloid; hymenophoral trama divergent (hyphae diverging from a central strand), or bidirectional (horizontal hyphae that are parallel to the lamellar edge present, sometimes woven through vertically oriented, regular or subregular generative hyphae that are confined or not to a central strand) and a pachypodial structure below the active hymenium; basidiospores thin- or thick-walled, inamyloid, metachromatic or not, colorless or lightly pigmented (ochraceous, salmon, green); pigments muscaflavin (betalain) or carotenoids; habit terricolous (ectomycorrhizal, Hygrophorus) or xylophagous (saprotrophic, Haasiella) (Tedersoo et al. 2010, Seitzman et al. 2011, Lodge et al. 2014, Feng & Yang 2019). The phylogenetic affinities of Haasiella with Hygrophorus (Fig. 4) had already been previously highlighted by Vizzini et al. (2012b), Lodge et al. (2014), He & Yang (2021) and Wang et al. (2023a). The genus Aeruginospora (typified with A. singularis) is probably closely related to Haasiella based on their morphology: a similar basidiome form, bidirectional hymenophoral trama, a thickening hymenium forming a pachypodial structure, and spores that are thick-walled, pigmented, and with a red metachromatic endosporium (Lodge et al. 2014).

Hygrocybaceae (Padamsee & Lodge) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, stat. nov. & comb. nov. MycoBank MB 851141.

Synonym: Hygrophoraceae subfamily Hygrocyboideae Padamsee & Lodge, Fungal Diversity 64: 19. 2013. [2014].

Type: Hygrocybe (Fr.) P. Kumm., Führ. Pilzk. (Zwickau): 111. 1871. Synonym: Hygrophorus subg. Hygrocybe Fr., Summa veg. Scand., Section Post. (Stockholm): 308. 1849.

Representative genera: Chromosera, Chrysomphalina, Gliophorus, Gloioxanthomyces, Humidicutis, Hygrocybe (Hygroaster included), Neohygrocybe, Porpolomopsis, and Sinohygrocybe.

Notes: The circumscription of the family Hygrocybaceae is similar to those outlined by Lodge et al (2014), Wang et al. (2018) and He & Yang (2021) for Hygrophoraceae subfamily Hygrocyboideae except for the position of Chrysomphalina (typified with C. chrysophylla), which was included in Hygrophoraceae subfamily Hygrophoroideae by these latter authors and recently by Wang et al. (2023a). Our analysis (Fig. 4) indicated Chrysomphalina as part of Hygrocybaceae. Prior to the first sequencing and phylogenetic analyses of Haasiella, Redhead et al. (2002a) postulated a close relationship between this genus and Chrysomphalina based on pigments and micromorphology, although Kost (1986) disagreed based on the micromorphology. Clémençon (1982) combined Chrysomphalina grossula into Camarophyllus (subg. Aeruginospora) owing to the similar structure of their hymenophoral trama. Romagnesi (1996) included Haasiella and Phyllotopsis along with the type, Chrysomphalina, in his tribe Chrysomphalineae (invalidly published before that as tribe Paracantharelleae, Romagnesi 1995) due to the presence of carotenoid pigments in all of them. Hygrocybaceae is characterized by basidiomes with colors usually bright, rarely dull; lamellae, usually thick, yielding a waxy substance when crushed, rarely absent; true veils lacking, rarely with false peronate veils formed by fusion of the gelatinous ixocutis of the pileus and stipe, and fibrillose partial veils formed by hyphae emanating from the lamellar edge and stipe apex; basidiospores thin-walled, guttulate, colourless (though species with black staining basidiomes may have fuscous inclusions), smooth or ornamented by conical spines, inamyloid, usually acyanophilous; basidia guttulate, mono- or dimorphic; pleurocystidia absent; pseudocystidia sometimes present; true cheilocystidia usually absent but cystidia-like hyphoid elements emanating from the lamellar context or cylindric or strangulated ixo-cheilocystidia embedded in a gelatinous matrix sometimes present; hymenophoral trama inamyloid, regular or subregular but not highly interwoven, divergent or pachypodial; comprised of long or short hyphal segments with oblique or perpendicular cross walls, often constricted at the septations, usually thin-walled but hyphae of the central mediostratum sometimes slightly thickened. Pileipellis structure a cutis, disrupted cutis, ixocutis, ixotrichodermium or trichodermium, but never hymeniform; pigments muscaflavin or carotenoids; clamp connections present or absent; habit terrestrial, rarely on wood or arboreal, often associated with mosses, growing in grasslands or forests; possibly biotrophic (Seitzman et al. 2011) but not known to form ectomycorrhizae with woody plants.

Lichenomphaliaceae (Lücking & Redhead) Vizzini, Consiglio & P. Alvarado, stat. nov. & comb. nov. MycoBank MB851143.

Synonyms: Hygrophoraceae subfamily Lichenomphalioideae Lücking & Redhead, Fungal Diversity 64: 68. 2013. [2014].