Abstract

Integrating pleasure may be a successful strategy for reaching young people with sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) interventions. However, sexual pleasure-related programming and research remains sparse. We aimed to assess chatbot acceptability and describe changes in SRHR attitudes and behaviours among Kenyan young adults engaging with a pleasure-oriented SRHR chatbot. We used an exploratory mixed-methods study design. Between November 2021 and January 2022, participants completed a self-administered online questionnaire before and after chatbot engagement. In-depth phone interviews were conducted among a select group of participants after their initial chatbot engagement. Quantitative data were analysed using paired analyses and interviews were analysed using thematic content analysis. Of 301 baseline participants, 38% (115/301) completed the endline survey, with no measured baseline differences between participants who did and did not complete the endline survey. In-depth interviews were conducted among 41 participants. We observed higher satisfaction at endline vs. baseline on reported ability to exercise sexual rights (P ≤ 0.01), confidence discussing contraception (P ≤ 0.02) and sexual feelings/needs (P ≤ 0.001) with their sexual partner(s). Qualitative interviews indicated that most participants valued the chatbot as a confidential and free-of-judgment source of trustworthy “on-demand” SRHR information. Participants reported improvements in sex-positive communication with partners and safer sex practices due to new learnings from the chatbot. We observed increases in SRHR empowerment among young Kenyans after engagement with the chatbot. Integrating sexual pleasure into traditional SRHR content delivered through digital tools is a promising strategy to advance positive SRHR attitudes and practices among youth.

Keywords: chatbot, conversational agent, sexual pleasure, contraception, family planning, sexual and reproductive health, rights, comprehensive sexuality education

Résumé

Intégrer le plaisir peut être une stratégie efficace pour atteindre les jeunes avec des interventions en matière de santé et de droits sexuels et reproductifs. Néanmoins, les recherches et les programmes liés au plaisir sexuel restent rares. Notre objectif était d’évaluer l’acceptabilité des chatbots et de décrire les changements dans les attitudes et les comportements en matière de santé et de droits sexuels et reproductifs chez de jeunes adultes kenyans faisant appel à un chatbot de santé et droits sexuels et reproductifs axé sur le plaisir. Nous avons utilisé une conception d’étude exploratoire à méthodes mixtes. Entre novembre 2021 et janvier 2022, les participants ont rempli un questionnaire en ligne auto-administré avant et après l’utilisation du chatbot. Des entretiens téléphoniques approfondis ont été menés avec un groupe choisi de participants après leur utilisation initiale du chatbot. Les données quantitatives ont été examinées à l’aide d’analyses appariées et les entretiens ont fait l’objet d’une analyse de contenu thématique. Sur les 301 participants initiaux, 38% (115/301) ont répondu à l’enquête finale, sans aucune différence mesurée au début de l’étude entre les participants qui ont et n’ont pas répondu à l’enquête finale. Des entretiens approfondis ont été menés avec 41 participants. Nous avons observé une satisfaction plus élevée à la fin qu’au départ en ce qui concerne la capacité déclarée d’exercer les droits sexuels (p < 0.01), la confiance en soi pour aborder la contraception (p < 0.02) et les sentiments/besoins sexuels (p < 0.001) avec leur(s) partenaire(s) sexuel(s). Les entretiens qualitatifs ont indiqué que la plupart des participants considéraient le chatbot comme une source confidentielle et sans jugement d’informations fiables « à la demande » sur la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs. Les participants ont fait état d’améliorations dans la communication sexuelle positive avec leurs partenaires et de pratiques sexuelles plus sûres grâce aux nouvelles connaissances obtenues auprès du chatbot. Nous avons observé une augmentation de l’autonomisation des jeunes Kenyans en matière de santé et droits sexuels et reproductifs après le dialogue avec le chatbot. L’intégration du plaisir sexuel dans le contenu traditionnel en matière de santé et de droits sexuels et reproductifs grâce aux outils numériques est une stratégie prometteuse pour faire progresser les attitudes et les pratiques positives de santé et de droits sexuels et reproductifs chez les jeunes.

Resumen

La integración del placer podría ser una estrategia eficaz para llegar a las personas jóvenes con intervenciones de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR). Sin embargo, las investigaciones y los programas relacionados con el placer sexual continúan siendo escasos. Nuestro objetivo era evaluar la aceptabilidad del chatbot y describir los cambios en actitudes y comportamientos de SDSR entre jóvenes adultos kenianos que interactúan con un chatbot de SDSR orientado hacia el placer. Utilizamos un diseño de estudio exploratorio de métodos mixtos. Entre noviembre de 2021 y enero de 2022, los participantes contestaron un cuestionario digital autoadministrado antes y después de interactuar con el chatbot. Se realizaron entrevistas telefónicas a profundidad con un grupo de participantes seleccionados después de su interacción inicial con el chatbot. Se analizaron datos cuantitativos utilizando análisis emparejados y se analizaron las entrevistas utilizando análisis de contenido temático. De 301 participantes en la base de referencia, el 38% (115/301) contestó la encuesta final, y no hubo diferencias iniciales medidas entre los participantes que contestaron la encuesta final y aquéllos que no la contestaron. Se realizaron entrevistas a profundidad con 41 participantes. Observamos mayor satisfacción al final que al inicio relacionada con la capacidad informada para ejercer los derechos sexuales (P ≤ 0.01), confianza para hablar con su(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) sobre anticoncepción (P ≤ 0.02) y sentimientos/necesidades sexuales (P ≤ 0.001). Las entrevistas cualitativas indicaron que la mayoría de los participantes valoraban el chatbot como una fuente confidencial y sin prejuicios de información sobre SDSR confiable y “a pedido”. Los participantes informaron mejoras en comunicación sexo-positiva con parejas y prácticas sexuales más seguras debido a nuevos aprendizajes del chatbot. Observamos aumentos en empoderamiento en SDSR entre jóvenes kenianos después de su interacción con el chatbot. La integración del placer sexual en el contenido tradicional de SDSR difundido por herramientas digitales es una estrategia prometedora para fomentar actitudes y prácticas de SDSR positivas entre la juventud.

Plain language summary

We developed and evaluated a sex-positive digital “chatbot” among young Kenyan adults. The chatbot was developed to include content on standard SRHR topics (including menstrual health, prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, and contraceptive method information), as well as sexual pleasure topics such as information on masturbation, genital health, orgasms, sexual pleasure and satisfaction, and advice for how to improve communication and decision-making with sexual partners. We used a mixed-methods design to assess the acceptability and effectiveness of the chatbot among Kenyan young adults aged 18–29; the quantitative evaluation used baseline and endline online surveys, in which participants completed self-administered digital surveys before and after engagement with the chatbot. A subset of participants selected by gender and age additionally participated in individual in-depth interviews.

We found that exposure to the chatbot was associated with increases in several outcomes related to sexual and reproductive empowerment, including participants’ reported ability to exercise their sexual rights, their confidence discussing contraception with their sexual partner(s), and their confidence sharing their sexual feelings and needs with sexual partners, although we found few changes in contraceptive use before and after engagement with the chatbot. In qualitative interviews, participants reported high levels of trust in the chatbot’s content and high acceptability of its “on-demand” format. Our findings build on the scant evidence base for sexual pleasure programming, suggesting that exposure to a sex-positive SRHR chatbot may support improved SRHR self-efficacy and agency.

Introduction

Despite decades of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) programming, global evidence on effects of incorporating sexual pleasure into SRHR interventions remains sparse.1–4 Researchers have noted that relatively little is known about how contraceptive decision-making is influenced by pleasure.1 This so-called pleasure deficit has led to a lack of nuanced understanding of the positive aspects of sex, which may drive or hinder healthy SRHR attitudes, behaviours, and practice.1,5 Available literature shows positive association of integrating sexual pleasure within broader SRHR interventions and associated health outcomes. Results from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 unique programme interventions suggest that sex-positive programming such as “eroticisation” of contraceptive products can increase contraceptive uptake and adherence, although the evidence is primarily limited to male condom use.6 Efforts to further integrate and scale sex-positive approaches within SRHR programming globally will require stronger evidence of health impact.

Digital communication platforms present new tools for engaging youth in conversations around sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing.7 With the increased availability of internet-enabled phones in low- and middle-income country settings,8 chatbots may be an efficient and discreet mode for delivering pleasure-oriented information and promoting healthy SRH practices. While chatbots are relatively new to SRHR programming, they are increasingly being applied to promote healthy behaviours9–11 including those related to sensitive and personal issues such as mental health care, sexuality, substance abuse, and alcoholism.12–15 Evidence suggests that among young people in diverse settings, health chatbots are perceived to be a fast source of concise, high-quality information that allows for greater anonymity than other sources of information, including hotlines and search engines.14,15 Despite this, relatively little is known about the acceptability or effectiveness of incorporating sexual pleasure content into an SRHR chatbot.

To address this gap, Population Services International (PSI) developed and evaluated a pleasure-oriented chatbot (“Nena”) in Kenya, which integrated content related to sexual pleasure and sex-positive partner communication with traditional SRHR content related to prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). We conducted an exploratory mixed-methods evaluation to assess the acceptability of the chatbot and short-term changes in SRH attitudes and behaviours associated with exposure to the chatbot among a cohort of sexually active Kenyan young adults.

Methods

Intervention

In October 2021, PSI developed the “Nena” chatbot as a pleasure-oriented digital companion for young people exploring sexual health. Nena can be accessed at no cost from any internet-enabled device and is configured using Google DialogFlow and integrated with Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and its own dedicated website. The chatbot is a structured, decision tree chatbot, which provides users with an initial menu of content “topics” and algorithm-driven content sub-branches, which they can navigate using designated numeric responses. Through an inbuilt health facility geo-locator feature, users who opt to self-refer for health services or products are provided options of the closest qualified providers offering youth-friendly health services. Upon first usage, users are asked to review and sign a terms and conditions statement, which includes acknowledgment that Nena does not aim to replace the role of a healthcare provider. The chatbot also allows users to share feedback through an embedded self-reporting mechanism, which collects user experience data on the usefulness of the content and on intermediate behavioural and health outcomes related to their interactions with the chatbot.

Nena was developed through a series of co-creation workshops with Kenyan youth. The chatbot content was first developed and reviewed by an SRHR expert, third author (CO), and the PSI Quality of Care Team. The content was also shaped by a user experience (UX) and design team, which aimed to improve the style and process flow and adapted the language to optimise accessibility and user experience. Key insights that emerged during the programmatic design process included an openness among Kenyan youth to discussing sexual pleasure topics, including a strong interest in information on how to give and receive sexual pleasure, and a perceived lack of trustworthy sources of information on this topic. Test users dismissed complex, overly medicalised terminology and content, preferring design-forward photos and graphics. User insights from the design process revealed strong preferences for alternatives to face-to-face interactions with health educators and providers and a desire for the privacy and convenience of on-demand information. Design phase insights were used to prioritise content development and to iteratively refine the chatbot content and tone throughout the design process.

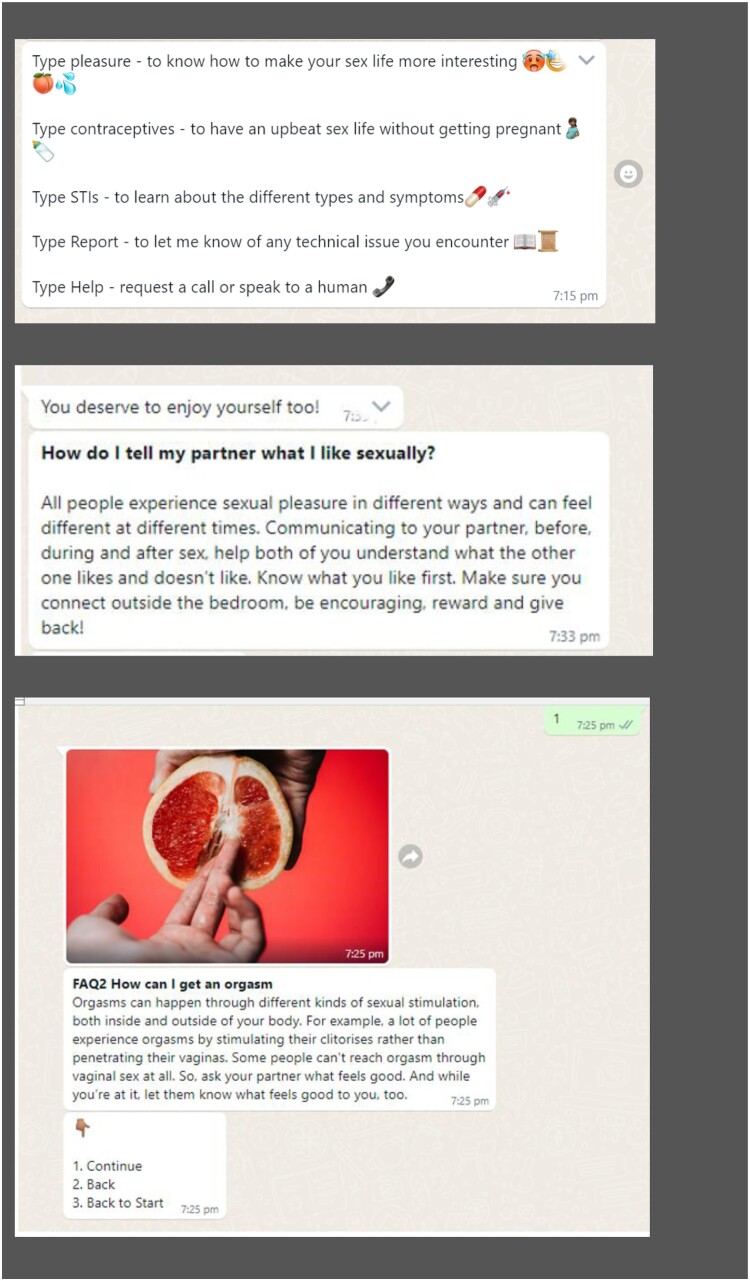

The resulting chatbot includes content on sexual pleasure, including how to have “good sex,” how to improve communication with sexual partners, and information on orgasms and masturbation; pregnancy prevention, including contraceptive method options and contraceptive side-effects; menstrual and genital health; and prevention of STIs including HIV. Counselling for choice (C4C) materials were used as the basis for contraceptive method information (https://www.psi.org/c4c/). In addition to content specific to sexual pleasure, the chatbot aims for a sex-positive tone that normalises pleasurable sex as a healthy adult behaviour (Figure 1). A social media-based campaign was used to generate awareness about the chatbot and to directly link interested users to Nena.

Figure 1.

Sample content from the Nena chatbot

Study design and population

The exploratory mixed-methods evaluation included a baseline and endline quantitative survey supplemented by in-depth interviews. The mixed-methods approach was selected to facilitate data triangulation and explanation of quantitative measures with qualitative data.16 The evaluation was exploratory in design to assess self-reported changes across a variety of SRHR attitudes and behaviours; as such, no primary outcome was specified a priori for the evaluation. Given that the number of Kenyan young adult (18–29 years) active social media users who would visit the chatbot was unknown, we assumed a conservative response rate (50% = 0.5), a 95% confidence interval (alpha = 0.05), and 10% drop-off rate at endline to arrive at a minimum required sample of 423. Participants were recruited for the study directly through the Nena chatbot from November 2021 to January 2022. First time users received a message within the chatbot about their potential eligibility to participate in a study on sexual and reproductive health. Those interested followed an opt-in participation process and were directed to an integrated online form which assessed eligibility, collected electronic informed consent, and administered a baseline questionnaire among eligible and consenting participants. Individuals were eligible to enrol if they were 18–29 years old, currently residing in Kenya, had a personal phone number with internet access, and were sexually active in the past 12 months. Sexual activity was not specifically defined, allowing personal interpretation based on individual understandings and definitions of sexual activity. We chose to exclude sexually inactive individuals, as the focus of this formative research was to explore changes in sexual attitudes and behaviours that relate to interactions with sexual partners. Additionally, individuals who reported previously accessing sexual pleasure content through a chatbot were excluded, in order to capture experiences prior to engagement with chatbot-based pleasure content at baseline. All users were able to access chatbot educational materials including those who did not opt in or were ineligible for study participation.

Data collection

Quantitative questionnaire

After providing digital consent, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire which collected information on sociodemographic characteristics (age group, relationship status, and gender); current contraceptive use; recent receipt of SRH services including diagnostic tests for HIV or other STIs; current sexual behaviours; and self-rated satisfaction across several dimensions of their current sex life, including attitudes towards sexual rights, partner dynamics, and engagement in pleasure-focused sexual practices such as masturbation.

Eligible participants were asked to provide a private telephone number at which to receive a link to a follow-up endline questionnaire administered in the same online format as the baseline questionnaire. The endline survey link was sent approximately 2–3 weeks after the baseline questionnaire via WhatsApp message. The selection of 2–3 weeks was based on programmatic learnings that suggested many users engage with chatbots during a relatively brief period concentrated within the first week of initiating interaction with the chatbot. As such, the 2–3-week interview timing allowed assessment after a period of high engagement with the chatbot. Participants were able to complete the survey up to ∼8 weeks after the survey was delivered, following reminder messages. Participants received a small incentive in the form of mobile airtime upon completion of the endline survey. The endline survey included the same questions as the baseline survey, with the addition of a module to assess experiences and satisfaction with the chatbot. Participants took a median of 6.4 minutes [IQR: 4.69–8.88] and 8.22 minutes [IQR: 6.09–10.2] to complete baseline and endline surveys, respectively.

Phone-based individual in-depth interviews

Individual in-depth interviews were conducted by phone approximately 2–3 weeks after participants’ initial engagement with the chatbot. We used stratified simple random sampling within strata defined by gender and age category (18–24 and 25–29 years old) among those who consented to participation in the qualitative component at baseline. A total of 41 qualitative interview participants were recruited and interviewed after the endline survey was sent out to them. Trained qualitative research assistants of the same gender as the participant conducted interviews using a semi-structured interview guide, available in both English and Swahili, to explore acceptability and user experiences interacting with the chatbot, as well as perceived changes in attitudes and behaviours that participants self-attributed to engagement with the chatbot. Interviews were recorded with the verbal consent of the participants, transcribed, and translated to English if conducted in Swahili. Transcription and translation procedures were completed by the same research assistants who conducted the interviews (RN and EK) under the supervision of the first and second authors. Detailed notes were taken if a participant consented for the interview but declined for the conversation to be recorded.

Ethics statement

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the AMREF Ethics & Scientific Review Committee (P999-July 2021). Individuals electronically opted in for the eligibility assessment; eligible individuals provided electronic consent prior to study enrolment. Participants in qualitative phone-based interviews provided verbal consent.

Analytic approach

Quantitative data

Participant characteristics and responses related to chatbot usage were summarised using descriptive statistics, including summaries of counts and proportions for binary and categorical variables and means with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables. Relevant experiences related to the chatbot usage and content were measured using a self-reporting 5-point rating Likert scale (1 = “very poor”; through 5 = “very good”).

A 10-point rating Likert scale, with 1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest possible satisfaction, was used to measure satisfaction before and after engagement with the chatbot. Among the self-rated satisfaction items included practices related to “Protection from unwanted pregnancy”; “Protection from HIV and other STIs”; “Overall current sex life”; “Amount and variety of sex”; “Pleasure in my sex life”; and “Exercising my sexual rights and needs”. Similarly, a 5-point rating Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all true”) to 5 (“Extremely true”) was used to measure additional attitudes and practices related to sexual pleasure empowerment, self-pleasure, and partner dynamics and communication. We adopted a three-item sub-scale, anchored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Not at all true”; through 5 = “Extremely true”), from the Sexual and Reproductive Empowerment for Adolescents and Young Adults (SRE for AYA) validated scale for measuring sexual pleasure empowerment.17,18 The scale items include: (1) “My sexual needs or desires are important”; (2) “I think it would be important to focus on my own pleasure as well as my partner’s during sexual experiences”; and (3) “I expect to enjoy sex.”

We measured changes in SRHR attitudes and practices from baseline to endline using paired t-tests for continuous measures; McNemar’s test (an extension of the chi-squared test appropriate for paired data) for categorical measures; and Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for paired ordinal measures. For all tests, we defined statistically significant changes using two-tailed test statistics with α = 0.05. We assessed selective attrition and observed that there were no significant differences in the key characteristics between the baseline and endline samples. All analyses were performed using STATA 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Qualitative data

Following transcription and translation of the in-depth interviews, all data were uploaded into the Dedoose, a qualitative analytic software.19 A deductive-inductive hybrid thematic coding approach was used to analyse the data.20 A codebook was initially developed using a pre-determined coding framework developed from the interview guide. All transcripts were then read through in their entirety. This review of the data helped inform the development of sub-codes based on emerging nuanced topics to be used during analysis. All transcripts were then coded, initially by one coder to determine preliminary results. After the data were coded, codes and sub-codes were analysed using qualitative analytic software to examine patterns and identify major and recurrent themes. A second coder then independently reviewed the transcripts, adding additional sub-codes to the overall framework based on emerging themes (see final codebook in Appendix 1). The analysis was stratified by gender to determine if results differed across sampling strata. Consistent with our mixed-methods approach, we present the qualitative results alongside and as an explanator to the quantitative findings.

Results

Participant characteristics

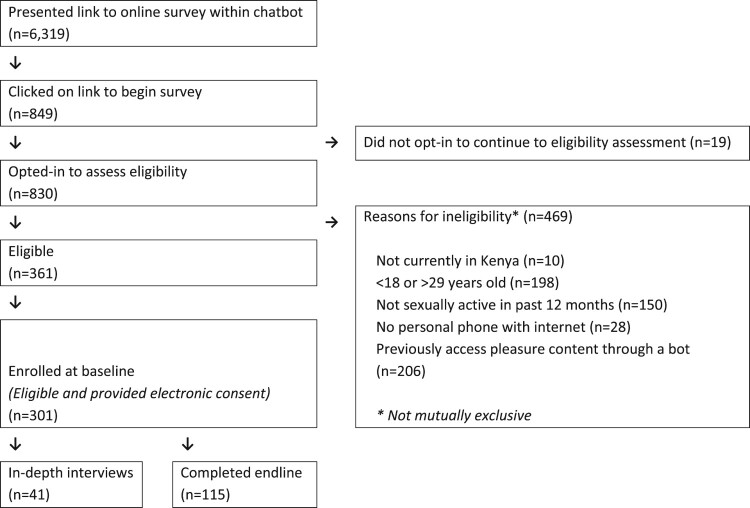

A total of 6319 individuals were presented with a survey link embedded within the chatbot (Figure 2). Of these, 849 followed the link to the online baseline questionnaire and 830 opted in to continue with a short eligibility assessment module. Of individuals who opted in, 44% (361/830) were eligible and 301 consented to participate in the study. The most common reasons for ineligibility were previous exposure to pleasure content in a chatbot (206/469, 44%), an age of less than 18 years or above 29 years (198/469, 42%), and not being sexually active in the past 12 months (150/469, 32%). Of the 301 enrolled participants, 115 (38%) completed the endline survey. Timing of completion of the endline survey varied (median of 10 weeks after study enrolment [IQR: 3–12 weeks]). The reasons for high sample attrition were not obvious to the study team, given that all enrolled participants had consented and received reminders with a link to complete the endline survey. However, it is a possibility that a lack of reliable internet access was a cause.

Figure 2.

Eligibility and study flow

We observed no statistically significant differences between enrolled participants who did and did not complete the endline survey (Table 1). Of 301 baseline participants, nearly two-thirds (64%) were young adults aged 18–24 years. Forty-four percent were women, 36% were men, and 20% did not identify their gender. At baseline, most participants were unmarried and partnered (60%), while 24% and 16% were single and married, respectively. Fifty-four percent of participants reported current use of a modern contraceptive method by either themselves or their partner. One-fifth (20%) reported seeking SRH services at a health facility in the past four weeks, while one-third (32%) reported being tested for HIV or other STIs over the same period.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline sample characteristics by endline survey completion status

| Baseline sample characteristics | Endline survey completion status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Completed (n = 115) | Not completed (n = 186) | Total (n = 301) | P-value† | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 107 | 46 (40) | 61 (33) | 107 (36) | |

| Female | 133 | 47 (41) | 86 (46) | 133 (44) | 0.45 |

| No response | 61 | 22 (19) | 39 (21) | 61 (20) | |

| Age in years | |||||

| 18–24 | 193 | 73 (64) | 120 (65) | 193 (64) | 0.86 |

| 25–29 | 108 | 42 (37) | 66 (36) | 108 (36) | |

| Relationship status | |||||

| Unmarried, partnered | 174 | 64 (59) | 110 (61) | 174 (60) | |

| Unmarried, single | 68 | 30 (28) | 38 (21) | 68 (24) | 0.29 |

| Married | 47 | 14 (13) | 33 (18) | 47 (16) | |

| Sexual and reproductive health care-seeking and practices | |||||

| In past 4 weeks: | |||||

| Sought SRHR services at a health facility | 287 | 21 (19) | 37 (21) | 58 (20) | 0.71 |

| Tested for STIs/HIV | 290 | 29 (26) | 63 (35) | 92 (32) | 0.11 |

| Current contraceptive use | 273 | 57 (56) | 90 (53) | 147 (54) | 0.60 |

* Number of non-missing observations.

† P-values were determined with a Pearson’s Chi-squared test for categorical measure and with a two-sample Welch's t-test for numerical measures.

Forty-one individuals completed qualitative interviews. Interviewed participants include 21 men and 20 women. Twenty-one of the participants were in the 18–24-year-old age bracket while 20 participants were in the 25–29-year-old age bracket.

Acceptability and perceived value of chatbot

More than one-third (38%) of endline participants reported that they interacted with the chatbot 2–3 times, with an additional 30% reporting a single interaction and 20% of participants reporting more than three distinct interactions with the bot (Panel A of Table 2). Although all participants were recruited from within the chatbot, 13% reported that they never used it.

Table 2.

Descriptive results of “Nena” chatbot evaluation at endline survey

| Panel A: Self-reported engagement with the “Nena” chatbot at endline survey, by gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of chatbot engagement (n* = 112) | Male (n = 46) | Female (n = 47) | Total† (n = 115) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Never accessed | 8 (17) | 2 (4) | 14 (13) | |||

| Once | 14 (31) | 14 (30) | 34 (30) | |||

| 2–3 times | 16 (36) | 16 (35) | 42 (38) | |||

| >3 times | 7 (16) | 14 (30) | 22 (20) | |||

| Panel B: Self-reported evaluation of “Nena” chatbot, among those who accessed the chatbot at least once (N = 98) | ||||||

| Rating on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (Very good): | Very poor | Poor | Neither poor nor good | Good | Very good | |

| n* | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Ability to understand and respond to your needs | 95 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 53 (56) | 38 (40) |

| Tone in which it was speaking to you | 95 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 55 (58) | 36 (38) |

| Chatbot’s sex pleasure content in terms of how it relates to your needs | 87 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 7 (8) | 50 (58) | 29 (33) |

| Chatbot’s sex pleasure content in terms of how easy it was to understand | 86 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 52 (61) | 30 (35) |

| Chatbot’s sex pleasure content in terms of how much you trust the information | 84 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 51 (61) | 29 (35) |

| Rating on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree): | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| I learned new information from the chatbot | 95 | 0 (0) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 49 (52) | 32 (34) |

| Chatbot provided information that is not true | 92 | 41 (45) | 39 (42) | 6 (7) | 6 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Because of the chatbot, I am more comfortable communicating with my sexual partner(s) about my sexual health and needs | 91 | 0 (0) | 8 (9) | 14 (15) | 50 (55) | 19 (21) |

| Chatbot encouraged me to view sex as pleasurable | 95 | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 53 (56) | 29 (31) |

| Because of the chatbot, I feel confident using health centres or other facilities for sexual and reproductive health services and products | 94 | 0 (0) | 8 (9) | 13 (14) | 53 (56) | 20 (21) |

| Because of the “Nena” chatbot, I feel confident using sexual and reproductive health services and products, but not at health centres or other facilities | 94 | 5 (5) | 12 (13) | 20 (21) | 44 (47) | 13 (14) |

| Because of the “Nena” chatbot, I will embrace healthier sexual behaviours in the future | 94 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (9) | 45 (48) | 41 (44) |

*Number of non-missing observations.

† Denominator includes 22 observations with unspecified gender information.

Most chatbot users reported positive experiences using the chatbot (Panel B of Table 2). Nearly all users agreed that the chatbot understood and responded to their needs well (56%) or very well (40%). The chatbot’s tone was widely rated as good (58%) or very good (38%). Most users reported they learned new information from the chatbot (52% agreed, and 34% strongly agreed), and few reported that the information was inaccurate (7%) or were unsure of its validity (neither true nor false, 7%). Nearly all users rated the sexual pleasure content’s relevance to their needs as good (58%) or very good (33%). The sexual pleasure content was also regarded as easy to understand (61%) or very easy (35%), and trustworthy or very trustworthy by 96% of users.

These quantitative findings were confirmed by in-depth interviews. Overall, participants reported that the chatbot was easily accessible, the content was easy to understand, and they were appreciative of its direct and friendly tone.

“Okay, in my opinion, I think [the chatbot] it is easy to understand because when you need something which needs to be elaborated there is an icon you can click and then you get some more information about the content.” [Female#11, 25–29 years]

“Yeah, it was the right way, the right tone. Because you know, I’m saying when you go say for a mentorship, not many people talk about matters to do with sex and reproductive health. They usually beat around the bush so much. But the chatbot was like straight to the point, and it tells you what this is. Yes, I can say the tone was quite good.” [Male#14, 25–29 years]

None of the participants were concerned with the privacy or the security of the chatbot.

“It was private and secure and direct to the point. Because that robot, can I say it is a robot that is connected. I believe and felt like I was just talking to one person. I wasn’t talking to many people. Yeah, I felt it was private.” [Male#9, 18–24 years]

“I do not think there was a part for [capturing] names which I felt was a good thing because most of us usually want to ask and answer these questions but being anonymous.” [Female#7, 25–29 years]

Many participants reported that they appreciated having the opportunity to explore culturally sensitive topics and ask questions on a platform that was accurate, convenient, confidential, and free of judgement.

“Yes [the chatbot] was empowering … If you come to other health facilities there are discriminations but at least with the chatbot, you can communicate when you are at home and get whatever you want to get from an expert. It is quite efficient.” [Male#16, 18–24 years]

“What I liked about the content … it answered the questions like directly. Like I said you getting like not different opinions about. Like I google [search] about contraceptives and you get, I think when you google about it you get different ideas about it. But for chatbot it goes directly to the point the answer that I was looking for.” [Female#19, 18–24 years]

Participants liked the chatbot’s fast response time and ease of navigation throughout the chatbot’s content.

“The [chatbot] response time is not that long like when you write and then you wait for like feedback, it was actually quite fast.” [Female#18, 18–24 years]

Almost all participants found that the chatbot addressed their needs, reporting that the content was very informative, it answered all their questions, and it covered many of the details they found to be important. The majority of participants thought that the chatbot was friendly, valuable, and empowering. Specifically, they reported learning a lot of new information from the chatbot and gaining increased confidence from it.

“It was good because it tackled like every question there is to know about sexual education. I liked how it was broken down in terms of contraception and pleasure … it helps one have a broader idea of like sex and topics like those that we feel like are normally a taboo especially in our culture. Because when you look at it, our culture, when we were growing up no one really wanted to tell you how sex is, what sex is like, how to, you know, prevent yourself from getting pregnant or getting an STI … Nena has created a platform where at least our questions can be answered.” [Female#7, 25–29 years]

Few participants reported they disliked any aspect of the chatbot. Of those who did, they stated that they found the information offered to be limited in scope or lacked the depth necessary for their comprehension. Other participants reported that they reached the end of the content without finding what they were looking for or that they found that the content was overly summarised.

“For example, I wanted to ask more about contraceptive injections. Yes, the 3 months injections. I wanted to find more about its side-effects and so on, but it [chatbot] was narrowing it down for me. There is effectiveness and side effects, but it is narrowing it down. I wanted more explanation to know the side effects, but it was narrowing down and summarizing. I wanted more information about it.” [Male#9, 18–24 years]

“I didn’t use it [chatbot] much because I didn’t understand how it was. I was not getting the information like I wanted. You see, like now, I am talking to you which is unlike the chatbot. The difference is, it would be easier to explain when you are talking. Yes, you can be able to explain well. You can get bored with it [chatbot] and leave.” [Male#12, 18–24 years]

Changes in SRHR outcome measures among chatbot users

Tables 3 and 4 summarise paired analyses to assess changes in SRHR measures, comparing the endline to baseline questionnaires on a rating scale with 1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest possible satisfaction. Relative to baseline, we found significantly higher mean satisfaction ratings at endline on sex life overall (5.8 at baseline to 6.5 at endline; P = 0.005), amount and variety of sex (5.3 at baseline to 6.3 at endline; P = 0.001), ability to exercise sexual rights (6.2 at baseline to 6.9 at endline; P = 0.01), and belief that they and their partner(s) treated each other with respect and consideration (P = 0.02). We also found evidence of increased confidence discussing contraception (P = 0.02) and sexual feelings and needs (P ≤ 0.001) with sexual partners after exposure to the chatbot.

Table 3.

Pairwise comparison of SRHR care practices and sexual pleasure at baseline and endline

| SRHR care-seeking practices and sexual pleasure | Baseline | Endline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | % | % | P-value** | |

| Sexual and reproductive health care-seeking and practices | ||||

| Current contraceptive use | 86 | 56% | 66% | 0.05 |

| Current use of modern contraception | 86 | 48% | 54% | 0.25 |

| Current use of LARC | 86 | 7% | 12% | 0.05 |

| In past 4 weeks† | ||||

| Sought SRHR services at a health facility | 93 | 17% | 24% | 0.22 |

| Tested for STIs/HIV | 95 | 24% | 19% | 0.35 |

| Rating on a scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied): | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-value‡ | |

| Protection from HIV and infections | 93 | 6.9 (3.0) | 7.3 (2.7) | 0.28 |

| Protection from unwanted pregnancy | 93 | 7.2 (3.0) | 7.3 (2.9) | 0.69 |

|

Sexual pleasure Rating on a scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied): |

Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-value‡ | |

| Overall sex life | 95 | 5.8 (2.5) | 6.5 (2.5) | 0.005 |

| Amount and variety of sex | 92 | 5.3 (2.7) | 6.3 (2.8) | 0.001 |

| Pleasure in sex life | 90 | 6.2 (3.1) | 6.7 (2.8) | 0.14 |

| Exercising sexual rights and needs | 94 | 6.2 (2.8) | 6.9 (2.8) | 0.01 |

* Number of non-missing observations at baseline and endline among those who accessed the chatbot.

† Endline participants were asked if they recently received the service, i.e. 2–3 weeks preceding the survey date.

** P-values are determined using McNemar's test for paired categorical measures.

‡ P-values are determined using paired t-test for numerical measures.

LARC is long-acting reversible contraception method.

SD is the standard deviation.

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of attitudes related to sexual pleasure and partner dynamics and communication at baseline and endline

| Agreed or strongly agreed to following statements | Rating on a scale from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Extremely true) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Survey | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P-value† | |

| % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| I expect to enjoy sex | 95 | Baseline | 4 | 2 | 7 | 44 | 42 | 0.11 |

| Endline | 1 | 0 | 8 | 48 | 43 | |||

| I focus on my own pleasure as well as my partner | 95 | Baseline | 2 | 1 | 5 | 45 | 46 | 0.40 |

| Endline | 0 | 0 | 4 | 48 | 48 | |||

| My sexual needs or desires are important | 94 | Baseline | 0 | 1 | 6 | 48 | 44 | 0.12 |

| Endline | 0 | 1 | 3 | 42 | 54 | |||

| Attitudes toward self-pleasure | Rating on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Self-pleasure like masturbation is an acceptable for me | 92 | Baseline | 17 | 14 | 23 | 29 | 17 | 0.30 |

| Endline | 10 | 20 | 21 | 29 | 21 | |||

| Masturbation is one of the activities I engage in for sexual pleasure | 93 | Baseline | 16 | 23 | 17 | 29 | 15 | 0.64 |

| Endline | 14 | 18 | 21 | 33 | 14 | |||

| Partner dynamics and communication | ||||||||

| I consider myself an equal to my sexual partner(s) with respect to needs and feelings | 94 | Baseline | 0 | 5 | 7 | 53 | 35 | 0.10 |

| Endline | 0 | 6 | 2 | 50 | 42 | |||

| I feel confident discussing contraception with my sexual partner(s) | 95 | Baseline | 0 | 14 | 12 | 36 | 39 | 0.020 |

| Endline | 1 | 5 | 8 | 40 | 46 | |||

| I feel confident communicating my sexual feelings and needs to my partner(s) | 93 | Baseline | 8 | 13 | 11 | 34 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Endline | 1 | 7 | 11 | 38 | 43 | |||

| My sexual partner(s) and I treat each other with respect and consideration | 91 | Baseline | 2 | 4 | 14 | 51 | 29 | 0.02 |

| Endline | 1 | 3 | 4 | 52 | 40 | |||

* Number of non-missing observations at baseline and endline among those who accessed the chatbot

† P-values are determined using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for paired ordinal measures

However, we did not observe significant improvements in practices related to the current use of any contraceptive (56% at baseline to 66% at endline; P = 0.05) or modern method use (48% at baseline to 54% at endline; P = 0.25), seeking SRHR care at a facility (17% at baseline to 24% at endline; P = 0.22) or testing for STI/HIV (24% at baseline to 19% at endline; P = 0.35). Similarly, we found no significant changes in attitudes related to sexual pleasure, including the following statements: “I expect to enjoy sex” (P = 0.11), “I focus on my own pleasure as well as my partner” (P = 0.40), and “my sexual needs/desire are important” (P = 0.12). We also did not find evidence of changes in reported acceptance of self-pleasure activities (P = 0.30) or engagement in masturbation (P = 0.64). We did not detect change in participants’ beliefs that they consider themselves as equal to their sexual partner(s) with respect to needs and feelings (P = 0.10).

To qualitatively evaluate the impact of the chatbot, participants were asked whether the chatbot changed their attitude or behaviour or sex lives in any way. Most participants reported that the chatbot had an impact of some kind. The most common response was that the chatbot improved sex communication, with participants reporting that the chatbot increased their confidence to talk with their sexual partners.

Almost all women reported improvement in sexual communication, stating that they had become more confident talking about how to achieve their own pleasure or discussing about safer sex practices with their partner including contraceptive use.

“[After using the chatbot] now you feel like you know there is this side telling you that you deserve to get that pleasure, girl go get it! You are like yeah if you are wasting my time just leave.” [Female#10, 25–29 years]

“I will openly just say something even to my partner that I had never said before. Yes, before the chatbot, I was not on any contraceptives but after reading and learning a few things. I was able to discuss it with my partner and we have moved forward.” [Female#12, 25–29 years]

Interviews found that women were more likely than men to report changes in attitudes about their own sexual pleasure. Women stated that they learned that they are deserving of pleasure and how to make sexual experience a more mutual endeavour from the chatbot.

“Before, I used to think that [it is] okay I should concentrate more on making my partner like feel good. And forgetting about myself, but at least when I got to read from Nena [chatbot] I was able to get that it should be mutual.” [Female#4, 25–29 years]

Similarly, more than half of men reported improvements in sexual communication, due to increased confidence asking their partner about what they find pleasurable, communicating their own feelings about sex, and finding out their partner’s STI or HIV status.

“Before I accessed the chatbot, I didn’t understand what my partner thinks about sex. So, when I accessed the chat bot, it was very easy to communicate with my partner about sex. We were both open because I was asking her questions on how she would like us to have sex. She would tell me and that helped us. At least there is a difference between before I accessed the chatbot and after I accessed it.” [Male#12, 18–24 years]

Few participants, across both genders, reported an increase in self-pleasure after chatbot use, with several women reporting that they do not engage in self-pleasure and many men reporting that it is a practice they already engaged in frequently. However, for the men that did report a change, they emphasised that they appreciated learning that masturbation was not a sin or a negative practice but that it is a healthy sexual activity.

“Yes, [I learned something new] about the masturbation. Yeah. It is not something which is unbelievable; it is okay. You know sometimes you think that some things are not natural so, you try to avoid. It reached a point that I even stopped. So, I was beginning to think it might have caused some damages, maybe some side-effects. So, I found that it has no side-effects.” [Male#7, 25–29 years]

Discussion

This study contributes to a sparse literature on the impact of incorporating sexual pleasure into SRHR programming in low- and middle-income countries. We found that provision of sex-positive SRHR content delivered through a chatbot was acceptable to chatbot users and may have positively influenced several attitudes and self-reported practices related to SRHR among sexually active young people in Kenya.

Findings from this exploratory evaluation of a pilot intervention suggest that digital tools such as chatbots may be effective and efficient modes of engagement with young people, who are widely considered a hard-to-reach audience for SRHR interventions. A dominant theme that emerged from qualitative interviews was the high value that chatbot users placed on being able to obtain reliable information quickly and when they wanted it: the chatbot’s delivery of accurate “on-demand” information was viewed by many participants as a major improvement relative to other common sources of SRHR information. Participants’ preference for quick, easily available, and reliable information mirrors broader preferences in SRHR care among young people, who place high value on ease, convenience, and privacy as key choice drivers. For example, several studies have found that Kenyan young adults often seek contraception at non-facility service delivery points such as pharmacies or drug shops due to perceived privacy, convenient hours, and quick service times.21,22 From a programmatic perspective, taken together, these findings imply that privacy and on-demand convenience should be paramount considerations in the design of youth-responsive SRHR interventions, including digital tools in addition to brick-and-mortar service delivery options.

In Kenya and similar settings, sexual behaviours among young people are strongly influenced by social norms that sometimes reinforce negative messages about sexual desire and pleasure, contraception, and partner communication.23–26 A lack of comprehensive sexuality information among young adults is a contributor to high unmet need for SRHR services, which may in turn contribute to higher rates of unintended pregnancy, HIV, and other STIs.27–29 Our findings indicated that exposure to the chatbot content was significantly associated with improvements in SRHR empowerment and wellbeing, which are critical to health outcomes. Specifically, we observed improvements in self-reported measures of satisfaction with overall sex life, amount and variety of sex, and empowerment in sexual relationships, including self-confidence discussing sexual feelings, needs, rights, and contraceptive use with sexual partners. Improved interpersonal communication, particularly among women, has been found to be positively associated with sexual and relationship satisfaction, including improved sexual self-esteem, and ability to negotiate safer sex.30,31

While this study focused on sexually active Kenyan youth, we found that one-fifth (18%) of chatbot users who were assessed for study eligibility were not sexually active in the past year. A considerable proportion of sexually inactive youth engaging with a pleasure and SRHR chatbot suggests an area rich for further research. Engagement with young people, particularly young men and those who are not yet sexually active, is notoriously difficult.32 The high proportion of survey respondents who were ineligible due to sexual inactivity suggests that pleasure-oriented digital content may be a promising mode for increasing access to accurate SRHR information in these traditionally hard-to-reach groups. Future research should specifically explore the feasibility and acceptability of sexual pleasure as an engagement strategy for SRHR information exchange before sexual debut. While we do not fully understand the longer-term user experiences and effects on SRHR-related outcomes following chatbot engagement, this initial assessment serves to generate hypotheses about the potential impacts and mechanistic pathways by which chatbots could influence sexual health and wellbeing. Further research will be critical for confirming the exploratory findings of this study and to explore additional topics of interest, such as the added value of incorporating sexual pleasure content into more “traditional” SRHR topics (e.g. pregnancy and STI prevention) and potential effect modification by age, gender, and relationship status.

Although phone ownership and internet services are rapidly increasing in many low- and middle-income countries, inequitable access to digital technology remains a challenge across geographies and socio-economic status.33 We acknowledge that innovative chatbot technologies may not sufficiently address informational needs of underserved youth populations that lack access to a personal smartphone and reliable internet connection. In this study, 13% of eligible study participants recruited directly through the chatbot reportedly did not access any educational materials through the chatbot. While this may reflect lack of interest, these participants may also have experienced technological barriers, such as lack of internet data bundles and poor internet connectivity that prevented access to content. In this study, barriers to engagement with the chatbot driven by technology illiteracy and “technophobia” were less likely, given that all participants were recruited online from within the chatbot, reportedly owned a smartphone, and were able to complete online self-administered surveys. It is plausible that reported lack of chatbot engagement was in part driven by barriers to full internet access among participants, rather than due to interest alone. However, it is worth mentioning that few of our chatbot users reported that they could not find specific details that they desired to access or did not learn any new information. Lessons from previous chatbot studies underscore the importance of continuous review and improvement of content to address diversified and ever-shifting informational needs and other user curiosities.34,35 Of direct relevance for chatbot development, studies have shown that user engagement is enhanced when technology is simple and with sufficient features to encourage feedback loops and timely integration of user-stated needs.9,14 While our version of the chatbot was based on a decision tree with predetermined branching options and content, with advances in artificial intelligence-powered technology, chatbots are leveraging natural language processing and machine learning approaches for enhanced human-like interactions between the user and the chatbot.9,36

This study has several strengths, including its prospective longitudinal design. Our use of mixed-methods research allows for triangulation of findings across quantitative and qualitative data sources. The exploratory nature of the evaluation allowed for exploration of a range of outcomes related to SRHR, including collection of one of the few SRHR empowerment scales validated for adolescents and youth. This study also has several limitations. We experienced high loss in follow-up in the endline quantitative survey. Although participants who completed the endline survey appear comparable to those who did not on measured baseline characteristics, selection bias remains possible. The relatively small sample of users (n = 98) who answered evaluation questions about the chatbot limits the ability to generalise our findings. Social desirability bias may have influenced responses and reduced negative feedback about the chatbot, particularly among participants whose endline responses were submitted after the qualitative interview. Findings should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, we assessed multiple outcomes which were not adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing; as such, results should be interpreted as exploratory rather than confirmatory. Second, although the baseline and endline online surveys account for time-invariant individual characteristics, our analysis does not account for characteristics that may have changed over time within individuals (e.g. relationship status); therefore, residual confounding by time-varying characteristics is possible. Third, our quantitative study design does not allow us to assess the additional effect of incorporating pleasure content, above and beyond any effect of the “traditional” SRHR content provided by the chatbot. Finally, this evaluation work was based on a PSI developed chatbot and the evaluation was conducted by PSI staff. This could have introduced bias to the findings given that the evaluators were not independent from the implementers. However, PSI evaluators were knowledgeable of the pilot intervention, allowing them to ask more nuanced and targeted questions specific to the learning objectives and future chatbot development.

Conclusions

This study provides promising and programmatically relevant insights into sexual pleasure, an area which continues to be neglected in both SRHR research and programming. With the proliferation of SRHR chatbots, incorporating a sex-positive lens may be an efficient way to effectively reach and meaningfully engage youth and to advance SRHR empowerment. Our findings suggest that engagement with the chatbot may have contributed to changes in young people’s knowledge and attitudes about sexual pleasure, ability to openly communicate about their SRHR-related needs, and to engage in safer sexual and reproductive health practices.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants for agreeing to share their experiences, as well as Susannah Gibbs and Erica Felker-Kantor for comments on the paper.

Appendix 1.

Qualitative final codes and descriptions

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Benefit of chatbot | Participant identified benefits from using the chatbot |

| Chatbot like | What the participant liked about the chatbot |

| Chatbot dislike | What the participant disliked about the chatbot |

| Accessibility | What the participant liked or disliked about the accessibility of the chatbot (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Confidentiality | What the participant liked or disliked about how confidential they felt the chatbot was (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Chatbot content | What the participant liked or disliked about the chatbot’s content (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Platform of accessing content | What the participant liked or disliked about the platform where they accessed the chatbot (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| General information on content | Participant talks about the content of the chatbot (general, other information not applicable to subcodes) |

| Accuracy of content | Participant gave opinion on the accuracy of the content (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Content addresses need | Participant gave opinion on whether the content is valuable and/or addresses their needs (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Believable content | Participant gave opinion on the believability of the chatbot’s content (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Empowering content | Participant gave opinion on whether they felt the content was empowering (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Relatable content | Participant gave opinion on whether the content spoke/relatable to their personality (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Tone of chatbot | Participant gave opinion on whether the content was delivered at the right tone (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Understandable content | Participant gave opinion on whether the content was easy to understand (tag with either chatbot like or chatbot dislike) |

| Accessed health content | Whether or not the participant accessed the SRHR health content and how they felt about it |

| Learned from health content | Participant described if they learned anything from the SRHR health content and what they learned |

| Accessed pleasure content | Whether or not the participant accessed the sex pleasure content and how they felt about it |

| Learned from pleasure content | Participant described if they learned anything from the pleasure content and what they learned |

| General experiences of chatbot | The participant describes their experience using the chatbot (General, can add subcodes as themes emerge) |

| Chatbot user journey | Participant described their journey through the chatbot. Where they started and how they moved through the chatbot |

| Privacy of chatbot access | Whether or not the participant felt their access was private and secure and why |

| Changes of chatbot on sexual life | Participant describes aspects of their sexual life that has changed because of accessing the chatbot’s content (general and/or about themes not included in subcodes) |

| Changes of chatbot on communication | Participant describes how their communication about sex with their partner has changed because of the chatbot’s content |

| Changes of chatbot on pleasure desire | Participant describes how their desire for pleasure has changed because of the chatbot’s content |

| Changes of chatbot on pleasure experiences | Participant describes how their amount of pleasure experienced has changed because of the chatbot’s content |

| Changes of chatbot on safe sex | Participant describes how they have safer sex because of the chatbot’s content |

| Changes of chatbot self-pleasure | Participant describes how their self-pleasure practices have changed because of the chatbot’s content |

| Changes of chatbot on health services | Participant describes how that the health services or products they use have changed because of the chatbot’s content |

| Change in health | If the participant identified an attitude or behaviour change related to health due to the pleasure content |

| Attitude change | Participant identified changes in attitude from using the chatbot |

| Behaviour change | Participant identified changes in behaviour from using the chatbot |

| Chatbot had no impact | Participant’s mentioning that the chatbot had little impact or effect on their attitudes or behaviours. Also, if they say they do not remember content. |

| Suggestions for improvement | Participant provides suggestion to update the chatbot or suggests potential additional programming on pleasure or SRHR |

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) through the Frontier Technologies Phase 2 (FT2) program under contract C4647. The views expressed in this work represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of FCDO.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Contributor roles taxonomy

Julius Njogu (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8285-2906): Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft

Grace Jaworski: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

Christine Oduor: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Software

Aarons Chea: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Alison Malmqvist: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition

Claire W. Rothschild (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2419-9881): Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Richard Njoroge: Investigation, Data curation

Edna Kibera: Investigation, Data curation

Moses Njenga: Software, Data curation

Faith Mbogo: Software, Data curation

Brian Musanga: Software, Data curation

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interest: Julius Njogu, Grace Jaworski, Christine Oduor, Alison Malmqvist, and Claire W. Rothschild are employees of Population Services International. Christine Oduor was involved in the Nena chatbot development. Aarons Chea has no competing interest that could have influenced evidence reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Higgins JA, Hirsch JS.. The pleasure deficit: revisiting the “Sexuality Connection” in reproductive health. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Allen L, Carmody M.. “Pleasure has no passport”: re-visiting the potential of pleasure in sexuality education. Sex Educ. 2012;12(4):455–468. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2012.677208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine M, McClelland SI.. Sexuality education and desire: still missing after all these years. Harv Educ Rev. 2006;76(3):297–338. doi: 10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruskin S, Yadav V, Castellanos-Usigli A, et al. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27(1):29–40. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John NA, Babalola S, Chipeta E.. Sexual pleasure, partner dynamics and contraceptive use in Malawi. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;41(2):99–107. doi: 10.1363/4109915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaneva M, Philpott A, Singh A, et al. What is the added value of incorporating pleasure in sexual health interventions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022, 2 February: 17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang KY, Kumar M, Cheng S, et al. Applying technology to promote sexual and reproductive health and prevent gender based violence for adolescents in low and middle-income countries: digital health strategies synthesis from an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1). doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08673-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stork C, Calandro E, Gillwald A.. Internet going mobile: internet access and use in 11 African countries. Info. 2013;15(5):34–51. doi: 10.1108/info-05-2013-0026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamopoulou E, Moussiades L.. Chatbots: history, technology, and applications. Mach Learn Appl. 2020;2:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.mlwa.2020.100006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laranjo L, Dunn AG, Tong HL, et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(9):1248–1258. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadarzynski T, Miles O, Cowie A, et al. Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: a mixed-methods study. Digit Health. 2019;5; doi: 10.1177/2055207619871808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abd-alrazaq AA, Alajlani M, Alalwan AA, et al. An overview of the features of chatbots in mental health: a scoping review. Int J Med Inform. 2019;132; doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.103978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grové C. Co-developing a mental health and wellbeing chatbot with and for young people. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11; doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.606041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crutzen R, Peters GJY, Portugal SD, et al. An artificially intelligent chat agent that answers adolescents’ questions related to sex, drugs, and alcohol: an exploratory study. J Adolescent Health. 2011;48(5):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Gupta S, Singhal A, et al. An artificial intelligence chatbot for Young People’s Sexual and Reproductive Health in India (SnehAI): instrumental case study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1). doi: 10.2196/29969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Migiro SO, Magangi BA.. Mixed methods: a review of literature and the future of the new research paradigm. Afr J Bus Manag. 2011;5(10):3757–3764. doi: 10.5897/AJBM09.082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upadhyay UD, Danza PY, Neilands TB, et al. Development and validation of the sexual and reproductive empowerment scale for adolescents and young adults. J Adolescent Health. 2021;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.https://www.ansirh.org/empowermentmeasures/sexual-and-reproductive-empowerment-scale-adolescents-and-young-adults-sre-aya. University of California San Francisco. Published 2020 [cited 2023 June 28]. Available from: https://www.ansirh.org/empowermentmeasures/sexual-and-reproductive-empowerment-scale-adolescents-and-young-adults-sre-aya

- 19.Dedoose Version 9.0.106, cloud application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Published online 2021

- 20.Fereday J, Adelaide N, Australia S, et al. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006. ;5(1):80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonsalves L, Wyss K, Cresswell JA, et al. Mixed-methods study on pharmacies as contraception providers to Kenyan young people: who uses them and why? BMJ Open. 2020;10(7): e034769. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corroon M, Kebede E, Spektor G, et al. Key role of drug shops and pharmacies for family planning in urban Nigeria and Kenya. Available from: www.ghspjournal.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ssewanyana D, Mwangala PN, Marsh V, et al. Young people’s and stakeholders’ perspectives of adolescent sexual risk behaviour in Kilifi County, Kenya: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(2):188–205. doi: 10.1177/1359105317736783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.KNBS . Kenya demographic and health survey 2014; 2014. doi: 10.4324/9781315670546 [DOI]

- 25.Cislaghi B, Shakya H.. Social norms and adolescents’ sexual health: an introduction for practitioners working in low and mid-income African countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22(1):38–46. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mwaisaka J, Wado YD, Ouedraogo R, et al. “Those are things for married people” exploring parents’/adults’ and adolescents’ perspectives on contraceptives in Narok and Homa Bay Counties, Kenya. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01107-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutea L, Ontiri S, Kadiri F, et al. Access to information and use of adolescent sexual reproductive health services: qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators in Kisumu and Kakamega, Kenya. PLoS One. 2020, 11 November: 15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunawardena N, Fantaye AW, Yaya S.. Predictors of pregnancy among young people in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(3). doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badawi MM, SalahEldin MA, Idris AB, et al. Knowledge gaps of STIs in Africa; systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones AC, Robinson WD, Seedall RB.. The role of sexual communication in couples’ sexual outcomes: a dyadic path analysis. J Marital Fam Ther. 2018;44(4):606–623. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noar S, Carlyle K, Cole C.. Why communication is crucial: meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J Health Commun. 2006;11(4):365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simuyaba M, Hensen B, Phiri M, et al. Engaging young people in the design of a sexual reproductive health intervention: lessons learnt from the Yathu Yathu (“For us, by us”) formative study in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1). doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06696-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. Pew research center. 2016;22(1):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Clief L, Anemaat E.. Good sex matters: pleasure as a driver of online sex education for young people. Gates Open Res. 2019;3:1480. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.13003.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Følstad A, Brandtzaeg PB.. Users’ experiences with chatbots: findings from a questionnaire study. Qual User Exp. 2020;5(1). doi: 10.1007/s41233-020-00033-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill J, Randolph Ford W, Farreras IG.. Real conversations with artificial intelligence: a comparison between human-human online conversations and human-chatbot conversations. Comput Human Behav. 2015;49:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]