Abstract

Over the last decades, theoretical perspectives in the interdisciplinary field of the affective sciences have proliferated rather than converged due to differing assumptions about what human affective phenomena are and how they work. These metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions, shaped by academic context and values, have dictated affective constructs and operationalizations. However, an assumption about the purpose of affective phenomena can guide us to a common set of metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions. In this capstone paper, we home in on a nested teleological principle for human affective phenomena in order to synthesize metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions. Under this framework, human affective phenomena can collectively be considered algorithms that either adjust based on the human comfort zone (affective concerns) or monitor those adaptive processes (affective features). This teleologically-grounded framework offers a principled agenda and launchpad for both organizing existing perspectives and generating new ones. Ultimately, we hope the Human Affectome brings us a step closer to not only an integrated understanding of human affective phenomena, but an integrated field for affective research.

Keywords: Affect, Framework, Enactivism, Allostasis, Feeling, Sensation, Emotion, Mood, Wellbeing, Valence, Arousal, Motivation, Stress, Self

1. Introduction

The affective sciences—the interdisciplinary study of affective phenomena, such as sensation, emotion, mood, and wellbeing—have their roots in neuroscience and psychology, but also intersect with philosophy, sociology, linguistics, anthropology, computer science, and economics (Ekman and Davidson, 1994; LeDoux, 1998; Panksepp, 2004; Davidson and Sutton, 1995; Damasio, 2005; Davidson et al., 2009; Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981; Sander and Scherer, 2014; Dalgleish et al., 2009; Gendron and Barrett, 2009, Adolphs and Anderson, 2018; Gross and Barrett, 2013; Keltner and Lerner, 2010; Gordon, 1990; Solomon, 1978; Lutz and White, 1986; Mesquita and Frijda, 1992; Beatty, 2014, 2019; Armony and Vuilleumier, 2013; Solomon, 1993; Goldie, 2009; Deonna and Teroni, 2012; Scarantino, 2016; Picard, 2000; Hoque et al., 2011; Calvo et al., 2015; Dukes et al., 2021). This interdisciplinary field seeks to explain the mechanisms of affective phenomena by inferring affective constructs from observable data in order to predict future effects (Mill, 1856; Whewell, 1858; Machamer et al., 2000; Glennan, 2002, 2008; Azzouni, 2004; Bechtel and Abrahamsen, 2005; Chang, 2005; Morganti and Tahko, 2017; Ivanova and Farr, 2020; Levenstein et al., 2023; Hempel and Oppenheim, 1948; Hempel, 1970; Kauffman, 1970; Glennan, 1996), a scientific endeavor that has gained traction in the last few decades and secured the rise of affective research (Dukes et al., 2021). This growth, however, has been accompanied by a surge in theoretical divisions: divergent academic communities differ in their background assumptions on the metaphysics of affective phenomena (i.e., what they are), (Marr, 2010; Danziger, 1997; Dayan and Abbott, 2005; Dixon, 2003, 2012; Solomon, 2008; Goldie, 2009; Deonna and Scherer, 2010; Izard, 2010a, 2010b; Gendron, 2010; Mulligan and Scherer, 2012; Barrett, 2012; Scarantino, 2012, 2016; Adolphs, 2017; Fox, 2018; Tappolet, 2022; Moors, 2022) which further distances their assumptions about the mechanisms of those phenomena (i.e., how affective phenomena arise) (Scherer, 2005; Bridgman, 1927; Chang, 2004; Levenstein et al., 2023). These assumptions frame the basic terms of a theory, such as each theory’s affective constructs, the scientific abstractions of affective phenomena that should be used (i.e., what should be studied), as well as their appropriate operationalizations, the methods of measuring those abstractions (i.e., how to observe them) (Hempel, 1952, 1970; Carnap and Gardner, 1966; Lewis, 1970, 1972). Even when assumptions are not explicitly disclosed, they are hidden in decision points at each stage of the scientific process meant to test that theory—from experimental design and methodology all the way to analysis and interpretation (Mill, 1856; Whewell, 1858; Azzouni, 2004; Chang, 2005; Morganti and Tahko, 2017; Ivanova and Farr, 2020; Scarantino, 2016; Fox, 2018). Thus, despite the field’s agreement that studying affective phenomena is important, discrepancies have yielded lasting theoretical debates, bodies of experimental work within separate frameworks have proliferated, and limited progress has been made in pruning or integrating existing frameworks with no clear consensus in sight (Kuhn, 1974, 2012; Box, 1976; Craver and Darden, 2013; Strevens, 2013; Levy and Bechtel, 2013; Woodward, 2014).

This persistence of theoretical splitting is in part due to empirical data being inadequate in arbitrating between sets of theoretical assumptions (Holton, 1975; Kuhn, 2012; Lakatos, 1978, 2014; Lowe, 2002; Notturno and Popper, 2014; Ormerod, 2009; Popper, 1963; Laudan, 1978; Godfrey-Smith, 2021). Such disagreements can only be settled by examining each camp’s take on theoretical virtues (i.e., what qualities make good framework and resulting theory), and comparing each theory’s underlying sets of assumptions (Galilei, 1953; Newton, 1999; Einstein, 1934; Achinstein, 1983; Duhem, 1982; Sober, 2015; Poincaré 2022; Schindler, 2018; Keas, 2018; Ivanova and Farr, 2020). In addition, proponents of different theories with separate overarching frameworks differ in their assumptions about why certain affective phenomena are scientifically important—why their particular versions of the phenomena should be studied and why their methods of observation should be used (Bromberger, 1966; Achinstein, 1983; De Regt and Dieks, 2005; Kitcher, 2001; Brown, 2010; Dayan and Abbott, 2005; Kording et al., 2020; Levenstein et al., 2023). These pragmatic motivations tend to be prone to biases, such as which research tradition has been status quo in a proponent’s local context, which methods for observation are practical, which types of observational data are accessible, and which questions about affective phenomena are of interest to certain audiences (Ivanova and Farr, 2020; Duhem, 1982; Lowe, 2002; Ivanova, 2014, 2017; Paul, 2012; Ladyman, 2012; Latour and Woolgar, 2013; Achinstein, 1983; van Fraassen, 1980). Therefore, when evaluating sets of assumptions, collaboration across proponents of different camps and members of different disciplines can go a long way in shoring up these theoretical blind spots (Table 1) (Wray, 2002; Andersen and Wagenknecht, 2013; Callard and Fitzgerald, 2015; MacLeod, 2018).

Table 1. Domains of Assumptions Shaping Scientific Frameworks and Resulting Theory.

This table summarizes domains of theoretical assumptions for scientific frameworks which shape the scientific theories resulting from them. As a case study, we highlight the framework of assumptions for Affect-as-Information Theory, to provide an exemplar in affective research. The first two rows correspond to domains of assumptions embedded in our individual contexts as affective researchers; the latter rows are the assumptions about affective phenomena themselves. Each unitalicized domain forms the basis of the italicized domain following it. Finally, the last row, indicated in bold, corresponds to the collective of all the domains of assumptions above it.

| Domain of Assumptions (collectively, framework) | Description | Relationships between Domains of Assumptions | Shorthand | Exemplar in Affective Research Affect-as-Information Theory (Schwarz and Clore, 1983, 2003; Clore et al., 2001; Schwarz, 2012) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pragmatics | assumed context-dependent motivation for the study of theoretical constructs | Shapes metaphysics and mechanism and, therefore, determines construct and operationalization. | why a construct should be studied and why a certain operationalization should be used to study it | Affect should be studied as information, by observing its effect on judgments, to situate subjective experience in decision-making. |

| Theoretical virtues | assumed desiderata for what makes good framework and theory (e.g., parsimony, elegance, simplicity) | shaped by aesthetic preferences; frames how theory that applies construct and operationalization is evaluated | why an explanation of a phenomenon is good | Characterizing affect as information provides parsimonious explanation for its influence on decision-making. |

| Metaphysics | assumed nature of phenomenon | shaped by pragmatics | what the phenomenon is | One set of studies testing affect-as-information theory examines mood as an influence on decision-making. |

| Construct | assumed abstraction of phenomenon | shaped by pragmatics, metaphysics, and (sometimes) operationalization; | what construct is studied | Mood is construed as ranging from positive to negative. |

| Mechanism | assumed process of phenomenon | guided by pragmatics and metaphysics | how phenomenon arises | In the mechanism of mood functioning as information, positive valence biases positive judgment and negative valence biases negative judgment. |

| Operationalization | assumed measurement of abstracted phenomenon | guided by pragmatics, construct, and mechanism | how construct is observed | Overall positive to negative mood was manipulated by prompting recall of happy or sad events. |

| Teleology | assumed purpose of the phenomenon existing | determined by pragmatics; motivates metaphysics and mechanism | why phenomenon exists | Affect-as-information theory suggests that mood functions as information in order to indicate benign or problematic environment. |

| Framework (or paradigm) | a set of the above domains of assumptions; terms used to articulate and organize testable theories | usually explicitly or implicitly consists of all of the above | all of the above | All of the above |

Even if comprehensive collaboration on scientific incentives and theoretical virtues could be achieved, it would be unproductive to compare the metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions governing affective research without a premise of why affective phenomena exist in the first place—i.e., a teleological assumption (Deacon, 2011; Mayr, 1985; Levenstein et al., 2023). A framework grounded in a principle for the purpose of affective phenomena would allow us to (1) bridge across metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions behind different theories, (2) organize theories with respect to that teleological principle, and (3) evaluate theories in light of scientific motivations and theoretical virtues (Craver, 2007; Schindler, 2018; Keas, 2018; Levenstein, 2023). Therefore, to truly achieve an integrated understanding of affective phenomena, collaborative and interdisciplinary efforts should aim to integrate scholarly and theoretical values in order to synthesize a common set of metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions grounded in teleological principle—a framework with which to articulate and organize theories for conducting affective research as well as compare and integrate existing ones (Popper, 1963; Kuhn, 2012; Holton, 1975; Lakatos, 2014, 1978; Laudan, 1978; Lowe, 2002; Ormerod, 2009; Jabareen, 2009; Notturno and Popper, 2014; Godfrey-Smith, 2021).

In this capstone paper, we conclude the special issue “Towards an Integrated Understanding of the Human Affectome” (Cromwell and Papadelis, 2022, this issue) by synthesizing the various assumptions ruling different affective fields and camps into a common teleologically-grounded set: the Human Affectome (Cromwell and Lowe, 2022, this issue). To get to this point, 173 researchers from 23 countries came together as a global, interdisciplinary taskforce to examine existing assumptions and approaches in the study of affective constructs. As a preliminary step, a team within this working group performed an exploratory computational linguistic analysis: identifying 3664 words for feelings, sorting them into feeling categories, and characterizing more specific senses for each word (Siddharthan et al., 2018). Guided by the themes that emerged from that initial exploration, twelve teams went on to produce the twelve reviews of this special issue. Each review summarized the state of current behavioral and neuroscientific research with special emphasis on theoretical concerns (this issue: Arias et al., 2020; Raber et al., 2019; Becker et al., 2019; Pace-Schott et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2020; Cromwell et al., 2020; Dolcos et al., 2020; Stefanova et al., 2020; Alia-Klein et al., 2020; Frewen et al., 2020; Alexander et al., 2021; Eslinger et al., 2021; Cromwell and Papadelis, 2022). Thus, the initial linguistic approach encouraged an exploratory, yet integrative approach in reviewing the sampling of theoretical perspectives across the affective domains. However, these themes have yet to be considered holistically by the taskforce from a top-down perspective: how can the metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions in the affective sciences be rooted in common teleological principles to motivate shared scientific constructs and operationalizations, and frame consequent testable theories? (Machamer et al., 2000; Craver, 2007; Bechtel, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2013; Bechtel and Richardson, 2010).

In what follows, we probe the question of purpose: why are there affective phenomena? We synthesize a common set of teleological principles to guide the metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions and, ultimately, motivate shared scientific constructs and operationalizations. What we offer here is not another theory, nor is it a history or review of the field—it is a scaffold of premises that accommodates existing theories by organizing them in terms of a common set of assumptions, and promotes the articulation of new theories. Thus, this synthesis can facilitate a better understanding of assumptions, differences, and possible cohesion among perspectives in the field. We hope that you, reader, whether you are an affective neuroscientist, philosopher of emotion, cognitive psychologist, computational psychiatrist, clinician, or another interested in affect, will take something away from this synthesis. We recommend not to treat this work as the ultimate answer to the long-lasting debates the field has been entrenched in, but as the beginning of the incremental untangling of assumptions in a principled way toward a new integrative paradigm. Practically speaking, we encourage you to start with your own work—to situate your explanatory goals within the Human Affectome, relate them to other theories based on principles distilled by this synthesis, and articulate your future theories and accompanying hypotheses using these teleological terms. Ultimately, we hope that the wider community of affective sciences leverages this cohesive framework to generate and test more specific theories and hypotheses on the basis of its premises—so that in due course we will build a concrete, comprehensive, and, most importantly, principled set of affective constructs and operationalizations (analogous to Schuler et al., 1996, and Sporns et al., 2005). In this manner, this rich and sprawling field can come to an integrated understanding of human affective phenomena within which to situate past and future research.

2. Teleological Principle: Why are there human affective phenomena?

Among the affective sciences, we are united by our interest in phenomena that are subjectively felt, have neurobiological basis, influence decision-making and behavior, and can be expressed through implicit and explicit means (Darwin, 1965; James, 1890; Scherer, 1984; Leighton, 1985; Frijda, 1986; Clore and Ortony, 1988; Schwarz and Clore, 1988, 2007; Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981; Solomon, 1993; Ekman and Davidson, 1994; LeDoux, 1998; Panksepp, 2004; Pugmire, 1998; Davidson and Sutton, 1995; Cacioppo et al., 1999; Panksepp, 2004; Damasio, 2005; Davidson et al., 2009; Sander and Scherer, 2014; Dalgleish et al., 2009; Goldie, 2009; Deonna and Scherer, 2010; Keltner and Lerner, 2010; Hoque et al., 2011; LeDoux, 2012, 2015, 2023; Deonna and Teroni, 2012; Schwarz, 2012; Damasio and Carvalho, 2013; Gross and Barrett, 2013; Armony and Vuilleumier, 2013; Elpidorou and Freeman, 2014; Ekman, 2016; Scarantino, 2016; Deonna and Teroni, 2017; LeDoux and Brown, 2017; Adolphs and Anderson, 2018; Adolphs et al., 2019; Dukes et al., 2021). Our differing interpretations of those metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions, however, generate an expansive range of constructs and operationalizations, and resulting theories and hypotheses. Therefore, these assumptions require a teleological principle to be reduced and systematized. In this section, we will progress from the broadest purpose of an organism to the most specific principle in humans, in order to synthesize metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions for complete coverage of human affective phenomena: the Human Affectome.

2.1. To ensure viability

An organism can be considered a system or network of interconnected parts collectively and continuously (re)generating and distinguishing itself, with the ultimate purpose of autonomously ensuring its own persistent recreation and integrity (autopoiesis) (Jonas, 1973; Maturana and Varela, 1991; Varela et al., 1974, 2017; Varela, 1979; Weber and Varela, 2002; Di Paolo and Thompson, 2014). This involves recursively creating its own components, so that those components can both sustain the processes producing them as well as maintain their coordination such that, altogether, they are an organization distinct from an environment—that is, the organism. Each of these processes enables others within the system, such that they collectively support themselves and will disintegrate if even one is disrupted (Beer and Di Paolo, 2023). This dependence entails the entire neurobiological system staying within a narrow range of states, such as a specific set of glucose levels, temperature, pH, etc. (homeostasis) (Cannon, 1929; MacArthur, 1955). Therefore, the primary purpose of an organism is to ensure its own viability, where being an organism can be considered a collective inherent act of self-generating and self-distinguishing itself into continuous being through error-correcting means (Wiener et al., 2019). This helps us understand what neurobiological processes are doing at large—but more importantly for our purposes, this is our launchpad for tracing the purpose of human affective phenomena (Damasio and Carvalho, 2013; Panksepp, 2004, 2005; Strigo and Craig, 2016).

2.2. To execute operations

Complex organisms execute many varied operations to ensure viability in the face of complex and changing environments. The capacity to discern more than just a handful of facets of the environment usually goes hand-in-hand with the capacity for many dimensions of action (Tooby and Cosmides, 1990, 2008; Cosmides and Tooby, 2000, 2013). This complexity poses more risks to viability, but also allows for flexibility when circumstances change. Such a complex organism cannot afford to let any one of the many elements push its system to the brink or it risks collapse (i.e., resulting in the organism dissolving, dying, ceasing to be). The complex organism does not remain idle but rather triumphs by doing the opposite: instead of remaining in a simplistic stable state, it moves between levels of relative stability (attractor states). When a perturbation to its ongoing organization approaches, the complex organism does not immediately address the breach, the way simpler life forms reset to more suitable states when an error is detected (Pereira, 2021). Instead, it acts in the direction of that breach so that, even if its actions temporarily make things worse, the organism will be on better footing in the future (Rosenblueth et al., 1943; Ruiz-Mirazo and Moreno, 2012; Boone and Piccinini, 2016; Williams and Colling, 2018; Fingelkurts and Fingelkurts, 2004). It preempts and prepares, choosing between different courses of action to anticipate and prevent a potentially fatal state brought on by the changing aspects of the environments before that point arrives (allostasis) (Sterling and Eyer, 1988; Carpenter, 2004; Cooper, 2008; McEwen and Wingfield, 2003; Sterling, 2012, 2020; Sterling and Laughlin, 2015; Schulkin and Sterling, 2019; Moors and Fischer, 2019).

For the complex organism, there are many, sometimes equally effective, ways to ensure viability, but all require operation. Some courses of action address metabolic intolerance more directly (e.g., raising food to one’s mouth for consumption), while others require further intermediary steps (e.g., buying groceries) (Jonas, 2001). However, not all processes, especially in more intricate sequences, involve interacting with the external environment. Internal adjustments are what orchestrate the necessary shifts in approach to the environment—everything from attention to planning (mental action) (Kirsh and Maglio, 1994; Mele, 1997; Peacocke, 2006; Soteriou, 2013; Metzinger, 2017; Dolcos et al., 2020, this issue), serving as the bridge between the processes receiving inputs and those causing behavioral outputs, and enabling these two capacities to guide each other (sensorimotor) (O’Regan and Noë 2001; Di Paolo et al., 2017). Collectively, these processes move the organism around a new set of states wherein the organism is comfortable—each state as a position on one of many dimensions of anticipated deviation from viability, addressable in many actionable ways (Panksepp, 2010; Cromwell and Lowe, 2022, this issue). This ‘comfort zone’ guides the adaptive use of a repertoire of operations, whose individual actions consider future possibilities (Moors and Fischer, 2019; Cromwell et al., 2020, this issue). To navigate this comfort zone, an organism needs the capacity to monitor how it is faring with respect to the multidimensional, continuous, and fluctuating norm—an implicit form of self-evaluation. That evaluation allows the organism to consider its tools of internal and external processes in order to deploy them to safeguard viability. Sometimes, the organism’s adaptive capabilities are surpassed in a way that strains its processes (Karastoreos and McEwen, 2011; Peters et al., 2017). Exceeding the comfort zone too often can result in pervasive damage to proactive processes (allostatic load) (McEwen, 1998, 2000). Therefore, beyond viability, the purpose of cognitive processes in complex organisms is to execute operations, which naturally involves managing them.

2.3. To enact relevance

Affective phenomena, to both academics and laypeople, can be felt (Chalmers, 1997; Craig, 2002; Frijda, 1986; Lambie and Marcel, 2002; Lange, 1885; Leighton, 1985; Nagel, 1974; Pugmire, 1998; Scherer, 1982b; Schwarz and Clore, 2007; James, 1890; Schwarz and Clore, 1988; Panksepp, 2008; Barrett, 2005; Barrett et al., 2007; Izard, 2010b; Deonna and Scherer, 2010; Schwarz, 2012; Damasio and Carvalho, 2013; Elpidorou and Freeman, 2014; Deonna and Teroni, 2017; LeDoux and Brown, 2017; Strigo and Craig, 2016; LeDoux and Hofmann, 2018; Adolphs et al., 2019; Paul et al., 2020; LeDoux, 2012, 2015, 2023; Szanto and Landweer, 2020; Álvarez-González, 2023; Davidson and Sutton, 1995; Cromwell and Lowe, 2022, this issue; Cromwell and Papadelis, 2022, this issue). We experience them over a duration of time (episodes) (Tye, 2003; Wollheim, 1999; Goldie, 2000; Locke, 1847; Levine, 1983; Hardin, 1988; Stein et al., 1993), how they feel has qualities (qualia) (Nagel, 1974; Chalmers, 1997; Silva, 2023), and they tend to mean something to us when we feel them, usually about how our concerns relate to objects, either physical or mental, such as things, people, and situations (intentionality) (Brentano, 2012; Tye, 2014; Deonna and Teroni, 2012). This aspect of meaning obliges us to consider not only the meaning of each individual affective experience, but also how different meanings of affective experiences relate to each other in an organized way (phenomenology) (Heidegger, 1967; Husserl and Dummett, 2001; Merleau-Ponty, 2011; Dreyfus, 1972; Sartre, 2022). A useful starting point for understanding why affective experiences exist would, therefore, be to ascertain how the structure in felt meaning relates to the entire system of neurobiological processes—including both those within the organism and those interacting with the environment (Horgan and Tienson, 2002; Strawson, 2004; Kriegel, 2014).

One major clue that the structure of affective experiences gives us is that they originate from a first-person perspective (self) (Descartes, 1644; Husserl, 2013; Kant, 1908; Searle, 1992; Shoemaker, 2003; Wittgenstein, 1958; James, 1890; Gallagher, 2000; Metzinger, 2003a, 2003b; Ochsner and Gross, 2005; Blanke and Metzinger, 2009, 2013; Christoff et al., 2011; Zahavi and Kriegel, 2015; Colombetti, 2011; Frewen et al., 2020, this issue). On the mechanistic side of things, this perspective seems to arise from the organism adeptly executing operations in order to ensure viability from a unified point of view (i.e., self). Being guided by a comfort zone means that all of the organism’s considerations are driven by potential for action such that properties of the environment perceived and acted upon are features of action-worthiness (affordances) (Bourgine and Stewart, 2004; Stewart, 2010; Gibson, 1977; Teroni, 2007; Frijda, 1986). From the perspective of the organism, the world appears to it only in a manner relatable to its capacities (perceived surroundings or umwelten) (Uexküll, 2013; Sebeok, 2001; Chang, 2009; Feiten, 2020). If we want to be precise in studying affective mechanisms, we should not just look at the brain—we should consider the entire nervous system and the rest of the body (embodied) (Barsalou, 1999; Barsalou, 2003; Pfeifer and Bongard, 2006; Varela, 1997; Chemero, 2011; Gallagher and Zahavi, 2020; Fuchs, 2017). Among internal processes, the felt aspect of signals from our internal viscera is an important factor to consider given how often bodily sensations characterize affective experiences (interoception) (Craig, 2008; Sel, 2014; Critchley and Garfinkel, 2017; Tsakiris and Preester, 2018). However, if we fixate too much on what’s going on inside, we miss the dynamic interplay between an organism and its environment (embedded) (Beer, 2014), which shapes the organism’s adaptive capacities and gives it its perspective (situated) (Roth and Jornet, 2013; Walter, 2014; Dawson, 2014; Stephan and Walter, 2020). Having that central comfort zone in mind is what gives the organism the imperative to make sense of the world through perception, as well as affect the world through action to make sense of it (sense-making) (Di Paolo, 2005; Colombetti, 2010). Therefore, underpinned by their prospective concern for viability, and at the heart of the cognitive activity that defines them, complex organisms such as humans enact relevance for themselves—by not only taking in what is relevant but also by purposefully creating relevance (enactive) (Colombetti and Thompson, 2008; Colombetti, 2014; Ward, 2017; Newen et al., 2018; Cromwell et al., 2020, this issue). When that activity is challenged, the organism’s awareness of its own comfort zone is, from its perspective, prioritized as intense feeling to orient it to more adaptive options for action (stress) (Averill, 1973; McEwen, 1998, 2005; Koolhaas et al., 2011; McEwen and Akil, 2020). Thus, our teleological foundation of affective phenomena seems to require this organism’s emergent capacity to find things meaningful based on their actionability.

2.4. To entertain abstraction

Humans are not limited to affective processes that reflect our first-person needs of the current moment. While not fundamental to all affective phenomena, concerned foresight poses at least some detachment from the present and, therefore, enables a rudimentary form of abstraction (Neisser, 1963; Plutchik, 1982; Clore and Huntsinger, 2009; Plutchik and Kellerman, 2013). An object in the present context can be tied to some distant meaning, being associated with operations not presently executed. This form of practical symbolism is still grounded in proactive operation in the service of viability (Tenenbaum et al., 2011). This capacity for abstraction is often overlooked when painting a picture of affective phenomena. However, when it comes to humans in particular, this abstract capacity is essential as it enables us to reflect on our adaptive activities in general (especially when we are not concurrently exercising them) as well as enact relevance that is abstract. This equips us as humans with the capacity to consider adaptive operations while departing from our individual first-person perspective. We can imagine other origins of concerned perspective, starting with that of other individuals—inferring how they are oriented actionably toward the world (theory of mind) (Saxe, 2006; Brüne and Brüne-Cohrs, 2006; Mehrabian and Epstein, 1972; Smith, 2006; Cuff et al., 2016; Fotopoulou and Tsakiris, 2017). As a result, we can share an orientation toward the environment with others such that we can complement each other’s operations. This shared perspective enhances our adaptivity, expanding our operational repertoires to include cooperation and collaboration (Dunbar, 1998; Lakin et al., 2003; De Jaegher and Di Paolo, 2007; Gray et al., 2007; Fischer and Manstead, 2008, 2016; Weisman et al., 2017; Nummenmaa et al., 2018; Williams, 2020; Tomasello, 2020, 2022). Beyond this social competence, we can conceive of origins of operations other than those driven by viability: anything, animate or inanimate, can seem like it has an effect. This explodes into possibilities of conceptualizing the significance of events, situations, ideas—over and above the collective activities of many individuals, that is, groups.

These expansions to abstraction do not only grant us the capacity to associate any process of animate or inanimate change with designated labels (language) (Wittgenstein, 1953; Itkonen, 1978; Pinker, 2010; Perniss and Vigliocco, 2014; Adolphs, 2017; Adolphs and Andler, 2018) but also give us the adaptive reason to do so. Labelling specific abstract activities in our operations greatly influences what operation is possible, determining where we are in our comfort zone (Whissell, 1989; Besnier, 1990; Barrett et al., 2007; Lindquist, 2021; Colombetti, 2009). Our communication is not merely an add-on to what we enact or an after-thought to what we feel. Expression of what we feel through bodily, vocal, or visual means carves the kind of relevance we are able to enact, consequently, constraining the feeling itself (Williams et al., 2020, this issue; Wharton et al., 2021; Wharton and de Saussure, 2023). The comfort zone is so inherent to us that we project that orientation of relevance to others, assigning perspective to both the animate and inanimate, to make events unfamiliar to us part of our world of relevance. This results in us assuming things have purpose or direction even when they don’t, including people, objects, events, or even ideas, as long as they look like they do (intentional stance) (Dennett, 1989; Brooks, 1991; Villalobos and Ward, 2015; Hutto and Satne, 2015; Hutto and Myin, 2017; Csibra and Gergely, 2007). Although this projection can seem futile, it allows us to articulate statements about not only our own concerns but also the hypothetical concerns of abstract objects (propositional attitudes) (Frege, 1948; Russell, 1905). This can be useful in that these articulations can match their targets in varying degrees of better or worse, making them more or less useful.

It’s no surprise then that reality that is mapped poorly is difficult for us to operate in (misrepresentation) (Searle, 1983; Grice, 1957; Papineau, 1984; Millikan, 1987, 1989; Neander, 1995; Godfrey-Smith, 2006). In cases of psychopathology especially, we can be very off (Beck, 1971; Leventhal and Diefenbach, 1991; Cummins, 2010). This usually becomes obvious in faulty communication with others, or when our operations prove to be ineffective (Burge, 2010; Izard et al., 2008). Abstractions provide the means to articulate mental processes in verbal language, mathematical symbols, or code (cognitive science) (Stillings et al., 1995; Eckardt, 1995; Clark, 2000; Thagard, 2005), such as what is happening when individuals have trouble navigating the environment in light of their comfort zone, as they are mapping either or both poorly. We can articulate such maladaptive mechanisms and use these labels to predict future outcomes of those individuals’ subjective operations (computational psychiatry) (Egan, 2018, 2020; Shin and Liberzon, 2010; Maia et al., 2017; Petzschner et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2021; Friston, 2023; Hitchcock et al., 2022; Hoemann et al., 2021). Taken together, there is much more associated with affective phenomena in humans than mere adaptive enaction of relevance. We cannot neglect our human capacity to entertain abstraction as it determines the versatility of our comfort zone.

Synthesizing the academic interests from different corners of the field, we have now built the teleological principle of human affective phenomena, illustrating how each purpose grounds the next. We began with root of purpose of a neurobiological organism—to ensure its viability. From there, we acknowledged the purpose of a complex organism—to execute operations in the service of its viability. We then explored the purpose of an organism’s basic mental capacities—to enact its own relevance by executing operations for the sake of its viability. Finally, we discussed the purpose of conceptual capacity typical in humans—to entertain abstraction, when enacting relevance, by executing operations, to ensure our viability. To answer the question—why are there human affective phenomena?—using only one of these rationales seems incomplete: human affective phenomena collectively exist to serve these nested, intertwined purposes. Only together do these purposes account for all human affective phenomena. Therefore, guided by this teleological principle, we are now poised to articulate assumptions about what human affective phenomena are and how they work to construct our integrated framework: the Human Affectome.

3. The Human Affectome: What are human affective phenomena?

The term ‘affect’ has traditionally referred to the collective phenomena of feeling, sensation, emotion, mood, wellbeing, etc. Here, we use it to refer to the phenomena of a human organism affecting their environment and being affected by that environment, such that they are enacting their particular relevance in the world by executing operations with respect to viability. This intrinsic teleological foundation, synthesized from a comprehensive sampling of perspectives in the field of affect, can guide a principled set of metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions, resulting in an integrated framework for understanding human affective phenomena (Table 2).

Table 2. Affective Concerns and Features.

This table describes two sets of algorithms among affective phenomena—affective concerns and features—providing examples and their theoretical rationale. Each phenomenon’s computational problem is also specified, as well as algorithmic solutions existing in the field already.

| Affective Phenomenon | Examples | Theoretical Rationale | Computational Problem | Existing Algorithmic Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFFECTIVE CONCERNS inference of objects as actionable and thus relevant, which is reflected in the felt implication of those objects | physiological, operational, global |

Intentionality: feelings are about something (Frege, 1948; Russell, 1905; Dennett, 1989; Bedford, 1956; Brentano, 2012; de Sousa, 1990; Kenny, 2003; Leighton, 1985; Pitcher, 1965; Teroni, 2007; Deonna and Teroni, 2012; Clore and Huntsinger, 2009) Embodiment and Enactivism: all cognition is encoded as action (Varela et al., 2017; Colombetti and Thompson, 2008; Shargel and Prinz, 2017; Slaby and Wüschner, 2014; Hufendiek, 2015; Hutto, 2012) Affordances: the environment provides actionable meaning for the organism (Gibson, 1977) Motivation Theories: feeling states as motivational (Duffy, 1957; Frijda, 1986, 2017; Hommel et al., 2017) |

how to infer relevance of objects | Bayesian: using observable (interoceptive or exteroceptive) sensory data to infer and update the non-observable meaning (hidden or latent conditional probabilistic states) of those sensory data (Barrett, 2017; Dayan et al., 1995; Doya, 2007; Friston et al., 2016; Knill and Pouget, 2004; Lee and Mumford, 2003; Neal, 2012; Seth, 2013; Seth and Friston, 2016; Smith et al., 2019; Wolpert et al., 1995; Palacios et al., 2020) |

| Immediate to Distal gradient of relevance according to the distance from metabolic impact that the actions demanded would have (i.e., complexity, timescale, abstractness) | physiological, operational | Evolutionary and Biological Theories: courses of action can be more immediate or more distal (Jonas, 2001) | how to organize needs with varying extents of actionability | Bayesian: hierarchical inference with varying levels of complexity, timescale, or abstractness; immediate concerns are hidden states inferred at a lowest level and distal concerns are those at the highest (Pezzulo et al., 2015; Pezzulo and Levin, 2016; Pezzulo et al., 2022) |

| Physiological concerns require the most immediate or concrete actions | nourishment (hunger), hydration (thirst), internal integrity (nauseous); sensation | Interoception and Homeostasis: internal state as indicative of homeostatic status (Craig, 2002, 2013; Pace-Schott et al., 2019, this issue) | how to address immediate needs |

Reinforcement Learning: reflexive decision-making in reinforcement learning (i.e., model-free; van Swieten et al., 2021); pain as aversive prediction errors (Roy et al., 2014) Bayesian: fatigue as metacognitive inference (Stephan et al., 2016) |

| Operational concerns range from proximal to distal, wherein an organism has a feeling toward an object that, if acted upon, has proximal to eventual metabolic impact | safety (joy, happiness, exhilaration), danger (fear, worry, dread), obstruction (frustration, annoyance, anger), loss (disappointment, sadness, grief), epistemic (curiosity, intrigue, fascination), cooperation (care, love, belonging, trust, empathy), moral (pride, admiration, shame, moral disgust), aesthetic (awe, appreciation, beauty); emotion |

Evaluative or Action-Oriented Theories: feelings or emotions are evaluation of readiness for action (Dewey, 1895; Frijda, 1986, 2017; King, 2009; Deonna et al., 2015; Deonna and Teroni, 2012, 2015; Scarantino, 2014, 2015; Simon, 1967; Tooby and Cosmides, 1990, 2008; Clore and Palmer, 2009; Seth, 2013; Oatley and Johnson-Laird, 2014; Bach and Dayan, 2017; Atzil and Gendron, 2017; Hommel et al., 2017; Hommel, 2019; Suri and Gross, 2022; Quadt et al., 2022; Del Giudice, 2021) Basic and Discrete Appraisal Theories: differentiating emotion types by respective evaluations (Kragel and LaBar, 2016; Adolphs, 2017; Ekman and Cordaro, 2011; Lazarus, 2001; Roseman and Smith, 2001; Izard, 2007; Levenson, 2011; Panksepp and Watt, 2011; Scherer et al., 2010) Dimensional Appraisal Theory: infinite combinations of concerns differentiate an infinite typology of emotions (Grandjean and Scherer, 2008; Scherer, 2009; Scherer and Moors, 2019; Lerner and Keltner, 2000, 2001) Constitutive Appraisal Theory: emotions are these evaluated concerns (Clore and Ortony, 2000, 2013; Ortony et al., 1988) Constructionist Theories: emotions are constructed from lower-level ingredients (Damasio, 2003; Russell, 2003; Barrett, 2017; LeDoux, 2012) |

how to address proximal to distal needs | Affective Computing, Reinforcement Learning, and Bayesian: models for differentiating between emotions (Gratch and Marsella, 2004; Scherer et al., 2010; Broekens et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2021; Marsella and Gratch, 2009; Marsella et al., 2010; Poria et al., 2017; Bach and Dayan, 2017; Sennesh et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2019). |

| Global summative adaptive states | trajectory, optimization | Constructionist Theory: summarizing overall organism state (LeDoux, 2012) | how to characterize own adaptive performance across time | See below. |

| Trajectory the direction of adaptation with regard to comfort zone | positive, negative; mood | Philosophical Theories: increased likelihood of positive/negative occurrences (Price, 2006; Railton, 2017) | how to characterize local direction of environment |

Reinforcement Learning: momentum or trajectory of reward and punishment prediction errors (Eldar et al., 2016) Bayesian: mood as hyperpriors (Clark et al., 2018) |

| Optimization optimal match between the organism and the environment | low, high; wellbeing | Life Satisfaction: global evaluation of one’s life (Schwarz and Strack, 1999; Strack et al., 1991; Diener and Ryan, 2009; Diener, 2009; Diener et al., 2009; LeDoux, 2012; Krueger and Schkade, 2008; Maddux, 2017; Oishi et al., 2020) | how to recognize best adaptive performance across an extensive period of time |

Bayesian: maximizing momentary valence—using momentary judgments of adaptiveness to evaluate global optimality in adaptiveness (Smith et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2022) Information Theory: flow as mutual information (Melnikoff et al., 2022) |

| AFFECTIVE FEATURES momentary information on the adaptive process | valence, arousal | Allostasis: measures of predicted homeostatic need (Cannon, 1929; Cooper, 2008; Sterling and Eyer, 1988; Carpenter, 2004; McEwen and Wingfield, 2003; Sterling, 2012, 2020; Schulkin and Sterling, 2019; Sennesh et al., 2022) | how to characterize momentary status of adaptive process | See below. |

| Valence metric of evaluation of goodness or badness | positive, negative |

Core Affect: valence as ubiquitous across all affective experience (Russell et al., 1989; Russell, 2003; Posner et al., 2005; Kuppens et al., 2013) Philosophical Theory: minimal metacognition in self-assessment of own adaptiveness (Van de Cruys, 2017) |

how to characterize momentary suitability for organism’s adaptivity |

Reinforcement Learning Implementation: predicted rewards and punishments as ‘happiness’ (Rutledge et al., 2014) Bayesian Implementation: organism’s predictive evaluation of its adaptiveness or preparedness for its environment (Hesp et al., 2021) |

| Arousal metric of activation of various systems | low, high |

Core Affect: arousal as ubiquitous across all affective experience (Russell, 2003; Russell et al., 1989; Posner et al., 2005; Kuppens et al., 2013) Wakeful, Sexual, Autonomic, Physical, and Affective Arousal Theories: activation can occur within different systems at different levels (Duffy, 1957; Zuckerman, 1971; Pribram and McGuinness, 1975; Thayer, 1978; Robbins and Everitt, 1995; Robbins, 1997; Cahill and McGaugh, 1998; Jones, 2003; Eysenck, 2012; Satpute et al., 2019; Satpute et al., 2019; Neiss, 1988; Griffiths, 2013) |

how to characterize momentary activation of system | Vigor: effort as an outcome of arousal (Niv et al., 2007) |

Affective phenomena, being phenomena, are processes, both felt and mechanistic. While they are but a tangle among all the tightly interconnected dynamic processes of a human neurobiological system, we can carve up any set of those processes. When isolated, these processes can be described as algorithms, sequences of steps articulable in words, equations, or code that are executed for specific goals or to solve particular computational problems (Suppes, 1969; Cartwright, 1983; Marr, 2010; Pylyshyn, 1986; Rapaport, 2012; Vardi, 2012; Hill, 2016; Dennett, 2002; Chalmers, 2012; Egan, 2017, 2020). For our purposes, the processes we are most interested in are grounded by the teleological principle above, so that we can identify types of problems among affective phenomena and articulate how affective mechanisms attempt to solve them.

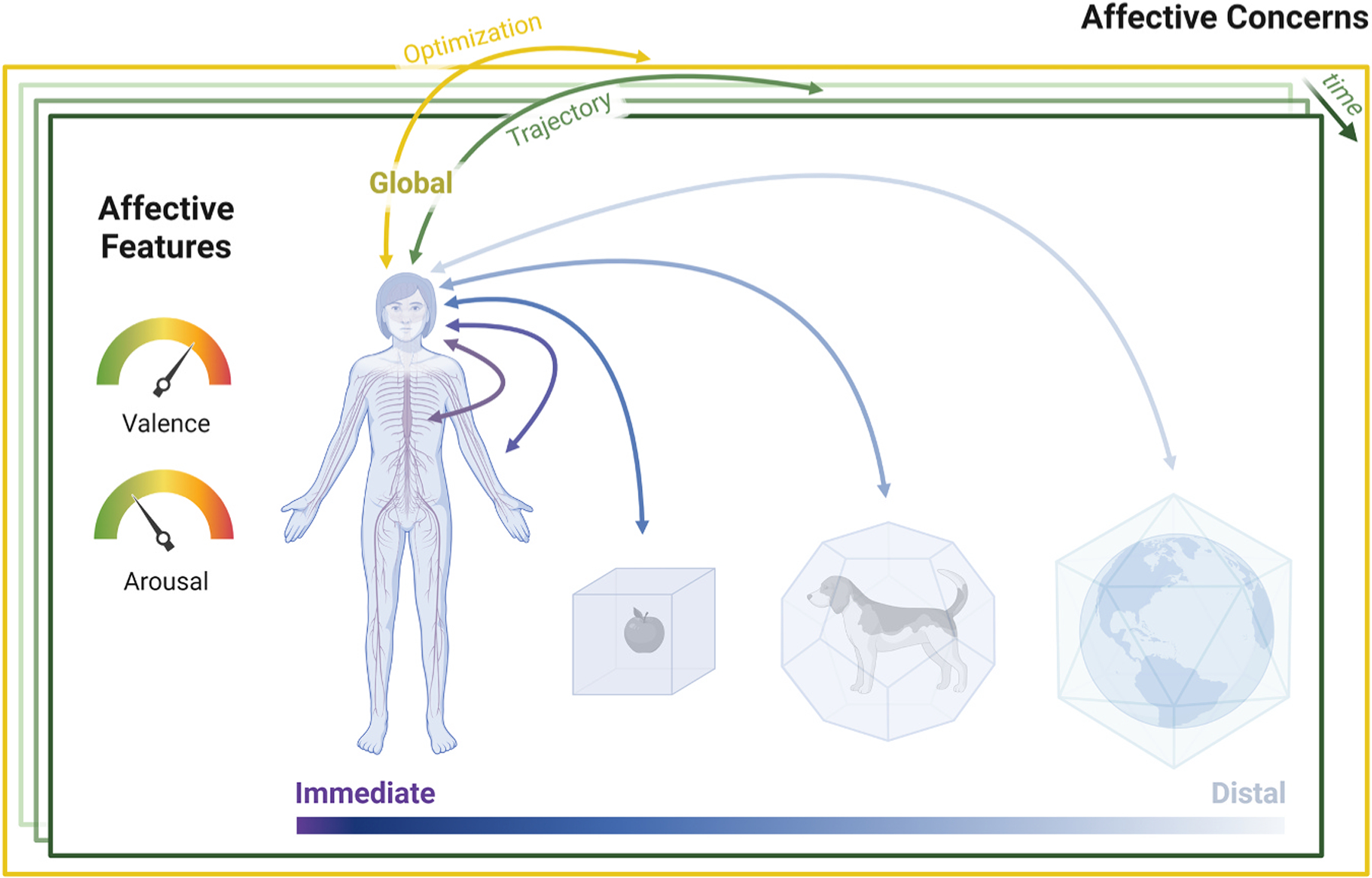

All human affective phenomena are situated in both experience and mechanism from the perspective of the human organism. We distinguish between algorithms that address the relevance of a physical or mental object to the organism, and the algorithms that monitor that adaptation (Fig. 1). Thus, affective phenomena include the two sets of processes below:

Algorithms reflecting affective concerns are processes that address the relevance of physical and mental objects, including things, people, and situations. These concerns signify what is of interest in affective experiences and are reflected in the felt actionability toward that object. These include concerns that have immediate to distal or global relevance to the organism. Several affective concerns can be active at the same time to make up any present moment’s total experience.

Algorithms reflecting affective features are processes that provide information on the adaptive process itself. They are the dimensional metrics of the organism’s own performance in adaptation, integral to all affective concerns, and are reflected in qualitative aspects of affective experience. These include valence and arousal. These features are always present as they mark affective concerns, providing information on them.

Fig. 1. The Human Affectome.

This framework is guided by the teleological principle that the collection of human affective phenomena in their entirety can only be accounted for by the nested and intertwined purposes: to ensure viability, to execute operations, to enact relevance, and to entertain abstraction. The bidirectional arrows are used to indicate that the human is enacting—in both being affected by relevant aspects of their actionable world, and affecting that world in order to make it relevant. We characterize affective phenomena as algorithms that address the relevance of the environment and monitor that adaptation. We distinguish between processes that reflect affective concerns and those that reflect affective features. The algorithms that address affective concerns indicate the relevance of a physical or mental object by suggesting actions regarding that object. We can organize one set of these processes in a hierarchy according to the distance from metabolic impact that the actions demanded by the concerns would have. The most immediate concerns (dark blue) are also the most concrete, yet least complex in actionability (i.e., physiological concerns, such as consuming food to alleviate hunger). On the other end of the continuum, more distal concerns (light blue) are increasingly abstract and complicated in terms of actionability, wherein more causal steps are required to achieve homeostatic impact (i.e., operational concerns, such as running away from a dog to alleviate fear, flickering lights for right-of-way on the road to express irritation, or researching more on a topic to address interest). In addition, the set of algorithms addressing affective concerns that do not fall along this continuum of distance from metabolic impact instead summarize across affective concerns. These global concerns include trajectory (green), the direction that the environment is heading toward across time; optimization (yellow), the best match between the environment and organism’s adaptive capacities across a given duration of time—the self-evaluations of aspects of the organism’s own adaptive capacity that are persistent across time. Finally, algorithms expressing affective features provide momentary information on the status of the adaptive process in relation to the comfort zone. These include valence and arousal. Created using Biorender.com.

3.1. Affective Concerns

These processes reflect concerns that address the relevance of physical or mental objects, including things, people, and situations, to the organism’s viability. The organism is proactively oriented toward the object, which is reflected in the felt implications of those objects. The object is, therefore, meaningful to the organism in virtue of the organism’s enactive orientation toward the object—the affective concern (Teroni, 2007; Frijda, 1986, 2017; Bedford, 1956; Kenny and Kenny, 2003; Pitcher, 1965; Leighton, 1985; de Sousa, 1990; Pham, 1998; King, 2009; Deonna et al., 2015; Deonna and Teroni, 2015; Varela et al., 1974; Gibson, 1977; Colombetti and Thompson, 2008; Di Paolo and Thompson, 2014; Shargel and Prinz, 2017; Slaby and Wüschner, 2014; Hufendiek, 2015; Hutto, 2012). As such, affective concerns can be clustered based on whether those operations address a potential breach in viability more or less directly, or as global summaries of those prospective operations. We can thus distinguish between different sets of mechanisms that address affective concerns:

Algorithms that reflect hierarchy of immediate to distal concerns organize gradations of enactive relevance, according to the distance from metabolic impact that the actions demanded would have.

Algorithms that reflect global concerns summarize across affective concerns in a comprehensive evaluation of adaptive performance across time, rather than being driven by a particular enactive relevance.

Many of these processes can be ongoing at the same time as well as rapidly changing moment to moment (Larsen and McGraw, 2014; Hoemann et al., 2017; Godfrey-Smith, 2020), collectively making up the human’s profile of affective experience in a certain period of time.

3.1.1. Hierarchy

The algorithmic mechanisms that address a hierarchy of immediate to distal concerns reflect predictive actionability toward an object, its relevance, along a gradient or scale of distance to metabolic impact. This gradient can correspond to the number of causal steps needed to address the affective concern, the timescale necessary to achieve homeostatic impact, or its concreteness to abstractness (Gilead et al., 2020; McEwen and Seeman, 1999; Pezzulo et al., 2015). In formal and computational terms, this can be construed as hierarchical depth (Pezzulo et al., 2021; Levin, 2019; Friston, 2020; Tschantz et al., 2022; Tomasello, 2022). Immediate concerns, such as physiological ones, are inferred at a lowest level (i.e., shortest timescale, fewest number of calculations, closest mappings to one-to-one between prediction and sensory data) in the hierarchy of actionability. Distal concerns, such as moral and other abstract concerns, are those at the highest (Scherer, 1982b). Below, we organize ranges of concerns along the continuum of actionable depth.

3.1.1.1. Physiological.

Algorithms reflecting physiological concerns can be addressed by the most immediate or concrete actions required to maintain organismic balance. This set of concerns requires actions that immediately affect the internal environment of one’s own body, therefore, dealing with the adaptive process in the most direct actionable manner. Physiological affective experience arises from interoceptive sensations, and typically reflects the integration of many interoceptive sources (Craig, 2002; Pace-Schott et al., 2019, this issue; Seth, 2013; Seth and Friston, 2016). In the English language, different feeling words along this dimension typically capture the intensity or degree of departure from the organism’s comfort zone. Physiological affective states may pertain to nourishment (e.g., hungry or thirsty; Ombrato and Phillips, 2021), energy levels (e.g., rejuvenated; Podilchak, 1991; Caldwell, 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2005), and internal bodily concerns (e.g., sick; Quadt et al., 2018; pain; Coninx and Stilwell, 2021; Kiverstein et al., 2022), among others. Algorithms addressing physiological concerns seem to be what we tend to refer to as sensation.

3.1.1.2. Operational.

Algorithms reflecting operational concerns are beyond immediate physiological needs as they demand the human organism to operate as a cohesive unit to interact with the environment in sophisticated sequences of actions (Frijda, 1986; LeDoux, 1989; Adolphs and Andler, 2018; Ekman and Cordaro, 2011; Lazarus, 2001; Roseman and Smith, 2001; Izard, 2007; Levenson, 2011; Panksepp and Watt, 2011; Poria et al., 2017; Scherer et al., 2010; Sander et al., 2003, 2005; Grandjean and Scherer, 2008; Scherer, 2009; Scherer and Moors, 2019; Clore and Ortony, 2000, 2013; Ortony et al., 1988; Russell, 2003; Barrett, 2017; Scarantino, 2014; Moors, 2022; Teroni, 2023). The meaning of an operational concern is such that addressing it won’t impact metabolism in a few short steps. In fact, the hypothetical distance from metabolism means that there are many ways to address operational concerns. Given that these concerns demand complex sets of actions over extended periods of time, there are many possibilities for securing those future circumstances for the organism to remain viable. The more sophisticated the course of action, the more abstraction required from the present moment. In addition, while the first-person perspective of human organisms is always maintained, they may cast that perspective to other beings, inanimate objects, or even abstract concepts such that they may consider concerns that are not presently theirs or are imagined. In this way, operational concerns can vary in degree of complexity or abstractness along the higher levels of the hierarchy of distance from metabolic impact, ranging from more immediate and concrete (e.g., anger at a broken printer) or more distal and abstract (e.g., inspired by artwork). More strikingly, however, is the diversity of operational concerns—as they are as numerous as possible operations are for addressing the multidimensional spectrum of relevance to humans. Nevertheless, we offer some examples to demonstrate how potential operations toward objects tend to be clustered:

Safety Concerns: suggest taking full advantage of an environment that enables and encourages exploration to expand one’s action repertoire or play to simulate operations under low stakes (e.g., joy, happiness, exhilaration) (Fredrickson, 2001, 2005; Fredrickson and Joiner, 2002; Lopez and Snyder, 2011; Csikszentmihalyi, 2014)

Danger Concerns: suggest avoiding potential threats that could cause harm such that viability is breached (e.g., fear, worry, dread) (Paterson and Neufeld, 1987; Levy and Schiller, 2021; LeDoux, 1996, LeDoux, 2022; Mobbs et al., 2019; Raber et al., 2019, this issue; Stefanova et al., 2020, this issue)

Obstruction Concerns: suggest pushing through or against an object that hinders, obstacles, or violates one’s adaptive capacity (e.g., frustration, annoyance, anger) (Britt and Janus, 1940; Kuppens et al., 2003; D’Mello and Graesser, 2012; Lench et al., 2016; Williams, 2017; Alia-Klein et al., 2020, this issue; Silva, 2021)

Loss Concerns: suggest recognizing that a resource is lost and seeking new resource to replace it (e.g., disappointment, sadness, grief) (Draper, 1999; Freed and Mann, 2007; Zeelenberg et al., 2000; Chua et al., 2009; Horwitz and Wakefield, 2007; Lench et al., 2016; Averill, 1968; Bonanno and Kaltman, 2001; Archer, 1999; Shear and Shair, 2005; Kübler-Ross and Kessler, 2005; Parkes, 2013; Neimeyer et al., 2014; Fuchs, 2018; Bonanno, 2019; Arias et al., 2020, this issue; Tsikandilakis et al., 2023)

Epistemic Concerns: suggest acquiring new knowledge to inform one’s action repertoire or solving a gap in planned operations (e.g., curiosity, intrigue, fascination) (Ortony et al., 1988; Silvia, 2008; Vogl et al., 2020; Dolcos, 2020, this issue)

Cooperation Concerns: suggest seeking out and sharing operations with other human beings for common goals (e.g., care, love, belonging, trust, empathy) (Eslinger et al., 2021, this issue; Heise, 1977; Isen, 1987; Leary, 2000; Schulkin, 2011; Forgas, 2001, 2012; van Hooff and Aureli, 1994; Atzil et al., 2018; Sznycer and Lukaszewski, 2019; Djerassi et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2022; Zoltowski et al., 2022; Migeot et al., 2023; Chemero, 2016; Fischer and Manstead, 2008, 2016; Lin et al., 2023)

Moral Concerns: suggest influencing potentially cooperative others via praise or punishment to adhere to the standards of operations for one’s comfort zone (e.g., pride, admiration, shame, moral disgust) (Haidt, 2003; Tangney et al., 2007; Gray and Wegner, 2011; Deonna et al., 2012)

Aesthetic Concerns: suggest slowing down to take in fit between the environment’s actionable features and one’s own action repertoire (e.g., awe, appreciation, beauty) (Brouwer et al., 2017; Desmet and Schifferstein, 2008; Hogan, 2011, 2017; Juslin, 2013; Kaneko et al., 2018; Marković 2012; Mastandrea et al., 2019; Menninghaus et al., 2019; Scherer and Coutinho, 2013; Silvia, 2005; Van de Cruys et al., 2022; Van Dyck et al., 2017a; Vessel et al., 2012)

It seems that what the field often refers to as emotion maps well onto algorithms reflecting operational concerns (Simon, 1967; Tooby and Cosmides, 1990, 2008; Clore and Palmer, 2009; Seth, 2013; Oatley and Johnson-Laird, 2014; Scarantino, 2014; Bach and Dayan, 2017; Atzil and Gendron, 2017; Hommel et al., 2017; Hommel, 2019; Al-Shawaf and Lewis, 2020; Al-Shawaf and Shackelford, 2024; Del Giudice, 2021; Suri and Gross, 2022; Quadt et al., 2022). This should be no surprise considering the term’s etymology, which is inherently tied to movement and action (Dixon, 2003, 2012).

3.1.2. Global

Given that the hierarchical affective concerns above are comprised of separate process occurring at different timepoints and for different durations, other concerns are required to make sense of them combined or more globally. Algorithms reflecting global concerns are not driven by any particular level of enactive relevance, but instead summarize across hierarchical concerns in comprehensive evaluation at a higher timescale. These global concerns are not about particular objects but are rather directed at summations of concerns about particular objects to inform an overall state (LeDoux, 2012). Although integration across hierarchical concerns can be analyzed in a number of different ways, there are two orders of global concerns that are the most obvious and have been studied well in the field: trajectory and optimization.

3.1.2.1. Trajectory.

Algorithms reflecting trajectory concerns summarize hierarchical concerns by reflecting their global direction with regard to the organism’s comfort zone (Schwarz and Clore, 1996; Eldar et al., 2016). These processes take into account whether the slope of adaptation is trending in a positive or negative direction. This means that affective experiences reflecting trajectory concerns often feel like they are not directed at anything in particular or they are directed at everything—as the specificity of relevance is lost in the summary of trajectory (Deonna and Teroni, 2012; Kind, 2013; Bollnow and Boelhauve, 2009; Frijda, 1993; Gendolla, 2000; Crane, 1998; Goldie, 2000; Seager, 1999; Solomon, 1993; de Sousa, 1990; Mendelovici, 2013; Tye, 1995; Arregui, 1996; Kriegel, 2019; Gendolla et al., 2005; Gendolla and Krüsken, 2001). Processes reflecting trajectory concerns usually last for longer periods of time than the short-lived hierarchical concerns. The affective construct that fits this characterization is mood. When one is in a good mood, one can describe its relevant environment as heading in a good direction (Morris and Schnurr, 1989; Price, 2006; Pessiglione et al., 2023).

3.1.2.2. Optimization.

Algorithms of optimization concerns summarize hierarchical concerns by reflecting their global performance at a high temporal scale, indicating the extent to which the human organism has achieved their best match between their adaptive capacities and the environment’s actionable features, across an extended duration of time (Schwarz and Strack, 1999; Strack et al., 1991; Diener and Ryan, 2009; Diener, 2009; Diener et al., 2009; LeDoux, 2012; Krueger and Schkade, 2008; Maddux, 2017; Oishi et al., 2020). These processes assess how the organism is faring overall in their quest for the maintenance of their comfort zone, suggesting wholesale changes to future operations. This usually means that the organism has been able to consistently occupy its comfort zone despite engaging in various operations (De Neve et al., 2013; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Eid, 2008; Brown et al., 2020). These algorithms seem to be what the field often refers to as wellbeing, including affective experiences of life satisfaction, authenticity, fulfilment, and self-actualization (Alexander et al., 2021, this issue; Arias et al., 2020, this issue; Schwarz and Strack, 1999; Diener et al., 2013; Krueger and Schkade, 2008; Maddux, 2017; Oishi et al., 2020).

3.2. Affective Features

These processes reflect the momentary information on the adaptive process itself. Algorithms reflecting affective features monitor several standards inherent to the adaptive process:

Algorithms that reflect valence provide information on how well or poorly the human organism is doing with respect to the comfort zone.

Algorithms that reflect arousal provide information on how much resources should be put to various systems.

Unlike affective concerns, which highlight the object of interest as actionably relevant during an affective experience, affective features are reflected in the qualitative aspects of the experience itself. In addition, each can have multiple dimensions as opposed to being constrained to single scalars with two extremes.

3.2.1. Valence

Across affective concerns, algorithms reflecting valence arise in the hedonic quality of affective experience, often described as pleasure and displeasure, marking how adaptation is faring with respect to the concern at the heart of the affective phenomenon (Becker et al., 2019, this issue). This characteristic of affective phenomena can be construed to have multiple dimensions, such as when both positive and negative valence seem to be present (e.g., nostalgia) (Colombetti, 2005; Keltner and Lerner, 2010; Viinikainen et al., 2010; Batcho, 2013; Vazard, 2022). There are more recent formal accounts of the mechanism of valence—some from the perspective of the environment being good, while others of the view that it is the evaluation of the environment being good (e.g., Rutledge et al., 2014; Joffily and Coricelli, 2013; Hesp et al., 2021)—but it is largely agreed upon that valence is an intrinsic characteristic of affective phenomena, momentarily describing adaptivity (Charland, 2005; Berridge and Kringelbach, 2008; Van de Cruys, 2017; Trofimova, 2018).

3.2.2. Arousal

Across affective concerns, algorithms reflecting arousal assess the quality of intensity in affective experience, often described as low to high, marking the extent of excitation, activation, or mobilization of processes serving a particular concern (Duffy, 1957; Anderson and Adolphs, 2014; Clore et al., 2021). Given that many processes can be implicated in an affective concern, there are many dimensions of arousal (e.g., wakefulness, emotional arousal, sexual arousal, physical activity, attention) (Duffy, 1957; Zuckerman, 1971; Pribram and McGuinness, 1975; Thayer, 1978; Robbins and Everitt, 1995; Robbins, 1997; Cahill and McGaugh, 1998; Jones, 2003; Eysenck, 2012; Satpute et al., 2019; Dolcos et al., 2020, this issue). Although intermediate arousal across time can be an indication of effective adaptivity, these systems can have varying degrees of arousal at any one time (e.g., sexual arousal during fatigue) (Neiss, 1988; Griffiths, 2013).

Taken together, given the rapid change of a dynamic human neurobiological system, these algorithms rarely, if ever, reflect a neutral valence or arousal state, even in periods of high optimization. These two features are usually related but remain orthogonal due to operations that can involve opposing positions on their various spectra (Kuppens et al., 2013, 2017; Yik et al., 2023). These features are ever-present, marking every affective experience and evaluating every hierarchical affective concern. In addition, these are the sources of information used by algorithms of global concerns, responsible for summarizing across the dynamic momentary ones. Finally, these affective features are often what is referred to in the field as ‘affect’, perhaps because they are most inherently tied to the organism’s comfort zone (Russell, 2003; Posner et al., 2005; Barrett and Satpute, 2019). We, however, distinguish them as the affective gauges, while concerns are the focus of affective phenomena.

The feature of motivation has also been suggested as part of affect, often citing dimensions of approach and avoidance (Lang and Bradley, 2008). However, within this framework, given the central role of our teleological principle, it seems that affective phenomena can be more cohesively organized if motivation is taken as an inherent aspect (Klinger, 1975; Nelkin, 1989; Rosenthal, 1991; Di Paolo, 2005; Colombetti, 2014; Cromwell et al., 2020, this issue). Given our teleological principle, an organism has algorithms reflecting affective concerns that address actionability, and thus relevance, of the environment through this enaction. Therefore, affective phenomena inherently involve motivation in that actionability is at the heart of relevance. As such, motivation folds into the inherent enacting of relevance necessary for this framework’s teleological foundation, whereas valence and arousal can be found as distinct capacities in the human organism’s adaptive purpose.

4. Conclusions: How can we study human affective phenomena?

This capstone paper builds a teleological principle to guide the construction of an integrative framework for human affective phenomena, a set of assumptions about what they are and how they work. To account for the entire collection of affective phenomena in humans, we can consider them as arising to entertain abstraction, when enacting relevance, by executing operations, to ensure viability. Based on this principle, affective phenomena can be considered processes that adjust based on the human’s comfort zone (affective concerns) and monitor their adaptive process (affective features). Affective concerns, include a hierarchy of relevance ranging from courses of action with more immediate metabolic impact to those with more distal impact. They also include global concerns that summarize momentary affective concerns on the hierarchy at a higher timescale, such as tracking their trajectory and optimization with respect to the comfort zone. These global concerns use the momentary information that characterize all affective concerns provided by affective features—algorithms that monitor the adaptive process. These include multidimensional metrics of valence, how well or poorly the human organism performs in light of their comfort zone, and arousal, how much resource should be mobilized per necessary system for action. All affective phenomena are experientially and mechanistically organized from the perspective of the human organism, where affective concerns are the focus of the affective experiences and affective features mark them all as qualities of the experiences. This cohesive framework is offered to be used as a synthesized set of metaphysical and mechanistic assumptions organized around a teleological principle that is based on a comprehensive sampling of existing theoretical perspectives on affective phenomena (Table 2).

It is important to note that this is not intended as a semantic taxonomy of affective phenomena and their definitions, but rather as an ontology for how human affective phenomena might follow from a common principle and be related to each other (Fodor, 1998; Egan, 2017, 2020). To truly fold the richness of valid scholarly interests into an encyclopedia of semantic constructs in the field would require a full research program’s worth of time and work, spanning years, or even decades. This endeavor is also not meant to be another falsifiable theory for generating testable hypotheses. What we offer here instead is a principled multidisciplinary theoretical launchpad for many threads of inquiry and a scaffold for hosting specific theories and hypotheses differentiated from or situated among the tenets of this framework (Popper, 1963; Kuhn, 2012; Holton, 1975; Lakatos, 2014, 1978; Laudan, 1978; Godfrey-Smith, 2009; Ormerod, 2009; Jabareen, 2009; Notturno and Popper, 2014).

We hope this framework provides a template for an organized research agenda for the affective sciences moving forward, following similar endeavors in neighboring fields: the Human Genome, organizing the complete set of human genetic information (Schuler et al., 1996), and the Human Connectome, organizing all networks of connectivity in the human brain (Sporns et al., 2005). By the same token, we dub this framework the Human Affectome, where the suffix ‘-ome’ means “all the constituents of, considered collectively or in total” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2023), so that it can be used by the field to organize the collection of algorithms across human affective phenomena. We aim for this framework to encourage the interdisciplinary field of the affective sciences to identify concrete algorithms in order to test specific theories and hypotheses about affective phenomena. This will be an exercise in characterizing and organizing human affective phenomena based on the teleological principle, ultimately, applying this framework to build out the Human Affectome in a principled and comprehensive manner.

For each member of the field, the initial approach we advocate is to triangulate your explanatory goals among these assumptions in order to compare them to others in the field on the basis of the teleological principle described here. Paired with the perspectives incorporated into the teleological synthesis (Table 2), we offer an inverse, preliminary mapping of examples of the field’s existing theoretical accounts onto this framework (Table 3). We also suggest ways the existing theoretical constructs in the field can be situated within this framework (Table 4). We hope these resources can help efforts to regenerate existing theories and hypotheses as well as put forth new ones in terms of the teleologically-principled algorithms here. In this way, different disciplines, subdisciplines, and individual researchers can understand their differing context-dependent interests, disclose their assumptions, and work toward integrating their frameworks in a non-adversarial manner (Dijkstra, 1965; Mitchell, 2003, 2012; Bechtel, 2009; Tabery, 2014; Tabery et al., 2014).

Table 3. Situating Existing Theoretical Accounts within the Human Affectome.

This table summarizes explanatory goals of existing theoretical accounts of affective phenomena with their chosen methodologies and situates them within the algorithmic organization of the Human Affectome. For each entry of theoretical account in the table below, references to relevant theoretical accounts are bolded and references to the Human Affectome are italicized. References included here supplement citations in the main body of the text.

| Theoretical Accounts | Explanatory Goal | Methodology | Situated within The Human Affectome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective computing | matching, recognizing, or simulating affective phenomena often using multidimensional data (Picard, 2000; Gratch and Marsella, 2004; Poria et al., 2017) | computational modeling; machine learning | Can be used to articulate affective algorithms. To entertain abstraction, Operational concerns. |

| Appraisal | 1. the commonality of relations between evaluations and emotions across populations (discrete appraisal theories; Lazarus, 2001; Roseman and Smith, 2001) | subjective report (fixed options); behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; affective computing | The actionable orientation with which the human organism evaluates an object as relevant. Affective Concerns. |

| 2. the variability in relations between emotions and combinations of evaluations across populations (dimensional appraisal theories; Grandjean and Scherer, 2008; Scherer, 2009; Scherer and Moors, 2019; Lerner and Keltner, 2000, 2001) | subjective report (dimensional responses); behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; affective computing | ||

| 3. evaluations as distinguishing between what constitutes different emotion types, rather than causing them (OCC model; Ortony et al., 1988) | computational modeling and formalism | ||

| Autopoiesis | See enactive: autopoietic. | ||

| Basic emotion | the commonality of physiological, neural, and behavioral indicators of types of emotion across populations | subjective report (fixed options); behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging | Emotions can be grouped by their cluster of operational concerns but are not necessarily biologically determined. Operational concerns. |

| Bayesian inference | 1. predictive inference of explanation for sensory data (Bayesian brain hypothesis or predictive coding) | behavioral paradigms; computational modeling and formalism; neuroimaging | Objects are evaluated by their meaning. Affective Concerns. |

| 1a. predictive inference of explanation for sensory data based on principle of minimizing free energy by considering action (active inference) | Objects are evaluated by their actionable meaning. Affective Concerns. | ||

| Cognitive science | interdisciplinary field studying the mind | behavioral paradigms; computational modeling and formalism; neuroimaging | Entertaining abstraction allows us to engage in cognitive science, but we can also question whether cognition and affect are indeed separate. Conclusions. |

| Computational psychiatry | the individual computational mechanisms at play in different people with psychiatric disorders | behavioral paradigms; computational modeling and formalism; neuroimaging | Mechanisms in psychiatric disorders can be construed as algorithms of adaptivity gone awry. See representation: misrepresentation. To entertain abstraction. |

| Connectionism | the distributed activity across nodes of a neural network (see attractor states in Table 4 and dynamical systems) | computational modeling and formalism | An organism’s processes unfold across many nodes. To ensure viability. |

| Constructionist | 1. the presence of felt bodily changes during emotional experience (somatic marker hypothesis) (Damasio, 1996) | subjective report; behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging | Emotions being felt reflections of algorithms addressing operational concerns, which can be inferences of lower-level affective concerns. Operational concerns. |

| 2. the dimensional commonalities across all emotional experiences (core affect) (Russell, 2003; Russell et al., 1989; Posner et al., 2005; Kuppens et al., 2013) | subjective report (dimensional responses); behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging | ||

| 3. the variability in subjective reports of emotional experience (theory of constructed emotion) (Barrett, 2017) | subjective report (free labeling); behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging | ||

| Dynamical systems | the dynamics of distributed activity across time (see attractor states in Table 4) | computational modeling and formalism | An organism’s processes unfold across time as a complex system. To ensure viability. |

| Embedded | interactions between organism and environment shape organism’s capacities (see situated) | conceptual analysis | The human organism must interact with the environment to enact its relevance. To enact relevance. |

| Embodied | mental processes involve whole body, not just brain and nervous system | subjective report; behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging; conceptual analysis | All processes in an organism are contributing to enacting relevance. To enact relevance. |

| Enactive | 1. everything an organism does, including cognition, is active—specifically, as interactions with its environment | computational modeling and formalism; conceptual analysis conceptual analysis | The Human Affectome is guided, in part, by the Teleological Principle that human organisms enact relevance. All affective phenomena are enactive. (Emotions, as references to operational concerns, can therefore also be considered enactive.) |

| 1a. to be an organism is to self-generate and self-distinguish (autopoietic) | To ensure viability. | ||

| 1b. the organism both makes sense of the world and makes the world make sense (sense-making) | To enact relevance. | ||

| 2. how perception and action can guide each other (sensorimotor) | subjective report; behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging;conceptual analysis | To enact relevance. | |

| 3. enaction allows us to do away with representation (radical) | conceptual analysis | The Human Affectome does not assume a strong claim on representation, but representations can be used to describe algorithms. To enact relevance, To entertain abstraction. | |

| Evolutionary | affective phenomena can be explained based on aspects that developed via natural selection (Izard, 1978; Nesse, 1990; Porges, 1997; Panksepp, 1998; LeDoux, 2012; Al-Shawaf et al., 2016). | behavioral paradigms; neuroimaging; conceptual analysis | The Human Affectome does not take up an explicit evolutionary perspective, despite the assumption that part of the purpose of affective phenomena is to ensure viability. All else, such as metabolism, reproduction, and evolution, arise from necessarily being a unity in the first place (Varela et al., 1974; Maturana, 1980) |

| Extended | the mind extends further than the body to objects used in a relevantly similar and reliable way (Clark and Chalmers, 1998) | conceptual analysis | The Human Affectome does not assume an extended mind, but merely highlights the interactions between human organism and environment. To enact relevance. |

| Goal-directed theories | integration of dimensional appraisal and constructionist theories of emotion (Moors, 2017a; 2017b) | conceptual analysis | Emotion types grounded by clusters of goal-orientedness or action tendency. Operational concerns. See goal in Table 4. |

| Homeostasis | how organism remains within viable states despite environmental change | behavioral paradigms; physiological measures; neuroimaging; conceptual analysis | This is entailed by autopoiesis. To ensure viability. |

| Human Affectome | what affective phenomena are and how they work based on why they exist | conceptual analysis | Entire framework of the Human Affectome. |

| Intentionality | the aspect of a mental state being about something | conceptual analysis; phenomenological analysis | Objects are relevant to an organism based on its actionable orientation toward them; allows distinction between affective types based on clusters of affective concerns. Affective Concerns. |

| projecting intentionality onto something whose behavior seems to have it (intentional stance) | We can use the intentional stance to articulate processes, whether the source has intentionality or not. To entertain abstraction. | ||