Abstract

Introduction

Spinal cord stimulation is a widespread treatment of chronic neuropathic pain from different conditions. Several novel and improving technologies have been recently developed to increase the effect of neuromodulation in patients refractory to pharmacological therapy.

Research question

To explore spinal cord stimulation’s mechanisms of action, indications, and management.

Material and methods

The paper initially explores the mechanism of action of this procedure based on the generation of an electric field between electrodes placed on the posterior dural surface of the spinal cord probably interfering with the transmission of pain stimuli to the brain. Subsequently, the most consolidated criteria for selecting patients for surgery, which constitute a major issue of debate, were defined. Thereafter, the fundamental patterns of stimulation were summarized by exploring the advantages and side effects. Lastly, the most common side effects and the related management were discussed.

Results

Proper selection of the patient is of paramount importance to achieve the best results from this specific neuromodulation treatment. Regarding the different types of stimulation patterns, no definite evidence-based guidelines exist on the most appropriate approach in relation to the specific type of neuropathic pain. Both burst stimulation and high-frequency stimulation are innovative techniques that reduce the risk of paresthesias compared with conventional stimulation.

Discussion and conclusion

Novel protocols of stimulation (burst stimulation and high frequency stimulation) may improve the trade-off between therapeutic benefits and potential side effects. Likewise, decreasing the rates of hardware-related complications will be also useful to increase the application of neuromodulation in clinical settings.

Keywords: Spinal cord stimulation, Neuropathic pain, Complex regional pain syndrome, Failed back surgery syndrome

Highlights

-

•

Spinal cord stimulation (SCI) is a widespread treatment of chronic neuropathic pain.

-

•

We provide clinicians with a concise guide on SCI’s mechanisms of action, indications, and management.

-

•

The most consolidated criteria for selecting patients for surgery are defined.

-

•

Fundamental patterns of stimulation are summarized by advantages and side effects.

Abbreviations

- CRPS

complex regional pain syndrome

- CT

computed tomography

- FBSS

failed back surgery syndrome

- IASP

International Association for the Study of Pain

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- SEPs

somatosensory evoked potentials

- SCS

spinal cord stimulation

- TCA

tricyclic antidepressants

- WDR

wide dynamic range

1. Introduction

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a widespread treatment for chronic neuropathic pain originating from different causes, particularly failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). This technique was inspired by the gate control theory formulated by Melzack and Wall in 1965, claiming that the “control of pain may be achieved by selectively activating the large, rapidly conducting fibers” in the spinal cord (Melzack and Wall, 1965).

Thus, the nociceptive signal would be inhibited by the antidromic activation of collateral, large, myelinated Aβ fibers in the dorsal columns. A few years later, the early clinical application of the SCS occurred, but initially it was expected to influence only the stimulated spinal segmental level (Shealy et al., 1967). Thereafter, an increasing number of patients with chronic neuropathic pain refractory to pharmacological therapy received this treatment. Latest theories argue that SCS acts on the supra-spinal pathways of pain control (Barchini et al., 2012). Recent animal and neuroimaging data corroborate this hypothesis, showing that tonic stimulation of the spinal cord, by modulating the ascending lateral pathways of pain, modifies the metabolic activity in the cingulate gyrus, thalamic sensory lateral nuclei, prefrontal cortex, and postcentral gyrus (El-Khoury et al., 2002; Rasche et al., 2005). In addition, SCS appears to abolish the over-excitability of wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons in dorsal horns by increasing GABA release of local interneurons, resulting in decreased pain transmission along the lateral pathways (Zhang et al., 2014). Although there is increasing evidence on the mechanisms of action of SCS, the reasons for its efficacy in chronic neuropathic pain are not fully clarified. Several novels and improving technologies have been developed to increase the effect of SCS in treating chronic pain (Deer et al., 2014). Conventional tonic stimulation has been implemented by the use of very high-frequency stimulation and, more recently, by the application of burst stimulation (Kapural et al., 2016a; De Ridder et al., 2013). Furthermore, the development of new electrodes with multiple leads on a wire or paddle support, spreading the electric field over a greater surface of the spinal cord, has allowed targeting larger areas of pain as the lumbar region, both lower limbs and even the torso. A novel modality of epidural spinal stimulation has been developed to directly stimulate the dorsal ganglia thus focusing the action of the electric field on a specific dermatome (Deer et al., 2017a). Despite several stimulation patterns and possible theoretical explanations of SCS, the only reliable evidence is that the electric field generated between electrodes on the posterior dural surface of the spinal cord interferes with the transmission of painful stimuli to the brain by changing the electrical potentials through the spinal nerve cell membranes in the dorsal columns thus stimulating action potentials according to the specific characteristics of each axon (size, myelination, electrical threshold) (Linderoth and Foreman, 2017; Oakley and Prager, 2002; Meyerson and Linderoth, 2000; Barolat, 1998).

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using the following keywords and their combinations: “Spinal Cord Stimulation”, “SCS”, “Chronic Neuropathic Pain”, “Pain Management”, “Spinal Cord Injury”, “SCI”, “Motor Rehabilitation”. The search encompassed several electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, to ensure comprehensive coverage of the literature. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, while articles not focusing on SCS in chronic neuropathic pain or SCI motor rehabilitation, review articles, case reports, and non-English language articles were excluded. The inclusion of uncertain cases was redefined through a consensus discussion. All included studies were reviewed for pertinent patient data.

3. Chronic neuropathic pain

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain should be considered of neurological origin when an injury to the somatosensory nervous system occurs (Torrance et al., 2006). Different pain categories can be recognized according to the etiology, including nociceptive (from tissue damage), neuropathic (from nerve injury), or nociplastic (from maladaptive changes involving nociceptive processing) pain, despite a substantial overlap among mechanisms being observed (Cohen et al., 2021). The incidence of chronic neuropathic pain is higher in women than in men (8% versus 5.7%) and in middle-aged patients (8.9%) (Colloca et al., 2017). Chronic neuropathic pain usually involves the lower back and lower limbs, neck, and upper limbs, manifesting with burning sensations, numbness, and tingling (Bouhassira et al., 2008). Indeed, changes in the sensory pathways lead over time to a hyperexcitable state from the periphery to the brain and might contribute to the neuropathic pain state becoming chronic (Colloca et al., 2017). Enhanced excitability of spinal neurons produces increased responses to many sensory modalities, accompanied by dysfunctional inhibitory interneuron and descending modulatory control system modulation (Colloca et al., 2017). As a consequence, altered and abnormal sensory messages are conveyed to the brain (Colloca et al., 2017). Moreover, aberrant projections to the thalamus and cortex and parallel pathways to the limbic areas seem to be involved in increased pain sensations and anxiety, depression and sleep problems development (Colloca et al., 2017). Several studies also documented the importance of the brainstem excitatory pathways in the maintenance of the pain state (Colloca et al., 2017).

The differential diagnosis between chronic neuropathic pain and other types of pain is crucial for the proper setting of the therapeutic process and may often result challenging. Specifically, the recognition of underlying psychiatric disorders, including major depression, psychosis, and drug abuse, is essential, as these are likely to reduce the effectiveness of therapeutic procedures such as SCS. To this end, various useful tools for the correct assessment and diagnosis of pain have been developed and validated. Among them, the Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire, ID Pain, and PAIN DETECT are the most relevant for clinical purposes (Bouhassira et al., 2008; Bennett et al., 2007). Despite the development of several painkiller molecules, results in terms of efficacy in improving neuropathic pain are still poor. Moreover, these drugs are hampered by the common presence of side effects that prevent them from long-term use.

4. Drug therapy for chronic neuropathic pain

Drug therapy for chronic neuropathic pain includes various effective treatments, such as anticonvulsants (especially alpha-2-delta agents like pregabalin and gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and spinal cord injury), and antidepressants like tricyclics (TCAs) and serotonin norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which are particularly useful for painful diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of drugs with effect on chronic neuropathic pain with detailed field of application, mechanisms of action and side effects.

| Drug therapy for chronic neuropathic pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug class | Field of application | Mechanisms of action | Side effects |

| Anticonvulsants | |||

| Pregabalin and Gabapentin | Chronic neuropathic pain Painful diabetic neuropathy Post-herpetic neuralgia Spinal cord injury |

Alpha-2-delta binding proteins. Modulate voltage-gated calcium channels and neurotransmitter release |

Common: Dizziness, sedation, headache Rare: Edema and nausea |

| Carbamazepine | Trigeminal neuralgia Painful diabetic neuropathy Post-herpetic neuralgia |

Antagonistic action for sodium channels and inhibiting ectopic discharges | Common: Dizziness, unsteadiness and somnolence |

| Lamotrigine | Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy Central post-stroke pain HIV-associated neuropathy |

Antagonistic action for sodium channels | Common: Cutaneous rash |

| Sodium valproate | Trigeminal neuralgia Painful diabetic neuropathy |

Inhibition of GABA transaminase and increases levels of GABA | Common: Nausea, sedation, drowsiness, vertigo and abnormal liver function |

| Antidepressants | |||

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) Amitriptyline and nortriptyline |

Painful diabetic neuropathy Post-herpetic neuralgia |

Inhibition of norepinephrine re-uptake at the spinal dorsal synapse. Secondary effect on sodium channels |

Common: Anticholinergic effects (constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, dry mouth, postural hypotension), sedation, and conduction abnormalities |

| Serotonin norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) Duloxetine and Venlafaxine |

Painful diabetic neuropathy Chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions |

Inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake in the pre-synaptic cleft of the neuron | Common: Nausea, constipation, diarrhea, increased sweating, somnolence, dizziness, and dry mouth Rare: Serotonin syndrome and hepatic dysfunction |

| Local Anesthetics | |||

| Lidocaine | Post-herpetic neuralgia Post-traumatic painful neuropathies Painful polyneuropathies |

Antagonistic action for sodium channels and reducing spontaneous ectopic nerve discharges | Common: Local skin reactions |

| Capsaicin | Painful diabetic neuropathy Post-herpetic neuralgia HIV-associated neuropathy |

Agonist of TRPV1 receptors expressed in afferent neuronal C and Aδ fibers with sensory axon desensitization and skin denervation | Common: Local skin reactions, transient hypertension Rare: Nasopharyngeal or respiratory irritation, sneezing and tearing due to inhalation |

| Opioids | |||

| Tramadol Codeine Morphine Oxycodone Fentanyl |

Episodic exacerbations of severe neuropathic pain Painful diabetic neuropathy Post-herpetic neuralgia |

Central opioid agonist of the mu receptor Inhibitor of norepinephrine and serotonin re-uptake |

Common: Nausea, constipation, dizziness, somnolence, and orthostatic hypotension Rare: Overdose, dependence, and addiction |

| Cannabinoids | |||

| Neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis Neuropathic pain with allodynia |

Acting on CB1/CB2 receptors with inhibition of the release of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides from presynaptic nerve endings, modulation of postsynaptic neuron excitability, activation of descending inhibitory pain pathways and reduction of neural inflammation | Common: Nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, gastrointestinal effects, oral discomfort, and sedation | |

Anticonvulsants, and in particular the alpha-2-delta binding agents pregabalin and gabapentin, are considered as a first-line treatment in chronic neuropathic pain, especially in painful diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and spinal cord injury (Freynhagen et al., 2005, 2006; Cardenas et al., 2013; Gorson et al., 1999; Levendoglu et al., 2004; Zilliox, 2017). TCAs and SNRIs, preferred for their safer profiles, act by inhibiting norepinephrine re-uptake and affecting sodium channels, with side effects like dry mouth and sedation (Kochar et al., 2004; Gillman, 2007; Max et al., 1987; Quilici et al., 2009). Local anesthetics, such as lidocaine, are beneficial for peripheral neuropathic pain, with minimal side effects, the most common being local skin reactions (Saarto and Wiffen, 2007).

Opioids, though effective, are considered second-line due to risks of dependence and are used for severe or episodic pain. Another topical medication is capsaicin, a hot chili pepper extract, effective in several peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes (Finnerup et al., 2010). Cannabinoids serve as a third-line option for specific neuropathic pains. The response to these treatments varies, and their effectiveness is often independent of the underlying neuropathic disorder, highlighting the necessity for alternative approaches or combination therapies, though evidence for specific combinations remains limited (O’Neill et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2003; Raja et al., 2002).

In clinical practice, pharmaceutical combinations are commonly adopted with the aim of increasing efficacy and reducing side effects, but there is not enough evidence to recommend a specific combination (Meng et al., 2017; Tesfaye et al., 2013). Moreover, the analgesic response to pharmacological therapy is often inadequate, incomplete, and burdened by important limitations and side effects (Levendoglu et al., 2004). Consequently, there is a need for alternative therapeutic approaches.

5. Indications for spinal cord stimulation

Each year, a continuously increasing number of patients with chronic neuropathic pain worldwide are satisfactorily treated with SCS. Their diagnoses range from peripheral nerve injury to post-herpetic neuralgia and central spinal cord pain (Finnerup et al., 2015). The major indication for SCS is the so-called FBSS in which, after a single or multiple spinal surgery, patients do not manifest satisfactory pain relief. FBSS refers to a group of conditions with recurring back pain and/or sciatica after one or more spine surgeries (Sebaaly et al., 2018). Another indication is the CRPS, a poorly understood chronic pain condition with multifactorial etiology, involving sensory, motor, and autonomic symptoms primarily affecting one extremity (Halicka et al., 2020). Conversely, post-herpetic neuralgia seems to respond poorly to SCS, whereas peripheral nerve field stimulation and dorsal ganglion stimulation appeared to be significantly effective (Nagel et al., 2014).

Two surgical techniques may be used to implant SCS: 1) the traditional open placement method which is obtained by performing a laminectomy or laminotomy by means of a posterior access to the spinal cord; 2) the minimally-invasive percutaneous method. Although the former may lead to an improved pain control and reduced rates of hardware migrations, a recent metanalysis demonstrated that the latter was associated with overall decreased rates of reoperations (including explantations) due to both hardware and medical complications (Bendersky and Yampolsky, 2014; Blackburn et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, despite its proven effectiveness in controlling chronic neuropathic pain, SCS is still often neglected by general practitioners, neurologists, spinal neurosurgeons, and anesthesiologists leading to delayed appropriate treatment and prolongation of patient discomfort.

6. Failed back surgery syndrome

The FBSS is a well-documented complication of lumbar spine surgery characterized by chronic back or leg pain affecting from 10% to 40% of treated patients, with a substantial impact on their daily functionality, sleep benefit, and overall well-being (Nagel et al., 2014; Aarabi, 2020; Inoue et al., 2017). This disorder represents the main indication for SCS (Miller et al., 2005). Most patients reporting FBSS underwent surgery for lumbar disk herniation or spinal stenosis, with an increasing incidence with age and in females (Miller et al., 2005; Shmagel et al., 2016). Nevertheless, this condition is frequently not recognized by surgeons who repeatedly perform surgery on patients, instead of addressing them to neuromodulation. In fact, SCS appeared to be beneficial in 75% of FBSS cases with a mean pain relief of 50% (Lin et al., 2019; Thomson, 2013; Taylor et al., 2014a). In addition, a randomized controlled trial proved that SCS is more effective than conservative medical therapy in treating chronic pain from FBSS (Colombo et al., 2015; North et al., 2005).

The pain pattern may be referred to as either axial (lumbar region) or radicular (down the leg in the distribution of a nerve root) sites, often associated with paraspinal and hamstring muscle spasm, sacroiliac joint symptoms, exacerbated by standing and bending (Onesti, 2004). Patients with FBSS are more likely to present concomitant emotional or psychosocial disorders, accompanied by a history of abandonment, physical abuse, and reduced interpersonal relationships (Carragee et al., 2005; Clancy et al., 2017). Other predictive factors, including obesity and smoking, have been identified (Slipman et al., 2002). Indeed, the choice of an inappropriate surgical approach as well as operating at the wrong vertebral level are associated with a greater risk of FBSS (Chan and Peng, 2011; Daniell and Osti, 2018).

The usual anatomic locations from where the pain is believed to originate are the nerve, the disk, the facet joint, and the paraspinal muscles. Indeed, persistent nerve root compression or progression of disk disease or spinal stenosis are common sources of persistent leg pain following laminectomy (Fritsch et al., 1996). Epidural fibrosis, increased spinal instability due to discectomy or laminectomy, and redistribution of load to adjacent disc tissue also contribute to pain development (Chan and Peng, 2011). Chronic nerve root compression and irritation after intraoperative manipulation or injury may determine the development of the so-called “battered nerve root syndrome”. In these circumstances, the neurophysiological assessment of peripheral neuropathy or lumbosacral plexopathy can be performed in selected cases. In the clinical examination, the red flag signs are saddle anesthesia or bowel/bladder incontinence for cauda equina syndrome; fever, chills, or weight loss for infectious disease (Chan and Peng, 2011; Daniell and Osti, 2018; Orhurhu et al., 2022).

Complementary radiographs of the lumbar spine, including flexion and extension views, can detect vertebral and sacroiliac defects and/or misalignment and spondylolisthesis (Kizilkilic et al., 2007). Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast sequences can contribute to evaluating the presence of epidural fibrosis and scar formation from previous operations, as well as nerve root enhancement may reveal chronic injury and inflammation (Onesti, 2004). In fact, Computed Tomography (CT) Myelography offers the most accurate representation of nerve root involvement, especially in patients with ferromagnetic implants (Onesti, 2004).

The surgical treatment of FBSS is still debated, due to the possible exacerbation of the clinical symptoms. However, rehabilitation in the acute phases is crucial to provide patients with independence with activities of daily living and to release muscle spasms, despite the benefit being limited in chronic symptomatology (Onesti, 2004).

7. Complex regional pain syndrome

The CRPS is a chronic painful condition generally affecting the extremities after a traumatic event (fractures, orthopedic surgery) or immobilization (stroke). It mainly involves women (mean age of 46 years) and in most cases the upper extremities (Kumar et al., 2007, 2008). The concept of CRPS was coined in 1994 by the IASP with the distinction of type I, previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and type II, originally defined as “causalgia”, based on the demonstration that the nervous system was implicated in its pathophysiology. The diagnosis of CRPS is mostly clinical using the IASP criteria (1994) or the more recent and detailed Budapest criteria (2003) (Sandroni et al., 2003). In addition to intense, prolonged, and often constant pain exacerbated by movements, there are alterations in sensitivity (hyperesthesia, allodynia), autonomic system (vasomotor: temperature asymmetry, skin color changes; sudomotor: sweating changes), and motility (decreased range of motion, weakness, tremor, dystonia). During the acute phase (warm), the classic signs of inflammation, calor, dolor, rubor, and tumor are initially detected. After about 6 months, the chronic phase (cold) occurs with trophic changes affecting the skin, nails, hair, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, and bone (local osteoporosis) (Marinus et al., 2011). The pathophysiology is multifactorial and involves different pathways: 1) classic inflammation in response to tissue damage; 2) neurogenic inflammation with stimulation of nociceptive C-fibers and release of pro-inflammatory neuropeptides; 3) impairment of the autonomic nervous system; 4) maladaptive neuroplasticity of the motor and somatosensory cortex in the central nervous system (Harden et al., 2007; Veldman et al., 1993; Kortekaas et al., 2016). Physical therapy, especially mirror therapy, and occupational therapy are the most relevant treatments and provide benefits mainly in the early stages to avoid kinesiophobia (Littlejohn, 2015). Concerning pharmacological therapy, a meta-analysis concluded that the optimal treatments are bisphosphonates followed by glucocorticoids (Schwenkreis et al., 2009). It is postulated that bisphosphonates act by the regulation of inflammatory mediators and the inhibition of proliferation and migration of bone marrow cells. Glucocorticoids seem to have a stronger effect in the early inflammatory phase (Perez et al., 2010). Vasoactive mediators such as phenoxybenzamine, a sympathetic blocker, and clonidine, a 2-adrenergic agonist, have shown a reduction in pain and hyperalgesia at an early stage (Wertli et al., 2014; Barbalinardo et al., 2016). The anticonvulsant Gabapentin, a first-line treatment in chronic neuropathic pain, has proven its efficacy in pain control even in patients with CRPS (Ghostine et al., 1984). The anesthetic agent, ketamine, has shown an analgesic effect in CRPS. This drug exhibits potent non-competitive NMDA receptor-blocking ability. It has been postulated that the activation of the NMDA receptors may be responsible for the development of central sensitization as well as spontaneous pain and hyperalgesia (Davis et al., 1991). Vitamin C has also demonstrated to reduce the risk of CRPS onset after a fracture, probably acting as a free radical scavenger (van de Vusse et al., 2004). Based on evidence that in 40% of patients surface-binding autoantibodies against an autonomic nervous system auto-antigen are involved, a randomized clinical trial has shown benefit with intravenous immunoglobulin administration (Dahan et al., 2011). Since drugs are often not adequate in improving CRPS symptoms, several invasive procedures have been employed, such as sympathetic blockade, surgical sympathectomy, and SCS (Aïm et al., 2017). It has been found that most patients treated with SCS have shown an improvement in symptoms and quality of life. Neuromodulation is most effective if performed as soon as possible, also reducing the risk of chronic polypharmacological treatments (Goebel et al., 2010; Misidou and Papagoras, 2019). Moreover, conventional SCS demonstrated to be more effective than physical therapy in reducing both pain and clinical signs of involvement of the sympathetic nervous system (Kemler et al., 2008).

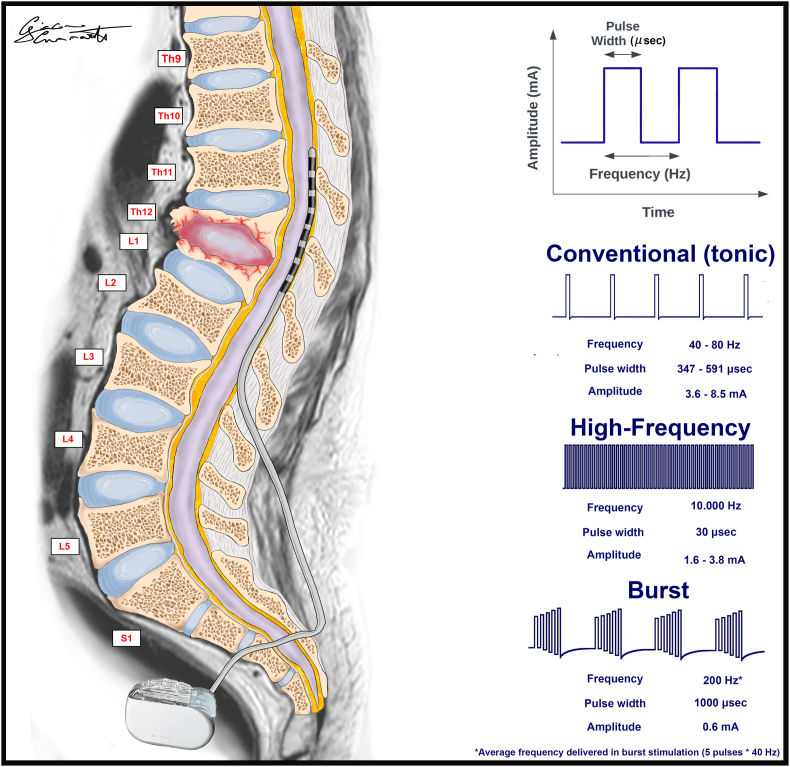

8. Conventional “tonic” stimulation

Historically, lesional procedures on dorsal root entry zones were the gold standard treatment for chronic neuropathic pain, and only in 1967 neuromodulation techniques were introduced with SCS by Shealy et al. (1967) and Gildenberg (2006). In the attempt to clarify the mechanism through which SCS can improve pain perception, many experiments demonstrated that SCS inhibits the activity of WDR neurons located in the deep lamina of the spinal dorsal horns (Guan et al., 2010; Yakhnitsa et al., 1999). These neurons are involved in the spinal processing of neuropathic pain (Simone et al., 1991). The paresthesias experienced during tonic conventional stimulation suggest that afferent pathways are tonically activated; on the other hand, the detection of an alteration in mechanical pain thresholds is controversial (Meier et al., 2015; Larson et al., 1974; Rasche et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2015). Moreover, SCS has been observed to inhibit the excitatory synaptic transmission along the superficial dorsal horns at the second lamina in the long term (Sdrulla et al., 2015). Regarding the association with medical therapy, there is evidence that intrathecal baclofen (a GABAb receptor agonist), may improve pain control both in rats and in poor responders (Meyerson et al., 1997; Cui et al., 1996; Schechtmann et al., 2010; Lind et al., 2004). The fact that SCS seems to have an effect in the activation of supraspinal regions, through the transmission of action potentials along the dorsal columns, might explain its improvement of pain even in its experiential component located in the brain (Saade et al., 1986). A clear efficacy of tonic conventional SCS has been reported in the literature as the effective treatment of FBSS (Grider et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2014b; Cameron, 2004a). In addition, strong evidence has been given and reported to the use of tonic conventional SCS for the treatment of CRPS (Kemler et al., 2000). Conventional SCS is operated through the creation of an epidural electric field based on the generation of tonic pulses of square waves released at a constant frequency between 40 and 80 Hz and a pulse width between 200 and 450 μs and varying current amplitudes (Schechter et al., 2013; Yearwood et al., 2010). No one has ever explained why conventional SCS can decrease pain by 50% and usually not more (Taylor et al., 2014c). This is why new patterns of stimulation were developed looking for a more effective stimulation on a larger percentage of patients.

9. High-frequency stimulation

Considering high-frequency stimulation, comprising frequencies of around 10,000 Hz or anyhow largely higher than the frequencies used for tonic conventional stimulation (40–80 Hz), the 10 KHz stimulation is the most studied and reported one in literature (Tiede et al., 2013).

This represents an additional paresthesia-free technique that seems to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain although its mechanism of action is still mostly unknown (Van Buyten et al., 2013).

A better efficacy of high-frequency stimulation compared to conventional tonic stimulation on both back and leg pain was reported in a randomized study on 198 patients with an equal percentage of undesired side effects between the two groups (Kapural et al., 2016b). On the contrary, a recent paper on an independent clinical trial comparing conventional SCS and high-frequency stimulation showed a similar effect in 60 patients affected by FBSS (De Andres et al., 2017).

In a case report, somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) were equally recorded and equally inhibited at different frequencies from 60 Hz to 10 kHz (Buonocore and DeMartini, 2016).

A possible unconfirmed action of high-frequency stimulation on axonal conduction block, axonal activity, and glial-neuronal interaction has been investigated and recently reviewed and claimed to represent the mechanism through which high-frequency stimulation decreases pain.

A multicenter prospective study reported that 70% of patients treated by high-frequency SCS experienced a significant and lasting improvement in low back and leg pain, which was higher than the 50% commonly reported with the tonic conventional spinal cord stimulation (Kapural et al., 2016b). Conversely, no relevant differences were observed between a short two-week long trial period of sham stimulation and high-frequency 5 KHz stimulation in a randomized study including 33 patients (De Andres et al., 2017).

10. Burst stimulation

Burst stimulation represents the late development of a new pattern of electrical spinal stimulation introduced by De Ridder (De Ridder et al., 2010). It consists of intermittent trains of five high-frequency stimuli delivered at 500 Hz, 40 times per second. This technique is characterized by a long pulse width and an interspike interval of 1000 μs delivered in constant-current mode. These monophasic pulses are balanced to the charge at the end of the burst, unlike the clustered high-frequency tonic firing. Burst stimulation has two main advantages: the bursting trains of stimuli can intercept a larger number of nerve fibers along the spinal cord posterior columns; on the other hand, patients do not feel any paresthesia due to the stimulation (De Ridder et al., 2015). Many reports demonstrated an equal and even better capacity to control neuropathic pain with burst stimulation in comparison to conventional tonic SCS. Moreover, the same reports documented a better acceptance by those patients who do not perceive any stimulation-induced paresthesia (Schu et al., 2014). Furthermore, as burst stimulation can reach more nerve fibers in the dorsal columns, it may be better suited to control midline neuropathic lumbar pain (Kriek et al., 2017).

Although burst stimulation is considered to control pain due to its broad action on medial pain pathways, thereby interfering with the affective/attentional component of pain, no differences were reported in the patient’s activity and psychosocial assessments (De Ridder et al., 2015; Schu et al., 2014). On the contrary patients with CRPS showed a better acceptance of standard SCS, although pain control was similar in both burst and standard stimulation (Kriek et al., 2017; Muhammad et al., 2017).

Research using a rat model indicated that burst SCS could diminish visceromotor reflexes and activity in the dorsal column nuclei triggered by painful stimuli. However, in contrast to traditional stimulation methods, burst SCS did not alter the spontaneous activity of neurons in the gracile nucleus. Consequently, it is believed that burst SCS does not impact the dorsal column–medial lemniscal pathways (Tang et al., 2014).

An additional advantage of burst stimulation is that the correct level of the implant of the electrode is not crucial to extend the effect of stimulation to the area with pain.

If the therapeutic value of burst stimulation will be confirmed in the future, the use of neurophysiological monitoring during surgical implantation could become unnecessary, allowing both surgical and percutaneous procedures to be carried out in a shorter time (Deer et al., 2017b; Falowski et al., 2018).

Furthermore, a major spread of the effect of stimulation to the midline seems to be a characteristic trait of burst stimulation. This could improve even back lumbar pain in FBSS. This advantage seems to be related to the higher chance of interfering with the conduction of stimuli along the deep nerve fibers by means of the trains of higher-frequency impulses (Perruchoud et al., 2013).

Both burst stimulation and high-frequency stimulation could be promising techniques to relieve chronic neuropathic pain, although larger case series of patients still need to be followed up on long term.

11. Dorsal ganglion stimulation

Dorsal ganglion stimulation consists of a technique to percutaneously implant a curved lead electrode close to the dorsal ganglion under X-ray guidance and after selecting the right spinal level corresponding to the dermatome affected by pain. One or more electrodes can be implanted in a patient according to the extension of the painful area. A comparison between conventional tonic SCS and dorsal root ganglion stimulation was reported as a randomized prospective accurate trial (Deer et al., 2017a). Both techniques proved to be effective, but the dorsal root ganglion stimulation showed a significant improvement in terms of pain relief, postural stability, and mood improvement (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Fig. 1.

The illustration highlights the standard spinal cord stimulation technique with the pulse waves of major patterns of stimulation.

Table 2.

Overview of major SCS Patterns of stimulation.

| Patterns of stimulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indications | Advantages | Drawback | Technical features | |

| Conventional “Tonic” stimulation | 1) FBSS 2) CRPS |

Inhibits the activity of WDR neurons located in the deep lamina of the spinal dorsal horns involved in the spinal processing of neuropathic pain | Pain reduction of about 50%. Perception of paresthesias |

Frequency: 40–80 Hz Pulse width: 347–591 microsec Amplitude: 3.6–8.5 mA |

| High-frequency stimulation | 1) FBSS 2) CRPS |

Paresthesia-free technique Back and leg pain better control Pain reduction of about 70% |

Mechanism of action is still mostly unknown. Lack of strong evidence in favor of its use |

Frequency: 10.000 Hz Pulse width: 30 microsec Amplitude: 1.6–3.8 mA |

| Burst stimulation | 1) FBSS 2) CRPS 3) Post-herpetic neuralgia 4) Lumbar pain of the midline |

Paresthesia-free technique Burst trains of stimuli intercept a larger number of nerve fibers along the spinal cord posterior columns |

Lack of strong evidence in favor of its use | Frequency: 200 Hz Pulse width: 1000 microsec Amplitude: 0.6 mA |

| Dorsal ganglion stimulation | 1) Refractory lower extremity pain related to CRPS 2) Localized areas of neuropathic pain |

Significant improvement in terms of pain relief, postural stability, and mood improvement | Need for strict dermatome selection. Steep learning curve |

Percutaneous technique with X-ray-guided curved lead electrode placement close to the dorsal ganglion |

12. Side effects and complications of spinal cord stimulation

Complications of SCS can be divided into technical, biological, and therapy-related, some of which may require surgical intervention. Among the former, the most frequent technical complications are represented by electrode dislodgement, followed by lead rupture/malfunction, and (with a minor frequency) by pulse generator malfunction or battery premature discharge (North et al., 2005; Meyerson et al., 1990; Mullett et al., 1992). Electrode dislodgement (which can occur along both the vertical and horizontal axes) usually requires surgical revision (Kumar and Wilson, 2007). Kumar et al. identified 88 lead migrations (21.4%) out of 410 patients; displacements occurred with a frequency that was significantly higher in the cervical cord compared to the dorsal one, with 40 being repositioned and 48 replaced (Kumar et al., 2008).

Lead fracture and malfunction have been described by many authors and vary up to 10.2%. A review of Cameron et al. comprising 2753 cases reported a rate of 9.1% of lead-related issues (Cameron, 2004b). The site of fracture is usually located where the lead penetrates the spinal canal, distal to the fixation point where the lead is anchored to the deep fascia (Kumar et al., 2008).

Infections are another critical complication, emphasizing the need for meticulous preoperative and postoperative management (Eldabe et al., 2016). Technological advancements and improvements in surgical techniques, such as the introduction of rechargeable implantable pulse generators and the use of intraoperative neuromonitoring, have been developed to mitigate the risk of complications like lead migration, thereby enhancing patient safety. Infection rates range between 2.5% and 10% between studies (Eldabe et al., 2016). Potential risk factors include autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition status, very thin body habitus, BMI>30, use of corticosteroids, urinary and/or fecal incontinence, and malabsorption syndrome (Follett et al., 2004). Numerous papers indicated the pocket of the pulse generator to be the most frequent site of infection. The most frequent pathogens involved in hardware infections are staphylococcus and pseudomonas (Follett et al., 2004). Less frequently, especially when dealing with paddle electrodes, the occasional occurrence of either subdural or epidural hematomas may be seen.

Epidural hematomas present a specific risk, with a reported incidence of 0.32% in SCS patients (West et al., 2023). The overall incidence of any hematoma in these patients is approximately 0.81%, underlining the relatively low but important risk associated with the procedure (West et al., 2023).

Complications associated with therapy, such as paresthesias experienced during traditional tonic stimulation, have been effectively addressed by the latest generation of pulse generators. These advanced devices are equipped with the capability to detect the patient’s position and adjust the stimulation parameters accordingly. This innovation has significantly mitigated variations in paresthesias and their effects, which previously depended on the patient’s posture, thereby enhancing the overall efficacy of the treatment. Dural puncture, skin erosion, and direct neurological injury are other rare complications that have been reported in literature.

13. Future perspectives for spinal cord stimulation

Several clinical investigations have recently pointed out the SCS potential to enable recovery of gait functions in spinal cord injury (SCI) (Calvert et al., 2019a).

Specifically, SCI may cause disruption and functional alterations of intra-spinal circuits and supra-segmental connections, leading to para-tetraplegia or dysfunctional locomotion patterns. Evidence from pre-clinical studies, however, has shown that the spinal network often possesses a residual and flexible state of excitability and plasticity even after a severe central nervous system damage. In this context, the SCS-generated electrical rhythmic output might serve as substrate to facilitate and modulate standing, stepping movements and walking.

Despite the promising rationale behind, to date SCS for the treatment of gait disorders in SCI still relies on a fragmented literature, mainly based upon anecdotical case reports and small, single-center case series.

Epidural SCS inception for SCI was mainly based on animals' studies demonstrating the existence of the so-called spinal central pattern generator (CPG) (Calvert et al., 2019a). Briefly, in cats CPG seems to be the intrinsic spinal cord neuronal network responsible for the basic walking motor sequence. Additional findings revealed that cats, following an experimental transection of the spinal cord, retained the ability to perform locomotor functions when placed on a treadmill. This capability was attributed to the preservation of the CPG, which successfully generated rhythmic, walking-like movements in response to epidural SCS. This underscores the CPG’s critical role in facilitating adaptive locomotion despite significant spinal injuries (Grillner and Zangger, 1975; Grillner and Rossignol, 1978; Jankowska et al., 1967; Calvert et al., 2019b). If the proofs of mammalian spinal CPG were quite solid in animal’s studies, evidence of spinal CPGs in humans remained a topic of debate until the 1990s, when Dimitrijevic et al. confirmed the presence of a human CPG by applying non-rhythmic epidural SCS to the lumbosacral sensorimotor networks of individuals with complete spinal cord injuries (Dimitrijevic et al., 1998; Bussel et al., 1996). Dimitriijevic's work demonstrated that the human spinal cord could generate locomotor‐like activity with little to no brain input, and that spinal circuitry involved in creating rhythmic motor output to the lower limbs might reside entirely within the lumbosacral spinal cord segments. Since then, twenty-two studies have described the use of epidural SCS in human SCI to the best of our knowledge. They are mostly represented by single case reports or small case series for a total of 90 patients included.

The first relevant therapeutic application of epidural SCS as a rehabilitative therapeutic was performed by Herman et al. in 2002 (Herman et al., 2002). The purpose of the study was to evaluate the augmentation of the use-dependent plasticity generated by partial weight bearing therapy (PWBT) by means of epidural SCS in a subject who had an incomplete cervical SCI (ASIA B). Main outcomes analyzed were average gait speed, stepping symmetry, sense of effort, physical work capacity, and whole-body metabolic activity. These parameters were then compared between PWBT alone, which was considered as a baseline, and PWBT plus concomitant epidural SCS. The results obtained were quite surprising. The latter combination, indeed, greatly improved both the time required and the sense of effort experienced in performing an overground walking across a 15 m. More interestingly, after a few months of training, these gains were equalized by PWBT alone, suggesting a learned behaviour in response to epidural SCS, although at longer distances (e.g., 50–250 m) performance with SCS remained still considerably superior.

The study conducted by Harkema et al., published in The Lancet in 2011, stands as a significant milestone in the recent advancements of using epidural SCS as a supplementary treatment for SCI (Harkema et al., 2011). The methods applied were similar to those used by Herman et al., and consisted basically of a physical rehabilitation period alone followed by the addition of epidural SCS. Over a period of 26 months, following 170 locomotor training sessions (LTSs), the authors installed a 16-contact paddle lead spanning the L1-S1 segments of the spine. This setup facilitated a total of 29 combined sessions of locomotor training and spinal cord stimulation (LTSs-SCS). The aim of the surgical intervention was to achieve standing and stepping in a 23-year-old man, who suffered from motor complete and sensory incomplete paraplegia as a consequence of a motor vehicle accident.

Although no functional gain was observed after the initial physical therapy stage, add-on epidural SCS was able to initiate and sustain full weight-bearing standing. These achievements correlated with a significant increase in electromyography (EMG) muscle activation during epidural SCS compared to non-stimulation standing and with specific stimulation parameters. More surprisingly, 7 months after implantation, the patient recovered epidural SCS-mediated supraspinal control of some leg movements. This discovery strongly suggests that, in cases of SCI, the residual neural networks within the spinal cord, including sensory input from the lower limbs and any remaining supraspinal descending pathways, can be not only activated but potentially revived to a functional state. Furthermore, these networks may be repurposed to generate walking-like motor outputs.

Encouraged by the promising preliminary results, the same American group published 3 years after a follow-up study, including three additional participants (Angeli et al., 2014). The main result of the study was that among the subjects enrolled, three out of four were able to execute voluntary movements with epidural SCS soon after implantation, two of whom had previous complete loss of both motor and sensory function (ASIA A). In other words, for the first-time individuals diagnosed with clinically motor complete SCI were shown to develop functional connectivity across previously damaged spinal tissue thanks to epidural SCS. As highlighted by the authors, this discovery calls into question the existing methodology used to classify a patient as having a clinically complete SCI and to determine that no recovery is feasible. More recently, researchers from the Mayo Clinic replicated the outcomes reported by Harkema et al. (2011) and Grahn et al. (2017). They reported a case of chronic traumatic paraplegia in which 8 sessions of epidural lumbo-sacral SCS enabled (within 2 weeks from implantation) volitional control of task-specific muscle activity, volitional control of rhythmic muscle activity to produce step-like movements while side-lying, independent standing, and while in a vertical position with body weight partially supported, voluntary control of steplike movements and rhythmic muscle activity. These results were confirmed in a consequent follow-up study including two additional subjects. Interestingly, in this paper the authors also explored the feasibility of epidural SCS-evoked motor responses as an intra-operative aid for the epidural lead positioning (Gill et al., 2018). Epidural electrical stimulation (EES)-evoked motor responses were recorded from selected leg muscles and displayed in real time to ensure the lead proximity to spinal cord regions capable of eliciting motor response from the lower extremities.

All the above-mentioned studies show that spinal networks possess a flexible state of excitability and functionality that can be facilitated by EES to enable motor function in upper limbs in individuals with tetraplegia as well as in lower limbs in individuals with paraplegia. Nevertheless, some controversial aspects warrant a more thorough discussion. For what concerns intervention type, for instance, there is no consensus, as the authors positioned electrodes at different spinal cord levels: whilst in six studies a stimulation mode involving lumbar metameres was applied, only two authors used an exclusive thoracic positioning. As far as stimulation parameters are concerned, instead, they were rather variable amongst the studies so far published on the argument: frequencies used, in fact, ranged from 2.2 Hz to 120 Hz. In particular, this parameter showed a crucial role in selecting muscular groups: some authors have demonstrated that low frequencies can produce an “extensor pattern” response, while high frequencies can lead up to flexor muscles contraction. Furthermore, studies by Jilge et al. and Minassian et al. demonstrated that high-frequency stimulation can trigger step-like motor activity. Rejc et al. also emphasized the influence of cathode positioning on motor outcomes, noting that placing the cathode in the caudal region of the array led to more effective EMG patterns for standing behaviour. All eight studies revealed that the role of afferent fibers of the dorsal roots is fundamental for the efficacy of epidural spinal stimulation in these patients, thus suggesting that proprioceptive input coordinates the residual motor pool activity. Some authors drew further conclusions, indeed their studies proved that SCS can also restore supraspinal connectivity, allowing partial voluntary motor control. Specifically, in the research conducted by Harkema et al., control was achieved exclusively during active stimulation, whereas Wagner et al.’s findings demonstrated that voluntary motor control persisted even in the absence of EES. In addition, Carhart et al. showed that epidural spinal-cord stimulation can facilitate learning of a functional overground walking pattern with and without the acute application of stimulation. Harkema et al. were the only authors to demonstrate that SCS may have an impact in improving autonomic bladder function and sexual and thermoregulatory activity besides the capacity of producing a step-like activity. Arguably, the most compelling evidence suggests that a multi-modal rehabilitation (MMR) approach, which emphasizes dynamic training across various motor tasks alongside EES-enhanced spinal network activity, represents the optimal paradigm for promoting synergistic functional reorganization of supraspinal-spinal connectivity. Another interesting finding was that stimulation parameters had to be tailored to the individual and activity. This implies that stimulation parameters that were optimal for one subject were far less efficacious when applied to others. In addition, task-specific training appears critical to enable a desired motor function via EES. Stand training with EES improved standing ability in all four individuals tested. However, step training without stand training decreased EES-enabled standing ability.

Indeed, recovery in SCI is influenced by a range of factors, including the extent and location of the injury, the patient’s overall health and age, the timing and type of interventions, and the neuroplasticity of the spinal cord (Fouad et al., 2021). These factors can interact in complex ways, making it challenging to isolate the specific impact of SCS on motor rehabilitation. In addition, neuroplasticity, which can vary greatly between individuals, can significantly influence the effectiveness of therapies like SCS (Fouad et al., 2021).

The timing of the intervention is another critical factor. The stage of injury when SCS is implemented can affect its efficacy. Early intervention might lead to better outcomes compared to later stages, where chronic changes might have set in (Fouad et al., 2021).

The use of SCS for neuropathic pain due to SCI shows promise but lacks a robust evidence base, necessitating further research. One case report highlighted the successful application of SCS in a patient with SCI-related neuropathic pain, demonstrating significant pain relief (Rosales et al., 2022). However, a review underscores the current reliance on case studies and low-quality evidence, advocating for prospective clinical trials to better evaluate SCS’s efficacy and safety (Dombovy-Johnson et al., 2020). Mechanistic studies suggest that SCS modulates pain through various neural pathways, indicating its potential to treat both peripheral and central neuropathic pain, including that resulting from SCI (Sun et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the gap in high-quality research and the need for further studies to establish its therapeutic value persist (Lagauche et al., 2009).

14. Discussion

Regardless of the technique chosen to treat a patient with SCS, proper selection of the patient is of paramount importance to achieve the best results from this specific neuromodulation treatment.

This is important to note, as a consistent fraction of patients suffering from FBSS after having undergone spinal surgery exhibit signs of persistent compression of the neural elements. In this regard, a thorough radiological investigation with a spinal CT scan or MRI would be recommended to exclude any possible need for further spine surgery, before proceeding with an eventual SCS implantation.

The decision on whether to use a trial period before the final implant or a direct implant is still under debate, although it seems that the percentage of responders, after a proper selection of clinical features, is similar in the two groups. Kumar et al. reported that about 17–20% of patients who underwent a trial period of stimulation decided not to proceed with the permanent implant despite the properly located sensation of paresthesias and control of pain during the trial (Kumar et al., 2006). Indeed, SCS may determine both technical and biological complications. Electrode dislocation and breakage represent the most reported technical complications, followed by pulse generator or battery failures (Meyerson et al., 1990). On the other hand, infections, CSF leakage, and pain located at the incision, electrode, or receiver site are frequent biological adverse events (Meyerson et al., 1990). In fact, a varying percentage of infections (2.4–18.6%) was reported in literature relative to the use of the trial period (Cameron, 2004b; Eldabe et al., 2016; Follett et al., 2004). A markedly lower percentage of infections and complications has been reported by neurosurgeons in a homogeneous case series from a multicenter study on patients who underwent the surgical procedure of implant for spinal cord stimulation (Blackburn et al., 2021).

Besides the aforementioned considerations, the real utility and predictive value of a trial phase of SCS, compared to direct permanent implantation, has only been reported once in prospective, randomized, and controlled trials (Blackburn et al., 2021).

Additionally, the decision on whether to implant a lead or a paddle electrode remains largely a matter of personal preference. However, with a paddle electrode, if there is enough epidural space to properly position it, the electric field is only oriented toward the dural surface thus saving energy that would otherwise be dispersed through the spherical electric fields induced by lead electrodes. Moreover, a lead electrode might be more prone to dislodgement.

Although surgery for SCS is considered reversible and minimally invasive, some (rare) severe adverse events may occur such as spinal epidural bleeding and permanent neurological deficits, but a higher incidence of hardware complications and infections was reported (24–50% and 7.5%, respectively) (Kumar et al., 2006; May et al., 2002; Hoelzer et al., 2017).

Regarding the different types of stimulation patterns, no definite evidence-based guidelines exist on which is the most appropriate method in relation to the specific type of neuropathic pain. Both burst stimulation and high-frequency stimulation are innovative techniques that reduce the risk of paresthesias compared with conventional stimulation. Furthermore, the effectiveness of burst stimulation in managing pain seems to be independent of the specific site where the electrodes are implanted. Future studies are needed to evaluate the best patterns of stimulation.

Moreover, the final decision on whether to implant a non-rechargeable or a rechargeable pulse generator depends both on the age of the patient and the energy consumption of each patient. In this regard, the choice is usually held back mainly by an economic factor, as rechargeable pulse generators are largely more expensive than conventional ones.

Finally, SCS’s role in motor rehabilitation must be viewed within the broader context of a multidisciplinary approach to SCI treatment, whose effectiveness is influenced by a multitude of factors. The underutilization of SCS for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain is a significant issue despite its proven efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. Comparative randomized trials have demonstrated the superiority of SCS over conventional medical management and reoperation in conditions like CRPS and FBSS (Fontaine, 2021).

The evidence suggests that the underuse of SCS may stem from a lack of awareness and differing perspectives among healthcare providers regarding its efficacy and role in pain management. This calls for increased education on the benefits and indications of SCS among healthcare professionals to bridge the gap between its potential and actual use, ensuring that patients who could benefit from this therapy are appropriately considered (Fontaine, 2021).

15. Conclusion

Although SCS has demonstrated its efficacy in the treatment of FBSS and CRPS, as well as in motor rehabilitation for SCI, it remains a largely underutilized therapy. Indeed, the importance of an adequate patient selection is a crucial process for SCS. Novel protocols of stimulation (burst stimulation and high frequency stimulation) may improve the trade-off between therapeutic benefits and potential side effects. Likewise, decreasing the rates of hardware-related complications will also be paramount in increasing the employment of this therapy in clinical settings. Moreover, although many centers adopt a trial period before definitive implantation, its utility has still to be demonstrated.

Funding sources for study

None.

Ethical compliance statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Image credits to GC.

Handling Editor: Prof F Kandziora

References

- Aarabi B. Personalising pain control with spinal cord stimulation. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):103–104. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30484-3. Epub 2019 Dec 20. PMID: 31870767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aïm F., Klouche S., Frison A., Bauer T., Hardy P. Efficacy of vitamin C in preventing complex regional pain syndrome after wrist fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2017;103(3):465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.12.021. Epub 2017 Mar 4. PMID: 28274883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli C.A., Edgerton V.R., Gerasimenko Y.P., Harkema S.J. Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 5):1394–1409. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbalinardo S., Loer S.A., Goebel A., Perez R.S. The treatment of longstanding complex regional pain syndrome with oral steroids. Pain Med. 2016;17(2):337–343. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv002. PMID: 26814238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchini J., Tchachaghian S., Shamaa F., Jabbur S.J., Meyerson B.A., Song Z., Linderoth B., Saadé N.E. Spinal segmental and supraspinal mechanisms underlying the pain-relieving effects of spinal cord stimulation: an experimental study in a rat model of neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2012;215:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.057. Epub 2012 Apr 28. PMID: 22548781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barolat G. Epidural spinal cord stimulation: anatomical and electrical properties of the intraspinal structures relevant to spinal cord stimulation and clinical correlations. Neuromodulation. 1998;1(2):63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.1998.tb00019.x. PMID: 22150938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky D., Yampolsky C. Is spinal cord stimulation safe? A review of its complications. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.06.012. Epub 2013 Jul 11. PMID: 23851231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M.I., Attal N., Backonja M.M., Baron R., Bouhassira D., Freynhagen R., Scholz J., Tölle T.R., Wittchen H.U., Jensen T.S. Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127(3):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.034. Epub 2006 Dec 19. PMID: 17182186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn A.Z., Chang H.H., DiSilvestro K., Veeramani A., McDonald C., Zhang A.S., Daniels A. Spinal cord stimulation via percutaneous and open implantation: systematic review and meta-analysis examining complication rates. World Neurosurg. 2021;154:132–143.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.07.077. Epub 2021 Jul 31. PMID: 34343680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira D., Lanteri-Minet M., Attal N., Laurent B., Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore M., DeMartini L. Inhibition of somatosensory evoked potentials during different modalities of spinal cord stimulation: a case report. Neuromodulation. 2016;19:882–884. doi: 10.1111/ner.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussel B., Roby-Brami A., Neris O.R., Yakovleff A. Evidence for a spinal stepping generator in man. Electrophysiological study. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 1996;56(1):465–468. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert J.S., Grahn P.J., Zhao K.D., Lee K.H. Emergence of epidural electrical stimulation to facilitate sensorimotor network functionality after spinal cord injury. Neuromodulation. 2019;22(3):244–252. doi: 10.1111/ner.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert J.S., Grahn P.J., Zhao K.D., Lee K.H. Emergence of epidural electrical stimulation to facilitate sensorimotor network functionality after spinal cord injury. Neuromodulation. 2019;22(3):244–252. doi: 10.1111/ner.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron T. Safety and efficacy of spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain. A 20 year literature review. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100:254–267. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.3.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron T. Safety and efficacy of spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain: a 20-year literature review. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100:254–267. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.3.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C.M., Buenaver L.F., Raja S.N., Kiley K.B., Swedberg L.J., Wacnik P.W., et al. Dynamic pain phenotypes are associated with spinal cord stimulation-induced reduction in pain: a repeated measures observational pilot study. Pain Med. 2015;16:1349–1360. doi: 10.1111/pme.12732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas D.D., Nieshoff E.C., Suda K., Goto S., Sanin L., Kaneko T., Sporn J., Parsons B., Soulsby M., Yang R., Whalen E., Scavone J.M., Suzuki M.M., Knapp L.E. A randomized trial of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain due to spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2013;80(6):533–539. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281546b. Epub 2013 Jan 23. PMID: 23345639; PMCID: PMC3589291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragee E.J., Alamin T.F., Miller J.L., Carragee J.M. Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J. 2005;5(1):24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.250. PMID: 15653082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C.W., Peng P. Failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med. 2011;12(4):577–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C., Quinn A., Wilson F. The aetiologies of failed back surgery syndrome: a systematic review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2017;30(3):395–402. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S.P., Vase L., Hooten W.M. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2082–2097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7. PMID: 34062143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L., Ludman T., Bouhassira D., Baron R., Dickenson A.H., Yarnitsky D., Freeman R., Truini A., Attal N., Finnerup N.B., Eccleston C., Kalso E., Bennett D.L., Dworkin R.H., Raja S.N. Neuropathic pain. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2. PMID: 28205574; PMCID: PMC5371025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E.V., Mandelli C., Mortini P., Messina G., De Marco N., Donati R., Irace C., Landi A., Lavano A., Mearini M., Podetta S., Servello D., Zekaj E., Valtulina C., Dones I. Epidural spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic pain: a neurosurgical multicentric Italian data collection and analysis. Acta Neurochir. 2015;157(4):711–720. doi: 10.1007/s00701-015-2352-5. Epub 2015 Feb 3. PMID: 25646850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J.G., Linderoth B., Meyerson B.A. Effects of spinal cord stimulation on touch-evoked allodynia involve GABAergic mechanisms. AN experimental study in the mononeuroathic rat. Pain. 1996;66:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A., Olofsen E., Sigtermans M., Noppers I., Niesters M., Aarts L., Bauer M., Sarton E. Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of ketamine-induced pain relief of chronic pain. Eur. J. Pain. 2011;15(3):258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.06.016. Epub 2010 Jul 17. PMID: 20638877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniell J.R., Osti O.L. Failed back surgery syndrome: a review article. Asian Spine J. 2018;12(2):372–379. doi: 10.4184/asj.2018.12.2.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K.D., Treede R.D., Raja S.N., Meyer R.A., Campbell J.N. Topical application of clonidine relieves hyperalgesia in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 1991;47(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90221-i. PMID: 1664508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deer T.R., Krames E., Mekhail N., Pope J., Leong M., Stanton-Hicks M., Golovac S., Kapural L., Alo K., Anderson J., Foreman R.D., Caraway D., Narouze S., Linderoth B., Buvanendran A., Feler C., Poree L., Lynch P., McJunkin T., Swing T., Staats P., Liem L., Williams K. Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. The appropriate use of neurostimulation: new and evolving neurostimulation therapies and applicable treatment for chronic pain and selected disease states. Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(6):599–615. doi: 10.1111/ner.12204. discussion 615. PMID: 25112892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deer T.R., Levy R.M., Kramer J., Poree L., Amirdelfan K., Grigsby E., Staats P., Burton A.W., Burgher A.H., Obray J., Scowcroft J., Golovac S., Kapural L., Paicius R., Kim C., Pope J., Yearwood T., Samuel S., McRoberts W.P., Cassim H., Netherton M., Miller N., Schaufele M., Tavel E., Davis T., Davis K., Johnson L., Mekhail N. Dorsal root ganglion stimulation yielded higher treatment success rate for complex regional pain syndrome and causalgia at 3 and 12 months: a randomized comparative trial. Pain. 2017;158(4):669–681. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000814. PMID: 28030470; PMCID: PMC5359787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deer T.R., Lamer T.J., Pope J.E., Falowski S.M., Provenzano D.A., Slavin K., et al. The neurostimulation appropriateness consensus committee (NACC) safety guidelines for the reduction of severe neurological injury. Neuromodulation. 2017;20:15–30. doi: 10.1111/ner.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Andres J., Monsalve Dolz V., Fabregat-Cid G., Villanueva- Perez V., Harutyiunyan A., Asensio-Samper J.M., et al. Prospective, randomized blind effect-on-outcome study of conventional vs high-frequency spinal cord stimulation in patients with pain and disability due to failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med. 2017;18:2401–2421. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D., Vanneste S., Plazier M., van der Loo E., Menovsky T. Burst spinal cord stimulation: toward paresthewsia-free pain suppression. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:986–990. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000368153.44883.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D., Plazier M., Kamerling N., Menovsky T., Vanneste S. Burst spinal cord stimulation for limb and back pain. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(5):642–649.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.040. Epub 2013 Jan 12. PMID: 23321375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D., Vanneste S., Plazier M., Vancamp T. Momicking the brain: evaluation of StJude medical’s prodigy chronic pain system with burst technology. Expet Rev. Med. Dev. 2015;12:143–150. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2015.985652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevic M.R., Gerasimenko Y., Pinter M.M. Evidence for a spinal central pattern generator in humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;860:360–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombovy-Johnson M.L., Hunt C.L., Morrow M.M., Lamer T.J., Pittelkow T.P. Current evidence lacking to guide clinical practice for spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: a review of the literature and a proposal for future study. Pain Pract. 2020;20(3):325–335. doi: 10.1111/papr.12855. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 31691496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khoury C., Hawwa N., Baliki M., Atweh S.F., Jabbur S.J., Saadé N.E. Attenuation of neuropathic pain by segmental and supraspinal activation of the dorsal column system in awake rats. Neuroscience. 2002;112(3):541–553. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00111-2. PMID: 12074897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldabe S., Buchser E., Duarte R.V. Complications of spinal cord stimulation and peripheral nerve stimulation techniques: a review of the literature. Pain Med. 2016;17:325–336. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falowski S.M., Sharan A., McInerney J., Jacobs D., Venkatesan L., Agnesi F. Nonawake vs awake placement of spinal cord stimulators: a prospective, multicentre study comparing safety and efficacy. Neurosurgery. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup N.B., Sindrup S.H., Jensen T.S. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. PMID: 20705215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup N.B., Attal N., Haroutounian S., McNicol E., Baron R., Dworkin R.H., Gilron I., Haanpää M., Hansson P., Jensen T.S., Kamerman P.R., Lund K., Moore A., Raja S.N., Rice A.S., Rowbotham M., Sena E., Siddall P., Smith B.H., Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. Epub 2015 Jan 7. PMID: 25575710; PMCID: PMC4493167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follett K.A., Boortz-Marx R.L., Drake J.M., et al. Prevention and management of intrathecal drug delivery and spinal cord stimulation system infec- tions. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1582–1594. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine D. Spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic pain. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 2021;177(7):838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.07.014. Epub 2021 Aug 9. PMID: 34384626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad K., Popovich P.G., Kopp M.A., et al. The neuroanatomical-functional paradox in spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021;17(1):53–62. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00436-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freynhagen R., Strojek K., Griesing T., Whalen E., Balkenohl M. Efficacy of pregabalin in neuropathic pain evaluated in a 12-week, randomised, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial of flexible- and fixed-dose regimens. Pain. 2005;115(3):254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.032. Epub 2005 Apr 18. PMID: 15911152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freynhagen R., Baron R., Gockel U., Tölle T.R. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006;22(10):1911–1920. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132488. PMID: 17022849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch E.W., Heisel J., Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine. 1996;21:626–633. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghostine S.Y., Comair Y.G., Turner D.M., Kassell N.F., Azar C.G. Phenoxybenzamine in the treatment of causalgia. Report of 40 cases. J. Neurosurg. 1984;60(6):1263–1268. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.6.1263. PMID: 6726371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildenberg P.L. History of electrical neuromodulation for chronic pain. Pain Med. 2006;7 doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00118.x. S7–S13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M.L., Grahn P.J., Calvert J.S., et al. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat. Med. 2018;24(11):1677–1682. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman P.K. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;151(6):737–748. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253. Epub 2007 Apr 30. PMID: 17471183; PMCID: PMC2014120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel A., Baranowski A., Maurer K., Ghiai A., McCabe C., Ambler G. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of the complex regional pain syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;152(3):152–158. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-3-201002020-00006. PMID: 20124231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorson K.C., Schott C., Herman R., Ropper A.H., Rand W.M. Gabapentin in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a placebo controlled, double blind, crossover trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;66(2):251–252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.251. PMID: 10071116; PMCID: PMC1736215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn P.J., Lavrov I.A., Sayenko D.G., et al. Enabling task-specific volitional motor functions via spinal cord neuromodulation in a human with paraplegia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017;92(4):544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grider J.S., Manchikanti L., Carayannopoulos A., Sharma M.L., Balog C.C., Harned M.E., et al. Effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation in chronic spinal pain. A systematic review. Pain Physician. 2016;19:E33–E54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S., Rossignol S. On the initiation of the swing phase of locomotion in chronic spinal cats. Brain Res. 1978;146(2):269–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S., Zangger P. How detailed is the central pattern generation for locomotion? Brain Res. 1975;88(2):367–371. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Wacnik P.W., Yang F., Carteret A.F., Chung C.Y., Meyer R.A., et al. Spinal cord stimulation – induced analgesia: electrical stimulation of dorsal columns and dorsal roots attenuates dorsal horn neuronal excitability n neuropathic rats. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1392–1405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcd95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halicka M., Vittersø A.D., Proulx M.J., Bultitude J.H. Neuropsychological changes in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) Behav. Neurol. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/4561831. PMID: 32399082; PMCID: PMC7201816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden R.N., Bruehl S., Stanton-Hicks M., Wilson P.R. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):326–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00169.x. PMID: 17610454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema S., Gerasimenko Y., Hodes J., et al. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet (London, England) 2011;377(9781):1938–1947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman R., He J., D’Luzansky S., Willis W., Dilli S. Spinal cord stimulation facilitates functional walking in a chronic, incomplete spinal cord injured. Spinal Cord. 2002;40(2):65–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer B.C., Bendel M.A., Deer T.R., Eldridge J.S., Walega D.R., Wang Z., et al. Spinal cord stimulator implant infection rates and risk factors: a multicentre retrospective study. Neuromodulation. 2017;20:558–562. doi: 10.1111/ner.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S., Kamiya M., Nishihara M., Arai Y.P., Ikemoto T., Ushida T. Prevalence, characteristics, and burden of failed back surgery syndrome: the influence of various residual symptoms on patient satisfaction and quality of life as assessed by a nationwide Internet survey in Japan. J. Pain Res. 2017;10:811–823. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S129295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E., Jukes M.G., Lund S., Lundberg A. The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord. 5. Reciprocal organization of pathways transmitting excitatory action to alpha motoneurones of flexors and extensors. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1967;70(3):369–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1967.tb03636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapural L., Yu C., Doust M.W., Gliner B.E., Vallejo R., Sitzman B.T., Amirdelfan K., Morgan D.M., Yearwood T.L., Bundschu R., Yang T., Benyamin R., Burgher A.H. Comparison of 10-kHz high-frequency and traditional low-frequency spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic back and leg pain: 24-month results from a multicenter, randomized, controlled pivotal trial. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(5):667–677. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001418. PMID: 27584814; PMCID: PMC5058646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapural L., Yu C., Doust M.W., Gliner B.E., Vallejo R., Sitzman B.T., et al. Comparison of 10 KHz high-frequency and traditional low-frequency spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic back and leg pain: 24 month results from a multicenter, randomized, controlled pivotal trial. Neurosurgery. 2016;79:667–677. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemler M.A., Barendse G.A., Van Kleef M., De Vet H.C., Rijks C.P., Furnee C.A., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in patients with chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:618–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008313430904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]