Abstract

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common reason for mortality and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost globally. This study aimed to suggest a new gene list for the treatment of CAD by a systematic review of bioinformatics analyses of pharmacogenomics impacts of potential genes and variants.

Methods

PubMed search was filtered by the title including Coronary Artery Disease during 2020–2023. To find the genes with pharmacogenetic impact on the CAD, additional filtrations were considered according to the variant annotations. Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), Gene-miRNA Interactions (GMIs), Protein-Drug Interactions (PDIs), and variant annotation assessments (VAAs) performed by STRING-MODEL (ver. 12), Cytoscape (ver. 3.10), miRTargetLink.2., NetworkAnalyst (ver 0.3.0), and PharmGKB.

Results

Results revealed 5618 publications, 1290 papers were qualified, and finally, 650 papers were included. 4608 protein-coding genes were extracted, among them, 1432 unique genes were distinguished and 530 evidence-based repeated genes remained. 71 genes showed a pharmacogenetics-related variant annotation in at least (entirely 6331 annotations). Variant annotation assessment (VAA) showed 532 potential variants for the final report, and finally, the concluding PGs list represented 175 variants. Based on the function and MAF, 57 nonsynonymous variants of 29 Pharmacogenomics-related genes were associated with CAD.

Conclusion

Conclusively, evaluating circulating miR33a in individuals’ plasma with CAD, and genotyping of rs2230806, rs2230808, rs2487032, rs12003906, rs2472507, rs2515629, and rs4149297 (ABCA1 variants) lead to precisely prescribing of well-known drugs. Also, the findings of this review can be used in both whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) analysis in the prognosis and diagnosis of CAD.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Pharmacogenetics, Drug, GWAS, Variant

Highlights

-

•

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

-

•

Genetic biomarkers are increasingly introduced for the diagnosis and treatment of CAD.

-

•

This review mainly focuses on recent reports of genomics and proteomics data associated with CAD.

-

•

This review covers the recent pharmacogenomics-associated genes, variants, and miRNAs with CAD.

-

•

Potential variants for personalized medicine and miRNAs for detection of CAD are discussed.

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the foremost reason of death and loss of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) worldwide. Low and middle-income countries bear a disproportionate share of this burden, accounting for almost 7 million deaths and 129 million DALYs each year [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. CAD was responsible for 8.9 million fatalities and 164.0 million DALYs in 2015 [6]. Survivors of Myocardial Infarction (MI) are at increased risk of repeated infarction and have a five to six times higher yearly death rate than non-CAD patients [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. Overall, the age-adjusted prevalence of MI hospitalization was 215/100,000 people between 1979 and 1981, then grew until 1987, stable in the next decade, and then began to fall beginning in 1996, reaching 242/100,000 people in 2005 [7,[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Despite the fact that the incidence of death from CAD has dropped over the previous four decades, it still accounts for over one-third of fatalities in those over the age of 35. Nearly fifty percent of the decrease in mortality can be attributed to improved therapy of the acute phase of ACS and accompanying comorbidities such as acute heart failure, enhanced primary and secondary preventive methods, and chronic angina revascularization [7]. Different geographical locations might possess a genetic susceptibility to CAD risk factors, like metabolic syndrome, which is a risk factor in South Asia [16,17].

Significant progress has been achieved in understanding the genetics of cardiovascular disease (CVD) during the previous decade. McPherson defined that the genetic architecture of CAD is mostly driven by the combined impact of numerous common variants, each of which contributes little to disease risk when considered separately. This is in contrast to rare variants having significant influences on the incidence of coronary disease [18]. The identification of these common variations follows the publication of massive genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on a bigger view [19,20]. Since 2007, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found links between CAD and 321 chromosomal loci [21,22]. By examining the whole genome, CAD GWASs discovered numerous novel genes with earlier unrecognized importance for atherosclerosis and retrieved existing therapy candidates and genes recognized to raise disease risk. These findings suggest new disease-causing pathways. The extensive outcomes of GWAS research are increasingly being examined for translational reasons in the post-GWAS age. The goals of these investigations are (a) understanding the disease-related processes underlying CAD loci; (b) prioritizing causative genes and prospective innovative therapeutic targets; and (c) using CAD genetic variants for stratification incidence, prevention of disease, and personalized medicine [23]. GWAS is designed to have the greatest sensitivity for finding impacts of common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). Simultaneously growing sequence coverage of the human genome permitted the detection of several variants with low frequencies, allowing researchers to investigate whether the signals at risk loci are caused by common or uncommon variants. The findings fascinatingly and unmistakably showed that the common variants with small impact sizes are mostly responsible for the overall genetic predisposition to CAD identified through GWAS sites [24]. These common variations are often found in assumed regulatory regions of the genome, which means they usually alter gene expression and hence the complicated network which links the function of numerous genes [23]. Further research, such as whole-exome sequencing (WES) and exome array, focused on the gene encoding sequences. Rare loss-of-function mutations in ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1 that are connected to CAD were found by Stitziel et al. pointing to potential new treatment targets [25]. While ANGPTL4 and LPL are already being explored in the management of hypertriglyceridemia, SVEP1, a not well-known gene, has been functionally verified to have an atheroprotective impact on mice [[26], [27], [28]]. WES was employed in a study to discover rare variants for CAD/MI in a noticeable patient cohort of 9793 individuals [29]. Particularly rare APOA5 and LDLR alleles demonstrated an exome-wide significant correlation with MI (p 8107), indicating that a larger sample size may be necessary to identify rarer variants. Unite Kingdom BioBank (UKBB) will provide ES data from 200,000 people by the end of 2020. More unique uncommon variations for CAD are likely to be uncovered using comparable datasets from different biobanks, which will help in treatment discovery [23].

Abundant CAD-related genes detected by GWAS may be druggable, as evidenced by the fact that many candidate responsible genes at CAD loci are medical drug targets, including 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) (statins), APOB (Mipomersen), and PCSK9 (respective antibodies or inhibitors), as well as gene targets currently undergoing pre-clinical evaluations [30,31]. Indeed, associations between rare polymorphisms and CAD risk, GWAS findings, and associated system genetics are progressively being exploited for preclinical target prioritization and medication selection [29,[32], [33], [34]]. Loss-of-function mutations in ANGPTL4 (angiopoietin-like 4), a locally produced LPL inhibitor, have been correlated with hypolipidemia and atheroprotection. Several ANGPTL4 inhibitors have recently been in clinical studies and have indicated promise in reducing atherogenic dyslipidemia. As well as lipid metabolism genes, efforts have been made to investigate potential targets connected to GWAS results impacting inflammation and arterial wall dynamics [35]. Tragante et al. used accessible GWAS data on CAD to find drug-gene interactions and ranked options from a pool of current treatments (drug repurposing) [32]. According to the DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/), there are 21 genes with complete status of clinical trials for an FDA-approved drug related to CAD treatment which emphasizes the Pharmacogenetic importance of clinical and experimental findings. Based on these clues, and the lack of a comprehensive and concentrated study in pharmacogenomics of CAD in personalized medicine strategy of treatment, the present study systematically reviewed the recent reports of literature and carried out a new in silico analysis suggesting a potential druggable variant list for further studies and designed a gene panel of PGx-CAD for WES analysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection and preparation

PubMed search [November 22nd, 2023] was filtered by the title including Coronary Artery Disease from 2020 to 2023 and 5618 articles were found. In the next step, based on the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria second-layered filtration was carried out. Inclusion criteria were meta-analyses, review articles, original articles, GWAS, pharmacogenomics, and personalized medicine reports. The exclusion criteria were as follows: case reports, involving another disease such as opioid addiction, alcohol dependence, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, stroke, hyperthyroidism, hypertension, hyperuricemia, kidney disease, renal dysfunction, COVID-19, metabolic baseline, microbial infections, animal models (mouse, rat, etc.), menopause status, pneumonia, bowel, dietary pattern, Familial hypercholesterolemia, stress, anxiety, cancer, Kawasaki disease, and non-biological items including the association of walking, food, and internet with CAD.

2.2. Bioinformatics analyses

The current review aimed to uncover potential interactions and novel results by combining the raw data extracted from the recent Pubmed publications and analyzing the data in a superior level of in silico predictions. All of the in silico analyses were carried out by STRING-MODEL ver. 12 (https://string-db.org/), Cytoscape ver. 3.10 (https://cytoscape.org/), miRTargetLink.2. (https://ccb-compute.cs.uni-saarland.de/mirtargetlink2), and NetworkAnalyst (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/NetworkAnalyst/). Also, for the final filtration step, PharmGKB (https://www.pharmgkb.org/) was utilized to exclude the genes with no pharmacogenetic effect based on the documented significant variant annotations.

3. Results

3.1. Data preparation

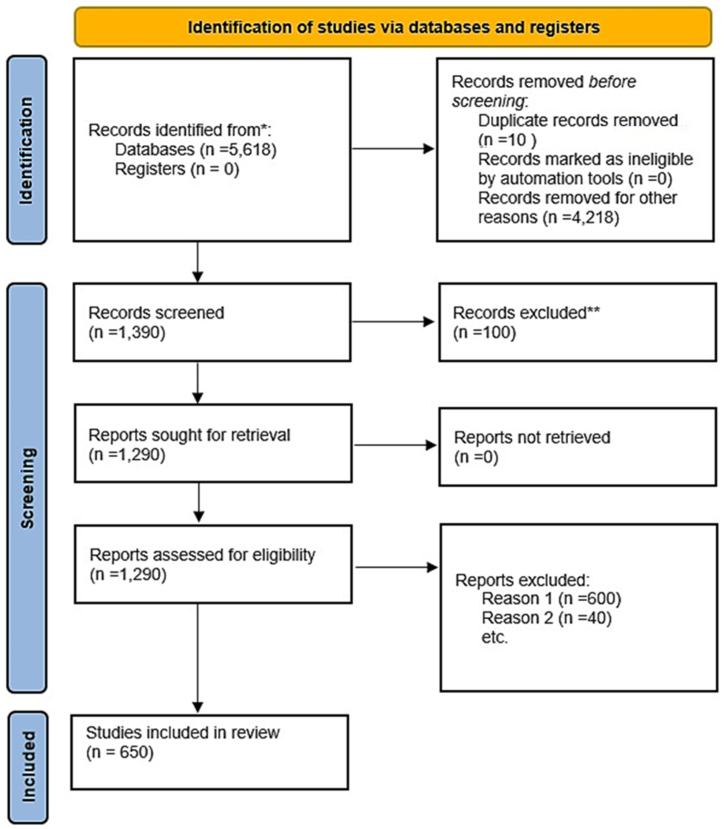

After deep investigation, 1290 papers were eligible for further insights, and 647 articles were discarded based on the exclusion criteria mentioned in the methods section. Also, 650 papers were included in the current review (Fig. 1). In total, 4608 protein-coding genes were found in 650 included papers. Many duplications were found; from which the most repeated genes were CRP (181 times), IL6 (129 times), TNF (99 times), ACE (97 times), APOB (89 times), IL1B (73 times), INS (70 times), APOE (64 times), APOA1 (59 times), and PCSK9 (52 times). By removing the duplications, 1432 unique genes were remained. Further analyses were performed on these final genes. To reach the genes which have pharmacogenetic impacts on the CAD, additional filtrations were considered according to the variant annotations. In the following sections, Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), Gene-miRNA Interactions (GMIs), Protein-Drug Interactions (PDIs), and variant annotation assessments (VAAs) were performed with details.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review for coronary artery disease from 2020 to 2023 publications in PubMed database. ** the excluded records were the papers with no direct focus on Coronary Artery Disease (CAD); and the Reason 1 for exclusion was the involvement of other disease such as opioid addiction, alcohol dependence, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, stroke, hyperthyroidism, hypertension, hyperuricemia, kidney disease, renal dysfunction, COVID-19, metabolic baseline, microbial infections; finally, the Reason 2 was case reports and animal models.

3.2. Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs)

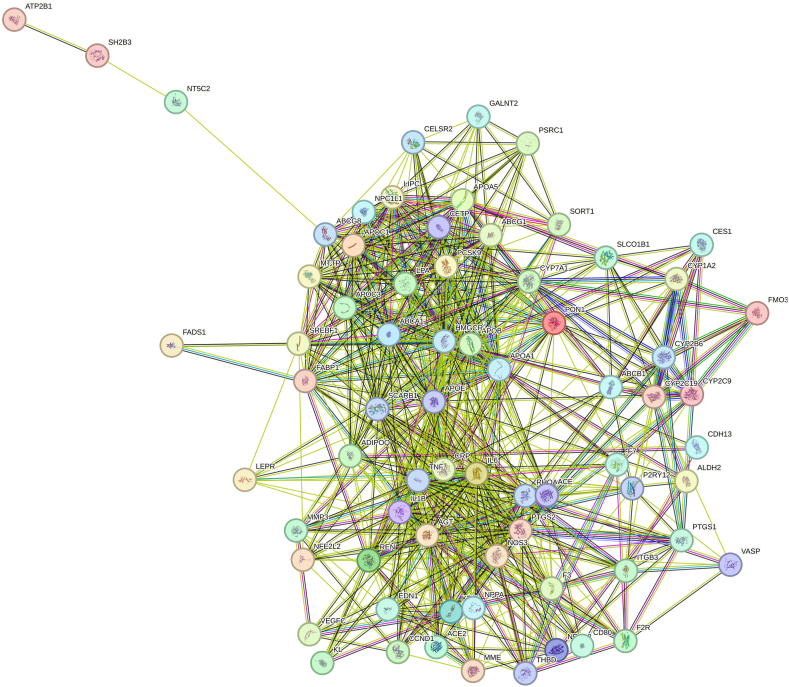

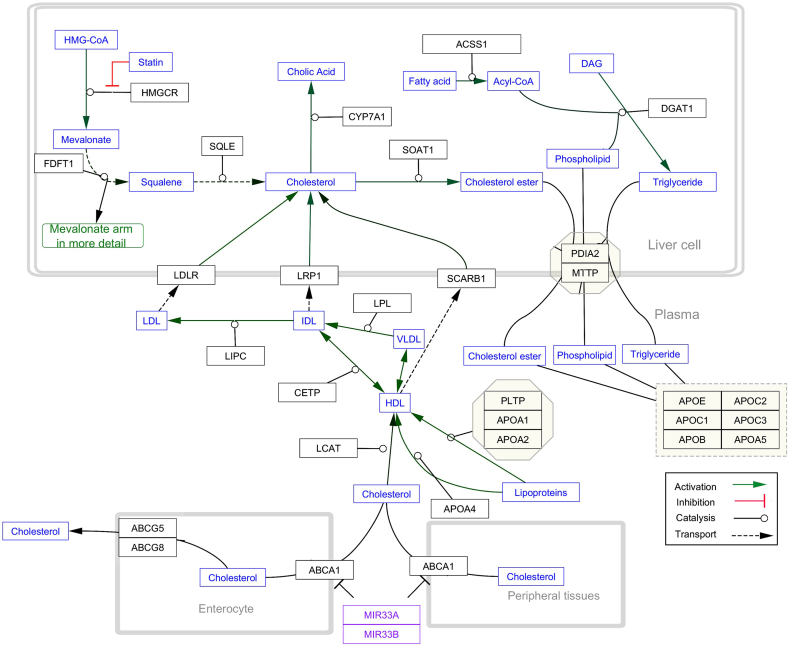

Primarily, STRING-MODEL was performed for 1432 proteins to find the unrelated and related proteins. Some proteins did not interact in the superior network including C2CD4C, EMP2, HyLS1, ATPSCKMT, and TEKT5. PPI enrichment p-value was <1.0e-16. To be more reliable and focused, only replicated proteins (genes) were selected for further steps of analysis. Thus, 898 unreplicated genes were eliminated and 530 evidence-based repeated genes remained. STRING-MODEL showed a completely interacted network of these 530 proteins (Figure not shown). The results of Cytoscape also represented the most significant curated pathways including malignant pleural mesothelioma (p-value: 2.45e-35), statin inhibition of cholesterol production (p-value:1.2e-15), and platelet-mediated interactions with vascular and circulating cells (3.34e-6). To reach a targeted gene list, the next step of filtering was finding the genes with pharmacogenomics effects which was possible through searching the related variant annotations with blood situation in the PharmGKB (https://www.pharmgkb.org/). Searching for genes with pharmacogenetic annotations represented that among 530 genes, 71 genes had a pharmacogenetics variant annotation at least. STRING-MODEL output of these PGx confirmed the fully-interacted proteins (Fig. 2). Cytoscape analysis displayed that statin inhibition of cholesterol production had the highest score compared with the other pathways (p-value = 2.87e-20) (Fig. 3). This pathway indicates noticeable genes and miRNAs including ABCA1, APOA4, APOB, APOC1, APOC2, APOC3, APOC5, ABCG1, ABCG5, CETP, SCARB1, CYP7A1, hsa-miR-33a, and hsa-miR-33b.

Fig. 2.

STRING-MODEL of 71 genes with pharmacogenomics impacts in coronary artery disease risk.

Fig. 3.

The most significant signaling pathway of 71 genes resulted from Cytoscape.

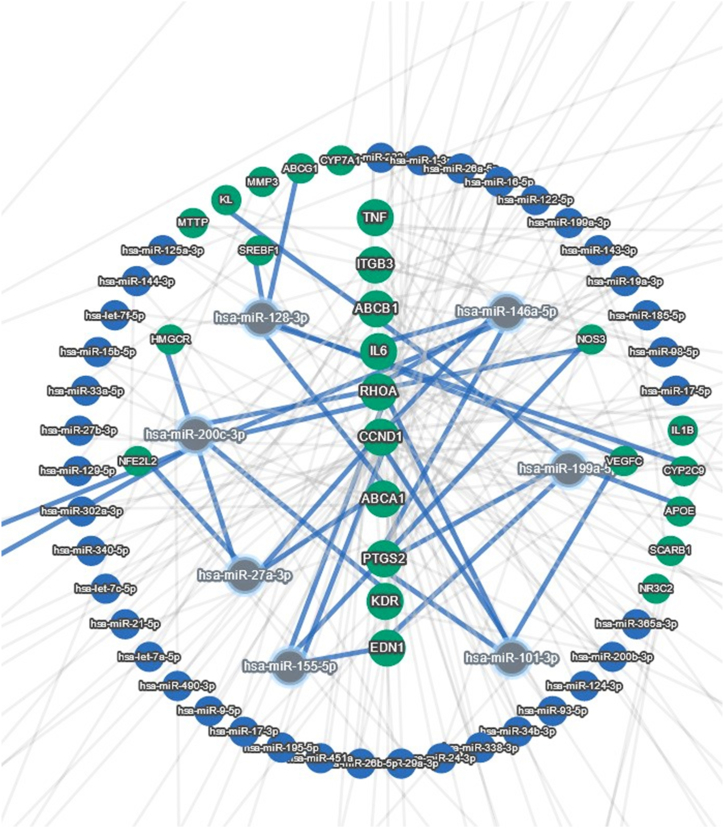

3.3. Gene-miRNA interactions (GMI)

The final 71 pharmacogenomics-based genes were then tested by the miRTargetLink2 to uncover the novel plausible gene-miR interactions. The concentric model was adjusted for only the strong evidence-based interactions and the central genes in this model were TNF, ITGB3, ABCB1, IL6, RHOA, CCND1, ABCA1, PTGS2, KDR, and EDN1. Notably, hsa-miR-146a-5p, has-miR128–3p, has-miR-101–3p, has-miR27a-3p, has-miR155–5p, has-miR199a-5p, and has-miR200c-3p had the most interacted miRNAs in this GMI network (Fig. 4). Interestingly, hsa-miR-33a was common in Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Concentric model of gene-miR interactions (GMI) visualized by miRTargetLink2.

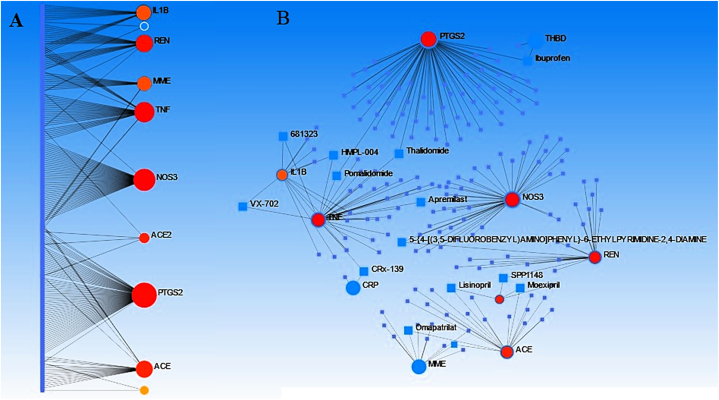

3.4. Protein-Drug interaction (PDI)

Via NetworkAnalyst (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/NetworkAnalyst/), another in silico prediction was done for Protein-Drug interaction (PDI) among the 71 genes. The results of this bioinformatics data signified an interesting PDI among PTGS2, NOS3, TNF, REN, MME, IL1B, and ACE. According to this network, there are some linking drugs which could be considered as the potential candidate for CAD management such as Pomalidomide, Thalidomide, HMPL-004, 681,323, VX-702, Ampremilast, CRx-139, 5-6-ETHYLPYRIMIDINE-2,4-DIAMINE, SPP1148, Moexipril, Lisinopril, and Omapatrilat [1] (Fig. 5 A, B).

Fig. 5.

Protein-drug interactions (PDIs) of the genes with the most drug interactions illustrated by NetworkAnalyst server both in general (A) and detailed (B) networks.

3.5. Variant annotations assessments (VAA)

To suggest the right gene list for pharmacogenes (PGs) associated with CAD, the current study examined the 6331 annotations of related variants of 71 PGs. The inclusion criteria for potentially related variants were as follows: the significant level specified with yes and also; the p-value should be lower than the 0.05 threshold. Findings from VAA indicated that 532 variants had the potential to be considered. Therefore, the final PGs list according to the deeply matched annotations with CAD showed 175 variants divided into three categories according to the dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/) and Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). The first category consists of structural (missense and nonsynonymous) variants. Additionally, we searched for the clinical trial status of related drugs related to CAD. The completed status of clinical trials for each drug represents its reliability for prescribing based on the genotypes of individuals with CAD (Table 1). The second category consists of non-coding regulatory variants including Promoter, Transcription factor binding, enhancer, CTCF, and splicing (Table 2); and the third category comprises intronic, intergenic, upstream, and downstream variants which might not be described by molecular changes at least yet but may be in the future (Table 3). 57, 33, and 80 variants are indicated with genomic details in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, respectively. The results summarized in the Tables can be utilized to highlight the remarkable actionable variants and consequently their genes. Both variant function and minor allele frequency (MAF) can prioritize some genes in the more potential PGx. In other words, the missense variants and variants with higher MAF (at least >0.05) can be listed in a group for exome gene panels with pharmacogenetic effects. According to Table 1 which indicates the missense or nonsynonymous variants, 29 genes can be prioritized including ABCA1, ABCB1, ACE, AGT, ALDH2, APOB, APOC1, APOE, CES1, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, EDN1, F7, FABP1, FMO3, ITGB3, KDR, LEPR, NOS3, NPPA, NR3C2, NT5C2, P2RY12, PON1, PTGS1, SCARB1, SH2B3, SLCO1B1, and TLR4. These genes can be considered for WES analysis for CAD patients or detecting CAD risk in healthy individuals as prognostic data.

Table 1.

Variant annotation assessment including the structural variants of pharmacogenes-associated with CAD.

| Genes | Variant | Function | MAF | Drugs | Clinical trial for CAD | Association | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | rs2230806 | missense | 0.44 | Pravastatin | Completed | Genotype TT is associated with increased HDL-cholesterol when treated with pravastatin in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype CC. | 19673941 |

| ABCA1 | rs2230808 | missense | 0.46 | Fenofibrate | Unknown | Genotype CC is associated with increased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotype TT. | PMC3598593 |

| ABCB1 | rs2032582 | missense | 0.33 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Allele T is associated with increased risk of Hemorrhage when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele A. | 28589365 |

| ABCB1 | rs1045642 | missense | 0.4 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Genotypes AA + AG are associated with decreased response to clopidogrel in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype GG. | 25542807 |

| ABCB1 | rs1128503 | synonymous | 0.42 | Simvastatin | Completed | Genotype GG is associated with decreased response to simvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotypes AA + AG. | 16321621 |

| ABCG8 | rs11887534 | missense | 0.06 | – | – | Genotype CG is associated with increased risk of Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotype GG. | PMC3833422 |

| ACE | rs4343 | synonymous | 0.36 | – | – | Allele G is associated with increased ACE activity in people with Hypertension as compared to allele A. | 20066004 |

| AGT | rs4762 | missense | 0.1 | Benazepril | Unknown | Allele G is associated with increased response to benazepril in people with Hypertension. | 17261659 |

| AGT | rs699 | missense | 0.29 | Irbesartan | Unknown | Genotype GG is associated with decreased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotypes AA + AG. | 20538124 |

| ALDH2 | rs671 | missense | 0.04 | Nitroglycerin | Completed | Genotypes AA + AG is associated with decreased response to nitroglycerin in children with Heart Defects, Congenital as compared to genotype GG | 31250045 |

| APOB | rs676210 | missense | 0.37 | Fenofibrate | Unknown | Genotype AA is associated with increased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotypes AG + GG. | PMC2952572 |

| APOB | rs1801701 | missense | 0.04 | Irbesartan | Unknown | Genotype CC is associated with increased response to irbesartan in people with Hypertrophy, Left Ventricular as compared to genotypes CT + TT. | 15614026 |

| APOB | rs1367117 | missense/promoter | 0.13 | Irbesartan | Unknown | Genotype GG + AG is associated with response to irbesartan in people with Hypertension. Allele G is associated with increased risk of Hemorrhage when treated with warfarin in people with heart valve replacement. | PMC524175 |

| APOB | rs13306198 | stopgained | 0.01 | Apixaban; dabigatran; edoxaban; rivaroxaban | Unknwon; Terminated; Active Not Recruiting; Active Not Recruiting |

Genotypes AA + AG is associated with increased likelihood of Hemorrhage when treated with apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban or rivaroxaban as compared to genotype GG. | 36145636 |

| APOC1; APOE | rs429358 | missense | 0.15 | Warfarin | Completed | Allele T is associated with LDL-C response when treated with atorvastatin in people with Coronary Disease. Genotypes CC + CT is associated with increased Hypertriglyceridemia in people with Coronary Disease or Hypertension as compared to genotype TT. | 20031582 |

| APOC1; APOE | rs7412 | missense | 0.08 | Warfarin | Completed | Genotypes CT + TT is associated with increased percent reduction in LDL-cholesterol when treated with atorvastatin or pravastatin in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype CC, etc. | 19667110 |

| CES1 | rs146456965 | missense | 0.01 | Clopidogrel; enalapril; sacubitril | Completed; Unknown; Unknown |

Allele A is associated with decreased metabolism of when assayed with clopidogrel, enalapril and sacubitril in HEK cells as compared to allele C. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs202001817 | missense | 0.01 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Allele A is associated with decreased enzyme activity of when assayed with clopidogrel in HEK cells as compared to allele G. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs202121317 | missense | 0.06 | Enalapril | Unknown | Allele C is associated with decreased enzyme activity of when assayed with enalapril in HEK cells as compared to allele A. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs71647871 | missense | 0.03 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Genotype CT is associated with decreased on-treatment ADP-induced platelet aggregation when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype CC, etc. | PMC3682407 |

| CES1 | rs201065375 | missense | 0.01 | Clopidogrel; enalapril; sacubitril | Completed; Unknown; Unknown |

Allele A is associated with decreased metabolism of clopidogrel, enalapril and sacubitril in HEK cells as compared to allele G. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs2307240 | missense | 0.05 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased response to clopidogrel in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype CC. | PMC5543069 |

| CES1 | rs143718310 | missense | 0.01 | Clopidogrel; enalapril; sacubitril | Completed; Unknown; Unknown |

Allele G is associated with decreased metabolism of when assayed with clopidogrel, enalapril and sacubitril in HEK cells as compared to allele T. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs200707504 | missense | 0.01 | Clopidogrel; enalapril; sacubitril | Completed; Unknown; Unknown |

Allele C is associated with decreased enzyme activity of when assayed with clopidogrel, enalapril and sacubitril in HEK cells as compared to allele T. | PMC5637814 |

| CES1 | rs151291296 | stopgained | 0.01 | Clopidogrel; enalapril; sacubitril | Completed; Unknown; Unknown |

Allele C is associated with decreased enzyme activity of when assayed with clopidogrel, enalapril and sacubitril in HEK cells as compared to allele A. | PMC5637814 |

| CETP | rs5882 | missense | 0.47 | Simvastatin | Completed | Allele A is associated with increased response to simvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to allele G./Allele G is associated with increased response to rosuvastatin as compared to allele A. | 17931083 |

| CYP2B6 | rs8192709 | missense | 0.05 | Cyclophosphamide | Unknown | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic cystitis when treated with cyclophosphamide in people with recipients of HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as compared to genotype CC. | 19005482 |

| CYP2B6 | rs3745274 | missense | 0.32 | – | Genotype TT is associated with decreased expression of CYP2B6 as compared to genotypes GG + GT. | PMC4931886 | |

| CYP2C9 | rs1057910 | missense | 0.05 | – | Allele C is associated with decreased risk of Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele A, etc. | 21047199 | |

| EDN1 | rs5370 | missense/ctcf/promoter | 0.25 | Atenolol; irbesartan | Completed; Unknown |

Genotypes GT + TT are not associated with response to atenolol and irbesartan in women with Essential hypertension as compared to genotype GG. | 15188945 |

| F7 | rs6046 | missense | 0.14 | Warfarin | Completed | Genotype AA is associated with increased sensitivity and risk of over-anticoagulation to warfarin during induction when treated with warfarin as compared to genotypes AG + GG. | 22071881 |

| FABP1 | rs2241883 | missense | 0.22 | Fenofibrate | Unknown | Genotypes CC + CT are associated with increased risk of Hypertriglyceridemia when treated with fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotype TT, etc. | 15249972 |

| FMO3 | rs1736557 | missense/enhancer | 0.1 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Genotype AA is associated with decreased risk of high on-treatment platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotypes AG + GG, etc. | 33089397 |

| ITGB3 | rs5918 | missense | 0.09 | Aspirin | Completed | Genotype CT is associated with increased blood loss when exposed to aspirin in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotype TT, etc. | 16153930 |

| KDR | rs1870377 | missense | 0.21 | Sorafenib | Unknown | Allele T is associated with increased risk of Hypertension when treated with sorafenib as compared to genotype AA. | PMC2913951 |

| LEPR | rs1805094 | missense | 0.14 | Atorvastatin | Completed | Genotype GG is associated with increased bone marrow density in the lumbar spine when treated with atorvastatin in people with Acute coronary syndrome. | 19023160 |

| LEPR | rs1137101 | missense | 0.42 | Simvastatin | Completed | Genotype GG is associated with increased percentage change in HDL-C levels when treated with simvastatin in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype AA. | 18854995 |

| LPA | rs3798220 | missense | 0.05 | Aspirin | Completed | Genotype CT is associated with decreased risk of Myocardial Infarction when treated with aspirin in women. | PMC2678922 |

| NOS3 | rs1799983 | missense | 0.18 | Aspirin; Beta Blocking Agents; clopidogrel; hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Completed; -, Completed,- |

Allele T is associated with increased risk of in-stent restenosis when treated with aspirin, Beta Blocking Agents, clopidogrel and hmg coa reductase inhibitors in men with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele G./Genotype GG is associated with increased response to salvianolic acid b in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotypes GT + TT./Genotypes GT + TT is associated with decreased expression of NOS3 mRNA as compared to genotype GG. | 22890915 |

| NPPA | rs5065 | stoplost/ctcf | 0.18 | Chlorthalidone | Unknown | Allele G is associated with decreased major adverse cardiac events (mace) when treated with chlorthalidone in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype AA. | 18212314 |

| NR3C2 | rs5522 | missense/enhancer | 0.11 | Enalapril | Unknown | Genotype TT is associated with increased response to enalapril in people with Hypertension as compared to genotypes CC + CT. | 24059494 |

| NT5C2 | rs10883841 | missense | 0.08 | Peginterferon alfa-2a | Genotype CT is associated with decreased likelihood of cryoglobulinemia when treated with peginterferon alfa-2a in people with as compared to genotype TT. | 28453396 | |

| P2RY12 | rs6785930 | missense | 0.24 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Allele A is associated with increased risk of neurological events when treated with clopidogrel in people with Peripheral Vascular Diseases as compared to genotype GG, etc. | 15933261 |

| P2RY12 | rs6809699 | synonymous | 0.09 | Clopidogrel | Completed | Genotypes AA + AC is associated with increased resistance to clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype CC. | PMC9801627 |

| PCSK9 | rs11591147 | missense/promoter | 0.01 | Atorvastatin | Completed | Allele T is associated with LDL-C response when treated with atorvastatin in people with Coronary Disease. | 20031582 |

| PON1 | rs662 | missense | 0.46 | Simvastatin | Completed | Allele C is associated with increased risk of major adverse cardiac events (mace) when treated with clopidogrel as compared to allele T./Genotype CC is associated with increased response to simvastatin in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype TT, etc. | PMC4752331 |

| PTGS1 | rs3842787 | missense/promoter | 0.06 | Rofecoxib | Unknown | Allele T is associated with reduction in COX-1 inhibition and depression of the urinary thromboxane metabolite when exposed to rofecoxib in healthy individuals as compared to allele C. | 16401468 |

| SCARB1 | rs4238001 | missense/promoter | 0.06 | Fenofibrate | Unknown | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotype CC. | PMC3836273 |

| SCARB1 | rs5888 | stoplost | 0.32 | Atorvastatin | Completed | Genotype AA is associated with increased response to atorvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotypes AG + GG. | 20064494 |

| SH2B3 | rs3184504 | missense | 0.15 | Candesartan | Completed | Allele T is associated with increased response to candesartan in people with Hypertension as compared to allele C. | 31327267 |

| SLCO1B1 | rs4149056 | missense | 0.09 | Simvastatin | Completed | Allele C is associated with increased likelihood of Muscular Diseases when treated with simvastatin in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele T, etc. | PMC5728073 |

| SLCO1B1 | rs11045819 | missense | 0.06 | Fluvastatin | Completed | Genotype CC is associated with decreased LDL-C reduction when treated with fluvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotypes AA + AC. | 18781850 |

| SLCO1B1 | rs34671512 | missense | 0.04 | Rosuvastatin | Completed | Allele C is associated with decreased exposure to rosuvastatin in healthy individuals as compared to allele A. | 30100615 |

| SLCO1B1 | rs2306283 | missense | 0.38 | Atorvastatin | Completed | Genotype AA is associated with increased clinical benefit to atorvastatin in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotypes AG + GG. | 35968761 |

| SLCO1B1 | SLCO1B1*5 (rs4149056) | missense | 0.09 | Lovastatin acid | NA | SLCO1B1 *5/*15 + *15/*15 are associated with increased exposure to lovastatin acid in healthy individuals as compared to SLCO1B1 *1/*1. | 26020121 |

| TLR4 | rs4986790 | missense | 0.06 | Pravastatin | Completed | Genotypes AG + GG are associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular events when treated with pravastatin in men with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotype AA. | 12742999 |

| TLR4 | rs4986791 | missense | 0.04 | Prednisolone | Unknwon | Allele T is associated with decreased clinical benefit to prednisolone in children with Thrombocytopenia as compared to allele C. | 37638833 |

MAF refers to minor allele frequency and etc means there is/are additional allelic/genotypic association(s) which is not stated here. Additionally, NA means Not Applicable.

Table 2.

Variant annotation assessment including the regulatory variants of pharmacogenes-associated with CAD.

| Genes | Variant | Function | MAF | Drugs | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | rs2487032 | enhancer | 0.4 | clopidogrel | Allele A is associated with increased metabolism of clopidogrel as compared to genotype GG. |

| ABCB1 | rs3213619 | promoter | 0.05 | atenolol | Allele G is associated with increased risk of Hypercholesterolemia due to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to allele A. |

| ACE | rs4291 | promoter | 0.35 | amlodipine; chlorthalidone; lisinopril | Genotypes AA + AT are associated with decreased fasting glucose when treated with amlodipine, chlorthalidone or lisinopril in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype TT. |

| ACE2 | rs2106809 | intronic/promoter | 0.32 | captopril | Genotype GG is associated with increased response to captopril in women with Hypertension as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| ADIPOQ | rs266729 | TFB site | 0.23 | Antihypertensives | Genotypes CG + GG is associated with increased severity of Hypertension when treated with Antihypertensives in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype CC. |

| AGT | rs5051 | promoter | 0.29 | atenolol | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased response to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype CC, etc. |

| AGT | rs5050 | promoter | 0.18 | aspirin | Genotype GG is associated with increased risk of Peptic Ulcer Hemorrhage when treated with aspirin as compared to genotypes GT + TT. |

| APOC1 | rs4420638 | enhancer | 0.15 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele G is associated with decreased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Cardiovascular Diseases or Hypercholesterolemia as compared to allele A. |

| APOE | rs449647 | ctcf | 0.2 | atorvastatin; bezafibrate | Genotypes AT + TT is associated with increased lipid-lowering effect when treated with atorvastatin or bezafibrate in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to genotype AA. |

| APOE | rs71352238 | promoter | 0.09 | rosuvastatin | Genotypes CC + CT are associated with decreased response to rosuvastatin as compared to genotype TT. |

| ATP2B1 | rs12817819 | enhancer | 0.07 | Antihypertensives | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased resistance to Antihypertensives in people with Coronary Artery Disease or Hypertension as compared to genotype CC. |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | splicing | 0.41 | Genotypes AA + AG is associated with increased transcription of CCND1 mRNA as compared to genotype GG. | |

| CES1 | rs8192935 | splicing | 0.42 | dabigatran | Genotypes AA + AG is associated with decreased dose-adjusted trough concentrations of dabigatran in people with Atrial Fibrillation as compared to genotype GG. |

| CETP | rs708272 | ctcf/enhancer | 0.38 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele A is associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular events when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele G, etc. |

| CETP | rs4783961 | enhancer | 0.44 | fluvastatin | Genotype GG is associated with increased response to fluvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| CETP | rs3764261 | enhancer | 0.29 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele A is associated with increased HDL cholesterol when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors. |

| F2R | rs168753 | splice polypyrimidine tract variant | 0.18 | aspirin; clopidogrel | Allele T is associated with decreased platelet reactivity when treated with aspirin and clopidogrel in people with Ischemic Attack, Transient or Stroke as compared to allele A. |

| IL6 | rs1800795 | intronic/promoter | 0.14 | fenofibrate | Genotypes CC + CG are associated with increased response to fenofibrate in patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease as compared to genotype GG. |

| KDR | rs7667298 | promoter | 0.5 | clopidogrel | Genotype CC is associated with decreased likelihood of Angina Pectoris when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotypes CT + TT. |

| KDR | rs2305948 | promoter | 0.5 | clopidogrel | Allele T is associated with decreased response to clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to allele C, etc. |

| KL | rs36217263 | promoter | 0.44 | Beta Blocking Agents | Genotypes A/del + del/del are associated with decreased response to Beta Blocking Agents in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype AA. |

| LIPC | rs1800588 | intronic/enhancer | 0.39 | simvastatin | Genotype CT is associated with increased response to simvastatin as compared to genotype TT, etc. |

| MED12L; P2RY12 | rs10935838 | intronic/enhancer | 0.13 | clopidogrel | Genotype AG is associated with decreased platelet aggregation when exposed to clopidogrel in healthy individuals as compared to genotype GG. |

| NFE2L2 | rs6721961 | intronic/promoter | 0.15 | estradiol | Allele T is associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism when treated with estradiol as compared to genotype CC. |

| NOS3 | rs2070744 | intronic/ctcf | 0.23 | atorvastatin | Genotype CC is associated with decreased erythrocyte plasma membrane fluidity when treated with atorvastatin in healthy individuals. |

| NPC1L1 | rs17655652 | promoter | 0.15 | pravastatin | Genotype CC is associated with increased reduction in LDL-C when treated with pravastatin in men as compared to genotypes CT + TT. |

| PON1 | rs705379 | intronic/promoter | 0.35 | atorvastatin; simvastatin | Genotypes AA + AG are associated with change in HDL-cholesterol when treated with atorvastatin or simvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia. |

| PTGS1 | rs10306114 | promoter | 0.05 | aspirin | Allele G is associated with increased risk of non-response to aspirin when treated with aspirin in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotype AA, etc. |

| PTGS2 | rs20417 | promoter | 0.2 | aspirin | Allele G is associated with decreased risk of Coronary Disease when treated with aspirin as compared to allele C, etc. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs2291073 | intronic/enhancer | 0.29 | lovastatin | Genotypes GT + TT are associated with increased response to lovastatin as compared to genotype GG. |

| SREBF1 | rs60282872 | promoter | 0.46 | fluvastatin | Genotype CC is associated with increased apolipoprotein A1 and C3 when treated with fluvastatin in people with Coronary Artery Disease. |

| THBD | rs1042580 | promoter | 0.3 | warfarin | Genotypes CC + CT is associated with decreased risk of Hemorrhage when treated with warfarin as compared to genotype TT. |

| TNF | rs1800629 | promoter | 0.09 | atorvastatin | Genotypes AA + AG is associated with increased activity of TNF as compared to genotype GG./Genotype GG is associated with increased bone marrow density in the lumbar spine when treated with atorvastatin in people with Acute coronary syndrome. |

TFB means transcription factor binding; MAF refers to minor allele frequency and etc means there is/are additional allelic/genotypic association(s) which is not stated here.

Table 3.

Variant annotation assessment including non-coding variants of pharmacogenes-associated with CAD.

| Genes | Variant | Function | MAF | Drugs | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | rs12003906 | intronic | 0.07 | atorvastatin; pravastatin; simvastatin | Allele C is associated with decreased response to atorvastatin, pravastatin or simvastatin in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to allele G. |

| ABCA1 | rs2472507 | intronic | 0.23 | – | Allele C is associated with increased expression of ABCA1 in HapMap cells. |

| ABCA1 | rs2515629 | intronic | 0.14 | – | Allele G is associated with increased expression of ABCA1 in HapMap cells. |

| ABCA1 | rs4149297 | intronic | 0.08 | – | Allele G is associated with increased expression of ABCA1 in HapMap cells. |

| ABCB1 | rs10267099 | intronic | 0.14 | atenolol | Allele G is associated with increased risk of Hypercholesterolemia due to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to allele A. |

| ABCB1 | rs1922242 | intronic | 0.38 | fluvastatin | Genotype AA is associated with increased response to fluvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotype AT. |

| ABCG1 | rs225440 | intronic | 0.43 | fluorouracil; irinotecan; leucovorin | Allele T is associated with increased risk of Neutropenia when treated with fluorouracil, irinotecan and leucovorin in people with Colorectal Neoplasms as compared to genotype CC. |

| ACE | rs4341 | 3utr | 0.47 | pravastatin | Genotypes CG + GG are associated with increased response to pravastatin as compared to genotype CC. |

| ACE | rs1799752 | intronic | na | quinapril | Genotypes ATACAGTCACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGAGACGGAGTCTCGCTCTGTCGCCC/del + del/del are associated with increased response to quinapril in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to genotype ATACAGTCACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGAGACGGAGTCTCGCTCTGTCGCCC/ATACAGTCACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGAGACGGAGTCTCGCTCTGTCGCCC. |

| ACE | rs4344 | intronic | 0.47 | ramipril | Genotypes AA + GG are associated with increased response to ramipril in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype AG. |

| ACE | rs4359 | intronic | 0.42 | ramipril | Genotypes CC + TT are associated with increased response to ramipril in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype CT. |

| AGT | rs7079 | 3utr | 0.19 | benazepril | Genotype TT is associated with increased response to benazepril in people with Hypertension as compared to genotypes GG + GT, etc. |

| AGT | rs943580 | intronic | 0.28 | Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids | Genotype GG is associated with decreased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| APOA1 | rs964184 | 3utr | 0.22 | fenofibrate | Allele G is associated with increased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to allele C. |

| APOA1 | rs2727786 | intronic | na | fenofibrate | Genotype CG is associated with decreased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotype CC. |

| APOA5 | rs662799 | intergenic | 0.16 | atorvastatin; rosuvastatin; simvastatin | Genotype AA is associated with response to atorvastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin in people with Dyslipidaemia as compared to genotypes AG + GG. |

| APOB | rs679899 | 3utr | 0.48 | warfarin | Allele G is associated with increased risk of Hemorrhage when treated with warfarin in people with heart valve replacement as compared to allele A. |

| APOC1; APOE | rs445925 | ncRNA | 0.15 | – | Allele A is associated with baseline LDL cholesterol in people with Vascular Diseases. |

| APOC3 | rs5128 | 3utr | 0.23 | protease inhibitors | Genotypes CG + GG are associated with decreased Hypertriglyceridemia when treated with protease inhibitors as compared to genotype CC. |

| APOC3 | rs2854116 | intergenic | 0.45 | protease inhibitors | Genotypes CC + CT are associated with decreased severity of Hypertriglyceridemia when treated with protease inhibitors as compared to genotype TT. |

| APOC3 | rs2854117 | intergenic | 0.5 | protease inhibitors | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with decreased severity of Hypertriglyceridemia when treated with protease inhibitors as compared to genotype CC. |

| ATP2B1 | rs17381194 | intronic | 0.06 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele T is associated with increased risk of Myalgia unspecified when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to allele C. |

| CD80 | rs34394661 | intergenic | 0.23 | clopidogrel | Genotype AA is associated with increased likelihood of high on-treatment platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotypes AG + GG. |

| CDH13 | rs11859453 | intronic | 0.43 | aspirin; clopidogrel | Genotypes AA + AG is associated with decreased likelihood of Coronary Restenosis or Disease Progression when treated with aspirin and clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotype GG. |

| CELSR2 | rs646776 | intergenic | 0.24 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele C is associated with increased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors as compared to allele T. |

| CELSR2; PSRC1 | rs602633 | intergenic | 0.25 | – | Allele T is associated with baseline LDL cholesterol in people with Vascular Diseases. |

| CES1 | rs8192950 | intronic | 0.37 | clopidogrel | Allele G is associated with decreased risk of Ischemic Attack, Transient and Stroke when treated with clopidogrel in people with Constriction, Pathologic as compared to allele T. |

| CES1 | rs2244613 | intronic | 0.33 | dabigatran | Genotypes GG + GT are associated with decreased risk of bleeding events when treated with Dabigatran in people with Atrial Fibrillation as compared to genotype TT, etc. |

| CETP | rs1532624 | intron | 0.31 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Genotype AA is associated with decreased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to genotype CC. |

| CRP | rs1205 | 3utr | 0.34 | rosuvastatin | Genotypes CT + TT are associated with increased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype CC, etc. |

| CYP1A2 | rs762551 | intronic | 0.37 | clopidogrel | Genotypes AA + AC are associated with decreased on-treatment platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel in people with cigarette smokers as compared to genotype CC. |

| CYP2B6 | rs70950385 | 3utr | na | – | Genotype CA/CA is associated with decreased activity of CYP2B6 as compared to genotype AG/AG. |

| CYP7A1 | rs3808607 | intergenic | 0.48 | atorvastatin | Genotype TT is associated with increased mean percentage reduction of triglycerides level when treated with atorvastatin in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to genotypes GG + GT. |

| F3 | rs841698 | intronic | 0.09 | Allele T is associated with increased expression of ABCD3 in HapMap cells. | |

| F3 | rs3917643 | intronic | 0.02 | simvastatin | Genotype CT is associated with increased response to simvastatin in people with Myocardial Ischemia as compared to genotype TT. |

| F7 | rs510317 | intergenic | 0.23 | warfarin | Genotypes AA + AG are associated with increased dose of warfarin as compared to genotype GG. |

| F7 | rs510335 | intergenic | 0.2 | warfarin | Genotypes GT + TT are associated with decreased warfarin dose when treated with warfarin as compared to genotype GG. |

| FADS1; FEN1; MIR611; TMEM258 | rs174541 | ncRNA | 0.3 | – | Allele T is associated with baseline LDL cholesterol in people with Vascular Diseases. |

| GALNT2 | rs2144300 | intronic | 0.33 | atenolol | Allele C is associated with Hypercholesterolemia due to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to allele T. |

| GALNT2 | rs2144297 | intronic | 0.43 | atenolol | Allele T is associated with Hypercholesterolemia due to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to allele C. |

| HMGCR | rs17671591 | intergenic | 0.4 | atorvastatin | Allele T is associated with LDL-C response when treated with atorvastatin in people with Coronary Disease./Genotypes CT + TT is associated with increased response to atorvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to genotype CC. |

| HMGCR | rs12654264 | intronic | 0.44 | – | Genotypes AT + TT are associated with increased serum total cholesterol as compared to genotype AA. |

| HMGCR | rs10474433 | intronic | 0.4 | atorvastatin | Allele T is associated with LDL-C response when treated with atorvastatin in people with Coronary Disease. |

| HMGCR | rs17244841 | intronic | 0.04 | pravastatin | Genotype AT is associated with decreased reduction in total cholesterol when treated with pravastatin as compared to genotype AA./Genotype AA is associated with increased reduction of LDL cholesterol when treated with simvastatin. |

| HMGCR | rs3846662 | ncRNA | 0.38 | – | Genotype GG is associated with increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level in basal state and possibly in response to atorvastatin. when treated with atorvastatin in healthy individuals as compared to genotype AA, etc. |

| HMGCR | rs17238540 | ncRNA | 0.04 | pravastatin | Genotype GT is associated with decreased reduction in total cholesterol when treated with pravastatin as compared to genotype TT. |

| IL1B | rs16944 | intergenic | 0.49 | pravastatin | Genotype GG is associated with increased coronary flow reserve when treated with pravastatin in men as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| KL | rs211247 | intergenic | 0.15 | Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids | Genotypes CG + GG are associated with increased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype CC. |

| LPA | rs10455872 | intronic | 0.02 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Genotypes AG + GG are associated with increased risk of Coronary Artery Disease when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors as compared to genotype AA./Allele G is associated with increased risk of Coronary Disease when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors as compared to allele A, etc. |

| MED12L; P2RY12 | rs5853517 | intronic | 0.24 | clopidogrel | Genotype T/del is associated with decreased platelet aggregation when exposed to clopidogrel in healthy individuals as compared to genotype del/del. |

| MED12L; P2RY12 | rs6801273 | intronic | 0.42 | clopidogrel | Allele T is associated with decreased residual on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele C. |

| MME | rs989692 | 5utr | 0.39 | Ace Inhibitors, Plain | Genotypes CT + TT is associated with increased likelihood of Angioedema when treated with Ace Inhibitors, Plain as compared to genotype CC. |

| MME | rs2016848 | intronic | 0.45 | Ace Inhibitors, Plain | Allele A is associated with increased risk of Cough when treated with Ace Inhibitors, Plain in people with Hypertension as compared to allele G. |

| MMP3 | rs35068180 | intergenic | 0.49 | pravastatin | Genotypes A/del + AA are associated with increased response to pravastatin in men with Coronary Artery Disease. |

| MTTP | rs1800591 | intronic | 0.25 | atorvastatin | Genotype TT is associated with increased response to atorvastatin in men with Hyperlipoproteinemia Type II. |

| NPC1L1 | rs2072183 | ncRNA | 0.25 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele G is associated with decreased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Cardiovascular Diseases and Hypercholesterolemia as compared to allele C. |

| NT5C2 | rs11191612 | intronic | 0.34 | – | Genotype GG is associated with increased transcription of NT5C2 as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| P2RY12 | rs2046934 | intronic | 0.13 | – | Allele G is associated with increased risk of Coronary Artery Disease and platelet aggregation as compared to allele A, etc. |

| P2RY12 | rs9859552 | intronic | 0.06 | cangrelor | Genotype TT is associated with 20% and 17% less inhibition of platelet aggregation with crangrelor (0.05 and 0.25 microM) in-vitro when exposed to cangrelor as compared to genotype GG. |

| P2RY12 | rs6787801 | intronic | 0.47 | clopidogrel | Allele G is associated with decreased residual on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel in people with Coronary Artery Disease as compared to allele A. |

| P2RY12 | rs3732759 | intronic | 0.32 | clopidogrel | Genotype GG is associated with decreased response to clopidogrel in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| PTGS1 | rs10306135 | 5utr | 0.12 | Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids | Genotype TT is associated with increased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotypes AA + AT. |

| PTGS1 | rs1330344 | intergenic | 0.37 | clopidogrel | Allele T is associated with increased risk of major adverse cardiac events (mace) when treated with clopidogrel as compared to allele C. |

| PTGS1 | rs12353214 | intergenic | 0.15 | Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids | Genotype TT is associated with increased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Antiinflammatory agents, non-steroids in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotypes CC + CT. |

| PTGS2 | rs4648287 | intronic | 0.05 | atenolol | Allele G is associated with increased likelihood of Hypercholesterolemia due to atenolol in people with Hypertension as compared to allele A. |

| PTGS2 | rs4648276 | ncRNA | 0.11 | Coxibs | Genotypes AG + GG are associated with increased likelihood of Acute coronary syndrome when exposed to Coxibs in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to genotype AA. |

| REN | rs11240688 | intronic | 0.24 | hydrochlorothiazide | Genotype GG is associated with increased reduction in SBP when treated with hydrochlorothiazide in people with Essential hypertension as compared to genotypes AA + AG. |

| RHOA | rs11716445 | intronic | 0.03 | pravastatin; simvastatin | Allele A is associated with decreased response to pravastatin or simvastatin in people with Hypercholesterolemia as compared to allele G. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs113681054 | intergenic | 0.22 | ticagrelor | Allele C is associated with increased concentrations of ticagrelor in people with Acute coronary syndrome as compared to allele T. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs4149015 | intronic | 0.05 | pravastatin | Genotype AG is associated with decreased response to pravastatin as compared to genotype GG. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs58310495 | intronic | 0.17 | fluvastatin | Allele T is associated with increased concentrations of fluvastatin in healthy individuals as compared to allele C. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs4363657 | intronic | 0.21 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Genotypes CC + CT are associated with increased likelihood of statin-related myopathy when treated with hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Cardiovascular Diseases as compared to genotype TT. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs11045874 | intronic | 0.21 | rosuvastatin | Allele C is associated with decreased exposure to rosuvastatin in healthy individuals as compared to allele G. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs4149036 | intronic | 0.35 | atorvastatin | Genotypes AC + CC are associated with increased response to atorvastatin as compared to genotype AA. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs4149081 | intronic | 0.22 | simvastatin | Genotype AA is associated with increased LDL-C reduction when treated with simvastatin in people with Coronary Disease as compared to genotypes AG + GG, etc. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs2900478 | intronic | 0.09 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele A is associated with decreased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors as compared to allele T. |

| SLCO1B1 | rs11045854 | ncRNA | 0.02 | rosuvastatin | Allele A is associated with decreased exposure to rosuvastatin in healthy individuals as compared to allele G. |

| SORT1 | rs629301 | 3utr | 0.24 | hmg coa reductase inhibitors | Allele T is associated with decreased response to hmg coa reductase inhibitors in people with Cardiovascular Diseases and Hypercholesterolemia as compared to allele G. |

| VASP | rs10995 | 3utr | 0.22 | hydrochlorothiazide | Genotypes AG + GG are associated with increased response to hydrochlorothiazide in people with Hypertension as compared to genotype AA. |

| VEGFC | rs1002976 | intergenic | 0.42 | uric acid | Allele C is associated with increased concentrations of uric acid in people with Hypertension as compared to allele T. |

MAF refers to minor allele frequency and etc means there is/are additional allelic/genotypic association(s) which is not stated here.

4. Discussion

In industrialized nations, the occurrence of CAD continues to decrease, but owing to population migration and aging, the overall rate of coronary events and, as a result, the incidence of CAD will not decrease, but might even rise in the near future. The prevalence of CAD varies greatly among developing nations. The globalization of the Western diet and increasing sedentary lifestyle will have a profound influence on these nations' gradual growth in the prevalence of CAD. The gradual decline in CAD mortality in industrialized nations over the last few decades may be attributed to both efficient acute-phase therapies and enhanced primary and secondary prevention strategies [7]. Meanwhile, ethnical differences, social inequities, and disparities in the availability of efficient therapies and preventative measures in various regions of the same nation might all have an impact on overall outcomes, necessitating greater investigation and assessment of different locations inside the country [36]. As mentioned before, the findings of single and GWAS studies on CAD are increasingly utilized in personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics strategies of CAD treatment. Thus, this review systematically studied the recent reports from 2020 to 2023 first and then performed a remarkable in silico analysis on a large amount of data. In summary, 5618 articles were found, 1290 papers were eligible, 650 papers were included, 4608 protein-coding genes were extracted, 1432 unique genes distinguished, 530 evidence-based repeated genes remained, among them 71 genes had a pharmacogenetics variant at least (totally 6331 annotations), VAA indicated that 532 variants had potentials to be considered for final report, and lastly, final PGs list according to the deeply matched annotations with CAD revealed 175 variants. According to the function and MAF, 57 structural variants (missense) of 29 PGs remained associated with CAD.

Numerous studies reported the genetic correlations of CAD in both small-sized (single or multiple genes) and GWAS results. Veluchamy et al. (2019) indicated, for example, that among two new genome-wide significant loci relating to the COL4A2 gene for retinal arteriolar tortuosity and gene for retinal venular tortuosity. ACTN4/CAPN12 has been linked to CAD and the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation [37]. Zhao et al. (2018) discovered a significant relationship between variants situated on cytogenetic position 15q26.1 and CAD risk. The potential CAD-related SNP at this locus is found in the FURIN gene's non-coding region. FURIN is primarily produced by macrophages and also is expressed in atherosclerotic plaques, according to a previous study [38]. In another study, Li et al. (2018) discovered three new intragenic SNP that were associated with CAD. Only two of these had transcriptional impacts and were linked with lower expression levels of the SCML4 and THSD7A genes, which are risk alleles and protective alleles, respectively. Employing short interfering RNA to limit translation, they found that knocking down SCML4 boosted the IL-6 levels, E-selectin, and also ICAM, making endothelial cells more susceptible to apoptosis. Additionally, adenovirus-mediated short hairpin RNA suppression of SCML4 resulted in considerably decreased luminal section area compared to controls in a rat study involving partial carotid ligation. Independently, they found that knocking down THSD7A using a short interfering RNA reduced monocyte adhesion by lowering the expression level of ICAM, ITGB2, L-selectin, and in a monocyte/macrophage line [39].

Notably, the current study reviewed the PubMed publications on the topic of “coronary artery disease pharmacogenomics” which showed 29 papers from 2001 to 2023, and the relevant and important reports are summarized here. Kajinami et al. (2005) conducted a review of the Pharmacogenomics of Statin Responsiveness and identified genetic variation at gene loci affecting intestinal cholesterol absorption, including apolipoprotein (APO) E; adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter G5 and G8; cholesterol production, like as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase; and lipoprotein catabolism, such However, there is a significant variation in the findings reported, and the data recommended that merged analysis of multiple genetic variants in several genes, all of which have potential functional relevance, is more probable to yield significant findings than single gene studies in small sample groups [40]. Tsikouris and Peeters (2007) reviewed the existing Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) inhibitor pharmacogenomic investigations that have assessed RAS variants that either reveal mechanisms through surrogate outcome measures or predict effectiveness through clinical results in CAD-related disorders. Despite the outcome, none of the RAS genotypes predicts RAS inhibitor effectiveness decisively [41]. Inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics has been demonstrated to alter the clinical result of long-term coronary artery disease therapy, according to Remmler and Cascorbi (2008). They highlighted the effects of Plasminogen activator inhibitor type I (PAI-I), Fibrinogen, ACE, eNOS, APOB, APOE, APO-AV, APO-CIII, Lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase (LIPC), OLR1, CETP, OATP1B1, CYP2C9, ADRB1, ADRB2, ADR2AC, and VKORC1 [42]. According to Ellis et al. (2009), clopidogrel antiplatelet treatment is the standard care for CAD patients having percutaneous coronary intervention. Yet, about 25% of individuals have a subtherapeutic antiplatelet response. Clopidogrel is a prodrug which is biotransformed into its active metabolite by CYP2C19 in the liver. Numerous investigations have found that, when compared to wild-type individuals, CYP2C19 variant allele carriers have a considerably reduced capacity to convert clopidogrel to its active metabolite and reduce platelet activation, putting them at a significantly greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events [43]. Homeyer and Schwinn (2011) investigated the Pharmacogenomics of -Adrenergic Receptor Physiology and Response to -Blockade and found two clinically significant SNPs for the 1AR (Ser49Gly, Arg389Gly), three for the β2AR (Arg16Gly, Gln27Glu, Thr164Ile), and one for the β3AR (Trp64Arg). They stated that, whereas AR SNPs may not directly cause disease, they do appear to be risk factors for the condition as well as regulators of disease and response to stress and medications. This has been observed especially in the perioperative context for the Arg389Gly β1AR polymorphism, with individuals with the Gly variation having a greater frequency of unfavorable perioperative outcomes [44]. Luchessi et al. (2013) discovered that the difference in response to Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) may be associated with an elevated level of IGF1 and IGF1R, as well as a response to clopidogrel can be influenced by pharmacokinetic changes corresponding to the reverse transport pathway via raised expression of ABCC3 [45]. The most consistent findings in a study by Yasmina et al. (2014) included clopidogrel, where CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles were connected to stent thrombosis occurrences. In patients with CAD having percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting, they advise genotyping for CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles and modifying the antiplatelet regimen depending on the genotyping outcomes [46]. Ssaydam et al. (2017) aimed to identify the most notable mutations in the genes implicated in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel. Their study comprised 347 Turkish patients who underwent percutaneous coronary procedures with stent insertion. Genotyping was performed on variations in the CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP2B6, ABCB1, ITGB3, and PON1 genes. The CYP2C19*2 (G636A) polymorphism was shown to be associated with non-responsiveness to clopidogrel medication (p < 0.001). In non-responders, the allele frequency of this SNP was substantial; its odds ratio was 2.92 compared to the G allele (p < 0.001). Their results revealed that the CYP2C19*2 polymorphism is related to non-responsiveness to clopidogrel treatment, whereas the CYP2C19*17 polymorphism increases clopidogrel's antiplatelet action. Clopidogrel-treated individuals can be protected or not against stent thrombosis and ischemic events based on the haplotypes of these two SNPs [47]. Fragoulakis et al. (2019) compared pharmacogenomics-guided clopidogrel medication to non-pharmacogenomics-guided clopidogrel treatment for coronary artery syndrome subjects having percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the Spanish healthcare context. A total of 549 individuals with CAD who had PCI were selected. Their findings showed that a pharmacogenomics-guided clopidogrel therapy might be a more cost-effective option for patients undergoing PCI than a non-pharmacogenomics-guided procedure [48]. Verma et al. (2020) used samples from 2750 European people to conduct a GWAS. GWAS for platelet reactivity indicated a significant signal for CYP2C19*2 (P value = 1.67e33), and mutations in SCOS5P1, CDC42BPA, and CTRAC1 proved genome-wide significance in the CAD, percutaneous coronary intervention, and acute coronary syndrome subgroups (lowest P values: 1.07e-09, 4.53e-08, and 2.60e-10, respectively). They concluded that CYP2C19*2 is the most powerful genetic factor of on-clopidogrel platelet responsiveness [49]. In their narrative review (2021), Hirata et al. examined pharmacogenomic research on antithrombotic medications routinely administered in Brazil. Few pharmacogenomics studies have looked at antiplatelet drugs in Brazilian cohorts, and they discovered relationships between CYP2C19*2, PON1 rs662, and ABCC3 rs757421 genotypes and platelet responsiveness or clopidogrel pharmacokinetic (PK) in participants suffered from CAD or acute coronary syndrome (ACS), whereas ITGB3 contributes to aspirin PK but not platelet responsiveness in diabetic individuals. Brazilian anticoagulant and antiplatelet guidelines recommended using a platelet aggregation evaluation or genotyping only in determined cases of ACS individuals taking clopidogrel who do not have ST-segment elevation, and they additionally suggested CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotyping before establishing warfarin therapy to evaluate the risk of bleeding incidents or warfarin resistance [50].

Statin medications have been utilized for years in the main and second-line prevention of CAD due to their ability to decrease cholesterol. According to recent studies, the positive benefits of statins expand over their lipid-lowering impacts and may potentially protect against atherosclerosis through lipid-lowering unrelated pathways [51,52]. Yu and his colleagues demonstrated that rosuvastatin treatment reduced coronary artery atherosclerosis, platelet accumulation in atherosclerotic coronary arteries, cardiomegaly, and cardiac fibrosis in a mouse model that spontaneously had coronary artery atherosclerosis. Regardless of rising plasma cholesterol levels, these beneficial effects included a reduction in accumulated oxidized phospholipids in damaged artery walls as well as a reduction in macrophage foaming production [53]. The endothelium has a remarkable impact on healing wounds and serves such a barrier to regulate the transportation of leukocytes. The endothelium is essential for wound healing and works as a barrier to limit leukocyte transportation [54,55]. The modification of endothelial function, which is critical to wound healing and as a barrier in the atherosclerotic progression, is a key role of statin medicines. In atherosclerosis before MI, endothelial barrier function is compromised. After MI, Leenders et al. looked at how statins affected the function of the endothelium barrier in atherosclerotic ApoE-deficient mice. Statin treatment reduced infarcted tissue porosity and the entry of undesirable inflammatory leukocytes. On day 21 after an MI, hearts treated with statins performed better as a result of this. After MI, statin treatment improved the infarct endothelial barrier's performance and prevented the progression of scarring. This study demonstrated the importance of statin therapy for infarct repair after MI [56].

Human genetics has been extensively employed in recent years to determine causal relationships of hypothesized biomarkers or drug targets. Mendelian randomization (MR) studies utilize genetic variations to assess the causation of a disease's hypothesized risk variables [57]. If genetic variations have no further instant impact other than modulating a risk factor (for example LDL cholesterol) and also show a connection with downstream characteristics (for instance CAD), that second condition is most likely initiated with the risk factor (LDL-C), demonstrating a causal link between the risk factor and CAD [[58], [59], [60], [61], [62]]. As a result of its independence from confusion, MR research goes beyond standard epidemiological studies in determining causality [63]. Several conventional CAD risk factors, including triglycerides, LDL-C, LP(a), obesity, blood pressure, alcohol consumption, smoking, and T2D, are strengthened by MR. MR validated the presence of multiple causative risk factors, particularly APOC3, IL-1, IL6, insulin resistance, height, non-fasting glucose, telomere length, HMGCR, and Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) [23]. Additionally, MR can assess the impact of drugs in a tailored setting. As an instance, Ference et al. used MR to analyze the impact of LDL-C reduction on the CAD risk caused by variants in NPC1L1 (ezetimibe target), HMGCR (statins target), or both (combinational treatment with ezetimibe and a statin) [64]. Furthermore, MR studies may expedite the lengthy process of obtaining FDA approval for a drug. MR investigations can reveal if drug targets are causal and how they are modulated with side effects. MR investigations are affordable, quick, and straightforward to conduct. Indeed, MR studies may be more precise than randomized controlled trials and are thus advised for therapeutic targets before moving to clinical trials [23].

Interestingly, PPI and GMI (Fig. 3, Fig. 4) showed a common miRNA, hsa-miR-33a. Interestingly, Reddy et al., in 2019 demonstrated a significant relationship between amplified amounts of plasma miR-33 and CAD and concluded that plasma miR-33 seems to have a noticeable non-invasive biomarker role [65]. The findings of the current in silico analysis revealed strong associations of hsa-miR-33a with ABCA1 gene variants (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3) in all three categories including missense variants (rs2230806, rs2230808), regulatory variant (rs2487032 as enhancer), and non-coding variants (rs12003906, rs2472507, rs2515629, and rs4149297). Genotype TT of rs2230806 is associated with increased HDL-cholesterol when treated with pravastatin in people with CAD as compared to genotype CC. Genotype CC of rs2230808 is associated with increased response to fenofibrate in people with Hypertriglyceridemia as compared to genotype TT. Genotype AA and AG of rs2487032 is associated with increased metabolism of clopidogrel as compared to genotype GG. Allele C of rs12003906 is associated with decreased response to atorvastatin, pravastatin, or simvastatin in people with Hyperlipidemias as compared to allele G. Allele C, G, and G of rs2472507, rs2515629, and rs4149297, respectively are associated with increased expression of ABCA1 in HapMap cells. Moreover, Dong et al.‘s study confirmed the increased expression levels of miR-24, miR-33a, miR-103a, and miR-122 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with the incidence of CAD [66]. Among these miRNAs, hsa-miR-101 was in the center of the concentric GMI model represented in Fig. 3 which displayed 4 connections with PTGS2, CCND1, RHOA, and VEGFC.

As an important role of the mentioned drugs in the current study, the clinical trial status of these drugs with CAD is highly remarkable for drug prescribing based on patients’ genotypes. ABCA1 (rs2230806) with Pravastatin, ABCB1 (rs2032582 and rs1045642) and (rs1128503) with Simvastatin, ALDH2 (rs671) with Nitroglycerin, APOC1 (rs429358 and rs7412) with Warfarin, APOE (rs429358 and rs7412) with Warfarin, CES1 (rs146456965, rs202001817, rs71647871, rs201065375, rs2307240, rs143718310, rs200707504, and rs151291296) with Clopidogrel, CETP (rs5882) with Simvastatin, F7 (rs6046) with Warfarin, FMO3 (rs1736557) with Clopidogrel, ITGB3 (rs5918) with Aspirin, LEPR (rs1805094) with Atorvastatin and (rs1137101) with Simvastatin, LPA (rs3798220) with Aspirin, P2RY12 (rs6785930 and rs6809699) with Clopidogrel, PCSK9 (rs11591147) with Atorvastatin, PON1 (rs662) with Simvastatin, SCARB1 (rs4238001) with Fenofibrate and rs5888 with Atorvastatin, SH2B3 (rs3184504) with Candesartan, SLCO1B1 (rs4149056) with Simvastatin and (rs11045819) with Fluvastatin and (rs34671512) with Rosuvastatin and (rs2306283) with Atorvastatin, TLR4 (rs4986790) with Pravastatin, EDN1 (rs5370) with Atenolol, and NOS3 (rs1799983) with Aspirin and Clopidogrel. These drugs are highly recommended for personalized medicine-based prescribing according to the genotyping of the 36 aforementioned variants. Compared to these genes, 11 genes have unknown clinical trials including ABCG8, AGT, APOB, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, FABP1, KDR, NPPA, NR3C2, NT5C2, and PTGS1 which are highly suggested for future clinical trials of investigating the related drugs with CAD. Some of these genes had limited studies with pharmacology of CAD including ALDH2 [67], APOC1 ([68]), FMO3 [69], LEPR [70], P2RY12 [71], SCARB1 [72], SH2B3 [73], SLCO1B1 [74], TLR4 [75], EDN1 [76], NOS3 [77], ABCG8 [78], AGT [79], FABP1 [80], KDR [81], NPPA [82], NR3C2 [83], NT5C2 [84], and PTGS1 [85].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, GWAS and post-GWAS research on CAD has made significant advances toward comprehending the genetic framework of this complicated disease. In addition to identifying potential genes, these investigations aided drug development and enhanced disease risk assessment, in addition to preventative treatments. GWAS might lay the basis for CAD personalized medicine. Surprisingly, applications of post-GWAS will be strengthened by the incorporation of more OMIC data, plus personal and environmental impacts to provide a comprehensive understanding of this complicated disease, perhaps leading to the discovery of the missing heritability. To combine and comprehend such vast amounts of data, artificial intelligence, and deep learning algorithms will be essential. Based on the PPI, GMI, PDI, and VVA results and Reddy et al.‘s study, by evaluation of circulating miR33a in the plasma of individuals with CAD, and genotyping of pharmacogenomiclly actionable variants of ABCA1 gene including rs2230806, rs2230808, rs2487032, rs12003906, rs2472507, rs2515629, and rs4149297, precise prescriptions of CAD well-know drugs will be applicable. Altogether, the findings of this report can improve the importance of pharmacogenomics utilization in CAD for personalized treatment and candidate gene panel of PGx-CAD in WES and WGS analysis.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Data availability

There is no data availability to state.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Siamak Kazemi Asl: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Milad Rahimzadegan: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alireza Kazemi Asl: Visualization, Validation, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful of all database owners and all omics developers.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28983.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Vedanthan R., Seligman B., Fuster V. Global perspective on acute coronary syndrome: a burden on the young and poor. Circ. Res. 2014;114(12):1959–1975. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowbar A.N., et al. 2014 global geographic analysis of mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, age and income: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;174(2):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran A.E., et al. Assessing the global burden of ischemic heart disease: part 1: methods for a systematic review of the global epidemiology of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010. Global heart. 2012;7(4):315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forouzanfar M.H., et al. Assessing the global burden of ischemic heart disease: part 2: analytic methods and estimates of the global epidemiology of ischemic heart disease in 2010. Global heart. 2012;7(4):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ounpuu S., Yusuf S. Oxford University Press; 2003. Singapore and Coronary Heart Disease: a Population Laboratory to Explore Ethnic Variations in the Epidemiologic Transition; pp. 127–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang G., et al. Burden of Ischaemic heart disease and attributable risk factors in China from 1990 to 2015: findings from the global burden of disease 2015 study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018;18:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0761-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira-González I. The epidemiology of coronary heart disease. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2014;67(2):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuf S., et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001;104(23):2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viera A.J., Sheridan S.L. Global risk of coronary heart disease: assessment and application. Am. Fam. Physician. 2010;82(3):265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]