Key Points

Question

Is rechallenge with anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors a therapeutic option in patients with refractory circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) RAS/BRAF wild-type (wt) colorectal cancer (CRC)?

Findings

This nonrandomized controlled trial used a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 114 patients with ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt metastatic CRC receiving anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy in 4 prospective, phase 2 Italian trials. The treatment strategy was associated with tumor shrinkage, a high rate of disease control, and promising progression-free and overall survival, with a significant improvement in patients without liver involvement.

Meaning

These findings suggest that rechallenge with anti-EGFR inhibitors has promising antitumor activity in patients with refractory ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt metastatic CRC.

This nonrandomized controlled trial evaluates anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) rechallenge therapy in patients in Italy with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) RAS/BRAF wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer.

Abstract

Importance

The available evidence regarding anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor rechallenge in patients with refractory circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) RAS/BRAF wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is derived from small retrospective and prospective studies.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of anti-EGFR rechallenge in patients with refractory ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt mCRC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nonrandomized controlled trial used a pooled analysis of individual patient data from patients with RAS/BRAF wt ctDNA mCRC enrolled in 4 Italian trials (CAVE, VELO, CRICKET, and CHRONOS) and treated with anti-EGFR rechallenge between 2015 and 2022 (median [IQR] follow-up, 28.1 [25.8-35.0] months).

Intervention

Patients received anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy, including cetuximab plus avelumab, trifluridine-tipiracil plus panitumumab, irinotecan plus cetuximab, or panitumumab monotherapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), overall response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR) were calculated. Exploratory subgroup analysis evaluating several clinical variables was performed. Safety was reported.

Results

Overall, 114 patients with RAS/BRAF wt ctDNA mCRC (median [IQR] age, 61 [29-88] years; 66 men [57.9%]) who received anti-EGFR rechallenge as experimental therapy (48 received cetuximab plus avelumab, 26 received trifluridine-tipiracil plus panitumumab, 13 received irinotecan plus cetuximab, and 27 received panitumumab monotherapy) were included in the current analysis. Eighty-three patients (72.8%) had received 2 previous lines of therapy, and 31 patients (27.2%) had received 3 or more previous lines of therapy. The ORR was 17.5% (20 patients), and the DCR was 72.3% (82 patients). The median PFS was 4.0 months (95% CI, 3.2-4.7 months), and the median OS was 13.1 months (95% CI, 9.5-16.7 months). The subgroup of patients without liver involvement had better clinical outcomes. The median PFS was 5.7 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.7 months) in patients without liver metastasis compared with 3.6 months (95% CI, 3.3-3.9 months) in patients with liver metastasis (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.37-0.83; P = .004). The median OS was 17.7 months (95% CI, 13-22.4 months) in patients without liver metastasis compared with 11.5 months (95% CI, 9.3-13.9 months) in patients with liver metastasis (hazard ratio, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.97; P = .04). Treatments showed manageable toxic effects.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy has promising antitumor activity in patients with refractory ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt mCRC. Within the limitation of a subgroup analysis, the absence of liver metastases was associated with significant improved survival.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02296203; NCT04561336; NCT03227926; NCT05468892

Introduction

Treatment with anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in combination with chemotherapy is a standard of care as first-line treatment for patients with RAS/BRAF wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).1 Despite an initial antitumor activity with high overall response rate (ORR), disease progression almost inevitably occurs as a result of cancer cells acquiring resistance.2,3

It is well known that the most frequent resistance alterations are associated with the EGFR signaling cascade, such as the EGFR extracellular domain (ECD) or alterations in downstream effectors like KRAS/NRAS and BRAF. Nevertheless, the spectrum of the molecular alterations may change over time depending on the treatment received. By use of serial liquid biopsy of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) status, it has been shown that RAS/BRAF/EGFR ECD alteration cancer cell clones have a half-life of approximately 4 months.4,5 Therefore, after disease progression, during a so-called anti-EGFR therapeutic holiday, resistant clones might decay, thereby potentially restoring sensitivity to EGFR blockade.3,4,5 Consequently, over the last decade, different groups have investigated the role of anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy in patients with refractory RAS wt mCRC.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 The main clinical criteria for patient selection in these trials were receiving an anti-EGFR–based therapy, experiencing a clinical benefit followed by progressive disease, and then receiving a subsequent EGFR-free treatment. In an unselected population with refractory disease, the combination of chemotherapy with anti-EGFR rechallenge was associated with heterogenous responses, with an ORR ranging from 0% to 54%.

Translational retrospective analyses of these studies showed that patients with RAS/BRAF wt ctDNA showed the highest clinical benefit from this treatment.9,10,11,13,14,15 To date, the CHRONOS (Rechallenge With Panitumumab Driven by RAS Dynamic of Resistance) trial, in which patients with RAS/BRAF wt mCRC with received panitumumab rechallenge, is the only study that prospectively used liquid biopsy for patient selection.12

Despite the strong rationale, the quality of the available evidence on the role of anti-EGFR rechallenge in ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt tumors is poor, because it has been mainly derived via post hoc analysis performed with limited numbers of patients. Consequently, caution is required when interpreting these results, and further validation is needed. Moreover, in a molecularly selected population, the identification of other variables potentially associated with clinical activity represents an unmet need.

To fill this gap, we conducted a pooled analysis of individual patient data (IPD) from 4 prospective phase 2 trials. Only patients with ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt tumors confirmed by liquid biopsy at baseline were included. Finally, exploratory subgroup analyses were performed to identify further potential biomarkers.

Methods

Study Population

In this nonrandomized controlled trial, we conducted a pooled analysis of IPD from 4 multicenter, phase 2 studies: CRICKET (Cetuximab Rechallenge in Irinotecan-pretreated mCRC, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Wild-type Treated in 1st Line With Anti-EGFR Therapy), CAVE (Avelumab Plus Cetuximab in Pre-treated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer), CHRONOS, and VELO (Phase II Randomized Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Panitumumab [Vectibix] and Trifluridine-Tipiracil [Lonsurf] in Pretreated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients) trials. Patients who received rechallenge with EGFR inhibitors and exhibited RAS/BRAF wt ctDNA tumors at baseline were included.

The 4 studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki17 and were approved by the ethical committees of all participating centers. Patients provided written informed consent for trial participation. This study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations With Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guideline.

The CRICKET study was a single-group phase 2 trial that investigated rechallenge with cetuximab plus irinotecan as third-line treatment in patients with RAS/BRAF wt mCRC.9 The study provided the first prospective evidence of rechallenge therapy in refractory mCRC. Post hoc analysis showed that confirmed responses were observed only in patients without resistance alterations detected at liquid biopsy analysis. The CAVE trial was a single-group, multicenter, phase 2 study that evaluated rechallenge with cetuximab plus the anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 mAbs avelumab in patients with heavily pretreated RAS wt mCRC.11 The study met its primary end point, and an increase in survival of more than 3 months compared with historical controls was reported. The CHRONOS study was the first trial that prospectively selected patients amenable for rechallenge therapy with panitumumab on the basis of the results of liquid biopsy using highly sensitive digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) to detect RAS/BRAF/EGFR ECD alterations in the plasma.12 The trial was positive, with an ORR of 30%. The VELO trial was a randomized phase 2 study that compared rechallenge with panitumumab plus trifluridine-tipiracil vs trifluridine-tipiracil as third-line treatment in RAS wt mCRC.13,14 The trial reached its primary end point, demonstrating a significant increase in progression-free survival (PFS) of the experimental group compared with the standard of care. The full study protocols with inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published9,11,12,13,14 and are shown in Supplement 1.

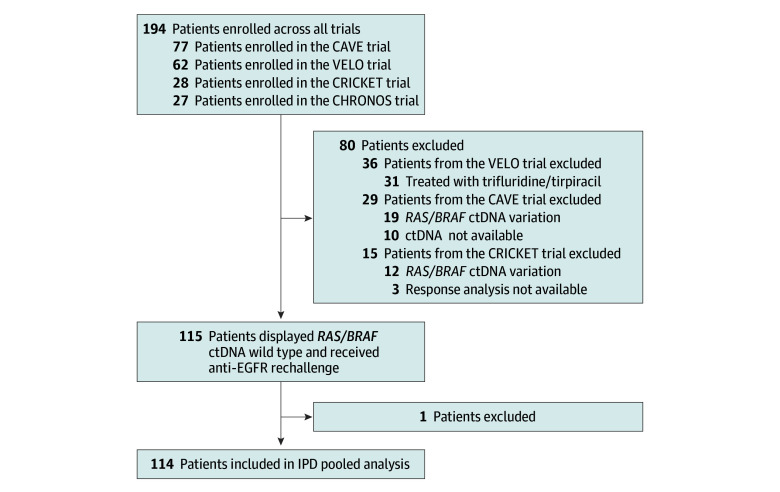

The procedure for patient selection is displayed in Figure 1. Among the 194 patients enrolled in the 4 trials, 80 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria (ie, having received an anti-EGFR rechallenge treatment with baseline RAS/BRAF alteration ctDNA at liquid biopsy analysis) and were excluded. In the group of patients not eligible for the current analysis, 15 were from the CRICKET trial (3 were not evaluable for tumor response, and 12 showed RAS/BRAF alteration ctDNA), 29 from the CAVE trial (10 did not have available baseline plasma samples, and 19 displayed RAS/BRAF alteration ctDNA), and 36 from the VELO trial (31 did not receive anti-EGFR rechallenge, and 5 exhibited RAS/BRAF alteration ctDNA). To facilitate data gathering and analysis, a study data set including key information from the 4 trials was set up. The following data were extrapolated from each trial: age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, primary tumor sidedness, resection of primary tumor, microsatellite status, number of previous lines of treatment, type of anti-EGFR treatment received as first-line or second-line therapy, number of metastatic sites, metastasis location (liver, lung, peritoneum, and lymph nodes), carcinoembryonic antigen levels, treatment efficacy (ORR, PFS, and overall survival [OS]), and toxic effects.

Figure 1. Patient Enrollment Flowchart.

CAVE indicates Avelumab Plus Cetuximab in Pre-treated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer; CHRONOS, Rechallenge With Panitumumab Driven by RAS Dynamic of Resistance; CRICKET, Cetuximab Rechallenge in Irinotecan-pretreated mCRC, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Wild-type Treated in 1st Line With Anti-EGFR Therapy; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; IPD, individual patient data; VELO, Phase II Randomized Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Panitumumab (Vectibix) and Trifluridine-Tipiracil (Lonsurf) in Pretreated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients.

Efficacy and Safety of the Treatments

The ORR was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved complete or partial response during treatment according to RECIST version 1.1.18 PFS was defined as the time from the initiation of study treatment to disease progression or death. OS was determined as the time from the beginning of the experimental therapy to death. In the absence of events, PFS and OS were censored at the time of last follow-up.

Tumor measurements were done at baseline and were repeated every 8 weeks in the CRICKET, CHRONOS, and VELO studies. In the CAVE trial, tumor measurements were performed at baseline, and every 8 weeks for the first 40 weeks and subsequently every 12 weeks. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 for CRICKET, version 4.03 for CAVE and CHRONOS, and version 5.0 for VELO studies.19

Molecular Analysis

In the CRICKET study, baseline plasma samples were available for 25 patients and were analyzed using the next-generation sequencing Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel (Thermo Fisher).7 For the CAVE trial, pretreatment plasma samples were collected for 67 patients and were analyzed using a reverse transcriptase–PCR test (IdyllaTM Biocartis platform).11,20 In the CHRONOS trial, baseline liquid biopsy analysis was performed during the screening procedures. Overall, ctDNA from 52 patients was assessed using a ddPCR-based assay (Bio-Rad) for the identification of the most frequent KRAS, BRAF, and EGFR ECD alterations. Finally, for the 31 patients enrolled in the VELO trial who received rechallenge therapy, ctDNA was retrospectively evaluated using the IdyllaTM Biocartis assay.13,14,20

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize clinical and pathological outcomes. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate PFS and OS. The subgroup exploratory analyses were conducted by using the Cox hazard ratio (HR) regression model. Comparison of treatment efficacy in the patient subgroups with or without liver metastases was performed with the log-rank test for PFS and OS. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 23.0 (IBM). The threshold for statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Overall, 114 patients (median [IQR] age, 61 [29-88] years; 66 men [57.9%]) met the specified criteria and were included in the pooled data set: 13 patients from the CRICKET trial received irinotecan plus cetuximab, 48 patients from the CAVE trial received cetuximab plus avelumab, 27 patients from the CHRONOS trial received panitumumab monotherapy, and 26 patients from the VELO trial received trifluridine-tipiracil plus panitumumab. Baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are detailed in Table 1. Eighty-three patients (72.8%) received 2 previous lines of therapy, and 31 (27.2%) patients received 3 or more anticancer treatments. In total, 36 patients (31.6%) had 3 or more different metastatic sites. Liver was the most frequent metastatic site (72 patients [63.2%]), followed by lung (63 patients [55.3%]), lymph nodes (47 patients [41.2%]), and peritoneum (26 patients [22.8%]). Increased carcinoembryonic antigen levels (>5 ng/mL; to convert to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0) were reported in 76 patients (66.7%). The type of previous anti-EGFR treatment was balanced in the study population; 57 patients (50.0%) received cetuximab, 56 patients (49.0%) received panitumumab, and 1 patient (0.9%) received both drugs.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Receiving Anti-EGFR Challenge Therapy in 4 Italian Trials.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRICKET (n = 13) | CAVE (n = 48) | VELO (n = 26) | CHRONOS (n = 27) | Pooled analysis (N = 114) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 4 (30.8) | 23 (47.9) | 10 (38.5) | 11 (40.7) | 48 (42.1) |

| Male | 9 (69.2) | 25 (52.1) | 16 (61.5) | 16 (59.3) | 66 (57.9) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 68 (45-86) | 60 (30-88) | 63 (39-81) | 59 (29-78) | 61 (29-88) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status | |||||

| 0 | 10 (76.9) | 34 (70.8) | 18 (69.2) | 14 (51.9) | 76 (66.7) |

| 1 | 2 (15.4) | 14 (29.2) | 8 (30.8) | 12 (44.4) | 36 (31.6) |

| 2 | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 2 (1.8) |

| Tumor sidedness | |||||

| Right rectum | 3 (23.1) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.8) | 5 (18.5) | 10 (8.8) |

| Left rectum | 10 (76.9) | 47 (97.9) | 25 (96.2) | 22 (81.5) | 104 (91.2) |

| Resection of primary tumor | |||||

| No | 1 (7.7) | 16 (33.3) | 4 (15.4) | 2 (7.2) | 23 (20.2) |

| Yes | 12 (92.3) | 32 (66.7) | 22 (84.6) | 25 (92.6) | 91 (79.8) |

| Microsatellite status | |||||

| Microsatellite stable | 0 | 44 (91.7) | 12 (46.2) | 27 (100.0) | 83 (72.8) |

| Microsatellite instable | 0 | 2 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| NA | 13 (100.0) | 2 (4.2) | 13 (50) | 0 | 28 (24.6) |

| No. of previous lines of treatment | |||||

| 2 | 13 (100.0) | 33 (68.8) | 26 (100.0) | 11 (40.7) | 83 (72.8) |

| ≥3 | 0 | 15 (31.3) | 0 | 16 (59.3) | 31 (27.2) |

| Previous anti-EGFR treatment | |||||

| Panitumumab | 0 | 25 (52.1) | 17 (65.4) | 15 (55.6) | 57 (50.0) |

| Cetuximab | 13 (100.0) | 23 (47.9) | 9 (34.6) | 11 (40.7) | 56 (49.1) |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| No. of metastatic sites | |||||

| ≤2 | 8 (61.5) | 32 (66.7) | 20 (76.9) | 18 (66.7) | 78 (68.4) |

| >2 | 5 (38.5) | 16 (33.3) | 6 (23.1) | 9 (33.3) | 36 (31.6) |

| Liver metastasis | |||||

| No | 3 (23.1) | 18 (37.5) | 10 (38.5) | 11 (40.7) | 42 (36.8) |

| Yes | 10 (76.9) | 30 (62.5) | 16 (61.5) | 16 (59.3) | 72 (63.2) |

| Lung metastasis | |||||

| No | 8 (61.5) | 16 (33.3) | 13 (50.0) | 14 (51.9) | 51 (44.7) |

| Yes | 5 (38.5) | 32 (66.7) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | 63 (55.3) |

| Peritoneal metastasis | |||||

| No | 9 (69.2) | 36 (75.0) | 21 (80.8) | 22 (81.5) | 88 (77.2) |

| Yes | 4 (30.8) | 12 (25.0) | 5 (19.2) | 5 (18.5) | 26 (22.8) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||

| No | 7 (53.8) | 29 (60.4) | 21 (80.8) | 10 (37.0) | 67 (58.8) |

| Yes | 6 (46.2) | 19 (39.6) | 5 (19.2) | 17 (63.0) | 47 (41.2) |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen level | |||||

| <5 ng/mL | 1 (7.7) | 7 (14.6) | 3 (11.5) | 5 (18.5) | 16 (14.0) |

| ≥5 ng/mL | 11 (84.6) | 24 (50.0) | 20 (76.9) | 21 (77.8) | 76 (66.7) |

| NA | 1 (7.7) | 17 (35.4) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (3.7) | 22 (19.3) |

Abbreviations: CAVE, Avelumab Plus Cetuximab in Pre-treated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer; CHRONOS, Rechallenge With Panitumumab Driven by RAS Dynamic of Resistance; CRICKET, Cetuximab Rechallenge in Irinotecan-pretreated mCRC, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Wild-type Treated in 1st Line With Anti-EGFR Therapy; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NA, not available; VELO, Phase II Randomized Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Panitumumab (Vectibix) and Trifluridine-Tipiracil (Lonsurf) in Pretreated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients.

SI conversion factor: To convert carcinoembryonic antigen to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Efficacy and Safety Analysis

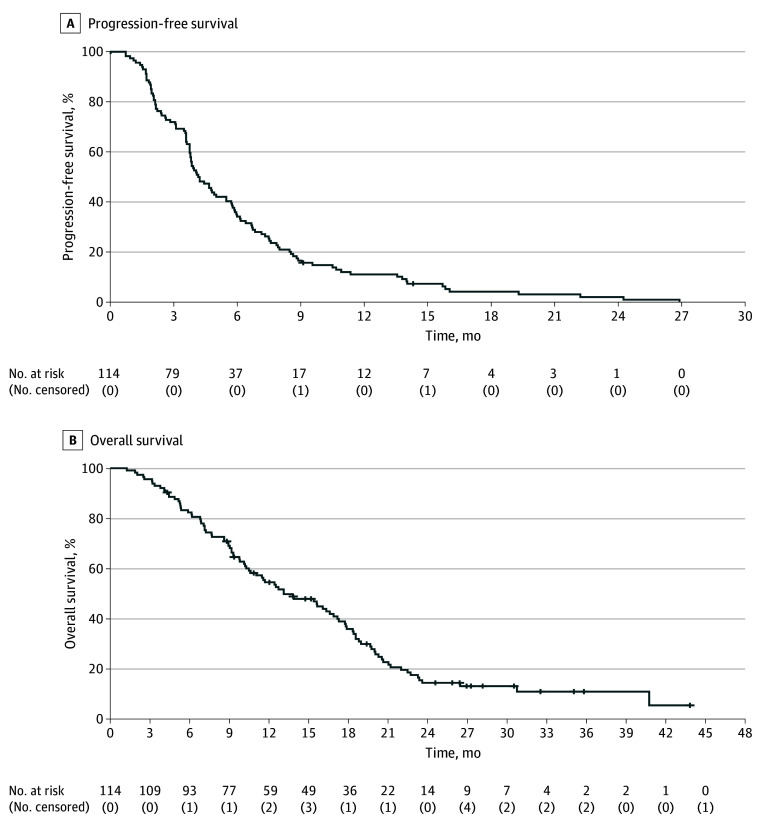

The median (IQR) follow-up was 28.1 (25.8-35.0) months. The ORR in the pooled population was 17.5% (20 patients), with 1 patient who achieved complete response and 19 patients who achieved partial response (Table 2). Stable disease was observed in 65 patients (57.0%). The DCR was 72.3% (82 patients). The median PFS was 4.0 months (95% CI, 3.2-4.7 months), and the median OS was 13.1 months (95% CI, 9.5-16.7 months) in the study population overall (Figure 2). Of note, a subset of patients experienced prolonged disease control upon anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy, with a 6-month PFS rate of 32.5% that led to an 18-month OS rate of 36.0% (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Tumor Response of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Receiving Anti–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Challenge Therapy in 4 Italian Trials.

| Study | Patients, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response | Partial response | Stable disease | Progressive disease | Overall response rate | Disease control rate | |

| CAVE (n = 48) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (6.25) | 31 (64.5) | 13 (27.1) | 4 (8.3) | 35 (73.0) |

| VELO (n = 26) | 0 | 3 (11.5) | 18 (69.2) | 5 (19.2) | 3 (11.5) | 21 (81.0) |

| CRICKET (n = 13) | 0 | 5 (38.5) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (38.5) | 10 (77.0) |

| CHRONOS (n = 27) | 0 | 8 (30.0) | 8 (30.0) | 11 (41.0) | 8 (30.0) | 16 (59.3) |

| Pooled analysis (N = 114) | 1 (0.9) | 19 (16.7) | 65 (57.0) | 32 (28.0) | 20 (17.5) | 82 (72.3) |

Abbreviations: CAVE, Avelumab Plus Cetuximab in Pre-treated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer; CHRONOS, Rechallenge With Panitumumab Driven by RAS Dynamic of Resistance; CRICKET, Cetuximab Rechallenge in Irinotecan-pretreated mCRC, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Wild-type Treated in 1st Line With Anti-EGFR Therapy; VELO, Phase II Randomized Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Panitumumab (Vectibix) and Trifluridine-Tipiracil (Lonsurf) in Pretreated RAS Wild Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for All Patients.

Graphs show progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B). The median progression-free survival was 4.0 months (95% CI, 3.2-4.7 months), and the median OS was 13.1 months (95% CI, 9.5-16.7 months). Numbers in parentheses denote censored patients.

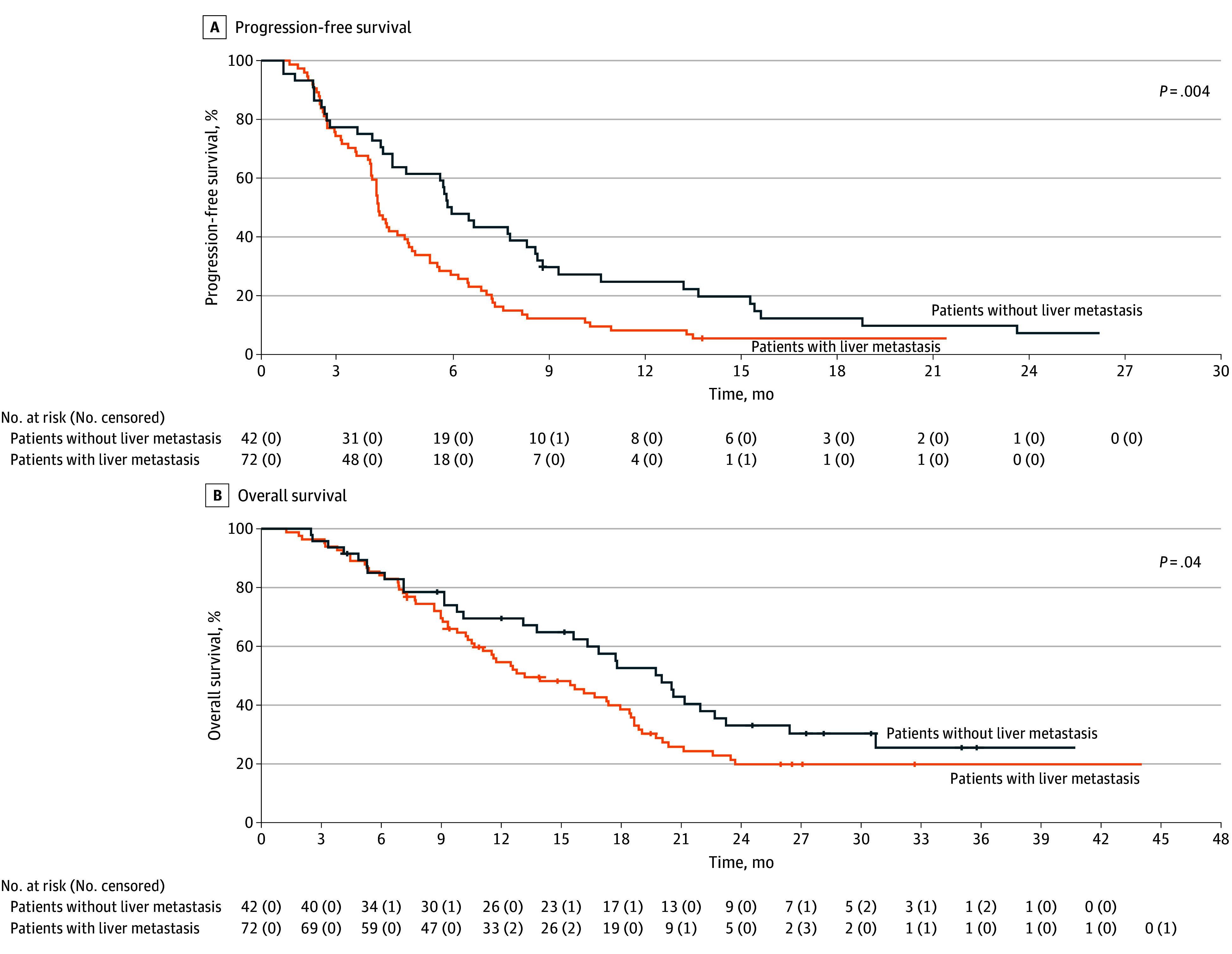

Subsequently, we conducted an exploratory subgroup analysis to evaluate the association of several clinical variables (including performance status, number of previous line of treatments, tumor burden, resection of primary tumor, primary tumor sidedness, location of metastatic sites, and carcinoembryonic antigen) with treatment outcomes (eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). The absence of liver metastases was the only variable associated with improved PFS and OS. In the subgroup of patients without liver metastasis, the median PFS was 5.7 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.7 months) compared with 3.6 months (95% CI, 3.3-3.9 months) in patients with liver metastases (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.37-0.83; P = .004) (Figure 3A). The median OS was 17.7 months (95% CI, 13-22.4 months) in patients without liver metastases compared with 11.5 months (95%, CI 9.3-13.9 months) in patients with liver metastases (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.97; P = .04) (Figure 3B). Finally, in patients without liver involvement, the 12-month PFS rate was 21.0%, whereas the 30-month OS rate was 21.6% (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves According to the Presence of Liver Metastasis.

Graphs show progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B). The median progression-free survival was 5.7 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.7 months) for patients without liver metastasis and 3.6 months (95% CI, 3.3-3.9 months) for patients with liver metastasis (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.37-0.83). The median overall survival was 17.7 months (95% CI, 13.0-22.4 months) for patients without liver metastasis and 11.5 months (95% CI, 9.3-13.9 months) for patients with liver metastasis (hazard ratio, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.97). Numbers in parentheses denote censored patients.

The safety profiles of the pooled analysis of the 4 clinical trials were in line with previous findings and were manageable (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Skin rash (grade 3-4, 24 patients [21%]) and diarrhea (grade 3-4, 9 patients [8%]) were the most frequent adverse events related to the use of anti-EGFR mAbs. Grade 3 to 4 neutropenia was observed in 19 patients (17%), only among the 39 patients who received a backbone chemotherapy.

Discussion

Over the last 2 decades, the identification of the molecular factors underlying disease and the clinical development of more effective treatments have led to substantial improvement in the treatment of patients with mCRC.21 Now, after progression to first-line and second-line therapies, more than one-half of patients maintain good performance status and are amenable to receiving further therapies.22,23

In the continuum of care for mCRC, even in later lines of treatment, fluoropyrimidine-based therapies and the blockade of angiogenesis are the main therapeutic choices.24,25,26,27 The use of the antiangiogenic drugs regorafenib and fruquintinib, or the chemotherapy compound trifluridine-tipiracil, is associated with a modest but significant clinical benefit compared with placebo.24,26,27 To date, SUNLIGHT is the only randomized phase 3 trial that demonstrated an improvement in both PFS and OS over an active treatment in patients with chemorefractory mCRC.25

In this scenario, novel and more effective therapeutic options are required. To answer to this unmet need, in this nonrandomized controlled trial, we conducted a pooled analysis of IPD from patients enrolled in 4 prospective Italian phase 2 studies that investigated different anti-EGFR rechallenge strategies.9,11,12,13,14 Because the presence of RAS/BRAF alterations at baseline liquid biopsy is associated with unresponsiveness to anti-EGFR mAbs, only patients with plasma ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt mCRC were included in this analysis. Here we provide evidence based on the largest data set available that anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy exerts antitumor activity.

The expected survival for patients with refractory mCRC who received trifluridine-tipiracil, regorafenib, or fruquintinib as single agents is approximately 7 to 9 months, whereas patients who were treated with trifluridine-tipiracil plus bevacizumab as third-line therapy had a median OS of 10.8 months.22,24,26,27 Furthermore, the available options display mainly a cytostatic activity (ORR, 1%-6%).24,25,26,27 With all the limitations for indirect cross-trial comparisons, in this study we report an OS longer than 12 months, with approximately one-third of the patients experiencing long survival (approximately 18 months).

In the study population, anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy was administered as third or later line of treatment. Interestingly, no difference in terms of survival was observed between patients according to the number of previous lines of therapies. Moreover, in this heavily pretreated population, anti-EGFR rechallenge achieved an ORR of 17.5% and a DCR of 72.3%. Thus, in a potential real clinical scenario, ctDNA-associated rechallenge with EGFR inhibitors could be considered following progression to trifluridine-tipiracil plus bevacizumab or an option as third-line treatment if tumor shrinkage is required. Further evidence regarding the optimal timing of anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy in the continuum of care of refractory mCRC will be provided by the results of the currently ongoing PARERE trial.28 Overall, more than 200 patients with ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt tumors will be randomly assigned to receive either panitumumab as third-line treatment followed by regorafenib at disease progression or the reverse sequence.

To better elucidate the role of potential factors involved in each treatment’s efficacy, we conducted an exploratory analysis investigating. The absence of liver metastasis was associated with a significantly longer median PFS and OS. Remarkably, 1 of 5 patients was still progression free at 12 months and alive beyond 30 months. Of course, owing to the nature of this subgroup analysis, these data require further confirmation by larger prospective trials. If confirmed, prospective translational and so-called multi-omics studies (ie, studies using data types derived from different research areas, such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics) are required to identify the subset of patients with liver metastases who could respond to anti-EGFR treatment.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that are intrinsic to its design. First, this pooled analysis has included patients who were enrolled in 4 phase 2 studies administering different therapies, which could have influenced clinical outcomes. In this respect, no evidence is currently available regarding the best anti-EGFR rechallenge regimen. To address this question, our group is currently conducting the CAVE-2 trial, a randomized phase 2 trial, that compares rechallenge with cetuximab plus avelumab vs cetuximab as single agent in patients with refractory plasma ctDNA RAS/BRAF wt microsatellite stable mCRC.29 Second, distinct liquid biopsy tests with different sensitivity thresholds and different panels were used for ctDNA analysis in the 4 trials. In the CHRONOS trial, a highly sensitive ddPCR was used, and only patients with 0 RAS/BRAF/EGFR ECD alteration in ctDNA were included.12 For the CAVE and VELO trials, the IdyllaTM Biocartis platform was used.20 Nevertheless, the issue of what is the real impact of a very low alteration allele fraction on anti-EGFR drug response is still debated.30,31 Third, alterations other than RAS/BRAF, such as EGFR ECD, MAP2K1, and ERBB2 alterations or amplification, could constitute mechanisms of cancer cell resistance to EGFR blockade.32,33,34,35,36 Future trials using larger next-generation sequencing panels for patient selection will contribute to answer this question.37 Fourth, because of the single-group design of the CRICKET, CAVE, and CHRONOS trials and the reduced number of patients included in the control group of the VELO study, no direct comparison with other therapeutic options could be performed. Fifth, we were not able to evaluate the impact of the burden of hepatic disease (number and dimension of liver metastases) on treatment efficacy. These results should be considered as exploratory and hypothesis generating.

Conclusions

In this pooled analysis of IPD from 4 phase 2 trials, anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy showed a promising antitumor activity in patients with refractory RAS/BRAF wt tumors as confirmed by liquid biopsy. Within the limitation of a subgroup analysis, the absence of liver metastases was associated with significantly improved survival. Further randomized studies are currently ongoing to confirm these results.

Trial Protocols

eFigure 1. Forest Plot of Progression Free Survival in Different Subgroup

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Overall Survival (OS) in Different Subgroup

eTable 1. Progression Free and Overall Survival Rate in the Study Population

eTable 2. Progression Free and Overall Survival Rate According to the Presence of Liver Metastasis

eTable 3. Adverse Events

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(1):10-32. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S, Bardelli A. Resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: from heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(11):1269-1280. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinelli E, Ciardiello D, Martini G, et al. Implementing anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: challenges and future perspectives. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):30-40. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parseghian CM, Loree JM, Morris VK, et al. Anti-EGFR-resistant clones decay exponentially after progression: implications for anti-EGFR re-challenge. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(2):243-249. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Buscarino M, et al. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):795-801. doi: 10.1038/nm.3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciardiello D, Martini G, Famiglietti V, et al. Biomarker-guided anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(8):1941. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauri G, Pizzutilo EG, Amatu A, et al. Retreatment with anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in metastatic colorectal cancer: systematic review of different strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:41-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santini D, Vincenzi B, Addeo R, et al. Cetuximab rechallenge in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: how to come away from acquired resistance? Ann Oncol. 2012;23(9):2313-2318. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cremolini C, Rossini D, Dell’Aquila E, et al. Rechallenge for patients with RAS and BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer with acquired resistance to first-line cetuximab and irinotecan: a phase 2 single-arm clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(3):343-350. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunakawa Y, Nakamura M, Ishizaki M, et al. RAS mutations in circulating tumor DNA and clinical outcomes of rechallenge treatment with anti-EGFR antibodies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4(4):898-911. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinelli E, Martini G, Famiglietti V, et al. Cetuximab rechallenge plus avelumab in pretreated patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: the phase 2 single-arm clinical CAVE trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):1529-1535. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sartore-Bianchi A, Pietrantonio F, Lonardi S, et al. Circulating tumor DNA to guide rechallenge with panitumumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: the phase 2 CHRONOS trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1612-1618. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01886-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napolitano S, De Falco V, Martini G, et al. Panitumumab plus trifluridine-tipiracil as anti-epidermal growth factor receptor rechallenge therapy for refractory RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(7):966-970. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Napolitano S, Ciardiello D, De Falco V, et al. Panitumumab plus trifluridine/tipiracil as anti-EGFR rechallenge therapy in patients with refractory RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: overall survival and subgroup analysis of the randomized phase II VELO trial. Int J Cancer. 2023;153(8):1520-1528. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji A, Nakamura M, Watanabe T, et al. Phase II study of third-line panitumumab rechallenge in patients with metastatic wild-type KRAS colorectal cancer who obtained clinical benefit from first-line panitumumab-based chemotherapy: JACCRO CC-09. Target Oncol. 2021;16(6):753-760. doi: 10.1007/s11523-021-00845-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossini D, Germani MM, Pagani F, et al. Retreatment with anti-EGFR antibodies in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a multi-institutional analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2020;19(3):191-199.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis . Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) Adverse Events/CTCAE. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/adverse_effects.htm

- 20.Vitiello PP, De Falco V, Giunta EF, et al. Clinical practice use of liquid biopsy to identify RAS/BRAF mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): a single institution experience. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1504. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciardiello F, Ciardiello D, Martini G, Napolitano S, Tabernero J, Cervantes A. Clinical management of metastatic colorectal cancer in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(4):372-401. doi: 10.3322/caac.21728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tampellini M, Di Maio M, Baratelli C, et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in a real-world scenario: probability of receiving second and further lines of therapy and description of clinical benefit. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16(4):372-376. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossini D, Germani MM, Lonardi S, et al. Treatments after second progression in metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of the TRIBE and TRIBE2 studies. Eur J Cancer. 2022;170:64-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. ; RECOURSE Study Group . Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1909-1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prager GW, Taieb J, Fakih M, et al. ; SUNLIGHT Investigators . Trifluridine-tipiracil and bevacizumab in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(18):1657-1667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2214963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. ; CORRECT Study Group . Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):303-312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasari A, Lonardi S, Garcia-Carbonero R, et al. ; FRESCO-2 Study Investigators . Fruquintinib versus placebo in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (FRESCO-2): an international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2023;402(10395):41-53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00772-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moretto R, Rossini D, Capone I, et al. Rationale and study design of the PARERE Trial: randomized phase II study of panitumumab re-treatment followed by regorafenib versus the reverse sequence in RAS and BRAF wild-type chemo-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2021;20(4):314-317. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2021.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Napolitano S, Martini G, Ciardiello D, et al. CAVE-2 (Cetuximab-AVElumab) mCRC: a phase II randomized clinical study of the combination of avelumab plus cetuximab as a rechallenge strategy in pre-treated RAS/BRAF wild-type mCRC patients. Front Oncol. 2022;12:940523. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.940523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidal J, Bellosillo B, Santos Vivas C, et al. Ultra-selection of metastatic colorectal cancer patients using next-generation sequencing to improve clinical efficacy of anti-EGFR therapy. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(3):439-446. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauri G, Vitiello PP, Sogari A, et al. Liquid biopsies to monitor and direct cancer treatment in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2022;127(3):394-407. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo M, Siravegna G, Blaszkowsky LS, et al. Tumor heterogeneity and lesion-specific response to targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(2):147-153. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaghi C, Mauri G, Agostara AG, et al. The predictive role of ERBB2 point mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023;112:102488. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randon G, Maddalena G, Germani MM, et al. Negative ultraselection of patients with RAS/BRAF wild-type, microsatellite-stable metastatic colorectal cancer receiving anti-EGFR-based therapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6(6):e2200037. doi: 10.1200/PO.22.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartore-Bianchi A, Amatu A, Porcu L, et al. HER2 positivity predicts unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(10):1395-1402. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauri G, Patelli G, Gori V, et al. Corrigendum: case report—MAP2K1 K57N mutation is associated with primary resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1147497. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1147497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciardiello D, Mauri G, Sartore-Bianchi A, et al. The role of anti-EGFR rechallenge in metastatic colorectal cancer, from available data to future developments: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024;124:102683. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocols

eFigure 1. Forest Plot of Progression Free Survival in Different Subgroup

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Overall Survival (OS) in Different Subgroup

eTable 1. Progression Free and Overall Survival Rate in the Study Population

eTable 2. Progression Free and Overall Survival Rate According to the Presence of Liver Metastasis

eTable 3. Adverse Events

Data Sharing Statement